Environment: Subject Profile

This briefing provides an overview of environmental policy and governance in Scotland - including information on key legislation, responsibilities and forthcoming areas of policy development across different subject areas. It is designed to provide Members of the Scottish Parliament with a broad overview of environmental policy and regulation at the beginning of session 6.

Introduction

What is our environment?

Scotland's environment is a combination of people, place and nature. People depend on the environment - for clean air, water, a climate that supports life and health. We use the environment and its resources such as food, timber, water. We also co-exist with, are part of, and are inter-dependent on its biodiversity, natural ecosystems and species. How our interaction with the environment is regulated, through our laws, culture, practices and lifestyles -impacts on our health, the health of economies, and our ability to sustain ourselves as a species.

What is devolved?

Environmental policy in Scotland is mainly a devolved area. This encompasses multiple areas of policy and regulation including:

Climate change mitigation and adaptation (see the SPICe Climate Change Subject Profile)

Air quality

Nature conservation and biodiversity - on land and at sea

Waste management and the circular economy

The water environment and flooding

The use of chemicals, biocides and pesticides

Environmental governance including areas such as how environmental principles underpin our law and decision-making, how regulation is enforced, and how we exercise environmental 'rights' such as access to environmental information and environmental justice

The quality of our environment, and the impact of human-interactions on biodiversity, are also heavily influenced by and interact with other devolved policy areas such as agriculture and fisheries policy, transport, planning, development and infrastructure, food, and devolved areas of economic and fiscal policy. How we use our environment to support our wellbeing can also influence outcomes in further devolved policy areas such as health and education.

Interaction with reserved areas

Devolved responsibility for environmental regulation can also interact and intersect with reserved areas such as import and export control, product standards, health and safety, and energy. In some areas this can result in coordinated UK-wide approaches, for example in areas such as chemicals regulation and some aspects of waste regulation, which can also facilitate the UK internal market. Other reserved areas can also strongly influence environmental outcomes in Scotland, or impact on how consumption in Scotland affects the global environment - such as trade policy, energy policy, and economic and fiscal decisions that impact on environmental outcomes.

Key strategic policies and goals

Scotland’s Environment Strategy

The Scottish Government published 'The Environment Strategy for Scotland: Vision and Outcomes' in 2020 with a view to providing an overarching framework for achieving our environmental goals and tackling climate change. The Strategy sits alongside other high-level Government strategies such as Scotland’s Economic Strategy. The vision for Scotland's environment set out in the Strategy is:

One Earth. One home. One shared future. By 2045: By restoring nature and ending Scotland’s contribution to climate change, our country is transformed for the better - helping to secure the wellbeing of our people and planet for generations to come.

The Strategy recognises that the natural environment contributes to health and wellbeing in numerous ways, including through the provision of clean air and water, supporting food production, storing carbon, and protecting communities from flooding and extreme weather. Such 'services' that people derive from healthy ecosystems and habitats are often described as 'ecosystem services'.

The Strategy also recognises the inter-dependence of a healthy environment and healthy economies, given the environment supports the productivity of many sectors. With that in mind, the Strategy refers to the Scottish Government's pursuit of a 'wellbeing economy', which values the wellbeing of people and planet as measures of success, not just growth in Gross Domestic Product.

The Strategy refers to the need for significant action to restore natural systems, for Scotland's regulatory framework to be robust and to foster resilience. It also states that working towards this vision will help to deliver many of the National Outcomes in the National Performance Framework and support Scotland's contribution to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (see further below).

The six Outcomes identified in the Strategy are:

Scotland’s nature is protected and restored with flourishing biodiversity and clean and healthy air, water, seas and soils

We play our full role in tackling the global climate emergency and limiting temperature rise to 1.5oC

Our thriving sustainable economy conserves and grows our natural assets

Our healthy environment supports a fairer, healthier, more inclusive society

We are responsible global citizens with a sustainable international footprint

We use and re-use resources wisely and have ended the throw-away culture

The UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2021 went on to enshrine the requirement for a national 'Environmental policy strategy' in law. Scottish Ministers are required, under this Act, to publish an environmental policy strategy which sets out objectives for protecting and improving the environment, policies and proposals for achieving the objectives (or a summary of these); and arrangements for monitoring progress.

In preparing the Strategy, Scottish Ministers must have regard to the desirability of securing that environmental policy:

aims at a high level of environmental protection,

contributes to sustainable development,

contributes to improving the health and wellbeing of Scotland’s people,

contributes to objectives in policy areas other than environmental policy,

integrates environmental policy objectives into the development of policies in other areas,

responds to global crises in relation to climate change and biodiversity.

The Strategy must be laid in the Scottish Parliament, and Scottish Ministers must, in making policies (including proposals for legislation), have due regard to the strategy.

Forthcoming policy milestone in Session 6: The Continuity Act requires the Scottish Government to publish an environmental policy strategy. The Scottish Government is required to report on progress towards this by 29 March 2022.

The UN SDGs and Scotland's National Performance Framework

The Scottish Government is committed to meeting the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to provide a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet (see Figure 1 below). The Goals form a core part of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by United Nations Member States in 2015.

The SDGs span environmental, economic and social goals that together aim to provide a coherent framework for wellbeing. As such, they are a helpful policy framework and lens with which to assess policy and legislative plans. SDGs also need to be localised to fit with their national context. The Scottish Government seeks to do this via its National Performance Framework.

Scotland’s National Performance Framework (NPF) is the main mechanism through which the Government states it is “localising and implementing” the SDGs. The NPF is Scotland’s wellbeing framework and sets out a vision for Scotland through eleven National Outcomes and associated indicators. It is intended to inform policy discussion, collaboration and planning across Scotland.

The 2018 refresh of the NPF mapped the SDGs against National Outcomes, and these Outcomes can be used in turn to support scrutiny - for example, the Scottish Government sets out in the Scottish Budget how spending in different areas aims to align with the National Outcomes.

Scotland's National Outcome - Environment: We value, enjoy, protect and enhance our environment

Vision:" We see our natural landscape and wilderness as essential to our identity and way of life. We take a bold approach to enhancing and protecting our natural assets and heritage. We ensure all communities can engage with and benefit from nature and green space. We live in clean and unpolluted environments and aspire to being the greenest country in the world.

We are committed to environmental justice and preserving planetary resources for future generations. We consume and use our resources wisely, ethically and effectively and have an advanced recycling culture. We are at the forefront of carbon reduction efforts, renewable energy, sustainable technologies and biodiversity practice. We promote high quality, sustainable planning, design and housing. Our transport infrastructure is integrated, sustainable, efficient and reliable. We promote active travel, cycling and walking, and discourage car reliance and use particularly in towns and cities."

Performance indicators: Performance against National Outcomes is assessed against a number of indicators. For the Environment National Outcome, indicators include waste generated, sustainability of fish stocks, biodiversity and energy from renewable resources.

Significant policy milestone in Session 6: Review of the National Performance Framework

The NPF is underpinned by the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015. The Act places a duty on Scottish Ministers to consult on, develop and publish National Outcomes for Scotland and to review them every five years. The next review is due in 2028.

Covid-19 and Our National Outcomes

The Scottish Government published an assessment of its progress towards the SDGs in 2020 before the pandemic, and in 2021 published an assessment of how the Covid-19 pandemic was impacting on National Outcomes. In relation to Covid-19 impacts on the environment National Outcome, the Government's assessment stated:

The steep contraction in economic activity during lockdown resulted in improvements in some environmental measures (such as some measures of air quality and early estimates of greenhouse gas emissions) and travel patterns also changed. However, some of these changes may prove to be temporary. The pandemic has also had harmful environmental impacts, such as increased use of plastics and packaging materials, reduced environmental monitoring and enforcement and delays to domestic and international negotiations and actions on climate. The future shape of travel and transport (an important source of greenhouse gas emissions) is also currently unclear and dependent on the evolution of the pandemic, the societal response, and whether any positive changes in behaviour around low carbon travel are maintained.

Sustainable development and scrutiny in the Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament is working towards embedding sustainable development across the organisation. This incorporates the Parliament's own environmental management as an institution, but also involves the need to mainstream sustainable development thinking and action across the organisation, including as part of its scrutiny function.

This work helps the Parliament meet the statutory requirements placed on all Scottish public bodies, under the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009, to act in the way it considers most sustainable. Standing Orders - the rules of Parliament - require the Scottish Government and others introducing legislation to assess sustainable development impacts, and for Parliament to scrutinise that assessment and the legislation itself.

Such an approach improves scrutiny by:

Garnering a broader range of evidence highlighting social and environmental issues

Mitigating committee silos through the more holistic approach of sustainable development

Focusing scrutiny on what is important – the root causes of problems and potential unintended or perverse consequences of policy/legislation

The Parliament is developing and seeking to integrate use of a Sustainable Development Impact Assessment (SDIA) tool - based on the requirement for users to talk through the implications of any given piece of policy or legislation. This enables users to engage with the issues, question assumptions, and develop a deeper understanding of implications.

Significant policy milestone in Session 6: The SNP manifesto committed to bring forward a Sustainable Development and Wellbeing Bill including a statutory requirement for all public bodies and local authorities to consider the long term implications of their decisions on people's wellbeing and on sustainable development.

Scotland's Environmental Principles

Environmental law and its enforcement is underpinned by a set of core principles which are set out in EU law, but also feature in a host of national and international environmental law instruments all over the world.

Environmental principles can be used to guide policy development, legislation and decision-making. They can be used in the context of both environmental policy, and more broadly to ensure that all types of policy and legislation, for example, avoid unintended consequences. The principles do not in themselves create direct legal rights but have been used by courts to interpret and apply environmental law.

What are Scotland's environmental principles?

Following the UK's exit from the EU, EU environmental principles were brought into Scottish domestic law via the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2021.

