Issue 2: EU-UK future relationship negotiations - March 2020

Following the UK's departure from the EU, the negotiations to determine the future relationship began on 2 March 2020. Over the course of the negotiations, SPICe will publish briefings outlining the key events, speeches and documents published. This second briefing covers the first week of negotiations and developments in the Scottish Parliament.

Executive Summary

This briefing is the second in a series of SPICe briefings that will be published regularly during the negotiations on the future relationship between the EU and the UK.

This briefing covers the first round of negotiations on the future relationship in Brussels. It provides an updated timeline for the negotiations and analyses the initial areas the UK and EU have identified as disagreements. The briefing also reports on the position of the Scottish Government in relation to the UK's negotiating approach.

| Image source: EC - Audiovisual Service, © European Union, 2020 |

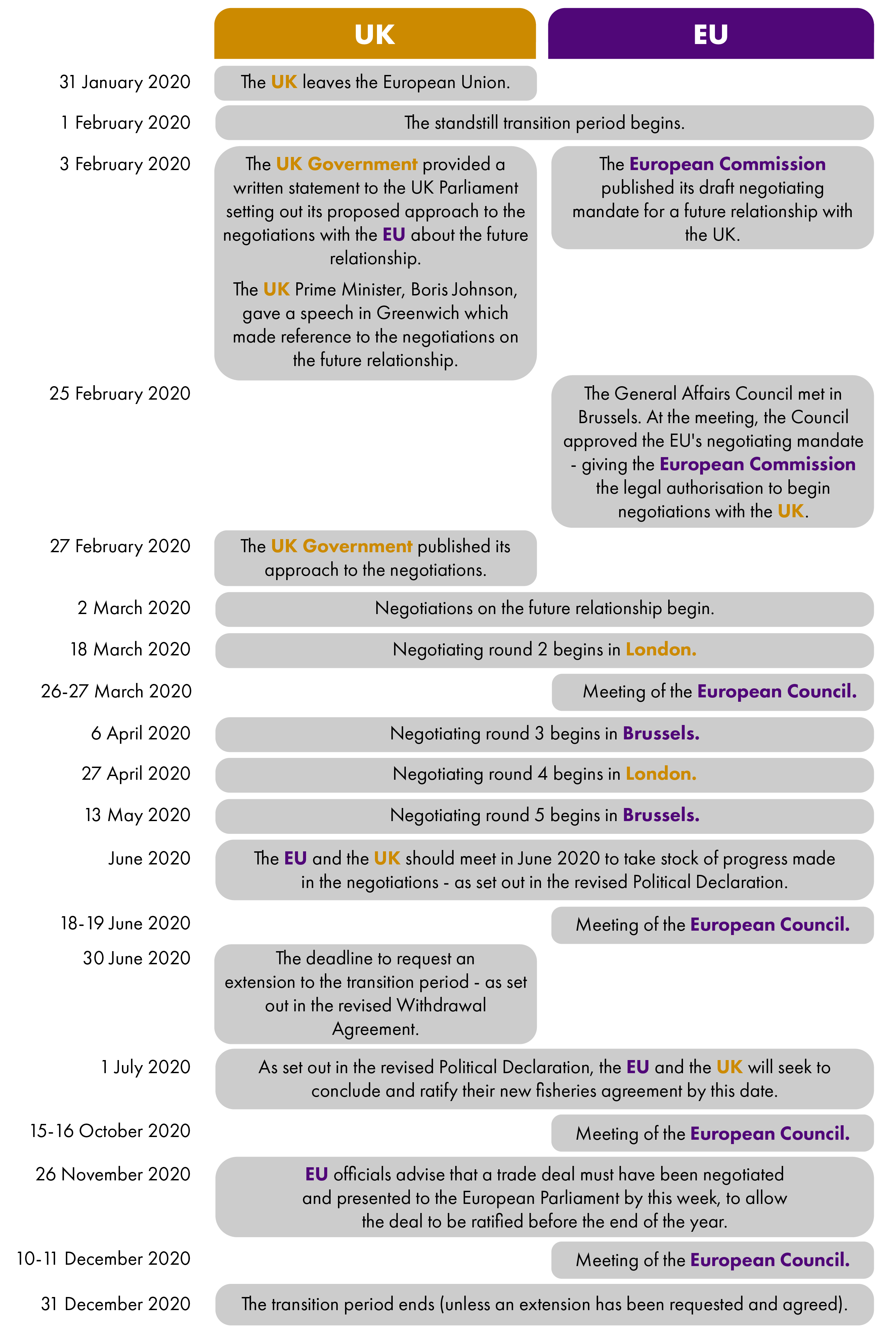

Timeline of negotiations

The negotiations begin

Both the UK and EU have published their approaches to the UK-EU future relationship negotiations. These documents were analysed by SPICe in Issue 1 and key issues discussed ahead of negotiations.

