Scottish Budget 2020-21

This briefing summarises the Scottish Government's spending and tax plans for 2020-21. More detailed presentation of the budget figures can be found in our Budget spreadsheets. Infographics created by Andrew Aiton, Kayleigh Finnigan and Laura Gilman.

Executive Summary

This year's Scottish Budget is being published later than normal and in advance of the UK Government’s Budget, which is scheduled for next month. The later than normal publication has implications for the time available for parliamentary scrutiny of the Scottish Government’s proposals. Preceding the UK Government’s Budget also means that the total Scottish spending envelope for 2020-21 is still uncertain.

Although the UK has now left the EU, the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) judge that with UK-EU trade terms yet to be determined, "Brexit remains a risk to continued economic growth." The SFC's economic growth forecasts point to a continuing period of subdued economic growth and a downgrading of already weak productivity growth.

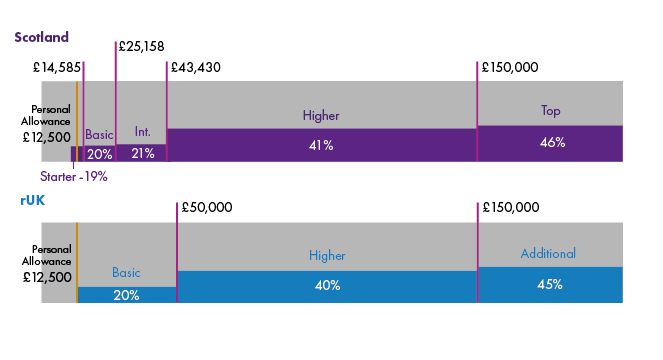

The Government's income tax proposals mean that all Scottish taxpayers will pay less income tax in 2020-21 than 2019-20. However, these differences are small - 36p per week for those earning less than £24,000 per year rising to £2.50 per year for higher earners.

Compared with current rates and bands for taxpayers in the rest of the UK (rUK), those earning less than £27,000 will pay slightly less (around £21 per year). Those earning more than £27,000 will pay more tax in Scotland than they would in rUK. According to the Scottish Government, this comprises 44% of taxpayers. The differential is in excess of £1,500 per annum for those earning over £50,000.

The Scottish Government's decision not to replicate rUK tax policy also means that tax receipts are forecast to be around £650 million higher than would otherwise be the case (before accounting for any behavioural responses). However, these higher tax revenues are forecast to be almost entirely offset by the deduction to the Scottish budget via the block grant adjustment (BGA). SFC forecasts estimate that this £650 million differential will only generate £46 million more than is deducted by the BGA. So, rather than generating an additional £650 million for the Scottish budget, the different income tax policy is only just managing to offset the BGA.

The Scottish Budget also faces a downward reconciliation of £207 million in 2020-21, £204 million of which arises from income tax receipts being different to the level forecast when the 2017-18 budget was set. The Scottish Government plans to manage this downward reconciliation by using its Resource Borrowing powers for the first time.

The income tax reconciliation outlook is looking more gloomy for subsequent years. Latest SFC forecasts and Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) BGA forecasts (from March 2019) for 2018-19 point to a negative reconciliation of £555 million to be made to the 2021-22 Budget and a reduction of £211 million in the 2022-23 Budget from latest 2019-20 outturn forecast.

On the spending side, Health is again the clear budgetary priority of the Scottish Government. The briefing considers some of the performance outcome information in this key policy area and notes that in Health (and also Education) there has been no improvement in performance over the most recent reporting period. The Health National Outcome in the National Performance Framework (NPF) is underpinned by a total of nine indicators. Despite large real terms Health spending increases in recent years, none of these indicators show any improvement in performance over the most recent period. In the Healthy life expectancy indicator, there is in fact a worsening of performance between 2014-16 and 2016-18.

In recent years, local government has been the focus of much parliamentary debate. As ever, there are a wide range of interpretations that can be made of the local government numbers. This year's overall settlement is more generous - on the resource side, the "discretionary" element of the budget is essentially flat in real terms, and once ring fenced grants are included it shows a real terms increase of 1.6% (or £159 million). However, there is still a debate about how much of the "discretionary" budget is in fact fully under the control of local government, and how much is allocated to Scottish Government priorities. COSLA states that “the reality behind this figure unfortunately is quite different” and that in their view there was “a cut to Local Government core budgets of £95 million.”

The Budget for 2020-21 contains a big increase in the Social Security budget which rises to £3.7 billion, due to the transfer of financial responsibility of £3.2 billion in social security payments.

Although the SFC forecasts and the Social Security provisional BGA are forecast to broadly match in 2020-21, the SFC warns that future years are less likely to be so closely aligned as policy differences between Scotland and rUK begin to emerge.

Much pre-budget coverage centred on the Budget being a response to the recently declared climate emergency. The Carbon Assessment published alongside the budget provides a tool for parliamentary scrutiny. It finds that the Rural Economy budget has by far the highest intensity of carbon emissions (measured as greenhouse gas emissions per £ of spend). Despite representing 1.5% of Scottish Government expenditure, this portfolio accounts for 13% of carbon emissions.

Future funding for infrastructure to support new rail routes, bus services, electric vehicles, walking and cycling remain dwarfed by the commitment to invest £6 billion over the next 10 years in dualling the A9 and A96 trunk roads, alongside other trunk road improvement projects.

This significant trunk road investment appears at odds with the Infrastructure Commission’s recommendations that no net additional capacity be added to the road network and that action needs to be taken to manage demand for road transport.

Context for Budget 2020-21

Scottish Budget 2020-211 was published on 6 February 2020 and presents the Scottish Government's draft spending and tax plans for 2020-21. With the document being published later than normal, there will now be a truncated period of parliamentary scrutiny and political negotiation as the Government seeks parliamentary support for its tax proposals and Budget Bill in advance of the new financial year. A recent SPICe blog article set out the detail of the process for this year, and a previous SPICe briefing described the new budget process approach in detail.

The Budget incorporates devolved tax forecasts undertaken by the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC). As well as producing point estimates for each of the devolved taxes (including non-domestic rates income (NDRI)) for the next five years, the SFC is also tasked with producing forecasts for Scottish economic growth and spending forecasts for the newly devolved social security areas. The SFC's forecasts can be found in Scotland’s Economic and Fiscal Forecasts.2

Budget 2020-21 comes against the backdrop of the UK’s recent departure from the European Union (EU). The SFC’s judgement is that this does not end the economic uncertainty for the coming year, as the trade terms on which the UK will leave the EU have yet to be determined.

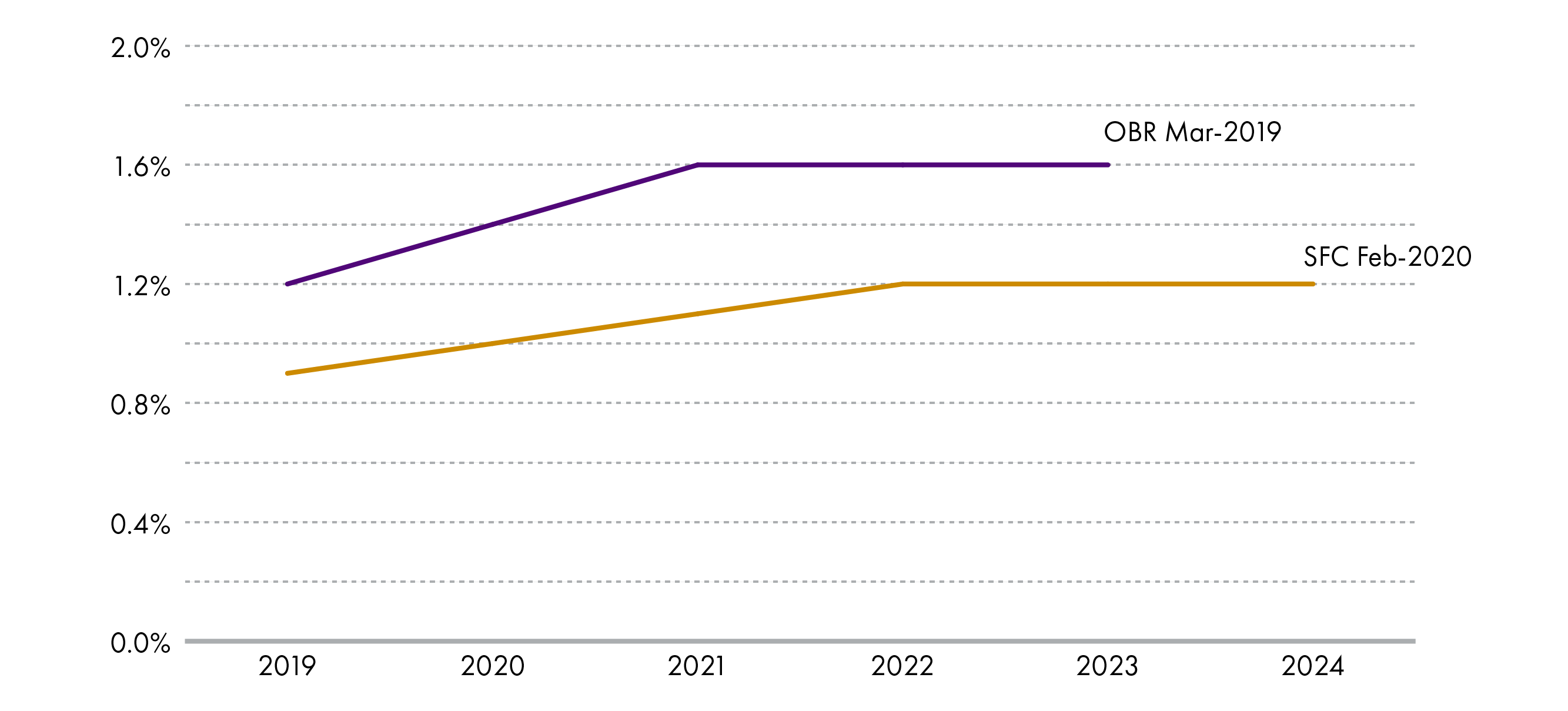

As such, the SFC has continued to forecast relatively subdued economic growth of 1.0% in 2020, 1.1% in 2021, and 1.2% in the subsequent three years.

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scottish Fiscal Commission | 0.9% | 1.0% | 1.1% | 1.2% | 1.2% |

| Fraser of Allander3 | 0.9% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.4% | |

| Ernst and Young | 1.0% | 1.4% | 1.5% | 1.7% | 1.8% |

| PWC4 | 1.6% | 1.3% |

Like the SFC for Scotland, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) is mandated to produce economic forecasts for the UK. The latest OBR forecasts for the UK will be updated next month alongside the UK Budget. The most recently available figures from March 2019 are presented in table 2 below alongside more recent forecasts from other organisations, including the Bank of England.

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OBR (March 2019)5 | 1.2% | 1.4% | 1.6% | 1.6% | 1.6% |

| Bank of England (January 2020) | 1.3% | 0.75 - 1.25% | 1.5 - 1.75% | 1.75 - 2.0% | |

| National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR)6 | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.6% | 1.6% | 1.8% |

| IFS (October 2019)7 | 1.1% | 1.0% | 1.3% | 1.5% | 1.4% |

| EY (November 2019)8 | 1.3% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 1.7% | 1.8% |

Overall spending

Table 1.02 of the Budget document presents HM Treasury's Budget Control Limits for the Scottish budget for 2020-21 and previous years in cash terms. This shows that the total budget will grow in cash terms by 14.4% in 2020-21 (12.4% in real terms). This large increase reflects the devolution of Social Security spending responsibility as well as a new budget line for Farm payments (which were previously EU income). With both of these areas stripped out, the growth in the Scottish budget is 4.9% in cash terms and 3.0% in real terms . These increases include £207 million in Resource borrowing and £450 million in Capital borrowing.

As is discussed in Box 1 below, for a number of reasons the figures in table 1.02 of the Budget differ to the totals actually allocated amongst portfolios in the document - Annex A of the Budget provides a reconciliation. The next section of the briefing looks at the total allocations for Resource, Capital and annually managed expenditure (AME) and how these are distributed across portfolios.

As mentioned, the Scottish Government intend to use annual Resource borrowing of £207 million and Capital borrowing of £450 million in 2020-21. This will need to be repaid in subsequent years. Resource borrowing needs to be paid over 3-5 years and Capital borrowing has a longer repayment term. The SFC state that the 2020-21 Capital borrowing will be repaid over 25 years at an assumed 1% interest rate. The Resource borrowing will be repaid over 5 years, but the interest rate payable is not stated.

Many of the numbers in this briefing are adjusted for inflation (presented in 'real terms'/ 2019-20 prices) and the deflator used is the latest Treasury deflator from January 20201.

Box 1: The reconciliation of available funding with spending plans

The numbers presented in table 1.02 differ to the total amounts allocated by the Scottish Government in the Budget 2020-21 document, due to various changes agreed between the Scottish and UK Governments. Annex A provides a reconciliation of the available funding (table A.03) to the proposed spending plans. There are a number of reasons for the differences which are summarised below:

The 2019-20 baseline numbers in the spending plans reflect the plans as at Budget Bill 2019-20 for that year to show a like-for-like comparison against 2020-21 plans.

As such, the budget figures in table 1.02 include additional Barnett consequentials for 2018-19 and 2019-20 from UK fiscal events since the relevant Budget Bill, whereas the spending plans do not.

Spending plans are underpinned by anticipated underspend carried forward from the prior year through the Scotland Reserve.

