UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill - Part 2 -Environmental Principles and Governance

The UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill was introduced on 18 June 2020 by Michael Russell MSP the Cabinet Secretary for the Constitution, Europe and External Affairs. The Bill provides that Scots law can continue to align with EU law after 31 December 2020; introduces guiding principles on the environment into Scots law; requires that Ministers and public bodies have regard to those environmental principles when making policy; and creates a new body to enforce compliance by Scottish Ministers and public authorities with environmental law.

Executive Summary

The Scottish Government introduced the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill on 18 June 20201. The Scottish Government had previously delayed the introduction of the Bill because of the COVID-19 public health emergency.

Part 1 of the Bill provides for the introduction of a power to enable Scottish Ministers to continue to keep devolved law aligned with EU law following the end of the implementation period (31 December 2020). A SPICe Briefing on the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill: Parts 1 and 3 is available2.

Much Scottish environmental law is derived from EU law and standards, and as the UK leaves the jurisdiction of EU institutions, it is necessary to replicate some of their functions through domestic arrangements. As environment is a devolved matter, the Scottish Government has brought forward such proposals. Arrangements elsewhere in the UK are also under development, including through the UK Environment Bill.

Part 2 of the Scottish Bill provides for:

the introduction of guiding environmental principles into Scots law, and

the formation of Environmental Standards Scotland, and its functions and powers.

EU environmental law is underpinned by a number of principles, drawn from the European treaties, and the bill provides for these to be introduced explicitly into Scots law. This briefing covers the principles themselves, who they are to apply to, and how they are to be taken account of. It considers some exclusions to be applied to when the principles need to be taken into account, and how guidance around the principles is to be constructed.

The Bill provides for the creation of a new public body, Environmental Standards Scotland (ESS). This briefing explores the functions, powers and scope of ESS, as well as its jurisdiction in regard to the environment, and environmental law. It also considers interaction with environmental governance measures in the rest of the UK.

SPICe has produced briefings on Environmental Governance in Scotland after EU Exit and the UK Environment Bill, as well as a set of Frequently Asked Questions on Brexit. The sections on EU law and institutions may be helpful background reading.

Part 2: Environmental principles and governance

Part 2 of the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill relates to environmental principles and governance post-EU exit. This is important as much Scottish environmental law is derived from EU law and standards. In January 2020 SPICe published a briefing on Environmental Governance in Scotland after EU Exit. This outlined that:

EU exit will affect the mechanics of environmental law-making and enforcement in Scotland, as well as in the rest of the UK. Since the 2016 EU referendum, environmental matters have therefore been at the centre of an ongoing flurry of preparatory activities on both sides of the Scotland-England border. These activities have focused on a set of cross-cutting questions, namely:

Savaresi, A. (2020, January 9). Environmental Governance in Scotland after EU Exit, SB 20-02. Retrieved from https://digitalpublications.parliament.scot/ResearchBriefings/Report/2020/1/9/Environmental-Governance-in-Scotland-after-EU-Exit [accessed 6 July 2020]

Whether and how to ensure the UK’s future alignment with EU environmental standards;

Whether and how to replace extant environmental governance arrangements that presently depend on EU institutions – such as emissions trading and chemicals regulation;

Whether and how to replace the EU’s review and enforcement powers over public authorities in the UK;

Whether and how to maintain the role of EU environmental law principles in future policy making across the UK;

How to allocate law-making and enforcement powers presently exercised by the EU between UK and devolved administrations after exit.

Development of the proposals

Following the 2016 EU referendum, the Scottish Government established a roundtable of experts to provide advice on the impact of Brexit on the environment and climate change.1 The roundtable reported in June 20182.

The Scottish Government conducted a consultation on environmental principles and governance in early 2019.3

The recently published 'Environment Strategy for Scotland: vision and outcomes' (published 25 February 2020) reiterates the Scottish Government's commitment to maintain or exceed existing environmental standards in light of EU Exit:

In working to achieve our vision, we will be a committed, international partner: collaborating with other countries and seeking to play our role in European and global forums, including by continuing to contribute to EU environmental policy goals and action. We are determined to retain the benefits we have enjoyed through membership of the EU in our approach to environmental protection. We will seek to maintain or exceed EU environmental standards.

The Scottish Government. (2020, February). The Environment Strategy for Scotland: Vision and Outcomes. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2020/02/environment-strategy-scotland-vision-outcomes/documents/environment-strategy-scotland-vision-outcomes/environment-strategy-scotland-vision-outcomes/govscot%3Adocument/environment-strategy-scotland-vision-outcomes.pdf [accessed 4 August 2020]

Protecting Scotland's Future: the Government's Programme for Scotland 2019-2020 stated:

[..] EU exit must not impede our ability to maintain high environmental standards. We will develop proposals to ensure that we maintain the role of environmental principles and effective and proportionate environmental governance and any legislative measures required will be taken forward in the Continuity Bill.

The Scottish Government. (2019, September 3). Protecting Scotland's Future: the Government's Programme for Scotland 2019-2020. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/protecting-scotlands-future-governments-programme-scotland-2019-20/ [accessed 4 August 2020]

Environmental principles

Part 2, Chapter 1 of the Bill contains proposals to bring principles equivalent to the EU environmental principles into Scots law.

As outlined in Savaresi (2020):

Environmental law is underpinned by a set of principles, which may be defined as policy statements “concerning how environmental protection and sustainable development ought to be pursued”. These principles are not only found in EU law, but also feature in a host of national and international environmental law instruments all over the world. Environmental principles concern typically:

Savaresi, A. (2020, January 9). Environmental Governance in Scotland after EU Exit, SB 20-02. Retrieved from https://digitalpublications.parliament.scot/ResearchBriefings/Report/2020/1/9/Environmental-Governance-in-Scotland-after-EU-Exit [accessed 6 July 2020]

how the law is made (for example, through public consultation and participation),

how it is enforced (for example, by guaranteeing access to justice to certain groups or interests), and

its substantive content (for example, when they are incorporated into legislative instruments or into the design of regulatory structures and processes).

Savaresi (2020) sets out that:

EU environmental law hinges on four core principles which originated in Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development legal instruments, and which feature in a host of EU instruments and policy documents. According to Article 191.2 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (emphasis added): "Union policy on the environment shall aim at a high level of protection taking into account the diversity of situations in the various regions of the Union. It shall be based on the precautionary principle and on the principles that preventive action should be taken, that environmental damage should as a priority be rectified at source and that the polluter should pay.”

Savaresi, A. (2020, January 9). Environmental Governance in Scotland after EU Exit, SB 20-02. Retrieved from https://digitalpublications.parliament.scot/ResearchBriefings/Report/2020/1/9/Environmental-Governance-in-Scotland-after-EU-Exit [accessed 6 July 2020]

And:

Another two principles that are not included in Article 191.2 TFEU are commonly listed as part of EU environmental law, namely: the integration principle i.e. that environmental protection requirements should be integrated into other policy areas; and the principle of sustainable development i.e. that of ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ 16 . These principles are binding on the EU legislature and on Member States when they implement EU law. EU environmental law principles, therefore, do not have practical legal force in and of themselves. Their incorrect application and interpretation can nonetheless be challenged before the EU’s and Member States’ national courts.

