Fair Rents (Scotland) Bill

The Fair (Rents) (Scotland) Bill is a Member's Bill aimed at protecting tenants living in private rented housing. It would introduce measures to limit rent increases for existing tenants. It would also allow a tenant to apply to a rent officer to have a ‘fair open market rent’ set for the property. It also seeks to improve the availability of data on private rents. This briefing provides background information on the proposals, details of the Bill and information on the views of respondents to the Local Government and Communities Committee's call for evidence on the Bill.

Summary of the Bill

The Fair Rents (Scotland) Bill is a Member's bill introduced in the Parliament by Pauline McNeill MSP on 1 June 2020.

The aim of the Bill is to improve the way rents are set in private rented housing. This is intended to reduce poverty and support low income tenants and their families. The Bill also aims to the improve the availability of data on private rent levels.

The Bill would:

prevent a landlord from increasing rent for a tenant with a private residential tenancy by more than a set level (related to inflation)

allow a tenant to apply to the rent officer to have a ‘fair open market rent’ set for the property (a tenant can do this only once in any 12-month period)

require private landlords to include details of the rent they charge in the public register known as the Scottish Landlord Register.

The Local Government and Communities Committee is the lead committee scrutinising the Bill at Stage 1 (scrutiny of the general principles of the Bill). The Committee asked for views on the Bill to help inform its scrutiny. Over 200 responses were received to its call for evidence.

The key theme from respondents supporting the Bill was that it would result in a positive outcome for tenants, rebalancing the power in their favour. Some respondents pointed to affordability problems for tenants living in private rented housing.

The key theme for those not supporting the Bill, or expressing some caveats to their support, was the potentially negative impact on the supply of private rented accommodation. Respondents anticipated that increased regulation and the restriction on rent increases would make being a private landlord less attractive and might result in landlords leaving the market. Some respondents also argued that landlords would have less incentive to improve their properties and it could result in landlords increasing their rent more often than they otherwise would have done.

Many respondents generally supported the aim of improving the availability of data on rents. Some suggested that this would improve transparency and facilitate better strategic planning, particularly by councils. On the other hand, those opposing the proposals were concerned about a potential invasion of privacy and questioned the need for additional information to be collected.

The remainder of this briefing provides some contextual information on private rented housing in Scotland and the debate about rent control, followed by a more detailed look at the Bill's proposals.

Private rented housing: context

The number of households living in private rented housing has increased over the last 20 years. Between 1999-2016, the proportion of households in Scotland living in private rented housing increased from 5% to 15%. It has stabilised since then with around 14% of all Scottish households (340,000) living in private rented homes.1

In recognition of the growing importance of the private rented sector (PRS) in Scotland, the Scottish Government has instigated legislative reforms to tighten regulation over the past 15 years or so. For example, private landlords must be registered with their local council and will be excluded if they are not considered a “fit and proper person.” All tenancy deposits must now be placed in a government-backed tenancy deposit scheme.

Major reform to the private tenancy regime was introduced by the Private Housing (Tenancies) (Scotland) Act 2016 ('the 2016 Act'). The 2016 Act introduced a new type of tenancy, the “private residential tenancy” (PRT), to supersede existing tenancy arrangements (most commonly a short assured tenancy). From 1 December 2017, most new tenancies in the PRS are PRTs. The Bill proposes amendments to the 2016 Act.

The following sections provide more information on:

Private residential tenancy: rent provisions

The 2016 Act introduced new rules on rent with the aim of providing tenants with protection against excessive rent increases and providing rent predictability.1 As before, rents are agreed between the landlord and the tenant at the outset of the tenancy but the 2016 Act also provides that:

The landlord can only increase rent once a year and must give tenants three months’ notice.

If the tenant does not agree, they can refer the case to a rent officer (a public employee working for Rent Services Scotland) for adjudication.

If a tenant or landlord is not happy with the rent officer's decision, they can appeal to the First-tier Tribunal for Scotland (Housing and Property Chamber) ('The Tribunal'). The Tribunal is a judicial body set up to decide on private landlord-tenant disputes.

The case will be decided by reference to what the rent officer or Tribunal determines is the “open market rent” for the property. Rent officers and the Tribunal have the power to maintain, increase or decrease the proposed rent.

The 2016 Act also gives councils the power to apply to the Scottish Government to have all or part of its area designated as a rent pressure zone (RPZ). Within an RPZ, annual rent increases for existing tenants with a PRT would be capped at no more than Consumer Price Inflation (CPI) plus 1%, for a duration of 5 years.

