Brexit Statutory Instruments: Impact on the Devolved Settlement and Future Policy Direction

This briefing paper is the second in a series of three briefing papers on Brexit Statutory Instruments produced as part of a Scottish Parliament Academic Fellowship undertaken with the Scottish Parliament Information Centre . This second briefing paper examines the implementation of Protocol 1, the impact of UK Exit SIs on the devolution settlement, and who will set the future policy direction in Scotland in devolved areas.

Introduction

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 provides legislative continuity after Brexit by transforming EU law from a body of international law into a body of UK domestic law, known collectively as ‘retained EU law’, from 11pm on Implementation Period (IP) Completion Day, 31 December 2020. However, this retained EU law had to be amended to allow it to work effectively at the domestic level. In relation to Scottish devolved matters, these changes have either been made by the UK Government through Statutory Instruments laid at the UK Parliament with the consent of the Scottish Government (UK Exit SIs), or by the Scottish Government through Scottish Statutory Instruments (Exit SSIs) laid in the Scottish Parliament.

A new process was introduced to enable the Scottish Parliament to approve the Scottish Government giving its consent to the UK Government making UK Exit SIs on devolved issues. This was introduced by an agreement between the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament referred to as Protocol 1, which ran from September 2018 until IP Completion Day on 31 December 20201. This Protocol 1 process was replaced by an amended process introduced under Protocol 2, which has been in effect since 1 January 20212.

This briefing paper is the second in a series of three briefing papers on Brexit Statutory Instruments produced as part of a Scottish Parliament Academic Fellowship undertaken with the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) to explain and analyse the implementation of the Protocol 1 process. The purpose of these papers is to help inform the implementation of Protocol 2, and any other future processes by which scrutiny of UK SIs on devolved matters will be undertaken.

The first paper already published in this series3 outlined the processes by which retained EU law in areas of devolved competence was amended in the Scottish Parliament and the UK Parliament, including the Protocol 1 process.

This second briefing paper examines the implementation of Protocol 1, the impact of UK Exit SIs on the devolution settlement, and who will set the future policy direction in Scotland in devolved areas. It does so by analysing the following:

the implementation of the Protocol 1 process;

the extent to which UK Exit SIs have had an impact on current policy direction in Scotland;

the impact of the transfer of functions by UK Exit SIs on the devolution settlement and future policy direction in Scotland; and

the impact of the intersection of this process with common frameworks on the devolution settlement and future policy direction in Scotland.

The third briefing paper will highlight some of the challenges encountered in the implementation of Protocol 1 which, it is hoped, will assist the committees and MSPs in future scrutiny exercises under Protocol 2.

These papers recognise that both the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament had to respond to a situation that was not of their making or choosing. They have had to engage in the exceptionally complex task of correcting deficiencies in retained EU law on devolved matters. This process involved coordination between multiple governments and legislative bodies, but was initiated and led by the UK Government. The scale of the task was unprecedented, had to be performed in advance of Exit Day and other deadlines which transpired to be moveable, and had to incorporate changes in EU law during this time.

Implementation of the Protocol 1 process

Number and date of notifications

Under Protocol 1, the Scottish Government would notify the relevant Scottish Parliament lead subject committee of its intention to consent to the UK Government making a UK Exit SI to amend retained EU law on a devolved matter. The research underpinning this briefing paper series revealed several trends in the rate and frequency of notification and use of UK Exit SIs.

There was not a precise relationship between the number of notifications, proposed UK Exit SIs, and made UK Exit SIs. This is because sometimes: notifications introduced more than one proposed UK Exit SI, proposed UK Exit SIs were re-notified as the draft text was amended, proposed UK Exit SIs were not made, and content associated with a proposed UK Exit SI when notified might be divided across multiple UK Exit SIs when made. Some examples of this are provided in the third paper of this series.

