Addressing the nature crisis: COP15 and the global post-2020 Biodiversity Framework

This briefing provides an introduction to biodiversity loss - the 'nature crisis' happening both in Scotland and globally. It outlines international approaches to address the nature crisis, notably the UN Convention on Biological Diversity and its upcoming 15th Conference of the Parties (COP15) where a new global biodiversity governance framework, goals and targets for the next ten years are expected to be agreed. Expectations for the outcomes of COP15 are outlined, as well as how these may guide the Scottish Government's post-2020 biodiversity strategy and other relevant policy areas.

Summary

This briefing explores why we need biodiversity, what is driving its unprecedented decline globally and in Scotland, and solutions to the nature crisis ahead of COP15: the major intergovernmental conference tasked with agreeing the next set of 10-year targets to halt and reverse nature's decline. That conference is set to be hosted by China, and held in two parts. The first part is to be held online from 11-15 October 2021, and the second part is to be held in person in Kunming from 25 April to 8 May 2022. The Conference was postponed from 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

All previous international targets for biodiversity have been missed and research shows that "urgent and transformative action" is required to halt the biodiversity crisis.

The Scottish Government has been involved in international negotiations ahead of COP15, notably via the Edinburgh Process in 2020, and has committed to publishing a new biodiversity strategy within one year of COP15.

Delivering on biodiversity targets will likely require coherence across a range of policy areas - including policies on land use, fisheries, forestry, climate change and national planning.

COP26 and COP15 - a big year for the planet

This briefing focuses on what is expected from COP15 - the next major intergovernmental conference on biodiversity loss. It explains what biodiversity is, the key threats facing nature, and what that means for people. Finally, it looks at how an international framework might be translated into Scottish policy, and which domestic policy areas are likely to be relevant.

Global environmental challenges such as biodiversity loss and climate change are governed at an international level by UN Conventions - international agreements that countries sign up to. Climate change is governed by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, and biodiversity loss is principally governed by the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. As part of this, nations - or 'Parties' to the conventions - meet regularly to agree shared approaches. These meetings are called Conferences of the Parties, or COPs.

The 26th COP on climate change, COP26, is due to be held in Glasgow in November 2021. The 15th COP on biodiversity, COP15, is hosted by China and will be held in two parts: an online conference in October 2021, and a face-to-face conference in Kunming in April/May 2022. Both of these COPs are highly significant. COP26 is seen as the last chance to agree measures to keep global warming to below 1.5°C. At COP15, parties are due to agree the next ten-year framework for tackling biodiversity loss. This is also seen as a crucial point for moving beyond creating policies - which so far, have failed to stem the nature crisis - to delivering effective implementation.

2021 is therefore a big year for the planet, with significant decisions due on how we tackle two of our greatest global challenges.

Biodiversity - the variety of life on Earth

An introduction to biodiversity

Biological diversity – or biodiversity – is the variety of life on earth. It includes genetic diversity within species and variation between species and ecosystems (see Figure 1 below).1 Scotland's biodiversity includes a huge variety of marine and land-based ecosystems - where living organisms interact with each other and their non-living environment1. Scotland is home to an estimated 90,000 species.3

Biodiversity is not made up of discrete components (such as a given number of different species) but also involves ecological interactions (Figure 2), delivering the natural stocks and flows that underpin ecosystem services.4 This makes biodiversity difficult to measure - because it is composed of a vast number of interlinked, interacting components. In practice, metrics like species counts are often used as indicators of how much biodiversity there is in a given place.

Humans are currently having a huge impact on other species and ecosystems. The magnitude of human impacts have increased over time and are continuing to do so6.

Biodiversity, locally and globally, is fundamental to the ability of humans to survive and thrive. Yet, accelerating rates of biodiversity loss since the Industrial Revolution now exceed limits considered safe for humanity7. This is often termed the "nature", "ecological" or "biodiversity" crisis and is closely linked to its "twin crisis" of climate change. The nature crisis is complex and aspects of it are invisible to many people, for example due to 'shifting baseline syndrome', see Box 1.

Box 1: Shifting baseline syndrome

Aspects of the nature crisis are invisible to many people, partly because reference points for measuring biodiversity loss can be misleading. If an individual were to think back to how nature looked when they were children and compare it to now, they might not think that much biodiversity loss is occurring. This is an example of what researchers have termed "shifting baseline syndrome": each new generation comes to see a degraded environment as normal and it becomes a new baseline8. Moreover, if an individual lived somewhere where there have been recent conservation successes which restore parts of nature that were previously missing, they might think that nature is doing well.

Measuring biodiversity over long timescales (greater than living memory) and large areas can tell a different story. Assessments and estimates of biodiversity are therefore important for establishing trends, understanding how biodiversity is changing across different parts of the world and what that could mean for the future.

Scotland's biodiversity

Scotland's biodiversity includes an estimated 90,000 animal, plant and microbe species.1 Some species - like the Scottish primrose and the Fair Isle wren - are found nowhere else in the world. Scotland also has a rich variety of marine and land habitats including underwater kelp forests, freshwater lochs, Caledonian pine forests, upland heath, hedgerows and urban parks.

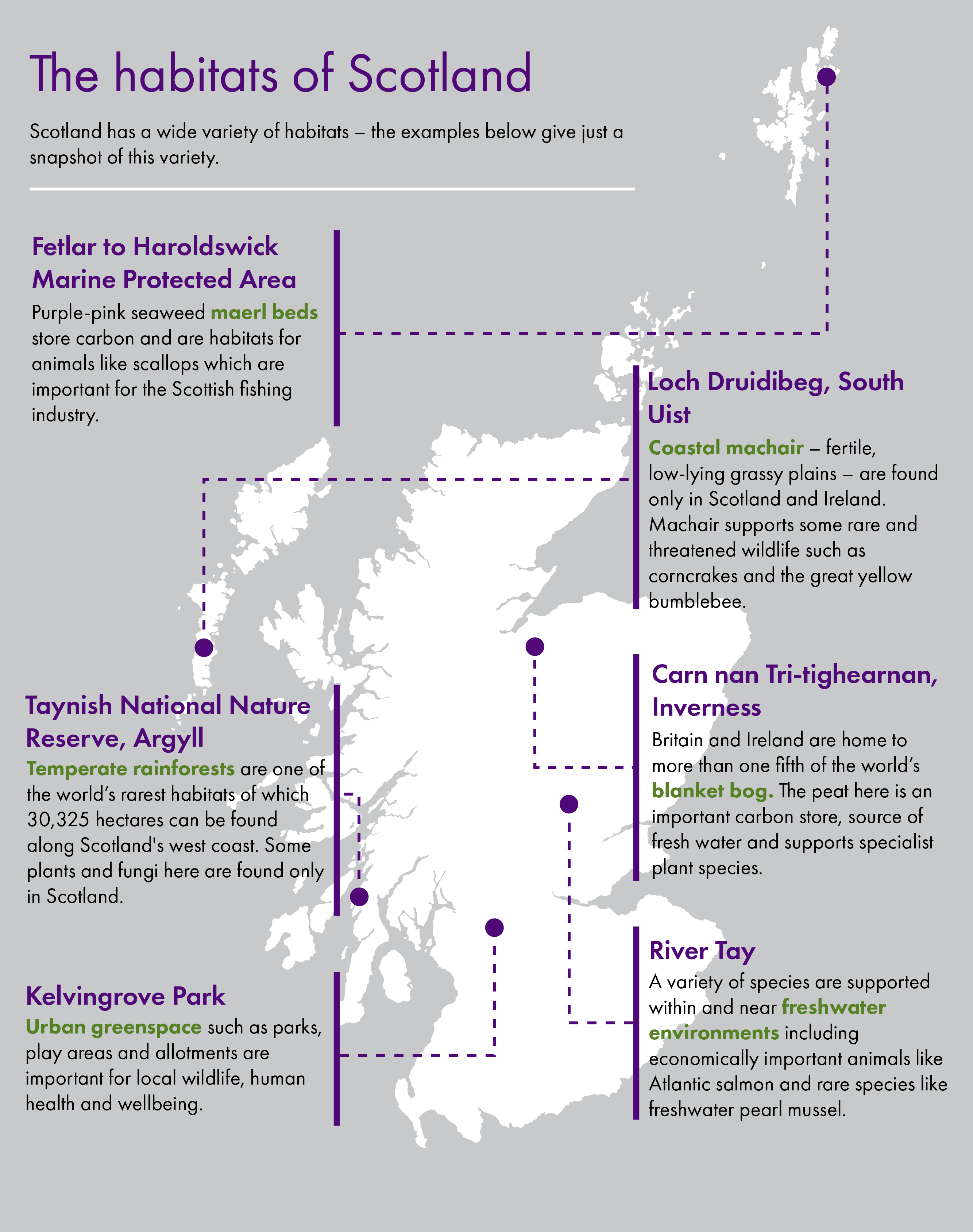

Scotland is home to the UK's most mountainous environments and 10% of Europe's coastlines. Coastal machair is one of the rarest habitats in Europe, found only in Scotland and Ireland. The map below (Figure 3) shows a few examples of Scottish habitats and the biodiversity that lives there. The Habitat Map of Scotland provides a detailed interactive map, and other pages about habitat types on NatureScot's website further describe the variety of life found in Scotland. Scotland's priority species and habitats for biodiversity conservation are catalogued in the Scottish Biodiversity List.

