Update to the Climate Change Plan - Key Sectors

This briefing considers the Scottish Government's Draft Update to the Climate Change Plan.For each of the key sectors, it sets out the expected outcomes of the Climate Change Plan published in 2018, recent reports and recommendations, and what changes have been made in light of the adoption of the net-zero emissions target, set by the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019.

Executive Summary

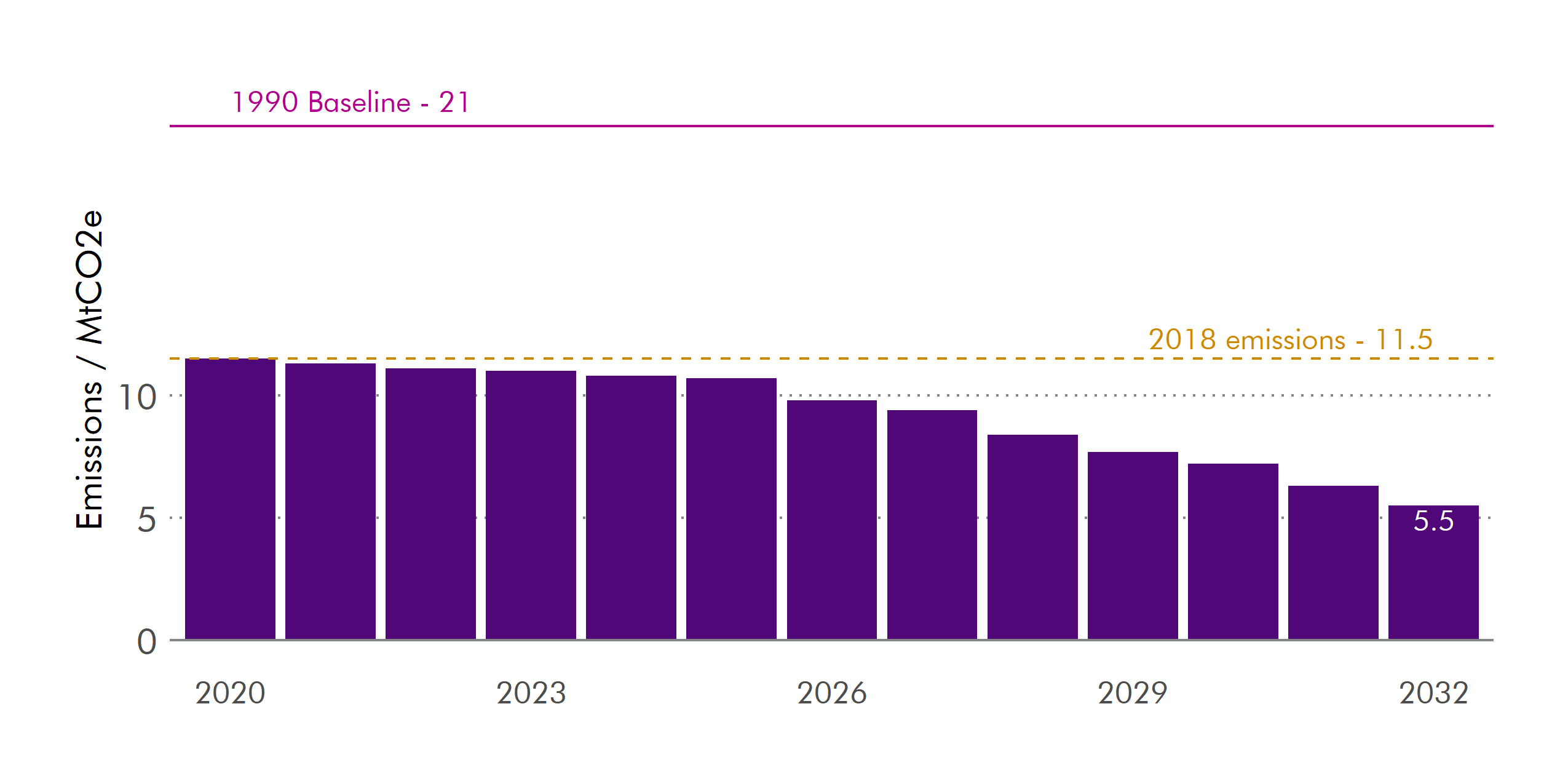

The Scottish Government's draft update to the Climate Change Plan 2018 – 2032 sets out Scotland's path, across eight key sectors, to achieving a 75% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, and ultimately net-zero emissions by 2045. The draft update is a crucial staging post in Scotland's trajectory to net-zero, as it encompasses the interim 2030 target, which independent advisers the Climate Change Committee consider to be "extremely challenging".

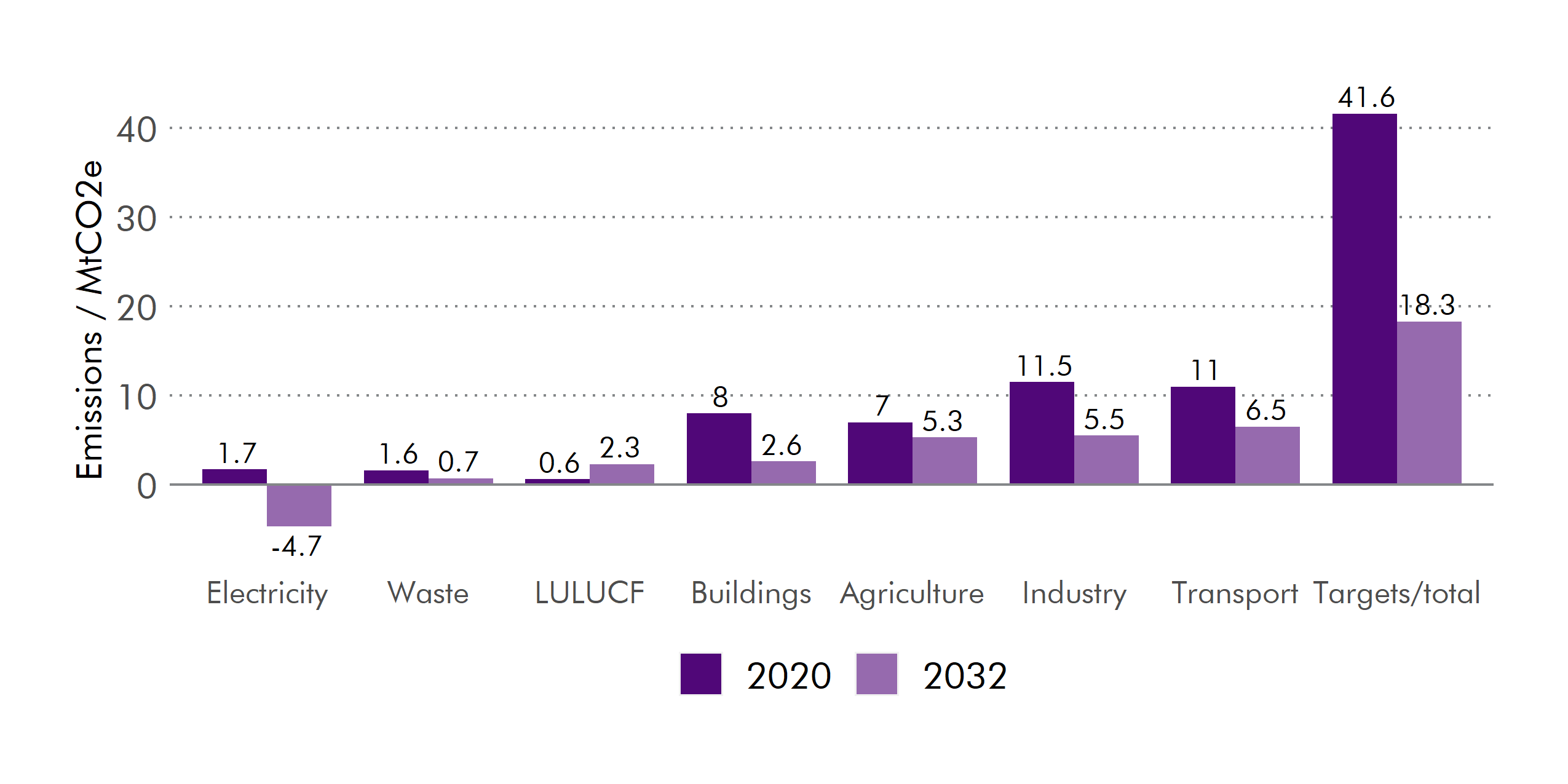

The draft plan anticipates a 56% reduction in total Scottish emissions over its lifetime. By 2032, the following sectoral changes are expected:

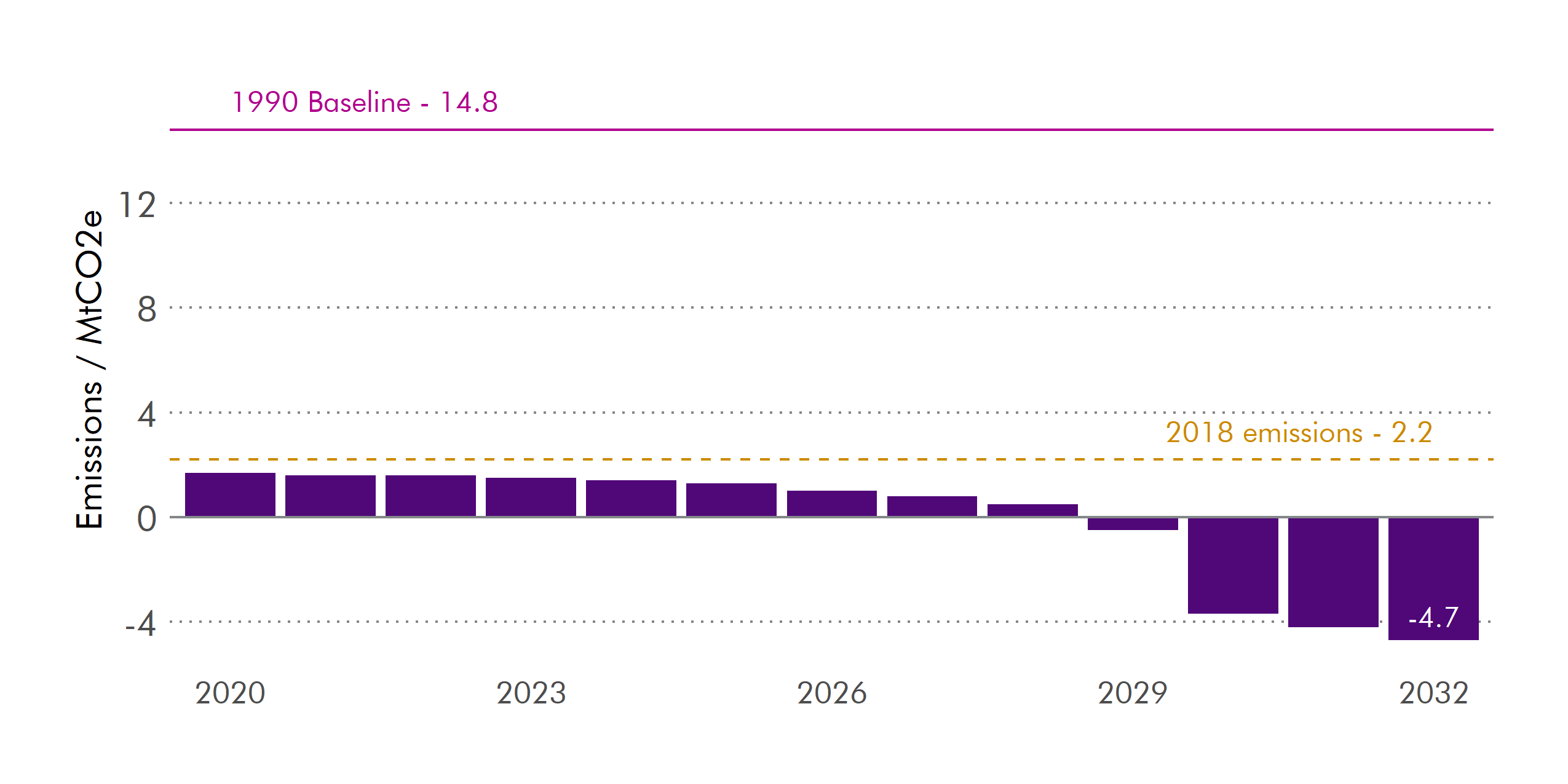

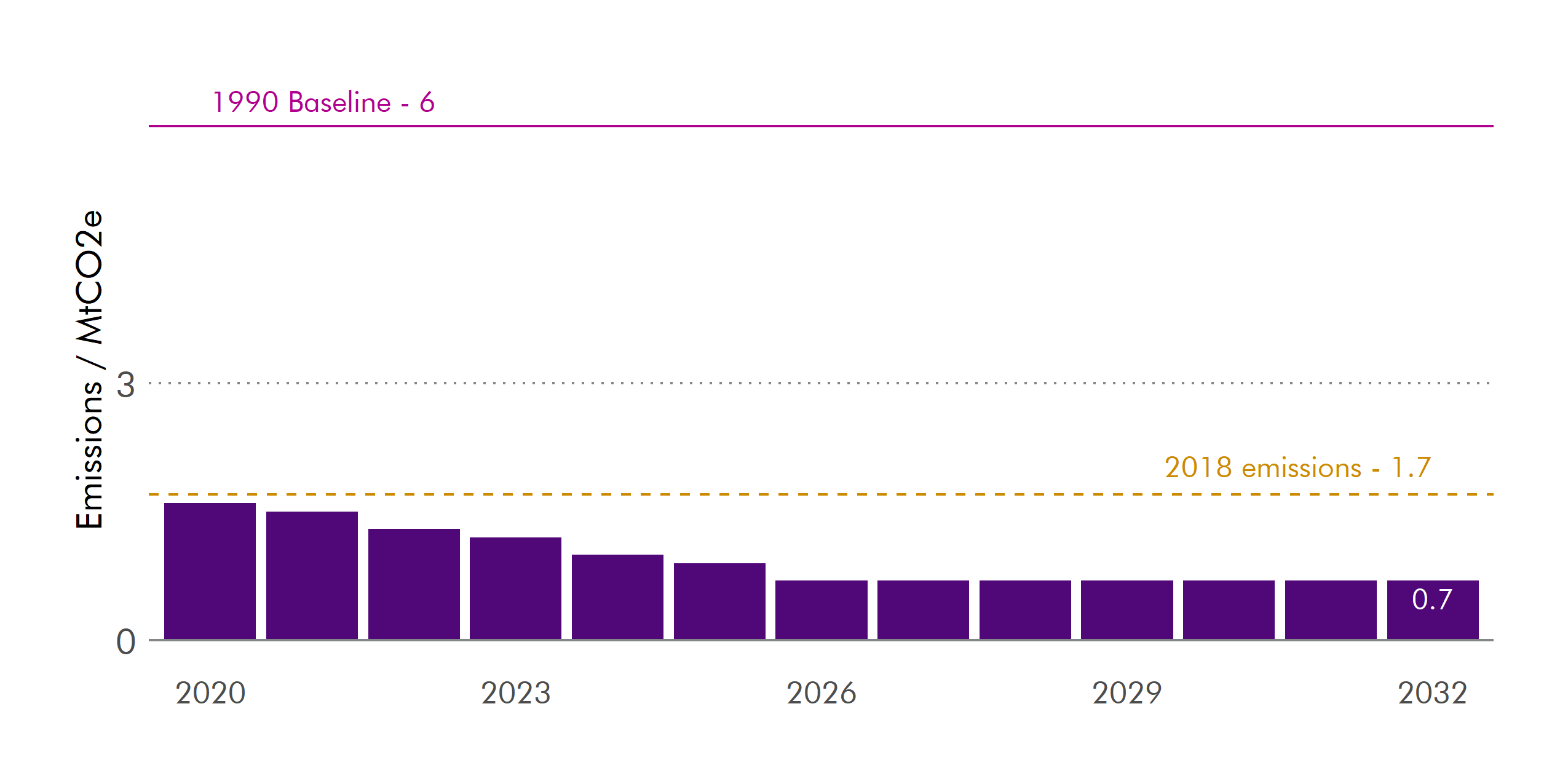

The production of electricity accounted for 5% of total emissions in 2018. Emissions in the Electricity Sector are expected to reduce by 376% with the help of technologies that permanently remove carbon from the atmosphere. These are currently untested at scale; without these technologies, this sector is expected to achieve a 100% reduction. This major reduction in emissions will take place alongside a significant increase in renewable electricity capacity, which is critical to decarbonising other sectors. Key policies and proposals include: new financial support for energy technology innovation, an ongoing focus on local and community energy projects; supporting significant increases in offshore wind by 2030; continuing to press the UK Government to support and invest in energy systems, infrastructure and markets (which are reserved); and a new focus on jobs and the supply chain to ensure that the benefits of this investment can support a green recovery from Covid-19 in Scotland.