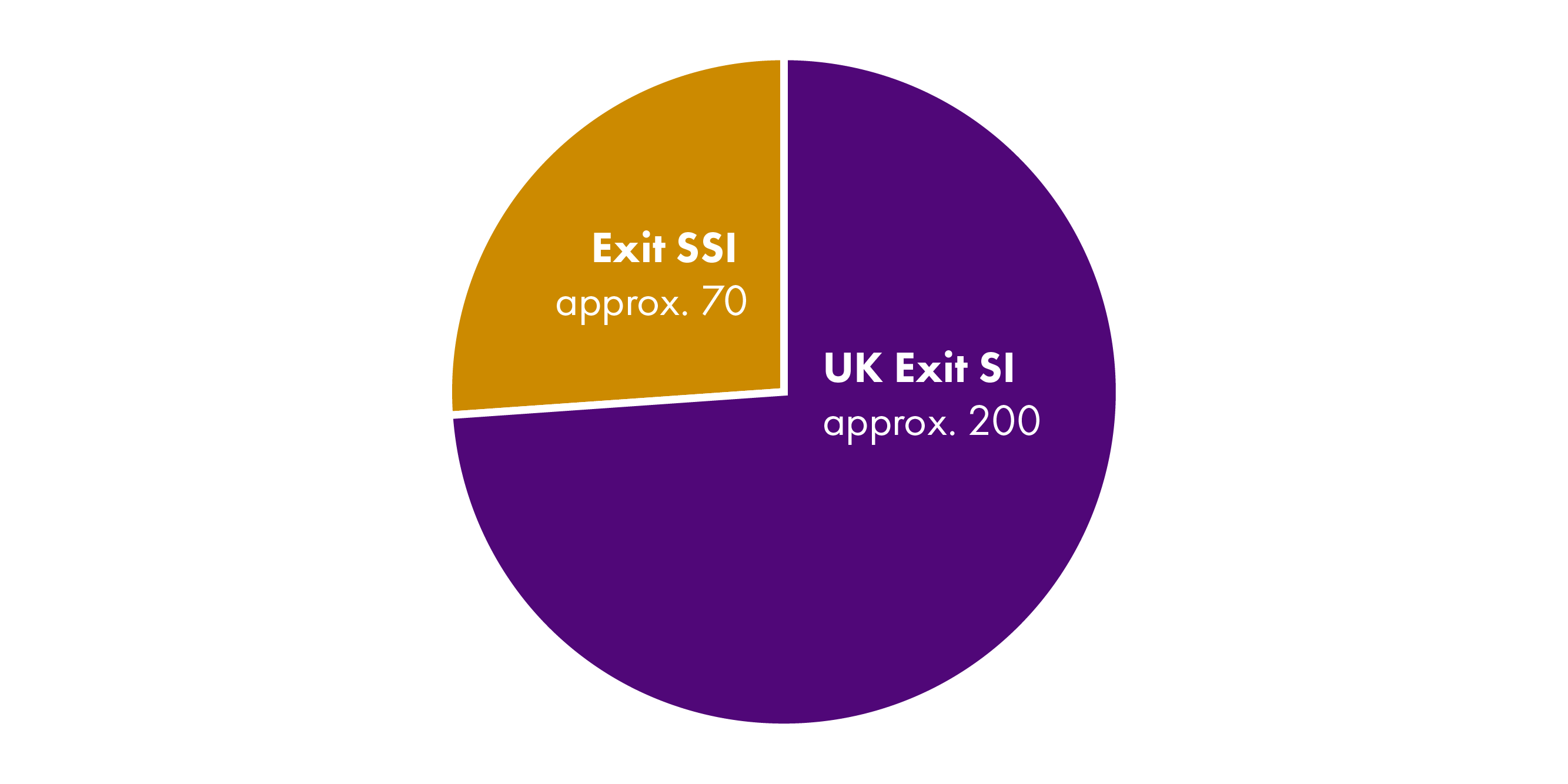

UK Exit SIs were the primary means by which retained EU law on devolved matters in Scotland was amended. Approximately 225 proposed UK Exit SIs were notified by the Scottish Government to the Scottish Parliament, although only approximately 200 UK Exit SIs were then subsequently laid by the UK Government. These laid UK Exit SIs involved devolved matters to at least some degree.

In comparison, approximately 70 Exit SSIs were made with reference to paragraph 1(1) of Schedule 2 of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act.i

This indicates that, as Figure 1 below shows, approximately three quarters of the secondary legislation passed to correct retained EU law on devolved matters were made by the UK Government rather than the Scottish Government.

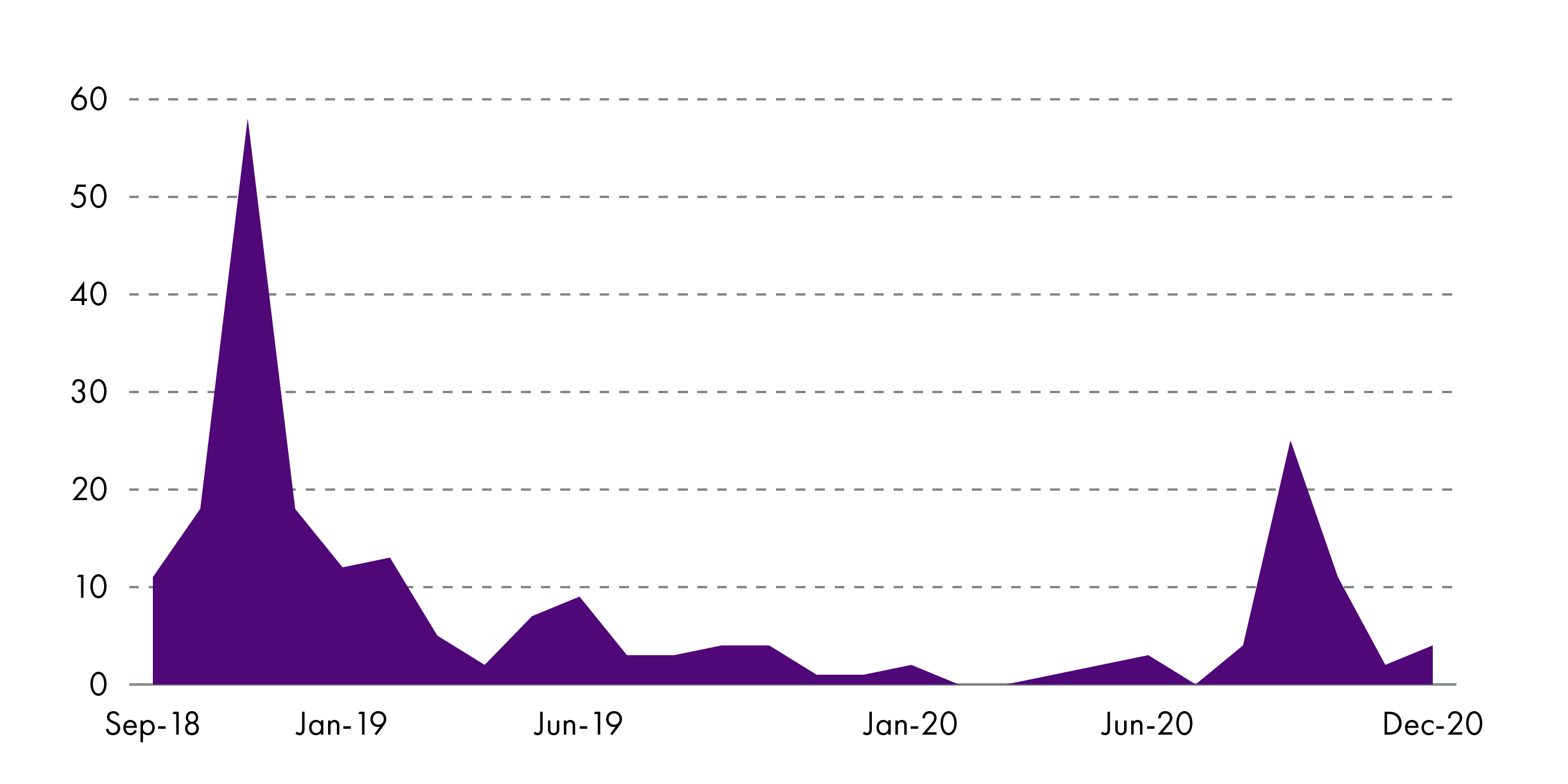

The rate at which proposed UK Exit SIs were notified changed over the Implementation Period or transition period, between September 2018 and IP Completion Day on 31 December 2020. The number and rate of proposed UK Exit SIs which were notified under Protocol 1 during this time is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 above clearly shows two peaks in the number of notifications over this time. The first and most significant was at the end of 2018, preparing for an anticipated ‘no deal’ Exit Day on 29 March 2019. New UK Exit SIs were proposed thereafter as a result of the repeated postponement of Exit Day throughout 2019. Following Exit Day on 31 January 2020, a second peak in the autumn of 2020 largely reflected adjustments to take account of the Withdrawal Agreement and Northern Ireland Protocol, in anticipation of IP Completion Day on 31 December 2020.

