Economic development in Scotland

The briefing provides an overview of economic development in Scotland. It looks at the main organisations involved in delivering economic development activities, the direction of economic development strategy, and current economic development programmes in Scotland.

Summary

What is economic development?

There is no single agreed definition of economic development, but it can include targeted investment in, and running of, infrastructure, investment in skills and training, and support for marketing, promotion and network building. These interventions can have various purposes, including improving productivity, encouraging ‘greener’ activity, supporting innovation, generating more exports, promoting start-ups, encouraging inward investment, and getting people into good quality jobs.

The Scotland Act of 1998 established the Scottish Parliament, giving Scotland control over devolved areas such as health, education, justice, transport, local government and economic development.

Scotland's economic development actors

The key economic development actors in Scotland include:

Scottish Enterprise

Highlands and Islands Enterprise

South of Scotland Enterprise

Local government

Regional Economic Partnerships

Scottish National Investment Bank

Skills Development Scotland.

Issues in measurement and a cluttered landscape?

Measuring the activities of the publicly funded economic development agencies against the Scottish Government’s budget and intended outcomes has been an ongoing challenge for parliamentary scrutiny. Over 20 years ago in 1999, there were concerns around this matter from a parliamentary committee, and despite the passing of time, a 2021 legacy report from a parliamentary committee concluded similar.

A 'cluttered landscape' has been something of a recurring theme when in it comes to economic development in Scotland. Over the last six years, we have seen some attempts at rethinking the ‘enterprise and skills’ landscape in Scotland, via the activities of the Enterprise and Skills Strategic Board. But the question is whether this has achieved the change that was originally anticipated, as some would argue the landscape is still cluttered.

Economic development strategy in Scotland – is there one?

There is no agreed definition of economic development activity, as already highlighted. However, since devolution in 1999, the Scottish Executive/Scottish Government has had some form of economic development strategy - Scotland’s earlier strategies were framed as economic development strategies but more recently just tend to be called economic strategies.

The first strategy, following devolution, started out as direction for the enterprise networks. Successive strategies gradually tackled wider social challenges and offered direction for the wider public sector, eventually arriving at the “One Scotland Approach” in the 2015 Strategy.

Over the last two decades, Scotland’s economic policy landscape has evolved from a narrow enterprise agency approach to a wider whole government approach. While there is merit to this more holistic approach to economic policy, it has weakened accountability, and makes evaluating what actually works all the more difficult. There have been no formal procedures in place to form an overall assessment of the success of successive economic strategies.

Funding programmes

This briefing details some of the key funding programmes, which support economic development in Scotland. These include EU Structural funds, and their proposed replacements, this year, the Community Renewal Fund, and next year, the Shared Prosperity Fund, as well as the (UK wide) Levelling Up fund. It also provides some details on:

Green Ports (the proposed Scottish version of Freeports)

City and Regional Growth Deals

enterprise areas

and some other programmes such as the Green Jobs Fund, the National Manufacturing Institute, and a Women's Business Centre.

Frictions or synergies in strategy?

This briefing outlines a constant process of reorganising and rescaling governance arrangements across the economic development landscape over the last two decades in Scotland. This has been shaped by actors at local, Scottish and UK levels. This briefing asks whether this results in frictions or synergies for different places within Scotland to pursue economic development.

The overview of key funding interventions currently in delivery or planning across Scotland's economic development landscape illustrates the varying policy levers that both the Scottish and UK Governments are pursuing, which are not always fully aligned. The economic development landscape is complex and this complexity isn't necessarily helped by the varying intentions of different public sector actors.

What do we mean by economic development?

There is no single agreed definition of economic development (for example see Audit Scotland 20161) but it certainly covers a wide range of “supply side” programmes. These are government policies to increase productivity and increase efficiency in the economy, which increase aggregate supply enabling higher economic growth in the long-run. These can include targeted investment in, and running of, infrastructure, investment in skills and training, and support for marketing, promotion and network building. These interventions can have various purposes, including improving productivity, encouraging ‘greener’ activity, supporting innovation, generating more exports, promoting start-ups, encouraging inward investment, and getting people into good quality jobs.

It does not generally include measures to manage the economy such as fiscal policy (changes to tax, spending and borrowing), monetary policy (such as setting interest rates), or other regulatory measures (for example on price capping, environmental or safety standards, or labour market conditions).

The Scotland Act of 1998 established the Scottish Parliament, giving Scotland control over devolved areas such as health, education, justice, transport, local government and economic development. The Act identifies fiscal, economic, and monetary policy as being reserved.

Fiscal, economic and monetary policy, including the issue and circulation of money, taxes and excise duties, government borrowing and lending, control over United Kingdom public expenditure, the exchange rate and the Bank of England.

The 1998 Act does not reserve giving financial assistance to commercial activities for the purpose of promoting or sustaining economic development or employment. However, here it is worth highlighting that the UK Internal Market Act 2020 now specifically allows UK Ministers to intervene in economic development matters.

Power to provide financial assistance for economic development etc

(1)A Minister of the Crown may, out of money provided by Parliament, provide financial assistance to any person for, or in connection with, any of the following purposes—(a)promoting economic development in the United Kingdom or any area of the United Kingdom;

(b)providing infrastructure at places in the United Kingdom (including infrastructure in connection with any of the other purposes mentioned in this section);

(c)supporting cultural activities, projects and events that the Minister considers directly or indirectly benefit the United Kingdom or particular areas of the United Kingdom;

(d)supporting activities, projects and events relating to sport that the Minister considers directly or indirectly benefit the United Kingdom or particular areas of the United Kingdom;

(e)supporting international educational and training activities and exchanges;

(f)supporting educational and training activities and exchanges within the United Kingdom.

Scotland's economic development actors

This chapter looks in detail at the current key economic development actors in Scotland. These include:

However, before we explore the key organisations and partnerships, we provide some context on the background of the current economic development landscape and the key agencies. This section also explores measuring the performance of the key organisations and whether the economic development landscape is cluttered.

Some context on economic development responsibilities

While the current 32 Scottish local authorities have from their inception (1995) had some responsibility for economic development, this has been alongside the role of what was then two economic development agencies – Scottish Enterprise (SE) and Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE). These were established by the Enterprise and New Towns (Scotland) Act 19901, although their predecessors had been in existence since the 1970s and 1960s, respectively.

The Act gave both agencies the general functions of furthering the development of Scotland’s economy, safeguarding employment, enhancing skills, promoting industrial efficiency and international competitiveness, and improving the business environment, with the crucial distinction that HIE had a geographic remit confined to the Highlands and Islands and additional responsibility for social development. According to a journal article on the evolution of Scottish economic development2 the establishment of SE in particular marked a break from its predecessor (the Scottish Development Agency) which became strongly involved in a number of area-focused regeneration programmes, particularly around Glasgow.

Between 1991 and 2007, both SE and HIE were mainly operated via a decentralised structure of Local Enterprise Companies (LECs). When Business Gateway was introduced in 2003, it was also initially delivered by this network of LECs, as an extension to the Small Business Gateway. However, the then newly elected Scottish National Party (SNP) administration in 2007 embarked on a restructuring of the enterprise networks shortly after coming to power:

This abolished the LECs with the majority of their functions transferred upwards to the more centralised economic development agencies, although their remits for local economic development (or ‘regeneration’) and small business support were passed to local authorities.

Training and skills functions became the responsibility of a new national skills agency (Skills Development Scotland).

These changes were justified by the Scottish Government3 on the grounds of eliminating ‘duplication and unnecessary bureaucracy’ seen as resulting from the existence of 21 separate LECs, and focusing the agencies on ‘their core purpose of assisting economic development in Scotland’.

