EU-UK future relationship negotiations Issue 1- February 2020

Following the UK's departure from the EU, the negotiations to determine the future relationship will begin on 3 March 2020. Over the course of the negotiations, SPICe will publish briefings outlining the key events, speeches and documents published. This first briefing covers the period since the UK left the EU on 31 January 2020.

Executive Summary

This briefing is the first in a series of SPICe briefings that will be published regularly during the negotiations on the future relationship between the EU and the UK. This first briefing covers the period since the UK left the EU on 31 January 2020. It provides analysis of the negotiating mandates adopted by the EU and the UK Government along with background on the negotiations. It also provides information on the positions of the Scottish Government and the other Devolved Administrations.

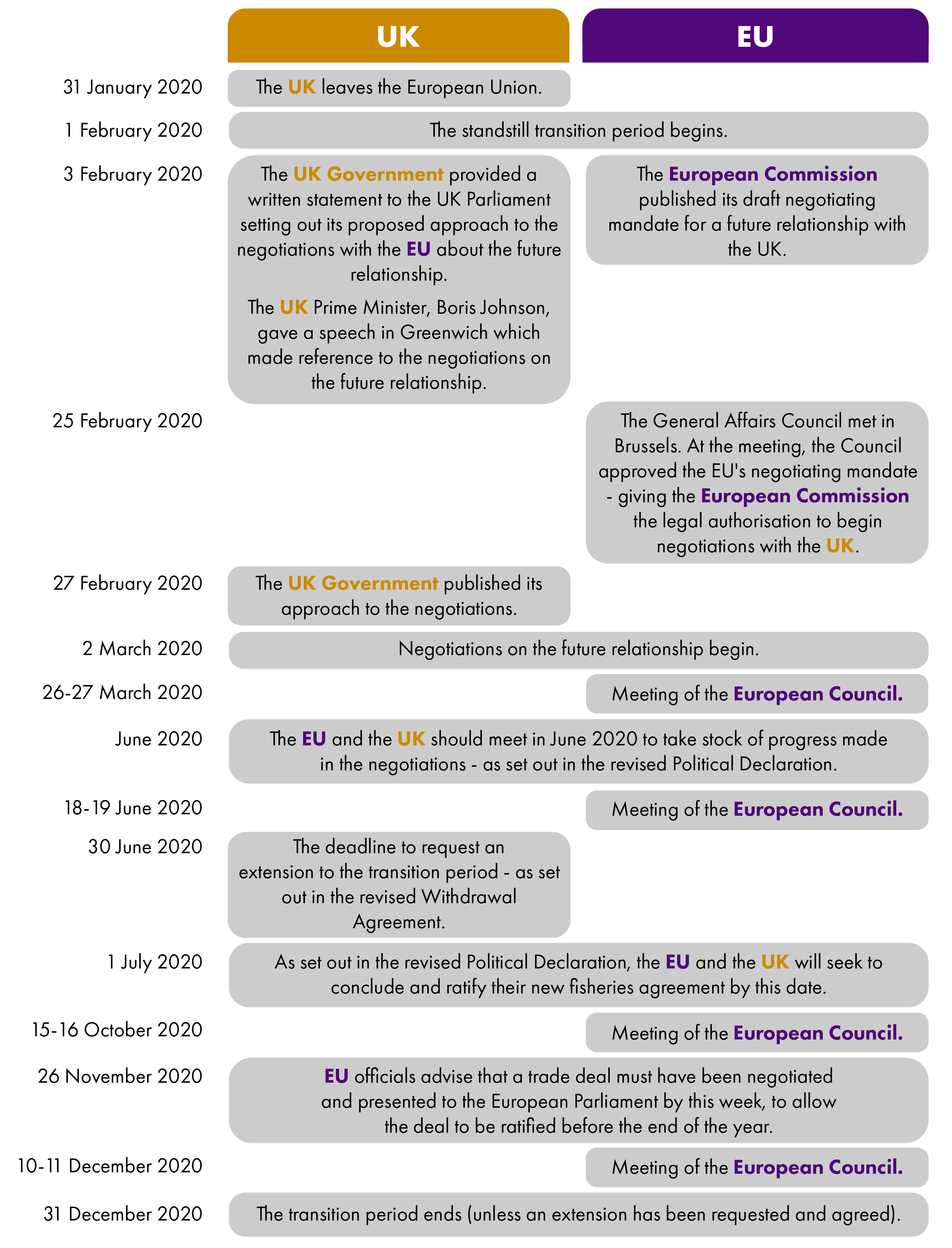

Timeline of negotiations

The approach of the EU and UK to the negotiations

Following its departure from the European Union on 31 January 2020, the UK entered into a standstill transition period which is due to last until 31 December 2020. During the transition period, the EU and the UK will undertake negotiations to determine the shape of the future relationship.

The negotiations will begin in Brussels during the week beginning 2 March. Further negotiating rounds will take place with the venue alternating between London and Brussels.

The Task Force for Relations with the United Kingdom will lead on negotiations for the EU. The Task Force coordinates the European Commission's work on all strategic, operational, legal and financial issues related to the UK’s departure and is led by Michel Barnier, who also led the Article 50 withdrawal negotiations.

