Issue 8: EU-UK Future Relationship Negotiations - UK legal text special edition

Following the UK's departure from the EU, the negotiations to determine the future relationship began on 2 March 2020. Over the course of the negotiations, SPICe will publish briefings outlining the key events, speeches and documents published. This special edition focuses on the legal agreement texts proposed by the UK during the negotiations and published publicly on 19 May 2020.

Executive Summary

On 19 May, the UK government published a series of legal texts setting out its proposals for the UK and EU's future relationship. The legal texts and annexes provide the legal form of the proposals made in the UK government document The Future Relationship with the EU which was published in February 2020.

The UK government has emphasised its view that its proposals have precedent in other trade deals and international agreements the EU has already signed or proposed. In contrast, the European Commission's chief negotiator Michel Barnier has rejected the idea that past agreements necessarily create precedents. EU-UK negotiations continue this week but have so far been characterised by little progress and disagreements over governance, level playing field commitments and fisheries.

This briefing examines the UK's proposals contained in its legal texts which have implications for devolved competences. This includes the UK proposals in relation to trade for:

a Free Trade Area with zero tariffs, no charges or quantitative restrictions and an ambitious system of rules of origin.

protecting humans, animals, and plants from diseases, pests, or contaminants.

regulatory cooperation across a wide range of services sectors and trade liberalisation in areas like professional and business services.

a framework to manage the EU's "equivalence" decisions that would allow for trade in financial services.

geographical indications for food.

level playing field issues, including state aid and sustainable development.

On fisheries, the UK government's draft agreement proposes that the current arrangements end and that future fishing opportunities should be negotiated annually and based on an assessment of where fish stocks are located (rather than on a country's historic landings).

On energy, the UK proposes an agreement to manage energy trading, and shows a willingness to link a future UK emissions trading system with the EU's system.

On social security, UK proposals are much more limited in scope than either the current rules or the EU’s proposed draft text, and as a result do not include devolved areas of social security policy.

On law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters, UK proposals include an extradition arrangement and access to a range of data sharing, including real time law enforcement data. The UK does not propose membership of the European Arrest Warrant system, Europol or Eurojust.

The negotiations so far

The EU-UK negotiations on a future relationship have, so far, been characterised by little progress and incompatible red lines for both sides. Key differences focus on governance, level playing field commitments and fisheries.

The fourth round of negotiations are taking place this week by videoconference.

UK's legal texts

On 19 May, the UK government published a series of legal texts setting out its proposals for the UK and EU's future relationship. The legal texts and annexes provide the legal form of the proposals made in the UK government document The Future Relationship with the EU which was published in February 2020.

The UK government has emphasised its view that its proposals have precedent in other trade deals and international agreements the EU has already signed or proposed. In contrast, the European Commission's chief negotiator Michel Barnier has rejected the idea that past agreements necessarily create a precedent.

The areas covered by the UK's legal texts are:

A draft comprehensive free trade agreement and annexes

A draft fisheries framework agreement

A draft air transport agreement

A draft civil aviation safety agreement and annexes

A draft energy agreement

A draft civil nuclear agreement

A draft agreement on law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters

A draft agreement on the transfer of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children

A draft agreement on the readmission of people residing without authorisation

This briefing examines the negotiating texts which have implications for devolved competences.

In contrast to the UK's approach of seeking multiple agreements, the EU has proposed in its negotiating text (published on 18 March 2020) an overarching single agreement along the lines of an Association Agreement. The UK and EU proposals for how to govern the agreement(s) is discussed below.

Governance and enforcement

Within each of the UK's proposed agreements, the UK government has included governance and dispute resolution arrangements. For example, the UK government has proposed a Joint Committee (along similar lines to the one created to oversee the Withdrawal Agreement) to oversee operation of the Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement along with a number of specialised committees to oversee matters such as Rules of Origin and Technical Barriers to Trade.

A Joint Committee is also proposed for managing the agreement on law enforcement and judicial cooperating in criminal matters.

For fisheries, the UK government has proposed that where there is a dispute, both parties should consult and further, both parties would have the right to suspend application of the agreement in the event of a dispute.

In contrast, the EU negotiating text, proposes one Partnership Council (which can meet in different configurations) along with a number of specialised committees to oversee operation of the one overarching EU-UK Agreement.

The two positions are not hugely different but are divided by the UK desire to negotiate a serious of individual agreements whilst the EU seeks one overarching agreement.

On enforcement of the Agreement, a key difference between the two sides concerns the role for the European Court of Justice. The EU negotiating text states that:

Concepts of Union law contained in this Agreement or in any supplementing agreement, or provisions of Union law referred to in this Agreement or in any supplementing agreement, shall in their application and implementation be interpreted in accordance with the methods and general principles of Union law and in conformity with the case-law of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

In contrast, the UK government has been clear that there should be no role for the Court of Justice in interpreting any elements of the Agreement.

A Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement

The UK's legislative proposals for a Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (CFTA) are covered in 34 chapters. The structure of the UK's CFTA proposals is set out below:

What is a free trade area? (Article 1.3)

National Treatment and Market Access for Goods (Chapter 2)

Rules of Origin (Chapter 3)

Trade Remedies (Chapter 4)

Technical Barriers to Trade (Chapter 5)

Sanitary and Phytosanitary measures (Chapter 6)

Customs and Trade Facilitation (Chapter 7)

Services and Investment (Chapter 8)

Cross Border trade in Services (Chapter 9)

Investment (Chapter 10)

Temporary Entry and Stay of Natural Persons for Business Purposes (Chapter 11)

Domestic Regulation of Services (Chapter 12)

Mutual Recognition of Qualifications (Chapter 13)

Telecommunications Services (Chapter 14)

Delivery Services (Chapter 15)

Audio-Visual Services (Chapter 16)

Financial Services (Chapter 17)

Digital (Chapter 18)

Capital Movements, Payments and Transfers (Chapter 19)

International Road Transport (Chapter 20)

Subsidies (Chapter 21)

Competition Policy (Chapter 22)

State Enterprises, Monopolies and Enterprises Granted Special Rights or Privileges (Chapter 23)

Intellectual Property (Chapter 24)

Good Regulatory Practices and Regulatory Cooperation (Chapter 25)

Trade and Sustainable Development (Chapter 26)

Trade and Labour (Chapter 27)

Trade and Environment (Chapter 28)

Relevant Tax Matters (Chapter 29)

Administrative Provisions (Chapter 30)

Transparency (Chapter 31)

Exceptions (Chapter 32)

Dispute Settlement (Chapter 33)

Final Provisions (Chapter 34)

The next section provides background on some of the key proposals in the UK government's proposed CFTA from a devolved perspective.

What is a Free Trade Agreement?

Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) are international agreements between two or more countries (or international organisations).

Primarily, FTAs increase the economic integration of its participants, making trade easier between them. An FTA typically provides that goods originating from a member FTA country are imported into other FTA countries without paying tariffs (custom duties). Therefore, goods from a member of the FTA enjoy privileged access to the other members' markets, compared to the treatment reserved to goods from non-FTA countries.

Outside FTAs, importing and exporting countries trade under the rules of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). WTO members have bound themselves to a maximum (capped) rate of tariff for each kind of goods, and must apply the same tariff rate to all imported goods irrespective of their origin. Because the WTO does not permit discrimination among trade partners, the capped tariff rate is referred to as Most-Favoured Nation (MFN) rate. The preferential treatment granted by a Free Trade Agreement is an exception to the principle of MFN treatment, because some countries are more favoured than others, due to their FTA membership.

MFN tariff v. preferential trade inside a Free Trade Area

Example 1: WTO law allows Canada to impose a custom duty of up to 8% on imported cigars. Instead, cigars from the EU enter the Canadian market at no duty, under the terms of the Canada-EU FTA (CETA).