Machinery of Government changes, which relate to the transfer of responsibility from the UK to Scottish Government are not reflected in table 1.02, but are included in the portfolio spending plans.

There are some anticipated budget transfers for Scotland Act 2016 implementation and administration, that are not reflected in table 1.02 but are included in the spending plans.

Non-cash allocations are often more than required, and therefore not allocated to portfolios in spending plans and subsequently returned to HM Treasury.

£62 million was raised from freezing the Higher Rate Income Tax threshold in 2018-19 during passage of the Budget Bill. This is shown in the spending plans but not table 1.02.

In 2018-19, £50 million in accumulated revenues for the Queen's and Lord Treasurer's Remembrancer (QLTR) is shown in the spending plans but not table 1.02. £5 million is the estimated receipt in each of 2019-20 and 2020-21.

Budget allocations

Total allocations

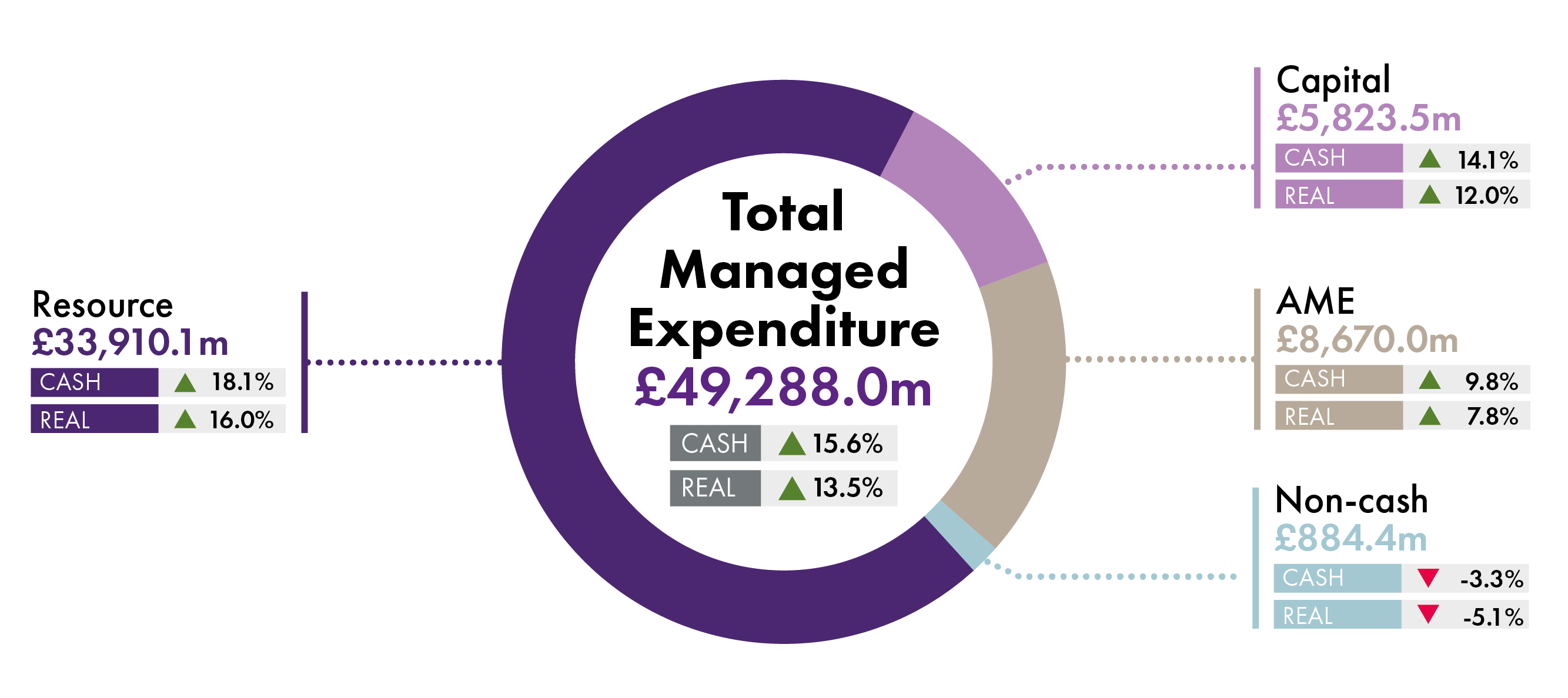

Total Managed Expenditure (TME) comprises Fiscal Resource, non-cash Resource, Capital and Annually Managed Expenditure (AME). TME in 2019-20 is £49,288 million. Figure 1 shows how this is allocated. As explained in Box 1 above, these figures differ to the HM Treasury Budget Control limits presented in table 1.02 of the Budget document. Fiscal Resource (which covers day-to-day expenditure) and Capital (covering infrastructure expenditure) are the elements of the budget over which the Scottish Government has discretion. AME is expenditure which is difficult to predict precisely, but where there is a commitment to spend or pay a charge, for example, pensions for public sector employees. Pensions in AME are fully funded by HM Treasury, so do not impact on the Scottish Government's spending power. Non-domestic rates are also classed as an AME item in the budget and form part of Local Government spending.

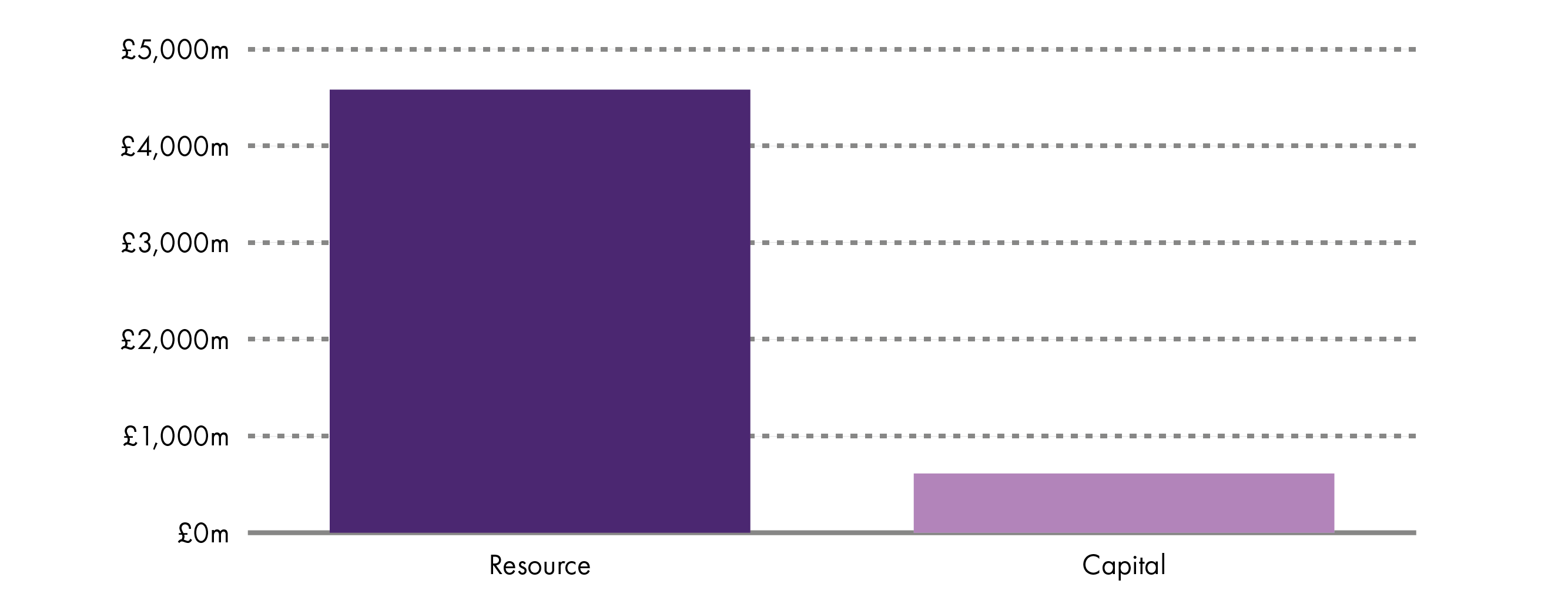

Figure 2 Below shows the real terms changes in Resource and Capital between 2019-20 and 2020-21, and includes Social Security spend and Farm Payments.

