Health and social care integration: spending and performance update

This briefing describes the current performance of health and social care integration authorities, from both a financial and non-financial perspective, reviewing progress since The Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014.

Executive Summary

The Scottish Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014 led to the formation of 31 integration authorities, partnering local authorities and NHS boards across Scotland, by 1st April 20161.

The aim of integration authorities is to improve the quality and consistency of health and social care services delegated to them, with the intention to deliver health and social care in community settings, rather than hospitals, as far as possible1.

NHS and local authority partners delegate budgets to integration authorities so that they can direct spending on delegated services in a way that, over time, achieves the aims of integration.

Integration authorities are expected to deliver financial savings and change the balance of spending on health and social care through achieving the aims of integration. This is set against a backdrop of rising health and social care expenditure, as well as increased Scottish Government commitments to NHS spending3.

Since 2016/17, integration authority annual budgets have totalled almost £9 billion, with little evidence of a shift in spending from hospital to community care over this time.

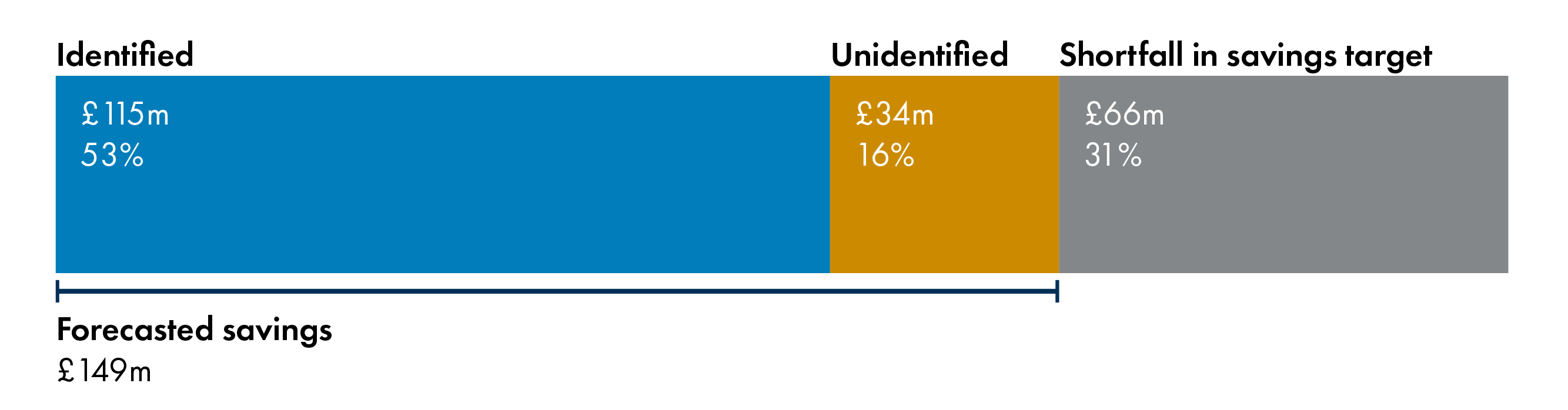

In 2018/19, the savings target set at the start of the year across all integration authorities totalled £215 million. By quarter 3, forecasted savings were £149 million, with some savings yet to be identified.

Issues noted in integration authority budget processes include delays in agreement, lack of transparency, relationship issues, and inability to make medium or long-term plans. There are also reports that, given the rising demand for services, achieving a shift in the balance of care from hospital to community is a difficult task.

In terms of performance against the six Ministerial Strategic Group indicators, there has been a positive direction of change over time for three indicators, relating to decreases in the number of unscheduled hospital bed days and increases in the proportion of the last six months of life spent in the community, as well as the percentage of people aged 65 or over living in non-hospital settings. The other three indicators showed a negative direction of change, with an increase in the number of emergency admissions, A&E admissions, and number of delayed discharge bed days.

Performance in individual integration authorities varies, both when comparing recent data across integration authorities, as well as comparing changes over time within integration authorities. This variability in success illustrates the need to share good practice amongst integration authorities.

There are concerns that the six Ministerial Strategic Group indicators are mainly hospital-based measures that have driven the focus towards reducing hospital usage, without consideration of patient-centred outcomes. Additionally, data on performance are not consistently, and publicly, available across integration authorities.

There are reported issues with public and third sector involvement with integration. This may prevent optimal performance of integration authorities and reduce focus on performance indicators that truly matter to the public.

To address these concerns, the Ministerial Strategic Group and others are driving efforts to increase data availability, alongside improved public and third sector engagement with integration authorities, and efforts to improve leadership and relationships within and between integration authorities. This is hoped to enable identification and evaluation of patient-centred outcomes, as well as to increase sharing of good practice to reduce variability in performance across integration authorities.

The Scottish Ambulance image on the cover is originally by the Scottish Government and available under a CC BY-NC 2.0 license.

Context

Purpose of this briefing

Health and social care integration in Scotland is progressing1; Audit Scotland cited a number of good practice case studies since The Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014 in their 2018 report, Health and social care integration: Update on progress. However, they also identified a number of barriers. These were consistent with many of the issues identified in separate reports by the King's Fund in 20182, The Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland1, and the Health and Sport Committee4.

Audit Scotland identified six key features that support integration in their report:

commitment to collaborative leadership and building relationships

effective strategic planning for improvement

integrated finances and financial planning

agreed governance and accountability arrangements

ability and willingness to share information

meaningful and sustained engagement.

At a health debate in the Scottish Parliament on 2 May 2018, the then Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport tasked the Ministerial Strategic Group for Health and Community Care with reviewing progress by integration authorities and sharing actions from this review with the Health and Sport committee of the Scottish Parliament. The Ministerial Strategic Group published their review in February 2019. In this, they accepted all recommendations from the Audit Scotland report and set out 25 proposals to tackle concerns raised in the Audit Scotland report5.

This briefing covers two areas of integration where concerns have been identified by the Ministerial Strategic Group and others; spending and performance. In relation to spending, the Health and Sport committee have consistently noted issues with the transparency in, and use of, integration authority budgets4.

In relation to performance, monitoring outcomes is key to determining the impact of integration and highlighting key areas of weakness and strength within and across Scotland. This was reinforced in a series of qualitative interviews and focus groups with those involved in integration of health and social care in Scotland, where participants highlighted that a key aim of integration is to improve patient experience and outcomes. Sharing good practice was highlighted as a key requirement of integration, which requires high quality data sources to allow reporting on performance7.

This briefing describes the context of current and planned health and social care spending in Scotland, as outlined by the Scottish Government in their Medium Term Health and Social Care Financial Framework. It also outlines finances and performance relating to health and social care integration in Scotland after inception of the Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014.

History and current policy on health and social care integration in Scotland

A number of policies have been introduced in Scotland from 1999 onwards (and across the UK prior to this) aiming to increase integration of health and social care services.

Drivers for these policies include both past and predicted changes in health and social care pressures due to rising costs and demands. Evidence suggests that effective integrated services provide individual and societal benefits for health and financial outcomes, amongst others1.

The history and current policy on integrated care in Scotland can be found in previous SPICe briefings: 12/48 Integration of Health and Social Care: International Comparisons2, 13/50 Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Bill3, and 16/70 Integration of Health and Social Care4.

The Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014 required local authorities and NHS boards to form partnerships called integration authorities by 1st April 2016. The ambition of this policy was:

To improve the quality and consistency of services for patients, carers, service users and their families; to provide seamless, joined up quality health and social care services in order to care for people in their homes or a homely setting where it is safe to do so; and to ensure resources are used effectively and efficiently to deliver services that meet the increasing number of people with longer term and often complex needs, many of whom are older.

Scottish Government. (2014). Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014. Retrieved from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2014/9/contents/enacted [accessed 21 June 2019]

Integration authority organisation and responsibilities

The Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014 required creation of public organisations to enable partnerships between the 14 territorial NHS boards and 32 local authorities in Scotland.

