Land Use and Rural Policy: Subject Profile

This briefing outlines issues and policy developments in relation to land use and rural policy. It outlines the context for Scotland's land use policies and addresses each of Scotland's major land uses in turn, highlighting key legislation and topical issues ahead of Session 6 of the Scottish Parliament.

Key points

98% of Scotland's land area is classed as rural. As a result, Scotland's land use and rural policies cover a large geographical area.

80% of Scotland's land is used for some form of agriculture. Forestry accounts for 12.5% of Scotland's land.

Rural affairs encompass more than land use policy. Rural employment is diverse, and rural areas are touched by a wide range of policy areas in addition to land use, including fisheries and marine policy, transport and digital connectivity, housing, social security, education, environment and economic development. This briefing focuses on the land use policy elements.

Land use sectors have been greatly affected by EU Exit. New approaches are being developed to replace previous EU-wide policies, and future changes to policy and regulation are anticipated.

Future trade agreements and the UK internal market may also affect both policy and practice. New trade agreements may impact land use sectors and the markets and supply chains linked to them. As a result of EU Exit, the UK internal market also plays a role in future policy and regulatory development in these areas.

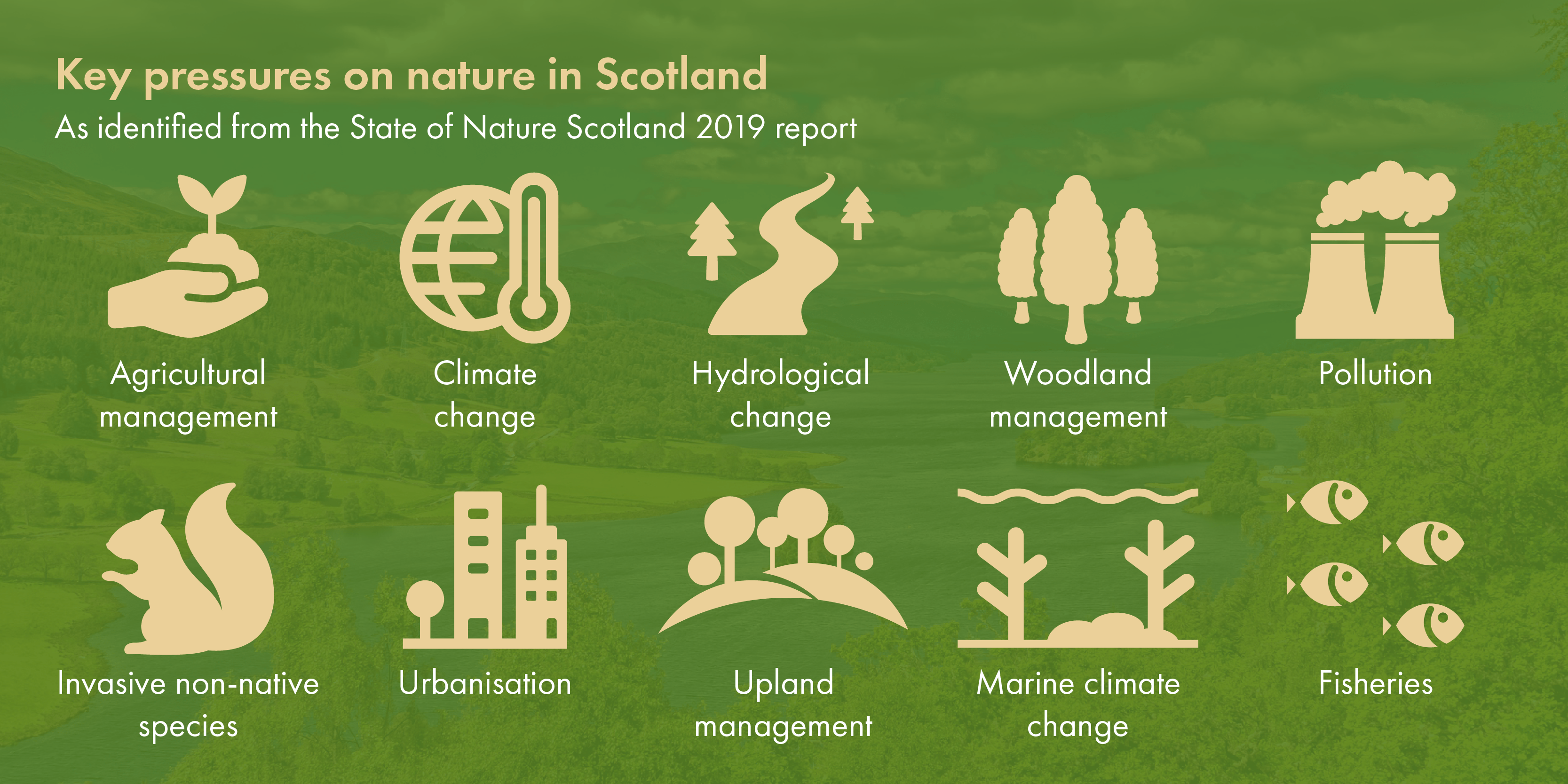

Climate change and biodiversity loss are urgent drivers for the development of new land use policies. Food and timber production - at home and abroad - will be (and already is being) affected by climate change and biodiversity loss. The way that land is used and managed has the potential to exacerbate these issues, but can also provide significant solutions.

Strategic land use planning aims to drive land use and rural policy to deliver national objectives. Overarching national strategies, such as the third land use strategy and the upcoming fourth National Planning Framework, aim to look at land use holistically. Looking at land uses strategically is also being piloted at a regional level, through regional land use partnerships.

There is cross-over between land use and rural policy and other policy areas, for example, in relation to food policy, spatial planning, environment and climate change, land reform and animal welfare.

In figures

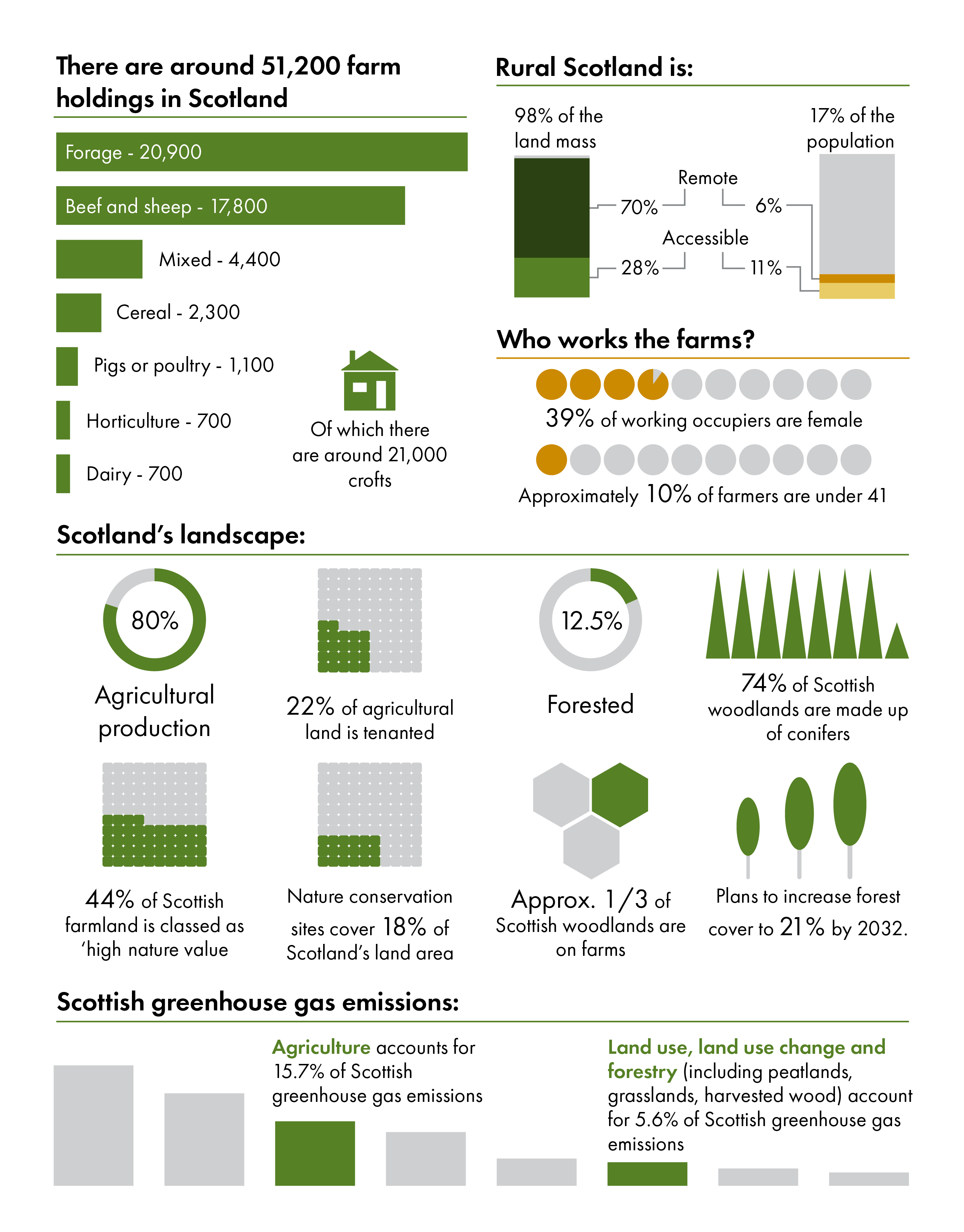

Figure 1 below highlights key statistics in relation to land use and land management, in the context of Scottish rural affairs.

*NB: 'Forage' refers to holdings that grow forage crops to feed livestock, such as hay or silage.

