Local government finance: concepts, trends and debates

This briefing provides a range of factual information and analysis on local government finance, including a profile of the local government budget over time. The debates around local government funding are summarised, including discussions of ring-fencing and budget changes. The briefing also includes a look at how COVID-19 affected the balance of local government funding in 2020-21. The focus of the paper is on the most common questions asked of SPICe by MSPs, and it also summarises recent committee sessions with Scottish ministers and COSLA.

Introduction

Local government finance is a technical and difficult area, and like much of public finance in Scotland, relatively few people fully understand it. Multiple complexities have developed over several decades - through reforms, negotiations and compromises by various tiers of government - and no doubt, were a new system to somehow be designed from scratch it would probably look a bit more straightforward.

Our MSPs scrutinise, debate and approve the annual local government allocations, so it is important that they understand the fundamentals of local government finance and are aware of the changes and trends that have happened over the past ten years. Furthermore, with council elections taking place next year, this briefing will hopefully help inform the voting public and the Scottish media about some of the key financial concepts and debates.

Local government finance is one of the most frequently contested areas in Scottish politics. This is mainly due to the fact that local authorities need Scottish Government funding, whilst the Scottish Government needs local authorities to deliver many of its national priorities. Both tiers of government have legitimate democratic mandates and are accountable to their electorates. Therefore, the annual budget process is where frictions between these two tiers most publicly, and most regularly, play out.

Since 2013-14 (the earliest comparison year used in this briefing), local government has argued for more money from the Scottish Government, and for more autonomy over how they spend it. At the same time, the Scottish Government’s annual allocations to local government have decreased in real terms (whilst their own budget has increased) and the proportion of Scottish Government allocation to local government which is ring-fenced has actually increased. This briefing explores these themes in more detail, setting out the arguments from both sides.

Executive Summary

This Briefing covers a lot of ground. However, the main points all Members should be aware of are:

Scotland’s local authorities spent a total of £23.9 billion in 2019-20, the equivalent of 14% of Scotland’s GDP.

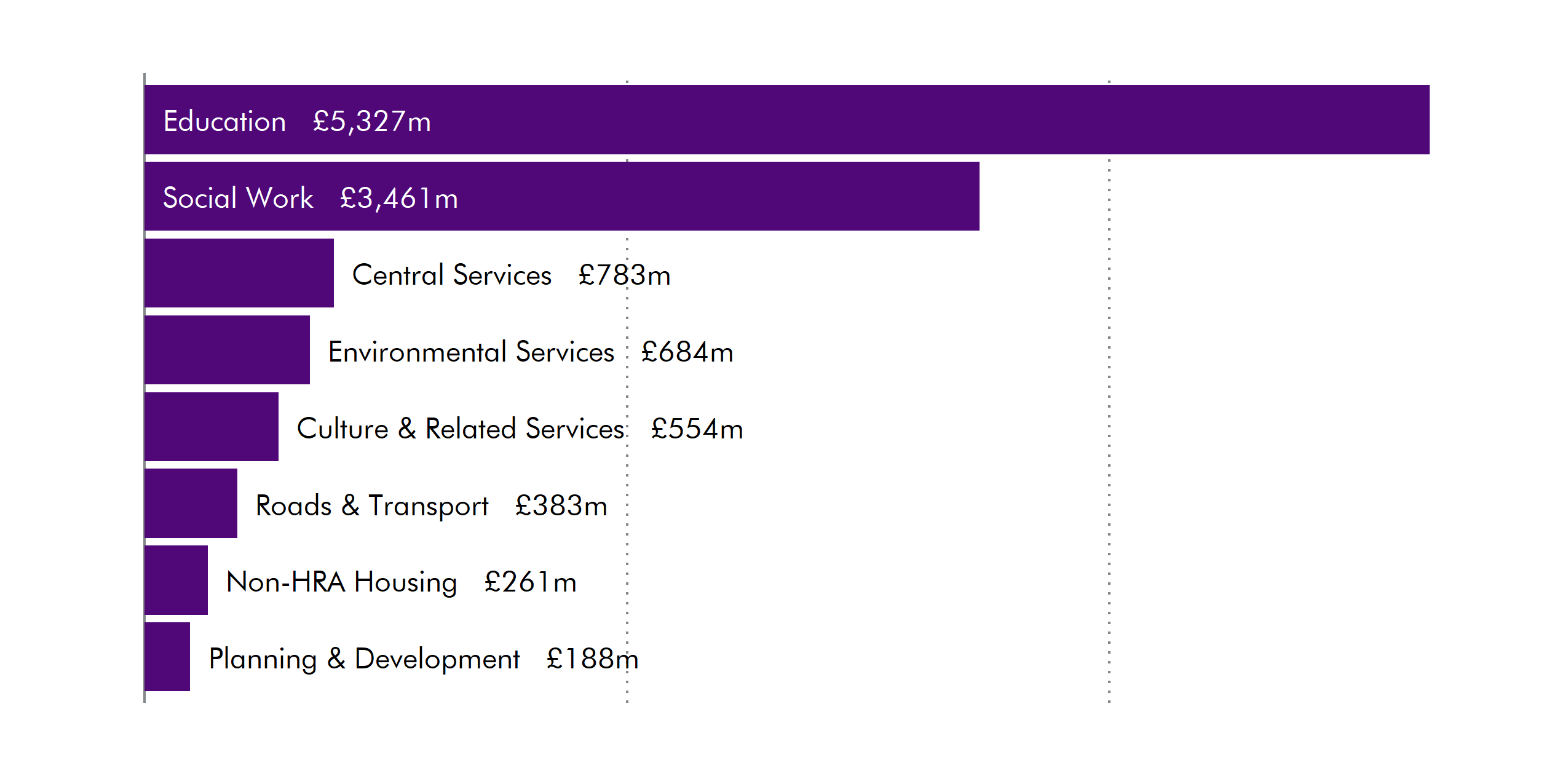

The vast majority of local government net revenue budget goes on school education and social work services.