Example 2: Honey is traded tariff-free across the EU, because the EU established a free trade area on its territory. However, honey imported from the US faces a tariff of up to 17.3%. Moreover, the EU grants tariff-free access to honey from dozens of countries, under free trade agreements or similar arrangements.

Example 3: Normally, cars imported into the EU incur a tariff at the border. Under the EU-Japan agreement, Japanese cars enter the EU market at no duty. Before the EU-Japan agreement, Japanese manufacturers could avoid duties by assembling the cars in the territory of the EU. Now, that arrangement is no longer necessary.

Tariffs are not the only trade barrier that Free Trade Agreements might remove. WTO law prohibits quotas and other quantitative restrictions of trade, but tariff-rate quotas exist and might be modified in favour of FTA partners.

Non-tariff barriers also exist in the form of domestic regulations, like sanitary requirements for foodstuffs or technical specifications for products: FTAs can create a system for the members to harmonise them, or recognise each other's rules as equivalent, to facilitate the circulation of goods.

Besides goods, FTAs often address trade in services, although they rarely secure concessions that are significantly higher than those already granted under the WTO. Under WTO law, states have exchanged promises to open their services markets to foreign services. The terms and extent of these promises change from state to state. Normally, FTA parties attempt to secure concessions in areas where there is no WTO commitment. For instance, a state that has made no promise regarding educational services under the WTO has no obligation to open its market to foreign providers (e.g. foreign universities willing to open a branch on its territory). In the framework of a bilateral FTA, the same state might offer preferential rights to educational services and providers from its trade partners.

Modern FTAs also provide states with an opportunity to agree on many matters that go beyond the removal of trade barriers. These matters can include policy areas that can have a direct influence on trade (for instance, veterinary checks, food safety standards, the protection of Geographical Indications) or areas that relate to overall economic policy (for instance, sustainable development, environmental protection and labour rights). For a more detailed overview of the typical sections of modern FTAs, in particular the EU agreements with Canada and Japan, see the SPICe briefing Anatomy of Modern Free Trade Agreements (2019).

What is a Free Trade Area? (Article 1.3)

Article 1.3 of the UK's CFTA draft negotiating text proposes a Free Trade Area between the UK and the EU. Free Trade Areas form a key component of any Free Trade Agreements (FTAs).

A Free Trade Area typically provides that goods originating from any participant country can move freely throughout the Area without paying tariffs (custom duties). Therefore, goods from a member of the FTA enjoy privileged access to the other members' markets, compared to the treatment reserved to goods from non-FTA countries.

In addition, in a Free Trade Area, tariff-rate quotas are removed entirely allowing unlimited quantities of goods to circulate within the free trade area tariff free.

Rules of Origin (Chapter 3)

In a Free Trade Agreement, only goods originating from within the participating countries circulate freely or under privileged conditions. Goods from third countries, instead, can incur custom duties. Therefore, customs authorities need to verify the provenance of goods, to identify the applicable treatment.

Rules of origin (RoO) are the rules used to identify where a good comes from, for that purpose. This might be a difficult determination, when imported goods contain components of various provenance and have undergone different processing stages in different places ("inputs"). For instance, a German car with a Korean engine and leather seats made in Italy contains "inputs" from these three countries, so there must be a system to decide whether it is a Korean car or not when it enters the UK.

RoO normally require a minimum percentage of a good’s inputs to come from a certain country to claim that origin. In a UK-EU free trade agreement, RoO would determine whether a good can be considered from the UK, and thus enjoy tariff-free access to the EU market. In addition, after the UK leaves the transition period, third countries will no longer consider UK inputs that went into the manufacturing of EU goods to count as an EU input. When the EU origin of the good is important to enjoy trade benefits (for instance, to obtain duty-free access into Japan, under the EU-Japan FTA), this change might incentivise manufacturers to replace the UK-based component with EU-based ones to retain the advantage.

"Cumulation" is the possibility to treat foreign inputs as originating from the exporting country, for the purpose of calculating that percentage. For instance, for a car to be "Japanese" under the RoO of the EU-Japan FTA, it must contain at least 55% of its inputs from the EU or Japan. A "cumulation" exception would allow input from a third country to count towards that qualifying percentage. A network of FTAs with similar RoO can create "cumulation zones"- group of countries allowing for cumulation of materials from any of them. The EU is currently part of the Pan-Euro-Med zone, including the EU, EEA countries, Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. Taking advantage of the cumulation rights of the Pan-Euro-Med has been crucial for industries, like textiles and confectionery, which process imported materials.

The UK draft text on Rules of Origin sets ambitious cumulation rights. In other words, it proposes that inputs from certain third countries will not foreclose the qualification of goods as originating from the UK, for the purpose of exporting to the EU and accessing the benefit of the new FTA.

Article 3.3, in particular, provides for the cumulation of inputs from the EU, developing countries covered by trade assistance programmes, and other countries with which both the UK and EU have an FTA, signed before the end of the transition period.

The cumulation of EU inputs is also granted in the EU proposal (see Article ORIGI.4.1). It would allow, for instance, to consider a car to have been made in the UK irrespective of whether it contained Italian leather seats and a German engine.

The request for cumulation of inputs from developing countries is unusual but not unprecedented: the EU grants it to Norway, Switzerland and Turkey, subject to certain conditions. Cumulation with third countries' inputs is not available under the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement.

The proposal to triangulate the cumulation of inputs from common FTA partners relates to those EU FTAs that the UK has "rolled-over" for itself. The UK has signed agreements with certain countries (for instance, South Korea and Chile) that largely reproduce the deals that those countries have with the EU. This provision, if accepted by the EU, would permit Korean inputs in UK goods to pass as a UK input at EU customs borders (both the EU and the UK have an FTA with South Korea). In contrast, as the UK has not "rolled-over" for itself the EU treaty with Japan, any Japanese input would not count towards the percentage required for UK origin.

The suggestion of triangular cumulation is particularly ambitious. The EU has used the Rules of Origin, currently proposed by the UK in previous agreements, for instance in its Comprehensive Economic Trade Agreement with Canada (see Article 3.8 of the Protocol on RoO and origin procedures). However, it has not signalled its intention to pass UK inputs for EU ones in its own FTAs. As a result, in the future, the EU is ready to accept that UK components will no longer count towards the EU origin of a good that seeks to benefit from the preferential treatment offered by FTA partners (like Canada and Japan).

As noted by an alert published by the law firm White & Case:

"... the EU's draft CPA text reveals that it will not seek diagonal/regional cumulation of origin in its existing or future FTAs with third countries, so that UK input materials would be counted as "originating" materials. This means that in the case of the EU-Japan FTA, Japanese materials used in UK production would not be "originating" materials for duty free entry into the EU. Likewise, for duty free export to Japan from the EU, UK parts would not count as originating for EU manufacturers"

Trade Remedies (Chapter 4); Subsidies and Competition (Chapters 21, 22)

Both the World Trade Organisation and individual Free Trade Agreements promote the liberalisation of free trade in goods, and prohibit measures that make trade more difficult or more costly. However, importing countries are allowed to impose limited restrictions to contain the flow of goods that are too cheap due to unfair trade practices like dumping and subsidised exports.

In the UK, the Government's ability to deal with unfair trade is of particular concern for industries such as steel and ceramics, which have suffered in the past from dumping — the sale of goods below the cost of production or home-market prices — by countries including China, Russia and Brazil.

Dumping is a private business practice: the sale of goods abroad for a price lower than their normal value on the domestic market. Subsidisation (State Aids) is public sector support to manufacturing, in the form of payments, tax rebates, low interest loans or other favours. When an imported goods’ price is artificially low because of dumping and/or subsidisation, the importing country can respond by imposing anti-dumping or anti-subsidy (countervailing) duties. These duties increase the imported goods’ price to the normal level – i.e., the level if the good had been unaffected by dumping or subsidies.

