Revised UK Agriculture Bill 2020

This briefing considers the UK Agriculture Bill from a Scottish perspective. The Bill was introduced in the House of Commons on 16 January 2020. It follows on from the Agriculture Bill 2018 which was introduced in the House of Commons on 12 September 2018 but which fell at the end of the parliamentary session. Whilst the main purpose of the bill is to provide a legal framework which will underpin a new agricultural policy for England after Brexit, it also also makes provisions which will apply in Scotland.This briefing explains each section of the Bill, and examines, in greater detail, those sections which will apply to Scotland..

Executive Summary

The UK Agriculture Bill was introduced on 16 January 2020. It received its second reading on 3 February 2020, and the Committee Stage concluded on 5 March 2020. This Bill follows on from the 2017-2019 UK Agriculture Bill introduced in September 2018, which fell at the end of the previous Parliament. When comparing these two versions, this briefing refers to them as 'the 2019-2020 Bill' and 'the 2017-2019 Bill'.

As agriculture is a devolved policy area, some parts of this Bill apply in Scotland, while some do not. For example, the Bill makes provision for a new environmental land management scheme for England only, while making provision for UK-wide reporting on food security.

Much of the content of a future agricultural policy for Scotland is not contained in this Bill. The Scottish Government introduced the Agriculture (Retained EU Law and Data) (Scotland) Bill in November 2019. The Agriculture (Retained EU Law and Data) Scotland Bill (referred to in this briefing as 'the Scottish Agriculture Bill'), makes provision for an interim approach to agriculture policy for Scotland based on simplifying and improving retained EU law. The Scottish Government intends to bring forward new legislation in due course to make provision for a longer-term agricultural policy for Scotland.

While this briefing briefly goes through each section of the Bill, the analysis focuses on the implications of the Bill for Scotland. The House of Commons Library has produced a comprehensive briefing on the Bill as a whole.

Part 1 of the briefing describes the purpose of the bill.

Part 2 provides an overview of Brexit-related UK legislation, and what this means for Scotland.

Part 3 discusses what it means for agriculture to be devolved.

Part 4 outlines the differences between the 2017-2019 UK Agriculture Bill and the 2019-2020 UK Agriculture Bill.

Part 5 outlines the policy direction for England, as set out by the Bill.

Part 6 goes through each clause of the Bill.

Part 7 highlights the main issues raised at the second reading in the House of Commons on 3 February 2020.

Part 8 goes through the parts of the bill that apply in Scotland. These are:

Clause 17 - Food Security

Clause 27 - Fair Dealing Obligations

Clauses 28-30 - Producer Organisations

Clause 31 - Fertilisers

Clause 32 - Identification and Traceability of Animals

Clause 33 - Red Meat Levy

Clauses 36 and 37 - Organic Products

Clauses 40-42 - WTO Agreement on Agriculture

Part 9 outlines the Scottish Government's response.

Part 10 outlines the reception among Scottish stakeholders.

Part 11 provides a comparison between the UK Agriculture Bill and the Agriculture (Retained EU Law and Data) (Scotland) Bill. This section discusses the parallel provisions in each Bill, as well as the main difference between the bills: the UK Bill makes provision for a new long-term agricultural policy for England, while the Scottish bill is intended to make provision for a transition to a new agricultural policy, the details of which will be set out in further primary legislation.

Part 12 provides a discussion of trade and agricultural standards, as the main issue raised in the second reading.

Part 13 discusses a number of outstanding questions and issues for Scotland. These are:

Will the UK Agriculture Bill be the basis for a common framework on agriculture?

How will the possibility of changing regulatory standards in England affect Scotland's ability to keep pace with EU regulation?

How will the UK Agriculture Bill and the policy direction it sets for England affect Scotland's policy direction?

On what basis will funding for agriculture and land management be allocated?

1. Purpose of the Bill

The stated purpose of the Bill is to "establish a new agricultural system based on the principle of public money for public goods for the next generation of farmers and land managers."

It proposes to achieve this by making provision to:

ensure that funding can be provided for agriculture and related activities;

set out the future of direct payments once the UK leaves the EU;

provide for support for agriculture in exceptional market conditions;

allow for retained EU law to be amended;

report on UK food security;

provide for the collection and use of data from the agricultural supply chain;

allow for regulations to be made on fair dealing within the supply chain, marketing standards, organic products and classification of carcasses;

allow for the recognition of producer associations and set out their exemption from competition law;

allow requirements to be set for fertilisers;

create processes for the identification and traceability of animals;

allow for schemes to be set up to redistribute the Red Meat Levy between the four UK nations;

to make changes to rules on agricultural tenancies;

to allow regulations to be made with regard to UK compliance with the World Trade Organisation (WTO) Agreement on Agriculture; 1

The need for this Bill has arisen as a result of Brexit. Leaving the EU means that the UK will no longer be part of the EU Common Agricultural Policy. This departure has necessitated the development of new agricultural policies across the UK.

Much of the Bill is concerned with establishing a framework for a new agriculture policy in England, and applies to England only. However, some provisions apply in other parts of the UK.

The UK Government intends to seek legislative consent for various provisions which it considers would be within the competence of the Scottish Parliament, the National Assembly for Wales, or the Northern Ireland Assembly.

2. Brexit-related UK legislation

This section of the briefing provides some information on the impact of the UK's exit from the EU on law-making in devolved areas. It also examines the powers that Ministers have to make laws in devolved areas.

2.1 What does the UK leaving the EU mean for law making?

Many of the laws in the UK derive from its membership of the EU. These laws cover issues from workers’ rights to the labelling of food.

The UK left the EU on 31 January 2020. However, EU law will continue to apply during a transition period which will end on 31 December 2020.

For the purposes of legal continuity, the UK Government wishes to preserve, as far as possible, the legal position which exists immediately before the end of the transition period. This will be achieved by taking a "snapshot" of all of the EU law that applies in the UK at that point and bringing it within the UK's domestic legal framework as a new category of law, known as "retained EU law".

The creation of this new category of UK law was one of the main purposes of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018. The Act aims to ensure that the UK has the laws it needs after the end of the transition period. This could include, for example, the law on the nutrition and health claims made on food, or on ensuring environmental protection in marine areas.

The UK will be able to amend the policy underlying this retained EU law after the end of the transition period (i.e. with effect from 1 January 2021) by making new domestic laws (laws which apply across the UK or to any part of it).

For more on how domestic laws will be made see 'Making new laws in devolved areas after EU exit'.

2.2 Making new laws in devolved areas after EU exit

Some areas of law have always been determined at a UK level. For areas of law which are derived from the EU, such as agriculture, the UK must continue to comply with EU law until the end of the transition period on 31 December 2020.

From 1 January 2021 the UK will no longer be required to comply with EU law. Responsibility for policy in areas which were previously dealt with at an EU level will lie with the UK Government and/or the devolved governments.

Scottish Ministers will continue to have powers in devolved areas and the Scottish Parliament will continue to legislate for Scotland in respect of devolved matters. The UK Parliament has the power to pass law in all policy areas for the whole UK and it will continue to have that power. The UK Parliament will not normally pass primary legislation (an Act of Parliament) in devolved areas without seeking the consent of the devolved legislatures. This is through the process of legislative consent.

Prior to 2018, UK Ministers generally only had powers to make regulations (secondary legislation) in devolved areas for the purpose of giving effect to EU law. That law, and the policy behind it, had been decided through the EU legislative process.

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 gives UK Ministers power to make regulations in devolved areas for the purposes of amending laws so that they work effectively after the UK leaves the EU. The aim of these kinds of regulations is to achieve legal continuity after the end of the transition period.

