Marine and Fisheries: Subject Profile

This briefing is written for the benefit of both new MSPs and those returning to the Parliament. It provides an overview of the main issues related to marine and fisheries. It highlights the main legislation and policy developments in previous parliamentary sessions, and potential future developments. More detailed briefings on related topics will be produced throughout the parliamentary session.

Key points

Scotland's sea area is vast, making up 62% (462,263 km2 ) of the UK's waters and 8% (19,000 km) of Europe's coastline. There are huge challenges in balancing competing demands on Scotland's marine resources while protecting Scotland's diverse marine environment

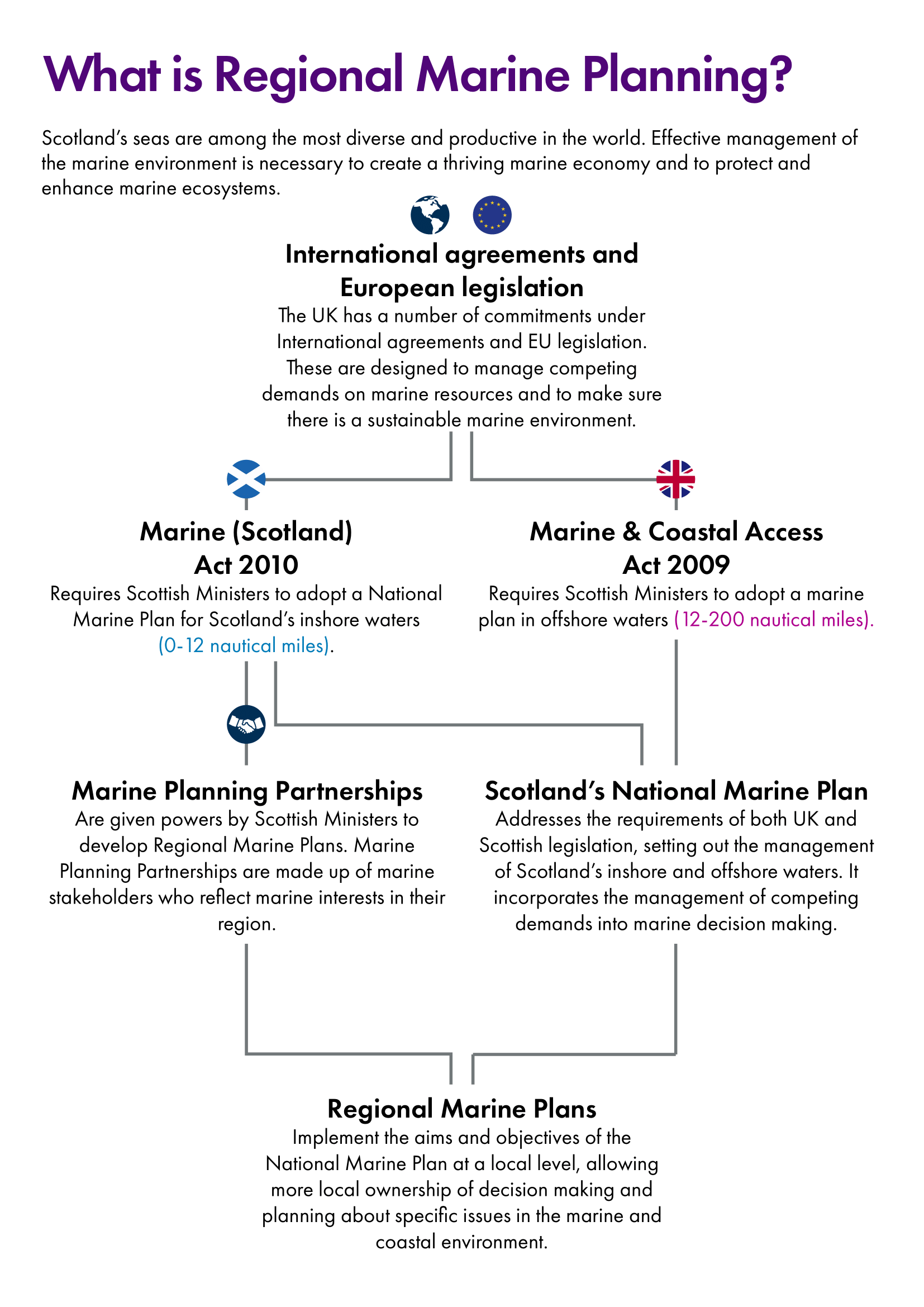

Marine planning in Scotland’s inshore waters (out to 12 nautical miles) and offshore waters (12 to 200 nautical miles) is governed by the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010, an Act of the Scottish Parliament and by the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009, an Act of the UK Parliament.

Under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010, Scottish Ministers are required to prepare an assessment of the condition of the Scottish marine area to inform the National Marine Plan. Assessments are also required for a given Scottish Marine Region when developing Regional Marine Plans.

Scotland’s National Marine Plan (NMP) was published in March 2015. The purpose of the NMP is to set out strategic policies for the sustainable development of Scotland's marine resources out to 200 nautical miles. It also provides a strategic framework for marine licensing decisions.

The Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 also allows for the development of Regional Marine Plans. Regional Marine Plans are intended to provide local ownership of marine planning decisions and to implement the aims and objectives of the National Marine Plan, taking into account local ecosystems and socio-economic circumstances

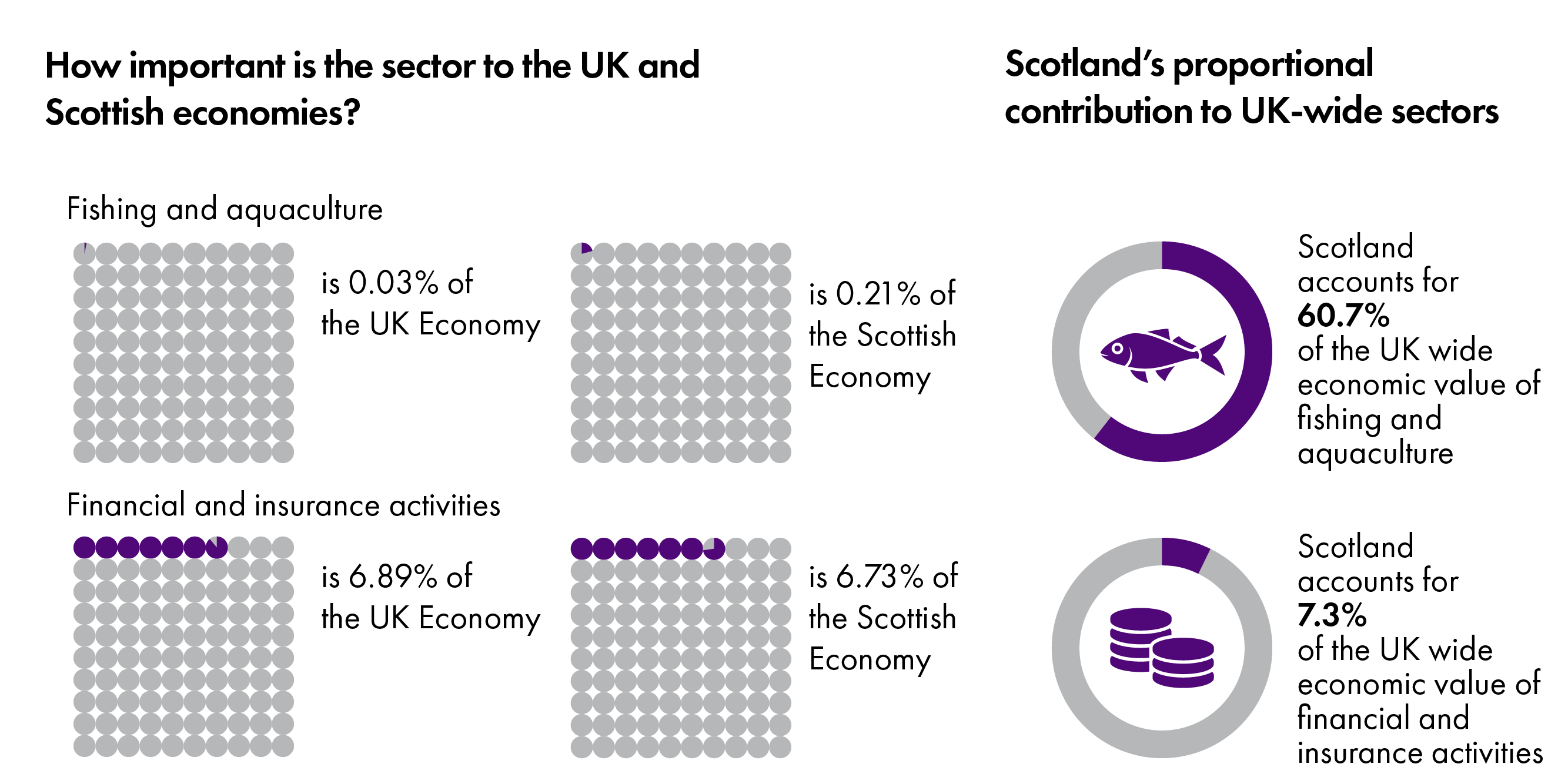

Whilst at a national level, fishing makes a small contribution to GDP, it is very important both economically and socially at a local and regional level. The majority of sea fishing in the UK takes place in Scottish waters and by Scottish vessels.