According to Clelland, these reforms reduced the role of national bodies in economic development at a local level, as SE in particular became more focused on delivering the Scottish Government’s national priorities.

The impacts of this were geographically uneven, however, with the initial loss of local skills and expertise less significant where councils had strong economic development services, and national agencies retaining a key role where economic development projects related closely to national priorities such as national growth sectors . Overall the 2007 reforms can be seen as a further ‘hollowing out’ of the intermediate regional scale between local authority and the Scottish levels.

Since the 2007 reforms, the economic development landscape had been relatively unchanging, until the advent of the Enterprise and Skills Review in 2016, and the subsequent launches of the South of Scotland Enterprise (SOSE) and the Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB) in 2020.

Economic development and enterprise agencies

Scotland's three economic development and enterprise agencies (Scottish Enterprise (SE), Highlands and Island Enterprise (HIE), South of Scotland Enterprise (SOSE)) deliver similar types of activity, including supporting businesses, sectors and infrastructure projects, and influencing economic development decisions. Both HIE and SOSE's distinct geography and additional remit to support communities means that their customers and rationale for support can differ to that of SE.

Scottish Enterprise

Scottish Enterprise (SE) is an executive Non-Departmental Public Body of the Scottish Government and was established under the Enterprise and New Towns (Scotland) Act 19901 for the purposes of furthering the development of Scotland's economy. This Act defines SE's key functions as:

furthering the development of Scotland's economy - including providing, maintaining and safeguarding employment

promoting Scotland's industrial efficiency and international competitiveness

furthering improvement of the environment of Scotland, including supporting Scotland's transition to a low-carbon economy.

SE’s duties are as determined by Scottish Ministers under Section 24 of the Act. A range of general and specific powers are set out in full in Section 8 of the Act.

SE’s Business Plan 2021-222 sets out the purpose, focus, and delivery activities for the period. SE’s plan builds on the strategic approach set out by the Scottish Government in its response to the Advisory Group on Economic Recovery report3, the Enterprise and Skills Strategic Board’s Labour Market Sub Group report4 and the Logan Review5. It also reflects the Interim Guidance Letter issued by the then Cabinet Secretary for Economy, Fair Work and Culture.

In recent years, SE had focused their efforts on supporting a segmented group of businesses and favoured sectors. However, there has been a recent shift in the way they work with more of an emphasis on the whole economy. According to SE6 this "has meant working with business to create more, quality jobs with a focus on helping reduce poverty and supporting businesses, communities and families across Scotland".

SE has £405 million of planned expenditure in 2021-22, of which £312 million will be covered via Scottish Government funding. The remainder will be covered by other business income related to property and investment funds.

Highlands and Islands Enterprise

Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE) is an executive non-departmental public body of the Scottish Government. HIE acts as a public agency with a statutory duty to undertake economic and social development within the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. HIE was established in 1991 in accordance with the provisions of the Enterprise and New Towns (Scotland) Act 19901. The legislation defines HIE’s key functions as:

preparing, concerting, promoting, assisting and undertaking measures for the economic and social development of the Highlands and Islands

enhancing skills and capacities relevant to employment in the Highlands and Islands

furthering improvement of the environment of the Highlands and Islands.

HIE’s duties are determined by Scottish Ministers under Section 24 of the Act, and a range of general and specific powers is set out in section 8.

HIE’s Operating Plan 20212 sets out their vision, focus, priorities, and activities for this period. The Operating Plan builds on the strategic approach set out by the Scottish Government in its response to the Advisory Group on Economic Recovery report3, the Enterprise and Skills Strategic Board4 and the Logan Review5 and reflects the interim guidance issued by the Scottish Government in March 2021.

HIE has budgeted for spend of £68 million in 2021-22, of which the majority is funded via Scottish Government funds.

South of Scotland Enterprise

South of Scotland Enterprise (also known as SOSE) launched officially on 1 April 2020 as the new Economic and Community Development Agency for Dumfries and Galloway and Scottish Borders.

The creation of this new agency with the ability to ‘do things differently’ was presented as a response1 to the ‘unique challenges’ faced by the region – an implicit acknowledgement that the approaches common to many economic development interventions may be less appropriate to rural regions2 . In the South of Scotland, this has been manifested in a perception that the area was disadvantaged relative to the Highlands and Islands by the lack of an agency with a broader community development remit like HIE, and a more general feeling that the South did not enjoy the same level of national profile and resources as the Highlands despite facing similar challenges of rurality and remoteness

The South of Scotland Enterprise Act 20193 was passed by the Scottish Parliament in June 2019 and provides the legal framework. The Act states that SOSE activities may involve taking action directed towards a wide variety of aims. Amongst those mentioned include:

supporting inclusive and sustainable economic growth

providing, maintaining and safeguarding employment

increasing the number of residents in the South of Scotland who are of working age

enhancing skills and capacities relevant to employment

supporting inclusive business models (such as social enterprises and co-operatives of any kind)

promoting digital connectivity

supporting the transition to net-zero

promoting improved transport services and infrastructure

supporting communities to help them meet their needs

maintaining, protecting and enhancing the natural and cultural heritage and environmental quality of the South of Scotland.

It is worth noting in terms of the aims of SOSE that some fall within the remits of other organisations. For example those relating to skills enhancement and business start-ups have been important functions of Skills Development Scotland and local authorities, respectively, since 2008. The inclusion of these aims within the Act underlines the fact that a number of other public bodies operating in the south, not just Scottish Enterprise, were impacted by the creation of the SOSE.

The SOSE Operating Plan 2021-224 provides details on the agency’s priorities for the period. Legislation requires SOSE to publish an Action Plan setting out in detail how it intends to achieve its twin aims of “furthering the sustainable economic and social development of the south of Scotland” and “improving the amenity and environment of the south of Scotland”. Given the priority of the need to support businesses through the COVID-19 pandemic, the decision was made to defer production of the first Action Plan by a year to March 2022.

SOSE planned expenditure for 2021-22 is £33.2 million, the majority of which is funded by the Scottish Government.

Local government

Scotland's 32 local authorities play an important role in economic development. In partnership with organisations across all sectors, local authorities will often have economic development plans and work to maximise economic benefits through their strategies, decision making, investment and services.

Local authorities in Scotland have direct responsibilities for the delivery of business advice and support services, mainly via Business Gateway, and for local economic development, including employability services and local area regeneration. They are also responsible for a wider range of services and functions which impact directly on the growth of the economy, including:

planning, roads and transport, environmental health, education and childcare, events and tourism, community development and culture and leisure services

the delivery of City and Growth Deals and the development of broader regional economic partnerships

developing strong linkages between economic development and wider priorities in Scotland at national and local levels such as addressing inequalities, child poverty, connectivity, climate change and improving outcomes

contributing to the delivery of a range of national performance framework outcomes, including ‘we have a globally competitive, entrepreneurial, inclusive and sustainable economy' and 'we have a thriving and innovative businesses, with quality jobs and fair work for everyone’.

The Scottish Local Authorities Economic Development Group (SLAED) is a network of senior officials from economic development teams across all Scottish local authorities. The SLAED Strategic Plan 1 demonstrates the collective weight of councils’ contribution to the sector - employing some 1,200 economic development staff, supporting over 14,000 businesses each year and assisting around 16,500 people into jobs annually.