When councils apply to the Scottish Government to have an RPZ declared, they must submit evidence to the Scottish Government to demonstrate that:2

rents payable within the proposed RPZ are rising by too much

the rent rises within the proposed zone are causing undue hardship to tenants

the local authority is coming under increasing pressure to provide housing or subsidise the cost of housing as a consequence of the rent rises within the proposed zone.

Impact of new tenancy rent provisions

Given the new PRT has only been available since December 2017, it is still relatively early to assess the impact of the new tenancy. However, some evidence is available.

Rent increase adjudications

Table 1 shows the results of rent officer adjudications on PRT cases at 17 November 2020. There have been 40 adjudications. In 65% of these cases, the rent officer has set a rent lower than that proposed in the rent increase notice, while in 35% of cases the rent officer has maintained the proposed rent. In no cases has the rent officer set a higher rent than the landlord had proposed in the rent increase notice.

| Rent officer decision | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Same as proposed rent increase | 14 | 35 |

| Higher than the proposed increase | 0 | 0 |

| Lower than the proposed increase | 26 | 65 |

| Total | 40 | 100 |

The Tribunal publishes the results of all its decisions on its website. From an examination of the published decisions to the start of November 2020, it appears that the Tribunal has only ruled on one appeal against a rent officer adjudication on a rent increase notice. That application was rejected.

Rent pressure zones

No council has yet made an application to the Scottish Government for a rent pressure zone. The rent pressure zone provisions in the 2016 Act have been criticised for several reasons. A particular criticism is that the application process is onerous and there is a lack of existing data that could support an application.2345

Nationwide Foundation study

The Nationwide Foundation has commissioned a three-year study of the private rented sector in Scotland, part of which will examine the operation of the new PRT. In the baseline report published in late 2020, it identified limited impact of rent adjudication provisions, although it also noted that it was difficult to isolate policy impact from other factors. The failure of rent pressure zones and some evidence that the PRT may be encouraging landlords to increase their rents more often was also identified:

So far, the legislative mechanisms for adjudicating rent increases appear to have had little impact, although it is difficult to isolate policy impact from varying market factors, and broader fiscal reforms. In particular, the Rent Pressure Zones mechanism appears to have failed in the policy objective of limiting excessive rent increases, which is likely due to its evidential data requirements. In addition, there is some evidence to suggest that the PRT may be encouraging landlords to raise rents more frequently than they would have done under the assured and short assured tenancy regime, due to the annual rent review process now built into the PRT.

Despite the limitations on published rent data, the evidence from tenants shows that rent affordability is a key factor limiting access to private renting for low income households, tenants from ethnic minorities and single parents in particular. Many tenants say they pay a significant proportion of their income in rent, and just over one in ten tenants described their rent as difficult to afford. Although this may indicate a general acceptance of high rents relative to income, single people and single parents in particular spoke of experiencing significant financial difficulties. Disabled tenants also had difficulties accessing renting, often citing being on benefits as a barrier.

Indigo House in association with IBP Strategy and Research. (2020). Research on the impact of changes to the private rented sector tenancy regime in Scotland. Retrieved from http://www.nationwidefoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Rent-Better-Wave-1-Summary_print.pdf [accessed 6 January 2021]

Another point made by the study concerned tenants' low awareness of their rights and the First-tier Tribunal. The authors recommended that more work is needed to raise awareness of tenancy rights and the role of the Tribunal system as a formal route to justice.

The Scottish Government is working with Nationwide Foundation on this study. It is also taking forward a wider monitoring and evaluation framework for the new tenancy7 and considering what changes need to be made to better support local authorities to make an RPZ application.8

Private rents

There are different sources of rent statistics available, including statistics from letting agents. The existing data on private rents have some limitations. In particular, there is a lack of statistics on rent levels for existing tenancies and a lack of comprehensive statistics on private rent levels at council area level and below.1 Some academics have argued that the private landlord registration database (which contains details of all private landlords and properties that are registered) could be better utilised to provide data to allow a better understanding of the PRS.2

The Scottish Government publishes annual data on private rents in Scotland. This data is sourced from the Rent Service Scotland market evidence database, which is collected for the purposes of determining Local Housing Allowance (LHA) levels (this is the maximum level of benefit support for housing costs private tenants can receive). The rental information contained in the market evidence database is largely based on advertised rents, so it does not represent rent increases for existing tenants.