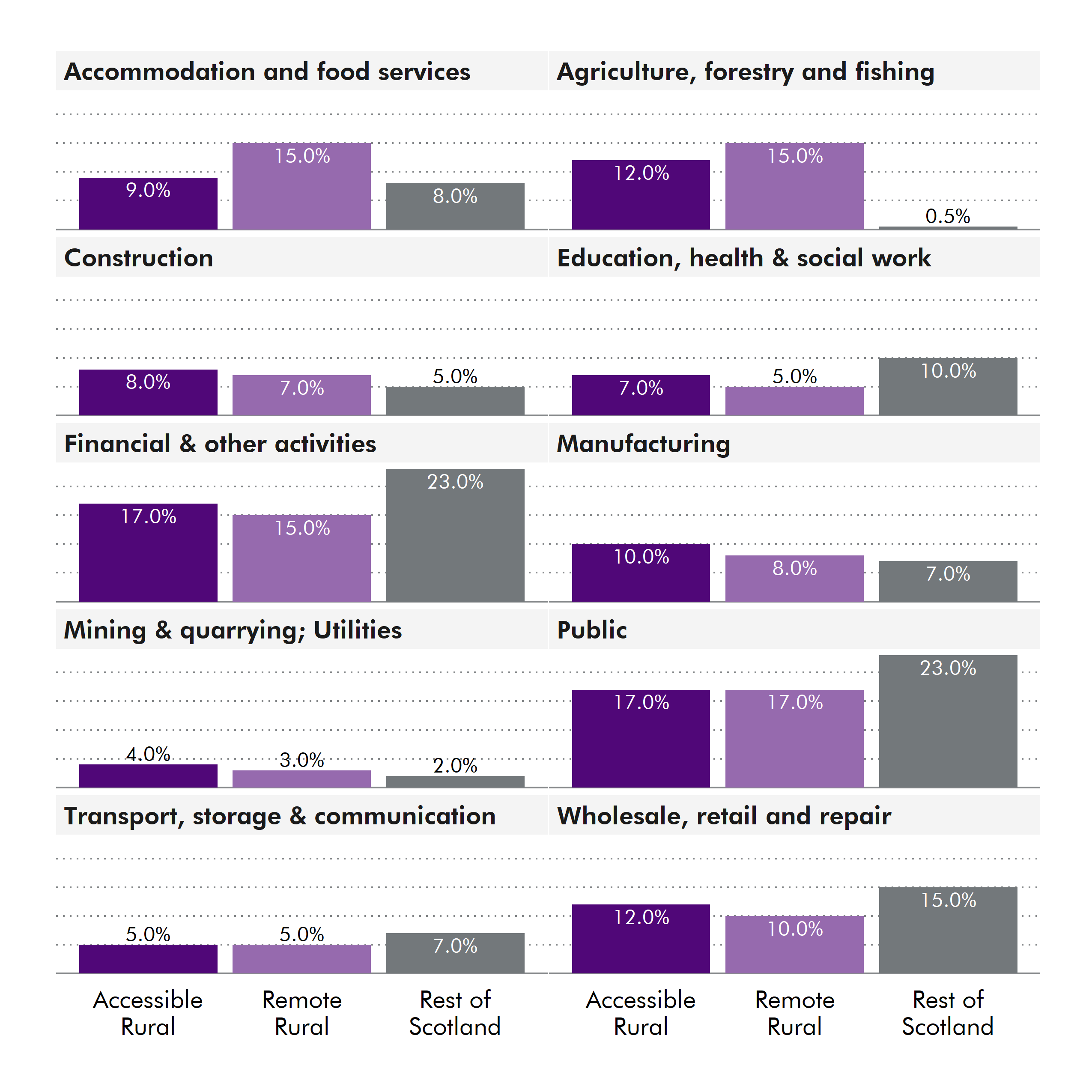

Though most people who work in land use activities are based in rural Scotland, land use activities only make up a part of rural employment. In remote rural areas of Scotland, the public sector accounts for the largest proportion of employment, at 17%, closely followed by ‘accommodation and food services’, ‘agriculture, forestry and fishing’, and ‘financial and other activities’ which each account for 15% of employment (see Figure 2).

Rural affairs

Rural affairs encompass more than land use policy. As highlighted in the previous section, rural employment is diverse, and rural areas are touched by a wide range of policy areas in addition to land use, including fisheries and marine policy, transport and digital connectivity, housing, social security, education, environment and economic development.

However, rural areas face particular challenges and it is recognised that they sometimes require bespoke solutions. As a result, in addition to rural angles on the diverse range of policy areas listed above, the Scottish Government has produced strategies and convened groups to address specifically rural issues. Examples of these include:

Research on rural planning policy to 2050, to inform the development of the fourth National Planning Framework;

A particular focus on rural communities in commitments to ensure digital connectivity for all of Scotland;

In addition, particular considerations for rural areas are addressed within wider policy documents. For example, in the Scottish Government's first national population strategy, rural depopulation is raised.

Furthermore, economic development in largely rural parts of Scotland is promoted through two enterprise agencies. Highlands and Islands Enterprise supports economic and community development in the north and west of Scotland, and the South of Scotland Enterprise supports Dumfries and Galloway and the Scottish Borders.

Strategic Land Use

When ‘land use’ is discussed, it is often in the context of rural Scotland. However, land use is not only a rural issue as land is required for a wide variety of things, including for housing, transport, and other infrastructure such as renewable energy and public and private buildings. Increasingly, policymakers have looked to a more holistic – or strategic – way of looking at land use in Scotland. This recognises that land is finite, that maximizing the number of benefits that a given piece of land provides may be necessary to deliver public policy objectives for the economy, environment and society, and that, sometimes, looking at a landscape scale is necessary to achieve those goals.

This has been driven in large part by discussions around climate change. The Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 introduced a duty on Scottish Ministers to produce a Land Use Strategy every five years. The first strategy was published in 2011, and the first update was published in 2016. The Land Use Strategy that is currently in force was published in March 2021. Following the passage of the Climate Change (Emissions Reductions Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019, Scottish Ministers are now required to report to the Scottish Parliament on progress towards implementing the objectives, proposals and policies of the land use strategy, at the end of each financial year.

Box 1: The duty to produce a Land Use Strategy

Section 57(1), (2), and (3) of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 state:

57 Duty to produce a land use strategy

(1) The Scottish Ministers must, no later than 31 March 2011, lay a land use strategy before the Scottish Parliament.

(2) The strategy must, in particular, set out—

(a)the Scottish Ministers' objectives in relation to sustainable land use;

(b)their proposals and policies for meeting those objectives; and

(c)the timescales over which those proposals and policies are expected to take effect.

(3) The objectives, proposals and policies referred to in subsection (2) must contribute to—

(a)achievement of the Scottish Ministers' duties under section 1, 2(1) or 3(1)(b) [the net-zero emissions target, interim targets and annual target];

(b)achievement of the Scottish Ministers' objectives in relation to adaptation to climate change, including those set out in any programme produced by virtue of section 53(2) [requiring Scottish Ministers to set out a climate change adaptation programme]; and

(c)sustainable development.

In addition, the Scottish Government and civil society organisations have looked to regional approaches to strategic land use. Following two pilots in Aberdeenshire and the Borders between 2013 and 2015, the Scottish Government included a policy in the 2016 Land Use Strategy to “encourage the establishment of regional land use partnerships”. The aim of the partnerships is to bring together local people, land managers and other stakeholders to better integrate land uses and produce regional land use frameworks. The aim of the frameworks is to identify how national, regional and local priorities will be delivered.

In its advice to the Scottish Government on rolling out regional land use partnerships and frameworks, the Scottish Land Commission stated that “We propose Regional Land Use Frameworks should be indicative spatial plans which identify opportunities, choices and priorities for all land use, including forest and woodland strategies, in order to stimulate delivery and be accessible to all within a region”.

Following several commitments over the final years of Session 5 (including in the 2019-20 Programme for Government, and the most recent update to the Climate Change Plan in December 2020), the Scottish Government established a further five pilot areas “to test approaches to partnership governance that best suit the local situation and priorities” and inform future decisions on establishing partnerships.

Box 2: Opportunities for Parliamentary scrutiny in Session 6

The development of regional land use partnerships is a key commitment of the Scottish Climate Change Plan Update.

Annual reports outlining progress towards the Land Use Strategy's objectives are required under the Climate Change (Emissions Reductions Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019.

Fourth National Planning Framework

The Fourth National Planning Framework (NPF4) is due to be published early in Session 6, following a position statement in November 2020. The National Planning Framework sets out a spatial plan for Scotland and outlines priorities for planning and development.

Given that most development requires some land, there are intersections between land use policy and planning policy. For instance, under the Planning (Scotland) Act 2019, the planning authorities are to produce a ‘forestry and woodland strategy’ setting out policies and proposals in relation to conservation, protection and expansion of woodlands.

The Scottish Government’s position statement ahead of NPF4 made reference to links with strategic land use, noting that:

NPF4 will need to align with a wide range of policies relating to rural development including our National Islands Plan, Forestry Strategy, the Rural Economy Action Plan and the Land Rights and Responsibilities Statement. There are particular opportunities to link planning more closely to the Land Use Strategy and Regional Land Use Partnerships, to achieve an approach to future development at national, regional and local scales, that more fully supports, and is supported by, wider land use management.

Moreover, there has also been an ambition to consider how planning policy may support vibrant rural communities and address any particular place-based challenges in rural Scotland.

More information on planning priorities can be found in the Scottish Government’s position statement.

Box 3: Opportunities for Parliamentary scrutiny in Session 6:

The Fourth National Planning Framework is due to be published early on in Session 6.

Major land uses in Scotland

Agriculture

What does the sector look like?

6.2 million hectares of land is farmed in Scotland (approximately 80% of the total land area). Of this area, 86% is classified as Less Favoured Area (LFA)1. Land becomes classified as LFA if it is considered to be more difficult to farm because of climate and soil conditions. In terms of agricultural production, LFA areas are mainly used for extensive production of beef cattle and sheep.

Cereal and crop production and mixed farming is mainly limited to the drier, fertile areas of the East and Northeast of Scotland, with dairy farming on the better quality land in the wetter Southwest.

