Income tax in Scotland: using the powers

The Scottish Parliament's powers in respect of income tax have increased over time. This briefing looks at how these powers have been used to develop income tax policy in Scotland. It also considers the impact these changes have had on the resources available for the Scottish budget and the impact on individual taxpayers and households.

Executive Summary

The powers of the Scottish Parliament in respect of income tax have increased over time. The current powers allow the Scottish Parliament to set rates and bands for non-savings, non-dividend (NSND) income tax. The Scottish Government has used these powers to implement changes to the Scottish income tax policy so that it now differs from the income tax policy in place in the rest of the UK (rUK).

Income tax is considered to be a partially devolved tax, rather than a fully devolved tax, because decisions on certain aspects on income tax remain the responsibility of the UK government. These include the taxation of any income from savings and dividends, and the setting of the level of allowances, including the personal allowance.

Scottish income tax policy first diverged from the rUK income tax policy in 2017-18. In this year, the rate at which the higher rate of tax became payable in Scotland was frozen at £43,000 whereas it was increased to £45,000 in rUK. Over subsequent years, further changes have been introduced, including two new tax bands (a "starter" and "intermediate" tax band) and changes to the higher and top rates of tax. Income tax policy in Scotland now looks quite different from that in place in rUK.

A 'Fiscal Framework' was agreed between the UK and Scottish governments to manage adjustments to the Scottish 'block grant' after the devolution of income tax powers. The UK government reduces the 'block grant' provided to the Scottish Government to reflect the fact that the Scottish Government now generates its own income tax revenues.

The Fiscal Framework is designed so that the amount deducted from the Scottish block grant should be the same as the amount raised in NSND income tax revenues if the Scottish Government keeps the same income tax policy as in rUK and income tax receipts per head grow at the same rate as in rUK. However, policy changes and/or differing economic performance will affect the final impact on the Scottish budget. In practice, over the last five years, changes in Scottish income tax policy have generated additional revenues for the Scottish Government, but these have been partially offset by less favourable growth in income tax per head in Scotland. The net result is that some of the additional spending power that would be implied by the Scottish Government's income tax policy choices has been offset by differential economic performance.

Over the three year period of income tax devolution for which actual tax receipts are known (2017-18 to 2019-20), the different income tax policy adopted by the Scottish Government has generated an estimated £900 million in additional revenues than would have been available if the Scottish Government had mirrored rUK income tax policy. That is, Scottish taxpayers have paid an estimated £900 million more in income tax than they would have if rUK income tax policy had been implemented in Scotland. This estimate is after taking account of any changes in taxpayer behaviour that might result from the changes in tax policy e.g. taxpayers working different hours or seeking to change the way in which they receive income.

However, the net effect on the Scottish budget over the same period is much smaller than £900 million. For the same period, the net benefit to the Scottish budget totals a much smaller £170 million. This represents the difference between the NSND income tax revenues generated and the adjustments to the Scottish block grant over the same period.

The Scottish Government budget has not seen the full impact of the differential tax policies due to differences in economic factors affecting the amount of tax that Scottish taxpayers have generated, such as differential wage growth, differences in the composition of the tax base and differences in the balance between taxpayers and non-taxpayers across the population. The gap between the £170 million budget impact and the £900 million impact on taxpayers reflects the risks inherent in tax devolution. Weaker growth in Scottish income tax receipts per head compared with rUK has meant that some of the revenue generated by the different income tax policy has been offset.

The policy changes have also had impacts on individual taxpayers and households. When compared with the rUK income tax policy, the 2021-22 Scottish income tax policy results in modest benefits of up to around £20 per year for those in the lower half of the earnings distribution (those earning below £27,000 per year). At a household level, the benefits for the poorest third of households are negligible (gains of less than 0.1% of household income).

However, the different income tax policy in Scotland has a much more significant impact on higher earners and richer households. Those earning more than £50,000 per year are paying over £1,500 more per year in income tax than they would be in rUK. The richest 10% of households have £1,800 less per year than they would if they were paying income tax according to the rUK policy.

What powers does the Scottish Parliament have in relation to income tax?

The powers of the Scottish Parliament in respect of income tax have increased over time. All income tax powers relate to non-savings, non-dividend (NSND) income. NSND income relates to earned income, which includes:

pay from employment

trading profits from self-employment and unincorporated businesses, such as partnerships

pensions (state, occupational and personal)

taxable benefits (e.g. Jobseeker's allowance)

income from property.

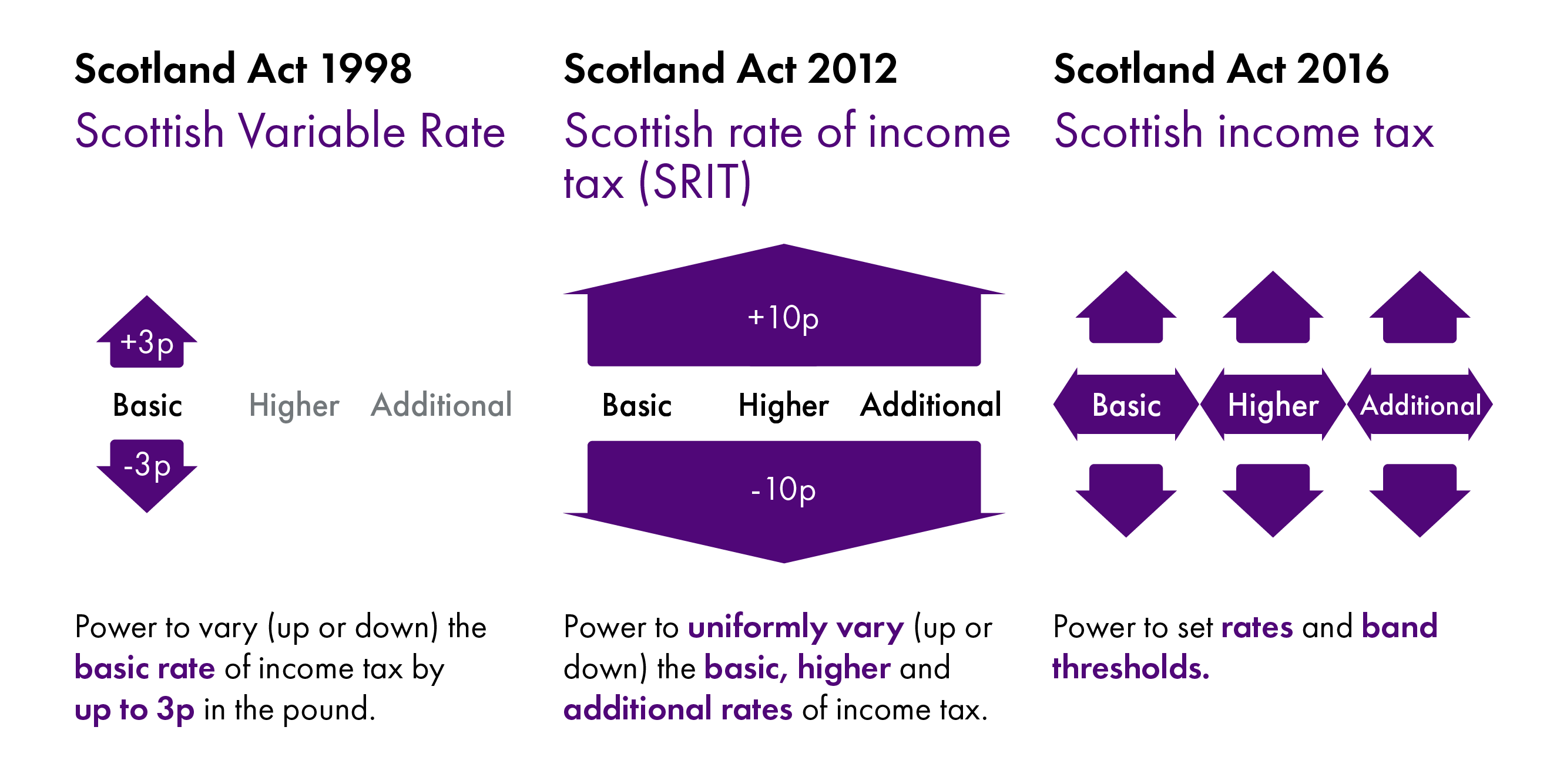

The Scottish Variable Rate

Under the terms of the Scotland Act 1998, the Scottish Parliament had the power to vary the basic rate of income tax by 3p in the pound (up or down). This power was never used and was replaced in 2016-17 by the Scottish Rate of Income Tax.

The Scottish Rate of Income Tax (SRIT)

The Scotland Act 2012 gave the Scottish Parliament the power to vary all three rates of income tax (basic, higher and additional) by up to 10p in the pound (up or down). This power was only in place for 2016-17 as it was superseded by Scotland Act 2016 (see Scottish Income Tax section). In 2016-17, the SRIT was set at 10p which meant that Scottish tax policy was identical to that of the rest of the UK (rUK). These powers were replaced in 2017-18 by Scottish Income Tax powers.

Scottish Income Tax

The Scotland Act 2016 introduced new income tax powers for the Scottish Parliament, which came into effect for the 2017-18 tax year. The new powers allow the Scottish Parliament to set rates and bands for non-savings, non-dividend (NSND) income tax. These powers have remained in place since 2017-18.

Reserved powers in respect of income tax

Some aspects of income tax policy remain reserved to the UK government, including:

taxation of income from savings and dividends

setting the level of allowances, including the personal allowance

defining taxable income

setting income tax reliefs, such as relief on pension contributions.