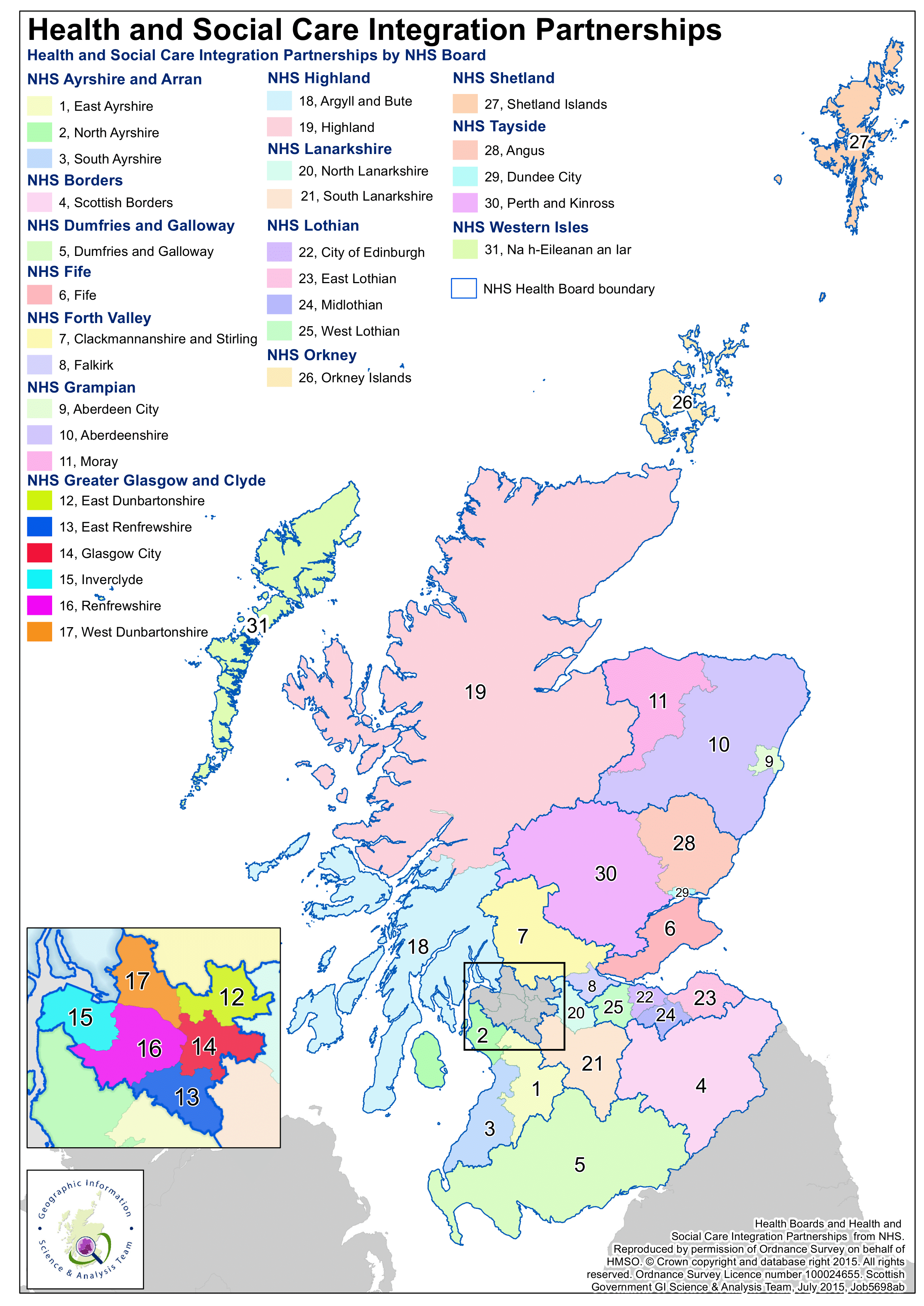

There are 31 of these organisations, called integration authorities, across Scotland. Integration authorities usually cover a single local authority, except for Stirling and Clackmannanshire, which combines the two local authorities of Stirling and Clackmannanshire. Figure 1 highlights the boundaries of each integration authority and alignment with NHS boards. Integration authorities are required to divide their area into at least two smaller ‘localities’. This should enable integration to be designed and delivered with the specific features of a locality in mind.

A locality is defined in the Act as a smaller area within the borders of an Integration Authority. The purpose of creating localities is not to draw lines on a map. Their purpose is to provide an organisational mechanism for local leadership of service planning, to be fed upwards into the Integration Authority's strategic commissioning plan.

Scottish Government. (2015, July 3). Localities Guidance. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/localities-guidance/pages/6/ [accessed 21 June 2019]

Integration authorities function under one of two models:

Integration joint board: a joint board is set up with representatives from the local authority, NHS board, and elsewhere (e.g. service users and third sector organisations). The integration joint board is responsible for planning and resourcing service provision for delegated services.

Lead agency: the NHS board or local authority takes the lead in planning and delivering delegated services. Currently, this model is only used in the Highlands, where NHS Highland is the lead agency for adult health and care services and Highland Council is the lead agency for children's community health and social care services.

In both models, certain functions must be delegated to the integration authority, so that it is in control of the governance, planning, and resourcing of specified services. The "minimum delegated services" are described in the following regulations: The Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Prescribed Health Board Functions) (Scotland) Regulations 2014 and The Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Prescribed Local Authority Functions etc.) (Scotland) Regulations 2014 . The "minimum delegated services" cover adult social care, primary and community health care, and unscheduled hospital care.

Unscheduled hospital care is defined as hospital specialisms where at least 85% of care is unplanned. This definition covers:

Accident and emergency.

General medicine.

Geriatric medicine.

GP other than obstetrics.

Palliative medicine.

General psychiatry.

Learning disability.

Respiratory medicine.

Psychiatry of old age.

Rehabilitation medicine.

Other functions can also be delegated to the integration authorities, with agreement of the NHS board and local authority, such as children’s health and social care services, or criminal justice social work. Most integration authorities are responsible for more than the minimum scope of delegated services3.

The role of the integration authorities is to plan delivery of services in delegated areas and identify methods of improving the quality and consistency of their delegated functions that ensure seamless, joined up care services. Where possible, the intention is that these services should be shifted towards a homely setting rather than a hospital setting, in line with the Scottish Government's 2020 vision.

Each integration authority has developed a strategic commissioning plan, outlining how they will plan and deliver services over the medium term. This should result in written directions from the integration authorities to one or both of their NHS Board and Local Authority partners for each delegated service (in the case of the lead agency model, the integration authority may issue directions or carry out functions itself). Planning should involve stakeholders in a co-production approach4.

Health and social care integration funding

In all integration authorities except the Highlands (which follows the Lead Agency model), NHS boards and local authorities delegate budgets to the integration joint board. The delegated amount is based on which functions are delegated to the integration authority and should be agreed between the integration authority, NHS board, and local authority.

Integration authorities do not hold any money themselves, but they do direct how it is spent. To ensure transparency and accountability, integration authorities publish annual financial reports with their budgets and audited accounts. They must also produce financial performance reports throughout the year, containing information on current and forecasted spending in relation to their budget. Full guidance on the finances of integration authorities has been provided by the Scottish Government.

Health and social care integration performance

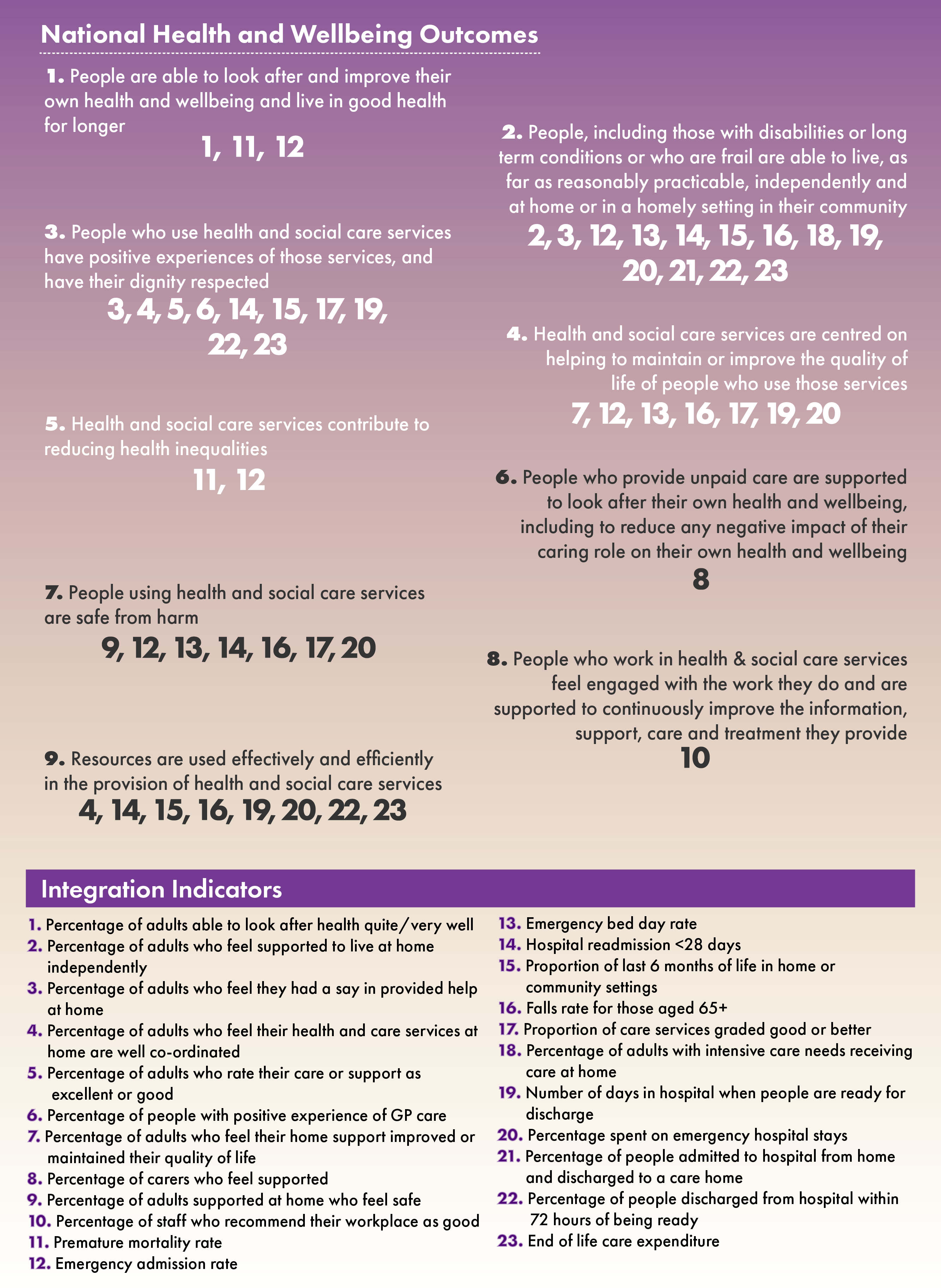

Integration authorities must carry out strategic planning to set their own specific objectives in relation to the wider objectives of integration, as defined by nine national health and wellbeing outcomes specified by the Scottish Government at the time of the 2014 legislation. These are supported by a core set of 23 integration indicators as illustrated in Figure 2.

The Scottish Government's National Performance Framework also lists a number of National Outcomes to work towards, several of which relate to areas affected by integration. The National Performance Framework Outcomes are not directly comparable to the national health and wellbeing outcomes or integration indicators though there is substantial crossover, for example in aiming to reduce inequalities and improve people's health and wellbeing.

Alongside these outcome indicators, the Ministerial Strategic Group for Health and Community Care defined six key indicators of integration authorities’ performance in 2017 that they monitor quarterly. The Ministerial Strategic Group is composed of leaders from health and social care and is tasked with providing leadership and direction on matters relating to health and social care. Their indicators were selected to reflect commitments in the delivery plan for health and social care, as well as on the basis of readily available data to reduce the burden of data collection:

Number of emergency admissions.

Number of unscheduled hospital bed days.

Number of accident and emergency (A&E) attendances.

Number of delayed discharge bed days.

Percentage of last six months of life spent in the community.