Trade remedies, in the EU, are managed by the European Commission on behalf of all EU Member States. In February 2019, the UK government announced that after the UK leaves the transition period, it will set up an autonomous trade remedies system, and will have to agree with trade partners on how to manage allegations of unfairness in their trade relations.

The UK government's proposed draft Free Trade Agreement does not contain special rules on trade remedies against subsidised and dumped goods. It simply refers to the existing WTO rules, and invites the EU and UK to cooperate in good faith when an allegation is made that dumping or distorting subsidies occurred.

Chapter 21 of the proposed Free Trade Agreement contains a set of minimal rules on subsidies - recalling the parties' commitment to respect the rules of WTO law. This is in stark contrast with the EU proposal that the UK would follow EU State Aid rules as part of a trade agreement.

Chapter 22 of the proposed Free Trade Agreement, on competition, is also brief and shows modest ambition. It confirms the parties' commitment to monitor, police and sanction anticompetitive behaviour, but does not attempt to define it precisely, to fix a common understanding. The EU proposal in contrast specified in great detail what kind of anticompetitive behaviour both parties should prohibit and sanction. Articles LPFS2.11 to 2.14 of the EU draft contain a virtual replica of the EU antitrust notions: abuse of dominant positions, cartels and anti-competitive mergers. The UK did not include such a list, suggesting it does not wish to keep close alignment to EU rules in its implementation of competition law, and thus reserving for itself the margin to decide what "anti-competitive business conduct" means in the future and possibly diverging from the law and practice of the EU.

The section on Level Playing Field, provides an explanation why trade remedies - in particular with respect to subsidies (State Aids) - remain a point of contention in the current negotiations.

Technical Barriers to Trade (Chapter 5)

Technical regulations can represent a trade barrier. For instance, voltage requirements for household appliances can limit their tradability across countries with different standards.

The World Trade Organisation agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) requires WTO members to enforce only technical measures that are necessary to pursue their goal, and encourages members to follow international standards.

Convergence towards common standards on safety, health and consumer protection, possibly produced by international standardisation bodies, can help eliminate unnecessary trade barriers. Alternatively, trading countries could mutually recognise each other's standards as satisfactory. In so doing, the importing country would spare the imported products from compliance with its domestic standards, as long as the standards of the country of origin are observed. Alternatively or in addition to that, the FTA members could recognise (accredit) the bodies that verify compliance with the required standards operating on the other member's territory, trusting goods coming with their certifications (known as mutual recognition). It is convenient if the importing country accredits an assessment body on the territory of the exporting one, so manufacturers can obtain the certification necessary to export more easily. For instance, as previously identified by SPICe, CETA favours this kind of solution:

CETA authorises the competent bodies of the EU and Canada to issue certifications based on the standards of each; for instance, the Canadian authorities could certify a product's compliance with EU standards. In so doing, exporters can apply for the required certification for their products at the place of production rather than the place of export.

Both the UK and the EU draft Free Trade Agreements do not expand significantly beyond what is already in the Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) agreement of the WTO.

Both parties have indicated a willingness to facilitate the accreditation of third country conformity assessment bodies in their territories, to make it easier for manufacturers in the UK and EU to obtain a certification of compliance with the standards of the export destination area.

The actual likelihood of removing TBT barriers, ultimately, depends on the similarity of the applicable standards to which the EU and the UK choose to adhere to in the future. The EU will likely retain its standards at least at their current level, so the critical question will be to see whether the UK will choose to adopt different standards - which after leaving the transition period it will be able to do. A change in UK standards may emerge to increase its chances of concluding other Free Trade Agreements, for instance with the United States. As a blog from the London School of Economics has argued, the nature of the EU-UK Free Trade Agreement will have a material effect on the impact of TBT:

Over time, technical barriers to trade would become more substantial if regulatory practices diverged, but this could be avoided if committed regulatory cooperation became institutionalised in a FTA. That is contingent on clear procedural measures and a commitment from both sides regarding regulatory approaches, an area where the EU’s negotiation position is considerably stronger. The EU is defending the regulatory status quo, and has historically had an extremely high preference for public safety standards over market access. Special treatment for the UK would be a departure from historical practice.

Sanitary and Phytosanitary measures (Chapter 6)

Sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures are measures to protect humans, animals, and plants from diseases, pests, or contaminants.

EU law includes detailed rules designed to reduce or eliminate such threats, and to reduce the chances of animal and plant diseases being introduced to the EU from non-EU countries. An updated regulatory framework for animal health will fully apply across the bloc from 21 April 2021.

The WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (the SPS agreement) is referenced in both the UK and EU negotiating texts. This is an agreement on how governments can apply food safety and animal and plant health measures in relation to the basic rules in the WTO. According to the WTO:

Article 20 of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) allows governments to act on trade in order to protect human, animal or plant life or health, provided they do not discriminate or use this as disguised protectionism. In addition, there are two specific WTO agreements dealing with food safety and animal and plant health and safety, and with product standards in general. Both try to identify how to meet the need to apply standards and at the same time avoid protectionism in disguise.

The WTO uses a number of standard-setting organisations to underpin the SPS agreement. These are:

FAO/WHO Codex Alimentarius Commission (for food);

FAO’s Secretariat of the International Plant Protection Convention (for plant health).

These are recognised in the UK negotiating position as the continued relevant authorities. However the UK's negotiating position as stated is to "build on" the WTO rules:

The SPS agreement should build on the WTO SPS Agreement in line with recent EU agreements such as CETA and the EU-NZ Veterinary Agreement. [..] The Agreement should reflect SPS chapters in other EU preferential trade agreements, including preserving each party’s autonomy over their own SPS regimes.

The document further sets out that the agreement should include recognition of both parties' health and pest status, and that trade can continue from certain geographical areas of the territory of each and either party in the event of disease and pest outbreaks elsewhere in that territory.

The UK negotiating position is that audit of each other's SPS controls will be necessary, as will a requirement to notify each other in the event of any emergency SPS measures. In addition, the UK believes the Agreement should outline the checks and fees which agrifood commodities will be subject to at the border - and that certain commodities should be subject to reduced levels of checks (the UK argues this is in line with CETA and the UK-New Zealand Veterinary Agreement).

On antimicrobial resistance (when the organisms that cause infection evolve ways to survive treatments) the UK position is that there should be a framework for UK-EU dialogue.

The UK government draft free trade agreement states that the objectives on sanitary and phytosanitary measures are to:

(a) protect human, animal and plant life or health, and the environment while facilitating trade;

(b) further the implementation of the SPS Agreement;

(c) ensure that the Parties’ sanitary and phytosanitary measures do not create unjustified barriers to trade;

(d) promote greater transparency and understanding on the application of each Party’s SPS measures;

(e) enhance cooperation between the Parties on animal welfare and on the fight against antimicrobial resistance;

(f) enhance cooperation in international standard-setting bodies to develop international standards, guidelines and recommendations on animal health, food safety and plant health, including international plant commodity standards; and

(g) promote implementation by each Party of international standards, guidelines and recommendations.

The Annexes to the UK draft free trade agreement include that:

Audits and inspections shall concentrate primarily on evaluating the effectiveness of the official inspection and certification systems as well as the capacity of the exporting Party to comply with the sanitary and phytosanitary import requirements and related control measures rather than on specific establishments in order to determine the ability of the exporting Party's competent authorities to have and maintain control and deliver the required assurances to the importing country.

Detail on the EU's position can be found in Chapter 3 of the Draft text of the Agreement on the New Partnership with the United Kingdom.

Ireland/Northern Ireland

Under the terms of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland the new EU regulatory framework for animal health (the 'Animal Health Law') will apply in Northern Ireland from 21 April 2021, but will not apply in Great Britain (where the default is to be the current EU regulatory framework, enshrined in the UK as EU retained law).

