Housing conditions and standards (updated)

This briefing provides information on housing conditions in Scotland with a brief overview of results from the Scottish Housing Condition Survey. It also provides information on the different house condition standards that exist across the three main tenures in Scotland: owner-occupied, private rented and social rented; and future Scottish Government plans in this area. This briefing updates SPICe Briefing SB 19-31.

Executive Summary

The Scottish House Condition Survey 2019 shows that the condition, and energy efficiency, of housing in Scotland has improved since 2012. Despite these improvements, the survey reveals that:

just over half of homes in Scotland have some disrepair to critical elements, such as roof coverings

just under a fifth of homes have some kind of urgent disrepair to critical elements

around one fifth of Scotland's homes were built before 1919 and these older homes tend to be in poorer condition.

House condition standards

There are several different house condition standards that apply to homes in different tenures, i.e. owner-occupied, social rented (rented from a council or housing association) and private rented. These different standards may partly influence the condition of homes in different tenures.

The Tolerable Standardis a basic standard set out in legislation that applies to homes in all tenures. Councils have powers to enforce this standard. Only a small proportion of Scotland's homes, around 2%, are estimated to be below the Tolerable Standard.

Private landlords have a duty to make sure the homes they let meet the 'Repairing Standard'(which includes the Tolerable Standard) as set out in legislation.

The social rented sector is the most regulated tenure and currently has the most extensive standards. Social landlords must make sure that the homes they let meet the Tolerable Standard in addition to other aspects of the Scottish Housing Quality Standard and the Energy Efficiency Standard for Social Housing.

Scottish Government plans for a common housing standard

Recent legislative changes sought to bring the standards closer together with the introduction of a common fire and carbon monoxide safety standard and other changes to align the Repairing Standard more closely with social housing standards.

The Scottish Government is proposing further changes and plans to introduce legislation for a common housing standard across all tenures. It expects to consult on proposals in 2021 with legislation being progressed in 2024-25 and implemented on a phased basis in the period up to 2030.

All new buildings, and substantially refurbished ones, must also meet the relevant building standards regulations in force at the time the building warrant was approved. This briefing does not cover these standards.

The climate change agenda

A key priority for the Scottish Government is to meet its climate change target of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045. Improving the energy efficiency of homes is a key strand of this climate change agenda.

There has already been substantial investment in energy efficiency programmes and social landlords are required to ensure their homes meet certain levels of energy efficiency.

The Scottish Government has plans to introduce a regulatory framework that would require all homes to achieve a good level of energy efficiency by 2033 (equivalent to at least Energy Performance Certificate Rating C), where this is feasible and cost-effective.

In the longer term, the Scottish Government also plans to bring forward legislation which, subject to devolved competence, will include regulatory proposals to require the installation of zero or very near zero emissions heating systems in existing buildings.

The condition of flats

Keeping flats, and other important parts of the building, in good condition can be problematic, particularly where the blocks are in mixed tenure ownership (e.g. a mix of rented properties and those which are owner-occupied).

The Parliamentary Working Group on Maintenance of Tenement Scheme Property's report, published in 2019, made recommendations for new legislation to improve the maintenance of tenements.

The Scottish Government has agreed that action is needed and its Housing to 2040 route map set out plans to act on the recommendations of the working group. 1 However, it is not yet clear when legislation might be introduced to implement changes to tenement law.

Council powers to tackle disrepair

The Housing (Scotland) Act 2006 reformed the system of councils' powers to tackle disrepair in private housing.

One of the main policy aims behind the reforms was to inspire a cultural change and encourage owner-occupiers to take greater responsibility for the upkeep of their homes. However, it appears that this cultural change has not taken place to the extent originally envisaged.

Councils have a range of powers to help owners to improve house conditions in their area. In practice, councils use these powers as a last resort measure where owners cannot be encouraged to take the necessary action themselves, or where emergency repairs to dangerous buildings are needed.

In the longer term, in line with the introduction of the new common housing standard, the Scottish Government plans to develop a new 'Help to Improve' policy approach for owners who need to support to repair and improve their homes.

Introduction

There are a number reasons why good housing conditions are important. These include, for example:1

the fact that the costs of repair can increase if problems are left untreated

some kinds of disrepair can make it harder to meet targets for fuel poverty and climate change because they prevent or reduce the value of energy efficiency improvements

some kinds of disrepair may affect the health and safety of occupiers.

Furthermore, in more extreme cases, homes in poor condition can pose a risk to anyone in the vicinity of the property, for example, from falling masonry.

In the past, Scottish Government policies aimed at improving housing quality have largely focused on individual tenures, i.e. social rented housing (registered social landlords and council housing), private rented and owner-occupied housing. However, more recent government plans include the introduction of a common housing standard covering all tenures.

Scottish Government plans for a new common housing standard

In March 2021, the Scottish Government published its long term vision for housing "Housing to 2040". One of the overriding aims is for:

all homes to be good quality, whether they be new build or existing, meaning everyone can expect the same high standards no matter what kind of home or tenure they live in

Source: Scottish Government . (2021, March). Housing to 2040. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/housing-2040-2/ [accessed 7 June 2021]

Housing to 2040 also notes:

Current housing standards allow for exceptions in some local circumstances, such as homes in rural areas, agricultural properties or hard to treat buildings. This results in the unacceptable position where those with the fewest options and the least recourse are more likely to have to live in sub-standard housing. Overall, this means we cannot guarantee that everyone has a good quality of home, regardless of whether they own it or rent it from a private or social landlord – and some homes are left behind entirely

Source:Scottish Government . (2021, March). Housing to 2040. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/housing-2040-2/ [accessed 7 June 2021]

One of the commitments made is to introduce legislation for a tenure neutral housing quality standard that would apply across all tenures (i.e. social rented, owner-occupied and private rented housing) and include agricultural properties, mobile homes and tied accommodation:

In 2021, we will consult on a new Housing Standard and how it can:

Cover all tenures and apply the same quality requirements, aiming for no exemptions.

Go beyond a minimum standard to include aspects such as being free from serious disrepair, minimum space standards, systematic future-proofing of homes for our future population and additional safety standards.

Balance quality improvement with affordability for households and the rights of property owners.

Create mechanisms to provide assistance to address substandard housing.