Fishing is an ancient and historic industry that is central to the cultural identity of many coastal communities, particularly those in remote regions and the islands of Scotland.

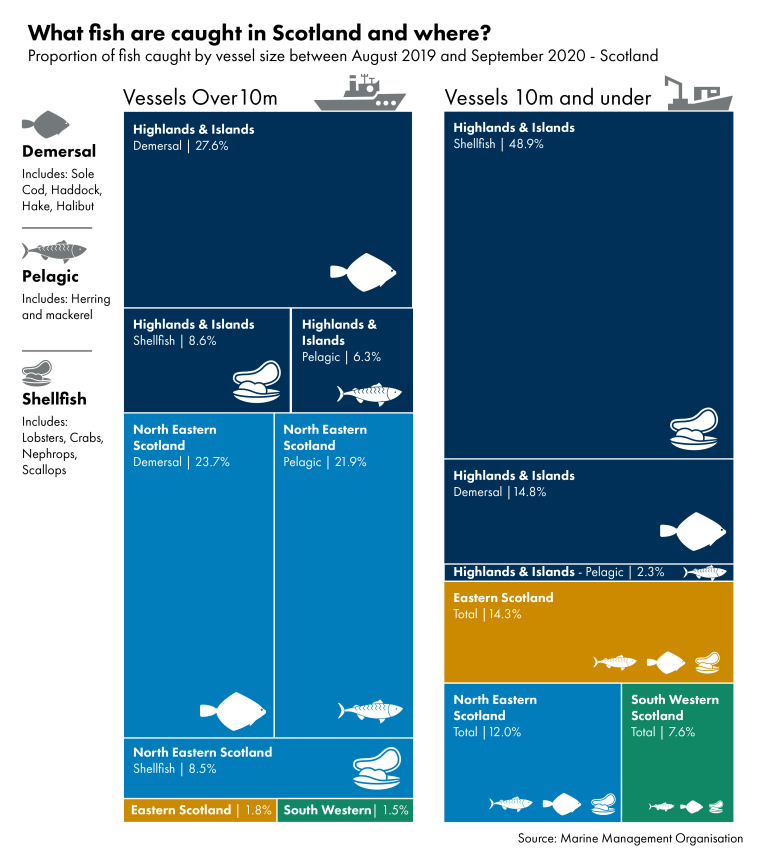

Scotland’s fisheries are diverse. Targeted species and fishing methods vary considerably in different regions of Scotland’s waters. Fishing activity in the North Sea contributes the most in terms of total weight and value. This is focussed mainly on pelagic (mid-water) and demersal (bottom feeding) species. Fishing on the west coast is mostly carried out by smaller inshore vessels, which make up the majority of the Scottish fleet in total number. These vessels primarily target shellfish such as lobster, crabs, nephrops (langoustine) and scallops.

Most aspects of fisheries management are not reserved (i.e. devolved). Marine Scotland, a directorate within the Scottish Government, is responsible for managing the activities of all fishing vessels operating within the ‘Scottish Zone’, as well as all Scottish vessels operating beyond the Scottish Zone.

Now that the UK has left the European Union, the UK is an independent coastal state, meaning it has control over fisheries management and governance in UK waters. The UK Fisheries Act 2020 provides the legal framework for the UK to operate as an independent coastal state.

Effective fisheries management is key to addressing the contribution of commercial fishing to the climate and ecological crisis and improving economic resilience to its impacts.

Fisheries management in the UK (and Scotland) is subject to various international treaties, agreements and obligations with regard to the management of fish stocks shared with neighbouring fisheries actors (primarily the EU, Norway, Iceland and the Faroe Islands).

The new EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) took effect on 1 January 2021. The fisheries agreement within the TCA sets out new arrangements on access to waters, access to markets for seafood and the joint management of shared fish stocks between the UK and the EU.

Scottish Ministers are responsible for the regulation of inshore fishing around Scotland. Regional Inshore Fisheries Groups (IFGs) allow local fishers to play a role in inshore fisheries management and wider marine planning developments.

Freshwater fishing in Scotland is almost entirely a recreational activity, with the exception of a limited number of estuarine and in-river net fishers using traditional techniques. Freshwater fishing rights are private and the owners of these rights largely control access to fisheries. Scottish Ministers are responsible for the stewardship of all freshwater fish resources in Scotland.

Wild salmon have been experiencing decline over a number of decades due to various natural and human-caused pressures. The North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organisation (NASCO) is international organisation that aims to conserve, restore, enhance and rationally manage Atlantic salmon through international cooperation taking account of the best available scientific information. Scotland, as part of the UK, has obligations to, and contributes to, the work of NASCO.

Statutory obligations under the Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Regulations 2016 require an assessment of the conservation status of salmon to be carried out for all inland waters on an annual basis.

Aquaculture is a rapidly growing industry in Scotland. This is focussed around finfish (primarily farmed salmon), shellfish and seaweed. Scotland is one of the top three producers of farmed Atlantic salmon globally. However, there has been growing concern over the environmental impacts of aquaculture.

Rights to the seabed out to 12 nautical miles are managed by the Scottish Crown Estate. The Scottish Crown Estate Act 2016 devolved powers over the revenue management of Scottish Crown Estate Assets to Scottish Ministers.

In its Programme for Government 2020-21, the Scottish Government committed to developing a 'Blue Economy Action Plan' to "strengthen the resilience of our marine industries ranging from renewable energy to fisheries [...] and to support coastal communities, recognising the vital importance to our marine economy of the abundant natural capital in Scotland's seas and rivers".

Scotland's seas and boundaries

Scotland’s sea area is vast, making up 62% (462,263 km2) of the UK's waters and 8% (19,000 km) of Europe’s coastline. There are huge challenges in balancing competing demands on Scotland's marine resources while protecting Scotland's diverse marine environment.

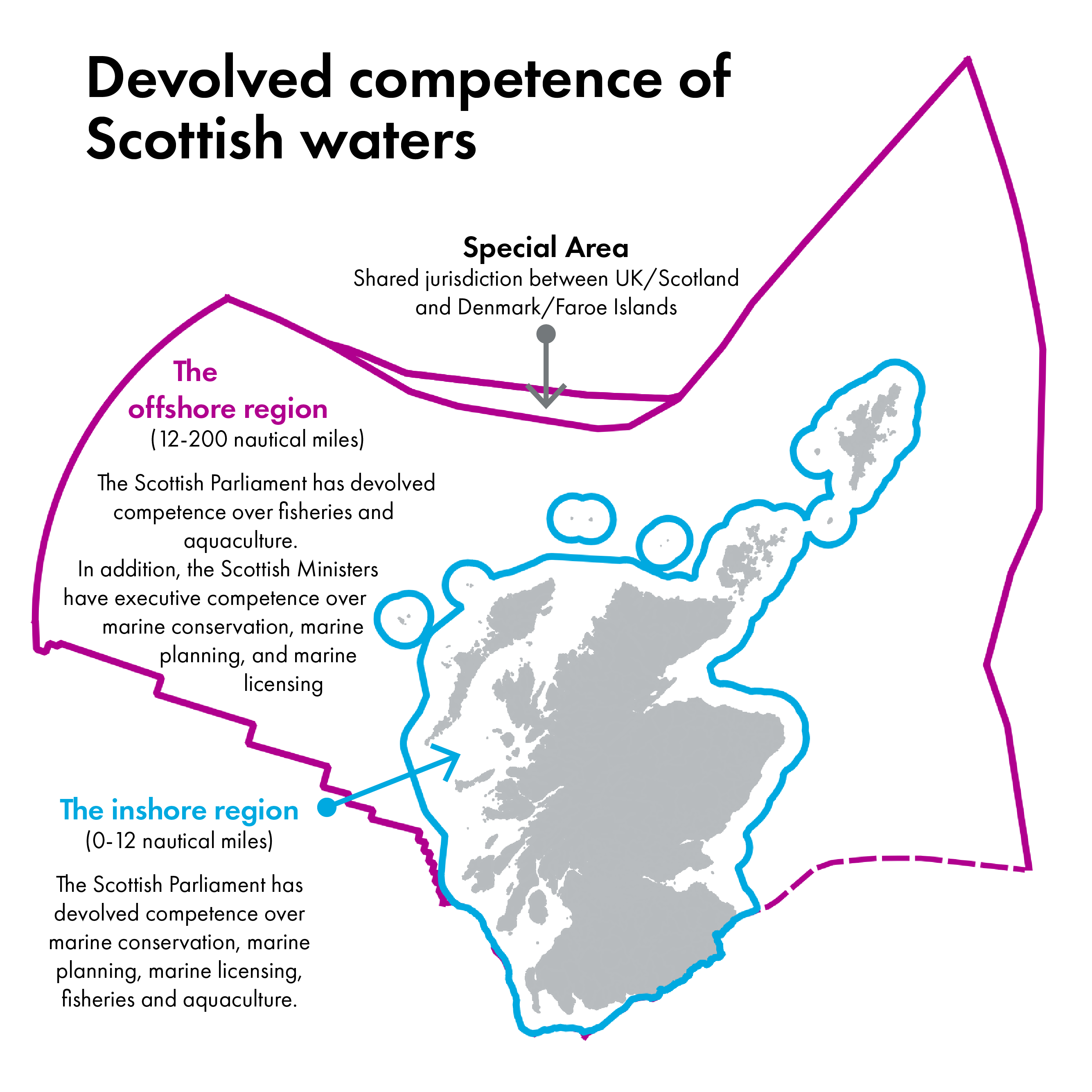

Scotland’s seas and boundaries are shown in the map below. Responsibility for the governance and management of Scottish waters is complex and involves a mixture of devolved and reserved competence. Different areas of the seas are governed by different regulations with regards to the management of commercial fishing and fishing access rights.