These 'guiding principles on the environment' as referred to in the Continuity Act are:

(a) the principle that protecting the environment should be integrated into the making of policies - sometimes referred to as the 'integration' principle

(b) the precautionary principle as it relates to the environment,

(c) the principle that preventative action should be taken to avert environmental damage,

(d) the principle that environmental damage should as a priority be rectified at source,

(e) the principle that the polluter should pay - sometimes referred to as the 'polluter pays principle'

Those principles are derived from the equivalent principles provided for in Article 11 of Title II and Article 191(2) of Title XX of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

Scottish Ministers must, in making policies (including proposals for legislation), have due regard to the guiding principles on the environment- except in matters relating to national defence or civil emergency, finance or budgets. Scottish Ministers are also required by the Act to publish guidance on the guiding principles on the environment, including on the interpretation of the principles and how compliance can be demonstrated. Public bodies (as specified in the Act) must also have due regard to the guiding principles on the environment when doing anything which requires a Strategic Environmental Assessment.

How the environmental principles are brought into domestic law in Scotland, in terms of their scope, application and interpretation, and whether this represents continuity with EU law, is an area of ongoing debate. This is also the case in other parts of the UK - for example in relation to how environmental principles are treated by the UK Environment Bill for England and Northern Ireland.

Significant policy milestone in Session 6: Guidance on application of the environmental principles: The Scottish Government is expected to publish draft guidance on the environmental principles early in Session 6.

Key bodies and regulators, and duties of public bodies

The specific roles and duties of environmental regulators, agencies and other public bodies in relation to the environment are discussed throughout this briefing under the relevant subject areas. Summary information on the roles of key bodies is provided in the Table below.

| Organisation | Type | Functions/responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| The Scottish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA) | An executive non-departmental public body* (NDPB), established by the Environment Act 1995. | Regulatory, licensing and enforcement functions (as well as policy input and operational advice) in relation to waste, pollution control, the water environment, air quality, industrial emissions, flooding, chemicals and radioactive substances. |

| NatureScot (formerly SNH) | An executive NDPB* | Lead public body on matters relating to the natural heritage, with advisory and licensing functions in relation to protected areas and species, wildlife management and aspects of land management. |

| Environmental Standards Scotland | A non-ministerial office, accountable to the Parliament, established under the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2021** | Scotland's environmental governance body, oversees Scottish Ministers' and other public bodies' compliance with environmental law. |

| Marine Scotland | A directorate of the Scottish Government. | Manages Scotland's seas and freshwater fisheries along with delivery partners NatureScot and SEPA. |

* Executive NDPBs carry out administrative, commercial, executive or regulatory functions on behalf of Government.

** ESS was established on an interim, non-statutory basis in 2020 but is expected to transition to its statutory form later in 2021.

SEPA Cyber-attack - In December 2020, SEPA announced that it was responding to a significant cyber-attack affecting its internal systems, processes and communications. SEPA stated that it was required to adapt working practices and prioritise services. Environmental implications of the cyberattack were not clear during Session 5. The Scottish Government has indicated that the cyber-attack on SEPA may be affecting certain areas of environmental policy development, for example the timeframe for the development of 2021-2026 Flood Risk Management Strategies.

The following table provides summary information about key organisations (mainly public bodies) whose functions and activities are relevant to environmental policy and outcomes in Scotland. This is not an exhaustive list - many public bodies carry out functions that are relevant to, or can impact on Scotland's environment.

Significant policy milestone in Session 6: The SNP manifesto set out a commitment to "develop a maritime strategy and set up a dedicated agency to put our marine assets at the heart of the blue economy" - so it is possible that some of the functions of Marine Scotland will move to a new agency in the coming years.

| Organisation | Type | Functions in relation to the environment |

|---|---|---|

| Zero Waste Scotland | Company limited by guarantee - but has previously stated it is working towards NDPB status and board appointments are subject to Ministerial approval. | Grant-funded by the Scottish Government to develop policies and strategies for the circular economy, waste reduction and resource efficiency. |

| Historic Environment Scotland | Executive NDPB, created by the Historic Environment Scotland Act 2014 | Leads delivery of Scotland’s strategy for the historic environment, and manages of properties of national importance. |

| Crown Estate Scotland | Statutory Public Corporation accountable to Scottish Ministers and to the Scottish Parliament | Manages Scottish Crown Estate assets including seabed out to 12 nautical miles. |

| Scottish local authorities and National Park Authorities | As described | Various functions and responsibilities relevant to the environment across planning, waste, air quality, biodiversity. |

| Scottish Water | A public corporation accountable to Scottish Ministers and the Scottish Parliament. | Key functions in relation to water quality and flooding. |

| Forestry and Land Scotland and Scottish Forestry | Executive agencies | Delivery of functions in relation to forestry and woodland relevant to nature conservation and other areas e.g. circular economy, flooding. |

Environmental standards and governance (following EU exit)

EU exit has triggered a period of fundamental change in environmental governance in Scotland. Prior to leaving the EU, environmental law in Scotland was heavily driven by the development of EU standards and underpinned by EU Directives. An estimated 80% of environmental regulation in Scotland was derived from EU law. This 'level playing field' or 'common floor' of environmental standards supported the functioning of the EU Single Market.

This involved areas where EU law set overarching frameworks or targets, but regulation was largely decentralised to Member States (and thus to Scotland as part of the UK) e.g. conservation of habitats and species. There are also areas where EU regulation is much more centralised e.g. eco-design standards, emissions trading and regulation of chemicals.

Environmental governance as part of the EU relied upon a range of arrangements, from the making of legislation, and the review of its implementation and enforcement by the European Commission and Court of Justice of the European Union. The implementation of EU environmental standards is often also supported by extensive guidance, joint funding initiatives, information sharing and other cooperation activities.

Since 1 January 2021 - the end of the transition period - EU law no longer applies in the UK and these related structures have also ceased to apply in Scotland. The following sections outline some key areas in relation to the development of post-EU exit environmental governance and standards in Scotland.

Maintaining or keeping pace with EU environmental standards post EU exit

The Scottish Government’s position following the EU referendum in 2016 was thatit would seek to maintain EU environmental standards after leaving the EU. It later set out that it will seek to use powers created in the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2021 ('the Continuity Act') to align with or 'keep pace' with EU environmental law where it believes it is appropriate.

Retained EU law

For the purposes of legal continuity, the UK Government wished to preserve, as far as possible, the legal position which existed immediately before the end of the transition period. This is sought to be achieved by taking a “snapshot” of all of the EU law that applied in the UK at the point of EU exit and bringing it within the UK's domestic legal framework as a new category of law, known as “retained EU law”. The creation of this new category of UK law was one of the main purposes of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018.

The process of taking that 'snapshot' of retained law began in Session 5 and involved the scrutiny of a large volume of secondary legislation, much of it on environmental standards, both as Scottish Statutory Instruments (SSIs) and UK Statutory Instruments (SIs). For SIs, consent of the Scottish Parliament on the exercise of devolved powers by UK Ministers was sought via an SI Protocol.

This means that, broadly, EU environmental standards (as they were at the point of EU exit) still apply in Scotland as retained law (althoughconcerns have been raised by stakeholders regarding to what extent certain aspects of EU regulation have been retained). Some areas of environmental law, which were applied through EU centralised systems and governance however - such as the regulation of chemicals, pesticides or emissions trading systems - have had to be re-created at Scotland or UK-wide level, and may not have exactly replicated or mirrored EU systems.

Keeping pace with EU environmental standards

The Scottish Government has indicated that, where appropriate, they would like to see Scots law continue to align with EU law, and committed that there will be no regression in standards1. There is likely to be significant interest in the coming years regarding to what extent the Scottish Government seek to and are able to align with evolvingEU environmental standards, especially in the context of a climate and ecological emergency.

The Continuity Act confers a power on Scottish Ministers to allow them to make regulations with the effect of continuing to keep Scots law aligned with EU law in some areas of devolved policy - the “keeping pace” power. The Act also sets out that the purpose of use of this power is to contribute towards maintaining and advancing standards in relation to specified matters - including for 'environmental protection'.

The Act requires the Scottish Government to publish a statement setting out their policy on, and how decisions will be made about, the use of the keeping pace power. This is likely to be of interest to environmental stakeholders. The Act also requires the Scottish Government to produce an annual report of the use of the keeping pace power, which might indicate future intentions of plans regarding alignment with EU law.

Significant policy milestone in Session 6: The Scottish Government will publish a policy statement on how it intends to use its 'keeping pace' power - relevant to the development of environmental standards in Scotland following EU exit.

The EU-UK TCA - how does the 'Brexit Deal' impact on Scotland's environmental standards?

Environmental protection is generally a devolved area, so in theory, the Scottish Government can continue to align with EU environmental law in future. However, in practice, in the absence of any baseline of standards in the UK linked to EU standards, there have been concerns that regulatory divergence across the UK, other trade agreements, UK internal market considerations, and leaving centralised EU regulatory systems could put pressure on standards in Scotland and inhibit future alignment.

The EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA or ‘the Agreement’) was applied provisionally from 1 January 2021 and entered into force on 1 May 2021. In the Agreement, the UK and the EU affirm the right of the other to determine the environmental protections it deems appropriate and agree to “continue to strive to increase their respective environmental levels of protection”.

The Agreement includes Level Playing Field (LPF) provisions – the notion that there should be comparable standards of environmental protection, and in other areas such as workers’ rights, across the territory of a free trade agreement. LPF provisions in the TCA provide that a number of environmental and climate levels of protection cannot be lowered, so-called 'non-regression', in a way which impacts trade and investment between the Parties i.e. the EU and the UK.

A ‘rebalancing’ provision sets out that if material impacts on trade or investment between the Parties arise as a result of significant divergences in environmental or climate protection or subsidy control, either Party may take 'rebalancing measures', e.g. impose tariffs.