Following consultation, we aim to publish a draft Standard in 2023 and progress legislation in 2024/25, for phased introduction from 2025 to 2030.

Scottish Government . (2021, March). Housing to 2040. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/housing-2040-2/ [accessed 7 June 2021]

Alongside the new standard, the Scottish Government aims to introduce an enforcement framework from 2025, which could come into force in phases between 2025 and 2030, recognising that different types of homes in different places may need more or less time to achieve compliance.

A common housing standard has been under discussion for many years. The Scottish Government's 2013 Sustainable Housing Strategy included a commitment to develop proposals in 2013 for a working group/forum to consider developing a single condition standard for all tenures.4

A Common Housing Quality Standard Forum was set up in 2015 producing a series of papers on housing standards which are available online.

Energy efficiency

Recent Scottish Government policy has focused on improving the energy efficiency of homes as this contributes to the Scottish Government's priorities on fuel poverty (by ensuring that homes are more affordable to heat) and climate change (by helping to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases).

The Scottish Government has targets for homes' energy efficiency as measured by its Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating.

What is an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating?

Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) were introduced in January 2009 under the requirements of the EU Energy Performance Building Directive (EPBD). iThey provide energy efficiency and environmental impact ratings for buildings based on standardized usage.

EPCs are required when a property is either constructed, sold or rented to a new tenant.

EPCs are calculated using a SAP (Standard Assessment Procedure) to measure the energy efficiency of a building. This uses information such as the size, layout, insulation and ventilation of a dwelling and will equate to an energy rating from A to G (A is very efficient and G is very inefficient).

Information is also provided on measures which could be made to improve energy efficiency and an indication of the cost for each improvement.

The Scottish Government plans to reform the domestic EPC framework. This follows concerns, highlighted by the Climate Change Committee and previous consultations, about the effectiveness of using EPCs as a basis to set standards.1

The Scottish Government has been consulting on the first part of reform by proposing a change to the way information, already gathered as part of an EPC assessment, is displayed on the EPC. The proposed change to the EPC also includes the creation of a new metric - Energy Use Rating.1

Energy efficiency requirements

However, the Scottish Government's Climate Change Plan update and draft Heat in Buildings Strategy proposed more ambitious plans, bringing forward the target end date for energy efficiency standards by 5 years to 2035 and proposing to introduce standards for heating not previously included in the Energy Efficient Scotland Route Map.12

The Scottish Government's draft shared policy programme with the Scottish Green Party brought forward the target date to 2033.

The finalised Heat in Buildings Strategy, published on 7 October 2021, confirmed the Scottish Government's plans. Some of the key commitments regarding a new regulatory framework include3:

It is essential that homes and buildings achieve a good standard of energy efficiency, and that poor energy efficiency is removed as a driver of fuel poverty. Where technically and legally feasible and cost-effective, by 2030 a large majority of buildings should achieve a good level of energy efficiency, which for homes is at least equivalent to an EPC Band C, with all homes meeting at least this standard by 2033.

There will be some circumstances where this is not possible. In such cases, we would expect these properties to achieve the highest standard possible, installing those measures recommended by the EPC assessment as being technically feasible and cost-effective for that building.

As set out in the 2018 Energy Efficient Scotland Route Map, we believe that homes with households in fuel poverty should reach higher levels of energy efficiency. We want all fuel poor households to benefit from an energy efficiency rating equivalent to EPC C by 2030 and equivalent to EPC B by 2040.

We will bring forward legislation during this Parliamentary term which, subject to devolved competence, will include regulatory proposals to require the installation of zero or very near zero emissions heating systems in existing buildings.. with all buildings needing to meet this standard no later than 2045.

Multi-tenure or mixed-use buildings under certain circumstances may be given until 2040-45 to improve both their energy efficiency and install a zero emissions heat supply, depending on the complexity involved in coordinating works and recovering costs between multiple owners, which may necessitate a ‘whole building intervention’ simultaneously covering energy efficiency and heat supply improvements.

How the energy efficiency requirements will be implemented for homes in different tenures will vary. This is explained in the remainder of the briefing.

Repairing and maintaining flats

Over a third (37%) of homes in Scotland are flats.1 Owners of flats need to co-operate to keep their blocks, and the communal parts of the building, in a good state of repair.

A programme of law reform, including the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004 ('the 2004 Act'), aimed to improve the maintenance and repair of flats.

Despite legislative reforms, the repair and maintenance of flats remains challenging. There are particular challenges in mixed tenure blocks whose numbers have increased with the right to buy and the growth of the private rented sector. Some of the challenges include:2345

a reluctance by owners, including private landlords, to take a long-term view and invest in their properties

affordability issues – some owners are unable to pay for repairs

outdated title deeds which create barriers to repair as, for example, it is not clear who owns what in the building and how the costs of repairs should be divided up (and owners may be unfamiliar with the default rules of the 2004 Act which apply in this situation)

lack of long term maintenance plans or adequate building insurance

difficulties in getting agreement to carry out repairs and put in place regular maintenance due to the mixed tenure of these buildings

reduction in local authority staff and resources.

A parliamentary Working Group on Maintenance of Tenement Scheme Property was established by a group of MSPs in March 2018. Its purpose was to establish solutions to aid, assist and compel owners of tenement properties to maintain their buildings. The Group's final report recommended a parliamentary bill by 2025 to introduce6:

mandatory owners’ associations, to try and involve all owners in decision-making

building reserve funds, to enable long-term saving for repairs

building surveys every five years, for regular identification of repairs issues.

In late 2019, the Scottish Government responded to the Group’s report, agreeing, with some caveats, that action was needed.7

In Housing to 2040, the Scottish Government indicated that it will:

... act on the recommendations of the Parliamentary Working Group on Tenement Maintenance, and we will investigate ways to encourage behaviour change which is most cost-effective for owners in the longer term

Scottish Government . (2021, March). Housing to 2040. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/housing-2040-2/ [accessed 7 June 2021]

However, it is not entirely clear yet if this will involve the changes to legislation in the timescale the working group were calling for.