The European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 goes further and gives UK Ministers the power to make secondary legislation (regulations), capable of changing policy in devolved areas.

UK Ministers will not normally make such regulations in devolved areas without the consent of Scottish Ministers. In some cases, such agreement is a legal requirement, but not in all. The Scottish Parliament cannot scrutinise secondary legislation laid before the UK Parliament. However, it has a clear interest in such legislation where it relates to devolved matters.

The Scottish Parliament can scrutinise Scottish Ministers' decisions to consent to regulations which are made by UK Ministers in devolved areas. A process for this is being agreed between the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament. A protocol is already in place for statutory instruments made to fix deficiencies (gaps, errors and unintended consequences) as a result of powers given to UK and Scottish Ministers under the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018.

2.3 Do Ministers have new powers to make law in devolved areas as a result of EU exit?

The European Union (Withdrawal Act) 2018 gives Scottish Ministers powers to amend the law in devolved areas by regulation (secondary legislation) so that Scottish laws work effectively after the UK leaves the EU and the transition period is complete. UK Ministers have powers under the European Union (Withdrawal Act) 2018 to amend the laws in the UK, including Scottish laws, so that they work effectively after the UK leaves the EU. These powers have been conferred concurrently, meaning that either UK Minsters or the Scottish Ministers can make the regulations.

In some cases where the UK Government and the Scottish Government wish to pursue the same policy objective, the Scottish Government can ask the UK Government to lay statutory instruments that include proposals relating to devolved areas of responsibility. The UK Government can also make regulations in devolved areas without Scottish Ministers asking them to. UK Ministers will not normally make such regulations in devolved areas without the consent of the Scottish Ministers. That agreement is a legal requirement in some cases, but not in all.

The changes made by these kind of regulations are often technical and are there, in many cases, to achieve legal continuity. In some cases, the changes are very minor – removing references to EU institutions, for example. In other cases they are more significant - such as changes in regulatory requirements. The powers to make these kind of regulations are mainly time limited.

The European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 does, however, give UK and Scottish Ministers a suite of new powers in devolved areas that go beyond correcting deficiencies to achieve legal continuity. These powers have been conferred concurrently, meaning that either UK Ministers or Scottish Ministers can make the regulations. The suite of concurrent powers includes:

powers to implement long term obligations for the recognition of citizens' rights under the Withdrawal Agreement

powers to deal with separation issues such as the regulation of goods placed on the market

powers to implement the Ireland/Northern Ireland protocol.

There are other powers created or amended in the regulations made under the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 and also powers in other Brexit related legislation, such as the Direct Payments to Farmers (Legislative Continuity) Act 2020. Some of these powers may be used to make regulations which change policy. The powers are generally not time limited.

2.4 What is the significance of this Bill in the post EU exit legislative landscape?

This Bill is a direct result of the UK's exit from the EU, because policy in this area was previously set at EU level.

If new law was not made in this area then the legal position from 1 January 2021 would be as provided for under retained EU law.

This Bill sets a framework for a new agricultural policy to apply to England as well as provisions extending to devolved nations from 1 January 2021.

2.5 Does this legislation relate to common frameworks?

In many policy areas, EU laws have ensured that there is a consistent approach across the UK, even where these policy areas are devolved. This is because the UK and all of its governments have had to comply with EU law. In effect, this compliance has meant that the same policy has been followed.

The UK left the EU on 31 January 2020. There is now a transition period until 31 December 2020. Through the transition period the UK will continue to comply with EU law. After the end of the transition period, there is the possibility of policy divergence because the UK Government and the devolved administrations within the UK will no longer need to comply with EU law. Common frameworks can be developed so that rules and regulations in certain areas remain the same, or at least similar, across the UK. The UK Government has set out that it anticipates that a number of areas within agricultural policy (including agricultural support, zootech [animal breeding and genetics] , fertilisers and organics) will be the subject of a common framework.1

A common framework is an agreed approach to a particular policy, including the implementation and governance of it. Common frameworks will be used to establish policy direction in areas where devolved and reserved powers and interests intersect. Developments in common frameworks will be one of the factors which determines how Scotland and the rest of the UK will interact post EU exit.

Some common frameworks may be legislative but it is anticipated that the majority will be non-legislative. That means that they will be agreed through memorandums of understanding, concordats and so on, rather than being set out in primary legislation.

There may, however, be provision made in primary legislation which relates to a common framework. It is likely that some provisions made in this Bill will form part of common frameworks on agriculture. Similarly, some regulations (secondary legislation) are likely to make provision which is linked to common frameworks. Until common frameworks are explicitly developed, and details are shared by the UK and Scottish Governments, it is unclear what the broader extent of agricultural common frameworks will be.

As part of its scrutiny role, the Parliament needs to be able to consider the Scottish Government’s approach to, and development of, common frameworks. The Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament are therefore working together to produce a protocol for the sharing of information on common frameworks.

The committees of the Scottish Parliament will lead on scrutiny of common frameworks in their policy area.

Further information on common frameworks can be found on SPICe’s post-Brexit hub.

3. What does it mean for agriculture to be devolved?

Agriculture is a devolved policy area; the Scottish Ministers are responsible for the direction and design of agricultural policies for Scotland. Under the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), Scottish Ministers are responsible for determining the variable elements of the CAP. For example, deciding how much money is transferred from Pillar 1 (direct payments) to Pillar 2 (rural development) (see Box 1) and the design of the Scottish Rural Development Programme. The European Parliament states:

"A higher degree of flexibility [in Pillar 2] (in comparison with the first pillar) enables regional, national and local authorities to formulate their individual seven-year rural development programmes based on a European ‘menu of measures’. Contrary to the first pillar, which is entirely financed by the EU, the second pillar programmes are co-financed by EU funds and regional or national funds." As such, the Scottish Government is also responsible for setting the co-financing rate at which Scotland will contribute to the Scottish rural development budget.

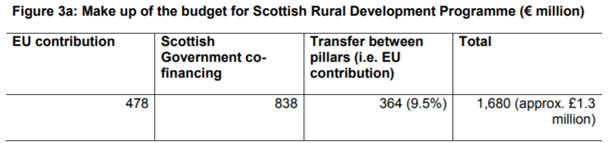

EU member states have the opportunity to transfer up to 15% of their Pillar 1 budget into Pillar 2.1 Scotland chose to transfer 9.5%.  Kenyon, W. (2017, February 23). Agriculture and Brexit in Ten Charts. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/ResearchBriefingsAndFactsheets/S5/SB_17-12_Agriculture_and_Brexit_in_10_Charts.pdf [accessed 29 January 2020] |

|---|

What will happen at the end of the transition/implementation period?

After the transition/implementation period, agriculture will continue to be devolved. However, there are policy areas which impact the agricultural sector, such as competition regulation and international trade, which are reserved. These were the subject of debate during the passage of the 2017-2019 UK Agriculture Bill. In addition, the 2020 Bill makes new provision in relation to Scotland, for which the UK Government is seeking consent from the Scottish Parliament. This is explored further below.

4. Differences between the 2017-19 Bill and 2019-2020 Bill

In comparison to the 2017-2019 UK Agriculture Bill (as amended in Public Bill Committee), the 2019-2020 Bill:

pays increased attention to soil quality (Part 1, Clause 1(1)(j)))

pays increased attention to genetic diversity (Part 1, Clause 1(1)(g) &(i))

pays increased attention to food production (Part 1, Clause 1(4))

makes provision for multi-annual assistance plans to be laid before Parliament (Part 1, Clause 4).

has removed Clause 7 of the 2017-2019 Bill (as amended in Public Bill Committee) which conferred a power to reduce the direct payments ceilings for England in 2020 by up to 15% .

makes provision which allows the Secretary of State to remove or reduce burdens to farmers by modifying existing legislation, including a new specific reference to cross-compliance rules. (Part 1, Clauses 9 and 14)

makes provision to monitor food security for the whole of the UK (Part 2, Clause 17)

makes new provision on fertilisers, including the power to make regulations for new assessment processes for fertilisers (Part 4, Clause 31)

makes new provision for the identification and traceability of animals (Part 4, Clause 32)

includes provisions to redistribute the Red Meat Levy (though this was subsequently added during the passage of the 2017-2019 Bill) (Part 4, Clause 33)

makes new provision on agricultural tenancies for England (Part 4, Clause 34)

makes new provision on organic products (Part 5, Clause 36).