The latest Scottish Government publication covers the period from 1 October 2019 to 30 September 2020. 3Key points include:

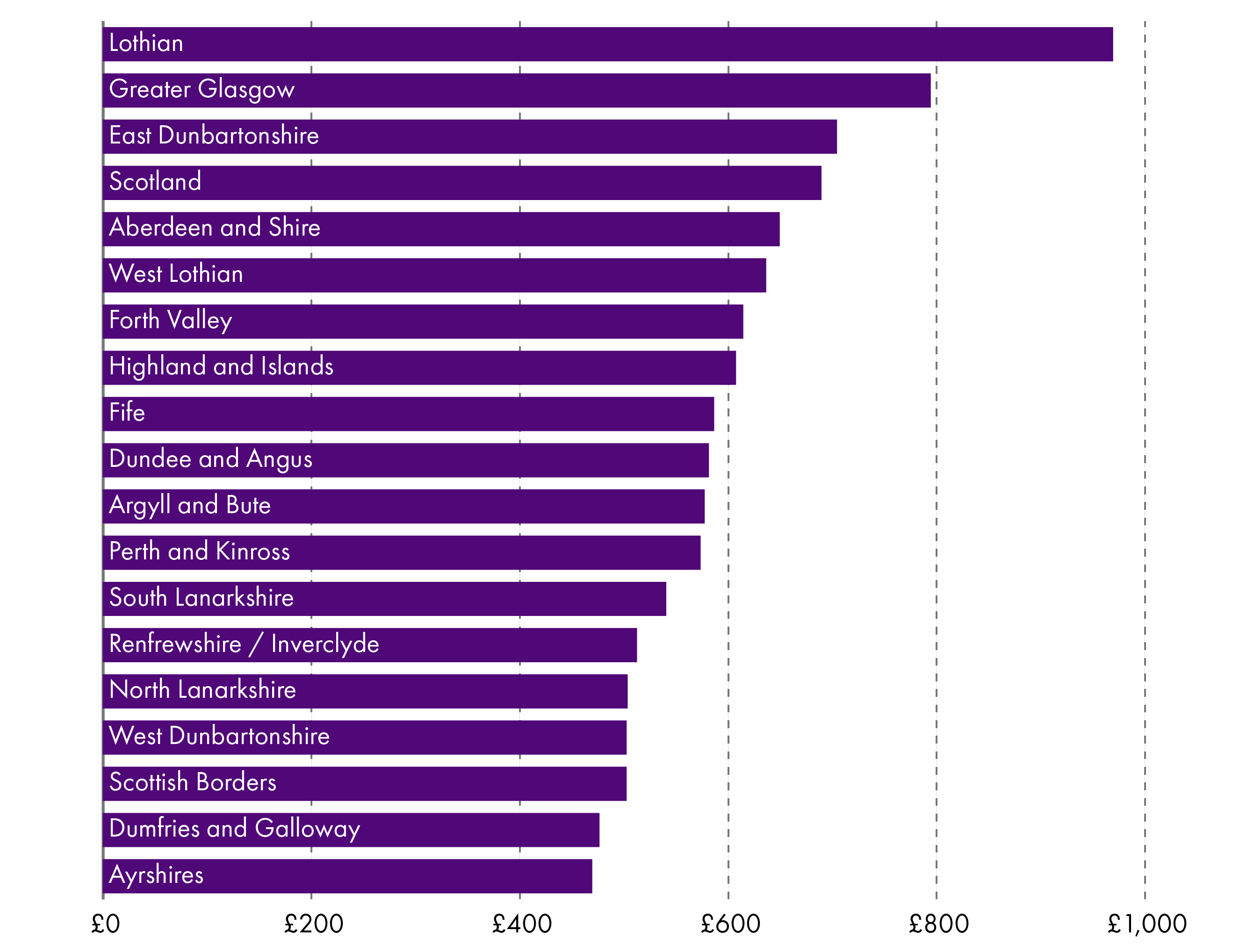

In September 2020, the average rent for a two bedroom property (the most common size of private rented home) across Scotland was £689 a month (see Figure 1). This represents an annual increase of 1.1%, above CPI of 0.5%.

Average two bedroom rents increased above CPI inflation in 11 out of 18 areas, with the largest increase being 4.0% in East Dunbartonshire.

Five areas saw little change in average rents for two bedroom properties compared with the previous year, with annual changes within +/-0.5%. Average rents decreased by more than 0.5% in the Ayrshires (-0.6%) and West Dunbartonshire (-1.3%).

At a Scotland level there were also estimated above inflation increases in average rents for all property sizes: one bedroom shared properties (2.5%), one bedroom (1.8%), three bedroom (2.2%) and four bedroom (2%). Again, there are geographical variations.