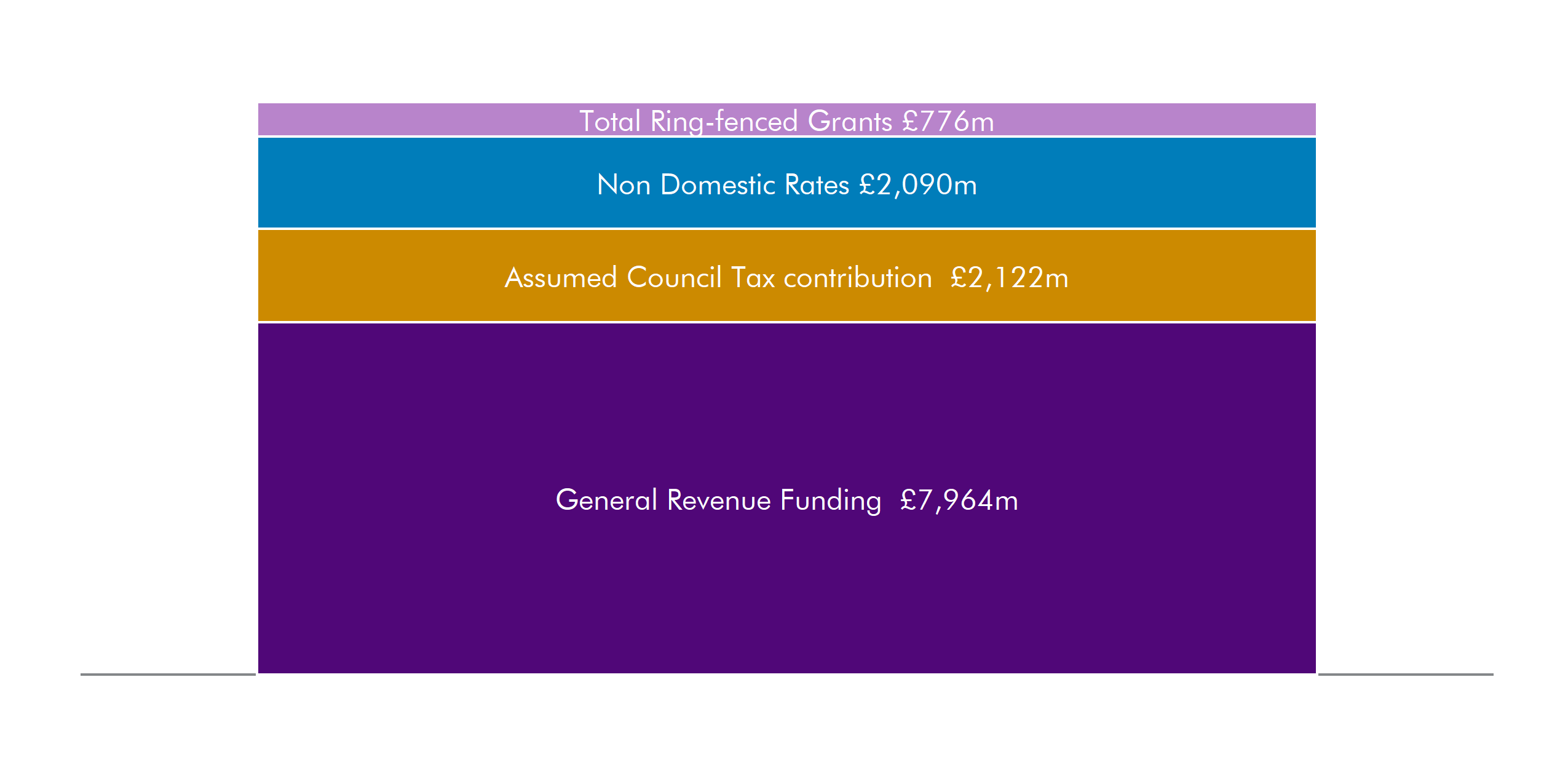

Local authorities receive 60% of their net revenue budget from the Scottish Government in the form of resource grants (both general and specific).

The Scottish Government also guarantees the anticipated Non-Domestic Rate income (NDRI) - the combined grant and NDRI income allocation to local government from the Scottish Government in 2021-22 is £11 billion.

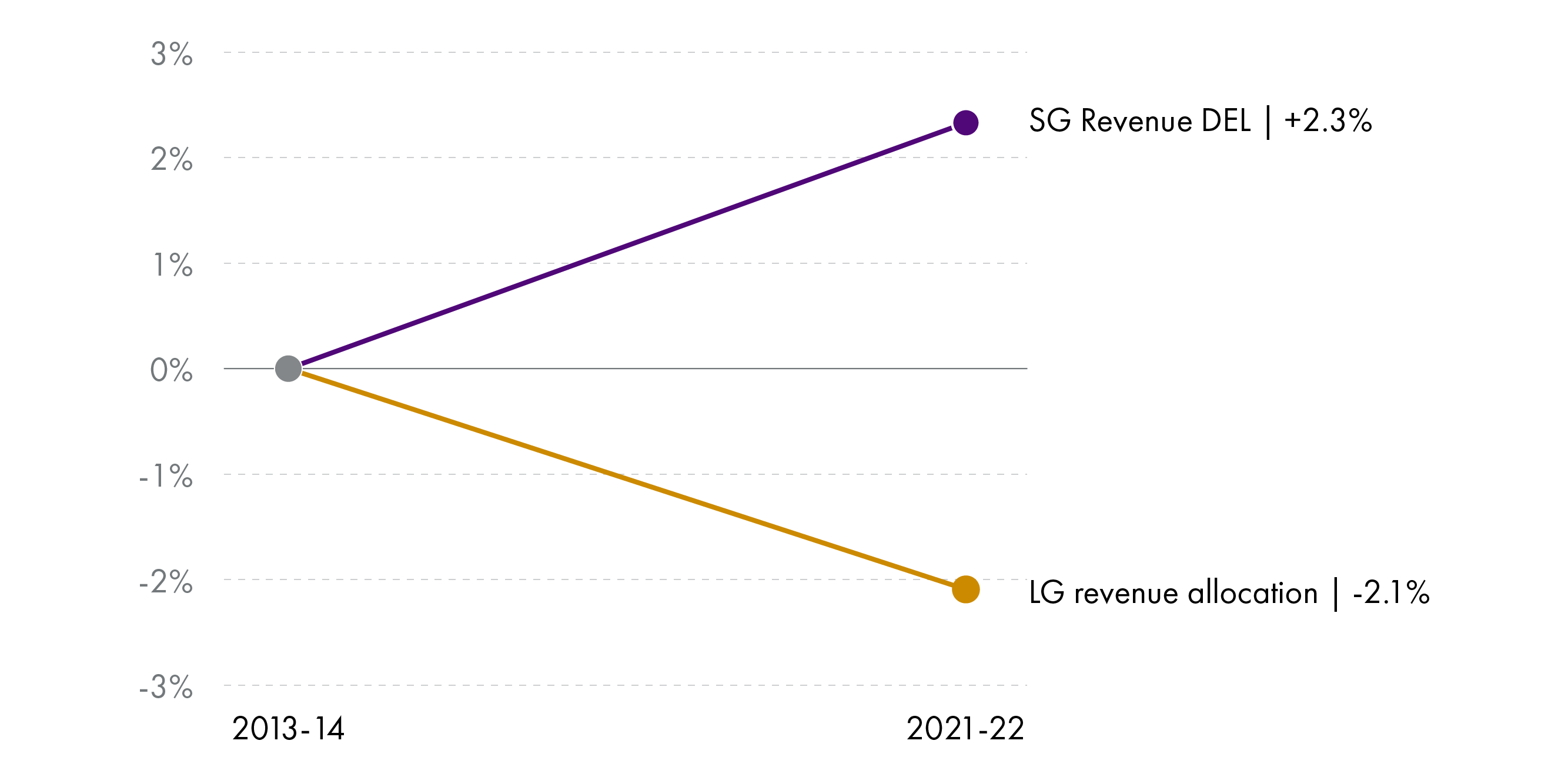

The total allocation represents a 2.1% reduction in real terms since 2013-14. Most of this reduction took place in 2016-17 and 2017-18.

The last two budget allocations have seen small real-terms increases.

Over the same period (2013-14 to 2021-22) the Scottish Government’s resource budget (not including NDRI) has increased by 2.3%.

The Government argues that all of this increase has been passed on to health.

Total resource allocation per head can vary significantly between local authority areas .

The level of capital funding can vary widely year-to-year depending on planned infrastructure investment.

Ring-fencing is an area of intense debate between the Scottish Government and local government.

Specific revenue (ring-fenced) grants as a proportion of overall revenue have increased substantially since 2013-14, mainly due to national commitments on early learning and childcare expansion.

Local government has been at the front line of Scotland’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

During 2020-21 the Scottish Government allocated an additional £2.5 billion of consequentials from the UK Government to the ‘Communities and Local Government’ budget.

Much of this was business support grants delivered directly to small businesses by local authorities. The remainder helped compensate councils for loss of income, as well as helping pay for changed service delivery and increased demand.

Local government spending and income – 2019-20 outturns

Based on the most recent audited accounts, Scotland’s local authorities spent £23.9 billion in 2019-201, the equivalent of 14% of Scotland’s total GDP2. There are various sources of income – grants from the Scottish Government, taxes, charges for services, rents, etc. However, the attention of Parliament is almost always on the grants and taxes elements. This is where most of the lively debate and intensive committee scrutiny is focussed each year.

Ignoring for the moment the services and fees element of local authority budgets, councils spent £11.1 billion of net revenue delivering a wide range of services in 2019-20, and a further £3.8 billion on the buildings and infrastructure needed to provide them (school buildings, new roads and paths, flood defences, vehicles, etc)1. The first sort of spend is called “revenue” or “resource”, much of it going on wages, contracts, supplies, etc. The second is known as “capital” and refers to spend on physical items which benefit service users over a number of years. For budget and accounting purposes, it is important to distinguish between the two.

School education receives by far the largest share of revenue spending by local government. On average, councils spend almost half their net revenue expenditure on education, £5.3 billion in total (80% of which goes on employee costs). Social work comes next - costing £3.5 billion in 2019-20 - with councils providing essential support to some of the most vulnerable people in society.

Together, education and social work accounted for 79% of local authorities’ net revenue expenditure in 2019-20.