Portfolio allocations

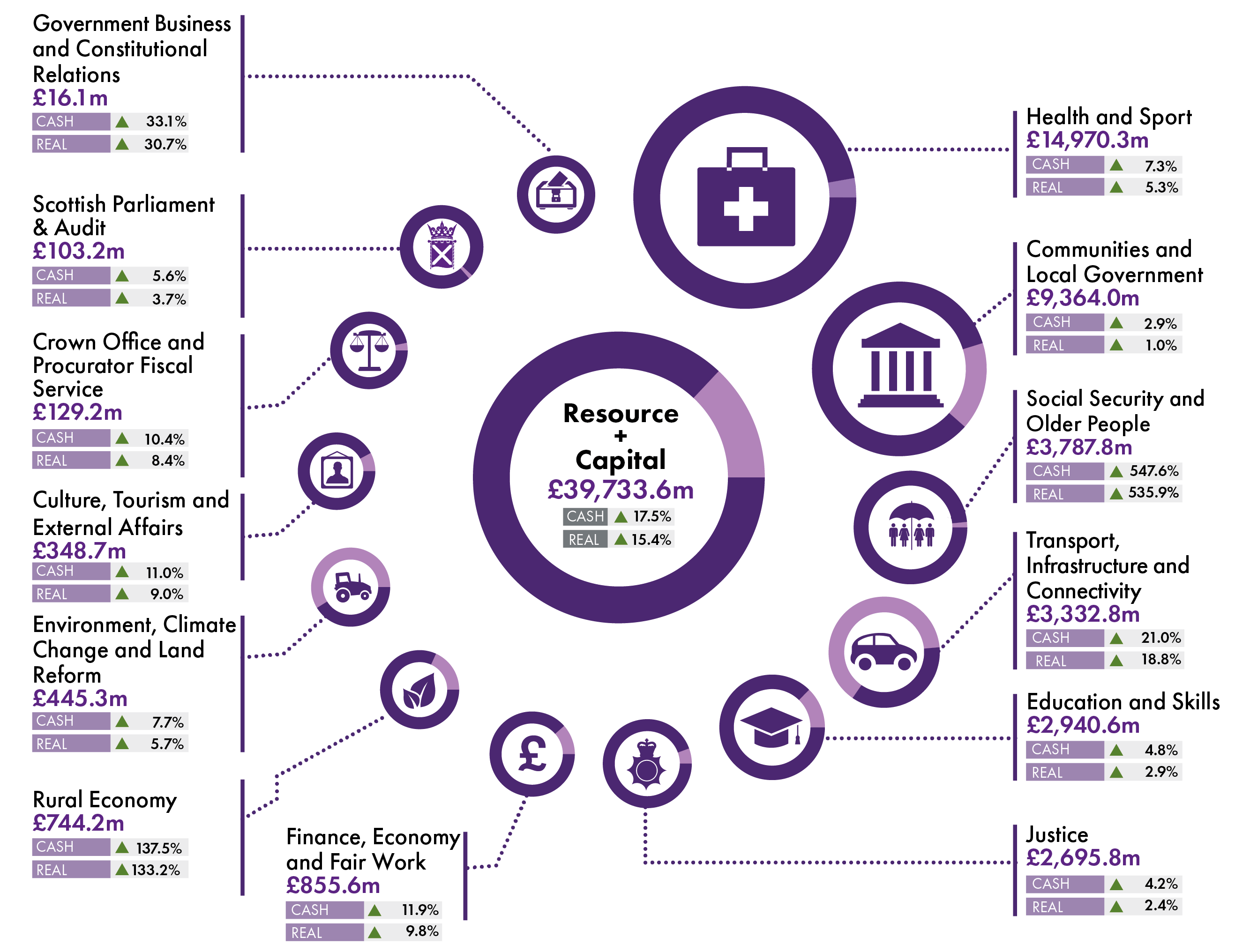

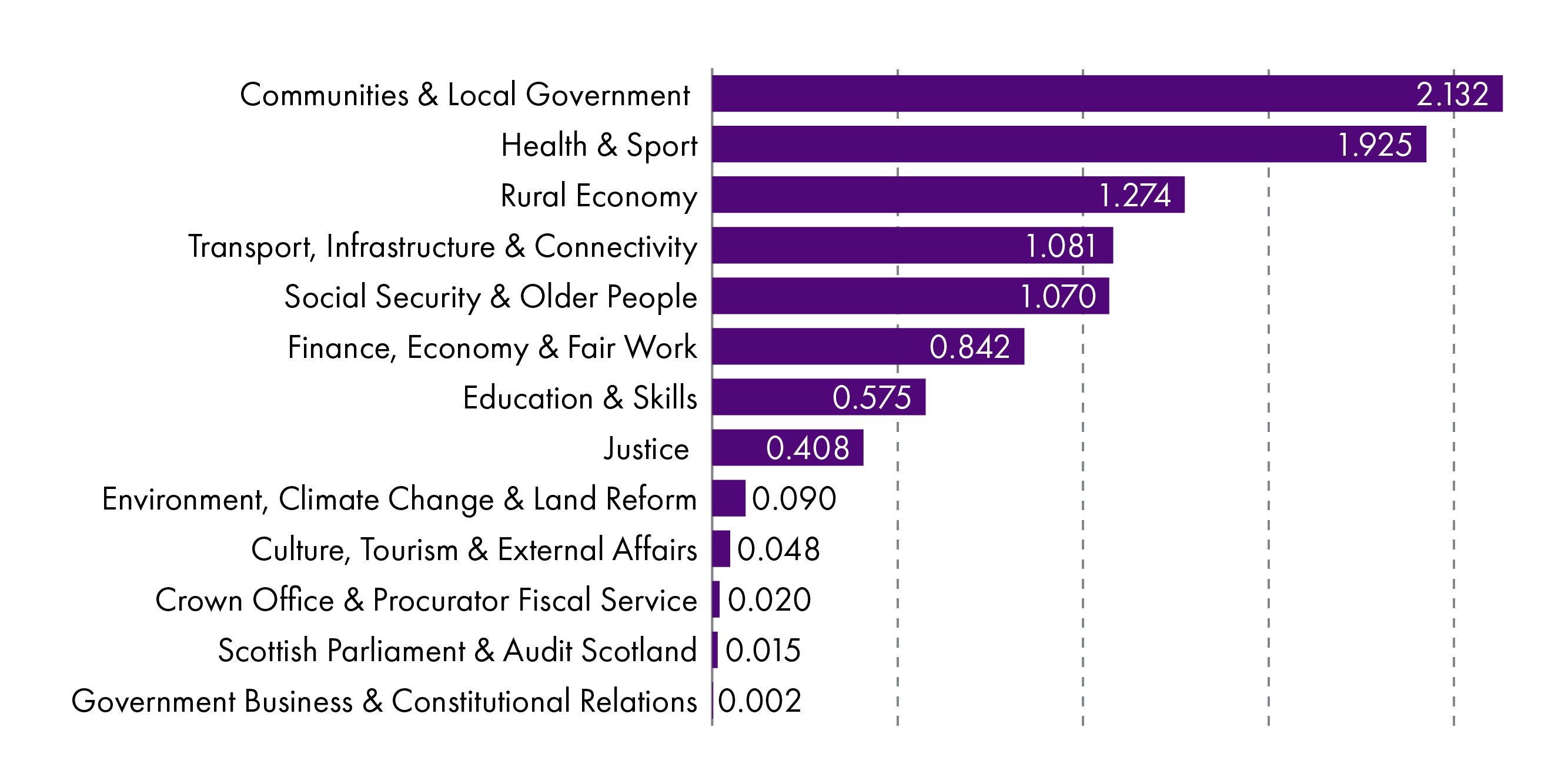

Resource and Capital allocations to portfolios for 2020-21 and how they have changed on the previous year, are presented in figure 3.

Figure 3 shows Resource and Capital spending by portfolio and their cash and real terms changes in 2020-21. Key points to note are as follows:

Health and Sport is the largest portfolio, comprising 38% of the discretionary spending power (Resource and Capital) of the Scottish budget in 2020-21

The next largest portfolio is Communities and Local Government which comprises just under 24% of the Resource and Capital spend combined, although this does not include Non-Domestic Rates Income (NDRI) which is in AME but forms part of the local government settlement. Local government, and the settlement to local authorities, is the subject of another SPICe briefing, due for publication in the week of 10 February 2020.

All portfolios will increase in real terms in 2020-21, a change from recent years. In 2019-20 four portfolios saw their Budget decreased after inflation.

The lowest real terms growth goes to Communities and Local Government (1.0%) (although again it should be noted this does not include NDRI), Justice (2.4%) and Education & Skills (2.9%).

Resource and Capital allocations

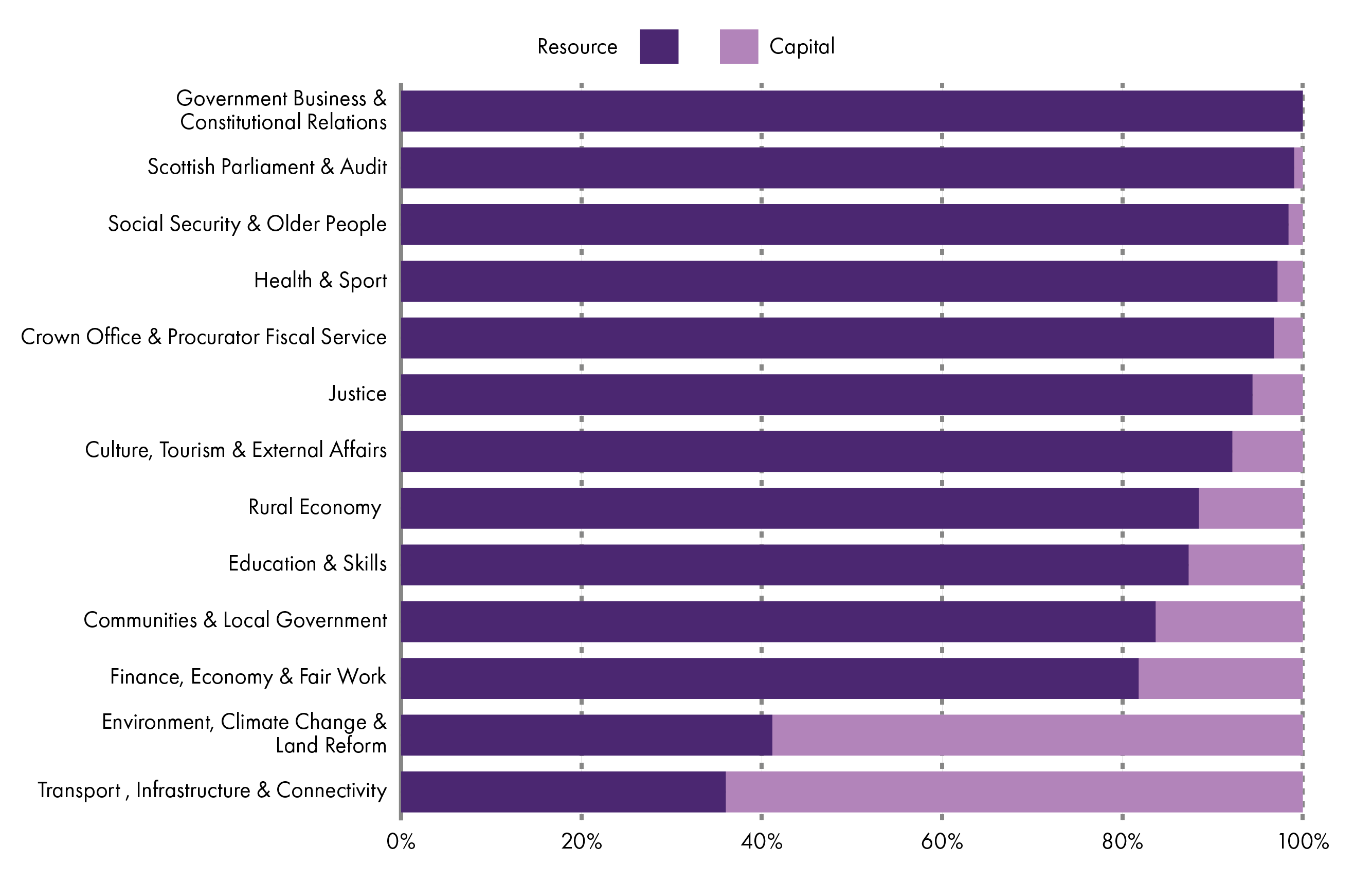

Figure 4 below shows the split between Resource and Capital by portfolio. This shows that most portfolios are heavily weighted towards funding day-to-day spending commitments.

Not surprisingly, the Transport, Infrastructure and Connectivity portfolio has the highest proportion of its budget comprising Capital expenditure (over 60%). Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform is the only other portfolio where over half of its budget is allocated to Capital investment.

Social Security

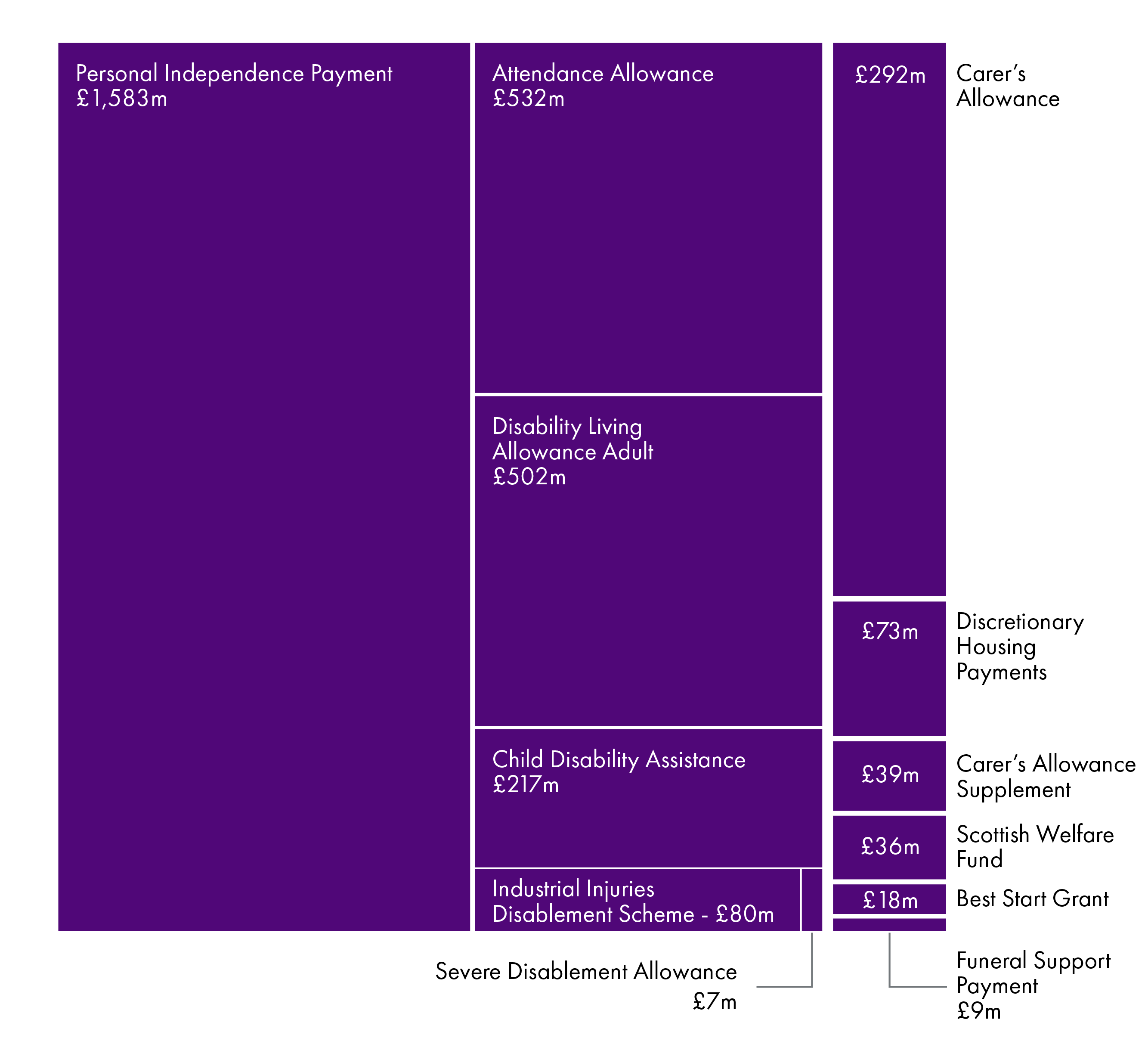

Last year’s budget contained Social Security spending of £575 million. In 2020-21, that figure will rise to £3.7 billion due to the transfer of financial responsibility for certain social security payments amounting to £3,203 million.

The SFC forecast for spending on these new Social Security responsibilities is £3,213 million, meaning that the forecast spend on Social Security will be £10 million higher than the money actually being transferred by the UK Government.

Although the SFC forecasts and the Social Security Block Grant Adjustment (BGA) are forecast to broadly match in 2020-21, future years are less likely to be so closely aligned. The SFC in their Economic and Fiscal Forecasts report state:

Almost all the social security forecasts reflect current UK Government policy because the DWP will continue to administer the benefits during 2020-21. This is important because once the forecasts are based on Scottish policy, we expect the forecasts of Scottish spending to increase given Ministerial announcements and the passage of the Social Security (Scotland) 2018 Act. Any differences between spending and the BGAs will have to be managed within the Scottish Budget.

Figure 5 shows the various Social Security powers now devolved to the Scottish Parliament by size.