Private rents: longer term trends

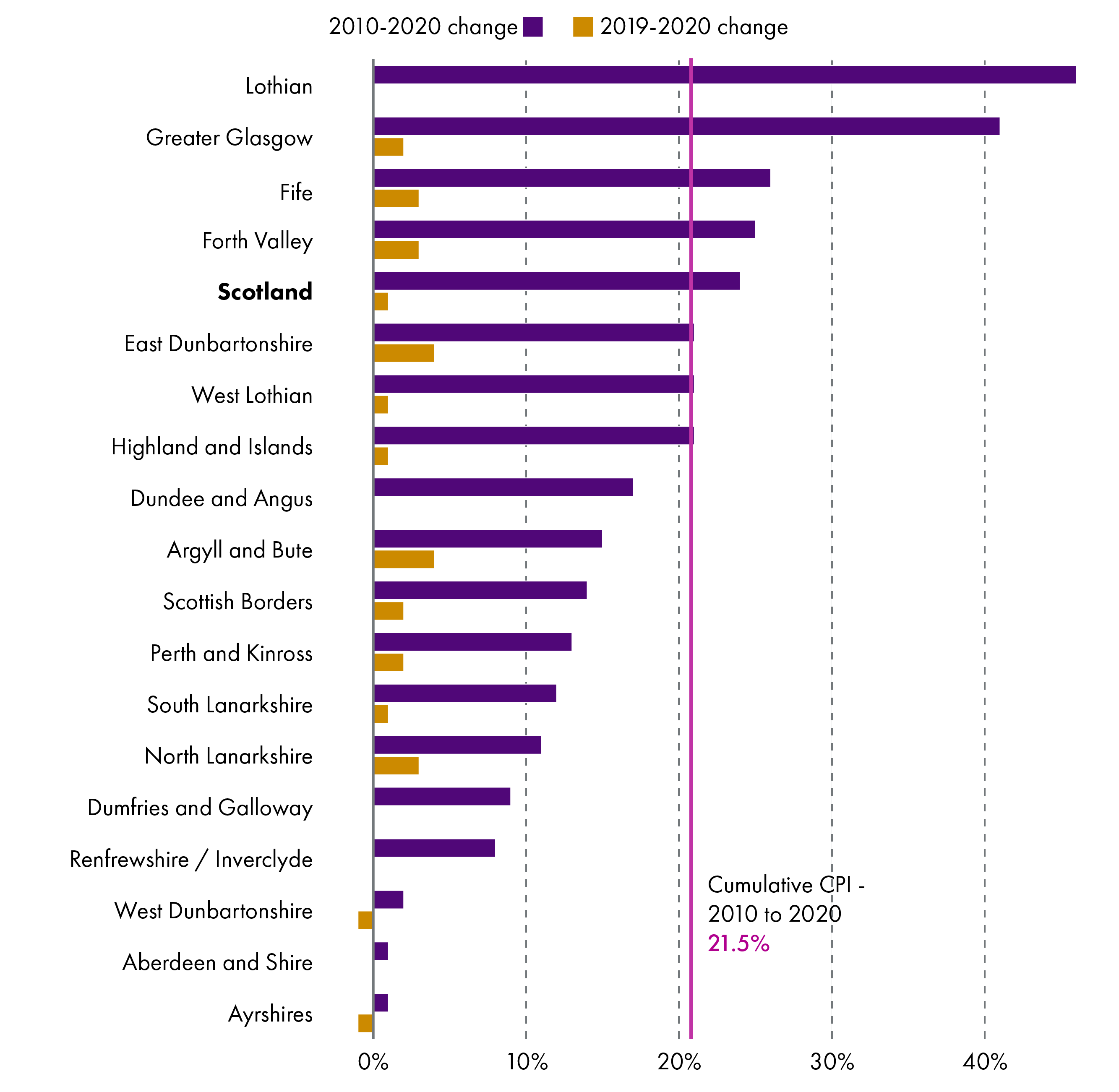

The Scottish Government annual publication also provides longer term trends back to 2010. Across Scotland, between September 2010 to September 2020, average rents for two bedroom properties cumulatively increased by 24.4%, slightly above the cumulative increase in the CPI of 21.5% (see Figure 2 below).

Again, there are geographical variations. In four areas (Lothian, Greater Glasgow, Fife and Forth Valley) rent increases have been above the level of CPI inflation. Lothian has seen the highest increase in private rents for two bedroom properties, with average rents rising by 45.9% over this period.

For the remaining areas of Scotland, cumulative increases have been below CPI inflation and have ranged from 0.9% in Ayrshires to 21.2% in East Dunbartonshire.

Private rent affordability

There is no universal definition of housing affordability. However, the general consensus is that affordability plays a key role in the current housing problems faced within the UK.