Emissions from buildings amounted to 23% of the total in 2018. In the Buildings Sector, emissions are forecast to drop by 68%. This is due to standards and regulations requiring buildings to be more energy efficient, and progress towards a substantial decarbonisation of heat, backed by significant investment and supply chain support. Two new policy outcomes are introduced, centred on green gas (hydrogen and biomethane) supply and a fair heat transition that does not increase fuel poverty, which are also intended to stimulate employment opportunities. Further details will be set out in a Heat in Buildings strategy due to be published later this year.

Transport emissions are Scotland’s single largest source of greenhouse gases, accounting for 36% of the total in 2018; they have only reduced by 0.5% since 1990. For the Transport Sector a reduction in emissions of 41% is expected. The fall is driven by a number of factors, principally a 20% reduction in distance travelled by car and a significant uptake in ultra-low emission vehicles – including buses, railway rolling stock and goods vehicles. Whilst Covid-19 travel restrictions imposed during 2020 have produced a significant temporary reduction in transport emissions, a rebound in emission levels is expected. However, the draft CCPu does not appear to predict any bounce back in emissions following the end of the pandemic.

In 2018, the industry sector was responsible for 28% of Scotland’s greenhouse gas emissions, and these have increased by 6% since the publication of the 2018 CCP; they are second only to the transport sector. In Industry, emissions are anticipated to be 43% lower (52% lower with Negative Emissions Technologies). This shift in ambition is driven by an expectation that an almost total decarbonisation of industry is possible over the next twenty years with the development and widespread adoption of carbon capture, hydrogen energy and negative emissions technologies.

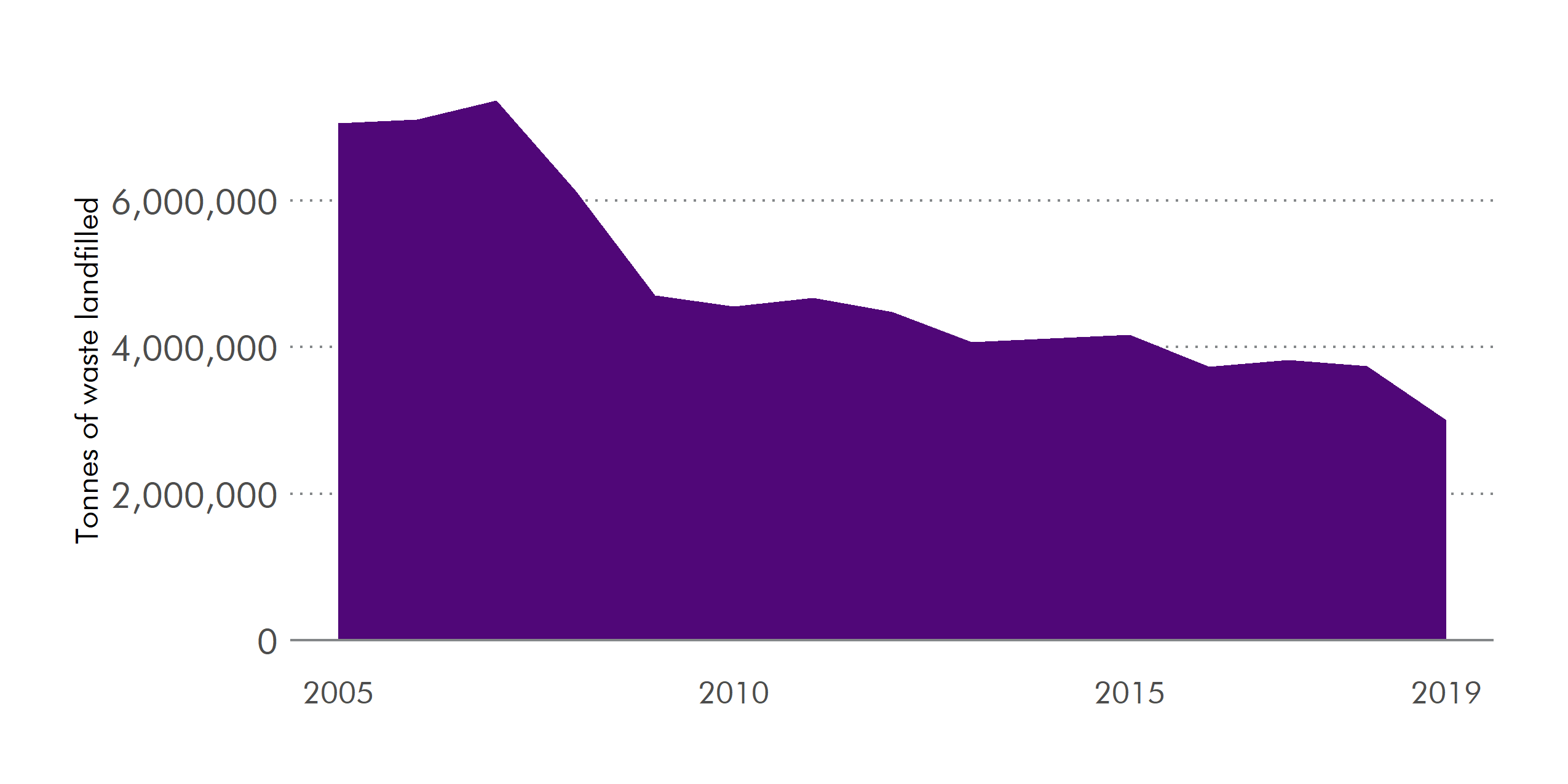

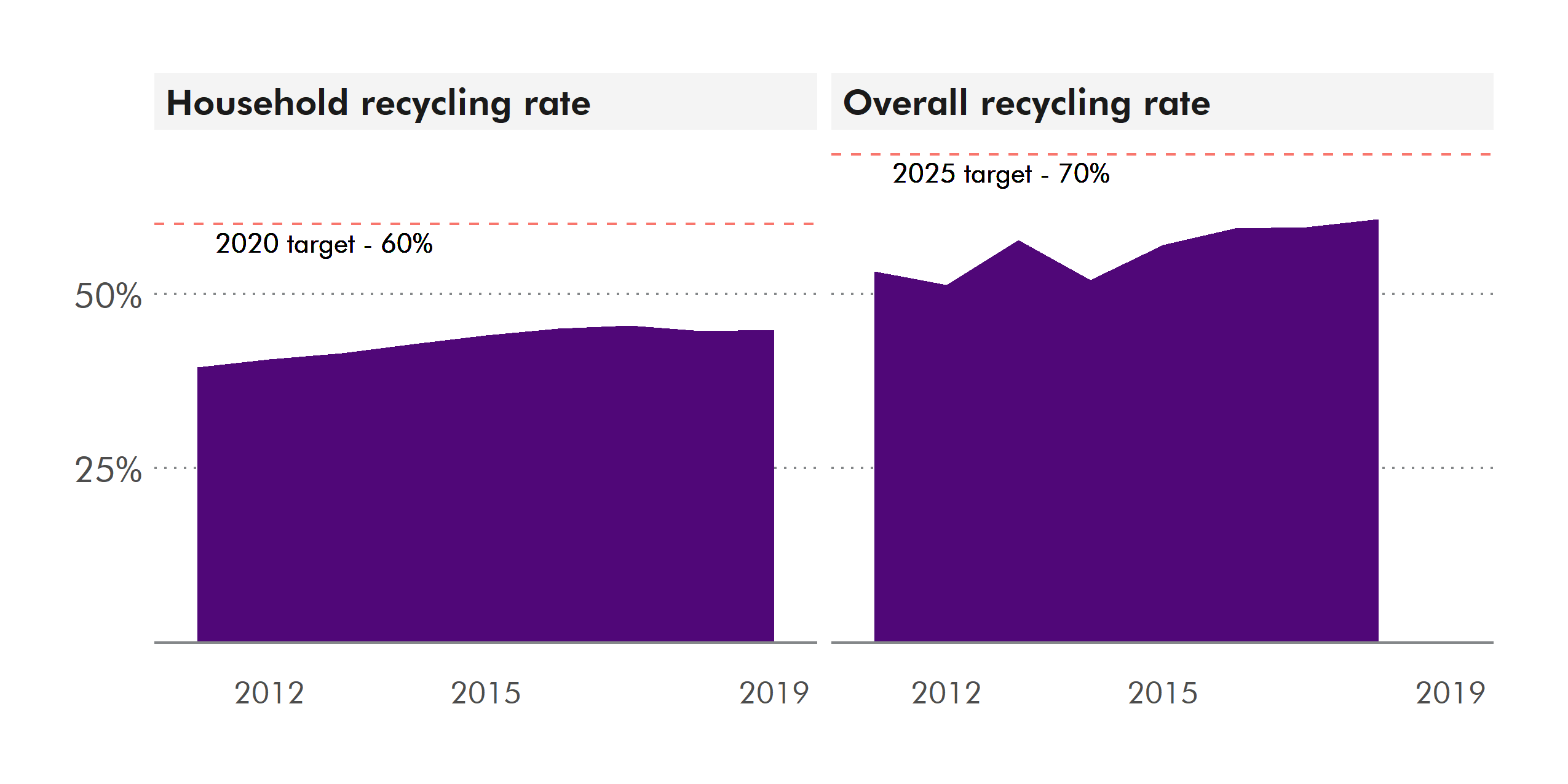

Greenhouse gases from waste accounted for 4% of emissions in 2018 but are more significant in terms of Scotland’s carbon footprint, taking into account emissions associated with imported goods and materials. In the Waste Sector, emissions are expected to reduce by 56%. Policies on food waste and circular economy have been upgraded to form two new Policy Outcomes. Key commitments include to embed circular economy principles across sectors; reduce food waste and end the landfilling of biodegradable municipal waste; to take steps to ban problematic plastics and to work with the UK Government to reform producer responsibility.