Largest real terms increases and decreases

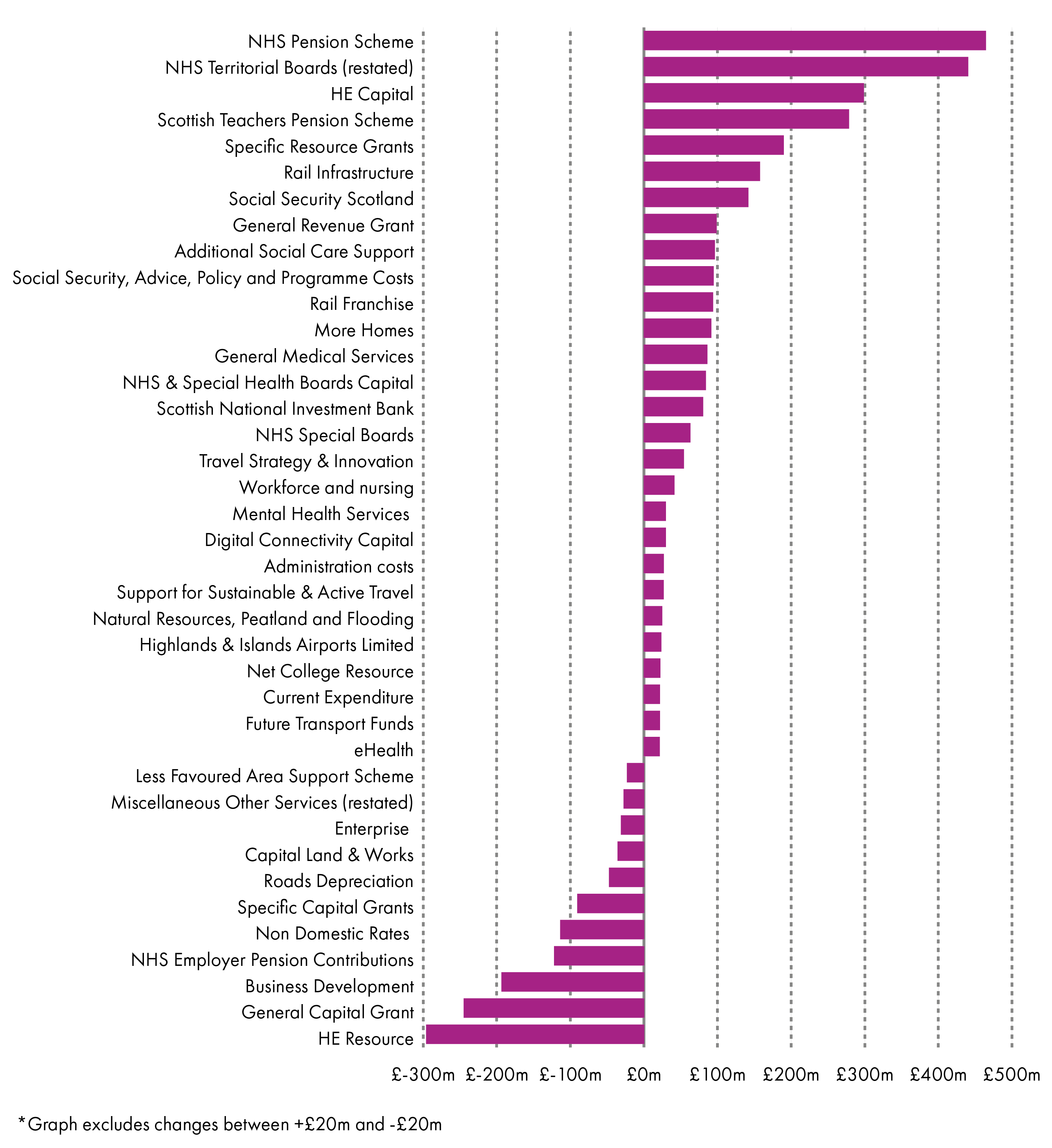

Figure 6 presents the largest real terms level 3 budget line increases and decreases in 2019-20 compared with the previous year.

There are large increases for NHS and Teachers pensions, which are not fully explained in the document, although both are AME items i.e. fully funded by the UK Government.

The NHS territorial boards receive a large increase (growing by £440 million in real terms).

The Higher Education Capital increase and Resource decrease are explained by a £300 million switch from resource to capital in the Scottish Funding Council’s budget compared to last year. There appears to be little practical difference in this change, other than that the Scottish Funding Council would have previously allocated funds to universities for teaching, research and other activities from its Resource budget.

For more information on these individual budgets lines and their portfolios, please see the detailed Levels 1 to 3 spreadsheets, published on the SPICe webpages.

Taxation policies and revenues

Income tax

Income tax proposals

The Scottish Government set out its proposals for income tax from April 2020 as part of the Scottish Budget 2020-21. The proposed rates and bands are shown below.

| Bands | Band name | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Over £12,500* - £14,585 | Starter | 19 |

| Over £14,585 - £25,158 | Basic | 20 |

| Over £25,158 - £43,430 | Intermediate | 21 |

| Over £43,430 - £150,000** | Higher | 41 |

| Above £150,000** | Top | 46 |

* Assumes individuals are in receipt of the standard UK personal allowance (assumed to remain at £12,500 in 2020-21)

** Those earning more than £100,000 will see their personal allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000

These proposals incorporate:

A 0.2% increase in the threshold for the basic rate and a 0.9% increase in the threshold for the intermediate rate.

No change in the higher rate threshold or top rate threshold, which remain at £43,430 and £150,000 respectively.

The proposed increases to the basic rate and intermediate rate thresholds are below inflation, but have the effect of ensuring that the amount of income at which starter rate tax and basic rate tax is paid increases in line with inflation. For example, in 2019-20, the first £2,049 of taxable income was taxed at 19%. Under these proposals, the first £2,085 will be taxed at 19%, which represents an inflationary increase of 1.7%.

The UK Government has previously announced its intention to maintain the 2019-20 income tax policy in 2020-21, having met its commitment to increase the personal allowance to £12,500 and the higher rate threshold to £50,000 a year earlier than originally planned. As such, comparisons with the rest of the UK (rUK) for 2020-21 assume an unchanged income tax policy, as set out in Figure 7. It is also assumed that the tapering of the personal allowance is unchanged i.e. those earning more than £100,000 will see their personal allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000.

Income tax revenues

The Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) forecast that, with the proposals set out in the budget, non-savings non-dividend (NSND) income tax revenues will total £12,365 million in 2020-21. Forecasts for subsequent years, based on no change in policy other than uprating of thresholds in line with inflation, are shown in Table 4.

| 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSND income tax | 12,365 | 12,897 | 13,447 | 14,059 | 14,722 |

The Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) estimates that in 2020-21, the income tax proposals will raise an additional £51 million, relative to what would have been raised if all thresholds (other than the top rate threshold) had risen in line with inflation. This takes account of potential changes to behaviour as a result of the change in policy, which are estimated to reduce revenues by £7 million. Further, more detailed discussion of the SFC's forecasts can be found in the dedicated section of the briefing.

Impact on individuals

Income tax at various levels of earnings under the Scottish Government proposals is shown in Table 5. The proposals mean that all Scottish taxpayers will pay less income tax in 2020-21 than they did in 2019-20. However, the differences are very small – only 36p a year for those earning less than £24,000 rising to £2.50 per year for higher earners.

When compared with what individuals would be paying in the rUK, the comparisons are less favourable. Under the Scottish Government proposals, those earning less than around £27,000 will pay slightly less (around £21 per year) than they would in rUK. However, those earning more than £27,000 will pay more tax in Scotland than they would in rUK. This accounts for 44% of taxpayers, according to the Scottish Government, and the differential is in excess of £1,500 a year for those earning more than £50,000. The difference will increase if the UK Government decides to increase the higher rate threshold in its March budget.

| Annual earnings | Scottish Government proposals 2020-21 | Difference compared with 2019-20 | Difference compared with rUK |

|---|---|---|---|

| £ per year | £ per year | £ per year | |

| 15,000 | 479 | -0.36 | -20.85 |

| 20,000 | 1,479 | -0.36 | -20.85 |

| 25,000 | 2,479 | -0.84 | -20.76 |

| 30,000 | 3,528 | -2.50 | 27.57 |

| 35,000 | 4,578 | -2.50 | 77.52 |

| 40,000 | 5,628 | -2.50 | 127.57 |

| 45,000 | 6,992 | -2.50 | 491.57 |

| 50,000 | 9,042 | -2.50 | 1,541.57 |

| 55,000 | 11,092 | -2.50 | 1,591.56 |

| 60,000 | 13,142 | -2.50 | 1,641.57 |

| 65,000 | 15,192 | -2.50 | 1,691.52 |

| 70,000 | 17,242 | -2.50 | 1,741.56 |

| 75,000 | 19,292 | -2.50 | 1,791.60 |

| 80,000 | 21,342 | -2.50 | 1,841.52 |

| 85,000 | 23,392 | -2.50 | 1,891.56 |

| 90,000 | 25,442 | -2.50 | 1,941.60 |

| 95,000 | 27,492 | -2.50 | 1,991.52 |

| 100,000 | 29,542 | -2.50 | 2,041.57 |

National Insurance contributions

Decisions on national insurance contributions (NICs) are made by the UK Government, but will interact with the Scottish Government's decisions on NSND income tax to determine overall tax rates. NICs are linked to rUK tax thresholds and the NIC rate drops from 12% to 2% at the rUK higher rate threshold, which is expected to be £50,000 from April 2020. This means that Scottish taxpayers who earn between the proposed Scottish higher rate threshold (£43,430) and the rUK higher rate threshold (£50,000) will pay 41% income tax and 12% NICs on their earnings between these two amounts – a combined tax rate of 53%. The UK Government has already announced that it will increase the NIC threshold from £8,632 to £9,500 in April 2020, a move that will benefit Scottish taxpayers, but will not do anything about the 53% marginal tax rate faced by those earning between the Scottish and rUK higher rate thresholds.

Behavioural impacts

Any changes to tax policies can result in individuals changing their behaviour so as to minimise the tax that they pay. If they are able to, taxpayers might try to change how they receive their income (for example, by taking it in the form of dividends or setting themselves up as a company). Or, they might move to a different location where tax rates are lower (again, if this is a realistic possibility). As Scottish tax policy diverges further from rUK tax policy, the risk that individuals might change their behaviour increases.

In their February 2020 Economic and Fiscal Forecasts, the SFC judged that the Scottish Government’s proposed income tax policy (when compared with a policy which included uprating of the higher rate threshold) would generate £59 million, but that changes in taxpayer behaviour would reduce the actual amount generated to £51 million. The SFC also said that they had reviewed their assessment of potential migration in response to changes in tax policy and thought it could be higher than previously estimated.

Alongside the budget document, the Scottish Government also published a paper on ‘Understanding the Behavioural Effects from Income Tax Changes’1. In this paper, the Scottish Government noted that:

..the empirical evidence on the behavioural effects of Scottish taxpayers is limited. There is currently no data which would allow us to evaluate the comprehensive changes to income tax implemented in 2018-19.

The paper concludes that:

The updated evidence suggests that behavioural change impacts, reflecting differences between income tax rates in Scotland and the rUK, remain small at best and do not materially diminish the extra revenues gained from the Scottish Government’s income tax changes.

The Council of Economic Advisers have also been reviewing potential behavioural effects and the possible impact on future revenues.

Devolved taxes

This section sets out the impact of the Budget on devolved taxes other than Non-Savings Non Dividend (NSND) income tax. These taxes are Non-Domestic rates, Land and Buildings Transaction tax and the Scottish Landfill tax. Further, more detailed discussion of the SFC's forecasts can be found in the dedicated section of the briefing.

Non-Domestic Rates

Non-Domestic Rates (NDR, also known as ‘business rates’) are taxes paid on non-residential properties. The Scottish Government sets the tax rates for NDR, but local authorities administer and collect the tax, and the revenues from this tax form part of the local government resource budget.

The tax is charged based on the rateable value of the property as determined by independent assessors, with the rateable value multiplied by the tax rate (called ‘Poundage’) to calculate the tax liability. There are several rate relief schemes, such as the Small Business Bonus Scheme, which can reduce this liability.

The budget introduces a proposed Intermediate Property Rate for properties with a rateable value of between £51,000 and £95,000. In previous years, these properties would have paid the Higher Property Rate (previously known as the Large Business Supplement), and so this amounts to a 1% reduction in the tax rates for these properties. The Basic Property Rate and the Higher Property Rate have both risen by 1.6%. The Scottish Fiscal Commission estimate that the introduction of the Intermediate Property Rate will reduce the amount collected through NDR by £7 million in 2020-21.

| 2019-20 | 2020-21 | % change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Property Rate (‘Poundage’) | 49.0p | 49.8p | +1.6% |

| Intermediate Property Rate (rateable values between £51,000 and £95,000)* | 51.6p | 51.1p (Poundage + 1.3p) | -1.0% |

| Higher Property Rate (rateable value above £95,000) | 51.6p | 52.4p (Poundage + 2.6p) | +1.6% |

On 5 February 2020, just one day before the Scottish Government published its Budget, the Scottish Parliament passed the Non-Domestic Rates (Scotland) Bill ("the Bill").The aim of the Bill was specifically to address those recommendations arising from the Barclay Review of Non-Domestic Rates which required primary legislation.

The policy memorandum for the Bill sets out that the policy objectives are to:

deliver a Non-Domestic Rates system designed to better support business growth and long-term investment and reflect changing marketplaces

improve ratepayers' experience of the rating system and administration of the system

increase fairness and ensure a level playing field amongst ratepayers by reforming rate reliefs and tackling known avoidance measures.

More about the background to the Bill and specific provisions can be found in the SPICe Bill briefing.

Certain changes to the Bill made throughout the parliamentary process may impact on the amount of Non-Domestic Rates income received by local authorities. For instance, independent mainstream schools will no longer benefit from charitable rates relief.

However, as explained in the SPICe briefing on the Funding Formula and local taxation income, this does not mean more income for those local authorities affected; rather, it means that more income in those authorities will come from NDR, and less from the Scottish Government’s Revenue Grant. Further down the line, measures designed to strengthen guidance and tackle tax avoidance may have some impact in later years once implemented, but ultimately the interaction of NDR with Scottish Government funding will remain the same. The Scottish Fiscal Commission project that collectively the changes in the Bill will increase NDR income by £17m in 2020-21.