The UK Government's approach to the negotiations will be guided by the UK Cabinet Sub-committee on EU exit strategy which is chaired by the Prime Minister. The Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, Michael Gove is deputy chair. The Prime Minister's chief negotiator, David Frost, will lead the negotiations for the UK.

There is no role on the Exit Strategy sub-committee for any of the territorial Secretaries of State in the UK Government. The UK Government's approach to the negotiations set out that whilst international relations, including relations with the EU are reserved, it recognises the interests of the devolved administrations:

The UK Government recognises the interests of the devolved administrations in our negotiations with the EU, and their responsibilities for implementation in devolved areas. The UK Government is committed to working with the devolved administrations to deliver a future relationship with the EU that works for the whole of the UK.

In January 2020, SPICe published Negotiating the future UK and EU relationship. This briefing set out the process for negotiating the new economic and security relationship between the UK and the EU and provided analysis of the key areas of negotiation from a Scottish perspective.

UK Government approach to the negotiations

On 3 April, the UK Government set out its proposed approach to the negotiations with the EU in a written statement to Parliament. Following this, on 27 February, the UK Government published a paper outlining its approach to the negotiations.

The UK Government approach paper set out its desire to negotiate a comprehensive free trade agreement. In addition, the UK Government approach is clear that it is seeking to reach a number of other agreements with the EU covering areas such as fisheries, law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters, transport, and energy.

The UK Government indicated that it did not believe that any of the agreements should result in the European Court of Justice having any jurisdiction in the UK. The UK Government also set out that it expects progress to be made leading up to the June high-level meeting with a broad outline of an agreement being in place by September:

The Government would hope that, by that point, the broad outline of an agreement would be clear and be capable of being rapidly finalised by September. If that does not seem to be the case at the June meeting, the Government will need to decide whether the UK’s attention should move away from negotiations and focus solely on continuing domestic preparations to exit the transition period in an orderly fashion.

In the event the UK Government concludes that a deal isn't possible with the EU by the end of 2020, the UK Government indicated that it would be prepared to trade with the EU on WTO terms.

The UK Government also indicated that it will, "invite contributions about the economic implications of the future relationship from a wide range of stakeholders via a public consultation". This consultation is expected to start in the spring. Further to this, the UK Government did not indicate whether it planned to produce an assessment of the economic impact of its proposed deal with the EU.

A comprehensive free trade agreement

The UK Government hopes to secure a free trade agreement that is based on the EU's free trade agreements with countries such as Canada and Japan. Consequently, the UK Government is seeking a free trade agreement which has the following features:

No tariffs, fees, charges or quotas between the UK and the EU.

Tackling technical barriers to trade, such as regulatory divergence building on World Trade Organisation rules.

Whilst the UK will maintain its own independent sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) regime to protect human, animal and plant life and health and the environment, in certain areas it may be possible to agree equivalence provisions with the EU to reduce practical barriers to trade at the border.

Customs and trade arrangements, covering all trade in goods, should be put in place to smooth trade between the UK and the EU.

The agreement should include measures to minimise barriers to the cross-border supply of services and investment, on the basis of each side’s commitments in existing free trade agreements. In areas of key interest, such as professional and business services, there may be scope to go beyond these commitments.

The agreement should address unnecessary regulatory measures to reduce impediments to the ability of UK service providers operating in the EU and EU service providers operating in the UK to compete on equal terms with domestic businesses.

The agreement should provide for the mutual recognition of professional qualifications between the UK and EU, underpinned by regulatory cooperation, so that qualification requirements do not become an unnecessary barrier to trade.

The agreement should require both sides to provide for a predictable, transparent, and business friendly environment for financial services firms, ensuring financial stability and providing certainty for both business and regulatory authorities, and with obligations on market access and fair competition.

Given the UK will leave the Single Market and Customs Union, the future economic relationship will see barriers erected between the UK and the EU compared to the position the UK enjoyed as an EU member state. In addition, whilst the UK Government is reserving the right to move away from continued alignment with EU standards, UK manufacturers wishing to sell goods into the EU Single Market will have to ensure those goods continue to comply with EU standards.

Geographical indications

Although the EU and the UK’s current geographical indications are protected under the Withdrawal Agreement, the UK Government's approach to the negotiations states that it will, "keep its approach under review as negotiations with the EU and other trading partners progress".

In addition, the UK is clear that any agreement on geographical indications must respect the rights of both the UK and the EU to set their own rules and the future directions of their respective schemes.

Fisheries

The UK Government's Approach to the Negotiations sets out its aim for a separate agreement on fisheries covering access to fish in UK and EU waters, fishing opportunities and future cooperation on fisheries management. Specifically, the UK Government would like to agree to annual negotiations on reciprocal access to UK and EU waters and on total allowable catches.

The approach to fisheries is set out in more detail below.

Participation in EU programmes

On participation in EU programmes, the UK Government states that it is ready to participate in EU programmes as a third country where it is in the UK's and EU's interests. The Approach to the negotiations suggests the UK Government is considering participation in the following programmes:

Horizon Europe

Euratom Research and Training

Copernicus

Elements of Erasmus+ "on a time-limited basis, provided the terms are in the UK's interests."