A research paper by the Scottish Government analysing the concept of affordability provides a broad but useful definition of rental affordability. The definition is one which is common throughout the literature:

... that affordable rent should be an amount that people can afford to pay for accommodation without sacrificing on other essential needs.

Mean, G. (2018, September 3). How to measure affordability. Retrieved from http://housingevidence.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/R2018_02_01_How_to_measure_affordability.pdf [accessed 5 January 2021]

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation's (JRF) reports on poverty in 2018 and in 2019, suggest that not everyone using the PRS finds rent levels a problem in terms of affordability; however, it is clear that some do. Generally, the poverty rate within the PRS over the period 2016-19 was 33%. This is a slight decrease from the previous five years. However, an increasing proportion of income is being spent on rent, nearing around 30%.2 It is argued that this is a level which is putting households in the position of cutting back on essentials.34 The research recommends that, in order to combat poverty, one action that has to be undertaken is to increase the amount of affordable housing that is available. Similarly, a recent study on housing need in Scotland has identified that the proportion of new households requiring ‘below market rent’ housing has significantly increased to 62%, up from 46% in 2015.5

The JRF’s most recent report on poverty found that that unaffordable housing has been exacerbated by the Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) and challenges are likely to continue. 6Further, it found that there is still huge variability between areas around the country. The median cost of a two bedroom property in Lothian costs almost double to rent at £800 per month than the cheapest in Ayrshire, which is £450 per month. This means that some areas of the country face greater affordability pressures than others. Additionally, households who could previously afford their accommodation, but have been pushed into financial hardship due to COVID-19 and now rely on Universal Credit, will face a shortfall between LHA and the median cost of a two bedroom property of £18 per week. This increases to £47 for a three bedroom property. This is money these households must find from somewhere or risk falling into arrears.

The report concludes that:

'… Lack of affordability severely impacts the ability of renters to cope with income shocks, particularly where rents are beginning to outstrip earnings.' Furthermore, where lower-income households are spending in excess of 30% of their incomes on rent, they are in danger of having to cut back on essentials. It follows that they recommend that the Scottish Government need to work towards establishing a new agreed definition of housing affordability, set at no more than 30% of income.

McCormick, J., & Hay, D. (2020). Poverty in Scotland 2020. Retrieved from https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/poverty-scotland-2020

Rent control debate

The purpose of rent controls within the PRS is to ensure that rents remain affordable for households faced with using the sector as a means of housing. The issue of rent controls is multi-faceted and often politically divisive due to the fact that intervening in markets can have a variety of unintentional consequences.12

An important point to note is that most of the research on rent controls is modelled on areas outwith the UK. This makes it difficult to generalise how rent controls might work in Scotland as the context of the housing system and other housing and economic policies is different.3

It is important to distinguish between the different types of rent control. Rent controls are commonly broken down into two categories: first generation and second generation. First generation rent controls, which are sometimes referred to as ‘hard rent controls’ or ‘rent freezes’, normally involve imposing a limit to the rent that is chargeable for a property to below market levels. Subsequent rent increases during the duration of the tenancy are also controlled or prohibited. These can either apply to the whole of the PRS or defined segments of it. There is a general consensus amongst economists that these types of rigid rent control measures do not work.4

Second generation rent controls are typically more nuanced. Rather than limit the amount of rent to be charged for a property, they consist of rules that restrict rent increases. This is normally done either at the beginning of a tenancy, or within a tenancy. The limit is normally linked to the rate of inflation or the average increase in market rents. These then allow a landlord to impose increases that reflect cost or allow them to invest in the condition of the property through increasing the rent.5

Another form of second generation rent controls are rent stabilisation measures. These are less restrictive and limit the amount of rent increases that can be charged within a tenancy. The idea is that these measures will protect tenants against unexpected large increases in rent, whilst still allowing predictability for the landlord. Additionally, landlords can use this as a method of investment and, alongside security of tenure, would provide them a competitive long-term rate of return in line with other types of investments.4 However, this could potentially encourage landlords to set the initial rent payable to a higher level which might then restrict some groups of tenants from accessing the properties in the first place.