Local authorities receive around 60% of their net revenue budget from the Scottish Government in the form of resource grants. The remainder, around 40%, comes from a combination of the nominally “local” Council Tax and Non-Domestic Rates (it’s worth noting that these proportions vary markedly across the range of 32 local authorities). In addition, the Scottish Government provides capital grants to each local authority, and individual councils can also borrow to help pay for large projects.

Services and fees income

Councils charge for a number of their services – licensing, planning, some environmental services, parking, rent, etc. This income is rarely considered by the Scottish Parliament and has not been mentioned during recent funding debates (a rare exception is the case of school music tuition charges). This income is directly linked to those council services being charged for. As the Scottish Government point out “it is treated separately and can only be used for the stated purpose”1. According to Audit Scotland, customer and client receipts amounted to 11% of total revenue income in 2019-20, 17% if housing-related income (rent) is included.

The 2021-22 budget and local government settlement process

For budget 2021-22, the road to final Local Government allocations was as follows:

UK Spending Review published in Nov 2020

SG Cabinet discusses and agrees portfolio distributions for next financial year

SG Budget published on 28 January 2021 (includes £11.6bn for LG)

Local Government Finance Circular 21/01with provisional allocations (1 Feb)

Publication of SPICe briefing on settlement and provisional allocations (5 Feb)

Budget Stage 1 debate in Scottish Parliament (25 February)

UKG Budget published with further details of Scotland’s block Grant (3 March)

Budget Stage 2by Scottish Parliament’s Finance and Constitution Committee

Budget Stage 3 debate in Scottish Parliament (9 March)

Amended Budget Bill approved by Scottish Parliament (9 March)

LG Finance Order agreed by SP (18 March)

LG Finance Circular 21/05 published with final allocations (18 March)

Negotiations on the annual local government finance settlement are conducted between the Scottish Government and COSLA, on behalf of all 32 local authorities ahead of the announcement of the Scottish Budget.

How the funding is allocated to local authorities

The Scottish Government estimates how much local government needs each year to deliver services and pay debts. This is known as Total Estimated Expenditure (TEE), and the decision is made by Scottish Ministers following consultation with COSLA on behalf of local authorities. For 2021-22 the Government estimated total expenditure to be £12.95 billion1.

Using a needs-based formula2, the Government then apportions a share of TEE to each of Scotland’s 32 local authorities. Once these initial allocations are calculated, the Scottish Government adjusts figures using a mechanism called the Main Funding Floor. This ensures that no local authority experiences particularly large variances in support from one year to the next3. The Government then estimates, and subsequently subtracts, anticipated Council Tax and Non-Domestic Rate income from these amounts, and the remaining sum is what councils receive as General Revenue Grant (GRG)4. A further funding floor is applied to ensure that no local authority receives less than 85 per cent of the Scottish per capita average (in 2021-22 this only impacted the City of Edinburgh).

Non-Domestic Rates and Council Tax

In theory, Non-Domestic Rates (NDR) are collected by individual councils and pooled by the Scottish Government, who then redistribute them to councils as part of the overall local government revenue settlement. In reality, this is an accounting exercise and local authorities do not actually transfer their NDR income (NDRI) to Government. Rather, an adjustment is made at the end of the year dependent on what each local authority has collected and what its share is of the “distributable amount” (defined as the amount of NDR distributed to councils on the basis of their share of the previous year's mid-year estimated income).

The Scottish Government guarantees the combined General Resource Grant (GRG) and distributable NDRI figure, approved by Parliament, to each local authority. If NDRI is lower than forecast, this is compensated for by an increase in GRG. This is exactly what happened in 2020-21 when COVID-19 measures dramatically reduced anticipated NDRI from £2.8bn in Finance Circular 21 to £1.9bn in Finance Circular 42, (and GRG increased by the same amount).

Council Tax is, by comparison, collected directly by local authorities and retained by them. The ratios between Council Tax bands are set out in legislation.

How much each local authority receives in the form of combined General Revenue Grant and NDRI isn’t known until the publication of the Scottish Government’s consultation Finance Circular, which for 2021-22 was on 1 February 2021. Given council budgets and their Council Tax rates need to be discussed and agreed by mid-March, for 2021-22 this didn't leave much time. The single-year nature of budget allocations is problematic for local government, as it makes long-term planning and multi-year spending decisions much more difficult to achieve. The Scottish Government accepts this and acknowledges that the current arrangement is far from ideal. Nevertheless, it argues:

“…as long as the UK Government continues to provide the Scottish Government with an annual resource budget settlement it will not be possible for the Scottish Government to set more than a single year budget and therefore a single year local government finance settlement”.

Scottish Government. (2021). Letter from Cabinet Secretary for Communities and Local Government to Convener of Local Government and Communities Committee. Retrieved from https://archive2021.parliament.scot/S5_Local_Gov/20210129ACtoCon.pdf

In a private correspondence with SPICe, Scottish Government officials confirmed that the Government "is committed to providing multi-year settlements as soon as it is possible"

Council Tax freeze

During her 2021-22 Budget announcement, Cabinet Secretary, Kate Forbes MSP, confirmed that subject to approval from local authorities, Council Tax would be frozen at 2020-21 levels. £90 million was made available to councils to compensate for this. This is roughly equivalent to how much additional income could be raised if Council Tax was increased by 3%. However, concerns were raised, for example by the Local Government Information Unit1, that council tax freezes tend to keep the tax base low “which means that when the freeze ends, higher percentage increases are needed to keep pace”.

Asked about this issue in February, the Cabinet Secretary for Finance informed the Local Government and Communities Committee: “I have heard the concerns that have been raised and, when we come to next year’s budget, we will take them on board". Indeed, during Stage 3 consideration of the Budget Bill, the Cabinet Secretary confirmed she would “provide certainty to local government for next year’s budget by baselining the £90 million that was provided this year to support a national council tax freeze”2.

The view from the Civic Centre – case study West Lothian Council

Many of our MSPs have previously served as councillors and will be fully aware of the budget-setting processes within their own local authorities. For those without this experience, the following gives an illustration of the process within one council, in this instance West Lothian Council (WLC).

WLC has high-level financial plans aligned with administrative periods, so its current financial planning period is for 2018-19 to 2022-23. The planning process included a stakeholder consultation in autumn 2017 followed by in-depth committee consideration over that winter. A five-year financial plan was then presented to the Council and agreed in February 2018. Each subsequent February, detailed revenue budgets are discussed and agreed by the Council for the remainder of the administrative period.

In a report for a full Council meeting on the 25 February 20211, WLC officials reminded councillors that a balanced budget must be approved before 11 March to comply with statutory obligations. This includes setting council tax for the following financial year.

Summarising the impact of Scottish Government’s allocation on West Lothian Council’s funding, officials stated:

The draft 2021/22 Scottish Government funding for West Lothian Council is £354.3 million, which is £12.1 million greater than the equivalent figure in 2020/21. It is important to note that within the provisional West Lothian allocation there is £3.9 million of funding which relates to new additional expenditure commitments for 2021/22 and £2.7 million which is conditional on a council tax freeze. Taking account of this, the council’s 2021/22 core funding from the Scottish Government for existing service delivery has increased by £5.458 million compared to 2020/21.

Despite a cash increase of 3.5% in revenue compared to last year, council officials argue that an expected increase in staff costs, growing demand for services and various other expenditure pressures in 2021-22 mean that the Council will actually face a £9 million funding gap. They therefore conclude “it is inevitable that there will be some changes to the services the council delivers.” Proposed savings come on top of over a decade of annual budget reductions, with officials stating: “the council has delivered total savings of £151.6 million since 2007/08”1.

Comparing and analysing local government allocation over time

SPICe is regularly asked to compare local government allocations over a number of years, for example going back to 2007 when the SNP first took office. However, the extent of changes made in April 2013, with police and fire services (and associated funding) being transferred from local authorities to new central organisations, means we strongly recommend using 2013-14 as the earliest base year for comparisons.

As revenue figures represent the funding available for the delivery of services, and capital figures can vary widely between years, there is a focus on revenue figures in the following section. Capital budgets are discussed separately in a later section.