The value of biodiversity to people

The value of nature

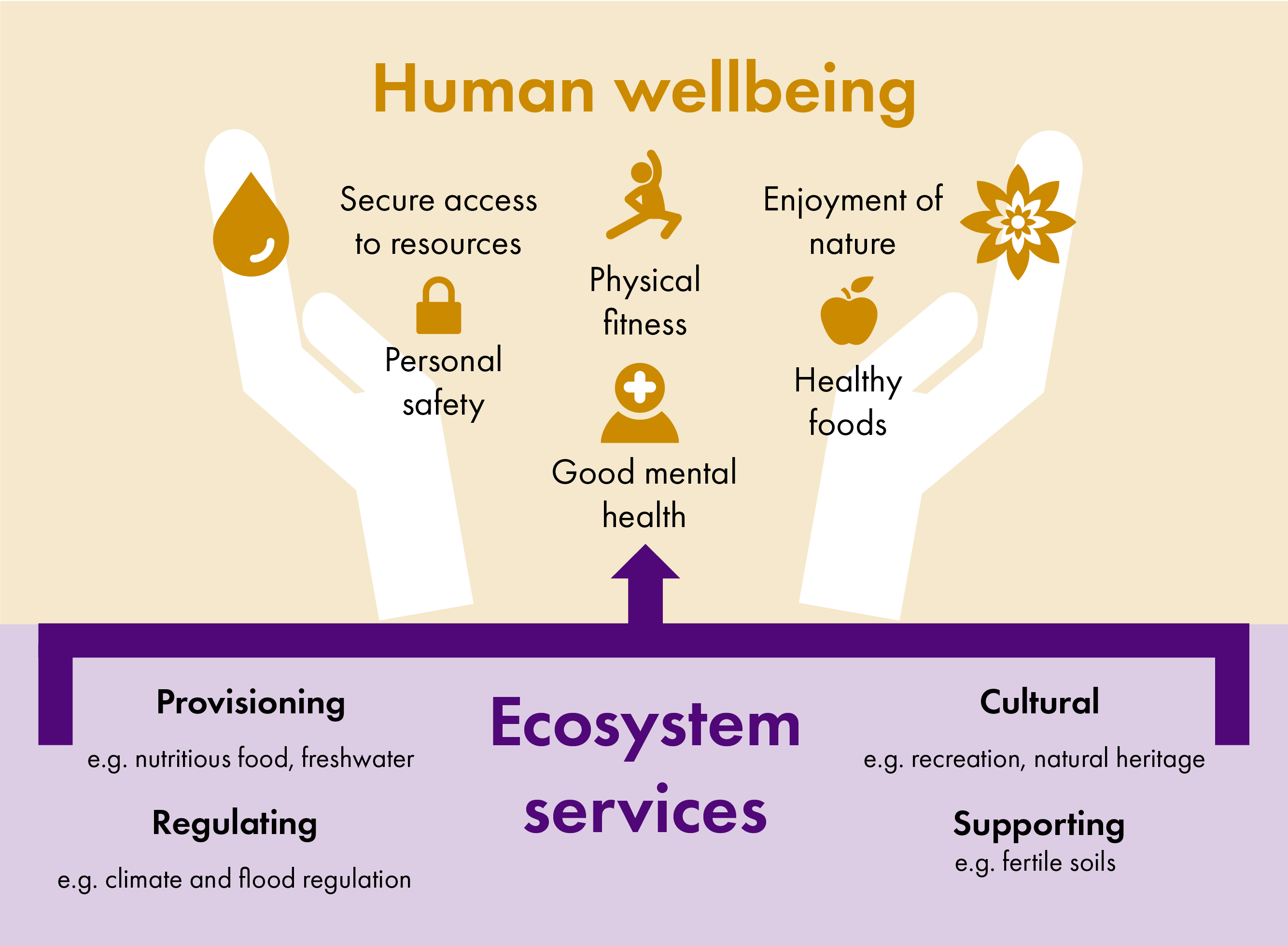

Human life depends on nature and its diversity. Nature contributes to human survival and flourishing by providing specific benefits, called "ecosystem services" (see Figure 4 below); these can also be described as "nature's contributions to people".

The value of diversity

Different ecosystems and species provide different services, and various aspects of nature are dependent on one another. For example, 35% of global crop production depends on insect pollination; in turn, a diversity of flowering plants around agricultural land is necessary to support bees and other pollinators.1 Genetic diversity underpins species diversity by providing the capacity for life to be resilient and adapt to change - buffering against extinction risk2- and genetic diversity can be harnessed by humans e.g. to improve agriculture.3

This means that while particular ecosystems, habitats and species can be especially valuable for different human purposes, the degree to which life is diverse is important too. Biodiverse environments are more likely to be productive, resilient to disturbances like extreme high temperatures4 and support a range of functions and, subsequently, benefits to humans.5 This is recognised in the "ecosystem approach" which is the primary framework for action under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. This is also applied in the current Scottish Biodiversity Strategy which takes into account interactions between parts of ecosystems, and ecosystem services in how land, freshwater and sea environments are managed.

The values of biodiversity are both local and global. A forest may provide recreation for local people, and medicinal plants that can be used across the globe. Marine and terrestrial ecosystems provide a range of different services to people living in and near them, and sequester (absorb) 60% of global greenhouse gas emissions per year, mitigating climate change6. The global value of ecosystem services has previously been estimated as 125 trillion $US per year, though there are difficulties with such estimates7 and some benefits of biodiversity - such as spiritual and aesthetic values - are less tangible and therefore difficult to measure. Values that cannot be easily quantified, however, can still be fundamental to human lives and livelihoods.

Accounting for biodiversity - from 'faulty economics' to 'inclusive wealth'

The Dasgupta Review - an independent, global review on the Economics of Biodiversity published in February 2021 - highlights that mainstream measures of economic value are incomplete and misleading because they exclude nature. Rather, economies are embedded in, cannot be divorced from, and cannot overcome their dependence on, nature5.

Excluding nature from measures of economic health (such as valuing in terms of Gross Domestic Product, GDP, alone) is described by economist Professor Sir Partha Dasgupta as being "based on a faulty application of economics"5. Measuring development by GDP alone excludes a huge proportion of an economy's valuable assets, as well as consideration of the way the value of those assets can diminish, such as through biodiversity loss. Even monetary valuations of nature are likely to be underestimates because humans could not survive without natural ecosystems and processes providing the air we breathe, the water we drink and the food we eat. Some argue that monetisation of nature can be harmful - undermining its intrinsic value beyond contributions to people, or resulting in harmful effects for people or nature. Nevertheless, economies rely on nature, and they also rely on valuations to inform policy and practice.

The Dasgupta Review advocates an "inclusive wealth" measure that includes produced capital, human capital and natural capital5. The Scottish Government employs a natural capital approach to measure the value of Scotland's natural assets (capital) that provide humans with benefits. It measures, for example, the economic value of fish stocks in Scottish seas and carbon sequestered in land plants. Services provided by Scotland’s natural capital were valued at £3.86 billion for the year 2016 - expected to be an underestimate because the value of ecosystem services like flood mitigation and tourism, and global values of services like carbon sequestration, were excluded. There are other limitations to this kind of approach. For example, if rates of fishing exceed sustainable limits, that may generate more money in the short term (as measured by natural capital accounting), but the depletion of fish stocks can threaten this resource and its ability to contribute to the economy in future.

Economic models such as the doughnut model pioneered by economist Kate Raworth - recently adopted by the city of Amsterdam - identify a "safe and just space" for human wellbeing between a social foundation where everyone has resources and the ability to live a good life, and an environmental ceiling which, when transgressed threatens Earth systems that sustain us. This model was adapted to fit the Scottish context in Oxfam's report The Scottish Doughnut: A safe and just operating space for Scotland. The doughnut model was mentioned in consultation responses to the Scottish Government's Draft Infrastructure Investment Plan 2021-22 to 2025-26, and while the final plan does not incorporate the doughnut, it does address the need to invest in "natural infrastructure" and tackle biodiversity loss.

In March 2021 the Scottish Parliament acknowledged recommendations that the concept of a Human Right to a Healthy Environment must be central to furthering human rights in Scotland. Initiatives such as Scotland's Natural Health Service (see Box 2) further recognise the diverse values of nature for people. The Scottish Government is a founding member of the Wellbeing Economy Governments group which is "founded on the recognition that ‘development’ in the 21st century entails delivering human and ecological wellbeing" and has objectives to develop policy approaches to create wellbeing economies through collaboration and ultimately address major economic, social and environmental challenges.

Box 2: Our Natural Health Service

Our Natural Health Service is a programme being led by NatureScot in collaboration with other organisations in Scotland. The programme aims to increase green health activities - such as physical exercise in the outdoors, and community growing, which are shown to improve physical and mental health - for positive health and social care outcomes.

Biodiversity loss - the nature crisis

Global trends and implications of biodiversity loss - a sixth mass extinction?

The Global Assessment Report published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) in 2019 was the most comprehensive scientific assessment of the global state of biodiversity to date. It reported that biodiversity, ecosystem functions and services are deteriorating across the globe. This is well-supported by decades of scientific research, such as findings of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, which have fuelled previous and current efforts to tackle the nature crisis. However, much biodiversity loss has occurred even in the context of such efforts.

IPBES1 reports widespread declines in global ecosystem, species and genetic diversity:

75% of the land surface and 66% of the ocean area has been significantly altered by humans while more than 85% of wetland area has been lost.

An average of around 25% of species in assessed animal and plant groups are threatened with extinction (around 1 million species in total).

Average abundance of native species in most major land-based habitats has fallen by at least 20%, mostly since 1900. Threats of extinction are most likely increasing.

Wild (non-domesticated) species genetic diversity has been declining by roughly 1% per decade since the mid-19th century. Wild mammal and amphibian genetic diversity tends to be lower in areas where human influence is greater.