Categorisation

The first paper in this series1 explained that Protocol 1 required notifications of UK Exit SIs to be categorised according to the types of changes the legislation would make. Category A was for largely technical changes, category B was for changes with more significant impact on policy or the devolution settlement, and category C would indicate those areas which would be suitable for the joint laying process in both Parliaments. This categorisation was ‘to assist committees to prioritise scrutiny of more significant proposals’ and ‘to help committees target their scrutiny in a proportionate manner’.2 The implication was that this prioritisation was required because of the anticipated pressure of business in advance of deadlines such as Exit Day. Scottish Parliament officials have confirmed that this was additionally to balance scrutiny and available parliamentary time and resource.

The research underpinning this briefing paper series analysed the proportion of notifications which were classified under the different categories, with reference to lists of received notifications maintained by Scottish Parliament officials, as well as to the notifications themselves.

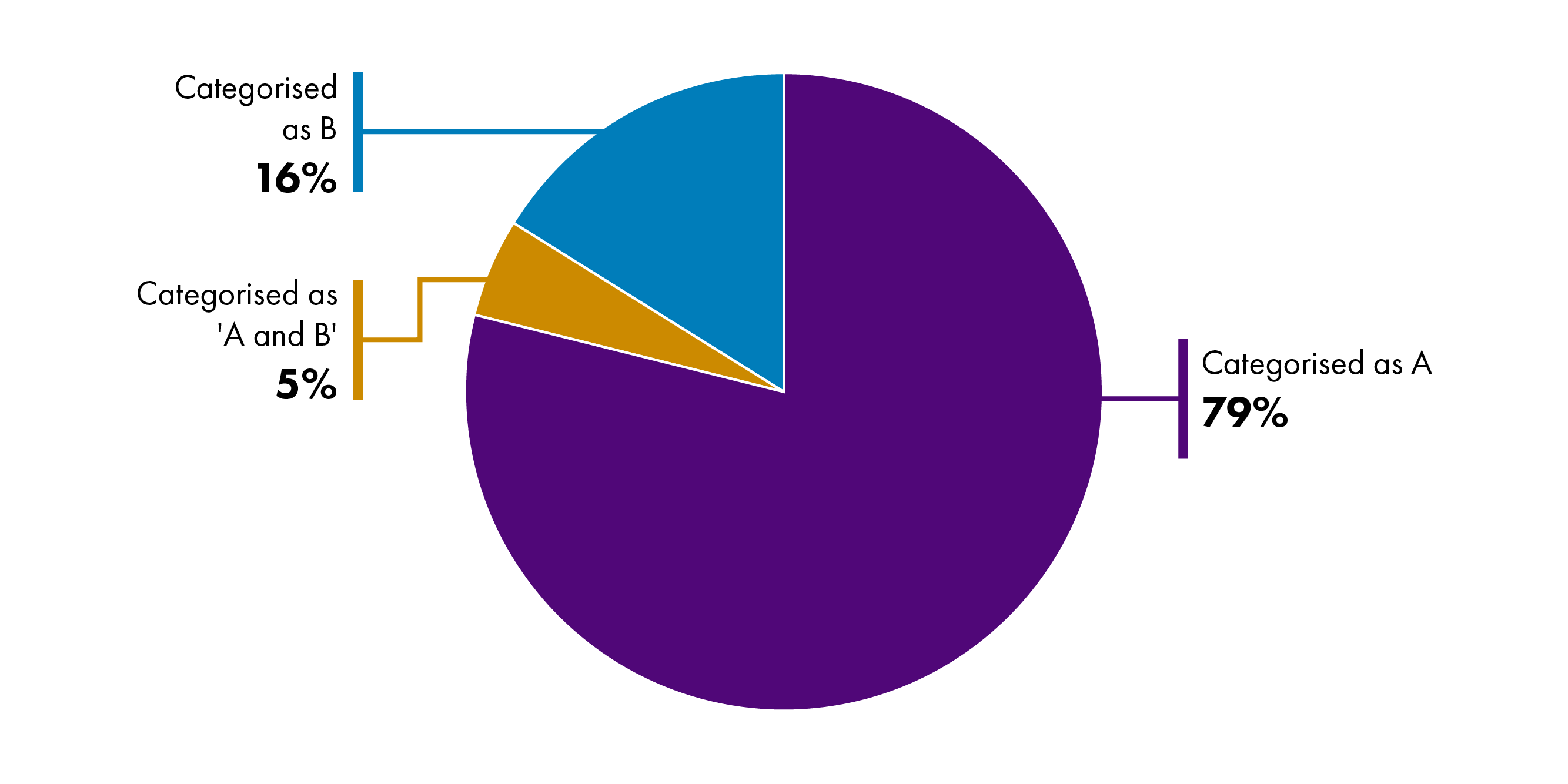

79% of proposed UK Exit SIs were notified as category A. The frequent categorisation of proposed UK Exit SIs as A reflects the ‘residual’ nature of this category. Another 16% of proposed UK Exit SIs were categorised as B. These were the UK Exit SIs which Protocol 1 anticipated would require closer scrutiny. No proposed UK Exit SIs were identified as category C, nor was any lead subject committee found by this research to have withheld approval on the basis that the joint procedure should be used instead, meaning this category remained unused in practice.

Although not anticipated under the process set out in Protocol 1, the remaining 5% of proposed UK Exit SIs were identified as ‘A and B’ because they reflected criteria associated with both of those categories. In such cases, specific aspects of the proposed UK Exit SI tended to be highlighted as A and others as B. Some examples are provided below.

The Common Fisheries Policy (Amendment etc) (EU Exit) (No 2) Regulations 2019 (notified 22 January 2019)3;

The Animals, Aquatic Animal Health and Seeds (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 20204, the Marketing of Seeds and Plant Propagating Material (Qualifying Northern Ireland Goods) (EU Exit) Regulations 20205, the Seeds (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 20206, and the Alien Species in Aquaculture, Animals, Aquatic Animal Health, Seeds and Planting Material (Legislative Functions and Miscellaneous Provisions) (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 20207 (notified together 30 September 2020);

The Chemicals (Health and Safety) and Genetically Modified Organisms (Contained Use) (Amendment etc) (EU Exit) Regulations 20208 (notified 28 September 2020).

However, normally, proposed UK Exit SIs with elements of both categories were simply categorised as B, with the more significant elements dictating the nature of the whole proposal as demonstrated below.

The Human Tissue (Quality and Safety for Human Application) (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 20189, the Quality and Safety of Organs Intended for Transplantation (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 201810 and the Blood Safety and Quality (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 201810 (notified together 28 September 2018).

The Scottish Government sometimes instead indicated that some proposed UK Exit SIs were A ‘in general’, so were simply categorised as A but with acknowledgement that an alternative categorisation of B might be arguable. Some examples of notifications adopting this approach is provided below.