The SPICe Briefing Flats - Management, Maintenance and Repairs provides further information on the law and policy associated with issues regarding repair and maintenance of flats.9

Scottish House Condition Survey

The key source of information on the physical condition of housing in Scotland is the Scottish House Condition Survey (SHCS), which is part of the Scottish Government's Scottish Household Survey. 1

The SHCS is a sample survey consisting of a physical inspection of dwellings by surveyors and an interview with householders. The interview covers a range of topics, including household characteristics, tenure, satisfaction with home, health status and income.

The Scottish Government also provides local authority tables each containing three years of data. All the data from the survey is available on the Scottish Government website.

Scottish House Condition Survey 2019 findings

This part of the briefing highlights certain key findings from the 2019 SHCS.1

To provide some context to these statistics, there are an estimated 2.5 million households in Scotland. Of these, 62% live in owner-occupied homes, 24% live in social rented housing and 14% live in private rented housing.

Table 1 shows that around one fifth (19%) of Scotland's homes are relatively old, being constructed pre-1919 while a quarter of homes were built after 1982.

In general, older homes, particularly those built pre-1919, are more likely to have some disrepair, based on various measures, and are less energy efficient compared to newer homes.

| Age of dwelling | Type of Home | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detached | Semi-detached | Terraced | Tenement | Other flats | TOTAL | |

| pre-1919 | 5% | 2% | 3% | 7% | 2% | 19% |

| 1919-1944 | 2% | 3% | 1% | 1% | 4% | 11% |

| 1945-1964 | 1% | 6% | 7% | 4% | 3% | 21% |

| 1965-1982 | 5% | 4% | 7% | 4% | 2% | 22% |

| post-1982 | 10% | 5% | 3% | 7% | 2% | 27% |

| Total | 23% | 20% | 21% | 24% | 13% | 100% |

Levels of disrepair and energy efficiency

The SHCS measures disrepair for a wide range of different building elements ranging from aspects of roofs and walls to chimney stacks, internal rooms and common parts of shared buildings like access balconies and entry doors.

In 2019:

52% of homes had some disrepair to critical elements. The critical elements are those which are central to its wind and water tightness, structural stability and preventing deterioration of the property. They include, for example, roof covering and structure and external doors and windows. Overall, this is an improvement of 5 percentage points on 2018, when 57% of homes had disrepair to critical elements, but a similar level to 2017 (50%).

Of these homes with disrepair to critical elements:

Less than half (19% of all homes) were in a state of urgent disrepair. Urgent disrepair means immediate repair is needed to prevent further damage or where the building poses a health and safety risk to occupants. This is only assessed for external and common elements of a building.

Only a small number of homes (1% of all homes) had extensive disrepair (covering at least a fifth of the building element area) to critical elements.

18% of homes had disrepair only to non-critical elements. This means any damage to a non-critical element, such as skirtings and internal wall finishes, staircases, boundary fences or attached garages, which requires some repair beyond routine maintenance.

Housing association stock is generally in better condition than dwellings in other tenures.

Around 91% of homes were free from any form of condensation or damp. This rate has been stable in recent years but represents an overall improvement from 86% in 2012.

Energy efficiency

Scottish homes are gradually becoming more energy efficient. In 2019, over half (51%) of the homes had an EPC rating of C or better, up 27 percentage points since 2010. Over the same period, the proportion of homes in the lowest EPC bands, E, F and G, has dropped 15 percentage points: 27% of properties were rated E, F or G in 2010 compared with 12% in 2019.

Housing in the social sector tends to be more energy efficient than the owner-occupied or private rented sector. It appears that this could be driven by the Scottish Housing Quality Standard and the Energy Efficiency Standard for Social Housing, which introduced minimum energy efficiency levels for social housing.

House condition standards overview

All new buildings, as well as substantially refurbished ones, must meet the relevant building standards regulations at the time the building warrant was approved. This briefing does not cover these building standards in detail.