The fact that certain powers remain reserved to the UK Government mean that income tax is a partially devolved tax, rather than a fully devolved tax. HMRC continues to be responsible for the collection and management of income tax in Scotland, which includes the identification of Scottish taxpayers. The Scottish Income Tax collected by HMRC is paid to the Scottish Government.

Who pays income tax in Scotland?

Defining Scottish taxpayers

The definition of a Scottish taxpayer is set out in Scotland Act 2012 (section 25). The main criterion for establishing Scottish taxpayer status is that the individual meets at least one of the following conditions:

has a ‘close connection’ with Scotland

has no ‘close connection’ with Scotland but spends more days of that year in Scotland than in any other part of the UK

is an MP for a Scottish constituency, an MEP for Scotland or an MSP.

In most cases, establishing Scottish taxpayer status is straightforward and will depend on the individual's main residence. However, there is detailed technical guidance from HMRC for assessing more complex cases, which would include consideration of where an individual is registered for medical purposes, which address is used for bank accounts, where the individual is registered to vote etc.

HMRC is responsible for the identification of Scottish taxpayers. This has presented some challenges and, in its 2019-20 report on the Administration of Scottish Income Tax, the UK National Audit Office commented that:

Maintaining accurate and complete records of the Scottish taxpayer population continues to be the main challenge for HMRC in administering Scottish income tax.

National Audit Office. (2021, January 22). Administration of Scottish income tax 2019-20. Retrieved from https://www.nao.org.uk/report/administration-of-scottish-income-tax-2019-20/

HMRC has implemented several assurance processes to address these issues.

Characteristics of Scottish taxpayers

There are an estimated 2.5 million taxpayers in Scotland in 2021-22.1

| Tax band | Estimated number of taxpayers by highest rate paid | As % of all taxpayers |

| Starter rate (19%) | 246,000 | 10% |

| Basic rate (20%) | 1,053,300 | 42% |

| Intermediate rate (21%) | 818,100 | 32% |

| Higher rate (41%) | 387,100 | 15% |

| Top rate (46%) | 17,900 | 1% |

| Total | 2,522,400 | 100% |

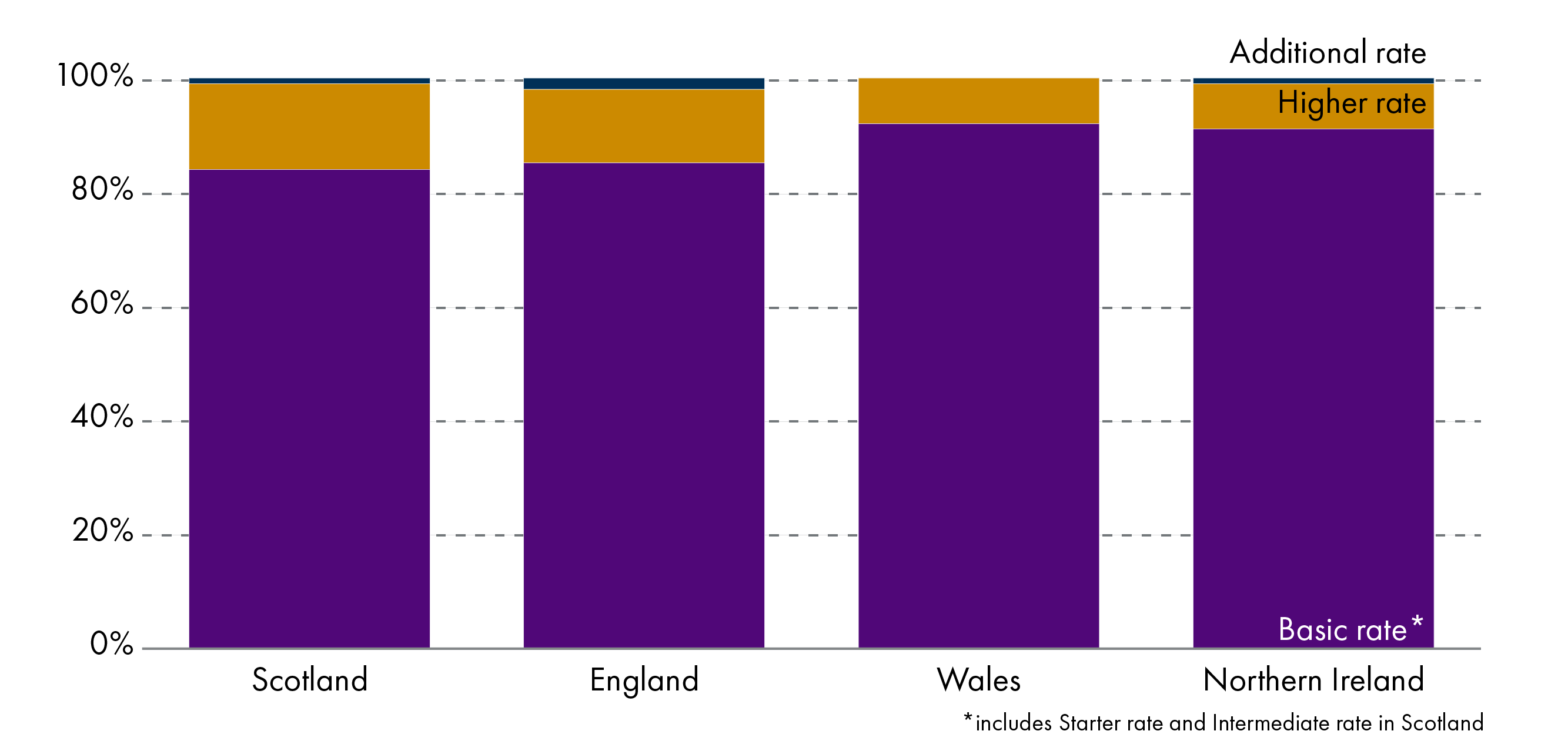

Direct comparisons with the rest of the UK (rUK) are affected by the different bands and thresholds in place in Scotland. However, HMRC publish data based on the thresholds in place in each jurisdiction. This comparison is shown in Figure 2 for England and the devolved administrations.

Scotland has the lowest share of taxpayers paying tax at the basic (or savers) rate. However, this will in part reflect the fact that the threshold for higher rate tax is lower in Scotland than in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (£43,662 compared to £50,270). This will also be a factor in the higher proportion of Scottish taxpayers paying tax at the higher rate of tax. The additional rate (or top rate in Scotland) threshold is £150,000 for all parts of the UK. Scotland has a lower share of taxpayers in this bracket than England. However, the proportion of additional rate taxpayers in Scotland is comparable to that in Northern Ireland and higher than the equivalent figure for Wales.

How has the Scottish Government used its income tax powers?

The Scottish Government's approach to taxation

The Scottish Government's approach to taxation is underpinned by four principles that were originally set out by Adam Smith in 'The Wealth of Nations':1

Proportionality – the tax system should be progressive, with those who are able to pay more tax contributing a greater share.

Certainty – individuals and businesses should have confidence in the tax system when making financial decisions.

Convenience – the tax system should be as simple as possible and easy to understand and comply with.

Efficiency – tax policy should be designed to ensure that it is cost-effective to administer.

The Scottish Government is also committed to:

taking a firm approach to tax avoidance (although acknowledges that its powers in this area in respect of income tax are limited as HMRC has primary responsibility).

engaging with stakeholders in regard to decisions on taxation.

These principles have been adopted by the Scottish Government in relation to all devolved (or partially devolved) taxes. In addition, the Scottish Government has set a further four tests specifically relating to decisions on income tax:1

Income tax policy should help maintain and promote the level of public services.

The lowest earning taxpayers should not see their taxes increase.

Any tax changes should make the tax system more progressive and reduce inequality.

Changes to income tax, along with decisions on spending, should support the economy.

Changes to income tax policy by the Scottish Government

In 2016-17, prior to the changes introduced by Scotland Act 2016, the UK (including Scotland) had a three band income tax policy:

Basic rate of 20% (payable on earnings between £11,000 and £43,000 in 2016-17)

Higher rate of 40% (payable on earnings between £43,000 and £150,000 in 2016-17)

Additional rate of 45% (payable on earnings over £150,000 in 2016-17).

The above thresholds applied to those in receipt of the standard UK personal allowance (£11,000 in 2016-17). Those earning more than £100,000 have their personal allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000. This is a policy set by the UK Government and has remained unchanged since 2016-17.

Since 2016-17, the Scottish Government has used its powers in relation to income tax to make changes to income tax policy in Scotland, introducing changes to both the rates and bands. As a result, Scottish tax policy now differs from that in the rest of the UK (rUK). The changes made in each successive budget are set out below. The analysis that follows compares the Scottish income tax policy in the given year with the rUK income tax policy for that same year.

The Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) - which is responsible for producing official forecasts for Scotland - present costings of income tax policy decisions alongside each Scottish budget. Note that the SFC's baseline assumption (the "default" policy) is that all income tax bands will increase in line with inflation. Therefore, for the SFC's costings a decision to increase all income tax bands in line with inflation would be considered a revenue neutral policy. In the analysis below, no such assumptions have been made about a default policy position, so this approach differs from the SFC, with any changes to tax bands considered to have an impact on revenues.