One major area of opposition to rent controls is that they have the potential to de-incentivise landlords from investing in the sector due to the narrowing of profit margins. This would be counterproductive and cause the market to deteriorate by way of hampering investment and reducing supply. Additionally, imposing artificial price ceilings are thought to inhibit the effective allocation of resources. Tenants who have the benefit of living in a property subject to rent controls are less likely to move and lose that benefit. This in turn is thought to cause individuals to remain in properties that are unsuitable for their needs or situation. Moreover, this can have a direct knock-on effect on labour mobility.74

Another argument is that imposing rent controls has the potential to have a negative impact on housing quality and lead to the dilapidation of existing housing stock. This is based on the premise that rent levels will not be sufficient to enable landlords to maintain the standard of their properties. As a result, tenants will be forced to live in substandard accommodation.7

A review conducted on behalf of the Residential Landlords Association set out an evidence-based assessment of the benefits and associated detriments in adopting rent controls. They conclude that the focus for reform should be on putting in place a system which allows indefinite tenancies (which was aimed at England since changes have been made in Scotland in this area), and which imposes a degree of rent stabilisation alongside a much better enforcement system which tackles both poor landlords and tenants.4

In other research, the assertion that the failure of the UK Government to ‘engage seriously and holistically’ with discussions in relation to rental affordability and regulation has meant limitations on LHA are ironically having the same effect as rigid rent control mechanisms. 11 This is because tenants who rely on LHA will, on most occasions, be forced to limit their choice of housing within the PRS to accommodation which has rental rates at or below this level. This means that they might be excluded from living in certain areas or might have to live in accommodation that is unsuitable for their needs and circumstances. In addition to this, landlords who rely on LHA tenants will be forced to limit any increases to rent, to correspond with LHA levels or face the prospect of having no tenant in their property.

Another report in 2018 arrived at similar findings stating that:

… [LHA] rates that bear no relation to rents at the bottom end of the market amount to a crude form of rent control which is punishing tenants.

The Evolving Private Rented Sector : Its Contribution and Potential. (2018). Retrieved from http://www.nationwidefoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Private-Rented-Sector-report.pdf [accessed 12 January 2021]

Although the above report does not support nor oppose rent controls, they come to the conclusion that rent stabilisation measures would provide a degree of predictability for both landlord and tenant. The report endorsed an approach provided by earlier research conducted by the Resolution Foundation 13, which would involve only allowing rent increases linked to CPI inflation for a three-year period within a tenancy. Landlords would then have to give six months’ notice if they wanted to make further increases for the following three-year period.

The Bill: an overview

The Policy Memorandum explains the policy objectives of the Bill:

The primary purpose of the Bill is to improve the way rents are set in Scotland in the PRS, to bring fairness into the private rented sector, to reduce poverty and support low income tenants and their families. It will regulate rents to protect tenants in Scotland and help create a better balance of power between the landlord and tenant in Scotland.

The Bill proposes to protect private sector tenants by introducing measures to limit rent increases, to enable tenants to apply for a fair rent to be determined in relation to past rent increases, and to increase the availability of information about rent levels.

Scottish Parliament. (2020, June). Fair Rents (Scotland) Bill Policy Memorandum . Retrieved from https://beta.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/current-bills/fair-rents-scotland-bill/introduced/policy-memorandum-fair-rents-scotland-bill.pdf [accessed 5 January 2021]paras 10 and 11

All the documents relating to the Bill can be found on the Fair Rents (Scotland) Bill webpage. These include:

the Explanatory Notes4

the Financial Memorandum5.

The Bill and accompanying documents have been prepared by Govan Law Centre on behalf of Pauline McNeill MSP.

Ms McNeill MSP undertook a consultation on her proposals as part of the process of developing the Bill. The consultation document was published in May 2019. 6 There were 98 responses to the consultation; 38 from organisations and 60 from individuals.

A summary of the consultation responses was also prepared by the Scottish Parliament's Non-Government Bills Unit with commentary on the results of the consultation by Ms McNeil.7

The Policy Memorandum explains that:

the Bill has taken on board consultation feedback by introducing delegated secondary legislative provisions to ensure flexibility and agility in relation to the primary rent cap control measure and by aligning the collection of additional rent data with the current system of private landlord registration.

Scottish Parliament. (2020, June). Fair Rents (Scotland) Bill Policy Memorandum . Retrieved from https://beta.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/current-bills/fair-rents-scotland-bill/introduced/policy-memorandum-fair-rents-scotland-bill.pdf [accessed 5 January 2021]

Local Government and Communities Committee call for evidence

The Local Government and Communities Committee ('the Committee') is the lead committee on the Bill at Stage 1 (scrutiny of the general principles of the Bill). The Committee launched its call for views on the Bill on 12 October 2020. Over 200 responses were received.

The key theme from respondents supporting the Bill was that it would result in a positive outcome for tenants rebalancing the power in their favour. Some respondents pointed to affordability problems for tenants living in private rented housing.

While some respondents expressed their support for change, some thought that the Bill do not go far enough or that additional changes were required to support private renters and to improve affordability. For example, many suggested increasing the supply of affordable housing.