Indicator Framework

The SLAED Indicators Framework1 was designed to provide consistent data and evidence on what councils throughout Scotland are delivering as local economic development organisations. SLAED highlight in considering a consistent set of indicators for local authorities it is important to be aware of the different economic circumstances of individual areas. Accordingly, the challenges, opportunities and responses will also be different across councils. Councils do not deliver exactly the same economic development activities, therefore direct comparisons of delivery and performance can be difficult to make.

There are currently 31 indicators included within the SLAED Indicators Framework and these are classified into five broad categories: Input Indicators, Activity Indicators, Output Indicators, Outcome Indicators and Inclusive Growth Indicators.

Data for 16 of the indicators is collected from publicly available sources such as ONS, NOMIS and the Scottish Government, and a further seven are collected from other agencies including the Business Gateway National Unit, Scottish Enterprise, Highlands and Islands Enterprise and the Supplier Development Programme (SDP).

This approach is designed to minimise the reporting burden on councils and means they are only required to report on the data that they individually collect and hold. The most recent Indicator Framework can be accessed via the SLAED website. It is not explicitly stated how the SLAED Indicators Framework is linked to the National Performance Framework.

Budget

The SLAED Indicators Report 2019-201 provides an estimate of economic development expenditure in 2019-20. This expenditure is extracted from the Local Finance Return (LFR) data, which is supplied by councils to the Scottish Government and includes both economic development and tourism capital and revenue spend. In 2019-20, according to SLAED overall estimated expenditure by councils was £564 million:

The total estimated capital spend in Scotland was £240 million and estimated revenue spend was £324 million.

The total economic development spend for 2019/20 was £534 million and tourism spend was £30 million .

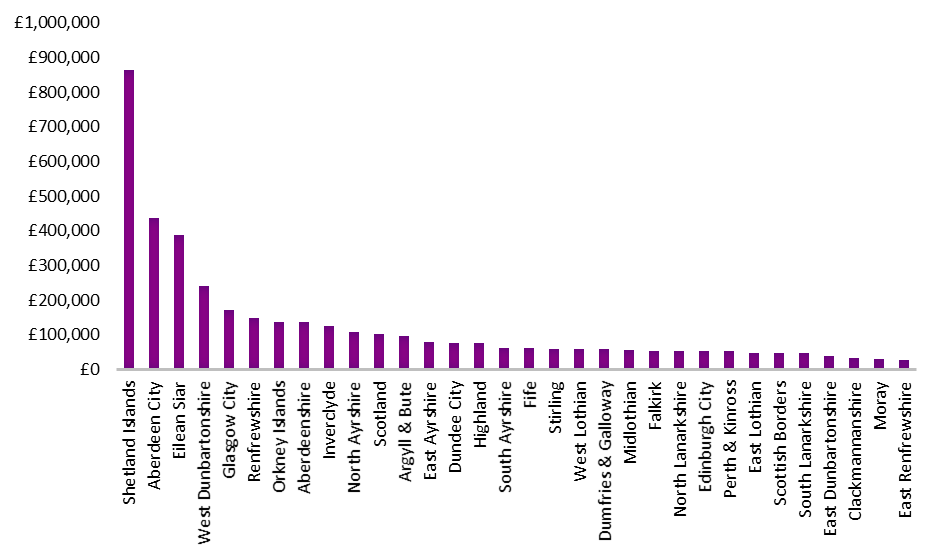

The below chart shows Investment in "Economic Development & Tourism per 1,000 Population in 2019/20". This data was sourced from the Improvement Service Local Government Benchmark Framework2.

Economic development activity doesn't have a ring-fenced budget and this makes local economic development budgets vulnerable to financial pressures, including retrenchment.

Business Gateway

Business Gateway (BG) is Scotland’s national business advice service, offering free advice and support to anyone starting a new business, as well as existing businesses with the ambition and potential to grow. BG is delivered and funded by local authorities throughout Scotland.

BG’s service includes publicly funded local workshops, one-to-one support from business advisers, extensive online resources and expert support on topics including innovation, exporting, finance and new markets. Additionally, BG works closely with national and regional economic development organisations, including Scottish Enterprise, Highlands & Islands Enterprise and Scottish Development International, to provide growing businesses with specialist support and financial assistance.

The Business Gateway National Unit is located within COSLA and provides national functions to support local authorities in the delivery of services at a local level.

In 2019, the Session 5 Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee published a report1 from their inquiry on SME business support with a focus on Business Gateway. The report provides more information around:

alignment and accountability

targets and performance

budgets

enterprise culture.

Regional Economic Partnerships

Regional Economic Partnerships (REPs) are collaborations between local government, the private sector, education and skills providers, enterprise and skills agencies, and the third sector.

The Scottish Government has encouraged the development of REP arrangements, since 2017, which are self-assembled around the bespoke requirements of particular regions. These build and expand on the experiences, structures and learning from early City Deals. It is envisaged that these partnerships will evolve over time and will be underpinned by the participation of the region’s key private, public and third sector interests including Community Planning Partnerships (CPP), universities and colleges.

The Scottish Government was of the view1 that REPs bring together regional interests, focusing and aligning resources, sharing knowledge, and identifying new joined-up plans to accelerate inclusive economic growth at a local, regional, and national level.

Prior to publication of the Enterprise and Skills Review and establishment of the city region and growth deal programme in Scotland, a range of local and regional economic partnerships were in place. Many of these continue, some new partnerships have emerged via City Region and growth deal activity and others have been formed. Scotland's REPs formed and under development include:

Glasgow City Region

Aberdeen City and Shire

Edinburgh and South East Scotland

Stirling & Clackmannanshire

Tay Cities Partnerships

Ayrshire

Inverness & Highlands

South of Scotland

The Islands

Argyll & Bute

Falkirk

Moray.

Scottish National Investment Bank

The Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB) was officially launched on 23 November 2020. A national investment bank, at the most basic definitional level, is a bank created by a country's government, that provides financing primarily for the purposes of economic development of the country.

It is the UK’s first mission-led development bank and it is being capitalised by the Scottish Government with £2 billion over ten years. The Bank’s missions1will focus on supporting Scotland’s transition to net zero, extending equality of opportunity through improving places, and harnessing innovation to enable Scotland to flourish.

It will provide patient capital – a form of long term investment – for businesses and projects in Scotland, and catalyse further private sector investment.

Skills Development Scotland

Skills Development Scotland (SDS) is Scotland’s national skills agency and a non-departmental body of the Scottish Government. Its purpose is to drive productivity and inclusive growth through investment in skills, enabling businesses and people to achieve their full potential.

SDS's Annual Operating Plan 2021-22 illustrates their plans to continue responding to the social and economic impacts of the pandemic. SDS's current strategic goals are:

all people in Scotland have the skills, information and opportunities to succeed in the labour market

Scotland’s businesses drive productivity and inclusive growth

Scotland has a dynamic and responsive skills system

SDS leads by example and continuously improves to achieve excellence.

SDS has a total budget of £264 million in 2021-22, of which £231 million is core funding from the Scottish Government. This is supplemented by in-year transfers of discrete funding to address Ministerial priorities.

Other economic development partners

In addition to the economic development organisations and partnerships outlined already in this section, other publicly funded organisations with a supporting role in economic development include:

VisitScotland - was initially established as the Scottish Tourist Board under the Development of Tourism Act 1969. The Tourist Boards (Scotland) Act 2006 formally changed the name of the Scottish Tourist Board to VisitScotland. Under the 1969 Act, the principal function of VisitScotland was to encourage British people to visit and to take holidays in Scotland, and to advise Government and public bodies on matters relating to tourism in Scotland. The Tourism (Overseas Promotion) (Scotland) Act 1984 provides the authority for VisitScotland to market Scotland overseas. VisitScotland’s core purpose, as set out in the Corporate Plan, is to deliver sustainable and inclusive economic growth throughout Scotland.