Law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters

On law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters, the UK Government indicated it is prepared to negotiate a separate agreement which covers:

arrangements that support data exchange for law enforcement purposes

operational cooperation between law enforcement authorities

judicial cooperation in criminal matters

facilitation of police and judicial cooperation between the UK and EU Member States

EU negotiating mandate

The European Commission published its draft negotiating mandate on 3 February 2020. Following this, on 25 February 2020, the General Affairs Council adopted a decision to authorise the opening of negotiations with the UK - formally nominating the European Commission as the EU negotiator.

The Council also adopted negotiating directives providing a mandate to the Commission for the negotiations. The mandate is based on the draft recommendations submitted by the European Commission.

The mandate sets out that the EU hopes to negotiate a comprehensive new partnership which covers the following areas:

trade and economic cooperation

law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters

foreign policy

security and defence

thematic areas of cooperation.

As with the EU’s Association Agreements, the mandate proposes that the future partnership will also include governance arrangements to ensure the proper functioning of the partnership.

In broad terms, the negotiating mandate mirrors the text of the Political Declaration on the Future Relationship which was agreed alongside the Withdrawal Agreement in October 2019.

The mandate also proposes that the future relationship should provide scope for the UK to continue to participate in EU funding programmes, subject to meeting the general rules for the programmes and providing financing towards the programmes.

The mandate confirmed the EU's conviction that any future partnership, "should be underpinned by robust commitments to ensure a level playing field for open and fair competition."

The European Commission welcomed the decision of the Council. President of the Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, highlighted the unified approach of the EU saying:

We are now ready to start negotiations with the United Kingdom. We want to build a close, ambitious future partnership, as this is in the best interest of people on both sides of the Channel. I would like to thank the European Parliament and all Member States for their continued trust in our negotiating team. We will work as hard as we can to achieve the best possible result.

Michel Barnier echoed this sentiment, stating:

We are determined to reach a deal that protects EU interests. We will work hand-in-hand with the European Parliament and all Member States and will continue to be fully transparent throughout this process.

The UK in a Changing Europe published its analysis of the EU’s mandate for the future partnership on 26 February 2020.

Economic relationship

Part II of the EU's mandate makes proposals in relation to the economic relationship between the EU and the UK, centred on the development of a free trade agreement based on zero tariffs and zero quotas on all goods entering the single market, along with a free trade agreement for services. The EU's offer in this area would be subject to agreement on level playing field provisions which are discussed in more detail below.

The mandate also proposes a partnership which would seek to optimise customs procedures and restrict technical barriers to trade, including different regulatory regimes and sanitary and phytosanitary measures by proposing an approach which goes beyond standard World Trade Organisation (WTO) agreements.

Geographical indications

Whilst the EU and the UK’s current geographical indications are protected under the Withdrawal Agreement, the EU's mandate proposes the establishment of, “a mechanism for the protection of future geographical indications ensuring the same level of protection as that provided for by the Withdrawal Agreement”.

Fisheries

The EU is seeking a permanent arrangement based on the, "existing reciprocal access conditions, quota shares and the traditional activity of the Union fleet" as part of the overall future relationship.

The approach to fisheries is set out in more detail below.

Participation in EU programmes

The EU's mandate proposes that the future relationship should provide scope for the UK to continue to participate in EU funding programmes, subject to meeting the general rules for the programmes and providing financing towards the programmes.

Security

In relation to security, the mandate proposes a close partnership comprising law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters, foreign policy, security and defence, as well as thematic cooperation in areas of common interest.

The mandate is clear that, for judicial cooperation to take place, the UK will be required to respect fundamental rights such as data protection along with continued compliance with the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the domestic implementation of the ECHR (the Human Rights Act).

Whilst the UK will no longer be able to participate in the European Arrest Warrant, the mandate proposes that there should be effective cooperation between law enforcement authorities " in line with arrangements for cooperation with third countries " in relation to judicial cooperation in criminal matters.

