Issue 10: EU-UK Future Relationship Negotiations

Following the UK's departure from the EU, the negotiations to determine the future relationship began on 2 March 2020. Over the course of the negotiations, SPICe will publish briefings outlining the key events, speeches and documents published. This tenth briefing covers the negotiations at the "half-way" point, as marked by the High-level conference on 15 June 2020.

Executive Summary

This is the tenth in a series of SPICe briefings covering the negotiations on the future relationship between the EU and the UK.

This briefing covers:

the second Joint Committee meeting, where it was confirmed the UK government would not make a request to extend the transition period ahead of the end-June cut-off point.

the Scottish Government's most recent calls for an extension, and its boycott of a conference call involving the UK government and devolved administrations.

the High-level conference involving involving the Prime Minister and heads of the relevant EU institutions.

the new timetable of talks.

the UK government's plans for transitional border arrangements following the transition period.

a report from the House of Lords' Constitution Committee on Brexit legislation and constitutional issues.

No extension to the transition period

Second Joint Committee meeting

The Withdrawal Agreement established a Joint Committee to oversee implementation of the agreement. The second meeting of this Joint Committee took place on 12 June, with its agenda published in advance. Ten technical corrections to the Withdrawal Agreement were adopted and the Committee agreed its third meeting would be in early-September 2020.

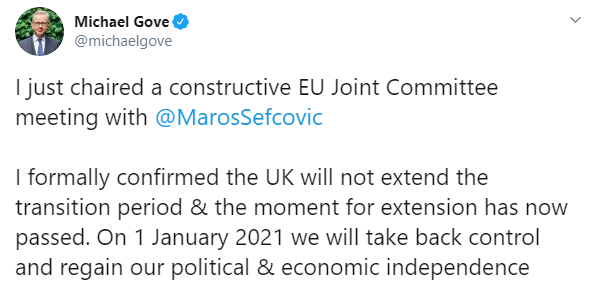

Following the second meeting, the UK Government issued a statement and Minister for the Cabinet Office Michael Gove tweeted:

Any extension to the transition period must be agreed by a decision of the Joint Council. Article 132 of the Withdrawal Agreement provides for the possibility of an extension and states:

the Joint Committee may, before 1 July 2020, adopt a single decision extending the transition period for up to 1 or 2 years.

Michael Gove states that "the moment for extension has passed". Under the Withdrawal Agreement, an extension decision is technically possible up until 30 June 2020, however this is unlikely to happen. No further Joint Committee meetings are planned before the deadline, the UK government have maintained a consistent policy not to request or agree to an extension, and domestic law prevents the UK government agreeing to an extension in the Joint Committee.

From the European Commission's side, Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič provided a press statement following the second meeting where he stated that the EU remains open to an extension:

Michael Gove confirmed to me that the UK will not consider an extension of the transition period. From our side, I have taken note of the position of the UK on this issue and have stated – as President von der Leyen has already done – that the EU remains open to such an extension.

Scottish Government reaction

The Scottish Government has made a number of calls for the transition period to be extended, both to allow time for a future relationship agreement to be negotiated and to take account of the impact of COVID-19. These calls have all been rejected by the UK Government.

On 12 June, the same day as the second Joint Committee meeting, the Scottish and Welsh First Ministers wrote to the Prime Minister to again request:

an extended Brexit transition period to complete negotiations and support businesses through recovery from the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic”.

A conference call between the UK Government and the Devolved Administrations had been due to take place on the evening of 12 June to discuss the EU-UK meeting on 15 June 2020. However, after news of the UK Government’s confirmation that no extension request will be made, Scottish and Welsh Government Ministers Michael Russell and Jeremy Miles issued a joint statement. They said they would not take part in a call with Paymaster General Penny Mourdant.

The statement said:

We cannot accept a way of working in which the views of the devolved governments are simply dismissed before we have had a chance to discuss them. In reality, the meetings we have had have simply been an opportunity for the UK Government to inform us of their views, not to listen or respond to ours.

We will be writing to Michael Gove to seek a complete re-boot of these talks and meanwhile we want the EU 27 to know that the position being taken by the UK Government with regard to an extension of the transition period runs counter to the views of our governments and, in our opinion, risks doing serious damage to the people of our countries.