Land and Buildings Transaction Tax

Land and Buildings Transaction tax has been devolved to the Scottish Parliament since April 2015 and replaced UK Stamp Duty Land Tax. This tax is applied to residential and non-residential land and building transactions where a chargeable interest is acquired, including commercial leases. There is also an Additional Dwelling Supplement (ADS) which applies to residential purchases of second homes. The Scottish Government proposes no changes to the tax bands or rates for the residential or non-residential transactions or the rate of ADS, but has introduced a new band for non-residential leases. This band will be applicable for transactions where the net present value of the rent over the period of the lease exceeds £2 million. This change will be introduced through secondary legislation and will be applicable from 7 February 2020, provided the contract for the transaction was concluded after 6 February 2020. The SFC forecast that this change will increase income from LBTT by £10 million in 2020-21.

In the 2019-20 Scottish Budget the Scottish Government proposed the introduction of two targeted relief schemes which aimed to safeguard investment in property investment funds. The Government did not bring forward legislation for these reliefs, citing continued uncertainty around the terms of the UK’s exit from the EU. In the 2020-21 Budget the Scottish Government states that it plans to publish a consultation on draft legislation during 2020-21.

| Residential transactions | Non-residential transactions | Non-residential leases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase price | LBTT rate | Purchase price | LBTT rate | Net present value of rent payable | LBTT rate |

| Up to £145,000 | 0% | Up to £150,000 | 0% | Up to £150,000 | 0% |

| £145,001 to £250,000 | 2% | £150,001 to £250,000 | 1% | £150,001 to £2 million | 1% |

| £250,001 to £325,000 | 5% | Over £250,000 | 5% | Over £2 million** | 2% |

| £325,001 to £750,000 | 10% | ||||

| Over £750,000 | 12% | ||||

ADS rate of 4% applies to the total price of all property of relevant residential transactions, in addition to the rates set out in table 7.

Scottish Landfill Tax

In September 2019, the Cabinet Secretary for Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform announced that full enforcement of the ban on sending biodegradable municipal waste to landfill would be delayed until 2025, in response to concerns that the only way local authorities could meet the deadline would be to export waste to England. The ban was originally to take effect from 1 January 2021, and so the SFC expects that this will result in a £25 million increase in the amount raised by this tax during the 2020-21 financial year.

| 2019-20 | 2020-21 | % increase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard rate | £91.35 | £94.15 | 3.1% |

| Lower rate | £2.90 | £3.00 | 3.4% |

Block grant adjustment

Since the devolution of tax and social security powers introduced by Scotland Act 2016, there has been a need to adjust the Scottish Government's block grant from the UK Government to reflect the fact that Scotland generates tax revenues and incurs expenditure on social security benefits. Changes to the Scottish Government's block grant will still be determined by the Barnett formula, which reflects changes to UK spending areas that are devolved to the Scottish Parliament. The block grant is then adjusted to reflect the retention of some tax revenues in Scotland, and the transfer of new social security powers.

In relation to taxes, the initial block grant adjustment (BGA) was equal to the UK Government's tax receipts generated in Scotland in the year immediately prior to devolution. In subsequent years, the BGA for taxes has been calculated according to indexation mechanisms agreed as part of the Fiscal Framework 1.

The differences between the BGA and the SFC's forecasts will reflect

different tax policies set by the Scottish and UK Governments

different economic conditions

different forecast methodologies used by the SFC and the OBR.

The Scottish Government's income tax policy is expected to generate £46 million more than will be provisionally deducted from the Scottish Government block grant in relation to income tax.

BGAs remove funding where the Scottish Government is now raising its own tax revenue and add funding where the Scottish Government is responsible for social security payments.

To understand how much more or less the Scottish Government has to spend, with certain taxes or benefits devolved to Scotland we can compare BGAs with SFC forecasts, as shown in the tables below. SFC caveat that in current circumstances, any comparison should be made with caution as the BGAs are based on the OBR’s March 2019 economic assumptions while the SFC forecasts include more up to date information. The BGAs are likely to change following the UK Budget in March.

| 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tax revenue | 11,621* | 12,081 | 12,414 | 13,123 | 13,673 | 14,233 | 14,858 |

| Tax BGA | 11,710* | 12,159 | 12,329 | 12,963 | 13,424 | 13,905 | 14,439 |

| Difference | -88* | -78 | 85 | 160 | 249 | 328 | 419 |

*Italics shows outturn as available at time of SFC publication

| 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social security spending | 152* | 276 | 3,213 | 3,312 | 3,411 | 3,500 |

| Social security BGA | 157* | 286 | 3,203 | 3,357 | 3,535 | 3,718 |

| Difference | 5* | 10 | -10 | 45 | 124 | 218 |

*Italics shows outturn as available at time of SFC publication

The Scottish Government’s decision not to replicate rUK tax policy means tax revenues are around £650 million higher than would otherwise be the case (before accounting for any behavioural changes). However, these higher tax revenues are almost entirely offset by the deduction to the Scottish budget (the BGA) which reflects the tax foregone by the UK Government due to devolution of tax powers.

The budget document shows that Scottish income tax policy is estimated to generate £12,365 million in 2020-21. This is only £46 million more than will be deducted through the block grant adjustment. So, rather than generating an additional £600 million or more for the Scottish budget, the different income tax policy is only just managing to offset the block grant adjustment.

This is largely because of differences in earnings growth and the composition of taxpayers in Scotland compared to the rest of the UK. Because of these differences between the two economies, the Scottish Government is having to set higher taxes in order to generate enough revenue to offset the block grant adjustment. For around half of Scottish taxpayers, income tax devolution has meant higher tax bills, but no additional spending power for the Scottish Budget . Meanwhile, as highlighted above, those benefiting from lower taxes are only seeing relatively small gains (£21 per year in 2020-21 if rUK policy is unchanged). These issues are explored in more detail in a previous SPICe blog.

Reconciliation of forecasts to actual data

Scottish Budget 2020-21 is the first with significant reconciliations applied.

SFC forecasts have impacts on the reconciliation process. A previous SPICe blog (July 2019) highlighted the reconciliation needed to reflect the difference between forecasts made in late 2016 (when the 2017-18 budget was set) and the actual outturn for both Scottish income tax receipts and the block grant adjustment. In both cases, the original forecasts were too high. At the time we highlighted how this would impact the 2020-21 Scottish Budget, where the Scottish Government would need to either raise taxes, cut spending or utilise reserves/ borrowing to make up this shortfall.

SFC state that the final reconciliation applied in 2020-21 will amount to -£207 million, which is largely based on the income tax reconciliation (£204 million). To deal with this, the Scottish Government has chosen the borrowing option. The Scottish Government plans to use its resource borrowing powers for the first time in 2020-21, announcing plans to borrow £207 million. This borrowing will be repaid over the next five years.

SFC’s indicative income tax reconciliation for the following year’s budget (2021-22) is estimated at -£555 million.

On this issue of managing reconciliations and borrowing, SFC warn that:

Budget management between years will also become more important. Reconciliations which adjust the budget to account for forecast errors in previous years, may become larger. Although our current estimates of the indicative income tax reconciliations in the next two years must be considered with caution, these predict much larger negative effects on future budgets than we have seen this year. The Scottish Government will need to consider how to manage these in future years. Based on the information we have to date, and the evidence that the balance of the reserve has been falling in recent years, it would seem from these plans that the Scottish Government is not building up large reserves to mitigate the large expected income tax reconciliations in 2020-21 and 2021-22.

Scotland Reserve

The Scotland Reserve is split into Resource and Capital and has an overall limit of £700 million. The maximum that can be drawn from the Scotland Reserve in a single year is £250 million in Resource and £100 million in Capital.

The following tables reproduce the SFC's presentation of previous and planned use of the Scotland Reserve. Table 11 covers Resource, table 12 Capital and table 13 Financial Transactions.

On the Resource Reserve, the Scottish Government currently forecast £206 million will remain in the Resource Reserve at the end of the current year. There are plans to draw down £106 million in 2020-21, leaving a closing balance of £100 million at the end of the next financial year. However, this position is likely to change.

| £ million | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opening balance | 74 | 440 | 381 | 206 |

| Drawdowns | 0 | -250 | -250 | -106 |

| Additions | 366 | 191 | 75 | 0 |

| Closing balance | 440 | 381 | 206 | 100 |

The Capital Reserve covers both Capital and Financial Transaction monies. The annual drawdown limit of £100 million applies to the combined values of Capital and Financial Transaction drawdowns. In the current financial year (2019-20) large negative consequentials reduced the expected size of the Scottish Capital Budget and HM Treasury agreed to waive the £100 million limit and allow a combined £181 million Capital and Financial Transaction drawdown.

| £ million | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opening balance | 0 | 87 | 65 | 5 |

| Drawdowns | 0 | -22 | -60 | -5 |

| Additions | 87 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Closing balance | 87 | 65 | 5 | 0 |

| £ million | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opening balance | 0 | 11 | 159 | 38 |

| Drawdowns | 0 | 0 | -121 | -32 |

| Additions | 11 | 147 | 0 | 0 |

| Closing balance | 11 | 159 | 38 | 6 |

The Scottish Fiscal Commission forecasts

The Scottish Fiscal Commission's (SFC) main forecast publication Scotland's Economic and Fiscal Forecasts February 2020 was published alongside the Scottish Budget for 2020-21. The SFC’s forecasts are an important component in determining the total budget available to the Scottish Government to spend in each financial year. In this section, we summarise some of the key economic trends from the SFC’s detailed economic forecasts.

GDP forecasts

Overall, SFC present a subdued economic outlook for Scotland.

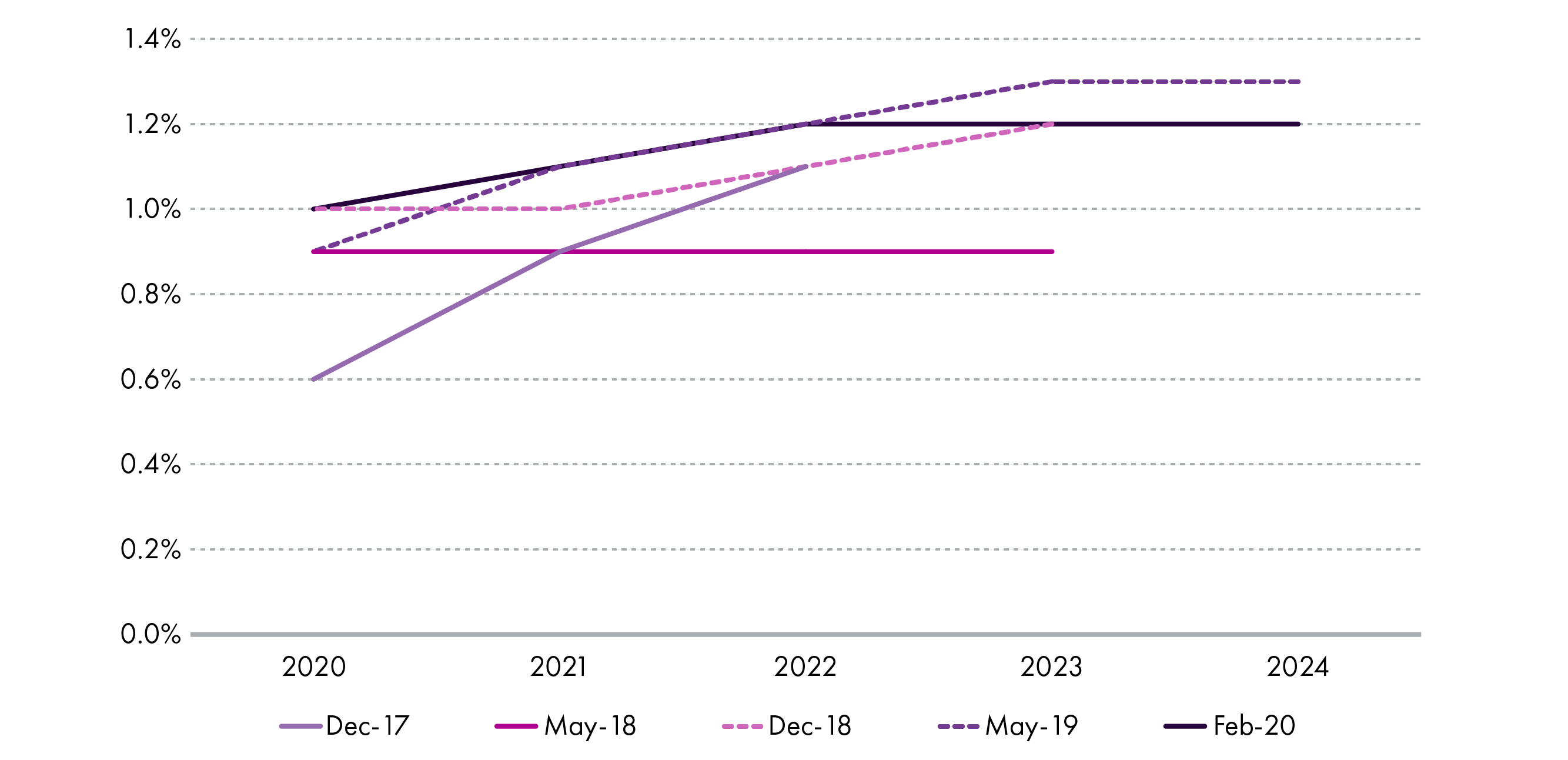

The outlook for earnings, which feeds into the forecasts for income tax, has improved marginally since the SFC’s last assessment in May. Hence, SFC’s headline GDP forecast for 2020 at 1% is slightly up on their May 2019 forecast of 0.9% and in line with the December 2018 forecast of 1% (see Figure 8). There were small downwards revisions from 2023 onwards relative to SFC’s May 2019 forecast. The SFC predict that growth in 2020 will be supported by reduced Brexit uncertainty (compared to previous SFC forecast) and an earnings uplift but the long-term outlook remains weak.