The first round of negotiation took place on 2-5 March 2020 in Brussels.

Following a bilateral meeting of the Lead Negotiators and an opening plenary, specific discussions were held on:

Trade in goods

Trade in services and investment and other issues

Level playing field for open and fair competition

Transport

Energy and civil nuclear cooperation

Fisheries

Mobility and social security coordination

Law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters

Thematic cooperation

Participation in Union programmes

Horizontal arrangements and governance

Foreign policy and defence were not discussed in line with the UK's position.

Report from Michel Barnier

European Commission Chief Negotiator Michel Barnier provided a press statement at the close of the first round.

In this statement, given largely in French, he described the start of the talks as "serious and constructive" and identified three key priorities from the EU's point of view. These were:

To ensure the proper application of the withdrawal agreement. On the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol, Barnier said "this is not a time for negotiation. It is about implementing a specific agreement in a pragmatic and operational way."

Preparing for changes that will take place in all cases - whether there is agreement or not on 1 January 2021.

To rebuild a partnership with the United Kingdom.

Outlining the EU's approach to the third task, Barnier said:

We will make every effort to build the foundation for our future partnership, in line with the Political Declaration agreed with Boris Johnson in October 2019.

In line with this statement, the EU's negotiating mandate closely follows the Political Declaration.

Barnier highlighted four areas of disagreement following the first round.

Level playing field - in particular whether commitments to prevent trade distortions, unfair competitive advantages and high labour and environmental standards should be in a joint agreement and subject to a joint compliance mechanism.

Judicial and police cooperation in criminal matters - in particular how the UK continues to apply the European Convention on Human Rights and what role the European Court of Justice will play in this will influence the level of future cooperation.

Governance of any future agreement, and the horizontal provisions - including whether to negotiate a suit of agreements as the UK proposes or one "global" agreement with joint governance arrangements.

Fishing - in particular whether access to UK fisheries is negotiated on an annual basis or a status similar to the status quo is retained.

Disagreements in these areas had been anticipated ahead of the talks.

Two specific examples of agreement were mentioned: cooperation on civil nuclear power and the participation of the United Kingdom in certain Union programs (e.g. funding programmes such as Horizon Europe and Erasmus+).

Report from UK Government

Following the end of round 1 the Number 10 media blog issued a press statement:

We have just concluded the first round of negotiations, and we are pleased with the constructive tone from both sides that has characterised these talks. This round was a chance for both sides to set out their positions and views.

Following detailed discussions we now have a good idea where both parties are coming from. These are going to be tough negotiations - this is just the first round. In some areas there seems to be a degree of common understanding of how to take the talks forward. In other areas, such as fishing, governance, criminal justice and the so-called ‘level playing field’ issues there are, as expected, significant differences.

The UK team made clear that, on 1 January 2021, we would regain our legal and economic independence – and that the future relationship must reflect that fact. We look forward to continuing these talks in the same constructive spirit when the parties meet again in London on 18 March."

The key areas of difference listed by the UK Government in this statement match those reported by Michel Barnier.

UK to publish legal texts

On 9 March, the UK Government published a written statement to the UK Parliament which reflected the same issues as the Number 10 media blog statement. In addition, the written statement announced the UK Government's intention to publish legal texts ahead of round 2:

The next negotiating round will take place on 18-20 March in London. The UK expects to table a number of legal texts, including a draft FTA, beforehand.

Analysis of round one

It is difficult to conclude anything concrete from the initial round. The four areas of disagreement mentioned by the EU and UK sides were known beforehand.

In contrast to some of the previous negotiations on the withdrawal agreement, it appears that both sides have articulated what outcomes they want. This has presumably allowed for areas of agreement and disagreement to be readily identified in more detail. Future rounds can be expected to address the areas of disagreement.