Some biodiversity losses, such as species extinctions, are permanent

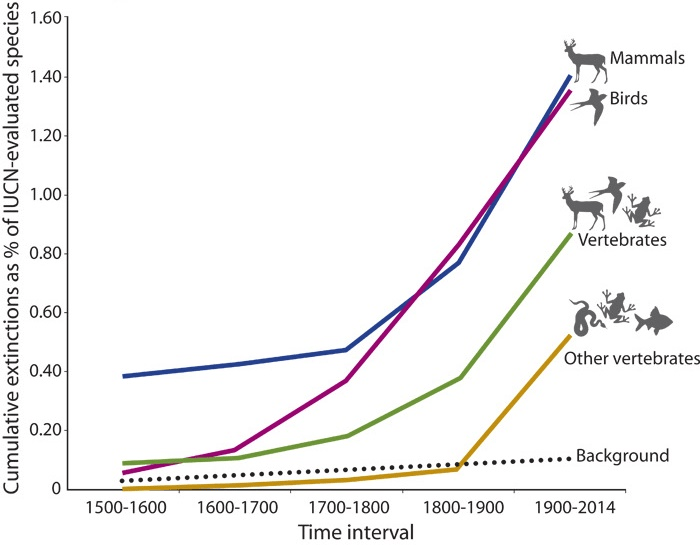

Extinctions have occurred at a relatively stable rate throughout Earth's 4.5 billion year history - known as the background extinction rate - aside from five mass extinction events caused by geological processes and changes to Earth's atmosphere and climate. Current vertebrate extinction rates are estimated to be up to 100 times greater than the background rate and scientists argue that we are in the midst of the sixth mass extinction: the first ever to be caused by humans and the first that modern humans will experience the effects of (Figure 5).2

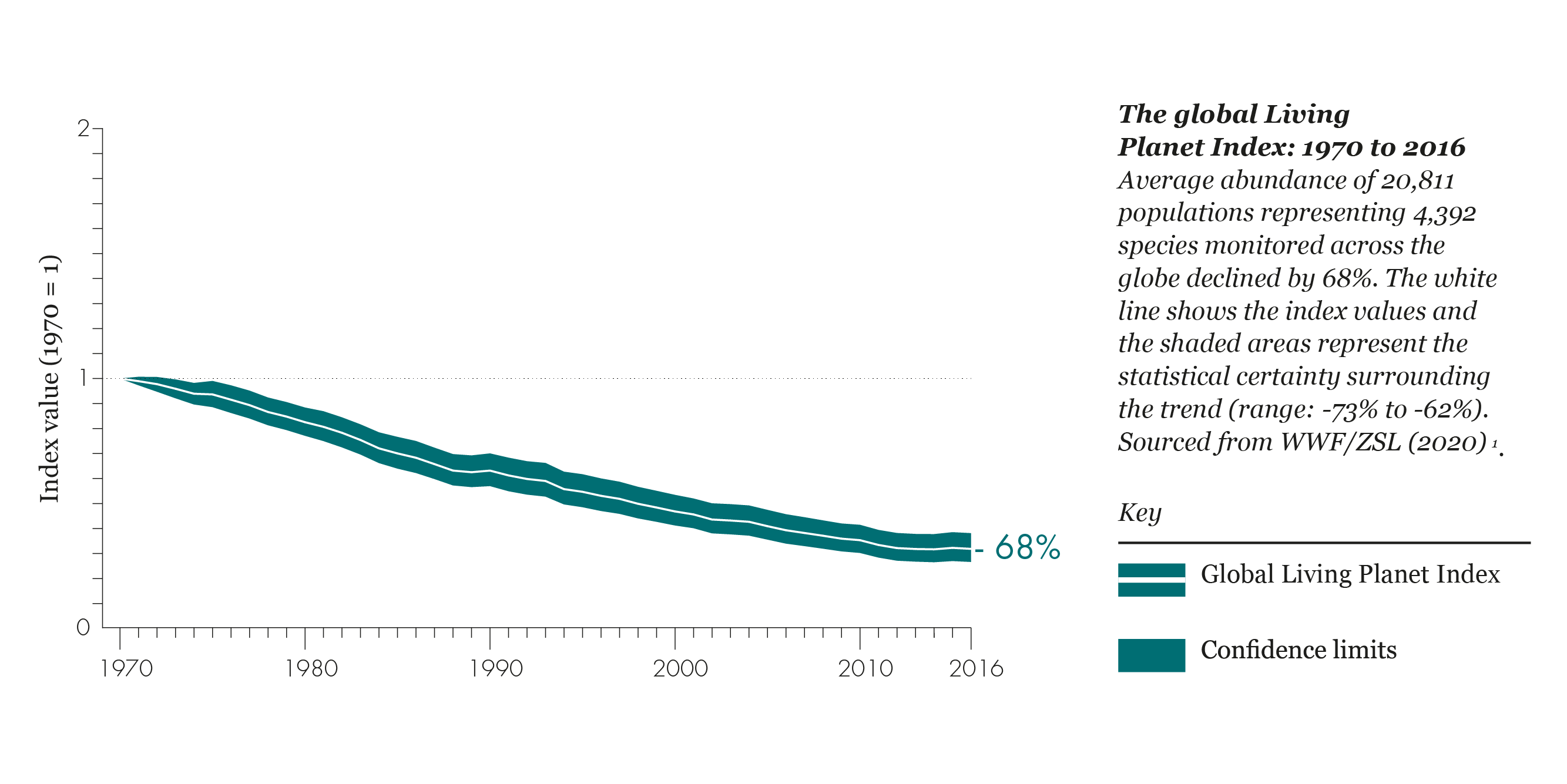

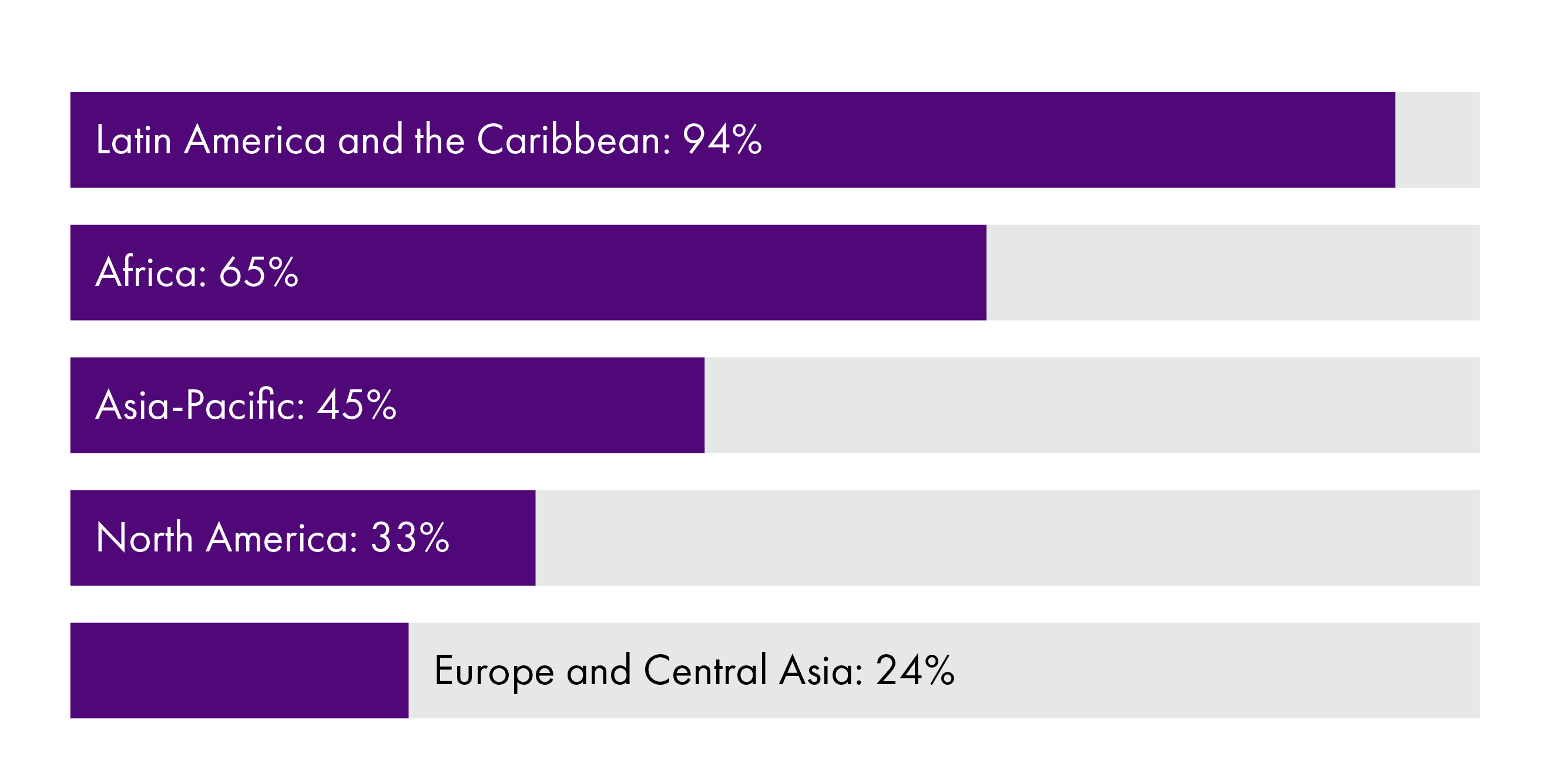

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has identified more than 37,400 animal, fungus and plant species threatened with extinction, though this is expected to be an underestimate as only a minority of species have been assessed4. The Living Planet Index finds that population sizes of mammals, birds, fish, amphibians and reptiles reduced by an average of 68% since 1970 with the greatest recent losses occurring in Latin America and the Caribbean (see Figures 6 & 7 below). Although it should be noted in the context of global comparisons of biodiversity loss, that a key driver of impacts can be unsustainable consumption and impacts relating to global supply chains (meaning the drivers of nature loss and ultimate impacts do not occur in the same place)5.