Percentage of population residing in non-hospital setting for all people aged 65+.

Some of these are directly comparable to the integration indicators in Figure 2 (emergency admission rate, unscheduled/emergency hospital bed days, delayed discharge bed days, and percentage of end of life spent at home). However, the Ministerial Strategic Group indicators are nearly all hospital-based quantitative measures and do not cover the qualitative and patient-centred aspects included in the wider set of integration indicators.

Integration authorities are required to publish annual performance reports on their specified outcomes and how these relate to their budgets as set out in Scottish Government guidance on performance reports.

Health and social care spending

Current health and social care spending

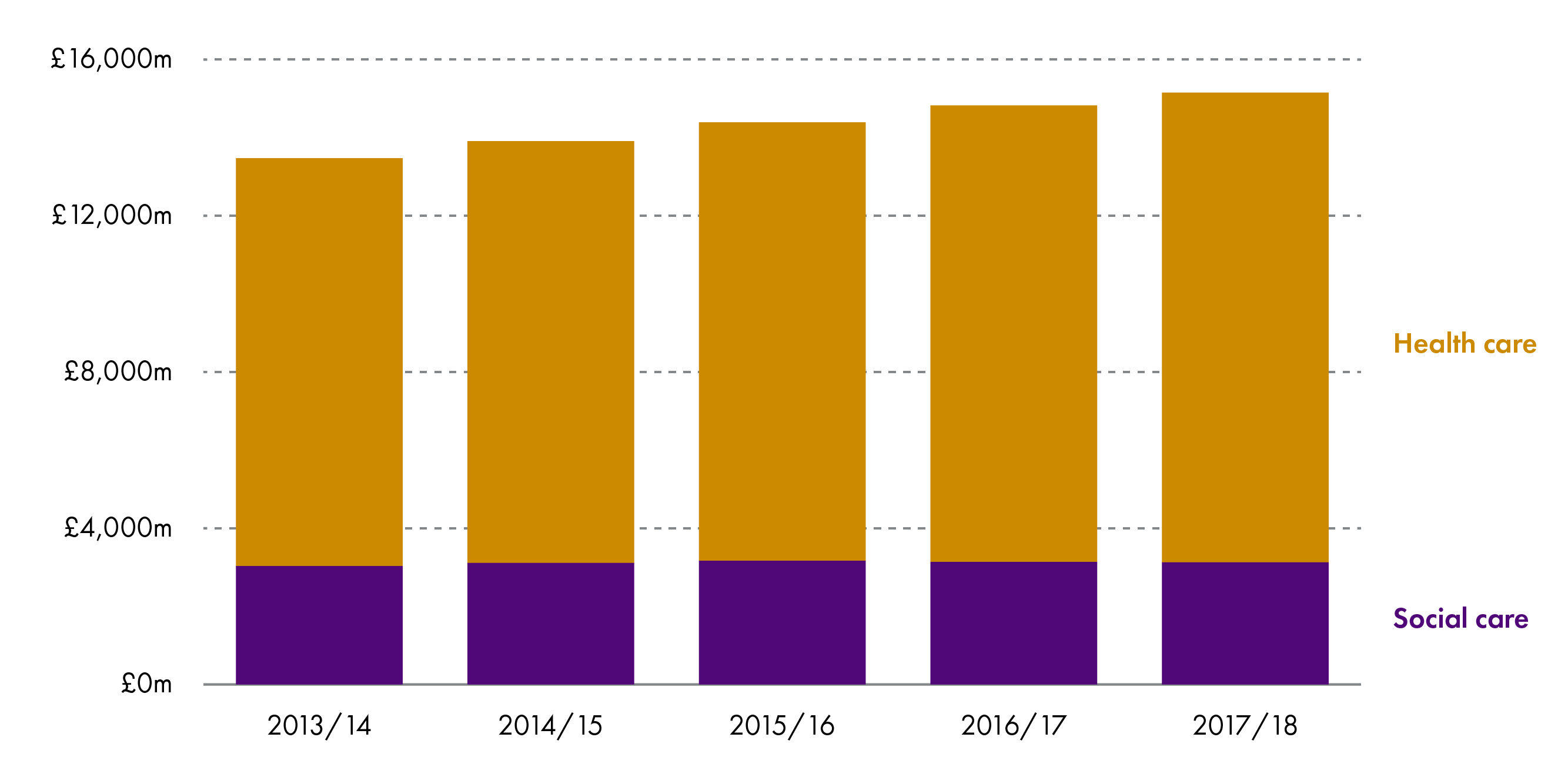

All figures in this briefing are in cash terms, i.e. without adjusting for inflation. Sources of data are described in Annex A. Operating costs for the Scottish NHS Health Service totalled £12.0 billion in 2017/18 (Figure 3). Costs for the 14 territorial NHS health boards, State Hospital, and the Golden Jubilee Hospital are covered in this figure. This includes all NHS services provided by these boards, whether or not these were delegated to integration authorities. Since 2013/14, costs have increased by 3-4% yearly1.

In terms of social care, local government net revenue expenditure was £3.1 billion in 2017/18. As with health service costs, this includes all relevant local authority social care services, whether or not these were delegated to integration authorities. Social care expenditure has remained fairly constant in cash terms across time (Figure 3)2.

The amount of health and social care spending directed by integration authorities is described in the health and social care integration reported spending section.

NHS health service operating costs can be divided to three sectors:

hospital: for services provided in hospitals, including community hospitals

family health: for services provided by GPs and NHS dentist optician, and pharmacy services

community: for services delivered out of a hospital but not covered under family health, such as home visits and screening.

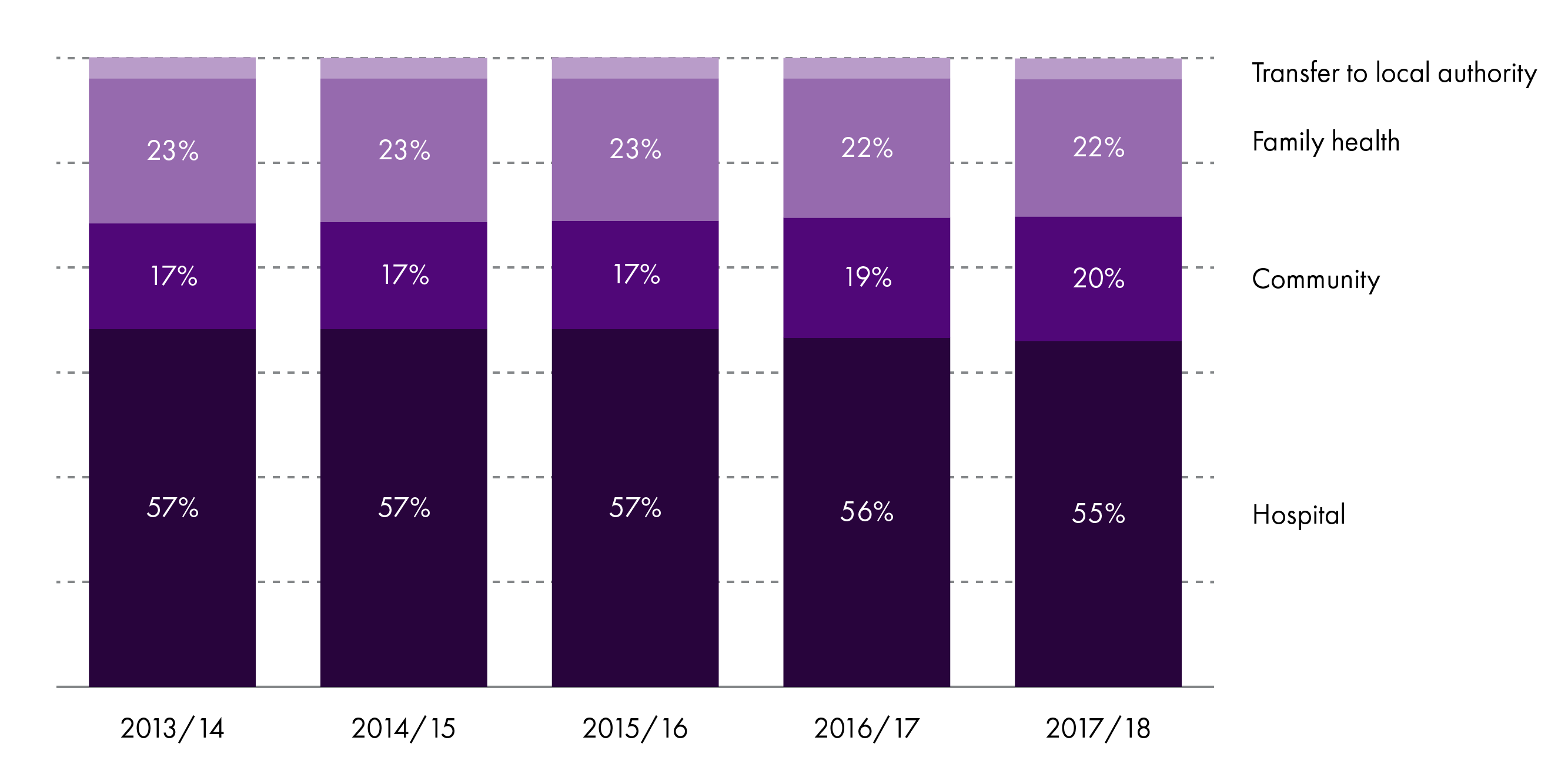

The majority of health expenditure between 2013 and 2018 was in the hospital sector, covering £6.6 billion (55% of total health service costs) in 2017/18. Less money is spent on the family health and community sectors, with these areas covering approximately £2.6 billion (22%) and £2.4 billion (20%) of costs in 2017/18, respectively. The remaining £0.4 billion (3%) of health service operating costs related to transfers to local authorities in this year. Since 2013/14, there has been a small decline in the proportion spent on the hospital and family health sectors and a higher proportion spent on the community sector. The change since 2016/17 may reflect creation of the integration authorities, who were tasked with shifting the balance of care from the hospital to community sector (Figure 4)1.