Cereals (wheat, barley and oats) accounted for 73% of the area of crops grown in 2018 (excluding grass), with 69% of that being barley1 - a key ingredient in Scotland's whisky production. Of the remaining crops grown (excluding grass), oilseeds make up 5.7%, potatoes 4.8%, fruit and vegetables 3.7%, and other crops combined make up 12.7%.

In 2018, Scotland had approximately 1.76 million cattle, 6.59 million sheep, 316,000 pigs and 14.5 million poultry. Cattle and sheep tend to be located on LFA holdings, reflecting the large areas of grassland and rough grazing in these areas. In contrast, pigs and poultry tend to be located on non-LFA holdings.1

Though potatoes, fruit, and vegetables make up a smaller proportion of the land area used for agriculture, these are nonetheless important sectors for Scotland. Scotland grows 70% of the UK's seed potatoes - the potato tubers that are planted to produce a potato crop - and is responsible for 80% of seed potatoes exported from the UK.4 Soft fruits like raspberries and strawberries are another important crop in Scotland. These are generally grown in polytunnels, and are mainly concentrated in fertile areas in the east of Scotland.

.jpg)

Maps showing the distribution of agricultural production across Scotland can be explored on the Scottish Government's website.5

44% of Scotlands farmland was classed as 'high-nature value' - land that is especially valuable for biodiversity - in 20136, and in 2019, 2.1% of Scotland's agricultural land was under organic management7. 'Organic farming' is an approach to food production which does not use artificial fertilisers, pesticides or genetically modified organisms and follow a common set of practices such as long crop rotations8. To be certified as organic, agricultural products must be produced to a specific set of standards that are set out in regulation. The SNP set out a manifesto commitment to "double the amount of land used for organic farming - and double the amount of organic produce that comes from Scotland with a focus on more of it being used in public sector food procurement."

In Scotland, agriculture accounted for 0.8% of gross value added (GVA) at basic prices in 2018, with 2.5% of the workforce employed in the sector.1 However, the food and drink sector as a whole is larger, accounting for one in five manufacturing jobs.10.

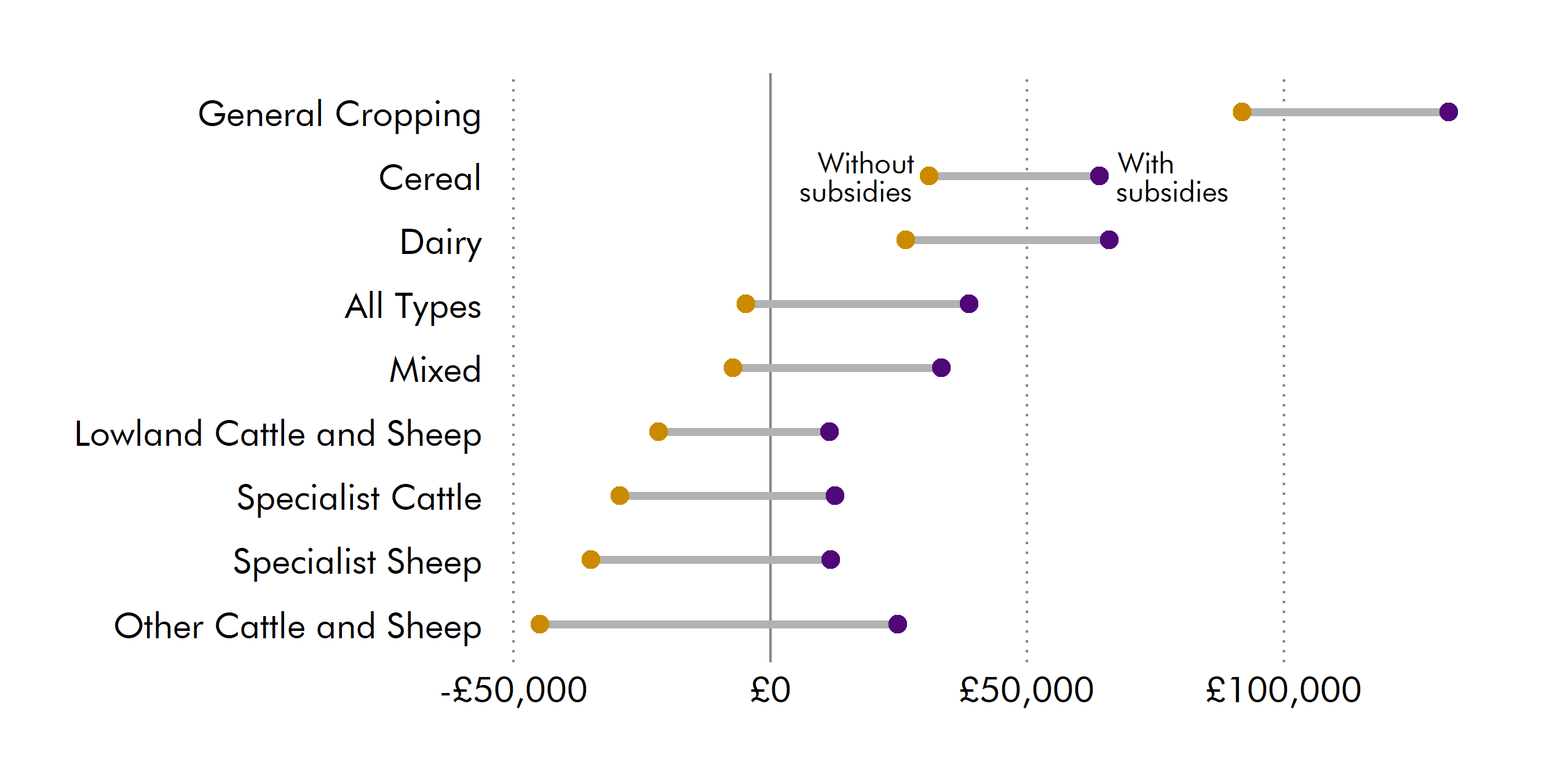

Farm Business Income (FBI) is the headline business-level measure of farm income, or profit. It represents the return to the whole farm business, that is, the total income available to all unpaid labour and their capital invested in the business. Figure 3 shows the overall impact of grants and subsidies on the average income of farm businesses11. For most farm types, as well as for the average farm in Scotland, the average FBI falls below zero when grants and subsidies are excluded. As a result, Scottish agriculture is heavily dependent on subsidies. Until the UK left the EU, the majority of these subsidies came from the EU in the form of Common Agricultural Policy payments. What might replace these payments is explored in later sections of this briefing.

Agricultural holdings also take many different forms. The majority are owner-occupied farms, but a large proportion are also made up of tenanted farms and both owner-occupied and tenanted crofts. Agricultural tenancies and crofting are explored further in the next sections, followed by a discussion of agriculture policy more generally.

Agricultural tenancies

Tenant farmers are those who rent, rather than own, their farms.

In the late 19th Century over 90% of farms in Scotland were tenanted. In 2020, however, of the total number of agricultural holdings in Scotland, 31% were tenanted. In terms of land area, approximately 22% of agricultural land was rented in 2020, having fallen 5% over the last decade.

The Land Reform Review Group offered three explanations for this trend in their 2014 final report, The Land of Scotland and the Common Good:

the break-up of large estates post WW1 following recession and the tax regime with tenants converting to owner-occupancy;

consolidation of farms into larger units e.g. due to mechanisation; and

the introduction of security of tenure in the 1940s, which has made landowners reluctant to create new tenancies since that time.

Roughly 60% of rented holdings are crofts – a specific type of land tenure unique to Scotland. This is covered more in the next section. Non-croft tenanted holdings make up the other 40%.

One function of tenancy is as a route into farming for new entrants. In 2009, research prepared for the Tenant Farming Forum explored this, outlining a staged entry into farming for new entrants as they gradually accumulate the necessary capital, experience and skills, with tenancy being a final stage. More recently, the Scottish Land Matching Service - a collaboration between the Scottish Government and farming organisations - has sought to facilitate opportunities for new entrants by matching them with established farmers and to develop collaborations such as partnerships or contracts.

Tenant farms exist where the relationship between landlord and tenant is governed by a specific body of law on “agricultural holdings”.

The main piece of legislation in this area is the Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 1991. This has been reviewed and updated in subsequent legislation. The Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 2003:

Introduced two new forms of fixed term tenancy: Limited Duration Tenancies and Short Limited Duration Tenancies.

Gave tenants greater rights to diversify.

Gave tenants a pre-emptive right to buy their farm. To exercise this right, the tenant must have registered their interest, and they then have first option if the landlord decides to sell. If the landlord and tenant cannot agree the price, an independent valuation is carried out. By 2015 only around one-fifth of tenants had registered. The requirement to register was removed by the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 ('the 2016 Act').

Gave the Scottish Land Court the main role in resolving disputes between landlord and tenant.

In November 2013 the Scottish Government initiated a review of agricultural holdings legislation. The Agricultural Holdings Legislation Review Group published its final report with recommendations on 27 January 2015. Subsequent legislative changes were later made by the 2016 Act (more on this in the next section).

Under agricultural holdings legislation there are now seven possible tenancy arrangements:

Leases of less than a year for grazing or mowing.

Short Limited Duration Tenancies (SLDT) of up to 5 years.

Limited Duration Tenancies (LDTs) of a minimum term of 10 years.

Modern Limited Duration Tenancies (MLDTs) have replaced LDTs and like them have a minimum of 10 years (an SLDT can be converted to an MLDT at any time during the lease). MLDTs were introduced by the 2016 Act and replace LDTs which were created by the Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 2003. LDTs originally had a minimum term of 15 years but this was reduced to 10 years in 2011. New LDTs cannot be entered into.

Repairing tenancies which have a minimum term of 35 years. The idea of these tenancies is that the tenant takes more responsibility for equipping the farm than they would have under an MLDT in return for a lower rent. Provisions for these tenancies were created by the 2016 Act.