Transport Scotland - is the national transport agency for Scotland. It was established as an executive agency of the then Scottish Executive in January 2005. Its role was substantially expanded when it merged with the Scottish Government’s Transport Directorate in August 2010, while remaining as a separate agency. It seeks to deliver a safe, efficient, cost-effective and sustainable transport system for the benefit of the people of Scotland, playing a key role in helping to achieve the Scottish Government’s Purpose of increasing sustainable economic growth with opportunities for all of Scotland to flourish.

Scottish Funding Council (SFC) - is the national, strategic body that funds further and higher education and research in Scotland. The SFC is a Non-Departmental Public Body of the Scottish Government and was established on 3 October 2005. Its main statutory duties and powers come from the Further and Higher Education (Scotland) Act 2005. SFC's purpose is to create and sustain a world-leading system of tertiary education, research and innovation that changes lives for the better, enriches society and supports sustainable and inclusive economic growth.

Other partners involved in economic development include:

Economic Development Association Scotland (EDAS)

Improvement Service

SOLACE (Society of Local Authority Chief Executives)

Scottish Chamber of Commerce

Federation of Small Businesses Scotland

Scottish Council for Development and Industry (SCDI).

Measuring performance

Measuring the activities of the publicly funded economic development agencies against the Scottish Government’s budget and intended outcomes has been an ongoing challenge for Parliamentary scrutiny. Over 20 years ago in 1999, the Scottish Parliament's 'Enterprise and Lifelong Learning Committee1' concluded that:

There needs to be further development of a framework to measure the performance, efficiency and impact of economic development activities. The measures currently used are often too crude.

Despite the passing of time, a 2021 Legacy Report2 from a parliamentary committee concluded similar.

We have focused on the work of the enterprise agencies for our annual budget scrutiny. However, it has been challenging to establish outcomes for the spend of Scottish Enterprise. We have recommended, on a number of occasions, that action is taken to make the agency’s outcomes more tangible and measurable. This is a work in progress and one which we recommend our successor committee continues to monitor in the next session. Given the size of the spend, it is vital that Scotland’s enterprise agencies continue to be subject to rigorous scrutiny.

Audit Scotland highlighted similar concerns3 in 2016. They found that the economic development agencies had performed well against their agreed performance measures but it was not possible to accurately measure their contribution to the National Performance Framework (NPF). Audit Scotland did acknowledge that measuring the impact of economic development activity is difficult and that the agencies were pursuing a range of evaluation work to help demonstrate and improve their impact.

Linking budgets to outcomes is notoriously difficult, for who can say that complex social and economic outcomes are ever neatly attributable to any one budget line? However, it should still be possible for parliamentarians to gain an understanding of the extent to which a budget line has made a positive contribution to an outcome. After all, budgets buy inputs which should lead to measurable outputs. The effectiveness of these outputs can then be assessed against desired outcomes. A previous publication by SPICe “Linking budgets to outcomes – the impossible dream?” provides more context on this topic.

The Scottish Government in 2020 provided the following response when questioned about measuring the performance of the economic development agencies.

The enterprise and skills agencies are working with the Strategic Board Analytical Unit to continue to improve the consistency of measurement and further develop a shared understanding of common outcomes relating to the activities undertaken and expenditure and ensuring these are fully aligned with the National Performance Framework. There are long term objectives which require further development of potential new measurements and targets. The agencies continue to take a holistic approach to business support but appreciate this makes it difficult to isolate outcomes for particular activities and spend when they combine to create impact.

Still a cluttered landscape?

A 'cluttered landscape' has been something of a recurring theme when in it comes to economic development in Scotland. Over 20 years ago in 1999, the Scottish Parliament's 'Enterprise and Lifelong Learning Committee1' concluded that:

There is congestion within the field of local economic development in Scotland. There is confusion, overlap, duplication and even active competition between the many agencies involved.

When Business Gateway passed to local authority control in 2008, one of its intended purposes was to help businesses navigate the confused landscape and the myriad of programmes, services and providers. However, a 2019 Inquiry by the Parliament's Economy Energy and Fair Work Committee2 found that despite its intended purpose the 'confusion remains'.

These include: a range of enterprise agency interventions, city deals, private sector offerings, growth deals and regional partnerships. Beyond the economic development services offered at a local level by local authorities, the wide range of business advice and support provided by public, private and third sector partners was seen as an advantage and disadvantage to the current system.

In 2016, Audit Scotland stated3 the full range of public sector support for businesses is not known which creates a risk of duplication and inefficiency.

Public sector support is not well understood by businesses and there is scope to simplify arrangements and clarify roles and responsibilities. The landscape for supporting economic growth is changing and becoming more complicated, including reducing budgets, new financial powers for Scotland, the increasing prioritisation of ‘inclusive growth’, the creation of City Region Deals and the potential Islands Deal.

The 2016 Phase 1 Report of the Enterprise and Skills Review stated there were perceptions of a ‘cluttered landscape’ where unclear roles and responsibilities may lead to agencies duplicating activity or users finding it difficult to understand access criteria and the entirety of available support.

Over the last six years we have seen some attempts at rethinking the ‘enterprise and skills’ landscape in Scotland, via the activities of the Enterprise and Skills Strategic Board. But has this achieved the change that was originally anticipated - The Enterprise and Skills Review – achieving its aspirations? – some would argue the landscape is still cluttered.

It should be highlighted here that the Enterprise and Skills Strategic Board has been considering how the Board’s original missions remain relevant in light of COVID19 and whether they should change to support the recovery. Work is also underway to investigate new or improved ways the Board and enterprise and skills agencies can work together to generate the greatest impact, reflecting the original objective of the Board to get the maximum value from collective investment. A refresh of its Strategic Plan is expected later in 2021.

Economic development strategy in Scotland – is there one?

Economic development was one of the policy areas devolved to the Scottish Parliament when it came into existence in 1999. The Parliament inherited a set of arrangements that saw responsibility for economic development shared between local authorities and the then two enterprise agencies – structured as regional networks. However, the economic development landscape has since evolved as reflected here and in the previous chapter on the main actors.

Supporting economic growth is complex, as Audit Scotland1 point out many factors influence the economy and most are outside the control of the public sector. A range of partners and partnerships are involved. The public sector’s role is to create the conditions that encourage business growth, stimulate demand for goods and services and increase the economic participation of individuals.

There is no agreed definition of economic development activity, as highlighted in the opening section of this report. However, since devolution in 1999 Scotland has had some form of economic development strategy - Scotland’s earlier strategies were framed as economic development strategies but more recently just tend to be called economic strategies.

This chapter provides: an overview of these past strategies; explores the current economic development strategy; looks in more detail at a regional approach within Scotland; and how both Scottish and UK Government policies align.

Looking back – 22 years of economic strategies

In 2019, SPICe published ‘Evolution and dilution in devolution: economic policy in Scotland1’ to mark 20 years of the Scottish Parliament. This publication detailed that there had been ten strategies, plans and frameworks to develop Scotland’s economy since 1999.

The Way Forward: Framework for Economic Development in Scotland was introduced by the then Scottish Executive, in 2000. This was built on by the first economic strategy for devolved Scotland, A Smart, Successful Scotland, introduced in 2001. The strategy and framework were refreshed in 2004.

Shortly before the onset of the financial crisis and recession in 2007, the Scottish Government published the Government Economic Strategy. The Government then published an Economic Recovery Plan in 2008, with the Government Economic Strategy updated after the 2011 election.