Real terms changes between 2013-14 and 2019-20

“Real term” changes try to account for the impact of inflation on budgets when comparing over a number of years.

Using the methodology outlined in our 2018 briefing1, comparisons to 2019-20 are made using outturn figures (with 2013-14 as the baseline year). When exploring the historical trend in local government finance settlements, comparing outturn figures for one year to draft budget figures for the next can be problematic, mainly because further allocations are often made in-year. For the sake of providing an accurate comparison, outturn data is used for historic comparisons usually up to the previous financial year.

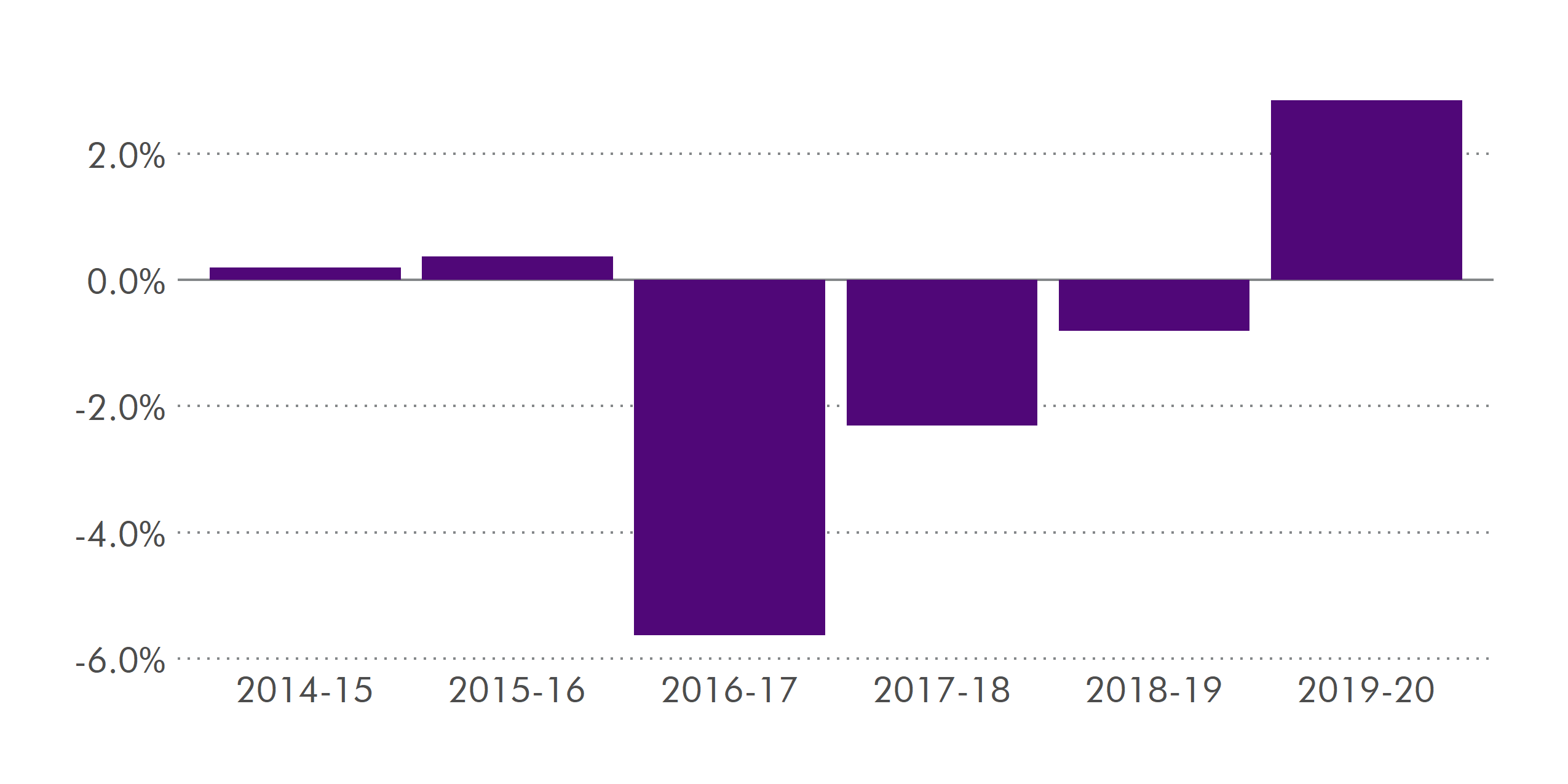

Between 2013-14 and 2019-20, local government’s revenue settlement decreased by 5.4% in real terms, or £591 million. The above chart shows that most of this took place in 2016-17, with further, albeit smaller, real terms reductions occurring in financial years 2017-18 and 2018-19. This trend was reversed somewhat in 2019-20 (and budget figures for 2020-21 and 2021-22 would suggest further real terms increases).

Comparison with Scottish Government budget

Over the past few years, one of the most reproduced of SPICe’s charts is a graph which compares local government revenue settlements to Scottish Government total revenue budgets since 2013-14. Figure 4 (below) updates this by showing the change in the local government revenue budget compared to the best comparable figure for the Scottish Government's revenue budget (Scottish Government departmental resource limit as set out in annual Budget documents).