Savaresi, A. (2020, January 9). Environmental Governance in Scotland after EU Exit, SB 20-02. Retrieved from https://digitalpublications.parliament.scot/ResearchBriefings/Report/2020/1/9/Environmental-Governance-in-Scotland-after-EU-Exit [accessed 6 July 2020]

Consultation & development of the principles proposals

The Scottish Government consultation on environmental governance and principles in early 2019 included specific proposals on principles. The consultation included that:

EU environmental principles have to be read and implemented in the context of wider principles of EU law, including the fundamental rights of individuals, proportionality and legal certainty. For example, the principle of proportionality is important in interpreting how the environmental principles interact with economic and social objectives.

The development of EU environmental policy and legislation is also informed by principles in international conventions and agreements, such as the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. These principles are also reflected in law and policy developed in Scotland.

The Scottish Government. (2019). Consultation on Environmental Principles and Governance in Scotland. Retrieved from https://consult.gov.scot/environment-forestry/environmental-principles-and-governance/ [accessed 4 August 2020]

The consultation also included a useful (non-exhaustive) list of some of these international conventions and agreements, including:

The UN Rio Declaration on Environment and Development 1992

The UN Convention on Biological Diversity 1992

The UN Aarhus Convention 1998

The Paris Agreement on climate change 2015 (which ingrains the principle of non-regression)

One hundred responses to the consultation were published2.

The establishment of environmental principles in Scots law (sections 9-14)

The Bill contains proposals to bring principles equivalent to the EU environmental principles into Scots law. The Policy Memorandum states that the purpose is to "promote a high level of environmental protection and sustainable development in Scotland".

Section 9 - The guiding principles on the environment

Section 9 of the Bill sets out that the guiding principles on the environment are references to:

a) the precautionary principle as it relates to the environment,

b) the principle that preventative action should be taken to avert environmental damage,

c) the principle that environmental damage should as a priority be rectified at source,

d) the principle that the polluter should pay.

The Explanatory Notes give some further detail on these principles:

Scottish Government. (2020, June 18). UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill Explanatory Notes:. Retrieved from https://beta.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/current-bills/uk-withdrawal-from-the-european-union-continuity-scotland-bill-2020/introduced/explanatory-notes-uk-withdrawal-from-the-european-union-continuity-scotland-bill.pdf [accessed 25 July 2020]

Precautionary principle. Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.

Prevention principle. Preventative action should be taken to avoid environmental damage.

Rectification at Source principle. Environmental damage should, as a priority, be rectified at source.

Polluter Pays principle. The polluter should bear the cost of pollution control and remediation.

The Bill recognises (section 9(2)) that these principles are derived "from the equivalent principles provided for in Article 191(2) of Title XX of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union."

The Policy Memorandum states:

Ministers may only remove, define or amend a guiding principle to reflect the removal of, or amendment to, the equivalent principles in EU law.

The Scottish Governemnt. (2020, June 18). UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill Policy Memorandum. Retrieved from https://beta.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/current-bills/uk-withdrawal-from-the-european-union-continuity-scotland-bill-2020/introduced/policy-memorandum-uk-withdrawal-from-the-european-union-continuity-scotland-bill.pdf [accessed 21 June 2020]

This section also:

Requires Scottish Ministers to "have regard to the interpretation of those equivalent principles by the European Court from time to time"when preparing its guidance on the interpretation of the principles in the Bill (section 9(3)).

Empowers Scottish Ministers to, by regulations under the affirmative procedure, add, remove or amend the environmental principles or further define them - but can only do this where necessary to reflect the removal of or amendment of the equivalent principles in accordance with EU law or to reflect how the equivalent principle has effect in EU law (section 9 (4) (5) and (6));

Requires Scottish Ministers before laying a draft of such Regulations to consult with a Minister of the Crown, public bodies that are subject to the duty to have regard to the principles, and persons considered to be representative of various specified interests, including industry and local government.

A 'Minister of the Crown' is as defined in the Ministers of the Crown Act 1975, and means Ministers of the UK Government. More explanation on the inclusion of Ministers of the Crown is included under the briefing text on Section 10.

Section 10 - Ministers' duties to have regard to the guiding principles

Section 10 requires Scottish Ministers to "have regard to" the guiding principles on the environment when developing policies, including proposals for legislation (section 10(1)). According to the Explanatory Notes this is for:

the purpose of contributing to the protection and improvement of the environment and sustainable development.

The Policy Memorandum states:

By placing a duty on Ministers and a further duty on public authorities, the provisions in the Bill seek to ensure a continued role for domestic environmental principles informed by the four EU environmental principles following EU Exit, through ensuring that they continue to inform the development of law and policy in Scotland.

The Policy Memorandum further states that, during the consultation on these proposals:

Concern was raised regarding the framing of the duty 'to have regard to' with stronger alternatives suggested by a number of respondents.

Section 10 also places the same duty on Ministers of the Crown when creating policies and proposals for legislation as far as they extend to Scotland. The Explanatory Notes state:

A Minister of the Crown would be required to consider the guiding environmental principles or to have them in view when developing policy for Scotland. The Scottish Parliament has competence to impose a requirement on both the Scottish Ministers and Ministers of the Crown to have regard to the guiding environmental principles as the conferral has a devolved purpose, environmental protection, and related effect.

Exclusions apply in relation to any policy or proposal so far as it relates to "national defence or civil emergency", or "finance or budgets".

No further information is given in the accompanying documents to explain why these exemptions apply - though they are similar to exemptions in the Environmental Assessment (Scotland) Act 2005, legislation which established the model for Strategic Environmental Assessment, which:

is a means to judge the likely impact of a public plan on the environment and to seek ways to minimise that effect, if it is likely to be significant. Strategic Environmental Assessment therefore aims to offer greater protection to the environment by ensuring public bodies and those organisations preparing plans of a ‘public character’ consider and address the likely significant environmental effects.

The Scottish Government. (2013). Strategic Environmental Assessment - Guidance. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/strategic-environmental-assessment-guidance/ [accessed 17 July 2020]

According to the Explanatory Notes:

The duty, when read with section 12, will apply to policy development, including proposals for legislation, with the purpose of contributing to the protection and improvement of the environment and sustainable development.

and:

the duty placed on the Scottish Ministers and Ministers of the Crown by section 10 applies to developing policy, which is wider than the circumstances to which the duty under section 1 of the 2005 Act applies.

The Policy Memorandum indicates that environmental reports, already required under the Environmental Assessment (Scotland) Act 2005, will be the mechanism for public authorities other than the Scottish Ministers and Ministers of the Crown to demonstrate adherence to the principles. Whilst neither the bill or accompanying documents contain such a defined mechanism for Scottish Ministers or Ministers of the Crown to also do so, their proposals will also be subject to Strategic Environmental Assessment under the 2005 Act.

Section 11 - Other authorities' duty to have regard to the guiding principles

Section 11 extends the duty to have regard to the guiding principles to a 'responsible authority' - as defined in section 2 of the Environmental Assessment (Scotland) Act 2005, the Explanatory Notes to which state that the definition in section 2:

seeks to capture the full extent of the public sector from central and local government, across the range of public bodies and to those private persons or bodies which perform functions of a public character. This might apply to a private body operating under licence or in accordance with statutory powers. The Responsible Authority is in charge of the qualifying plan or programme and each qualifying plan or programme may only have one Responsible Authority at any one time. Where several authorities have an interest in a particular plan or programme they should agree amongst themselves who should be nominated as the Responsible Authority for that plan or programme. Where agreement cannot be reached, the Scottish Ministers will decide who should be the Responsible Authority.

