The revised UK Fisheries Bill

This briefing considers the UK Fisheries Bill 2019-20 from a Scottish perspective. The Bill was introduced in the House of Lords on 29 January 2020. It follows on from the Fisheries Bill 2017-2019 introduced in the previous UK parliament on 25 October 2018 but which fell at the end of the parliamentary session. The Bill will provide the legal framework for the UK to operate as an independent coastal state now that the UK has left the European Union and will leave the Common Fisheries Policy after the transition period. Many parts of the Bill apply in Scotland.

Executive Summary

The UK Fisheries Bill was introduced in the House of Lords on 29 January 2020. It follows on from the Fisheries Bill introduced in the previous parliament on 25 October 2018. The Bill will provide the legal framework for the UK to operate as an independent coastal state now that the UK has left the European Union and will leave the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) after the transition period

The first section of this briefing provides general information on Brexit-related legislation, of which this is one example, and what this means for Scotland.

Fisheries is generally a devolved matter - Devolved Administrations regulate fisheries in their waters and regulate their vessels wherever they fish.

The first clause of the Bill sets out fisheries objectives. These set out priorities for the Fisheries Administrations once the UK is out of the CFP. These partly mirror the objectives of the CFP. Two new objectives - the 'national benefit' objective and 'climate change' objective - have been added to the revised Bill, and the ‘discards’ objective has been changed to a ‘bycatch’ objective.

Clauses 2-11 of the Bill create a Common UK Framework requiring the four UK Fisheries Administrations to develop a 'Joint Fisheries Statement' detailing policies for contributing to the achievement of the fisheries objectives. The revised Bill contains new clauses requiring the development of 'Fisheries Management Plans' setting out policies for restoring or maintaining fish stocks at sustainable levels.

Clauses 12-13 revoke EU legislation allowing the automatic right of foreign vessels registered in the EU to access UK waters. It requires foreign vessels fishing in UK waters to be licensed by one of the UK's Fisheries Administrations.

Clauses 14-20 detail the powers and provisions for Ministers to license UK and foreign vessels fishing in UK waters and the powers available to Ministers to punish vessels for committing offences.

Clauses 23-27 provide the Secretary of State the power to determine the quantity of fish that may be caught by British fishing boats. The Secretary of State must consult Scottish Minsters in determining this. The UK Government views determination of fishing opportunities as a reserved function. The Scottish Government disagrees.

Clauses 28-32 grant the Secretary of State powers to introduce regulations for a scheme to charge English vessels for unauthorised catches. The purpose is to set charges to deter overfishing and to incentivise more sustainable fishing practices and avoid unwanted catches.

Clauses 33-35 provide Ministers with powers to make grants to the industry and to charge the industry for services provided. Clause 33 aims to provide for a scheme to replace grants that were previously available through EU funding via the European Maritime Fisheries Fund (EMFF).

Clauses 36-42 provide broad powers to make provision through secondary legislation on matters currently regulated by the EU under the CFP. Not all of these powers were conferred on Scottish Ministers in the previous version of the Fisheries Bill but have now been extended to Scotland under Schedule 8 of the Bill.

Schedule 9 provides powers for Scottish Ministers to make orders relating to the impact of fishing on marine conservation. This is to replace EU measures for the protection of the marine environment in the offshore region.

This briefing examines the Bill from a Scottish perspective. The House of Lords Library published a briefing on the Bill ahead of its Second Reading. The Bill has completed the Committee stage. A date for the Report stage has yet to be announced.

Author contributions

This briefing was led by Damon Davies and Anna Brand in the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe), in collaboration with James Harrison, Professor of Environmental Law at the University of Edinburgh through the SPICe Framework Agreement for Research Services in Relation to Brexit.

Professor Harrison teaches on a number of international law courses, including specialist courses in the international law of the sea, international environmental law, and international law for the protection of the marine environment. His research interests span these areas, considering how the legal rules evolve and interact, as well as examining how international law and policy influences the domestic legal framework.

1. Brexit-related UK legislation

This section of the briefing provides some information on the impact of the UK’s exit from the EU on law-making in devolved areas. It also examines the powers that Ministers have to make laws in devolved areas.

1.1 What does the UK leaving the EU mean for law making?

Many of the laws in the UK derive from its membership of the EU. These laws cover issues from workers’ rights to the labelling of food.

The UK left the EU on 31 January 2020. However, EU law will continue to apply during a transition period which will end on 31 December 2020.

For the purposes of legal continuity, the UK Government wishes to preserve, as far as possible, the legal position which exists immediately before the end of the transition period. This will be achieved by taking a “snapshot” of all of the EU law that applies in the UK at that point and bringing it within the UK's domestic legal framework as a new category of law, known as “retained EU law”.

The creation of this new category of UK law was one of the main purposes of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018. The Act aims to ensure that the UK has the laws it needs after the end of the transition period. This could include, for example, the law on the nutrition and health claims made on food, or on ensuring environmental protection in marine areas.

The UK will be able to amend the policy underlying this retained EU law after the end of the transition period (i.e. with effect from 1 January 2021) by making new domestic laws (laws which apply to the whole of the UK or to any part of it.).

For more on how domestic laws will be made see 'Making new laws in devolved areas after EU exit'.

1.2 Making new laws in devolved areas after EU exit

Some areas of law have always been determined at a UK level. For areas of law which are derived from the EU, the UK must continue to comply with that EU law until the end of the transition period on 31 December 2020.

From 1 January 2021, the UK will no longer require to comply with EU law. Responsibility for policy in areas which were previously dealt with at an EU level will lie with the UK Government and/or the devolved governments.

Scottish Ministers will continue to have powers in devolved areas and the Scottish Parliament will continue to legislate for Scotland in respect of devolved matters. The UK Parliament has the power to pass law in all policy areas for the whole UK and it will continue to have that power.

The UK Parliament will not normally pass primary legislation (an Act of Parliament) in devolved areas without seeking the consent of the devolved legislatures. This is through the process of legislative consent.

Prior to 2018, UK Ministers generally only had powers to make regulations (secondary legislation) in devolved areas for the purpose of giving effect to EU law. That law, and the policy behind it, had been decided through the EU legislative process.

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 gives UK Ministers power to make regulations in devolved areas for the purpose of amending laws so that they work effectively after the UK leaves the EU. The aim of these kinds of regulations is to achieve legal continuity after the end of the transition period.

Some UK legislation, like the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 goes further and gives UK Ministers the power to make secondary legislation (regulations) which is capable of changing policy in devolved areas.

UK Ministers will not normally make such regulations in devolved areas without the consent of the Scottish Ministers. In some cases, such agreement is a legal requirement but not in all. The Scottish Parliament cannot scrutinise secondary legislation laid before the UK Parliament. However, it has a clear interest in such legislation where it relates to devolved matters.

The Scottish Parliament can scrutinise Scottish Ministers’ decisions to consent to regulations which are made by UK Ministers in devolved areas. A process for this is being agreed between the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament. A protocol is already in place for statutory instruments made to fix deficiencies (gaps, errors and unintended consequences) as a result of powers given to UK and Scottish Ministers under the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018.

1.3 Do Ministers have new powers to make law in devolved areas as a result of EU exit?

The European Union (Withdrawal Act) 2018 gives Scottish Ministers powers to amend the law in devolved areas by regulations (secondary legislation) so that Scottish laws work effectively after the UK leaves the EU and the transition period is complete. UK Ministers have powers under the European Union (Withdrawal Act) 2018 to amend the laws in the UK, including Scottish laws, so that they work effectively after the UK leaves the EU. These powers have been conferred concurrently, meaning that either UK Minsters or the Scottish Ministers can make the regulations.

In some cases where the UK Government and the Scottish Government wish to pursue the same policy objective, the Scottish Government can ask the UK Government to lay statutory instruments that include proposals relating to devolved areas of responsibility. The UK Government can also make regulations in devolved areas without Scottish Ministers asking them to. UK Ministers will not normally make such regulations in devolved areas without the consent of the Scottish Ministers. That agreement is a legal requirement in some cases, but not in all.

The changes made by these kinds of regulations are often technical and are there, in many cases, to achieve legal continuity. In some cases, the changes are very minor – removing references to EU institutions, for example. In other cases, they are more significant - such as changes in regulatory requirements. The powers to make these kinds of regulations are mainly time limited.

The European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 does, however, give UK and Scottish Ministers a suite of new powers in devolved areas that go beyond correcting deficiencies to achieve legal continuity. These powers have been conferred concurrently, meaning that either UK Ministers or Scottish Ministers can make the regulations. The suite of concurrent powers includes:

powers to implement long term obligations for the recognition of citizens' rights under the Withdrawal Agreement

powers to deal with separation issues such as the regulation of goods placed on the market

powers to implement the Ireland/Northern Ireland protocol.