The Rural Development (EU Exit) (Amendment) Regulations 201812, the Rural Development (Implementing and Delegated Acts) (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 201813, the Common Provisions (EU Exit) (Amendment) Regulations 201814, the Common Agricultural Policy (Direct Payments to Farmers) (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 201815, and the Common Agricultural Policy (Rules for Direct Payments) (Miscellaneous Amendments) (EU Exit) Regulations 201816 (notified together 21 November 2018);

The Common Agricultural Policy and Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (Amendment etc) (EU Exit) Regulations 201817 and the Common Provisions (Implementing and Delegated Acts) (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 201817 (notified together 15 November 2018);

The Direct Payments to Farmers (Amendment) Regulations 202019 and Financing, Management and Monitoring of Direct Payments to Farmers (Amendment) Regulations 202020 (notified together 23 January 2020).

The proportion of proposed UK Exit SIs in category A, B or the new hybrid category of ‘A and B’ are shown in Figure 3 below.

According to Protocol 1, any proposed UK Exit SI which would have an impact on the devolved settlement or future policy direction in Scotland should be categorised as a B. Some of these UK Exit SIs could have significant implications for the devolution settlement in terms of the future exercise of powers to make secondary legislation by the UK and/or Scottish Governments and changes in future policy direction in Scotland.

Committee remits and policy areas affected

The research underpinning this briefing paper series identified which policy areas were affected by the Protocol 1 process, based on the remits of the lead subject committees to which notifications were sent.

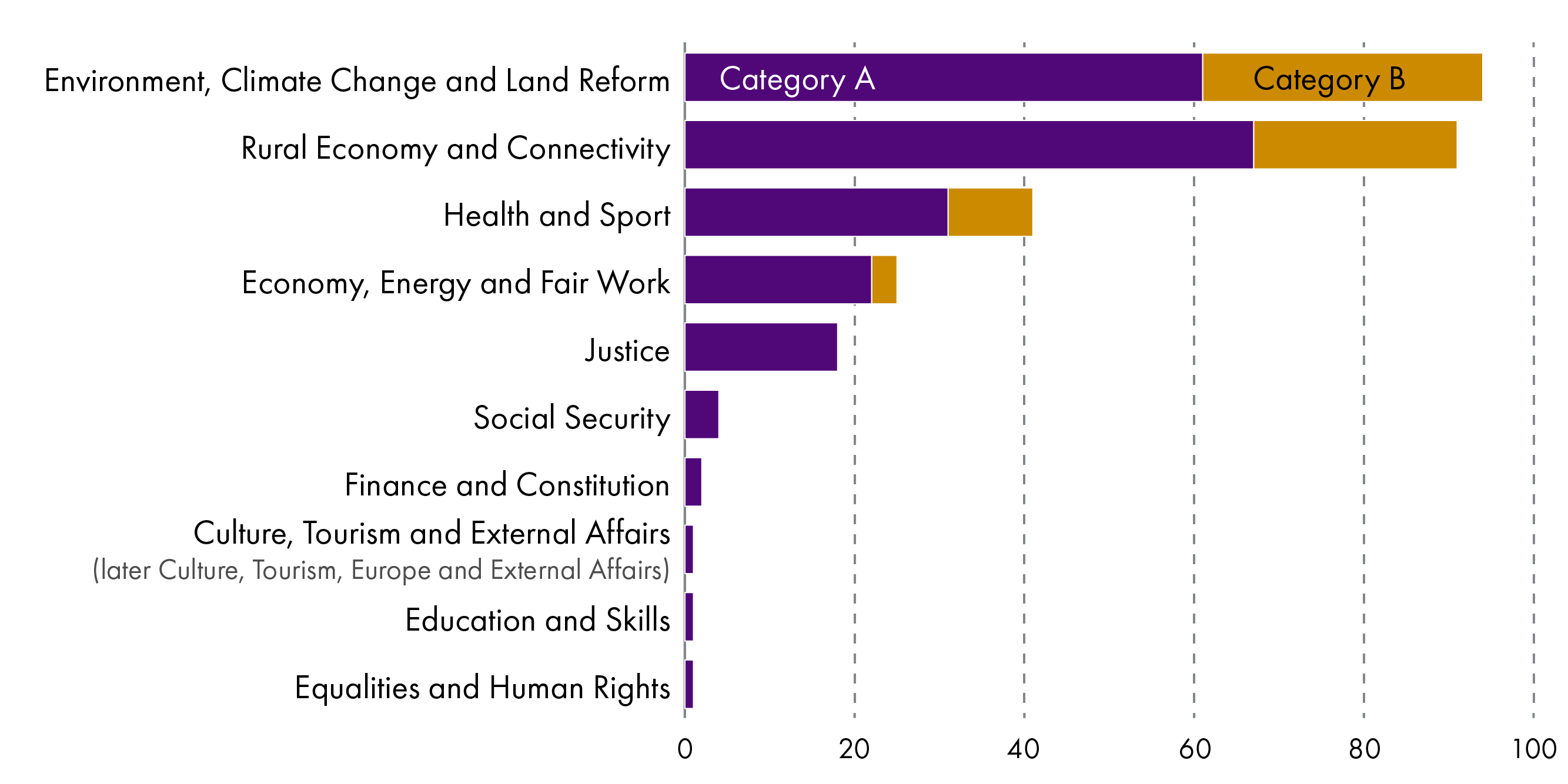

Figure 4 above shows the number of notifications which were received by each committee under Protocol 1, between September 2018 and 31 December 2020. Approximately 60 of the notifications were sent to more than one committee.

Not all committees received notifications, indicating that not all areas of devolved policy were affected by the exercise of the section 8 powers under the 2018 Act. The policy areas in which the most notifications were made were those within the remits of the Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee and the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee, each of which received almost 100 notifications.

Only four of the committees received notifications categorised as B: the Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee; the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee; the Health and Sport Committee; and the Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee.

While not all notifications resulted in secondary legislation being made, the remits of those lead subject committees which received notifications categorised as Bs are indicative of the policy areas where the devolved settlement and future policy direction may be the most affected.

Categorisation and changes in current policy direction

The research undertaken for this briefing paper analysed the reasons underpinning the categorisation of the short documents sent by the Scottish Government to the committees summarising the proposed change to retained EU law (‘notifications’). The first criteria identified in Protocol 1 for categorisation of a proposed UK Exit SI as either an A or a B depended on the extent of the policy change. This research found that these criteria were referred to in almost all notifications examined.