Environmental Assessment (Scotland) Act 2005 - Explanatory Notes. (n.d.) Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2005/15/notes/contents [accessed 4 August 2020]

The duty is therefore to apply when the responsible authority does anything which would require a strategic environmental assessment under section 1 of the Environmental Assessment (Scotland) Act 2005. The 2005 Act requires publication of environmental reports. While not stated in the bill, it is proposed that public bodies can demonstrate they are adhering to the duty through these reports. The Policy Memorandum to the bill states:

Matters in relation to which public authorities are to have regard to the four principles are equivalent to the plans and programmes for which an authority is required to undertake environmental assessment under the Environmental Assessment (Scotland) Act 2005. The environmental report will provide a means by which public authorities can demonstrate that they have fulfilled their duty to have regard to the four principles (other means may be developed or used if appropriate). Including relevant information on the four principles within the report can be addressed as part of existing requirements within the Environmental Assessment (Scotland) Act 2005.

Section 11 excludes Scottish Ministers and Ministers of the Crown, as they are covered under section 10 insofar as development of policy or proposals for legislation is concerned.

Section 12 - Purpose of the duties under sections 10 and 11

Section 12 sets out that those acting under section 10 and 11 must apply the duty with a view to "protecting and improving the environment", and "contributing to sustainable development" (section 12 (1)). It is worth noting that section 44 of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 also includes requirements for public bodies to act sustainably.

Section 12 (2) defines "the environment"for the purposes of section 12 (1) as:

all, or any, of the air, water and land (including the earth’s crust), and “air” includes the air within buildings and the air within other natural or man-made structures above or below ground.

Sustainable development is not defined in the bill, however the Scottish Government's National Performance Framework1 contains National Outcomes which:

are aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

The Sustainable Development Goals2 are the global blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all, and are:

As with all Scottish bills, the Policy Memorandum must include a statement on sustainable development, which for this bill includes that:

The Scottish Government is satisfied that the Bill will have no negative impact on sustainable development.

Section 13 - Guidance

Section 13 requires Scottish Ministers to publish guidance on the guiding principles on the environment and on the duties in sections 10 and 11 as read with section 12.

The guidance may, in particular, include provision about interpretation of the principles, how the principles relate to each other and how the duties relate to other duties, as well as on complying with the duties, and demonstration of compliance. A person who is subject to the duties in sections 10 and 11 must have regard to this guidance, and Scottish Ministers must review the guidance "from time to time".

The Policy Memorandum states:

The guidance, as set out in the Bill, will provide appropriate material on interpretation and scope of the principles, as well as their interactions with each other. It will also clearly set out how Ministers and other public bodies can demonstrate their compliance with the duty and is expected to provide advice and case studies for policy makers. It will set out advice that compliance with the duty in individual decision-making processes is considered and reported alongside the environmental assessment process.

The Explanatory Notes state that the guidance will:

set out how the Scottish Ministers and other public bodies can demonstrate their consideration of the guiding principles through the Environmental Assessment process

The requirements to have regard to the principles extend, for Scottish Ministers and Ministers of the Crown, beyond that set out in the Environmental Assessment (Scotland) Act 2005 i.e. to policy development and proposals for legislation, which are not covered by the 2005 Act, which requires environmental assessments on relevant plans and programmes. This may mean another mechanism may be necessary for demonstration of adherence to the principles for policy development and proposals for legislation.

Section 14 -Procedure for publication of guidance

Section 14 sets out that the Scottish Government must consult a Minister of the Crown, the responsible authorities as defined under section 11, and others they consider appropriate about the guidance before laying the guidance before the Scottish Parliament (section 14 (3)). As the bill is currently drafted, this list does not prescribe Environmental Standards Scotland as a consultee, however they may fall within the category of such other persons that the Scottish Ministers considers it appropriate to consult (section 14(3)(c)).

The guidance must be laid before the Scottish Parliament for a period of 40 days before it can come into effect, and must be accompanied by a statement detailing consultation processes, views heard through the consultation and whether those views were taken into account (section 14 (1)(4)). The 40 day period does not include recesses longer than 4 days, or when Parliament is dissolved).

The result is:

The guidance takes effect at the point when the Scottish Ministers officially publish it.

The earliest this can happen is 40 counting days after the guidance was laid before the Parliament.

During those 40 days, the Parliament can vote against the guidance, in which case it cannot be published. There is no requirement for the Parliament actively to vote to approve the guidance, so as long as the 40 days pass without a negative vote, the Scottish Ministers can go ahead and publish it.

Stakeholder views and discussion

There was broad agreement in the responses to the Scottish Government consultation on environmental governance and principles, that the EU principles should remain at the core of environmental policy and legislation in Scotland. There were some important nuances however. These cannot all be reflected in a briefing of this nature, but some selected quotations are given below.

Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) stated:

We agree. The four principles set out in the consultation have guided European legislation and helped it achieve the impact that it has sustained across Europe. The Scottish Government is committed to maintain or exceed EU environmental standards. It is therefore logical to legislate for a duty to have regard for these principles in the formation of policy, including proposals for legislation. We think may be helpful to contrast the proposed duty with that which already exists for public bodies with regard to Biodiversity, set out in section 1 of the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004). In the case of the latter, it is the duty of public bodies exercising any functions, “to further the conservation of biodiversity, so far as is consistent with the proper exercise of those functions”. The section then sets out a requirement to have regard to the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy and the United Nations Environmental Programme Convention on Biological Diversity. In contrast the proposed legislation appears to be likely to create a duty to apply the four underlying principles but currently lacks a linked, explicit, underlying purpose to which they relate. We wonder if whether the legislation might be clearer and the applications of the principles easier, if there was a linked-purpose statement.

Oil and Gas UK stated:

We support the introduction of a duty to have regard to the four EU environmental principles following an exit from the EU. It is essential that environmental policy and legislation is designed to deliver environmental benefit, and scrutiny of such policy and legislation against defined environmental principles can help ensure this is the case.

Scottish Power stated:

We welcome the Scottish Government's commitment to ensure the four EU 'Environmental principles' continue to sit at the heart of environmental policy and legislation in Scotland, even after exit from the EU. We therefore support the proposal to place a duty on Scottish Ministers to have regard to the four Environmental Principles in development of policies and legislation that may have associated environmental impacts. We would add that the commitment to safeguard or enhance environmental standards in comparison with the European Union, should also be part of that duty, to ensure environmental protection in Scotland does not suffer as a result of the UK's departure from the EU.

Prof Colin T Reid, Professor of Environmental Law at the University of Dundee, went further, stating:

The formal recognition of the principles is welcomed. Regard for the principles should, however, be supplemented with an explicit overall objective of achieving a high level of environmental protection. A duty at this higher level clearly emphasises the overall goal to be achieved, without being tied to the direct application of specific environmental principles and also fulfils the purpose of adherence to the non-regression principle. It would provide a clear direction to policy, assisting in those cases where different interpretations of the more specific principles can come into tension.

The proposed formulation of the duty is at the weaker end of the spectrum of such obligations. A duty to “have regard” is not meaningless, most importantly in ensuring that the principles are always relevant considerations in ministerial decision-making. Yet in all but the most egregious cases where there has been absolutely no visible attempt to give thought to what the principles suggest, a decision that fails to reflect the principles will not be subject to legal challenge. The principles should be given more weight, either by requiring a statement of how they have been taken into account (and what conflicting principles and objectives have legitimately been given preference), or by imposing a stronger obligation.