“1991 Act tenancies” or “secure tenancies” entered into under the 1991 Act or preceding legislation, where the tenant’s security of tenure is protected by the legislation. A 1991 Act tenancy can be converted to an MLDT.

Limited partnership tenancies where the landlord or their agent is the limited partner, and the tenant is the general partner. The limited partnership lasts for a minimum term specified in a partnership agreement. At the end of the term specified in the partnership agreement, either the landlord or tenant can bring the partnership to an end, which ends the tenancy.

Tenancies and the 2016 Land Reform Act

The Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 included several provisions relevant for tenant farming. As part of provisions for establishing a Scottish Land Commission, the 2016 Act provided for appointing a Tenant Farming Commissioner alongside five land commissioners. The Tenant Farming Commissioner “must exercise the Commissioner’s functions with a view to encouraging good relations between landlords and tenants of agricultural holdings”.

As set out in Section 24 of the 2016 Act, the Tenant Farming Commissioner’s role is to:

prepare codes of practice on agricultural holdings

promote the codes of practice

inquire into alleged breaches of the codes of practice

prepare a report on the operation of agents of landlords and tenants within 12 months of the Act coming into force. This report was submitted to Scottish Ministers in April 2018.

prepare recommendations for a modern list of improvements to agricultural holdings

refer for the opinion of the Land Court any question of law relating to agricultural holdings

collaborate with the Land Commissioners in the exercise of their functions to where they relate to agriculture and agricultural holdings.

In addition, the 2016 Act made several changes to agricultural holdings legislation. In brief, these were:

The creation of Modern Limited Duration Tenancies and provision to convert 1991 Act tenancies or Limited Duration Tenancies into MLDTs;

The creation of Repairing Tenancies;

Removal of the requirement to register for tenant’s right to buy;

Creation of a process enabling a tenant to apply to the Scottish Land Court to order the sale of their holding where the landlord persistently fails to meet their obligations under certain circumstances;

simplifying and improving the process for triggering and carrying out a rent review for certain tenancies;

widening the categories of people to whom a tenant farmer can assign or leave their tenancy upon death;

providing for tenants to relinquish their tenancy in exchange for compensation, for instance, at retirement, or, in certain situations, to assign their tenancy to a new entrant or person progressing within farming. Regulations providing for this came into force in February 2021;

providing for an amnesty period whereby certain tenants can serve a notice on their landlord detailing improvements that have been made that they would like compensation for on departure. This was known as the ‘Waygo Amnesty’ and lasted originally for a three-year period, from 2017-2020, and was extended for six months due to the Covid-19 pandemic; and

providing a right for tenants to object to certain improvements proposed by the landlord if they are considered unnecessary.

In addition, the 2016 Act created a duty on Scottish ministers to review the legislation on small landholdings. Small landholders are tenants under the Small Landholders Acts 1911-1931. The character of these small landholdings is similar to crofts and the legislation governing them has a shared history with crofting. Once numerous, in 2014 there were an estimated 149 small landholders in Scotland, scattered from Strathspey to Stranraer. Small landholders in the areas where crofting tenure was extended in 2010 can apply to convert their holding into a croft. The Land Reform Review Group recommended that small landholders should have a right to buy their holding, as is the case for crofters and tenant farmers. A legislation review on small landholdings in Scotland was laid before the Scottish Parliament in March 2017, which contained a number of recommendations to explore the issue further.

Crofting

Crofting is part of the overall profile for agriculture described earlier in this briefing, and is covered by Scotland's agricultural policy (outlined further later in this briefing). However, crofting is a unique system of land tenure in Scotland, and therefore has additional policies and separate legislation governing it.

Crofts are small land holdings traditionally in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland, but now also in Argyll and Bute and North Ayrshire (following extension of crofting tenure to these areas in 20101). As of 2019/20 there are 21,186 crofts in Scotland, 15,137 are tenanted and 6,049 owned.2 Crofters are required to be ordinarily resident on, or within 32km of their croft, not to misuse or neglect the croft, and to cultivateit or put it to some other purposeful use.2

Many crofts are small (the average croft is around 5 hectares4), and cannot sustain the full time employment of a crofter. Crofting households spend an average of 22 hours per week on croft related activities and receive an average revenue of £13,095 for this work. However, this average reflects a small number of high earners, with over half of crofters earning £5000 or less, and a median revenue from crofting of around £2000.5

Whilst the majority of crofters are male, the number of female crofters doubled between 2014 and 2018 - from 13% to 26%.5 This is coherent with other findings from recent work on women in agriculture, which found that women have more proportionate elected representation in crofting organisations than in farming ones, and that women tend to play a larger role in decision-making on crofts. The same work also found that inheritance of a holding by a woman was more common in crofting in comparison with agriculture overall (34% compared to 24%).7

Jobs in tourism, fishing and other jobs in the rural and service sectors are important in providing an off-croft source of employment with which crofters can supplement their income. Crofting land is generally poor quality and mainly consists of rough grazing and permanent grassland with some arable land. Crofting agriculture is based primarily on rearing of store lambs and cattle for sale to lowland farmers for fattening or as breeding stock, though 42% of crofters also grow some crops. The proportion of crofters who also undertake some sort of diversification (e.g. B&B businesses, leisure activities, wood processing) has also grown since 2014.5

Crofting has been protected and regulated by a unique code of law since the end of the nineteenth century. The first crofting legislation, the Crofters Holdings (Scotland) Act 1886, followed the report of the Napier Commission in 1884 and gave crofters security of tenure, together with the right to a fair rent, the value of improvements they had made to the croft, and the right to bequeath the tenancy to a family successor. Crofts were regulated in the same manner as smallholdings in other parts of Scotland from 1912 until the Crofters (Scotland) Act 1955 restored a unique code of law to crofting.

Crofters were given the right to buy their croft by the Crofting Reform (Scotland) Act 1976, and since then around a third of crofters have become owner occupiers. Crofting law made since 1955 was consolidated in 1993 and the Crofters (Scotland) Act 1993 remains the key piece of legislation. It has since been amended by the Crofting Reform etc. Act 2007, the Crofting Reform (Scotland) Act 2010, and the Crofting (Amendment) (Scotland) Act 2013.

Crofting is regulated by the Crofting Commission, which maintains the Register of Crofts.

However, crofting law and policy remains controversial and some would argue, is in need of substantial revision.

In October 2013 the Crofting Law Sump group was established. The purpose of ‘the Sump’ was to gather together details of the significant problem areas within existing crofting legislation. Its final report was published in November 2014, and made a number of propositions for reform.

The Scottish Government set up the Crofting Legislation Stakeholder Consultation Group to consider The Sump report. This group reported to the Scottish Government that a Bill should be introduced to resolve all 57 issues identified by the Sump as requiring action. In responding to the Sump report in September 2015, the Minister at the time stated intentions to develop a programme of work, including legislation, to be brought forward in Session 5.

In 2017, the Scottish Government held a consultation on crofting policy and legislative options and priorities for a new crofting bill. An analysis of responses was published in March 2018. In April 2018, then Cabinet Secretary Fergus Ewing announced that the Scottish Government would take a 'two-phased approach' to crofting reform. The first phase was to "focus on delivering changes which carry widespread support...and result in practical everyday improvements to the lives of crofters and/or streamline procedures that crofters are required to follow".9 A Bill was planned to do this in Session 5. This would be done alongside a programme of non-legislative reform, to be set out in a National Development Plan for Crofting.

The second phase was planned for the longer-term, aiming to review crofting legislation more fundamentally. This was planned for a future Parliamentary session.

However, in October 2019, the Cabinet Secretary wrote to the Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee, informing it that due to the pressures of preparing for Brexit, work on a new crofting bill would have to be put on hold.10 As a result, a crofting bill was not brought forward in Session 5. However, a National Development Plan for Crofting was published at the end of the session.

Box 4: Opportunities for Parliamentary scrutiny in Session 6

The SNP manifesto highlighted an ambition to carry on the crofting reform process, stating an intention to “reform the law and develop crofting to create more active crofts”

The Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee carried out an inquiry into crofting reform in Session 5. In its legacy report, the Committee highlighted

"the commitments given with respect to advancing crofting reform and suggests that the progress of such reform may be a subject that is considered appropriate for ongoing scrutiny during Session 6."

National Development Plan for Crofting

A National Development Plan for Crofting was published on 18 March 2021, shortly before the end of Session 5.

The Plan highlights that crofting presents a "massive opportunity in terms of dealing with the key challenges we face with respect to tackling climate change and combating the loss of biodiversity"1 and emphasises a dual aim of keeping crofting at the heart of rural communities, and addressing environmental challenges.

It builds on work done by the Crofting Stakeholder Forum on crofting development, new entrants, common grazings, housing, financial incentives and simplifying crofting legislation, and identifies 78 specific actions from the following categories:

The Crofting Commission's role in the development of crofting; e.g. Expanding the function of the Commission beyond the regulatory to assist in crofting development, and making crofting and the Crofting Commission more accessible;

Improving the Crofting Register registration process;

Economic and community development, including actions for Highlands and Islands Enterprise to increase economic opportunities and skills development in crofting areas;

Skills development, focusing on rural jobs, green jobs and digital skills;

Local food networks and agri-tourism, developing food and drink sector opportunities for crofting;

Land, environment and biodiversity, supporting biodiversity and environmental outcomes within crofting, such as through supporting forestry on crofting land;

Wildlife management schemes to mitigate the impact of sea eagles, deer, and geese;

Housing, e.g. supporting building or improving croft houses through the Croft House Grant;

Signposting to information about crofting and encouraging information-sharing;

Farm Advisory Service, ensuring that advice is delivered to crofters;

Ensuring access to broadband;

Modernising crofting legislation;

Financial investments, e.g. Develop new schemes to support low-carbon approaches to crofting, and to assist new entrants and business development;

Changes to the Crofting Agricultural Grants Scheme, and considering other financial incentives; and

A subsidised Highlands and Islands Veterinary Scheme.