The Agreement can be said to maintain a ‘floor’ for environmental protection across the UK to some extent. However, one limitation to this is that LPF provisions legally inhibit the weakening of former EU standards only so far as divergence impacts trade,or is seen as doing so by the Parties. The LPF provisions only apply where regression ‘affects’ trade or investment between Parties, or in the case of rebalancing provisions, where ‘material’ impacts on trade or investment arise as a result of ‘significant’ divergences in environmental protections. The actual implications of the TCA on future divergence of environmental standards between the UK and EU remains to be tested.

Interactions with other ‘pillars’ of postE-U exit governance: the UK Internal Market Act, Common Frameworks and future trade deals

The EU-UK TCA is now one part or ‘pillar’ of Scotland’s post-EU exit governance framework, each with implications for the Scottish Government’s ability to maintain EU environmental standards, and more broadly, to exercise its devolved competence on those issues. Other pillars include the UK Internal Market Act, Common Frameworks and potentially future trade deals.

The UK Internal Market Act 2020 (IMA) was developed in anticipation of leaving the EU single market, which previously facilitated intra-UK trade, and aims to create a coherent approach to market access and support for the UK internal market.

Two market access principles for goods and services are enshrined in the Act:

The principle of mutual recognition means that any good or service that meets regulatory requirements in one part of the UK can be sold in any other part, without having to adhere to the relevant regulatory requirement in that other part;

the non-discrimination principle establishes a prohibition on direct or indirect discrimination based on treating local and incoming goods and services differently (with some exceptions specified, including pesticides and fertilisers)

The principle of an internal market has support from many stakeholders from the perspective of facilitating internal trade. However, there are also questions regarding whether the Act could contribute to a race to the bottom on regulation or stymie the development of environmental standards in devolved nations2.

On the face of it, the IMA does not affect the ability of the devolved governments in Scotland and Wales to continue to regulate environmental policy as they wish. However, in practice, the market access principles in the IMA mean that any changes that lower regulation in another part of the UK, or any unilateral increase to standards in Scotland, could place Scottish business at a disadvantage. This is because products produced in or imported into another part of the UK may not be required to comply with the new higher standards in order to be sold in Scotland.

This could render certain policy interventions less effective, or potentially unworkable, unless pursued at UK- level, or unless there is explicit agreement about areas of divergence e.g. through Common Frameworks (see further below). Such interactions were raised in the Scottish Parliament’s scrutiny of the Internal Market Bill, which the Parliament did not give its consent to, with the Scottish Government stating the Bill would “encourage deregulation”. This has yet to be tested through real examples of divergence.

An early test case could be in waste regulation, with Scotland due to introduce a Deposit Return Scheme (DRS) in 2022, whereas the UK Parliament has yet to pass legislation enabling a scheme south of the Border. DRS in Scotland will mean businesses have to add a charge to certain drinks containers, and producers will be required to meet recycling targets, potentially requiring businesses to adjust practices in different parts of the UK (see more information below).

Common Frameworks

Common Frameworks will feature strongly as a ‘pillar’ in the post EU-exit environmental governance landscape. They are agreements on approaches to regulation being developed in a number of areas between the UK and devolved governments. Interim Common Frameworks are in place but have not been published, and none are yet finalised. They could be used to set out common ambitions or targets, regulatory floors, governance or other cooperation systems. They could thus operate to mitigate risks of competitive deregulation arising from the removal of the EU 'common floor' of standards.

Common Frameworks are expected in areas such as air quality, chemicals and pesticides, and resources and waste. Scrutinising Common Frameworks could include considering their alignment with key Scottish environmental strategies and legislation, and how they will impact on the exercise of devolved competence in that area. Environmental groups have highlighted the important role of common frameworks in areas such as waste regulation to prevent a 'race to the bottom' i.e. Governments competitively lowering standards3.

Significant policy milestone in Session 6: The publication of a number of post EU exit Common Frameworks across a number of environmental areas.

Implications of future trade deals

The EU-UK TCA is a single trade deal. The UK Government will go on to negotiate other trade agreements with potential implications for Scotland. The environmental implications of trade deals for Scotland were examined in a SPICe Briefing.

Key factors or 'Pillars' that will influence environmental standards in Scotland post EU exit, and the Scottish Government and Parliament’s associated devolved competence are summarised in Figure 2 below. The real implications of this ‘new order’ for environmental policy are only likely to become more clear over the coming years.

.png)

Environmental Standards Scotland

A key aspect of addressing post EU-exit governance gaps in Scotland was through the creation of a new public body, Environmental Standards Scotland (ESS).

Why was a new body needed?

As discussed above, environmental governance in Scotland - including enforcement of environmental law - included significant EU arrangements in addition to domestic ones when Scotland was part of the EU. Enforcement of EU law happened mainly through the European Commission, which supports best practice but can ultimately bring Member States before the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU). If found to be in breach of EU environmental law e.g. in relation to laws on protecting habitats and species, air or water quality, infraction fines can be imposed on the Member States. Both the UK and Scottish Governments recognised that if unmitigated, the loss of these arrangements would result in governance gaps after leaving the EU.

How was the new body created?

The Continuity Act established a new body - a non-ministerial office, accountable to the Parliament - called Environmental Standards Scotland (ESS), designed to provide "continuity of environmental governance". ESS was established on an interim basis in 2020 prior to the Continuity Bill passing. The new body is required to develop and publish a strategy within 12 months of being formally established. Appointments to ESS are made by the Scottish Ministers but must be approved by the Scottish Parliament.

What functions will the new body have?

ESS will monitor public authorities’, including Scottish Ministers’, compliance with environmental law, the effectiveness of environmental law, and how environmental law is applied. It may take appropriate action to secure a public authority’s compliance with environmental law, and to secure improvement in the effectiveness of environmental law or in how it is implemented or applied. This includes a power to issue ‘improvement reports’ where it finds a failure to comply with environmental law. In response to such a report, Scottish Ministers must present an improvement plan to the Scottish Parliament.

Post EU-exit environmental funding including rural support

EU funding schemes were significant for environmental projects and outcomes in Scotland. Key funding streams of relevance include the Agri-Environment Climate Scheme within the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), LIFE funding for conservation programmes, Horizon research funding, and European Structural and Investment Funds which funded green infrastructure for example.

The UK Government has proposed a UK Shared Prosperity Fund to replace EU Structural Funds, due to launch in 2022. During Session 5 the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee recommended that the Scottish Government engage with the UK Government to ensure that this Fund is designed to further environmental objectives1.

The development of post EU-exit regimes for rural and agricultural support is recognised as a significant issue for climate change and biodiversity, due to the large potential to influence land-use management on environmental outcomes.The Scottish Government is developing plans for post-CAP agricultural support. Though details have yet to be published, the Scottish Government has outlined key aims for this support, including shifting to low-carbon sustainable farming and improving biodiversity2. More information on post-EU exit rural support can be found in the SPICe Land Use Subject Profile, and in a SPICe briefing, Agriculture and Land Use - Public money for public goods?

PostE-U exit funding is also relevant for the marine environment. In March 2021, the Scottish Government launched Marine Fund Scotland (MFS) to replace the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF). The EMFF aimed to support "sustainable growth" of the marine economy in coastal communities, in sectors such as fishing, aquaculture and seafood processing. The Scottish Government states that the new Marine Fund will support investments and jobs in "seafood sectors, the marine environment and coastal communities".

Significant policy milestone in Session 6: This Parliamentary session will see further development and implementation of post-EU exit funding mechanisms in key areas for the environment including agriculture, the marine environment and infrastructure.

Proposals for a human right to a healthy environment

Recognising environmental rights in law is an increasingly widespread practice worldwide. In 2018, the First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership recommended that a new human rights framework for Scotlandshould include "a right to a healthy environment"1. The recommendation stated:

This overall right will include the right of everyone to benefit from healthy ecosystems which sustain human well-being as well [sic] rights of access to information, participation in decision-making and access to justice.

In 2019, the Scottish Government announced the National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership, to support work towards a Scottish Bill of Rights. The Taskforce published recommendations in a report in March 2021, which contains further background and context on the proposed right to a healthy environment2. The report states:

Through providing a right to a healthy environment the framework will demonstrate support for the Paris Agreement, demonstrate global leadership in supporting climate justice and contribute to the international cooperation so urgently needed to face the underlying climate crisis.

Significant policy milestone in Session 6: The Scottish Government may introduce primary legislation on human rights including a right to a healthy environment.

Waste and the Circular Economy

If everyone on Earth consumed resources as we do in Scotland, we would need three planets according to SEPA. Our consumption relies on unsustainable use of resources, including resources extracted in other parts of the world.

Scotland's Environment Strategy and Climate Change Plan recognise the need for Scotland to transition to a circular economy, where resources are kept circulating in the economy for as long as possible, maximising their value and minimising the impacts associated with their extraction, processing and disposal. The Scottish Government published a Circular Economy Strategy in 2016 stating that the transition to a circular economy was "an economic, environmental and moral necessity".

Waste management policy in Scotland generally seeks to divert waste away from landfill and further up the ‘waste hierarchy’, set out in law in the Environmental Protection Act 1990. Under the waste hierarchy, waste prevention through efficient use and reuse of resources, recycling and recovery of value should be prioritised in that order, with landfill or other disposal a last resort (see Figure 3).

Waste is generally a devolved area, and the Scottish Government has pursued distinct approaches to waste policy to the rest of the UK under a framework of EU law, such as distinct recycling targets and developing its Deposit Return Scheme. A number of areas of waste policy and regulation have also been pursued at UK-level, due to UK internal market reasons or the overlap between devolved and reserved areas. Some specific areas of waste regulation are reserved because they fall under reserved areas of product standards or import and export control.