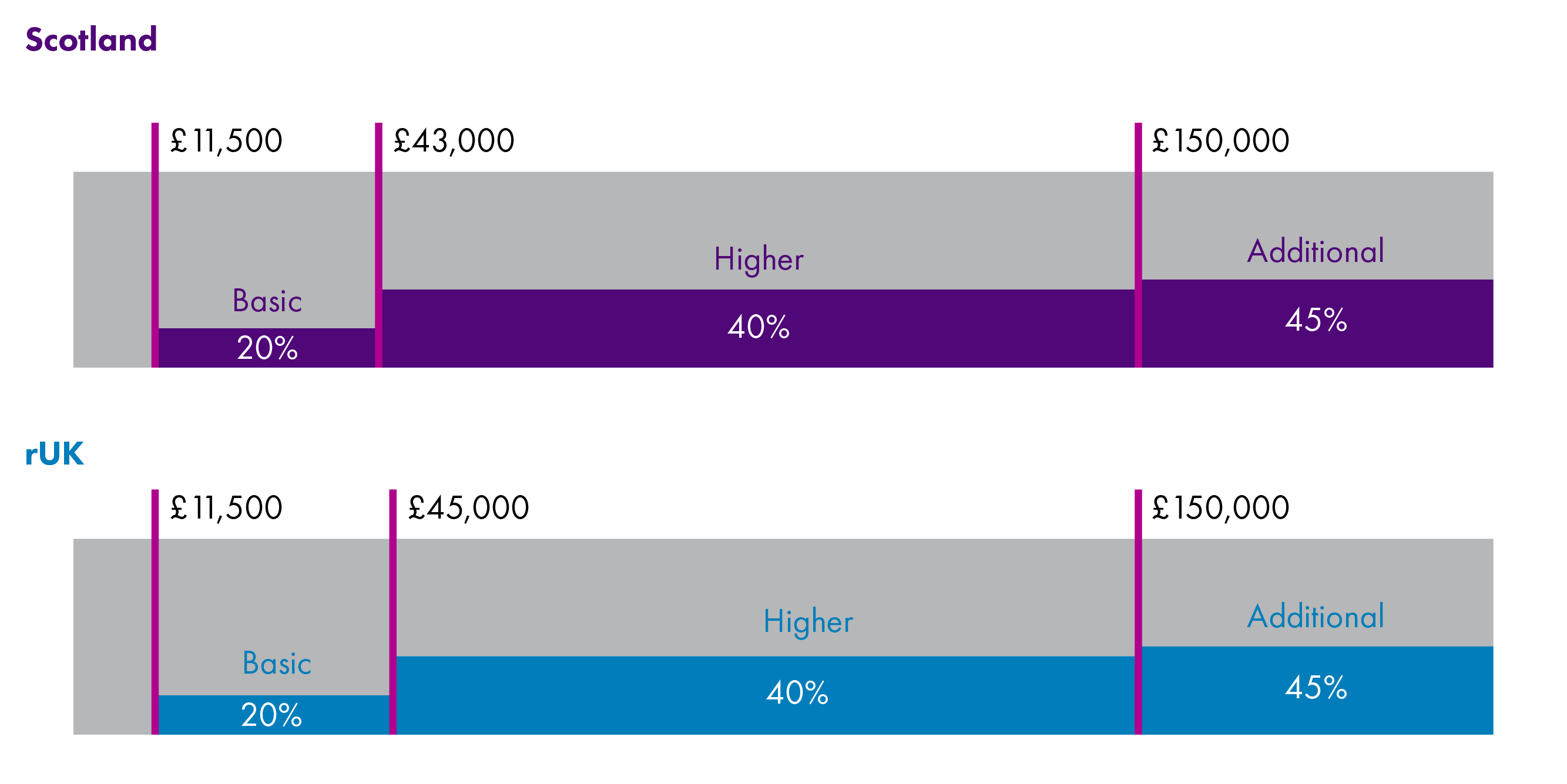

2017-18 budget

In its 2017-18 Draft Budget, the Scottish Government proposed to retain a three band income tax structure, similar to that of the rest of the UK. However, the Scottish Government proposed a lower increase in the higher rate threshold than the UK Government i.e. the rate at which 40% tax became payable. The UK Government was proposing lifting the higher rate threshold to £45,000 (a 4.7% increase), while the Scottish Government proposed lifting the higher rate threshold to £43,430 (a 1% increase).

However, during the budget negotiations which preceded the Scottish Budget Act being passed by the Scottish Parliament, the Scottish Government made an agreement with the Scottish Green Party to freeze the higher rate threshold at £43,000. The tax policy agreed by Parliament in February 2017 is set out in Table 2.

| Band | Band name | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Over £11,500* – £43,000 | Basic | 20 |

| Over £43,000 – £150,000 | Higher | 40 |

| Over £150,000 and above** | Additional | 45 |

*Assumes individuals are in receipt of the Standard UK Personal Allowance.

**Those earning more than £100,000 will see their Personal Allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000.

Figure 3 compares the 2017-18 Scottish income tax policy with that of the rest of the UK.

SPICe modelling (using UKMOD) suggests that this policy resulted in NSND income tax revenues in Scotland being £130 millionhigher than would have been the case if the Scottish Government had chosen to replicate rUK income tax policy.

This is before taking account of any behavioural changes in response to the change in tax policy. The Scottish Government estimate that after taking account of behavioural changes, the policy resulted in revenues of around £110 million compared to a position where the rUK income tax policy had been implemented.1Behavioural impacts are discussed further below.

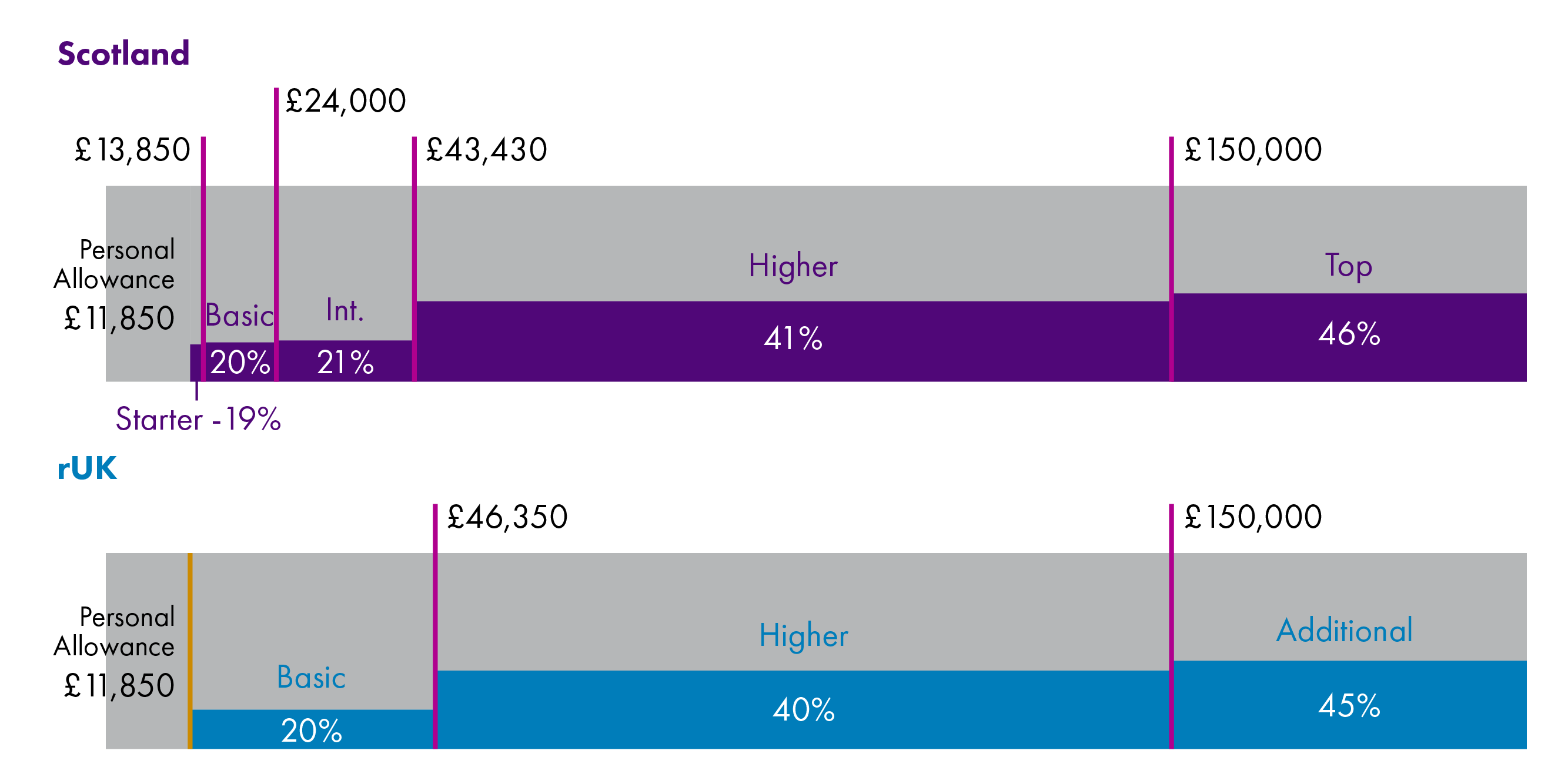

2018-19 budget

In the 2018-19 budget, the Scottish Government proposed a more radical diversion from rUK income tax policy and put forward proposals for a five-band income tax policy. This policy:

introduced two extra bands with tax rates of 19% and 21%

raised the higher tax rate to 41%

raised the additional tax rate (now called the "top" tax rate) to 46%.