Agriculture policy

Within the rural policy sector, the question of what happens after Brexit dominated Session 5 of the Scottish Parliament. Agriculture, forestry and environmental management have been heavily influenced by EU regulations and EU financial support, in large part through the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

Having left the EU, UK nations no longer receive CAP payments from the EU, and are no longer bound by the CAP framework when designing agricultural and land use policies and subsidies. Agriculture is a devolved policy area, it is therefore up to Scotland to design a new policy.

Agriculture policy before Brexit

While a member of the EU, the UK was part of the Common Agricultural Policy. Participation in the CAP provided over £500m for Scottish agriculture, forestry, and environmental interventions per year.

The CAP is governed by an extensive set of regulations, for example around how agricultural support must be financed and run.

Within the UK context, agriculture policy is devolved, and whilst a member of the EU, the Scottish Government therefore designed and implemented a Scottish agriculture policy under the shared EU framework. As a result of the CAP, UK nations had in common with each other, and shared with the EU, the following:

A common subsidy regime. EU regulations determine the amounts that can be paid by member states, the basis for calculating payments, the schemes that must be offered to farmers and the schemes that can be offered on a voluntary basis, and so on.

A common arrangement with the World Trade Organisation (WTO) through the Agreement on Agriculture. Domestic support for agriculture (e.g. subsidies) is subject to WTO agreements which aim to ensure balanced trading arrangements between states. Domestic support is divided into three categories: Amber Box (trade distorting payments, e.g. Support linked to production for certain sectors), Blue Box (trade distorting payments that also require farmers to limit production) and Green Box (non-trade-distorting payments, e.g. agri-environment payments).1 The EU has agreed maximum levels of support that can be paid out to farmers by EU member states in the Amber Box.

A common regulatory framework. Much of the regulation governing Scottish agriculture originates from the EU. This includes environmental, animal welfare and food safety standards governed by e.g the Nitrates Directive, Birds and Habitats Directives, General Food Law, Hormones Ban Directive, directives on the protection of farmed animals, regulation on plant protection products (pesticides, herbicides and insecticides), and other regulations on public, animal and plant health.2

A common sanction mechanism in cross-compliance. In order to receive EU payments, farmers and crofters must abide by cross-compliance rules. The rules are a combination of statutory management requirements (e.g. the regulations outlined above) and standards for good agricultural and environmental conditions (e.g. good soil management). Cross-compliance adds an additional mechanism to ensure compliance with common standards; failure to meet these can result in not only legal liability, but loss of support payments.2

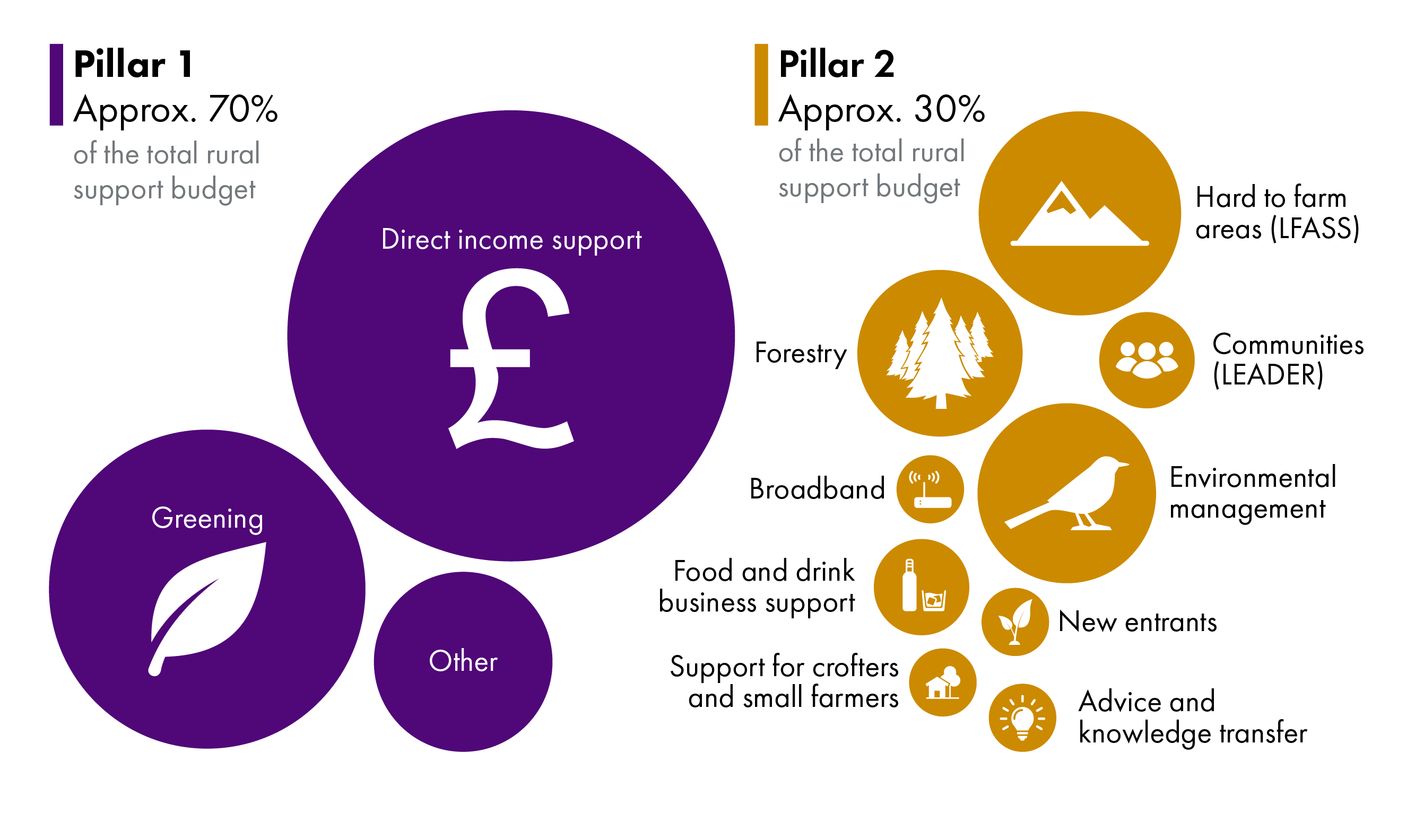

Funding under the CAP is split into two pillars. Pillar 1 provides income support for agriculture and Pillar 2 provides financial support for rural development, including community projects, environmental management, forestry, and extra support for 'less favoured areas'(LFA), where farming is more challenging due to geography and weather conditions.

Member States design their own support programmes within the constraints of the CAP framework, and submit them to the European Commission for approval. Figure 1 shows the types of support that were available in Scotland under the EU's CAP framework for the 2014-2020 programme. Most of these funding streams continue to be available in the short term. More detail on the Scottish programme and individual schemes is available from the Rural Payments and Inspections Division's website.

In the EU, the CAP is designed and run on a seven-year policy and funding cycle. The programme is reviewed and reformed at the end of each multi-annual financial framework. The most recent framework ended in 2020. As a result, the CAP is currently undergoing a reform process, which was due to start from 2021 but was delayed for two years to 2023, with transitional arrangements to carry on current rules and support programmes in the interim period. However, the UK left the CAP framework at the end of the Brexit Implementation Period on 31 December 2020 and is so not participating in the reform process.

Agriculture policy after Brexit: A new policy for Scotland

Post-Brexit, UK nations are no longer required to follow CAP rules nor do they receive CAP support payments from the EU. Payments to UK farmers are now provided by the UK Treasury. Agriculture is a devolved policy area, therefore Scotland can decide on a new policy for Scottish farmers and crofters.

The Scottish Government’s approach has centered around a period of ‘stability and simplicity’ – a transition where existing rules and funding programmes are largely maintained in the short term but simplified where feasible. A consultation held in 2018 set out proposals for this period of little change to 20241, whilst a new policy is being developed to be rolled out from 2025. Existing schemes can be explored in more detail on the Scottish Government Rural Payments and Inspections Division's website.

During this transition period, the same rules that applied under CAP largely continue to apply in Scotland, as they have been ‘retained’ - in essence, copied over - as part of a new category of law called ‘retained EU law’. Retained EU law can be thought of as a snapshot of the EU law which was in place in the UK at 11pm on 31 December 2020. That was the time at which EU law ceased to apply in the UK. Retained EU law was created so that there was no gap in the law which applied in the UK immediately prior to and immediately after EU law stopped applying.

Some parts of retained EU law needed to be changed to ensure the law was clear and could work properly in domestic law (by “domestic law” we mean the law in the UK or in a part of the UK). For example, by removing references to the UK being a Member State, removing references to “euros” or replacing a reference to an EU institution with a reference to a UK or Scottish institution. This exercise of changing retained EU law to make sure that it worked properly in domestic law is known as deficiency correction.

Agriculture and related areas such as plant and animal health, animal welfare, food standards and the environment were areas in which a significant deficiency correcting exercise was undertaken. This is because so much of the legislation in these areas stemmed from EU law. This was done both through Scottish Statutory Instruments at a Scottish level, and through UK Statutory Instruments where changes were made on Scotland's behalf by the UK with Scottish Ministers' consent. This comprised a significant area of work for Parliamentary committees in Session 5.

These retained EU laws remain the law in Scotland unless the Scottish Parliament decides to pass a new law to change them. New legislation – the Agriculture (Retained EU Law and Data) (Scotland) Act 2020('the 2020 Act')– has provided Scottish Ministers with the power to, by regulation, simplify and improve the operation of the retained CAP rules in Scotland. This power is available to ministers until 2026, at which time it is expected that new arrangements will be in place. The Scottish Government used these powers to, for example, make changes to the 'greening' rules, to shorten the required length of land-management contracts under agri-environment and organic schemes, and to amend the penalties for overclaiming certain subsidies.