There are other powers created or amended in the regulations made under the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 and also powers in other Brexit related legislation, such as the Direct Payments to Farmers (Legislative Continuity) Act 2020. Some of these powers may be used to make regulations which change policy. The powers are generally not time limited.

1.4 What is the significance of this Bill in the post EU exit legislative landscape?

This Bill is a direct result of the UK's exit from the EU, because policy in this area was previously set at EU level.

If new law was not made in this area, then the legal position from 1 January 2021 would be as provided for under retained EU law.

This Bill puts forward a proposal for a new policy to apply from 1 January 2021.

1.5 Does this legislation relate to common frameworks?

In many policy areas, EU laws have ensured that there is a consistent approach across the UK, even where these policy areas are devolved. This is because the UK Government and all of the devolved governments have had to comply with EU law. In effect, this compliance has meant that the same policy has been followed.

The UK left the EU on 31 January 2020. There is now a transition period until 31 December 2020. Through the transition period the UK will continue to comply with EU law. After the end of the transition period, there is the possibility of policy divergence because the UK Government and the devolved administrations within the UK will no longer need to comply with EU law. Common frameworks can be developed so that rules and regulations in certain areas remain the same, or at least similar, across the UK.

A common framework is an agreed approach to a policy, including the implementation and governance of it. Common frameworks will be used to establish policy direction in areas where devolved and reserved powers and interests intersect. Developments in common frameworks will be one of the factors which determines how Scotland and the rest of the UK will interact post-EU exit.

Some common frameworks may be legislative, but it is anticipated that the majority will be non-legislative. That means that they will be agreed through memorandums of understanding, concordats and so on, rather than being set out in primary legislation.

There may, however, be provision made in primary legislation which relates to a common framework. It is likely that some provisions made in this Bill will form part of common frameworks on fisheries. Similarly, some regulations (secondary legislation) are likely to make provision which is linked to common frameworks. Until a common framework is explicitly developed, and details are shared by the UK and Scottish Governments, it is unclear what the broader extent of a fisheries common framework will be. This is a challenge for parliamentarians across portfolios.

As part of its scrutiny role, the Parliament needs to be able to consider the Scottish Government’s approach to, and development of, common frameworks. The Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament are therefore working together to produce a protocol for the sharing of information on common frameworks.

The committees of the Scottish Parliament will lead on scrutiny of common frameworks in their policy area.

Further information on common frameworks can be found on SPICe’s post-Brexit hub.

2. Devolution of fisheries and marine policy

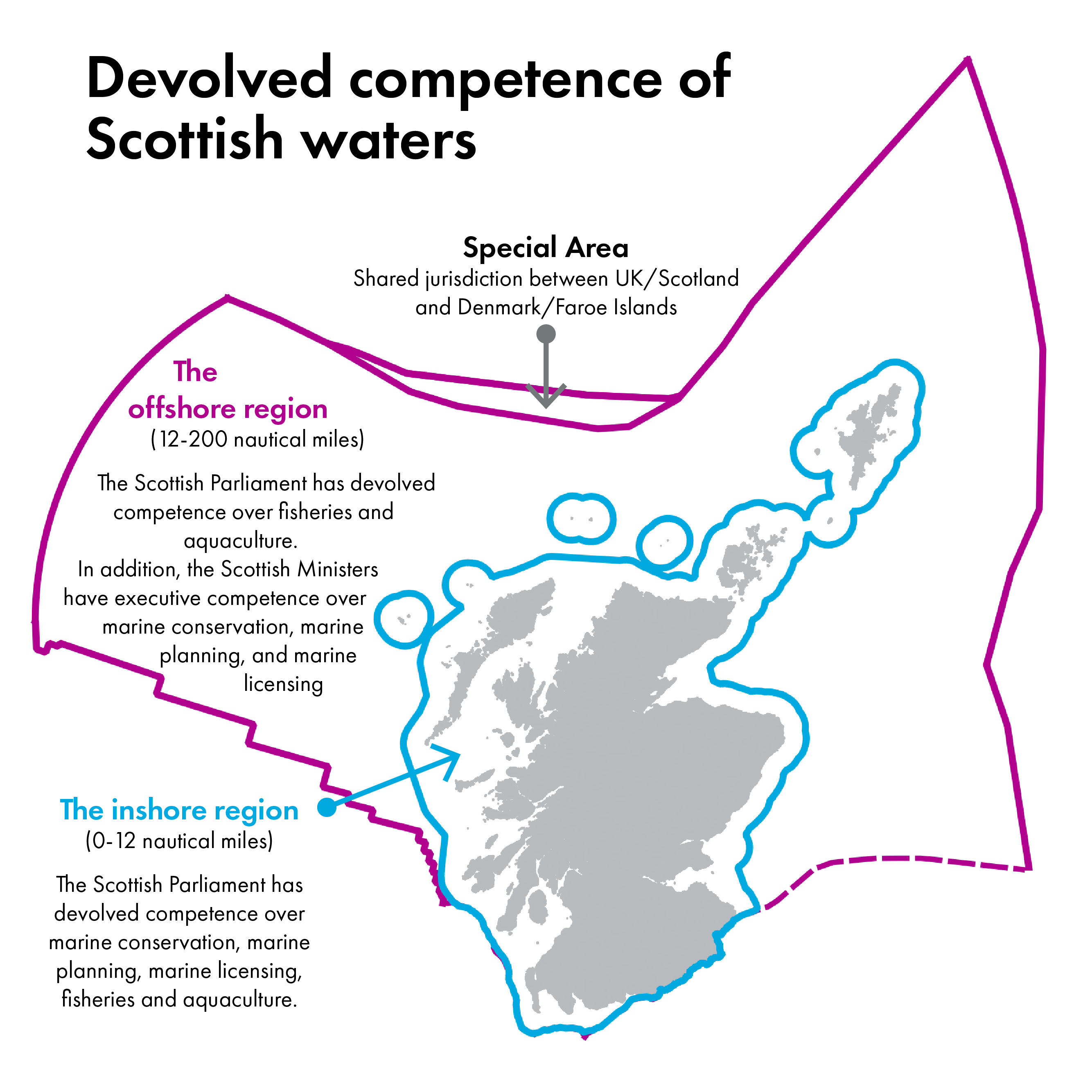

Fisheries is generally a devolved matter. In Scotland, the Scottish Parliament has competence to regulate all fishing activity within the Scottish Zone and to regulate Scottish fishing boats wherever they fish.

The Scotland Act 1998 defines the "the Scottish zone" as "the sea within British sea fishery limits...which is adjacent to Scotland" (section 126(1)). British sea fishery limits coincide with the boundaries of the United Kingdom Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) as laid down by the Exclusive Economic Zone Order 2013 and they include the Special Area shared between the United Kingdom and the Faroe Islands (see Box 2).

According to schedule 5 of the Scotland Act 1998, the following are reserved:

Regulation of sea fishing outside the Scottish zone (except in relation to Scottish fishing boats).

(section C6)

In the past, the powers of the Scottish devolved institutions have also been limited by the involvement of the EU in fisheries management under the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP). However, within 12 nautical miles, the CFP recognised that Member States had greater leeway to regulate fishing.1

Once the implementation period has expired (likely on 31 December 2020), these limits will no longer apply to Scotland. The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 recognises that the Scottish Parliament will have the power to amend retained EU law2, unless particular provisions of retained EU law are protected from modification by regulations made by the UK government under section 30A of the Scotland Act 1998. This means that the devolved institutions in Scotland may have greater discretion as to how fisheries are managed in Scottish waters, for example in relation to the quantity of sea fish that may be caught, or the amount of time that fishing boats may spend at sea. However, other policy areas related to fisheries may be reserved.

International relations (see Box 7) and the regulation of marine transport are two other reserved policy areas which may have implications for fisheries management.

Subject to certain exceptions (e.g. defense, marine transport), the Scottish Parliament has devolved competence in relation to marine conservation, marine planning and marine licensing in the inshore region (out to 12 nautical miles) and the Scottish Ministers have executive competence to make orders in relation to marine conservation, marine planning and marine licensing in respect of the offshore region (12-200 nm).

As UK vessels fish throughout UK waters, the UK Fisheries Administrations (see Box 1 below) may need to work together to ensure a common or consistent approach to fisheries management where necessary or appropriate. This is reflected in various provisions of the Fisheries Bill discussed in further sections of this briefing.