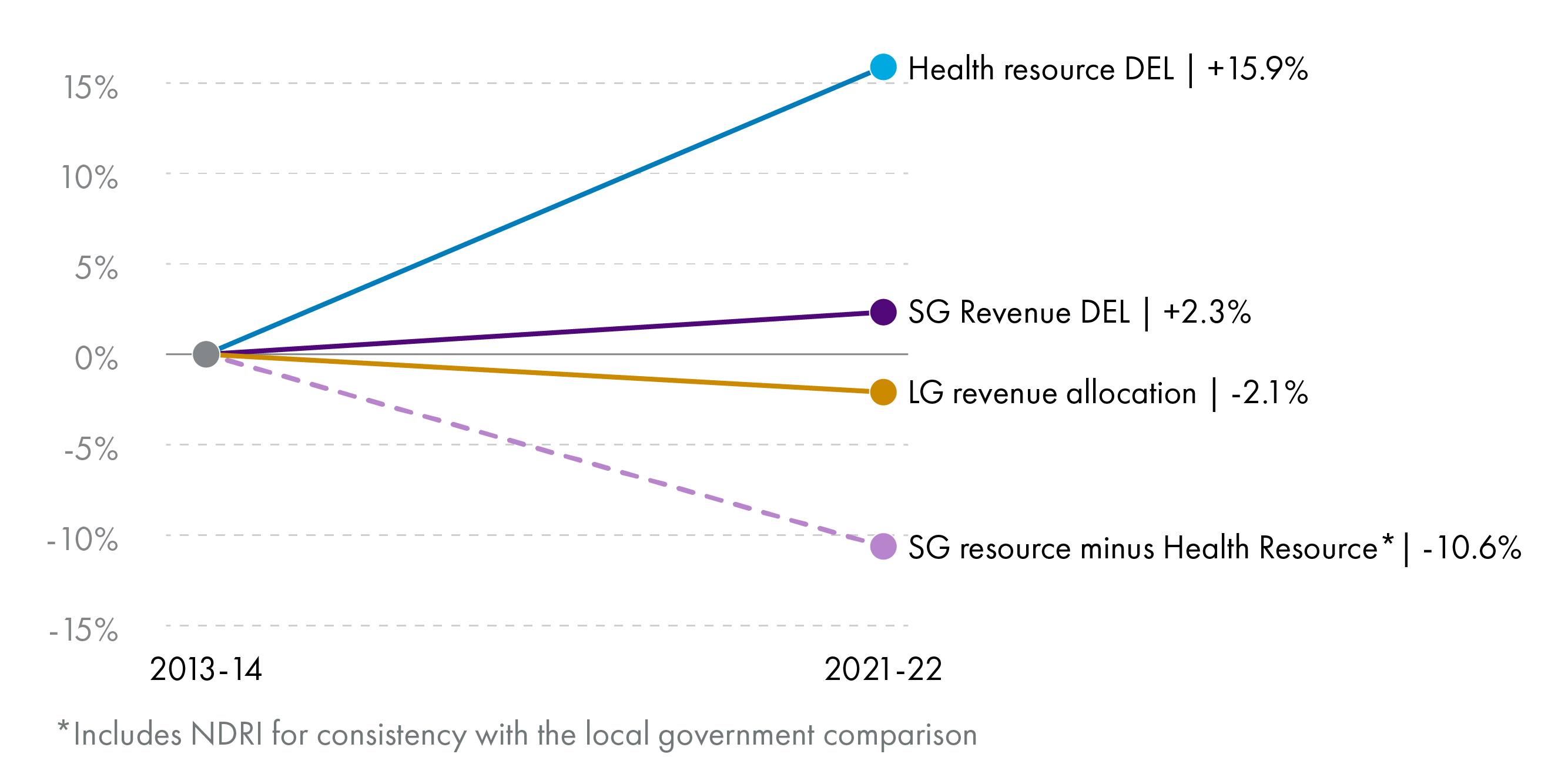

Figure 4 shows that total local government revenue allocation reduced by 2.1% in real terms (or -£236 million) from 2013-14 to 2021-22. Over the same period, the Scottish Government's fiscal resource budget limit from HM Treasury increased by 2.3%. If NDRI is added to the Scottish Government DEL figure, for comparison purposes, then the Scottish Government total also reduces in real terms, but by a much smaller amount (-0.1%) than the local government reduction. Either way, COSLA1, and a number of opposition parties2, argue that local government has not received fair settlements from the Scottish Government, especially when compared to the SG's settlements from the UK Government. This view is contested by Scottish ministers3.

Comparison with SG budget, minus health

During a Local Government and Communities Committee budget session earlier this year1, the Cabinet Secretary for Finance answered various questions on changes to the local government settlements by highlighting the increase in health spending:

In straight-up maths, we have protected the local government budget with the budget that we have, plus passing on health consequentials.

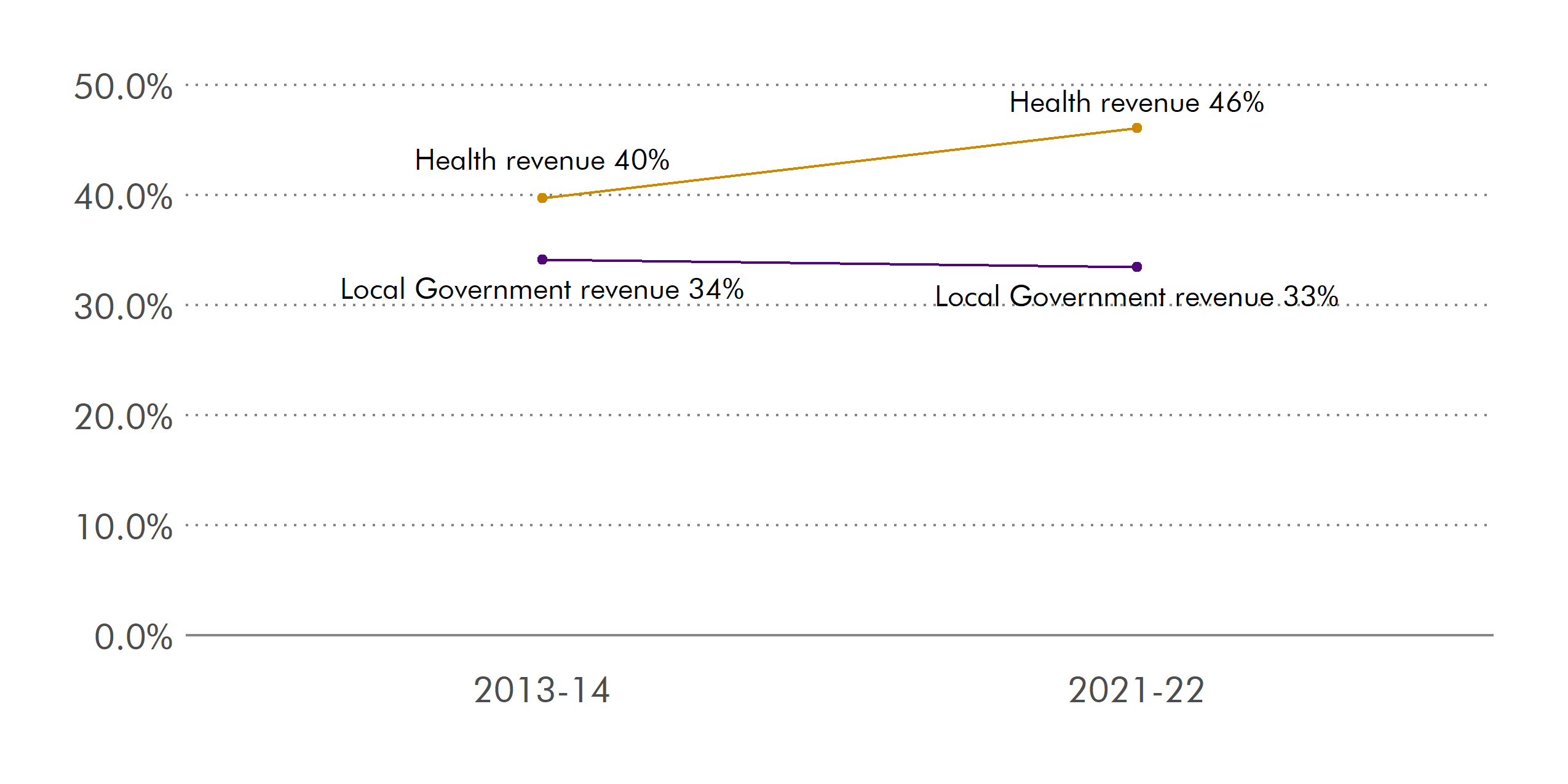

The health resource budget in 2021-22, excluding additional COVID funding, is £15.2bn. This is equal to 46.1% of the Scottish Government’s total DEL resource (plus NDRI) budget, up from 39.7% in 2013-14. The health resource budget increased by £2.1 billion, or 15.9%, in real terms over this period.

Figure 5 (above) shows that the Scottish Government’s non-health resource budget reduced by 10.6% in real terms between 2013-14 and 2021-22 (NDRI is included in the calculation for comparability purposes). So, the decision to increase spending on health by such a large amount has had clear consequences for all other areas of the Scottish Government budget, including on the second largest area of spend, local government.

COSLA’s view on this is that local authorities contribute significantly to the health and wellbeing of Scotland’s population, and they therefore call for a broadening of what is considered “health spending”. Furthermore, in their written submission to the Local Government and Communities Committee2, they argue that “despite this increase in [health] cash investment, national health outcomes have not improved”. In the subsequent evidence session, a Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy representative provided the following view:

“…we would call for an appreciation of the role that we [local government] play when considering the importance of improving health and wellbeing, for example. If we are to improve the health of the nation, local government will play an important part in that. It is about considering the consequentials for health that are received and asking whether they could be used more widely.”

Scottish Parliament Official Report. (2021). Local Government and Communities Committee 10 February 2021. Retrieved from http://archive2021.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=13120

LG settlement as percentage of SG budget

Just as health’s share has increased, so the local government settlement as a share of total Scottish Government revenue budget has reduced. The following chart shows that the local government revenue settlement as a proportion of total Scottish Government resource DEL (plus NDRI) has decreased from 34.1% to 33.5% in 2021-22.