Circular economy policy is a broader concept than waste management and can be applied across the whole economy, for example to energy, industry, agriculture, or procurement– as it relates to the circularity of resource use. Moving towards more sustainable consumption can contribute substantially to environmental goals, but also to wider wellbeing, poverty alleviation and the transition towards low-carbon economies1.

Waste regulation, roles and key legislation

The Environmental Protection Act 1990 (as amended) sets out a number of duties with respect to the management of waste. Waste must be managed correctly by storing it properly, transferring it to the appropriate persons and ensuring that when it is transferred it is sufficiently described to enable safe recovery or disposal.

The Waste (Scotland) Regulations 2012 amended the 1990 Act to implement actions in the Scottish Government’s 2010 Zero Waste Plan. Holders of waste, including producers, have a duty to take reasonable steps to increase the quantity and quality of recyclable materials. The Scottish Government produced a Duty of Care Code of Practice to explain the duties which apply to anyone who produces, keeps, imports or manages controlled waste in Scotland1.

The Waste (Scotland) Regulations 2011 and the Waste Management Licensing (Scotland) Regulations 2011 also place a duty on all persons who produce, keep or manage waste, including local authorities, to take all reasonable steps to apply the waste hierarchy.

There are various other areas of regulation covering specific categories of waste management such as special waste i.e. waste with hazardous properties or waste electrical equipment.

SEPA is Scotland's lead agency on waste regulation, fulfilling a number of regulatory, advisory and monitoring roles including:

Licencing and monitoring waste management facilities such as landfills and incinerators;

Administering producer compliance schemes for particular waste streams;

Regulating the transfrontier shipment of waste;

Responding to pollution incidents and fly-tipping;

Tackling illegal activities in partnership with the police such as illegal landfill, unlicensed operatorsand persistent dumping of waste;

Collecting and interpreting waste data.

There is extensive guidance on waste management and licensing on the SEPA website.

Local authorities: Local authorities are responsible for collecting waste as defined in the Environmental Protection Act 1990. The Waste (Scotland) Regulations 2012 require local authorities to provide a minimum recycling service to householders. Local authorities also often act in the capacity of a waste broker. Associated responsibilities e.g. ensuring waste is transferred to someone who is authorised to receive it, are set out in the Scottish Government Duty of Care Code of Practice. The Household Recycling Charter and Code of Practice (CoP) are not legally binding but have been adopted by most local authorities, with a view to achieving a more consistent approach to the provision of recycling services across Scotland.

Zero Waste Scotland:Zero Waste Scotland is a company limited by guarantee that receives funding from the Scottish Government to support Scotland's transition to a circular economy. Key roles include supporting the implementation and development of Scottish Government circular economy policy and regulations through business support, guidance, research and administering funding e.g. the Circular Economy Investment Fund.

Revenue Scotland: Revenue Scotland administer the Scottish Landfill Tax, a devolved tax, with support from SEPA. The Scottish Landfill Tax replaced UK Landfill Tax in Scotland in 2015, following the passage of the Scotland Act 2012 and subsequent Landfill Tax (Scotland) Act 2014. Landfill tax has escalated over time, aiming to support the transition away from landfill.

Waste and recycling targets and progress to date

Current key Scottish Government targets in relation to waste and recycling are:

To recycle 70% of all waste by 2025.

To reduce food waste by 33% from the 2013 baseline by 2025.

To end the landfilling of biodegradable municipal waste by January 2025.

To reduce the percentage of all waste sent to landfill to 5% by 2025.

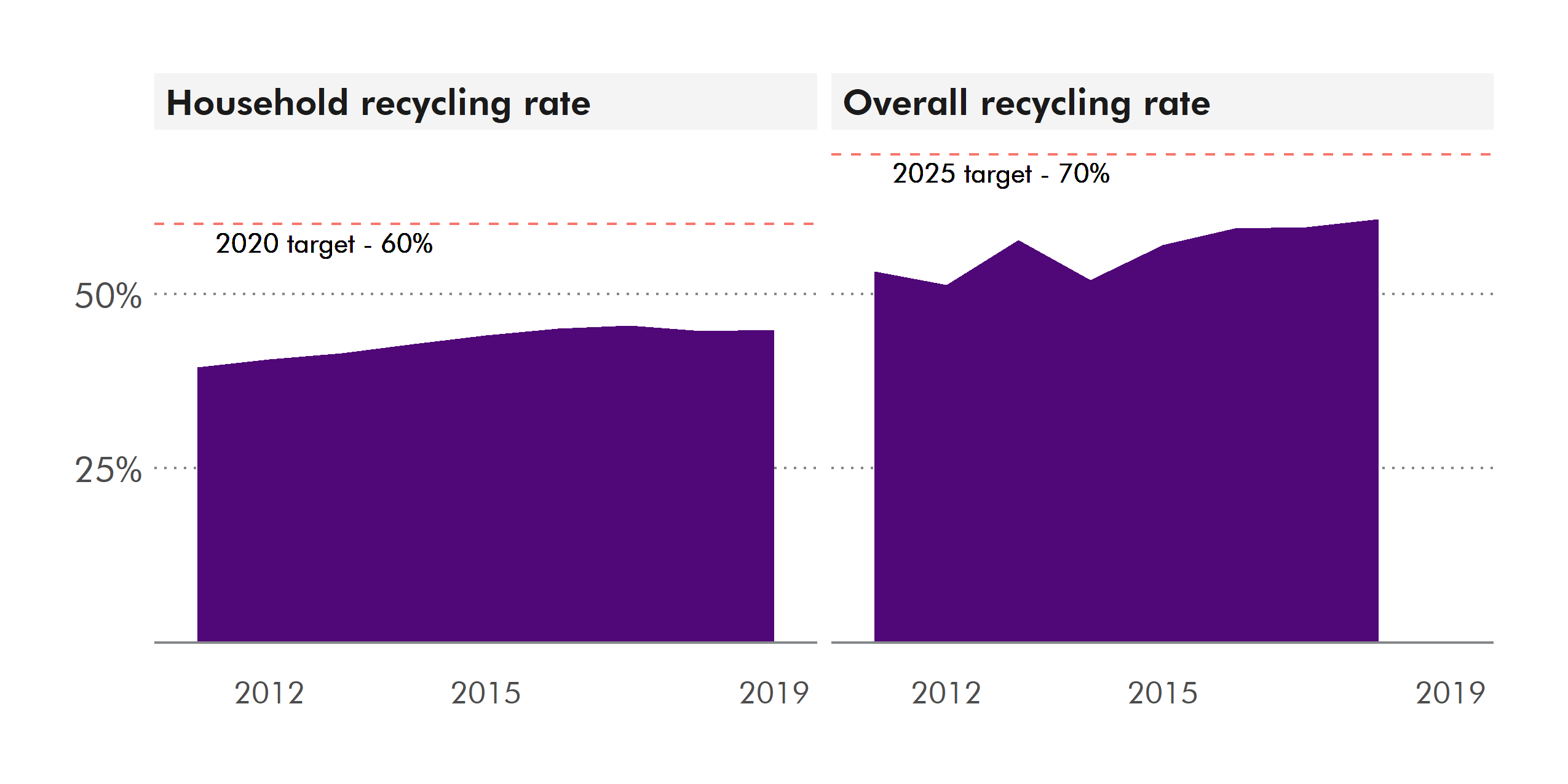

Recycling rates in Scotland: The recycling rate for all waste in 2018 was 60.7%, an increase from 59.6% in 2017. In 2018 the household waste recycling rate was 44.7%, a decrease from the 45.5% rate achieved in 2017 (see Figure 4 below). The 2020 household recycling target of 60% is unlikely to be met although final figures are not yet published.

Food waste: The Scottish Government states that Zero Waste Scotland's 2016 food waste report provides the best insight into the scale of food and drink waste in Scotland1. It set out that in 2013, an estimated 987,890 tonnes of food and drinkwas wasted, 60.6% by households, 25.1% in food and drink manufacturing, and 14.2% in other sectors. A review of progress is expected in 20212.