Protocol 1 specified that proposed UK Exit SIs could be categorised as A if they were to make ‘[m]inor and technical’ changes or simply ensured ‘continuity of law’. Protocol 1 stated that UK Exit SIs which included a policy change should be notified as A where it was ‘[c]lear there is no significant policy decision’, or ‘a minor policy change, but limited policy choice and an “obvious” policy answer’, or ‘a policy choice but with limited implications’.1

By contrast, Protocol 1 stated that notifications should be categorised as B if they included ‘a more significant policy decision ... being made by Scottish Ministers’ or were ‘predominantly concerned with technical detail but ... include[d] some more significant provisions that may warrant subject committee scrutiny’.1

Most notifications indicated that there was no significant policy change. Minor policy changes found in category A notifications included where, for example, the policy change would affect few people so would have limited implications in practice and therefore present ‘an obvious policy answer’.3 However, even among those category B notifications, only very rarely was a significant policy choice found to be explicitly acknowledged, such as where a new advisory committee was to be established,4 or because money for Scotland would be redistributed differently to how had been suggested in the recent Bew Review for farm support funding.5

However, this research found that there were different approaches taken by notifications in the identification of whether proposed UK Exit SIs which replaced one or more EU schemes with one or more UK schemes constituted a policy change. Sometimes these proposals were categorised as B because of the significance of the departure from the existing scheme(s),6 and sometimes the relevant UK Exit SIs were identified as Bs explicitly for other reasons.7 However, often proposed UK Exit SIs which introduced replacement schemes were categorised as A (see for example European Union Structural and Investment Funds] (EU Exit) Regulations 20188 notified 10 December 2018).

That key policy decisions within the context of replacement schemes might not be captured by the test of ‘policy changes’ is highlighted by the example of the Creative Europe Programme and Europe for Citizens Programme Revocation (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 (notified 16 January 2019). This proposed UK Exit SI would have replaced an EU cultural support scheme with payments from the UK Government but was categorised as A because it ‘does not involve any changes in policy’. However, when the UK Government made the policy decision to pay Scottish cultural institutions directly rather than via the Scottish Government, the Scottish Government withdrew its intention to consent because this ‘would be unprecedented and inappropriate to devolved competence’. The Scottish Government instead intimated its intent to use existing legislative frameworks to disburse the funds.9

Transfer of functions and impact on the devolved settlement and future policy direction

This research further analysed the extent to which functions were transferred through the Protocol 1 process, and the impact which these transfers could or did have on the devolved settlement and future policy direction in Scotland. This was examined because the transfer of functions was found to be the most frequently cited basis for categorisation as B. While the explicit basis of categorisation as B was not always made clear, it can be deduced that at least two-thirds of those proposed UK Exit SIs which were notified as Bs appear to have been classified on the basis of a transfer of functions (whether explicitly stating so or not).

The examination of the notifications revealed that UK Exit SIs considered under Protocol 1 frequently had to allocate functions which had previously rested with EU bodies to equivalent UK or Scottish bodies, and sometimes also created new functions.1

Protocol 1 appears to anticipate the transfer of two types of functions through UK Exit SIs: those which will be referred to in these briefing papers as ‘legislative functions’ (referred to in Protocol 1 as ‘sub-delegation’); and all functions which are not of a legislative nature, referred to in these papers and many UK Exit SIs as ‘administrative functions’.

The intended transfer of legislative functions through a proposed UK Exit SI always required categorisation of the notification as a B under Protocol 1. The notifications transferring such functions outlined an intention to confer powers on the Scottish Ministers and the Secretary of State to make secondary legislation.

‘Administrative functions’ were governmental or executive functions and/or responsibilities which are non-legislative in nature. Transfer of administrative functions would require categorisation as B where this included either ‘[r]eplacement, abolition, or modification of certain EU functions that have significant implications’ or ‘reporting (both receiving and making reports), monitoring, compliance and enforcement’, although these criteria were sometimes interpreted narrowly even where a large quantity of items of EU law were amended.i Transfer of administrative functions might also be categorised as B ‘where there is a policy choice with significant implications about which public authority it should be’ but could be an A where this was ‘consistent with the devolution settlement or replicates what happens in practice now’.3

This research found evidence of both legislative and administrative functions being transferred. However, only rarely was the transfer of administrative functions found to be the explicit basis for categorisation as B where legislative functions were not also transferred.ii

The transfer of functions will affect the devolved settlement and future policy direction in three ways:

First, it determines which Governments and/or bodies have functions in relation to the implementation of the law and its future reform.

Secondly, it determines who makes future policy decisions in some devolved areas.

Thirdly, it could affect the scrutiny role of the Scottish Parliament in relation to policy and legislative decisions in some devolved areas. Indeed, the lead subject committees raised concerns during their scrutiny of some notifications that they were being asked to approve the Scottish Government agreeing to the transfer of powers to the UK Government without knowing how, in the future, scrutiny of secondary legislation made at the UK Parliament using these transferred provisions could be secured.6

This impact could potentially be seen even where the UK Exit SI preserves current practice. A significant example is seen in the Trade in Animals and Animal Products (Legislative Functions) and Veterinary Surgeons (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019. The notification (dated 18 June 2019) clearly and accurately described the transfer of legislative functions under fifteen items of EU law. This included the power to publish lists on behalf of the EU, which previously rested with the Commission. The equivalent power to publish lists on behalf of the whole of the UK was transferred to the Secretary of State to exercise with the consent of Scottish Ministers and other devolved administrations.7 Despite this, the notification stated that it would ‘respect and protect the Scottish Ministers’ powers under the devolution settlement’ because ‘the lists in question are published and / or amended on a UK-wide basis’ under current practice. However, whereas this approach may preserve continuity of law and practice at present, ‘by ensuring that there are single lists for the whole of the UK, rather than lists of each constituent nation’, it is unclear to what extent the transfer of legislative initiative on these points to the UK Government will affect future policy direction and legal reform on otherwise devolved matters.

The subsections below will highlight the types of functions transferred and the recipients of these transferred functions. However, the full impact of the transfer of functions on the devolution settlement and future policy direction in Scotland are likely to remain unknown for some time. This is for two reasons.

Firstly, the functions transferred under the process only took effect after IP Completion Day, 31 December 2020, and most are yet to be exercised. The exercise of these functions will therefore need to be closely monitored for several years before the full impact of the process on the devolved settlement and future policy direction can be determined.

Secondly, despite the importance of the transfer of functions, there is ambiguity and complexity in the transfer of functions to both the UK and Scottish Governments during the process. The future role of the Scottish Ministers across all the relevant policy areas is therefore not entirely clear.