The Government then published Scotland’s Economic Strategy in 2015. This 2015 strategy is currently Scotland’s main economic policy document, but there has been continued policy churn to support this since. The Enterprise and Skills Review was launched in 2016, resulting in the Enterprise and Skills Board: Strategic Plan in 2018. And late 2018 saw the arrival of the Economic Action Plan. Though this could be classed less a plan, and more a website, capturing a range of initiatives and support linked to the economy.

A Fraser of Allander blog described Scotland’s economic policy landscape as complex and suggested that this can lead to confusion, a lack of alignment, duplication, weakened accountability, and makes evaluating what actually works all the more difficult. The blog provided the following advice.

Strategies and advisory groups are no substitute for good policy delivery based upon evidence and data. Back in 2007, the Scottish Government promised a streamlined and effective policy landscape for the economy. Ten years later it may be time to look at this again.

The launch of the Economic Action Plan in late 2018 was seen by some as a response to this criticism.

In June 2021, the new Cabinet Secretary for Finance and Economy committed that in the first six months of the new parliamentary session to deliver a new 10-year national strategy for economic transformation.

Trends in policy

The contents of Scotland’s economic strategies, plans, and frameworks has evolved with each iteration since devolution.

The vision of the 2000 economic framework was “to raise the quality of life of the Scottish people through increasing economic opportunities for all on a socially and environmentally sustainable basis”. This framework emphasised the importance of supply side drivers of productivity such as innovation and skills, stressed the key role of market forces and offered the primary justification for policy intervention as market failure.

Scotland’s first post-devolution economic strategy, A Smart, Successful Scotland, was viewed as an attempt to promote a science-based economy. The implementation of the strategy led to the adoption of some major policy innovations, such as Intermediary Technology Institutes (ITIs). However, they didn’t stand the test of time and were abolished in 2010. An academic study concluded that ITIs “badly malfunctioned” and were “a spectacular failure”.

The 2004 update of the strategy had a much more explicit spatial dimension than its predecessor, with a focus on city regions and rural development, regeneration and strengthening communities. There were also two cross-cutting themes: sustainable development and closing the opportunity gap for people and places.

The 2007 strategy marked a step change in terms of coverage yet had large overlaps with the contents of the previous strategy and framework. Indeed, the biggest difference was the setting of specific targets. However, commentators at the time believed ambitious targets were not in themselves sufficient and the lack of clear and radical initiatives to achieve them was an important omission. The 2007 strategy also introduced the concept of the “key sectors” (which in the 2015 iteration would become “growth sectors”), the Arc of Prosperity countries, and bold targets around growth and productivity.

Compared with other governments at the time, the Scottish Government had a narrower range of options available to consider in terms of promoting economic recovery for the 2008 Recovery Plan, as it had no powers over monetary policy and limited fiscal powers. The Plan had three broad themes: supporting jobs and communities, strengthening education and skills, and investing in innovation and the industries of the future. The Scottish Government stated the Plan supported 15,000 jobs across Scotland. The financial crisis of 2008 highlighted the importance of responding flexibly to emerging pressures and challenges. It also emphasised the need to create an economy that was more resilient to shocks and economic uncertainty. Developing a more resilient and adaptable economy were the key aims of the 2011 strategy, reflecting the zeitgeist of the time.

The purpose of the 2015 strategy was to create a more successful country, with opportunities for all of Scotland to flourish, with sustainable economic growth remaining at the core. This strategy introduced the concept of the “4 Is” (investment, innovation, inclusive growth, internationalisation). Overall it was a broad, high-level strategy and did not set out in detail how underpinning policies and initiatives will be implemented.

The first strategy, following devolution, started out as direction for the enterprise networks. Successive strategies gradually tackled wider social challenges and offered direction for the wider public sector, eventually arriving at the “One Scotland Approach” in the 2015 Strategy. SPICe’s 2015 briefing looks in more detail at the evolution of economic strategies.

Over last five years we have seen some attempts at rethinking the ‘enterprise and skills’ landscape in Scotland. But did this achieve the change that was originally anticipated - The Enterprise and Skills Review – achieving its aspirations?– some would argue the landscape is still cluttered.

Over the last two decades, Scotland’s economic policy landscape has evolved from a narrow enterprise agency approach to a wider whole government approach. SPICe’s 2019 blog stated that while there is merit to this more holistic approach to economic policy, it has weakened accountability, and makes evaluating what actually works all the more difficult. There have been no formal procedures in place to form an overall assessment of the success of successive economic strategies.

While as Audit Scotland point out the economic strategy states that progress will be measured through the National Performance Framework (NPF). The NPF measures progress towards outcomes but it does not have targets nor measure the contribution of policies and initiatives to delivering these outcomes. The Scottish Government has refreshed its economic strategy twice since 2007 and has developed and refreshed underpinning plans and policies. But it has not collated progress against these, or the contribution made by individual public bodies, to form an overall assessment of progress against the priorities in its previous economic strategies.

Current focus

Scotland’s Economic Strategy (2015) structured around the four Is (innovation, internationalisation, investment, inclusive growth) and the Economic Action Plan (live dynamic document) are currently the main documents that guide economic policy in Scotland.

However, as highlighted previously, the Scottish Government has committed to deliver a new 10-year national strategy for economic transformation in the first six months of the new parliamentary session. This would suggest that Scotland will have a new economic strategy before the end of 2021. However, we can get a feel for current Scottish Government thinking around economic development from a few different sources, as explored below.

The Scottish Government's Economic Development Directorate states:

We play a fundamental role in delivering the Scottish Economic Strategy, through increasing sustainable economic growth.

We are responsible for:

encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship and supporting key sectors

working with other public, private and third sector stakeholders to deliver the Scottish Business Pledge

overseeing a successful major events programme and a vibrant cities agenda

boosting productivity, competitiveness, sustainable employment, and workforce engagement and development

funding City Region Deals to attract investment and create jobs

collaborating with partners through Clyde Mission to drive sustainable and inclusive growth

European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIFs), the European Union's way of investing in 'smart, sustainable and inclusive' growth in its member states.

Letters of guidance (these are Ministerial letters from the Scottish Government to public bodies setting out the general direction of travel that the public body should take across a range of activities) issued to the economic development agencies can provide useful insight on current policy thinking. The most recent interim letter of guidance were issued in March 2021.

During 2020 the Scottish Government issued two letters of guidance to the economic development agencies reflecting the rapidly changing situation caused by COVID-19.

Interim letters of guidance in April 2020 asked the agencies to stop all but the most critical ‘business as usual’ activity, re-prioritise and work collaboratively to meet the immediate challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic.

More detailed guidance in December 2020 pointed to work being taken forward to support the economic recovery, in line with the commitments in the 2020 Programme for Government. However, the sharp deterioration in the pandemic towards the end of 2020 made it necessary for the Scottish Government to impose new restrictions and the agencies were again asked to re-direct resource to help provide vital support for individuals, communities and businesses.

Further interim letters of guidance issued in March 2021 recognised the need for the agencies to continue to be responsive in the face of changing circumstances, whilst highlighting priority areas of work for the short to medium term with expectations of more detailed guidance to be issued later in 2021.

Reading across the March 2021 guidance letters to the agencies (SE, HIE, SOSE) reveals the following themes.

Economic recovery - the 2020 Programme for Government underlined the need for our recovery from COVID-19 to be "led by green growth and to also promote fairness and wellbeing. It committed to: a national mission to create new jobs, good jobs and green jobs, with a particular focus on young people; promoting lifelong health and wellbeing; and advancing equality and helping our young people grasp their potential".