Box 1. UK Fisheries Administrations

The Marine Management Organisation (MMO) -An executive, non-departmental public body of the UK Government responsible for, among other things, fisheries management in England.

Marine Scotland - a directorate within the Scottish Government responsible for fisheries management in Scotland.

The Welsh Government.

The Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) Marine and Fisheries Division - a department of the Northern Ireland Government responsible for fisheries management in Northern Ireland.

Box 2. Special Area

The Special Area is established under a treaty between the United Kingdom and Denmark, on behalf of the Faroe Islands, in which the two parties have agreed to share jurisdiction over a number of maritime activities, including fishing, in an area defined in a schedule to the treaty. The Special Area is included within the limits of the UK EEZ, but it is subject to special rules reflecting the fact that activities within the area may also be managed by the Faroe Islands.

Within the Special Area, each party may apply its rules and regulations concerning the management of fishing, including the issuing of fishing licences, but it must refrain from action which would infringe upon the exercise of fisheries jurisdiction by the other party; in particular, it must refrain from the inspection or control of fishing vessels which operate in the Special Area under the authority of the other party. Special “hail-in” and “hail-out” rules are also applied to fishing vessels entering and leaving the Special Area. Whilst the UK was part of the EU, access to the Special Area was available not only to UK fishing vessels, but also fishing vessels from other Member States under the equal access principle of the CFP. When the transition period ends, EU vessels will no longer have automatic access to the Special Area, but they may be authorized to fish in these waters by either the UK or the Faroe Islands.

3. UK Fisheries Bill 2019-20

The revised UK Fisheries Bill was introduced in the House of Lords on 29 January 2020.

According to the Explanatory Notes the Bill will:

...provide the legal framework for the United Kingdom to operate as an independent coastal state under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 (UNCLOS) after the UK has left the European Union (EU) and the Common Fisheries Policy (the CFP). The Bill creates common approaches to fisheries management between the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (the "Secretary of State") and the Devolved Administrations, known collectively as the Fisheries Administrations, and makes reforms to fisheries management in England. It also confers additional powers on the Marine Management Organisation ("the MMO") to improve the regulation of fishing and the marine environment in the UK and beyond.

The UK Fisheries Bill 2017-19

A previous version of the UK Fisheries Bill was introduced to the House of Commons on 25 October 2018 but failed to complete its passage through Parliament before the end of the session.

The Bill reached the Committee stage but fell prior to Report Stage. The Bill as amended during the committee stage is available here:

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/2017-2019/0305/Fisheries%20Comparision.pdf

Prior to publication of the 2017-19 Bill

The Fisheries White Paper, Sustainable Fisheries for a Future Generation, was published for consultation in July 20181. On 25 October 2018 the UK Government published a summary of responses to the White Paper at the same time the Bill was published2. It includes some commentary on the Bill in the context of responses.

SPICe published a blog on the white paper - The future for fish – issues in the UK White Paper.

3.1 Fisheries objectives - Clause 1

Until the end of the implementation period (until 31 December 2020), fisheries policy in the UK is set via the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP). This includes a set of policy objectives for fisheries. These are set out in Article 2 of Regulation 1380/2013 (the CFP regulation).

The first clause of the Fisheries Bill sets out new fisheries objectives for the UK as a non-EU independent coastal state. These largely, but not wholly, mirror current objectives in the CFP Regulation. A comparison of the objectives in the 2019-2020 Bill, the 2017-2019 Bill, and Article 2 of the CFP Regulation can be found in the table below.

The objectives of the Bill will apply to the whole of the UK, including Scotland. The joint fisheries statement provided for by Clause 2 of the Bill (explored below) will set out how these objectives will be met. The new objectives are the:

(a) sustainability objective,

(b) precautionary objective,

(c) ecosystem objective,

(d) scientific evidence objective,

(e) bycatch objective,

(f) equal access objective,

(g) national benefit objective, and

(h) climate change objective.

Most objectives apply to “fish activities”, which broadly covers the catching, transportation and processing of fish, whether or not carried out in the course of business and so includes not only commercial fishing, but also recreational fishing.

Box 3 - Provisions on aquaculture

Scottish and UK officials worked together on an amendment to Clause 1 of the 2017-2019 UK Fisheries Bill "to ensure aquaculture is appropriately incorporated into the drafting of the joint fisheries objectives"1. The version of the Bill as amended in Public Bill Committee2 did not yet include additional references to aquaculture in Clause 1, and the Bill fell at the end of the parliamentary session, prior to reaching the report stage. The 2019-20 Bill includes a number of additional references to aquaculture in the definitions of the objectives, notably the sustainability objective, ecosystem objective, scientific evidence objective, and climate change objective.

The UK Government have stated in the Explanatory Notes to the Bill, that "objectives (a) to (d) replace equivalent objectives in Article 2 of the Common Fisheries Policy Basic Regulation, while (e) to (h) reflect other priorities for the UK after it leaves the CFP."3

3.1.1 New objectives: National benefit and climate change

The "national benefit objective" and "climate change objective" are new for this iteration of the Bill.

The outcomes for the national benefit objective are partially mirrored in the CFP, in that both UK and European objectives set out the need for fishing to bring social and economic benefit.

The climate change objective is not mirrored in the CFP. In introducing the Bill at second reading on 11 February 2020, Lord Gardiner of Kimble stated that the purpose of the climate change objective is to:

ensure that the impacts of the fishing industry on climate change are minimised while ensuring that fisheries management adapts to a changing climate1

Overall, this addition was welcomed during second reading. However, some MPs raised the need to go further. Baroness Young of Old Scone (Lab) noted:

I welcome the new climate-change objective in the Bill. We must ensure that it is about not just low-carbon fishing technology but the importance of recovering fish populations and restoring marine habitats, such as kelp forests, deep sediments and coastal seagrass meadows, as effective natural solutions to tackling the twin emergencies of climate change and biodiversity together.1

3.1.2 New objectives: Bycatch

The "bycatch objective" has been amended from a "discards objective" since the last iteration of the Bill.

| Bycatch objective (2019-20) | Discards objective (2017-19) |

|---|---|

| (a) the catching of fish that are below minimum conservation reference size, and other bycatch, is avoided or reduced, (b) catches are recorded and accounted for, and (c) bycatch that is fish is landed, but only where this is appropriate and (in particular) does not create an incentive to catch fish that are below minimum conservation reference size | (a) avoiding and reducing, as far as possible, unwanted catches, and (b) gradually ensuring that catches are landed. |

This change suggests a shift away from the EU focus on prohibiting discards through the so-called landing obligation, which has been fully in force since January 2019 (see Box 4).

During the second reading, Lord Gardiner of Kimble (Con) gave the following explanation for the change:

While of course we are committed to ending wasteful discards, discarding is a symptom of bycatch, and this objective aims also to address the root causes of the issue. That is why it is now called the bycatch objective.

House of Commons Hansard. (2020, February 11). Fisheries Bill [HL]. Retrieved from https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/2020-02-11/debates/F1D340E5-8EB8-4B77-ABD3-0A83120A349C/FisheriesBill(HL) [accessed 17 February 2020]

Box 4 - What does it mean to discard, and what is the landing obligation?

Quotas are allocated to fishers to control the amount of fish that is landed to protect fish stocks from overfishing. Quota is only monitored against what is landed, and therefore fishers were previously able to discard any catch that they didn't have quota for. However, with the obligation to land all caught regulated species (with some exceptions), fishers would more quickly reach their quota with fish that cannot be sold, if they do not change fishing practices to avoid bycatch. The so-called discards ban (or alternatively landing obligation) was introduced under Article 15 of the reformed CFP Regulation, adopted in 2013, and the measures were phased in over a number of years.

As set out by the European Commission:

"Discarding is the practice of returning unwanted catches to the sea, either dead or alive, because they are undersized, due to market demand, the fisherman has no quota or because catch composition rules impose this. The reform of the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) of 2013 aims at gradually eliminating the wasteful practice of discarding through the introduction of the landing obligation. [...]

"The landing obligation requires all catches of regulated commercial species on-board to be landed and counted against quota. These are species under TAC (Total Allowance Catch, and so called quotas) or, in the Mediterranean, species which have a MLS (minimum landing size such as mackerel which is regulated by quotas; and gilt-head sea-bream regulated by size). Undersized fish cannot be marketed for direct human consumption purposes whilst prohibited species (e.g. basking shark) cannot be retained on board and must be returned to the sea."2

The landing obligation came fully into force on 1 January 2019 after a four-year phasing in period.