The UK Government's proposal for implementing the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol provides further detail on how the UK government intend to implement SPS measures on agri-food and livestock movements from Great Britain to Northern Ireland.

Provisions in relation to services (Chapters 8, 9)

World Trade Organisation law governs trade in services, but the rules of the WTO's General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) do not establish a standard set of obligations. Trade in services is not hindered by tariffs, but by laws and regulations on the provisions of services. These regulations can restrict the ability of a person not resident in a country to provide services in the importing country. It is for each country to decide to what extent it wishes to liberalise its services market, and in which sectors (health, education, banking, etc).

FTAs build on this set of customised commitments and expand the FTA parties' liberalisation obligations in favour of foreign services and service providers. Normally, FTAs do not secure across-the-board liberalisation in services, and contain only a modest improvement compared to the GATS baseline, relating to specific services.

In the area of provision of services, the EU's proposal aims to build gradually on existing levels of openness under WTO rules, whilst ensuring Member State governments continue to retain their right to regulate in this sector. In practice, the EU draft contained a prohibition against discrimination of foreign services and service providers, rules on the temporary entry and stay of workers, and a prohibition against performance requirements (that is, restrictive conditions on the activity of foreign providers). It also sought to promote the mutual recognition of certain professional qualifications. The EU also wished to exclude audio-visual services from the FTA.

The UK approach is to seek an agreement on trade in services and investment at least as good as the EU's existing FTAs. The UK negotiating text envisages regulatory cooperation across a wide range of services sectors and proposes that trade liberalisation could go further in areas like professional and business services - a UK strength. The UK government's identified services priorities include digital trade, temporary business travel for natural persons, and a pathway to mutual recognition of professional qualifications. The UK government has also sought to include audio-visual services.

The current negotiations on services largely focus on the issue of financial services, on which there is a dedicated chapter in this update. On other issues, the UK Chief Negotiator David Frost raised concerns the level of concessions offered by the EU in his recent letter to EU Chief Negotiator Michel Barnier:

In services, the EU is resisting the inclusion of provisions on regulatory cooperation for financial services, though it agreed them in the EU-Japan EPA. The EU’s offer on lengths of stay for short-term business visitors (Mode 4) is less generous than CETA, and does not include the non-discrimination commitment found in EU-Mexico. The EU has also not proposed anything on services which reflects the specific nature of our relationship: indeed your team has told us that the EU's market access offer on services might be less than that tabled with Australia and New Zealand.

Trade in Financial Services (Chapter 17)

For companies based in EU countries, it is relatively easy to operate anywhere across the Union. For instance, banks can open a branch abroad (rather than establishing a separate subsidiary) and apply for permission to provide services without much difficulty, thanks to the so-called passporting system. EU countries have signed up to a common rulebook for financial services, and this observance of common rules entitles their companies to get a passport to operate anywhere in the EU.

Non-EU banks and financial institutions cannot rely on “passporting.” Third country operators can do business in the EU only if the EU regards their home regulatory standards as satisfactory, through a test of "equivalence."

The EU conducts a test of “equivalence” of the modes of regulations and supervisions of other countries. The outcome of that assessment allows a decision on whether it will authorise (or not) the financial services operations of providers from that country. These unilateral equivalence decisions can always be withdrawn at short notice. There are around 40 equivalence decisions to make in this sector (referring to different financial products, operations and concerns). The UK has also established a parallel system to make equivalence determinations in the future.

The UK in the past has made demands that it should benefit from a privileged “equivalence” status, in light of its long-standing record of compliance with EU rules. However, EU authorities are likely to exercise caution in the granting of expedited or automatic equivalence.

On 27 February 2020, the UK Government's Chancellor Rishi Sunak wrote to the European Commission, providing assurances that for the UK government, the equivalence assessment could be completed by the end of June 2020, and inviting the EU to move in a similarly expedited way:

At the end of the transition period, the UK and EU will start from a position of regulatory alignment. The UK and the EU should be able to conclude equivalence assessments swiftly and I see no reason why we cannot deliver comprehensive positive findings to the June timeline.

In response, the Commission's executive vice-president Valdis Dombrovskis simply stated that the EU, was “mapping the equivalence areas internally” and that the “equivalence assessment will have to be forward-looking, taking into account of overall developments, including any divergences of UK rules from EU rules”.

In its draft FTA published in March 2020, the EU has proposed not to grant specific treatment to the UK with respect to financial services. While committing to remove all forms of discrimination and trade restrictions, it left the "equivalence" system in place, and provided no fast-track for UK operators.

Conversely, the UK draft treaty contains an entire chapter dedicated to trade in financial services. The UK text makes ambitious demands relating both to market access to the EU and the conditions for mutual recognition. It also establishes a novel bilateral Financial Services Committee to supervise the conduct of the UK and EU in this area.

On the access of UK services and firms to the EU market, the UK text requires each party to allow the provision of services that do not require the physical presence of the foreign supplier on the other's territory. This means that the cross-border provision of financial services shall always be permitted (e.g., the provision of financial advice by a UK consulting firm to an Italian client, which does not require the UK provider to open an office in Italy).

The draft text states that each party:

shall permit persons located in its territory, and its nationals wherever located, to purchase financial services from cross-border financial service suppliers of the other Party located in the territory of that Party” without the need for each country to "permit such suppliers to do business or solicit in its territory (Article 17.3.2).

Conversely, Chapter 11 (on temporary movement of persons for business) grants the right for individuals to visit the territory of the other in pursuit of financial services products. For instance, an Italian client should be allowed to travel to London to purchase the services of an English consultant.

With respect to new financial services, the UK text is more generous than the EU one, as it removes the condition that foreign service suppliers entitled to provide a new service should already be established in the foreign jurisdiction.

The UK text also includes a provision that seeks to spare the “performance of back-office functions” carried out in one party from the regulation of the other party:

While a Party may require financial service suppliers to ensure compliance with any domestic requirements applicable to those functions, they recognise the importance of avoiding the imposition of arbitrary requirements on the performance of those functions.

The draft text does not mention expressly the demand for automatic or enhanced equivalence for UK suppliers. In this respect, it seems that the UK has given up the demand to obtain a preferential access to equivalence. Rather, it seems to focus on the removal of uncertainty in the management of equivalence assessment procedures.

The UK draft establishes a new Financial Services Committee, which should supervise and facilitate cooperation between the UK and the EU, limit the use of exceptions and provide a forum to discuss equivalence decisions.

In addition, the UK proposal provides that the parties shall maintain a dialogue aimed at establishing close regulatory cooperation. This cooperation would contribute to achieving, among other things:

transparency and appropriate consultation in the process of adoption, suspension and withdrawal of equivalence decisions; and

consultation and information exchange on regulatory initiatives and other issues of mutual interest.

In so doing the UK government, while accepting that equivalence recognition would be the framework within which the parties’ suppliers would need to operate, tried to introduce a process of “structured” concession, suspension and withdrawal of equivalence decisions.

The gulf between the EU and UK position is wide, but it is narrower than before. There are no longer talks of introducing a co-decision process of equivalence, or to get a fast-track equivalence treatment.

Ultimately, the EU insists that in all respects financial services are just a kind of services, and the UK is a third country. There might be margin for obtaining more from the EU during the negotiations. In particular, a system of cooperation and consultation on regulatory matters, inspired by the EU-Japan agreement.

Whilst the UK government has tried to secure market access for the cross-border sale of services, and for consumption of services abroad, on regulatory matters, it has withdrawn more ambitious demands and tried to build a structure of governance to limit the risk related to the unilateral management of equivalence decisions by the EU.

In summary, the EU and UK approaches to financial services have been described in the following way:

The EU intends to retain the existing architecture and restrictions of financial services, and contends that any market access should be granted by either side unilaterally in its own interests. The UK proposes establishing a unique legal and governance arrangement and allowing mutual free market access under that arrangement.

