Legal aid - policy issues

This briefing looks at the current policy issues in relation to legal aid. It accompanies a separate SPICe briefing which looks at how the different types of legal aid work.

Summary

Legal aid provides support to people who might not otherwise be able to afford it to access legal advice and representation. Solicitors who carry out legal aid work are paid a fee, set in legislation, for their work.

The current system relies heavily on the willingness of solicitors in private practice to take on legal aid cases. There are tensions in relation to rates of pay and working hours.

The Scottish Government commissioned an independent review of legal aid to look at reform of the current system. It recommended a citizen-centred system which was flexible and focussed more on matching advice provision to identified need. It envisaged greater co-ordination between the services provided by lawyers and those of other publicly funded advice providers.

This briefing looks at:

An overview of legal aid

Legal aid provides financial assistance to enable people on low and moderate incomes to access legal advice and representation in court. It plays an important role in enabling access to justice for people who might struggle to pay for legal services otherwise.

Legal aid is funded by the Scottish Government and administered by the Scottish Legal Aid Board (SLAB). SLAB also directly employs solicitors to give advice to people who qualify for legal aid and grant funds various advice services (including services not provided by solicitors).

There are various different types of legal aid, each with specific criteria in relation to financial eligibility and the reasonableness of granting assistance. These are discussed in more detail in the SPICe briefing Legal Aid - how it works (2021)1.

In broad summary, the main strands of legal aid are as follows:

Advice and Assistance provides advice but not representation in court from a solicitor. It could cover advice on whether to accept a fiscal fine, negotiation in relation to a problem neighbour or advice on presenting a low value consumer case in court.

Assistance By Way of Representation (ABWOR) is a strand of Advice and Assistance. It can be used in specific legal forums set out in legislation to provide representation from a solicitor. It is mainly used for those who plead guilty to summary (less serious) criminal charges, for Children's Hearings and for certain tribunal hearings, such as immigration and employment tribunals.

Criminal Legal Aid provides representation from a solicitor in the criminal courts. It is available to someone who pleads not guilty in summary (less serious) criminal proceedings or where someone is charged under solemn (more serious) criminal proceedings.

Civil Legal Aid provides representation from a solicitor in civil court matters, such as divorce, housing or discrimination cases. Most types of actions in the civil courts are covered.

Children's Legal Aid provides representation from a solicitor for some types of court action related to decisions by Children's Hearings.

A significant proportion of the population are able to qualify for legal aid. However, in some circumstances, people need to make a contribution from their own income towards the costs of the legal services they receive. This contribution increases as income increases. People who, on the face of it, qualify for legal aid can be put off by this requirement.

The legal aid budget

Expenditure on legal aid has been generally reducing over the past 10 years.

The legal aid budget is £138 million for the financial year 2021/22

This includes £12.2 million to cover the administration costs of SLAB. SLAB's administration costs have remained in the region of £12 million per year for the past 10 years.

An important aspect of the legal aid budget is that it is not capped (although the administrative allocation for SLAB is). The Scottish Government is obliged to meet all expenditure on legal aid services legitimately claimed by solicitors. This means that the actual expenditure is demand-led and can differ from the predicted budget for that year.