Failing to request an extension at this time is a particularly reckless act given the damage coronavirus is doing to the economy and the impact on jobs.

On 14 June, Michael Gove wrote to Michael Russell and Jeremy Miles setting out the UK Government’s perspective on the events two day’s earlier. He made clear that the UK Government believed it had provided opportunities for discussion on the question of extending the transition period:

In short, there have been ample opportunities to discuss, both in public and private, the question of the transition period. Ultimately there was a disagreement of approach on this question. The UK Government understood and respected the view of the Welsh and Scottish Governments but was always clear that this was a reserved matter.

Michael Russell is due to give evidence to the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee on 18 June. He is likely to provide a further response to these events from the Scottish Government's perspective.

Scotland Office comment

Following the second meeting of the Joint Committee, the UK government's Scotland Office issued comments in support of the policy not to extend the transition period. These comments emphasised the need for certainty for businesses and the effect on fisheries, including:

Leaving the EU means that Scotland, and the other Devolved Administrations, will see a significant increase in the decision-making powers in fisheries, and for protecting the marine environment.

COSLA position

On 12 June, the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA) issued a call to extend the transition period:

“COSLA’s position has been about securing a good deal with our closest neighbours and partners over any timescale. This is a principled position that has the interest of our local communities in mind.

...Leaders were clear today that the lack of progress on these negotiations poses a significant risk to the Scottish economy and Local Government services and we must see an extension to the Transition Period.

Information of COSLA's work in Europe is available from their webpages.

Negotiations

High-level conference

Since the start of the negotiations it was envisaged that the parties would hold a "high-level conference" in June 2020 following on from the first few rounds of formal negotiations. The aim of this conference, as stated in the Political Declaration, was:

Following the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the Union, the Parties will convene to take stock of progress with the aim of agreeing actions to move forward in negotiations on the future relationship. In particular, the Parties will convene at a high level in June 2020 for this purpose.

The negotiating rounds which have taken place so far have been led by officials, albeit officials who themselves sit at high levels in the UK Government or the European Commission. Little progress has been made so far to resolve the contentious issues identified from the start of the process, namely level playing field, fisheries, police and judicial cooperation and governance of the agreement.

On 15 June, the High-level conference took place by video call involving Boris Johnson and heads of the relevant EU institutions.

The joint statement issued following the conference read:

Prime Minister Boris Johnson met the President of the European Council Charles Michel, the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, and the President of the European Parliament, David Sassoli, on 15 June by videoconference to take stock of progress with the aim of agreeing actions to move forward in negotiations on the future relationship.

The Parties noted the UK's decision not to request any extension to the transition period. The transition period will therefore end on 31 December 2020, in line with the provisions of the Withdrawal Agreement.

The Parties welcomed the constructive discussions on the future relationship that had taken place under the leadership of Chief Negotiators David Frost and Michel Barnier, allowing both sides to clarify and further understand positions. They noted that four rounds had been completed and texts exchanged despite the challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Parties agreed nevertheless that new momentum was required. They supported the plans agreed by Chief Negotiators to intensify the talks in July and to create the most conducive conditions for concluding and ratifying a deal before the end of 2020. This should include, if possible, finding an early understanding on the principles underlying any agreement.

The Parties underlined their intention to work hard to deliver a relationship, which would work in the interests of the citizens of the Union and of the United Kingdom. They also confirmed their commitment to the full and timely implementation of the Withdrawal Agreement.

Following the high-level conference, on 13 June Michael Gove gave a statement to the House of Commons.

Michael Gove indicated that he saw July as a important time to make progress:

I am pleased to say that both sides pledged yesterday, in a joint statement that was made public immediately afterwards, that they would intensify the talks in July and, if possible, seek to find an early understanding on the principles underlying any agreement. Our respective chief negotiators and their teams will... intensify talks from the end of this month, starting on 29 June...We are looking to get things done in July. We do not want to see this process going on into the autumn and then the winter. We all need certainty, and that is what we are aiming to provide.

And he also restated a summary of the current state of the negotiations from the UK's perspective:

...as my right hon. Friend the Paymaster General advised the House last week, following the fourth round of negotiations it is still the case that there has been insufficient movement on the most difficult areas where differences of principle remain. We are committed, in line with the political declaration, to securing a comprehensive free trade agreement with the EU built on the precedents of the agreements that the EU has reached with other sovereign states such as Canada, Japan and South Korea—and we are ready to be flexible about how we secure an FTA that works for both sides. The UK, however, has been clear throughout that the new relationship we seek with the EU must fully reflect our regained sovereignty, independence and autonomy. We did not vote in June 2016 to leave the EU but still to be run by the EU. We cannot agree to a deal that gives the EU Court of Justice a role in our future relationship, we cannot accept restrictions on our legislative and economic freedom—unprecedented in any other free trade agreement—and we cannot agree to the EU’s demand that we stick to the status quo on its access to British fishing waters.

A SPICe Spotlight blog summarising the negotiations at this "half-way" point concludes that whilst a deal is possible before the end of 2020, it is very unlikely it will cover all the different areas covered in both the EU and UK negotiating texts:

The negotiations are set to continue during the summer with both sides aware that a deal probably needs to be reached by October to allow it to be ratified in time for it to come into force at the end of the transition period. Reaching a deal is likely to require political compromises on both sides and may result in a more streamlined agreement than both sides might have hoped for. A deal which focuses on a small number of areas will also mean that negotiations will continue into 2021 and beyond as the EU and the UK seek to add elements to what they manage to agree in the next six months.

Dates of future rounds

A new timetable and format for the negotiations was agreed ahead of the high-level conference.

Negotiating rounds will now take place in July, August and in September, unless agreed otherwise.

By default these meetings will be in-person, subject to "any constraints required by the relevant national health recommendations".

As well as full formal rounds, there will be smaller more restricted and specialised meetings to focus on issues of particular difficulty.

The timetable includes meeting across the whole of July and into August:

The parties have agreed the following calendar in the first instance for July and August, which may be modified or complemented as necessary

Restricted round in the format of a meeting of the Chief Negotiators and of specialised sessions: week of 29 June to 3 July (Brussels)

Meetings of the Chief Negotiators / their teams / specialised sessions: week of 6 July (London)

Meetings of the Chief Negotiators / their teams / specialised sessions : week of 13 July (Brussels)

Round 5: week of 20 July to 24 July (London)

Meetings of the Chief Negotiators / their teams / specialised sessions : week of 27 July (London)

Round 6: week of 17 August to 21 August (Brussels)

UK Border arrangements for goods

On 12 June 2020, the UK government announced its plans for policing the Great Britain border with the EU for trade in goods following the end of the transition period. The UK government's proposal involves introducing new border controls in three stages up until 1 July 2021 and as a result of the UK leaving the Customs Union will involve the payment of tariffs on imports in some cases.

According to the UK government, the three stages will be:

From January 2021: Traders importing standard goods, covering everything from clothes to electronics, will need to prepare for basic customs requirements, such as keeping sufficient records of imported goods, and will have up to six months to complete customs declarations. While tariffs will need to be paid on all imports, payments can be deferred until the customs declaration has been made. There will be checks on controlled goods like alcohol and tobacco. Businesses will also need to consider how they account for VAT on imported goods. There will also be physical checks at the point of destination or other approved premises on all high risk live animals and plants.

From April 2021: All products of animal origin (POAO) – for example meat, pet food, honey, milk or egg products – and all regulated plants and plant products will also require pre-notification and the relevant health documentation.

From July 2021: Traders moving all goods will have to make declarations at the point of importation and pay relevant tariffs. Full Safety and Security declarations will be required, while for SPS commodities there will be an increase in physical checks and the taking of samples: checks for animals, plants and their products will now take place at GB Border Control Posts.

The UK government also announced it is planning to build new border facilities in Great Britain for carrying out required checks, such as customs compliance, transit, and Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) checks, as well as providing targeted support to ports to build new infrastructure. According to the government, where there is no space at ports for new infrastructure, it will build new inland sites where these checks and other activities will take place. The Government is currently consulting with ports across the UK to agree what infrastructure is required.

The flow of goods between Great Britain and Northern Ireland will follow a different approach as a result of the Ireland and Northern Ireland Protocol which forms part of the Withdrawal Agreement. The UK government published its plans for the operation of the Protocol on 20 May 2020.

On 11 June, the Prime Minister announced that responsibility for the border delivery group, henceforth known as the border and protocol delivery group, has transferred from Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs to the Cabinet Office. According to the Prime Minister, this change will help to ensure readiness of the border for the end of the transition period.