Regional delivery - supporting the implementation of growth deals and development of associated economic partnerships or cross authority collaborations. It is intended regional delivery programmes will act as a catalyst for realising longer term ambitions to renew and grow regional economies by encouraging business growth and protecting and creating high quality jobs.

Supply chain development – the Scottish Government believe improving the capacity, capability and resilience of Scottish supply chains is key to economic recovery and to supporting the national mission to create jobs. The Supply Chain Development Programme is working to analyse existing supply chains, build better and more strategic supply chains and leverage Scotland’s public sector procurement.

Climate change and COP26 - “Team Scotland” delivery of Scottish Ministers’ objectives for COP26, including: mobilising businesses to go further and faster to net zero emissions; supporting growth opportunities through investment and exports; showcasing private sector leadership on climate change; and supporting communications around the summit.

Implementation of the national programmes – seven national programmes focusing on Digital Scale Up Level Up, Health for Wealth, Scotland in Space, Future Healthcare Manufacturing, Zero Emissions Heavy Duty Vehicles, Decarbonising Heat, and Hydrogen Economy.

Early stage support - focus on supporting a dynamic, ambitious and diverse entrepreneurial community and providing investment into ambitious, early stage companies from start to scale up, creating a pipeline of growth opportunities. Strong collaboration required with SNIB.

In terms of the COVID-19 pandemic and economic recovery, in August 2020, the Scottish Government published a response to the Advisory Group on Economic Recovery report “Towards a Robust, Resilient Wellbeing Economy for Scotland: Report of the Advisory Group on Economic Recovery.1”

The AGER report suggests that:

Scottish Government considers using the ‘Four Capitals’ approach in forming its economic strategy, both in the recovery phase and for the longer term. This will require considerable technical work in order to measure and monitor our assets, notably in natural capital, as we have already noted: but we think that the potential long-term benefits in terms of policy provide sufficient justification.

The “four capitals” refers to Scotland’s major capital assets: natural capital, social networks, collaboration and interaction, human skills and knowledge, and economic capital.

The Scottish Government accepted all recommendations from the Report and identify six key areas for action:

business recovery and sustainable, green growth

engagement and partnership approach

employment, skills and training

supporting people and places

investment-led growth for wellbeing

monitoring progress and outcomes.

The Scottish Chamber of Commerce stated the following about the Scottish Government response to the AGER:

It contains some strategic and medium to long-term priorities, but as yet there is not the detail, the timeline and the action plans that we would have liked. However, it is our hope and desire that those will come forward.

The Scottish Government made a number of commitments and proposals as part of their response to the AGER report and in the Programme for Government 2020-21 that sought to support a green recovery. In particular, the Programme for Government highlighted commitments to:

create a £100 million Green Jobs Fund

allocate £60 million to support industrial and manufacturing decarbonisation

maintain current levels of spend on active travel at £100million per year

uplift spending in Heat and Energy efficiency from £112m in 2019-20 to £398m p.a. in 2025-26

continue to develop the Agricultural Transformation Fund

bring forward recommendations for new mechanisms of agricultural support

provide an additional £100 million to support new forestry planting.

These themes were continued in the 2021-22 Programme for Government (PFG)'A Fairer, Greener Scotland'. Unsurprisingly the “foremost priority” was recovery from the pandemic and alongside this, the 2021-22 PFG focused on six long-term priorities:

“Caring Nation: setting out a new vision for health and social care”

“Land of Opportunity: supporting young people and promoting a fairer and more equal society”

“Net Zero Nation: ending Scotland’s contribution to climate change, restoring nature and enhancing our climate resilience, in a just and fair way”

“An Economy that works for all of Scotland’s People and Places: putting sustainability, wellbeing and fair work at the heart of our economic transformation”

“Living Better: supporting thriving, resilient and diverse communities”

“Scotland in the World: championing democratic principles, at home and abroad”

For more detail on the PFG, see the SPICe blog 'Programme for Government 2021-22: A fairer, greener Scotland?'.

A more regional approach?

An article from the Local Economy Policy Unit Journal1 states there have been a wide variety of approaches adopted to local and regional economic development. Recent years have brought something of an upturn in regionalism in Scotland. This agenda has been given recent impetus by the development of City Region and Growth Deals, and by the recommendations of the Scottish Government’s Enterprise and Skills Review for the establishment of Regional Economic Partnerships (REPs).

The Enterprise and Skills Review was clear that the REPs should be self-assembled according to the needs of different regions and there were no predefined regional geographies. The Review also committed the economic development agencies and stakeholders to working regionally.

REPs presented a mechanism for the Scottish Government and relevant agencies to engage more with regional needs and circumstances – a movement towards the language of more ‘place-based’ development. However, as Clelland1 points out there are also some clear expectations for REPs.

...they will, for example be expected to have private sector representation, and to use the inclusive growth tool to inform any future funding bids. The language of partnership, collaboration and flexibility therefore sits somewhat uneasily alongside a fairly explicit reminder of where control over resources lies – while there is no statutory duty for local actors to form these partnerships, the relatively centralised nature of government within Scotland gives the Scottish Government significant leverage in shaping the metagovernance of regional economic development and in setting the ‘rules of the game’. The introduction of REPs also appears likely to reinforce the significance of the new geographies emerging through the growth deals, as these will no longer simply be groups of local authorities coming together to deliver specific sets of projects, but will become spaces for wider ranging strategic collaboration, including being responsible for the preparation of Regional Economic Strategies.

Scotland's economic development agencies have committed to a more place-based approach in recent years (well namely Scottish Enterprise as both Highlands and Islands Enterprise and South of Scotland Enterprise have an inherent regional remit). In 2019, Scottish Enterprise announced a pivot back to a more wide-ranging role in supporting communities as well as businesses, with a clearer social dimension. One commentator noted, in 2007 Scottish Enterprise had moved away from that role to focus on a limited number of companies with high-growth potential, so the 2019 pivot was quite a U-turn.

More recently the Advisory Group in Economic Recovery (AGER) report recommended that:

The economic development landscape in Scotland should pivot to a more regionally focused model in order to address the specific new challenges of economic recovery. This model should be tasked to drive delivery of place-based and regional solutions, especially the City-Region Growth Deals

The Scottish Government should support a renewed focus on place-based initiatives, building on lessons learned from initiatives on Community Wealth-Building. It should also accelerate investment in housing, in particular through the Scottish National Investment Bank.

In response to the AGER report, the Scottish Government committed to:

work with Scottish Enterprise to support their shift to a more bespoke, regionally-focussed approach across the SE area by the end of 2022

through Regional Economic Partnerships, work closely with local government, Enterprise Agencies and other key economic actors, including the private sector, to take a focussed “taskforce‟ approach to driving place-based recovery and renewal.

This more regional approach to economic development has also gained some traction at a local government level. A 2019 report looking at Regional Approaches to Maximising Inclusive Economic Growth in Scotland found that:

There is broad agreement around the rationale for regional working based on functional economic geography, mutual benefit and the potential to deliver improved outcomes. For some, regional approaches are also about building more resilient public services for the future.

The pace and extent of progress in developing regional approaches is varied across the country, and a small minority of councils are less committed to a regional model, preferring instead to pursue a more local agenda. This should not be surprising. Regional working in the context of inclusive economic growth is still in its early stages, and collaborative working takes time to establish. It may also be the case that regional approaches make more sense in some areas than others. In particular the notion of functional economic geography may be less compelling in some of the more rural and remote parts of the country.