Local government settlement per head by local authority

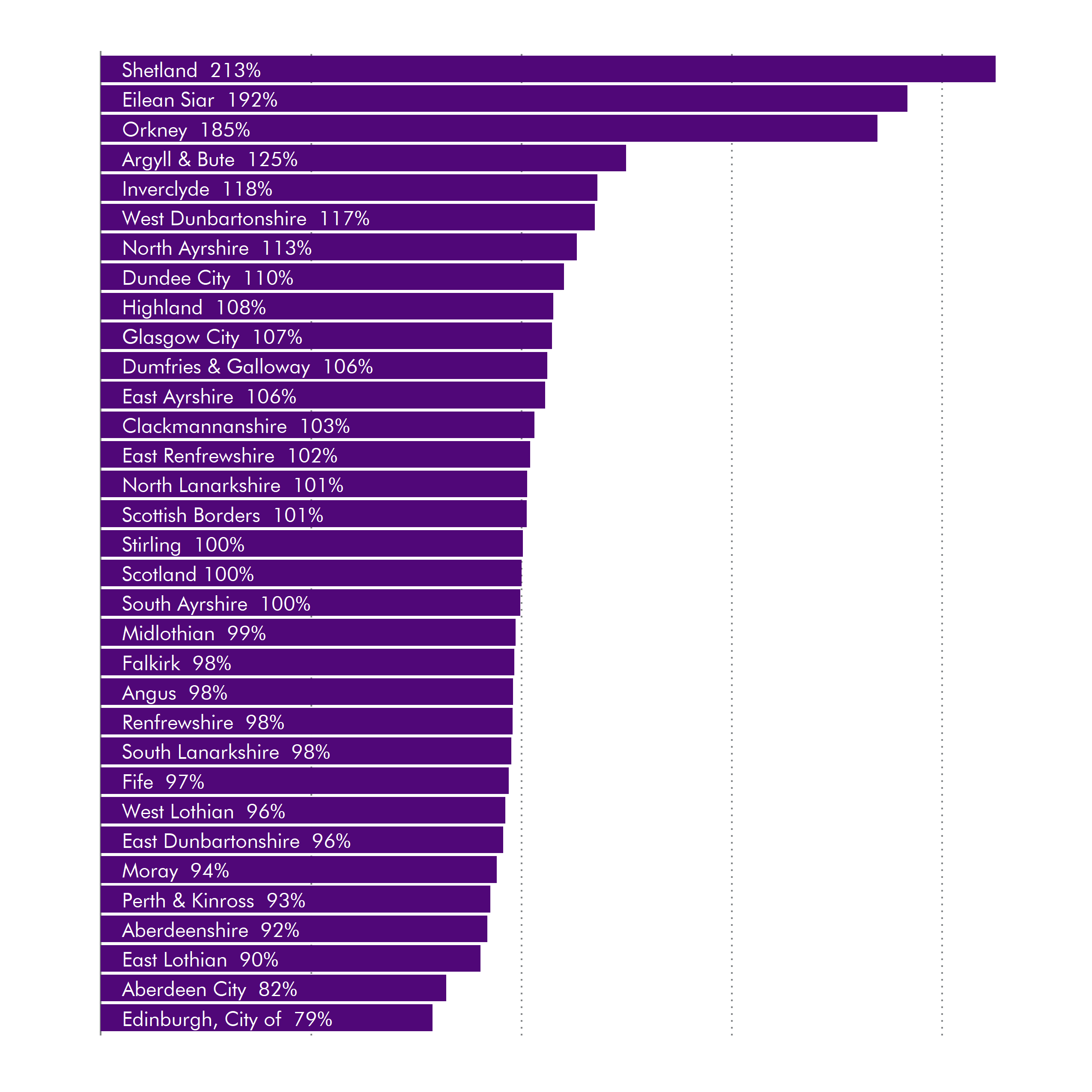

As would be expected in a country as geographically and socially diverse as Scotland, different local authorities require different levels of funding. Indeed, the needs-based formula used to allocate funding aims to take into account variations in the demands for services and the costs of providing them to a similar standard.

Figure 7 shows total 2021-22 revenue allocation (GRG+NDRI) per head of population by local authority area, as a percentage of the Scottish average, with Scotland being 100%. Island local authorities clearly have the highest allocations per head, whilst the cities Edinburgh and Aberdeen have the lowest. The latter two have higher levels of anticipated Council Tax income than the national average; council tax receipts in these local cities are expected to represent 22% and 20% of total estimated expenditure in 2021-22, as compared to 16% nationally, and under 10% in Orkney, Eilean Siar and Shetland.

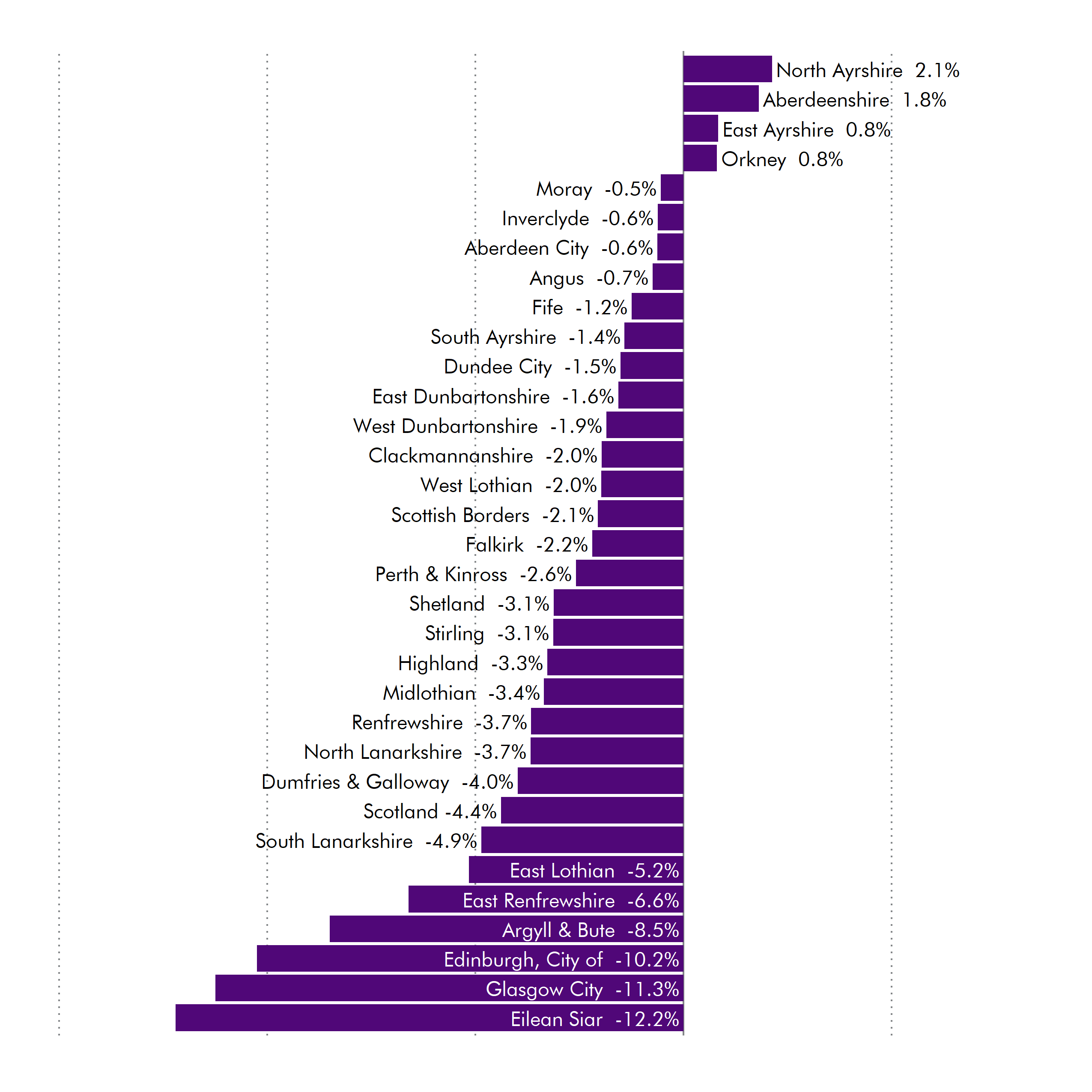

It is possible to compare funding per head for each local authority area over time. The SPICe Briefing Local Government Finance: Budget 2021-22 and Provisional Allocations to Local Authorities1 explores the cash difference between 2020-21 and 2021-22 Budget figures, but not the longer term trends. In order to compare like-for-like figures for 2013-14 and 2021-22, the numbers used (Figure 8, below) are final Local Government Finance Circulars settlements, i.e. they are budget figures, not outturns. Population estimates used in the 2021-22 calculations are those most recently published by the National Records of Scotland and are for mid-2020.

Almost every local authority has seen real term reductions in per head revenue allocations since 2013-14, the exceptions being North Ayrshire, Aberdeenshire, East Ayrshire and Orkney.