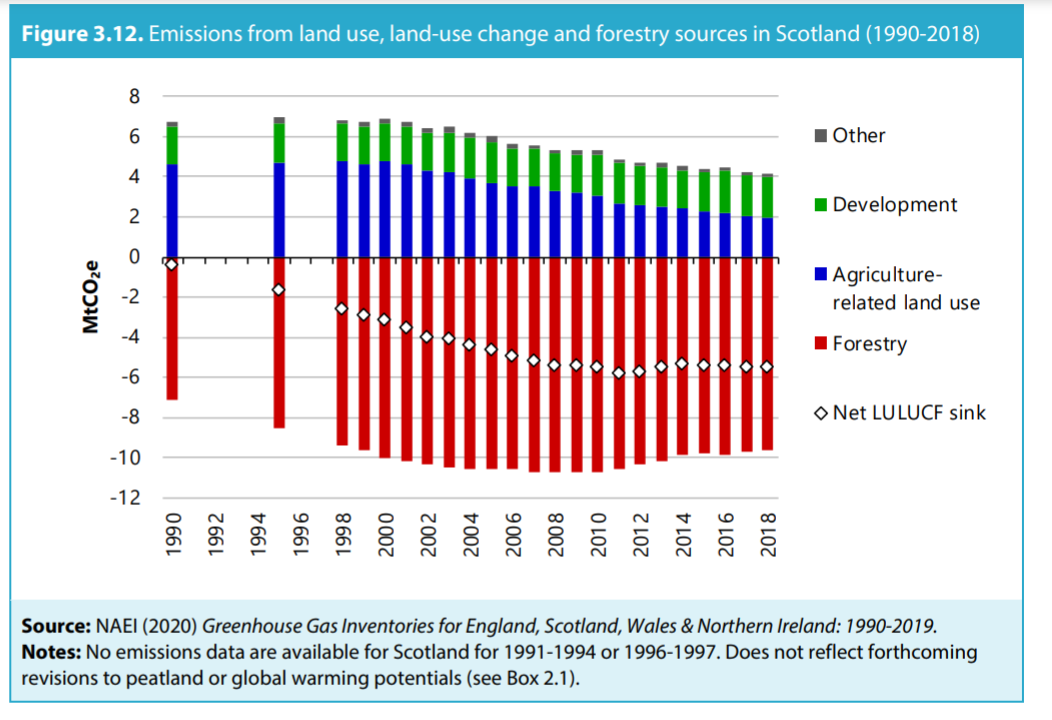

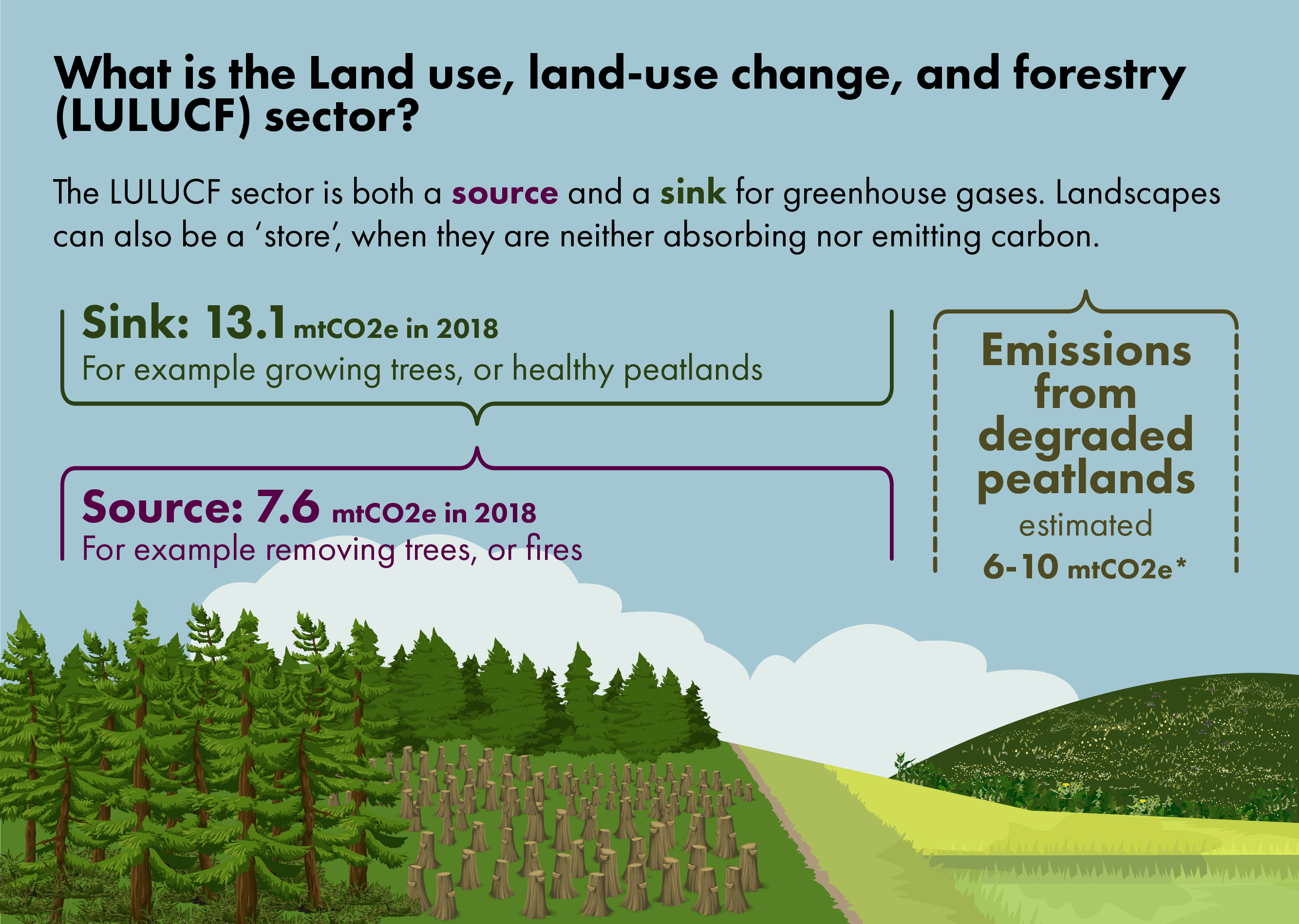

Currently, emissions in land use, land use change and forestry are a net sink – they absorb greenhouse gases; accounting for -13% in 2018. However, this is set to change, and Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry emissions are expected to rise by 283% due primarily to the inclusion of emissions from peatlands, which have not been accounted for up until this point. The two main emissions reduction activities in this sector are forestry planting and peatland restoration. The peatland restoration target remains the same as in the 2018 CCP (250,000ha by the early 2030s), while the woodland creation target has increased from 15,000ha per year in 2024-5 to 18,000ha per year in 2024-5.

Emissions from agriculture contributed to 18% of the total in 2018. In the Agriculture Sector, a 24% reduction in emissions is anticipated – a large increase in ambition since the 2018 CCP, which anticipated only a 9% reduction. The draft CCPu includes one new outcome and a number of new policies and proposals. Policies and proposals include: linking emissions reduction activities to future rural policy, enhanced advisory services, introducing environmental conditionality for support payments, and exploring and developing a range of low-carbon farming interventions. However, the details of some of these policies remain unclear.

Negative Emissions Technologies (e.g. using biomass to generate electricity, coupled with Carbon Capture and Storage) are planned to start permanently remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere by 2029, and significantly ramp up emissions removal in the electricity and industrial sectors from 2030 onwards; equivalent to 23.8% of gross emissions. Whilst these technologies have been proven in test facilities and at small scales, they do not currently exist at scales necessary to remove significant volumes of carbon. Timescales for developing and commissioning are therefore exceptionally tight. Proposals include: a feasibility study to identify specific sites, followed by support for commercial partners; work with the UK Government; investment in research and development, demonstrator projects, and integrating negative emissions technologies with carbon capture and storage infrastructure.

Introduction

The Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 requires the Scottish Government to produce a plan setting out proposals and policies for meeting future greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction targets. Known as the Climate Change Plan (CCP), it is published every five years and generally covers a 15 year timespan. The most recent CCP was published in 2018, and covers the period out to 2032 1.

The Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019 amends the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 and significantly increases Scotland's GHG emissions reduction target (against a 1990 baseline) to net-zero emissions by 2045 i, with interim targets for reductions of:

56% by 2020

75% by 2030

90% by 2040.

Following the adoption of new targets, the Scottish Government had undertaken to revise the 2018 CCP within 6 months of the Act, however this was postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and Securing a Green Recovery on a Path to Net Zero: Climate Change Plan 2018–2032 - update (draft CCPu) was finally published on 16 December 2020 2.

In the same week as the draft CCPu, a Scottish Biodiversity Strategy post-2020: statement of intent was also published. This sets out the Scottish Government's direction for a new biodiversity strategy, and recognises an "increased urgency for action to tackle the twin challenges of biodiversity loss and climate change", which are inextricably linked 3.

The draft CCPu is widely regarded as a crucial staging post in Scotland's trajectory to net-zero emissions, as it encompasses the interim 2030 target, which independent advisers the Climate Change Committee (CCC) consider to be "extremely challenging", and "may not be feasible" 4.

The draft CCPu provides further clarity on Scotland's path to net-zero emissions across the following key sectors:

Electricity

Buildings

Transport

Industry

Waste

Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF)

Agriculture

Negative Emissions Technologies (a new sectoral chapter).

The draft CCPu also contains new information in chapters on Green Recovery from Covid-19, and Coordinated Approach, which encompasses cross-sectoral issues such as energy systems, circular economy, transport, planning and a wellbeing economy.

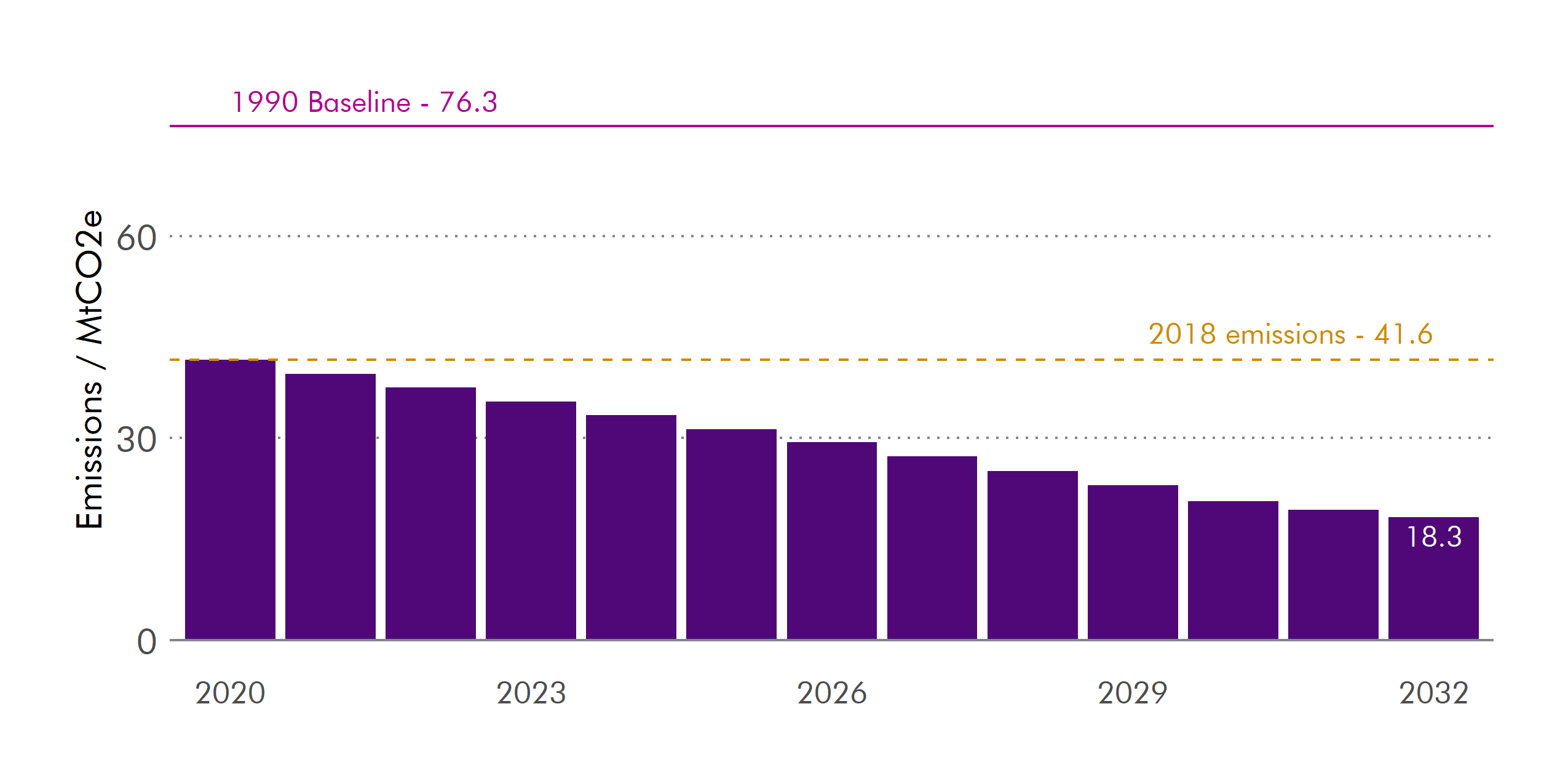

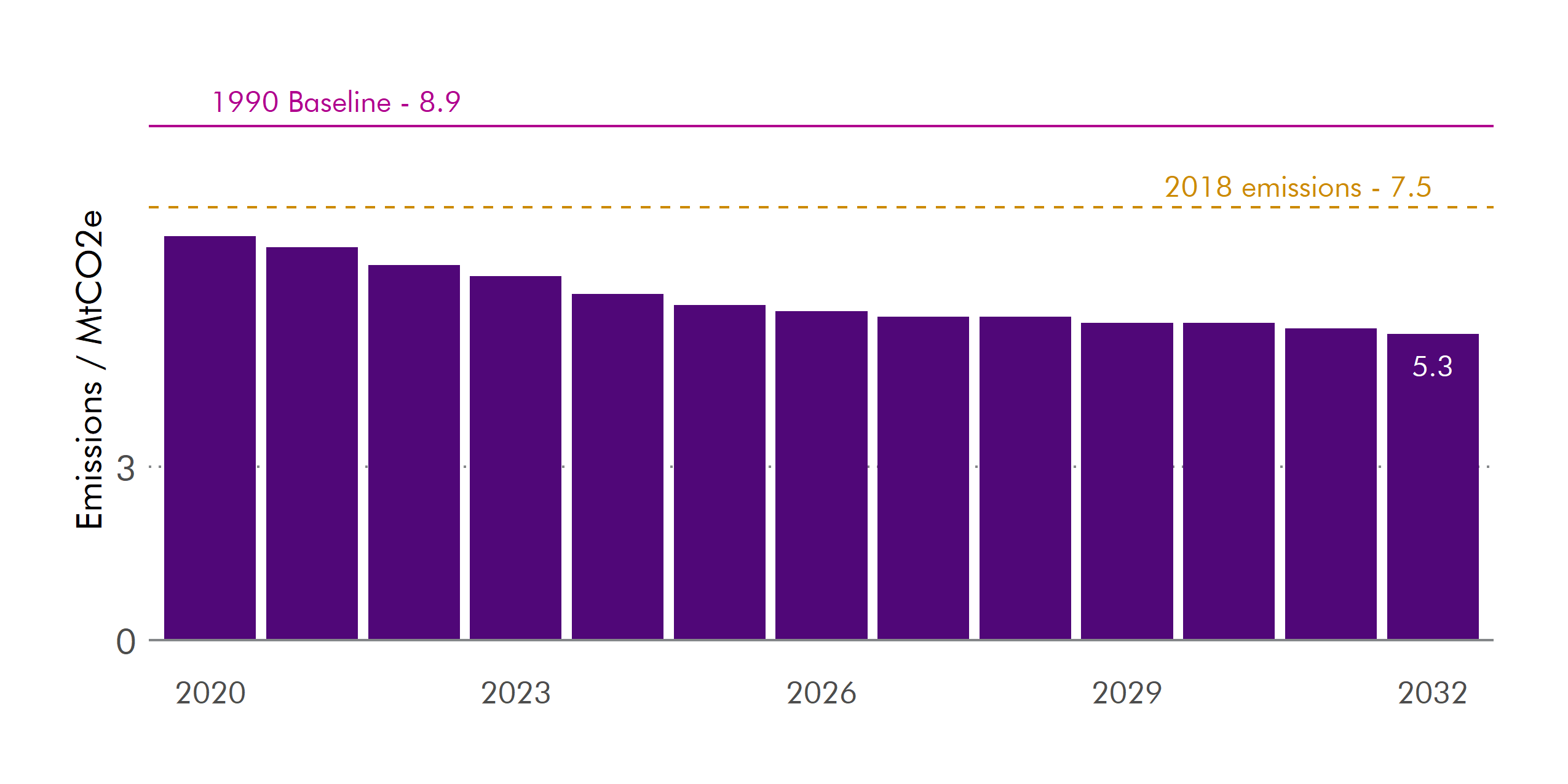

This briefing summarises existing Key Outcomes in the above sectors, considers recent recommendations, and explores the draft CCPu. It should be read in conjunction with SPICe Briefing Update to the Climate Change Plan – Background Information and Key Issues. Figure 1 shows the anticipated emissions reduction pathway out to 2032.

N.B. Due to the breadth of subjects covered and the cross-economy need for decarbonisation, this briefing, if printed or read in PDF format, is 100 pages long. To aid understanding, readers are advised to navigate to the relevant section and to read online.

Emissions Statistics

Emissions statistics for Scotland are published every year and each publication covers emissions up until two years prior. In other words, emissions statistics published in 2018 accounted for 2016 emissions; statistics published in 2020 accounted for 2018 emissions. The draft CCPu states 1:

the current modelling makes use of the most recently published Scottish greenhouse gas inventory data and best current expectations for known upcoming technical changes to the UK inventory

The most recent emissions statistics 2 show that Scotland produced 41.6 MtCO2e in 2018, and the draft CCPu uses this as the baseline for 2020 emissions, however there are some notable differences within the sectors. These are explored in detail in each of the relevant sectors.

Draft CCPu Sectoral Detail

The draft CCPu contains eight chapters covering Scotland's anticipated emissions by key sector. These are summarised in the following figures.

Deriving Sector Emissions Envelopes

The Scottish TIMES model is a high-level analytical model, covering the Scottish energy system, as well as non-energy sectors, including Agriculture, Waste, and LULUCF. It helps to understand key inter-relationships across relevant sectors, and relies on a specific set of data inputs which capture the characteristics of the system being studied, a series of constraints being applied to reflect practical or policy constraints and a set of results being generated that are informed by those inputs and constraints 12.