A strong obligation would be to require Ministers to “act in accordance with” the principles, but that might be seen as too restrictive. Existing statutory provisions in the environmental field provide various formulations which are somewhat stronger:

the biodiversity duty on public bodies “to further the conservation of biodiversity so far as is consistent with the proper exercise of [their] functions” (Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004, section 1);

the duty on planning authorities to act “with the objective of contributing to the achievement of sustainable development” in relation to development planning (Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997, section 3E);

the duty on Scottish Ministers, SEPA and “the responsible authorities” to act “in the way best calculated to contribute to the achievement of sustainable development” (Water Environment and Water Services (Scotland) Act 2003, section 2);

duties on a public body under section 44 of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 to act “in the way best calculated to contribute to the delivery of the targets” and “in a way that it considers is most sustainable”.

Dr Annalisa Savaresi, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Law at the University of Stirling stated:

The creation of a less muscular legal underpinning for said principles – as the wording suggested by the Scottish Government ‘have regard to’ seems to suggest – would increase the discretion of policymakers in Scotland. Over time, this arrangement may result in the loss of certainty and consistency in the interpretation and application of environmental principles, the emergence of a more ad hoc, piecemeal approach, and, eventually, less coherent/effective environmental protection. I have already expressed this concern in the context of the 2018 Scottish Parliament ECCLR Committee’s inquiry [see the evidence I submitted with Prof Little, available at: https://www.parliament.scot/S5_Environment/Inquiries/012_Little_and_Savaresi_EEAW.pdf].

Since the consultation, Scottish Environment LINK has published some more material, including a recent blog on the Bill, and a January 2020 briefing for the Scottish Parliament Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee, which stated:

The wording of the duty should also be strengthened from ‘have regard to’ to ‘act in accordance with’ – this would be equivalent to the Lisbon Treaty’s requirement that policy “shall be based on” these principles.

Scottish Environment LINK. (2020). LINK Parliamentary Briefing: ECCLR Session on Environmental Principles and Governance January 2020. Retrieved from https://www.scotlink.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Briefing-for-ECCLR-Principles-and-Governance-Session-10th-Jan-2020.pdf [accessed 6 August 2020]

and:

LINK would strongly support powers to add further principles to the duty once they have been duly considered, or exploration of alternative ways to enshrine other key principles in law. LINK is particularly concerned about the loss of the Integration Principle, which is also embedded within the EU treaties and requires that environmental protection is integrated into all other policy areas and activities, with a view to promoting sustainable development

Measures on environmental principles in the rest of the UK

The UK Government has introduced provisions on environmental principles in the UK Environment Bill.

As a blog from Prof Colin T Reid outlines (on the Brexit and Environment website):

the [Scottish] Bill adopts the four key principles from the EU Treaty – precautionary, preventive, rectification at source and polluter pays

[...]

The Environment Bill at Westminster, by contrast, adds a fifth principle – integration – but without any reference to how the principles are interpreted within the EU. It is only ministers who are affected and they are required to “have due regard” not to the principles themselves but to the policy statement on principles that the Secretary of State must produce.

In May 2020 SPICe produced a briefing on the UK Environment Bill1. This states:

There is likely to be discussion about what impact the environmental principles set out in the Bill could have in Scotland in relation to both reserved areas, and devolved areas that are regulated on a UK-wide basis. It will be necessary to consider which set of principles, and associated guidance, would apply in complex areas of devolution - for example in relation to decision-making on marine planning or licensing in Scottish offshore waters (12-200nm) which is executively devolved, not legislatively.

The Law Society of Scotland said in evidence to the Public Bill Committee on the Environment Bill on 12 March 2020 that as the Bill provides for environmental principles to apply in England only, it is not clear how reserved functions of UK Ministers in Scotland will be covered. Scottish Environment LINK said that this seems to be a gap in the Bill and encouraged the Scottish and UK Governments to work together to agree a statement about how principles will apply coherently.

A new domestic environmental governance body - Environmental Standards Scotland

Background: what is the environmental 'governance gap'?

Environmental governance in the UK presently includes significant EU arrangements (in addition to domestic ones). The EU arrangements ranging from law-making, implementation reviews and enforcement action, to financial support and cooperation activities.

Enforcement of EU law happens mainly through the the European Commission, which supports best practice but can ultimately bring Member States before the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU). If found to be in breach, infraction fines can be imposed on the Member States. In addition to the enforcement powers of the Commission, members of the public and NGOs can initiate legal action before Member State courts to request compliance with EU law and can make complaints directly to the Commission.

Both the UK and Scottish Governments have recognised that if unmitigated, the loss of EU governance arrangements would result in environmental governance gaps, and therefore EU exit requires the EU governance arrangements to be somehow replaced.

More detailed information on environmental governance and EU Exit can be found in the SPICe briefing, SB 20-02: Environmental Governance in Scotland after EU Exit.

In their response to the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee call for views on the Bill the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) included a useful diagram showing the organisations involved in environmental scrutiny (and other functions) in Scotland2:

Consultation & development of the governance proposals

During the passage of the first Continuity Bill in March 2018, public debate on the environmental 'governance gap' led to legislative amendments addressing the issue. The Scottish Government accepted an amendment which required it to prepare proposals and consult on:

how to ensure that there continues to be effective and appropriate governance relating to the environment following the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU.

section 26A, UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Legal Continuity) (Scotland) Bill

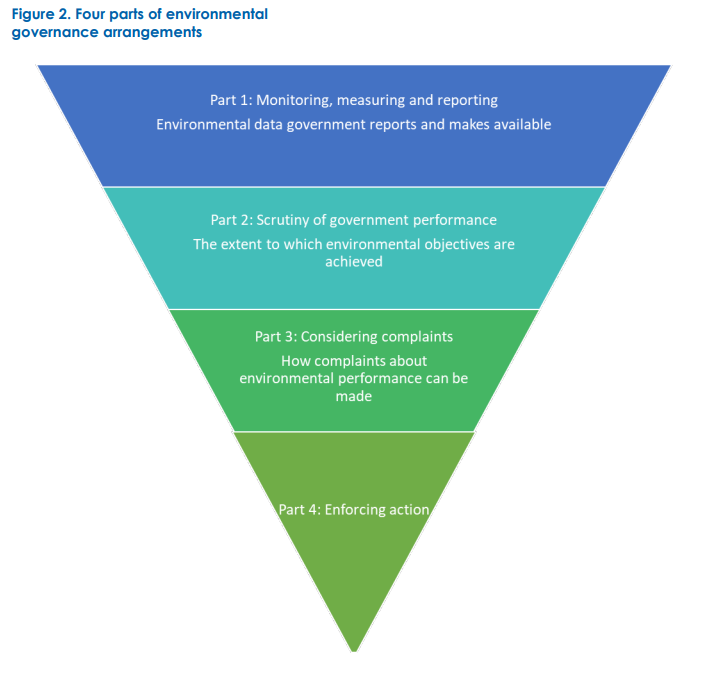

While the Bill did not become law, the Scottish Government did consult in February 2019. The consultation was informed by the Roundtable on Environment and Climate Change and defined "four key parts to environmental governance arrangements, which can overlap and interact":

The consultation's proposals and common stakeholder responses under each heading are briefly summarised:

Monitoring, measuring and reporting activities. The consultation indicated that the existing EU monitoring, measuring and reporting requirements are expected to be saved in domestic legislation initially, followed by a review to rationalise current programmes. Dominant themes in the consultation responses were to highlight the value of current EU arrangements and for the review to address transparency issues. The proposed review is not addressed in the Bill.