6 nautical miles - UK vessels have exclusive rights to fish within six nautical miles of territorial baselines.

Up to 12 nautical miles – Scottish Territorial Seas Boundary, also known as inshore waters.

12-200 nautical miles – Scottish Fisheries Limits and subject to access requirements provided by the UK Fisheries Act 2020.

The Marine Acts

Marine planning in Scotland’s inshore waters (out to 12 nautical miles) and offshore waters (12 to 200 nautical miles) is governed by the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010, an Act of the Scottish Parliament and by the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009, an Act of the UK Parliament, respectively. The two Acts (referred to as the Marine Acts) establish a legislative framework for marine planning to enable demands on marine resources to be managed in a sustainable way across all of Scotland’s seas.

Marine Assessments

Under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010, Scottish Ministers are required to prepare an assessment of the condition of the Scottish marine area to inform the National Marine Plan, or Scottish Marine Region to inform Regional Marine Plans (See following sections).

These peer-reviewed assessments are carried out by a partnership of academic research institutes and public bodies and provide an evidence base on the state of Scotland’s seas and of the main activities and pressures on Scotland's marine environment. They are required prior to the development and review of the National Marine Plan and Regional Marine Plans.

The Scottish Government published the first marine assessment - known as 'Scotland's Marine Atlas' in 2011. The most recent Scottish Marine Assessment was published in December 2020.

Key findings of the Scottish Marine Assessment 2020 include:

Progress is being made in relation to contaminants.

There are increasing pressures associated with non-indigenous species.

Many marine industries such as offshore wind and marine energy (wave and tidal) are of growing importance to the Scottish economy.

Climate change is the most critical factor affecting Scotland’s marine environment.

Pressures associated with bottom-contacting and pelagic fishing continue to be the most geographically widespread1.

Further Reading

National Marine Plan

Scotland’s National Marine Plan (NMP) was published in March 2015. It covers both Scottish inshore waters (out to 12 nautical miles) - as required by the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 - and offshore waters (12 to 200 nautical miles) - as required by the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009.

The requirement to develop national marine plans stems from an EU Directive (Directive 2014/89/ EU) which established a framework for marine spatial planning. Marine Spatial Planning aims to promote the sustainable development of marine areas and the sustainable use of marine resources by managing competing demands. For example:

Fishing.

Aquaculture.

Marine renewable energy.

Offshore Oil and Gas.

Marine tourism and recreation.

The Scottish and UK Governments agreed that the Scottish Government could publish a single plan to meet the requirements of UK and Scottish legislation. The NMP is required to be compatible with the UK Marine Policy Statement.

The purpose of the NMP is to set out strategic policies for the sustainable development of Scotland's marine resources out to 200 nautical miles. It also provides a strategic framework for marine licensing decisions. Public authorities must take authorisation or enforcement decisions in accordance with the NMP and must also have regard to the Plan in taking other decisions if they impact on the marine area. This includes for example:

Marine licensing - e.g. Dredging, construction works, developments, deposits and removal from the seabed.

Commercial fishing licenses.

Aquaculture development consents.

Ports and harbours - marine license applications by Harbour Authorities.

Legislation requires a review of the NMP every three years. Ministers must consider the review report and then decide whether to replace or amend the Plan. The Scottish Government published the first review in 2018.

The 2018 review found that some of the policies and general aspects of the Plan were particularly effective or useful to decision making. However, various challenges were also highlighted, including that the uncertainties around the UK leaving the EU meant that it was not the right time to amend or replace the plan.

The most recent review of the NMP was published in March 2021. Scottish Ministers will be required to decide whether to amend or replace the NMP early in Session 6. The 2021 review highlighted significant national and global developments that have impacted on the management of marine resources since the NMP was first publshed in 2015 such as:

The UK's exit from the European Union.

The Global Climate Emergency and legal commitment to achieve Net Zero emissions by 2045.

The Covid-19 pandemic.

The 2021 review states:

Our assessment found that there is a clear need to begin work to replace [the National Marine Plan].

Therefore, it seems likely that Scottish Ministers will decide to replace the National Marine Plan.

Regional Marine Plans

The Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 also allows for the development of regional marine plans. However, unlike the National Marine Plan, there is no legal duty to develop regional marine plans. Regional marine plans are intended to provide local ownership of marine planning decisions and to implement the aims and objectives of the National Marine Plan, taking into account local ecosystems and socio-economic circumstances.

Scottish Ministers delegate powers under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 to local groups of stakeholders — known as 'Marine Planning Partnerships' — to develop regional marine plans.

The legislative framework for regional marine planning is shown in the flow chart below.

There are 11 Marine Regions in Scotland designated for the purposes of marine planning. The marine regions were established by secondary legislation under the Marine (Scotland) Act in 2015. Regional Marine Plans can be developed for any of the 11 Scottish Marine Regions. The Scottish Marine Regions are shown in the image below.

So far, three marine regions have received delegated powers to develop Regional Marine Plans:

The Shetland Islands Marine Planning Partnership (Established in March 2016)

The Clyde Marine Planning Partnership (Established in March 2017)

The Orkney Islands Marine Planning Partnership (Established in September 2020)

Both the Shetland Islands Marine Planning Partnership and Clyde Marine Planning Partnership have published draft Regional Marine Plans, but no plans have been approved by Scottish Ministers.

In Session 5, the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee undertook an inquiry into progress in regional marine planning. The Committee published its final report on 17 December 2020. Key findings of the inquiry included:

There has been slow progress in establishing Marine Planning Partnerships.

There has been a lack of guidance from central government.

A lack of clarity in decision making processes which has led to a breakdown in trust between stakeholders and had a detrimental impact on collaborative working.

A lack of finance, resources and expertise was available for regional marine planning.

The Committee also emphasised that regional marine planning has the potential to be a key driver in delivering a Green Recovery and sustainable economic growth in Scotland’s coastal communities. Full findings and recommendations were published in the Committee's final report.

The Scottish Government wrote to the Committee to confirm that it was undertaking an internal review of regional marine planning and would provide a full response to the Committee's findings early in Session 6.

Further Reading:

Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee - Development and implementation of Regional Marine Plans in Scotland: final report (December 2020)

Marine Conservation

In addition to the requirements outlined in the legal framework for managing Scotland's seas above, the Marine Acts contain provision for conservation in the form of Marine Protected Areas. More information on the implementation of Marine Protected Areas and other marine conservation measures are detailed in the SPICe Environment subject profile and briefing on Post-Brexit Fisheries Governance.

Sea Fisheries

Economic and social value

Whilst at a national level, fishing makes a small contribution to GDP, it is very important both economically and socially at a local and regional level. In 2019, Scottish registered fishing vessels landed 393 thousand tonnes of sea fish and shellfish with a gross value of £582 million.

The majority of sea fishing in the UK takes place in Scottish waters and by Scottish vessels. In 2019, landings into Scotland were 68 per cent by tonnage and 64 per cent by value of all landings into the UK. Landings by Scottish vessels accounted for 62 per cent of the tonnage and 60 per cent of the value of all landings by UK vessels in 20191The infographic below shows the relative importance of fishing and aquaculture in Scotland compared to the UK as a whole.

Despite its relatively small contribution to Scotland and the UK's economy, fishing has been at the forefront of political debates around Brexit and negotiations on the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation agreement. This highlights that its importance transcends monetary value. Fishing is an ancient and historic industry that is central to the cultural identity of many coastal communities, particularly those in remote regions and the islands of Scotland. During the EU referendum campaign it was also a totemic issue for sovereignty.

Box 1 below summarises key aspects of the cultural and social value of fishing from a 2014 study by the University of Greenwich which addressed the challenge of incorporating the socio-economic and cultural importance of inshore fisheries to coastal communities more explicitly into fisheries and maritime policy, coastal regeneration strategies and sustainable community development.2 Although this study focussed on the English Channel and Southern North Sea, the values listed equally apply to remote coastal communities in Scotland.

Box 1. The social and cultural value of fishing (adapted from Urquhart and others, 2014)2

Cultural identity – Fishing shapes the identity of those who live in coastal places. It is perceived and attached to the physical environment and objects that form a sense of place (e.g. buildings, fishing gear and boats, artworks, signs etc.) and the fishing activity associated with it.

Individual and group attachment to place – Fishing facilitates and strengthens attachment to place through family and community history, connection between work and home, along with the fishing underpinning social fabric.

Place meaning – The meanings attached to places may differ for those associated with fishing and those not, with fishers relating to the place as a working environment and connection to family/community history. For those not associated with fishing those meanings may focus on the aesthetics of the place, and a (sometimes romanticised) perception of the fishing industry.

Cultural heritage and memory – As an activity that has often taken place for generations, fishing is deep-rooted in many coastal towns and villages. It is represented through the built cultural heritage in the form of the remains of old buildings or equipment, some of which are reused for other purposes. Fishing heritage is also about the non-tangible memories of those who have lived there and these are passed on through oral histories, preserved traditions and representations in museums.

Inspiration – The activity of fishing and the particular nature of coastal environments provides inspiration and wellbeing benefits for those living there, enhancing quality of life. This is also reflected in the work of artists who try to capture the particular quality of these environments.