Annex C of the draft CCPu is crucial in understanding how each of the sectoral GHG emissions envelopesi were derived. It states that 1:

It identifies the least-cost pathway for deployment of technologies, fuels and other carbon abatement measures to meet our final demands and emissions targets.

[...]

These envelopes have been developed through an iterative process which combines evidence, analytical modelling and the application of judgement in the face of considerable uncertainty.

Key points include:

The TIMES model was unable to identify a set of sector pathways consistent with the statutory targets

Therefore, in order to ensure the envelopes met the cross-economy statutory targets, a decision was taken to allocate the necessary additional emissions reductions pro-rata to some sectors

Two sectors were exempted from this additional allocation; Agriculture and Industry

Agriculture was exempted on the grounds of "technical feasibility" and those which would have been allocated to this sector were allocated to LULUCF

Industry was exempted to avoid "carbon leakage"; this refers to the possibility of high-carbon businesses relocating to other countries with weaker emissions targets, potentially resulting in higher global greenhouse gas emissions overall

The emissions envelope for Industry was constrained in the TIMES model to the current EU Emissions Trading Systemii cap to 2020 and then to the assumed rate of a projected EU/UK cap to 2025. Thereafter this envelope followed a linear path to a 90% reduction in 2050, based on the CCC’s advice for that sector.

Electricity

Electricity policy is complex, and the generation and consumption of electricity in Scotland should be considered within the framework of the GB wide grid, which is itself an integral part of a wider European network of interconnectors.

As well as reducing GHG emissions and tackling climate change, key themes in this chapter include: ensuring secure and affordable supplies through demand reduction; addressing fuel poverty; skills development and increased employment; and improved infrastructure.

The promotion of renewable energy, the consenting of electricity generation and transmission development, and energy efficiency are devolved, allowing considerable attention to be focussed on advancing research, development and deployment in these key areas, and giving Scottish Ministers some powers in directing the overall energy mix, including nuclear and other thermal generation via consenting powers. The Scottish Government's Energy Strategy states 1:

[…] there is a great deal of common ground between the Scottish and UK Governments. We will continue, and build upon, our existing inter-governmental partnerships to make sure that we deliver the goals and ambitions in this Strategy.

Context

Scotland is consistently a net exporter of electricity to the rest of the UK – amounting to 28% of all Scottish generation in 2018. Figures for 2018 show that electricity accounted for 22% of overall energy consumption in Scotland. Within this, renewables accounted for 55% of electricity generation, nuclear for 28%, and gas for 15% 1.

The Scottish Government has a target to generate the equivalent of 100% of domestic electricity demand from renewable sources by 2020. This does not mean that Scotland will be fully dependent on renewables, but that they will be the backbone of a broader electricity mix. In 2019, the equivalent of 90.1% of gross electricity consumptioni was from renewables, rising from 76.7% in 2018 2.

Another relevant target is to produce the equivalent of 50% of the energy for heat, transport and electricity use from renewables by 2030. In 2018 this was 21%, rising from 19% in 2017 2.

Of the 41.6 MtCO₂e emitted in 2018, electricity generation accounted for 2.2 MtCO₂e or 5.2% of total emissions - the second lowest after the waste sector (4.1%) 4. This represents an 85% reduction on 1990 levels, but a rise of 7% since 2017 due to an increased use of gas generation at Peterhead. The overall reduction on 1990 levels is due primarily to the closure of both Longannet and Cockenzie coal fired power stations, as well as a reduced reliance on gas 5.

2018 CCP - Electricity

The 2018 CCP 1 has the following key ambitions for the electricity sector:

By 2032, Scotland's electricity system will be largely decarbonised and will come from renewable sources including onshore and offshore wind, hydro, solar, marine and bioenergy

Smart grid technology and better connection will improve the electricity system

At least 1GW of renewable energy will be in community or local ownership by 2020.

Two Policy Outcomes are set out, with various supporting policies and associated 'development milestones':

From 2020 onwards, Scotland's electricity grid intensity will be below 50 grams of carbon dioxide per kilowatt hour (gCO₂/kWh). The system will be powered by a high penetration of renewables, aided by a range of flexible and responsive technologies

Scotland's energy supply is secure and flexible, with a system robust against fluctuations and interruptions to supply.

The 2018 CCP also highlights Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), as a key technology "to provide low carbon flexible power generation". CCS is asuite of technologies and processes which can decarbonise fossil fuel generation. It involves capturing CO₂ emitted from high-producing sources, transporting it and storing it in secure geological formations deep underground. The transported CO₂ can also be reused in processes such as enhanced oil recovery or in the chemical industry, a process sometimes known as carbon capture and utilisation (CCU) 2. The IPCC considers that it would cost 138% more to limit warming to within 2°C without CCS 3.

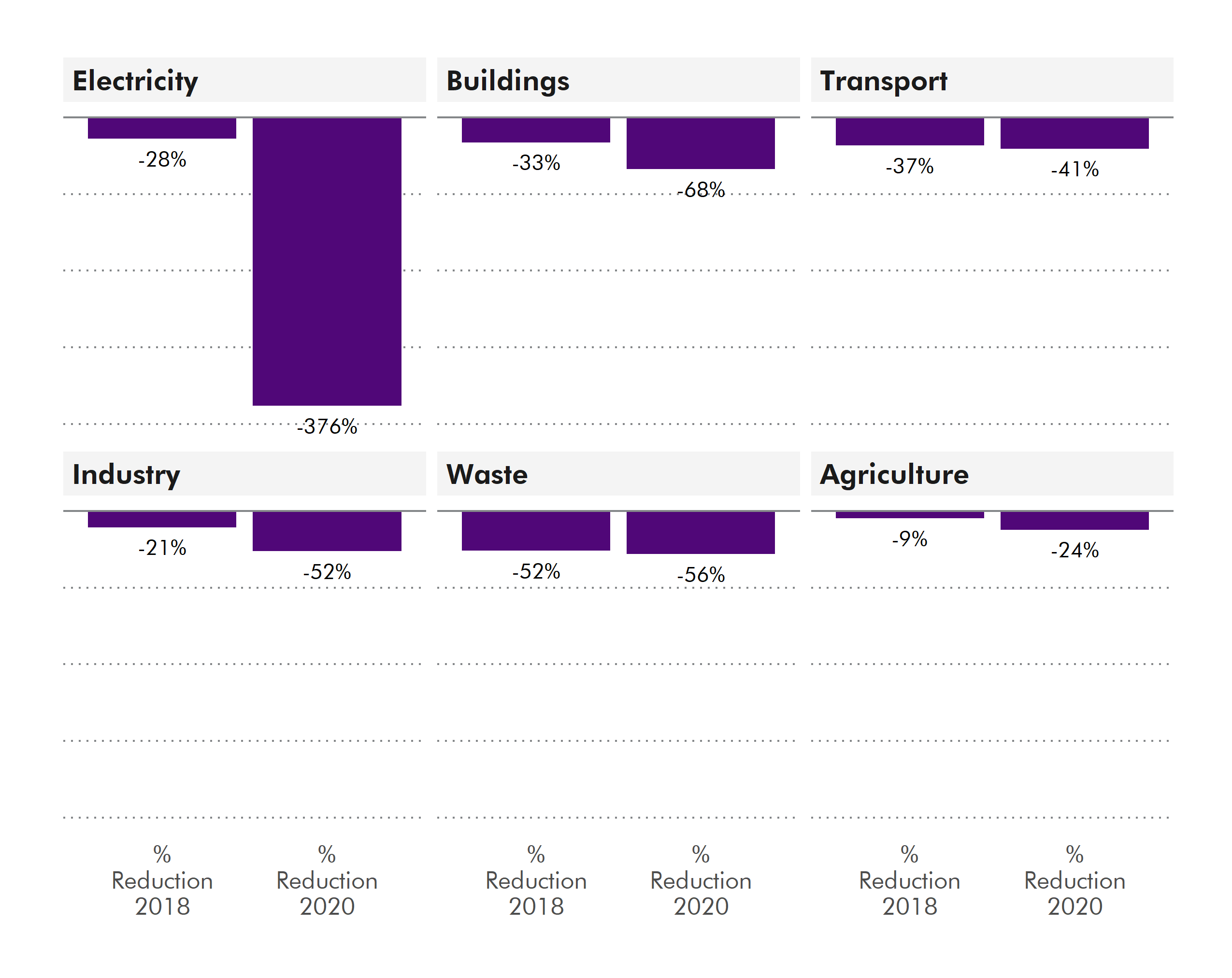

The 2018 CCP expects that, over the lifetime of the Plan (i.e. by 2032) emissions in the electricity sector will have fallen by 28% 1.

CCP Monitoring Report

The 2019 Climate Act requires individual sector by sector monitoring reports to be laid before the Scottish Parliament annually.

In relation to Policy Outcome One the Scottish Government's most recent monitoring report shows that, in 2017, Scotland's grid intensity was 24 gCO₂/kWh, a fall of 56% since 2016. The report states 1:

Renewable electricity generation capacity in Scotland has more than trebled in the last ten years; as of June 2019, there was 11.6 GW of installed capacity across the country.

For Policy Outcome Two the monitoring report states that electricity and gas supplies "remain secure", noting that, in winter 2018/19 peak electricity demand in Scotland was 5.3GW, well "within Scotland’s maximum supply capacity from non-intermittenti sources, which was 10.0 GW". The report states 1 that:

[...] the Scottish Government will continue to engage with network operators and owners, as well as with Ofgem and the UK Government, to ensure that network investment, innovation and regulation remains sufficient to ensure a secure and resilient transmission network, with stronger interconnectors between Scotland and Europe.

Further key points include:

In 2018, electricity generated from renewables increased 6% on 2017 levels (an already record year); this is due primarily to an increase in generation from onshore wind

Installed capacity of renewable generation increased from 10.5 GW to 11.6 GW (10%) from 2018 to 2019

Whilst not all projects will be commissioned, there is 13.0 GW of renewable electricity capacity either under construction (1.1GW), awaiting construction or in planning (10.9GW) - the majority of this is onshore and offshore wind

Wave and tidal is the next largest renewable technology, with 0.38 GW awaiting construction or in planning. There is currently 0.02 GW of this technology operational in Scotland

It is however expected that recent changes to subsidy schemes for renewables will impact on potential new projects, of all sizes

In 2018, an estimated 697 MW of community and locally owned renewable energy capacity was operational. This is a 6% increase on 2017 figures

The Scottish Government targets 1 GW of community and locally owned energy by 2020 and 2 GW by 2030. The 697MW estimated above was 70% and 35%, respectively, towards these targets.

Recent Reports - Electricity

As the backbone of a decarbonised power sector, delivering significant renewable electricity capacity is crucial to achieving net-zero emissions. This section sets out recent scrutiny of progress.

Climate Change Committee Reports

The CCC has published two key pieces of advice, and its annual Progress Report to Parliament in recent months.

Parliamentary, and Other Scrutiny

In June 2020, the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee launched an inquiry to establish the principles that should underpin a green recovery, to identify key actions for change, immediate priorities, potential barriers to implementation and the governance arrangements needed to deliver this. The Committee's report was published in November 2020 1 .

The Committee heard that significant investment in distribution and transmission grid infrastructure as well as high voltage, direct current (HVDC) electric power transmission is needed – there was concern that Ofgem’s forthcoming price control will restrict funding for energy networks.

Further market support for renewables was also considered to be necessary, as well as a robust carbon pricing regime, progressively funded through taxation rather than consumer bills to limit the impact on fuel poverty levels.

In relation to planning, the Committee considered that there should be a presumption in favour of renewables projects set out in National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4). The climate emergency and the achievement of net-zero should also be made material considerations in any planning application.

The Committee urged 1:

[...] the Scottish Government to continue to press both the UK Government and Ofgem to invest in, and enable, the swift development of infrastructure and the energy network to effectively deliver a low carbon transition. Enabling much of this investment relies on action at UK Government level, but is critical to the green recovery, and Scotland’s response to the climate emergency.

Throughout Session 5, the Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee has scrutinised energy policy in Scotland. Most recently, the Three-Part Energy Inquiry, linked an overview of the Royal Society of Edinburgh’s Scotland’s Future Energy Report with consideration of electric vehicle infrastructure, and local energy systems (including community and locally owned energy) 3. Relevant findings include:

No energy policy, however well considered, can solve all of the paradoxes of energy demand and supply, the Committee recognised the challenges in balancing the competing issues of the energy quadrilemma (climate change/affordability/security/sustainability)

Given the scale and complexity of the energy quadrilemma, there is a need for a long-term strategic framework; one covering all aspects of energy, taking a continuous and whole systems approach, and which could include the establishment of an independent expert advisory commission as previously recommended by the Committee.

The foundations for such a framework must be built on good governance, policy expertise, cross-party buy-in (as has been the case for climate change), a whole systems approach, and long-term ownership.

The Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee also has an ongoing interest in the offshore wind sector and Scottish supply chain, in particular why Burntisland Fabrications (BiFab) has failed to gain contracts from recent, local, offshore wind projects 4.

Draft CCPu- Electricity

As previously noted, increasing Scotland's renewable electricity capacity is critical to enabling decarbonisation in other sectors i.e. transport, buildings and industry.

The draft CCPu 1 recognises this, and also notes a continued desire to export to the rest of the UK and to the rest of Europe. Substantial challenges exist, such as maintaining security of supply and resiliencei in the electricity system without fossil fuels and nuclear.

An existing technology, which is considered to be crucial, is pumped storage hydro power, as it can release stored electricity when needed. New technologies will also be needed to move from the existing low carbon system to deliver negative emissions (negative emissions technologies - NETs) initially with a technology known as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS)ii.

The draft CCPu 1 anticipates that, via a range of policies and proposals across three key outcomes, and combined with NETs (considered later in this briefing), the following emissions reduction pathway can be achieved:

A 376% reduction in emissions out to 2032 is expected (100% excluding NETs), in comparison to a 28% reduction in 2018's CCP. The draft CCPu assumes that emissions in 2020 will be 1.7MtCO₂e - 23% lower than in 2018.

As with many of the key sectors, the outcomes, policies and proposals included in the electricity sector of the CCPu have changed from the 2018 CCP, making direct comparisons difficult.

Outcome One

Outcome 1 states that the "electricity system will be powered by a high penetration of renewables, aided by a range of flexible and responsive technologies". New policies in relation to this include publishing a revised Energy Strategy, and a Hydrogen Policy Statement followed by an Action Plan in 2021. The key 2030 target of 50% of all energy consumption (electricity, heat and transport) being from renewables is maintained.

Key proposals in relation to Outcome 1 include:

Introducing new support for energy technology innovation, through the the £180 million Emerging Energy Technologies Fund. This is expected to deliver a "a step change in emerging technologies funding to support the innovation and commercialisation of renewable energy generation, storage and supply"

Ongoing focus on local energy projects through the Community and Renewable Energy Scheme which supports the targets of 1 GW and 2 GW of renewable energy being in local or community ownership by 2020 and 2030. It is not clear why this is included as a proposal, when it is a long established target with associated funding

Researching the potential to deliver negative emissions from the electricity sector

Supporting the development of 8 - 11 GW of offshore wind by 2030 through the actions set out in the Offshore Wind Policy Statement.