Under Section 22 of the 2020 Act, Scottish Ministers must lay a report before the Scottish Parliament on progress towards establishing a new Scottish agricultural policy. The report must include policies and proposals regarding:

the sustainability of agriculture and resilience to climate change,

the simplicity of future agricultural schemes,

the profitability of Scottish agriculture and the agri-food supply chain,

the support given to innovation and good practice,

the inclusion of new entrants, and

the improvement of productivity in Scottish agriculture

It must also include an outline of any legislation that will be required and a timeline of when this will be introduced, as well as details of any consultation. This report must be laid before Parliament by 31 December 2024.

Calls for longer-term reform of land use policy in Scotland are many and varied. Stakeholders have identified a need for a future land use policy to, e.g. Better consider land uses holistically, as opposed to siloing agriculture, forestry and other sectors2; better support innovation and productivity improvements3; drive down agricultural emissions and ensure support for biodiversity45; and better support small units and those in geographically constrained areas4.

As a result, many stakeholder proposals have been published since the Brexit referendum (including from the Scottish Wildlife Trust, the National Farmers Union for Scotland, Scottish Environment LINK, and Scottish Land & Estates), in addition to research, and pilots (e.g. trialling an ‘outcome-based approach’ to delivering environmental benefits from land management). The Scottish Government also convened several groups which made recommendations, including:

Four Agriculture Champions;

Sectoral groups focused on policy solutions to climate change (on suckler beef, dairy, hill, upland and crofting, pig industry, and arable sectors).

There is not yet any significant clarity on the shape of a new agricultural policy. However, outcomes in several policy areas depend on a new rural policy.

Climate change: the Scottish Government declared a climate emergency in Session 5; as a result, climate change and the environment have become a key driver for changes to Scottish land use policies. As part of the Scottish Government’s most recent update to its climate change plan, it committed to, among other things, scaling up activities such as the 'Agriculture Transformation Programme' and advisory services, to introducing environmental conditions on receiving agricultural payments, and a new rural support policy to deliver “a more productive, sustainable agriculture sector that significantly contributes towards delivering Scotland’s climate change, and wider environmental outcomes”. In October 2020, the UK Committee on Climate Change recommended that the Scottish Government “set out new recommendations for Scotland's future rural support policy, and make provisions for Ministers to create new policy or reform existing policy. Policy to reduce emissions on farms and increase land-based sequestration should also deliver co-benefits for wider environmental goals.”7 The advice on climate change and agriculture and Scottish Government commitments in relation to agriculture are discussed further in the SPICe briefing on the Climate Change Plan update.

Biodiversity: agriculture and other land uses remain key pressures on biodiversity.At an EU-wide level elements of the CAP are found to have inadequately protected biodiversity and underfunded environmental interventions, but farmers and crofters, and agricultural policies and support are also key to approaches to halt and reverse biodiversity decline. The Scottish Government’s statement of intent on the Post-2020 Scottish Biodiversity Strategystates: “We are already working in partnership to develop new rural support measures that result in transition to a sustainable sector that more directly and explicitly supports our climate and environmental ambitions.”

Strategic land use: Many demands are placed on land, resulting in both a national Land Use Strategy (which is currently in its third iteration) and proposals for Regional Land Use Partnerships aiming to maximise the benefits from land. Mechanisms under a new rural policy will influence how this is achieved.

Land reform: Recent work by the Scottish Land Commission on scale and concentration of ownership noted that the “fiscal environment surrounding agriculture, forestry, and renewable energy in particular appears to incentivise behaviour that is sometimes contrary to Scotland’s land reform objectives” and recommended that relevant fiscal incentives should be reviewed to ensure consistency with the “policy objectives of community empowerment, rural development, and land reform”. A SPICe blog provides more information on land reform policy in Scotland since the Parliament was established.

Food and Drink: Scotland has a target to double the value of its food and drink industry by 2030. Meanwhile, industry has been affected by both Brexit and the Covid-19 pandemic, prompting the publication of an industry recovery plan, which includes discussions of resilience within food production sectors. It also links to Scotland’s overall food policy; any future rural policy will be key to Scotland’s food policy from farm to fork, and ambitions to become a 'Good Food Nation'.

Resilience of rural communities: The extent of support for, e.g. new entrants to farming and crofting, to crofting communities, and to support women in agriculture through a new rural policy can have a wider impact on resilience in rural communities and diversity in the agricultural sector. Moreover, policies to support rural sectors indirectly, including through advisory services, support for collaboration between land managers, and considering the wider supply chain can play a role in resilience.

As noted above, the Common Agricultural Policy is underpinned by an extensive framework of EU regulations. A new law - the Agriculture (Retained EU Law and Data) (Scotland) Act 2020 - was required to give Scottish Ministers the power to deviate from this framework in limited ways. Further legislation is likely to be required to underpin a whole new Scottish agricultural policy.8

Box 5: Opportunities for Parliamentary scrutiny in Session 6

New primary legislation to make provision for a post-CAP land use policy.

The annual report on Scotland's climate change plan will report against commitments to deliver a new agricultural policy which supports emissions reduction.

The UK internal market and the EU

While there are many views on the shape of a future land use policy, several factors may interact with, or constrain, its development.

When the UK was in the EU, each UK nation developed its own agricultural policy within the framework of the EU's Common Agricultural Policy. This ensured a common regulatory baseline on environment, animal welfare and food safety issues. In addition, while there was some variation to account for regional differences, the levels and types of support available to land managers in each nation was broadly similar.

As a result, land managers across the UK - and EU - operated on a level playing field. No farmer had a competitive advantage due to less stringent environmental or animal welfare requirements, nor was anyone able to undercut other land managers in the EU due to excessive subsidy.

However, having left the EU, this framework and common set of rules and baselines is no longer automatically applied. And with policy areas like agriculture, forestry and the environment being devolved, this opens up for the possibility of regulatory and policy divergence between the UK and the EU, but also between the four UK nations.

Scotland, England, Wales and Northern Ireland have been developing new rural policies separately. Scotland's transitional plans are discussed in an earlier section of this briefing. For England, the Agriculture Act 2020 led to the development of new ‘Environmental Land Management Schemes’ as the basis for its post-CAP policy. The new approach focuses on the principle of ‘public money for public goods’ – supporting farmers to deliver environmental and animal health and welfare benefits – alongside support to improve productivity, a new approach to regulation, and ultimately phasing out direct income support and existing CAP schemes between 2021 and 2027.

In Wales, a consultation on a new legislative framework for land use proposed the replacement of existing schemes with a new payment scheme on sustainable farming practices, with wider support for supply chain and agri-food development. On 6 July 2021, the Welsh Government announced that it would bring forward a new agriculture bill for Wales “ to create a new system of farm support that will maximise the protective power of nature through farming.” In Northern Ireland, a consultation on a future agricultural policy was published on 7 July 2021.

What happens across the UK may impact the development of Scotland’s rural policy. The UK Internal Market Act 2020, discussed in the following section, may affect Scotland's policy choices. Evolving ‘common frameworks’ – e.g. on Agricultural Support– coordinating policy approaches across the UK may also influence outcomes. Developments in the EU, in the evolving relationship between the UK and the EU, and in Scotland's relationship with the EU and UK may also have an impact.

A SPICe blog explores the impact of these multiple factors on policymaking in a devolved context using pesticide regulation as an example.

Trade and agriculture

On leaving the EU, the UK also left the EU's single market.

When the UK was a member of the EU, agricultural producers had access to frictionless and tariff-free trade with the EU as a result of a shared policy framework for agriculture as well as common rules and standards.

In addition, the UK was covered by trade agreements between the EU and third countries, and did not have bilateral agreements with non-EU countries on its own. Having left the EU, the UK may strike Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with other countries, but is no longer covered by the arrangements that that country has with the EU.

Food and drink is Scotland's largest export sector (in large part due to whisky exports); with a large proportion traded with the EU1. This is particularly important in certain sectors: 81.7% of UK beef exports went to EU countries in 2018; likewise 94.1% of UK sheep meat exports went to EU countries in 2019.2 Post-Brexit trade arrangements with the EU and with other countries has therefore been a matter of significant importance for the agriculture sector.

Trade policy is reserved to the UK Government, and there is therefore no formal role for the Scottish Government in trade negotiations with third countries. However, the Scottish Government has sought more formal involvement in these processes, arguing that trade policy impacts on areas of devolved competence. In its most recent vision for trade, the Scottish Government stated:

Responsibility for the regulation of international trade is reserved to the UK Parliament and Government, but the broad and increasing scope of modern trade agreements means that they often deal with, and merge, a range of reserved and devolved policy areas. International trade profoundly affects devolved policy areas and a wide range of non-devolved issues that affect the day-to-day lives of people in Scotland. The Scottish Government is also responsible for observing and implementing international obligations in devolved areas and these include some of the most contentious areas of trade such as agriculture and food standards. The UK Government should seek our agreement on priorities and the pursuit of its trade policy, as it can dramatically affect devolved policies, such as food standards. In current circumstances, and now that the direction of travel of the UK Government is clear, the Scottish Government’s call for a comprehensive, formal role for devolved administrations and legislatures is even more important. This relationship needs good governance in line with our trade principles.3

With the EU, trading arrangements were settled with the ratification of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement, which established that there are zero tariffs and zero quotas on the trade of goods between the UK and the EU. This was good news for many Scottish producers, as it meant that Scottish produce would not have tariffs imposed that would make them more expensive, and therefore less competitive, at the point of sale in the EU.

However, the deal did not include an agreement on regulatory alignment on food standards. As a result, non-tariff barriers such as extra paperwork (e.g. Export health certificates and other documentation) have resulted in trade difficulties and reduced trade volumes at the start of 2021. These recovered somewhat in the following months4, but some UK-wide industry stakeholders estimate that there will continue to be a long-term impact.