5. Policy direction for England

The UK Agriculture Bill makes provision for a new direction of travel for agricultural policy in England. Clause 1 gives power to the Secretary of State to give financial assistance for a number of purposes. Current agricultural policies allocate the majority of funding in the form of direct payments based on the number of hectares that are owned and managed, for the purpose of income support to farmers. By contrast, Clause 1 specifies a number of environmental, social, and animal welfare purposes, in addition to improving the productivity of producers, for which financial assistance can be given.

The Bill also provides for an agricultural transition period, phasing out area-based direct payments over seven years, starting from 2021. The Bill includes new powers for the Secretary of State to do this, and to introduce interim measures as part of the transition, such as delinked payments, which 'delink' the payment entitlement from the need to manage the land for farming.

This reflects the new direction of travel for English agriculture policy, as set out in the UK Government consultation, 'Health and Harmony' in February 2018. The consultation received over forty thousand responses, and the responses were analysed by the UK Government. While the consultation was held during a previous government, similar intentions from the current government were set out in the Queen's Speech in December 2019. There, it was stated that the purpose of a new agriculture bill would be to:

"Replace the current subsidy system, which simply pays farmers based on the total amount of land farmed, and instead reward them for the work they do to enhance the environment, improve animal welfare and produce high quality food in a more sustainable way.

"Deliver on the Government’s manifesto commitments to support farmers and land managers to ensure a smooth and phased transition away from the bureaucratic and flawed CAP to a system where farming efficiently and improving the environment go hand in hand.

"Set out the framework for a new Environmental Land Management scheme, underpinned by the principle of ‘public money for public good’."1

Beyond these provisions, much of the detail of a new English agricultural policy and regulatory framework, and the specific terms of the transition, will be brought forward in regulation. For example, the Secretary of State has the power, by regulation, to modify retained EU law on direct payments and rural development, to provide for phasing out direct payments, to remove aid for fruit and vegetable producer organisations, to establish fair dealing obligations for agricultural producers, and so on. In many ways therefore, much of the detail remains to be set out.

The UK Government released two documents containing more detail on the future Environmental Land Management scheme for England in February 2020, one Policy and Progress Update, and one Policy Discussion Document. The UK Government invited the public to respond with their views.

The documents set out details for a three-tiered scheme to support land managers to carry out specific actions. They also provide some details of the ongoing tests and trials of new approaches, and a planned national pilot for the new scheme. The documents also provide more information on the planned transition to a new system.

English stakeholders have reacted in a variety of ways. National Farmers Union president Minette Batters stated

I'm pleased that the government has clearly listened to many of the concerns we raised with the Bill in the last Parliament and has acted to ensure the vital role of farmers as food producers is properly valued.

However, farmers across the country will still want to see legislation underpinning the government’s assurances that they will not allow the imports of food produced to standards that would be illegal here through future trade deals.

We will continue to press the government to introduce a standards commission as a matter of priority to oversee and advise on future food trade policy and negotiations.

It is encouraging to see that the Agriculture Bill now recognises that food production and caring for the environment go hand-in-hand. Farmers are rightly proud of their environmental efforts and it is crucial this new policy recognises and rewards the environmental benefits they deliver, both now and in the future.

National Farmers Union. (2020, January 17). Agriculture Bill reintroduced - hear from the President. Retrieved from https://www.nfuonline.com/news/latest-news/agriculture-bill-reintroduced-today-hear-from-the-president/ [accessed 28 January 2020]

Likewise, Thomas Lancaster from the RSPB stated in a blog for Wildlife and Countryside Link, the network body for environmental NGOs:

We are pleased that the core principle of ‘public money for public goods’ which was proposed in the early version of the bill, has been retained: this is the idea that payments to farmers should move away from the area of land they own or rent, and toward the environmental and cultural benefits that the land can provide and society needs.

[...]

There are obviously gaps, and we will be working to fill them as the bill makes its way through parliament. The most concerning is a lack of assurance around trade policies and import standards. Farming and environment organisations speak with one voice when we say that it is crucial that imports of food under future trade policies are held to UK standards.

Lancaster, T. (2020, January). Agriculture Bill 2020: Do good things come to those who wait?. Retrieved from https://www.wcl.org.uk/agriculture-bill-2020-do-good-things-come-to-those-who-wait.asp [accessed 28 January 2020]

The provisions in this Bill won't apply immediately. Payments will continue much the same as under the EU Common Agricultural Policy during what is called the 'implementation period', which lasts until the end of 2020, as a result of the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement and the Direct Payments to Farmers (Legislative Continuity) Act 2020. The provisions in this Bill will come into force following the implementation period (from 1 January 2021).

The new policy set out by the Bill will not apply in Scotland. However, agricultural support is one area that has been identified as needing a common policy frameworks across the UK. It is not clear how the development of a new English agriculture policy will impact the development of common frameworks for agriculture. A discussion on the questions that arise from this is included below in the section "Will the UK Agriculture Bill be the basis for a common framework on agriculture?"

6. The Bill

The following sections give an overview of the clauses of the Bill.

6.1 Part 1 - Financial Assistance

This Part of the bill gives the Secretary of State powers to:

give financial assistance (to replace common agricultural policy support)

set and modify the conditions on the assistance

create multi-annual plans for assistance

allow checking, enforcing and monitoring of funds and conditions.

6.1.1 Chapter 1 - New Financial Assistance Powers (applies in England only)

Clause 1 gives powers to the Secretary of State to provide financial assistance for -

managing land or water in a way that protects or improves the environment

supporting public access to and enjoyment of the countryside, farmland or woodland and better understanding of the environment

managing land or water in a way that maintains, restores or enhances cultural heritage or natural heritage

mitigating or adapting to climate change

preventing, reducing or protecting from environmental hazards

protecting or improving the health or welfare of livestock

conserving native livestock, native equines or genetic resources relating to any such animals

protecting or improving the health of plants.

Conserving plants grown or used in carrying on an agricultural, horticultural or forestry activity, their wild relatives or genetic resources relating to any such plant

Protecting or improving the quality of the soil

starting, or improving the productivity of, an agricultural, horticultural or forestry activity

Supporting ancillary activities carried on, or to be carried on, by or for a producer.

The clause also specifies that in devising assistance schemes, the Secretary of State "must have regard to the need to encourage the production of food by producers in England and its production by them in an environmentally sustainable way."

Clause 1 specifies that it applies only in relation to England.

Clause 2 gives wide ranging powers relating to the form of financial assistance, the conditions attached to it, and the information that must be provided by recipients. Detail will be set out in regulation.

Clause 3 gives wide ranging powers relating to checking, enforcement and monitoring of financial support and the conditions attached to it. Detail will be set out in regulation.

Clause 4 is new for the current iteration of this Bill, and places a duty on the Secretary of State to, "from time to time" prepare a "multi-annual financial assistance plan", which will provide details about how the Secretary of State will use the powers in the above sections.