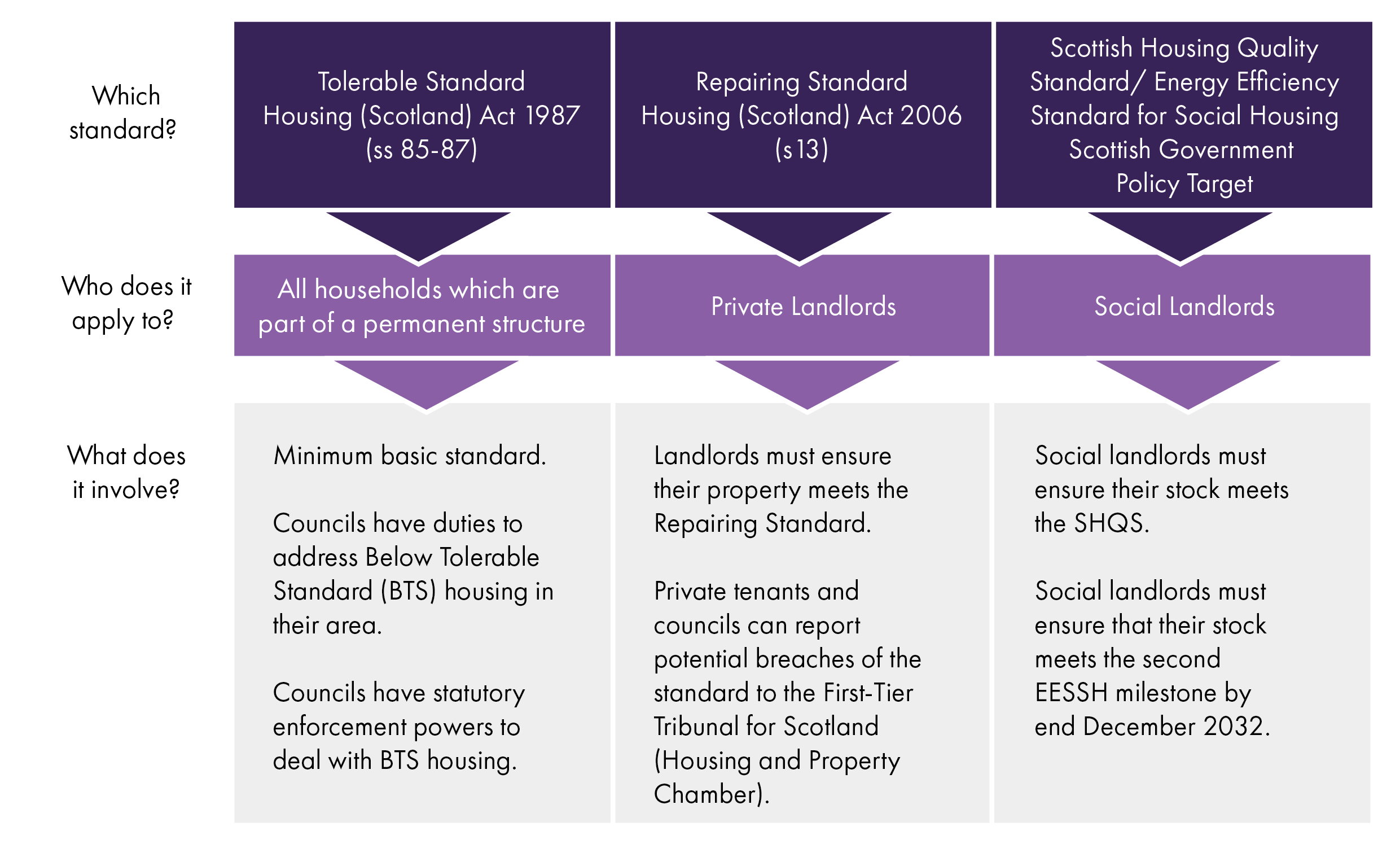

Figure 1 provides information on the main housing standards in place. In general, while there are some similarities between the standards and some changes have been made, such as aligning the Repairing Standard for private landlords more closely with social housing standards, the basic minimum Tolerable Standard remains the standard that applies to homes in all tenures.

The most extensive condition requirements are placed on social landlords. Social landlords are also subject to a greater degree of regulation compared to private landlords.

The remainder of this section of the briefing provides more details on these standards and plans for change.

The Tolerable Standard

The Tolerable Standard was first introduced in 1969 and is now set out in the Housing (Scotland) Act 1987.i It provides a basic 'condemnatory' standard that applies to housing in all tenures. If a home is below the Tolerable Standard (BTS), it is considered to be unfit for human habitation.

Relatively few homes in Scotland are below the Tolerable Standard. In 2019, approximately 2% of all homes (around 40,000 homes) fell below the Tolerable Standard. 1

The Tolerable Standardii

A house meets the tolerable standard if it:

is structurally stable

is substantially free from rising or penetrating damp

has satisfactory provision for natural and artificial lighting, for ventilation and for heating

has satisfactory thermal insulation

has an adequate piped supply of wholesome water available within the house

has a sink provided with a satisfactory supply of both hot and cold water within the house; has a water closet or waterless closet available for the exclusive use of the occupants of the house and suitably located within the house

has a fixed bath or shower and a wash-hand basin, each provided with a satisfactory supply of both hot and cold water and suitably located within the house

has an effective system for the drainage and disposal of foul and surface water

in the case of a house with an electrical supply, complies with the relevant requirements in relation to the electrical installations;

"the electrical installation" is the electrical wiring and associated components and fittings, but excludes equipment and appliances;

"the relevant requirements" are that the electrical installation is adequate and safe to use

has satisfactory facilities for the cooking of food within the house

has satisfactory access to all external doors and outbuildings.

Councils have various duties and powers in relation to the Tolerable Standard. Councils:

have a duty to close (meaning occupation is not allowed), demolish or bring up to standard all houses in their area which do not meet the tolerable standardiii

must set out in their local housing strategy how they will comply with this dutyiv

have powers to enforce the Tolerable Standard (they can serve owners with a 'work notice' requiring them to carry out the necessary work, a closing order or a demolition notice).

The 1987 Act does not place any duties on homeowners to meet the Tolerable Standard. However, other housing legislation requires homes let by private landlords to meet the Tolerable Standard. Scottish Government policy also requires homes let by social landlords to meet the Tolerable Standard.

Therefore, this means that owner-occupiers are only required to meet the Tolerable Standard when they are directed to do so by a council.

However, there are a range of other circumstances where repair work might be carried out by owner-occupiers that help a building, or part of a building, meet the Tolerable Standard. These include where:

owners are required to maintain and repair a property under that property's title deeds

owners are in a building containing flats and a majority of owners decide to do repair work under the Tenement Management Scheme (TMS), contained in the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004 ('the 2004 Act')

an owner in a building containing flats considers the repairs constitute 'emergency work' under the TMS - that owner would then go ahead and carry out repairs (without the agreement of other owners) and attempt to recoup the costs via court action from other owners later

an owner in a building containing flats might also enforce, through court action, the duty to maintain to provide support and shelter, contained in section 8 of the 2004 Act.

See SPICe Briefing Briefing Flats - Management, Maintenance and Repairs for further information on the above points.2

Future changes to the Tolerable Standard

From 1 February 2022, the Tolerable Standard will be amended to include ceiling mounted and interlinked smoke and heat alarms and, where appropriate, carbon monoxide alarms.

These changes stem from a Scottish Government consultation on Fire and smoke alarms in Scottish homes1 following the Grenfell tragedy and are implemented by 2019 secondary legislation.i

The changes were initially due to come into force on 1 February 2021 but were delayed as a result of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

From 1 February 2022, the Tolerable Standard will include2:

one smoke alarm installed in the room most frequently used for general daytime living purposes

one smoke alarm in every circulation space on each storey, such as hallways and landings

one heat alarm installed in every kitchen.

All alarms should be ceiling mounted and interlinked.

Where there is a carbon-fuelled appliance (such as boilers, fires (including open fires) and heaters) or a flue, a carbon monoxide detector is also required which does not need to be linked to the fire alarms.

Private landlords should already be meeting these requirements as it is included in the Repairing Standard. All new build homes, have also been required to meet the above fire safety standards since October 2010.

As explained earlier, the legislation governing the Tolerable Standard does not place any duty on owner-occupiers to to meet the Tolerable Standard,therefore it will not be a criminal offence for owner-occupiers not to meet the standard.

The Scottish Government has published information about the requirements on its website, including on how compliance will be monitored.

Scottish Government guidance also sets out the expectation that councils should only use their enforcement powers where it is 'proportionate, rational and reasonable':

... it is expected that any intervention is proportionate, rational and reasonable. Local authorities are to consider the cost of any intervention alongside the cost of assisting owners to bring their property up to the minimum standard for satisfactory fire detection. As a general rule it is preferable that owners should carry out necessary works on a voluntary basis rather than as a result of enforcement action..