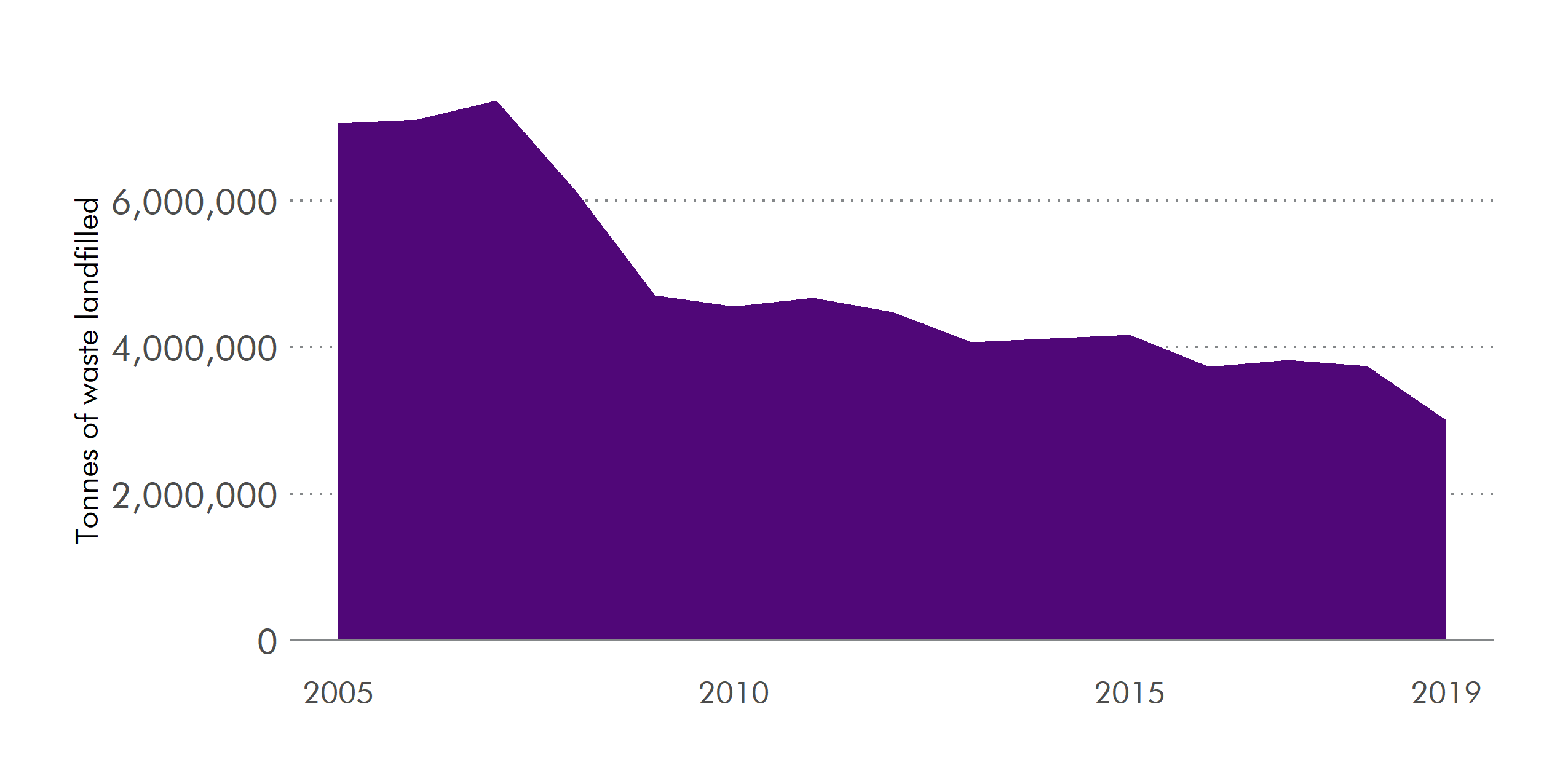

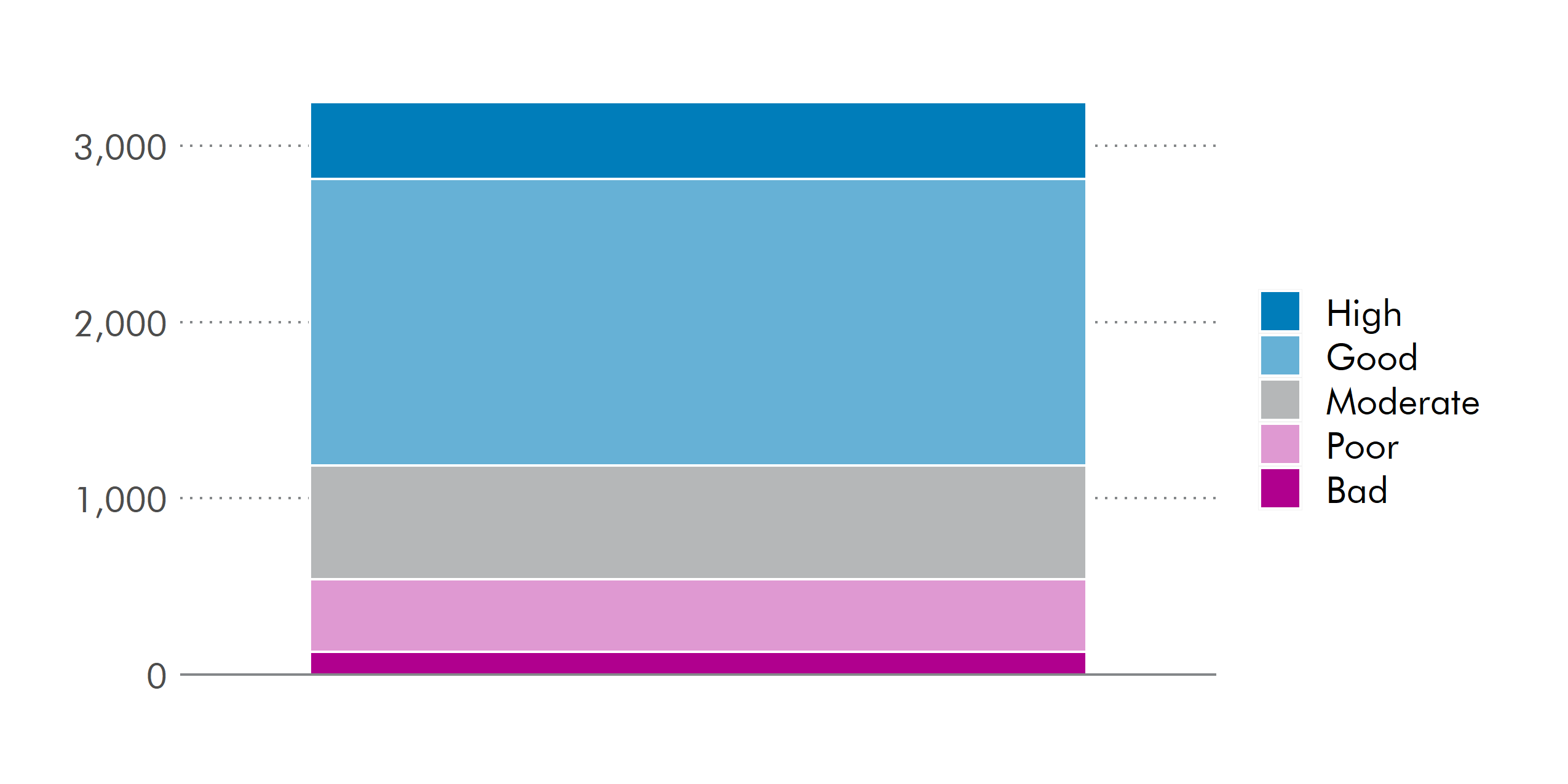

Waste to landfill: Recycling increases and escalating landfill tax have progressively reduced the amount of waste sent to landfill (see Figure 5 below) - although reductions anticipated in the 2018 Climate Change Plan have not been achieved. Scotland sent 3 million tonnes of waste to landfill in 2019, a reduction of 20% from 2018 and 57% from 2005.

Landfilling of biodegradeable waste: The landfilling of biodegradable municipal waste has progressively reduced in Scotland. In 2019, 0.70 million tonnes of biodegradable municipal waste were disposed to landfill in Scotland, a decrease of 32% from 20184.

Waste generated: The Scottish Government publishes information about total waste generated as a National Performance Indicator, in relation to its National Outcome on the environment. The amount of household waste generated in Scotland rose by 0.7 % (17 thousand tonnes) between 2018 and 2019. There has been a reduction of 7 % since 2011.

Greenhouse Gas emissions associated with consumption and waste

GHG emissions associated with waste management

In 2019, emissions from waste represented around 3% of total Scottish GHG emissions, compared to approximately 8% in 19901. The majority of GHG emissions from waste are methane. Significant reductions from 1990 to 2019 (approximately 74% reduction) were achieved mainly due to landfill gas (methane) being increasingly captured and used for energy, reduction in biodegradable waste going to landfill, and increases in recycling. Emissions reductions have stalled since 2013 and slightly reversed, with emissions increasing from 1.45 MtCO2e in 2013 to 1.54 MtCO2e in 20191 (see Figure 6 below). The Scottish Government’s aim, set out in the Climate Change Plan update, is to reduce emissions to 1.2 MtCO2e by 2025, and 0.8 MtCO2e by 20303.

.png)

Consumption emissions - Scotland's carbon footprint

Circular economy policy raises the significant issue of Scotland’s consumption emissions or ‘carbon footprint’. Statutory climate targets are based on emissions from sources located in Scotland. However, consumption of products and materials accounts for an estimated 74% of Scotland’s carbon footprint, when those emissions are factored in4. This means that Scotland cannot play its part in addressing the climate emergency without tackling its consumption emissions. The Scottish Government commits in its Environment Strategy to be “responsible global citizens with a sustainable international footprint”.

The Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 requires Scottish Ministers to report on emissions from Scottish consumption of goods and services. Whilst GHG emissions on a territorial basis in Scotland fell by 45.8% between 1998 and 2017, Scotland’s carbon footprint only fell by 21.1 % over the same period, from 89.6 MtCO2e in 1998 to 70.7 MtCO2e in 20175.

Key areas of development in waste and circular economy policy

Circular Economy Bill

Prior to the pandemic, the Scottish Government was committed to introducing a Circular Economy Bill during session 5 of the Scottish Parliament. The Government consulted on proposals for legislation in 2019, with a range of proposed measures to encourage product reuse and waste reduction, and delegated powers to enable charges to be applied to unsustainable products. This followed 2019 recommendations from an Expert Panel on Environmental Charging.

The Bill was postponed due to the pandemic. The Climate Change Committee's 2020 Progress Report on Scotland recommended that progress needs to be maintained on resource efficiency, with early investment, and that a Bill should be introduced in the next Parliament1. The SNP manifesto re-committed to the Bill, stating that a Circular Economy Bill willinclude measures to encourage reuse,tackle reliance on single-use items and tackle textiles pollution or 'fast fashion'.

Forthcoming policy milestone in session 6: The Scottish Government is expected to introduce a Circular Economy Bill, having consulted on proposals for legislation in session 5.

Climate Change Plan update commitments on waste and the circular economy

The Scottish Government's 2020 Climate Change Plan update makes a number of policy commitments on waste2 and sets out a vision that by 2045, Scotland will have moved from a ‘take, make and dispose’ linear economy to a circular economy. Key commitments include:

To develop a post 2025 route map to identify how the waste and resources sector will contribute to net zero;

To evaluate the Household Recycling Charter and review its Code of Practice;

To introduce measures to encourage more sustainable consumer purchasing, including to consult on a charge on disposable drinks cups and to increase the carrier bag charge from 5p to 10p (the latter commitment was implemented in April 2021).