Future health and social care spending

The demands on and costs of health and social care are predicted to rise over time due to12:

price reasons: inflation and related factors that influence the cost of medicine, equipment, and staff

demographic reasons: reflecting expected changes in the population including the growth in the elderly population. Estimates in 2017 suggested that the Scottish population aged 75 years or over will rise by 27% over the next 10 years, and by 79% over the next 25 years3. The number of people living with chronic diseases, and specifically with multiple chronic diseases, is also expected to rise considerably

non-demographic reasons: including the availability of new drugs and technologies for health and social care, as well as increased public expectations.

In May 2018, the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the Health Foundation forecasted that UK spending on healthcare would need to increase by 3.3% in real terms over the next 15 years to maintain current provisions, and by 3.9% to account for the above factors1.

After this report, the Scottish Government published the Medium Term Health and Social Care Financial Framework. This commits to increased NHS spending of £2 billion in 2021/22 versus 2016/17, consisting of:

£1.5 billion to maintain baseline allocations to the NHS boards and provide additional funding to support integration authorities in shifting the balance of care from hospital to community care

£0.5 billion directed to primary care .

The Scottish Government also committed to increasing the share of NHS spending on mental health, primary, community, and social care in each year to 2021. As well as this, they have committed to a change in the balance of expenditure so that, over the next 5 years, hospital expenditure accounts for less than 50% of frontline NHS expenditure. Frontline expenditure includes the 14 territorial NHS Boards, as well as NHS24, the Golden Jubilee Hospital, the State Hospital and the Scottish Ambulance Service. In 2016/17, hospital expenditure accounted for 50.9% of frontline expenditure2.

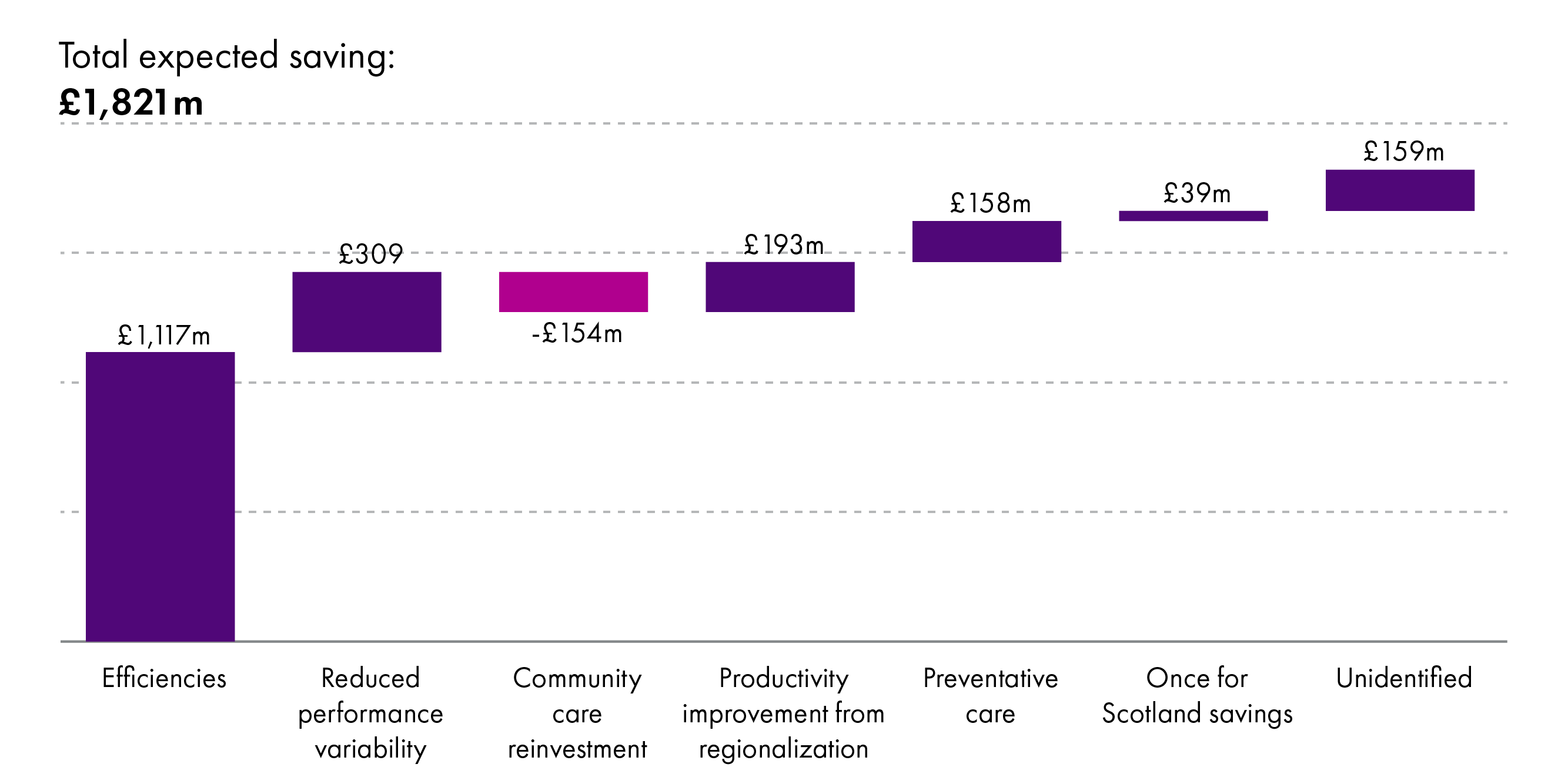

If nothing changes, then to meet these commitments and account for predicted increases in costs, the Scottish Government expect total health and social care expenditure to rise to £20.6 billion in 2023/24, from £14.7 billion in 2016/17. However, in their forecasted spending, the Scottish Government have assumed that savings can be made between 2016/17 and 2023/24 totalling £1.8 billion. To achieve these savings, the Scottish Government estimate that there will be (Figure 5)2:

a 1% efficiency saving in health (£896 million) and social care (£221 million) expenditure

£155 million savings from integration authorities achieving their aims of shifting the balance of care from hospital to community care. This expects total hospital savings of £309 million, with £154 million reinvested to community services. Savings are expected from reduced variation between integration authorities in A&E attendance rates, outpatient follow up rates, and hospital inpatient lengths of stay

£193 million savings from regional improvement to reduce variability in performance across Scotland

£158 million savings from preventative care work

£39 million savings from the "Once for Scotland" approach discussed in the 2016 Scottish Government Health and Social Care Delivery Plan

a residual £159 million in savings yet to be identified.

If these savings are achieved, Scottish health and social care expenditure is estimated to be approximately £18.8 billion in 2023/24. This includes the Scottish Government commitment to a £2 billion increase in spending2.

Integration authority reported spending

Accessing timely, consistent, and comparable budget information for integration authorities is challenging. Progress has been made over time, with integration authorities now providing quarterly data reports to the Scottish Government that are made publicly available. At the time of reporting, data up to quarter 3 2018/19 were available, along with opening budgets for 2019/20.

As far as possible, all the information reported in this briefing is on a comparable basis. However, there may be some reporting differences between integration authorities, particularly in respect of set aside budgets (which are discussed in detail below) and whether these are included in the total budget and NHS allocations. Further information on data sources is available in Annex A.

How spending works

As set out in the Context section, integration authority budgets are made up from the NHS health and local authority social care budgets. They consist of two elements, which may vary in size and scope depending on the functions delegated to the integration authority:

social care

health care (including primary and community health, as well as relevant hospital services).

To set integration authority budgets, the integration authority, NHS, and local authority partners work together to determine how much is required to deliver the delegated services and how much each partner will contribute to these identified costs. This budget is then directed by the integration authority.