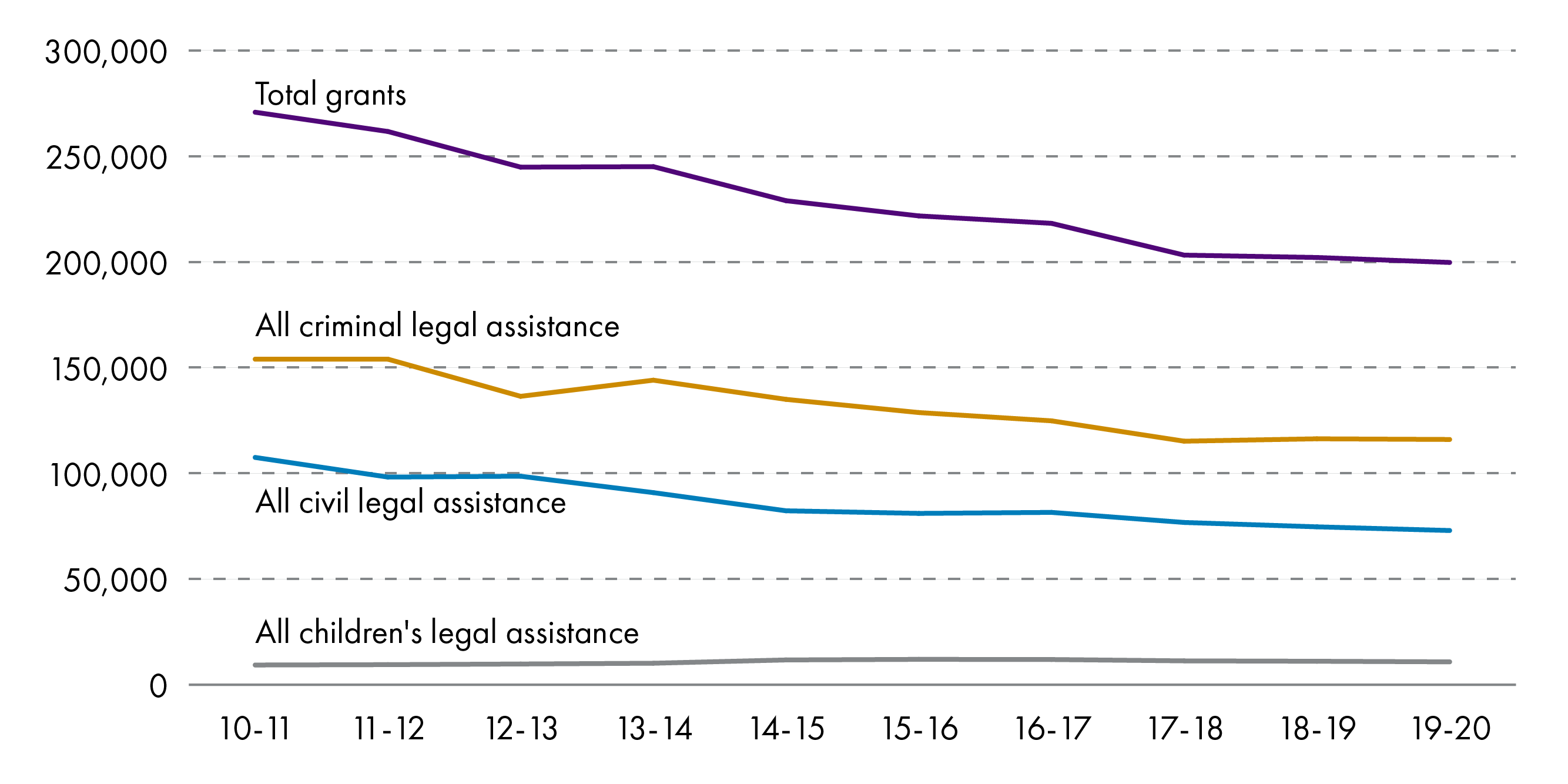

There has been a downward trend in the number of legal aid applications granted

The chart below shows the number of legal aid applications granted between 2010-11 and 2019-20. It looks specifically at civil, criminal and children's legal assistance. The overall trend has been downwards, reflected in both civil and criminal grants.

There has been a gradual increase in the number of grants of children's legal assistance over the time period, but these make up a small proportion of the total number of grants.

The general downwards trend reflects the broad pattern for court business as well. The number of criminal and civil cases being raised in court has generally been reducing for the past 10 years.