Key issues for negotiation

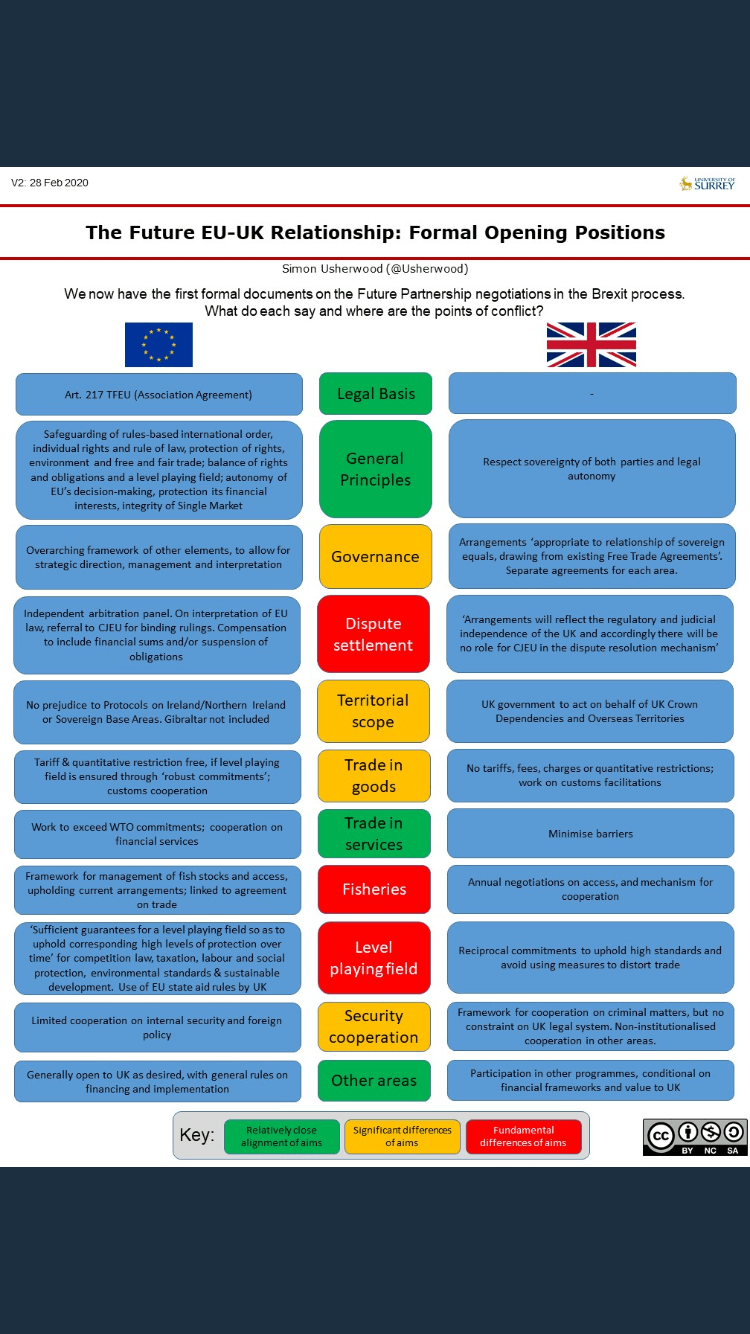

The Institute for Government has produced a helpful comparison of the UK and EU mandates and Simon Usherwood from the University of Surrey has produced an infographic summarising the areas of agreement and disagreement between the UK and EU positions. This infographic is reproduced below for information.

The Institute for Government also published an analysis of the future relationship priorities as set out by the EU and UK on 3 February 2020. The analysis considered the main "Brexit battles ahead" and declared that:

It was just a couple of working hours after the UK’s formal departure from the EU before the conciliatory approach of UK and EU leaders came to an end. Brexit sabres are once again being rattled, and the outlines of the big skirmishes ahead are now clear.

The clear differences between the UK and the EU focus on level playing field provisions and fisheries. These issues are discussed in more detail below.

Fisheries

According to the EU, failing to secure an agreement on fisheries would have wider implications for the negotiations as a whole. Bearing in mind the aim of reaching agreement on fisheries by 1 July 2020, the mandate is explicit that the outcome of the negotiations on fisheries access and quota shares will determine the wider terms of the economic partnership:

The terms on access to waters and quota shares shall guide the conditions set out in regard of other aspects of the economic part of the envisaged partnership, in particular of access conditions under the free trade area as provided for in Point B of Section 2 of this Part.

The EU is seeking a permanent arrangement based on the, "existing reciprocal access conditions, quota shares and the traditional activity of the Union fleet" as part of the overall future relationship.

The EU's negotiating mandate proposes a framework for the management of shared fish stocks and common technical and conservation measures for EU boats in UK waters and UK boats in EU waters.

The mandate also proposes that the management of fish stocks should be underpinned by the long-term conservation and sustainable exploitation of marine biological resources.

The UK Government is silent on trying to reach a fisheries agreement by 1 July 2020. The UK Government's Approach to the Negotiations sets out its aim for a separate agreement on fisheries covering access to fish in UK and EU waters, fishing opportunities and future cooperation on fisheries management. Specifically, the UK Government would like to agree to annual negotiations on reciprocal access to UK and EU waters and on total allowable catches.

Speaking in Greenwich on 3 February 2020, the Prime Minister said:

We are ready to consider an agreement on fisheries, but it must reflect the fact that the UK will be an independent coastal state at the end of this year 2020, controlling our own waters.

And under such an agreement, there would be annual negotiations with the EU, using the latest scientific data, ensuring that British fishing grounds are first and foremost for British boats.

Further consideration of the role of fisheries in the negotiations can be found in a House of Commons Library insight published on 12 February 2020 on "Brexit next steps: Fisheries."

Level playing field

Commitments to maintain a level playing field appear to be a key sticking point ahead of the negotiations starting. The "level playing field" (LPF) expression indicates a condition for the liberalisation of trade in goods between the UK and the EU: all companies competing in the same market must abide by the same rules.

For the EU and UK to create an area of liberalised trade in goods, the EU has proposed that the UK should adopt and maintain domestic rules that do not undercut EU standards, as this could result in a trade advantage for UK businesses. Reference to the LPF was included in the Political Declaration agreed in October 2019. This stated that, "the precise nature of commitments should be commensurate with the scope and depth of the future relationship and the economic connectedness of the Parties."

Given the proximity of the EU and UK markets, the EU has argued that these commitments should be extensive and deep, more so than is adequate in other trade relationships between the EU and third countries. For example, in a speech at the London School of Economics on 8 January 2020, the Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen, was clear that the depth of the future relationship will be dependent on the UK Government's approach to level playing field provisions saying:

Without a level playing field on environment, labour, taxation and state aid, you cannot have the highest quality access to the world's largest single market. The more divergence there is, the more distant the partnership has to be.