The Scottish Government's initial proposals included a higher rate threshold of £44,273 but during budget negotiations, this was reduced to £43,430 in order to secure the support of the Scottish Green Party. This change was intended to bring more income tax payers into the higher rate bracket, and increase forecast income tax revenues. These proposals were accepted by the Scottish Parliament in February 2018 and are set out in Table 3.

| Band | Band name | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Over £11,850*-£13,850 | Starter | 19 |

| Over £13,850-£24,000 | Basic | 20 |

| Over £24,000-£43,430 | Intermediate | 21 |

| Over £43,430-£150,000** | Higher | 41 |

| Above £150,000** | Top | 46 |

*Assumes individuals are in receipt of the Standard UK Personal Allowance.

**Those earning more than £100,000 will see their Personal Allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000.

Figure 4 compares the 2018-19 Scottish income tax policy with that of the rest of the UK.

SPICe modelling suggests that this policy resulted in NSND income tax revenues in Scotland being £390 millionhigher than would have been the case if the Scottish Government had chosen to replicate the 2018-19 rUK income tax policy. After taking account of behavioural effects, the Scottish Government estimate that the policy generated revenues of around £300 million.1 The Scottish Government intend to publish a more detailed evaluation of this policy in Summer 2021.1

2019-20 budget

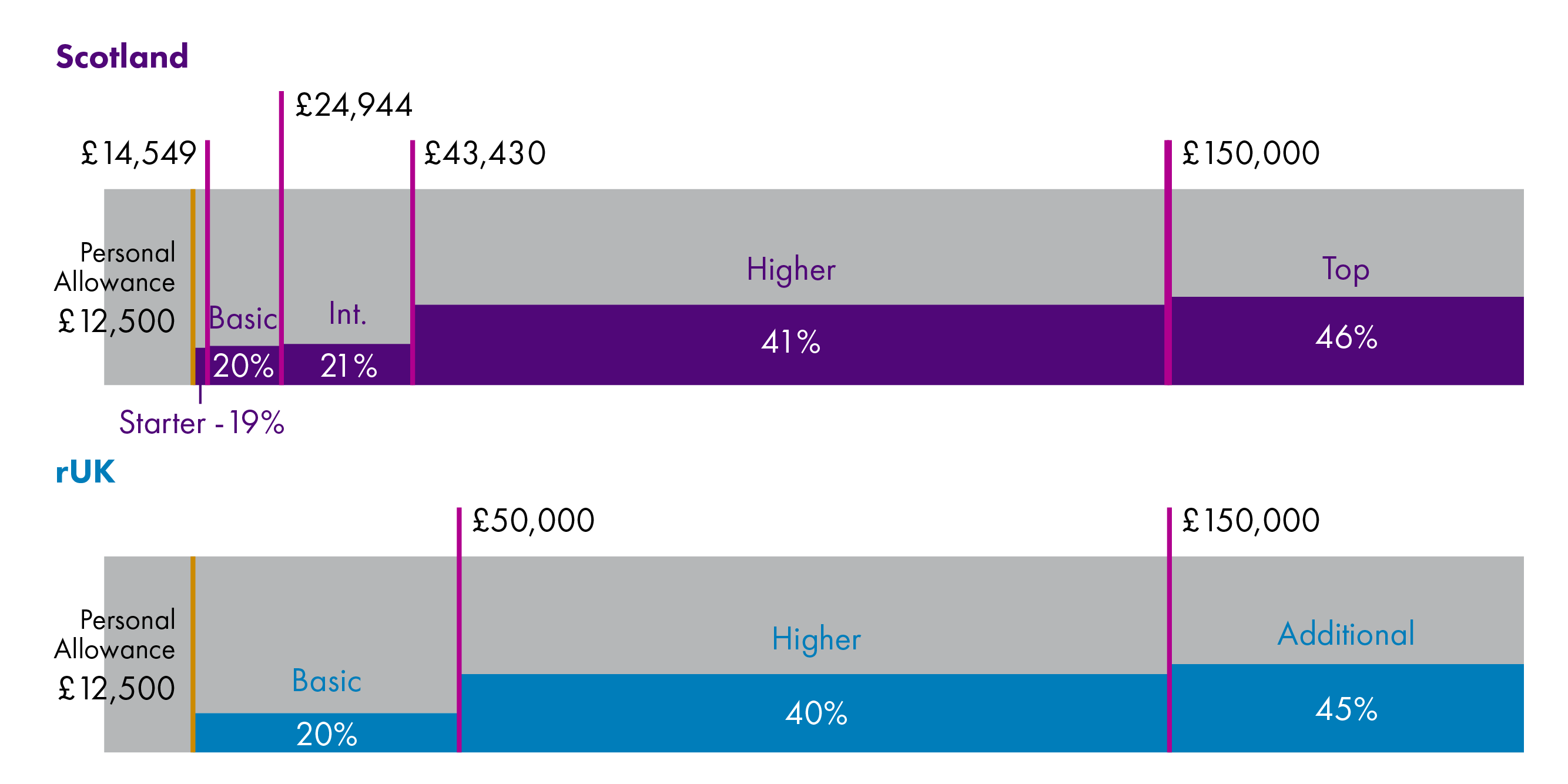

The Scottish Government's 2019-20 budget proposed relatively minor changes to the income tax policy, compared with the previous year. The UK Government increased the personal allowance to £12,500 and the Scottish Government set out proposals to increase the various thresholds for the five bands of income tax, as set out in Table 4.

The proposals, which were agreed by Parliament, represented:

A 5% increase in the threshold for the basic rate and a 4% increase in the threshold for the intermediate rate

No change in the higher rate threshold or top rate threshold, which remained at £43,430 and £150,000 respectively.

The increases to the basic rate and intermediate rate thresholds were above inflation, but had the effect of ensuring that the amount of income at which starter rate tax and basic rate tax is paid increased in line with inflation. For example, in 2018-19, the first £2,000 of taxable income was taxed at 19%. Under the 2019-20 policy, the first £2,049 is taxed at 19%. The increase in the band from £2,000 to £2,049 represented an inflationary increase of 2.5%.

The 2019-20 income tax policy meant that the gap between the higher rate thresholds in Scotland and rUK widened. The higher rate threshold in rUK increased to £50,000 from April 2019, which is £6,570 higher than the equivalent threshold for Scotland.

No changes were made to the tax rates for the five bands, which remained the same as in 2018-19.

| Band | Band name | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Over £12,500* - £14,549 | Starter | 19 |

| Over £14,549 - £24,944 | Basic | 20 |

| Over £24,944 - £43,430 | Intermediate | 21 |

| Over £43,430 - £150,000** | Higher | 41 |

| Above £150,000** | Top | 46 |

*Assumes individuals are in receipt of the Standard UK Personal Allowance.

**Those earning more than £100,000 will see their Personal Allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000

Figure 5 compares the 2019-20 Scottish income tax policy with that of the rest of the UK.

SPICe modelling suggests that this policy decision resulted in NSND income tax revenues in Scotland being around £620 millionhigher than would have been the case if the Scottish Government had chosen to replicate the 2019-20 rUK income tax policy. After taking account of any behavioural effects, the Scottish Government estimated that the policy generated revenues of around £500 million compared with the revenues that would have been generated with the rUK policy.1

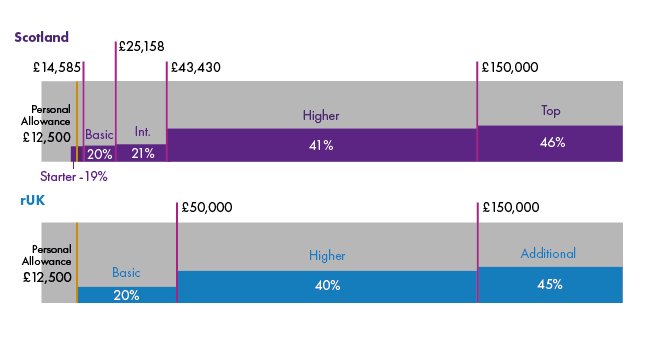

2020-21 budget

The changes to income tax policy in 2020-21 were modest, incorporating:

A 0.2% increase in the threshold for the basic rate

A 0.9% increase in the threshold for the intermediate rate

No change in the higher rate threshold or top rate threshold

The increases to the basic rate and intermediate rate thresholds were below inflation, but had the effect of ensuring that the amount of income at which starter rate tax and basic rate tax is paid increased in line with inflation. For example, in 2019-20, the first £2,049 of taxable income was taxed at 19%. Under the 2020-21 policy, the first £2,085 was taxed at 19%. The increase in the band from £2,049 to £2,085 represented an inflationary increase of 1.7%.

| Band | Band name | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Over £12,500* - £14,585 | Starter | 19 |

| Over £14,585 - £25,158 | Basic | 20 |

| Over £25,158 - £43,430 | Intermediate | 21 |

| Over £43,430 - £150,000** | Higher | 41 |

| Above £150,000** | Top | 46 |

*Assumes individuals are in receipt of the Standard UK Personal Allowance.

**Those earning more than £100,000 will see their Personal Allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000

Figure 6 compares the 2020-21 Scottish income tax policy with that of the rest of the UK.