Connection to the natural world – For fishers this may occur through daily engagement with the marine environment, sometimes in very harsh conditions. For others, living by the coast may provide a certain perspective and sometimes religious and spiritual meanings for those communities.

Tourism – The presence of fishing, or the idea of ‘fishing culture’, provides an attraction for tourism. Visitors like to watch the boats in the harbour, the fishermen unloading the daily catch and they enjoy eating locally-caught fish in a harbourside restaurant. With traditional coastal industries such as fishing and shipbuilding on the decline in many areas, tourism is becoming an increasingly important alternative economic activity.

Knowledge – Fishers may have a particular knowledge about the marine environment in which they work, along with the skills and traditions associated with that activity. Educating and passing on that knowledge is an important part of maintaining cultural identity.

Further Reading

SPICe Briefing -Inshore fisheries (February 2019)

SPICe Briefing - Seafood processing in Scotland: an industry profile (July 2019)

SPICe Briefing - Mackerel (April 2018)

The Scottish Fleet

Scotland’s fisheries are diverse. Targeted species and fishing methods vary considerably in different regions of Scotland’s waters. In total, there were 2,098 active Scottish registered fishing vessels in 2019. The number of fishers working on these vessels was 4,886.1

Target species can be broadly categorised as:

Demersal – those living close to the sea bottom (e.g. cod, haddock, whiting).

Pelagic – migratory species living in the mid water (e.g. herring, mackerel).

Shellfish – mostly fished inshore from the seabed (e.g. langoustine, crab, lobster, scallops).

Broadly speaking, fishing activity in the North Sea contributes the most in terms of total weight and value. This is focussed mainly on pelagic (mid-water) and demersal (bottom feeding) species. These species accounted for £386 million of landings in 20191. Most of these species are landed in ports on the Northeast coast such as Fraserburgh and Peterhead and in Lerwick, Shetland.

On the west coast, most fishing is carried out by smaller inshore vessels, which make up the majority of the Scottish fleet in total number. These vessels primarily target shellfish such as lobster, crabs, nephrops (langoustine) and scallops. These species accounted for £196 million of landings in 20191. The chart below shows the proportion of fishing activity by Scottish vessels in 2019 by vessel size, species targeted and by region.

Fisheries management

Most aspects of fisheries management are not reserved (and therefore devolved) under the Scotland Act 1998. Marine Scotland, a directorate within the Scottish Government, is responsible for managing the activities of all fishing vessels operating within the ‘Scottish Zone’, as well as all Scottish vessels operating beyond the Scottish Zone. This is defined as covering the North Sea and west of Scotland out to 200 nautical miles. Marine Scotland’s role in fisheries management includes the following:

Licensing of fishing vessels.

Setting catch limits through the allocation of fish quota and limits on fishing effort (time spent at sea).

Setting minimum standards (known as ‘Technical Conservation’) in the ways that fishing activity is conducted, for example by controlling the use of nets.

Monitoring fishing vessels while they are at sea.

Controls on the landing, sale, purchase, transport and traceability of sea fish.

Prior to EU Exit, the framework for fisheries governance was an EU competence under the EU Common Fisheries Policy. Now that the UK has left the EU, it is an independent coastal state, meaning it has control over fisheries management and governance in UK waters.

The UK Fisheries Act 2020 provides the legal framework for the UK to operate as an independent coastal state. The Act retains many of the objectives contained in the EU Common Fisheries Policy but includes new objectives such as the 'national benefit' objective and 'climate change' objective.

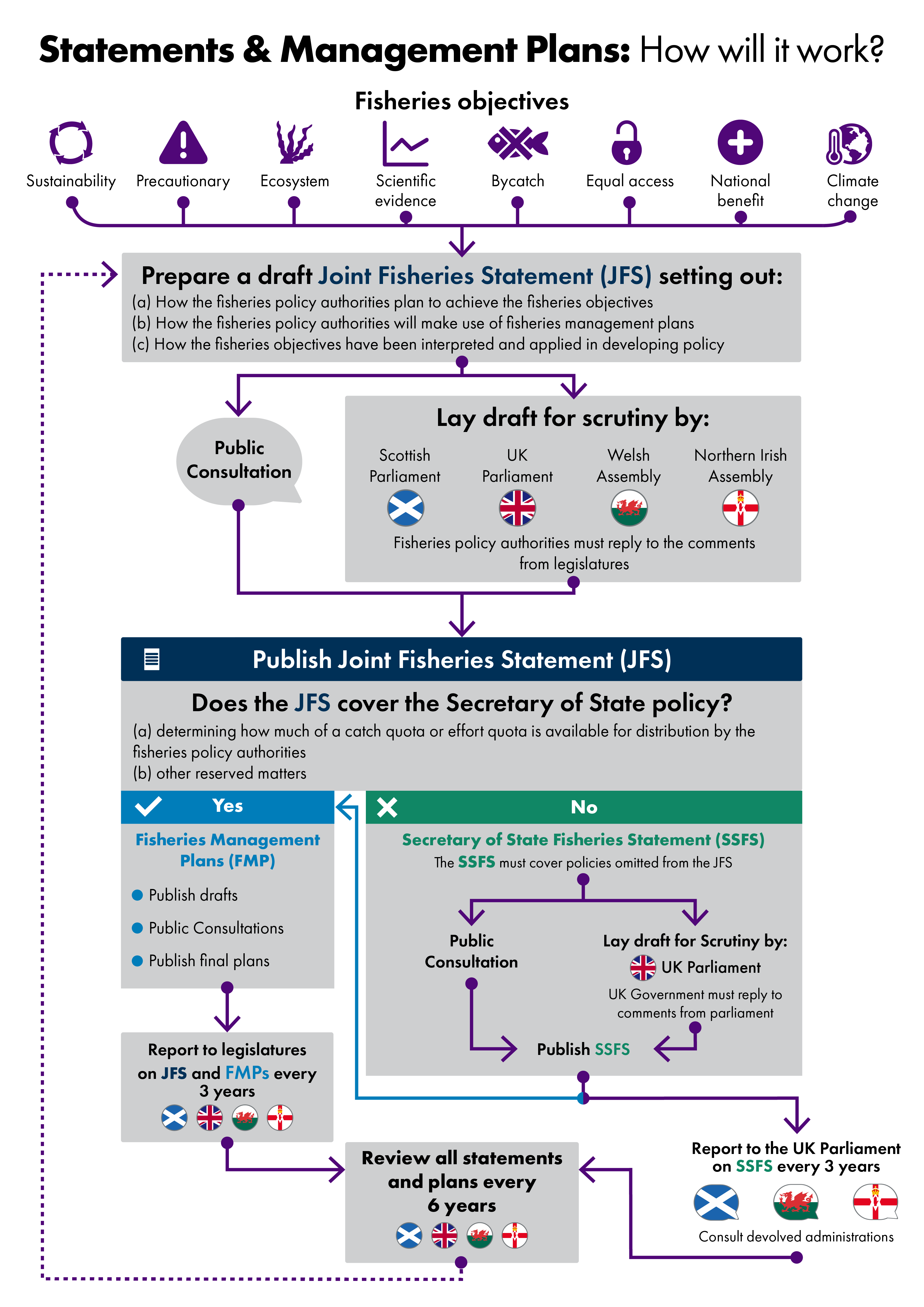

The Act also provides for the licensing of UK and foreign vessels in UK waters and establishes a system of 'Joint Fisheries Statements' (JFS) and Fisheries Management Plans (FMPs) for coordinating a common approach to fisheries management across the UK. The diagram below sets out how this approach will work.

The Scottish Parliament will have a role in scrutinising the development of Joint Fisheries Statements and Fisheries Management Plans. The first JFS and FMPs are required to be adopted by 23 November 2022 (two years after the Act passed).

Fisheries management and the climate and ecological crisis

Effective fisheries management is key to addressing the contribution of commercial fishing to the climate and ecological crisis and improving economic resilience to its impacts.

Scotland's Marine Assessment 2020 identified bottom-contact and pelagic (mid-water) fishing as being the most geographically widespread and direct pressure on the marine environment. Commercial fishing also contributes to greenhouse gas emissions which in-turn affects coastal ecosystems through impacts such as ocean acidification, sea-level rise and the changing ecology and distribution of fish stocks.

The role of fisheries management is recognised in Scotland's Future of Fisheries Management Strategy 2020-2030 which states:

...climate change already has an impact on fish ecology and the distribution of commercially important species, and with a warming climate, will increasingly do so. In a fisheries context, it is important for us to recognise and understand these potential changes and the impacts of our activities, and also to consider the contribution that the fishing sector itself makes to climate change and how we can reduce its impact.

The outcome of forthcoming UN international negotiations on climate change (COP26) and biodiversity (COP15) will likely require a step-change in action to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity loss.

An example relevant to fisheries management is a commitment to conserve at least 30% of the world's land and sea areas through "effective, equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas" as set out in a draft agreement for a new Global Biodiversity Framework ahead of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity COP-15 negotiations in October 2021.1

Scotland has already made good progress in this regard by designating around 37% of its waters as Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).2 MPA designations offer broad protections by making it a criminal offence to intentionally or recklessly damage the species or habitats for which a MPA has been designated. However, the designation of a MPA does not automatically restrict the activities that may take place in the area. Scottish Ministers have powers to increase protections in MPAs by introducing further restrictions on specific activities such as fishing gear restrictions (e.g. bottom -trawling or dredging) or by introducing 'no-take zones'.