Source: Scottish Government. (2019, February). Tolerable Standard Guidance: Satisfactory Fire Detection and Satisfactory Carbon Monoxide Detection. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/advice-and-guidance/2019/02/fire-and-smoke-alarms-tolerable-standard-guidance/documents/tolerable-standard-guidance-satisfactory-fire-and-carbon-monoxide-detection/tolerable-standard-guidance-satisfactory-fire-and-carbon-monoxide-detection/govscot%3Adocument [accessed 04 February 2019]

Private rented housing - the Repairing Standard

Most private landlords in Scotland have to ensure that the property they let meets the Repairing Standard.

Part 4 of the Housing (Scotland) Act 2006 governs the application of the Repairing Standard.

The Repairing Standardi

A house meets the Repairing Standard if:

it meets the Tolerable Standard

it is wind and watertight and reasonably fit for human habitation

the structure and exterior of the house (including drains, gutters and external pipes) are in a reasonable state of repair

gas and electricity supply equipment works properly

fixtures, fittings and appliances provided by the landlord (like carpets, light fittings and household equipment) work properly

furnishings supplied by the landlord are safe

there are satisfactory fire and smoke detectors

there are satisfactory carbon monoxide alarms.

Note that from 1 Feb 2022, the fire and smoke detectors and carbon monoxide alarm requirements will removed. From that date, those requirements will be contained in the definition of the Tolerable Standard, which all private landlords have to meet.

Private landlords must also carry out electrical safety inspections at least once every five years. The electrical safety inspection has two separate elements:

an Electrical Installation Condition Report (EICR) on the safety of the electrical installations - this must be conducted by a “suitably competent” person

a Portable Appliance Test (PAT) on portable appliances.

The Scottish Government has issued statutory guidance on electrical safety which explains these requirements.1 There is also guidance on satisfactory provision for detecting and warning of fires2 and guidance on the provision of carbon monoxide alarms.3

The Tenement Management Scheme, contained in the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004, is a fallback scheme for managing and maintaining blocks of flats. It can be used when the flat owners' title deeds have gaps or defects and provides for decision-making by majority rule.

Enforcing the Repairing Standard

If a tenant thinks that their property does not meet the Repairing Standard, they should report the problem to their landlord and give them a 'reasonable time' to fix the problem. The legislation does not define what a reasonable time may be.

If the landlord does not fix the problem, the tenant can make an application to the First-tier Tribunal for Scotland (Housing and Property Chamber) ('the Tribunal') for a decision on whether the landlord has complied with the legislation. Councils, as a third party, can also make applications to the Tribunal, in the same way as the tenant.

If the Tribunal decides that a landlord has failed to comply with the Repairing Standard and has the necessary rights to carry out the work, then the Tribunal must make a Repairing Standard Enforcement Order (RSEO) requiring the landlord to carry out the work. It is a criminal offence to fail to comply with a RSEO. When a landlord fails to comply with a RSEO, the Tribunal reports this to the police and it is for the prosecuting authorities to decide if cases should proceed to court.1

The Tribunal also lets the the relevant council know if a RSEO has been issued. Councils can use this information to inform their decisions about private landlord registration. Any evidence relating to a breach of housing law (for example, failure to comply with the Repairing Standard) may be taken into account by the council when deciding if the landlord is 'fit and proper' to let houses. If a council decides a landlord is not a fit and proper person, they could be removed from the private landlord register or refused registration.

If a private landlord is having trouble gaining access to the property they let to meet the Repairing Standard, they can apply to the Tribunal for assistance in exercising their right of entry to the property for this purpose.

Further information on the process is available on the Tribunal's website. There is also a sample letter that tenants can use to send to their landlord.

Number of Repairing Standard applications made to the Tribunal

The Scottish Tribunals annual report notes that in 2019/20, the Housing and Property chamber received 179 Repairing Standard applications, very slightly below the figure for the previous year. Nearly three-quarters of these (73%) were made by tenants, while around a quarter (27%) were made by third parties.

Most third-party applications came from a small number of councils which have been particularly proactive. Applications were received from 10 of the 32 councils (Falkirk, Dumfries and Galloway, Renfrewshire and Glasgow City councils made the most applications).1

Of the 178 Repairing Standard applications closed or decided by the Tribunal in 2019/20, 85 RSEOs were issued. The remaining applications were either rejected or abandoned, or the Tribunal decided that the landlord had complied with the Repairing Standard duty.

Future changes to the Repairing Standard

Further changes are being made to the Repairing Standard to bring it closer to the standards required for social rented housing.1i

From March 2024, the Repairing Standard will include the following requirements:

safely accessible food storage and food preparation space

space heating must be by means of a fixed heating system

where the house is a flat in a tenement, the tenant is able to safely access and use any common parts of the tenement, such as common closes

common doors must be secure and fitted with a satisfactory emergency exit lock

electrical installations must include a residual current device (a device to reduce the risk of electrocution and fire by breaking the circuit in the event of a fault).

The modification regulations also lay down who the Repairing Standard applies to and:

clarify that houses let for a holiday for less than 31 days are not subject to the Repairing Standard

provide that, from March 2027, tenancies on agricultural land will be required to meet the Repairing Standard.

Future private rented housing energy efficiency standards

In 2017, the Scottish Government consulted on changes to private rented housing standards1. Following that consultation, the 2018 Energy Efficient Scotland Route Map confirmed that new energy efficiency standards will apply to privately rented homes.2

Draft regulations set out the proposed requirements including that by March 2025 all tenancies in the private rented sector will need to be at least EPC band D. However, the regulations implementing the requirements were postponed due to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

In its Heat in Buildings Strategy, the Scottish Government recognised that the private rented sector has been significantly affected by the ongoing Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Therefore, regulations will now be introduced in 2025:

As a result, and to reflect the need to reduce pressure on the sector, we are removing this step and now working with the sector to introduce regulations in 2025. These will require all private rented sector properties to reach a minimum standard equivalent to EPC C, where technically feasible and cost effective, at change of tenancy, with a backstop of 2028 for all remaining existing properties, in line with the direction provided by the Climate Change Committee.