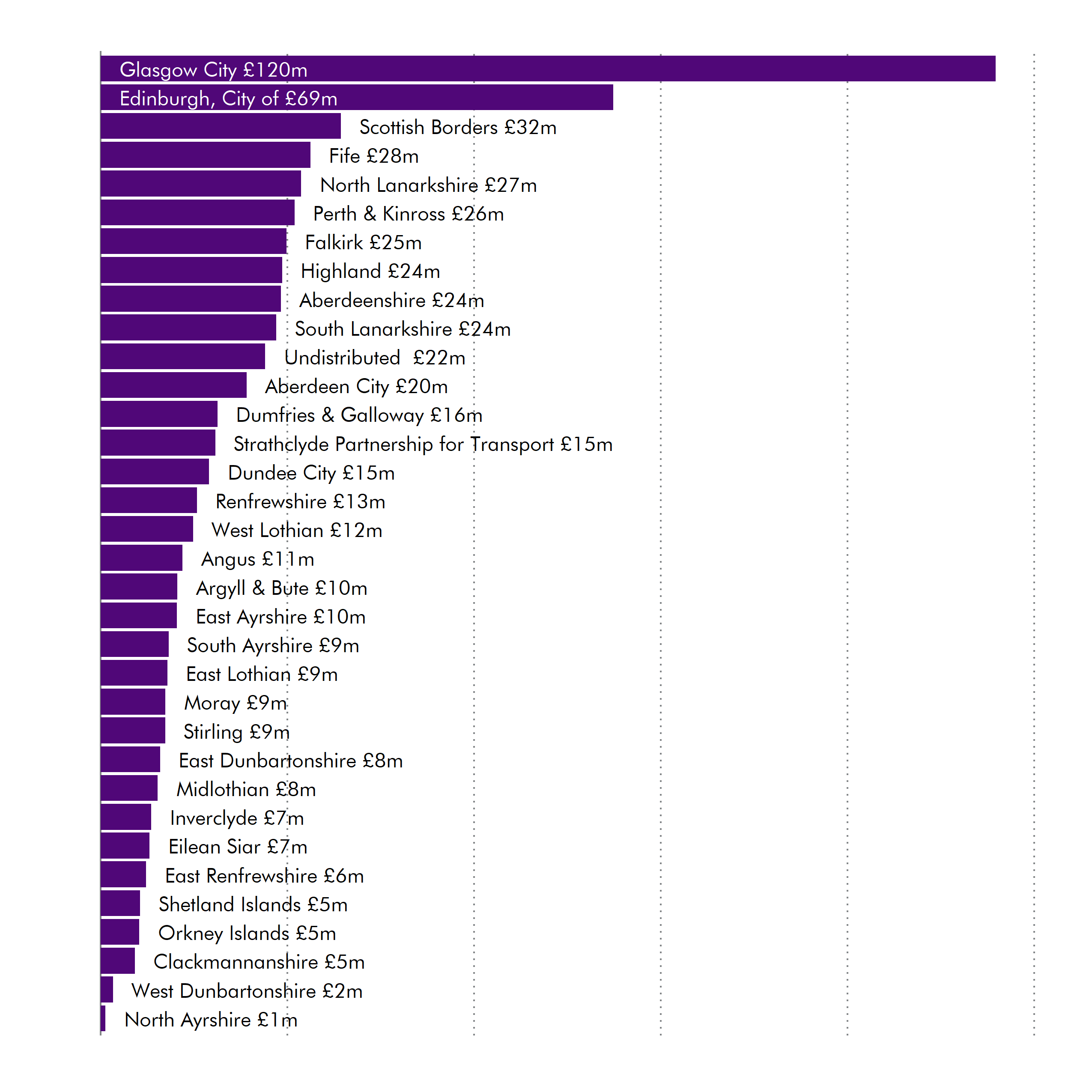

Capital allocations

Like revenue allocations, capital grants from the Scottish Government take the form of general and specific (ring-fenced) grants. However, unlike revenue allocations, the level of capital funding can vary widely year-to-year depending on planned infrastructure investment (see Exhibit 12 in the most recent Accounts Commission local government overview1). For example, total capital funding reduced substantially in both 2020-21 and 2021-22. However, this comes after steady increases in capital allocations each year between 2016-17 and 2019-20. Explaining the 55% reduction in Specific Capital Grants this year, the Scottish Government states “this reflects the removal of the Early Learning and Childcare funding and the one-off funding for the Heat Networks Early Adopters Challenge Fund”2. Figure 9 shows total capital allocation by local authority in 2021-22, with Edinburgh and Glasgow clearly receiving the largest settlements.

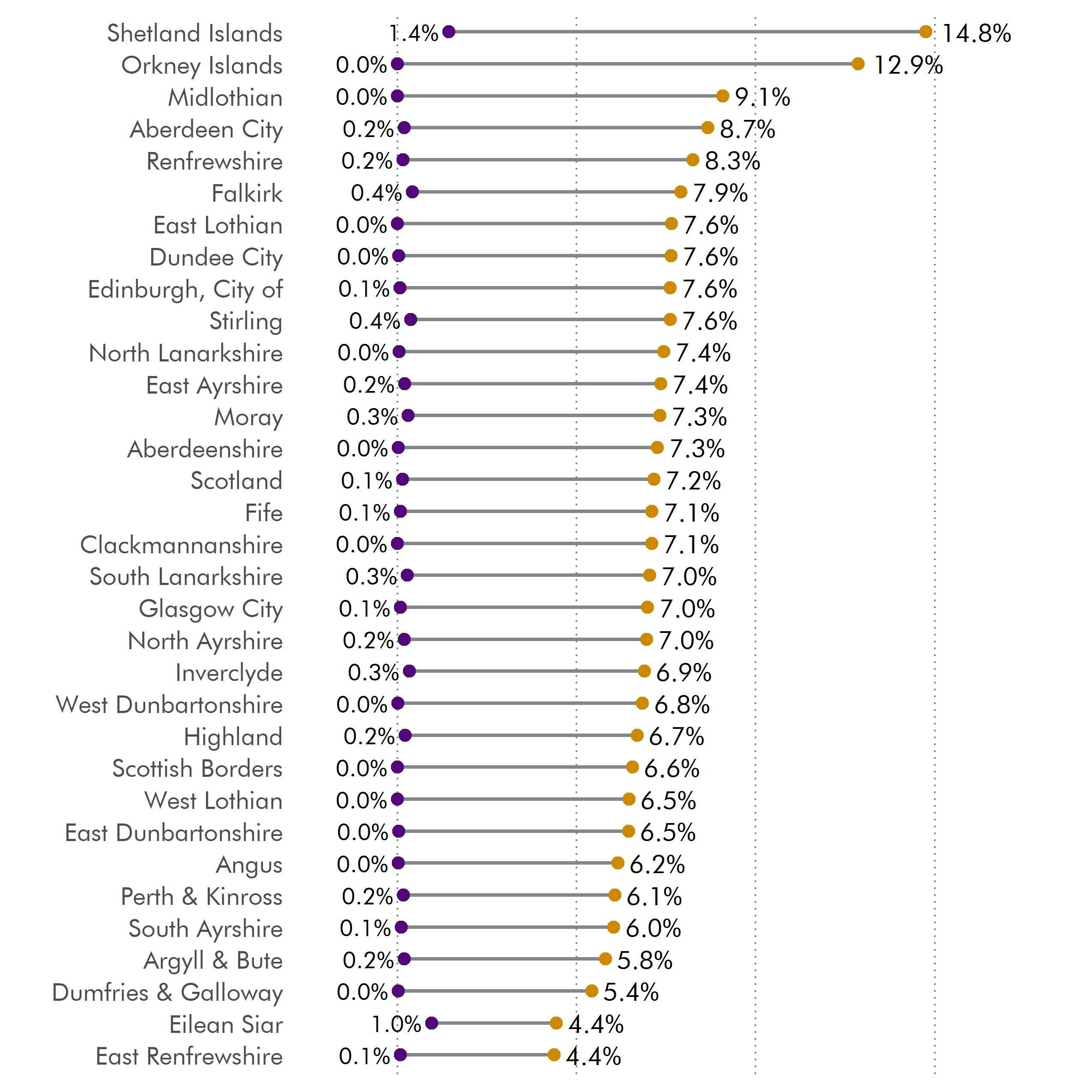

Specific Revenue Grants or ring-fenced funds

In its Public Finance Manual (published 2018), the Scottish Government states there is a “general presumption against the establishment of additional hypothecated allocations within the local government settlement”1. However, Figure 10 shows a significant increase in ring-fencing across all local authorities between 2013-14 and 2021-22. In 2013-14 ring-fenced grants represented 0.1% of total revenue allocation to local authorities. The 2021-22 allocation shows that across Scotland over 7% of total revenue allocation is now ring-fenced, with some local authorities such as Shetland Islands and Orkney Islands having 15% and 13% of their revenue allocations ring-fenced.