Further information about marine conservation and fisheries management can be found in a separate SPICe Environment subject profile and SPICe briefing 'Post-Brexit Fisheries Governance'.

In December 2020, the Scottish Government published its Future of Fisheries Management Strategy 2020-2030. The Scottish Government states the following about the strategy:

This strategy sets out our approach to managing Scotland's sea fisheries from 2020 to 2030, as part of the wider Blue Economy. It explores how we will achieve the delicate balance between environment, economic and social outcomes, and how we will work in partnership with our fisheries stakeholders at home, within the UK, and in an international context, to deliver the best possible results for our marine environment, our fishing industry and our fishing communities. It also considers how, as part of our Blue Economy approach, we can best share the marine space, to ensure we are managing in the right way, and making the best decisions, for the marine environment as a whole and all those who depend on it.3

Further reading:

SPICe briefing - Post-Brexit Fisheries Governance (August 2021)

SPICe briefing - Environment: Subject Profile (August 2021)

SPICe blog series - The future of fisheries management in Scotland (November 2020)

SPICe briefing - The revised UK Fisheries Bill (April 2020)

International obligations and negotiations

The rights and obligations of the UK as an independent coastal state in relation to fishing in its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ - sea area out to 200 nautical miles) are set out in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

For stocks that are solely within the EEZ, a coastal state has exclusive sovereign rights over the conservation and management of marine living resources, meaning that it may decide upon the total allowable catch (TAC) of a fish stock, as well as other conservation and management measures that apply to that stock. In doing so, the coastal state must take into account “the best scientific evidence available to it” (UNCLOS, Article 61(2)) and it is under a duty to ensure that fishing does not lead to overexploitation of the stocks.

In practice, many fish stocks move across international boundaries (so-called shared stocks) and so there may be more than one state with fishing rights. It is estimated that the EU and the UK share more than 100 fish stocks, some of which also straddle onto the high seas (sea areas outside any coastal state's EEZ).

UNCLOS imposes an obligation on states to cooperate in the conservation and management of shared stocks and so relevant states should attempt to reach an agreement on how those stocks should be managed. These agreements are typically undertaken through annual negotiations between coastal states.

Negotiations take place between the EU (on behalf of Member States), the UK and other independent coastal states (e.g. Iceland and Norway) . Separate bilateral negotiations also take place between independent coastal states. Scotland’s interests in these negotiations were previously represented by the UK as part of a broader EU delegation. Now that the UK has left the EU, the UK will negotiate as an independent coastal state. The Scottish Government and Scottish fishing industry representatives will continue to contribute to UK negotiations.

More detailed information on the international framework for fisheries management and marine conservation is provided in a separate SPICe briefing on Post-Brexit fisheries governance (see below)

Further Reading:

SPICe Briefing - Post-Brexit Fisheries Governance (August 2021)

SPICe Guest Blog - The UK as an international fisheries actor – regional and global perspectives (May 2020)

SPICe Blog - The future of fisheries management in Scotland: 3. international influence (November 2020)

Fisheries in the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement

The new EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) took effect on 1 January 2021. A key area of the new agreement was fisheries. Reaching agreement on future access for EU boats to UK waters was a source of disagreement throughout the nine months of the negotiations. Control over access to UK waters was a red line in the negotiations for the UK Government.

The fisheries component of the TCA is particularly important to Scottish fishing industry interests for both catching opportunities and trade in seafood.

The following key provisions feature in the TCA:

Access to waters: The deal provides a continuation of reciprocal access for UK and EU vessels to each other's Exclusive Economic Zone until 30 June 2026. After that, access will be subject to annual negotiations.

Quota shares: The Agreement sets out new arrangements for the joint management of more than 100 shared fish stocks in EU and UK waters. There will be an ‘adjustment period’ over five years implementing a gradual reduction of EU quotas of fish stocks in UK waters shared with the UK. The UK's share of fishing quotas will increase by 25% of the value of the EU catch in UK waters. The agreed quota shares are set out in the annexes of the Agreement. After the adjustment period, the UK and the EU will conduct annual fisheries negotiations regarding the Total Allowable Catch for shared stocks. These negotiations will also cover access arrangements.

Access to EU markets for seafood: The deal maintains tariff-free access to EU markets for seafood products. However, there are now new customs checks requiring more paperwork.

Economic link to the fisheries agreement: The deal ties access to waters to market access through compensation arrangements. This means that if either party breaches the agreement on access to waters or preferential tariffs on fisheries products they can introduce proportionate sanctions. These sanctions can be introduced by ending preferential tariffs not just on seafood, but on any goods included in the TCA, or suspending other parts of the TCA.

For more detailed information on the UK-EU Trade and cooperation agreement, see the further reading below.

Further reading

SPICe briefing - Post-Brexit Fisheries Governance (August 2021)

SPICe briefing - UK-EU Future Relationship Negotiations: Fisheries (April 2020)

Inshore fisheries

Scottish Ministers are responsible for the regulation of inshore fishing around Scotland. Inshore fisheries are primarily regulated by the Inshore Fishing (Scotland) Act 1984. This Act enables Scottish Ministers to regulate fishing in inshore waters (within 6 nautical miles from baselines) by prohibiting one or a combination of the following:

all fishing for sea fish

fishing for a specified description of sea fish

fishing by a specified method

fishing from a specified description of fishing boat

fishing from or by means of any vehicle, or any vehicle of a specific description

fishing by means of a specified description of equipment.

Ministers may also specify the period during which prohibitions apply, and any exceptions to any prohibition. Management of inshore fisheries in Scotland also falls under the following legislation:

The Sea Fish (Conservation) Act 1967 allows regulation of the size of fish landed, gear type that can be used, and restrictions on species that can be landed.

The Sea Fish (Shellfish) Act 1967 allows local management of fisheries through the granting of Several Orders for setting up or improving private shellfisheries, and/or Regulating Orders which give the right to manage exploitation of a natural shellfishery.

A number of organisations are active in the management of Scotland's inshore fisheries at a local and national level. The Inshore Fisheries Management and Conservation group (IFMAC) is made up of industry, environmental NGO and government representatives, and is responsible for resolving issues and developing policies that are of national importance to the sector.

Regional Inshore Fisheries Groups (IFGs) are five non-statutory bodies that have been set up around the coast giving local fishermen a role and voice in inshore fisheries management and wider marine planning developments. The Shetland Shellfish Management Organisation (SSMO) directly manages and regulates most of Shetland's inshore shellfish fisheries through a Regulating Order, giving it the powers to introduce its own regulations and control entry via license permits.

Further reading

SPICe briefing - Inshore Fisheries (February 2019)

SPICe Blog (4 part series) - The future of fisheries management in Scotland (November 2020)

Freshwater fisheries

In contrast to sea fishing, freshwater fishing in Scotland is almost entirely a recreational activity, with the exception of a limited number of estuarine and in-river net fishers using traditional techniques.

There are two main types of freshwater fishing: coarse fishing and game fishing. The term coarse fish refers to any freshwater fish apart from those of the salmon and trout family. The most important game fish in Scotland are Atlantic salmon, sea trout and brown trout.

International Obligations

NASCO (North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organisation) is an international organisation, established by an inter-governmental Convention in 1984. The organisation's objective is to conserve, restore, enhance and rationally manage Atlantic salmon through international cooperation taking account of the best available scientific information.

Only Governments are members of NASCO, which has seven Parties: Canada, Denmark (in respect of the Faroe Islands & Greenland), the European Union, the UK, Norway, the Russian Federation and the United States of America. Scotland, as part of the UK, has obligations to, and contributes to, the work of NASCO.1

Ownership of fishing rights

In Scotland, fishing rights are private and the owners of these rights largely control access to fisheries. It is not the fish themselves that are owned but the right to fish for them.

Salmon fishing rights:

are heritable titles, passed down the generations

may be held with, or separate from, any land

carry with them the right to fish for trout and other freshwater fish.

It is a criminal offence to fish for Atlantic salmon without the legal right or without written permission from the owner of the right. Rights to fish for species other than Atlantic salmon and sea trout belong to the owner of the land contiguous to the river, stream or loch in which the fish are found.

Owners of fishing rights include:

The Crown (managed by Crown Estate Scotland)

private individuals

companies

local authorities

angling clubs and associations1.

Management of freshwater fisheries

Scottish Ministers are responsible for the stewardship of all freshwater fish resources in Scotland.

The Scottish Government – through Marine Scotland Science and Marine Scotland salmon and recreational fisheries policy – plays a vital role in the:

delivery and implementation of fisheries legislation

monitoring and analysis of catch statistics.

Marine Scotland also carries out research to underpin fisheries policy. Since 2008, Marine Scotland Science also regulates the movement of all species of fish other than salmon (meaning both Atlantic salmon and sea trout) to inland waters.

NatureScot is consulted if an application to introduce fish involves waters in, or connected to, sites designated for nature conservation.1

More information is available on the NatureScot and the Scottish Government websites.

The Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) also play a role in considering impacts on fish passage and habitat of developments such as hydropower, and more broadly regulates for pollution prevention and control of the freshwater environment.

A process of reviewing and modernising the management framework for salmon and freshwater fisheries has been underway for a number of years. First, the Aquaculture & Fisheries (Scotland) Act 2013 was passed. Its purpose is to ensure that farmed and wild fisheries - and their interactions with each other - are managed effectively.