Capacity and capability are real challenges for many authorities. As a discretionary service, economic development has borne significant reductions in budget, and resources are thinly stretched. The City Region and Growth Deals have also made substantial demands on councils, and the further development of regional collaborative approaches will need investment and action to support the development of the thinking and skills that will support regional collaboration.

Frictions or synergies in strategy?

The previous sections of this briefing outline a constant process of reorganising and rescaling governance arrangements across the economic development landscape over the last two decades in Scotland. This has been shaped by actors at local, Scottish and UK levels.

Does this result in frictions or synergies for different places within Scotland to pursue economic development?

A Scottish Parliament Inquiry into City Deals in 2018 concluded that:

In our view, there is a danger that the often confused and cluttered policy landscape at local government, Scottish and UK levels runs the risk of reducing the impact that can be achieved from the deals. At present, there are too many overlapping and competing initiatives and a mismatch between the objectives of local government and of the two governments.

The next chapter in this briefing provides an overview of some of the key funding interventions currently in delivery or planning across Scotland's economic development landscape. It illustrates the varying policy levers both the Scottish and UK Governments are pursuing, which are not always fully aligned. The economic development landscape is complex and this complexity isn't necessarily helped by the varying intentions of different public sector actors.

Funding Programmes

A selection of some of the key funding programmes which support economic development in Scotland are described below.

These include the EU Structural funds, and their proposed replacements, this year, the Community renewal Fund, and next year, the Shared Prosperity Fund, as well as the (UK wide) Levelling Up fund. The note also looks briefly at Green Ports (the proposed Scottish version of Freeports), the City and Regional Growth Deals, enterprise areas, and some other programmes such as the Green Jobs Fund, the National Manufacturing Institute, and a Women's Business Centre.

European Structural Funds

EU Structural funds have been a significant contributor to local and regional economic development in Scotland for the last 40 years1Now the UK has left the EU, it will receive no funding under the European Union’s new financial framework (running from 2021 to 2027), although under the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement, it can continue to receive some funding until December 2023 if it was committed under the 2014-2020 programme.

This SPICe briefing on the Structural funds2 and subsequent SPICe blog3 provide more detail on how they have worked in Scotland. Under the EU’s 2014-2020 budget framework, Scotland was allocated €872m (or around £782m in January 2014 exchange rates), at the outset of the programme, and as at 24 March 2021 the Scottish Government had allocated £624m (with the final figure expected to be higher).

Shared Prosperity Fund

In Session 5 the Scottish Parliament’s Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee carried out an inquiry into European Structural Funds1 and made a number of recommendations about what the future Shared Prosperity Fund should look like. In summary, these included a continued focus on people and places, time frames running beyond electoral cycles, and partnership working. Funding should not be reduced from the structural funds, Scotland should decide how to distribute these funds internally, and there should be a seamless transition to the new regime. The Finance and Constitution Committee also conducted its own inquiry into the Funding of EU Structural Fund Priorities in Scotland, post-Brexit. Recommendations included those on managing the transition to the new fund, as well as building on the "best parts of the current approach" and that "the decision taking powers that the Scottish Government currently exercise under the EUSF should not be reduced under the UKSPF".

The Scottish Government produced its own proposals for a Scottish replacement for the EU structural funds2 , and how these might be managed. This followed a public consultation, and work of an expert steering group, chaired by Professors John Bachtler and David Bell. Four key areas were considered: Funding and Allocation; Governance and Delivery; Policy Alignment; and Monitoring and Evaluation

The proposal would involve (at least) a five-year programme, led by the Scottish Government, with regional partnerships “free to allocate money as they wish in their regions, guided by principles…”. Funding would be distributed using a “transparent, needs-based regional allocation model”. The areas would “align with the Highlands and Islands and South of Scotland Enterprise areas and with emerging Regional Economic Partnership Areas in the rest of the country”.

However, it’s still not clear exactly what form the UK government wish the new fund to take. In November 2020, the UK Spending Review 20203 did say that:

The fund will “operate UK-wide” using powers in the UK Internal Market Bill, and that investments and programmes will display common branding

The UK government also identified two strands of funding, perhaps not dissimilar to the split between European Regional Development funding (ERDF) and European Social Fund funding (ESF) that came through the EU structural funds, with emphasis added:

A portion of the UKSPF will target places most in need across the UK, such as ex-industrial areas, deprived towns and rural and coastal communities….

A second portion of the UKSPF will be targeted differently: to people most in need through bespoke employment and skills programmes that are tailored to local need. This will support improved employment outcomes for those in and out of work in specific cohorts of people who face labour market barriers

On 7 September 2021, the Chancellor launched a spending review alongside an Autumn Budget for 2022/23, concluding on 27 October, and explained that the review will deliver priorities including through:

Levelling up across the UK to increase and spread opportunity; unleash the potential of places by improving outcomes UK-wide where they lag and working closely with local leaders; and strengthen the private sector where it is weak.

How much funding will be available?

The Scottish Government1 has called for “the full amount of funding due to Scotland” which they calculate as being at least £183 million per year (to replace the EU Structural Funds, and the European Territorial Cooperation and LEADER programmes), equating to a 7-year replacement programme of £1.283 billion

The UK government said in its Spending Review 2020 (Box 3.1), said that it will “ramp up funding”, to “at least match current EU receipts”, which they calculate will mean, on average reaching around of £1.5 billion a year across the UK.

It is currently not clear how this will be apportioned across the UK or how much of this will be allocated to Scotland.

How will the devolved administrations be involved?

The UK government has said1 that it will:

… engage the Devolved Administrations and local partners as we develop the UK Shared Prosperity Fund’s Investment Framework...” and that they have “demonstrated this commitment by confirming that the Devolved Administrations will have a place within the governance structures.

However, the Scottish Government said that, as at March 2021, the quality of engagement with the UK government at official and Ministerial level had, so far, been “hugely disappointing.”2

Some issues and questions

The Scottish Government’s Just Transition, Employment and Fair Work Minister Richard Lochhead MSP wrote to the UK Government (July 2021), stating that he was “beyond disappointed” by the level of engagement in relation to the Shared Prosperity Fund, (and other funds), whilst also setting out some “principles for future engagement”, which would involve treating the Scottish Government as a “full and equal partner”. These included:

a clear role for Scottish government officials in the development, delivery and decision making across all aspects of policy planning

agreement of Scottish Ministers before the UKSPF is launched

Scottish Ministers and officials to have a meaningful role in the governance of the Programme in both Scotland and at UK level

A formal framework for decisions on funding across the UK, agreed with the devolved administrations.

The Minister raised a number of questions, including those relating to:

the geographies the UKSPF will be aligned to

use of a needs based versus competitive approach in the allocation of funding, and associated funding guarantees for Scotland, including how to ensure that “no part of the UK will lose out on funding”

Whether funding will be on a multi annual basis and process to draw down funding

Governance arrangements and hierarchy, and relative status of Scottish devolved policy frameworks, including how bodies such as enterprise agencies, Skills Development Scotland and Transport Scotland, will be engaged.

Evaluation, monitoring and audit of individual projects and overall programme

Whether the UKSPF will operate on exactly the same basis across all the other nations

The House of Commons Scottish Affairs committee published the report of its inquiry into the Shared Prosperity Fund (July 2021). Its recommendations included the following (emphasis added):

The UK Government must launch a formal, public consultation on its proposals for the UKSPF by autumn 2021.

We urge the UK and Scottish Governments to work constructively together in the design and delivery of the UKSPF.