To examine the range of fiscal measures e.g. environmental taxes, levies and charges used by other countries to incentivise positive behaviours and to develop proposals in this area.

The Government aims that the implementation of a Deposit Return Scheme, UK-wide reform of producer responsibility (more information is set out below), together with a review of the Recycling Charter will boost recycling rates.

Forthcoming policy milestone in Session 6: The Scottish Government is expected to bring forward a new route map to meeting waste and recycling targets for 2025.

Ending the landfilling of biodegradable municipal waste by 2025

The landfilling of biodegradable municipal waste is a source of methane emissions, a gas which tonne for tonne is 25 times more damaging than carbon dioxide (but shorter lasting in the atmosphere). The landfilling of biodegradable municipal waste was banned from January 2021 under the Waste (Scotland) Regulations 2012, but the Government announced in 2019 that enforcement will be delayed until 2025, due to a lack of progress with reprocessing infrastructure. The Scottish Government is working with partners on infrastructure requirements, and to support coordinated procurement by local authorities of alternative solutions to comply with the forthcoming ban. The Government is also exploring the role of landfill tax in supporting compliance3.

Review of the role of incineration in Scotland's waste management

Part of the reduction in waste to landfill in Scotland has been due to an increase in recycling, but it is also because waste has been diverted from landfill to incineration. The total quantity of waste incinerated in Scotland in 2019 was 1.23 million tonnes across 24 facilities, an increase of 72% from 2018, and an increase of 199% from 20114. SEPA has stated that this rise in incineration of waste is likely to be the start of an increasing trend as waste is diverted from landfill ahead of the 2025 ban outlined above4.

The role of incineration and Energy from Waste plants (where incinerators or other waste processing facilities generate energy as electricity or heat) in decarbonisation is a controversial issue and was raised during scrutiny of the 2020 Climate Change Plan update. In the plan, the Scottish Government commits to “consider measures to ensure new energy from waste plants are more efficient and how waste infrastructure can be ‘future-proofed’ for carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology”. Zero Waste Scotland and other stakeholders raised concerns that there are risks of an unsustainable 'lock-in' to incinerating waste.

The Scottish Government has since committed to review the role of incineration in Scotland's waste hierarchy.

Reform of extended producer responsibility - UK-wide

Whilst waste is generally a devolved area, there is a history of collaboration between the UK and devolved governments on some aspects of waste management including UK-wide producer responsibility schemes - currently in place for packaging waste, Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) and End of Life Vehicles.

The Scottish Government is working with the UK Government and other devolved administrations to reform and expand packaging producer responsibility - which seeks to make producers of packaging responsible for the end-of-life costs of recycling and disposal. Reforms were consulted on earlier in 2021. Other producer responsibility regulations are also being reviewed.

The UK Environment Bill sets out shared delegated powers to regulate on producer responsibility and resource efficiency - meaning that the UK Government could introduce UK-wide Regulations with the consent of Scottish Ministers,triggering scrutiny by the Scottish Parliament under the SI Protocol. In its consideration of the Legislative Consent Memorandum for the UK Environment Bill, the ECCLR Committee raised concerns that there would be a limited role for the Scottish Parliament in relation to how shared powers in the Bill are exercised6.

The UK Environment Bill also introduces delegated powers to enable resource efficiency or 'ecodesign' schemes to be taken forward either via parallel regulations by each of the UK and devolved Governments, or by UK Regulations with the consent of Scottish Ministers and other devolved Governments. This was previously a highly centralised area of EU law.

Forthcoming policy milestone in session 6: The Scottish Government is working with the UK Government on reforms to producer responsibility regimes, where Regulations may take the form of a UK Statutory Instrument using shared powers in the UK Environment Bill. This could represent an early test of the opportunities for scrutiny by the Scottish Parliament of UK-wide regulation introduced using new 'shared powers'.

Food waste (target to reduce food waste by 33% by 2025 from 2013 baseline)

In 2019, a Food Waste Reduction Action Plan was published by Zero Waste Scotland, outlining actions for reducing food waste. The Scottish Government also consulted on proposals for legislation around its ‘Good Food Nation ambition’ in 2018, including proposals on food waste. Plans for a Bill in Session 5 were cancelledin light of the pandemic, however the SNP manifesto included a re-commitment to a Good Food Nation Bill.The Climate Change Plan update in 2020 set out plans for consultation in 2021 on mandatory reporting of food waste by businesses, a mandatory food waste reduction target, and on requirements for food waste collections.

Forthcoming ban on certain Single-Use Plastics

In March 2021, the Scottish Government consulted on Draft Regulations which would introduce market restrictions (essentially a ban) on some plastic items. These include single-use plastic cutlery, plates and food and drink containers made of expanded polystyrene. This is based on the Scottish Government's commitment to meet or exceed the standards set out in the EU Single Use Plastics Directive.

Developing EU standards - the EU Circular Economy Package

Some areas of development of the circular economy have been heavily driven by EU policy development, such as the EU Circular Economy Package. The Scottish Government recognises this in the Climate Change Plan update and re-commits to maintaining or exceeding EU environmental standards post EU exit.

Common Frameworks and the UK Internal Market Act

A Common Framework is expected to be agreed on waste and resources. The alignment of UK-wide waste measures with Scotland’s circular economy ambitions will require consideration. The UK Internal Market Act 2020 (described in more detail in above sections) also raises questions about implications for circular economy policy in Scotland post EU exit. This issue is explored in more detail in SPICe blog ‘The Internal Market Bill – a threat to the circular economy in Scotland?’

Deposit Return Scheme

Underthe Deposit and Return Scheme for Scotland Regulations 2020,from July 2022, people in Scotland will be required to pay a returnable deposit when buying a drink in certain single-use drinks containers. Aims include to boost recycling, reduce litter and reduce emissions.

Key aspects of the scheme include:

The deposit (20p) will be applied to containers of all drinks that come in PET plastic, metal and glass, sized 50ml to three litres.

Any retailer selling drinks covered by the scheme will be required to accept returns, including online retailers – unless an exemption is granted.

The Regulations set a target of 90% of scheme packaging being recycled from 2025 onwards (with interim targets of 70% in 2023 and 80% in 2024).

Scottish Ministers must, before 1 October 2026, review the operation of the Regulations and lay a report before the Scottish Parliament.

Detailed information can be found on the Zero Waste Scotland website. Scotland has been the first mover on DRS in the UK, with enabling powers introduced in the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009.

Impact of Covid-19 on DRS introduction

The Scottish Government announced in March 2021 that it has commissioned an “independent gateway review” to assess the impact of the pandemic on the go-live date for the DRS.

Potential for interoperability with other UK schemes

The UK Government is also developing plans for the introduction of a Deposit Return Scheme in England, Wales and Northern Ireland,although powers are yet to be established in primary legislation - they are contained in the UK Environment Bill. In a UK Government consultation on DRS in March 2021, it stated its intention is "to work with Regulators in Scotland to develop a coherent approach across the UK".

Implications of the UK Internal Market Act 2020

As discussed in other parts of this briefing, the UK Internal Market Act 2020 has raised questions about implications for devolved competence in areas which may be impacted by the internal market principles in the Act. The Act does not prevent the Scottish Parliament from passing circular economy legislation or enforcing any requirements on goods produced in Scotland or imported directly into Scotland from outside the UK. However, there are clearly questions around how and to what extent certain devolved policies will be able to effectively operate under this legislation, where the policy or scheme is not UK-wide and requires businesses to adjust products or practices in different parts of the UK. The UK Government’s White Paper on the Bill specifically referenced recycling of drinks containers, including DRS, as an example where future divergence could be problematic.

The previous Cabinet Secretary for Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform said that the Scottish Government'sinitial assessment of the UK Internal Market Bill was that it could significantly undermine the effectiveness of DRS in Scotland1. In practice, this issue may be mitigated if there is agreement between Governments to pursue inter-operability.

Biodiversity and wildlife management

What is biodiversity and why is it important?

Biological diversity – or biodiversity – is the variety of life on earth. It includes genetic diversity within species and variation between species and ecosystems.1 Scotland's biodiversity includes a huge variety of marine and land-based ecosystems - where living organisms interact with each other and their non-living environment- home to an estimated 90,000 species.2

Biodiversity is fundamental to the ability of humans to survive and thrive. Nature contributes to human survival and flourishing by providing specific benefits, called "ecosystem services". For example, 35% of global crop production depends on insect pollination3. Marine and terrestrial ecosystems sequester (absorb) 60% of global Greenhouse Gas emissions per year, mitigating climate change4. Genetic diversity underpins species diversity by providing the capacity for life to be resilient and adapt to change - buffering against extinction risk5- and can be harnessed by humans e.g. to improve agriculture6. Biodiverse environments are more likely to be resilient to disturbances like extreme high temperatures7, support a range of functions and, subsequently, provide benefits to humans.8

This is recognised in the "ecosystem approach" which is the primary framework for action under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (the major international treaty on biodiversity). This is also applied in the current Scottish Biodiversity Strategy which takes into account interactions between different parts of ecosystems, and ecosystem services in how land, freshwater and sea environments are managed.

The global value of ecosystem services has previously been estimated by scientists as 125 trillion $US per year, though there are difficulties with such estimates9, and some benefits of biodiversity - such as spiritual and aesthetic values - are less tangible and difficult to measure. The Dasgupta Review - an independent, global review on the Economics of Biodiversity published in February 2021 - highlights that mainstream measures of economic value are incomplete and misleading because they tend to exclude nature. Economies are embedded in, and cannot overcome their dependence on nature.8

The ecological emergency - a nature crisis

Together, the climate and ecological 'twin' crises pose a real threat to human safety, health and wellbeing, economies and natural ecosystems. In the SPICe Key Issues for Session 6 briefing, the climate and ecological emergencies, and consequent requirement for a green recovery from Covid-19, are identified as a cross-cutting theme for the coming Parliamentary Session (alongside Covid recovery, the devolution settlement and UK relations post EU exit).