Scottish Government . (2021, October 7). Heat in Buildings Strategy : Achieving Net Zero Emissions in Scotland's Buildings. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2021/10/heat-buildings-strategy-achieving-net-zero-emissions-scotlands-buildings/documents/heat-buildings-strategy-achieving-net-zero-emissions-scotlands-buildings/heat-buildings-strategy-achieving-net-zero-emissions-scotlands-buildings/govscot%3Adocument/heat-buildings-strategy-achieving-net-zero-emissions-scotlands-buildings.pdf [accessed 11 October 2021]

Private landlords could benefit from a Scottish Government funded loan to make energy efficiency improvements. Further details are on the Home Energy Scotland website.

Social housing standards

All social landlords must ensure that the homes they let are wind and watertight and in all other respects reasonably fit for human habitation.i

In addition to this basic legislative requirement, social landlords have to ensure that their homes meet the Scottish Housing Quality Standard and Energy Efficiency Standard for Social Housing.

Social housing: Scottish Housing Quality Standard (SHQS)

The SHQS was introduced by the Scottish Government in February 2004. It is a policy target and does not have a legislative basis. It consists of a set of broad criteria, covering specific elements, which must all be met if the property is to pass SHQS.

The broad criteria specify that social housing must be:

above the statutory Tolerable Standard

free from serious disrepair

energy efficient

equipped with modern facilities and services

healthy, safe and secure.

The Scottish Government's target was for all social landlords to ensure that all their homes pass the SHQS by April 2015. Since then, the expectation is that all homes will meet the standard and this is set out in the Scottish Social Housing Charter.

In exceptional circumstances, exemptions or abeyances from the SHQS may be allowed:

Exemptions can be made when the landlord believes it is not possible to meet an element of the standard for technical, disproportionate cost or legal reasons.

An 'abeyance' can arise when work cannot be done for ‘social’ reasons relating to tenants’ or owner-occupiers’ behaviour, for example, where owner-occupiers in a mixed tenure block do not wish to pay for their share of works to common parts.1

The Scottish Housing Regulator monitors social landlords' performance against the charter and it has powers to intervene if landlords are failing to meet the standards and outcomes in it.

The Regulator reports that, as at the end of March 2021, 91% of social housing met the SHQS.2This is based on social landlords' self-assessments against the outcomes and objectives set out in the charter. The Regulator also comments that compliance with the SHQS fell from 94% in the previous year which is likely to be the result of the slowing, or for some, halting of landlords’ investment programmes due to the public health restrictions brought in to tackle the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.3

Energy Efficiency Standard for Social Housing (EESSH)

It sets a single minimum Energy Efficiency rating for social landlords to achieve which varies depending on the house type and the fuel type used to heat it. The ratings reflect that some house types can be more or less challenging to improve than others.

EESSH first milestone

The first EESSH milestone (EPC D or C depending on fuel and dwelling type) had to be met by social landlords by December 2020.

The Scottish Housing Regulator, which is responsible for monitoring social landlords' progress towards the EESH, reports that 89% of social rented homes were compliant with the EESSH at the end of March 2021. The Regulator reports that it was likely that the impact of the pandemic has constrained landlords’ capacity to fully implement investment programmes.1

EESSH second milestone

Following a review of the first milestone, the then Minister for Housing, Local Government and Planning, Kevin Stewart MSP, agreed a second EESSH2 milestone in June 2019:

EESSH 2

All social housing meets, or can be treated as meeting, EPC B (Energy Efficiency Rating), or is as energy efficient as practically possible, by the end of December 2032 and within the limits of cost, technology and necessary consent.

No social housing should be re-let below EPC Band D from December 2025, subject to temporary specified exemptions.

The EESSH does not prescribe specific energy efficiency measures so social landlords are free to meet the EESSH minimum ratings as they see fit, using any available measures. These measures could include, for example, installing condensing boilers, double/secondary glazing or loft insulation top-up. Further information is contained in Scottish Government guidance for social landlords.2

A report published by the Scottish Federation of Housing Associations (SFHA) has estimated that it would cost around £2 billion for housing associations to meet EESH2 but it would only reduce the total percentage of households in fuel poverty from 38% to 29%. A number of challenges in meeting the EESSH 2 were identified including funding, measurement methods, and timescales. The challenges of upgrading specific property types such as a Victorian or sandstone tenements, pre-1919 or older properties, off-gas properties, mixed-tenure properties (and those with restrictions on upgrades - listed, conservation areas, World Heritage sites) were also highlighted.3

The Scottish Government proposes to review the EESSH2 in 2023. The review will include looking at progress towards EESSH2 and how the standard fits with changes needed across other tenures. In its recent report, the Zero Emissions Social Housing Taskforce recommended that the review of EESSH is brought forward earlier than 2023.4 Scottish Minister's are currently considering the Taskforce's recommendations.

The Scottish Government has established the Social Housing Net Zero Heat Fund to support social support social landlords to install zero emissions heating systems and energy efficiency measures across their existing stock.

Owner-occupied housing

Current policies on house conditions in owner-occupied homes are largely informed by the work of the Housing Improvement Task Force. This Task Force was established by the then Scottish Executive in December 2000.

The Task Force's final report, published in 2003, emphasised the responsibility of owners to maintain their own properties and took that as the starting point. It also argued that there was a need for a cultural change for this to happen:

Our starting point has been the belief that the responsibility for the upkeep of houses in the private sector lies first and foremost with their owners and that there is a need for greater awareness and acceptance by owners of this responsibility.

Scottish Government. (2013, March 13). STEWARDSHIP AND RESPONSIBILITY: A Policy Framework for Private Housing in Scotland The Final Report and Recommendations of the Housing Improvement Task Force. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.scot/Publications/2003/03/16686/19494 [accessed 04 February 2019]

Recommendations in the Task Force's reports led to legislative change via the Housing (Scotland) Act 2006. This included changes to councils' powers to deal with disrepair in private housing.

It also included the introduction of the requirement for sellers to prepare a Home Report (including a house condition survey) when they market their property for sale. One aim behind the Home Report system was that people would take into account future maintenance issues and costs when making offers to buy properties.