Scrutiny of government performance and the extent to which stated environmental objectives are being achieved. The consultation indicated that the Scottish Government had not yet reached a conclusion on the best institutional arrangements to support scrutiny, but that key features of any future arrangements were (a) access to specialist expertise and skills, (b) independence from government, and (c) adequate powers. This section of the consultation also addressed which policy areas should be included within the scope of any scrutiny arrangements. The majority of consultation responses supported the creation of a new environmental governance body. On scope, the most common themes in stakeholder responses were agreement with the policy areas suggested, and, calls for other policy areas to be included or the inclusion of any/all policy areas relevant to the environment.

A mechanism to consider any complaints by members of the public or civic organisations. The consultation indicated that the Scottish Government had not reached a conclusion about whether a new body would be needed to deliver this function. Consultation responses supported the need for such a function, with an independent body or watchdog most commonly suggested.

Enforcing action with respect to legal compliance by government and its agencies in correctly interpreting and following environmental law. The consultation recognised that it will not be possible to replace the supranational role played by the European institutions, and indicate that the Scottish Government had "not yet reached a conclusion about whether any additional measures are needed, or whether greater use of existing domestic remedies might be sufficient". The most frequent theme in consultation responses was what could be done to address the loss of EU enforcement, with the most common suggestion the creation of an independent body / watchdog.

Following the consultation, proposals for new environmental governance arrangements have been included in the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill.

What the Bill does (Part 2, Chapter 2)

Part 2, Chapter 2 establishes a new public body called Environmental Standards Scotland (ESS) and in Gaelic, Ìrean Àrainneachdail na h-Alba. ESS is to have operational independence of Scottish Ministers and is designed to provide "continuity of environmental governance" as the EU's regime falls away.

The Scottish Government's Policy Memorandum states:

The objective is to ensure that there continues to be effective environmental governance following the end of the implementation period, and the consequential cessation of the role of the EU institutions. This will ensure that there is a transparent oversight of the performance of public bodies in Scotland, other than reserved bodies, in the effective and complete implementation of environmental law, reducing risks to the environment, and ensuring that standards that are set in legislation are upheld in the actions of public bodies and in regulatory practice.

This will help to maintain the reputation of Scotland as a country with high environmental standards, and ensure transparency in those standards as the Scottish Government seeks to maintain close relationships with its European neighbours.

Scottish Government. (2020, June 18). Explanatory Notes: UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill. Retrieved from https://beta.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/current-bills/uk-withdrawal-from-the-european-union-continuity-scotland-bill-2020/introduced/explanatory-notes-uk-withdrawal-from-the-european-union-continuity-scotland-bill.pdf

The new body is envisioned by the Scottish Government to employ around 20 staff with a budget of around £1.5 million a year when it is fully functioning.2

Sections 16-18: functions of ESS

The functions of Environmental Standards Scotland (ESS), as set out in Section 16, are to:

Monitor - ESS is to monitor public authorities’ compliance with environmental law, the effectiveness of environmental law, and how environmental law is implemented and applied.

Investigate - ESS is to investigate any matter concerning whether a public authority is failing (or has failed) to comply with environmental law, as well as any matter concerning the effectiveness of environmental law or how it is (or has been) implemented or applied.

Take action - ESS may take appropriate action to secure a public authority’s compliance with environmental law, and to secure improvement in the effectiveness of environmental law or in how it is implemented or applied. The ways in which it may take action are set out in Powers and duties.

Section 16 also states that ESS must act objectively, impartially, proportionately and transparently.

Important definitions: what is meant by "public authorities" and "environmental law" in this Bill?

The meaning of "public authority" in this Bill is important because it defines who ESS can monitor, investigate and take again against. Section 37 defines public authorities for the purposes of this Bill as "a person exercising any function of a public nature", but excluding courts and tribunals, UK Government Ministers, and the Scottish and UK Parliaments (including persons exercising a function in connection with the proceedings of either parliament). Could ESS therefore monitor and take action against Scottish Ministers? Yes, Scottish Ministers are included in the definition of public authorities in this Bill.

The wording of "a person exercising any function of a public nature" is very similar to that in the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA), and there is extensive caselaw on whether particular bodies fall under this definition for HRA purposes.

The meaning of "environmental law" in this Bill is also important because it defines the scope of law and legislation which ESS will be monitoring public authorities' compliance with. This scope is discussed in Scope of functions and powers.

Section 17 allows for ESS's functions to be modified by regulations (affirmative procedure) to take account of any obligations created by an agreement between the UK and EU on their future relationship. For example, the EU's draft agreement text envisages a specific requirement for an independent body (or bodies) in the UK, such as ESS.

Section 18 requires ESS to publish a strategy and exercise its functions in accordance with the strategy. Schedule 2 sets out further detail on what the strategy must cover.

Sections 19-34: powers and duties

The Bill creates a duty on public authorities to co-operate with ESS. Scottish Ministers envisage that this will enable public authorities and ESS to resolve matters by agreement wherever possible.1 Under Section 19, public authorities must:

co-operate with ESS, and give it such reasonable assistance as it requests, and

make all reasonable efforts to resolve failures identified by ESS and reach agreement on remedial action.

The Bill also provides ESS with three enforcement powers designed to ensure compliance with, and effectiveness of, environmental law:

Information notice - a 'backstop' power for ESS's investigations

Compliance notice - for use in instances of regulatory failure

Improvement report - to address systemic failures

These powers are described in turn below.

Information notice

Sections 20-21 provide for an information notice. Scottish Ministers expect that, in the vast majority of instances, information will be supplied by public authorities under the general co-operation duty at section 19. In that sense, information notices are a 'backstop' power that can be used to require a public authority to provide specific information.

Information notices are enforceable though the courts. Section 21 states:

(1) Where a public authority fails, without reasonable excuse, to comply with an information notice issued to it under section 20(1), Environmental Standards Scotland may report the matter to the Court of Session.

(2) After receiving a report under subsection (1), and hearing any evidence or representations on the matter, the Court may (either or both)— (a) make such order for enforcement as it considers appropriate, (b) deal with the matter as if it were a contempt of the Court.

Compliance notice

Sections 27-33 provide for a compliance notice. A compliance notice is a notice requiring the public authority to whom it is issued to take the steps set out in the notice in order to address its failure to comply with environmental law.

For the compliance notice to be issued, ESS must consider that:

in exercising its regulatory functions, the public authority is failing to comply with environmental law (or has previously failed and is likely to do so again), and

that this failure has caused, is causing or risks causing environmental harm.

However there is a significant restriction to this power. ESS may not issue a compliance notice in instances where the public authority's failure to comply with environmental law is due to a regulatory decision on a individual case (for example, a decision on an application for a licence or a decision on regulatory enforcement in a specific case) (section 28(1)). Scottish Ministers explanation for this restriction is that there are existing routes for appeal in such cases:

This restriction ensures that compliance notices are not used as a means to review individual regulatory decisions or as a substitute appeal process.

Scottish Government. (2020, June 18). Explanatory Notes: UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill. Retrieved from https://beta.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/current-bills/uk-withdrawal-from-the-european-union-continuity-scotland-bill-2020/introduced/explanatory-notes-uk-withdrawal-from-the-european-union-continuity-scotland-bill.pdf

Sections 29-31 describe the content of a compliance notice and allow for a notice to be varied or withdrawn.