Some Members will recall the “historic Concordat” of 2007 between the Scottish Government and COSLA when over 40 previously ring-fenced funds were rolled-up and transferred into the general local government settlement. At the time, the Scottish Government informed Parliament:

Scotland's local authorities are key partners and that is why this Government will reduce ring fencing, enabling councils to allocate resources according to local priorities; allow local authorities to retain for the first time the full amount of their efficiency savings to redeploy to other pressures; recognise the democratic legitimacy of local government and devolve authority to it to make decisions that reflect local needs...

Scottish Parliament Official Report. (2007, November 14). Statement by John Swinney MSP on the Strategic Spending Review. Retrieved from http://archive2021.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=4753&i=39195

The Concordat also highlighted a relaxation of bureaucracy, with “a reduction in monitoring and reporting not directly linked to ring fenced funding” being agreed. In its place, a new outcomes-based approach was introduced, with local authorities required to publish annual reports documenting progress made towards the national outcomes detailed in the National Performance Framework. Summarising views from a range of local authorities, the Local Governance Review recently stated that “shared outcomes should be seen as the mechanism for delivering local and national aspirations, not ring-fenced funding”3.

Ring-fencing in a nutshell

When the Scottish Government allocates funding to local authorities which can only be used for a specific purpose this is known as “ring-fencing”.

The advantages for the Scottish Government are clear; it can set national priorities, introduce new initiatives which are then delivered by local authorities, and the money announced is allocated for that purpose, and that purpose alone1. Ring-fenced funds, as the term is used in the Scottish Government’s Finance Circulars, includes funding for Gaelic education, Pupil Equity, Criminal Justice Social Work, Early Learning and Childcare Expansions and Ferries.

From a local government perspective there are a number of disadvantages, including the fear that ring-fencing erodes local autonomy and local initiative. Increased central control over budgets means local government is effectively a delivery agent for the Scottish Government on those specific priorities. There are also monitoring and reporting requirements related to ring-fencing which can pose significant challenges to council staff.

Ring-fencing is one of the more controversial areas of local government finance, and not just in Scotland. Evaluating the health of local government across Europe between 2010 and 2016, the Council of Europe’s Congress of Local and Regional Authorities identified a tendency towards stricter national control over local finances and insufficient financial autonomy at the local level across the continent2.

Ring-fenced and protected budgets

SPICe uses Local Government Finance Circulars as its main source of financial information. Therefore, we analyse the allocation of “ring-fenced grants” or “specific revenue grants” (terms used interchangeably by the Scottish Government) within these documents. In 2021-22, 7.2% (£779 million) of total revenue allocation has been ring-fenced (with £546 million of this being for early learning and childcare expansion). The Scottish Government defines ring-fenced grants as the specific grants listed in their Budget document and Finance Circulars. Their allocation and distribution are set centrally, with funds linked to specific policy initiatives and expectations.

Alongside these specific revenue grants, the Accounts Commission has identified several of Scottish Government’s policy initiatives delivered by local government which have funding attached to them: “although these are not explicitly ring-fenced, if the council does not meet the objectives it may lose out on the funding”1.

COSLA uses a broader definition of ring-fenced or “protected” funding, arguing that in addition to Specific Revenue Grants, there are large areas of local government funding which are in reality “protected" through obligations created by current and past Scottish Government policy initiatives. In a letter to the Local Government and Communities Committee, COSLA argue that 60% of their 2019-20 allocation is protected2. COSLA illustrates this using the example of spending on school teachers:

Local authorities must work within pupil:teacher ratios set nationally, as well as a national commitment to maintain teacher numbers. A commitment to maintain a certain number of teachers means that Councils must budget for the salary, pensions and other costs associated with those teachers. Although this funding is not explicitly ring-fenced, there is no choice but to make budget provision and so there is hidden ring-fencing. Costs associated with teachers alone makes up around 21% of the funding which Councils receive from the Scottish Government.

Similar obligations apply to some social services. And as mentioned earlier in this briefing, combined education and social service spend comprises 79% of local government resource spending. As such, local authorities argue there is little flexibility around how they spend the vast bulk of their budgets on local priorities.

The debate continues…

This is certainly not a new debate. Writing almost twenty years ago, COSLA argued:

...too many decisions which have direct consequences for local spending are made at national level and the central government gives too many directions about how things should be done… Central direction means central government telling councils where to spend, whether spend in that area is needed locally or not.

Convention of Scottish Local Authorities. (2001, November 6). COSLA submission to Local Government Finance Inquiry of the Local Government Committee. Retrieved from http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/business/committees/historic/x-lg/papers-01/lgp01-28.pdf

Given the Scottish Government’s commitment to introduce a Local Democracy Bill, which will likely build on the Local Governance Review, the issue of Scottish Government ring-fencing versus fiscal empowerment at the local level will continue to be discussed throughout this current Parliamentary session.

The impact of COVID-19 on local government finance

As with all areas of society, COVID-19 has had a severe impact on local government finance. From increased demand for certain services and reduced income from fees and charges, to a massive drop in Non-Domestic Rates income, the last 18 months have seen unprecedented pressures on council budgets. COSLA estimated the financial cost of Covid-19 on councils in 2020/21 alone was £767 million, with around half of this coming from lost income and the rest resulting from increased costs related to demand and service delivery1. This is discussed in some detail by the Accounts Commission in its most recent Local Government financial overview2.

Additional funding in response to COVID pressures

Over the course of 2020-21, the Scottish Government received a total of £9.7 billion in Barnett consequentials from the UK Government (see SPICe Spotlight blog post). Obviously, much of this was passed on to the NHS to help deal with the pandemic. However, recognising the pressures facing local government and local businesses, the Scottish Government allocated £2.5 billion of consequentials to the ‘Communities and Local Government’ budget, with around £1.3 billion of this being passed on to businesses through various grant schemes (although routed through councils).

Local Government Finance Circular 5/21 (see Annex G)3 shows how the remaining £1.25 billion COVID consequentials were allocated to local authorities during 2020-21. For example, £200 million was distributed to local authorities as a result of the UK Government’s local government income compensation scheme (for lost sales, fees and charges as a result of COVID-19) and £70 million was distributed as additional education recovery funding.

In her Budget statement to Parliament, the Cabinet Secretary announced an additional £259 million of non-recurring COVID consequentials for 2021-224. Although welcoming the flexibility around this extra funding - with councils having discretion over how the money can be used - COSLA nevertheless estimate that the allocation is £500m less than what councils actually need1. Joint-authored research by the Scottish Government and COSLA looking at the likely impact of COVID-19 on life and wellbeing in Scotland, found that “the key medium term impacts are likely to be seen on health, economy, fair work and business, education and poverty outcomes”6. This document gives an indication of the challenges local authorities will likely face over the next few years.

Reduction of Non-Domestic Rates income

With emergency 100% rates relief for retail, hospitality and leisure properties introduced in March 2020, anticipated Non-Domestic Rates income reduced dramatically for 2020-21. The Scottish Government announced in February that reliefs would be extended, meaning retail, hospitality, leisure and aviation businesses would pay no Non-Domestic Rates in 2021-227.

As discussed above, the Scottish Government guarantees the equivalent of combined General Revenue Grant (GRG) and Non-Domestic Rates income each year to every council; so, the reduction in the latter means a corresponding increase in the GRG. The Scottish Government was able to do this through utilising Barnett consequentials from the UK Government.