The success of these policies and proposals is measured by three indicators; the installed capacity and planned capacity of renewable generation, and the carbon intensity of the electricity grid. This latter indicator was one of the key outcomes of the 2018 CCP.

Outcome Two

Outcome 2 aims for Scotland's electricity supply to be "secure and flexible, with a system robust against fluctuations and interruptions to supply". This is essentially the same as in 2018's CCP, and the key policy related to this is to:

Support the development of technologies which can deliver sustainable security of supply to the electricity sector in Scotland and ensure that Scottish generators and flexibility providers can access revenue streams to support investments.

A series of proposals support this outcome, the majority of which are reserved to the UK Government, and which are maintained from the previous CCP. These include: pressing for favourable market conditions and incentives to support investment in infrastructure; collaboration to ensure that systems and networks use data and digital technologies to become smarter and more flexible; and supporting (within devolved competence) increased interconnection to aid security of supply.

New proposals include consulting on technologies that can support the delivery of sustainable security of supply (e.g. energy storage and smart grid technologies) and developing a series of whole system energy scenarios to guide investment.

The success of these policies and proposals is measured by loss of load expectation in hours per year. In short, this is the expected time for which available generation is insufficient to meet demand. It is a standard security of supply metric used in the electricity market, and the current GB standard is below 3 hours per year.

Outcome Three

Outcome 3 expects that Scotland will secure "maximum economic benefit from the continued investment and growth in electricity generation capacity and support for the new and innovative technologies which will deliver our decarbonisation goals". This new focus on jobs and the supply chain appears to respond to many of the concerns and issues that have been raised by the Parliament's Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee in relation to the BiFab, the offshore wind sector and Scottish supply chain Inquiry 1.

No policies, but three proposals are set out:

Press the UK Government to reform the subsidy mechanism (known as Contracts for Difference) so that more economic benefits are available to domestic supply chains

Introduce new requirements for developers to include supply chain commitments when applying to the ScotWind leasing process run by Crown Estate Scotland

Identify and support major infrastructure improvements to support the Scottish supply chain.

There are no indicators associated with this outcome.

Buildings

Context

The buildings chapter of the draft CCPu includes the residential sector (all of Scotland's homes) and the services sector (all non-domestic buildings in the public and commercial sectors).

There around 2.48m homes in Scotland and 200,000 non-domestic buildings in Scotland, including around 20,000 public sector buildings.

In 2018, direct emissions from buildings accounted for 9.4 MtCO₂e, around 23 % of total Scottish emissions. Direct emissions from buildings increased by 4% from 2017, which is likely to be driven by the extreme cold weather event, the 'Beast from the East', in March 2018 12.

Most emissions from buildings are generated from heating space and heating water. In 2018, 81% of Scottish households (around 2.0 million) used mains gas for heating and cooking, 10% used electricity and 6% used oil 3. In the service sector, the majority of energy is used for cooling.

Policies which can help to reduce emissions from buildings are governed by a mix of reserved and devolved powers. Under the 1998 Scotland Act, heat policy, energy efficiency building standards and planning consent for infrastructure are devolved. However, regulation of energy markets, oil and gas, electricity and gas networks and consumer protection remain reserved to the UK Government.

As the Scottish Government's 2020 Programme for Government noted 4, to achieve Scotland’s net‑zero emission targets, emissions from space and water heating need to be effectively eliminated by 2040‑45. This will require action to continue to reduce demand for heat in homes and buildings through energy efficiency measures. It will also require fossil fuel heating systems to be replaced with renewable or zero emissions sources such as heat pumps, solar water heating and biomass boilers.

2018 CCP - Buildings

The 2018 CCP is focussed on improving the energy efficiency of buildings and increasing the use of low carbon heating systems.

The plan has four policy outcomes (which appear to have been replaced by new policy outcomes in the draft CCPu):

| 2018 Climate Change Plan: Buildings Policy Outcomes |

|---|

| 1. By 2032, the energy intensity of Scotland’s residential buildings will fall by 30% on 2015 levels2. By 2032, the emissions intensity of residential buildings will fall by at least 30% on 2015 levels3. By 2032, non-domestic energy productivity to improve by at least 30% on 2015 levels4. By 2032, the emissions intensity of the non-domestic sector will fall by at least 30% on 2015 levels |

N.B. Energy intensity relates to the amount of energy required and therefore relates to the energy efficiency of buildings. Reducing heat demand from insulation measures is one factor that contributes to reducing total energy consumption but other factors, including efficiency improvements in boilers or other household equipment, also contributes.

Emissions intensity relates to the greenhouse gas emissions associated with how heat is produced, and is therefore linked to the carbon intensity of the heating source.

Other targets were outlined in the 2018 plan, including that:

Low carbon technologies (e.g. heat networks) will supply heat to 35% of domestic and 70% of non-domestic buildings by 2032

Where technically feasible by 2020, 60% of walls will be insulated and 70% of lofts will have at least 200mm of insulation in the residential sector.

There is a wide range of policy action to meet these outcomes and targets. This briefing does not attempt to cover all these in detail. However, the following summarises some of the main policies and policy developments since publication of the plan.

Buildings: policies and recent developments

Many of the policies in the 2018 CCP are encompassed in the Scottish Government's Energy Efficient Scotland programme Energy Efficiency Scotland. The Programme will run to 2040 and brings together strategies and action to remove poor energy efficiency as a driver of fuel poverty and reduce carbon emissions through more energy efficient buildings and decarbonising heat supply.

In relation to energy efficiency specific policies include:

TheNon Domestic Public Sector Energy Efficiency (NDEE) Framework designed to support public and third sector organisations procure Energy Efficiency retrofit work

Under the UK Government’s Energy Company Obligation scheme, medium and larger energy suppliers fund the installation of energy efficiency measures in British households (powers over their design and delivery have been devolved).

The Energy Efficient Scotland Route Map, published in May 2018, proposed a set of longer-term energy performance standards for all buildings in Scotland, including specific targets for properties with fuel poor households 1. These standards are based on an Energy Performance Certificate Rating (EPC) which present the calculated greenhouse gas emissions for buildings on a scale from A (highest) to G (lowest):

All homes should be Energy Performance Certificate -Efficiency Rating Band C by 2040 (where technically feasible and cost effective)

All homes with households in fuel poverty to reach EPC C by 2030 and EPC B by 2040 (where technically feasible, cost effective and affordable).

How this standard will be implemented will vary between tenures, with social rented housing expected to achieve higher energy efficiency standards earlier than other tenures.

The Scottish Government has also announced that all new buildings given consent from 2024 will need to be zero-emission. Its recently launched scoping consultation on the New Build Heat Standard sets out its high-level vision for this 2.

The Fuel Poverty (Targets, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Act 2019 set a target to eliminate fuel poverty as far as possible, with no more than 5% of households to be in in fuel poverty and no more than 1% in extreme fuel poverty by 2040.

Local authorities have also been piloting the development of local heat and energy efficiency strategies to establish authority area-wide plans and priorities for systematically improving the energy efficiency of buildings and decarbonising heat.

Low carbon heating policies include:

The Scottish Government’s District Heating Loan Fund, designed to help address financial and technical barriers to district heating projects by offering low interest loans. A Heat Network Partnership also aims to boost the uptake of low carbon heat technologies in Scotland and focuses the efforts of a number of agencies working in this area

The Heat Networks (Scotland) Bill provides a framework for regulation and licensing of district and communal heating networks across Scotland. Heat networks can use a variety of heat sources and are often more efficient than individual fossil fuel heating systems They can also be run fully from renewables, recovered waste, or surplus heat sources where appropriate

The Low Carbon Infrastructure Transition Programme(LCITP), co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), supports investment in decarbonisation of business and the public sector. Additionally, the UK Government Renewable Heat Incentive promotes the use of renewable heat.

Recent Reports: Buildings

The Climate Change Committee's 2020 Progress Report to Parliament acknowledged that some progress with emissions from buildings over the longer term has been made reflecting genuine improvements. Total emissions have fallen by 16% from 2008 to 2018, with progress mainly seen in residential buildings 1.

The Scottish Government’s 2019 Climate Change Plan Monitoring report also identified increasing energy efficiency levels of buildings, with a 6% increase in dwellings rated as EPC band C or better between 2015 and 2017 2. The Report also monitors progress towards the 2018 Plan’s four policy outcomes through output indicators. For all four indicators the report concluded that it was too early to assess whether the targets were on track to be met.

Despite progress with improvements in energy efficiency, the Climate Change Committee states that the bulk of the challenge to decarbonise buildings in Scotland remains. There is a need to shift away from fossil gas to low-carbon heat solutions and to improve the energy efficiency of existing homes at a faster rate.

The bulk of the challenge to decarbonise buildings in Scotland remains, with the greatest challenge on decarbonising heating and hot water:

Climate Change Committee. (2020, October). Reducing emissions in Scotland – 2020 Progress Report to Parliament. Retrieved from https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/reducing-emissions-in-scotland-2020-progress-report-to-parliament/ [accessed 6 December 2020]

Low-carbon heat in existing homes. The major challenge for the buildings sector remains the need to shift homes away from fossil gas to low-carbon heat solutions. The last decade has seen limited progress in this area under the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI), although Scotland has a proportionately higher number of accreditations on the GB-wide RHI scheme relative to its population. There were fewer than 13,500 heat pumps in Scotland in 2018. Scotland is not currently on track to meet its 2020 target of 11% of non-electric heat from renewable sources, let alone a level of low-carbon heat that is consistent with Net Zero

Energy efficiency in existing homes. The major challenge of widespread building renovation and retrofit to increase building heat efficiency is yet to be addressed, although some progress in improving EPC of homes has been made, particularly in houses moving out of EPC bands D and E and into band C

New homes. Scotland's new build standards – due to be legislated in 2021 – must ensure that all new homes use low-carbon heat, are ultra energy efficient and are designed for a changing climate.

In terms of non-residential buildings, the Committee noted that the Scottish Government was yet to set out its proposals for non-domestic buildings, including a benchmarking mechanism to create a long-term energy efficiency standard and setting regulatory ‘backstop’ dates as milestones for non-residential buildings.

The Climate Emergency Response Group's report, published in November 2020, made a similar assessment of Scottish Government progress. It identified areas of positive progress including, large multi-year funding commitments, doubling of heat pump installations and heat pump sector deal and the target of zero emissions from heating buildings by 2040 4.

On the other hand, the report identified gaps and concerns including a lack of policy signal in terms of regulating energy performance standards for existing buildings and that the strategy for non-domestic buildings remains unclear. In their report the Group argued that issues around public sector capacity to deliver heat networks remain unresolved, preventing increased capital spend in the long run.

In their advice to the Scottish Government on achieving the interim 2030 target of a 75% reduction in GHG emissions, the CCC indicated that this target might not be feasible. However, as this is a statutory target it provided advice on how progress could be made including the additional retrofit of hybrid heat pumps.

It also suggested that there could be accelerated scrappage of high-carbon assets, for example, gas boilers could be replaced before they reach the end of their natural life. However, it also identified risks to this approach as it, “carries extra cost to consumers or public expenditure and risks undermining popular support for the transition. It also increases embedded emissions through the production of new assets” 5.

Recent Parliamentary scrutiny of a Green Recovery from Covid - 19 by the Environment, Climate Change and Environment Committee made a key recommendation that 6:

The Scottish Government, develop, fund and mandate a comprehensive programme to bring Scotland’s existing housing stock, particularly pre-1919 tenements and other hard to treat homes, up to an improved and sustainable level of energy efficiency, in line with the recommendations of the CCC. A fresh approach is required to ensure that those living in conservation areas and listed buildings have access to the best performing technologies, and that their decarbonisation efforts are not hampered by historic designations.

Draft CCPu - Buildings

The draft CCPu emphasises the transformational change needed to progress to net-zero carbon by 2045.

The zero emissions heat transition will involve changing the type of heating used in over 2 million homes and 100,000 non-domestic buildings by 2045, moving from high emissions heating systems, reliant on fossil fuels, to low and zero emissions systems such as heat pumps, heat networks and potentially hydrogen [...]

We estimate that around 50% of homes, or over 1 million households, will need to convert to a low carbon heating system by 2030 to ensure our interim statutory targets are met […]

[...] up to an additional 50% of non-domestic buildings will need to be converted to low and zero emissions heating by 2030.

Scottish Government. (2020, December). Climate Change Plan Update. [accessed 6 December 2020]

Within the context of the green recovery and fair and just transition, the update places a greater emphasis on the economic impact of investments in energy efficiency and low carbon heating technologies than the 2018 plan did. It also makes more closer links to the fuel poverty agenda with an emphasis that delivery on targets will need to be developed:

in a way that carefully coordinates the dual challenges of decarbonisation and tackling fuel poverty to ensure a fair and just transition.

Scottish Government. (2020, December). Climate Change Plan Update. [accessed 6 December 2020]

The plan identifies the key things that are needed to deliver the necessary changes, including:

Rapid growth in the supply chain ahead of the mass rollout of zero and low emissions heating systems commencing in the mid-2020s

Further technology innovation

Cost reductions and increased familiarity with and adoption of zero emissions heating technologies by people and businesses

The wider energy system will have to transform to be able to supply secure and affordable zero emissions electricity at scale. Furthermore, they depend upon the right market and pricing signals and regulations being in place

Designing policies that do not increase energy debt.