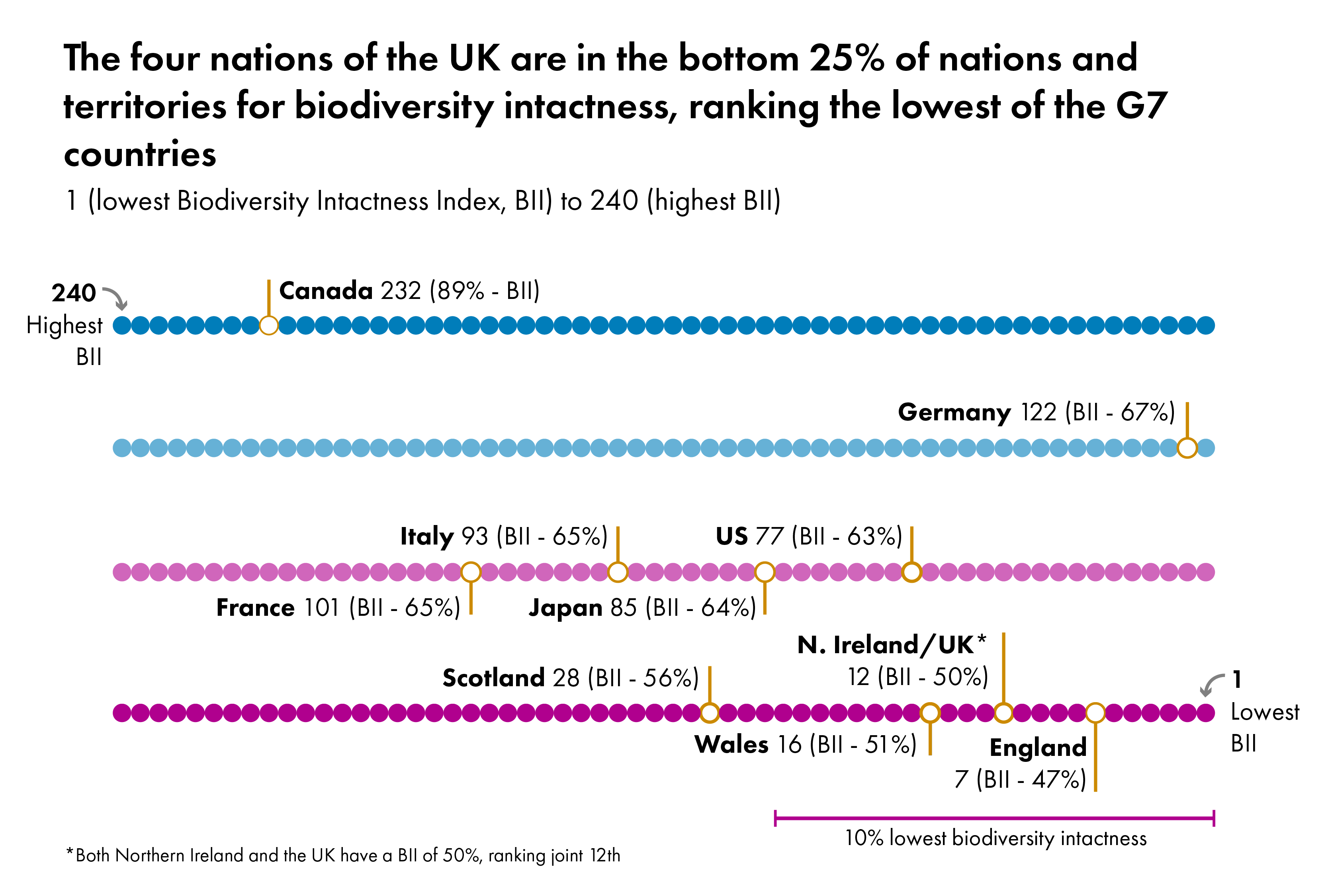

Historical losses of biodiversity (before 1970) can be captured by other measures. For example, one measure called the biodiversity intactness index indicates that across 58.1% of Earth's land area, nature's intactness has already reduced by more than is judged to be safe for humans. Historical data also show that many parts of the world where there has been less relative decline in recent decades (Figure 7) had already lost much of their nature historically - for example the UK and other parts of Europe. See more details on historical losses and the state of nature in Scotland in the following section.

Some loss of ecosystem services is permanent, and human-made replacements come with costs

For example, when wild plants closely related to crop species go extinct, this permanently reduces genetic diversity that could be used to improve agricultural productivity.1 There are human-made replacements for some ecosystem services but they usually do not provide as many benefits and are costly compared to being provided for free by nature. For example, sea walls can reduce coastal flooding where mangroves have been lost, but they are expensive and do not provide additional services like habitats, or recreation for people. Sea walls can also be detrimental in an effect known as coastal squeeze (loss of coastal habitats).

Humans have been able to enhance some ecosystem services significantly over the past 50 years while biodiversity has been in severe decline. For example more agricultural land, which now covers one third of the Earth's land area, increases the potential for food production. However, this has often been at the expense of other services, where human activities have increased some harms from nature (Box 3). Land-use change (most commonly, conversion to agricultural land) is the driver of change with the biggest relative impact on land-based environments, at the expense of forests, wetlands and grasslands and the services they provide, such as pollination and water quality regulation.1 It can also contribute to other large-scale problems such as pollution and climate change. The interdependence of different ecosystem services (for example agricultural productivity depending on pollinators, see Figure 2) means that such gains at the expense of other services are not sustainable in the long term. For example, as natural disasters such as floods and wildfires threaten global food security, converting forest to agricultural land to grow more food paradoxically further exposes crops to these disasters.10

Box 3: What happens when ecosystems don't function properly

Human interactions with the environment can disrupt ecosystem service provision or cause harm. Three examples of this are:

Peatlands:the Centre of Ecology and Hyrdrology report that degraded peatlands in Scotland emit roughly 9.6 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions per year while peatlands in a near-natural state are carbon neutral (they emit the same amount of carbon as they absorb).

Public health: the EcoHealth Alliance estimate that 31% of infectious diseases originating in wildlife since 1940, including HIV/AIDS, Ebola and Zika Virus, are linked to human encroachment on nature via land use change.

Invasive species: species that are not native to a particular area that are introduced by humans to an environment can have negative impacts andthreaten native biodiversity11 and ecosystem services.

The need for urgent and transformative action

There is no single metric that adequately measures the nature crisis or its impacts on humans, but it is clear that most measures of biodiversity and ecosystem services show that they are in decline. Biodiversity loss is widely considered to have exceeded limits considered safe for people, as changes to ecosystems are occurring to an extent never previously experienced in human history12.

The IPBES analysis which modelled different future scenarios found that the nature crisis can now only be averted "through urgent and concerted efforts fostering transformative change".

Biodiversity loss and climate change - twin crises

Links between the climate and biodiversity crises

Accelerating rates of biodiversity loss and climate change since the Industrial Revolution now exceed limits considered safe for humanity.1 The causes, consequences and responses to these twin crises are closely linked, with both terrestrial and marine habitat loss contributing to climate change, and these habitats being impacted by the changing climate.

For example, deforestation contributes to climate change by increasing carbon emissions, and biodiversity loss through the destruction of forest habitats. Both habitat loss and climate change can cause local extinctions e.g. of some butterflies in Britain.2 Scottish saltmarsh restoration has been shown to increase sequestration (capture) of blue carbon (carbon stored in marine and coastal environments) while enhancing climate change resilience and biodiversity. Renewable energy solutions to climate change such as wind turbines can have both positive and negative impacts on local wildlife.34

Integrating targets and actions

Despite the scale and interacting nature of both crises, biodiversity loss receives less media coverage than climate change.5 Scientists agree that greater awareness of the biodiversity crisis, and its links with climate change, is needed both to mobilise action and to ensure that policies are integrated to maximise benefits and ensure that neither biodiversity nor the climate are adversely affected.678 Atmospheric chemist Sir Robert Watson, who has previously chaired both the IPCC (UN's scientific panel on climate change) and IPBES, wrote in 2019:

We cannot solve the threats of human-induced climate change and loss of biodiversity in isolation. We either solve both or we solve neither.

The links between biodiversity and climate are recognised to some extent in targets and policies such as the Paris Agreement and Target 15 of the Aichi Targets, in which Parties are encouraged to conserve GHG sinks and reservoirs like trees and peatlands. Nature-based solutions (where natural processes are used to address societal challenges such as climate change) have been identified as one of the key priorities of COP26. In a Scottish example, the Climate Change Adaptation Programme 2019-2024 highlights the importance of biodiversity for climate change resilience, most explicitly in Outcome 5: "Our natural environment is valued, enjoyed, protected and enhanced and has increased resilience to climate change". The Environment Strategy for Scotland similarly recognises the linkages between the nature and climate crises.

However, internationally, biodiversity and climate targets are not considered to be sufficiently integrated to address the twin environmental crises.6 Sir Robert Watson states:

As policymakers around the world grapple with the twin threats of climate change and biodiversity loss, it is essential that they understand the linkages between the two so that their decisions and actions address both.

The world needs to recognise that loss of biodiversity and human-induced climate change are not only environmental issues, but development, economic, social, security, equity and moral issues as well. The future of humanity depends on action now. If we do not act, our children and all future generations will never forgive us.

The upcoming COP15 and COP26 meetings underpin international efforts to tackling biodiversity loss and climate change and will guide national and subnational agendas and targets.

More information on the links between these events and detail on COP26, to be held in Glasgow in November, can be found in another SPICe briefing.

The state of nature in Scotland

Recent trends

The State of Nature Scotland 2019 report found that between 1994 and 2016, 49% of Scottish species decreased and 28% increased in abundance. One in nine species are threatened with extinction from Great Britain (the scale at which IUCN extinction risk assessments are made). It was reported that some pressures on biodiversity, such as freshwater pollution, have decreased in recent decades but that the most significant human pressures continue to cause biodiversity declines.

The report highlights some conservation successes, such as the relative recovery of corncrake populations since the 1990s following severe historic declines, though this species remains at the highest level of conservation concern for UK birds. In marine environments, 12 breeding seabird species have declined in abundance by an average of 38% between 1986 and 2016. Plankton communities have changed in response to climate change which impacts fish and birds higher up the food chain. There has been recent recovery of some fish stocks following improved fisheries management, but the report notes that impacts of unsustainable fishing persist. Overall, the abundance and distribution of Scotland’s species have declined, including in the last 10 years. The report says:

There has been no let-up in the net loss of nature in Scotland

The pressures that drive biodiversity loss in Scotland are collectively continuing to have a negative impact on nature.

Historic declines

These recent declines exacerbate historic biodiversity losses in Scotland. A report from May 2021 headed by the Natural History Museum, collaborating with the RSPB, used an indicator called the biodiversity intactness index (BII) to compare biodiversity intactness in the UK with other nations and territories. BII indicates the proportion of nature that remains following human activities on land, such as converting forest to cropland, including historical losses.100% indicates that nature is fully intact.

The report finds that the UK's biodiversity intactness is 50%: it has retained half of its historic land-based biodiversity. Scotland has a BII of 56%, with slightly more biodiversity intact compared to other parts of the UK. The report ranks the countries and territories assessed from 240 (the country/territory with the most biodiversity intact) to 1 (least biodiversity intact; see Figure 8). The UK as a whole and UK territories separately are amongst the 240 countries and territories included - all ranking in the bottom 25% of nations and territories for biodiversity intactness.

Impacts on biodiversity abroad

It is important to note that the state of Scotland’s biodiversity – by any measure – does not tell a full story of Scotland’s role in biodiversity loss. For example, resources extraction for export, and associated supply chains, are a major cause of biodiversity loss in developing countries - many of which are amongst the nations experiencing the highest current rates of biodiversity loss.1 Scotland’s BII indicates biodiversity intactness on Scottish land only, not Scotland's impact on global biodiversity, including via consumption of resources extracted abroad.