Intellectual Property (Chapter 24)

From a devolved perspective a key element of the UK government's proposals on Intellectual Property relate to its proposals on geographical indications which is addressed in sub-section 3 of Chapter 24.

The EU has perhaps the most developed approach to GIs in the world in contrast to countries such as the United States which operates a system based on trademarks rather than GIs. The European Commission describes a GI as:

a distinctive sign used to identify a product as originating in the territory of a particular country, region or locality where its quality, reputation or other characteristic is linked to its geographical origin.

At present, UK food products are part of the EU Protected Food Name Scheme and covered by the European Regulation for the protection of geographical indications of spirit drinks. Examples of Scottish protected food names include Scotch Lamb, Scottish Farmed Salmon, Scottish Wild Salmon and Stornoway Black Pudding.

More information on Geographical Indications is provided in the SPICe Briefing Geographical Indications and Brexit.

The Withdrawal Agreement sets out arrangements which mean existing UK GIs will continue to be protected by the current EU system "unless and until" it is superseded by the future economic relationship . In the same way, EU GIs will remain protected in the UK under the same conditions.

The UK Government's draft legal text proposes only that the terms in relation to geographical indications will supersede the terms set out in the Withdrawal Agreement. It then states proposals will be proposed.

This approach leaves open the possibility that the UK Government might seek to remove the recognition of current EU GI's in the UK as part of the new future relationship. If this is to be the case, it contrasts markedly with the EU's approach which seeks to protect the current system of GIs and "establish a mechanism for the protection of future geographical indications ensuring the same level of protection as that provided for by the Withdrawal Agreement.".

Level playing field issues (Chapters 26-28)

The notion of the Level Playing Field (LPF) suggests that companies across the territory of the Free Trade Agreement should observe comparable standards of environmental protection, labour rights and social responsibility. Compliance with these standards is usually expensive, and a company that could avoid them would save on costs and have an unfair advantage on its foreign competitors.

Moreover, LPF provisions also concern the kind of financial support that producers can receive lawfully from a public sector organisation. For instance, if a government could provide its producers with unlimited State Aids or subsidies, their goods would be cheaper to produce as a result, and could enjoy an unfair competitive advantage abroad. In a recent speech, the European Commission President summarised the scope of LPF:

Without a level playing field on environment, labour, taxation and state aid, you cannot have the highest quality access to the world’s largest single market. The more divergence there is, the more distant the partnership has to be.

In the draft Free Trade Agreement published by the UK government, LPF rules are included across a number of elements of the treaty, as they concern both production standards (environment, labour, human rights) and State intervention (subsidies, competition).

In general, the UK text has few provisions on State intervention, which largely consist of reference to existing multilateral rules, and are not subject to the dispute settlement system (see Trade Remedies and Competition). The draft treaty contains no approach to government procurement and limited commitments on State Aid.

Conversely, the rules on regulatory standards are largely inspired by the EU trade agreements with Canada, Korea and Japan. Chapters 26 to 28 of the UK negotiating text relate to certain regulatory standards that the parties commit to observe, in the field of sustainable development, the environment and labour conditions.

Chapter 26 on Trade and Sustainable Development serves as an umbrella for the following two chapters, and notes that “the rights and obligations under Chapters 27 and 28 are to be considered in the context of this Agreement”. In a trade agreement, the language is typically the other way round: economic provisions should be interpreted bearing in mind societal interests.

Chapter 26 contains no obligations. It institutes a Committee on Trade and Sustainable Development, to oversee implementation of Chapters 27 and 28.

Chapter 27 on Trade and Labour contains only a very tentative promise, with no binding force:

Recognising the right of each Party to set its labour priorities, to establish its levels of labour protection and to adopt or modify its laws and policies accordingly in a manner consistent with its international labour commitments, including those in this Chapter, each Party shall seek to ensure those laws and policies provide for and encourage high levels of labour protection and shall strive to continue to improve such laws and policies with the goal of providing high levels of labour protection.

The text is in line with the language of the EU's trade Agreements with Canada, South Korea and Japan.

This proposed provision falls short of a binding non-regression clause and does not provide a promise to keep alignment either. The UK Government's proposal also requires the parties to ensure that their laws reflect their international obligations, most importantly under the Conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO) Whilst there is an obligation to maintain and enforce the standards set in domestic law there is no commitment to non-regression or the possibility of amending the law to increase or reduce standards.

In terms of dispute resolution, the UK government text provides that when one party believes that the other has breached the obligations in terms of trade and labour, a consultation process is established and a Panel of Experts assembled to hear the dispute if necessary. Whilst the the Panel can issue recommendations these would not be binding.

Chapter 28 on Trade and Environment is also closely modelled upon its CETA counterpart (Chapter 24). It follows the same structure of Chapter 27 and includes commitments on the importance of environmental protection and on observing existing international obligations. There is also a commitment to continue to apply current laws.

As under the previous chapter, in the case of a dispute, a Panel may hear the dispute and issue non-binding recommendations.

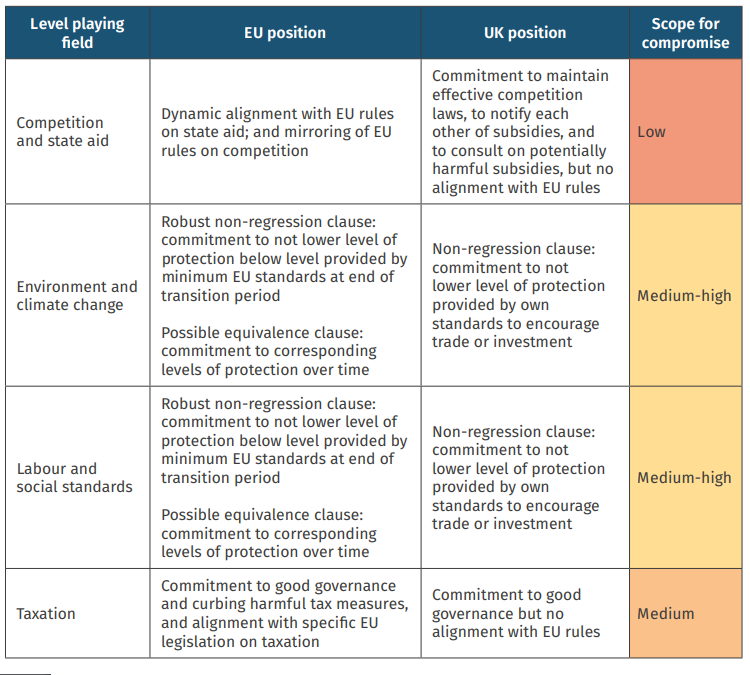

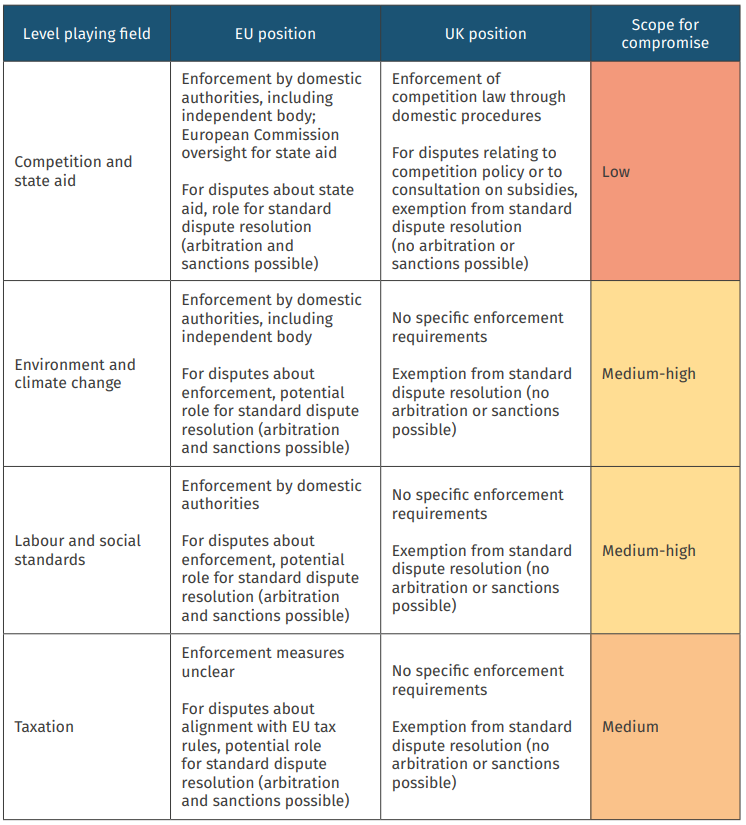

An illustration of how these provisions compare to the proposals made by the EU in March, is provided in the tables below. The first table addresses the rules proposed and the second table addresses the enforcement systems.