Box 9: Opportunities for Scrutiny in Session 6 - RECC legacy report

The Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee took evidence in February 2021 from stakeholders regarding the ongoing impact of new post-Brexit requirements for exports in Scotland’s agriculture, fisheries and aquaculture sectors. In the Committee's Session 5 legacy report it concluded:

"The evidence the Committee took from stakeholders indicates that some of the difficulties currently being experienced are likely to continue for the foreseeable future and the Committee’s successor/s may wish to consider ongoing work to assess the impact these are having on Scottish exporters and Government action and the provision of Government support to address them."

Moreover, the Committee also noted the "important role for the Scottish Parliament and its Committees in scrutinising the negotiation of international trade agreements, notably as these relate to areas falling within the Committee’s remit such as agriculture, fisheries and the wider food and drink sector in Scotland. The Committee suggests that its successor committee/s may wish to consider how best to ensure ongoing and effective scrutiny in these areas during the course of Session 6."

Scottish farmers and crofters are generally thought to be high-quality and high-cost producers5, and the average livestock farm in the UK is small compared to farms in other countries. In a scenario where tariffs and quotas are not applied, this means that it may be difficult for Scottish and UK producers to compete with lower-cost, higher-volume producers in other countries.5 The cost of production may be lower elsewhere if, for example, environmental requirements are lower, or it is common to have larger-scale operations.

Furthermore, concerns for UK food standards as a result of trade deals have been voiced by both producers and consumers. Several consumer surveys have shown high support for maintaining food standards. James Withers, Chief Executive of Scotland Food and Drink told Session 5’s Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee in September 2019 that

It will be important, as we go into wider trade deals, that we do not use them to lower our standards…It is important that we do not take an opportunity to unpick the regulatory framework. To some extent, the industry is never a fan of regulation: people round this table will frequently complain about levels of regulation, but the reality is that regulation underpins our brand. We do not want to gold plate regulation, but we want to maintain our world class standards of food protection.7

In Scotland’s food and drink industry growth strategy – Ambition 2030 – high-quality production in terms of environmental and animal welfare standards is seen as key to Scotland’s brand8.

Likewise, environmental organisations have expressed concerns about the environmental outcomes from lowering or undermining domestic standards9, and the risk of “exporting” environmental impacts abroad has also been raised. A reduction in standards is therefore often seen as counterproductive economically, as well as contrary to plans to address climate and environmental challenges.

The Scottish Government commissioned a study on the impact of Brexit scenarios on agricultural sectors. Whilst this was concluded prior to an agreement being reached with the EU and examined EU-UK trade scenarios in the main, the authors also highlighted the following with regard to FTAs with non-EU countries:

FTAs with third countries or generous new TRQs [Tariff rate quotas*] will erode output gains: although this study did not specifically model the impact additional FTAs which the UK might agree with other non-EU countries, it is evident that any additional exposure to global competitors whose cost bases are lower and operate to different standards, will exert pressure on Scottish producers. Importantly, it was also assumed that the UK's existing standards (i.e. aligned with the EU's) were still in place. As such, there were still linkages with the EU market. Changed standards as a result of new FTAs would mean greater exposure to world market prices and an erosion of domestic prices, lowering output considerably. This would be most prevalent in beef but likely to have some effects on dairy products as well. Furthermore, if the UK introduces generous new TRQs (i.e. of a quantity greater than the UK's net imports with the EU), then Scottish producers will face greater competition from world markets and domestic output would reduce significantly as a result.5

*Tariff-rate quotas are a fixed volume of a product which can be imported at a lower tariff rate. Once that volume has been imported, any additional imports are charged at a higher tariff rate. The Scottish Farm Advisory Service provides a helpful explainer.

As a result of these concerns, during the passage of both the UK Agriculture Bill and the UK Trade Bill (both now Acts) MPs attempted to amend the legislation to require imported products to conform to UK standards.

These attempts were not successful; however, in response to concerns from farmers, environmental organisations and the public, the UK Government set up a non-statutory Trade and Agriculture Commission in July 2020. It was set up to advise the government on trade policies to ensure that UK agriculture remains competitive, and that environment and animal welfare standards are not undermined. The Commission was initially launched for a six-month period to report on trade and agriculture issues.

However, the Commission was put on a stronger footing in November 2020 in the final stages of passing the Agriculture Act 2020 and the Trade Act 2021. The Agriculture Bill was amended to require the Secretary of State to report to the UK Parliament on “whether, or to what extent” future free trade agreements

“are consistent with the maintenance of UK levels of statutory protection in relation to—

(a) human, animal or plant life or health,

(b) animal welfare, and

(c) the environment.”

At the same time, the Trade and Agriculture Commission was given a statutory role in providing advice on free trade agreements to the Secretary of State in the Trade Act. The Secretary of State must seek the advice of the Commission before producing such a report for Parliament under the Agriculture Act.

To date, the UK has struck free trade agreements with several countries, including Japan and Australia. The latter was seen as the first trade agreement which went beyond the agreement that the UK had been covered by as an EU member state. Provisions for import of agricultural products from Australia were met with concern from both the Scottish Government, and the NFUS due to the possibility that imported food products from Australia could undercut Scottish producers. The discussion around the UK-Australia trade negotiation is covered in greater detail in a SPICe blog post.

Forestry

What does Scottish forestry look like?

The Scottish Forestry Strategy 2019-2029 states that:

The forestry and timber sector comprises tree nurseries and businesses focused on planting, managing and harvesting forests and woodlands, as well as wood processors producing a range of wood products, including sawn timber, composite boards, paper, pallets, biomass and bark. Businesses range in scale from artisan furniture-makers, family-owned contracting micro-businesses and community-based biomass enterprises, to UK-wide woodland management companies and multi-million pound panel, pulp, paper and sawmills operating internationally.1

Forests make up 19% of Scotland's land area.2 This is just under half of the UK’s forests and woodlands, and above the UK average coverage of 13%, but below the average of 42% among EU countries. Scotland has a goal of increasing woodland coverage to 21% by 2032 as part of commitments on climate change.3 To do so, there are commitments to plant 12,000 hectares per year in 2021/22, increasing to 18,000 hectares per year by 2024/25.

There are no strict technical differences between the definition of 'forests' and 'woodlands'. These terms are often used interchangeably. However, the terms 'forestry' and 'forest' are often -but not always - used to refer to commercial tree growing, whilst 'woodland' is often - but again, not always - associated with trees that are managed for recreational or environmental purposes. 'Forests' are also often used to refer to larger tree-covered areas, and 'woodland' to smaller pockets of trees within the landscape.4

Approximately 32% of Scotland’s forest area is publicly owned, for example by Forest and Land Scotland (the Scottish Government agency responsible for managing the national forest estate), and the remainder is privately owned. A more detailed profile of woodland ownership can be found in a 2021 Scottish Government publication.

74% of Scotland’s wooded area is made up of conifers, and 26% is made up of broadleaved species. This is compared with 49% and 54% conifers in Wales and Northern Ireland respectively, and 26% conifers in England.2

In Scotland, 58% of the stocked area of conifers is made up of fast-growing, non-native Sitka spruce. Many of Scotland’s forests are for productive use and produce timber.

The area of Scottish native woodland (woodland where over 50% of the canopy is composed of native species such as birch, rowan, hazel, oak, scots pine, juniper, alder, willow, and ash) amounts to 32% of the total woodland area. This is less than the 49% of woodland across the whole of the UK classed as native; in England 62% is made up of native species, followed by 48% in Wales. The Scottish Government has three targets to be met by 2020, set as part of its biodiversity policies, to:

create 3,000-5,000 hectares of new native woodland per year;

increase the amount of native woodland in good condition; and

restore approximately 10 000 ha of new native woodlands into satisfactory condition in partnership with private woodlands owners through Deer Management Plans.

According to the most recent Scottish Government progress report to Parliament on the 2020 Route Map for Biodiversity (published in 2019 and covering the period 2017-2019), the native woodland creation targets were met in 2017/18 and 2018/19, but while progress is being made when it comes to increasing the amount of native woodland in good condition and restoring 10,000 hectares of native woodlands, it was insufficient to meet the targets by 2020. Some of Scotland’s native woodlands are classed as ‘ancient’ woodlands – woods that have been wooded since at least 1750. They are important because of their rich flora and fauna - and because they have evolved over many centuries, they cannot be recreated if destroyed.6

Woodland on farms has increased by 32% since 2010. Integrating forestry and farming is one of the Scottish Government’s commitments as part of the updated Climate Change Plan, aiming to “boost our work on forestry and farming and develop models to increase woodland creation on both tenanted and owner-occupied farms, increasing the scale and scope of agro-forestry”.

More forestry statistics can be found in Forest Research’s annual publication updated each September.

A 2015 report on the Economic Contribution of Forestry in Scotland found that economic contributions of the sector had increased by 30% between 2008 and 2012/13. Approximately 80% of the economic contribution is attributed to forestry and timber processing, and the remaining 20% to recreation and tourism. In terms of employment, there were over 25,000 full-time equivalent staff working in the sector as of 2015.

Forest policy and governance

Forestry has long been a devolved matter, though its governance has changed in recent years. Until 2018, Forestry Commission Scotland (FCS) was the forestry agency of the Scottish Government, but was linked to its counterparts in England and Wales. The organisations were all accountable to a single set of Forestry Commissioners. However, following similar legislative changes in Wales in 2013, this changed for Scotland with the passage of the Forestry and Land Management (Scotland) Act 2018 (the 2018 Act). Following the 2018 Act, the powers and duties held by the Commissioners were transferred to Scottish Ministers (where they relate to Scotland). Two new organisations were established to replace FCS: Forestry and Land Scotland, and Scottish Forestry. Forest and Land Scotland’s role is to manage the Scottish forest estate; Scottish Forestry is responsible for forestry policy, regulation and grant payments.

A memorandum of understanding (MoU) between Scotland, Wales and England has divided up shared areas of responsibility. Scotland has responsibility for the UK Forest Standard and the Woodland Carbon Code (more on this below), as well as forestry economics, whilst Wales is responsible for coordinating the programme of forest research, and England is responsible for international forestry policy and certain forestry plant health functions.