In practice, there have been problems with the landing obligation. A House of Lords European Union Select Committee inquiry found that, while the UK fishing industry and government enforcement agencies should have been preparing for the obligation to come into force since 2015, there was "little evidence that fishers had adhered to the new rules during the phasing in period, or that there had been any meaningful attempt to monitor or enforce compliance. And witnesses were virtually unanimous in their view that the UK was not ready to implement or enforce the landing obligation from 1 January."3

The landing obligation will continue to apply as retained EU law, until measures are taken to repeal or replace it within the UK. Though it does not apply to Scotland, as an alternative to the landing obligation, the Bill makes provision for "discard prevention charging schemes" to be brought forward in relation to England. Under this provision, unauthorised bycatch by holders of an English sea fishing license or a producer organisation that has at least one member who is the holder of an English sea fishing license could be subject to a charge. Authorities may only charge fishers who are registered under the scheme, and registration is voluntary.

The UK Government's Sustainable Fisheries for Future Generations White Paper further explains how such a scheme might work through the use of reserve quota which can effectively be bought for a charge if additional fish is landed:

We will also consider allocating part of any new quota in the reserve to underpin a new approach to tackle the problem of choke species, so that the crucial discard ban works in practice as well as in theory.

We will consider the development of new ways to deter fishers from catching or discarding fish caught in excess of quota, drawing on the experience of other fishing states such as New Zealand. Such fish could be subject to a charge related to the market value of the fish landed, with the landings covered by quota retained in the reserve for such purposes. These charges could be recycled back into the sector to help develop measures to help them further change behaviour and thus reduce the need for the scheme over time.4

In its Future Fisheries Management Discussion Paper, the Scottish Government has indicated a similar approach to using quota in reserve. However, they do not mention a discards charging scheme for Scotland:

We continue to support the principle of a discard ban - it is unacceptable to return good fish back to the sea dead. But we must, in partnership with stakeholders, develop a management system that supports this and can work in practice. We will consider ring- fencing quota to help fishers to operate legally within such a system, as well as using it to reward and/or incentivise best practice in innovative fishing techniques or methods.5

3.1.3 Other changes to fisheries objectives since the 2017-19 Fisheries Bill

The box below sets out a comparison between the objectives set out in the 2017-19 Bill, the 2019-20 Bill, and Article 2 of the Common Fisheries Policy Regulation. Notable changes include:

Ecosystem objective: the addition of an objective to, where possible, reverse impacts on marine ecosystems, and minimise or, where possible, eliminate incidental catches of sensitive species. This is related to the bycatch objective. The definition of "sensitive species" is partially linked to other EU law relating to nature conservation:

(a) any species of animal or plant listed in Annex II or IV of Directive 92/43/EEC of the Council of the European Communities on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild flora and fauna (the "habitats directive")

(b) any other species of animal or plant, other than a species of fish, whose habitat, distribution, population size or population condition is adversely affected by pressures arising from fishing or other human activities, or

(c) any species of bird;

Scientific evidence objective: the addition of an objective to collect scientific data relevant to the management of fish and aquaculture activities, for fisheries policy authorities to work together on collecting and sharing this data, and for the management of fish and aquaculture activities to be based on the best available scientific advice.

3.1.4 The Fisheries Bill and the Common Fisheries Policy - Comparison

| UK Fisheries Bill 2019-20 (Clause 1) | UK Fisheries Bill 2017-19 (Clause 1) | Common Fisheries Policy Regulation (Article 2) |

|---|---|---|

| (2) The “sustainability objective” is that— (a) fish and aquaculture activities are— (i) environmentally sustainable in the long term, and (ii) managed so as to achieve economic, social and employment benefits and contribute to the availability of food supplies, and (b) the fishing capacity of fleets is such that fleets are economically viable but do not overexploit marine stocks. | (2) The “sustainability objective” is to ensure that fishing and aquaculture activities are—(a) environmentally sustainable in the long term, and(b) managed in a way that is consistent with the objectives of achieving economic, social and employment benefits, and of contributing to the availability of food supplies. | 1. The CFP shall ensure that fishing and aquaculture activities are environmentally sustainable in the long-term and are managed in a way that is consistent with the objectives of achieving economic, social and employment benefits, and of contributing to the availability of food supplies. |

| (3) The “precautionary objective” is that— (a) the precautionary approach to fisheries management is applied, and (b) exploitation of marine stocks restores and maintains populations of harvested species above biomass levels capable of producing maximum sustainable yield. | (3) The “precautionary objective” is—(a) to apply the precautionary approach to fisheries management, and(b) to ensure that exploitation of living marine biological resources restores and maintains populations of harvested species above biomass levels capable of producing maximum sustainable yield. | 2. The CFP shall apply the precautionary approach to fisheries management, and shall aim to ensure that exploitation of living marine biological resources restores and maintains populations of harvested species above levels which can produce the maximum sustainable yield.In order to reach the objective of progressively restoring and maintaining populations of fish stocks above biomass levels capable of producing maximum sustainable yield, the maximum sustainable yield exploitation rate shall be achieved by 2015 where possible and, on a progressive, incremental basis at the latest by 2020 for all stocks. |

| (4) The “ecosystem objective” is that— (a) fish and aquaculture activities are managed using an ecosystem-based approach so as to ensure that their negative impacts on marine ecosystems are minimised and, where possible, reversed, and (b) incidental catches of sensitive species are minimised and, where possible, eliminated. | (4) The “ecosystem objective” is—(a) to implement an ecosystem-based approach to fisheries management so as to ensure that negative impacts of fishing activities on the marine ecosystem are minimised, and(b) to ensure that aquaculture and fisheries activities avoid the degradation of the marine environment. | 3. The CFP shall implement the ecosystem-based approach to fisheries management so as to ensure that negative impacts of fishing activities on the marine ecosystem are minimised, and shall endeavour to ensure that aquaculture and fisheries activities avoid the degradation of the marine environment. |

| (5) The “scientific evidence objective” is that— (a) scientific data relevant to the management of fish and aquaculture activities is collected, (b) where appropriate, the fisheries policy authorities work together on the collection of, and share, such scientific data, and (c) the management of fish and aquaculture activities is based on the best available scientific advice. | (5) The “scientific evidence objective” is—(a) to contribute to the collection of scientific data, and(b) to base fisheries management policy on the best available scientific advice. | 4. The CFP shall contribute to the collection of scientific data. |

| (6) The “bycatch objective” is that— (a) the catching of fish that are below minimum conservation reference size, and other bycatch, is avoided or reduced, (b) catches are recorded and accounted for, and (c) bycatch that is fish is landed, but only where this is appropriate and (in particular) does not create an incentive to catch fish that are below minimum conservation reference size. | (6) The “discards objective” is to gradually eliminate discards, on a case-by-case basis, by—(a) avoiding and reducing, as far as possible, unwanted catches, and(b) gradually ensuring that catches are landed. | 5. The CFP shall ... gradually eliminate discards, on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the best available scientific advice, by avoiding and reducing, as far as possible, unwanted catches, and by gradually ensuring that catches are landed.There are also provisions in 5) on use of unwanted catch, economic viability, aquaculture, standard of living of coastal communities etc. |

| (7) The "equal access objective" is that the access of UK fishing boats to any area within British fishery limits is not affected by:(a) the location of the fishing boat's home port, or(b) any other connection of the fishing boat, or any of its owners, to any place in the United Kingdom. | Not included in 2017-2019 Bill | Not mirrored in Article 2. However, Article 5 of the CFP Regulation sets out the principle of equal access for EU Member State Vessels in EU waters. |

| (8) The “national benefit objective” is that fishing activities of UK fishing boats bring social or economic benefits to the United Kingdom or any part of the United Kingdom. | Not included in 2017-2019 Bill | A number of the objectives under Article 2(5) touch on the topic of social or economic benefits of fishing:(c) provide conditions for economically viable and competitive fishing capture and processing industry and land-based fishing related activity; (f) contribute to a fair standard of living for those who depend on fishing activities, bearing in mind coastal fisheries and socio-economic aspects; (h) take into account the interests of both consumers and producers; (i) promote coastal fishing activities, taking into account socioeconomic aspects; |

| (9) The “climate change objective” is that— (a) the adverse effect of fish and aquaculture activities on climate change is minimised, and (b) fish and aquaculture activities adapt to climate change. | Not included in 2017-2019 Bill | Not mirrored in the CFP |

3.1.5 Achieving fisheries objectives

A number of peers raised concerns about the lack of a specific and legally binding duty to achieve the fisheries objectives. This was discussed at the second reading; more information on this can be found below.