Section 32 provides for appeals. A public authority issued with a compliance notice may make an appeal to the sheriff court within 21 days (or later with the sheriff’s permission). The sheriff may cancel the compliance notice or confirm the notice, either with or without modifications.1

Compliance notices are enforceable though the courts in the same way as information notices (see above).

Improvement report

Sections 22-26 provide for an improvement report and improvement plans. An improvement report is a report prepared by ESS identifying a systemic failure in relation to environmental law and recommending remedial actions. The report is laid before the Scottish Parliament and is published. Scottish Ministers must respond to this report with an improvement plan. Scottish Ministers envisage that improvement reports will be used only on an exceptional basis. The Bill's explanatory notes state:

This power is generally available to Environmental Standards Scotland for addressing matters of genuine strategic importance. The co-operation duty on public authorities at section 19, coupled with the requirement [for ESS's strategy] to set out how it intends to resolve issues through agreement, are intended to ensure that most matters that come to the attention of Environmental Standards Scotland are resolved without any formal exercise of its powers.

Scottish Government. (2020, June 18). Explanatory Notes: UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill. Retrieved from https://beta.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/current-bills/uk-withdrawal-from-the-european-union-continuity-scotland-bill-2020/introduced/explanatory-notes-uk-withdrawal-from-the-european-union-continuity-scotland-bill.pdf

Sections 22-23 set out when an improvement report can be prepared. This is if ESS considers that, in exercising its functions, a public authority (or authorities) has failed to:

(a) comply with environmental law,

(b) make effective environmental law, or

(c) implement or apply environmental law effectively.

As is the case with compliance notices, failure cannot relate to a regulatory decision on a individual case. ESS must also be satisfied that the failure could not be addressed more effectively by issuing a compliance notice instead, and cannot prepare an improvement plan in conjunction with a live compliance notice. ESS could however withdraw a compliance notice and switch to an improvement report process if it considers this appropriate.

Section 24 defines what an improvement notice must contain. This includes details of the alleged failure and proposals for a timescale for Scottish Ministers, or other public authority, to take the remedial measures recommended in the report.

Section 26 requires Scottish Ministers to respond to an improvement report with an improvement plan. Within 6 months (or 9 months if consulting with others) of an improvement report, Scottish Ministers must lay an improvement plan before the Scottish Parliament. This plan must detail:

the measures that the Scottish Ministers propose to take to implement the recommendations in the improvement report (in full or in part),

the proposed timescale for implementing the recommendations,

the arrangements for reviewing, and reporting on, progress in implementing the recommendations, and

if the Scottish Ministers do not intend to implement the recommendations in the improvement report (in full or in part), the reasons for that.

When the plan is laid before the Scottish Parliament, there is then a period of 40 days during which, if the Scottish Parliament resolves that the plan should not be approved, Scottish Ministers must review and revise the plan, having regard to any views expressed by the Parliament. Scottish Ministers must then lay any revised plan within 3 months and this revised plan is again subject to the 40 day period.

Under Section 26(7), Scottish Ministers must publish the plan once the Scottish Parliament resolves that it should be approved.

Judicial Review

In addition to its compliance notice and improvement report powers, ESS may also apply for judicial review of a public authority’s conduct or intervene in an existing case. Scottish Ministers state that these powers are expected to be used by ESS only rarely.1

What is judicial review?

Judicial review is the process by which a court reviews a decision, act or failure to act by a public body or other official decision maker. Intervening in an existing case involves third parties providing written or oral arguments on key legal issues relating to the case.2 For further information see SPICe Briefing 16/62: Judicial Review.

Section 34 sets a higher bar for ESS to apply for judicial review (or intervening), compared with when it can take action using a compliance notice. ESS may only make an application for judicial review (or intervention) in relation to a "serious" failure to comply with environmental law and where it is necessary to make the application (or intervention) to prevent, or mitigate, serious environmental harm. Schedule 2 requires ESS to set out in its strategy how it intends to determine whether environmental harm is serious.

Section 34(6) would facilitate any application for judicial review (or intervention) by ESS as it provides that ESS has "sufficient interest" in any test of its 'standing' in relation to the case. The rules on ‘standing’ determine who may take part in an action for judicial review. The three-month time limit for raising a judicial review action remains in place.

Section 34 (7) sets out that "court", for the purposes of Section 34, means the Court of Session, the sheriff, the Sheriff Appeal Court and the Scottish Land Court. It is understood, however, that Judicial Review proceedings brought by ESS, or to which they are party, may be considered by the highest appeal court, the Supreme Court.

For further information on what the grounds of judicial review are, and the remedies that can be granted by the court if an action for judicial review is successful, see SPICe Briefing 16/62: Judicial Review.

Scope of functions and powers

This part of the briefing explores how and when ESS can use its powers.

What "environmental law" is within ESS's remit?

The meaning of "environmental law" in the Bill is important because it defines the scope of law and legislation which ESS will be monitoring public authorities' compliance with.

The Bill defines environmental law in section 39 as:

any legislative provision to the extent that it is (a) mainly concerned with environmental protection, and (b) is not concerned with an excluded matter.

“Legislative provision” is defined as:

provision contained in, or in an instrument made under, an Act of the Scottish Parliament, and

provision contained in any other enactment which, if contained in an Act of the Scottish Parliament, would be within the legislative competence of the Parliament.

In other words, any enactments that deal with devolved issues whether they are made by the Scottish or UK parliaments (or previously by the EU institutions). This includes both primary legislation (Acts) and secondary legislation (statutory instruments).

Scottish Minister's "executive devolution" powers (under section 63 of the Scotland Act 1998) remain reserved as far as legislative competence is concerned, and therefore do not fall within ESS's remit.

“Environmental protection” is defined in section 40 as:

protecting, maintaining, restoring or improving the quality of the environment,

preventing, mitigating, minimising or remedying environmental harm caused by human activities,

monitoring, considering, assessing, recording, reporting on or managing data on anything relating to paragraphs (a) and (b).

Excluded matters are:

disclosure of, or access to, information,

national defence or civil emergency,

finance or budgets.

However an additional area of law is also 'carved out' from the definition of environmental law. Section 39(4) states that:

the definition of “environmental law” in subsection (1) does not include Parts 1 to 3 of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009.

Parts 1 to 3 of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 are concerned with setting and reporting on Scotland's greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets, including the production of the Climate Change Plan. The Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019 also added Part 2A to the 2009 Act establishing a citizen's assembly process.

Finally, the definition of environmental law can be amended by regulations. Sections 39(5) - 39(8) provide Scottish Ministers with a regulation-making power to include (or exclude) a specific legislative provision within (or from) the definition of “environmental law”. These regulations would be subject to the affirmative procedure and a requirement on Scottish Ministers to consult with ESS and other persons as the Scottish Ministers consider appropriate.

What about international law and obligations?

Many environmental problems do not respect national borders. Recognising this, there is a relatively large body of international agreements covering environmental matters to which the UK has signed up. For example the Paris Agreement on climate change and Montreal Protocol on the ozone layer. Many of these international agreements create obligations on the UK to act in a certain way. And because environmental matters are generally devolved, many of the obligations concerning the environment fall to the Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament to implement.

What role will ESS have in monitoring and enforcing these international obligations?

International obligations themselves do not fall within the Bill's definition of environmental law. Therefore ESS will not be able to monitor, enforce and take action to ensure Scottish Public bodies' compliance with international obligations related to the environment except where they have been incorporated into domestic (Scottish or UK) devolved law.

However:

1.) The Scotland Act 1998 (as amended) is designed to ensure that it is within the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament to implement any international obligation signed up to by the UK that falls within devolved competence.