The position set out by the Commission President, is reflected in the EU's negotiating mandate which states that:

given the Union and the United Kingdom’s geographic proximity and economic interdependence, the envisaged partnership must ensure open and fair competition, encompassing robust commitments to ensure a level playing field...

... These commitments should prevent distortions of trade and unfair competitive advantages so as to ensure a sustainable and long-lasting relationship between the Parties. To that end, the envisaged agreement should uphold common high standards, and corresponding high standards over time with Union standards as a reference point, in the areas of State aid, competition, state-owned enterprises, social and employment standards, environmental standards, climate change, relevant tax matters and other regulatory measures and practices in these areas.

The UK Government has indicated that it is not prepared to align with EU rules with regards to LPFs. The Prime Minister set out the UK Government's position on LPFs on 3 February 2020 saying:

We will not engage in some cut-throat race to the bottom.

We are not leaving the EU to undermine European standards, we will not engage in any kind of dumping whether commercial, or social, or environmental, and don’t just listen to what I say or what we say, look at what we do.

The UK Government's Approach to the Negotiations makes no mention of a level playing field or regulatory alignment. On technical barriers to trade, the UK's paper states:

The Agreement should promote trade in goods by addressing regulatory barriers to trade between the UK and EU, while preserving each party’s right to regulate, as is standard in free trade agreements. It should apply to trade in all manufactured goods, as well as to agri-food products for issues not covered by sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) requirements. The Agreement should cover technical regulation, conformity assessment, standardisation, accreditation, metrology, market surveillance, and marking and labelling.

The UK Government's promise to avoid dumping and retain high regulatory standards does not constitute a binding commitment against a future deterioration of standards. As a result, for the viability of an advanced free trade area, the EU would prefer that the future relationship agreement includes a binding obligation on the UK (including on future governments) to retain high standards similar to those observed by the EU.

Whilst the UK and EU appear to disagree on a LPF, and continued commitment to a LPF involving continued UK alignment with EU rules, it may be enough to secure agreement if the UK Government commits to maintain the current EU rules, thus committing to a "non-regression" policy. Whether this is sufficient for the EU will be worth watching throughout the negotiations . Whether the EU sees a commitment to "non-regression" rather than permanent alignment remains to be seen.

In this vein, the European Parliament (which will have to approve any future UK-EU agreement) has emphasised the importance of regulatory alignment and mentioned that all LPF commitments between the UK and the EU should be made, "with a view to dynamic alignment." Dynamic alignment would require that UK standards change to reflect any future change in the EU ones - and vice versa. For instance, if the EU adopted a more stringent regulation on greenhouse gas emissions, the UK would be required to strengthen its rules to match it, otherwise UK businesses could derive an unfair advantage from the lower cost of complying with less stringent UK standards. While non-regression might be acceptable to the EU in other areas, it seems that, in the field of state aid, the EU will demand dynamic alignment.

In its negotiating directives, the EU seeks to reserve the power to react to any distortions caused by regulatory differences - using EU standards as a benchmark.

The Union should also have the possibility to apply autonomous, including interim, measures to react quickly to disruptions of the equal conditions of competition in relevant areas, with Union standards as a reference point.

The EU has also set out how it would seek to enforce LPF commitments included in a final agreement. In the case of a breach in relation to LPF commitments by the UK Government, the EU's negotiating mandate proposes the possibility of arbitration to resolve trade disputes, which can then lead to "appropriate remedies". It is likely that the more pertinent remedy for LPF breaches could be the raising of otherwise illegal custom duties to neutralise the distorting effect of the regulatory advantage. The imposition of sanctions has also been contemplated by the EU negotiators.

The UK Government's approach to the negotiations suggests that, rather than a need for compulsory dispute settlement, retaliation and fines, there should be softer monitoring and implementation systems such as those included in the EU-Canada deal (CETA) and the EU-Japan deal.

The EU negotiating mandate sets out demands for higher LPF commitments from the UK Government than it has obtained from Canada in the CETA agreement. Dynamic alignment and compulsory enforcement would suggest that the UK-EU agreement would impose more stringent rules than CETA does. CETA includes non-regression clauses on environmental and labour protection, which contain no clear binding obligation. For instance:

Art. 23.4(1) The Parties recognise that it is inappropriate to encourage trade or investment by weakening or reducing the levels of protection afforded in their labour law and standards.

CETA also includes "implementation" clauses, which do not prohibit weakening of standards (they fall short of "non-regression") but require Canada and the EU to effectively implement their standards:

23.4.2. A Party shall not waive or otherwise derogate from, or offer to waive or otherwise derogate from, its labour law and standards, to encourage trade or the establishment, acquisition, expansion or retention of an investment in its territory.

In case of breach of the CETA rules on labour or environmental protection, the aggrieved party can resort to an arbitration panel. Even if it finds a breach, however, the panel cannot impose penalties or sanctions. It therefore appears that, in terms of content, legal force and remedies for breach, the LPF rules that the EU wants for the deal with the UK are much more stringent than those in CETA. The EU negotiating madate sets out that the requirement for more stringent LPF rules in an agreement with the UK is due to geographic proximity:

Given the Union and the United Kingdom’s geographic proximity and economic interdependence, the envisaged partnership must ensure open and fair competition, encompassing robust commitments to ensure a level playing field.