The global loss of biodiversity - a sixth mass extinction?

Recent global reviews highlight the extent of biodiversity decline on land and at sea. The landmark 2019 Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services or ‘IPBES review’ issued a stark warning that nature is declining at unprecedented rates, and that most of the 2020 targets under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity will be missed1.

New global goals for 2030, expected to be agreed at the 15th biodiversity COP in China in May 2022(with negotiations kicking off virtually in October), will only be achieved, the review states, through ‘transformative change’. The latest CBD reports agree with IPBES research findings that urgent, transformative change is required to address the nature crisis.

IPBES reports widespread declines in ecosystem, species and genetic diversity including that:

75% of the land surface and 66% of the ocean area has been significantly altered by humans while more than 85% of wetland area has been lost.

An average of around 25% of species in assessed animal and plant groups are threatened with extinction (around 1 million species). Average abundance of native species in most major land-based habitats has fallen by at least 20%, mostly since 1900.

Extinctions have occurred at a relatively stable rate throughout history - known as the background extinction rate - aside from five mass extinction events caused by geological processes and changes to Earth's atmosphere and climate. Current vertebrate extinction rates are estimated to be up to 100 times greater than the background rate and scientists argue that we are in the midst of a'sixth mass extinction': the first ever to be caused by humans2.

Biodiversity loss in Scotland - intrinsically linked to the climate crisis

Evidence of biodiversity decline and its implications led the previous Scottish Government to commit in 2020 to a step change in efforts to address it.

The 2019 State of Nature in Scotland report mirrored the global picture set out by IPBES, illustrating that there has been no letup in the net loss of nature in Scotland (see Figure 7 below)3. Nearly half of the country’s species have declined in the last 25 years, and one in nine is threatened with extinction from Great Britain (the scale at which assessments are made).

Scotland failed to meet 11 of the 20 global Aichi biodiversity targets for 20204 (globally the CBD reported that none of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets were met in full).

.png)

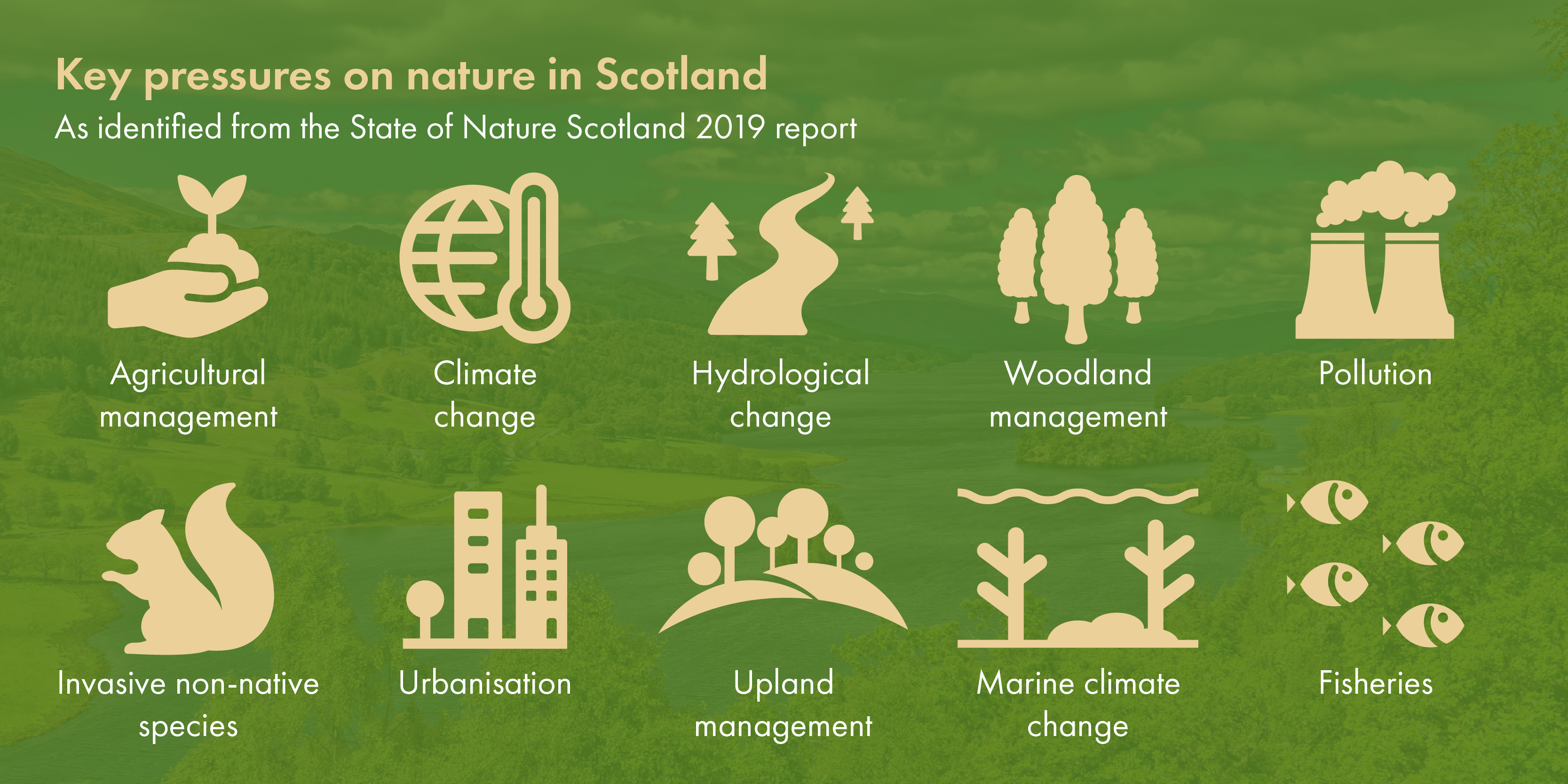

Key pressures on biodiversity in Scotland include agriculture, climate change, urbanisation, invasive species, upland management and fisheries (see Figure 8 below).

The Environment Strategy for Scotland, published in 2020, recognised that the climate and nature crises are intrinsically linked. Climate change is a significant contributor to biodiversity loss and impacts on biodiversity are expected to be significantly greater if warming exceeds 1.5 degrees. Scaling up nature-based solutions to climate change such as peatland restoration and enhancing woodlands, could, on the other hand, be significant in delivering climate goals.

Biodiversity strategies and key legislation

NatureScot and the Scottish Government co-lead the Scottish Biodiversity Programme which oversees activity on biodiversity including policy, reporting and funding. This work is supported by SEFARI which delivers the Strategic Research Programme on environment, food, agriculture, land and communities.

Forthcoming biodiversity COP - a key opportunity to tackle the nature crisis

The United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) is the key international treaty on biodiversity. Since its initiation, there have been fourteen meetings of the Conference of the Parties (COP), the decision making body for the Convention. COP15 is due to be held in April-May 2022 with virtual meetings starting in October 2021 - it was postponed from 2020 due to the pandemic.

The Edinburgh Declaration published by the Scottish Government in August 2020 outlines hopes for the post-2020 global biodiversity framework of sub-national Governments. In December 2020 Scottish Government also published a Statement of Intent on Scotland's post-2020 biodiversity strategy which includes a commitment to publish a new biodiversity strategy for Scotland within 12 months of COP15.

Scotland's Biodiversity - It's In Your Hands was Scotland's first biodiversity strategy to 2030, published in 2004. This has since been supplemented by the 2020 Challenge for Scotland's Biodiversity - Scotland's response to the 2020 Aichi Targets. This was supported by Scotland's Biodiversity: A Route Map To 2020 which outlined priority work.

The Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004 requires reporting on progress on any biodiversity strategy every three years. The Scottish Biodiversity Strategy (SBS) Coordination Group oversees reporting and delivery. Under the 2004 Act, public bodies in Scotland also have a statutory duty to further the conservation of biodiversity. The Wildlife and Natural Environment (Scotland) Act 2011 requires every public body in Scotland to produce a report on compliance with the Biodiversity Duty every three years. Further key legislation relevant to biodiversity is spread across a number of areas e.g. protected areas, the marine environment and wildlife crime - referenced in below sections.

The Environment Strategy

The Environment Strategy for Scotland's overarching vision is:

One Earth. One home. One shared future. By 2045: By restoring nature and ending Scotland’s contribution to climate change, our country is transformed for the better - helping to secure the wellbeing of our people and planet for generations to come.

The strategy takes into account the necessity to deliver positive outcomes for nature across a range of connected policy areas. For example, one Strategy outcome is “Scotland’s nature is protected and restored with flourishing biodiversity and clean and healthy air, water, seas and soils”.

Other priorities for Scotland

In her Priorities of Government Statement in 2021, the First Minister announced the aim to “protect and enhance our natural habitats”, increase woodland creation by 50% and invest £250 million in peatland restoration this decade. 22.7% of Scottish land area is currently protected and the Government has committed to increasing protection on land to at least 30% by 2030.

Some key interactions between biodiversity policy and other policy areas, which are likely to be live issues this session include:

Nature-based solutions to climate change policy and delivery (see further below);

Development of post EU exit support systems for agriculture and interactions with other land-use policy (see SPICe Subject Profile on Land Use and Rural Policy) and post EU exit governance of fisheries (see SPICe Subject Profile on Marine and Fisheries);

How nature interests are represented in the forthcoming National Planning Framework 4;

Policies and legislation to decarbonise and build a circular economy.

Protected areas, protected species and nature networks

What are protected areas?

One mechanism for the conservation of habitats and species is through designating sites as protected areas. Scotland's system of protected areas for nature began in the 1940s and subsequently was heavily shaped by EU law. Protected areas are designed to ensure that their natural features of special interest remain in good health.