The key theme for those not supporting the Bill’s proposals, or expressing some caveats to their support, was the potentially negative impact on the supply of private rented accommodation. Respondents anticipated that increased regulation, and the restriction on rent increases, would make being a private landlord a less attractive investment and might result in landlords leaving the market.

The Bill: detail

This section looks at the specific provisions in the Bill and provides detail of the responses to the Committee call for evidence on the bill.

Section 1: fair rent consumer cap

Section 1 of the Bill would amend the 2016 Act to cap annual rent increases to the annual inflation rate as measured by the CPI plus 1%. As an indication of what this might mean in practice, the CPI 12-month rate was 0.6% in December 2020 but was as high as 2.1% in July 2018.1

Section 1 would also give Scottish Ministers powers to vary the cap. Scottish Ministers could:

vary the additional percentage to be applied to CPI either upwards or downwards (with a negative percentage)

modify the application of the cap

make different provision for its application to different circumstances.

The Member’s consultation proposed that Scottish Ministers would have the power to change the inflation index to ensure that if interest rates rises suddenly, and by a substantial amount, landlords will be protected. The Bill’s proposals regarding the powers of Scottish Ministers have been included “to take on board ‘concerns about a blanket or rigid approach’"(Policy Memorandum para 12).2

The Bill does not provide for any control over the initial rent that is charged.

The Policy Memorandum outlines the expected benefits of this proposal for tenants. For example, it argues that the proposal will

... improve the wellbeing of private tenants through a greater sense of security in their living situation. It should allow private tenants' households to be more resilient to other financial shocks or stresses, as they may be able to budget more effectively in the knowledge that the rent could only increase in line with CPI+1%.

Scottish Parliament. (2020, June). Fair Rents (Scotland) Bill Policy Memorandum . Retrieved from https://beta.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/current-bills/fair-rents-scotland-bill/introduced/policy-memorandum-fair-rents-scotland-bill.pdf [accessed 5 January 2021]

In terms of potential impacts on landlords' income and the potential for landlords to sell their properties, the Policy Memorandum (para 55) argues that the cap "would not remove the current financial benefits of renting out a property.”2

Section 1: call for evidence responses

The respondents to the Committee call for evidence on the Bill raised similar points to the Member's consultation on the bill.

Supportive responses agreed that the proposal would benefit tenants in the private rented sector, for whom affordability was a significant issue. It should also introduce a degree of consistency regarding increases in rent levels across Scotland.

There was also a significant degree of opposition to the measure, however, with a range of arguments cited, including that:

The supply of private rented accommodation would be negatively impacted.

Inflation was not an appropriate benchmark. For example, some respondents suggested that the use of the Consumer Price Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH) would be more appropriate.

A national approach was not appropriate, as local areas had different rent pressures.

There was already legislation in place to limit rent increases and introduce rent pressure zones. It would be preferable to make this legislation work more effectively.

It will not adequately address the issue of affordability, for example, because initial rents are not subject to any cap.

Not every landlord increases their rent each year but this proposal may encourage landlords to do so.

It would inhibit flexibility, for example, some private landlords have temporarily reduced their rents in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The proposals would mean that it would be difficult for landlords to get back to the 'normal' rent levels they charge.

Section 2: fair open market rent

Section 2 of the Bill would amend the 2016 Act and give tenants the right to apply to a rent officer to have a fair open market rent set for their property. In determining the fair market rent, the rent officer would have to have regard to:

the general poor condition of the property

any failure to meet the repairing standard

the poor energy efficiency of the property or its appliances for space heating and hot water

the inadequate standard of internal decor and furniture provided

the overall amenity of the property.

The Policy Memorandum (para 22) explains that

These factors seek to encapsulate the objective criteria that would lead a tenant to consider their rent was unfair in relation to the standard and quality of their subjects of let.1

The tenant and landlord could appeal a rent officer’s decision to the Tribunal. When a tenant applies for a fair rent determination, rent officers and the Tribunal would be able to either lower or maintain the rent, but would not be able to raise the rent. Any order made by the rent officer/Tribunal would remain in force for a period of 12 months from its effective date. During this period a rent increase notice by the landlord would have no effect.

The Policy Memorandum states that "this will re-balance the power of the appeals process which currently acts a barrier to a tenant taking a case to appeal."1

This specific proposal did not form part of the original consultation on the Bill's proposals. The Member’s consultation proposed that when an appeal about a rent increase notice is made, the rent officer or Tribunal could only maintain or decrease the rent, not increase it. However, that proposal is not contained in the Bill.