Priorities of the EU member states

On 19 February 2020, SPICe published a guest blog written by Fabian Zuleeg, Chief Executive of the European Policy Centre. The blog focussed on the political priorities of EU member states ahead of the forthcoming negotiations on a future relationship. It suggested that the EU has the, "greater leverage in the negotiations, given asymmetric size and costs, as well as time pressure on the UK" but recognised that while the EU27 are, "likely to remain united in terms of the Brexit process" this unity may not extend to specific policy interests.

The blog highlighted a number of factors that may impact the ability of the EU and the UK to reach a deal before the end of the transition period. These include:

the limited time available to conclude a deal;

an extension to the transition period looking unlikely and

possible sources of conflict between EU countries

The blog suggested that there may be "direct confrontation" on some of the issues of contention between the EU and the UK - and an inability to secure a deal on fisheries might even lead to "clashes between UK and EU trawlers".

The blog concluded that, "given the EU’s leverage, if the UK wants even a basic deal by the end of December, the UK Government will have to concede to Member State interests, for example on fisheries, level playing fields and governance".

European Parliament resolution on the proposed mandate

The European Parliament will be required to give consent to any agreement reached between the EU and the UK. This role at the end of the process means Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) may be able to influence the future relationship negotiations as they progress by adopting resolutions which set out the position of the European Parliament. The European Parliament held a debate on 11 February 2020 on the proposed mandate for negotiations for a new partnership with the UK.

The President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, and the Head of the Task Force for Relations with the UK, Michel Barnier, both participated in the debate. The President called for the negotiators to show ambition in the areas of social protection, climate action and competition rules but emphasised that a zero tariff and a zero-quota trade deal was dependent on the UK agreeing to, "guarantees on fair competition and the protection of social, environmental and consumer standards."

Following the debate, the Parliament voted on 12 February to adopt a resolution providing MEPs’ initial input to the upcoming negotiations with the UK. The text was adopted by 543 votes to 39, with 69 abstentions.

MEPs agreed that the future agreement with the UK should be as, "deep as possible" and based on, "three main pillars:

an economic partnership;

a foreign affairs partnership and;

specific sectoral issues.

In addition, MEPs were clear that, as a former Member State, the UK could not retain the same rights as before and that the integrity of the Single Market and the Customs Union must be preserved at all times.

The resolution adopted by the European Parliament also set out MEPs' position on the contentious issues of fisheries and level playing field commitments. It stated that in order to gain Parliament’s consent, "a EU-UK free trade deal must be conditional on a prior agreement on fisheries by June 2020."

The resolution also called for dynamic alignment of EU and UK laws, and level playing field commitments in areas including the environment, tax, state aid and consumer protection, stating that:

if the UK does not comply with EU laws and standards, the Commission should “evaluate possible quotas and tariffs for the most sensitive sectors as well as the need for safeguard clauses to protect the integrity of the EU single market.”

European Parliament Coordination group

A new European Parliament EU-UK coordination group met for the first time in the European Parliament on 5 February 2020. The Head of the Task Force for Relations with the United Kingdom, Michel Barnier, also attended the meeting. The group was set up ahead of the negotiations on the future relationship, to coordinate the varied work of the European Parliament Committees involved in the negotiations.

German MEP, David McAllister, is the Chair of the coordination group. McAllister is half Scottish with his father having served with the British Army in West Germany.

The group allows the European Parliament to discuss the negotiations with Michel Barnier and the Task Force. The group announced that it had:

agreed with Mr Barnier that there will be briefings before each round of negotiations, and there will be de-briefings after each round of negotiations. This means that the European Parliament is informed in an orderly manner at every stage of the upcoming negotiations.

The Institute for Government has published an explainer on the EU institutions involved in the negotiations on a future relationship, which covers the role of the European Parliament.

UK Government priorities - speech by David Frost

Ahead of publication of the UK Government's approach to the negotiations, the Prime Minister's chief negotiator, David Frost, set out the position of the UK Government in more detail during a speech on 17 February 2020 at the Universite Libre de Bruxelles. The speech highlighted the differences between the EU and the UK in their priorities for the negotiations and outlined the fundamental principles of the UK's negotiating position.

David Frost said that the UK Government was clear that it wanted an agreement based on a Canada-type free trade agreement but, if this could not be secured, the government was "ready to trade on Australia-style terms". This would in effect mean trading with the EU under World Trade Organisation rules.

A clear theme of the speech was sovereignty and the opportunities for the UK Government to establish rules that benefit the UK. This position sets the UK at odds with the EU's demands for close alignment and level playing field commitments. Frost confirmed that, for the UK:

... we bring to the negotiations not some clever tactical positioning but the fundamentals of what it means to be an independent country. It is central to our vision that we must have the ability to set laws that suit us – to claim the right that every other non-EU country in the world has. So to think that we might accept EU supervision on so-called level playing field issues simply fails to see the point of what we are doing. That isn’t a simple negotiating position which might move under pressure – it is the point of the whole project. That’s also why we are not going to extend the transition period beyond the end of this year. At the end of this year, we would recover our political and economic independence in full – why would we want to postpone it? That is the point of Brexit.