Scottish Forestry published a new ten-year Scottish Forestry Strategy in February 2019. The strategy includes a fifty-year vision for Scottish forestry:

In 2070, Scotland will have more forests and woodlands, sustainably managed and better integrated with other land uses. These will provide a more resilient, adaptable resource, with greater natural capital value, that supports a strong economy, a thriving environment, and healthy and flourishing communities.

It also includes three objectives:

Increase the contribution of forests and woodlands to Scotland’s sustainable and inclusive economic growth;

Improve the resilience of Scotland’s forests and woodlands and increase their contribution to a healthy and high quality environment;

Increase the use of Scotland’s forest and woodland resources to enable more people to improve their health, well-being and life chances;

And six priorities:

Ensuring forests and woodlands are sustainably managed

Expanding the area of forests and woodlands, recognising wider land-use objectives

Improving efficiency and productivity, and developing markets

Increasing the adaptability and resilience of forests and woodlands

Enhancing the environmental benefits provided by forests and woodlands

Engaging more people, communities and businesses in the creation, management and use of forests and woodlands

In addition, a two-year implementation plan was published in 2020, prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. Whilst the implementation plan is still in force, it is being used alongside a recovery plan for the forestry sector.

Box 10: Opportunities for parliamentary scrutiny in Session 6

Under the Forestry and Land (Scotland) Act 2018, Scottish Ministers have a duty to report to the Scottish Parliament on the delivery of the Scottish Forestry Strategy every three years. The first of these reports is due in 2022.

Forestry grants

Scottish Forestry manages a programme of grants for woodland creation and management. These are part of the Scottish Rural Development Programme, which was part-funded by the EU until 2021. Following the UK’s exit from the EU, forestry grants must now be funded entirely from domestic sources. As discussed previously in relation to agriculture, no long-term decisions on the future of rural policies have yet been made for Scotland. In the short-term, funding programmes are largely being carried over, and funding has been provided from the UK Treasury for the remainder of this UK Parliament.

In addition to grants, forestry receives other financial benefits. There is no income and corporation tax on income from timber sales, in the UK, nor capital gains tax on growing timber. In addition, there is 100% business property relief from inheritance tax on commercial woodlands after two years of ownership.12 These tax arrangements are reserved to the UK Government.

Industry standards

In light of the role of forestry and forest management in sustainable land use, several industry standards and accreditation schemes have been established.

The most mainstream is the UK Forestry Standard (UKFS), which defines requirements and produces guidelines for sustainable forest management developed by the forest agencies of the UK and devolved governments. Forestry grant recipients are expected to adhere to UKFS requirements. The UKFS is reviewed and updated every three years; the next update is due in 2022.

The UKFS is divided into legal forestry requirements – i.e. those set out in law - and good forestry practice requirements. The latter are linked to international commitments and are required for grant payment. The requirements are complemented by guidelines.

A second standard exists in the form of the UK Woodland Assurance Standard (UKWAS). This is a voluntary certification standard, and draws on the UKFS as the basis for best practice and combines with the requirements from two certification schemes; the Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) and Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC). UKWAS is independent of government and acts as an audit for the independent certification schemes, paid for by the forest or woodland owner. Promotion of UKWAS certification is one of the actions identified in the 2020-2022 Implementation Plan to deliver the forestry priority on sustainable management. The proportion of Scottish woodlands that are UKWAS certified is also a monitoring indicator for the Implementation Plan.

Finally, the Woodland Carbon Code is the quality assurance standard which generates carbon credits for woodland creation.

According to the Woodland Carbon Code:

Validation / verification to the code means that woodland carbon projects:

are responsibly and sustainably managed to national standards;

can provide reliable estimates of the amount of carbon that will be sequestered or locked up as a result of the tree planting;

must be publicly registered and independently verified;

meet transparent criteria and standards to ensure that real carbon benefits are delivered.1

The Code also plays a role in Scottish climate change plans. As part of forestry commitments, the Scottish Government has committed to

further develop and promote the Woodland Carbon Code in partnership with the forestry sector, and will work with investors, carbon buyers, landowners and market intermediaries to attract additional investment into woodland creation projects and increase the woodland carbon market by 50% by 2025.2

Timber production

Timber has a large number of uses and the timber industry comprises a variety of enterprises, from wood production and forest management to haulage and timber processing. Scotland’s timber output is largely made up of softwood produced from Scotland’s conifer plantations – 94% of Scotland’s timber production was softwood in 20171.

Currently, the UK imports 60% of its timber from overseas.1 Interest in timber as a building material is growing in response to climate change, due to its potential to replace higher-carbon alternatives.

In the Climate Change Plan Update, the Scottish Government committed to

increase the use of sustainably sourced wood fibre to reduce emissions by encouraging the construction industry to increase its use of wood products where appropriate.3

Forestry and the environment

Trees absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Forests are therefore known as ‘carbon sinks’, meaning that they remove carbon from the atmosphere and store it.

Forestry planting is a major pillar of the Scottish Government climate change strategy, with a target to increase woodland creation to 18,000 hectares per year by 2024/25.

However, forests and woodlands, depending on how they are created and managed, can provide additional benefits and contribute to climate change mitigation in different ways. A recent SPICe briefing - the Multiple Roles of Scottish Woodlands - highlights the complexity of woodland creation and management, with "suitability dependent on a number of social, ecological and economic factors". The location of the planted trees - and what existing habitats and landscapes any new woodlands replace - determines both the climate change mitigation value and the benefit for biodiversity. For example, one study from Stirling University and the James Hutton Institute found that planting trees on heather moorlands with organic and peaty soils in Scotland did not lead to an increase in net ecosystem carbon stock from 12 to 39 years after planting1. The same is also true for how the forest is structured and managed.

Beyond carbon storage, Scottish woodlands also play a role as habitat for a wide variety of species, and in ecosystem services on water supply and regulation and biodiversity. In recognition of this interconnectedness, Scotland's Environment Strategy, published in February 2020, highlights that "the climate and nature crises are intrinsically linked" and that "creating and restoring natural habitats can benefit biodiversity" as well as mitigating climate change.

Environmental challenges such as climate change can also affect forests and woodlands. For example, changes to temperatures, rainfall and weather patterns can affect the prevalence and susceptibility of trees to pests and diseases2.

Forests and people

Forests and woodlands are important areas for recreation and attract visitors and tourists. An assessment of the economic importance of Scottish Forestry in 2015 estimated that forest recreation and tourism employs more than 6,000 people in Scotland. Forests and woodlands are the second most-visited type of outdoor space in Scotland. Scotland’s People and Nature Survey reported that “around a fifth of visits [to the outdoors] included a forest or woodland destination (19%), equating to an estimated 123.4 million visits over the 11 months from May 2019 to March 2020.”

Community-run or -owned woodlands are also an important type of woodland for people. There are over 200 community woodlands groups in Scotland who own or manage woodlands of various sizes for the purpose of recreation, supporting nature, economic or commercial reasons, renewable energy, or social inclusion.1

Hunting and wildlife management

Use of land for hunting is common in Scotland, targeting for example deer, grouse, pheasant or fox. In addition, hunting for certain protected species can take place under license. Hunting occurs both as a commercial event, such as on a sporting estate, or to control population numbers where these are considered problematic.

Deer management

There are four species of wild deer established in Scotland: two native species, roe deer and red deer; and two introduced species, sika and fallow deer.

Overall deer numbers have increased substantially over the last 50 years1, and in the absence of natural predators it is considered that deer numbers need to be managed to protect other public interests. Deer can cause extensive damage and conflict with land-management interests by overgrazing and trampling vulnerable habitats and preventing young trees from growing. Deer management raises issues in relation to animal welfare, biodiversity and climate change.

It is difficult to accurately determine deer populations. An estimate of 750,000 deer from all four species has been frequently cited, though, more recently, it has been suggested that the overall population is approaching one million deer (this is compared to 1.8 million cattle, and 6.6 million sheep). Red deer make up the largest group1.

However, whilst national estimates are considered valuable, experts recommend focusing on the impacts of deer at different scales, rather than absolute numbers1.

Most wild deer populations are subject to some degree of management. This takes two forms, hunting or “stalking” by shooting, or fencing, either to keep deer in or out. Male deer are prized as sporting quarry, and their stalking is often let out commercially. Deer fencing is used widely to protect forestry, woodland, farm and croft land and other vulnerable habitats.

Under the Deer (Scotland) Act 1996, NatureScot (formerly Scottish Natural Heritage) is responsible for securing the conservation and sustainable management of deer in Scotland. The 1996 Act also sets close seasons (a period in each year during which no person can kill deer) for male and female deer of each species. Where deer are impacting on agriculture, forestry, the natural heritage or other public interests, Section 7 of the Act provides a mechanism for NatureScot to negotiate a (voluntary) control agreement with landowners, which would aim to reduce the impact of deer. Section 8 of the Act also provides backstop powers for NatureScot to implement a (compulsory) control scheme, including for NatureScot to carry out deer control, and recover costs. Section 8 powers have never been used.

Deer Management Groups have been formed over several decades to coordinate deer management between neighbouring landowners, initially covering the open hill range of red deer, but increasingly extending their geographic coverage to include lowland areas where all four deer species can be found. Since the 1960s, these groups have formed voluntarily, encouraged by the deer authority of the time, and since 1992, they have been represented collectively by the Association of Deer Management Groups. The purpose of the groups is to collaborate across a local area, and they are encouraged to produce deer management plans.

Changes to deer management policy and legislation have been made in successive stages over the past few decades, with the aim of securing sustainable deer management which limits deer impacts:

Changes to governance arrangements took place in the 1990s and 2000s, which ultimately resulted in NatureScot assuming responsibility for deer management in 2010.

Part 3 of the Wildlife and Natural Environment (Scotland) Act 2011 made amendments to the 1996 Act. It required NatureScot to draw up a code of conduct on sustainable deer management, and provides powers for NatureScot to introduce a competence test for deer hunters by regulation, if the voluntary approach to securing this does not work.