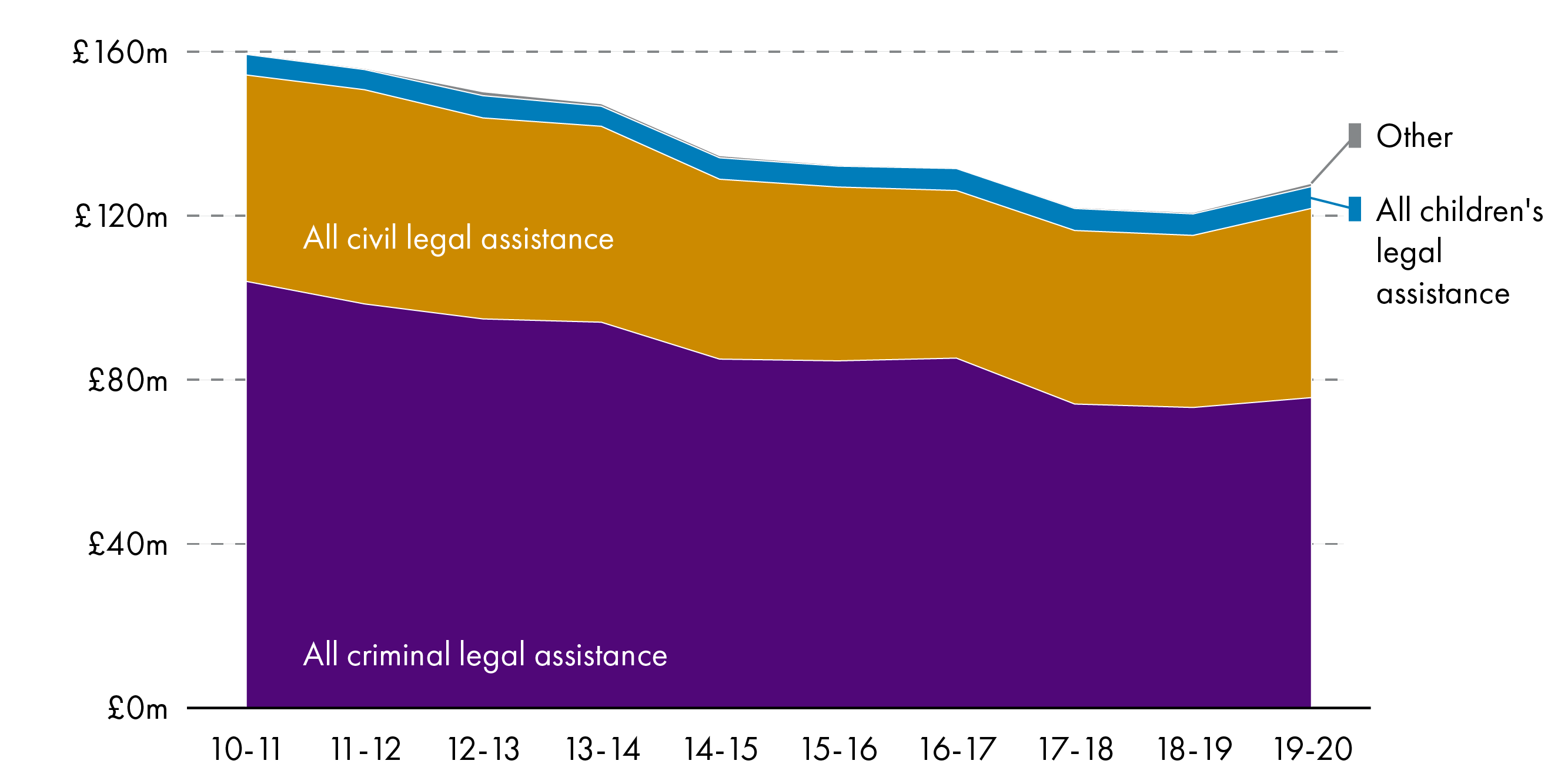

Expenditure on legal aid also followed this downward trend

The chart below looks at expenditure on legal aid between 2010-11 and 2019-20 in £000s. It excludes SLAB's administrative costs and the money it spends on grant funding in the advice sector.