The level playing field disagreement appears to be centred on State Aid where the EU's desire for the UK to be in "dynamic alignment" with EU rules as they evolve is rejected by the UK. The other aspects of any level playing field - for example labour standards, environment standards, aspects of tax - the two sides' positions appear to be more compatible and agreement may be possible based on "non-regression". If the State Aid disagreement is to be resolved the solution may lie somewhere between regulatory alignment and non-regression; the question is whether this is acceptable to the EU.

On judicial and police cooperation in criminal matters, disagreement appears to be centred on the role of the European Court of Justice. Greater levels of cooperation would presumably lead to a requirement for some areas of shared or equivalency in law and the EU's position is that the ECJ is the sole arbiter of Union law. This question is also core to agreement on any dispute resolution mechanism where the UK's position is that "there will be no role" for the ECJ.

The EU's desire as set out by Michel Barnier is for a "global" agreement with shared governance, while the UK prefers a suite of deals. In the negotiations on withdrawal, the EU's position was that "nothing is agreed until everything is agreed". This position may be harder for the EU to maintain in the future relationship negotiations and, as Professor Ben Leruth writing for The UK in a Changing Europe points out, a suite of agreements would not represent an in principle departure from the Political Declaration.

Fisheries is a politically charged subject for both parties where disagreement is clear. The EU hardened its position on access to UK waters when it signed off the European Commission's negotiating mandate. As Professor Ben Leruth writes, this issue may well be an important influence on any final deal:

The UK does not want fisheries to be included in the free trade agreement... and requests to hold annual negotiations on reciprocal access to European and British waters.

...This is likely to be a tricky matter, and it would not be the first time such talks reach a dead end: in 2010, when Iceland started accession talks with the EU (before the Icelandic government eventually decided to withdraw its application in 2015), it appeared clear that no agreement would be found on fisheries.

If no agreement on the matter can be found between the EU and the UK, the whole deal could collapse – it is that serious.

Joint statement from Devolved Administrations

Following a meeting of ministers from the Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish governments on 10 March, the Devolved Administrations published a joint statement. This statement called for greater influence over the UK’s negotiating position ahead of round 2:

Before the next round of negotiations later this month we agreed there must be a meaningful, comprehensive and transparent process for the Devolved Governments to influence the UK’s negotiating position – something that has clearly not happened so far.

These negotiations will have significant and long-lasting impacts on people, communities and businesses, and the Devolved Governments have a particular responsibility for ensuring the interests of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are protected and promoted.

Each of our Governments have particular concerns and these must be taken seriously with the opportunity to directly influence the negotiating position. “With the next round of negotiations just eight days away, there is an urgent need for meaningful and constructive engagement by the UK Government at all levels on this issue - with proper opportunities to help decide the UK’s position in the most significant negotiations in decades.

This is the first joint statement from the Devolved Administrations on Brexit to include the Northern Irish Executive, following its re-establishment in January 2020.

Future rounds

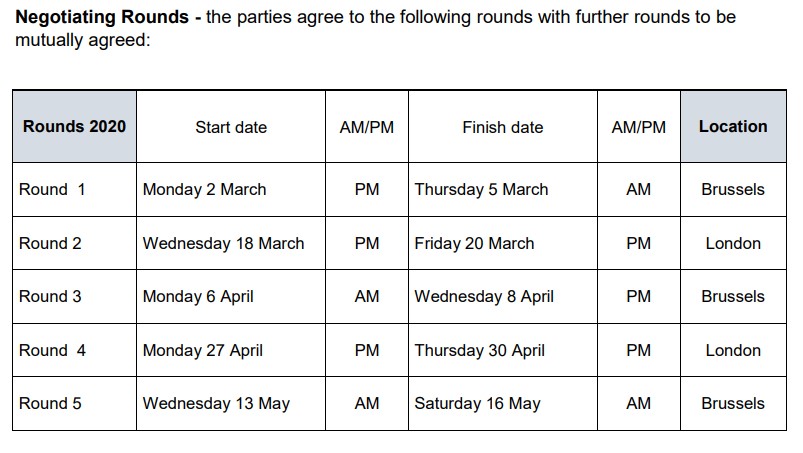

The second round of negotiations will take place 18-20 March 2020 in London with dates for three more rounds agreed in the negotiations' terms of reference.

Cabinet Secretary statement on the UK's negotiating approach

On 4 March, the Cabinet Secretary for the Constitution, Europe and External Affairs, Michael Russell provided a statement to the Scottish Parliament on the UK's approach to negotiations with the European Union.