Clause 4 specifies that the plan must specify the plan period, strategic priorities, and describe the financial assistance schemes. The first plan period will be for seven years from 1 January 2021, and subsequent plan periods may not be shorter than 5 years. The plan must have regard to the strategic priorities in determining the budget for financial assistance schemes.

Clauses 5 & 6 places duties on the Secretary of State to report annually to the UK Parliament on the amount of financial assistance given, and outlines the requirements for such a report (Clause 5) and to monitor the impact of financial assistance (Clause 6). In monitoring the impact of financial assistance, the Secretary of State must monitor the impact of each financial assistance scheme, and "make reports on the impact and effectiveness of the scheme (having had regard to the monitoring)". Clause 6 does not specify how frequently such monitoring and reporting should occur, beyond what "the Secretary of State considers appropriate".

6.1.2 Chapter 2 - Direct Payments after EU exit (applies in England only)

The Bill states that the agricultural transition period away from the CAP and to a domestic agricultural policy in England will be for seven years starting with 2021. This chapter enables regulations to be made for -

The basic payment scheme (BPS) to be modified, including by ending greening before the end of the transition period

Phasing out direct payments for all or part of the transition period

Making delinked payments (payment no longer linked to how much land is owned or managed)

Defining what, how much, who receives a delinked payment

The payment of a lump sum in lieu of direct payments to which a land manager may have been entitled.

Clause 7 sets out relevant definitions in relation to the basic payment scheme.

Clause 8 provides for seven-year agricultural transition period for England from 2021, and for the termination of direct or delinked payments.

Clause 9 confers power on the Secretary of State to modify legislation governing the basic payment scheme in relation to England. This power was included in the previous version of this Bill; however, the purposes for which the Secretary of State may modify these provisions have been amended.

The Secretary of State may make changes for the purpose of:

Simplifying the administration of the scheme

Removing provisions which serve no purpose

Securing that a sanction or penalty imposed under the scheme is appropriate and proportionate

Limiting the application of the scheme to land in England only

Removing or reducing burdens "on persons applying for, or entitled to, direct payments under the scheme or otherwise improving the way that the scheme operates in relation to them". "Burdens" are defined as (a) a financial cost; (b) an administrative inconvenience; or (c) an obstacle to efficiency, productivity or profitability.

On the last point, it is important to note that the "legislation covering the basic payment scheme" includes the Direct Payments Regulation, and its subordinate legislation.

Clause 9 also makes provision to end greening payments in relation to England "so long as that provision does not reduce the amount of direct payment to which a person would have been entitled had that provision not been made."

These changes can be made under the negative resolution procedure.

Clause 10 confers the power to provide for the continuation of the basic payment scheme beyond 2020, but only until the Government brings in delinked payments, or until direct payments are phased out at the end of the agricultural transition period.

Clause 11 confers the power to phase out direct payments during the agricultural transition period.

Clause 12 confers the power to make so-called "delinked" payments. The explanatory notes state that this clause

provides the power to the Secretary of State to delink Direct Payments from land. With delinked payments, there would be no obligation for the recipient of the payments, during the agricultural transition period, to remain a farmer. This will be called 'delinking' payments because the current connection between the value of the payment and the area of land for which it is claimed will be broken

UK Government. (2020, January 16). Agriculture Bill - Explanatory Notes. Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/58-01/0007/en/20007en.pdf [accessed 20 January 2020]

This clause confers power on the Secretary of State, by regulation, to introduce delinked payments in place of direct payments under the basic payment scheme, but not before 2022. The Secretary of State must specify the rules for receiving these payments, how they are calculated, and so on.

Clause 13 confers power on the Secretary of State, by regulation, to provide for lump sump payments in lieu of basic payments or delinked payments. Opting for a lump sum would mean that the recipient forfeits continued direct or delinked payments.

6.1.3 Chapter 3 - Other Financial Support After EU Exit (applies in England only)

Clause 14 makes general provision connected with payments to farmers and other beneficiaries. It allows the Secretary of State, by regulation, to modify the Horizontal Regulations (Regulation (EU) No 1306/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 on the financing, management and monitoring of the common agricultural policy) and subordinate legislation relating to it.

The Secretary of State may do so for the purpose of:

ensuring that any provision of the legislation ceases to have effect

simplifying the operation of any provision and make it more efficient or effective

removing or reducing burdens to applicants or recipients, or improving the operation of the legislation in that respect

Securing that sanctions or penalties imposed by such legislation is appropriate and proportionate.

It is important to note that the Horizontal Regulations and its subordinate legislation is responsible for setting out the rules for cross-compliance. Cross-compliance is a sanction mechanism, by which farmers who do not adhere to cross-compliance rules (more information on what these rules are can be found on the European Commission's website) may have their payments reduced. Cross-compliance includes both statutory requirements provided for under other aspects of EU law, as well as additional good management requirements for the environment, animal and plant health and animal welfare, as set out in the Horizontal Regulations. This is discussed in greater detail in the section on Trade and Standards below.

Clause 15 confers power on the Secretary of State, by regulation, to terminate aid to fruit and vegetable producers in England.

Clause 16 confers power on the Secretary of State, by regulation, to "modify or repeal retained EU legislation relating to Rural Development in England"1. The clause will allow the Secretary of State to make regulations to adjust contract lengths, extend contracts with fewer restrictions, or "be converted or adjusted into new agreements set up under Section 1" of the Bill.1 The current rural development programme may also be extended, its budget increased, and currency expressed other than in Euros. The Explanatory Notes clarify that new schemes cannot be introduced under this clause, this is covered in Clause 1.

6.2 Part 2 - Food and Agricultural Markets

6.2.1 Chapter 1 - Food Security (applies to whole of UK)

Clause 17 places a duty on the Secretary of State to report on food security to the UK Parliament at least once every five years. They must report on the whole of the UK, and provide "an analysis of statistical data related to food security". The data analysed in the report may include data on:

global food availability

supply sources for food

resilience of the supply chain for food

household expenditure on food

food safety and consumer confidence in food.

The UK Government is seeking consent from the Scottish Government for this clause to apply to Scotland.

6.2.2 Chapter 2 - Intervention in Agricultural Markets (applies in England only)

Clause 18 enables the Secretary of State to make a declaration stating that exceptional market conditions exist under certain conditions.

Clause 19 enables the Secretary of State to intervene in markets in the event of exceptional market conditions. This part allows the Secretary of State to react to "severe market disturbance, or the threat of such a disturbance"1 , which would have a significant effect on agricultural producers in England.

In such circumstances -

financial assistance may be given

power to modify retained direct EU law to allow public intervention and aid for private storage, may be used. These powers are conferred by Clause 20. Corresponding provisions for Scotland are made in the Scottish Agriculture Bill.

The Explanatory Notes state that these clauses do not extend to other exceptional events (e.g. animal disease, weather) unless they result in actual or threatened market disturbance.1

6.3 Part 3 - Transparency and Fairness in the Agri-Food Supply Chain

6.3.1 Chapter 1 - Collection and Sharing of Data (applies in England only)

Clause 21 makes provision to require actors in the agri-food supply chain to provide information on their activities. This relates only to activities taking place in England; corresponding provisions for activities taking place in Scotland are included in Section 13 of the Scottish Agriculture Bill.

Clause 22 defines agriculture supply chain, and uses the same definitions as the Scottish Agriculture Bill mentioned above. However, the UK definition does not except fish, while the Scottish Bill does.

Clause 23 provides that the requirement to provide information under Clause 21 must specify the purpose for which information is processed, and provides a list of acceptable purposes.

Clause 24 states the requirements on the Secretary of State to publish, and invite comments on, a draft requirement, and specify who the requirement will affect.

Clause 25 states what can and must be included in a requirement to provided information, and sets out limitations on processing information. These provisions are very similar to those made in the Scottish Agriculture Bill.