This means that there would two processes that would allow tenants to challenge their rent. A tenant already has the right to refer a rent increase notice to a rent officer. Section 2 of the Bill would provide an additional right for tenants to challenge their rent at any time. The rent officer/ Tribunal could only maintain or lower existing rent.

Section 2: call for evidence responses

Respondents to the Committee call for evidence on the Bill expressed mixed opinions on this proposal.

Respondents provided a variety of reasons for not supporting the proposal including:

The rent has already been agreed by the landlord and the tenant at the outset of the tenancy and tenants can already appeal a rent increase notice.

The definition of a fair rent was subjective and more guidance was needed.

It was not fair to the landlord that a rent officer or Tribunal could not increase the rent.

There is existing legislation that deals with poor property condition in private rented housing.

Reasons for supporting the proposal included:

As the rent officer or Tribunal cannot increase any rent referred to it, this would remove a barrier to tenants accessing this option.

Without this measure, limiting rent increases to 1% may simply encourage landlords to induce a high turnover of tenants, and raise rents between each tenancy.

Appealing to a third party has benefits and would ensure that the tenancy is fair, and not exploitative.

In terms of implementing the proposals, some respondents suggested that the proposal could substantially increase the workload of rent officers or the Tribunal. Some respondents also suggested that advice to tenants on their rights, and support for them to enforce their rights, would be important for the benefits of the proposal to be realised.

Section 3: additional information on the landlord register

The private landlord registration scheme, established under the Antisocial Behaviour etc.(Scotland) Act 2004, requires that private landlords must register themselves and the property they own with the relevant council where the property is situated. Landlords must re-register every three years.

When a landlord applies for registration, they must provide the council with prescribed information. This includes, amongst other things, material which shows whether they have committed specific offences or contravened any provision of housing law or landlord and tenant law. In 2019, the prescribed information was expanded, requiring applicants to confirm their compliance with existing legal responsibilities in relation to property management and condition. The prescribed information helps councils in their assessment of whether the applicant is a ‘fit and proper person’ to let houses.

Some of the information supplied by private landlords is publicly available in the Scottish Landlord Register database which is maintained by the National Records of Scotland.

Section 3 of the Bill would require landlords to enter additional information in the Scottish Landlord Register when they apply to their local council to be registered or re-register. The following additional information would be required:

the monthly rent charged

the number of occupiers

the number of bedrooms and living apartments.

The Bill would also ensure that members of the public could access the additional information required to be disclosed.

The aim of this proposal it to improve the availability of data on private rents at a council area, or below council area, level. The Policy Memorandum states:

Improved data will improve decision making on the fairness of rents by Rent Officers and First-tier Tribunals. A tenant would be better informed as to whether the rent they are being charged is unfair if they were able to compare it to rents charged for similar properties in the area. This would allow them to make a better judgement as to whether they might want to appeal their rent.

Para 17,Scottish Parliament. (2020, June). Fair Rents (Scotland) Bill Policy Memorandum . Retrieved from https://beta.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/current-bills/fair-rents-scotland-bill/introduced/policy-memorandum-fair-rents-scotland-bill.pdf [accessed 5 January 2021]

The Member’s consultation proposed that landlords would have to provide rental information at the point of registration and would also have update the information whenever their rent changes. However, following the consultation, the Policy Memorandum notes that, “Section 3 of the Bill is now less onerous administratively, as additional information is only required to be provided at the point of registration or re-registration.”

Section 3: call for evidence responses

Many of the respondents to the Committee's call for evidence on the Bill broadly supported the aim of increasing the availability of rental data in Scotland.

Arguments made in support of the proposals included that:

It would provide greater transparency on rent levels which would benefit tenants.

Improved private rental data would allow more effective analysis of rent levels and inform policy solutions.

Reasons for opposing the proposal, or partially supporting the proposal, included that:

Privacy and data protection issues might arise.

Market rental data already exists therefore the need for additional data was questioned.

It would be particularly difficult for landlords to provide information on the number of occupiers in the property as they do not always know this.

Without further contextual information, comparisons on rent levels would be meaningless.

As rental data would only be required to be provided by the landlord every 3 years this would not provide useful information on within tenancy rent increases.

Councils are responsible for administering and enforcing the private landlord registration provisions. Some councils responding to the call for evidence suggested that this would lead to an additional workload for councils that would need to be funded. A couple of respondents also questioned the ability of the existing private landlord registration database to hold this information.

Section 4: statement on impact of right to a fair rent

Section 4 of the Bill would place a duty on the Scottish Government to report on the impact of section 1 of the Bill on the affordability of rents for tenants and on the operation of section 2 of the Bill.

There were no substantial comments made about this section of the Bill in response to the Committee call for evidence on the Bill.