An amendment to the UK Environment Bill undergoing scrutiny in the UK Parliament acknowledges this in relation to deforestation: it aims to prevent businesses of a specific size operating in the UK from using products grown on land that was deforested illegally (including abroad). As it is currently drafted, the provisions will apply in Scotland; more information on this can be found in a SPICe blog on the amendment.

The amendment responds to a 2020 report by the UK Global Resources Initiative which made recommendations about reducing impacts of UK consumption on the global environment2.However, there are impacts of UK-based consumption on biodiversity that will not be captured by this proposed law. The report emphasised that a focus on forests should only be a first step – stating that wider environmental and human rights impacts associated with commodities must also be addressed and lessons extended to other food commodities, mining and other extraction.

Another relevant example is the UK’s electricity sector, which shifts impacts on biodiversity abroad via, for example, the materials that go into building electricity infrastructure. The UK was found by a study to be one of the top five countries shifting biodiversity impacts outside its own borders due to demand for electric power.

Drivers of biodiversity loss globally and in Scotland

The IPBES Global Assessment1 identified the drivers of change in nature with the largest global impact (in descending order) as:

Changes in land and sea use;

Direct exploitation of organisms mainly via harvesting, logging, hunting and fishing;

Climate change;

Pollution;

Invasion of alien species.

A number of underlying causes related to societal values and behaviours are the indirect drivers of these five processes; for example, production and consumption patterns, human population dynamics and trends, trade, technological innovations and local to global governance.

These same drivers of biodiversity loss are occurring in Scotland - as identified by the State of Nature Scotland 2019 report (Figure 9).

Responses to biodiversity loss and the need for transformative change

Biodiversity loss, and the threat this poses to human and other life has been documented for many decades. The first major international conference to identify biodiversity conservation as a priority was the UN Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm in 1972, and there have been many local and international efforts to address biodiversity loss since. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment reported substantial and irreversible losses in biodiversity and degradation of ecosystem services. However, biodiversity loss has continued and by some measures e.g. species extinction rates1 accelerated.

The IPBES Global Assessment reports that current interventions will continue to be insufficient to curb the drivers of nature deterioration. The analysis finds that without transformative change (see Box 4), nature, ecosystem functions and nature's contributions to people will decline to 2050 and beyond, pushing the Earth further beyond thresholds of nature loss considered safe for people.2

Because biodiversity underpins human wellbeing, current trajectories of nature loss also undermine aims outlined in the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (which set out the UN Sustainable Development Goals), the global 2050 Vision for Biodiversity and the Paris Agreement on climate change.1

At the beginning of the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030) and ahead of the upcoming COP15 there are therefore widespread calls both internationally41and in Scotland to address the ecological crisis with transformative actionsthat go far beyond previous efforts. The following sections focus on approaches to addressing biodiversity loss, internationally and in Scotland, with particular reference to COP15.

Box 4: Transformative change

The IPBES Global Assessment (2019)1 found that policy responses to conserve and manage nature sustainably have had some positive impacts and contributed to meeting some international targets. However, these responses have been insufficient to stem biodiversity loss, partially because many responses have not been effectively implemented. Further, indirect drivers of biodiversity loss are embedded in social and economic systems - for example, unsustainable production and consumption and associated technological development. Climate change - a crisis also embedded in these systems - poses an ongoing threat to biodiversity.

The IPBES analysis which uses data to model different future scenarios identifies a need for transformative change - defined as "a fundamental, system-wide reorganization across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values." For example, major shifts in production and consumption patterns, e.g. of energy and food , and responses to climate change that minimise biodiversity loss, can help achieve environmental and social needs. This is likely to involve mainstreaming biodiversity across a range of policy areas. The IPBES report says:

Acting immediately and simultaneously on the multiple indirect and direct drivers has the potential to slow, halt and even reverse some aspects of biodiversity and ecosystem loss.

Nature can be conserved, restored and used sustainably while simultaneously meeting other global societal goals through urgent and concerted efforts fostering transformative change.

The Convention on Biological Diversity and forthcoming COP15

The United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) is the key international treaty on biodiversity. Since its initiation, there have been fourteen meetings of the Conference of the Parties (COP), the decision making body for the Convention. COP15 is due to begin in October 2021 - it was postponed from 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and will now take place in two parts. The first will take place online from 11-15 October 2021, and the second part is due to take place face-to-face in Kunming, China, from 25 April-8 May.

Article 1 of the Convention outlines three main objectives:

The conservation of biological diversity,

The sustainable use of its components, and

The fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources.

The Convention adopts a precautionary approach, stating in the preamble:

Where there is a threat of significant reduction or loss of biological diversity, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to avoid or minimize such a threat.

Taking a precautionary approach to the development of policy in Scotland, from an environmental perspective, is also rooted in domestic law via the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2021.

Adoption of the Convention

The CBD recalls its history back to 1988 when, in response to evidence of biodiversity loss, the UN Environment Programme hosted the First sessions of Ad Hoc Working Group of Experts on Biological Diversity. Over the next few years, groups of experts worked together to establish the scientific and legal basis for an international convention. By 1992, the text of the Convention had been agreed and was open for signatures at the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development held in Rio de Janeiro - the “Earth Summit”. The CBD entered into force in 1993 with 168 signatories.1 There are now 196 Parties, including the UK, who are legally bound by the Convention. Notably, the USA is a signatory but not a Party to the CBD; along with the Vatican City it is one of two countries not legally bound by it. There are two supplementary agreements to the CBD (see Box 5).

Box 5: Supplementary agreements to the Convention on Biological Diversity

The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the Convention on Biological Diversity, in force since 2003, aims to ensure the safe handling, transport and use of living modified organisms resulting from biotechnology that may have adverse effects on biological diversity, taking also into account risks to human health.

The Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity, in force since 2014, aims at sharing benefits gained from the use of genetic resources in a fair, equitable way.

Implementing the CBD

National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAP), such as the Scottish Government's 2020 Challenge for Scotland's Biodiversity are the main means of implementing the CBD at national and subnational levels. Implementation of the Convention is also monitored through National Reports like Scotland's Biodiversity Progress to 2020 Aichi Targets. Summaries of the global status of biodiversity and analysis of progress on the aims of the Convention are published in Global Biodiversity Outlook reports.

Scotland and COP15

The Scottish Government is a "subnational" government for the purposes of the CBD. This means that it is not a Party to the Convention in it's own right - the UK Government represents the four UK nations in international agreements. However the Scottish Government does have responsibility for implementation of international agreements like the CBD in Scotland. Along with other subnational governments among the CBD parties, the Scottish Government's Edinburgh Declaration on post-2020 global biodiversity framework - with 127 subnational government, city and local authority signatories as of May 2021 - outlines hopes for COP15, the new global biodiversity framework, goals and targets for the next ten years.

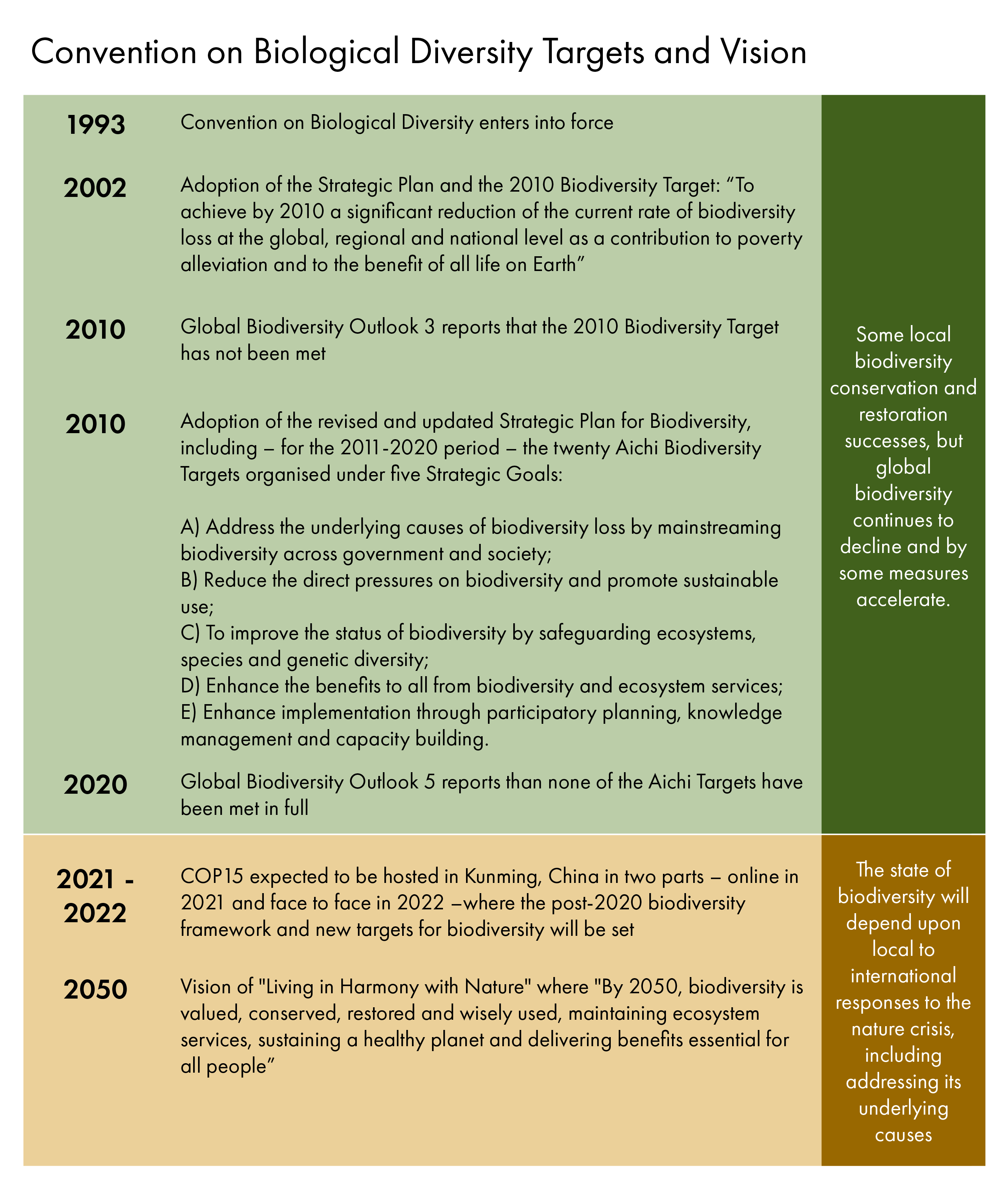

Targets for halting and reversing biodiversity loss - mostly missed

The CBD framework is responsible for setting global targets to halt and reverse biodiversity loss. The two major international biodiversity frameworks and sets of targets that have emerged from the CBD thus far - the 2010 Biodiversity Target and the 2020 Aichi Targets - have largely been missed, and have failed to stem biodiversity loss.