2.) Section 16(2) provides ESS with a "review" function (within the devolved sphere):

In exercising its functions, Environmental Standards Scotland may, in particular...

(e) keep under review implementation of any international obligation of the United Kingdom relating to environmental protection,

(f) have regard to developments in, and information on the effectiveness of, international environmental protection legislation,

Does Brexit change things?

EU law is presently the conduit through which the UK implements many of its international obligations on several environmental matters. This will cease to be the case at the end of the transition period. For further discussion see Environmental Governance in Scotland after EU Exit, SB 20-02.1

When can ESS take compliance action?

As set out in its functions, ESS can investigate questions of, and take action to secure public authorities' compliance with environmental law. While Scottish Ministers anticipate that most issues will be resolved by co-operation, compliance notices are ESS's primary formal power to remedy a public authority's failure to comply with environmental law.

To issue a compliance notice ESS must consider that the public authority has both (a) failed to comply with environmental law and (b) that this failure has or will be likely to cause environmental harm.

The definition of "failure to comply" and "environmental harm" are therefore both important when considering the scope of ESS's powers.

Section 38 sets out what constitutes a public authority's failure to comply:

the authority failing (or having failed) to take proper account of environmental law when exercising its functions,

the authority exercising (or having exercised) its functions in a way that is contrary to, or incompatible with, environmental law,

the authority failing (or having failed) to exercise its functions where the failure is contrary to, or incompatible with, environmental law.

This definition therefore includes failure because an authority has not acted when it is required to do so by environmental law.

"Environmental harm" is defined broadly as:

(a) harm to the health of human beings, animals, plants or any other living organisms, (b) harm to the quality of the environment, including— (i) harm to the quality of the environment taken as a whole, (ii) harm to the quality of air, water or land, and (iii) other impairment of, or interference with, biodiversity or ecosystems, (c) offence to the senses of human beings, (d) damage to property, or (e) impairment of, or interference with, amenities or other legitimate uses of the environment.

This definition of harm is essentially the same as that contained in section 17 of the Regulatory Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 which updated SEPA's statutory purpose and powers.1

How can ESS improve "effectiveness"?

Alongside ensuring compliance with environmental law, ESS's role is to secure improvement in the effectiveness of environmental law. Section 39(9) provides that 'effectiveness' is to be understood in this context as the law's effectiveness at achieving its intended purpose of:

environmental protection, and

improving the health and wellbeing of Scotland’s people, and achieving sustainable economic growth, so far as consistent with environmental protection.

While Scottish Ministers anticipate that most issues will be resolved by co-operation, improvement reports are ESS's primary formal power to address issues of effectiveness (as well as systemic non-compliance).

The Bill makes a distinction between (1) making effective environmental law, and (2) implementing or applying environmental law effectively. Implementing/applying environmental law effectively is not further defined in the Bill. Making effective environmental law is defined, in section 41(2)(b), with reference to subordinate legislation (i.e. not primary legislation):

references (however expressed) to... a public authority failing to make effective environmental law are references to the authority—

(i) failing to exercise any function it has of making, confirming or approving subordinate legislation, or

(ii) failing to exercise that function in such a way,

so as to secure the effectiveness of environmental law.

While most primary legislation is introduced by the Scottish Government, it is the Scottish Parliament that makes primary legislation. The Scottish Parliament is not defined as a public authority and therefore outwith ESS's remit.

Sections 35-36: information disclosure

Section 35 is designed to allow for information to be disclosed to ESS to facilitate ESS's investigative functions. Section 36 governs when that information can be made public.

Section 35 disapplies any rule of law (apart from data protection legislation) that would stop a public authority sharing information with ESS, when that public authority is acting under the general duty to co-operate with ESS (section 19) or because that public authority has been issued an information notice. There are two exceptions to this rule. These exceptions preserve the rules surrounding civil proceedings which entitle a public authority to refuse to provide information on grounds of "confidentiality of communications" or "public interest immunity".

Section 36 provides for the confidentiality of information and correspondence relating to ongoing proceedings, where ESS is considering a potential use of its powers.1

Section 36(1) prohibits ESS disclosing information it has received:

under the general duty to co-operate,

in response to an information notice, or

by correspondence with a public authority which relates to ongoing proceedings.

Unless it is a disclosure (section 36(2)):

made with the consent of the public authority who provided the information or correspondence,

made for purposes connected with the exercise of ESS’s functions,

made to the Office for Environmental Protection, or any other environmental governance body, for purposes connected with the exercise of an environmental governance function,

that relates only to a matter to which ESS has concluded it will take no further action.

Similarly, public authorities are restricted in their ability to disclose information or correspondence relating to ongoing ESS proceedings, except: in co-operating with any investigation being carried out by ESS; responding to any information notice or compliance notice; any civil court proceedings; or with ESS's consent (section 36(4)).

Subsections (5) and (6) include some rules on ESS's consent to disclose: ESS may only give consent to a public authority to disclose an information notice, a compliance notice or an unpublished draft of an improvement report if it has concluded it will not take any further action in the case; and ESS must give consent to a public authority to disclose correspondence where ESS has concluded it will not take any further action in the case.

The Environmental Information (Scotland) Regulations 2004 require Scottish public authorities to publish environmental information and make it available on request, subject to some exemptions.2 Subsection (7) defines the information and correspondence collected by ESS in relation to ongoing proceedings as falling under one of those exemptions.

Schedule 1, paragraph 14(2) of the Bill brings ESS under the freedom of information regime by adding ESS to the list of public authorities to which the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 applies.

Schedule 1: organisation

The structure, membership and governance of ESS is set out in schedule 1.

Paragraph 1 establishes the nature of ESS's independence from Scottish Ministers:

(1) In performing its functions, Environmental Standards Scotland is not subject to the direction or control of any member of the Scottish Government.

(2) Sub-paragraph (1) is subject to any contrary provision in this or any other enactment.

An “enactment” in this context includes not just Acts of the Scottish Parliament, but also UK Acts and secondary legislation (by virtue of the definition in Interpretation and Legislative Reform (Scotland) Act 2010, Schedule 1).

Paragraphs 2-5 deal with the appointment of corporate board members. ESS is to consist of a chair and at least 4 but no more than 6 other members. Members will be appointed by Scottish Ministers only following approval by the Scottish Parliament. Appointments are for up to 4 years, extendable once. As is normal for appointments to public bodies, the Bill lists a set of people who cannot be appointed, for example sitting parliamentarians, civil servants and people who are insolvent or disqualified from being a company director.

Paragraph 6 provides for the first chief executive to be appointed by Scottish Ministers with Scottish Parliament approval. Subsequent chief executives are to appointed by ESS.

Paragraphs 7 to 11 provide ESS with a legal basis to perform procedural functions.

Paragraph 12 requires an annual report.

Transitional arrangements

Schedule 1, Paragraph 13 provides for technical arrangements to transition board members between a "non-statutory ESS" and a statutory version upon the commencement date of Section 15.

The Scottish Government expect there will be a gap between the end of the transition period and the establishment of ESS:

It is unlikely that the progress of the Bill will allow a full legal establishment of the new body before April 2021. In 2020/21, there will be costs, to cover the costs of maintaining governance in a transitional arrangement from the start of 2021, and the costs of establishing the new body. This cost in 2020/21 is estimated as between £200,000 - £300,000.