Figure 8 shows headline GDP growth forecasts (annual percentage change) from all of SFC’s economic forecasts since December 2017.

The main factors driving SFC’s revised headline GDP forecast figures for 2020 include:

revised up forecasts of earnings growth supporting greater household consumption

higher UK and Scottish Government spending, which is expected to continue to support growth in the Scottish economy

productivity growth remaining low in the short term, which then starts to gradually increase.

Some of these factors are discussed in more detail in the following section.

SFC predict that a Scotland-specific economic shock, as defined by the fiscal framework, is not expected to occur.

The impact of Brexit features across SFC’s economic forecasts. SFC highlight that Brexit has resulted in subdued growth over the last year and greater volatility between quarters. Nonetheless, the unwinding of some Brexit-related uncertainty may support some additional growth. Brexit is flagged as a risk to continued economic growth and is expected to affect Scotland’s trade prospects.

In terms of Brexit, the SFC treat the period after 31 January until December 2020 as a transition period. Assumptions used in forecasting were:

new trading arrangements with the EU and others slow the pace of import and export growth

the UK adopts a tighter migration regime than that currently in place.

Wider economic factors

Productivity

SFC’s estimate of productivity growth in Scotland remains low and has been downgraded further relative to previous forecasts. SFC has revised down productivity growth by approximately 0.3 percentage points in 2019 and 2020 since May 2019. SFC had expected productivity growth to be 0.7 per cent in 2019 but their most recent estimates show continuing subdued trend growth. SFC are of the view that an immediate pick-up in productivity looks implausible and that it will take longer for growth in output per hour to recover.

| Date of SFC forecast | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| December 2017 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.0 | ||

| May 2018 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | |

| December 2018 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 | |

| May 2019 | 0.1* | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| February 2020 | 0.2* | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

*Italics shows outturn as available at time of SFC publication

Earnings

Earnings growth has exceeded SFC’s previous expectations. This higher than expected growth was driven by tight conditions in the labour market and growth in public sector pay policy, the minimum wage and national living wage. SFC has made upward revisions to earnings growth over the period 2019 to 2021. However, it should be noted that earnings growth, both nominal and real, remain below historical values over the forecast period.

| Date of SFC forecast | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| December 2017 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.1 | ||

| May 2018 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 3.2 | |

| December 2018 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.1 | |

| May 2019 | 2.6* | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 3.2 |

| February 2020 | 2.6* | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.3 |

*Italics shows outturn as available at time of SFC publication

Employment

SFC believe that the labour market appears to be reaching a turning point, with employment no longer rising and the unemployment rate stabilising. However, the labour market remains tight. Employment is expected to continue to grow, although at a slower rate than over the last few years. SFC has revised down employment forecasts relative to May 2019. However, employment forecasts are up on December 2018.

| Employment (millions) | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| December 2018 | 2.64 | 2.65 | 2.65 | 2.66 | 2.66 | 2.66 | |

| May 2019 | 2.67* | 2.68 | 2.68 | 2.69 | 2.69 | 2.69 | 2.70 |

| February 2020 | 2.67* | 2.68 | 2.67 | 2.67 | 2.68 | 2.68 | 2.69 |

*Italics shows outturn as available at time of SFC publication

UK comparison

The Scottish Budget has been set before the UK Budget has been published and there has not been an autumn UK fiscal event with its accompanying OBR forecasts.

In the absence of an updated UK economic outlook from the OBR, SFC used forecasts of the UK economy published by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) in November 2019.

However, OBR forecasts should still be used as the main source of comparison for continuity purposes. Below is a comparison of SFC’s forecast with the most recently available OBR forecast.

Compared to the OBR’s forecasts for the UK, the SFC has forecast slower GDP growth for Scotland. This is in part because of slower population growth. However, given the time differences in the forecast periods any comparison needs to be caveated until updated OBR data is available in March.

SFC’s next forecasts, due to be published alongside the Scottish Government’s Medium Term Financial Strategy (MTFS) currently anticipated in May, will be combined with the March UK Budget and updated OBR forecasts to provide an updated overview of the Scottish public finances. SFC note that “the Scottish Government and Parliament will need to consider how best to monitor and respond to these in-year budget revisions”.

Linking the SFC forecasts to the budget

The SFC’s fiscal forecasts directly determine the Scottish Government’s Budget, particularly around tax and social security.

In total the SFC are forecasting £16 billion of the Scottish Budget will be raised by devolved tax in 2020-21 (£15.2 billion in 2019-20).

SFC has forecast that the new devolved social security powers mean spending in this area will account for 10 per cent of all resource spending, or £3.4 billion. SFC warn that social security spending can be "variable and difficult to manage within the year because everyone who applies and qualifies for a benefit must be paid". Thus, any differences between SFC forecasts and the actual amount spent in 2020-21 will need to be managed within the Scottish Budget.

Forecasts for devolved taxes

This section gives an overview of the latest forecasts from the Scottish Fiscal Commission for revenues from devolved taxes and how these have changed since the last publication (May 2019 – to accompany the Medium-Term Financial Strategy) and the December 2018 forecast which accompanied the last Budget. This section covers Non Savings Non Dividend income tax , Non-Domestic Rates, Land and Buildings Transaction Tax , Scottish Landfill Tax and Social Security. In an earlier section of the briefing we look in more detail at the Scottish Government's tax policies.

Non-savings, non-dividend income tax

The SFC have revised their forecast for Non-savings, non-dividend (NSND) revenues since the May 2019 forecast. 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20 are revised down by a total of £233 million, while between 2020-21 and 2023-24 the forecast has been revised up by a total of £246 million. Table 17 below sets out the updated forecast for NSND revenues, compared to the May 2019 forecast and the December 2018 forecast.

| 2017-18outturn | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFC February 2020 | 10,916 | 11,378 | 11,677 | 12,365 | 12,897 | 13,447 | 14,059 |

| Change since SFC May 2019 | - 89 | - 108 | - 26 | 33 | 66 | 73 | 74 |

| Change since SFC December 2018 | - 92 | - 74 | - 7 | 80 | 151 | 205 | 254 |

There are several factors which have contributed to these revisions:

HMRC published the first outturn data for Scottish NSND covering the 2017-18 tax year, and this is the only factor resulting in a revision to that year.

In subsequent years, there are several factors. The outturn data from HMRC also impacts other years in the forecast, lowering projected revenues by £90 million in 2018-19 and £140 million in 2023-24.

Economy earnings data has been revised upwards since the last Scottish budget which has a significant impact of the forecast; £129 million increase in revenues in 2018-19 which increases to £544 million by 2023-24.

The forecast for unemployment has also increased slightly over this period though, which reduces forecast revenues by a total of £245 million between 2018-19 and 2023-24.

Non-Domestic Rates

The SFC forecast for NDR in 2020-21 is £2,749 million, £86 million lower in real terms than in 2019-20 (a real terms decrease of 3.2%). Between 2020-21 and 2024-25 this is forecast to rise to £3,590 million.

Compared to the SFC’s previous forecast, NDR revenue is forecast to be £137 million lower in 2020-21, £74 million lower in 2021-22, £50 million higher in 2022-23 and £90 million higher in 2023-24. There are two reasons main drivers of this change since the last forecast – updated data in the form of audited local authority returns and on appeal losses which reduces expected revenues in every year of the forecast, and forecasts of the impact of the NDR Bill which is expected to increase revenues by around £150 million in 2022-23 and 2023-24.

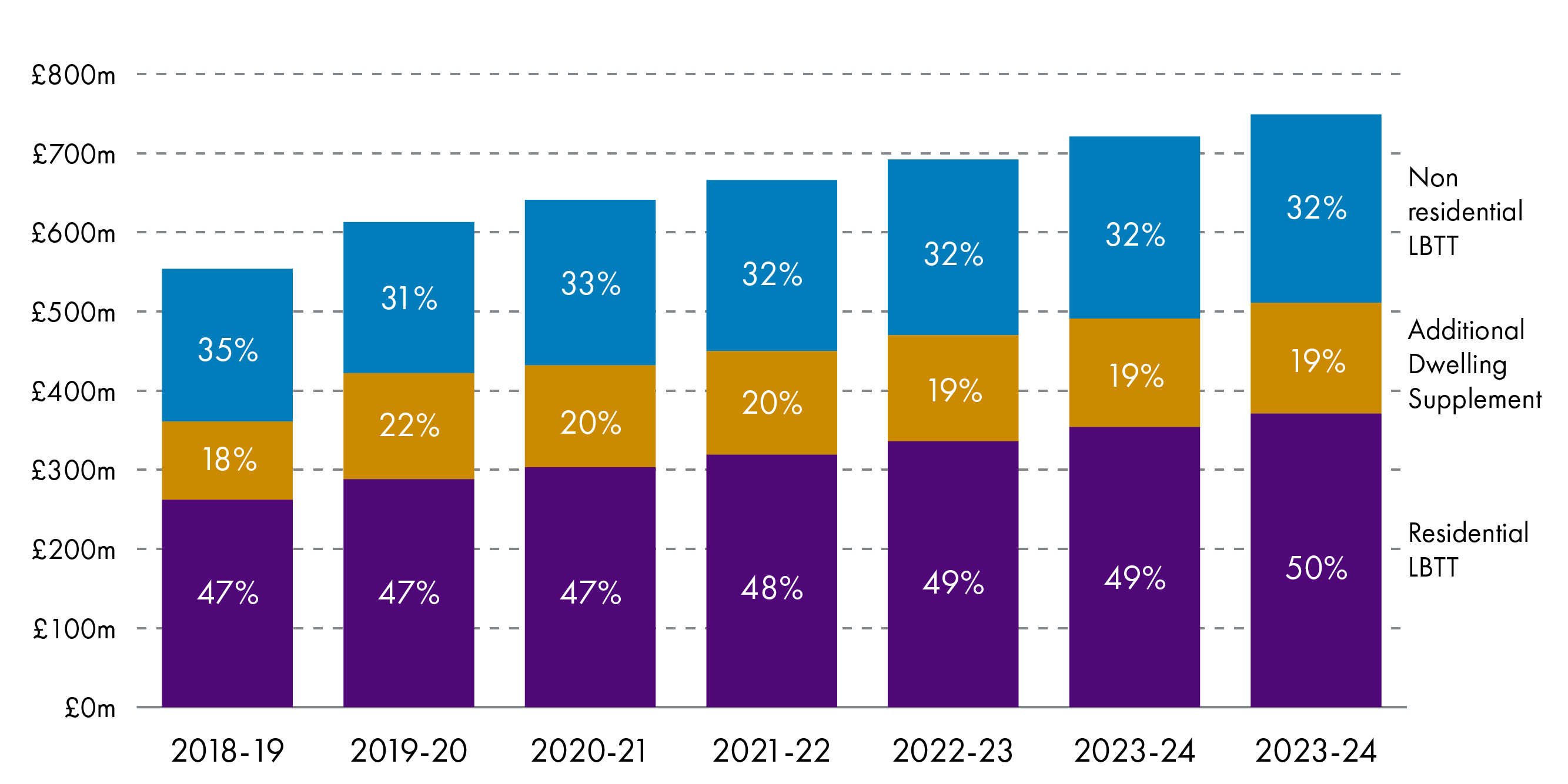

Land and Buildings Transaction Tax

The SFC’s forecast of total revenues from LBTT has been revised down for 2019-20 from £644m in the December 2018 forecast to £613m. Some of this downward revision occurred in the May 2019 forecast update, but there has been a further downward revision since then. Nonetheless, the SFC projects that total LBTT revenues will increase by £167 million (30.1%) between 2018-19 and 2024-25. Table 18 sets out the three most recent forecasts:

| 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2024-25 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFC February 2020 | £554m | £613m | £641m | £666m | £692m | £721m |

| Change since SFC May 2019 | +£1m | -£3m | -£14m | -£25m | -£32m | -£66m |

| Change since SFC December 2018 | -£15m | -£31m | -£39m | -£50m | -£58m | -£66m |

The SFC forecast revenue for LBTT for all three components individually; residential LBTT, the Additional Dwelling Supplement and non-residential LBTT. All three forecasts have changed since the December 2018 forecast; a small increase in the expected revenues from the ADS is more than offset by reductions in expected revenues from both residential and non-residential LBTT. Almost 50% of the projected revenues for LBTT come from residential LBTT, around a third from non-residential and around 20% from the ADS. Figure 10 below sets out the components of expected LBTT revenues from the February 2020 SFC forecast.

There are several factors which have affected the update to each LBTT component. As well as a modelling update and more recent outturn data being available, projections of residential LBTT income have also changed due to:

House price growth up to the end of September 2019 being lower than expected at the time of the December 2018 forecast.

Growth in transactions being higher than expected at the time of the December 2018 forecast.

The updated assumptions around house price and transaction growth also both impact the forecast for ADS revenues. For non-residential LBTT, the updated expectations of house prices and transaction growth have only a minor impact on the expected revenues. The main driver of this change is updated data from Revenue Scotland for 2018-19. This is slightly offset by the expected revenues from the introduction of the new tax band for non-residential leases, which will apply to contracts where the net present value of the leases is above £2 million.