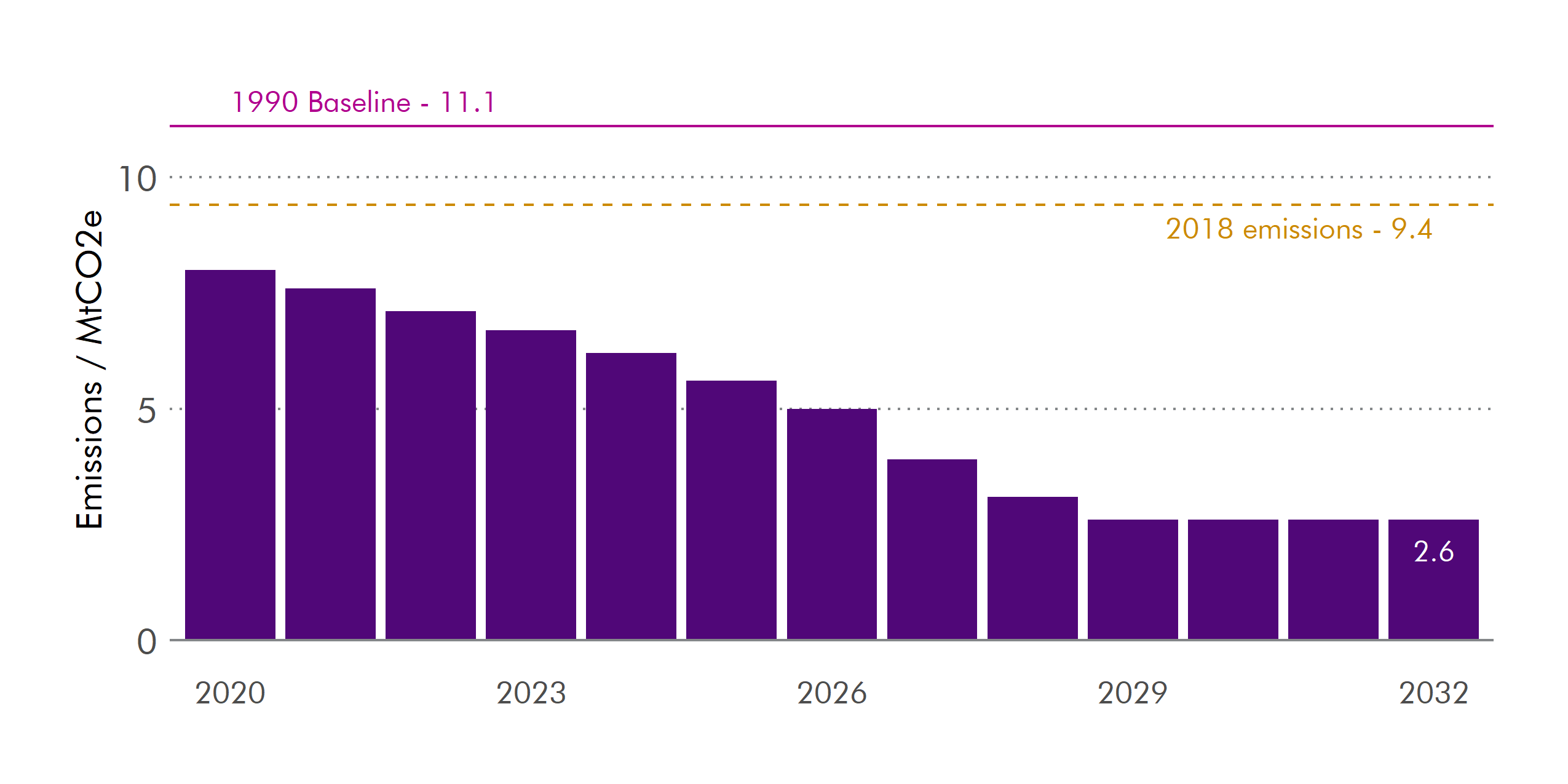

Figure 5 shows the anticipated emissions reductions in buildings between 2020 and 2032. By 2032 emissions from buildings are expected to reduce by 67.5% to 2.6 MtCO₂e. This reduction is substantially greater than the 32.6% reduction (from 2018 to 2032) projected in the 2018 CCP. Emissions in 2020 are projected to be 8 MtCO₂e - 15% lower than in 2018.

Policy Outcomes and Policies

The draft CCPu sets out 4 policy outcomes which appear to replace those in the 2018 plan. Outcomes 1 and 2 are similar to the 2018 plan and relate to low carbon heating and energy efficiency. However, unlike the 2018 plan, there is no distinction between residential and non-residential buildings.

The second two outcomes relating to green gas supply and a fair heat transition that stimulates employment opportunities are new.

Outcome 1: The heat supply to our homes and non-domestic buildings is very substantially decarbonised, with high penetration rates of renewable and zero emissions heating.

Outcome 2: Our homes and buildings are highly energy efficient, with all buildings upgraded where it is appropriate to do so, and new buildings achieving ultra-high levels of fabric efficiency.

Outcome 3: Our gas network supplies an increasing proportion of green gas (hydrogen and biomethane) and is made ready for a fully decarbonised gas future.

Outcome 4: The heat transition is fair, leaving no-one behind and stimulates employment opportunities as part of the green recovery.

The draft CCPu sets out 47 policies to achieve the above policy outcomes. Of these, nine have been maintained from the 2018 plan, 17 have been ‘boosted’, 19 new polices have been introduced as have 2 new UK Government policies. The new policies mainly support the development of heat networks and policy outcome 4.

As recommended by the Climate Change Committee, the Scottish Government set out its intention to publish a Heat in Buildings Strategy which brings together the proposed Heat Decarbonisation Policy Statement with the Energy Efficient Scotland Route Map (publication of this has been delayed to January 2021).

The draft CCPu provides a summary of the policies that will be set out in more detail in the Heat in Buildings Strategy. Early action to 2025 will focus on increasing deployment rates of zero and low emissions heating through three broad mechanisms (listed below in bold). This briefing does not summarise all the relevant policies but provides some examples:

Standards and Regulation: the Scottish Government commits to putting in place standards and regulation for heat and energy efficiency, where it is within legal competence, to ensure that all buildings are energy efficient by 2035 and use zero emission heating and cooling systems by 2045. This represents an acceleration of the current aim of all buildings meeting EPC band C by 2040. However, some groups (such as the Existing Homes Alliance) have argued that this target should be accelerated even further to 2030

Significant investment: the plan references the 2020 Programme for Government’s announcement of £1.6bn investment in heat energy efficiency in the next parliament. There is a commitment to design programmes so as not to exacerbate fuel poverty. Future delivery programmes will be designed to significantly accelerate retrofit building with new programmes to be in place from 2025. The rate of zero emissions heat installations in new and existing homes is planned to double every year to 2025

Supply chain support: over the next 12 months the Scottish Government plans to build a more detailed understanding of the potential for supply chain growth. Other actions include setting out a supply chain strategy and new skills requirements for installers, designers and retrofit coordinators.

The update recognises that a large part of emissions reductions is predicated on some kind of individual, or societal behavioural change. It refers to plans to set out clear messages and support for building owners on what delivering a net zero emissions buildings will mean for them. Furthermore, the Scottish Government will provide enhanced support to households through existing programmes such as Home Energy Scotland.

Asks of the UK Government

As some of the matters affecting the progress of emissions reductions from buildings are reserved, the draft CCPu sets out the Scottish Government’s ‘asks’ of the UK Government. Of relevance to the buildings chapter, the Scottish Government has asked the UK Government to:

Accelerate the development of negative emissions technologies, carbon capture and storage, and hydrogen as essential components of our energy system

Accelerate demonstration of the technological solutions to cutting emissions from our homes and buildings, and in particular set out clear timescales for taking strategic decisions about the future scale and pace of decarbonisation of the gas network to support delivery of our targets for heat in buildings

Update energy regulation by giving Ofgem a statutory objective to support the delivery of net zero and interim statutory greenhouse gas emissions targets and address the imbalance in pricing for electricity and gas to better incentivise the deployment of zero emissions heating technologies.

Revised Monitoring Framework

The outcomes indicators for the 2018 Plan have been reviewed. This has led to a revised set of eight indicators for the Buildings chapter reflecting changes to the policy outcomes (see page 246 of the draft CCPu).

The changes in energy intensity and EPC ratings will still be measured as they were in the 2019 monitoring report. There is ongoing work in developing the monitoring framework. One of the indicators is the % of heat in buildings from low greenhouse gas emission sources. The target for indicator will be determined in 2021.

A policy tracker monitoring implementation of specific policies and proposals will also be developed.

Transport

Context

In 2015, transport became Scotland’s 1 single largest source of greenhouse gas emissions. In 2018, Scottish transport produced emissions equivalent to 14.8 million tonnes of CO₂ – just 0.5% lower than was produced in 1990. By contrast, total Scottish greenhouse gas emissions fell by 45.5% over the same period.

The biggest generator of Scottish transport emissions in 2018 were cars, accounting for 39% of total transport emissions, followed by shipping (16%), aviation (15%), light goods vehicles (13%), heavy goods vehicles (13%), bus/coach (4%) and rail (1%) – the total does not equal 100 due to rounding.

The Climate Change Committee note in its 2020 Progress Report to Parliament 2 that:

The current trend on transport emissions is off-track for meeting Scotland's interim emissions reduction targets and net zero

Despite policies such as Smarter Choices Smarter Places and the Cycling Action Plan, there has been no significant behavioural shift away from cars towards public transport, walking and cycling in Scotland in the last decade

The ambition in the 2019-20 Programme for Government to aim for zero emission or ultra-low-emission city centres by 2030 will require the provision of ultra-low-carbon public transport options, cycling routes, and extensive deployment of electric vehicle recharging infrastructure to support a shift away from the use of conventional vehicles.

2018 CCP - Transport

The current version of the Climate Change Plan, published in 2018, predicted a 37% reduction in transport emissions between 2018 and 2032, falling from 12.8 MtCO₂e to 8.1 MtCO₂e. This fall would be delivered through the achievement of eight transport policy outcomes. These are set out below, along with an indication whether they have been carried over, superseded or no longer feature in the draft Climate Change Plan update:

| Policy outcome | Status in CCPu | |

| 1 | Average emissions per kilometre of new cars and vans registered in Scotland to reduce in line with current and future EU/UK vehicle emission standards: | Does not feature |

| 2 | Proportion of ultra-low emission new cars and vans registered in Scotland annually to reach 100% by 2032. | Date brought forward to 2030 |

| 3 | Average emissions per tonne kilometre of road freight to fall by 28% by 2032. | Does not feature |

| 4 | Proportion of the Scottish bus fleet which are low emission vehicles has increased to 50% by 2032. | Superseded by new bus decarbonisation outcome |

| 5 | By 2032 low emission solutions have been widely adopted at Scottish ports and airports | Carried forward |

| 6 | Proportion of ferries in Scottish Government ownership which are low emission has increased to 30% by 2032. | Carried forward |

| 7 | We will have electrified 35% of the Scottish rail network by 2032. | Superseded by new rail decarbonisation outcome |

| 8 | Proportion of total domestic passenger journeys travelled by active travel modes has increased by 2032, in line with our Active Travel Vision, including the Cycling Action Plan for Scotland Vision that 10% of everyday journeys will be by bike by 2020. | Does not feature |

The delivery of these eight outcomes was reliant on 35 policies and proposals. Of these 35, the draft CCPu includes four polices or proposals that have been “boosted” and 12 that are unchanged. The other 19 do not feature in the draft CCPu.

Initial progress towards meeting the outcomes set in the 2018 CCP was reported in the 2019 Monitoring Report. However, this notes that:

..it is too early to make an assessment on the majority of indicators.

This was largely due to transport data being either unavailable or insufficient for any assessment to be made.

Recent Reports - Transport

Transport Scotland sets out the vision for the development of Scotland’s transport system over the next 20 years in the 1 National Transport Strategy 2 (NTS2), published in February 2020. The vision being:

We will have a sustainable, inclusive, safe and accessible transport system, helping to deliver a healthier, fairer and more prosperous Scotland for communities, businesses and visitors.

This vision is supported by four priorities, one of which is “takes climate action”. The form of this action is set out in six policies:

Reduce emissions generated by the transport system to mitigate climate change

Reduce emissions generated by the transport system to improve air quality

Ensure the transport system adapts to the projected climate change impacts

Support management of demand to encourage more sustainable transport choices

Facilitate a shift to more sustainable and space-efficient modes of transport for people and goods

Improve the quality and availability of information to enable all to make more sustainable transport choices.

NTS2 also embeds an overarching sustainable transport hierarchy, and associated sustainable investment hierarchy, in Transport Scotland decision making. This involves:

…promoting walking, wheeling, cycling, public transport and shared transport options in preference to single occupancy private car use for the movement of people. We will also promote efficient and sustainable freight transport for the movement of goods, particularly the shift from road to rail.

Transport Scotland published the NTS2 Delivery Plan in December 2020, which highlights action to deliver the six policies set out above 2 . This outlines many collaborative working arrangements with local authorities, transport operators and others aimed at decarbonising cars, buses, rail and freight vehicles and encouraging greater use of public transport, walking and cycling. It also mentions several investment and subsidy schemes, such as a £120m investment over five years to support the deployment of battery-electric and hydrogen buses. However, it also briefly refers to projects that will significantly expand the capacity of the trunk road network, such as the dualling of the A9 between Perth and Inverness and A96 between Inverness and Aberdeen. These projects are predicted to increase greenhouse gas emissions, e.g. as set out in the 3A9 Dualling Case for Investment, and run counter to the recommendation of 4Infrastructure Commission for Scotland that NTS2 and STPR2 should include:

…a presumption in favour of investment to future proof existing road infrastructure and to make it safer, resilient and more reliable rather than increase road capacity.

The delivery of the vision and policies set out in NTS2 is, at a national level, reliant on investment priorities that will be identified in the 5 Strategic Transport Projects Review 2 (STPR2). STPR2 involves an evidence-based review of Scotland’s strategic transport network to identify interventions that will support the delivery of Scotland’s Economic Strategy. The results of the review will be published in two phases:

Phase 1: To be published in winter 2020/21, will set out projects that can be delivered within two to three years and assist in recovery from Covid-19

Phase 2: To be published in Autumn 2021, will set out recommendations for the development of the transport system over the next 20 years.

More generally, many organisations, such as the 6Climate Change Committee and 7 IPCC, have looked at what policy and practical interventions work in stabilising and then reducing transport emissions. While there are many individual policy, budget and fiscal approaches, these can generally be categorised under three broad headings:

Travel demand management - reducing the need to travel, particularly by car

Modal shift from car to walking, cycling and public transport

Decarbonising motorised vehicles – replacing the internal combustion engine with electric and hydrogen fuelled power plants.

Parliamentary, and Other Scrutiny

The Scottish Government’s transport policies and projects are scrutinised by the Parliament’s Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee. This Committee has “mainstreamed” consideration of climate issues – which means it regularly questions witnesses, including Scottish Ministers, on the climate implications of policy and investment decisions.

More specifically, the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee’s recent Green Recovery Inquiry Report 1 made four climate and transport related recommendations, which can be summarised as follows:

The Scottish Government should promote public transport use as part of any green recovery

The Scottish Government should support Scottish public transport vehicle manufacturers

Transport budgets and fiscal incentives should be targeted at reducing demand for travel by car and encouraging walking, cycling and public transport use

The Scottish Governments should support the development of:

comprehensive, uninterrupted networks of safe walking and cycling routes in cities, towns and villages

integrated land-use and transport planning with the aim of creating “20- minute neighbourhoods” where people can access work, leisure and essential services on foot, bike or public transport in no more than 20 minutes.