Money comes into the legal aid system in several ways:

financial contributions from the recipient

court-awarded legal expenses and money recouped from property recovered by legal aid recipients in civil court actions

adjustments to accounts following an audit, where SLAB reduces the amount of money paid to solicitors on the basis that it was not correctly claimed.

The figures below reflect the net cost of legal aid, i.e. after these sums have been deducted. This shows the actual cost to the tax payer of legal aid.

Again, the general trend is for reducing expenditure in both civil and criminal legal assistance. This partly reflects deliberate steps by the Scottish Government to reduce the budget in the early part of the time series, in response to the 2008 financial crisis and resulting public sector austerity measures. It also reflects reducing demand for legal aid (as highlighted in Figure 1 on grants of legal aid) and reducing numbers of cases going to court.

Both civil and criminal legal assistance saw an increase in expenditure in 2019-20. It is too early to say whether this will bring the downwards trend to an end. Expenditure is expected to have reduced in 2020/21, due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, but court business has increased since then to deal with a backlog in cases.

Independent review of legal aid

In 2017, the Scottish Government commissioned a wide-ranging and independent review of legal aid. The review had the following remit:

"To consider legal aid in the 21st century: how best to respond to the changing justice, social, economic, business and technological landscape."

The review's report, Rethinking Legal Aid: an independent strategic review, was published in 20181. It recommended a fundamental rethink of legal aid, leading to a system which is simpler, more flexible and puts the needs of the user - the citizen in need of advice - at its centre. The review envisaged that it would take 10 years to implement its recommendations.

This part of the briefing looks at:

The recommendations of the independent review of legal aid

The independent review argued that legal aid should be seen as a public service. However, it was not clear that those involved in the current system saw it like that. Providers were mainly private sector solicitors. SLAB lacked the drivers to change the way solicitors provided their services or to plan services on the basis of need rather than supply.

The review grouped its recommendations under six strategic aims:

Place the user voice and interests at the centre

The review argued for a system where users - citizens in need of legal advice - can voice their needs and there is a flexible response to those needs. It called for a new statutory framework which incorporated user representation, as well as better co-operation between stakeholders, including local authorities and third sector organisations.

Maintain the scope but simplify

The review recommended that the issues for which legal aid was available should remain wide-ranging. It referred to this as the "scope" of legal aid.

It also recommended that the system should move, over time, from four types of legal aid to one - which would cover all criminal and civil justice issues. There would still be a financial eligibility test, but it would be simplified. Any tests in relation to the reasonableness of granting legal aid should be clear and accessible.

Those receiving Criminal Legal Aid are not currently required to make any financial contribution to the cost of their case. The review recommended that this should change, so that recipients were treated the same as those getting other types of legal aid. This is one of several areas where the review argued that the system could be made fairer.

Support and develop an effective delivery model

The review talks about "publicly-funded legal assistance" and envisaged that funding would be available to certain advice services as well as to lawyers. It argued that more co-ordination between solicitors, advice services and other support providers would result in better outcomes for users.

The review recommended that publicly-funded legal assistance is linked into the community planning process. This would allow funders, including local authorities and third sector bodies, to develop local advice action plans which would identify areas of need and agree expected outcomes.

The review also called for the powers and flexibility available to SLAB to be increased, so that it could adjust the way legal services were delivered to meet both demand and social changes.

Create fair and sustainable payments and fees

The review was not persuaded of the need for a general increase in legal aid fees. This view was based, at least in part, on the fact that some lawyers appeared to do very well out of legal aid work.

The review did, however, accept that fee rates were a source of significant, ongoing tension between solicitors, the Scottish Government and SLAB. It recommended the establishment of evidence-based process to set fees.