Ambiguity and complexity in the transfer of functions

The content of the notifications

As will be discussed in the third briefing paper in this series, the draft UK Exit SIs were not always provided to the Scottish Government, and were not generally made available to the lead subject committees when they were considering the notifications.

The notification itself was the principal document on which the committees’ scrutiny was based, and a copy would be included in the meeting papers. However, the lead subject committee would usually receive a briefing note from the Scottish Parliament’s Legal Services and SPICe, and a coversheet from the committee clerks. These notes provided basic information about the notification, an outline of the committee’s options, and wider advice, comments or concerns.i The lead subject committees could also seek clarification of points set out in the notification from the Scottish Government. Copies of any correspondence from the Scottish Government in response to such requests would also be provided to the committee members in meeting papers.ii

However, this research found that the notifications would not always have given a complete and accurate understanding of the transfer of functions.

Sometimes the notifications did not identify which specific body would receive the functions. For example, they might make references to functions being transferred to ‘existing Scottish regulators’ without making it clear which body or bodies that would be.3 Alternatively, sometimes the nature of the functions was unspecified. For example, the Floods and Water (Amendments etc) (EU Exit) Regulations 2018 (notified 5 November 2018) stated:

various provisions of the Directives place obligations on Member States, and those references are to be read as if they refer to the relevant authority currently responsible for that obligation; in the case of Scotland this will be Scottish Ministers or SEPA, whichever is appropriate.

In other cases, the functions were described by reference to examples,4 which might not provide the lead subject committee with a comprehensive understanding of the full number and range of functions being transferred. In such cases, the lead subject committees could and did seek clarification of the transfer of functions from the Scottish Government.5

The need to cross-reference between notifications in some cases added to the complexity of the task and also had the potential to create ambiguity. For example, four 2020 UK Exit SIs were notified together as needing to amend two earlier 2019 UK Exit SIs, which had themselves amended an EU Regulation (470/2009). The notification said that ‘various functions’ under the EU Regulation would be transferred to the Secretary of State, with no mention of whether those functions would only be exercisable with the consent of the Scottish Ministers.iii The notification directed the committee to the notifications for the two earlier UK Exit SIs to understand how the transfers would be made. However, checking those earlier notifications may not have made the position clear to committee members because one of the notifications said that relevant functions under that same Regulation could only be exercised with consent,11 while the other notification indicated that it ‘will not contain provision relating to the exercise of functions’.12 This example is further complicated because the latter notified UK Exit SI, when made, transferred various functions under the same EU Regulation to the Secretary of State which were exercisable without the consent.12 The cross-reference in the 2020 notification to these two earlier UK Exit SIs would therefore not provide a clear understanding of whether the functions would be exercisable only with consent.

Retained EU law

This research found that the nature of retained EU law adds complexity to understanding the transfer of functions through UK Exit SIs notified under the Protocol 1 process.

The 2018 Act transforms much of EU law into domestic law with effect from IP Completion Day. Such retained EU law includes a variety of different types of EU legislation, which is often subject to revision or reinterpretation by subsequent items of EU law. Changes to EU legislation by the UK Exit SIs were normally affected by replacing, revising or removing the wording of EU legislation, rather than by reissuing a complete and amended text. This would often include a transfer of functions previously exercised by EU bodies to UK or Scottish Ministers or other bodies. Amended sections of text were sometimes also subject to further revision by later UK Exit SIs. Understanding the nature and recipient of specific functions would therefore require cross-referencing between all relevant EU legislation and UK Exit SIs. There is not currently a publicly accessible database which provides access to the current, revised wording of retained EU law taking into account all of these changes.

A good example of these complexities is found in the Waste (Miscellaneous) Amendments (EU Exit) Regulations 2018, which was notified 9 November 2018. The notification indicated that numerous powers and functions of an unspecified nature would be transferred to the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), and some to local authorities, the Secretary of State or the Scottish Ministers. Only one of the functions transferred by the proposed UK Exit SI was categorised as B, specifically in relation to Regulation (EU) No 1103/2010 which is described in the categorisation discussion as transferred to the Scottish Ministers. However, this was identified as going to SEPA elsewhere in the notification. It would seem that this inconsistency can be explained by the wrong functions being listed as the category B function, but this may have resulted in confusion or increased complexity for the Committee seeking to scrutinise the transfer.

The Regulation (EU) No 1103/2010 was on Capacity Labelling of Portable Secondary (Rechargeable) and Automotive Batteries and Accumulators. In the made UK Exit SI, this transfer was implemented by adding text to an Annex of Regulation 1103/2010, which in turn modified two earlier EU Directives, 2006/66/EC and 2008/98/EC.1 The function was transferred to SEPA rather than the Scottish Ministers.

However, that function does not appear to have taken effect. Prior to IP Completion Day, the 2019 UK Exit SI’s revision to Regulation 1103/2010 was removed by a 2020 UK Exit SI: the Waste and Environmental Permitting etc (Legislative Functions and Amendment etc) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020.2 While the notification for that subsequent 2020 UK Exit SI mentioned the earlier 2019 UK Exit SI, it did so only in connection with other revisions and did not mention Regulation 1103/2010. It would therefore not have been clear that this function was being removed. Additionally, that proposed UK Exit SI was categorised as an A, despite amending a function which had previously been the basis for the 2019 UK Exit SI being categorised as a B.

This example confirms that understanding the transfer of functions might only be had by reference to multiple items of EU law in addition to the UK Exit SI, and subsequent UK Exit SIs which provided later amendments. It also provides a further example of the ambiguity which might arise in the notifications, discussed in the previous subsection.

This example also highlights the additional complexity of the process, with revisions to the law being made over a two-year period of time. This complexity over time was exacerbated as EU law changed during this period, introducing new functions. For example, a different proposed UK Exit SI had to be revised and re-notified without the legislation being laid to transfer a function to Food Standards Scotland to set ‘deadlines for particulars to be recorded in the wine register’ to reflect recent changes in EU law.i

Transfer of functions to the Secretary of State

This research found that many functions were transferred only to the UK Government’s Secretary of State by UK Exit SIs. Such functions, particularly legislative functions, were often to be exercised only with the consent of the Scottish Ministers. Consent was given for the following reasons:

to protect the devolved settlement.i

because the functions were already being exercised on a UK-wide basis, and therefore the transfer would reflect current practice. A significant example of such a transfer is seen in the Trade in Animals and Animal Products (Legislative Functions) and Veterinary Surgeons (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 (notified 18 June 2019), which transferred legislative functions under fifteen items of EU law to only the Secretary of State to exercise with the consent of Scottish Ministers on this basis.3

because there was a need for a UK-wide legislative framework or that separate legal solutions would be costly.4

There was also found to be less concern over the transfer of functions in areas which were thought to have limited practical relevance for Scotland. For example, legislative functions were consistently transferred to the Secretary of State in areas of devolved competence relating to wine because there was at that time no commercial wine production in Scotland.5

It was found to be uncommon for a legislative function to be transferred to the Secretary of State without the need for consent. In such cases, there is no explicit role for the Scottish Government or Scottish Parliament in the future exercise of these powers, even where the use of those powers would affect policy in Scotland.