The UK draft text reflects the government’s announcements that it would seek basic LPF provisions, in line with those seen in the EU agreements with Japan, Canada and Korea. Apart from the atypical exclusion of the rules on government procurement, there is nothing unusual in these draft proposals.

However, based on its negotiating position and draft text, the EU will probably consider these proposals unsatisfactory. The EU is on record requesting strong commitments on State Aids, using EU law as a reference. There are no such commitments in the UK draft text. The EU also insisted on strong regulatory commitments regarding labour and environmental standards, supported by an enforcement mechanism that could authorise the imposition of sanctions or the raising of tariffs. Again these provisions are not present in the UK Government's proposals.

Whilst the EU position in relation to LPF is reminiscent of the rules of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement which takes into account the close geographic relationship between the parties, the UK Government has sought to replicate the LPF texts in the EU's deals with Canada and Japan for example.

Fisheries agreement

What does the draft agreement do?

The UK government's Draft Framework Agreement for Fisheries sets out a proposed fisheries agreement between the EU and the UK. After the transition period ends on 31 December 2020, the UK will no longer be party to the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), and new agreements on fisheries management will need to be reached with the EU and with other coastal states.

The Draft Fisheries Framework Agreement (DFFA) largely reflects the UK government’s original negotiating priorities set out in February 2020. It is published alongside, but separate to, a Draft UK-EU Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (CFTA). Publishing a DFFA as a supplementary to a CFTA is in line with the UK government's original position. Conversely, the EU view is that fisheries should form part of an overall economic agreement. The Draft Agreement proposed by the EU on 18 March 2020 includes fisheries as part of this agreement.

The EU’s Draft Agreement looks different to the DFFA in some significant ways, and it also looks different to the original text of EU fisheries agreements with other coastal states, namely Norway and the Faroe Islands, which have some similarities with the DFFA. These similarities and differences are discussed below. However, it is important to remember that the original agreements between the EU and Norway and the EU and the Faroe Islands were published several decades ago, and working practice, examples of which is mentioned below, may go beyond what was set out in the original agreement.

In broad terms, the DFFA proposes that the current arrangements on determining fishing opportunities will end and that “in line with the UK's commitment to best available science, future fishing opportunities should be based on the principle of zonal attachment (See Box 1).

Box 1 – Zonal Attachment

Zonal attachment refers to the idea that total allowable catch should be allocated based on the temporal and spatial distribution of stocks, rather than historical catches. There is no single method for determining zonal attachment, though the UK Government’s fisheries white paper, Sustainable Fisheries for Future Generations (July 2018) has set out preliminary research for how this might be calculated.

The text of the DFFA outlines the basis for future cooperation on fisheries management between the UK and the EU. It proposes that:

Negotiations to determine TAC and access are carried out annually. Under the CFP, negotiations on Total Allowable Catches (TAC) take place annually at the EU December Council. The DFFA proposes that the annual negotiations take place at the same time as other negotiations which affect both parties. A SPICe blog series explores this current process in more detail.

The division of fishing opportunities between parties is also determined annually based on the principle of zonal attachment. This is in contrast to how opportunities are allocated under the CFP. Under the CFP, once TAC is agreed at the December Council, quota is allocated based on the principle of relative stability, where member states’ share of the TAC is fixed based on historic landings.

Fishing opportunities could be changed as part of annual negotiations based on changes in scientific evidence, unforeseen circumstances, or to correct errors.

In addition, the UK's DFFA sets out new proposed working arrangements on fisheries between the UK and the EU, including:

Reciprocal licence requirements to be able to fish in each other's waters, and outlines the responsibility of the flag state to ensure that vessels comply with rules in other countries’ waters;

Arrangements for independent fisheries management, including a responsibility to notify the other party of any new fisheries management measure;

Creation of a new Fisheries Cooperation Forum - “for discussion and co-operation in relation to sustainable fisheries management, including monitoring, control and enforcement.” The forum is proposed to be up and running by 1 January 2021, and could be open to other coastal states on agreement of the parties;

Data sharing, of data from vessel management systems (VMS) for the purpose of preventing illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing, monitoring and enforcement, managing fisheries sustainably, developing marine and fisheries policies, etc;

Designation of Ports in line with the North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission Scheme of Control and Enforcement (Article 21) and other relevant UK and EU legislation, for the purpose of preventing illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing;

Dispute resolution: Parties agree to consult with each other on how the agreement should be implemented, and to resolve any disputes;

Suspension of the agreement: The agreement can be suspended if Parties disagree on its implementation or if one party fails to comply with the agreement. Notification in writing from the concerned party starts a three-month process where Parties must endeavour to find an amicable settlement;

Amendments to the agreement can be consulted on and agreed between the Parties.

How does this compare to other EU fisheries agreements with independent coastal states?

The UK Government has emphasised that it is seeking a fisheries agreement like that between other independent coastal states and the EU, notably Norway and the Faroe Islands. In the DFFA, the UK Government makes reference to the EU's agreements with both countries.

EU-Norway Agreement

The EU-Norway agreement does take a similar shape to the one put forward by the UK Government. The EU-Norway agreement provides for:

Annual negotiations on TAC, quota allocations, and on access. Each party has a right to determine how many vessels of the other party will be allowed to fish in its waters, and how TAC is granted to those vessels.

Arrangements for fishing opportunities to be adjusted if necessary to respond to unforeseen circumstances.

Each party to establish measures for conservation and rational management of fisheries.

The need for consultation in the event of a disagreement or failure to comply with the agreement, and provisions for terminating the agreement.

Licensing by each party for the other party’s vessels.

The need to comply with parties’ respective regulations.

Cooperation between the two parties on management and conservation of living resources, including scientific research with regard to shared stocks.

However, there are some specific differences:

Annual negotiations on quota allocations: The EU-Norway agreement does not explicitly mention the principle of zonal attachment as the basis for allocating fishing opportunities to each party. Rather, the basis within the EU-Norway Agreement is reaching a “mutually satisfactory balance in their reciprocal fisheries relations”, subject to the conditions in the Annex. A comparison of the text of both agreements is provided below.

| EU-Norway Agreement | UK-EU Draft Fisheries Framework Agreement |

|---|---|

Article 2

| Article 1

|

The Annex of the EU-Norway agreement stipulates that:

1 . In determining the allotments for fishing under Article 2 ( 1 ) (b) of the Agreement, the Parties shall have as their objective the establishment of a mutually satisfactory balance in their reciprocal fisheries relations. Subject to conservation requirements, a mutually satisfactory balance should be based on Norwegian fishing in the area of fisheries jurisdiction of the Community in recent years. The Parties recognize that this objective will require corresponding changes in Community fishing activity in Norwegian waters.

2 . Each Party will take into account the character and volume of the other Party's fishing in its area of fisheries jurisdiction, bearing in mind habitual catches, fishing patterns and other relevant factors.