The proposals would require the Scottish Government and solicitors to agree a set methodology, which would be used to regularly review fee levels. Evidence would come from the legal profession, which would necessarily entail a willingness to share commercial information.

Invest in service improvement and technological innovation

Currently, changes to legal aid processes often require changes to regulations or primary legislation. The review saw this as limiting responsiveness and innovation - and making the current system unsuitable for the rapid technological changes which are expected in the sector.

The review highlighted many barriers to innovation within publicly-funded legal services. It called for specific investment and support to overcome these. It noted, in particular, opportunities to utilise online tools to provide advice more efficiently, including interactive websites.

Establish effective oversight

The review recommended that publicly-funded legal services continued to be overseen by a public body operating at arms-length from government. This was argued to provide the necessary independence while still maintaining strong relationships with government. The public body would, however, require new powers; in particular to be able to match legal services to need and to deliver innovation.

The Scottish Government response to the review

There has been broad support for the principles set out in the review but less consensus on how to deliver them.

The Scottish Government accepted most of the review's recommendations

The Scottish Government responded to the review in 20181. It accepted most of the recommendations but noted the need for further consultation on how they were to be delivered. It also signalled its intention to implement a 3% increase in legal aid fees in April 2019, while an evidence-based fee review process was being established.

However, the Scottish Government did not accept the need to establish a new public body to oversee the reformed system. It highlighted its intention to retain the Scottish Legal Aid Board for this task, potentially with enhanced powers.

Further consultation showed a lack of consensus on how change could be delivered

The Scottish Government went on to issue a consultation in 20192. The analysis of responses3 showed broad agreement with the principles set out in the review. However, there was a lack of consensus about how change should be delivered, with contrasting views between the legal profession and the third sector in many cases.

Broadly, there was third sector and law centre support for the use of grants, contracts and memorandums of understanding to increase the flexibility of legal aid provision. However, the legal profession did not support these forms of intervention, nor increasing the discretion available to SLAB.

There was more consensus around simplifying legal aid processes. Respondents supported a single eligibility test and a simplified system for users to make financial contributions, but also stressed the importance of fairness. However, two-thirds of respondents were opposed to the introduction of financial contributions for Criminal Legal Aid.

Given the support in principle for reform, the Scottish Government has stated that it will continue to work towards creating a new legislative framework.

Stakeholder reactions

There were contrasting views from three major stakeholders: the Law Society of Scotland, representing solicitors; Citizens Advice Scotland as the umbrella organisation for the biggest network of advice providers; and SLAB, the current administrators of legal aid.

The Law Society of Scotland saw poor rates of pay as the main problem

The Law Society did not support greater use of grant funding, contracts or memorandums of understanding to target legal aid in ways which were more appropriate to local need. It argued that the service was a national one, with universal entitlement (within the qualifying criteria).

It did, however, support the current levels of use of grant funding and SLAB-employed solicitors. It also accepted that targeted intervention in relation to unmet need may be appropriate in some limited circumstances.

In the Law Society's view, the best way to ensure legal aid was accessible across a wide range of subjects and geographical areas was to encourage as many solicitors as possible to participate. This could be done by reducing bureaucracy and increasing fee levels. Commenting on the reducing number of solicitors offering legal aid, it said1:

"... we see the bureaucracy and complexity of the system and the unsustainability of current remuneration as the main drivers."

Citizens Advice Scotland called for more resources to be allocated to early resolution

Citizens Advice Scotland called for a shift in the way legal aid funding is allocated2 towards the early intervention and preventative approaches delivered by advice agencies. It argued that this would lead to less costly resolution of disputes and a more inclusive society.

Citizens Advice Scotland did agree that provision through private solicitors should continue. It supported more control over the outcomes from legal aid funding through the use of memorandums of understanding.

It also noted that the Citizens Advice Bureau network could not accept legal aid funding in its current form. That would often require a financial contribution to be made by the client, which was contrary to its commitment to providing a free service. However, it supported the increased use of grant funding.