3.2 Fisheries Statements - Clauses 2-5

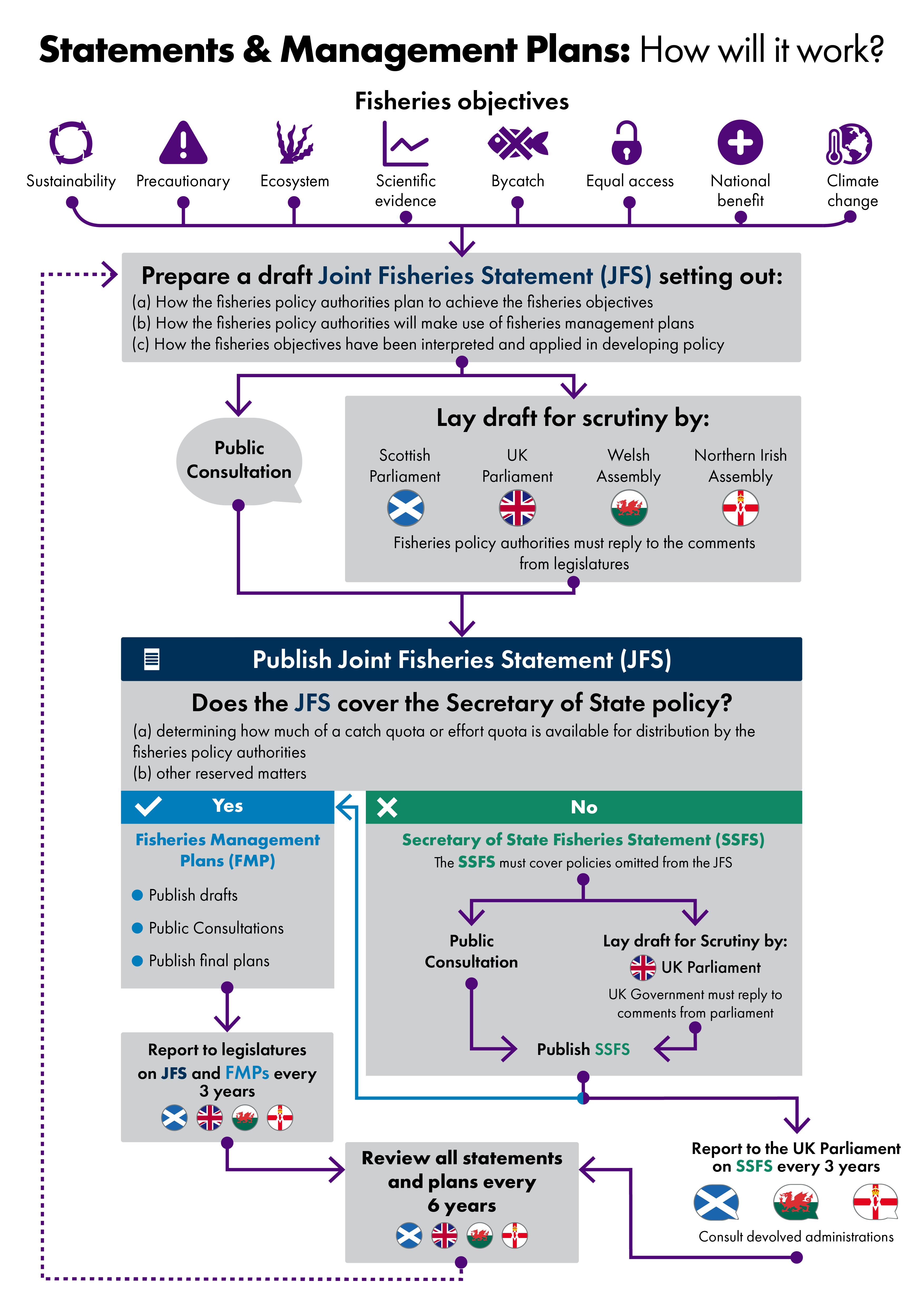

Clauses 2 to 5 of the Bill require two fisheries statements to be prepared and published. These statements will explain how the fisheries objectives have been interpreted by the UK fisheries authorities (the relevant fisheries authorities are set out in Box 1 above) and they will also set out policies for achieving, or contributing to the achievement of, the fisheries objectives. The process for how fisheries policy will be coordinated across the UK is set out in the flow chart below.

3.2.1 Joint Fisheries Statement

A Joint Fisheries Statement (JFS) must be prepared by all fishery policy authorities acting jointly.

The fishery policy authorities are the Secretary of State, the Scottish Ministers, the Welsh Ministers and the Northern Ireland department.

A draft of the JFS must be laid before all of the relevant legislative bodies, including the Scottish Parliament, prior to adoption and the Scottish Ministers are required to make a statement responding to any resolutions or recommendations made by the Scottish Parliament or its committees on the draft JFS during the scrutiny period.

A public consultation must also be carried out. The Bill requires that a JFS is prepared and published within 18 months from the date on which the Act is passed.

3.2.2 Secretary of State Fisheries Statement

The Bill also provides for a Secretary of State Fisheries Statement (SSFS).

Whereas in the 2017-19 UK Fisheries Bill, the SSFS appeared to be directed at developing policies relevant to England, the role of the SSFS in the new version of the Bill has significantly changed.

Clause 4 of the Bill requires the Secretary of State to prepare a SSFS on a "relevant Secretary of State policy" if those policies have been omitted from the JFS by the fisheries policy authorities. The two "relevant" Secretary of State policies identified in the Bill are:

the determination and distribution of catch quotas and effort quotas to the various fisheries administrations in the UK (the UK quota function); and

any reserved functions relevant to fisheries management.

The language of the Bill suggests that these matters may be addressed in the JFS, rather than in a SSFS, and Lord Gardiner (Con) confirmed during the second reading of the Bill that it was the “intention [of the Government] for all policies that achieve the objectives to be included in the [JFS].”1 Nevertheless, it is possible that the fisheries policies authorities will not be able to reach agreement on these specified matters, in which case the Secretary of State is under a duty to produce a SSFS.

The Bill contains no express requirement for the Secretary of State to consult the Scottish Ministers or to lay a draft SSFS before the Scottish Parliament. Rather, it is the UK Parliament which performs this scrutiny function.

The Secretary of State is, however, required to consult interested persons; i.e. such persons who they deem to be interested in, or affected by, the consultation draft, and members of the general public. The SSFS must be prepared and published within 6 months from the date on which the JFS is published.

3.2.3 Practical implications

All national fisheries authorities, including the Scottish Ministers, must exercise their functions in accordance with the policies contained in the JFS and the SSFS, unless a relevant change of circumstances indicates otherwise. Clause 10 applies the same requirement in relation to Fisheries Management Plans (see section 3.3 below). The Bill lists a number of relevant circumstances, including the international obligations of the United Kingdom, available scientific evidence, available evidence relating to social, economic or environmental elements of sustainable development, and the acts of other states that affect the marine and aquatic environment. This list is not exhaustive, and it is open to national fisheries authorities to invoke other relevant changes of circumstances, although they are required to publish a document describing the decision and the relevant changes of circumstances and how the relevant change of circumstances affected their decision.

Although not in the Bill, it may be possible for Scotland to prepare its own fisheries statement in addition to the JFS, for policies relevant to Scotland. Scotland’s National Marine Plan already includes certain policies relating to sea fisheries which will continue to be relevant to fisheries management in Scotland and these national policies may be supplemented by policies contained in regional marine plans.

Reports on the implementation of the JFS must be laid before the Scottish Parliament every three years. It must also be reviewed at least every six years. The same is required of Fisheries Management Plans (see section 3.3 below)

3.3 Fisheries Management Plans - Clauses 6-11

The JFS prepared under clause 2 of the Bill will also explain how the fisheries policy authorities propose to make use of fisheries management plans (FMPs) in achieving the fisheries objectives. The inclusion of FMPs is a new element of the Fisheries Bill introduced in January 2020 and they were not included in the previous version of the Bill.

A FMP is defined by the Bill as

a document, prepared and published under this Act, that sets out policies designed to restore one or more stocks of sea fish to, or maintain them at, sustainable levels.

FMPs may relate to one or more stocks of sea fish and they may be adopted for particular geographical areas. Where it is proposed to prepare a FMP, the JFS must specify which fisheries policy authorities will be responsible for this task; FMPs may either be prepared jointly by two or more fisheries policy authorities or the task of preparing a FMP may be delegated to a single fisheries policy authority. A fishery policy authority must carry out a public consultation on a proposed FMP prior to its adoption.