Clause 26 sets out enforcement rules for information requirements. These provisions are the same as those made in the Scottish Agriculture Bill.

6.3.2 Chapter 2 - Fair Dealing with Agricultural Producers and Others in the Supply Chain (applies to whole of UK)

Clause 27 deals with fair dealing obligations of business purchasers of agricultural products. The Secretary of State may make regulations to impose obligations to ensure fair contracts between business purchasers and agricultural suppliers.

6.3.3 Chapter 3 - Producer Organisations (applies to whole of UK)

Clause 28 makes provision for recognition for producer organisations, interbranch organisations (organisations for collaboration between producers and different parts of the supply chain) and associations of producer organisations. The clause states that organisations of agricultural producers, producer organisations or agricultural businesses that meet respective conditions may apply to the Secretary of State for recognition as a producer organisation, association of producer organisations, or interbranch organisation. The Secretary of State may, by regulation, specify additional conditions, and make further provision about applications to become a producer organisation.

Clause 29 makes provision for Schedule 2 of the Bill to amend Schedule 3 of the Competition Act 1998. The Clause sets out the exemptions for producer organisations from competition law, and allows the Secretary of State to make further provision in relation to recognised organisations.

Clause 30 makes additional provision under clauses 28 and 29, allowing the Secretary of State to delegate functions to other bodies and make sector-specific provision, and also sets the procedure for creating new regulations under the above two clauses.

6.4 Part 4 - Matters Relating to Farming and the Countryside

Fertilisers (applies to whole of UK)

Clause 31 amends the definition of a fertiliser under section 66 of the Agriculture Act 1970 to enable a broader range of materials to be regulated as a fertiliser in the UK. It also amends section 74A of the Agriculture Act 1970 to enable the regulation of fertilisers on the basis of their function. This will allow different requirements to be set, for example, for biostimulants, soil improvers and traditional mineral fertilisers to ensure the safety and quality of the various types of products marketed as fertiliser in the UK.

Clause 31 also allows for regulations to set out an assessment, monitoring and enforcement regime for ensuring the compliance of fertilisers with composition, content and function requirements and for mitigating other risks to human, animal or plant health or the environment presented by fertilisers. However, the power to make regulations under section 74A is exercisable only by the Scottish Ministers, having been transferred to the Scottish Ministers by virtue of section 53 of the Scotland Act 1998.

The UK Government intends to seek the legislative consent of the Scottish Parliament to this provision because it falls within devolved competence.

Identification and Traceability of Animals (applies to whole of UK)

Clause 32 makes provision for the identification and traceability of animals. As set out in the Explanatory Notes:

Clause 32 amends the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006 (NERC Act 2006) to allow for new data collecting and sharing functions. This will include the running of a database to be assigned to a board established under that Act and to enable the assignment f functions relating to the means of identifying animals. It will amend section 8 of the Animal Health Act 1981(AHA 1981) to reflect advancements in animal identification technology and to provide that orders made under section 8 will bind the Crown...The purpose of the clause is to prepare for the introduction of a new digital and multi-species traceability service, the Livestock Information Service (LIS), based on a database of animal identification, health and movement data.

UK Government. (2020, January 16). Agriculture Bill - Explanatory Notes. Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/58-01/0007/en/20007en.pdf [accessed 20 January 2020]

The UK Government intends to seek the legislative consent of the Scottish Parliament to these provisions because they are within devolved competence.

Red Meat Levy (applies to whole of UK)

Clause 33 makes provision for red meat levy payments to be made between levy bodies in the four UK nations. The red meat levy is the payment collected at slaughterhouses per head of pig, cattle and sheep. The levy is collected and spent by the levy body in each country (in Scotland's case, Quality Meat Scotland) for the benefit of red meat producers in that country.

Under this clause, a scheme may be put into place which administers the redistribution of red meat levy payments. The clause specifies how and when payment is to be made between levy bodies, how to calculate the distribution of payments, and related rules.

The UK Government intends to seek the legislative consent of the Scottish Parliament to these provisions because they are within devolved competence.

Agricultural Tenancies (applies only to England)

Clause 34 makes provision in relation to agricultural tenancies in England. It relates to the rights and obligations of tenants.

6.5 Part 5 - Marketing Standards (England only), Organic Products (all UK), and Carcass Classifications (England only)

Clause 35 gives power to the Secretary of State, by regulation, to set marketing standards for products marketed in England. These powers are largely mirrored in the Scottish Agriculture Bill, and relate to the same sectors. There are two small differences between the two:

Clause 35(2)(j) excludes "live poultry" in addition to poultrymeat and spreadable fats from provisions relating to the "place of farming or origin" in regulations made under these powers. Section 8(1)(j) in the Scottish Agriculture Bill does not.

Regulations made under this Clause are subject to the affirmative resolution procedure in the UK Agriculture Bill, while any Scottish regulations would be subject to the negative procedure.

Clauses 36 and 37 deal with the power to create regulations for organic products. Clause 36 confers the power to make regulations on the certification of organic products, activities related to organic products, and persons or groups of persons carrying out activities relating to organic products. Regulations made under this clause may set rules for organic certification, marketing, import, export and sale, and about the "objectives, principles and standards of organic production".

The UK Government is seeking consent from Scottish Ministers to legislate for organic products on behalf of the whole of the UK, and, as specified in Clause 37, to confer power on "Scottish Ministers, if and to the extent that provision made by the regulations would be within the legislative competence of the Scottish parliament if contained in an Act of that Parliament".

Clause 38 confers power on the Secretary of State to bring forward regulations to make provision about the classification, identification and presentation of cattle, pig and sheep carcasses by slaughterhouses in England. This mirrors similar provision in the Scottish Agriculture Bill. However, Scottish regulation would be subject to the negative procedure, while English regulation would be subject to affirmative resolution procedure.

Clause 39 confers power on the Secretary of State to reproduce modifications made under Clause 35 on marketing standards for the wine sector. This clause will apply in Scotland.

6.6 Part 6 - WTO Agreement on Agriculture (applies to whole of UK)

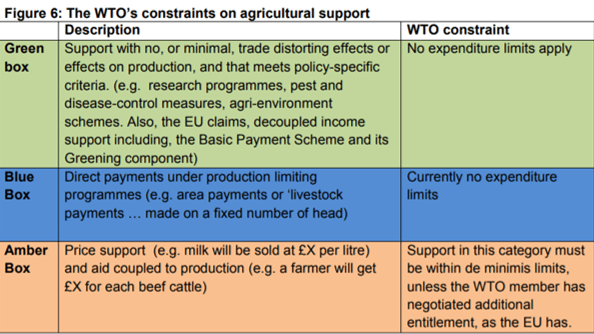

Clauses 40-42 confer power on the Secretary of State to make regulations for securing the UK's compliance with the World Trade Organisation's Agreement on Agriculture (WTO AOA). The WTO AOA is an international treaty that sets rules for trade in agricultural products. The AOA covers market access, domestic support and export competition (e.g. use of export subsidies).1 These clauses relate to domestic support for agriculture.

Under the AOA, support schemes are classified into different categories - green box, amber box and blue box -depending on their capability to distort trade. There are no limits on blue and green box forms of agricultural support. There are limits on amber box forms of support - price support and aid coupled to production. Scotland is currently the only country within the UK providing coupled support (where support is linked to, for example, the number of cattle a farmer has) via the Scottish Suckler Beef Support Scheme and the Scottish Upland Sheep Support Scheme2.

However, some WTO members are allowed to exceed the “de minimis” limits in the Amber box because historically they have provided this type of support. The EU is allowed to exceed these limits, and has Amber Box entitlements of €72.4 billion. As part of the EU and the CAP, the UK shares this entitlement. Indeed, total EU CAP payments are well within this limit4.