On the role of the Devolved Administrations and Scottish Parliament, the Cabinet Secretary stated:

The devolved Governments are, once again, being managed, not engaged.The joint ministerial committee on European Union negotiations last met on Tuesday 28 January, in Cardiff. At the conclusion, the three devolved Governments made it clear that they needed to see the legal texts and working papers that were part of the process of producing the negotiating mandate. That did not happen. The JMC has not been convened since then.

Consequently, we have not agreed the way in which the devolved Governments will be involved in the second-stage negotiations. Nor have we agreed how we would reach a common mind on any issue to be negotiated, although there is a proposal from me on the table of a three-room structure. Not only has the final mandate now been published, the negotiations have started. Not only is that contrary to the terms of reference of the JMC(EN), it is contrary to the devolution settlement, because it is devolved issues such as agriculture, environment and fisheries that will be at the heart of the negotiations.As the legally and politically responsible body, this Parliament and this Government must be involved in deciding what stance to take.

...We reject the published mandate as it is, we will make it clear that if the UK Government attempts to speak on matters of devolved competence, it does not speak for us, and we will ask the Scottish Parliament not to agree actions or agreements if they have not been discussed with us.

The Cabinet Secretary covered legislative proposals to "keep pace" with EU regulations:

We will also shortly introduce the continuity bill, which will give the Parliament and our Government powers to keep pace with European regulation, and we will do so confident in our right to take those actions in areas that are devolved. The extent to which devolved law aligns itself with the law of the EU is a decision for the Scottish Parliament to take, not the UK Government. We will, of course, always be willing to discuss the negotiating position on devolved matters, if that discussion is meaningful and respects the devolved settlement.

These are proposals are expected to provide powers similar to the "keeping pace" powers provided for in the Section 13 of the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Legal Continuity) (Scotland) Bill. This Bill was not progressed following a ruling of the Supreme Court.

The Cabinet Secretary's statement also covered participation in the EU's competitive funding programmes. Participation in these programmes is an area of the negotiations where the Devolved Administrations and UK Government appeared to be in agreement. However the Cabinet Secretary's statement indicated that disagreement did exist on the detail and that the possibility of Scotland participating in EU programmes without the UK Government's involvement had been raised:

The UK Government is also lukewarm about the UK’s participation in EU programmes such as Erasmus+ and Horizon 2020, and it has actively abandoned involvement in other cross-border programmes such as Creative Europe. We are told by the UK that devolved Governments will not be allowed to take up individual membership of any European programme if the UK does not join as a third party.

SPICe has published a Spotlight blog discussing how the devolved administrations can influence the future relationship negotiations. It concludes:

Given the difficulties present in the current operation of intergovernmental machinery, it will be challenging for the devolved administrations to effectively influence the UK government’s negotiating position to reflect the stated interests of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. However, by working together, and working with other interested stakeholders the devolved administrations can ensure that the UK government is made aware of the negotiating priorities identified by the devolved governments in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

https://spice-spotlight.scot/2020/03/03/how-can-the-devolved-administrations-influence-the-future-relationship-negotiations/

Secretary of State for Scotland's evidence to the European Committee

On 5 March, the UK Government's Secretary for State for Scotland, Alistair Jack MP attended the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee.

In his opening statement the Secretary for State referred to the role of Devolved Administrations in negotiating the future relationship:

We left the EU as one United Kingdom, and we are now free to determine our own future and form relationships with old allies and new friends around the world. The UK Government will negotiate those relationships on behalf of the United Kingdom, but we are clear that the devolved Administrations should be closely involved in the process, both at ministerial level—for example, via the joint ministerial committee (European Union negotiations)—and via on-going and constructive engagement between officials.

These mechanisms (the Joint Ministerial Committee, engagement between officials) are existing practice. These mechanisms have been subject to criticism from the Scottish and Welsh governments. This criticism has been summarised by Institute for Government in its explainer on the Joint Ministerial Committee.

The Secretary of State emphasised that the UK Government was seeking a deal based on precedent. However, it is worth noting that the EU has argued that the EU and the UK's "geographic proximity and economic interdependence" requires level playing field provisions that go further than the precedent of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA).

The Secretary of State also referred to the scenario where no free trade agreement is agreed:

We are not asking for a special, bespoke or unique deal; we want a comprehensive free trade agreement similar to Canada’s. In the very unlikely event that we do not succeed in achieving that, our trade will be based on our existing withdrawal agreement deal with the EU. The choice is therefore not a deal or no deal, in that respect.