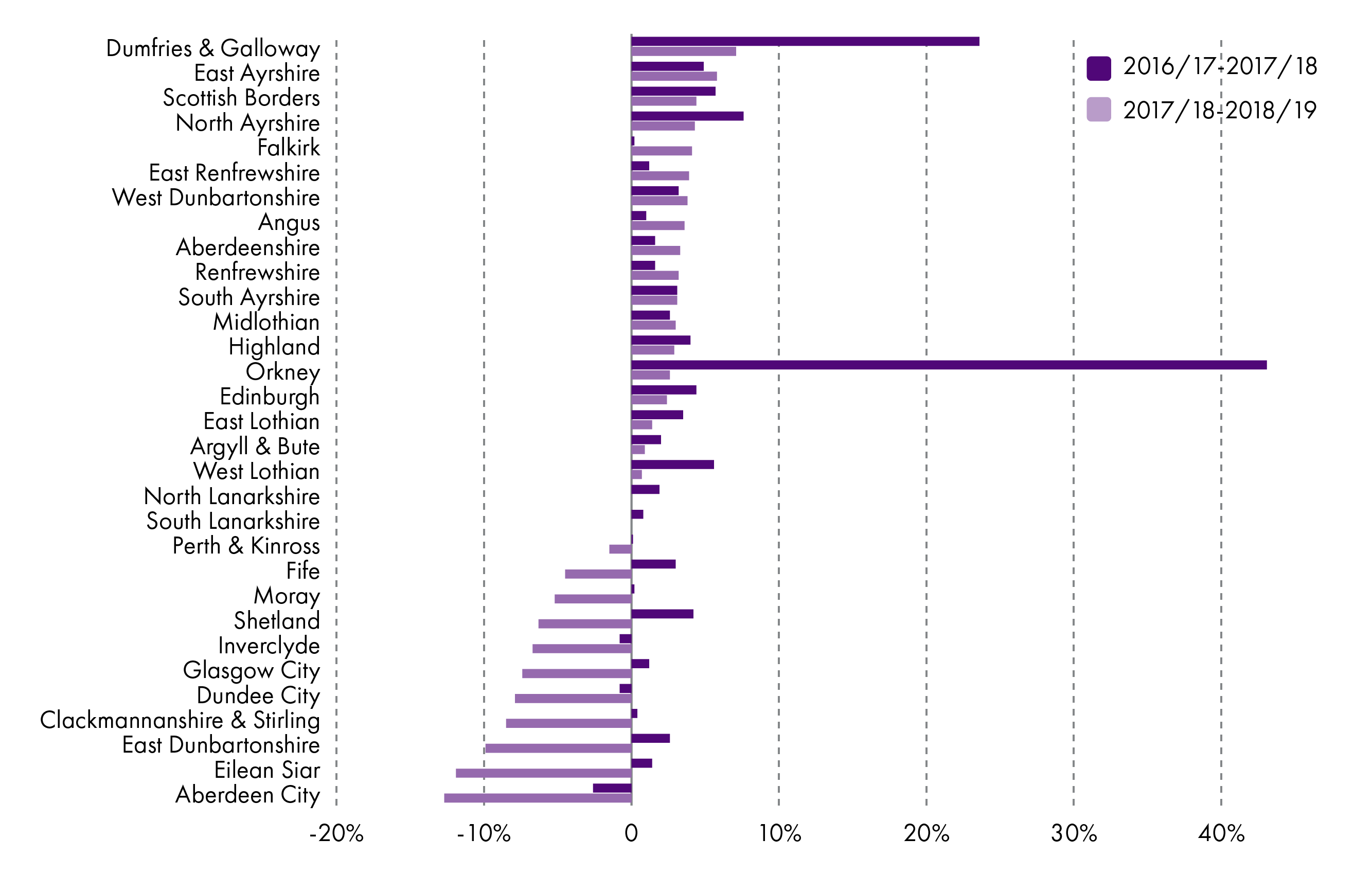

Total budget

In 2016/17, integration authority budgets by the end of the year, accounting for in-year changes, totalled £8,677 million. This figure rose to £8,943 million in 2017/18, a 3% increase1. This increase is in line with the reported increase in overall health and social care expenditure across these years and reflects around 59% of total health and social care expenditure. By June 5th 2019, the total 2018/19 budget for integration authorities was estimated as £8,866 million, a 1% decrease from 2017/182. This figure is expected to rise after final updates and auditing of accounts. The changes in budgets across time may have a number of causes, such as achieved savings, funding pressures, increases in funding from partners, and changes in delegated services or in the coverage of financial reporting.

The opening budget for 2019/20 totals £8,801 million2. This is expected to rise over the year as a result of in-year budget allocations and other factors, so is not directly comparable to the previous end of year figures. Compared to the 2018/19 opening budget, there has been a 4% increase (the 2018/19 opening budget was £8,462 million)4.

In terms of individual integration authorities, three reported decreases in their budgets from 2016/17 to 2017/18 (Aberdeen City, Dundee City, Inverclyde). The remaining 28 integration authorities increased their budgets between these years 1.

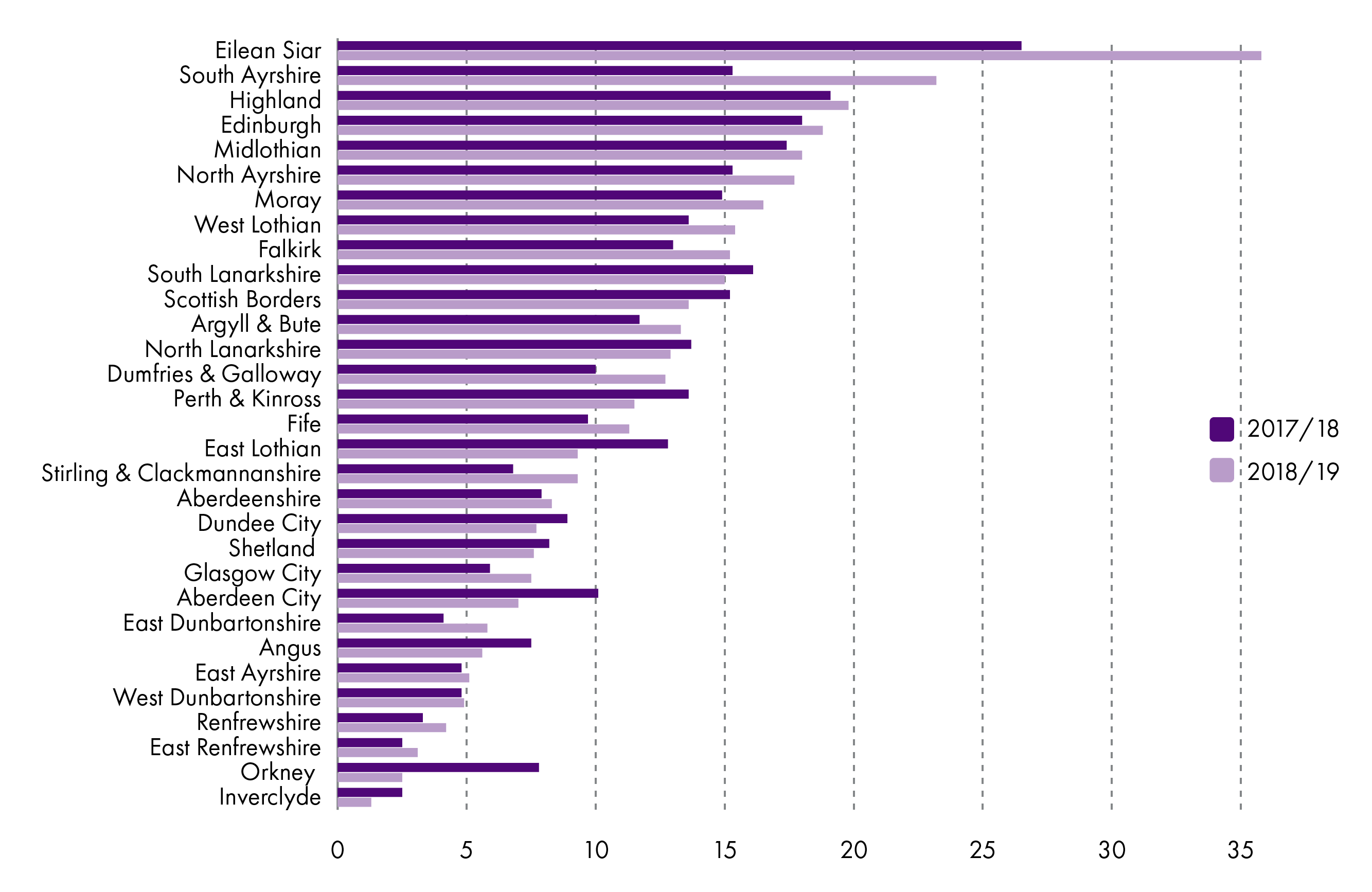

In comparison, more integration authorities (11 rather than 3) decreased their budgets between 2017/18 and 2018/19. Increases in budgets over these years were reported by 18 integration authorities, with two reporting no appreciable changes2 (Figure 6). Again, these changes may relate to achieved savings, funding pressures, increases in funding from partners, and changes in delegated services or in the coverage of financial reporting.

Both Orkney and Dumfries and Galloway reported large increases in their budgets over 2016/17-2017/18. In Orkney, this mainly reflected the fact that prescribing services were only included in the integration authority budget from 2017/18 onwards. In Dumfries and Galloway, the increase was attributed to the opening of a new hospital in 2017/18 (and associated double running costs), as well as a transfer of certain services from the NHS board to the integration authority, and general uplift in pay and prices.

Proportion of funding from the NHS

Funding from NHS boards to the integration authorities totalled £5,653 million in 2016/17, £5,888 million in 2017/18, and £5,734 million in 2018/19 (excluding the Highland integration authority as data were not available on this integration authority for all years). This represents approximately 65% of the total integration authority budget.

In individual integration authorities, NHS allocation to the total budget represented 49-78% of the total budget in 2016/17, 57-83% in 2017/18, and 49-81% in 2018/1912. Part of the variability across integration authorities is because of the difference in functions delegated to the integration authorities.

For the 2019/20 planned budget, NHS allocation is currently £5,468 million, 62% of the total budget. This reflects 33-79% of each integration authorities’ budget1.

Spending by sector

Spending by integration authorities can be divided into four sectors. In 2018/19, spending on these sectors was1:

hospital (18%)

community and family health (37%)

prescribing (12%)

social care (33%).

The proportion of spending on each sector has changed by less than 1 percentage point since 2016/17. Integration authorities should be aiming to shift spending from the hospital to the community and social care sectors. The lack of shift in spending may reflect the complexity in shifting use of services as well as the rise in demand and cost of health care services forecasted by the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the Health Foundation.

Additionally, shifting use of services requires public, and professional, acceptance and confidence in community services. This necessitates public engagement with the work of integration authorities and may take time to develop. As Eddie Fraser, Chief Officer of the East Ayrshire Integration Joint Board, stated:

If someone just says that we should shut 1,000 acute hospital beds and do something differently, that will not be well received. We need to give evidence that there is a different and better way of doing things for the quarter to third of patients who are in hospitals and who do not need to be there.