Outwith the EU, new domestic agriculture policy will be constrained by the WTO Agreement on Agriculture rules.

More information on these rules and limits can be found on the WTO website.

These clauses make provision to ensure that the UK as a whole comply with these rules, by classifying different domestic support schemes into different categories, and setting maximum levels of support in accordance with the UK's allowance. Therefore, regulations may set a limit on the amount of domestic support that may be given to the UK as a whole, and set limits for England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland on the amount of support that may be given in that country. Different limits may be set for different countries, and regulation may specify whether different kinds of domestic support do not count towards the limits set.

Clause 42 specifies that these powers allow the Secretary of State to make provision setting out a process for how domestic support should be classified, and a process for the resolution of disputes regarding the classification of domestic support, "which may include provision making the Secretary of State the final arbiter on any decision on classification." Under this clause, regulations may be made requiring a devolved authority to provide information to the Secretary of State for the purpose of carrying out the functions referred to above.

6.7 Part 7 - Wales and Northern Ireland

Clauses 43-45 make provision for Wales and Northern Ireland.

Clause 43 makes provision for Wales in Schedule 5. As in the 2017-2019 Agriculture Bill, these powers have been included at the request of the Welsh Government, but in the 2019-2020 Bill Welsh Government opted not to take powers to allow Wales to transition to new schemes. Lesley Griffiths, Welsh Government Minister for Environment, Energy and Rural Affairs stated on 16 January 2020 that the powers are:

intended to be temporary until an Agriculture (Wales) Bill is brought forward to design a ‘Made in Wales’ system which works for Welsh agriculture, rural industries and our communities. [...]

The Bill introduced on 16 January, provides powers for the Welsh Ministers to continue paying Direct Payments to farmers beyond 2020 and gives our farmers much needed stability during this period of uncertainty. It also contains certain other powers, including those which are important to ensure the effective operation of the internal market in the UK.

Given the passage of time since the original Bill was first introduced in September 2018, I have reflected on the scope of the Welsh schedule, taking into account the helpful reports provided by the Senedd during scrutiny. I have concluded it is no longer appropriate to take powers to allow the Welsh Ministers to operate or transition to new schemes. My intention now is these will be provided for instead by the Agriculture (Wales) Bill. I intend to publish a White Paper towards the end of 2020 which will set out the context for the future of Welsh farming and pave the way for an Agriculture (Wales) Bill.

Griffiths, L. (2020, January 16). Written Statement: UK Agriculture Bill. Retrieved from https://gov.wales/written-statement-uk-agriculture-bill [accessed 28 January 2020]

As such, Schedule 5 extends similar powers to Welsh Ministers as those conferred on the Secretary of State in Parts 1-3 and 5 of the Bill.2 This includes provision for financial support after exiting the EU, intervention in agricultural markets, collection and sharing of data, marketing standards and carcass classification, and data protection.

Clause 45 makes provision in relation to Northern Ireland in Schedule 6, and extends similar powers to the Northern Ireland Department for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) as those conferred on the Secretary of State in part 1 chapter 2, part 2 chapter 2, part 3 chapter 2 and part 5 of the Bill.2 This includes provision for financial support after EU exit, intervention in agricultural markets, collection and sharing of data, marketing standards and carcass classification, and data protection. However, the powers extended to DAERA are more extensive than those extended to Welsh Ministers, given Welsh Ministers' intention to introduce separate Welsh legislation, as noted above.

6.8 Part 8 - General and Final Provisions

Part 8 includes general and final provision, including on data protection (Clause 46), rules for making regulations (Clause 47), clarifying interpretation of different terms (Clause 48), and consequential amendments (Clause 49).

Clause 50 confers power on"the appropriate authority" to make supplementary, incidental or consequential provision, by regulation. Scottish Ministers are not included as an appropriate authority, as Scotland has not opted to take powers via the Bill.

Clause 51 makes provision for money provided by Parliament to be paid to operate schemes and financial assistance programmes provided for under the Bill, and related administrative expenditure.

Clause 52 sets out the extent of the clauses in the Bill.

The Bill extends to Scotland in Clauses 27-30 (fair dealing with agricultural producers and producer organisations), Clause 39 (Power to reproduce modifications under Section 35 for wine sector), Clauses 40-42 (WTO Agreement on Agriculture), Clauses 47-48 (Regulations and interpretation), Clauses 50-54 (final provisions), Schedule 1 (Agricultural sectors relevant to producer organisation provisions), Schedule 2 (competition exclusions). The UK Government is not seeking Scottish Government consent for these clauses.

The Bill also extends to Scotland for Clause 17 (Food Security), Clauses 31-32 (Fertilisers and identification and traceability of animals), Clause 33 (Red Meat Levy), Clauses 36-37 (organic products). The UK Government is seeking Scottish Government consent for these clauses.

Unlike Wales and Northern Ireland, Scotland has chosen not to take powers via the UK Agriculture Bill.

The extent of the Bill is explored further below.

6.9 Schedules

Schedule 1 sets out the agricultural sectors relevant to provisions for producer organisations. Schedule 1 is intended to apply to Scotland.

Schedule 2 sets out competition exclusions for recognised producer organisations, amending the Competition Act 1998. Schedule 2 is intended to apply to Scotland.

Schedule 3 sets out rules for agricultural tenancies in England.

Schedule 4 sets out agricultural products relevant to provisions on marketing standards. This schedule applies to England.

Schedules 5 and 6, as noted above, make provision for Wales and Northern Ireland

Schedule 7 makes provision for amendments to the Common Organisation of Markets Regulation, including for exceptional market conditions in England and Wales, Marketing Standards and Carcass Classifications in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

7. Issues raised in the House of Commons

The Bill passed its second reading in the House of Commons on 3 February 2020, and passed the committee stage on the 5 March 2020. As of publication of this briefing, the Bill was at the report stage. No date for Report stage has yet been set.

Second Reading

The most frequently raised issue was the lack of firm duty on trade and standards, to ensure that imported agricultural products meet the same environmental, food safety and animal welfare standards as those produced in the UK. As discussed more below, a major criticism of the bill from stakeholders, opposition and backbench MPs alike has been that without this commitment, trade deals which allow goods produced to lower standards to be imported into the UK may undercut UK production.

In addition, issues raised at second reading included:

Governance:

the need for inter-governmental structures to establish and maintain common frameworks for agriculture;

the perceived lack of adherence to the devolved settlement. Scottish MPs raised that they felt the Bill was straying into areas of devolved competence;

the need for new measures of success for agriculture beyond yield;

the lack of provision for farm advice in the Bill, to support farmers to make the transition;

a lack of vision to protect rural communities;

a lack of provision to protect agricultural workers;

Environment:

the need to maintain food production abroad so not to risk offshoring the UK's environmental impact;

disappointment that the Bill is not clearer about financially rewarding a transition to 'agroecology', or a whole-farm approach to agriculture with the environment at its core;

the need to enshrine baseline environmental standards that all farmers should adhere to, whether in receipt of funding or not, and the lack of provision for this in the Bill;

that the Bill is not ambitious enough about climate change or the environment by banning the most damaging practices and taking on board best-practice recommendations from e.g. the Environmental Audit Committee's Soil Health Inquiry;

while there are powers conferred on the Secretary of State, MPs raised the the overall lack of duties on the Secretary of State to e.g. safeguard the environment;

lack of incorporation of the UK Committee on Climate Change's advice for reaching net-zero;

Food:

lack of consideration in the Bill for the whole food system, including:

food prices and food poverty;

healthy food

food sustainability

that only reporting on food security every five years is inadequate; many MPs felt that the UK Government should report every year to begin with;

Funding:

the need to consider currency fluctuation, and whether support to farmers will take this into account;

questions around what the multi-annual framework for farm support is and when the details will be worked out;

whether support for farmers will keep pace with the support received by farmers in other countries;

when details of the Shared Prosperity Fund would be made available;

Additional questions on trade and standards:

the lack of protections on food quality and protected geographical indicators;

concerns about potential tariffs between Northern Ireland and the British mainland;

the impact of trade deals on the support offered within the Bill.