The Secretary of State claimed that "trade will be based on our existing withdrawal agreement". However, the withdrawal agreement does not include any provisions for the trade (in goods or services) between the Britain and the EU after the end of the transition period in 2020.

Questioning from MSPs then covered topics including:

Whether the UK Government will publish an economic impact assessment of the trade deal described in its Command Paper

Scotland-specific interests in future migration policy

The level playing field provisions in CETA

The nature of checks on goods moving between Great Britain and Northern Ireland

Fisheries

Travel connections between Scotland and Northern Ireland

The UK's participation in Erasmus+

Comparison of UK and EU approaches by House of Lords EU Committee

On 5 March, the House of Lords European Union Committee published a report which:

analyses the European Union's approach to the future relationship negotiations, as set out in a European Council Decision.

compares the EU's approach to the UK Government's approach, as set out in a Written Statement published on 3 February 2020, and a Command Paper published on 27 February 2020.

reviews both approaches against the Political Declaration on the framework for future UK-EU relations, which was agreed by both sides in October 2019.

The report summary states:

Our analysis underlines the extent to which two sides have diverged since last October’s agreement. While this may to an extent reflect the adoption by both sides of opening negotiating positions, the scale of the challenge ahead, if agreement is to be reached before the end of 2020, is clear.

On the European Union's approach as defined by the Council Decision, the report states:

One of the most striking features of the Decision is its resemblance to the Political Declaration... Its negotiating directives adopt the same structure as the PD, using the same headings and sub-headings, and much of the text is copied and pasted verbatim. The Commission has of course elaborated the EU’s position in many areas, changing the emphasis, and prioritising the EU’s interests. There are also some omissions, which we highlight in Chapter 3, but taken as a whole the Decision is a development of, rather than a departure from, the PD.

On the UK Government's approach, the report states:

[The UK] Government’s WMS and Command Paper, setting out its negotiating objectives, are in structure and in some content markedly different from the PD. The headings (in particular, the division into ‘chapters’), rather than following the PD, appear to be based on those used in existing Free Trade Agreements, such as the EU-Canada and EU-Japan agreements. As a result, significant elements of the PD are omitted, including sections on overarching principles, on fundamental rights, and on potential cooperation in the international sphere.

Chapter 3 of the report compared the EU and UK approaches on specific issues. Some of those issues relevant to devolved matters include:

Economic partnership

Public procurement

Transport

Fisheries

Level playing field and sustainability

Internal security

On the level playing field, the Committee's conclusions were that agreement on competition policy, the environment, labour standards and taxation could be reached within the existing positions of the UK and the EU. However, the positions on State Aid are "essentially incompatible".

Although the UK and the EU agreed in the Political Declaration to “robust commitments to ensure a level playing field”, the precise nature of those commitments was not defined. The Council Decision adds considerably more detail, and while it calls for non-regression in several areas, it demands continuing alignment with EU rules only in respect of State aid.

The Government’s acceptance that the two sides should make “reciprocal commitments” to maintaining high standards in competition policy, the environment, labour standards and taxation, leaves open the possibility that the two sides could reach agreement in these areas. But the UK and EU positions on State aid are essentially incompatible, and have recently hardened.

Whether a binding commitment to "non regression" in the area of State Aid by the UK, as opposed to dynamic alignment with EU rules, will be sufficient for the EU will be worth watching. This topic is discussed in more detail in Issue 1.

Minister for the Cabinet Office at Future Relationship Committee

On 11 March, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office, Michael Gove appeared before the UK Parliament's Future Relationship with the European Union (FREU) Committee.

The FREU Committee's twitter feed reported on the meeting and a full transcript will be available soon from the Committee website.

Appointments to the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement Joint Committee

The Withdrawal Agreement establishes a Joint Committee responsible for the implementation and application of the Agreement. The Joint Committee will be composed of representatives of the EU and of the UK and co-chaired by both sides. The UK or the EU may refer any issue relating to the functioning of the Withdrawal Agreement to the Joint Committee which is empowered to make decisions and recommendations by mutual consent.

On 1 March 2020, the UK Government confirmed that Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office, Michael Gove MP, will be the UK's co-chair of the Joint Committee. Paymaster General, Penny Mordaunt MP will act as the alternate co-chair.

Section 34 of the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 requires the UK Government to appoint a serving UK minister as the UK co-chair.