Health and Sport Committee 21 May 2019 [Draft], Eddie Fraser, contrib. 82, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12120&c=2179011

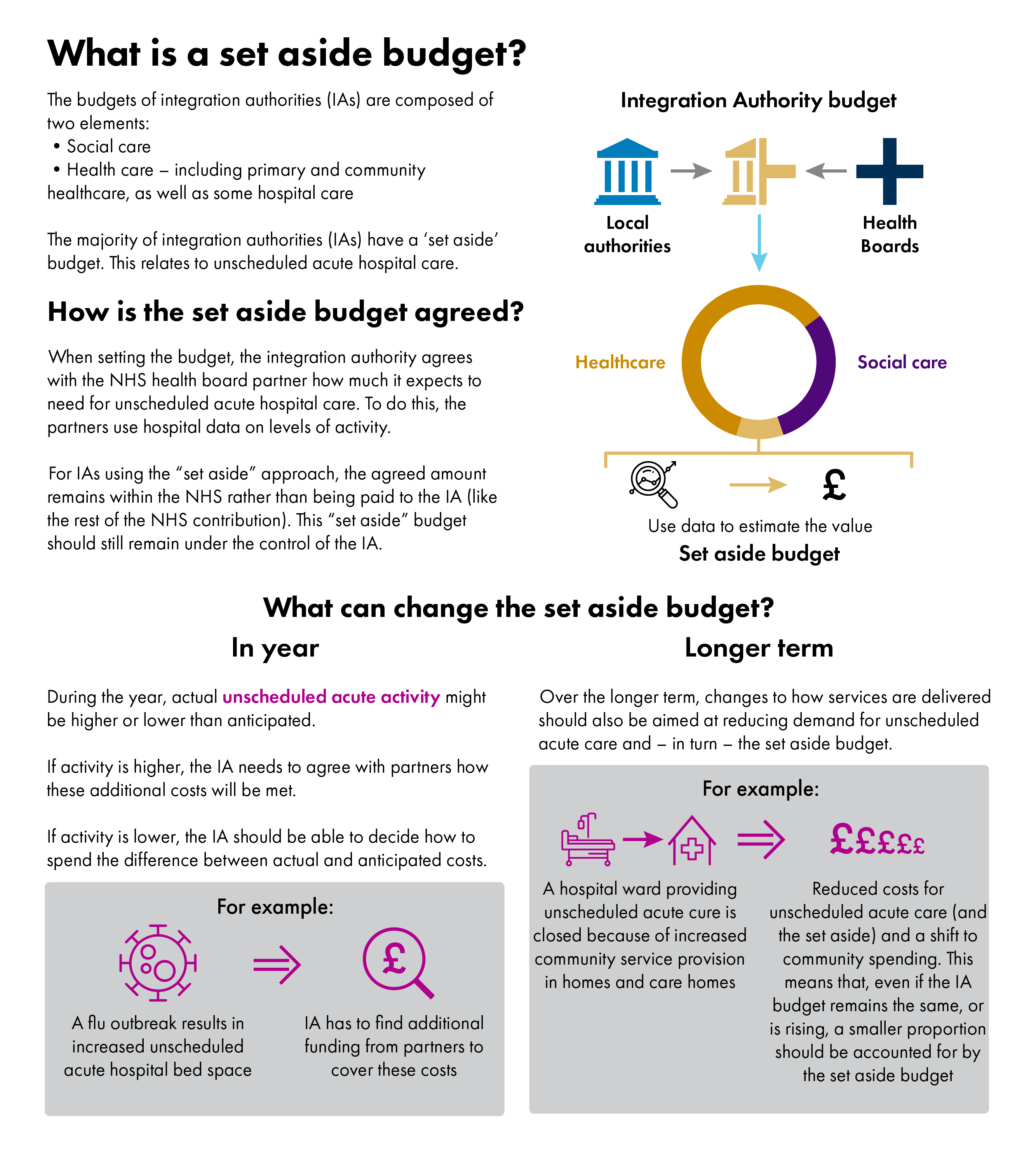

Financial reporting by integration authorities

A number of issues have been reported relating to spending by integration authorities. The Health and Sport Committee noted that there are delays in budget agreements, a lack of transparency, and a lack of effective control over the set aside budget (Figure 7)1. In 2018, Audit Scotland noted:

It is not easy to set out the overall financial position of integration authorities. This is due to several factors, including the use of additional money from partner organisations, planned and unplanned use of reserves, late allocations of money and delays in planned expenditure. This makes it difficult for the public and those working in the system to understand the underlying financial position.

Audit Scotland. (2018, November). Health and social care integration Update on progress. Retrieved from http://audit-scotland.gov.uk/uploads/docs/report/2018/nr_181115_health_socialcare_update.pdf [accessed 3 May 2019]

Members of integration authorities attribute the delays in budget agreements and lack of transparency to relationships between integration authority partners, as well as differences in financial organisation and timelines3.

The Ministerial Strategic Group for Health and Community Care have laid out proposals for improving the budgeting of integration authorities based on the reported issues, including improving communication, leadership, and relationships between integration authority partners4. Alongside this, from October 2018, NHS boards are required to set out finance and improvement plans that break even over a three-year period rather than the one-year period in previous years, which may help with longer term planning and to cope with unexpected funding pressures5.

There has been a positive response to this from many integration authorities. Sandra Ross, Chief Officer of the Aberdeen City integration joint board, stated:

Three-year planning would allow us to move more into the prevention agenda, which would have an impact, particularly as demographics and other things are shifting. A more committed and well-understood direction of spend would allow us to shift the balance.

Health and Sport Committee 04 June 2019 [Draft], Sandra Ross, contrib. 13, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12172&c=2183816

Set aside budgets

The set aside budget reflects the integration authority budget covering unscheduled hospital care. This can be retained by the NHS board and “set aside” for direction by the integration authority instead of being included in the budget transferred to the integration authority. An explanation of the set aside budget, and how it should work, is illustrated in Figure 7. The integration authority should always direct spending on delegated unscheduled inpatient hospital services; “set aside” simply refers to where this part of the budget is held (by the NHS or by the integration authority).

The initial set aside budget reflects estimated spending by each integration authority on unscheduled care. Integration authorities should then develop strategic and financial plans across the whole care pathway that set out proposed changes to reduce spending on these services and redirect spending to community services1. Across time, this should mean that spending of integration authorities changes to reflect a shift from hospital to community care, resulting in a decreased “set aside” budget as a proportion of the total integration authority budget. This is also reflected in the expected savings set out in the medium term financial framework.

Additionally, set aside spending may vary from the budget during the year based on whether use of unscheduled care is higher or lower than expected, which may result in a release of funding (if there is underspending) for reinvestment to community care, or additional funding requirements if there is overspending. The case study later in this briefing describes an example in South Lanarkshire where a shift in care has been achieved.

Savings

Another issue relates to the expected savings in the Scottish Government's Medium Term Health and Social Care Financial Framework1. Integration authorities are expected to deliver savings by increasing health and social care service efficiencies as well as transforming services to shift from hospital to community care. Recent qualitative research highlighted concerns over the amount of savings expected, particularly in the current scenario of rising service demand. Research participants highlighted their concerns that this may lead to a focus on cost-cutting and reduced services, rather than efforts to truly transform services2. Apprehension over whether these expected savings are realistic were echoed in the Health and Sport Committee's 2020-21 pre-budget scrutiny3 and by Eddie Fraser, Chief Officer of the East Ayrshire Integration Joint Board:

The frank answer to the question whether we can continue to make efficiencies all the time has to be no. At some point, we have to ensure that we have the full funding to deliver what we do. That is where transformation and/or additional funding comes in. Overall transformation will happen only if there is money that can be moved from one part of the business to another. I am not clear, for instance, whether the scale of funding that is needed to deliver for our local communities is available for transfer from the acute service. The number of beds that we will need to close in the acute estate to deliver an effective community estate has not been evidenced. We can be efficient and can consider scaling back, but we need to listen and we need to think about how we can actually deliver services. It cannot all be about efficiencies—some of it will be about transformation, and there will need to be additionality.

Health and Sport Committee 21 May 2019 [Draft], Eddie Fraser, contrib. 60, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12120&c=2178989

The medium term health and social care financial framework expects integration authorities to achieve savings by increasing health and social care expenditure efficiencies, as well as shifting care from hospital to community settings. From 2016/17 to 2023/24, these savings are expected to total £155 million for work to shift the balance of care from hospital to community (consisting of £309 million expected savings from reduced variation in rates of hospital care minus £154 million for reinvestment to community care). In terms of efficiencies, integration authority savings should also contribute to the £1,117 million expected efficiency savings across all health and social care services over the period 2016/17 to 2023/241.

In 2018/19, the integration authority budgets set at the start of the year included a savings target of £215 million. By the end of quarter 3 (data were unavailable up to the year end), forecasted savings were £149 million, a shortfall of 31% of the target. Only eight integration authorities were planning to achieve their targeted savings and unidentified savings were reported by six integration authorities. Unidentified savings were approximately £34 million, meaning there were no plans in place for achieving some of the forecasted savings. If none of these unidentified savings are achieved, this would mean achieved savings of £115 million, 53% of the target set at the start of the year (Figure 9). Part of the difference in forecasted versus targeted savings related to funding pressures during the financial year. These related to staffing, prescribing, demographic growth, price increases, and other sources6.

As end of year figures were unavailable at the time of reporting, there may be further changes that affect both the identified and achieved savings in relation to the target for 2018/19.

Health and social care integration performance

Reported performance issues

Annual performance reports

Integration authorities publish annual performance reports on their outcomes. These should report outcomes against budgets as set out in Scottish Government guidance on performance reports. To date, these reports have varied in content and structure, including whether they report performance against the nine health and wellbeing outcomes, 23 integration indicators (see Figure 1), six Ministerial Strategic Group for Health and Community Care indicators, or other measures relating to the specific objectives of the integration authority.

A benefit of this variability in reporting is that integration authorities report against measures that are important for them. On the other hand, it means that reports are not consistent, which hinders evaluation of the overall success of the integration authorities or benchmarking performance of different integration authorities. Additionally, no integration authorities report outcomes against their budget. Because of this, it is difficult to evaluate good practice and ensure that this can be adapted to other areas, as well as to identify how the budgets of integration authorities relate to performance12. Compounding the problem of benchmarking and sharing good practice, there is a lack of research into integration initiatives to evaluate and identify models of success.

Ministerial Strategic Group indicators

Alongside integration authority annual performance reports, the Ministerial Strategic Group for Health and Community Care regularly review data on the group's six target indicators:

Number of emergency admissions.

Number of unscheduled hospital bed days.

Number of A&E attendances.

Number of delayed discharge bed days.

Percentage of last six months of life spent in the community.

Percentage of population residing in non-hospital setting for all people aged 65+.

These six objective measures enable comparison of integration authorities, but have their limitations. By focussing on hospital-based health measures, there is a lack of focus on patient experience or provision of social and community care. One of the key aims of integration is to shift care from hospital to community sector. The lack of emphasis on social and community care in the six indicators may move focus away from this aim and the joined up thinking required between health and social care services to change the way services are provided.