Committee Stage

A number of amendments were proposed at the committee stage. Most of the amendments suggesting substantive changes were rejected after a vote, including an amendment addressing the issue of imports, as discussed during the second reading.

The proposed amendment read:

“Import of agricultural goods

(1) Agricultural goods may be imported into the UK only if the standards to which those goods were produced were as high as, or higher than, standards which at the time of import applied under UK law relating to—

(a) animal welfare,

(b) protection of the environment, and

(c) food safety.

(2) “Agricultural goods”, for the purposes of this section, means—

(a) any livestock within the meaning of section 1(5),

(b) any plants or seeds, within the meaning of section 22(6),

(c) any product derived from livestock, plants or seeds.”

The full list of amendments and their status can be found here: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/58-01/0007/amend/agriculture_rp_pbc_0305.pdf

8. Parts that apply in Scotland

As noted above, much of the Bill only applies in England. The Bill contains 54 clauses and 7 schedules. 16 of the substantive clauses (i.e. not including the final provisions of an administrative nature which apply in all Bills) Bill extend and apply to Scotland.

Those clauses are:

Clause 17 (food security);

Clauses 27-30 (Fair Dealing with Agricultural Producers and Producer Organisations); and the schedules introduced by these clauses (Schedule 1 (Agricultural sectors relevant to Producer Organisation provisions);

Schedule 2 (Competition Exclusions).

Clauses 31-32 (Fertilisers and Identification and Traceability of Animals);

Clauses 36 – 37 (Organic Products);

Clause 39 (Power to reproduce modifications under section 35 for wine sector);

Clauses 40-42 (WTO Agreement on Agriculture)

The substantive clauses which apply in Scotland are explored below.

8.1 Food Security

Clause 17 places a duty on the Secretary of State to report on food security to the UK Parliament at least once every five years. They must report the whole of the UK, and provide "an analysis of statistical data related to food security". The data analysed in the report may include data on:

global food availability

supply sources for food

resilience of the supply chain for food

household expenditure on food

food safety and consumer confidence in food.

As noted in the Explanatory Notes, these metrics are taken from the 2010 UK Food Security Assessment.

The UK cross-government programme on food security research define food security as:

when all people are able to access enough safe and nutritious food to meet their requirements for a healthy life, in ways the planet can sustain into the future.1

The introduction of this clause on food security, as well as a duty on the Secretary of State to "have regard to the need to encourage the production of food by producers in England and its production by them in an environmentally sustainable way" when framing any new financial assistance scheme,2 is new for this version of the Bill. Environment Secretary Theresa Villiers said of the Bill as a whole that it "enabl[es] a balance between food production and the environment which will safeguard our countryside and farming communities for the future"3. This signals a slight shift in focus from the 2017-2019 Bill, which received criticism from the National Farmers Union (NFU) that it did not place enough emphasis on food production. NFU President Minette Batters said of the food security provisions in the Bill:

This is something the NFU has been calling for consistently for many years and will be even more important as we enter the uncertain period ahead with domestic policy change and the likelihood of increase liberalisation of the UK food market through trade deals with new international partners post Brexit.

At the Oxford Farming Conference, Theresa Villiers stated:

And there will be new provisions to require the Government to conduct a regular review of food security.

Planning for a possible no-deal outcome including a focus on potential disruption at Dover has provided a timely reminder of the huge importance of domestic food production.

I firmly believe that society’s approach to farming, if guided by simplistic economics, hugely under-estimates its significance in so many ways, its importance for the wider rural economy, for environmental stewardship, for keeping the cost of living down, and for feeding the nation.

In an uncertain world, food security is an issue that we must take very seriously and this is a point I will always emphasise around the Cabinet table.4

According to the Explanatory Notes to the Bill, the "report [on food security] will take a broad understanding of what food security is".5

Greener UK, an alliance of major environmental NGOs broadly support the inclusion of the provision, but stressed the need for a comprehensive assessment:

The new provision in the bill to assess food security every five years will provide MPs with the information they need to hold the government to account. It is crucial though that this assessment includes a consideration of the sustainability of food consumed in the UK, whether produced at home or overseas. This is not specified in the bill, despite it being part of the last such assessment in 2010.6

Food Policy in Scotland

The UK Government is seeking consent from the Scottish Parliament for this clause to apply to Scotland, and therefore report on food security in relation to Scotland.

The Scottish Government is currently looking at legislating on food, and have committed to introducing a Good Food Nation Bill this year. The Scottish Government held a consultation on proposals for legislation between December 2018 and April 2019, which included proposals for the Scottish Government to prepare their own statements of food policy and have regard to them in the exercise of their functions. The analysis of consultation responses showed support for such statements, and noted that:

A key perspective was of a need for a holistic or whole system approach, involving all sectors and relevant groups working together so that policies relate to all parts of the food system.

...A significant number of organisations noted the need to avoid policy conflict and dovetail with other policies or initiatives such as climate change goals, human rights legislation, transport policies and so on.

As such, the Scottish Government may have the opportunity to consider security of supply and access to food as part of its wider food policy.

8.2 Fair Dealing Obligations

The Explanatory Notes to the Bill state:

Primary agricultural producers in the UK tend to be small, individual businesses operating without strong links between them. By contrast, operators further up the supply chain - processors, distributors and retailers - tend to be highly consolidated businesses that command substantial shares of the relevant market. This disparity makes primary producers vulnerable to unfair trading practices. It often forces them into contractual relationships which impose on them commercially harmful terms, but to which they have no commercial alternative and in respect of which there is no legal protection1

Consequently, this clause enables the Secretary of State to make regulations that establish fair contractual relationships between primary producers and "business purchasers".

Under the Bill this clause applies to Scotland, but the UK Government does not intend to seek legislative consent. This position is the same as it was during the passage of the 2017-2019 Bill.

The SPICe briefing on the 2017-2019 Bill noted:

Regulation of unfair contract terms is a matter of Scots private law, and is therefore devolved.

However, “the regulation of anti-competitive practices and agreements” is reserved. In the Explanatory Notes the UK Government suggest that this clause pursues a similar aim to that of the Groceries Supply Code of Practice, which promotes fair dealing between supermarkets and their suppliers. The Code applies on a UK basis, and is enforced by a UK adjudicator. The Code was concerned with anti-competitive practices in the UK groceries sector, and the market dominance of the 10 largest supermarkets.

A debate relates to whether clause 25 is directed at unfair contractual terms, which is a devolved matter, or anti-competitive agreements and practices, which is reserved2

In the Explanatory Notes for the amendments put forward by Scottish Government for the 2017-2019 Bill, the Scottish Government stated:

In the Scottish Government’s view, this involves matters in a devolved policy area, namely the regulation of unfair contractual terms in commercial contracts by agricultural producers in Scotland. Therefore, in line with the devolution settlement, where such regulations extend to Scotland, these should only be made with the consent of the Scottish Ministers.3

8.3 Producer Organisations

A Producer Organisation (“PO”) is an organisation formed by a group of farmers that carries a status under EU law. Through the PO, the farmers coordinate their activities to increase their competitiveness. POs benefit from a number of exemptions from competition law which enable their members to collaborate in ways which would otherwise breach competition law (such as, joint production planning and processing, collective negotiations). There is therefore a connection between the PO regime and competition law.