SPICe modelling suggests that in 2020-21, the Scottish Government's income tax policy will have generated around £620 million more than would have been the case if the rUK income tax policy had been implemented in Scotland. After taking account of any behavioural effects, the Scottish Government estimated that the policy would have raised £460 million more than if the rUK income tax policy had been in place.1

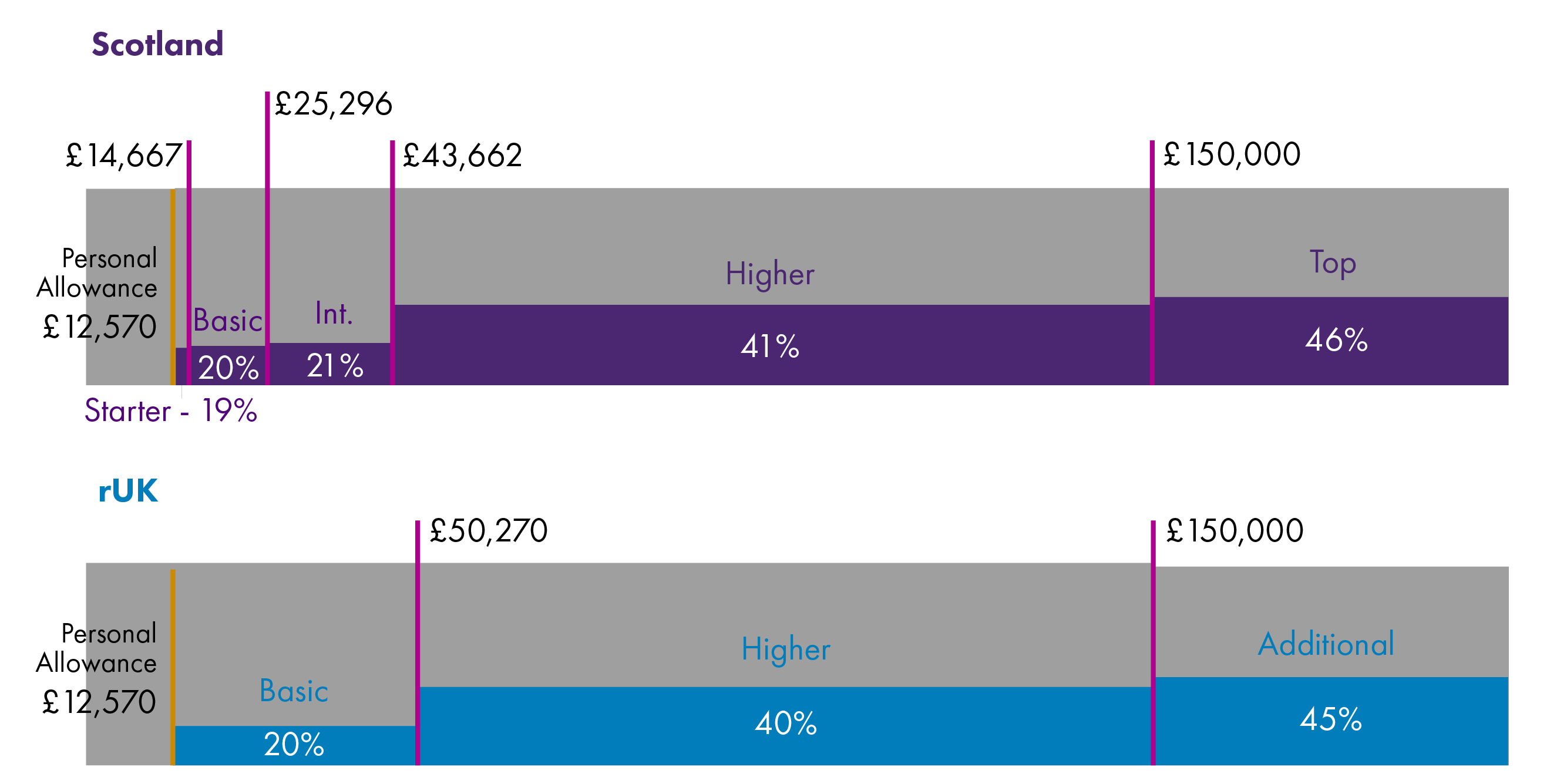

2021-22 budget

Very minor changes were introduced by the 2021-22 budget, with no changes to the rates and all thresholds other than the top rate threshold increasing by 0.5% (CPI inflation as at September 2020).

The SNP’s manifesto for the 2016 Scottish election had included a commitment to implement an “effective personal allowance” of £12,750. The Scottish Government is not able to change the personal allowance as this is reserved to the UK government, but the Scottish Government had intended to make changes that would have had the same effect as increasing the personal allowance to £12,750. This would have been achieved by introducing a zero rate tax band between the UK personal allowance (£12,570) and £12,750. The Fraser of Allander Institute estimate that this would have cost more than £80 million.1 However, the Scottish Government stated that it had decided not to do this due to the “unprecedented circumstances” brought about by the coronavirus pandemic.2

| Band | Band name | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Over £12,570* - £14,667 | Starter | 19 |

| Over £14,667 - £25,296 | Basic | 20 |

| Over £25,296 - £43,662 | Intermediate | 21 |

| Over £43,662 - £150,000** | Higher | 41 |

| Above £150,000** | Top | 46 |

*Assumes individuals are in receipt of the Standard UK Personal Allowance.

**Those earning more than £100,000 will see their Personal Allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000

Figure 7 compares the 2021-22 Scottish income tax policy with that of the rest of the UK.

SPICe modelling suggests that the Scottish Government's income tax policy is likely to result in NSND income tax revenues of around £670 million more than would have been the case if the rUK income tax policy had been in place in Scotland. Scottish Government estimates for previous years suggest that behavioural responses reduce estimated revenues by between 15 and 25%. On this basis, estimated post-behavioural revenues for this policy (compared with the rUK income tax policy) would be in the range £500-570 million.

Impact of the Scottish income tax policy on the Scottish budget

The Scottish Government's decisions in successive years to diverge from rUK income tax policy have resulted in greater resources for the Scottish budget than would otherwise have been the case. However, the additional resources available are influenced by the operation of the Fiscal Framework agreed between the UK and Scottish governments.1 The amounts available to the Scottish Government to support its budget are not simply the difference between the amount generated by the Scottish income tax policy relative to the UK income tax policy, for the reasons outlined below.

The estimated additional amounts generated by the Scottish Government's income tax policy choices, compared with the revenues that would be generated by the rUK policy in that year, are set out in Table 7. Over the five-year period shown, estimated NSND income tax revenues total £2.4 billion more than would have been the case if Scotland had mirrored the rUK policy. After taking account of behavioural changes, the additional revenues are estimated at £1.9 billion.

| Year | Estimated additional revenues (before behavioural adjustment) £m | Estimated additional revenues (after behavioural adjustment) £m |

|---|---|---|

| 2017-18 | 130 | 100 |

| 2018-19 | 390 | 300 |

| 2019-20 | 620 | 500 |

| 2020-21 | 620 | 460 |

| 2021-22 | 670 | 500-570 |

| Total | 2,420 | 1,870-1,940* |

* no comparable figure for 2021-22 has been published by the Scottish Government; estimate is based on the 15-25% adjustment implied by post-behavioural figures for earlier years

However, it would not be correct to say that the Scottish Government has had an additional £1.9 billion to spend in its budgets over the years. This is because of the operation of the Fiscal Framework.1

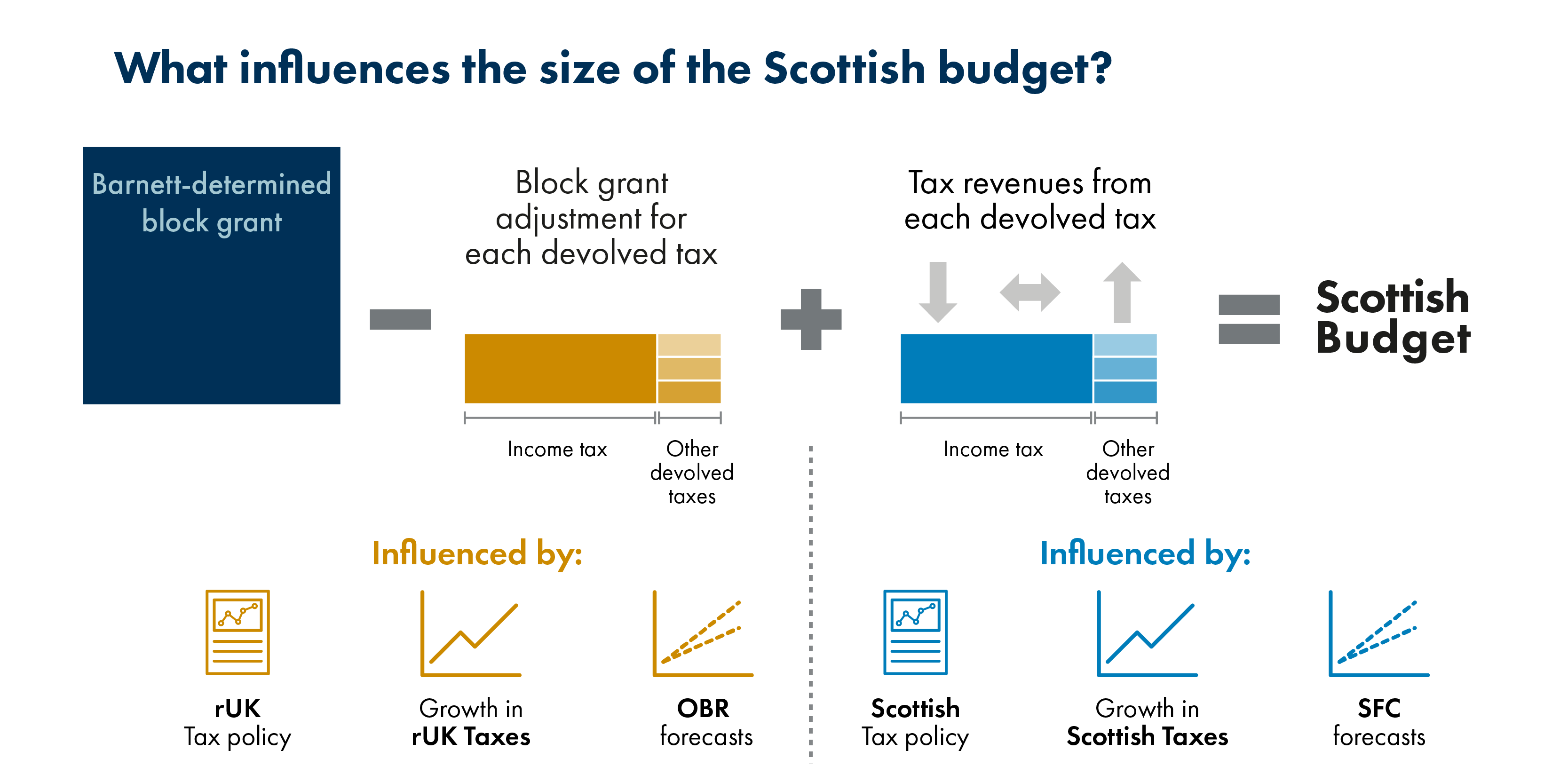

The Fiscal Framework sets out the method for adjusting the Scottish budget to account for the fact that certain taxes are now set and raised in Scotland, including income tax. It also adjusts (in the other direction) for the fact that the Scottish Government now has responsibility for the payment of certain devolved benefits.