As such, an element of historical fishing patterns was included as part of reaching a “mutually satisfactory balance” in the original agreement. In practice more recently, the principle of zonal attachment has played a part in determining fishing opportunities between the EU and Norway. However, in relation to EU-UK fisheries relations Barnes et al. note in a blog for the London School of Economics that:

Zonal attachment is used in the EU Norway agreement, but would need to be developed for a much wider range of species in any EU-UK agreement. It is also highly vulnerable to changes in stock distribution from factors like climate change – something that has already effected the distribution of key species like cod. What establishing a new principle of zonal attachment would mean for devolved administrations seeking their ‘fair share’ must also be handled with care.

Agreeing a methodology for how zonal attachment should be calculated will also be complex as it may also have to take into account different stages of the life cycles of stocks of interest to each party. A recent article by the Institute for Government explains this problem:

[zonal attachement] rarely gives a precise answer to the question of what fish belong where – which is perhaps why the EU and Norway, which have claimed to apply the zonal attachment principle for four decades, have never disclosed the exact methodology behind their calculations. Imagine a herring which is spawned in Norwegian waters, spends some time off the Dutch coast, and then is eventually caught in the UK’s EEZ. Which zone should it be counted under?

In addition, provisions on annual negotiations and quota allocations also differ between the EU Draft Agreement on the future relationship between the UK and the EU, and the DFFA. Prof James Harrison notes in a contribution to the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee’s enquiry on the future relationship negotiations that, while both texts recognise the role of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) in setting evidence-based TAC/quota:

Where the two texts differ is on the details of the process and the ultimate objectives [for setting TAC/quota for shared stocks]. In this respect, the EU’s draft text would seem to be more sophisticated, as it embeds the objective of MSY and the precautionary approach into the objectives of the fisheries agreement and it also calls for the development of long-term strategies for the sustainable conservation and management of shared stocks. Whilst the text does not commit either party to the adoption of such strategies, it nevertheless emphasises the need for a long-term approach to fisheries conservation and management which is to be welcomed and mirrors the approach taken by the EU with other coastal states in the North-East Atlantic. The EU text also sets deadlines for decisions to be made and default rules if no agreement is forthcoming.

While such long-term strategies are not included in the EU-Norway agreement as it was drafted, Prof Harrison points to the Agreed Record of Fisheries Consultations Between Norway and the European Union for 2020, which refers to the development of such joint EU-Norway long-term management strategies.

Fisheries management measures: Where both the EU-Norway agreement and the UK's draft agreement state the right of each party to take measures to ensure fisheries management, the EU-Norway agreement specifies that any measure should “take into account the need not to jeopardise the possibilities for fishing allowed to fishing vessels of the other Party”, while the UK-EU DFFA requires that each part “shall notify” the other of any changes that would affect the vessels of the other party.

Similarly, the DFFA differs from the EU Draft Agreement on the future relationship between the UK and the EU in relation to fisheries management measures.

While the EU draft agreement also requires parties to notify the other of any changes, the approach taken in the EU-Norway agreement is echoed in the EU draft agreement where the EU proposes that any changes to technical measures must be “proportionate, non-discriminatory and effective to attain the objectives set out in Article FISH.1” The EU also propose consultation in the event that “the notified Party considers that these draft measures are liable to adversely affect its fishing vessels”. This goes beyond the UK’s proposal of simply notifying the other party, as discussed in section 2.1.2. Professor James Harrison expands on these differences in his contribution to the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee’s enquiry.

EU-Faroes Agreement

The EU-Faroes agreement is not dissimilar to the EU-Norway agreement, but differs in how quota allocations are agreed. Similar to the EU-Norway agreement, it strives to allow a “satisfactory balance” between the parties’ fishing possibilities, however:

In determining these fishing possibilities, each Party shall take into account :

(i) the habitual catches of both Parties,

(ii) the need to minimize difficulties for both Parties in the case where fishing possibilities would be reduced,

(iii) all other relevant factors.

The EU fisheries agreements with both Norway and the Faroe Islands are explored further in a SPICe briefing on the future relationship between the UK and EU on fisheries.

Energy and climate change agreement

The UK policy framework for energy and climate change is complex, and Scottish programmes and devolved responsibilities overlap significantly with those reserved to the UK, all within the context of EU and international agreements.

In relation to electricity, there is a GB market and an Integrated Single Market in Ireland (known as I-SEM). Established by parallel legislation in Westminster and the Irish Parliament, I-SEM is a wholesale market with a common set of rules, underpinned by a Memorandum of Understanding between the two governments. A joint regulatory body, the Single Electricity Market Committee, was established to oversee market arrangements.

Devolved and reserved responsibilities

Broadly, energy matters are reserved under Schedule 5 Head D of the Scotland Act 1998. The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) is responsible for UK Energy Policy including national and international trading of both gas and electricity. The Scottish Government has responsibility for the promotion of renewable energy, energy efficiency, and the consenting of electricity generation and transmission developments.

The Scottish Government has responsibility for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to climate change, and the Scottish Parliament has recently legislated for a target of net-zero emissions by 2045. This target sits within the wider UK target of reducing emissions to net-zero by 2050 which, the Committee on Climate Change says, "will deliver on the commitment that the UK made by signing the Paris Agreement". This universal and legally binding agreement sets out a framework to limit global warming to well below 2°C and to pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5°C.

Scotland therefore has a part to play in helping the UK meet global climate change targets, however it is the UK that is the individual signatory to the Paris Agreement, and the member of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Climate change

The UK does not address climate change within its proposals for a comprehensive free trade agreement. Instead climate change and carbon trading are included under the proposed agreement on energy.

In short - the UK proposes that the parties reaffirm their commitments under the Paris Agreement, and is open to considering a link between any future UK emissions trading system (ETS) and the EU ETS, subject to certain conditions.

Key provisions in the Draft Working Text for an Agreement on Energy include:

Each Party retains the right to establish its own climate change priorities, and to adopt or modify its laws and policies accordingly in a manner consistent with international climate change agreements to which it is a party and with this Agreement.

Each Party shall seek to ensure that those laws and policies provide for and encourage high levels of climate protection, and shall strive to continue to improve such laws and policies and their underlying levels of protection.

The Parties recognise that enhanced cooperation is an important element to advance the objectives of this Agreement, and shall cooperate on issues of common interest, in areas such as:

Trade and climate policies, rules and measures contributing to the purpose and goals of the Paris Agreement and the transition to low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development

Trade related aspects of the current and future international climate change regime, as well as domestic climate policies and programmes relating to mitigation and adaptation, including issues relating to carbon markets, ways to address the adverse effects of trade on climate as well as means to promote energy efficiency and the development and deployment of low carbon and other climate friendly technologies

trade and investment in renewable energy and energy efficiency goods and services.

In relation to carbon pricing and ETS, the UK highlights Switzerland's recent linking with the EU ETS (albeit after 10 years of negotiation). The Draft Working Text allows for additional legal provisions on carbon pricing to be inserted following further discussions, and states:

Any such agreement would need to recognise both parties as sovereign equals with our own domestic laws. It could: (a) provide for mutual recognition of allowances, enabling use in either system; (b) establish processes through which relevant information will be exchanged; and (c) set out essential criteria that will ensure that each trading system is suitably compatible with the other to enable the link to operate.

The EU proposes that the future relationship promotes "adherence to and effective implementation of "the Paris Agreement and considers "the fight against climate change" to be an "essential element of the envisaged partnership", as well as within their Level Playing Field provisions. The EU would require the UK to implement a system of carbon pricing of at least the same scope and effectiveness of, and possibly linked to, the EU ETS.