Clauses 28-30

set out the conditions that organisations of producers must meet to be recognised as a PO under a new domestic regime. As the Explanatory Notes state, "these have been kept broadly consistent with the substance of the existing regime, and the Bill includes powers for the Secretary of State to specify the details of these conditions".1

establish the exemptions from competition law that are available to recognised producer organisations, by amending the Competition Act 1998.

The Bill applies these clauses in Scotland, but the UK Government is not seeking legislative consent. As with fair dealing obligations, this was a point of debate during the passage of the 2017-2019 UK Agriculture Bill.

The SPICe briefing on the 2017-2019 Bill noted:

The Sewel Convention will apply if these serve a devolved purpose. Agricultural policy is a matter which falls within devolved competence. Producer organisations (POs) help to strengthen the position of producers in the food chain and contribute to a healthy and competitive agricultural market. It is therefore possible to argue that legislating in relation to POs serves a devolved purpose.

However, in order operate as intended, POs need to be exempt from certain competition law requirements. “Competition” is a reserved matter under Schedule 5, Head C (Trade and Industry) of the Scotland Act 1998. The reservation covers “regulation of anticompetitive practices and agreements: abuse of dominant position; monopolies and merger.” The reservation was designed to ensure the continuation of a common United Kingdom system for the regulation of competition matters. Competition matters are currently regulated by the Competition Act 1998 which introduced a prohibition approach to anti-competitive agreements and abuse of a dominant position.

Due to the interaction between POs and competition law, the debate surrounds whether the purpose of this clause is the promotion of an effective agricultural market (which is devolved) or the regulation of anti-competitive practices (which is reserved).2

In the Explanatory Notes for the amendments put forward by Scottish Government for the 2017-2019 Bill, the Scottish Government state:

In the Scottish Government’s view, this relates to matters in a devolved policy area, namely the promotion of an effective agricultural market to replace the EU producer organisation regime and therefore, in line with the devolution settlement, decisions on such applications in relation to Scotland should be taken by the Scottish Ministers.3

8.4 Fertilisers

The provisions on fertilisers are new for the 2019-2020 Agriculture Bill. As noted in the Explanatory Notes to the Bill, Clause 31 "enables the regulation of fertilisers based on function. This will allow different requirements to be set, for example, for biostimulants, soil improvers and traditional mineral fertilisers to ensure the safety and quality of the various types of products marketed as a fertiliser in the UK."1 In addition, Clause 31(4) "allows for regulations to set out an assessment, monitoring and enforcement regime for ensuring the compliance of fertilisers with composition, content and function requirements and for mitigating other risks to human, animal or plant health or the environment presented by fertilisers." 1

The assessment of fertilisers is currently regulated at an EU level. However, there are a range of other regulations that apply in relation to the environment, health and safety, chemical use, planning and more. Some of these additional regulations are domestic and some also come from the EU. The Agricultural Industries Confederation provide a useful summary of the regulations that apply, here.

This clause specifically mentions the assessment of fertilisers, but in subsection 4, which makes provision for a section to be inserted into in the Agriculture Act 1970, power is given to make regulations to amend or repeal EU Regulation 2003/2003 of 13 October 2003 relating to fertilisers, or "amending or repealing other retained direct EU legislation".

The regulation of fertilisers is important to ensure their safe manufacture and use, and to limit their impact on the environment. Approximately 150 kilotonnes (kt) of nitrogen from mineral fertilisers and 147kt of nitrogen from animal manure are added to Scottish soils every year; yet, the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology estimates that 132kt of nitrogen is lost from Scottish soils and goes directly into water bodies, and 19kt of nitrogen is released directly from Scottish soils into the atmosphere, and more is released indirectly3. Nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas; around 80% of Scotland's nitrous oxide emissions come from agriculture.4

The UK Government is seeking the legislative consent of the Scottish Parliament to extend this clause to Scotland because it falls within devolved competence. The power to make regulations under section 74A is exercisable (insofar as within devolved competence) only by the Scottish Ministers, having been transferred to the Scottish Ministers by virtue of section 53 of the Scotland Act 1998.

8.5 Identification and Traceability of Animals

Provisions for the identification and traceability of animals are new for the 2020 UK Agriculture Bill. As detailed above, Clause 32 makes provision for a UK-wide system for tracing and identifying animals. Identifying and tracing animals helps to ensure a high standard of food safety and animal welfare, for example, allowing authorities to track livestock disease. These provisions would allow the Secretary of State to establish a board to oversee livestock information. The House of Commons Library Briefing on the Agriculture Bill notes:

The Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB) is leading on the development of a new multi-species livestock information, identification and tracking service. This will be known as the Livestock Information System (LIS) and its programme vision states:

'Working in partnership, Defra and industry will develop worldleading standards of livestock traceability in the UK. This will deliver a competitive trade advantage, make us more resilient and responsive to animal disease and will drive innovation, interoperability and productivity improvements throughout the meat and livestock sectors.'

The AHDB has said that the LIS is expected to be delivered “by late 2020”.1

The Explanatory Notes state that "The purpose of the clause is to prepare for the introduction of a new digital and multi-species traceability service, the Livestock Information Service (LIS), based on a database of animal identification, health and movement data."2 The Explanatory Notes also clarify that the LIS will be managed by AHDB.

Scotland currently has its own system of livestock traceability - ScotEID - managed by the Scottish Agricultural Organisation Society (SAOS). Its website states:

ScotEID is the livestock traceability system for Scotland. On behalf of the Scottish Government and the Scottish livestock industry, SAOS continues to manage research and development of livestock movement data systems through supply chains, including the development of cattle electronic identification (EID). Our work on livestock traceability continues to advance towards the conclusion of an all species data system, working in real time. In preparation for the demise of the GB-wide cattle tracing system (CTS), work is in hand to extend ScotEID’s coverage to cattle births, deaths and farm business to farm business moves.3

ScotEID and LIS are complementary systems, but it is not clear how the powers in the UK and Scottish Bills will relate to one another. The National Farmers Union for Scotland (NFUS) noted in their March 2020 edition of Scottish Farming Leader that livestock traceability is one of the areas in which UK and Scottish approaches must be coordinated:

Going forward, it is essential that powers are not overlapping. What is needed are different powers, rather than parallel powers, to enable (where appropriate) differentiated approaches across the UK that are also sufficiently co-ordinated to handle the likes of cross-border movements of livestock. If not, then Scotland's ambitions for a multi-species database under the ScotEID could theoretically be undermined.4

The UK Government intends to seek the legislative consent of the Scottish Parliament to these provisions because they are within devolved competence. New section 89A of the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006 (“2006 Act”) (as inserted by clause 32) will allow the Secretary of State to assign to a body established under the 2006 Act, functions related to collecting managing and sharing certain information. The power to establish a body is exercisable by the Secretary of State alone, however, the body so established will be able to exercise functions in relation to Scotland.

8.6 Red Meat Levy

As noted above, Clause 33 on the Red Meat Levy makes provision for the creation of a scheme for levy monies collected at slaughterhouses to be redistributed between the UK levy bodies. In Scotland, the levy body is Quality Meat Scotland (QMS). The UK Government is seeking consent from the Scottish Government for this clause, and the clause specifies that any scheme for redistributing the red meat levy "is to be made jointly by" the Secretary of State, Scottish Ministers, and Welsh Ministers, if it involves the levy body in the respective territory.

This clause resolves long-held concerns by Scotland and Wales that the current system of collecting levies is unfair. The levy is collected at the slaughterhouse, regardless of where an animal was reared and may have spent most of its life. Therefore, as the Explanatory Note states,