The SLAB response looked at how legal aid as a public service could operate

SLAB does not consider legal aid delivery to be a public service currently. The SLAB response3 notes that it is not directed towards specific needs or aligned with other public services. There is no way to control services provision to meet agreed outcomes.

SLAB's response looks at potential models of delivery that could move legal aid more towards

being considered a public service. This would involve greater control over how services are delivered, through memorandums of understanding and direct commissioning. It would also involve more funding being directed towards targeted provision (in contrast to the current situation where solicitors choose whether to offer services).

It described five potential models. These could range from the current system, where 93% of funding is on services from private solicitors, to a system where most funding is in the form of grants or contracts targeted towards agreed services. At the most public service-focussed end of the range of potential models, only a small proportion of funding would be available in its current format, as a safety valve to deal with unexpected need.

Key issues for the reform agenda

The reform process so far has highlighted several areas of tension in developing future options. This part of the briefing looks at:

The role of the state in planning legal aid services

A key tension in the reform process is to what extent legal aid services should be planned by the state.

Current legal aid provision is unplanned

At the moment, those solicitors registered to provide legal aid are still free to decide whether to offer it in any particular case. Neither SLAB nor the Scottish Government has the ability to direct specific services to be provided, and there is no way to ensure that the money invested in legal aid delivers specific outcomes.

In its response to the Scottish Government consultation, SLAB draws a distinction between eligibility and entitlement. At present, someone may be eligible for legal aid but that is not a guarantee that any legal aid services will be available.

Moving to a model of delivery that is closer to a public service would address these issues. With greater control over the services provided and more ability to target services through grant funding or contracting, legal aid could become more aligned with government objectives.

Moving to a delivery model with more state control has risks

However, there are also risks to such an approach. Currently, the infrastructure of legal aid is mainly paid for by private solicitor firms (although there is some delivery through solicitors directly employed by SLAB). The risk of failure is theirs. And a range of independent actors are able to respond flexibly to changes in the legal system as well as changes in customer expectations.

In order to deliver a strongly public service-oriented version of legal aid, SLAB and the Scottish Government would have to become expert in predicting areas of need and procuring services accordingly. Meeting all areas of legal need could be expensive, but a capped budget would mean the need to prioritise certain areas over othersi.

Fundamentally, the ability to access legal advice which is independent of state control is also important. SLAB explains the tension in its consultation response (paragraph 60)2.

Judicare describes the current model of legal aid service delivery, where solicitors in private practice decide themselves whether to offer legal aid and are paid on a case-by-case basis.

"A preponderance of targeted funding on a fixed budget basis has the benefit of directing service delivery towards the achievement of Scottish Government priorities and outcomes. This is not unusual in most public services, but it comes into conflict with a key benefit of non-targeted judicare, which is that it gives an ability to develop and use the law to challenge government and government bodies regardless of government’s stated priorities and sometimes in a direct challenge to the achievement of priorities."

Creating a more joined-up system

Better co-ordination between advice service providers could improve the experience of a citizen seeking advice, but the current system involves a range of stakeholders working to different objectives.

The independent review of legal aid described the current situation as follows (page 61)1:

"The current model of delivery of publicly-funded legal assistance is fragmented with many providers of different types of legal aid and advice, and the service appears to be driven by the available supply rather than identified need."

The phrase "publicly-funded legal assistance" is intended to capture various advice services which sit outside the formal legal aid system at the moment. Currently, only solicitors can claim legal aid fees, although SLAB does grant-fund some other advice providers.

There are many different delivery models for advice provision

There are various providers of non-lawyer delivered advice. Most local authority areas have a Citizens Advice Bureau. Local authorities may also provide debt and welfare benefit-focussed advice services themselves, and some provide advice in other areas.

In addition, there are national advice lines and topic-based providers, such as Shelter. There are also a range of smaller, local advice providers, as well as support services which signpost to sources of advice rather than providing it themselves.