The UK government reduces the 'block grant' provided to the Scottish Government to reflect the fact that the Scottish Government now generates its own income tax revenues. Similarly, the UK government increases the block grant to reflect the fact that the Scottish Government now has responsibility for the payment of certain benefits.

In respect of income tax, the block grant is adjusted downwards by an amount which equates to the amount of income tax that would have been raised in Scotland if Scottish income tax policy had not diverged from rUK tax policy and income tax receipts per head had grown in line with rUK income tax receipts per head. Implicitly, the block grant adjustment is set at a level to ensure the Scottish budget is no worse off if the Scottish Government retains the same policy as rUK and its tax revenues (per capita) change at the same rate as in rUK.

In reality, however, the Scottish Government has chosen to adopt different income tax policies. Also, rates of growth of per capita income tax revenues have differed. Both of these factors influence the net impact on the Scottish budget. Furthermore, as budgets are set on the basis of forecast tax revenues for the forthcoming tax year, the available budget will also depend on two sets of forecasts - those for Scotland (set by the Scottish Fiscal Commission) and those for rUK (set by the Office for Budget Responsibility).

The diagram below illustrates the various factors influencing the Scottish budget. Note that this diagram only reflects the tax side of the equation. In reality, adjustments will also be made in respect of benefits.

Source: SPICe

As the visual above illustrates, the net impact on the Scottish budget (in respect of income tax) is influenced by a number of factors:

the income tax policy decisions of both governments

growth in Scottish income tax receipts per head relative to growth in rUK income tax receipts per head

differences in forecasts made by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) and the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) - although over time any differences between these forecasts and the actual data are corrected for through adjustments ("reconciliations") to the budgets in later years.

Leaving aside differences in forecasts (which are ultimately corrected for), if the Scottish Government had decided to replicate rUK income tax policy and Scottish income tax receipts per head had grown in line with rUK income tax receipts per head, then the amount subtracted from the block grant would have been exactly offset by the income tax revenues raised. There would have been no net effect on the spending power of the Scottish Government.

However, in reality:

the Scottish Government has adopted a different income tax policy from rUK (which has generated additional revenues)

income tax revenues per head have grown at different rates, reflecting:

differences in tax policy

differing economic performance in respect of employment and earnings

differences in the taxpayer distribution

changes in the balance between taxpayers and non-taxpayers.

The net result is that some of the additional spending power that would be implied by the Scottish Government's income tax policy choices has been offset by differential economic performance.

Take, for example, 2019-20 (the most recent year for which actual income tax receipts are now known). As shown in Table 7 above, SPICe modelling suggests that the Scottish Government's income tax policy for that year would generate £620 million more NSND income tax revenue than would have been generated if the Scottish Government had followed the same income tax policy as the UK government. The Scottish Government estimated that - after taking behavioural responses into account - the Scottish Government policy would generate £500 million more than the rUK policy. However, as illustrated in Figure 8, the net effect on the Scottish budget is determined by the gap between the block grant adjustment for income tax and the revenues generated. For 2019-20, this difference was £148 million.3

Over the period for which outturn data are available (2017-18 to 2019-20), the gaps between the block grant adjustments and revenues for NSND income tax total £170 million (see Table 8 below). This would indicate that, the decision to adopt a different income tax policy over this period has generated an additional £170 million for the Scottish budget than would have been available if income tax had not been devolved.

| Year | NSND income tax revenues (£m) | Block grant adjustment for NSND income tax (£m) | Difference (£m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017-18 | 10,916 | 11,013 | -97 |

| 2018-19 | 11,556 | 11,437 | 119 |

| 2019-20 | 11,833 | 11,685 | 148 |

| Total | 170 |

Although a reasonably large sum of money, this is considerably smaller than the estimate of the revenues generated by Scotland adopting a different income tax policy from rUK over the same period. These total an estimated £900 million (after behavioural responses) for the same period (see figures for 2017-18 to 2019-20 in earlier Table 7).

The gap between the £170 million available to the Scottish budget and the estimated £900 million extra that Scottish taxpayers have paid over the period reflects the risks inherent in tax devolution. The Scottish Government budget has not seen the full impact of the differential tax policies due to differences in economic factors affecting the amount of tax that Scottish taxpayers have generated, such as differential wage growth, differences in the composition of the tax base and differences in the balance between taxpayers and non-taxpayers across the population.

These issues are also explored in a blog by the Fraser of Allander Institute on the 2019-20 outturn data.

Impact of the Scottish Government's income tax decisions on individuals and households

The changes introduced by the Scottish Government over the last three years mean that Scottish income tax policy now looks quite different from rUK income tax policy. This means that individuals and households are paying different amounts of income tax than they would be if they were living elsewhere in the UK. This section looks at how individuals and households have been affected by these decisions by comparing what they would be paying under the rUK system with what they are paying under the Scottish system. The analysis that follows compares Scotland and rUK on the basis of 2021-22 income tax policies.

Impact on individuals

The policy changes introduced by the Scottish Government in relation to income tax mean that taxpayers in Scotland will now pay different amounts of income tax then they would pay if they were paying income tax elsewhere in the UK. For some individuals, the changes mean that they will be paying less income tax than they would pay elsewhere in the UK, while others will be paying more.

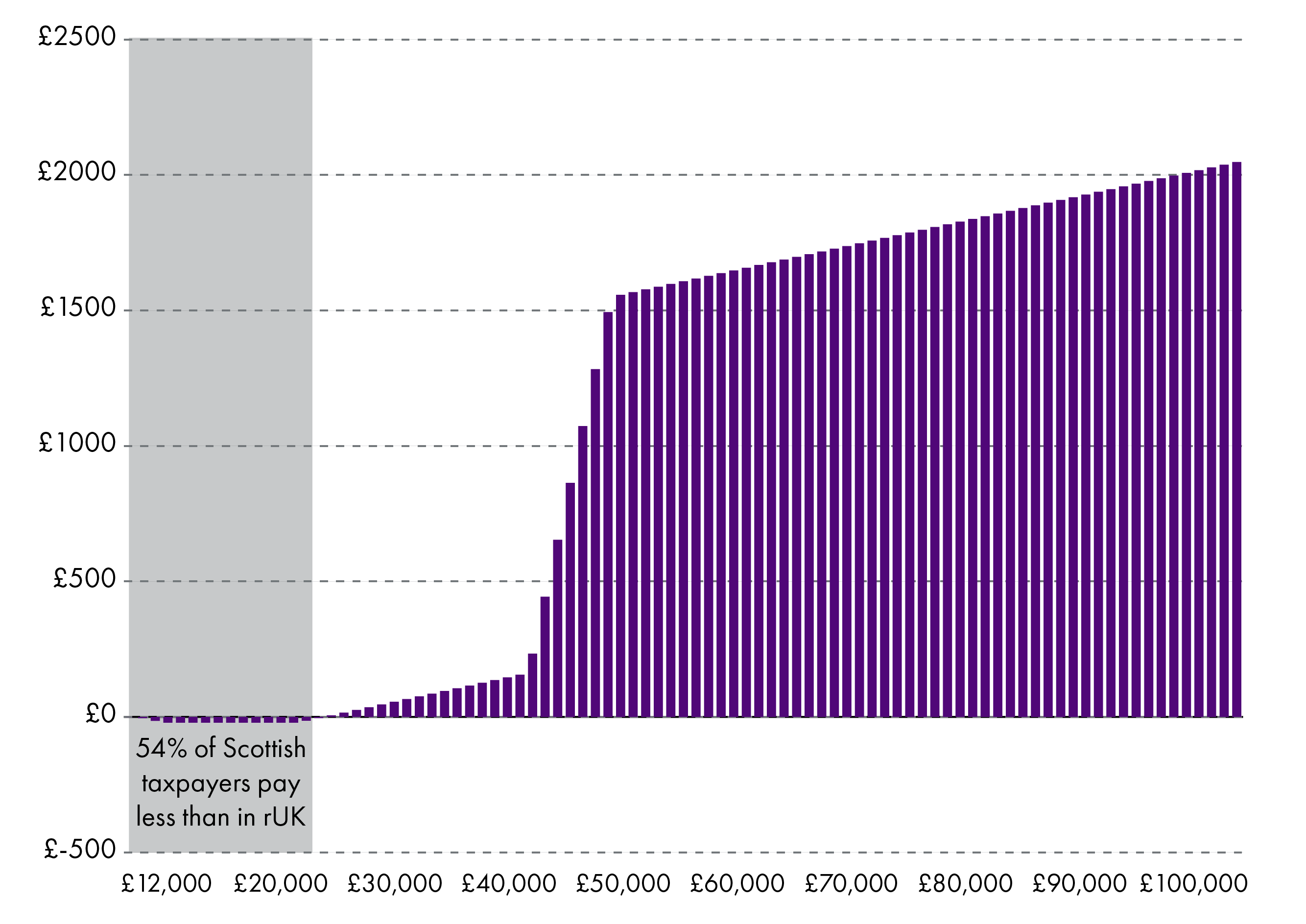

Taxpayers in Scotland earning less than £27,393 are paying less in income tax than they would be if they were rUK taxpayers (based on 2021-22 policies). However, those earning more than this are paying more income tax in Scotland than they would as a rUK taxpayer. According to the Scottish Government, around 54% of Scottish taxpayers (1.4 million individuals) pay less income tax in Scotland than they would in rUK.1