The 2010 Biodiversity Target

In 2002, the parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) adopted the 2010 Biodiversity Target - to achieve by 2010 a significant reduction of the current rate of biodiversity loss at the global, regional and national level. This became one of the targets under the UN Millennium Development Goals. The 2010 Biodiversity Target had 21 subsidiary targets under 11 broad goals.

In Global Biodiversity Outlook 31 published in 2010, the CBD reported that the target had not been met. There had been some progress on some of the subsidiary targets, but none were fully met and several showed no progress (see Annex 1). Multiple indications of continued biodiversity decline were reported.

Global Biodiversity Outlook 3 also reported learnings from the failures of the 2010 Biodiversity Target, and recommendations for a future strategy to reduce biodiversity loss including setting further time-bound targets. Some of these recommendations included:

Mainstreaming nature so that activities of environmental departments and agencies are no longer undermined by decisions from other ministries that have negative impacts on biodiversity.

Proofing of policies for their impact on biodiversity and ecosystem services, while looking for opportunities for co-benefits with climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Improved systems for fair and equitable sharing of benefits from genetic resources.

Tackling indirect drivers of biodiversity loss, including consumption and lifestyle choices, for example by removing subsidies that incentivise biodiversity loss.

Global Biodiversity Outlook 3 stated:

One of the main reasons for the failure to meet the 2010 Biodiversity Target at the global level is that actions tended to focus on measures that mainly responded to changes in the state of biodiversity, such as protected areas and programmes targeted at particular species, or which focused on the direct pressures of biodiversity loss, such as pollution control measures.

For the most part, the underlying causes of biodiversity [decline and loss] have not been addressed in a meaningful manner; nor have actions been directed [towards] ensuring we continue to receive the benefits from ecosystem services over the long term. Moreover, actions have rarely matched the scale or the magnitude of the challenges they were attempting to address.1

The UN Decade on Biodiversity and 2020 Aichi Targets

Following the failure of the 2010 Biodiversity Target, a revised and updated Strategic Plan (international framework) for Biodiversity 2011-2020 was agreed at COP10 in 2010. The vision for the new Plan was "Living in Harmony with Nature" where "By 2050, biodiversity is valued, conserved, restored and wisely used, maintaining ecosystem services, sustaining a healthy planet and delivering benefits essential for all people."

The updated Plan included twenty Aichi Biodiversity Targets (see Box 6) to be met by 2020.

Box 6: The Twenty Aichi Targets

The targets below are abridged - full targets and strategic goals are in Annex 2 of this briefing. All Aichi Targets were to be fulfilled by 2020 apart from targets 10, 16 and 17 which had a deadline of 2015.

Raise awareness of the values of biodiversity, how to conserve and use it sustainably.

Integrate biodiversity values into development, poverty reduction, planning, national accounting and reporting.

Eliminate incentives, including subsidies, that are harmful to biodiversity and apply positive incentives for conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.

Keep use of natural resources by governments, business and stakeholders well within safe ecological limits.

Reduce the rate of loss of all natural habitats by at least half.

Manage marine life sustainably, including ensuring the impacts of fisheries on stocks, species and ecosystems are within safe ecological limits.

Sustainable agriculture, aquaculture and forestry, ensuring conservation of biodiversity.

Reduce pollution to safe levels for ecosystem functions and biodiversity.

Control priority invasive alien species and prevent their introduction and establishment.

Minimize climate change and ocean acidification effects on ecosystems like coral reefs.

Protect at least 17% of terrestrial and inland water, and 10% of coastal and marine areas.

Prevent the extinction of known threatened species.

Maintain the genetic diversity of socio-economically and culturally valuable species.

Restore and safeguard ecosystem services.

Enhance ecosystem resilience and natural carbon stocks, including restoration of at least 15% of degraded ecosystems.

Ensure the Nagoya Protocol (Box 5) is operational, consistent with national legislation.

Ensure each Party has an effective, participatory and updated national biodiversity strategy and action plan.

Integrate indigenous and local communities, their knowledge, innovations and practice.

Improve, share and apply knowledge, science and technologies relating to biodiversity.

Mobilize financial resources for effective implementation of the 2011-2020 targets.

Parties agreed that by 2015, the international Strategic Plan would be translated into updated National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs). The 2020 Challenge for Scotland's Biodiversity is an example of an NBSAP. Each of the four countries of the UK had their own strategy for 2020 which together formed the UK NBSAP.

The UN Decade on Biodiversity (2011-2020) aimed to assist the implementation of the CBD's 2011-2020 Strategic Plan through activities such as encouraging governments, organisations, communities and individuals to take action on biodiversity loss.

Globally: most Aichi Targets were missed

In Global Biodiversity Outlook 5 published in 2020, the CBD assessed progress towards achieving the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. It reported that none of the Aichi Targets were met in full. Six targets were partially achieved (Targets 9, 11, 16, 17, 19 and 20; see further details in Annex 2). National targets were noted to be generally poorly aligned with the Aichi Targets, with gaps in the level of ambition and actions to address the nature crisis at the national and subnational level. Globally, it is reported that:

Indicators of responses to the biodiversity crisis in terms of policies and actions (such as updates to NBSAPs and incorporating biodiversity values into national accounting systems) show significantly positive trends i.e. countries now have more biodiversity policies and accounting systems in place.

However, indicators relating to the drivers of biodiversity loss, and to the actual state of biodiversity mostly show significantly worsening trends i.e. those policies are not working, or not working well enough to slow biodiversity loss.

In the UK and Scotland: most Aichi Targets were missed

Interim reports (2016, 2017 and 2019) were published on Scotland’s progress on the Aichi targets as part of the UK's NBSAP and reporting and a final report was published in 2021. This showed that Scotland met nine of the 20 targets but failed to meet the majority of targets. The report stressed that there is still pressure on biodiversity, even where targets are currently being met.

A UK-wide final assessment was submitted to the CBD in 2019 by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC). The report showed that in the UK five Aichi targets - on mainstreaming (2), protected areas (11), implementation of the Nagoya Protocol (16), National biodiversity strategy (17), and mobilisation of information and research (19) - were on track to be achieved. In line with global trends, these are mainly targets related to policies rather than the drivers of biodiversity loss and the actual state of biodiversity. Progress was being made for 14 of the targets, but they would be missed.

A separate analysis by the RSPB challenged some of the findings of the UK's self-assessment. Its analysis covered 13 of the 20 targets, and their assessment disagreed with the JNCC on eight of these including seven targets which the RSPB assessed as "no progress or moving away from the target" where the JNCC reported progress, meeting or exceeding the target. The RSPB highlights lack of progress on protected areas (11), species conservation (12) and funding for solutions (20) as particularly significant for nature.1 The RSPB declared the Decade on Biodiversity as a "lost decade for nature" and called for immediate action. Comparison of the JNCC and RSPB's findings are given in Annex 2.

The Secretariat of the CBD and others have published reports analysing why the world has not met biodiversity targets. The latest CBD reports agree with IPBES research findings that urgent, transformative change is required. Some of these ideas are explored in the following sections.

Learnings from failed targets - the need to scale-up and integrate nature recovery

Since the CBD came into force in 1993, its core aims have not been achieved (see Figure 10 below). However, evidence shows that well-planned and implemented conservation actions can have positive effects for biodiversity on land and in the sea.12

Repeated failures

In its Global Biodiversity Outlook (GBO) reports, the CBD Secretariat report learnings and make recommendations for how efforts must proceed. Recommendations from GBO3 in 2010 helped to formulate the Aichi Targets. For example the recommendation in GBO3 to have a goal for mainstreaming nature became Strategic Goal A of the Aichi Targets.

However, the main pressures on biodiversity as identified in GBO3 - land and sea use change, overexploitation, climate change, pollution and invasive alien species - remain the main pressures cited in GBO5 in 2020 (the final report on the Aichi Targets). The need to address the indirect drivers of biodiversity loss, for example unsustainable patterns of production and consumption, was also reported in both GBO3 and GBO5, suggesting that many of these problems remain.

It's not too late to halt the nature crisis - but transformative change is required

The most recent GBO5 reports that it is not too late to slow, halt and reverse the nature crisis3. However, it reiterates findings from IPBES that transformative change is required. Business as usual will result in intensified pressures on nature, with the continued decline of biodiversity and the benefits it provides people. GBO5 identifies that a"portfolio of actions" is required:

Scaling up conservation and restoration using locally-relevant approaches.

Keeping climate change well below 2 degrees C and close to 1.5 degrees C above pre-industrial levels.

Effective action on the remaining pressures on biodiversity including invasive alien species, pollution and exploitation of nature especially in marine and freshwater ecosystems.

Transformation in the production of goods and services, especially food.

Limiting consumption including demand for increased food production by adopting healthier diets and reducing food waste, as well as other goods and services from forestry, energy and provision of fresh water.3

GBO5 notes that action in all of these areas is necessary to tackle the nature crisis, and action in one area will often help remove barriers to change in another. GBO53 gives detailed examples of eight "transitions" that will be required - related to land and forests, sustainable agriculture, cities and infrastructure, sustainable freshwater, climate action, health, sustainable food, fisheries and oceans. It also explores these in relation to "levers" (Box 7) that may be applied by leaders to achieve transformative change.6

Box 7: Levers for transformative change

The IBPES Assessment6 identified five levers - key interventions - which can generate transformative change to tackle the nature crisis. These levers address underlying drivers of biodiversity loss (emphasis added):

Developing incentives and widespread capacity for environmental responsibility and eliminating perverse incentives (incentives that result in harming nature);

Reforming sectoral and segmented decision-making to promote integration across sectors and jurisdictions;

Taking pre-emptive and precautionary actions in regulatory and management institutions and businesses to avoid, mitigate and remedy the deterioration of nature, and monitoring their outcomes;

Managing for resilient social and ecological systems in the face of uncertainty and complexity, to deliver decisions that are robust in a wide range of scenarios;

Strengthening environmental laws and policies and their implementation.