Draft CCPu - Transport

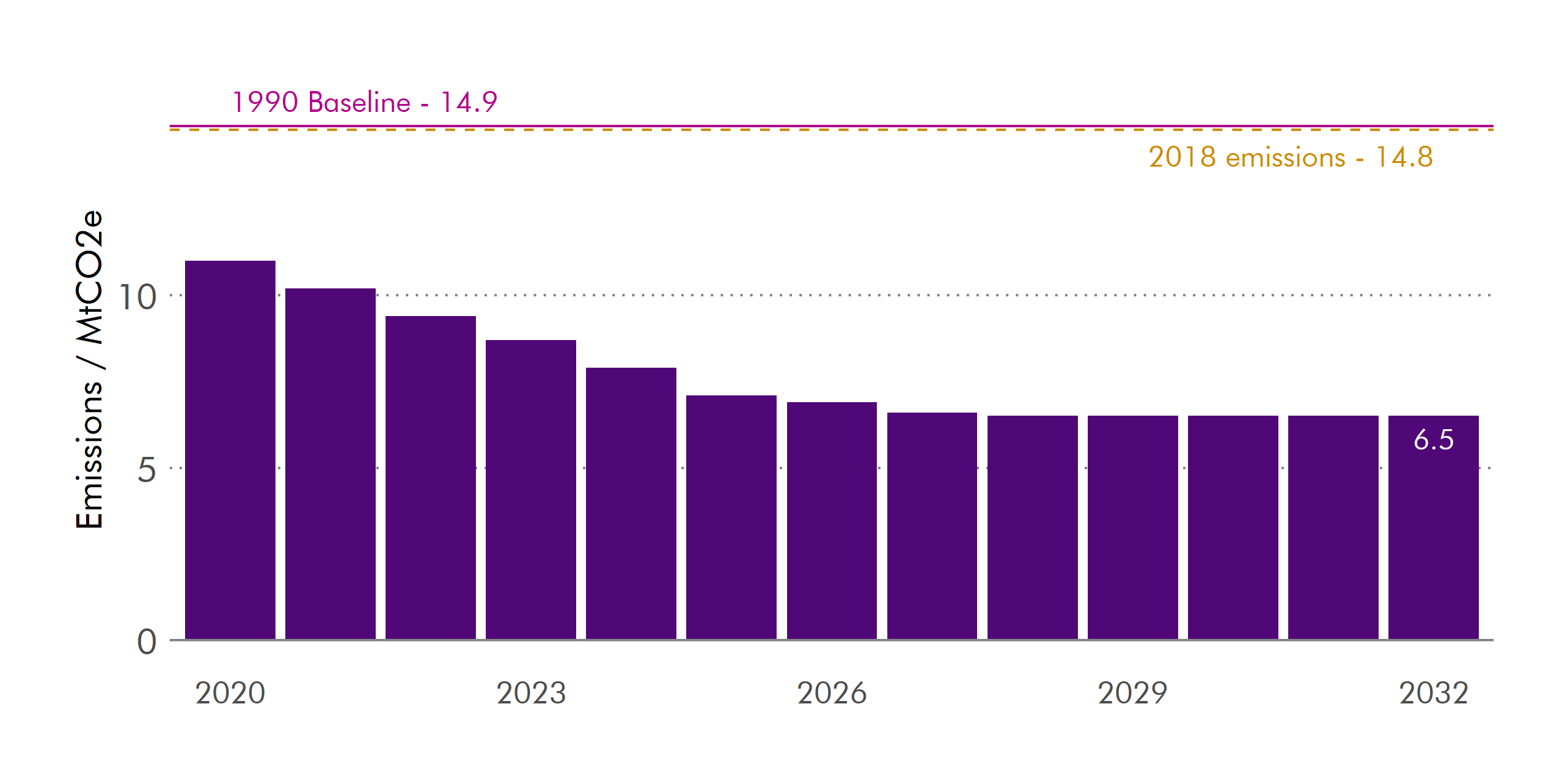

The draft CCPu predicts a 41% fall in transport emissions between 2020 and 2032, from 11 MtCO₂e to 6.5 MtCO₂e, as set out below.

The 2032 target is 2.2 MtCO₂e (25.3%) lower than the 8.7 MtCO₂e target set in the 2018 CCP. It is also worth noting that estimated transport emissions of 11 MtCO₂e in 2020 is 3.8 MtCO₂e (25.7%) less than actual transport emissions in 2018 – which would be an unprecedented reduction in such a short period. While 1 Covid-19 travel restrictions imposed during 2020 have produced a significant temporary reduction in transport emissions, a rebound in emission levels is expected. However, the Scottish Government does not appear to predict any bounce back in emissions following the end of the pandemic, when restrictions on local, national and international travel will be lifted (see above graph).

The transport outcomes, policies and monitoring scheme set out in the draft CCPu are significantly different from those in the 2018 CCP as briefly explained below.

The draft CCPu sets out eight policy outcomes:

| Policy outcome | Change since CCP 2018 | |

| 1 | To address our over reliance on cars, we will reduce car kilometres by 20% by 2030 | New outcome |

| 2 | We will phase out the need for new petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030 | Date brought forward from 2032 |

| 3 | To reduce emissions in the freight sector, we will work with the industry to understand the most efficient methods and remove the need for new petrol and diesel heavy vehicles by 2035. | New outcome |

| 4 | We will work with the newly formed Bus Decarbonisation Taskforce, comprised of leaders from the bus, energy and finance sectors, to ensure that the majority of new buses purchased from 2024 are zero-emission, and to bring this date forward if possible. | Supersedes previous bus decarbonisation outcome |

| 5 | We will work to decarbonise scheduled flights within Scotland by 2040 | New outcome |

| 6 | Proportion of ferries in Scottish Government ownership which are low emission has increased to 30% by 2032. | No change |

| 7 | By 2032 low emission solutions have been widely adopted at Scottish ports | No change |

| 8 | Scotland’s passenger rail services will be decarbonised by 2035. | Supersedes previous rail decarbonisation outcome |

Significant changes in the focus of the policy outcomes set out in the draft CCPu, when compared with those in the 2018 CCP, are briefly highlighted below:

The focus has shifted from reducing average greenhouse gas emissions from new cars in the period up until 2032 to reducing the total distance travelled by car by 20% by 2030. This commitment is considered in more detail in the SPICe Spotlight post – 2 Back to the Future: reducing car travel in Scotland

The target of a 28% reduction in emissions for each tonne-kilometre of road freight carried by 2032 has been replaced by a commitment for the Scottish Government to work with the freight industry to remove the need for new petrol and diesel heavy vehicles by 2035. Heavy Goods Vehicles accounted for 13% of Scottish transport emissions in 2018

The focus on bus decarbonisation has shifted from a target of 50% of all buses being low emission by 2032 to an ambition that most new buses purchased from 2024 will be zero emission. It is worth noting that in 2018/19, the average age of a bus in Scotland was 7.9 years and that buses have an 3estimated useful service life of 11 years. Buses being brought into service today are likely to still be in service into the 2030’s

Aviation is brought within the outcomes for the first time, with a commitment that scheduled flights within Scotland will be decarbonised by 2040. In 2018, just 5% of passengers flew between two Scottish airports. Given that these are relatively short flights, often made using smaller aircraft, they are likely to account for less than 5% of Scottish aviation emissions

The focus on rail has shifted from a target of electrifying 35% of the rail network by 2032 (32.4% of which was electrified as of 2017/18), to complete decarbonisation of passenger rail vehicles by 2035. Details of how this will be achieved are set out in a separate 4 Rail Services Decarbonisation Action Plan, published in July 2020.

The eight policy outcomes are to be delivered through 49 policies and proposals, which can be found on pages 221 to 226 of the draft CCPu. 33 of these policies and proposals are new, with only 16 appearing in the 2018 version of the Plan.

Progress towards meeting the policy outcomes will be measured using nine indicators. However, no interim annual figures marking progress towards the eight policy outcomes are set out in the draft CCPu. Progress is simply defined as either “Year-to-year change” or “Progress towards target”.

Industry

The draft CCPu reminds us that industry – defined here as manufacturing, construction, refining of petroleum products and a range of activities linked to energy supply - is responsible for almost 30% of Scotland's total GHG emissions, second only to transport.