For those earning less than £27,393, the difference in income tax paid in Scotland compared with rUK is modest - around £21 per year less in Scotland for most of these taxpayers. However, for those earning more than £27,393, the difference between what they pay in Scotland and what they would pay in rUK increases rapidly with earnings. Someone earning £50,000 will pay £1,494 per year more in income tax in Scotland than they would in rUK. For someone earning £100,000, the difference is more than £2,000 per year. This is illustrated in Figure 9.

Impact on households

The impact of the different policy choices made by the Scottish Government for particular households will differ from the impact on individuals as the impact on households is determined by the composition of those households. For example, the impact on a household with an annual income of £50,000 will be different if that amount is split between two earners, rather than a single earner. Household income will also include any benefits that the household is entitled to. Entitlement to means-tested benefits will depend on household income so, if income tax policy changes and household income increases as a result, this could be offset (partially or fully) by a reduction in benefits income.

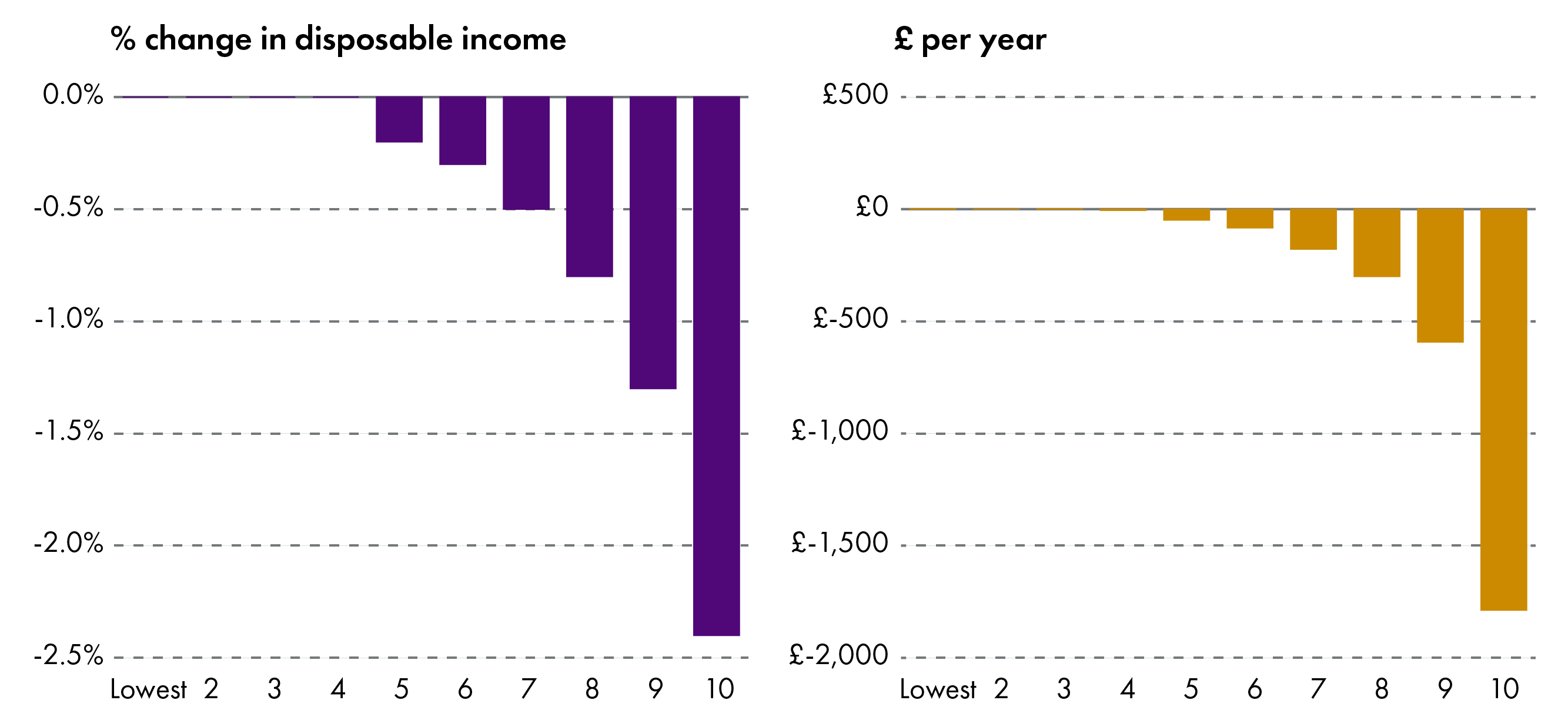

Figure 10 shows how households at different income levels are affected by the Scottish income tax policy, as compared with the rUK income tax policy in 2021-22. Households are ranked by income level. The first decile represents the 10% of households with the lowest incomes, the second decile represents the next 10% according to household income, and so on, through to the tenth decile, which represents the top 10% of households in terms of household income. Incomes are measured by "equivalised disposable income". Equivalised means that incomes are adjusted to reflect household composition (reflecting the fact that a larger family will require a higher income in order to achieve the same standard of living as a smaller family, or single person household). Disposable income means that income is measured after tax.

The figures show that the Scottish income tax system results in a negligible impact on the incomes of the lowest four deciles, when compared with the rUK income tax system. In part, this will be because some households at the lower end of the income distribution will not include people in employment, so will not be affected by any changes to the income tax system. Even where there are individuals in work, they may be on earnings that do not take them above the personal allowance and so, again, are not affected by changes to the income tax system above the personal allowance threshold. Also, as noted in the section 'Impact on individuals', those individuals who are paying less income tax in Scotland are only benefiting by around £20 per year.

Households at the higher end of the income distribution see the most impact from the Scottish income tax system (when compared with the rUK). The top 10% of households in income terms see an average reduction of around £1,800 per year in household income (equivalent to 2.4% of household income).

Interaction with tax policy in the rest of the UK

Scottish income tax cannot be considered in isolation because the powers are only partly devolved. The tax is intricately interwoven with UK taxes, and the Scottish Parliament has only a limited number of pieces of the jigsaw. (Institute of Chartered Accountants)

Fraser of Allander Institute. (2017, September). Scotland’s Budget Report 2017. Retrieved from https://www.sbs.strath.ac.uk/economics/fraser/20170926/Scotlands-Budget-2017.pdf [accessed 27 November 2019]

There are a number of ways in which decisions on taxation in the rest of the UK (rUK) will interact with the Scottish Government's decisions on income tax policy, meaning that these decisions can't be seen in isolation from the wider UK tax policy framework. A number of these interactions are considered below. These interactions could influence taxpayer behaviour, which is discussed in the section on Behavioural Responses to income tax policy.