It is not immediately clear where to draw the line between services which could be funded via legal aid and services which would not.

Funding for these services is also multi-layered. Most funding for advice services comes from local authorities. However, this is augmented by funding from charitable bodies and specific grant streams from the Scottish Government and its agencies. Some debt advice providers - for example, Stepchange - have their own funding arrangements with creditors to supplement their grant income.

Law centres provide a further model of advice delivery. They employ lawyers to deliver specialist advice but may also use non-legally qualified advisers for certain topics or projects. Their funding is a mixture of legal aid and grants from local authorities and/or the Scottish Government.

The independent review saw a role for the community planning process in co-ordinating local advice provision

Community planning allows a range of public sector organisations to come together to work with local communities to deliver improved services.

The independent review recommended that current funders of advice should co-ordinate their approaches using the community planning process. Funders should work together to produce local advice action plans.

However, these proposals got a mixed response in the Scottish Government consultation. Roughly one third of respondents either agreed, disagreed or were unsure about the idea. In addition, there has been little engagement from local authorities so far. Local authorities are the main funders of advice as well as the drivers of community planning.

Separately, the Scottish Government, SLAB and the Improvement Service have been working on better co-ordination in advice funding. The Improvement Service has more information about a framework for the public funding of advice on its website. The Scottish Government commissioned a review of publicly funded advice services in Scotland, which was published in 20182.

Supporting flexibility and innovation

The current legal aid system is heavily constrained by a statutory framework which prevents flexibility and innovation.

In most cases, changes to the current processes for delivering legal aid require the approval of the Scottish Parliament to regulations which amend the statutory framework. The statutory framework itself can be difficult to follow due to being heavily amended.

The independent review of legal aid noted that the system would need to become more flexible to respond to evolving user need. In addition, the review expected to see rapid technological advances in the delivery of advice services in the coming years. To respond effectively, there would need to be the capacity to pilot new models of service delivery.

If it is to deliver on the review's vision, the new statutory framework for legal aid is going to look very different from the current regime. Wider consideration around transparency and accountability will also be necessary.

In its response to the Scottish Government's consultation1, SLAB discussed options for frameworks for the delivery of legal aid. These ranged from the current system, with a framework mainly set out in legislation, to a system where the legislation sets only outcomes and gives SLAB complete discretion (with accountability to the Scottish Parliament) as to how they are delivered.

However, the Scottish Government's analysis of responses to the consultation2 revealed significant resistance among the legal profession to giving more discretion to SLAB.

Legal aid payment rates

The fees paid for legal aid work are a significant source of tension between the legal profession and the Scottish Government.

Legal aid payments are a key income stream for criminal defence solicitors

Many criminal defence solicitors work with clients who are reliant on legal aid. Thus the fee rate for legal aid is a key factor in how they set up their business models and how much they personally earn.

In addition, criminal defence solicitors may need to represent clients at police stations, either after they have been arrested or because they have been called in for questioning. This can happen at any time of day or night. For more information about how legal aid operates in this context see the "Advice at the police station" section of the SPICe briefing Legal Aid - how it works1.

The legal profession argues that low rates of pay and poor work-life balance make a career in criminal defence unattractive to younger lawyers.

Legal aid is less important to the work of most civil law solicitors but fee rates may still have an impact on their willingness to offer legal aid

Legal aid is not a big part of the work of most solicitors who specialise in civil law. However, the fee rates are still argued to be causing fewer firms to be prepared to take on legal aid work. There are some civil law delivery models - for example, law centres and some family law practitioners - that are more reliant on legal aid.

There are different types of legal aid fee

Legal aid legislation originally provided for detailed fees for different aspects of a solicitor's work, for example, writing a letter or conducting a 30 minute court hearing. A fee was ascribed to each element and what a solicitor got paid would be the sum of the different pieces of chargeable work carried out. This is referred to as time and line charging.