Scottish landfill tax

In September 2019, the Cabinet Secretary for Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform announced that full enforcement of the ban on sending biodegradable municipal waste to landfill would be delayed until 2025. This significantly increased the expected volume of waste coming to landfill throughout the later years of the SFC’s forecast for revenues from this tax – adding £25 million in 2020-21, £103m in 2021-22, and around £80m in 2022-23 and 2023-24.

| 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2024-25 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFC February 2020 | £149m | £124m | £116m | £110m | £94m | £66m |

| Change since SFC May 2019 | +£6m | +£15m | +£29m | +£98m | +£80m | +£51m |

| Change since SFC December 2018 | +£13m | +£20m | +£33m | +£97m | +£81m | +£52m |

Social security forecasts

From 1 April 2020 the Scottish Parliament will have financial responsibility for nearly all of the benefits which are to be devolved, which means this Budget has a significant increase in the amount of spending allocated to social security. Initially these benefits will continue to be based on the UK policy set by the Department for Work and Pensions, so the SFC have forecast the revenues based on current policy. As the Scottish Government develop policy proposals for these replacements for existing UK benefits, the SFC will update their forecasts to account for any differences in the policy as far as they impact expected costs.

Compared to May 2019, the SFC have increased their forecast costs for providing social security in 2020-21 and beyond. While in May the SFC expected total social security spending to reach around £3.6 billion by 2024-25, the new forecast expects spending to reach £3.9 billion by the same year.

| 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFC February 2020 | £3,435m | £3,578m | £3,704m | £3,857m |

| Change since SFC May 2019 | +£396m | +£409m | +£394m | +£402m |

Two new benefits, the Child Disability Allowance and the Scottish Child Payment will be opening to applications in 2020-21, and so the SFC has forecast the expected costs of these policies. The Child Disability Allowance is expected to add £217 million to the cost of providing social security in 2020-21, rising to £312 million in 2024-25, while the Scottish Child Payment is forecast to increase social security costs by £21 million in 2020-21, rising to £162 million in 2024-25.

The SFC note that forecasts for social security are subject to a higher degree of uncertainty than forecasts for devolved taxes. Partly this is due to the lack of clarity about any changes to UK policy which could be announced in March 2020 and the detail for any proposed changes in policy from the Scottish Government following the transfer of executive competence to the Scottish Parliament in April 2020. Social security is also demand led spending, and there are challenges around modelling the take-up rate for the various benefits. These challenges also represent an increased risk to the Scottish Government – as should these forecasts prove to be wrong there could be a material impact on the overall Scottish spending, and therefore on other portfolios in the budget.

Capital and infrastructure

The 2020-21 capital budget from HM Treasury is £4,734 million, a 13.2% increase in real terms compared with 2019-20. The Scottish Government plans to further boost capital expenditure in 2020-21 through a combination of mechanisms:

Using maximum borrowing powers (£450 million).

Using Financial Transactions funding from the UK Government (£892 million).

Capital grant receipts and other income (£101 million).

Financing some projects using revenue financing methods, which avoids the need to pay for projects upfront (projects with a capital value of £20 million funded in this way).

Making use of innovative finance mechanisms, such as the Growth Accelerator and Tax Incremental Financing (£27 million).

Anticipated UK Government transfers from the UK Government in relation to the Glasgow City Deal (£15 million).

Use of £5 million drawdown from the Capital Reserve.

These additional financing sources will mean total capital investment in 2020‑21 of £6,243 million. Further detail on these funding sources is given below.

Borrowing powers

The Scottish Government is able to borrow up to £450m in each year for capital investment, up to a cumulative total of £3 billion. The Budget states that in 2020-21:

In recognition of the Climate Emergency a decision has been taken to borrow the maximum £450 million in capital borrowing to support infrastructure expenditure, rather than the £350 million indicated in the Medium Term Financial Strategy [MTFS].

Borrowing powers were also used in full in 2017-18 and 2019-20, but only £250 million was borrowed in 2018-19. Prior to this, in 2015-16 and 2016-17, ‘notional’ borrowing powers were used to provide budget cover for revenue-financed projects that had to be transferred to the public sector (see section on Revenue financed investment). This ‘notional’ borrowing counts towards the cumulative borrowing limit of £3 billion.

The Scottish Fiscal Commission is required to assess the reasonableness of the Scottish Government’s borrowing plans. They assessed the Scottish Government’s plans as reasonable and compliant with the terms of the fiscal framework. Their assessment shows that, even under a high borrowing scenario through to 2024-25, the Scottish Government will remain within the £3 billion debt cap.

Financial Transactions

The 2020-21 Budget includes £892 million for financial transactions (FTs), including repayments. Net financial transactions (after adjusting for receipts) total £620 million. These FTs relates to Barnett consequentials resulting from a range of UK Government equity/loan finance schemes (primarily the UK housing scheme, Help to Buy). Over the period 2012-13 to 2020-21, financial transactions allocations will total £2.9 billion. The Scottish Government has to use these funds to support equity/loan schemes beyond the public sector, but has some discretion in the exact parameters of those schemes and the areas in which they will be offered. This means that the Scottish Government is not obliged to restrict these schemes to housing-related measures and is able to provide a different mix of equity/loan finance.

For 2020-21, a total of £336.5 million (net) in financial transactions has been allocated to housing-related schemes, including Help to Buy (Scotland). The Scottish Government is also providing equity/loan finance support in areas other than housing. FTs will also be used:

to provide loan funding to small- and medium-sized enterprises

to fund energy efficiency programmes

to support investment in the higher education sector (£55.5 million)

to provide upfront capitalisation for the Scottish National Investment Bank which is planned to become operational in 2020 (£260 million)

Individual tables in the budget document show the following profile for financial transactions. Negative figures indicate portfolio areas where repayments are expected to exceed new FT investment.

| £ million | |

|---|---|

| Health and Sport | 10.0 |

| Communities and Local Government | 338.5 |

| Finance, Economy and Fair Work | 310.1 |

| Education & Skills | 55.0 |

| Transport, Infrastructure and Connectivity | 60.4 |

| Rural Economy | (160.3) |

| Culture, Tourism and External Affairs | 1.1 |

| Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform | (4.0) |

| Social Security and Old People | 9.2 |

| Total | 620.0 |

The Scottish Government will be required to make repayments to HM Treasury in respect of these financial transactions. The repayments will be spread over 30 years, reflecting the fact that the majority of FT allocations relate to long term lending to support house purchases and the construction sector. The repayment schedule is based on the anticipated profile of Scottish Government receipts. The first repayment to HM Treasury of £51 million was scheduled for repayment by March 2020.

Revenue financed projects

In recent years, the Scottish Government has used revenue financing to increase the level of infrastructure investment that can be achieved through the capital budget alone. Revenue financing means that the Scottish Government does not pay the upfront construction costs, but is committed to making annual repayments to the contractor, typically over the course of 25-30 years.

As a result of changed European accounting guidance (European System of Accounts 2010 – ESA10), the budgeting treatment of revenue financed projects has changed. Projects funded via the Non-Profit Distributing (NPD) model are now deemed to be public sector projects and require upfront budget cover to be provided from the capital budget over the construction period of the asset. This compares with the budget treatment for private sector projects, where the costs are treated as revenue costs and are spread over the period (usually 25-30 years) over which the asset is used and maintained. No new NPD projects are currently being considered.

The Scottish Government is proposing to introduce a modified version of the NPD model, known as the ‘Mutual Investment Model’ (MIM). This shares a number of features with NPD but is adjusted so that it meets the requirements for such investment to be treated as private sector projects and therefore paid for out of revenue budgets over a longer timeframe.

The Scottish Government’s Medium Term Financial Strategy1, published in May 2019, stated that:

the use of the MIM model will be reserved for central government assets where access to borrowing is more restricted. The intention would be to deploy other levers first, including the use of capital borrowing in line with our fiscal rules and principles.

This reflects the fact that private financing is likely to be a more expensive option that funding infrastructure through capital grants or capital borrowing. There are no plans to use MIM investment in 2020-21.

Innovative financing

The Growth Accelerator (GA) and Tax Incremental Financing (TIF) are local authority led financing schemes, whereby projects are financed through borrowing in the expectation that future uplifts in local taxation income will fund the repayments. The Scottish Government provides some support to such schemes, as well as to City Region and Regional Growth Deals, totalling £27 million in 2020-21. Within this total, £19 million relates to TIF projects and £8 million to the Edinburgh Growth Accelerator.

Revenue financing and the 5% cap

Annual repayments resulting from revenue financed projects and borrowing come from the Scottish Government’s resource budget. The Scottish Government has committed to spending no more than 5% of its total resource budget (excluding social security) on repayments resulting from revenue financing (which includes NPD/hub, previous PPP contracts, regulatory asset base (RAB) rail investment) and any repayments resulting from borrowing. The budget document indicates that new school ‘Learning Estate Investment Programme’ will use revenue financing, but no further details are given.

Based on current plans, the Scottish Government estimates that it will spend 3.1% of its resource budget on these repayments in 2020-21. Again on the basis of current plans, this is forecast to steadily reduce to around 2.8% in 2025-26.

National Infrastructure Mission

The Scottish Government’s Economic Action Plan 2018-201 announced plans to increase Scotland’s annual infrastructure investment by 1% of (then) GDP between 2019-20 and 2025-26. The 2020-21 Budget defines the baseline at £5,297 million with an ambition to increase annual infrastructure investment to £6.9 billion by 2025-26. In 2020-21, according to budget plans, infrastructure investment will total £6.2 billion. The priorities for investment are set out as follows:

Fostering inclusive growth.

Responding to the climate emergency.

Supporting the development of sustainable places.

The independent Infrastructure Commission recently published its Phase 1: Key findings report2. This focuses on the “what and why” of infrastructure investment and highlighted the need for infrastructure that meets the challenge of delivering inclusive net zero carbon economic growth. The next report – to be published by the end of June 2020 – will look at options for delivering the required infrastructure (the “how”). A refreshed Infrastructure Investment Plan is also expected to be published by the Scottish Government by June 2020.

Local Government

This section of the briefing sets out a high level summary and analysis of the local government budget for 2020-21. The Local Government Finance Circular1, which sets out funding in further detail and individual allocations to local authorities, was published alongside the Budget. A dedicated SPICe briefing setting out the settlement for local authorities in more detail will follow.

Headline figures

The total allocation to local government in the 2020-21 Budget is £10,907.0 million. This is mostly made up of General Revenue Grant (GRG) and Non-Domestic Rates Income (NDRI), with smaller amounts for General Capital Grant and Specific (or ring-fenced) Resource and Capital grants.

Once Revenue funding within other portfolios (but still within the totals in the Finance Circular) is included, the total is £11,335.7 million. Further, once a number of funding streams attached to particular portfolio policy initiatives, but outside the totals in the Circular are included, the total rises to £11,832.5 million.

Within these global headline figures, the breakdown between different interpretations for revenue and capital, and the year to year change, has been subject of much parliamentary debate in recent years. The following sections set out these figures.

Revenue funding

Revenue, or resource, funding, is used by local authorities to deliver services. While local authorities appear to have discretion over much of this side of the budget, some areas of the budget are “ring-fenced” for a specific purpose. As well as these specific, ring-fenced areas, there is also a debate about how much of the “discretionary” budget is actually fully under the control of local government, and how much is allocated to Scottish Government priorities. This is discussed in more detail below, in the section on COSLA’s response.

The Scottish Government guarantees the combined GRG and distributable NDRI figure, approved by Parliament, to each local authority. If NDRI is lower than forecast, this is compensated for by an increase in GRG and vice versa.

This combined GRG+NDRI figure (i.e. the amount of money to deliver services over which local authorities have control) falls slightly in real terms, by 0.3%, or by £29.3 million.

However, once specific, ring fenced resource grants are included, then the combined figure for the resource budget increases by 1.6% in real terms, or by £159.3 million.

In her statement, the Minister stated that the budget provided “a real terms increase in Local Government revenue support.” This was based on comparing the March 2019 local government finance circular figure for “total revenue” to the same figure in the Circular published on the same day as the Budget, and results in a 3% real terms increase, or an increase of £303.2 million.

Capital funding

Alongside the revenue budget, used to pay for public services, local government also receives a capital budget, again made up of general (i.e. discretionary) and specific (i.e. ring-fenced) grants. Overall, the total capital budget sees a decrease in real terms this year, of 31.0%, or by £336.0 million, mostly driven by a decrease in general support for capital.

However, the nature of the capital budget is that it is subject to large changes from year to year as projects and programmes of capital investment start and finish. The Government states that much of this reduction is due to one-off sums for capital in the 2019-20 budget. It is worth noting though that the 2020-21 total capital budget is still substantially lower than the 2018-19 capital budget.

COSLA's response

While acknowledging that there was a “cash increase of £495 million”, in its initial budget response, COSLA stated that “the reality behind this figure unfortunately is quite different” and that in their view there was “a cut to Local Government core budgets of £95 million.” This, COSLA says, is because alongside the £495 milion cash terms increase, there is also £590 million worth of Scottish Government commitments. On capital, again using Scottish Government commitments, COSLA states that in their view, despite stripping out the "one-off sums" referred to above, the reality is a £117 million cash cut in the core capital budget.

In terms of ring-fencing and “protection” of the budget, before the 2020-21 Budget was published, COSLA indicated that in its view, 61% of the 2019-20 Budget was in some way subject to “ring fencing, national policy initiatives and protections in education, health and social care.”

Issues around ring-fencing and the extent to which elements of the budget are “protected” will be explored in more detail in the forthcoming SPICe briefing on the local government budget and allocations to local authorities.

Will these spending or tax proposals change?

With the parliamentary arithmetic as it is, it is likely that the Scottish Government will have to strike a deal to garner sufficient parliamentary support for their spend and tax proposals.