Types of protected area

Sites can be protected based on international directives and treaties, domestic legislation and policy, or voluntarily based on local needs and interests. Key types of protected area are:

European sites – Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) and Special Protection Areas (SPAs) – were originally designated under the EU Habitats and Birds Directives and known as Natura sites. They continue to be protected under domestic law, now known as 'European sites', as a snapshot of EU law was transferred into domestic law as 'retained law'. European sites are internationally important areas for threatened habitats and species - and their designation creates legal objectives to work towards their favourable conservation status (FCS). They can be terrestrial or marine. They are designated under the Conservation (Natural Habitats, &c.) Regulations 1994.

The condition of protected nature sites is a performance indicator under the National Performance Framework. In March 2021, 78.3% of natural features were assessed as being in a favourable condition.

Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) - are areas of land and water designated by NatureScot as representing the best of Scotland's natural heritage in terms of flora, fauna, geology and geomorphology (landforms). It is a statutory designation made under the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004. Scotland has 1,422 SSSIs, covering 12.6% of Scotland’s land area. SSSIs are terrestrial i.e. areas above mean low water springs. Many SSSIs are also designated as European sites. NatureScot work with land owners and managers with a view to ensuring appropriate management of a site’s natural features. NatureScot must also consent to certain operations on SSSIs.

Ramsar sites are designated under the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance.Scotland has 51 Ramsar sites designated as internationally important wetlands, covering about 313,000 hectares. There is no dedicated legislation for the protection of Ramsar sites in the UK; all Scottish Ramsar sites are either SPAs, SACs or SSSIs and are protected under those statutory regimes. In 2019 the Scottish Government published a policy statement on how it expects Ramsar sites to be protected.

Marine Protected Areas are discussed in the following section.

Other types of protected area include National Nature Reserves (NNRs), National Parks, Local Nature Reserves and World Heritage Sites.

The NatureScot webpage SiteLink can be used to view and download information on designated sites across Scotland.

Who manages and monitors protected areas?

Protected areas are not necessarily publicly owned. NatureScot directly manages some, advises on the management of others and monitors the condition of SSSIs and European sites.

Implications of COP15 for protected areas

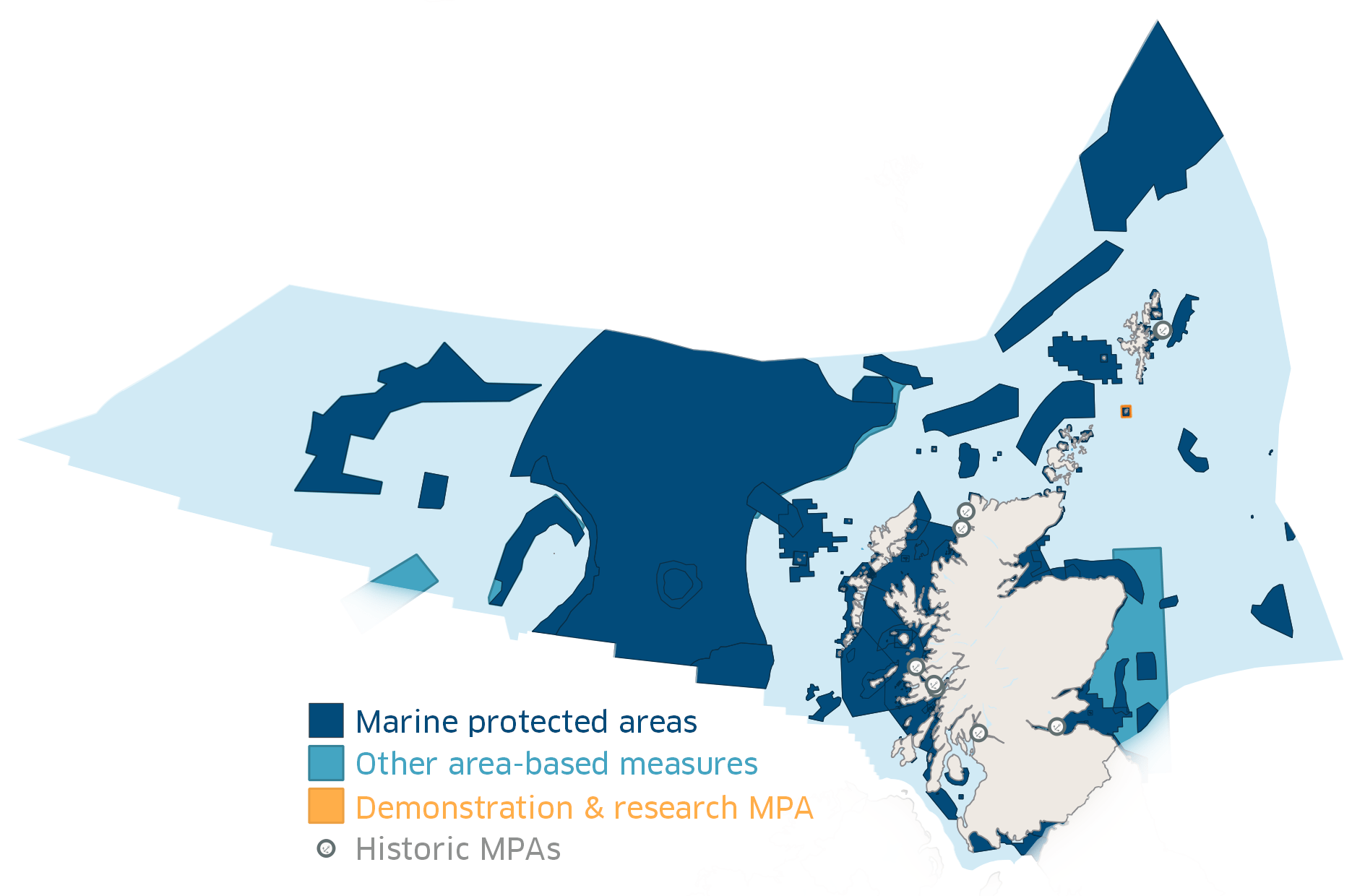

Currently, 37% of Scotland’s marine environment receives protection with 22.7% of terrestrial land protected for nature.

The first Draft of the CBD post 2020-biodiversity framework, published in July 2021, includes a proposed new global target to "ensure that at least 30 per cent globally of land areas and of sea areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and its contributions to people, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes".

The European Commission's Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 already commits to at least 30% of seas designated as protected areas by 2030, with at least a third of these strictly protected.

The Scottish Government announced in 2020 that it plans to meet this proposed target and protect at least 30% of Scotland’s land for nature by 2030 – and to examine options to extend this further.

Despite the focus that the 30% target has created, debate around protected areas in Scotland is more often related to how protected sites are managed, how well site objectives are implemented and the level of protection those designations actually provide (especially in relation to the marine environment), as opposed to the overall size of the network. There is also increasing focus on how measures outwith protected areas ensure that there is ecological connectivity to adequately protect and enable restoration of priority habitats and species e.g. through nature networks.

Marine protected areas and other approaches

Key legislation

The overarching legal framework for the protection of marine habitats and species in Scotland is provided by the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 and the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 ('the Marine Acts'). More information on this legal framework is provided in the SPICe Marine and Fisheries Subject Profile.

The Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 gives Scottish Ministers powers over Scotland's territorial waters (waters up to 12 nautical miles off the coastline, known as the Inshore Zone). The Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 gives Scottish Ministers powers over Scottish offshore waters (the Exclusive Economic Zone and continental shelf).

Section 3 and 4 of the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 require that when exercising powers under the Act, Scottish Ministers and other public authorities must (emphasis added):

act in the way best calculated to further the achievement of sustainable development, including the protection and, where appropriate, enhancement of the health of that area, so far as is consistent with the proper exercise of that function

And -

act in the way best calculated to mitigate, and adapt to, climate change so far as is consistent with the purpose of the function concerned.

More specific requirements for marine conservation fall under the setting out and implementation of a National Marine Plan and Nature Conservation Marine Protected Areas.

The National Marine Plan

The Marine Acts require Scottish Ministers to publish a National Marine Plan (NMP) covering inshore and offshore waters. The National Marine Plan must set:

economic, social and marine ecosystem objectives

objectives relating to the mitigation of, and adaptation to, climate change.

When preparing a marine plan, Scottish Ministers are required to prepare an assessment of the condition of the Scottish marine area including significant pressures. The most recent Marine Assessment was published in 2020 – it highlighted pressures associated with non-indigenous species, climate change and ocean acidification. Pressures associated with bottom-contacting and pelagic (mid-water) fishing were cited as the most geographically widespread. A review of the NMP was published earlier in 2021 and Ministers must now decide if replacement or amendment of the Plan is required.

Marine Protected Areas

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are intended to conserve Scotland’s marine biodiversity and help Scotland achieve its international commitments towards enhancing biodiversity. The network of MPAs is overseen by Marine Scotland, a Directorate of the Scottish Government. Marine Scotland work with NatureScot and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) which provide support on biodiversity features in the designation of an MPA.

There are several types of MPAs which make up Scotland’s MPA network which can be designated based on powers set out in the Marine Acts and the Conservation (Natural Habitats, &c.) Regulations 1994. The majority of MPAs (225 sites) are designated on the basis of conserving natural environmental features (termed Nature Conservation MPAs). Nature Conservation MPAs can be designated on the basis of conserving:

Flora or fauna

Marine habitats or ecosystems

Features of geological or geomorphological interest.

The designation of Nature Conservation MPAs is based on MPA search features which are informed by Priority Marine Features (PMFs) - a list of habitats of conservation priority including kelp beds, seagrasses and biogenic reefs.

Areas of the sea can also be designated as European sites as described in the previous section. Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) cover marine habitats including biogenic reefs, sand dunes and machair.