Scottish Government. (2020, June 18). UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill Financial Memorandum. Retrieved from https://beta.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/current-bills/uk-withdrawal-from-the-european-union-continuity-scotland-bill-2020/introduced/financial-memorandum-uk-withdrawal-from-the-european-union-continuity-bill.pdf [accessed 8 July 2020]

Board members for a non-statutory ESS are being recruited at the time of this briefing's publication. The advert on the Scottish Government's public appointments website states:

Environmental Standards Scotland will be established, initially, on a non-statutory basis from January 2021. It will transition to a statutory, independent body over the course of 2021.

The Board will initially comprise of the Chair and two other members. Once Environmental Standards Scotland becomes established as a statutory organisation, further board appointments are expected.

Scottish Government. (n.d.) Public appointments: Chair & Members - Environmental Standards Scotland. Retrieved from https://applications.appointed-for-scotland.org/pages/job_search_view.aspx?jobId=2781 [accessed 24 July 2020]

Schedule 2: strategy

Section 18 requires ESS to publish a strategy and introduces Schedule 2. The schedule sets out what the ESS strategy must contain and procedures for the strategy's development. The procedure includes consultation and a veto for the Scottish Parliament.

Paragraph 1 states that the strategy must set out how ESS intends to:

(1)(a) monitor— (i) public authorities’ compliance with environmental law, and (ii) the effectiveness of environmental law and of how it is implemented and applied,

(b) provide for persons (including members of the public, non-government organisations and other bodies) to make representations to it about any matter concerning— (i) whether a public authority is failing (or has failed) to comply with environmental law, (ii) the effectiveness of environmental law or of how it is (or has been) implemented or applied,

(c) handle those representations, including how it will keep persons informed about its handling of their representations,

(d) exercise its functions in a way that respects and avoids any overlap with— (i) other statutory regimes (including statutory provision for appeals) or administrative complaints procedures, (ii) the exercise of functions by either the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman or the Commissioner for Ethical Standards in Public Life in Scotland, (iii) the exercise of functions by any committee of the Scottish Parliament for the time being appointed by virtue of standing orders, whose responsibilities include considering matters relating to environmental law,

(e) determine whether to carry out an investigation into any matter concerning— (i) whether a public authority is failing (or has failed) to comply with environmental law, (ii) the effectiveness of environmental law or of how it is (or has been) implemented or applied,

(f) carry out and prioritise any such investigations,

(g) engage with the public authorities it investigates with a view to — (i) swiftly resolving (so far as possible without the need to issue a compliance notice or prepare an improvement report) any matter concerning a failure to comply with environmental law, to make effective environmental law or to implement or apply it effectively, and (ii) reaching agreement on any appropriate remedial action to be taken for the purpose of environmental protection, and

(h) identify and recommend measures to improve the effectiveness of environmental law or of how it is implemented or applied.

In addition, the strategy must set out:

(2)(a) the general factors that Environmental Standards Scotland intends to consider before exercising its functions (including its power to require public authorities to provide information),

(b) how Environmental Standards Scotland intends to—

(i) take account of different kinds of information (for example, evidence, research, independent and expert advice and developments in international environmental protection legislation) for the purpose of exercising its functions,

(ii) determine what constitutes a systemic failure for the purpose of section 22(2) [improvement report],

(iii) determine whether a failure to comply with environmental law could be addressed more effectively by issuing a compliance notice (rather than by preparing an improvement report) for the purpose of section 22(3),

(iv) determine whether a failure to comply with environmental law is serious for the purposes of section 34(1)(a) and (4)(a) [judicial review],

(v) determine whether environmental harm is serious for the purposes of section 34(1)(b) and (4)(b) [judicial review], and

(c) any other information that Environmental Standards Scotland considers is appropriate to include.

Paragraph 2 defines a procedure for developing the strategy which includes requirements for consultation and a veto for the Scottish Parliament.

Within 12 months of becoming a statutory body, ESS must produce a strategy and lay a copy before the Scottish Parliament (paragraph 3(2)).i In developing any strategy, ESS must consult the general public and consult with the public authorities over which it has power to monitor, investigate and take action (paragraph 2(3)). When the draft strategy is laid before the Scottish Parliament, there is then a period of 40 days during which the Scottish Parliament can veto it by resolving that the strategy should not be approved (paragraph 2(5)). If that happens, ESS must:

(paragraph 2(5)(a)) review and revise the strategy, having regard to any views expressed by the Parliament in relation to the strategy,

ESS must lay any revised strategy within 3 months (paragraph 2(5)(b)). This revised strategy is again subject to the 40 day period. Once the 40 day period has passed without the parliamentary veto being used, ESS may publish the strategy.

Paragraph 4(1) requires ESS to review the strategy "from time to time" and revise it if ESS considers that appropriate.

Interaction with environmental governance measures in the rest of the UK

ESS's remit covers environmental law in devolved areas; but it may also collaborate with other similar bodies in the UK.

Section 16(2) of the Bill states:

In exercising its functions, Environmental Standards Scotland may, in particular...

(g) collaborate with any other environmental governance body in the United Kingdom, including the Office for Environmental Protection, or such other persons as Environmental Standards Scotland considers appropriate

The Office for Environmental Protection (OEP) is a governance body similar to ESS being considered by the UK Parliament as part of the Environment Bill 2019-21. The OEP's remit will cover England and Northern Ireland, and extend to Scotland and Wales in respect of reserved matters.

Clauses in the UK Environment Bill:

anticipate future relationships between the OEP and any future environmental governance bodies set up in devolved areas, such as ESS.

provide that the OEP should consult a devolved environmental governance body if the work it is undertaking would be relevant to them.

enables the OEP to share certain information with a devolved environmental governance body which might otherwise be confidential.

See SPICe Briefing 20-37: UK Environment Bill for further information.

Section 16(2) of the Bill also refers to ESS's ability to collaborate with "other persons as... appropriate". The Scottish Government state in the Bill's explanatory notes that:

Other persons could include relevant international bodies, such as the European Commission. This will allow joint working on policy effectiveness, and sharing of experience and best practice.

Scottish Government. (2020, June 18). Explanatory Notes: UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill. Retrieved from https://beta.parliament.scot/-/media/files/legislation/bills/current-bills/uk-withdrawal-from-the-european-union-continuity-scotland-bill-2020/introduced/explanatory-notes-uk-withdrawal-from-the-european-union-continuity-scotland-bill.pdf

Stakeholder views and discussion

Is a new body required?

Calls for the creation of a new independent body or watchdog to take on some or all elements of the EU’s current governance role was a common theme in responses to the Scottish Government's consultation on Environmental Principles and Governance.

However this view was not supported by all respondents.

The Scottish Public Services Ombudsman's (SPSO) consultation response points to its status as an existing body that handles complaints independent of government. The SPSO notes its jurisdiction already includes public authorities in Scotland and a potential expansion of its powers that would allow for public interest investigations more suited to environmental matters. The SPSO's response states:

In summary, we consider if the current complaints systems is not sufficient we would strongly recommend that consideration is first given to whether the existing systems can be adapted, rather than creating new complaint routes, particularly in relation to the wider, public value investigations.

Scottish Public Services Ombudsman. (n.d.) Response 48652774. Retrieved from https://consult.gov.scot/environment-forestry/environmental-principles-and-governance/consultation/view_respondent?_b_index=60&uuId=48652774 [accessed 15 July 2020]

Consultation responses from the Mineral Products Association Scotland2 and National Farmers Union Scotland3 both question the value of creating a new public body over an expansion or enhancement of the current domestic system.