For example, the Environment and Wildlife (Legislative Functions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 transferred legislative functions on a devolved matter to the Secretary of State without the need for consent, again because the regime ‘is currently governed and implemented on a UK-wide basis, the proposed corrections do not alter policy’.ii

Transfer of functions to the Scottish Ministers

This research further found that many functions were transferred to the Scottish Ministers, although their role in the exercise of some of these functions in the future remains unclear.

Many of the functions—and particularly legislative powers—were provided concurrently to both the Scottish Ministers and the Secretary of State.1 However, it was often unclear from the notifications how some of these functions would be exercised in practice. Rarely were the implications of the concurrent transfer of functions made clear.i Additionally, it was unclear how the Scottish Parliament would be able to scrutinise or provide consent or approval to any subsequent secondary legislation made by the UK Government using such concurrent powers.5

An explicit reason for providing concurrent powers was to enable the UK Government to introduce legislation to facilitate a UK-wide approach. This might include agreeing common frameworks within specific policy areas with the devolved administrations. For example, the notification for the Ozone-Depleting Substances and Fluorinated Greenhouse Gases (Amendment etc) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020 (notified 18 September 2020) indicated that the powers were to be exercisable by both the Scottish Ministers and the Secretary of State with the consent of the Scottish Ministers.ii It stated that:

These powers are limited to implementing aspects set out in the 2020 SI (e.g. specifying the format of labels) and enables a GB-wide approach that is underpinned by our shared obligations under the UN Montreal Protocol. Any changes to the fundamental approach would require alternative legislation (e.g. changing the phase down target). The 2020 SI does not bind Scottish Ministers and alternative provision could be made in future.

Sometimes the notifications indicated that legislative functions would be transferred such ‘that for devolved functions, in or as regards Scotland, it is only the Scottish Ministers who can carry out the function’.8 However, this was not always as straightforward as would first appear.

For example, the notification for the Common Fisheries Policy (Transfer of Functions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 outlined various legislative functions which would only be exercisable by the Scottish Ministers for Scotland. This included the ‘[p]ower to make regulations laying down a specific discard plan for a particular fishery’ under Article 15(6) of Regulation (EU) No 1380/2013. However, that proposed UK Exit SI did not proceed. This provision was instead included in the later Common Fisheries Policy and Aquaculture (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019.8 That UK Exit SI transferred the function to a ‘fisheries administration’ by revising Article 15 of the EU Regulation. However, the definition of a ‘fisheries administration’ was set down in a different UK Exit SI, the Common Fisheries Policy (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019.4 The powers under Article 15 of the EU Regulation were further revised subsequently, under the Common Fisheries Policy (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020.11

Administrative functions transferred to public bodies

In addition to administrative functions being transferred to the Scottish and UK Governments, it was found that some notifications indicated that administrative functions would also be transferred to other public bodies. Such public bodies included SEPA,1 local authorities,2 the Human Tissue Authority,3 the Health and Safety Executive,4 and Food Standards Scotland.5

Particularly notable instances of the transfer of administrative functions for the devolution settlement include the transfer of functions to a newly created public body,6 the transfer of functions from a Scottish to a UK public body,7 and the transfer of functions which previously rested with the Scottish Government to a UK Government agency.4

The intersection of UK Exit SIs with common frameworks

In October 2017, the UK Government and the devolved administrations agreed in a Communique to ‘work together to establish common approaches in some areas that are currently governed by EU law, but that are otherwise within areas of competence of the devolved administrations of legislatures’.1 Common frameworks were defined in the Communique as follows:

A framework will set out a common UK, or GB, approach and how it will be operated and governed. This may consist of common goals, minimum or maximum standards, harmonisation, limits on action, or mutual recognition, depending on the policy area and the objectives being pursued. Frameworks may be implemented by legislation, by executive action, by memorandums of understanding, or by other means on the context in which the framework is intended to operate.

The Communique further outlined the principles that would apply in the creation of these common frameworks. This included a commitment that any such frameworks would ‘be based on established conventions and practices, including that the competence of the devolved institutions will not normally be adjusted without their consent’.

This research has found that common frameworks intersect with UK Exit SIs, as will be explained in detail below. Common frameworks will also have a significant impact on future policy direction in Scotland, but the full extent of this impact will not be known until all common frameworks are agreed, published and implemented.

The Framework Analysis and categories of common frameworks

Three editions of a document called the Framework Analysis, published by the UK Government in March 2018, April 2019, and September 2020 respectively, have tracked the progress of the identification of which policy areas require a common framework. By the 2020 edition, the Framework Analysis had identified 154 policy areas of EU law which intersect with the devolved competence of at least one of the devolved administrations, and had placed those policy areas into one of three categories:i

Category 1: No further action areas

Category 2: Non-legislative areas

Category 3: Legislative areas

Between editions, the total number of policy areas and the number of policy areas in each category changed as areas were investigated by the UK Government and devolved administrations. Thus, for example, the number of category 1 policy areas increased from only 49 in 2018, to 63 in 2019, and then to 115 in 2020.ii

The 2018 edition of the Framework Analysis did not define what was meant by ‘non-legislative’ or ‘legislative’ areas. However, subsequent 2019 and 2020 editions provided more detail.

Category 1 areas require ‘no further action’. These areas are described as ‘[p]olicy areas where no further action is required to create a framework, and the UK Government and devolved administrations will continue to cooperate’.3 In other words, it includes those areas where ‘current working arrangements … [are] sufficient in the operation of the framework’.3

Category 2 or ‘non-legislative’ areas are defined as:

A non-legislative framework requires no new primary legislation to give effect to the governance arrangements for the framework or the policy environment in which it operates. Non-legislative frameworks may rely on secondary legislation, including retained EU legislation as amended by fixing SIs, but this does not constitute a legislative framework.3

Contrary to the name, therefore, UK Exit SIs form an integrated part of non-legislative common frameworks.