In short, we only want what other independent countries have.

The speech acknowledged that divergence between the EU and the UK may create friction and barriers that previously did not exist. Frost advised that the UK Government had factored this in but still foresaw gains from its ability to negotiate as an independent country. As a consequence, he said the government were, "not prepared to compromise on some fundamentals of our negotiating position."

Jill Rutter, senior fellow at The UK in a Changing Europe has written about David Frost's role in the negotiations.

Michel Barnier's response to David Frost's speech

Speaking at a press conference on 25 February 2020, Michel Barnier noted his surprise at David Frost's speech, commenting:

Mr Johnson’s spokesman said the main objective of the UK in these negotiations is to ensure that we obtain the economic and political independence of the United Kingdom on 1 January this year, but, no, that is not true. The economic and political independence of the UK doesn’t need to be negotiated on its been done, it’s been achieved, that’s what Brexit has achieved. It was the will of the UK and they’ve left.

Nobody’s going to discuss the sovereignty, the independence or the autonomy of the UK that’s not the purpose of these negotiations. I was very surprised to read this, supposedly something that was said by a spokesman from Downing Street.

Role of the devolved administrations in negotiations

The role the devolved administrations will have in the negotiations is yet to be made clear by the UK Government.

Scottish Government

Following the publication of the UK Government's approach to the negotiations, the Scottish Government published a news release in which the Cabinet Secretary for Government Business and Constitutional Relations, Michael Russell, said that the UK Government's proposed deal "could cost the Scottish economy between £9 billion and £12.7 billion by 2030 compared with EU membership". The Cabinet Secretary also indicated that the UK Government's mandate took no account of the Scottish Government’s views on any of the core issues and that as a result the Scottish Government:

“Will continue to argue for a closer relationship with the EU and will assert our right to align with EU rules where we wish to. We will also consider whether we can take part in future EU programmes in devolved areas, even when the UK Government does not.

“The mandate published today has been drawn up without taking account of the Scottish Government’s views on any of the core issues and will implement a Brexit the Scottish people overwhelmingly rejected. We cannot endorse it. The case for Scotland’s right to choose its own future grows stronger.”

In response to a Parliamentary Question lodged in January 2020, Michael Russell, highlighted the lack of clarity around the role of the Scottish Government in negotiations on the future relationship.

He said:

The Scottish Government have been clear that, to date, engagement in relation to the future relationship negotiations has been woefully inadequate. Despite the commitment set out by the UK Government in relation to the Northern Ireland Executive, and previous commitments made by the UK Government to all devolved administrations in the context of the Joint Ministerial Committee (EU Negotiations), we have not been invited to engage meaningfully or at the level now foreseen for Northern Ireland. At a recent meeting of that committee in London I reiterated the point that the Scottish Government must be involved in the negotiations in order to ensure that Scottish interests are adequately protected. The question around the role of the devolved administrations in the future relationship negotiations was raised as far back as February 2018 and yet remains unresolved almost two years later.

First Minister's speech

During a trip to Brussels on 10 February 2020, the First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, met with the Head of the Task Force for Relations with the UK, Michel Barnier, to discuss the forthcoming negotiations.

Referring to the negotiations in a speech made later that day at the European Policy Centre in Brussels, she said that the Scottish Government would, "do what we can to work as closely and as constructively as possible with the UK Government." She continued:

In doing so, we will try to influence negotiations in a way which benefit Scotland, the UK and the EU. In particular, we will stress the value of having as close a trading relationship with the EU as possible.

The First Minister expressed her concerns at the prospect of the UK diverging from EU standards and, as a result, losing access to the single market. Referring to the Prime Minister's speech of 3 February 2020, she suggested the freedom to diverge from EU standards raised the possibility of the UK lowering standards in areas, including health, safety, the environment and workers’ rights.

Suggesting a different approach to the UK Government, she said that the Scottish Government, "largely support the idea of a level playing field" adding that the Scottish Government would "continually make that case as the negotiations proceed."

Cabinet Secretary for Government Business and Constitutional Relations gives evidence to the European Committee

On 20 February 2020, the Cabinet Secretary for Government Business and Constitutional Relations, Michael Russell, gave evidence to the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee on the Withdrawal Agreement and Negotiation of the Future Relationship.

The Cabinet Secretary was asked whether the UK Government would involve devolved administrations in the negotiation process. The Cabinet Secretary said that he didn't expect this to happen because of the UK Governments, "absolute conviction that the sovereignty of the UK Parliament is the most important issue."

He also explained the "three-room model" he had proposed for the devolved administrations role in negotiations, which is set out below:

The first room is where the devolved Administrations and the UK Government would put on the table their position on a subject. Fishing might be an example, although there are many others. We would go in and say what we need and want for that. If we were able to get through that room by negotiating to a common position, we would enter the second room, which is where the UK negotiating mandate would be decided on. That would require all sides to compromise and come together to decide what could be done. That is not to say that we would agree with it all or that it would be good, but we could do that.

If we could sign up to the mandate, the third room is where the negotiation would take place. I have no ambition for the Scottish Government to be in that room, but the parallel would be Scotland’s former presence at the European Council. I have been at European councils as a minister in various portfolios, so I know that you very rarely get to speak. That is disgraceful, particularly with fisheries. Although Fergus Ewing goes to the meetings, he is not running the negotiation or negotiating effectively, because he is not allowed to, but there is a parallel of speaking and being involved in such meetings. I have represented the UK in at least one European Council meeting, for a variety of reasons. The third room is the negotiation. Most of the time, the UK Government would be there, but it would be operating on a mandate that had been agreed by the devolved Administrations.

That is a model. It requires the UK to accept that there would be meaningful negotiation at the first two stages, but there is no such acceptance at the moment.

The Cabinet Secretary was also asked how the Scottish Government proposes to work with EU institutions in the future. He responded:

Whatever our constitutional position, the EU will continue to be of enormous importance to us and to have influence over us. That is part of the stupidity of Brexit. On our doorstep will be one of the world’s largest trading blocs, but it is much more than a trading bloc: it has common values, and objectives of improving the lives of its citizens, in a way with which we have strong empathy. We want to make sure that our engagement is positive and that it continues. That is also true for many of our businesses. It is vital that we have a continued, productive presence there. We have a big role to fulfil.

We also want to make sure that the EU understands our empathy and our desire to be, not uncritical in our relationship, but to work through it to full independent membership. The Government is quite open about that objective. We have short-term goals, to continue to benefit; medium-term goals, to continue to build our relationship; and slightly longer-term goals, although I do not think it is so far away, of entering as a full member.

Welsh Government

On 20 January 2020, the Welsh Government published its Negotiating priorities for Wales. In the document, the Welsh Government called for a free trade agreement with level playing field provisions and dynamic regulatory alignment.

The Welsh Government also proposed that:

the UK should prioritise EU markets over trade arrangements with other countries;

the UK and EU should agree the fullest possible future security partnership - replicating current arrangements including internal and external cooperation - as far as this is possible;

the UK's continued participation in EU funding programmes including Erasmus+, Horizon Europe, Creative Europe and INTERREG;

the UK Government should recognise that devolved governments may look to be involved in EU programmes that some or all of the rest of the United Kingdom are not involved; and

the UK Government should ensure that the Devolved Governments must be fully involved in the negotiations and in the Joint Committee that will oversee the implementation of the agreements.

In terms of the role of the Welsh and other devolved governments in the negotiations, the document said:

It is essential that the Welsh Government, and the other devolved governments, are part of the negotiations to shape a future that works for all parts of the UK. The devolved governments to date have been treated as a consultee in the process of setting a UK position. Information sharing and consultation with the devolved governments falls a long way short of the arrangements necessary to ensure UK positions truly reflect the positions of all parts of the Union.

Key Publications

UK Government

3 February 2020. UK Government: Prime Minister Boris Johnson's speech in Greenwich.

3 February 2020. UK Government: Written statement to Parliament - the Future Relationship between the UK and the EU.

17 February 2020. UK Government: David Frost lecture: Reflections on the revolutions in Europe.

27 February 2020. UK Government: The Future Relationship with the EU. The UK’s Approach to Negotiations.

EU

3 February 2020. European Commission: Publication of the EU’s draft negotiating mandate.

3 February 2020. European Commission: Statement by Michel Barnier at the presentation of the Commission's draft negotiating mandate.

3 February 2020. European Commission: Slides used by Michel Barnier during the presentation of the Commission's draft negotiating mandate.

3 February 2020. European Commission: Questions and answers on the draft negotiating directives for a new partnership with the United Kingdom.

6 February 2020. European Commission: Task Force for Relations with the United Kingdom Organigramme.

12 February 2020. European Parliament: EU-UK future relations: “level playing field” crucial to ensure fair competition.

25 February 2020. Council of the European Union: ANNEX to COUNCIL DECISION authorising the opening of negotiations with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland for a new partnership agreement.

25 February 2020. European Commission: News release on the Future EU-UK Partnership: European Commission receives mandate to begin negotiations with the UK.

25 February 2020. European Commission: Future EU-UK Partnership: Question and Answers on the negotiating directives.

25 February 2020. Council of the European Union: EU-UK negotiations infographic.

Scottish Government

10 February 2020. Scottish Government: European Policy Centre First Minister's Speech.

Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe)

17 January 2020. SPICe Briefing: Negotiating the future UK and EU relationship

4 February 2020. SPICe blog: Brexit Phase 2 begins – The EU’s approach.

4 February 2020. SPICe blog: Brexit Phase 2 begins – The UK’s approach.

19 February 2020. SPICe blog: Negotiating the future relationship – priorities of the EU member states.

UK Parliament

12 February 2020. House of Commons library insight: Brexit next steps: Fisheries.

Further reading

3 February 2020. Centre on Constitutional Change: Brexit and the Union.

3 February 2020. Institute for Government: More Brexit battles ahead as the EU and UK set out future relationship priorities.

3 February 2020. Institute for Government: UK–EU future relationship negotiations: how do the opening positions compare?

5 February 2020. The UK in a Changing Europe: It’s not clear how close the relationship between the UK and the EU will be post-Brexit.

12 February 2020. Institute for Government: Agreeing a future EU–UK deal is not the biggest of the EU’s Brexit headaches.

26 February 2020. The UK in a Changing Europe: The EU’s mandate for the Future Partnership.