Energy

Britain’s electricity market currently has 4GW of interconnector capacity:

2GW to France

1GW to the Netherlands

500MW to Northern Ireland

500MW to the Republic of Ireland

There are two gas interconnector pipelines running from the EU to the British mainland:

The UK-Belgium interconnector has an import capacity of 25.5 billion cubic metres a year, and is bi-directional. The direction of flow depends on supply and demand and relative prices.

The UK – Netherlands pipeline is uni-directonal and has an import capacity of 14.2 billion cubic metres a year.

The UK is open to an agreement with the EU covering energy trading over these interconnectors.

Key provisions in the Draft Working Text for an Agreement on Energy include:

The establishment of a framework for consultation and dispute resolution, including the use of a Panel of Experts.

Recognition of the importance of cooperation and coordination between regulatory authorities, and promotion of the integrity and transparency of wholesale electricity and natural gas markets and the curtailment of insider trading and market manipulation.

Ensuring maximum levels of capacity in gas and electricity interconnectors and transmission networks, consistent with relevant safety standards.

Endeavouring to avoid barriers to cross-border trade in electricity and gas.

Consultation and coordination on electricity interconnector developments.

Cooperation between regulatory authorities, Transmission System Operators (TSOs) and other competent authorities on cross-border trade in electricity and security of supply.

UK TSOs may participate in existing EU systems allowing for compensation due to transmission losses, and no network charges on trade across interconnectors.

Participation as observers in meetings of the European Network of Transmission System Operators and the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators.

Cooperation to facilitate the cost-effective deployment of offshore wind and electricity interconnection and the development of hybrid projects linking offshore windfarms with interconnectors.

Establishment of an Energy Cooperation Group composed of relevant representatives, and chaired by a UK Minister and Member of the European Commission. The group will administer this Agreement, and ensure its proper implementation.

On electricity and gas trading, the EU states clearly that the UK will leave the Internal Energy Market. Under the Level Playing Field provisions, the EU requires a commitment to non-regression of "climate protection" measures including emissions from industrial installations, transport, land use, forestry and agriculture.

Existing trading agreements

There are no other countries that have energy relationship models with the EU that are directly comparable with what is being sought by the UK.

In January 2018 the House of Lords EU Committee published its report on Brexit and Energy Security, and noted that:

[...] the ‘Norway model’ would bring benefits to the UK in terms of energy security, but that it is contingent upon membership of the EEA and EFTA, which the Government has ruled out.

The "Swiss model" was also considered by the Committee, where the UK could gain access to European energy markets through multiple bilateral treaties, as Switzerland has achieved.

Switzerland sits physically at the centre of the EU energy system, has 40 interconnectors, and extensive water reserves which provide controllable low-carbon hydro power for grid balancing services. Switzerland accepts the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice, and can therefore maintain its place in the Internal Energy Market despite being a third country.

The Committee quotes His Excellency Jean-Christophe Füeg, Head of International Energy Affairs at the Swiss Federal Office of Energy:

The EU wants to have an internal electricity market as one coherent thing, and either you are in it and abide by the rules or you are not in it. For an exception to be made, you have to have a very strong case that you as a country bring something to the internal electricity market that is indispensable to the functioning of the energy market... I am not aware of the UK having anything that I would call a unique selling point; that is, something that you would bring to the Internal Energy Market, both electricity and gas, which in the countervailing scenario of you not bringing it to the market would put the Internal Energy Market in some sort of jeopardy

Conversely, the Minister, Richard Harrington MP, highlighted three features unique to the UK:

The first is bulk—our size relative to the Swiss and, therefore, our importance to the Single Market. The second is history—the fact that we helped to form it. Thirdly, there is the fact that we are already in it, unlike the Swiss, who are not.

The Committee concluded that:

The Swiss experience shows that mutual benefits and a history within the system are no guarantee of EU energy market access. While the Government appears confident that a post-Brexit energy relationship with the EU will favour the UK, we are concerned that this confidence is based on a misplaced expectation of pragmatism and that broader political considerations may affect the degree to which the UK can engage with the IEM post-Brexit.

The EU is clear that:

In the area of electricity and gas, there is no precedent for this type of arrangement.

Other agreements also exist, notably the Energy Community, a multilateral framework between nine Southeast and East European countries and the EU to integrate their energy markets. However, the key objective of the Energy Community is to extend the EU internal energy market rules and principles beyond on the basis of a legally binding framework called the Energy Community Acquis.

Social security coordination agreement

The UK's draft text on social security is much more limited in scope than either the current rules or the EU’s proposed draft text. It is also more limited than many bilateral agreements on social security between the UK and other countries.

What is social security co-ordination?

The EU's social security co-ordination rules protect certain social security entitlements and give access to healthcare when people move between states. They do this by, for example, ensuring that contributions made in one state can be used towards claiming benefits in another state, allowing someone to claim benefits when living in another country (exportability of benefits), and preventing 'double payments' by ensuring that people only pay contributions in one country. The rules set out basic principles, including non-discrimination in access to benefits and co-operation between states in administering the co-ordination rules.

The main rules are contained in Regulation EU 883/2004.i This covers a wide range of benefits including some devolved social security: carer’s benefits, some disability benefits, industrial injuries benefits and winter fuel payments. They mean, for example, that a person moving from the UK to an EU country can continue to receive carer’s allowance.

The coverage of healthcare includes necessary health care for temporary visitors, planned cross-border healthcare, and health care for people who have moved abroad. The cost of healthcare is fully re-imbursed by the 'competent'ii state.

Who will the new agreement apply to?

The UK's proposed agreement would apply to rights not protected under the Withdrawal Agreement. Very broadly, that is people who move between states after the end of the transition period.

The political declaration (17 October 2019) stated that:

The parties will also agree to consider social security co-ordination in the light of future movement of persons. (para 52)

Under the Withdrawal Agreement, certain cohorts of people - broadly those people who have already moved and who move before the end of the transition period, are covered by existing co-ordination rules:

no matter what the future relationship covers or whether a future relationship is agreed

Others will be covered by the new agreement but will also have rights under domestic legislation under ‘retained EU law’. This currently mirrors existing EU rules but could be altered in future. The UK government has already indicated it intends to restrict access to income related benefits as part of its immigration scheme and end the export of child benefit. Scottish Ministers would also be able to alter this retained law in relation to devolved benefits.

However, this ‘retained law’ is only domestic law. It does not create an obligation on other states to co-operate. Any such obligations would require to be covered by agreements with the EU and/or individual states.

The UK proposals

The UK’s draft negotiating text proposes a quite minimalist approach which does not include devolved benefits. In contrast, the EU draft text covers the same benefits as EU 883/2004 and therefore does include some devolved benefits. The 'personal scope' (i.e who can benefit from these rules) is linked to the ending of free movement. Setting out the EU negotiating directives on 25th February this year the European Commission stated that:

The scope of social security coordination rules in the future relations with the UK should cover the possible mobility of UK and Union citizens in a situation where there will not be free movements of persons anymore. The social security coordination should be based on non-discrimination between EU Member States and full reciprocity.

The UK government’s envisaged approach in ‘The future relationship with the EU’ is to create:

Arrangements that provide healthcare cover for tourists, short-term business visitors and service providers, that allow workers to rely on contributions made in two or more countries for their state pension access, including uprating principles, and that prevent dual concurrent social security contribution liabilities.

This is reflected in the UK's draft text for a Social Security Co-ordination Agreement which includes:

Establishing which country’s legislation applies (who is the ‘competent state’) when making social security contributions (such as National Insurance Contributions in the UK). This is to ensure there is no ‘double payment’ of contributions.

Allowing someone to receive a state pension abroad, for contributions made in different countries to count towards a retirement pension and for pensions paid abroad to be uprated.

Provision of ‘necessary healthcare’, but only for temporary visitors and ‘where someone has the relevant document.’ As now, states will re-imburse each other for the costs.

Finally it proposes a Joint Committee for administration and resolution of disputes between parties.