Category 3 areas are ‘legislative’ areas. This term identifies policy areas ‘where new primary legislation may be required (or has been put in place) in whole or in part, to implement the common rules and ways of working, alongside a non-legislative framework agreement and – potentially – a consistent approach to retained EU law’.3 However, the Framework Analysis indicates that the need for primary legislation might be avoided in some policy areas by reliance on secondary legislation:

For a number of [D]EFRA-related frameworks, the position is not yet clear on whether they will require, or will be impacted by, primary legislation. It is currently anticipated that most of these frameworks will not require new primary legislation (and can rely on secondary legislation instead), but until the outstanding issues are resolved they continue to be listed in the legislative category.3

Common frameworks therefore only need to be agreed for non-legislative (category 2) and legislative (category 3) policy areas. In the 2020 edition of the Framework Analysis, there are 40 policy areas identified as requiring a common framework (22 in category 2 and 18 in category 3). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, fewer common frameworks were agreed than initially anticipated by IP Completion Day on 31 December 2020.8Development of common frameworks has therefore continued into 2021.9

Implementation of common frameworks through the UK Exit SIs

The development of common frameworks has coincided with several other major Brexit-related developments, including the processes for passing UK Exit SIs under the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018. There is only limited recognition of common frameworks within the 2018 Act.1 However, as per the definitions of category 2 non-legislative frameworks discussed above, UK Exit SIs made under section 8 are nevertheless seen as central to delivering common frameworks. This appears to have been a long-standing understanding, if perhaps only in broad terms. Although the association was not explicitly mentioned in the 2018 edition of the Framework Analysis, the UK Government and the Welsh Government had previously agreed that secondary legislation would be used to create a ‘fully functioning statute book across the UK’,2 but that the UK Government would only exercise its section 8 powers with devolved consent.2

This research has found that UK Exit SIs were critical to establishing and delivering common frameworks in practice. It was common for the notifications of proposed UK Exit SIs to mention the broader context of common frameworks in general terms, although only very occasionally was a proposed UK Exit SI associated with a specific common framework or acknowledged as having a central role in delivering common frameworks.4

It appears that some UK Exit SIs can be associated with the creation of common frameworks, although they were made in advance of the common framework agreement itself being published. For example, a provisional outline agreement on the Food and Feed Safety and Hygiene common framework, published in November 2020, indicated that ‘there will be a common body of FFSH law in place across the UK, put in place in GB through the European Union Exit statutory instruments’ and that the framework policy would be implemented through a Concordant and Memorandum of Understanding.5Some of the relevant UK Exit SIs which had already been passed were listed in the Appendices to that provisional framework agreement. Similarly, the Ozone-Depleting Substances and Fluorinated Greenhouse Gases (Amendment etc) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020 was explicitly notified on 18 September 2020 as the basis of one of the common frameworks. When the Cabinet Secretary gave evidence on the UK Exit SI to the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee (ECCLRC), she indicated that the common framework agreement would take more time to resolve, so the legislation was being made in advance of the framework being ready.6

Indeed, it is notable that the Ozone-Depleting Substances and Fluorinated Greenhouse Gases (Amendment etc) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020 can be associated with a category 3 policy area, which would normally suggest the need for primary legislation to implement a common framework. However, the Cabinet Secretary indicated that the Governments were using secondary legislation where possible to expedite the process to ensure that the required amendments to retained EU law in these policy areas would be made in time for IP Completion Day. It was indicated by the Cabinet Secretary that this UK Exit SI would be the only legislation planned in this policy area for the foreseeable future, and therefore that ‘this particular instrument finish[ed] this framework’.6

Furthermore, the making of UK Exit SIs appears to have contributed to the process of policy areas being reclassified between editions of the Framework Analysis. One example of this is the ‘Marine Environment’ common framework progressing from a non-legislative policy area (category 2) in 2018 to requiring no further action (category 1) in the 2020 edition, with specific recognition that the issue was ‘[i]mplemented under Directives 2008/56/EC, 2017/845/EU’. In the intervening period, the Environment (Legislative Functions from Directives) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 and the Marine Environment (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2018 addressed various technical issues and introduced new legislative functions to Directive 2008/56/EC respectively. This evidence suggests that UK Exit SIs might contribute to a policy area being reclassified, potentially to no further action, which might have the effect of negating the need for a common framework agreement to be published in the future.

Conclusion

The first paper already published in this series1 outlined the processes by which retained EU law in areas of devolved competence was amended in the Scottish Parliament and the UK Parliament, including the Protocol 1 process.

This second briefing paper has examined the implementation of Protocol 1, the impact of UK Exit SIs on the devolution settlement, and who will set the future policy direction in Scotland in devolved areas.

With respect to the implementation of the Protocol 1 process, this briefing paper has shown that:

UK Exit SIs were the primary means by which retained EU law on devolved matters was amended;

the frequency of notifications being sent to the committees changed in anticipation of Exit Day and the postponement of Exit Day;

79% of proposed UK Exit SIs were categorised as A, 16% as B, and 5% as ‘A and B’;

the notifications and proposed UK Exit SIs which were categorised as B (and so which were identified by the Scottish Government as being of greater significance under Protocol 1’s criteria) fell within the remits of four committees: the Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee; the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee; the Health and Sport Committee; and the Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee.

On the extent to which the UK Exit SIs introduced policy changes, it has been shown that:

most policy changes were identified by the Scottish Government as ‘minor’ rather than ‘significant’;

different approaches were taken to whether the replacement of an EU scheme with a UK-based scheme constituted a ‘minor’ or a ‘significant’ policy change.

Regarding the transfer of functions, it has been shown that:

the transfer of functions was the principal reason for categorisation of a proposed UK Exit SI as a B under Protocol 1;

both legislative and administrative functions were transferred by UK Exit SIs;

the transfer of functions could be ambiguous and complex, owing to the content of the notifications and the nature of retained EU law;

it was common for functions to be transferred to the Secretary of State only. Often these functions could only be exercised in the future with the consent of the Scottish Ministers, but sometimes they will be legally exercisable without the consent of the Scottish Ministers;

it was common for functions to be transferred to the Scottish Government, sometimes concurrently with the Secretary of State, but it could be unclear how these concurrent powers would be exercised in practice;

administrative powers were also transferred to other public bodies.

Finally, with respect to common frameworks, this briefing paper has shown that:

UK Exit SIs were critical to the delivery of common frameworks, with some UK Exit SIs having formed the basis of common frameworks and others having had a role in the reclassification of policy areas under the Framework Analysis;

the relationship between UK Exit SIs and common frameworks was not always clear in the notifications.

The third briefing paper will highlight some of the challenges encountered in the implementation of Protocol 1 which, it is hoped, will assist the committees and MSPs in future scrutiny exercises under Protocol 2.