Additionally, recent research highlighted that over-reliance on health, and particularly hospital, indicators of health and social care integration could inhibit involvement of third sector parties (including patient view groups and charities) and downplay the importance of social care1. This may encourage efforts to reduce use of hospitals without truly encouraging improvement in, and increased provision of, social and community care services. Without effort to include third sector organisations, and patients, there is a risk that services will not be focussed on patient-centred outcomes. Relating to this, Audit Scotland noted that meaningful and sustained engagement with the public and patients is key for integration. In responding to the Audit Scotland report, the Ministerial Strategic Group set out three proposals to improve efforts to engage the public and third sector groups with integration over the next 6-12 months2.

As indicated above, it is also important that integration authorities are able to set local improvement objectives within the context of their area, considering their available resources and demographics. The Ministerial Strategic Group focus on six, fairly narrow, hospital indicators may not align to local needs and create challenges in where to focus efforts, in terms of local need versus Government focus.

Reported performance

This section reports data on the six Ministerial Strategic Group indicators. A description of data sources and caveats are in Annex A. Currently, data are not routinely publicly reported for all six indicators.

1. Number of emergency admissions

Emergency admissions occur when people are admitted to hospital as soon as possible after seeing a doctor. This may or may not be via Accident and Emergency. The total number of emergency admissions is the number of continuous spells in hospital relating to an emergency admission within a financial year. This means that one patient may have multiple emergency admissions within a year, although if a patient is admitted to hospital as an emergency and then transferred to different wards this counts as a single overall admission. These data are based on date of discharge1.

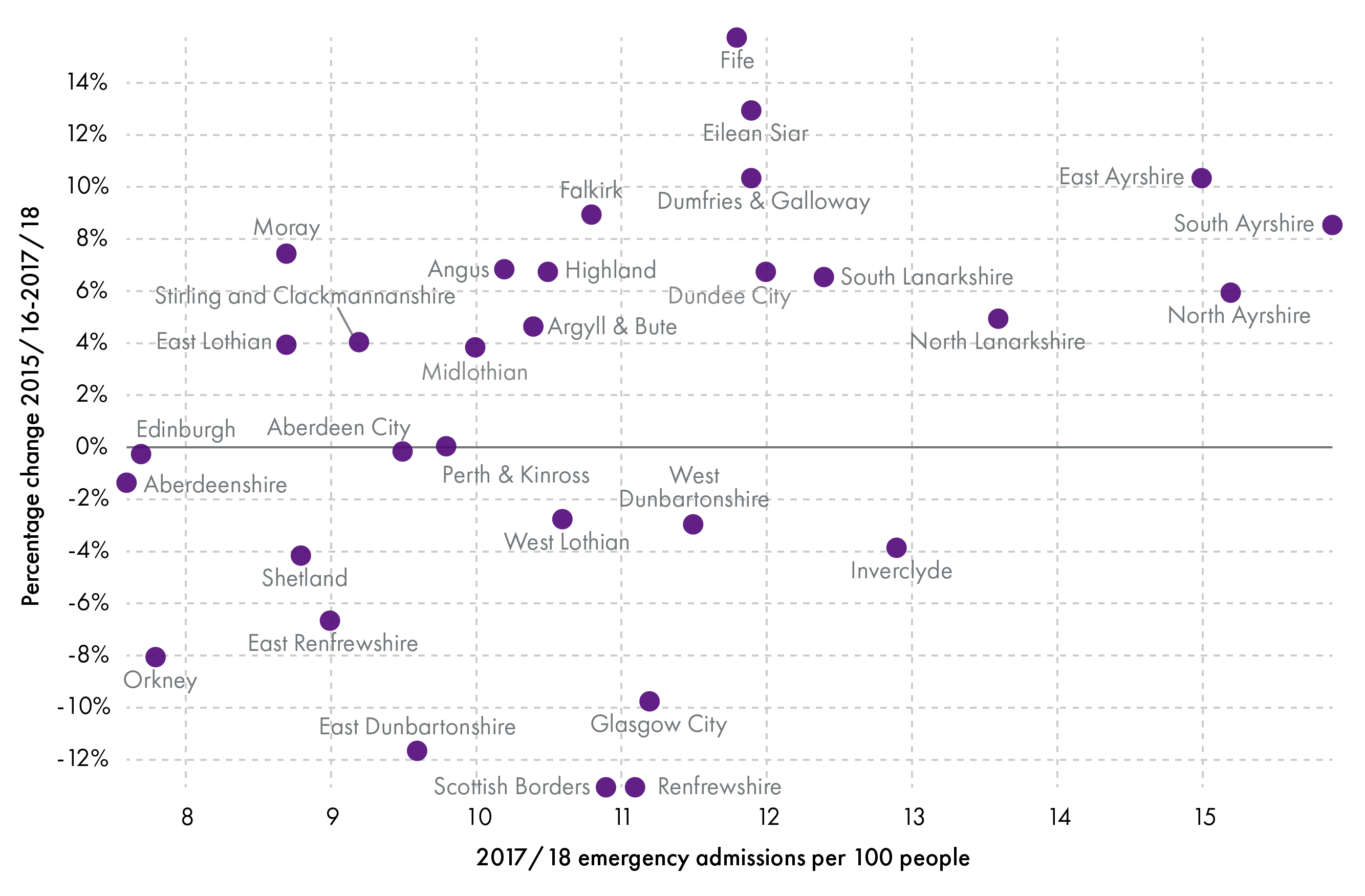

The number of emergency admissions in Scotland increased from 581,195 in 2015/16 to 588,520 in 2017/18. This is over a 1% increase and does not suggest that integration is having a positive impact on emergency admissions.

The picture across Scotland is more complex (Figure 10), with some integration authorities decreasing total emergency admissions across this time (by up to 13%) and 17 integration authorities showing increases (by up to 16%). The rate of emergency admissions also varied widely across integration authorities.

2. Number of unscheduled hospital bed days

Unscheduled bed days relate to all days spent in hospital within a continuous hospital stay following an emergency or urgent admission. Occupied bed days are calculated by counting the number of days between the date of admission associated with the beginning of a patient's continuous spell of treatment and the date of discharge associated with the end of the same spell of treatment 1.

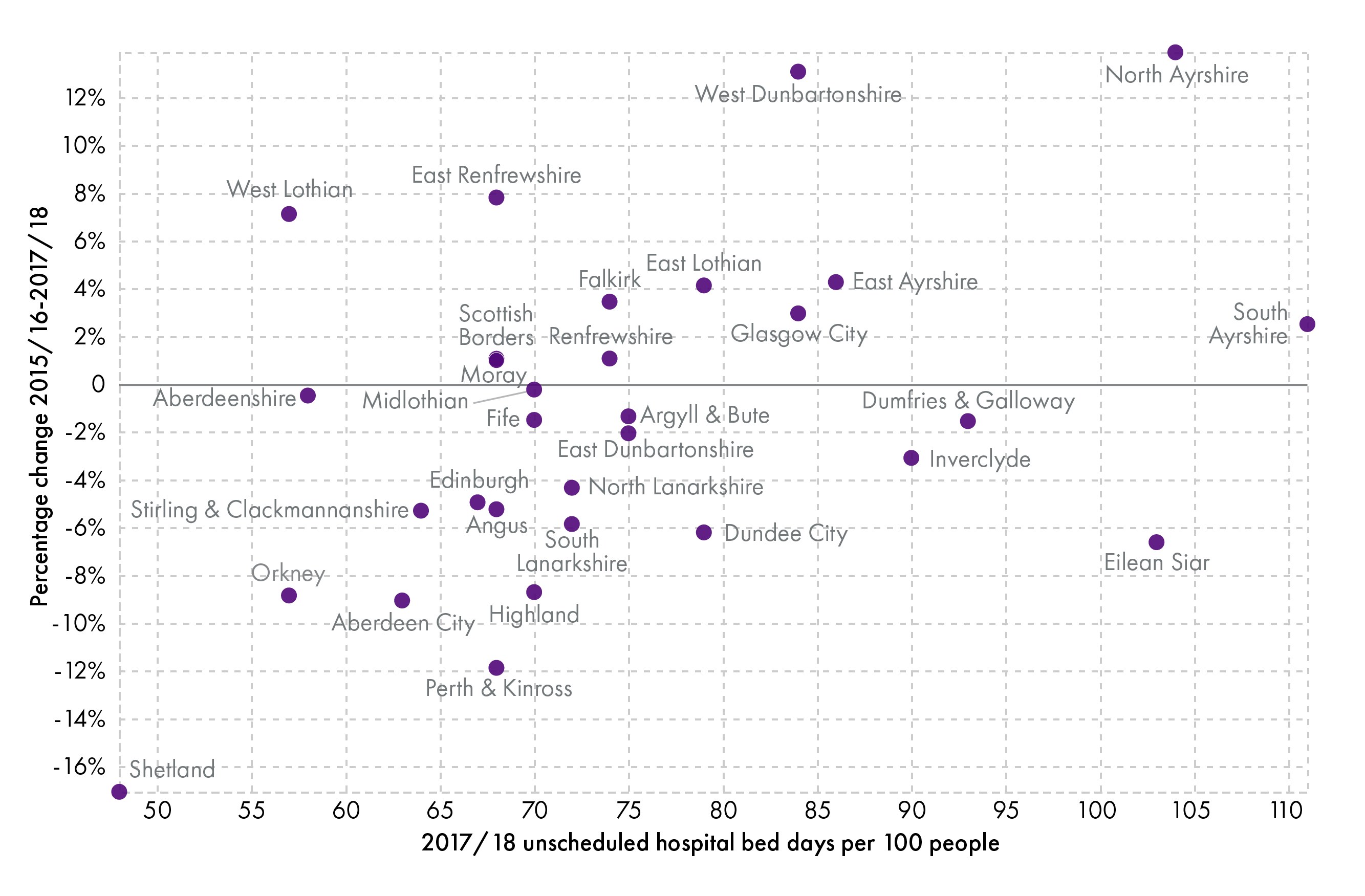

Across Scotland, there was over a 1% reduction in unscheduled hospital bed days across 2015/16 to 2017/18, from 4,061,338 to 4,009,233 bed days. This is a small, but positive, sign for integration. As the number of emergency admissions have increased, the reduction in bed days reflects shorter lengths of stay, on average, after admission. A total of 19 of the 31 integration authorities reduced their unscheduled hospital bed days over this time (by up to 17%). The remaining 12 integration authorities had an increased proportion of unscheduled bed days between 2015/16 to 2017/18 (of between 1-14%), although 5 of these did show decreases between 2016/17 and 2017/18 (Figure 11).