Some owners living in flats may employ a property manager or factor for the building. Property managers of factors typically undertake tasks including arranging repairs or maintenance to buildings and their grounds. However, they might only be asked to organise repairs when required, rather than undertake a proactive programme of ongoing maintenance. There may also still be issues with the availability of factoring companies who can undertake work for owners in rural areas.2

The property factoring sector is now regulated under the Property Factors (Scotland) Act 2011. Under this legislation, there is a Code of Conduct, setting out minimum standards of service which registered property factors have to meet. Further details on property factors and property managers is contained in the SPICe briefing Flats: Management, Maintenance and Repairs.2

The Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004 also aimed to improve the repair and maintenance of flats. The Act provides for default rules - the Tenement Management Scheme- which allow a majority of flat owners to take decisions.

A report from 2019 prepared by Professor Douglas Robertson for the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors and the Built Environment Forum Scotland, provides further background on the Task Force reports and details of the changes that stemmed from their work. The author also argues that despite the activity in this area:

...there still remains no strategic engagement with the challenge of safeguarding the condition of privately-owned property.

Robertson, D. (2019, January). COMMON REPAIR PROVISIONS FOR MULTI-OWNED PROPERTY: A CAUSE FOR CONCERN. THE PROVISIONAL REPORT TO THE ROYAL INSTITUTION OF CHARTERED SURVEYORS AND BUILT ENVIRONMENT FORUM SCOTLAND. Retrieved from https://www.befs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Common-Repair-Provisions-for-Multi-Owned-Property-in-Scotland-2019.pdf [accessed 31 January 2019]

Although the Task Force's proposals were made almost 20 years ago, it appears that the cultural change has not taken place to the extent originally envisaged by the Task Force. Another report prepared by Professor Douglas Robertson for Built Environment Scotland concludes that:

Experience to date,also throughout Scotland, shows that after more than a decade there is still a great deal of work needed to embed this major culture shift. Significant numbers of owners and, in particular, private landlords are still failing to engage properly with their responsibilities.

Robertson, D. (2019). Why flats fall down: Navigating shared responsibilities for their repair and maintenance.. Retrieved from https://www.befs.org.uk/resources/publications/why-flats-fall-down/ [accessed 22 July 2021]

Some of the things that might need to happen to facilitate this culture shift could include, for example, encouraging owners to give greater priority for structural work over refurbishments and cosmetic upgrades and to promote routine maintenance as the most effective way to reduce disrepair. 6

Energy efficiency standards for owner-occupiers

As covered earlier, the Tolerable Standard is currently the only condition standard that applies to owner-occupied housing, although, in future, owner-occupiers will have to reach minimum energy efficiency standards and the Scottish Government's proposed common housing standard.

The Scottish Government's approach to date has been to encourage owner-occupiers to voluntarily improve the energy efficiency of their homes and has offered advice and incentives to do so.

Improving energy efficiency in owner-occupied homes was consulted on in 2019,1 and in the draft Heat in Buildings strategy. The finalised Heat in Buildings Strategy set out the Scottish Government's plans to introduce regulations to require owner-occupiers to meet certain energy efficiency standards at key trigger points:

We will set out and consult on detailed proposals for introducing regulations for minimum energy efficiency standards for all owner-occupied private housing. It is envisaged that these will be set at a level equivalent to EPC C where it is technically feasible and cost-effective to do so. This will apply at key trigger points.

We propose to introduce regulations from 2023-2025 onwards, and all domestic owner-occupied buildings should meet this standard by 2033. This brings forward the previously proposed backstop from 2040 to 2033. Where it is not technically feasible or cost-effective to achieve the equivalent to EPC C rating, we propose that a minimum level of fabric energy performance through improvement to walls, roof, floor and windows, as recommended in the EPC, would apply.

Source: Scottish Government . (2021, October 7). Heat in Buildings Strategy : Achieving Net Zero Emissions in Scotland's Buildings. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2021/10/heat-buildings-strategy-achieving-net-zero-emissions-scotlands-buildings/documents/heat-buildings-strategy-achieving-net-zero-emissions-scotlands-buildings/heat-buildings-strategy-achieving-net-zero-emissions-scotlands-buildings/govscot%3Adocument/heat-buildings-strategy-achieving-net-zero-emissions-scotlands-buildings.pdf [accessed 11 October 2021]

The above quote refers to the standards to be met at 'key trigger points.' In its previous consultation, the Scottish Government had proposed the point of sale, and potentially major renovation, as appropriate trigger points for a property to meet the required standard.1

As only around 42% of owner-occupied homes are currently estimated to meet EPC C level or above, meeting the required standards will be challenging.4

Achieving the standard is likely to require a mix of grants and low-cost loans as well as private investment by owner-occupiers.

The Scottish Government acknowledges that the cost implications, and how to fund the work needed to meet the standard, will be a key question for owners. One of the commitments in the strategy is to introduce regulation in a way that will not increase fuel poverty.2

Councils' powers to address poor house conditions

Councils have powers to address poor house conditions in their area, although most of these powers are discretionary. In practice, councils will try to influence owners to improve the condition of their home and will only use their statutory powers as a last resort.

Table 2 summarises the main powers available to councils to deal with poor housing conditions in their areas (note that this is not a comprehensive list but instead sets out the most relevant issues for this briefing).

| Name of power(associated statutory provision) | Description |

| Housing Renewal Area (HRA)(Part 1, Chp 1 Housing (Scotland) Act 2006) | Powers to deal with poor quality housing issues on an area basis. If it decides that it wants to designate an HRA, the council must draw up a plan to improve the condition and quality of housing in the area. |

| Demolition Notice (Housing (Scotland) Act 2006, section 33 and 34) | Demolition notices can be used to implement an HRA action plan where a house in serious disrepair ought to be demolished. |

| Work notice(Housing (Scotland) Act 2006, sections 30 and 68) | Requires an owner to bring house which is sub-standard into a reasonable state of repair. A house is sub-standard if it is below the Tolerable Standard; in a state of serious disrepair; or in need of repair and likely to deteriorate rapidly or damage other premises if nothing is done to repair it. A work notice can also be served where work is needed to improve the safety and security of any house. |

| Demolition order and closing orders (for below Tolerable Standard housing)(Housing (Scotland) Act 1987 ) | Councils can serve a demolition order or closing order (meaning occupation is not allowed) if a home not meeting the standard is not brought up to this standard within a reasonable time frame. See also under ‘Work notice.' |