Time and line charging requires detailed accountancy processes to be in place, and there is scope for disagreement between solicitors and SLAB about whether particular pieces of work were necessary.

Over time, block fees (where a set fee is paid for reaching a certain stage in the work) and fixed fees (where a set fee is paid for the whole case) have been introduced to cover many aspects of legal aid work. These are simpler to administer for both solicitors and SLAB as they reduce the costs associated with preparing and negotiating detailed accounts.

However, payments may under or over-compensate for the level of work carried out in a particular case. Where solicitors feel they will not receive reasonable remuneration in a particular case they can apply for exceptional case status, which provides for time and line charging.

This part of the briefing looks at:

Recent developments in relation to legal aid fee rates

The independent review of legal aid did not recommend a general increase in legal aid rates. Instead, it recommended that a working group was set up to agree an evidence-based process for fixing rates in the future. The section on the Legal Aid Payment Advisory Panel has more details.

There have been several recent fee increases

There was a 3% across the board fee increase for legal aid fees in April 2019. The Scottish Government introduced this as a stop gap while the Legal Aid Payment Advisory Panel looked at a mechanism for setting fees on a more permanent basis.

The Scottish Government announced a further 5% general increase from March 2021, with another 5% increase planned for March 2022. This was accompanied by additional financial support in the form of a £9 million Covid Resilience and Recovery Fund to help legal aid firms deal with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and a £1 million fund to support trainee solicitors in legal aid businesses1.

The legal profession remains unhappy with the Scottish Government approach

However, the legal profession has argued that these measures do not go far enough. They note that they do not even undo the effects of inflation on the current fee regime. Amanda Miller, the then President of the Law Society, commented2:

"The 5% increase in legal aid fees is a welcome step forward, but it is only a step. Successive governments have allowed legal aid fees to plummet in real terms. We need a long-term plan to address this generation of underfunding."

The Scottish Solicitors' Bar Association, supported by many local solicitors' bodies, organised a withdrawal of services by criminal defence solicitors on 17 May 20213. The action was to highlight the need for more financial support to law firms reliant on legal aid.

In particular, the Scottish Solicitors' Bar Association action highlighted that only a quarter of the available funding from the Covid Resilience and Recovery Fund had been distributed. Following further negotiations with the legal profession, the Scottish Government announced a new fund- the Legal Aid Business Support and Recovery Fund - to allocate the remaining £6.7 million4.

The work of the Legal Aid Payment Advisory Panel

The Legal Aid Payment Advisory Panel was established following a recommendation in the independent review of legal aid for an evidence-based process to set legal aid fee rates.

The remit of the panel covered looking at short-term improvements and mechanisms for ensuring greater certainty in the delivery of legal aid services, as well as proposing a long-term process for setting legal aid payment rates.

The Panel concluded that there was not enough information at present to establish a fee-setting process

The Panel published its report in July 20211. It concluded that more research was needed before an effective fee-setting process could be established. It recommended that "an evidence guided process that considers the cost of delivery, the health of the market and the priorities of the user" should be developed as part of the general reform process for legal aid.

The process it envisaged would look at:

a wider range of payment methods, including grants and contracting

regular consideration of how to adjust payment structures to meet policy objectives

whether changes were needed to maintain sustainability in the delivery of legal aid services.

The Panel designed specific research questions intended to quantify how the current market worked and what a sustainable system would look like. It envisaged an eight month timescale between commissioning the research and publication of the results.

The Panel made recommendations for actions which could take place in the shorter term

These were:

that a wider range of payment methods than case-by-case fees should be used and embedded into the reform process

that research should look at legal aid business models in the context of wider social changes, including problems with recruitment and retention

there should be greater clarity around the expectations of SLAB and the Scottish Government in relation to the service to be provided by solicitors receiving legal aid

there were various ways that the current legal aid payment system could be simplified, and these should be progressed in the short-term.