In 2010, Global Outlook 38 stated (emphasis added):

Many actions in support of biodiversity have had significant and measurable results in particular areas and amongst targeted species and ecosystems. This suggests that with adequate resources and political will, the tools exist for loss of biodiversity to be reduced at wider scales[...]

However, action to implement the Convention on Biological Diversity has not been taken on a sufficient scale to address the pressures on biodiversity in most places. There has been insufficient integration of biodiversity issues into broader policies, strategies and programmes, and the underlying drivers of biodiversity loss have not been addressed significantly.

Ten years later, Global Outlook 53 reported (emphasis added):

Pathways to a sustainable future rely on recognizing that bold, interdependent actions are needed across a number of fronts, each of which is necessary and none of which is sufficient on its own. This mix of actions includes greatly stepping up efforts to conserve and restore biodiversity, addressing climate change in ways that limit global temperature rise without imposing unintended additional pressures on biodiversity, and transforming the way in which we produce, consume and trade goods and services, most particularly food, that rely on and have an impact on biodiversity.

COP15 and the post-2020 framework

The 2050 Vision for Biodiversity of “Living in harmony with nature” remains a core aim of the CBD. The challenge for the CBD and its 196 Parties now is to set and meet interim targets that will enable this to be achieved. Meeting these targets will also be necessary if other international commitments such as the Paris Agreement on climate change are to be met.

Against the backdrop of previous failed targets and the accelerating nature crisis, the post-2020 biodiversity framework and a new set of global targets will be set at COP15 (Box 8), due to be held in Kunming, China, in two parts, at an online conference in October 2021, and a face-to-face conference in April-May 2022. COP15 is being held within a few months of the UN Climate Change Conference COP26 to be held in Glasgow, the UN Convention to Combat Desertification COP15, the start of the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, and as many nations seek to deliver a green recovery from COVID-19.

Box 8: CBD Conferences of the Parties; at a glance

First meeting: Nassau, Bahamas, 28 November - 9 December 1994

Meeting frequency: Annually until 1996, now every two years

Number of Parties: 196

Primary source of scientific evidence: the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)

Major outputs:2010 Biodiversity Target, Aichi Biodiversity Targets (2011)

Next meeting: COP15 in Kunming, China, October 2021 and April-May 2022.

What will happen at COP15?

Ahead of COP15 there are meetings of different groups of Parties to the CBD. An Open-ended Working Group on the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework have met to draft the text of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. Developed over two years, a First Draft of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework was published on 5 July 20211.

The Framework comprises 21 targets and 10 ‘milestones’ proposed for 2030, en route to ‘living in harmony with nature’ by 2050. Key targets include:

Ensure that at least 30 per cent globally of land areas and of sea areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and its contributions to people, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.

Prevent or reduce the rate of introduction and establishment of invasive alien species by 50%, and control or eradicate such species to eliminate or reduce their impacts.

Reduce nutrients lost to the environment by at least half, pesticides by at least two thirds, and eliminate discharge of plastic waste.

Use ecosystem-based approaches to contribute to mitigation and adaptation to climate change, contributing at least 10 GtCO2e per year to mitigation; and ensure that all mitigation and adaptation efforts avoid negative impacts on biodiversity.

Redirect, repurpose, reform or eliminate incentives harmful for biodiversity in a just and equitable way, reducing them by at least $500 billion per year.

Increase financial resources from all sources to at least US$ 200 billion per year, including new, additional and effective financial resources, increasing by at least US$ 10 billion per year international financial flows to developing countries, leveraging private finance, and increasing domestic resource mobilization, taking into account national biodiversity finance planning.

At COP15, attendees will share reports from recent regional and other CBD meetings, review implementation of the Aichi Targets, and seek to agree the post-2020 global biodiversity framework including mechanisms for its implementation. An agenda is available on the CBD website.

How can COP15 stem biodiversity loss?

Setting appropriate targets (Box 9) and measuring their progress (Box 10) is seen as key to the success of the COP and action on biodiversity in subsequent years.

Box 9: Getting COP15 targets right - hopes of scientists and NGOs

The failure of the world to a) meet any international biodiversity targets in full, and b) adequately protect and restore biodiversity has resulted in increased pressure to get biodiversity policy right. An editorial on COP15 in the scientific publication Nature in 2020 notes that conservation groups back more stringent and more measurable targets.

Looking across a number of publications from scientists and environmental organisations, hopes for COP15 include:

SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Time-bound) targets. Research found that more progress was made on Aichi targets which met SMART criteria2 - however, many Aichi targets did not meet these criteria. It is expected that SMART targets post-2020 can be better translated into actionable policies and successful implementation. However, there is still a danger that targets will be SMART without being ambitious enough to address the nature crisis.

In particular, a SMART goal for species which does not accept extinctions or exacerbate extinction risk is considered to be crucial to halting biodiversity loss. Scientists have suggested a goal worded as such: Human-induced species extinctions are halted from 2020 onwards, the overall risk of species extinctions is reduced by 20% by 2030 and is zero by 2050, and the population abundance of native species is increased on average by 20% by 2030 and returns to 1970 values by 2050.3 The Draft Agreement currently includes the less ambitious milestone "The increase in the extinction rate is halted or reversed, and the extinction risk is reduced by at least 10 per cent, with a decrease in the proportion of species that are threatened, and the abundance and distribution of populations of species is enhanced or at least maintained".

A SMART target for ecosystems4 – recognising interdependent ecosystem processes.

Effective environmental accounting – such as the recommendations and mechanisms provided by the UN System of Environmental Economic Accounting.

Effective indicators to measure progress on targets (Box 10). However, targets should not be constrained by lack of existing indicators and must remain ambitious – because usually, appropriate indicators can be developed, or in tandem with target development.

Aratchet mechanism – similar to mechanisms for achieving climate change goals – which ensures that national strategies and targets are revised and updated to become progressively more ambitious over time.

Coherence and complementarity with other international frameworks including the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. It has been suggested that the new CBD framework could fill gaps in other international goals and enhance synergies with other conventions. For example, climate change goals in the UNFCCC are more likely to be met if nature-based solutions to climate change are embraced.5

Listening to all voices including marginalised groups – “indigenous peoples and local communities, regional and city governments, the private sector, NGOs, women, youth and society at large must be not only invited to the debate but the framework should also incentivise their explicit contributions towards the global goals.”

Critically, lack of adequate implementation of targets for nature is widely considered to be a major reason that the nature crisis has continued and, by some measures, worsened in recent decades. Implementation support mechanisms are addressed in the first draft of the framework and researchers note that these must be translated into adequately funded action at national and subnational levels.6

Box 10: Indicators for the targets

The Biodiversity Indicators Partnership supports the development and delivery of biodiversity indicators - measures of different aspects of biodiversity - for the CBD and other organisations, conventions and governments. They developed indicators to measure progress on the Aichi Targets and are developing indicators for the post-2020 framework based on previous learnings. They state that successful indicators should be:

Scientifically valid;

Responsive to change;

Easy to understand;

Championed by those responsible for their production and communication;

Used. Indicators should be used for "measuring progress, early-warning of problems, understanding an issue, reporting, awareness-raising, etc."

NatureScot lists indicators used to measure biodiversity in Scotland on its website such as a 'genetic scorecard' - an approach for assessing the genetic diversity of wild species developed by researchers in Scotland.

Other international commitments

International commitments, conventions or treaties related to biodiversity are referred to as Multilateral Environmental Agreements. Scotland, alongside the other nations of the UK, is committed to several such agreements in addition to the CBD, including:

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and its Paris Agreement with the aim of keeping climate warming well below 2°C, with a target of 1.5°C, above pre-industrial levels.

The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) aims for sustainable land management in drylands - arid and dry regions of the world - for the benefit of nature and the people living there. The CBD, UNFCCC and UNCCD are the three Rio Conventions that were agreed at the 1992 Earth Summit and all are due to have meetings in 2021/22. The next Conference of the Parties for the UNCCD is expected in 2022.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) to ensure that international trade in wild animals and plants does not threaten the survival of the species.

The Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) for internationally coordinated conservation and sustainable use of migratory animals and their habitats.

The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA) which focuses on increasing fair sharing and access to plant genetic material useful for crops.

The Ramsar Convention on the conservation and wise use of wetlands - where wetlands of International Importance are designated as Ramsar Sites.

The Bern Convention which aims to conserve wild animals and plants in their natural habitats, in Europe and some African countries.

The International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) aims to protect the world's plants from pests and diseases, and promote safe trade.

The World Heritage Convention to protect natural and cultural heritage, including designating World Heritage Sites such as St Kilda.

The OSPAR Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic to prevent marine pollution and other human activities that can adversely affect the marine environment of the North-East Atlantic

The UN Environment Programme lists conventions and other entities it administers or supports.

Many of these agreements are important mechanisms for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as part of Agenda 2030.1

Leaders' Pledge for Nature

At the UN Summit on Biodiversity in September 2020 - with the theme of "Urgent action on biodiversity for sustainable development" - political leaders representing 84 countries including the UK endorsed the Leaders' Pledge for Nature which commits to reversing biodiversity loss by 2030. At the summit, opportunities for a just and green economic recovery after COVID-19 were discussed. = Leaders pledged to review progress and reaffirm their commitments at future international events. In June 2021, leaders at the G7 Summit built on this commitment in the 2030 Nature Compact:

We, the G7 Leaders, commit to the global mission to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. We will act now, building on the G7 Metz Charter on Biodiversity and the Leaders’ Pledge for Nature, championing their delivery, to help set the necessary trajectory for nature to 2030.

Scottish biodiversity policy

Reflecting the global picture, biodiversity loss has continued in Scotland during the development and implementation of new biodiversity policies. For example, though Scotland's Biodiversity Strategy was updated in response to the Aichi targets, NatureScot reported that Scotland met just nine of the twenty Aichi targets.

Addressing the nature crisis in Scotland therefore requires greater efforts, and it is agreed internationally that reversing biodiversity loss requires integrating actions on biodiversity across a range of policy areas1.

The Scottish Government website gives up to date information about biodiversity policy including relevant strategies, legislation and international commitments such as the CBD.

The Scottish Government has committed that a new overarching biodiversity strategy will be published within 12 months of COP15.