The UK Government’s multi-year funding profile should clarify how much funding will be available each year for the UK and for Scotland for at least the first five years of the UKSPF.

The UK Government must clarify how and when EU rural development funding, including the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and European Maritime Fisheries Fund (EMFF), will be replaced.

In March 2022, a year after it began, the UK Government should evaluate the Community Renewal Fund and publish its findings on how well the fund has operated. This evaluation should highlight implications for the design and delivery of the UKSPF.

The UK Government should ensure that its methodology and criteria for allocating UKSPF funds are clear and transparent

In its response to this Report, the UK Government should clarify how much funding has been given to local authorities in Scotland to help them build capacity in developing bids for the UKSPF.

The UK Government should prioritise academic research funding when allocating resources under the UKSPF. The UK Government should collaborate with the Scottish Government, to ensure that regions where structural funding for universities has brought significant regional benefits, are not disproportionally disadvantaged by the transition to the UKSPF.

We recommend that the UK Government evaluates the progress of the UKSPF after one year of operation and publishes a report, to ensure that funding is delivering the levelling up agenda by being allocated to the areas and sectors of greatest need.

A response from the UK government was due by 9 September 2021 (and as at 20 September 2021, was being reported as "overdue" by the committee).

A subsequent report from the Institute for Government (July 2021) concluded that the Fund “ risks damaging trust between the UK and devolved administrations and undermining the UK government’s key objective of binding the four nations of the UK closer together.”

The report suggests that the UK government ensures “greater consultation with the devolved nations, introduce clear spending criteria and set up a governance structure that allows the devolved nations to work as partners”. Specific recommendations include:

clear criteria for how spending under the UKSPF will be allocated,

Reduced bureaucracy for local recipients of funding

Improved consultation with devolved administrations as an immediate priority, including more sharing of information

avoiding duplication of spending

a governance structure for the UKSPF in which the devolved administrations participate as partners, and

consideration for a ‘match funding’ model for at least some projects in the devolved nations.

The Community Renewal Fund

The UKSPF is due to launch in 2022, and in the meantime a new fund, the Community Renewal Fund (CRF), is intended to support “a smooth transition”. The operation of the CRF will also provide some clues as to how the UKSPF will work. Its March 2021 prospectus1 sets out how “an additional £220m of investment” for the UK in 2021-22 (and only available in 2021-22) can be accessed and what it can be spent on.

The fund will also “help inform the design of the UK Shared Prosperity Fund through funding of one-year pilots” and enable the UK government to “work directly with local partners in each nation across the UK”.

The prospectus flags up what it says are some opportunities for improvements compared to EU structural funds including:

quicker release of funding

better targeting for places in need

closer alignment with domestic policies

reduced bureaucracy.

How will the CRF be allocated?

The CRF will involve a competitive process. Although there is “no pre-set eligibility”, 100 priority places have been identified in Great Britain “based on an index of economic resilience”, 13 of which are in Scotland.

Northern Ireland and Gibraltar are however not part of this competitive process and will receive a fixed allocation of £11 million and up to £0.5 million respectively. For Northern Ireland the UK government will oversee a project competition directly, whilst the UK government will work with the Government of Gibraltar to agree the delivery arrangements for Gibraltar.

Taking account of the above allocations, and up to £14 million that will be available to help places prepare for the introduction of the UK Shared Prosperity Fund, this means that around £194.5 million (of the £220m) will be available for distribution across England, Wales and Scotland.

How was the index to identify the 100 Priority Places created?

The methodology note for the Prospectus explains how an index score has been used, based on five criteria, with different weightings

Productivity (30%)

Skills (20%)

Unemployment Rate (20%)

Population Density (20%)

Household Income (10%)

There has been some surprise at the exclusion of some places from the priority list. For example, Ivan McKee MSP1 pointed to a lower priority given to a number of areas for CRF (as well as for the Levelling Up Fund), including Dundee, and the Highlands . The methodology note indicates that the index does indeed create “a diverse typology of places by targeting rural areas with low population density”.

What is the bidding process?

This is a UK wide competitive bidding programme for local authorities. Local authorities were required to invite proposals from within their area, appraise them and produce a shortlist for the UK government’s Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government by 18 June 2021. Lead local authorities in priority areas will receive some funding for “capacity building” to support the bidding process (drawn from the £220m CRF fund).

The UK government will appraise the bids, on the basis of the selection criteria, such as strategic fit, and deliverability. Where no distinction can be made between projects on the basis of selection criteria, then UK “Ministers can make decisions between projects based on what they consider the best value for money”. Successful projects were due to be announced from late July 2021 onwards, though as at September 2021, the Municipal Journal reported that the UK government had yet to announce which projects had won funding.

The Scottish Government told SPICe (May 2021) that it was not clear at that time what role it would play in the assessment of bids, other than assuring UK Government that there is no duplication of funding.

The prospectus identifies four investment priorities – skills/ local business/ communities and place/ and employment, with no ring-fencing across these priorities. Ninety per cent of funding (for this one-year scheme) is revenue funding. Bids should be no more than £3 million per place.

Levelling Up Fund

The prospectus for the Levelling Up fund was published in March 2021. It applies to the whole of the UK, and funds infrastructure of different types. It aims to bring together the Department for Transport, the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government and the Treasury “to invest £4.8 billion in high value local infrastructure”. In doing so, it says it will “remove silos between departments, allowing areas to focus on the highest priority local projects rather than shaping projects to fit into narrowly defined pots of funding”.

How much?

The UK Government has committed an initial £4 billion for the Levelling Up Fund for England over the next four years (up to 2024-25) and “set aside at least £800 million for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland”. The fund will “focus investment in projects that require up to £20m of funding”.

Who is involved?

The prospectus says

In England, Scotland and Wales, funding will be delivered through local authorities. The Scottish and Welsh Territorial Offices will be consulted in the assessment of relevant bids.

“Capacity funding” will also be allocated to local authorities most in need of levelling up in England, whilst it will also be allocated to all local authorities in Scotland and Wales, “to help build their relationship with the UK Government”.

The Prospectus puts the local MP “at the heart of its mission” and says

We expect Members of Parliament, as democratically-elected representatives of the area, to back one bid that they see as a priority.

As with the Community Renewal Fund, a different approach is being taken in Northern Ireland.

What projects will be funded?

The Prospectus says that priority for 2021-2022 will go to three themes:

smaller transport projects that make a genuine difference to local areas; town centre and high street regeneration; and support for maintaining and expanding the UK’s world-leading portfolio of cultural and heritage assets

Which areas will receive funding?

As with the Community Renewal Fund, an index has been created to rank geographical areas. In this case the index is based on:

need for economic recovery and growth

need for improved transport connectivity; and,

need for regeneration.

The methodology has been the subject of some debate, and for example the Good Law Project has mounted a legal challenge against the UK government.

All areas remain eligible for funding, but preference will be given to high priority areas. All Scottish local authorities will be provided with a capacity building grant – in this case of £125,000. The priority status of Scottish areas is set out below.

| Priority 1 | Priority 2 | Priority 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Dumfries and GallowayDundee CityEast AyrshireFalkirkGlasgow CityInverclydeNorth AyrshireNorth LanarkshireRenfrewshireScottish BordersSouth AyrshireSouth LanarkshireWest Dunbartonshire | Aberdeen CityAngusArgyll and ButeClackmannanshireEast LothianEast RenfrewshireFifeMidlothianMorayNa h-Eileanan SiarStirlingWest Lothian | AberdeenshireCity of EdinburghEast DunbartonshireHighlandOrkney IslandsPerth and KinrossShetland Islands |