Further details of what is expected from FMPs are found in clause 6 of the Bill. The Bill explicitly requires a fisheries policy authority to specify whether the available scientific evidence is sufficient to make an assessment of the relevant stock’s maximum sustainable yield and if it is not, the FMP must either specify the steps to be taken to obtain such scientific evidence or state the reasons why it does not propose to obtain further scientific evidence. Alongside policies for maintaining stocks at, or restoring stocks to, sustainable levels, each FMP must also include indicators to be used for monitoring the effectiveness of the plan. Subsection 4 requires fisheries authorities to take a precautionary approach where scientific evidence is deemed not to be sufficient.

A form of FMP, known as a multi-annual plan (MAP), is already used in the CFP for certain stocks (Articles 9-10).1 MAPs for demersal stocks in the North Sea2 and stocks fished in Western Waters and adjacent waters3 have both been incorporated into domestic law as retained EU law and these instruments will continue to apply, subject to any modifications to make them workable as a matter of national law4, until replaced or amended. A recovery plan is also in place for European eel.i

3.4 Access to British fisheries and fishing licences - Clauses 12-22

Whilst in the EU, EU vessels have equal access to UK waters to fish and vice versa (Article 5 of the Common Fisheries Policy Regulation). Annex I also provides special access for certain vessels to UK waters within 6-12 nautical miles based on traditional fishing grounds.

These provisions of the CFP are revoked in Schedule 10 of the Bill, meaning that EU vessels will no longer have automatic access to UK waters at the end of the transition period.

In July 2017, the UK Government also announced it was withdrawing from the London Fisheries Convention which also allowed access for vessels from France, Belgium, Germany, Ireland and the Netherlands to UK waters within 12 nautical miles; this took effect on 1 February 2020.

Box 5. Access to UK waters under the Common Fisheries Policy

0-6 Nautical Miles - Non-UK vessels do not have access to the 0-6 nm area

6-12 Nautical Miles - fishing by non-UK vessels is restricted to those with historic rights, subject to quota of their flag state, under Common Fisheries Policy exemptions in Annex I of the CFP Regulation.

12-200 Nautical Miles - EU vessels and vessels from countries with which the EU has agreements, have access subject to quota.

Clause 16 sets out that a foreign boat is prohibited from fishing within British fisheries limits unless it has a licence. Subsection (3) and (4) of this clause provides the Secretary of State the power to add, remove or vary exceptions by regulations but only with the consent of the Scottish Ministers, Welsh Ministers and the Northern Ireland Department. Foreign vessels do not currently require such a licence. This will enable the regulation of foreign vessels through the imposition of licence conditions when fishing within British fishery limits1. Foreign vessels will continue to be allowed to enter British fisheries limits without a license for purposes recognised by international law, e.g. to exercise the right of freedom of navigation.

British fishing boatsi must also have a licence under Clause 14 to fish. The licensing scheme under Clause 14 and paragraph 7 of schedule 3 of the Bill replaces the existing licensing scheme under section 4 of the Sea Fish (Conservation) Act 1967 and associated regulations.

In terms of paragraph 7(1) of schedule 3, the Scottish Ministers may make provision about how licensing functions are to be exercised. They may also make provision as to the time when a sea fishing licence (or a variation, suspension or revocation of a sea fishing licence) has effect, or a condition attached to a sea fishing licence (or addition, removal or variation of such a condition) has effect. This replaces the powers conferred on Scottish Ministers under section 4 of the 1967 Act.

Furthermore, under paragraph 7(5) of schedule 3, the Scottish Ministers may by regulations make provision about the principles relating to conditions attaching to the licensing of fishing boats relating to the time spent at sea. This provision restates the power in section 4(6C) of the 1967 Act. Existing licenses will continue to have effect by virtue of Schedule 4 of the Bill.

Scottish Ministers may grant a licence to Scottish fishing boats to fish in any UK waters and to foreign fishing boats to fish in Scottish waters. Other UK fisheries administrations are responsible for licensing their own vessels and for licensing foreign vessels in their own waters. Therefore, on the face of the Bill, a foreign vessel may need a licence from more than one fisheries administration if it intends to fish in different parts of the UK, although Lord Gardiner confirmed during the second reading that

the fisheries administrations have agreed that the [Marine Management Organisation] will act as a single licensing authority and issue licenses to foreign boats on behalf of the four fishing administrations.2

British and foreign licences are different, but they may both impose conditions such as:

where a boat may fish,

periods of time a boat may fish ,

the type and quantity of fish that may be caught, and

the method of fishing that can be used.

Allocation of quota is managed separately.

In practice, licensing of foreign vessels is likely to take place within the broader framework of access arrangements agreed with other states through international negotiations (see Box 6).

3.5 Fishing opportunities for UK boats - Clauses 23-26

Clause 23 gives the Secretary of State the power to determine:

the maximum quantity of fish that may be caught by British fishing boats (catch quota)

the maximum number of days that British fishing boats may spend at sea each year (effort quota).

This provision refers to the total catch or effort of the UK fishing fleet as a whole. The Secretary of State must consult Scottish Minsters in determining this. Determination of fishing opportunities must also be carried out in accordance with the relevant Joint Fisheries Statement or Secretary of State Fisheries Statement; see sections above on this.

The Bill states:

A determination under subsection (1) may be made only for the purpose of complying with an international obligation of the United Kingdom to determine the fishing opportunities of the United Kingdom.

(bold added)

The Explanatory Notes say:

The provisions set out the Secretary of State function of determining the UK’s fishing opportunities, in accordance with the UK’s international obligations. These might arise under an agreement with the EU or with another coastal state. They might also arise because of the UK’s obligations under UNCLOS [United Nation Convention on the Law of the Seas] or as a member of a RFMO [Regional Fisheries Management Organisation].

Clause 26 imposes a duty on national authorities (i.e. Scottish Ministers) to ensure that fishing opportunities are not exceeded.

Box 6. Fishing opportunities for foreign boats

The Bill does not address fishing opportunities for foreign boats in UK and Scottish waters. A SPICe blog series discusses international fisheries negotiations in more detail.

3.5.1 Fishing opportunities and legislative consent

The UK Government views determination of fishing opportunities as a reserved function. The UK Government explained its position in relation to clause 18 (now clause 23) in a letter to the Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee on 4 March 2019 regarding the 2017-2019 UK Fisheries Bill:

The UK Government's view that the power in clause 18 does not relate to devolved matters is based on the fact that the determination of a UK amount cannot be within devolved competence because the power is not exercisable separately in or as regards Scotland. It could only be after the determination of the UK's fishing opportunities at a UK level and their division between the UK fisheries administrations that there would be an international obligation that related to Scotland which would then be within the competence of the Scottish Parliament and the responsibility of the Scottish Government to implement.

The Scottish Government disagreed. In the legislative consent memorandum of the previous version of the Bill, the Scottish Government states:

Whilst the United Kingdom is responsible in international law for compliance with its international obligations, it does not follow that it is the UK Government alone which is responsible for the measures required to implement and comply with those obligations in domestic law. Paragraph 7(2) of Schedule 5 to the Scotland Act 19987 explicitly provides that observing and implementing international obligations are not reserved matters.

...it would appear that clause 18 is a provision which legislates with regard to devolved matters and for a purpose which is within the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament – namely, in this case, the regulation of sea fisheries inside the Scottish zone and the regulation of Scottish fishing boats, whilst observing the UK’s international obligations in that regard...1

Giving evidence to the Environment Climate Change and Land Reform Committee on 4 December 2018, Mike Palmer, a Scottish Government official, explained the Scottish Government's view that -

making an international agreement is reserved, but

complying with and implementing an international agreement is devolved.

In a letter to the UK Government published on 4 December 2018, Fergus Ewing MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Rural Economy and Connectivity, states -

...this clause, as drafted, will have an unacceptable impact on the existing powers of Scottish Ministers. Therefore, to ensure that devolved competence is respected, I would ask that an amendment be made to Clause 18 to provide that any decisions made under Clause 18, insofar as they relate to Scotland, should only be taken with the consent of the Scottish Ministers.

(bold added)

The revised Bill makes no changes to clause 18 (now clause 23). In an article published by The Scotsman on 29 January 2020, the Cabinet Secretary is quoted as stating the following in response to the revised Bill:

[Ministers are] seriously concerned that Scotland still does not have its own place at international fisheries negotiations as a matter of right, something that we have long called for.

Schedule 5, Part 1, of the Scotland Act 1998 contains the following reservation (and exception) -

Box 7. Reserved functions in the Scotland Act 1998

7(1) International relations, including relations with territories outside the United Kingdom, the European Union (and their institutions) and other international organisations, regulation of international trade, and international development assistance and co-operation are reserved matters.