Furthermore, a Wild Fisheries Review was undertaken in 2014; the final report of the review panel was published with 53 recommendations “for fundamental change in order to broaden the focus to include all fisheries species, ensure that management is scientifically sound, strengthen democratic accountability, encourage greater participation, and provide confidence that sufficient resources will be available to enable core priorities to be fulfilled.”

The Scottish Government responded with a Wild Fisheries Reform consultation in 2015, and at the start of Session 5 in 2016, there was a commitment to a Wild Fisheries (Scotland) Bill to take forward reform of fisheries management. A consultation on proposals for the Bill and for a National Wild Fisheries Strategy was published in 2016.

In 2017, then Cabinet Secretary for Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform ruled out taking forward some of the proposals following the consultation, and though formally still on the table, a Bill was not brought forward in Session 5.

However, a “multi-year national wild Atlantic salmon strategy” was committed to in the 2019-20 Programme for Government. Though originally delayed by the Covid-19 pandemic, work on the strategy is ongoing. An advisory group is also in operation, made up of a number of statutory bodies and stakeholders, including the Scottish Environment Protection Agency, NatureScot, Fisheries Management Scotland, Scottish Forestry, the Scottish Salmon Producers’ Organisation, and several District Salmon Fishery Boards.

Wild salmon decline

Whilst an overall fisheries management strategy has been ongoing, the Scottish Government has expedited work relating to the decline of Atlantic salmon in Scotland.

Wild salmon have been experiencing decline over a number of decades. Total rod catch of salmon in Scotland reached its lowest number on record in 2018. Rod catches have dropped significantly since 2010, while net catch in estuaries and the coast have been in decline since the 1960s, the latter driven in part by the closure of many coastal fisheries.

Estimates of salmon returning to Scottish coastal waters suggest they have been in continued decline since the 1970s. These trends mirror those observed across the North Atlantic, with Atlantic salmon declining across the four main North Atlantic regions since the 1970s. In Scotland, various other fish species are also in decline, including the sea trout, eel and Arctic charr.

Salmon is a protected species, for which Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) have been designated under the EU Habitats Directive (the provisions of this directive continue to apply in Scotland after EU exit through the domestic legislation that implemented the directive for Scotland). These protected areas were formerly known as Natura 2000 sites, but are now known as European Sites. In 2014, the European Commission had expressed concerns that Scotland had not been sufficiently protecting the conservation status of salmon in these SACs.

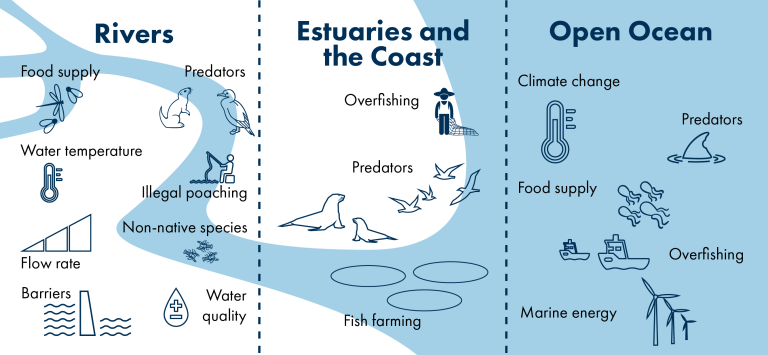

Wild Atlantic salmon have been facing several pressures over a number of years contributing to a decline in populations. Pressures include:

exploitation from fishing

predation and competition

impacts resulting from salmon farming such as parasites and genetic mixing with escaped salmon

invasive non-native species

pollution

changes to habitat.

These are summarised in the image below. More detailed discussion is provided in a SPICe briefing on Wild Salmon (see further reading below).

As a result of these issues, the Scottish Government brought forward legislation to regulate the killing of wild salmon in certain fishery districts in Scotland. The Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Regulations 2016 stated that an assessment of the conservation status of salmon had to be carried out for all inland waters, based on both the stock level and condition of salmon. Following the introduction of the first regulations, Marine Scotland now assesses the conservation status of Scottish rivers each year. This is based on the probability that a population of salmon will meet its conservation target over a five-year period. As such, each river is assigned a grade (category 1 to 3) which determines the recommended management actions. For rivers assigned as grade 3 it is illegal to retain salmon. This means that any salmon caught must be released back into the water (known as 'catch and release'). More information on how rivers are graded can be found on the Scottish Government’s website. The 2016 Regulations also prohibit coastal netting, as a measure directly aimed at protecting stocks returning to inland waters.

Rivers are graded each year, and amendment regulations are laid before the Scottish Parliament annually after a public consultation on the new grades.

Further reading

SPICe briefing - Wild Salmon (August 2019)

SPICe blog -Assessing the conservation status of Scotland’s salmon rivers (July 2019)

SPICe blog -Plenty of fish in the sea? Pressures facing Scotland’s wild Atlantic salmon (July 2019)

Aquaculture

Aquaculture, or fish farming, is the farming of aquatic animals and plants in fresh, brackish or marine water environments. It is a major industry in Scotland’s coastal areas.

Both finfish (e.g. salmon, trout) and shellfish (e.g. mussels, oysters) are farmed in Scotland.

Finfish aquaculture

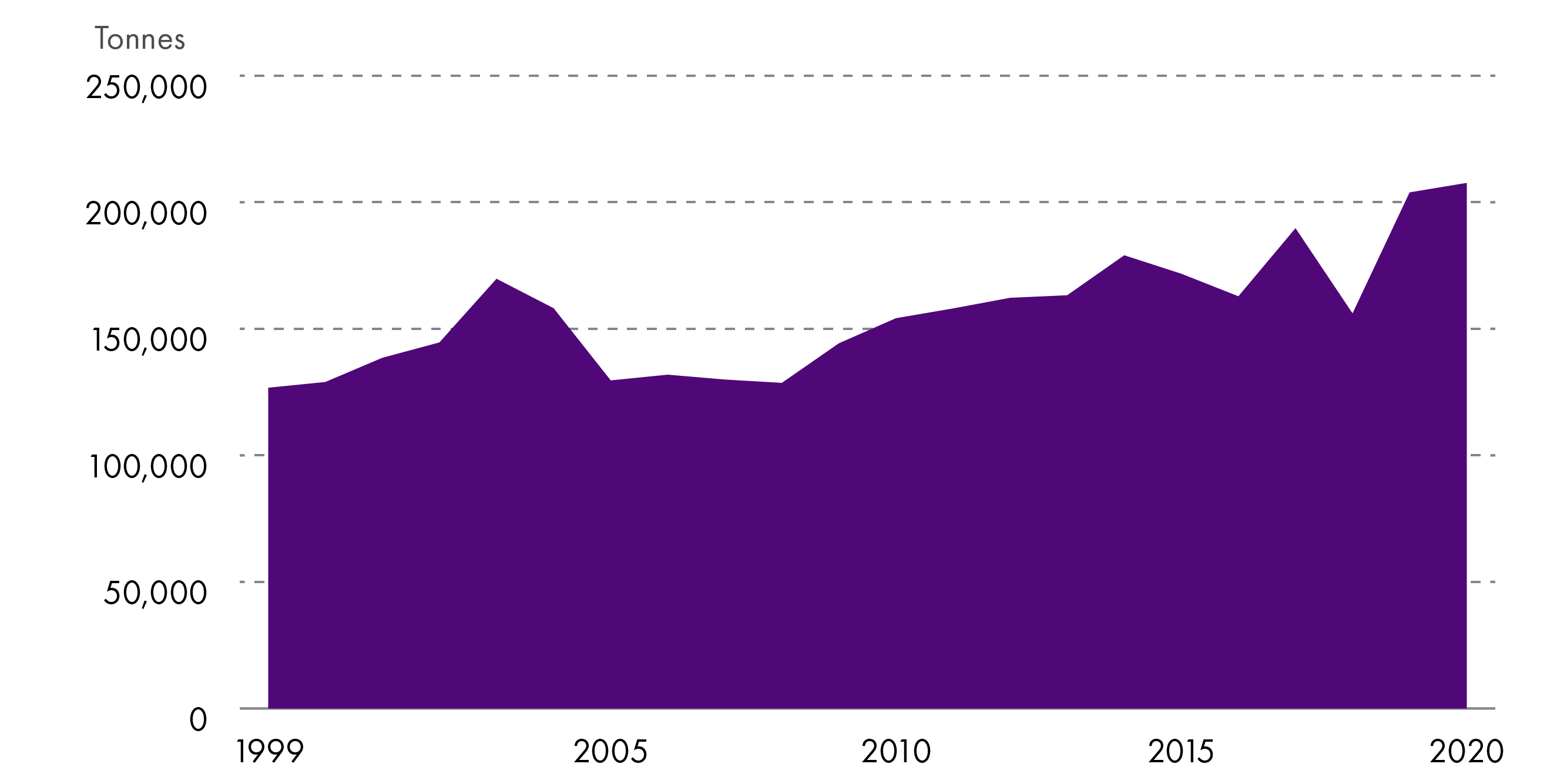

Scotland is one of the top three producers of farmed Atlantic salmon globally (after Norway and Chile, though it is worth noting that both countries produce considerably more than Scotland). Scotland produced 203,881 tonnes in 2019. This was an increase of 47,856 tonnes (30.7%) from 2018 (though this followed a 17.8% decrease from 2017 to 2018). Figure 1 shows the growth of Scottish salmon production in tonnes since 1999.