The UK Global Tariff

On 19 May 2020, the UK government published its UK global tariff schedule which will apply from 1 January 2021 and will replace the EU’s Common External Tariff.

The new tariff schedule will apply to all imports to the UK, unless they are imported from a country which has a preferential trade agreement with the UK. For example, the UK and the EU are currently negotiating a comprehensive free trade agreement, if this is successfully concluded before the end of 2020, then the UK's new global tariff schedule will not apply to imports from the EU from 1 January 2021. Conversely, if the UK and EU fail to reach an agreement then EU imports to the UK will also be required to pay the appropriate tariff.

Lords report: Brexit legislation and constitutional issues

On 9 June, the House of Lords Constitution Committee published a report on Brexit legislation and constitutional issues.

The report describes the UK's exit from the EU as a "unprecedented legislative challenge" and in assessing the current situation the Committee states:

In the process of delivering the UK’s departure from the EU on 31 January 2020 some, though not all, of these challenges were overcome, but the Government is still only a little past half-way through legislating for Brexit. Significant bills to deliver Brexit have received Royal Assent— the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 (EUWA) and the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 prime among them. However, a considerable amount of further legislation, both primary and secondary, is still needed. Bills on agriculture, fisheries, immigration and trade were introduced in the 2017–19 session and have been reintroduced in the current session. Bills will be needed to underpin some of the common frameworks for policies that are devolved to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and further legislation may be required to implement the future relationship the Government is seeking to negotiate with the EU.

The report includes a table taking stock of Brexit primary legislation either with Royal Assent or in progress.

Describing these bills, the Committee states:

A distinguishing feature of the Brexit bills was the extent of the delegated powers they contained. Many were skeleton bills, providing broad powers to ministers to create new policy regimes and public bodies for the UK after Brexit with little or no detail as to what policy would be implemented or the nature of institutions which would be created. In most cases they included Henry VIII powers, allowing primary legislation to be amended by statutory instruments.

The report goes on to detail the Committee's concerns and recommendations in relation to delegated powers. While it is not the role of the House of Lords Constitutional Committee to scrutinise the Scottish Government, its observations can be seen as relevant given that Brexit legislation also provides delegated powers to Scottish Ministers

Chapter 3 of the report relates to devolution.

On repatriated powers and legislative consent consent for primary legislation, the report notes:

The UK entered the European Union before devolution to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Powers that were given to the EU during the UK’s membership are now returning to a fundamentally different governance structure. The UK’s exit from the European Union, and in particular the transfer of powers back to Westminster and the devolved institutions, has strained the relationships between the UK Government and the governments of Scotland and Wales. This is evident in the reluctance and, in certain cases, the refusal, of the devolved legislatures to consent to some Brexit bills.

The Committee then comment on devolved consent for secondary legislation, saying:

As well as legislative consent to bills, there has also been an issue with consent to the use of delegated powers. In some bills—Brexit-related and otherwise—powers were delegated to UK ministers to legislate in devolved areas without an explicit requirement to consult or have the consent of devolved ministers or legislatures.

And recommending:

While the legislative consent convention—that the UK Parliament will not normally legislate in areas of devolved competence without consent—does not apply to delegated legislation, we believe formal engagement with the devolved institutions on the use of such powers should be a requirement.

We recommend that powers for UK ministers to make delegated legislation in devolved areas, including the power to supersede law made by devolved legislatures, should include a requirement either to consult devolved ministers or to seek their consent, depending on the significance of the power in question. The more significant the power, the greater the need for consent to be sought. We note that this approach has been adopted in the Fisheries Bill and we encourage the Government to follow this precedent in future legislation.

The report's final chapter deals with the impact of retained EU law and case law.

CTEEA Committee evidence on fish, level playing field and financial services

On 11 June, the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee took oral evidence from:

Professor Sarah Hall, Professor of Economic Geography, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Nottingham;

Elspeth Macdonald, Chief Executive Officer, Scottish Fishermen's Federation;

Allie Renison, Head of EU and Trade Policy, Institute of Directors.

This evidence session focused on fisheries, level playing field conditions, and financial services. The Official Report of the session is available and the panellists' written evidence is published.