(2) Sub-paragraph (1) does not reserve—

(a) observing and implementing international obligations, obligations under the Human Rights Convention and obligations under EU law,

(b) assisting Ministers of the Crown in relation to any matter to which that sub-paragraph applies.

3.5.2 Distribution of fishing opportunities

After receiving fishing opportunities from the UK, each of the four UK Fisheries Administrations allocates quota to its fishing boats.

Clause 25 corrects Article 17 of the Common Fisheries Policy Regulation to make it operable in UK law. Article 17 requires that Member States distribute fishing opportunities domestically according to transparent and objective criteria including those of an environmental, social and economic nature. The previous version of the Bill only applied this requirement to the Secretary of State and the Marine Management Organisation. The revised version of the Bill expressly extends this obligation to the other fisheries administrations, including the Scottish Ministers.

The new provision will read:

Criteria for the distribution of fishing opportunities for use by fishing boats

When distributing fishing opportunities for use by fishing boats, the relevant national authorities shall use transparent and objective criteria including those of an environmental, social and economic nature. The criteria to be used may include, inter alia, the impact of fishing on the environment, the history of compliance, the contribution to the local economy and historic catch levels. Within the fishing opportunities available for distribution by them, the relevant national authorities shall endeavour to provide incentives to fishing vessels deploying selective fishing gear or using fishing techniques with reduced environmental impact, such as reduced energy consumption or habitat damage.

In this Article, “the relevant national authorities” means –

a. The Secretary of State,

b. The Marine Management Organisation,

c. The Scottish Ministers,

d. The Welsh Ministers, and

e. The Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs in Northern Ireland.

This obligation still leaves a large amount of leeway for fisheries administrations to determine how to allocate quota to individual vessels. Some coordination between UK fisheries administrations is achieved under the UK Concordat on Fisheries Management.

The Concordat is an agreement between the UK Administrations that sets out a number of arrangements for UK fisheries management. These include which UK fishing vessels each Administration will license and how UK quotas are allocated to, and may be transferred between, the four UK countries.

3.6 Grants - Clause 33

Clause 33 creates new powers for the Secretary of State to make grants or loans to the fishing and aquaculture industries. The purpose of the clause is to allow grant and loan schemes to be established to replace those previously provided by the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF) (see Box 8).

In the previous version of the Bill, these powers were extended to Wales and Northern Ireland but not to Scotland. Equivalent powers under clause 33 have now been conferred on Scottish Ministers in Schedule 6 of the revised Bill.

Box 8. The European Maritime and Fisheries Fund

The Common Fisheries Policy provides funding to support a transition to more sustainable fisheries and support for coastal communities through the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF). This runs from 2014 to 2020 and covers fisheries and aquaculture. The UK investment package for this period is €309m with an EU contribution of €243m1. This funding had been allocated as follows2 -

Scotland - €108 million

England - €97 million

Northern Ireland - €24 million

Wales - €15 million.

3.7 Charges - Clauses 34 & 35

Clause 34 creates new powers for the Secretary of State to allow the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) to impose charges on the fishing industry in England or on English boats. Scottish boats would be subject to the charges when carrying out activities subject to the jurisdiction of the MMO.

In the previous version of the Bill, these powers were extended to Wales and Northern Ireland but not to Scotland. Equivalent powers have now been conferred on Scottish Ministers in Schedule 7 of the revised Bill.

The powers enable Scottish Ministers to impose charges in respect of the operation of relevant marine functions relating to -

fishing quotas;

ensuring that commercial fish activities are carried out lawfully;

the registration of buyers and sellers of first-sale fish (fish which is marketed for the first time);

catch certificates for the import and export of fish.

3.8 Power to make provision about fisheries - Clause 36

Clause 36 enables the Secretary of State to make regulations on a wide range of technical matters currently regulated by the EU under the CFP. The Explanatory Notes state that the purpose of the power is "to allow the UK to meet its international obligations, conserve the marine environment and to adapt fisheries legislation, including the approximately 100 regulations of the CFP incorporated into UK law by the EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018."

The regulation making powers are very broad and make provision for -

implementing an international obligation of the UK relating to fisheries, fishing or aquaculture,

for a conservation purpose, or

for a fish industry purpose.

The Secretary of State can make regulations for the whole of the UK. This may be relevant, for example, on control issues where a level playing field may be required. The Secretary of State's power to legislate in areas within the competence of the Scottish Parliament or which modify functions of the Scottish Ministers is limited by the requirement to obtain the consent of the Scottish Ministers. However, regulations can be made by the Secretary of State that relates to the regulation of Scottish fishing boats within the British fishery limits but outside the Scottish zone without the consent of the Scottish Ministers.

Any regulations made under this power require the Secretary of State to consult with Scottish Ministers, Welsh Ministers, the Northern Ireland Department and such other persons likely to be affected by the regulations.

In the previous version of the Bill, these powers were extended to Wales and Northern Ireland but not to Scotland. Equivalent powers have now been conferred on Scottish Ministers in Schedule 8 of the revised Bill. The Scottish Ministers must consult the Secretary of State, the other Devolved Administrations, and such other persons as they consider appropriate before exercising these powers.

Any Scottish Statutory Instruments (regulations) made by the Scottish Ministers under the power in paragraph 1 of Schedule 8 would be subject to the affirmative procedure in the Scottish Parliament if they:

amend or repeal primary legislation;

amend article 17 of the Common Fisheries Policy Regulation;

impose fees;

create a criminal offence, increase penalties for criminal offences, or widen the scope of a criminal offence; or

confer functions or modify functions related to the regulation of UK producer or inter-branch organisations

In any other case regulations made under Schedule 8 would be subject to the negative procedure in the Scottish Parliament.

3.9 Power to make provision about aquatic animal diseases - Clause 38

Clause 38 provides an equivalent power to that in Clause 36 for the Secretary of State to make regulations about aquatic animal diseases. This is to allow for amendments to be made to retained EU law and other UK law by secondary legislation.

As with the power in clause 36, the Secretary of State's power to legislate in areas within the competence of the Scottish Parliament or which modify functions of the Scottish Ministers is limited by the requirement to obtain the consent of the Scottish Ministers. However, regulations can be made by the Secretary of State that relates to the regulation of Scottish fishing boats within the British fishery limits but outside the Scottish zone without the consent of the Scottish Ministers.

Any regulations made under this power require the Secretary of State to consult with Scottish Ministers, Welsh Ministers, the Northern Ireland Department and such other persons likely to be affected by the regulations, as the Secretary of State considers appropriate.

Schedule 8 gives equivalent regulation making powers to devolved administrations; i.e. the Scottish Ministers in Scotland. As with the power in clause 36, the Scottish Ministers must consult the Secretary of State, the other Devolved Administrations, and such other persons as they consider appropriate before exercising these powers.

Any Scottish Statutory Instruments (regulations) made by the Scottish Ministers under the power in paragraph 3 of Schedule 8 would be subject to the affirmative procedure in the Scottish Parliament if they:

amend or repeal primary legislation;

amend article 17 of the Common Fisheries Policy Regulation;

impose fees;

create a criminal offence, increase penalties for criminal offences, or widen the scope of a criminal offence; or

confer functions or modify functions related to the regulation of UK producer or inter-branch organisations

In any other case regulations made under Schedule 8 would be subject to the negative procedure in the Scottish Parliament.

3.10 Powers relating to the exploitation of sea fisheries resources - Clause 44

Clause 44 refers to Schedule 9 which confers powers on Scottish Ministers (as well as the Marine Management Organisation and Welsh Ministers) to make rules relating to the impact of fishing on marine conservation. This is to replace EU measures for the protection of the marine environment in the offshore region.

This area is executively devolved (see Box 9). In this case, the Bill provides powers for Scottish Ministers to make orders relating to the exploitation of sea fisheries resources in the Scottish offshore region for conserving -

marine flora or fauna,

marine habitats, or

geological features.

Box 9. What does it mean to be executively devolved?

This means the Bill provides powers to Scottish Ministers to execute functions in a reserved area, for example, to make orders in relation to marine conservation, marine planning and marine licensing in respect of the offshore region (12-200 nm).

Under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010, Scottish Ministers have powers to make Marine Conservation Orders (MCOs) to further the objectives of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in the Scottish marine area (up to 12 nautical miles from baselines). This can include prohibiting, restricting or regulating certain activities such as:

vessel movements and activity

interference or disturbance/damage to the seabed, or

the use of certain equipment and exploration activities.