Other finfish produced in Scotland include rainbow trout (7,405 tonnes in 2019) and brown and sea trout (25 tonnes in 2019).1

Farmed salmon is a major Scottish export; according to the Scottish Salmon Producers’ Organisation, the value of Scottish salmon accounts for more than half of the value of Scottish food and drink exports when whisky is excluded.

However, the regulation of salmon farming has also become a concern in recent years. In Session 5, there was extensive scrutiny of the salmon farming industry in the Scottish Parliament. The Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee held an inquiry into the environmental impacts of salmon farming, commissioning the Scottish Association of Marine Science (SAMS) to review the evidence around this topic and held a call for stakeholder views on the findings of the SAMS review. The ECCLR Committee reported their findings to the Rural Economy and Connectivity (REC) Committee, who held a wider inquiry on Salmon Farming in Scotlandin 2018 and a shorter follow-up inquiry in late 2020.

Issues examined by the committees included:

the environmental impacts of the industry: there are concerns regarding the impact of waste from fish farming on the seabed and the impact of residues of veterinary medicines on the marine environment. In addition, the impact on seal populations was considered. Seals predate on farmed fish, and seal control (including the killing of seals) under licence for the purposes of protecting the health and welfare of farmed fish, or preventing serious damage to fisheries or fish farms was permitted under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 until 2020. However, this justification for licensing was removed by the Animals and Wildlife (Penalties, Protections and Powers) Act 2020. Acoustic deterrent devices, which emit noise to ward off predators may still be used, but more information is being sought on potential impacts on other marine mammals.

animal welfare concerns: concerns included the prevalence of sea lice, a parasite that attaches itself to the skin of the salmon which is common in salmon farming, gill health diseases, and rates of fish mortality.

interaction with and impacts on wild fish: wild salmon populations have experienced a dramatic decline (see section on freshwater), and face a number of pressures, of which salmon farming is one. Escaped farmed fish interacting with wild salmon is generally not desirable for a number of reasons, including spreading pests (like sea lice) or diseases, or inter-breeding between wild and farmed stock which is thought to be able to result in less resilient wild populations.

the impact on rural communities: evidence of both positive and negative social and economic impact was presented to the REC Committee. Job creation both in the industry itself and in the supply chain was seen as important and significant for rural communities, and operators emphasised their contributions to community projects. Conversely, others provided evidence of detrimental impacts on other marine sectors, e.g. interactions with the catching sector, effects on wild salmon fisheries, and concern for environmental impacts affecting marine and coastal tourism. Questions have also been raised regarding whether the Scottish Government has considered the impact on other industries when evaluating the economic benefits of fish farming.

Both committees reported on their findings citing concerns about expansion of salmon farming without regulatory reform. The ECCLR Committee stated in their letter to the REC Committee that “the Committee is supportive of aquaculture, but further development and expansion must be on the basis of a precautionary approach and must be based on resolving the environmental problems. The status quo is not an option.” (emphasis in original). The REC Committee, similarly, concluded that while it acknowledges the economic contribution of salmon farming, “if the industry is to grow, the Committee considers it to be essential that it addresses and identifies solutions to the environmental and fish health challenges it faces as a priority”.

The industry has continued to expand, as outlined in Figure 1 above, and there has been some regulatory reform. The Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) has outlined a new Finfish Aquaculture Sector Plan and finfish aquaculture regulatory framework. The Scottish Government has also brought in new regulation for weekly reporting of sea lice.

However, members questioned whether this change has been sufficient in a follow-up inquiry in November 2020. Expansion of salmon farming also continues to be divisive among communities. Whilst the industry employs 1651 staff1, most of whom work in rural communities local to existing or proposed salmon farms. Communities have also mounted opposition campaigns with concerns for the environment and other industries in the areas.

In their 2021 election manifesto, the SNP pledged to

reform and streamline regulatory processes so that development is more responsive, transparent and efficient. At the heart of our new approach will be a new, single determining authority for farm consents, modelled on the regulatory regime in Norway. This will bring greater clarity, transparency and speed to the process. We will expect producers to contribute much more to the communities and local economies which support them so we will also explore how a Norwegian-style auction system for new farm developments might generate significant income to support inspection and welfare services, provide real community benefit on islands and in remote rural areas and support innovation and enterprise.4

More information on salmon farming can be found in the SPICe briefing, Salmon Farming in Scotland.

Shellfish aquaculture

Shellfish aquaculture also occurs in Scotland, but at a smaller scale compared to finfish aquaculture, producing 6,699 tonnes for the table and 3,493 for on-growing (sales to other businesses for further growth) in 2019.

In 2019 (the most recent available figures) Scottish shellfish aquaculture producers cultivated mussels, Pacific oysters, native oysters, queen scallop and scallop, though mussels and Pacific oysters are the most common. Mussels make up 58% of Scottish farmed shellfish for the table and 55% of shellfish farmed for on-growing; Pacific oysters make up approximately 40% of shellfish farmed for the table and for on-growing.1

Mussels are grown by dangling ropes into the sea for larval mussels to latch to and grow on. They are naturally stocked by larval mussels coming in off the tide and do not need to be fed; they feed on plankton occurring in the sea. Oysters are grown in bags or flat cages in tidal areas, and also filter-feed on naturally occurring organisms in the sea. As a result, by comparison to finfish aquaculture, shellfish aquaculture is thought to have a lower environmental impact.2

Seaweed aquaculture

Seaweed cultivation is an emerging form of aquaculture in Scotland. Seaweed can be utilised for a variety of purposes such as:

human consumption

animal feed

biofuel

fertiliser

cosmetics

pharmaceuticals

biomaterials (e.g. alternatives to petroleum-based plastics)

mitigating climate change (carbon sequestration).

Seaweed is mostly cultivated in coastal areas on long-lines suspended below the water (often in grids) and fixed in place by buoys and anchors. Seeding of long lines normally takes place in autumn and is harvested in the spring and summer. Seaweed is usually harvested by hand or with a mechanical cutter from a boat.1

The wide variety of uses of seaweed provides the potential for significant economic activity and employment in coastal communities. However, there is concern that expansion of this industry may have adverse environmental impacts. These include:

damage to seabed habitats and seabed shading

impact on marine species (e.g. entanglement of marine mammals, disturbance of migration routes or breeding/feeding grounds)

disturbance of tidal currents and water circulation

impact on genetic diversity of wild seaweed

spread of disease/pathogens

introduction of invasive species

pollution from ropes or other equipment

localised nutrient depletion

visual impacts

displacement of other marine users (e.g. Commercial fishing, recreation)2

the impact on natural blue carbon resources (e.g. Kelp beds).

There is therefore a need for careful consideration of potential impacts to ensure the industry expands in a sustainable way. This will likely require further legislation to ensure effective regulation.

Current regulation

The Scottish Government's Seaweed cultivation policy statement (published 26 March 2017) provides current guidance on seaweed aquaculture developments. Seaweed cultivation sites require a license from the Marine Scotland - Licencing and Operations Team (MS-LOT) and a lease from Crown Estate Scotland.

An 'Algal Farms Marine Licence Application' must be submitted. This must detail the proposed date of installation, area to be covered, design of the farm, and mitigation measures to prevent adverse environmental impacts and ensure the development meets the requirements of Scotland’s National Marine Plan.

To obtain a seabed lease from Crown Estate Scotland, applicants must provide details of the species to be cultivated, and the equipment and the area to be used (including the space required for moorings and navigation marks). They must also have a business plan that shows the proposal is viable, and how infrastructure will be removed at the lease termination.3Seaweed cultivation does not currently require Local Authority Planning Consents.

A more detailed overview of the regulatory and legislative framework for seaweed cultivation and harvesting can be viewed in a document produced for the Scottish Government's Seaweed Review Steering Group (see further reading below).

The Scottish Government is currently considering the need for further regulation in this area. This builds on the publication of a Wild Seaweed Harvesting Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) in 2016.

Ban on mechanical kelp harvesting

Wild kelp can be harvested or gathered for personal or commercial use. During passage of the Crown Estate (Scotland) Act 2019, concern was raised about the environmental impacts of mechanical kelp harvesting, including potential impacts on marine ecosystems and blue carbon resources (see further reading on blue carbon below).

The issue was highlighted after environmental organisations objected to proposals by Marine Biopolymers LTD for large scale mechanical kelp harvesting on the west coast of Scotland.4The proposal involved the use of a trawled "comb-like" mechanical device that targets mature (approximately 5-year minimum growth) kelp.5 This method of harvesting is considered to be more damaging than other methods (see table below).