National Insurance Contributions

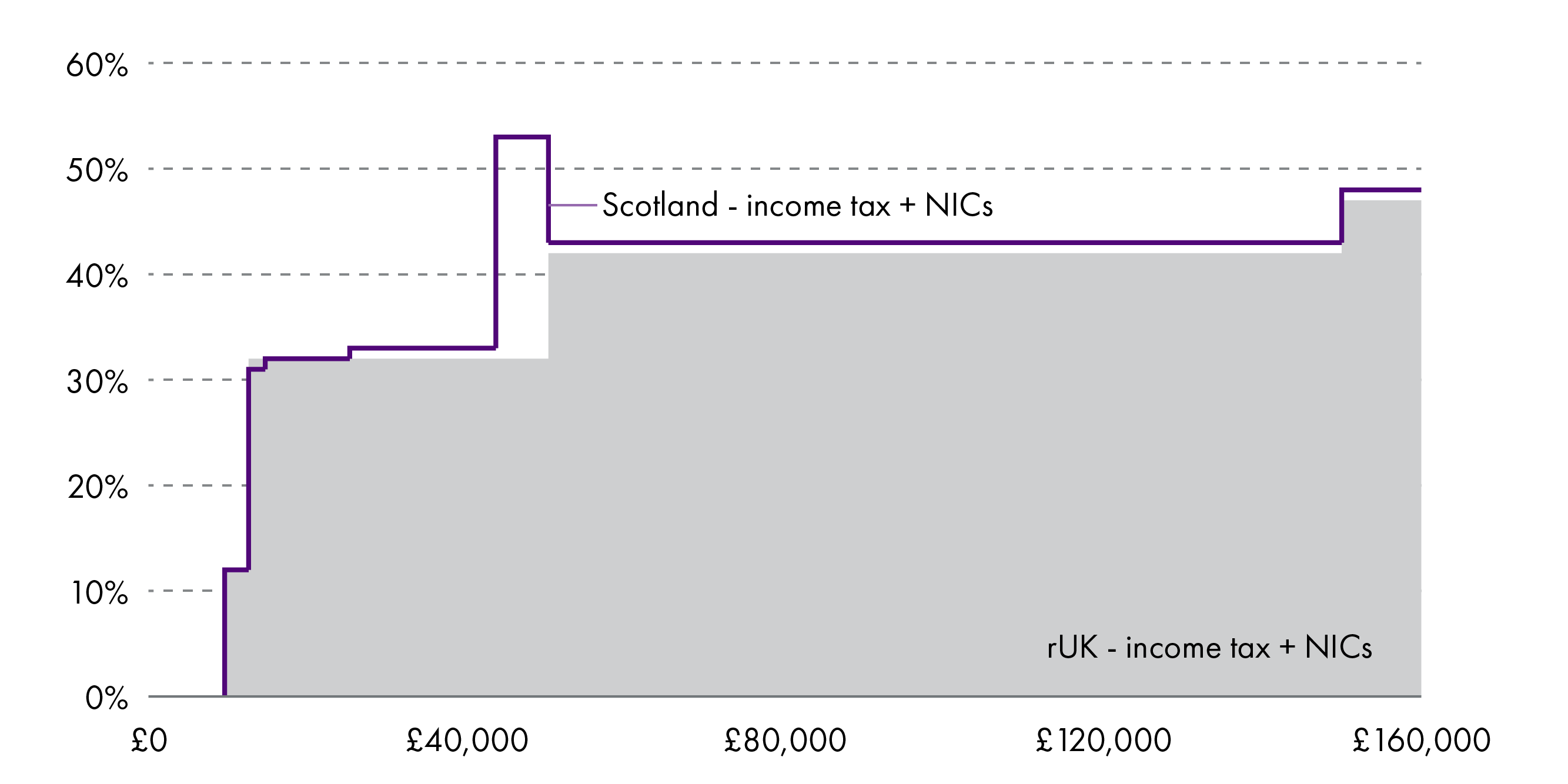

Decisions on national insurance contributions (NICs) are made by the UK Government, but will interact with the Scottish Government's decisions on NSND income tax to determine overall tax rates for Scottish taxpayers.

NICs are linked to UK tax thresholds and the NIC rate drops from 12% to 2% at the UK higher rate threshold, which is £50,270 for the tax year 2021-22. However, because the Scottish higher rate threshold is lower (at £43,662), this means that there is a range of earnings where Scottish taxpayers pay both the standard rate of NICs and the higher rate of income tax.

Scottish taxpayers who earn between the Scottish higher rate threshold (£43,662) and the rUK higher rate threshold (£50,270) will pay 41% income tax and 12% NICs on their earnings between these two amounts – a combined tax rate of 53%.

Taxation of savings, dividends and capital gains

Scottish income tax rates and thresholds do not apply to income from savings and dividends. Scottish taxpayers' income from savings and dividends is taxed according to UK tax policy. Since the tax thresholds in Scotland differ from those in rUK, this means that Scottish taxpayers earning between £43,662 (the Scottish higher tax threshold) and £50,270 (the rUK higher tax threshold) will pay 41% on employment income, but lower rates on any savings and dividends income in this range, because savings and dividends are taxed according to rUK rates and thresholds. Capital gains are also taxed according to rates and thresholds determined by the UK government.

The different taxation of different types of income might influence the decisions of any UK taxpayer on how to manage their income sources (if they are able to do so). For taxpayers in Scotland, there are additional considerations that might influence behaviour due to the differentials between rUK tax policy and Scottish tax policy. This is discussed further below in the section on behavioural responses to income tax policy.

Corporation tax

Corporation tax is reserved to the UK government and is currently lower than income tax. At present, corporation tax is 19% of profits after applying relevant reliefs, but this is set to increase to 25% from April 2023.1 All UK taxpayers will face choices over how they manage their tax payments and - especially those at the higher end of the income scale - may decide to plan their income so as to reduce their tax bills. For example, a sole trader might decide to set themselves up as a company ("incorporate"), so that they pay corporation tax on any profits and the lower rate of income tax that applies to dividends. These decisions might further be influenced by the widening gap between Scottish income tax and rUK income tax policy, but will also be influenced by the proposed change in corporation tax rates.

Behavioural responses to income tax policy

Any changes to tax policies can result in individuals changing their behaviour so as to manage either levels of net earnings or the amount of tax that they pay. In response to a given tax change, taxpayers might (if they are able):

change the number of hours they work or seek alternative employment (or even stop working altogether).

seek to change how they receive their income (for example, by taking it in the form of dividends or setting themselves up as a company).

move to a different location where tax rates are lower (again, if this is a realistic possibility).

These responses might reflect both a change in Scottish tax policy, and/or a change in the differential between Scottish and rUK income tax policy. The earlier section on 'Impact on individuals', noted that Scottish taxpayers who are earning more than £27,393 will pay more tax in Scotland than they would in rUK. For those able to do so, this could influence decisions around where to reside for tax purposes. The section looking at the 'Interaction with tax policy in the rest of the UK' also highlighted some further factors that might influence taxpayer decisions around how to manage income.

As noted in the section on the 2020-21 budget, the Scottish Government opted to freeze the higher rate threshold for income tax for the 2020-21 tax year. This represented a change to the "default" position of increasing thresholds in line with inflation. In their accompanying February 2020 Economic and Fiscal Forecasts, the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) judged that the Scottish Government’s proposed income tax policy of freezing the higher rate threshold would generate £59 million (when compared with a policy which included uprating of the higher rate threshold). However, they also estimated that changes in taxpayer behaviour would reduce the actual amount generated to £51 million.

This was a relatively minor change; bigger policy decisions would be expected to have more significant consequences in terms of behavioural change. For example, the SFC estimated that the more significant changes to income tax policy introduced in the 2018-19 budget would result in behavioural effects of £56 million (in the context of a pre-behavioural revenue estimate of £276 million).1

Behavioural responses need to be assessed in relation to each specific policy decision - there are no general rules to the scale of any behavioural response as it will depend on the extent to which different groups of taxpayers are affected (with higher income taxpayers typically showing a larger behavioural response) and also on the interaction with other tax policies both within Scotland and across the UK.

The SFC have published details on their methodological approach to estimating behavioural responses. This paper notes that:

"Taxpayer behavioural change is uncertain and challenging to quantify, even when good historic data are available. However, there is strong international evidence that taxpayers do respond to changes in tax policy and that this impacts on tax revenues."1

The Scottish Government has also published research on behavioural impacts, which similarly highlights the uncertainties involved in estimating such responses:

"There is considerable uncertainty when it comes to measuring behavioural responses to changes in tax policy. The empirical literature agrees, however, that responsiveness increases with income because top earners have greater means and incentives to limit their tax liabilities."3

The SFC keeps their methodological approach to measuring behavioural impacts under regular review.

Ready reckoners for income tax

The Scottish Government has published some 'ready reckoners' showing the estimated effect of a range of hypothetical changes to income tax policy. 1This helps to provide an indication of the potential revenue effects of income tax policy decisions. All the estimates take account of potential behavioural effects, although the note states that:

"The scale of taxpayers’ behavioural responses to policy changes remains a highly debated and uncertain issue."

| Policy change | Estimated change in revenue including behavioural effects (£m) |

|---|---|

| Change Starter Rate by 1p | 48 |

| Change Basic Rate by 1p | 170 |

| Change Intermediate Rate by 1p | 126 |

| Change Higher Rate by 1p | 64 |

| Change Top Rate by 1p** | Negligible* |

* The policy raises/costs less than +/-£2 million.

** The estimates for changes to the top rate of tax are particularly uncertain. These revenue numbers do not account for any forestalling effects (bringing forward or delaying the timing of income), which could significantly change the profile of revenue in the short term.

The estimated impacts are broadly symmetric - for example, a 1p increase in the starter rate will generate an estimated £48 million, while a 1p cut in the starter rate will result in an estimated £48 million reduction in revenue.

As the note highlights, small changes to the top rate of income tax (which is currently 46p) are not expected to have a significant impact on revenue, after taking account of behavioural changes. This is a reflection of both the fact that there is only a small number of taxpayers paying tax at this rate in Scotland (an estimated 18,000 individuals in 2021-22). It also reflects the fact that taxpayers at this end of the income distribution are known to show the greatest behavioural response to changes in income tax policy and are more likely to seek to change the way they receive income, or even to relocate in response to tax changes.

The Scottish Government note also provides detail on the estimated effects of changes to the rate thresholds.

Scottish Parliament procedure in relation to income tax

The Scottish Government sets out its proposals for income tax for the forthcoming tax year alongside its annual budget. This would normally be in December, although the timing of the Scottish budget has varied in recent years due to delayed UK budgets. The Scottish budget normally follows the UK budget, but the past two UK budgets have been delayed as a result of both UK elections and the COVID-19 pandemic.

When it is first published alongside the Scottish budget, the income tax policy is a proposal for Parliamentary consideration. Following scrutiny of the budget and the accompanying income tax policy, the policy (potentially with amendments) is then presented by way of a Scottish Rate Resolution. This Rate Resolution is considered by the Scottish Parliament in a plenary session. Scottish Parliament Standing Orders state that the Parliament must pass a Scottish Rate Resolution before the start of the tax year to which it relates. The Rate Resolution must also be passed before the Budget Bill for the same year can move to Stage 3, as it determines a significant proportion of the resources available to the Scottish Government in setting its budget.1