However, at present, similar powers do not exist under the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 in relation to MPAs in the offshore region. The powers conferred under Clause 44 will allow Scottish Ministers to prohibit or restrict the exploitation of sea fisheries in the offshore region (12 nautical miles to 200 nautical miles or to the maritime boundary with a neighbouring state) for conservation purposes. Failure to comply with any order is a criminal offence.

Before making an order using these new powers, the Scottish Ministers must consult the Secretary of State and any other person they think fit (including any other fishery administration if the order may affect sea fisheries resources in an adjacent region). As well as orders to protect existing MPAs in the offshore region, the Bill permits the Scottish Ministers to make an interim order for the purpose of protecting any feature in a particular area if there are reasons to consider designating the area as a MPA and there is an urgent need to adopt conservation measures pending designation. Such an interim order may remain in force for up to 12 months and the need for the order must be kept under review.

These new powers replace the current process for establishing conservation measures in MPAs under Article 11 of the CFP Regulation, which is considered by some as being unsatisfactory.12

Box 10. Article 11 of the Common Fisheries Policy

Article 11 of the CFP sets out two scenarios for introducing conservation measures for the conservation of marine biological resources in offshore waters.

Scenario 1 (Article 11(1)): If measures to be adopted exclusively affect vessels of the Member State, the Member State can adopt measures under conditions set out in Article 11(1) of the CFP.

Scenario 2 (Article 11(2)-11(3)): If measures to be adopted affect a fishery where more than one Member State has a management interest, the Member State must submit a joint recommendation to the European Commission.

The joint recommendation should include the proposed measures, their rationale, scientific evidence in support and details of their practical implementation and enforcement. 3

The current process for establishing conservation measures under the CFP is lengthy due to the requirement for consultation and approval from other Member States. There are currently proposals for 18 offshore sites, published by Marine Scotland in April 2017. Development of these proposals began in 2013 and are currently awaiting approval from other Member States before the 6-month period for formal negotiation (Article 11(3)) can begin. A timeline for the proposals published in June 2017 anticipated the measures would be in place by 31 January 2018.4

Outside the CFP there is no requirement to seek approval from other Member States. Therefore, the new process under Clause 44 will likely facilitate measures to be adopted on shorter timescales, like those implemented under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010.

Orders made by the Scottish Ministers under new section 137A(1) (power to make orders for marine conservation in the Scottish offshore region) and 137C(11) (power to make interim orders for marine conservation in the Scottish offshore region) of the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009, as inserted by paragraph 21 of Schedule 9 of the Bill, are subject to the negative procedure in the Scottish Parliament.

3.11 Clauses not applicable to Scotland

Some clauses are not applicable to Scotland. They are mentioned here for completeness.

Clause 27 on the sale of English fishing opportunities. Clause 27 of the Bill allows the Secretary of State to make provision for the sale of English catch quota or effort for the calendar year, including through a competitive tender or auction scheme.

Clause 28-32 on discard prevention charging schemes in England. This will allow the Secretary of State to set up a scheme whereby fish caught in excess of quotas by holders of an English sea fishing license or a producer organisation that has at least one member who is the holder of an English sea fishing license could be subject to a charge. Authorities may only charge fishers who are registered under the scheme, and registration is voluntary. The Explanatory Notes state that this extends and applies to Scotland and the UK Government are therefore seeking consent. This is because there may be cases where English licensed vessels are members of Scottish producer organisations. This does not affect Scotland's ability to determine how it will deal with bycatch and discards. However, it is worth noting that currently all UK fishers are subject to the landing obligation; it is not clear how this will interact with a Scottish approach to bycatch and discards.

Clause 43 on legislative competence of the National Assembly for Wales, which amends the Government of Wales Act 2006.

4. Second reading

Second reading of the Bill took place in the House of Lords on 11 February 2020. Sustainability and conservation of the marine environment featured heavily in the debate. The section below summarises key issues raised.

4.1 Climate Change and Sustainability

Lord Grantchester (Lab), Baroness Young of Old Scone (Lab), Baroness Jones of Moulsecoomb (GP) and Baroness Jones of Whitchurch (Lab) all highlighted a lack of legally binding duties and targets for achieving fisheries objectives, including sustainable fish stocks and net-zero emission fishing fleets and duties to fish at sustainable levels.

Baroness Young of Old Scone (Lab) stated:

somewhere in the mix we need a legal duty on relevant public authorities to achieve these objectives and be accountable by publishing specific regular reports on their achievement of the objectives, not just on their activities.1

This is an issue that has carried over since the 2017-19 Fisheries Bill, and was also raised during second reading of that Bill in November 2018, as well as by commentators.2

Specific issues were raised regarding a number of the fisheries objectives related to climate change and sustainability.

Precautionary objective

Article 2(2) of the CFP Regulation states -

the maximum sustainable yield exploitation rate shall be achieved by 2015 where possible and, on a progressive, incremental basis at the latest by 2020 for all stocks.

In the UK Fisheries Bill, achieving the precautionary objective means that "exploitation of marine stocks restores and maintains populations of harvested species above biomass levels capable of producing maximum sustainable yield [MSY]" . Therefore, the UK objective does not incorporate the duty in the CFP to achieve MSY.

Peers commented on this during the second reading. Baroness Bakewell of Hardington Mandeville (LD) noted:

There is concern that a legal maximum sustainable yield for each stock...will not be achieved if scientific evidence is not used to determine what an individual stock’s MSY should be. Since there is currently no fail-safe mechanism for ensuring that the total allowance catch is not exceeded, just how will the MSY be arrived at and how will it be monitored and policed?1

Baroness Young (Lab) noted:

In the Bill we simply have an aspirational objective to achieve a healthy biomass of stocks, a rather woolly objective that is neither legally enforceable nor subject to any deadline, to be taken forward by way of a policy statement that the Bill says can be disregarded in a wide variety of circumstances. All that represents a potential regression in environmental standards.1

The UK Government, by contrast, has stated that:

The Bill commits the UK to sustainable fishing and setting legally binding plans to achieve Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) for all fish stocks. The UK is seeking a fairer share of quota, as a proportion of the existing sustainable catch, not an increase in fishing pressure on fish stocks.1

However, others have expressed concern that "seeking a fairer share of quota" could still lead to unsustainable fishing pressures. Griffin Carpenter, Senior Researcher at the New Economics Foundation commented in an article for The Ecologist regarding the 2017-19 Fisheries Bill:

But what if the EU’s concept of a ‘fair share’ and the UK’s concept of a ‘fair share’ exceed the available budget?

It is possible that neither party is overfishing from their own perspective - but adding 70 percent and 70 percent equals systematic overfishing.

[...]

As Norway, Iceland, the EU, and other parties have the power to set their own ‘fair share’, northern fish stocks are frequently overfished when negotiations break down, as seen more recently in the so-called cod, mackerel and herrings wars.

Sustainability objective

Baroness Worthington (CB) and Lord Teverson (LD) highlighted the contradictory aims of the sustainability objective (environmental and socio-economic) and expressed concern that short-term socio-economic aims have priority over long-term environmental sustainability.

This issue was also raised by Lord Dunlop (Con) who said:

The argument for going beyond the scientifically recommended quotas is that, by adhering to these quotas, the livelihoods of fishermen and communities are put at risk. In other words, in the trade-off between the different elements of sustainability, short-term gain has taken precedence over longer-term pain. By fishing more now, fishermen have good livelihoods today, but their descendants will not have this tomorrow. I therefore ask the Minister, in his reply, to explain to us how the trade-off between these elements of sustainability in the Bill will be calculated, and to assure us that short-term interests will not be placed ahead of the longer-term objective of ensuring that fish stocks are there for future generations.1

Lord Teverson (LD) suggested that the sustainability objective should be a stand-alone objective with other objectives moved elsewhere in the Bill including a separate socio-economic objective.

Lord Gardiner of Kimble's response states:

we have worked extremely closely with the devolved Administrations to establish fisheries objectives for the whole United Kingdom, for which we will set policies in the joint fisheries statement. [...] These policies will focus on key areas of fisheries management, both to protect the environment and to enable a thriving fisheries industry. It is important, in the Government's view, that each of the objectives is applied in a proportionate and balanced manner, when formulating policies and proposals. We have therefore committed to the joint fisheries statement explaining how the objectives have been interpreted and proportionately applied. 1

Climate objective

The new climate objective was largely welcomed; however, some peers raised the question of whether the objective is comprehensive. Baroness Young of Old Scone (Lab) and Baroness Worthington (CB) both argued that in addition to low-carbon fishing technology, the climate change objective (clause 1(1)(h)) should acknowledge the wider importance of restoring marine ecosystems for tackling the twin climate and biodiversity crises.

Baroness Worthington (CB), stated: