Forensic Medical Services (Victims of Sexual Offences) (Scotland) Bill

The Forensic Medical Services (Victims of Sexual Offences) (Scotland) Bill sets out proposals to make health boards responsible for providing forensic medical services to victims of sexual offences (and victims of harmful sexual behaviour by children). The Bill also seeks to make forensic medical examination available on a self-referral basis for people over the age of 16. This briefing outlines the proposals in the Bill and the views expressed in the written evidence received by the Health and Sport Committee.

Executive Summary

The Bill seeks to make health boards responsible for providing forensic medical services to victims of sexual offences (and victims of harmful sexual behaviour by children). These services are currently provided by health boards under a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Police Scotland and NHS Scotland. The Bill seeks to make this a specific statutory duty.

A forensic medical examination is an examination which looks for injuries and collects samples that may be used as evidence in a police investigation and any subsequent prosecution.

The Bill seeks to make forensic medical examination available on a self-referral basis for people over the age of 16.

Self-referral would mean that victims of sexual abuse and rape would be able to access a forensic medical examination without first reporting the incident to the police.

The Bill would place a duty on each health board to provide, or secure the provision of a forensic medical examination service to victims and provide a retention service for the storage of evidence collected.

The Bill would also require health boards to identify and address the healthcare needs of people who present for a forensic medical examination. This would be required even if an examination did not take place.

The Scottish Government has modelled estimates of future additional service demand resulting from the availability of self-referral. It estimated that, in 2021-22, the legislation would result in between 67 (low estimated demand) and 90 (high estimated demand) additional forensic medical examinations1. This is approximately a 10% increase2.

The Health and Sport Committee issued a call for views on the Bill between 6 December 2019 and 30 January 2020. It received 34 responses.

The majority of respondents were supportive of the Bill.

The key issues raised in written evidence in relation to the examination service focused on the practicalities associated with the examination, such as the sex of the examiner, out of hours services, referrals etc. There was much discussion of issues around capacity and consent and services for children and young people. Supported decision making, advocacy and psychological support were also raised as important considerations.

The key issues of concern in relation to the retention service included maintaining the chain of evidence, data protection, storage of evidence and timescales for retention.

In terms of the resource implications of the Bill, the potential costs to health boards and workforce implications were highlighted as key concerns.

A number of other issues were raised by respondents relating to the Memorandum of Understanding, information sharing, monitoring and evaluation, sharing best practice and continuous improvement.

The Health and Sport Committee will undertake an informal session with victims of sexual assault and rape who have experience of using forensic medical services, and take oral evidence from stakeholders and the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, before publishing its Stage 1 Report.

Introduction

The Forensic Medical Services (Victims of Sexual Offences) (Scotland) Bill (the Bill) is a Scottish Government Bill which was introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 26 November 2019 by the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, Jeane Freeman MSP.

The Bill seeks to place a duty on health boards to provide forensic medical services to victims of sexual offences (and victims of harmful sexual behaviour by children under the age of criminal responsibility (this will be 12 years of age when the provisions in the Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Act 2019 come into force). The Bill also seeks to make forensic medical examination available on a self-referral basis for people over the age of 16.

The Policy Memorandum notes that the main policy objective of the Bill is to improve the experience, in relation to forensic medical services, of people who have been affected by sexual crime.

The Scottish Government consulted on forensic medical services for victims of sexual offences between 15 February and 8 May 2019. 53 responses were received (of which 50 were published). In August 2019, the Scottish Government published an Analysis of Responses.

Alongside the Bill the Scottish Government published five impact assessments:

It also published an easy read summary of the Policy Memorandum.

Prevalence of sexual crimes

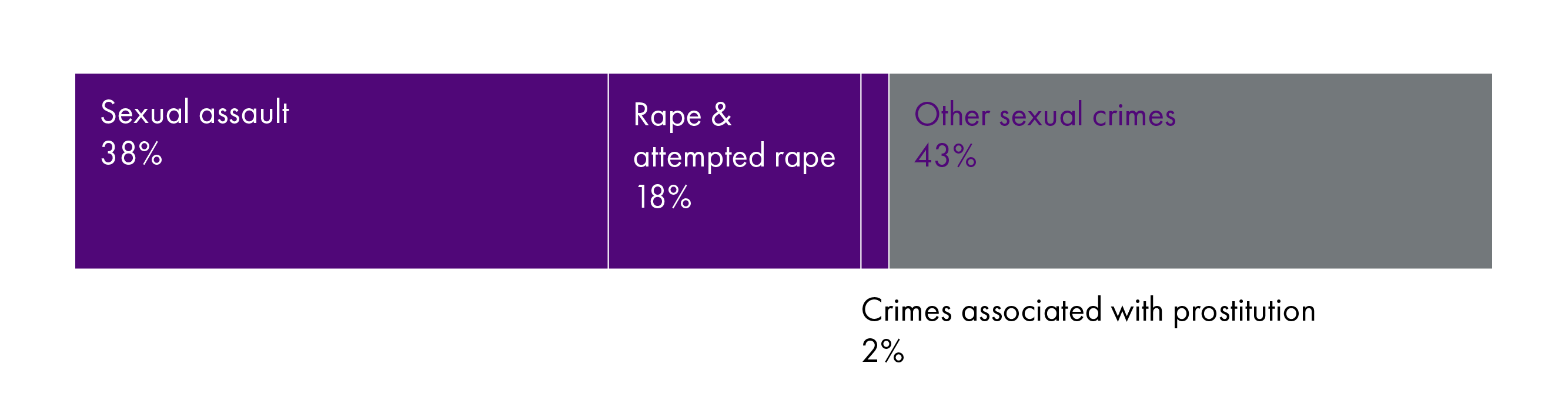

In 2018-19, there were 13,547 sexual crimesi recorded by the police in Scotland and sexual crimes accounted for 5% of all crimes recorded in 2018-19. The number of sexual crimes recorded by the police increased by 8% from 12,487 in 2017-18 to 13,547 in 2018-192.

Official police figures should be viewed with caution as it is widely accepted that many sexual offences are not reported to police. The Scottish Crime and Justice Survey (SCJS) 2017-18 reported that only 23% of respondents reported the most recent (or only) incident of forced sexual intercourse to the police3.

The SCJS reported that 3.6% of adults in Scotland have experienced at least one type of serious sexual assault since the age of 16. A higher proportion of women than men reported experiencing at least one type of serious sexual assault (6.2% compared to 0.8%, respectively).

The SCJS also reported that, of the people who had experienced forced sexual intercourse, over three-quarters (77%) said that the last (or only) incident had resulted in some form of physical impact (either minor (41%), serious but not treated by a medical professional (20%) or serious and treated by a medical professional (17%)). Eight percent said that the last (or only) incident had resulted in pregnancy.

Sexual crimes experienced by people under the age of 18

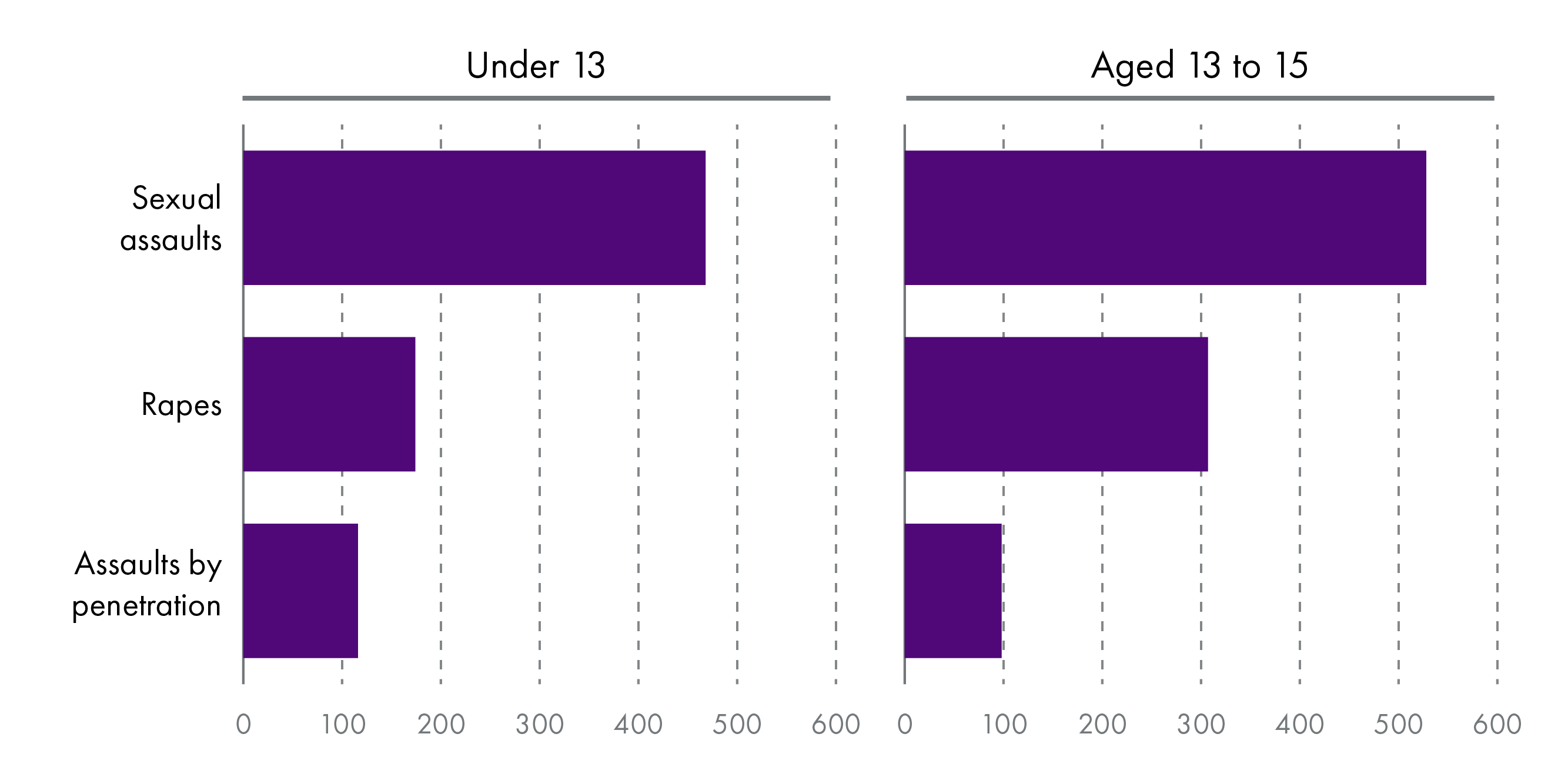

Figures from Recorded crime in Scotland: 2018-2019 indicate that at least 39% of the 13,547 sexual crimes recorded in 2018-19 by the police related to a victim under the age of 18.

Current situation

Forensic medical examinations are currently carried out by health boards under a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between them and Police Scotland. This sets out the responsibilities of each organisation.

The MoU goes beyond the provision of forensic medical examinations for victims of sexual offences and rape. It includes pronouncing death at a scene, examination and collection of forensic samples from alleged perpetrators, providing healthcare and undertaking examination of suspects detained under counter terrorism legislationi.

Currently, in most areas, forensic medical examinations can only be carried out following a referral from Police Scotland once an incident had been reported to the police.

Background to the Bill

In March 2017, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary in Scotland (HMICS) published its report Strategic Overview of Provision of Forensic Medical Services to Victims of Sexual Crime. The report made 10 recommendations (Appendix A). Including:

Recommendation 1:

The Scottish Government should review the legal basis for the current agreement between Police Scotland, the Scottish Police Authority and NHS Scotland to deliver healthcare and forensic medical services. This review should inform the nature and need for any refreshed national Memorandum of Understanding between the parties.

Recommendation 7:

The Scottish Government should work with relevant stakeholders and professional bodies, including NHS Scotland, Police Scotland and the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service to develop self-referral services for the victims of sexual crime. This should clarify the legal position for obtaining and retaining forensic samples in the absence of a report to the police and support formal guidance for NHS Boards and Police Scotland.

That month, the Scottish Government announced that the "chief medical officer for Scotland will chair a group of experts from health and justice services to ensure that health boards improve the provision of appropriate healthcare facilities for any victim who requires a forensic examination"1.

A taskforce for the improvement of services for adults and children who have experienced rape and sexual assault was established and held its first meeting in April 2017.

In May 2017, the then Cabinet Secretary for Justice, Michael Matheson MSP made a statement on the work of the Scottish Government to address concerns about the provision of forensic examination services.

The taskforce's high level work plan 2017-2022 included the vision:

Consistent, person centred, trauma informed health care and forensic medical services and access to recovery, for anyone who has experienced rape or sexual assault in Scotland.

The taskforce had five subgroups, each with responsibility for delivering different elements of the vision.

Leadership and governance: shared vision and commitment to ensuring consistent, trauma informed service.

Workforce and training: trauma informed care delivered by a sustainable, supported workforce.

Design and delivery of services co-ordination, design and management of services that reflect local needs.

Clinical pathways: improving health and well-being by ensuring a consistent, trauma informed health care response.

Quality improvement: continuous improvements inform service planning, commissioning and monitoring.

More recently, the leadership and governance subgroup has evolved into a legislation subgroup for the Bill and a self-referral subgroup has been created with a remit of providing guidance to health boards on the provisions in the Bill related to self-referral.

Support for victims of sexual offences

The proposals set out in the Bill would sit alongside other measures, both existing and planned, aimed at improving the experience of sexual offence victims in the criminal justice system. Current legal provisions include what are known as ‘special measures’ for vulnerable witnesses, including complainers in cases involving a sexual offence. Special measures are intended to assist vulnerable witnesses in giving evidence (e.g. by allowing a witness to give evidence from somewhere outside the courtroom by way of live television video link).

Bodies which provide advice and support to victims of sexual offences include a network of rape crisis centres across Scotland. These centres employ advocacy workers who are able to offer support to victims. Advocacy workers can help victims decide whether or not to report an incident to the police. The National Advocacy Project provides support and information through all stages of the Criminal Justice System, from before a statement is made through to the resolution of a court case.

The Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research published a report on the Evaluation of the Rape Crisis Scotland National Advocacy Project in 2018. It made 12 recommendations on issues such as training, support for workers, publicity, workload of advocacy workers and funding.

Information on other steps being taken to improve support for victims of sexual offences is set out in the Policy Memorandum (paras 73 to 81).

The use of nurse examiners

The Policy Memorandum notes that a proposal for a nurse sexual offence examiner project has recently been endorsed by the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and the Lord Advocate. The aim of this is to develop the role of nurse sexual offence examiners to enable them to undertake forensic medical examinations and to give evidence in court. Currently, forensic medical examinations can only be carried out by doctors i. This project is due to start in summer 20201.

Currently, a forensically trained nurse can be present during a forensic medical examination along with the doctor to provide trauma-informed support to the victim, fulfil the General Medical Council (GMC) requirements for a chaperone and to act as a corroborating witness in line with the requirements of the criminal justice system1.

Forensic medical examinations

The Policy Memorandum notes that, in the context of sexual offences, the primary aim of a forensic medical examination is to assess the healthcare needs of the victim and to capture any forensic evidence of the alleged assault (such as DNA), which may provide evidence that intimate contact has taken place and be used to support any subsequent criminal investigation1.

The taskforce has consulted on clinical pathways to support adults who have experienced sexual assault. This details the processes for undertaking a healthcare and forensic medical examination (section 7 of the adult clinical pathway). A healthcare and forensic medical examination can include:

Healthcare assessment and aftercare which should involve supporting the healthcare needs of the individual. This may include treating injuries, safety assessment, emergency contraception, testing and arranging treatment for sexually transmitted infections and psychosocial assessment and support.

If the victim wishes to have a forensic medical examination this should be carried out first in order to preserve as much forensic evidence as possible. However, it might be necessary to prioritise some healthcare needs.

A forensic medical examination may include a detailed head to toe examination, identifying the presence or absence of injury, identifying any medical conditions that may affect interpretation, contributing to informing an opinion on timing, mechanism and causation of injury, documenting and interpretation of any forensically relevant features or injuries and the collection of appropriate forensic specimens2.

The final adult clinical pathway is expected to be published in the near future.

The taskforce has also consulted on the clinical pathway for children and young people who have disclosed sexual abuse. Similar to the adult pathway, the primary purpose of the medical examination is to address the health and wellbeing of the child in a holistic manner. This includes considering the child’s physical health, sexual health needs, their immediate and long-term emotional wellbeing, and arranging appropriate ongoing care. The secondary purpose is to collect forensic evidence for police and court proceedings, including video documentation of the examination and appropriate forensic swabs3.

The clinical pathway for children outlines how a Joint Paediatric Forensic Examination (JPFE) can combine a medical assessment with the need for corroboration of forensic findings and the taking of appropriate specimens for trace evidence such as semen, blood and transferred fibres. It notes that the paediatrician is responsible for assessing the child’s health and development and for ensuring that appropriate arrangements are made for further medical investigation, treatment and follow-up. The forensic medical examiner is responsible for the forensic element of the examination and for fulfilling the legal requirements in terms of preserving the chain of evidence.

Number of forensic medical examinations

The Financial Memorandum states that there is relatively little useful data on the current use of forensic medical services for victims of sexual offences in Scotland and the rest of the UK.

At the request of the taskforce, the Information Services Division (ISD) of National Services Scotland (NSS) undertook a review of the evidence, Demand Information to Support CMO Taskforce for the Improvement of Services for Victims of Rape and Sexual Assault, which estimated the demand for adult forensic medical examinations as between 15 and 20 per 100,000 of the population per annum1- which would equate to approximately 980 examinations a year.

In the Financial Memorandum, the Scottish Government has modelled estimates of future additional service demand (resulting from the availability of self-referral) based on three levels of projected service demand. It is estimated that, in 2021-22, the legislation will result in between 67 (low demand estimate) and 90 (high demand estimate) additional forensic medical examinations2.

Standards and indicators

In December 2017, Healthcare Improvement Scotland (HIS) published standards relating to the provision of Healthcare and Forensic Medical Services for People who have experienced Rape, Sexual Assault or Child Sexual Abuse. The standards cover leadership and governance, person-centred and trauma-informed care, facilities for forensic examinations, educational, training and clinical requirements, and consistent documentation and data collection. The standards are intended to complement existing standards and guidelines including the Child Protection Managed Clinical Network Standards of Service Provision and Quality Indicators for the Paediatric Medical Component of Child Protection Services in Scotland.

In 2018, the taskforce commissioned HIS to develop a set of indicators to support implementation and monitoring of the 2017 standards.These were published in December 2018. HIS has recently consulted on a final set of quality indicators (the consultation closed 19 December 2019), and these are due to be published shortly1.

The indicators are intended to apply to all services and organisations (including health boards and integration authorities) responsible for the delivery of healthcare and forensic medical examinations for people who have experienced rape, sexual assault or child sexual abuse.

The indicators cover person-centred and trauma-informed care, facilities for forensic examinations, consistent documentation and data collection.

A national DNA decontamination protocol for forensic medical examinations has been published and is being implemented by health boards and in December 2019, a draft specification for the requirements for Forensic Medical Examination facilities was published.

Barnahus model

The taskforce has been considering the design and delivery of services for forensic medical examinations taking into consideration the principles of the Barnahus model1.

The original, Icelandic Barnahus (Children’s House) is a child-friendly, interdisciplinary and multi-agency centre that allows different professionals investigating suspected child sexual abuse cases and providing appropriate support for child victims to work together in one place. The concept has been adopted by many European countries and takes a variety of forms, some include forensic medical examinations and others do not 2.

HIS and the Care Inspectorate have been asked by the Scottish Government to develop a set of standards for a Barnahus response to children and young people who have been victims and witnesses of violence in Scotland3. They carried out a scoping workshop in June 2019 and published a report outlining the areas the standards will cover:

Leadership and governance.

Inter-agency working and collaboration.

Child and family-centred design.

Information and supported decision-making.

Evidence collection.

Staff training, roles and responsibilities.

Follow-up treatment, support and advocacy.

These standards are intended to provide a road map for the development of a Barnahus model in Scotland and will be consulted on in spring 2020.

In January 2020, the Scottish Parliament's Justice Committee visited child-friendly evidence rooms in Glasgow.

National dataset

The taskforce has commissioned ISD Scotland to develop national datasets for adults and for children and young people, which seek to ensure consistent recording and reporting of data1. The Policy Memorandum notes that the national data sets will enable a national standardised form and requirements for a national clinical IT system to be finalised. The data sets and the national form will be published in the near future2.

The Policy Memorandum states that the intention is for health boards to start national data collection, to measure performance against the HIS standards and indicators, from April 2020 with the first publication around autumn 2021.

The quality improvement subgroup of the taskforce is developing proposals for a national clinical IT system. An outline business case setting out options is currently being considered by the taskforce2.

Information sharing

The Scottish Government has consulted on information sharing agreements between NHS Scotland boards and Police Scotland with the aim of bringing national consistency to how information in relation to victims of rape or sexual assault is shared between them. The Information Governance Delivery Group under the remit of the Taskforce are currently considering the responses received1.

The Bill's provisions in detail

The Bill would place a duty on each territorial health board to provide, or secure the provision of:

An examination service that provides forensic medical examinations to victims of sexual offences and victims of harmful sexual behaviour by a child under the age of criminal responsibility.

A retention service for the storage of evidence collected during forensic medical examinations.

The examination service

The Bill would place a statutory duty on health boards to provide forensic medical services to people who report that they have been the victim of a sexual offences.

The health board would be required to provide a forensic medical examination for anyone referred by Police Scotland, or to people who self-refer. Self-referral is when a person requests a forensic medical examination without the incident being first reported to the police. A person who self-refers could subsequently decide to involve the police but would not be obliged to do so.

The Bill would only make self-referral available to people aged 16 or older. A health board would not be able to undertake a forensic medical examination of younger child without police involvement.

The Bill provides that forensic medical examinations will be carried out for purposes including the collection of evidence for use in investigation or proceedings relating to the offence.

The Bill would not give an individual a right to a forensic medical examination. Examinations would only be carried out based on professional judgement. The Explanatory Notes state that professional judgement includes both clinical and non-clinical elements and that this is supported by guidance from the Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine1. The Explanatory Notes give the example of an examination not being appropriate when someone seeks it outside the forensic DNA "capture" window, which is generally seven days.

The Bill would require health boards to provide victims with information on what will happen with any evidence collected as part of a forensic medical examination and explain this information to the victim. In cases of police referral, evidence would be transferred to the police. In cases of self-referral, evidence would be transferred to the police only when requested following the reporting of the incident. It also outlines a victims right to request the return of certain items (such as clothing) and the destruction of evidence (such as samples).

The Bill would also require health boards to identify and address the healthcare needs of the victim - and this would be required even if a forensic medical examination did not take place.

Self-referral

The Bill seeks to address recommendation 7 of the Strategic Overview of Provision of Forensic Medical Services to Victims of Sexual Crime, by making it possible for victims of sexual offences and rape to access a forensic medical examination without first reporting the incident to the police. The Policy Memorandum notes that "access to self-referral gives victims more choice and control which is very important in the aftermath of a rape or sexual assault which will have deprived them of their human rights".

Currently self-referral is only available in two health board areas NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, through Archway, and NHS Tayside, through the Sexual Assault Referral Network. (In some cases this service is available to victims from other health board areas1.)

Child protection

As mentioned previously, the Bill would only make self-referral available to people aged 16 or older. The Explanatory Notes state that this does not prevent people under 16 years old accessing healthcare support ahead of police involvement.

The NSPCC in Scotland notes that a child legally becomes an adult when they turn 16, but statutory guidance which supports the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014, refers to children and young people up to the age of 18, which is in line with the approach taken by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC).

However, section 2(4) of the Age of Legal Capacity (Scotland) Act 1991, established that:

A person under the age of 16 years shall have legal capacity to consent on his own behalf to any surgical, medical or dental procedure or treatment where, in the opinion of a qualified medical practitioner attending him, he is capable of understanding the nature and possible consequences of the procedure or treatment.

In the Child Rights and Welfare Impact Assessment, the Scottish Government notes that:

The option of prescribing a lower or higher age cut off was rejected, since this option did not find favour with the [CMO taskforce's children and young people] Expert Group or with consultees. The Scottish Government considers that the best approach is to align the Bill with the general age of legal capacity (16) and the “age of consent” in the Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009.

The national child protection guidance is currently being reviewed by the Scottish Government.

In terms of disclosing information to the police, GMC guidance states:

You can disclose relevant information when this is in the public interest [...] If a child or young person is involved in abusive or seriously harmful sexual activity, you must protect them by sharing relevant information with appropriate people or agencies, such as the police or social services, quickly and professionally.

The NSPCC notes that, in Scotland, there is no legal requirement to report concerns about a child’s welfare. However, the Scottish Government's national guidance for child protection refers to "collective responsibilities" to protect children.

The UNCRC is an international human rights treaty that grants all children and young people (aged 17 and under) a comprehensive set of rights. The UK signed the convention on 19 April 1990, ratified it on 16 December 1991 and it came into force on 15 January 1992. The Scottish Government is currently developing legislation to incorporate the UNCRC into Scots Law.

The UNCRC has a number of relevant articles including:

Article 3: (best interests of the child) The best interests of the child must be a top priority in all decisions and actions that affect children.

Article 16: (right to privacy) Every child has the right to privacy. The law should protect the child’s private, family and home life, including protecting children from unlawful attacks that harm their reputation.

Article 19: (protection from violence, abuse and neglect) Governments must do all they can to ensure that children are protected from all forms of violence, abuse, neglect and bad treatment by their parents or anyone else who looks after them.

Article 24: (health and health services) Every child has the right to the best possible health. Governments must provide good quality health care, clean water, nutritious food, and a clean environment and education on health and well-being so that children can stay healthy. Richer countries must help poorer countries achieve this.

Article 34: (sexual exploitation) Governments must protect children from all forms of sexual abuse and exploitation.

Article 39: (recovery from trauma and reintegration) Children who have experienced neglect, abuse, exploitation, torture or who are victims of war must receive special support to help them recover their health, dignity, self-respect and social life.

The retention service

The retention service would enable the storage of evidence collected during a self-referred forensic medical examinationi. The Explanatory Notes state that the nature of storage will depend on the items being stored and does not include the analysis of samples or other information, as this would be carried out by the Scottish Police Authority, if and when the case is reported to Police Scotland.

The Bill proposes that people who have self-referred for a forensic medical examination would be able to request that any clothing or belongings that had been retained by the health board be returned. They would not be able to access other evidence, such as samples.

Where evidence is not transferred to the police, or destroyed at the request of the victim, it would be destroyed by the health board at the end of a retention period. The duration of retention is not specified in the Bill but would be set by Scottish Ministers in regulations (subject to affirmative procedure)1. It is intended that the self-referral subgroup will advise Ministers on the retention period and that the statutory period would be notified to victims as part of the information provided under section 4 of the Bill2.

Role of special health boards and co-operation

The Bill would give Scottish Ministers the power to confer functions on special health boardsi, NSSii and HIS. The Explanatory Notes give the example that NHS Education for Scotland could be required to provide education and training to healthcare professionals on aspects of the Bill which are not entirely exercised for health purposes1.

The Bill also seeks to require health boards to co-operate with each other and with the special health boards, NSS and HIS in planning and providing the examination and retention service with a view to ensuring adequate provision across Scotland and continuous improvement. It is intended that this will, amongst other things, allow for the continuation of cross-territorial working arrangements2.

Delegated powers

The Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee published its Stage 1 report on the Forensic Medical Services (Victims of Sexual Offences) (Scotland) Bill on 31 January 2020.

The Committee considered each of the delegated powers in the Bill and determined that it did not need to draw the attention of the Parliament to the delegated powers in the following provisions:

Section 8(1)(b) - Destruction of samples, information, etc.

Section 10 - Functions

Section 14 - Ancillary provision

Section 15 - Commencement

The Committee reported that it is content with the delegated powers provisions contained in the Bill.

Financial Memorandum

The Financial Memorandum (FM) which accompanies the Bill estimated additional service demand for forensic medical examinations arising from self-referrals.

Low demand = An additional 3 forensic medical examinations per 100,000 of the Scottish population. Equivalent to around 68 extra examinations each year.

Medium demand = An additional 3.6 forensic medical examinations per 100,000 of the Scottish population. Equivalent to around 81 extra examinations each year.

High demand = An additional 4 forensic medical examinations per 100,000 of the Scottish population. Equivalent to around 90 extra examinations each year.

Using these estimates of potential demand, the FM sets out the estimated costs of the Bill over five years. The table below shows estimated costs under the medium demand scenario.

| 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs to health boards | £267,163 | £267,961 | £268,772 | £269,717 | £270,667 | £1,344,280 |

| Costs to justice system | £860,000 | £1,120,000 | £1,120,000 | £1,250, 000 | £1,380,000 | £5,730,000 |

| Total costs | £1,127,163 | £1,387,961 | £1,388,772 | £1,519,717 | £1,650,667 | £7,074,280 |

The FM includes a number of caveats regarding the estimates. In relation to the calculations of additional demand it notes that:

It is not possible to predict the impact of a range of external factors on future demand. These might include a general increase in awareness of available services, changes in wider social norms, changes in crime rates, high profile cases in the media, other campaigns, etc. In addition, there is a hidden population of victims who are currently not known to services at all and we cannot predict how the Bill could impact on their willingness to come forward.

Costs to the Justice System. The FM notes that estimates of the financial impacts to the justice system are subject to significantly more uncertainty than estimates of the direct costs of providing additional examinations. The FM based estimations of costs on the assumption that 60% of self-referral cases will be reported to the police, and that 15 to 30% of reported crimes will result in criminal prosecutions. The costs to the justice system includes those to the Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service, the Scottish Legal Aid Board, the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service and the Scottish Prisons Service. Estimations of costs over five years vary between £3,070,000 (low demand scenario) and £8,390,000 (high demand scenario).

Costs to local authorities and the third sector. The FM states that there are no direct costs to local authorities resulting from the Bill. The FM also says that third sector organisations are expected to play an important part in raising awareness of self-referral, but that the costs to the third sector of supporting the implementation of the Bill will be modest.

Health and Sport Committee call for views

The Health and Sport Committee launched its call for views on the Bill on 6 December 2019 and it closed on 30 January 2020. The call for views asked five questions:

What are the key advantages and disadvantages of placing the examination of victims of sexual offences (and victims of harmful sexual behaviour by children) by health boards on a statutory basis?

What are the key benefits of providing forensic examination on a self-referral basis (whereby victims can undergo a forensic medical examination without first having reported the incident to the police)? What problems may arise from this process?

Are there any issues with the proposal to restrict self-referral to people over 16 years old?

Are there any issues with the health board storing and retaining evidence gathered during self-referred forensic examinations?

Do you have any other comments to make on the Bill?

Thirty three responses were received from organisations, including from disability organisations, women's rights groups, health boards, local authorities and integration authorities, Royal Colleges and rape crisis services. Four late submissions were also received. These have not been included in this paper.

Key issues raised in the Committee's call for views

The following section explores some of the key issues raised by the respondents in the Health and Sport Committee's call for written evidence.

The majority of respondents were in favour of the Bill. Submissions identified a number of benefits for victims. Health boards were seen as being best placed to carry out examinations and to signpost victims to follow up services and to enable holistic treatment. The proposals in the Bill were also seen by many as allowing better use of resources and as having public health benefits. Many respondents were of the opinion that the Bill would lead to a more consistent approach across Scotland, and the majority of respondents were in favour of self-referral.

Examination service

Many submissions commented on aspects of the examination service. The key issues raised in relation to the examination service included practicalities associated with the examination, such as the sex of the examiner, out of hours services and referrals. There was much discussion of issues around capacity, consent and services for children and young people. Supported decision making, advocacy and psychological support were also seen to be important considerations.

Sex of examiner

The sex of the examiner was raised as an issue that was very important to the victims of sexual abuse and rape. NHS Lanarkshire commented that the "patient’s choice of sex of forensic examiner must be guaranteed by this legislation"i.

This was expanded on by Rape Crisis Scotland who explained that:

The single most common complaint we hear from survivors of sexual crime about their experience of the forensic examination is lack of access to female doctors. Despite overwhelming evidence of a strong preference for female doctors to carry out intimate examinations following rape, in many areas of Scotland survivors continue to be examined by male doctors. There continues to be a lack of meaningful choice, with some survivors being told that if they wish a female doctor they will need to wait for a number of hours, meaning that they are faced with a ‘choice’ of an examination within a reasonable timescale with a male doctor, or waiting for hours without washing post rape in order to have a female doctor. This is in our view inhumane.

It believes that the provisions in the Victims and Witnesses (Scotland) Act 2014 have never been implemented, due to lack of availability of female doctors. Rape Crisis Scotland considers that "there has been a failure to prioritise the needs of survivors in this regard". It suggests:

For any legislation to be meaningful, the right to have a choice of gender of examiner would require at a minimum a male and female doctor to be available and on call at any one time. It is difficult to see the justification for this or how this could be resourced in areas where there is normally only one doctor on call. It would seem simpler, and more likely to meet survivors’ needs, to require health boards to always have a female examiner available, as this is what survivors of rape say they want and need.

Place of examination

Recommendation 5 of the HMICS report Strategic Overview of Provision of Forensic Medical Services to Victims of Sexual Crime was that:

Police Scotland should work with NHS Boards to urgently identify appropriate healthcare facilities for the forensic medical examination of victims of sexual crime. The use of police premises for the examination of victims should be phased out in favour of healthcare facilities as soon as is practicable.

Place of examination was raised in a number of submissions. Rape Crisis Scotland commented that:

The physical environment that forensic examinations take place in is important. Survivors tell us of undergoing examinations in environments which are cold (literally and figuratively) and which offer no sense of comfort at a very traumatic time. Many say they weren’t offered tea or hot drinks or food, despite being in the premises for many hours. As well as having a physical impact, the failure to offer food or drink communicated to them a lack of care for their wellbeing.

NHS Lanarkshire expressed the view that suitable premises are needed to allow age appropriate examination and interview. Children 1st also commented on this, saying that:

In our experience, surroundings that may be entirely suitable and appropriate for an adult may not be appropriate for children. This is, in practice, increasingly recognised, and a number of health boards have done a significant amount of work to make sure spaces used for work with children feel more child friendly. However, we are also aware that there have been situations where adults have felt uncomfortable having forensic medical examinations in surrounding that are too obviously designed to be child friendly.

Out of hours services

The need for services outwith core hours was raised by the Rape and Sexual Abuse Centre, Perth and Kinross and by Rape Crisis Scotland who commented that "many rape survivors experience significant delays in their forensic examination being organised. These delays can have a profound impact". The issue of delays in organising paediatric examinations was raised as a significant concern by Children 1st.

Referrals from other services

Pathways into forensic medical services from other services, such as sexual health services, general practice, community pharmacy and local hubs, were discussed in several submissions. Clackmannanshire and Stirling Child Protection Committee and Stirling Council noted that victims "may be in denial that they have been raped and may access other services in the first instance. They believe there should be a variety of entry points in a joined up system, such as help lines and referral from children and family services.

Edinburgh Rape Crisis Centre agreed that self-referral will need to be actively promoted by all relevant services as many survivors will not be aware of the possibility of self-referral.

Community Pharmacy Scotland highlighted the need for a recognised pathway for people who seek help at their pharmacy in the first instance. They note:

The removal of any barriers should hopefully allow those that require the service to self-refer safe in the knowledge that they can access the service without the need for police intervention initially, which could be daunting for some individuals. This allows health professionals (including community pharmacists) to inform individuals of what they may now expect when initially accessing these types of services following trauma.

The Law Society of Scotland raised the issue of training and notes that everyone involved in the process should be trained at the outset, especially those involved in provision of information.

Public information and awareness of services

A key issue in the written evidence related to how self-referral services would be publicised. The Rape and Sexual Abuse Centre, Perth and Kinross commented that "a lot of awareness raising will need to be carried out to ensure that people know about self-referral".

The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) suggested that:

The Scottish Government must also take action to increase awareness of these changes amongst both the public and professionals. The introduction of self-referral will only benefit victims if they, or someone they confide in, are aware of this option. In addition to increasing awareness of the changes provided for in the Bill, the Scottish Government and health boards must ensure that information about these services is available locally so that an individual is able to easily find out where to go to access a forensic medical examination.

It was also suggested that information should be made available in a number of accessible formats. Deaf Scotland highlighted the need for good quality information in a variety of languages and accessible methods, including British Sign Language, plain English, Braille and easy read. The South Lanarkshire Gender-Based Violence partnership discussed the merit of easy read information on the HIS standards and on the taking and retaining samples.

Capacity and consent to be examined

The issue of consent was discussed with a particular focus on the needs of people with additional support needs. The Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland (RCPsych in Scotland) commented that "within the provisions, consideration must be given to protection of rights of all groups of people including children, individuals with additional support needs, older adults, and individuals with mental disorders and intellectual disability".

The Law Society of Scotland stated that equality considerations are paramount. Saying that:

There is clear case law from the European Court on Human Rights that failure to give full protection to people with mental and intellectual disabilities is a breach of their human rights. That position is reinforced with the obligations undertaken by the UK under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Person with Disabilities. There is a need to consider the issue of consent and legal capacity. We had suggested previously that consideration may require to be given when it is necessary to decide on someone’s behalf. If so, is that decision being made in that person’s best interests?

There is also a need to acknowledge the role too of the Appropriate Adults whose responsibility it is to support vulnerable persons in the police station who may well be involved in having forensic medical examinations carried out.

A Disabled People's Organisation highlighted its concerns that people with learning disabilities will not be treated equally due to potential conflicts with other laws:

People with a learning disability are in a different position to most other people who might be accessing this service. Because many of us can be legally seen as 'adults at risk' our access to such services may not be as confidential as it would be for most people. Professionals often (and rightly) have a duty of care to report their concerns about our well-being. We think this is the right thing to do when a person is seriously at risk but we know that it also puts off some women accessing services because they fear that if Social Work gets involved, their 'capacity' will be challenged and they will be put under Guardianship.

NHS Lanarkshire suggested that links with Mental Health Officers and assessments of capacity undertaken under the Adults with Incapacity Act need to be clearly explained.

The South Lanarkshire Gender-Based Violence partnership noted that interpreting services must be offered to victims. However, it raised confidentiality concerns when the translator may be known to the victim. This concern was also highlighted by NHS Lanarkshire.

The Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) and Children 1st both raised the issue of people being given information when in a distressed state. The ICO discussed whether it would be helpful for the legislation to require practitioners to provide information in a manner appropriate to the circumstances, recognising that the individual undergoing the examination will have undergone trauma and may not be best placed to take in that information. Children 1st commented that informed consent must be central to any legislative framework and that this "should reflect the shock and distress that those subject to sexual violence are likely to feel, and take this into account in the provision of information".

Children and young people

There was much discussion in the written submissions about forensic medical services for children and young people. Children 1st highlighted the principle, as enshrined in Getting It Right For Every Child (GIRFEC), that the best interests of the child must be the priority in all decisions and actions that affect children.

The NSPCC considered the Bill to be a missed opportunity for driving improvements for an integrated response to children following sexual abuse. The NSPCC also considered that the Bill will not lead to much needed improvement in the health response to children experiencing sexual abuse. NSPCC believed that there needs to be clearer and stronger legal obligations in place to drive the development of an integrated, multi-agency response to children.

We must create a system in which physical health needs are considered alongside emotional and mental health and recovery needs, and which helps address the chronic lack of provision of therapeutic recovery services for children following abuse.

Children 1st noted its "disappointment" that special provisions for children and young people have not been included in the Bill. It raised the following concerns in its submission:

The provision of forensic medical services for children who are victims of offences other than rape and sexual assault.

That the distinct needs of children and young people have not been fully considered.

The need for alignment with child protection processes.

Issues around the implementation of the Bill.

How the Bill links to the Barnahus approach including the potential for unintended consequences. It noted that whereas the Barnahus approach seeks to provide holistic support, including medical examinations, to all child victims of violence and abuse. This Bill creates a duty only for medical examinations and only for child victims of sexual offences).

In relation to the Clinical Pathway for Children and Young People, Children 1st expressed concerns about the proposals for the pathway and the way in which it potentially cuts across the ongoing work on a Barnahus approach for child victims and witnesses. They go on to suggest that "it is important for the Committee to consider how it can ensure that an integrated, rights-based, child-centred approach required for effective implementation of this legislation can be delivered through the Pathway".

The South Lanarkshire Gender-Based Violence partnership suggested exploring the feasibility of regional Barnhaus-type models to provide age-appropriate service cover for whole of Scotland. They note that smaller local authorities may not be able to introduce their own Barnhaus.

Police Scotland were in support of "multidisciplinary and interagency services co-located in an environment that this trauma informed; child friendly and safe for children who may have been abused or neglected".

One respondent raised concerns regarding the availability of services in rural and island health boards. They commented that:

Under 16's still travel to the mainland on public transport accompanied by family members, social worker and police officers all known to the community. Friends of families approach them enquiring where they are going assuming they must be attending a family holiday or some other positive trip off island. Parents have reported that children are exhausted by the lengthy travel arrangements and waiting to be seen by the many professionals involved. So much so that they regret having disclosed.

Age of the child

Some respondents highlighted the differences between the definition of child in the UN Rights of the Child (UNCRC), which is 18, and the provisions in this Bill which apply to people under the age of 16. The Angus Violence Against Women Partnership notes that the definition of child is extended to 18 in terms of triggering a child protection response.

RCPsych in Scotland commented that "although the age of 16 is in line with the age of consent, there are some issues to be considered regarding including young people aged 16 to 18 within the bracket for self-referral".

NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde and Glasgow Health and Social Care Partnership also suggest that clarification is needed regarding the position of looked after and accommodated children between the ages of 16 and 24 for whom local authorities/public bodies have parenting responsibilities.

The Law Society of Scotland sought:

Clarification [..] as to the practical significance of paragraph 30 of the Bill’s Policy Memorandum. Those under 16 are excluded from the Bill’s self-referral provisions so that a child is unable to access self-referral on account of being under 16. If it is considered by the police that a forensic examination should be done, such a child may be able to consent to such examinations themselves if they are judged to be sufficiently mature in terms of the Age of Legal Capacity (Scotland) Act 1991. That allows medical consent decisions to be made if they are considered appropriately mature in the opinion of a medical practitioner.

The National Guidance for Child Protection in Scotland 2014 states that "where the child is of sufficient age and understanding, they may refuse consent to a medical examination or treatment whether or not a Child Assessment Order is made".

Child protection and access to self-referral

Some submissions reflected on child protection provision across Scotland. TRCPsych in Scotland commented that "within our own health boards there is an unacceptable variation in the provision of resource for child protection".

In relation to self-referral, HIS noted that:

It is key that the Bill is aligned to current child protection legislation, guidance and best practice both in Scotland and internationally to ensure that children and young people are supported to access services. The age of self-referral should reflect a balance in policy between empowerment, choice, and a child’s right to protection and safeguarding.

HIS cited research from St Mary’s Sexual Assault Referral Centre in Manchester (SARC) which found that peer-on-peer sexual abuse (by young people under 18) was high among young people who attended for a forensic medical examination. They reported that the 12 to 17 age group were the most likely to self-refer, with older children more likely to engage directly with statutory authorities, including the police. HIS also noted its understanding that the Havens in London also accepts self-referrals from young people over the age of 13, and provides support from a specialist young person’s Independent Sexual Violence Advisor (ISVA), whose role it is to empower young people to report what has happened to them to the police.

It went on to comment:

We would welcome further evaluation of the benefits and challenges of the existing English SARC model. This may include evidence on the proportion of self-referrals of young people aged 16 and under who make the choice to report to the police after engagement from young people’s specialists.

Many respondents believed that self-referral should not exclude children and young people under the age of 16 - but that young people should be made aware of the child protection procedures that would be triggered following a referral.

VSS considered that it would be detrimental to restrict under 16s from the self-referral process:

Due to their age and the potential nature of the harmful sexual behaviour, especially in instances that may involve a family member, they are likely to feel less comfortable seeking a forensic medical examination through the police and prefer an alternative setting for their initial steps towards seeking the involvement of criminal justice agencies. In such instances, it should be made clear to the victim, that as they are under the age of 16, it will be necessary to pass on evidence gathered as a result of the examination to the police.

One submission from a victim of abuse commented that "any child under the age of 16 should be allowed to self-report".

Some respondents believe that the age limit for self-referral should be lowered to 13. The Rape and Sexual Abuse Centre, Perth and Kinross reported:

Internal statistics tell us that in the last 5 years, 20% of survivors accessing our services were age between 13-15 when the abuse started. A further 27% were under the age of 13. Knowing what we do about prevalence rates and seeing our service face increasing demand for young people's support, we would advocate for the self-referral to extend to 13+.

The RCN also disagreed with the proposal to restrict access to self-referral services to those over 16, stating that:

Enabling a child under 16 to self-refer provides another route for that child to seek help and receive trauma-informed care and support immediately. While the policy memorandum states that this proposal does not preclude a young person from seeking access to healthcare ahead of a police report, enabling them to self-refer for a forensic medical examination may encourage more young people to come forward....If people under 16 were able to self-refer then the framework would need to be different to the adult framework, to reflect that fact that it would remain the case that health professionals would still be duty bound to report what has happened to the relevant authorities in line with existing child protection guidance and clinical practice. Yet despite this important difference, we are of the view that enabling victims under 16 to self-refer without first making a police report would have many of the same benefits as introducing this right for adults. They would be able to seek help in a person-centred, trauma-informed environment and have their healthcare needs met. Healthcare professionals would be required to involve the police but the young person would receive support throughout this process. We therefore believe that restricting access to people over 16 would be a mistake and a missed opportunity.

In relation to the duty of professionals to report their concerns, the General Medical Council (GMC) commented:

Doctors (and other health professionals) are under a duty to share information with appropriate agencies if they are concerned that a child or young person is at risk, unless it is not in their best interests to do so. However, it’s not clear to us why this would preclude self-referral. It is noted that young people would be able to seek healthcare services without (or before) reporting to the police, but it’s not clear why they would not be able to access the self-referral to forensic services as well, if they had sufficient maturity to do this, as long as it was clear that information may need to be passed on (which would also be the case if they sought medical care that was not a forensic examination).

Some respondents, while supporting proposals in the Bill that would only allow forensic medical examination of people under 16 with prior police involvement, considered that young people should be provided with information about what they should do should they wish to make a disclosure of rape or sexual assault and what would happen following disclosure. Including the triggering of child protection procedures and police involvement. They suggest that, without this, the promotion of the self-referral route for those aged over 16 may unintentionally act as a barrier to younger vulnerable victims (NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde and Glasgow Health and Social Care Partnership and Edinburgh Rape Crisis Centre).

Children and young people alleged to have perpetrated sexual assault and abuse

The NSPCC highlighted that the examination of children and young people alleged to have perpetrated sexual assault and abuse is not included in the Bill. The HMICS Strategic Overview of Provision of Forensic Medical Services to Victims of Sexual Crime found that many children suspected of perpetrating sexual offences are subject to forensic examination in police custody. HMICS recommended that:

Police Scotland should work with NHS Scotland to ensure suspected perpetrators of sexual abuse who are under 16 years old are not forensically examined within police custody facilities. The Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2016 defines a child as being a person under the age of 18 and consideration should be given to how this affects the treatment of child suspects in the context of forensic medical examinations

The NSPCC commented that it would support the provisions in the Bill being extended to cover the forensic examination of all children and a statutory basis for the provision of therapeutic interventions to address children’s harmful sexual behaviour.

Victim Support Scotland (VSS) commented on the support available to child perpetrators and sought assurances that they would be able to access the support services they require.

Psychological support

Many submissions reflected on the importance of psychological support for victims. NHS Lanarkshire noted that:

The legislation should give victims the right to timely psychological, aftercare/ through care and advocacy services, or services for addictions, mental health issues or self-harm. This access should feature in the legislation for all. This support should be person-centred, and available as and when required for the individual, which may have a subsequent advantage in reducing reliance on other services such as Emergency Departments, mental health, CAMHS etc at a later date.

RCPsych in Scotland believe that:

Mental health support should be at hand for victims who are witnesses at all stages of the criminal justice process. Health Board and Integrated Joint Boards (IJBs) should have a duty to provide appropriate mental health support for victims after conclusion of criminal proceedings and have a duty to provide evidence based accessible services for those who have experienced trauma.

The NSPCC raised the specific issue of the needs of children and young people. They believe:

A child’s emotional and mental health needs, and their need for therapeutic recovery following sexual abuse, do not take centre stage in Scotland. There are no mandates around meeting the emotional or mental health and recovery needs of children following sexual abuse. It is not clear whether the provision of such support is the responsibility of health or social work, and vulnerable children can fall down the gap between the two.

The NSPCC reflected on the provisions in section 5 of the Bill "Health care needs" and considered that this provision, as it is intrinsically linked to forensic medical examination, risks creating inequality as it will only apply to people who undergo forensic medical examination. It notes that the vast majority of children who experience sexual abuse do not come to the attention of statutory services within the forensic capture window and do not undergo a forensic examination.

Supported decision making and advocacy

Police Scotland raised concerns that healthcare professionals carrying out forensic medical examinations may not be best placed to provide information to inform decision making about police referral and support potential engagement with the criminal justice system.

Rape and Sexual Abuse Service Highland noted the importance of advocacy and support independent of the health board and Police Scotland. It reflects that:

Survivors have often voiced to us that having an independent advocate, throughout the process who works in a person centred and trauma informed way as our support and advocacy workers do has been invaluable and allowed the survivor to feel safe whilst their options are explained and not feel pressured to make a decision about whether to report or not.

Edinburgh Rape Crisis Centre also highlighted the importance of advocacy.

It is our experience that survivors often feel better able to report the crime if they have an advocate supporting them. They are also much better able to deal with the forensic medical examination in the immediate aftermath of the trauma if they have an independent advocate with them, explaining the process and being close by to support them. Advocacy and support services that are independent of both the health boards and the police should be used to provide this important service in the aftermath of a sexual offence. The network of Rape Crisis Centres across Scotland is ideally positioned, both in terms of experience and expertise, and independence from public services, to provide these services in partnership with the health and police services.

A Rape and Sexual Assault Service stated that victims were often worried about who would see photographs from the examination, where they would be stored and how they would be used in court proceedings.

The issue of supportive decision making for vulnerable adults was also raised in written evidence. A number of respondents suggested that the Bill should have a clear definition of vulnerable as many people presenting for examination may have vulnerabilities because of age, ability, addiction, previous trauma and poor mental health.

Retention service

The key issues raised by respondents in relation to the retention service included data protection, storage, timescales for retention and maintaining the chain of evidence.

The RCN highlighted the importance of ensuring that the "correct governance arrangements, high standards and robust inspection regimes are in place to ensure that any evidence collected during forensic medical examinations under the self-referral model support any future court proceedings."

It went on to note:

It is vital that there are very clear policies regulating the collection and retention of evidence, as well as a robust inspection regime. Such policies will need to address ethical as well as practical governance issues and must ensure that a consistent, evidence-based approach is followed. There will also be cost implications for boards to ensure that samples are appropriately and securely transported and stored.

In its submission, HIS recommended that further guidance on facilities, storage duration, access, and ownership of data is developed and issued to all NHS boards. It believed that this would help to ensure that there are robust and appropriate governance mechanisms in line with the HIS 2017 standards.

The Law Society of Scotland noted the importance of distinguishing in the legislation between the samples and the data obtained from them.

Chain of evidence

Concerns were raised regarding the admissibility of evidence collected during self-referrals. Police Scotland commented that the appropriate storage and retention of samples gained during a self-referral are crucial in ensuring that, in the event of their subsequent examination and results being used in any criminal (or civil) proceedings, there is no risk of a challenge due to improper storage/retention, or issues with continuity of evidence.

The Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service also supported this view saying that:

It is imperative that the method and arrangements for storage of this evidence is in accordance with the criminal rules of evidence to ensure the evidence is admissible in any future prosecution.....there requires to be a national storage standard applied across all NHS Boards to ensure consistency in storage and compliance with evidential considerations.

The Scottish Children's Reporter Administration called for guidance in relation to the storage and retention of evidence to be laid out in statute which clearly sets out when evidence requires to be retained for use within the children’s hearing or criminal justice systems.

Police Scotland commented that the storage process must be sufficiently robust to protect the integrity of the evidence chain and to comply with current Lord Advocate guidelines.

The Law Society of Scotland highlighted the importance of a robust audit trail to ensure that the collection and storage of evidence complies with the rules of criminal evidence.

Evidence

Clackmannanshire and Stirling Child Protection Committee and Stirling Council highlighted issues with the limitations of storage space within health care settings.

Police Scotland believe that the evidence obtained by health boards should be restricted to the taking of forensic samples and not the securing and retention of any other articles, which may or may not have any evidential value.

It is Police Scotland's view is, given the generality of Section 7(2), in particular '…an item worn or otherwise present during the incident…' could include a vast range of items such as bedding, sofa cushion, rug, cup/glass etc. etc. In addition to Health Boards not being equipped to retain such articles, there is the real possibility of well-intended 'mission creep' with Forensic Physicians and other healthcare professionals involved in forensic medical examinations assuming the role of an investigating officer or productions officer.

NHS Lanarkshire suggested that information was needed on what should be stored and on the conditions of storage.

Timescales for retention

Many respondents called for consideration to be given to the retention period for evidence collected during a self-referred forensic medical examination.

A number of respondents commented that further clarity is required on the storage of samples and the length of time samples should be retained in order to ensure standards are consistent across the country.

The ICO strongly recommended that retention periods are evidence informed and reviewed regularly. It noted that the Scottish Government should consult on retention periods with existing self-referral services, victims groups and victims.They conclude that decisions on retention will need to balance the risks associated with the sample being stored too long with the risks of it being destroyed too early.

VSS sought assurances that victims will be notified in good time that their evidence is due to be destroyed, as well as details of any process required to overrule such a decision by a health board. It believed that the decision on how the evidence is used and when it should be destroyed should ultimately lie with the victim.

The Law Society of Scotland reflected that:

Certain samples may have a shelf life and there is a need to ensure that they can be interrogated when required. Given the ongoing developments in forensic science, a sample in the future may be able to offer information which cannot be obtained at present. Retained samples could then be used to support a future criminal prosecution. These interests need to be balanced between the rights of the State to retain and those of the victim and their privacy in cases where the sample were to reveal personal information which was not relevant to the case in question.

Time scales for retention for such samples are tricky to decide. Cognisance should be taken of experience gained from the recent increase in reporting of such offences and especially in relation to historic sexual offence cases just how long these samples should be retained.

VSS say that there is no detail on whether evidence will be retained for purposes of a potential trial or maintained beyond an initial trial in case there an appeal, or further trials of the same perpetrator.

Children 1st consider that in relation to child victims evidence should be held for a significant period to enable a child to come back to it in future years if they choose to revisit a disclosure. Commenting that disclosure of sexual abuse can often happen over a period of time, sometimes years apart, forensic examination undertaken at one time should be considered as potentially ‘evidentially significant’ despite there being a lack of evidence based on the examination for this to proceed at that particular time.

Data protection

The issue of personal data was discussed in many submissions. The South Lanarkshire Gender-Based Violence Partnership noted that the Bill needs to consider what personal data will be stored, clarify who own samples, including when this transfers and victims consent requirements. Edinburgh Rape Crisis Centre also believes that more clarity is needed on storage of samples, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) issues, confidentiality and anonymity.

The RCPsych in Scotland commented that:

Given the very personal and sensitive nature of the data and information being handled, dignity, respect, privacy and data protection should form the integral part of the service standard and design being offered.

The ICO advised that health boards should consider risks with the processing of personal data gathered during a forensic medical examination in a systematic way via a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) and identify appropriate safeguards and measures to mitigate these. They note that data protection law identifies that children’s data needs particular protection. The DPIA should specifically identify and mitigate the risks associated with processing the data of victims aged under 18. Particular attention should be paid to ensure that processing is fair and that relevant privacy information is clear.

Children 1st also raised specific issues regarding data protection in relation to children and young people.

Children 1st have experience of a number of very difficult and complex situations where parents have sought to conduct a Subject Access Request to see their child’s records, and any information held about them in the records. This has included a parent seeking access to the full medical records of a forensic examination which was undertaken due to report of potential harm by that parent. Because these records were no longer part of an ongoing Police inquiry or live justice processes, the records were shown in full on the ground that this was what the legislation required. This is highly concerning in relation to the impact this has on the right to privacy of children who are forensically examined; as a parents ability to request full access their child’s records means that whilst measures can be taken to securely hold the sensitive data gathered under forensic examination, for those cases where there is no ongoing or open criminal investigation (which is a significant proportion of cases, if not majority) a SAR request could end up with the sensitive data being provided to the requesting parent, even in cases where a child would not wish this to happen.

Children 1st's submission goes on to describe a situation where medical records from a forensic medical examination, that do not show signs of physical trauma, can be used by the parent for whom there is a child protection concern as proof that the disclosure was false. However, it believes that, for many children a lack of medical ‘proof’ of abuse can in fact be entirely consistent with the nature of the sexual abuse they have disclosed, as not all sexual abuse results in physical evidence or trauma. It considers that it is particularly important that the forensic examination data is recognised as being only part of the ‘disclosure and story’ of a child’s abuse and that the potentially highly sensitive medical data needs to be covered by the data protection measures and guidance which is designed with these kinds of contexts and situations for children in mind.

Resources

The majority of responses reflected on the potential resource implications of the Bill. Edinburgh Rape Crisis Centre commented that:

The statutory provision of forensic medical examinations by health boards potentially has significant resource implications. Additional resources will be required to meet the personnel, building, equipment and care associated with this duty, and these resources must be forthcoming from the Scottish Government. The benefits, however, will vastly outweigh the costs.

Cost to health boards

Many respondents raised concerns about the increased costs to health boards implementing the provisions in the Bill. South Lanarkshire Gender-Based Violence Partnership commented that there needs to be consideration of the financial and practical implications of any new legal duties on health boards and adequate resource provision by Scottish Government commensurate with new duties.

A number of submissions raised concerns about long-term funding associated with implementing a specific statutory duty. NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde (NHSGGC) and Glasgow Health and Social Care Partnership believe that there will be financial disadvantages for health boards:

Placing the forensic examination of victims of sexual offences by Health Boards on a statutory basis without on-going provision of additional resources to meet the high standards of personnel, building, equipment and care associated with this duty will be financially challenging for Health Boards.......whilst the Scottish Government is providing additional short term funding to enhance existing NHSGGC FME services from April 2021 NHSGGC anticipates meeting additional costs beyond that date will necessitate reducing resources for other services. This reduction in resources for other services will be coincide with increased demand of sexual violence survivors on mental health and alcohol and recovery services and likely lead to detriment to other service users who have no legal entitlement to services

NHS Lanarkshire echoed these concerns:

Despite recent fixed-term government funding, health boards will require to be adequately funded in the longer term if they are to meet the duties and responsibilities which will be placed on them, so that nationwide standards can be maintained and to minimise risk of litigation against health boards occurring if lack of resources prevents them meeting standards and duties required. There are likely to be significant on-going resource implications for Boards if they are to adequately meet the HIS FME standards.

NHS Lanarkshire also raised the possibility that rural communities would be likely to require additional investment to maintain proper standards of training, consumables and cleaning standards, as they will be less used that an urban facility.

Workforce

The importance of an appropriately trained workforce to meet demand was also raised. The RCN noted that:

Ensuring that forensic medical examinations are available locally in a timely manner will require an increase in the workforce, particularly if these changes result in an increase in demand for these services. Future workforce planning will be central to the success of the self-referral model.

NHS Lanarkshire observed that there would be increased costs in the core workforce, including medical, nursing and other associated staffing. It also highlighted the importance of sustainable and ongoing training and development for the workforce and the need for psychological support for staff.

In relation to the examination of children, Children 1st highlighted a shortage of paediatricians trained to carry out forensic medical examinations. They reflected on the HMICS report that found that several areas reported shortages in paediatricians and difficulties in gaining and maintaining experience due to low numbers of examinations. They commented that shortages in paediatrician availability can result in lengthy journeys and delays. They reported examples of where children have had to travel over 100 miles for an examination.

Finance and Constitution Committee call for views

The Finance and Constitution Committee received four written submissions on the Bill. These focused on lack of additional funding in some areas and post 2021.