On spending, the political battlegrounds of recent years have centred on the settlement available to Local Government. Whether that happens again this year remains to be seen.

On tax, it is at least possible that these rates and thresholds might change in order to secure parliamentary support, or in response to the UK Budget next month. Scottish income tax policy for 2020-21 has to be confirmed in a ‘Scottish Rate Resolution’ (SRR) before the Budget Bill can pass and Scottish tax rates and bands cannot be changed once the financial year has started.

However, if the Scottish Government feels it needs to respond to the UK policy position on income tax after the Budget Bill is passed, it can propose that the SRR is cancelled and propose a new one, provided it is done before the start of the tax year (i.e. before 6 April). If the Scottish Government feels that anything in the UK Budget has unexpected budgetary implications for Scotland, this can be handled via an in-year budget revision (subordinate legislation subject to scrutiny by the affirmative procedure in the Scottish Parliament).

As mentioned elsewhere in this briefing, the BGAs used to underpin these draft budget proposals for tax and social security are provisional, and based on the OBRs forecasts from March 2019. The Scottish Government has the option of using the updated BGAs when they are presented as part of the UK Budget next month. Should it chose to use these updated BGAs, it will adjust the Scottish budget via an in-year Budget revision during the course of 2020-21.

Climate change and Carbon Assessment

The Climate Change Act 2009 requires the Scottish Government to provide assessments of the impacts on greenhouse gas emissions of activities funded by its budget. The Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) Act 2019 also requires a carbon assessment of the Infrastructure Investment Plan.

Since 2009, eleven high-level carbon assessments of the budget have been published using an Environmentally-extended Input-Output (EIO) model to estimate emissions. This model is normally used to understand the flow of money though the economy. However, the environmentally-extended version averages greenhouse gas effects for 98 industry sectors and converts the financial inputs from the budget into expected greenhouse gas outputs.

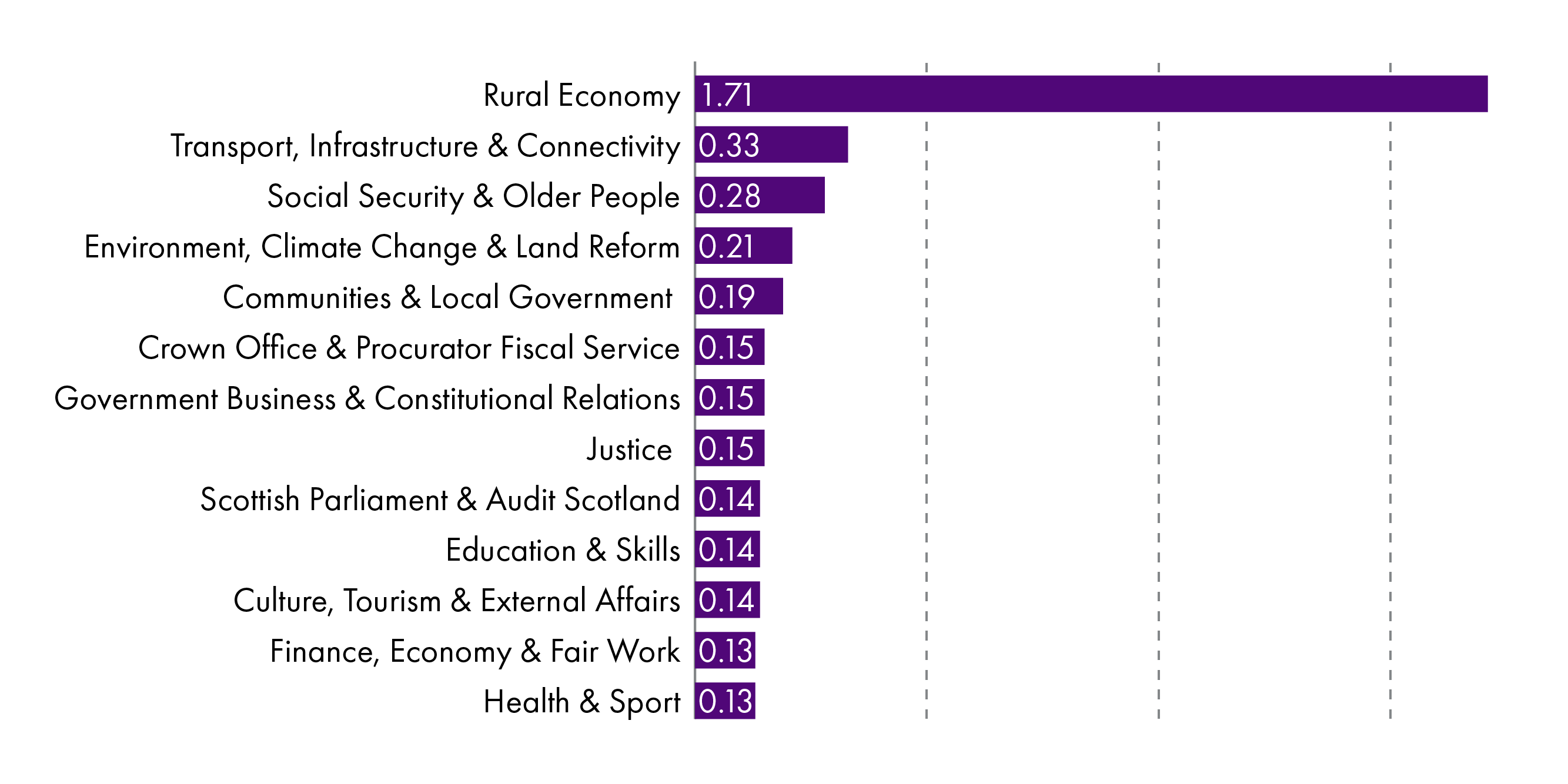

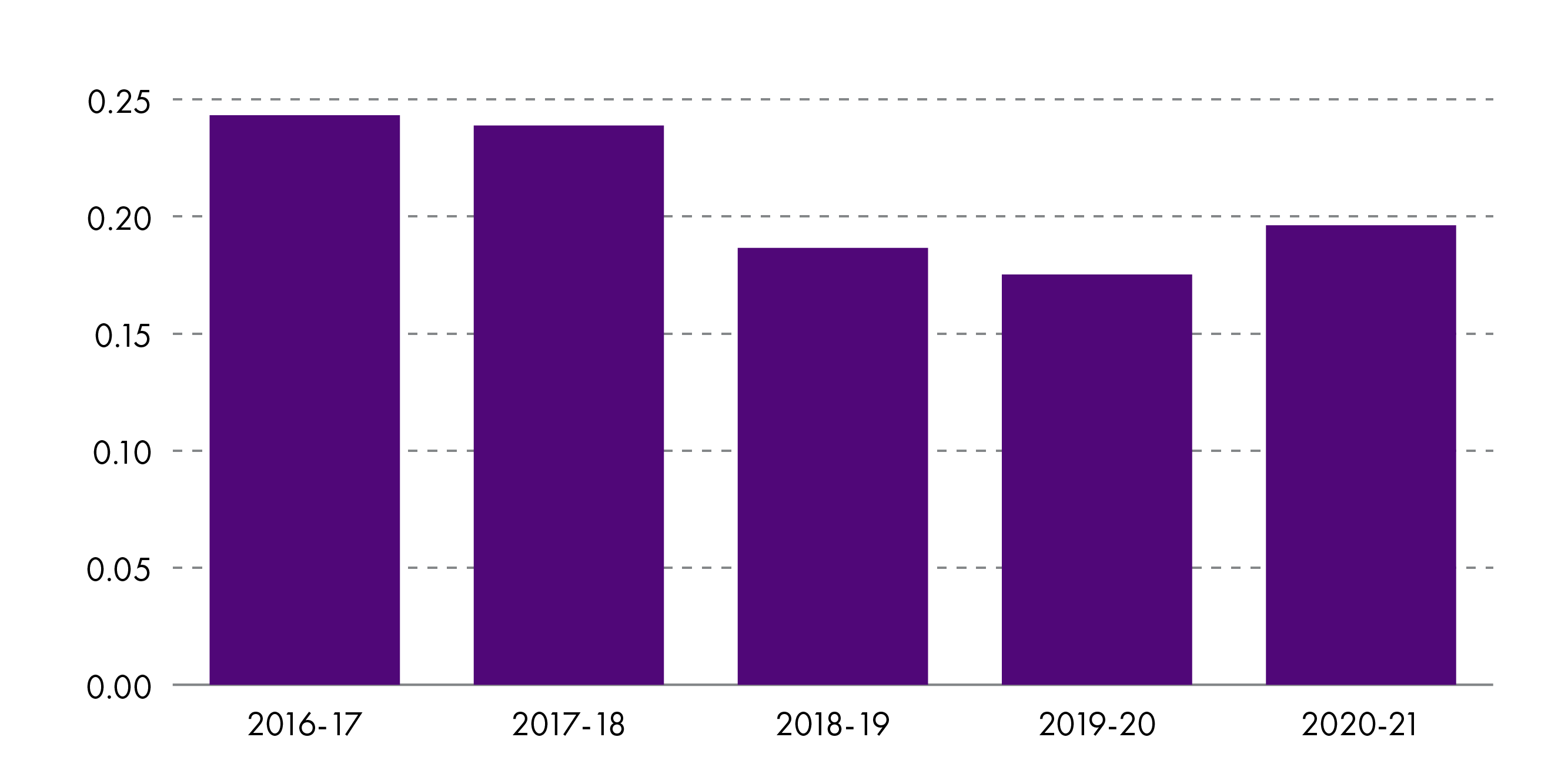

It is estimated that total emissions resulting from the 2020-21 Budget 1will be 9.5 Mt (million tonnes) CO2-equivalent, a 36% increase on 2019-20 (which was estimated to have emissions of 7.0 Mt CO2-equivalent). The Scottish Government explains that this is almost entirely down to EU Common Agricultural Payments and UK Social Security being moved over to the Scottish Government budget this year: “as a result, the greenhouse gas emissions associated with Scottish Government spending have also increased”. Nevertheless, presented as a ratio of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions per £ spend, the 2020-21 budget is more carbon-intensive than the previous year’s (see Figure 13).

The largest emitting budget lines are also, unsurprisingly, the two largest budget areas; health and local government. Between them, these two portfolios are responsible for emissions of 4.1 Mt CO2 equivalent.

However, the area with by far the highest intensity of carbon emissions – i.e. greenhouse gas emissions per £ of spend - is the Rural Economy budget. This budget represents 1.5% of total Scottish Government expenditure, but accounts for 13% of total emissions. This reflects the fact that this budget supports farming activity, which produces methane and nitrous oxide, gases which have a much greater warming impact than carbon dioxide.

Likewise, the Transport, Infrastructure and Connectivity budget accounts for 7% of total SG budget, but associated emissions from this spend accounts for 11% of total emissions. Ferry service support, an element of the Transport budget, is another particularly carbon-intensive area of government spend.

Future funding for infrastructure to support new rail routes, bus services, electric vehicles, walking and cycling remain dwarfed by the commitment to invest £6 billion over the next 10 years in dualling the A9 and A96 trunk roads, alongside other trunk road improvement projects such as the Sheriffhall roundabout flyovers (£120 million) and A7 Maybole bypass (£31.5 million).

This significant trunk road investment appears at odds with the Infrastructure Commission’s recommendations that no net additional capacity be added to the road network and that action needs to be taken to manage demand for road transport.

Figure 13 shows that between 2016-17 and 2019-20 the overall Scottish Budget became less carbon-intensive. However, the 2020-21 estimates show a reversal of this trend, again mainly due to the transfer of farm payments and social security to the Scottish Government budget.

Planned improvements in carbon assessments

It is worth remembering that the current EIO tool does not predict the longer-term outcome of spending decisions (as was highlighted in a recent SPICe blog post). The example given by the Scottish Government is that of road construction: the Carbon Assessment published with the 2020-21 Budget may calculate the carbon emissions associated with the cost of constructing a road, but it does not include carbon associated with the subsequent use of that road – emissions that are “locked-in” to future activity.

The Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee in its 2020/21 budget report supports the publication of Carbon Assessments, however it believes the assessments by themselves do not provide “sufficient information on the carbon impact of the budget”. The Committee also considers that “all new infrastructure must demonstrably fit into a net-zero emissions economy”; therefore “the next infrastructure plan should model or map Scotland’s infrastructure needs in a 2045 net-zero economy and describe a pipeline to get there.”

The Scottish Government’s response notes that “a joint working group between the Scottish Government and the Parliament will be established in February 2020 to review the Budget as it relates to Climate Change. The response goes on to provide further detail on the development of carbon assessments, and notes that it:

[…] is about to undertake new research to explore alternative methodologies to feed into the carbon assessment of the Infrastructure Investment Plan. […]

Our commitment to year-on-year increases in low carbon infrastructure investment demonstrates the Scottish Government’s strong commitment addressing climate change and transitioning to a low carbon economy.

This Scottish Government has so far met this commitment, with an increase in 11 percentage points between 2017-18 and 2019-20.

Budgets and Outcomes

Published in 2017, and accepted by both the Scottish Parliament and Scottish Government, the Budget Process Review Group’s report1 recommended that Parliamentary budget scrutiny should be more outcomes-focussed. The Group suggested the National Performance Framework (NPF) could therefore be “used more widely by Parliament and its committees in evaluating the impact of previous budgets”.

To recap, the Scottish Government’s National Performance Framework consists of eleven National Outcomes each underpinned by a set of National Indicators. These show whether recent performance in these priority areas is improving, maintaining or worsening.