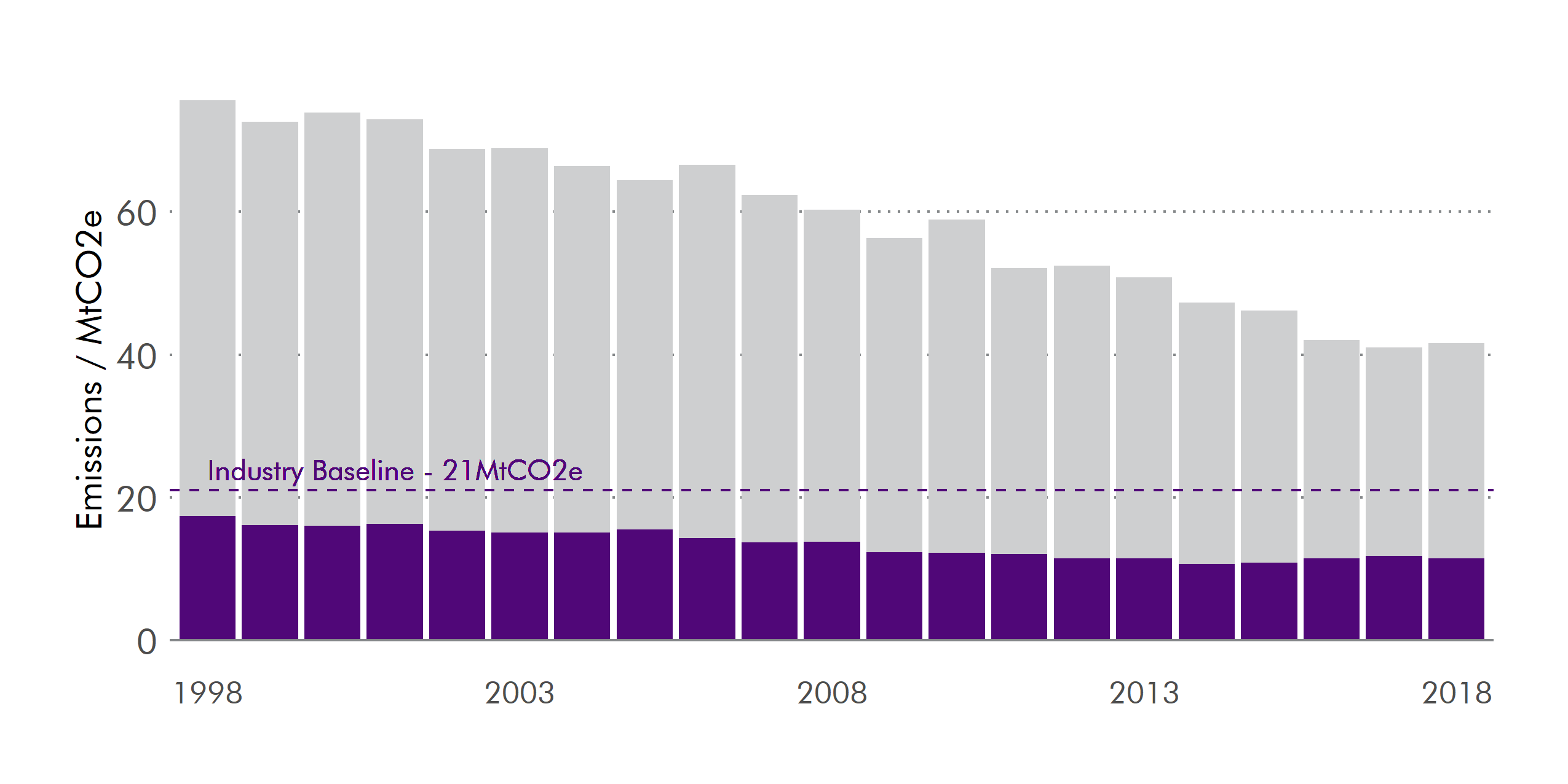

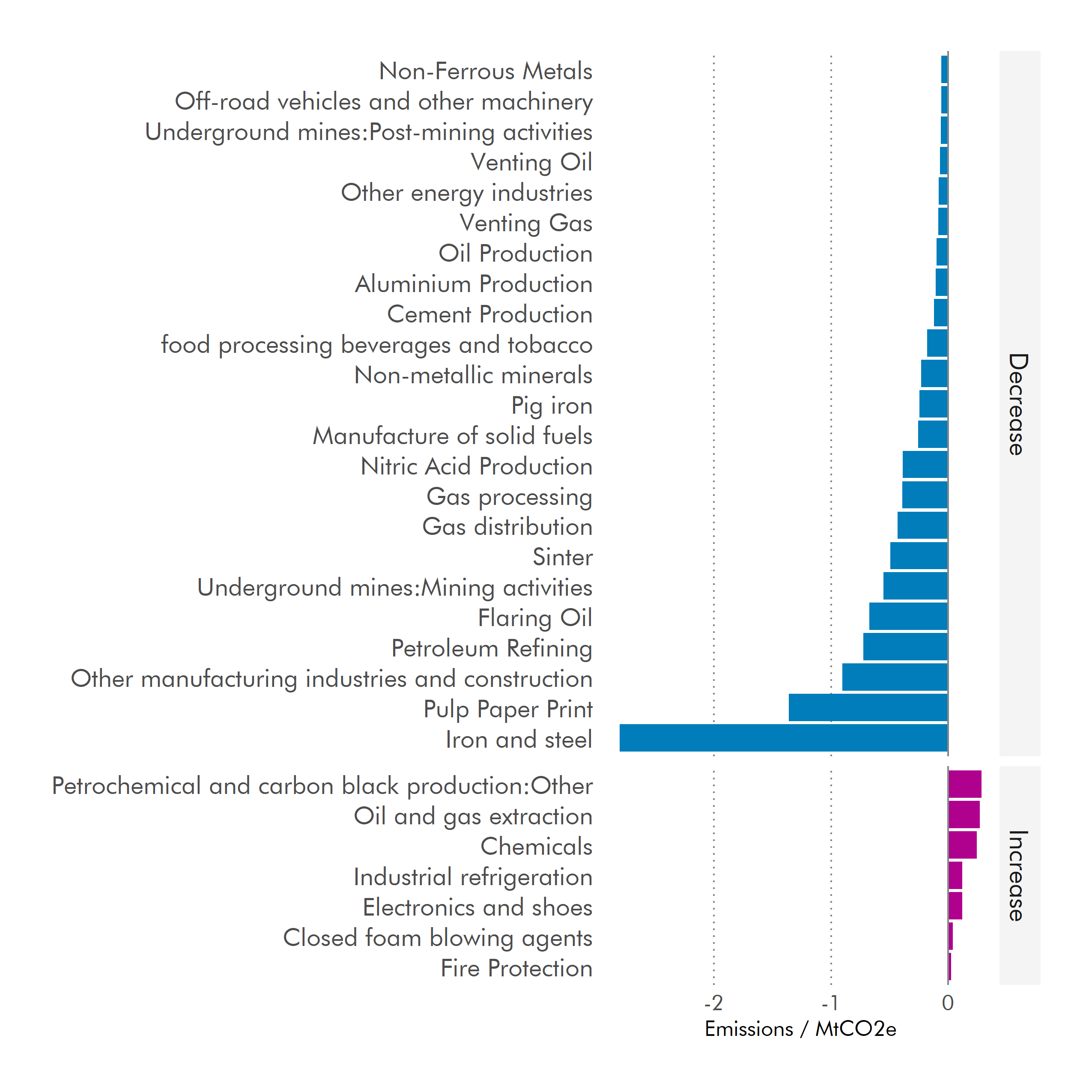

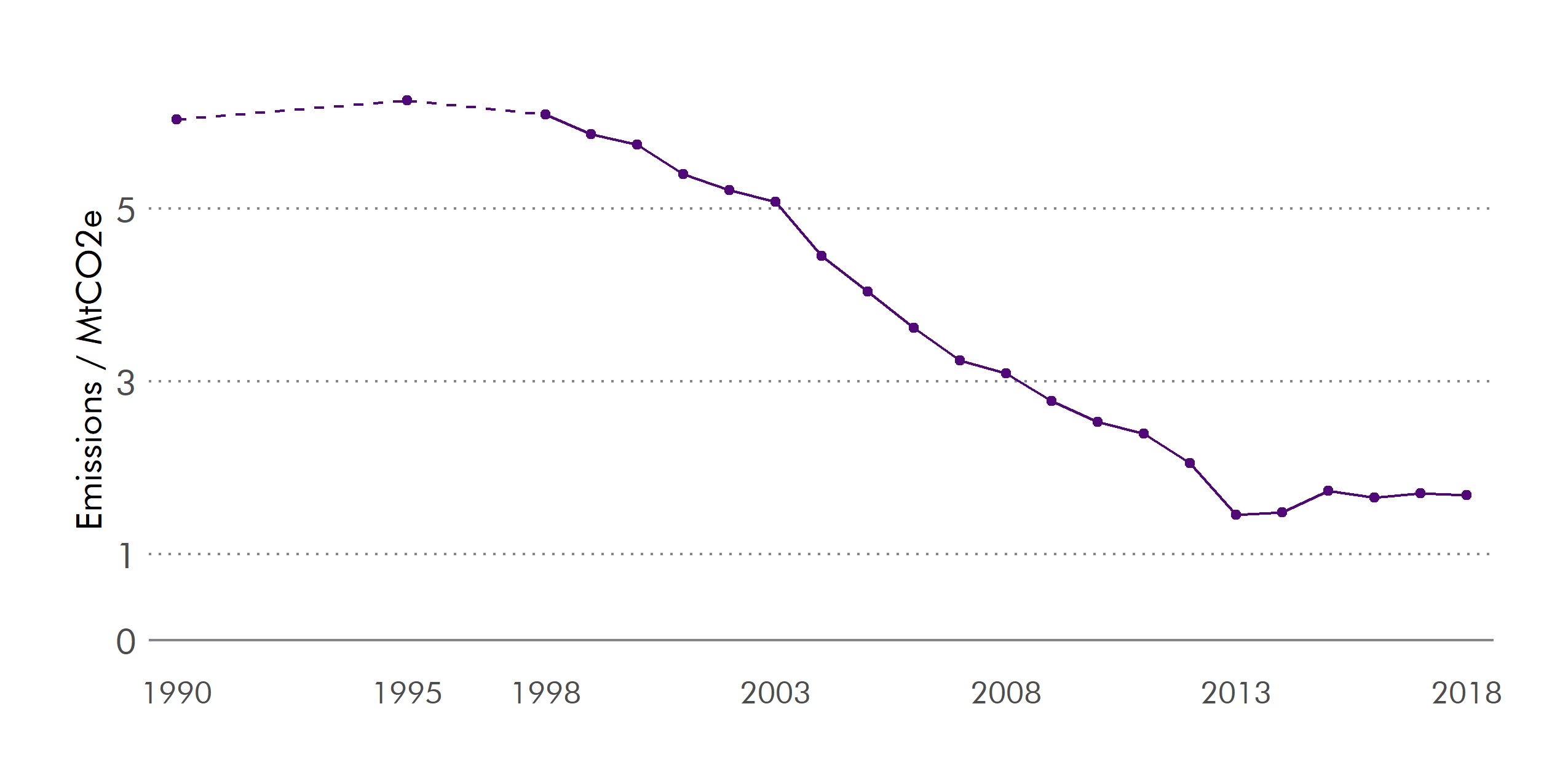

Data published by the Scottish Government earlier this year reveals some interesting trends 1. It shows, for example, emissions from the ‘industry’ sector fell from 21 MtCO₂e in 1990 (the baseline year) to 11.5 MtCO₂e in 2018, a 45% reduction over the past 28 years.

Much of the 9.5 MtCO₂e reduction in industrial emissions over the period can be explained by the total disappearance of some major polluting industries, such as steel, coal mining and paper production. It’s worth remembering that Ravenscraig closed in 1992 and Scottish underground coal mining limped on until 2002.

Given the changes in Scotland’s economy over the period – with the continued demise of heavy industry and the growth of the services sectors – the fact that industry is responsible for the same proportion of total emissions now (27.6%) than in 1990 (27.5%) is perhaps surprising.

Some industrial sectors have actually seen an increase in the amount of GHG emissions over the past 30 years. For example, chemicals, oil extraction (emissions associated with onshore oil and gas terminals; specifically combustion of gas oil and untreated natural gas at these sites), electronics and petrochemical production have all seen significant increases since 1990. Others, such as food and drink production, have seen steady reductions in their emissions, whilst maintaining or even expanding output.

As highlighted by the Committee on Climate Change in 2019, the largest single geographical source of emissions in Scotland is the cluster of industry in and around Grangemouth, which accounted for over 30% of industrial emissions in Scotland (3.6 MtCO₂ in 2017) 2. We also know that natural gas combustion is the biggest source of industrial emissions, followed by the use of internal fuels (i.e. industry by-products generally burned on-site and with limited or no alternative use) within the oil and gas and petrochemical industries 3.

Table 4 shows the largest GHG emitting sectors in 2018. Unsurprisingly, petrol refining, oil and gas extraction (onshore operations) and chemicals are amongst the most carbon-intensive sectors. Food and drink, despite significant reductions since 1990 is also one of the highest emitting industrial sectors in Scotland.

| Sector | Million tonne CO₂ equivalent (2018) | % of total industrial emissions |

| Petroleum Refining | 2.1 | 18% |

| Other industrial combustion (more info) | 2.1 | 18% |

| Oil and gas extraction (onshore operations) | 1.6 | 13% |

| Petrochemicals | 1.5 | 13% |

| Chemicals | 1.1 | 9% |

| Off-road vehicles and other machinery | 0.5 | 4% |

| Food and drink | 0.5 | 4% |

| Cement_Production | 0.4 | 3% |

| Flaring Oil | 0.3 | 3% |

Context

The draft CCP update aims for a 43% reduction in industrial emissions between 2018 and 2032 (52% if NETSi are included) . This is considerably more ambitious than the 21% reduction set out in the 2018 Climate Change Plan.

As noted in the section on Deriving Sector Emissions Envelopes, the envelope set out below has been constrained so that it remains consistent with allowed emissions set by international carbon markets. Assumed emissions in 2020 are the same as actual emissions in 2018.

The 2020 draft CCPu highlights research commissioned by the Government showing that emissions from Scotland’s large industrial sites "could feasibly reduce by 80% or more by 2045, while maintaining output". There are various ways emissions from Scotland’s industrial sectors could be cut over the next 25 years, for example by improving energy efficiency, replacing fossil fuels with hydrogen, electricity or bioenergy (collectively termed ‘fuel switching’) and implementing carbon capture, utilisation, and storage (CCUS).

Recent Reports - Industry

The Committee on Climate Change’s Progress Report to Parliament, published in October 2020, reminds us that “responsibility for policy design and implementation falls mainly under the UK government” 1. Nevertheless, economic development, planning and environment are devolved policy areas, and the Scottish Government has an important role to play in supporting/encouraging industry to cut its GHG emissions.

There is also scope for the Scottish Government to work in partnership with other governments, influencing the course and ambitions of UK-wide efforts. For example, the CCC calls on the Scottish Government to work closely with the UK Government, Welsh Government and Northern Ireland Executive on developing a UK Emissions Trading System that is aligned to Net Zero. This was a recommendation strongly supported by the Scottish Parliament’s Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee in its Green Recovery Inquiry report 2.

Recognising the importance of Scotland’s skills and education systems - entirely devolved policy areas - the CCC recommends the Scottish Government 1:

Develop a strategy for a net-zero workforce that ensures a ‘just transition’ for workers transitioning from high-carbon to low-carbon and climate resilient jobs, integrates relevant skills into the UK's education framework and actively monitors the risks and opportunities arising from the transition.

The Scottish Government, and its agency Skills Development Scotland (SDS), responded with their Climate Emergency Skills Action Plan 2020-2025 4, published alongside the draft CCPu. Introducing the Plan, Cabinet Secretary for Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform highlighted the employment opportunities presented by a green recovery:

“Enhancing access to skills training is critical for successful decarbonisation and will help create new, high-quality green jobs, enhanced regional growth, and improved access to growing ‘green markets’ across the globe for Scotland’s diverse businesses.”

Defining what is meant by “green jobs”, the Plan includes jobs 4:

…in renewable energy, the circular economy and zero waste, and the nature based sector with wider ‘green skills’ sitting on a spectrum ranging from highly specific requirements in sectors directly supporting the transition to net zero such as energy, transport, construction, agriculture, and manufacturing, through to more generic requirements across all sectors to thrive in a net zero economy.

Scotland’s skills system has an important role to play in ensuring people of all ages have the skills required to benefit from the green transition opportunities. The Plan includes a number of new or updated policies aimed at developing the future workforce for the transition to net zero. These include:

Establishing a Green Jobs Workforce Academy in September 2021

The co-design and development of a Construction Retrofit national training programme

Supporting the development of leadership and management skills required for a net zero future

Access to these green jobs will be supported by recovery skills programmes including the National Transition Training Fund, Young Person’s Guarantee, Fair Start Scotland and No One Left Behind

Aligning education and training opportunities in schools, colleges and universities to net-zero opportunities and maximising their uptake.

Potential for Hydrogen and Carbon Capture

The draft CCPu sets great store in the potential of hydrogen energy, negative emissions technologies and carbon capture and storage to help Scotland meet its industrial emissions targets. However, despite there being much talk about these technologies over a number of years there has been very little in the way of significant roll-out anywhere in the UK.

Citing research by Strathclyde University's Centre for Energy Policy, the draft CCPu quotes an estimate of between 7,000 and 45,000 UK jobs potentially being associated with carbon storage by 2030. The CEP report does not specify how many of these will be in Scotland. The Government informs us that they have commissioned further research specific to Scotland "which will consider the associated jobs within a broad range of scenarios for the development of CCUS" 1.

The Centre for Energy Policy believes Scotland is uniquely placed to take advantage of the opportunities presented by CCUS 1:

...with world class offshore geological sites with large CO₂ storage potential in the Scottish continental shelf and the presence of existing skills, knowledge, capacity and infrastructure to deliver CO₂ transport and storage services...It would utilise existing onshore and offshore energy supply industry, pipeline infrastructure and associated extensive supply chain links, and provide attractive upskilling and reskilling opportunities for existing workers in the sector and appealing career prospects in a low carbon industry context for the next generation.

In addition to CCUS, the Scottish Government sees great opportunity in developing a hydrogen energy industry in Scotland. In its Hydrogen Policy Statement published in December 2020 the Government cites research estimating the hydrogen industry has the potential to be worth £25 billion a year to the Scottish economy with between 70,000 to 300,000 jobs "protected or created" by 2045 3.

Focussing on the role of hydrogen in industrial processes, the Scottish Government sees hydrogen combustion as a way of creating high temperatures without the direct emission of greenhouse gases (it is worth remembering that heating processes account for 74% of all industrial emission). In its policy statement, the Government believes hydrogen could replace natural gas for those industrial users connected to the gas network 3. Of course, hydrogen is already used extensively in certain industries - for example in oil refining, chemicals and cement production - and it is often the case that the current production of hydrogen is relatively carbon-intensive with high levels of CO₂ emissions.

The draft CCPu points to greener ways of hydrogen production, with the Acorn hydrogen project in St Fergus presented as a potential model which could "reform North Sea natural gas into clean-burning hydrogen". This will be possible using carbon capture technology; CO₂ emitted during the process of converting gas to hydrogen will be captured and then stored in depleted North Sea gas fields via the CCUS development also being developed at St Fergus. The draft CCPu case study states that the Acorn Hydrogen project will be operational in 2025, "creating a low carbon fuel which presents various market opportunities" 5.

Decarbonisation of Existing Industries

The Scottish Government outlines that there are four main ways in which to decarbonise industrial processes: through electrification, energy efficiency, CCUS and hydrogen1. It is known that decarbonising some industrial processes will be difficult, especially when they require intense heat or when a particular hydrocarbon feedstock is used in a chemical process. Nevertheless, research commissioned by the Scottish Government and published last month states that emissions from Scotland's most carbon-intensive industries can be reduced by over 80% by 2045 2.

Depending on the industry, decarbonisation could be achieved through a combination of three "abatement contributions"; CCUS, fuel-switching (to electricity or hydrogen) and energy efficiency. For example, it is anticipated that 60% of CO₂ reductions in food and drink will come from fuel-switching, whilst almost 80% of the reductions relating to cement production will come from carbon capture. Unsurprisingly, the largest reductions will be seen in the oil and gas and chemicals industries where all three will have some role to play.

It is worth noting that this research, produced by Element Energy for the Scottish Government, had inputs from some major Scottish industrial players, including Ineos Chemicals, Petroineos and the Scotch Whisky Association 2. Researchers were told by industry that policy support is"critical" for establishing a business case for investment in decarbonisation. Furthermore 2:

Without policy intervention there is a risk that a strongly increasing carbon price could affect industrial competitiveness and induce certain industrial sites to shut down. In some cases, industrial sites may relocate to regions with a lower carbon price, which would not result in any carbon abatement.

Draft CCPu - Industry

In its draft CCPu, the Government sets out a range of policies and proposals they believe will lead to the following two outcomes:

Outcome 1: Scotland’s Industrial sector will be on a managed pathway to decarbonisation, whilst remaining highly competitive and on a sustainable growth trajectory.

And

Outcome 2: Technologies critical to further industrial emissions reduction (such as carbon capture and storage and production and injection of hydrogen into the gas grid) are operating at commercial scale by 2030.

The following table sets out the policies the Scottish Government list under each outcome with some additional information provided about funding/partners and when the policy was first announced.

| Outcome 1 – pathway to decarbonisation | ||

| Policy | Details and funding (if relevant) | When announced? |

| Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) | UK Government and devolved administrations | Announced in June 2020– ‘boosting’ 2018 Plan |

| Energy Transition Fund (ETF) – for the North East | £62 million funding package available to support Net Zero projects | New – First announced in June 2020 |

| Scottish Industrial Energy Transformation Fund (SIETF) | £34 million match-funding for capital projects over next 5 years, supporting decarbonisation of industrial and manufacturing sectors | First announced in Programme for Government 2020/21 |

| Low Carbon Manufacturing Challenge Fund (LCMF) | £26 million support to a broader group of manufacturers and their supply chains. Policy still being developed | First announced in Programme for Government 2020/21 |

| Making Scotland’s Future – a recovery plan for manufacturing | Plan developed by the Scottish Government, enterprise and skills agencies, industry partners, trades unions and academics – currently out for consultation | New –consultation announced on 4th December |

| Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) | A GB-wide scheme created by the UK Government (with the agreement of the Scottish Government). UK Government is extending scheme to 2022 | Changes announced by UK Gov in August 2020– ‘boosting’ 2018 CCP |

| Proposals | ||

| Scottish Industrial Decarbonisation Partnership (SIDP) | Scottish Government - stakeholder forum with representatives from manufacturing sites | New – announced in the 2020 draft CCP update |

| Net Zero Transition Managers Programme | To be launched in 2021. The SG hopes to facilitate new managerial roles into energy intensive industries, tasked with recommending decarbonisation options | New – announced in the 2020 draft CCP update |

| Grangemouth Future Industry Board (GFIB) | Scottish Government, Falkirk Council and Scottish Enterprise, engaging with businesses. Launched in 2020 to co-ordinate support aimed at decarbonisation and growth | First announced in Programme for Government 2020/21 |