| Missing Share(Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004 (section 4A)(Housing (Scotland) Act 2006, section 50)(Registered Social Landlords (Repayment Charges) (Scotland) Regulations 2018; made under the Housing (Scotland) Act 2006, Section 174A ) | Councils can pay an owner's share of scheme costs where the owner is unable or unwilling to do so, or cannot be identified or found. Broadly speaking, the section 4A power can be used where there has been an owner decision under the Tenement Management Scheme or title deeds but does not require a maintenance account to have been set up by the owners. On the other hand, the 2006 powers does require a maintenance account to have been set up. The regulations made under section 174 of the 2006 Act allows registered social landlords to recover a missing share by means of a repayment charge. |

| Maintenance order(Housing (Scotland) Act 2006, section 42) | A council may issue a maintenance order to require the owner of a house to prepare a maintenance plan. The purpose of the order is to get the house to a reasonable standard of maintenance over a period of not more than five years.As the order can apply to commonly owned facilities or areas, this type of order was particularly aimed at buildings containing flats. |

| Defective building notice(Building (Scotland) Act 2003, section 28) | Requires an owner to rectify defects to bring the building into a reasonable state of repair, having regard to its age, type and location. It could be used, for example, in a case where a leaking roof risked damaging the structure of a building, to require the owner to make it resistant to moisture. |

| Dangerous building notice(Building (Scotland) Act 2003, section 29) | If a council considers a building to be dangerous to its occupants or to the public, it must take action to prevent access to the building and to protect the public.Where urgent action is necessary it can carry out the necessary work, including demolition (and recover the costs from the owner). Otherwise it must serve a dangerous building notice ordering the owner to carry out work which the council considers necessary to remove the danger (again, this work can include demolition). |

| Enhanced enforcement area (EEA)(Secondary legislation made under the Housing (Scotland) Act 2014) | A council can apply to Scottish Ministers for an area to be classified an EEA. The council then has extra powers to tackle housing problems such as poor quality private rented housing. An EEA is designed for exceptional circumstances. Govanhill in Glasgow has Scotland’s two EEAs designated to date. |

| City of Edinburgh Council(City of Edinburgh District Council Order Confirmation Act 1991) | The City of Edinburgh Council has local powers to serve notices requiring owners to carry out repairs. If the owner does not carry out the required repairs the council can carry out the repairs and recover the costs of doing so. |

In some situations, when a council has carried out repair, demolition or maintenance work on behalf of an owner, it can charge the owner for doing the work. As carrying out the work will involve upfront costs for the council, there may be a disincentive for a council to do this.

Councils can also use a 'repayment charge' to recover costs incurred.1 A repayment charge is a legal document registered in one of the property registers (i.e. the Register of Sasines or the Land Register). This charge requires the owner to pay back the sum owed in instalments to the council over a period between five and thirty years, although it can be paid back earlier if the owner chooses to do so.

Sources of support for improving house conditions in private housing

Owners are responsible for maintaining their own homes. However, some owners can find it difficult to arrange, or to pay for, repairs and improvements.1

There are some sources of support for owners available including councils' Schemes of Assistance and other types of support.

Councils' Schemes of Assistance

The Housing (Scotland) Act 2006 requires councils to publish a statement about the circumstances in which they provide assistance for housing purposes. i This is known as the Scheme of Assistance. Councils can provide assistance to owners for house repairs, improvements, adaptations and construction, as well as the acquisition or sale of a house.

The 2006 Act provides that councils must provide assistance (although not necessarily financial assistance) in the following circumstances:

for work required by a work notice, including to any owners of non-residential property in the block (e.g. shops on the ground floor of a tenement block)

for work required to make a house suitable for a disabled person (where this is deemed essential), or to reinstate one that has been previously adapted for this purpose. Where the work is required to make a house or flat suitable for a disabled person by giving it standard amenities (toilet, bath, shower, basin or sink), the assistance must be in the form of a grant.

Apart from these defined circumstances, any other assistance will be at the discretion of the council. Councils will decide what kinds of assistance to provide on the basis of local priorities and budgets.

The assistance can take various forms, including loans, practical assistance and grants. Practical assistance could include, for example, issuing correspondence to, or attending meetings arranged by, owners who share responsibility for common repairs or helping owners to understand quotes for work.

In line with the emphasis on owners taking responsibility for the upkeep of their own homes, Scottish Government guidance discourages the use of open ended grant programmes.1

In practice, where councils offer grant support this is likely to be limited to certain types of repairs or where the work will assist with a council's wider strategic objectives such as area regeneration. Constituents should be advised to contact their local council for further information on their policies.

Scottish Government statistics indicate that around £38 million was spent on councils' Schemes of Assistance in 2018-19. Of this, the majority (around £22 million) was spent on grant assistance for disabled adaptations. A further £6.8 million was spent on other grant assistance, more than half of which was spent by Glasgow City Council.2

Other sources of information and support

Other sources of information and support include:

The Under One Roof website provides advice on repairs and maintenance for flat owners in Scotland and has advice on paying for repairs including information on the different types of loans available.

Care and Repair services: offers advice and assistance to enable people to repair, improve or adapt their homes. The service is available to owner-occupiers, private tenants and crofters who are aged over 60 or who have a disability and is available in most council areas. Further information is available on the Care and Repair Scotland website.

The City of Edinburgh Council has published a shared repairs tenement toolkit which may be useful for people living in flats.

Scottish Government plans for support for repairs and maintenance

The Scottish Government's Housing to 2040 route map takes the general view that home repairs and maintenance are a homeowner's responsibility and sets out the government's plans to:

... take action to support proactive approaches to repair and maintenance, which should help owners to avoid high-cost interventions later.

Source: Scottish Government . (2021, March). Housing to 2040. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/housing-2040-2/ [accessed 7 June 2021]

It plans to:

commission research on the costs of maintenance and current incentives and disincentives to investing in maintenance

act on the recommendations of the Parliamentary Working Group on Tenement Maintenance and investigate ways to encourage behaviour change which is most cost-effective for owners in the longer term

develop a new ‘Help to Improve’ policy approach for owners who need support to improve their homes. It is envisaged that this will be available to be in place by the time the new common housing standard is introduced from 2025.