Biodiversity aims and strategies

Biodiversity strategies

NatureScot, Scotland's nature agency (formerly Scottish Natural Heritage), and the Scottish Government co-lead the Scottish Biodiversity Programme which oversees activity on biodiversity including policy, reporting, international work, evidence, communications and public engagement, mainstreaming and funding. This work is supported by SEFARI which delivers the Scottish Government-funded Strategic Research Programme 2016-2021 on environment, food, agriculture, land and communities. An updated strategy for environment, natural resources and agriculture research for 2021-2027 was published in March 2021.

Scotland's Biodiversity - It's In Your Hands was Scotland's first biodiversity strategy to 2030, published in 2004. This has since been supplemented by the 2020 Challenge for Scotland's Biodiversity - Scotland's response to the Aichi Targets and the EU's European Biodiversity Strategy for 2020 (2011) - and together these two documents are Scotland's current biodiversity strategy. The strategy emphasises an ecosystem approach and the benefits of ecosystem services to people. This was supported by Scotland's Biodiversity: A Route Map To 2020 which outlined priority work needed to meet the Aichi Targets.

The Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004 requires reporting on progress on any biodiversity strategy every three years. The Scottish Biodiversity Strategy (SBS) Coordination Group oversees reporting and delivery.

Scotland has long been involved in international efforts to protect and restore biodiversity, for example recently via the Edinburgh Process and its resulting Edinburgh Declaration on the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. This, as well as COP15 outcomes, will guide the Scottish Government's post-2020 biodiversity strategy. The Edinburgh Declaration, published in August 2020, outlines hopes for the post-2020 framework. In December 2020 the Scottish Government published a Statement of Intent on Scotland's post-2020 biodiversity strategy which sets out the intention to publish a new biodiversity strategy within 12 months of COP15. Until publication of the new strategy, the 2020 Challenges and Route Map continue to apply.

The Environment Strategy

The Scottish Government has published a wider Environment Strategy in addition to its biodiversity strategy. The Environment Strategy for Scotland's overarching vision is:

One Earth. One home. One shared future. By 2045: By restoring nature and ending Scotland’s contribution to climate change, our country is transformed for the better - helping to secure the wellbeing of our people and planet for generations to come.

The strategy takes into account interactions between social and environmental goals, and the necessity to deliver positive outcomes for nature across a range of connected policy areas. For example, one Strategy outcome is “Scotland’s nature is protected and restored with flourishing biodiversity and clean and healthy air, water, seas and soils”.

Other priorities for Scotland

Scotland's National Performance Framework includes an aim for the Environment - whereby citizens value, enjoy, protect and enhance the environment - as one of the National Outcomes that describe the kind of Scotland the framework aims to create.

In her Priorities of Government Statement in 2021, the First Minister announced the aim to “protect and enhance our natural habitats”, increase woodland creation by 50% and invest £250 million in peatland restoration this decade. 22.7% of the Scottish land area is currently protected and the Government has committed to increasing protection on land to at least 30% by 2030 (consistent with the target expected to be introduced in COP15). Effective management of these areas will be key to determining their success (see Box 11).

Box 11: An effective 30 by 30 target - the need to close the implementation gap

Protected areas - sites designated and protected or managed for their nature value- have long been a major feature of international conservation strategies. Gaps in implementation, for example when protected sites are poorly managed or when the most important sites for biodiversity are not protected, can result in policy being ineffective,1 which may partly explain why biodiversity loss has continued despite decades of policy for biodiversity conservation.

At the One Planet Summit held in January 2021, the UK along with more than 50 other countries committed to protecting at least 30% of both land and sea by 2030 to halt biodiversity loss. This 30% target is also in the current first draft of the CBD's post-2020 framework on biodiversity:

"Ensure that at least 30 per cent globally of land areas and of sea areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and its contributions to people, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes."

In Scotland, currently 37% of the marine environment is designated as protected. However, designating a Marine Protected Area does not necessarily mean that activities within it, such as fishing, aquaculture or infrastructure development, are actively managed or limited. Marine biodiversity therefore can remain threatened. In the 2021-22 Programme for Government, the Scottish Government commits to "a step change in marine protection", and to:

deliver fisheries management measures for existing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) where these are not already in place by March 2024 at the latest;

add to the existing MPA network by designating a suite of Highly Protected Marine Areas (HPMAs) covering at least 10% of our seas, providing additional environmental protection over and above the existing MPA network.

It was also recently announced that in England there will be a trial of Highly Protected Marine Areas, which will "prohibit extractive, destructive and depositional uses and allow only non-damaging levels of other activities".

The remaining 70% of land and sea- also home to important biodiversity and ecosystems that humans rely on - relies on effective consideration of biodiversity within sectoral policies. Mainstreaming biodiversity across a range of policy areas - including effective implementation in these areas - provides opportunities for this (see further below).

NGO priorities

Environmental organisations have also highlighted priorities for nature in Scotland. For example, the WWF, RSPB Scotland and Scottish Wildlife Trust's Nature Recovery Plan published in 2020 outlines actions for delivering transformative change. Twelve priorities are identified in Scottish Environment LINK's 2021 Manifesto for Nature and Climate. Key priorities identified across these reports include:

Sufficient funding to tackle the nature and climate emergencies.

Legally binding nature recovery targets.

Policies and legislation to decarbonise and build a Circular Economy.

Protection of marine ecosystems with an ocean recovery plan, legislation for sustainable low-impact fishing and a greater proportion of strictly protected Marine Protected Areas.

Protection of freshwater habitats and species.

Protection of peatlands, for example by ending burning, commercial extraction and sale of peat for horticulture.

Expansion of native woodlands including planting native species, and better management of existing woodlands.

Reducing key threats to nature for example by halting the introduction of invasive non-native species, ending wildlife crime, reducing nitrogen pollution, reducing deer populations and maintaining them at a sustainable level.

Rewards for nature- and climate-friendly farming through renewed policy.

Effective sustainable land management delivered via e.g. Regional Land Use Frameworks.

Ensuring all new development is net positive for nature, and embed a Nature Network for Scotland in the National Planning Framework 4; this and other policy areas are further explored later in this briefing.

In relation to the call for legally binding targets, the 2021-22 Programme for Government sets out a Scottish Government commitment tointroduce a Natural Environment Bill in Year 3 of this Parliament, to "put in place key legislative changes to restore and protect nature, including, but not restricted to, targets for nature restoration that cover land and sea, and an effective, statutory, target‑setting monitoring, enforcing and reporting framework". The PfG states:

Those targets will be based on an overarching goal of preventing any further extinctions of wildlife and halting declines by 2030, and making significant progress in restoring Scotland’s natural environment by 2045, and will include outcome targets that accommodate species abundance, distribution and extinction risk, and habitat quality and extent.

Similar needs across the UK - and the necessity of effective delivery mechanisms

Many of the above recommendations from Scottish-based organisations overlap with recommendations for other parts of the UK. For example, environmental organisations in Northern Ireland have called for nature networks and legally binding biodiversity targets.

In June 2021, the UK Parliament Environmental Audit Select Committee reported on an inquiry into the UK Government's progress in achieving biodiversity targets, the state of biodiversity in the UK, and detailing many recommendations for how the UK can best protect and enhance biodiversity. Recommendations include the need for legally binding targets for nature, adopting an inclusive wealth approach (or another approach to measuring economic health that doesn't focus solely on GDP) and better management of protected areas, noting "simply designating areas as protected is not enough" (see also Box 11). Following the end of the inquiry and the publication of the Committee report, Chair of the Committee Philip Dunne MPstated:

Although there are countless government policies and targets to 'leave the environment in a better state than we found it', too often they are grandiose statements lacking teeth and devoid of effective delivery mechanisms [...]

We have no doubt that the ambition is there, but a poorly-mixed cocktail of ambitious targets, superficial strategies, funding cuts and lack of expertise is making any tangible progress incredibly challenging.2

On June 30th 2021, the Welsh Senedd declared a "nature emergency", which was noted as being inextricably linked to the climate emergency. The Senedd also called on the Welsh Government to introduce statutory targets to reverse biodiversity loss, and legislate to establish an independent environmental governance body for Wales.

Environmental laws after EU exit

The Scottish Government website lists some of the legislation relevant to biodiversity conservation and restoration; for example, the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004 which makes provisions related to biodiversity conservation, the conservation and enhancement of Scotland’s natural features, and the protection of certain species. It mandates a duty to further the conservation of biodiversity for every public body and office-holder. The NatureScot website also details some of the legislation particularly relevant to protecting wild species.

Keeping pace with the EU?

Scotland was previously bound by EU environmental regulations, but since exiting the EU is no longer required to align with EU legislation. A snapshot of EU standards and regulations has been retained in domestic legislation as a new category of law called 'retained law'.

There have been concerns raised that as a result of no longer being required to adhere to EU regulations, standards for protecting and restoring nature will slip across the UK.

Following a Scottish Government policy commitment to continue to maintain standards and protection for the environment and align with the EU where appropriate1, the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2021 was enacted to provide Scottish Ministers with a "keeping pace power". This allows (but does not require) Scottish Ministers to align Scottish law with EU law in devolved areas using secondary legislation. The Act also created a new body, Environmental Standards Scotland, to to ensure the effectiveness of environmental law, and prevent enforcement gaps arising from the UK leaving the EU.

Some of the complexities around environmental governance in Scotland after EU exit were explored in a previous SPICe briefing.

In The Environment Strategy for Scotland the Scottish Government states:

We will seek to maintain or exceed EU environmental standards. We will ensure that international environmental principles continue to sit at the heart of our approach to environmental law and policy. And we will ensure that we have robust governance arrangements to implement and enforce those laws.

These commitments are likely to be relevant to biodiversity in relation to whether and how the Scottish Government chooses to align with any developing EU standards or targets on biodiversity and nature.

One key area in relation to this is the question of the introduction of legally binding targets. The introduction of legally binding targets for nature is proposed in the EU biodiversity strategy for 2030 (Box 12).

As stated above, the 2021-22 Programme for Government sets out a Scottish Government commitment to introduce a Natural Environment Bill in Year 3 of this Parliament, to "put in place key legislative changes to restore and protect nature, including, but not restricted to, targets for nature restoration that cover land and sea, and an effective, statutory, target‑setting monitoring, enforcing and reporting framework".