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Hand cutting or picking | Harvesting living species by hand at low tide using tools such as serrated sickles or scythes. |

| Trawling/Sledging/ Dredging | Using a device which tears plants larger than a certain size from the substrate and leaves smaller plants for re-growth. Devices include the Norwegian kelp dredge designed to harvest Laminaria hyperborea and the Scoubidou, designed to harvest L. digitata. These devices operate on rocky substrate, so differ from other forms of dredging (e.g. scallop dredging) that physically disturb the substrate, although some physical disturbance of the substrate will still occur in deploying these methods. |

| Mechanical 'hedge' cutting | Specialised vessels called mechanical seaweed harvesters that work close to the shore and cut the living seaweed as the stalks float above the seabed. These vessels include the Norwegian suction/cutter harvester which is designed to harvest Ascophyllum nodosum (intertidal seaweed - not a kelp species). |

| Hand gathering | The collection of beach-cast species by hand. |

| Mechanical gathering | The collection of beach-cast species using tractors or mechanical excavator |

An amendment was introduced at Stage 2 of the Crown Estate (Scotland) Bill seeking to effectively ban the mechanical harvesting of kelp for commercial purposes. The amendment received support from the Scottish Government and was adopted in section 15 of the Scottish Crown Estate Act 2019. In response to the issues raised during passage of the Act, the Scottish Government established a Seaweed Review Steering Group. The Steering Group is made up of organisations from various sectors representing conservation, science, enterprise, biotechnology, fisheries and the seaweed industry association. The group's remit is to:

advise and inform the review's strategic programme of work

advise on current and historic seaweed related science and research ensuring that the review uses the most up to date approaches and considers the best available evidence

advise on how the review can be future proofed so that it is relevant as the sector evolves

establish a mechanism to coordinate and help prioritise future research requirements as identified during the review

provide support and ensure that the review reflects the views of a wide range of stakeholders

establish a mechanism to ensure regular and clear public reporting of progress as set out in a communication strategy to be agreed and followed by the membership7.

Further reading:

Scottish Government:

Seaweed Review Steering Group: seaweed regulatory and legislative framework

Scottish Government:Seaweed Review Steering Group: terms of reference

SPICe Briefing:Kelp harvesting (November 2018)

SPICe briefing:Blue Carbon (March 2021)

SPICe blog:Out of the blue: Is blue carbon the next frontier for climate change mitigation in Scotland? (March 2021)

The Scottish Crown Estate

The Scottish Crown Estate is a collection of ancient rights, functions and assets owned by the Monarch in right of the Crown. The Scottish Crown Estate assets include a diverse portfolio of property, rights and interests. The total property value of the Scottish Crown Estate assets was approximately £426.2 million at 31 March 2020. Scottish Crown Estate assets are managed by Crown Estate Scotland - a statutory body established under the Scottish Crown Estate Act 2019.

The Scottish Crown Estate includes leasing of the seabed out to 12 nautical miles, Rockall, 37,000 hectares of rural land; rights to most naturally-occurring gold and silver; and approximately half of Scotland’s foreshore including 5,800 licensed moorings; 750 aquaculture sites; and salmon fishing rights.1

Beyond 12 nautical miles, the seabed itself is technically ownerless, but the Crown Estate Scotland has rights over certain commercial activity to the edge of the continental shelf and the 200 nautical mile limit (the exclusive economic zone) – this includes offshore renewable energy, marine mineral extraction and gas or carbon storage.

Scottish Crown Estate assets were previously managed by The Crown Estate at UK level. The Smith Commission (2014) recommended that the management of Crown Estate assets in Scotland, and their revenues, should be devolved. The Scotland Act 2016 enabled HM Treasury to develop a Transfer Scheme to devolve powers over the revenue management of Scottish assets and this came into force on 1 April 2017.

This was followed by the Scottish Crown Estate Act 2019 which sets out the statutory duties and obligations on Crown Estate Scotland as the manager of the Crown assets in Scotland. The 2019 Act also paves the way for other bodies to become managers of Crown assets in Scotland and for other organisations to seek delegated responsibility for specific assets once the relevant provisions are brought in to force.

The 2019 Act requires that managers of Scottish Crown Estate assets must act in the way best calculated to further the achievement of sustainable development in Scotland, and seek to manage the assets in a way that is likely to contribute to the promotion or improvement in Scotland of:

economic development

regeneration

social wellbeing

environmental wellbeing

sustainable development.2

More information can be found on the Scottish Government and Crown Estate Scotland websites.

Local Pilot Scheme

In 2018, Crown Estate Scotland launched its 'Local Pilot Scheme'. Crown Estate Scotland state that its aim is:

to encourage local authorities, development trusts and other eligible bodies to manage Scottish Crown Estate land and property rights in their local area.

and

will enable us to work with others to test different methods of managing assets, empowering communities and giving people more say in decisions that impact the land, foreshore and sea near where they live.

Thirteen applications were received in the initial application round with four projects being taken forward as 'preferred' projects in the scheme. These projects are led by:

Comhairle nan Eilean Siar and Galson Estate Trust

Forth District Salmon Fishery Board

Orkney Islands Council

Shetland Islands Council.

Summaries of these projects are available on the Crown Estate Scotland Website.1

These pilot projects may pave the way for more permanent delegation of the management of Crown Estate Assets at a local level. Section 3 of the Scottish Crown Estate Act 2019 allows Scottish Minsters to transfer the management of Crown Estate assets to certain persons or groups such as a local authority, Scottish Harbour Authority or a community organisation. This can be achieved through secondary legislation under the Act.

Marine and Fisheries Budget

Marine Scotland is a Directorate of the Scottish Government and is responsible for the integrated management of Scotland's seas.

In Session 5, the Marine Scotland budget was included within the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform portfolio and the fisheries budget was included within the Rural Economy and Tourism portfolio. The tables below show the budget for marine and fisheries for 2019-2022.

| Level 3 | 2019-20 Budget (£m) | 2020-21 Budget (£m) | 2021-22 Budget (£m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Scotland | 64.7 | 65.5 | 84.0 |

| Total Marine | 64.7 | 65.5 | 84.0 |

| Level 3 | 2019-20 Budget (£m) | 2020-21 Budget (£m) | 2021-22 Budget (£m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Fund Scotland | - | - | 14.5 |

| EU Fisheries Grants | 14.1 | 14.1 | 14.1 |

| Fisheries Harbour Grants | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Marine EU Income | (9.2) | (9.2) | (9.2) |

| Total Fisheries | 5.9 | 5.9 | 20.4 |

The SNP manifesto for the 2021 Scottish Parliament election committed to developing a marine strategy and setting up a "dedicated agency to put our marine assets at the heart of the blue economy". It also committed to developing a 'Blue Economy Action Plan' (see next section below).

It is not clear at this stage what impact this commitment will have on the structure of governance for marine and fisheries and the budget. In the 2021-22 budget, the Scottish Government stated:

The Budget will also renew our work across the wider marine economy, guided by the new Blue Economy Action Plan. We will support fisheries and seafood sector priorities and potential realignment after EU Exit, delivering sustainable activity which will in turn support the economies of coastal communities. Wider support will also deliver investment in the seafood processing sectors, improving efficiency and reducing emission. However necessary, replacement funding for the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund is estimated to be £62 million – as such, a UK Spending Review allocation of just £14 million will severely limit the scope of aspirations.

Blue Economy Action Plan

In its Programme for Government 2020-21, the Scottish Government committed to developing a 'Blue Economy Action Plan' (BEAP). The programme for Government stated the following about the BEAP:

We will set out clear actions to strengthen the resilience of our marine industries ranging from renewable energy to fisheries (and the marine science, research and innovation which underpin them) and to support coastal communities, recognising the vital importance to our marine economy of the abundant natural capital in Scotland’s seas and rivers. This will include supporting the sustainable growth of aquaculture – which provides many jobs in the most remote locations and island communities – by improved regulatory processes, based on the application of available evidence and continued enhancements in the scientific base, to provide more benefit to the communities where aquaculture is based. Our Blue Economy Action Plan will harness and bolster Scotland’s international profile as a successful, modern and innovative maritime nation. Our approach will encompass work across the broad range of marine sectors, including seafood, tourism, energy, transport and science.

No further details of the Plan have been published but the Scottish Government's Future of Fisheries Management Strategy 2020-2030 indicates that it will aim to provide a more holistic approach to managing marine natural resources and industries.

A truly holistic Blue Economy approach also recognises that our many marine industries share the same common space and benefit from the joint stewardship of its amazing natural abundance. Our Blue Economy action plan will therefore reflect the vital importance to our marine economy of the rich natural capital in Scotland’s seas and rivers.

and;

a Blue Economy approach also provides the framework for managing the co-existence of different marine interests in the same shared space, enabling a transition from a mind-set of ‘environment vs economic growth’ to a mind-set of ‘shared stewardship of natural capital facing common challenges.’ We do not manage our fisheries in isolation and joining up our approach across the marine environment, for example by considering competing marine sectors and priorities in our decision making, and also onshore interests, is vital to success. Through delivery of this strategy, and in the wider Blue Economy Action Plan, we will have a renewed focus on integrating fisheries interests into the wider marine planning process and, linked to this, ensuring that fishing impacts are considered as part of our wider ecosystem-based approach.

Parliamentary scrutiny

| Requirement | Parent legislation | Format | Timescale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Scotland budget | N/A | Budget legislation | Annual |

| Review and report of the implementation of the National Marine Plan | Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 | Report to Parliament | Every 3 years (most recent report published March 2021) |

| Report and review of Joint Fisheries Statements and Fisheries Management Plans under the Fisheries Act 2020 | Fisheries Act 2020 | Report to legislatures |

|

| International Fisheries Negotiations (catch limits and management of shared fish stocks). | N/A | Ministerial Statement | Annual |

| Salmon river gradings (assessment of conservation status and corresponding management measures for every river) | Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Regulations 2016. | Consultation and Amendment regulations made by Scottish Statutory Instrument | Annual - consultation in Autumn. Regulations laid to come into effect at the start of each financial year. |

| Scottish Marine Protected Area network report | Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 | Report to the Scottish Parliament | Every 6 years (most recent report published December 2018) |