South Ayrshire had the largest number of unscheduled bed days per 100 people in 2017/18, of 111. This was almost a 3% increase from 2015/16, although their levels had dropped since 2016/17. On the other end of the scale, Shetland had only 48 unscheduled bed days per 100 people in 2017/18, a 17% decrease from 2015/16 figures. Whilst some of the difference in numbers may reflect differences in geographical, and other contextual factors, the variability in progress to reduce unscheduled hospital bed days suggests that some integration authorities are having more success than others (Figure 11).

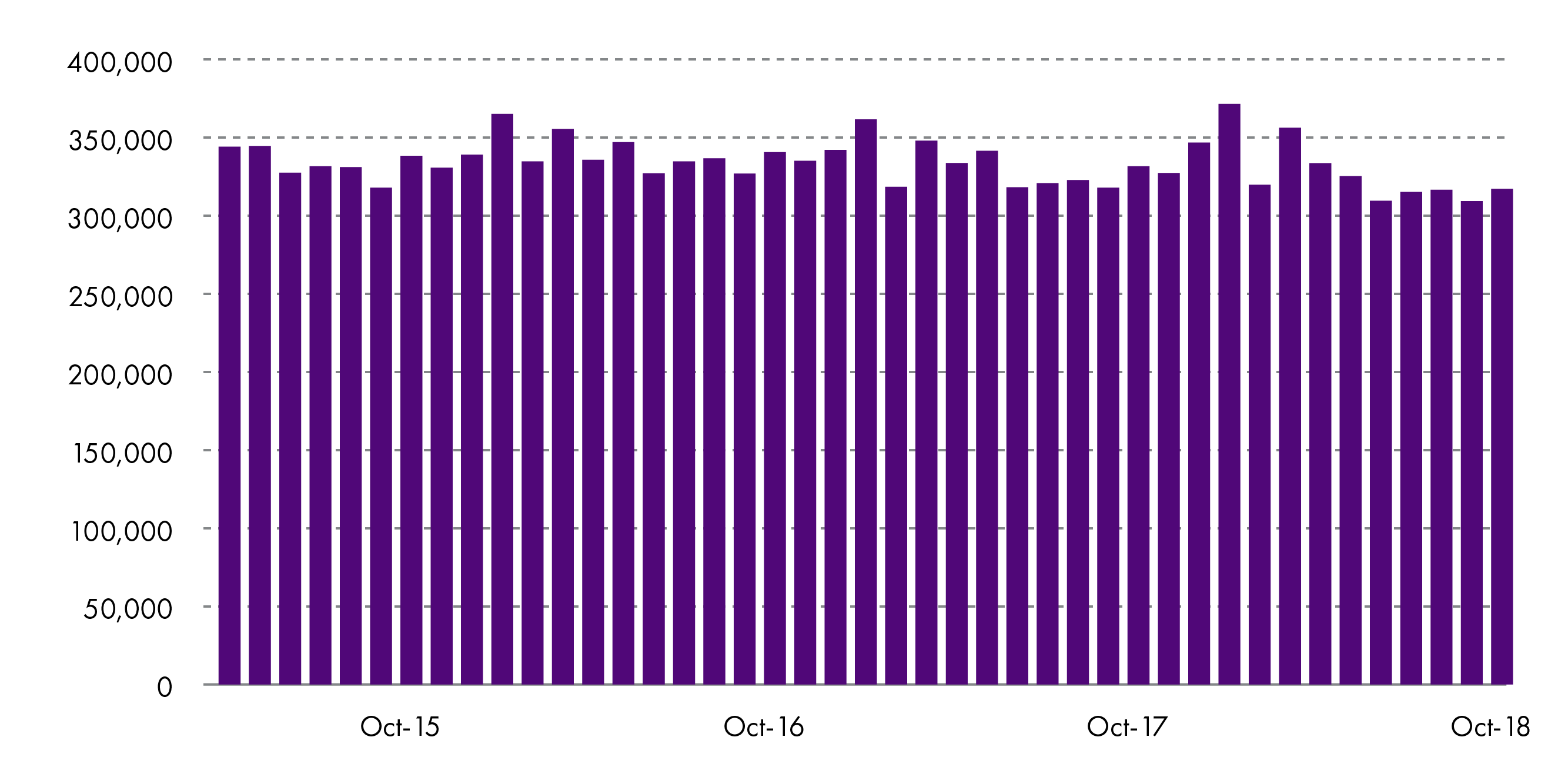

The total monthly unscheduled hospital bed days across Scotland are shown in Figure 12. This indicates a slight decreasing trend in unscheduled hospital bed days up to October 2018. The spikes mostly correlate to winter periods, when emergency admissions tend to be higher due to influenza and other conditions that have a higher incidence in winter time.

3. Number of accident and emergency admissions

The number of A&E admissions in Scotland increased by 6% from 2015/16 to 2018/19, from 1,447,636 to 1,540,654. The pace of increase has grown slightly over this time, with admissions increasing by 2% between 2015/16 and 2016/17, as well as 2016/17 and 2017/18, then by 3% between 2017/18 and 2018/19.

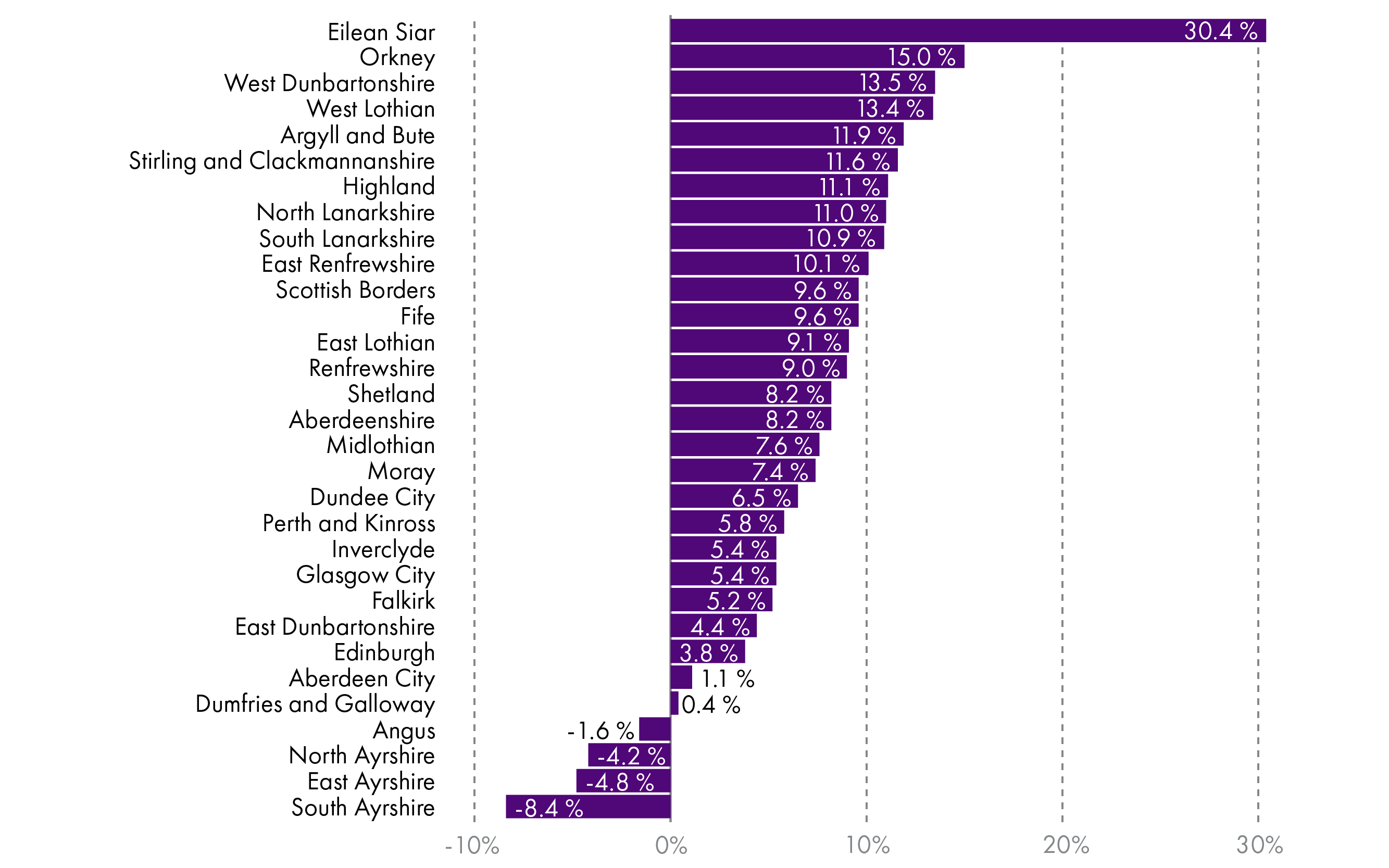

In the individual integration authorities, there are few examples where A&E admissions have decreased. Comparing 2018/19 to 2015/16, only Angus, East Ayrshire, North Ayrshire, and South Ayrshire showed decreases in their A&E admissions. A few integration authorities showed early decreases in A&E admissions from 2015/16 to 2016/17 or 2017/18, but by 2018/19 had higher rates of A&E admissions (including Aberdeen City, Falkirk, and Stirling and Clackmannanshire). Other integration authorities showed an increase in emergency admissions yearly from 2015/16 to 2018/19. The starkest numbers were in Eilean Siar, where there was a 30% increase in emergency admissions between 2015/16 to 2018/19. This may partly reflect the small size of this integration authority as the 30% increase reflected 1,877 extra admissions. In North Lanarkshire, by comparison, there was an increase of 12,500 admissions between 2015/16 to 2018/19, which reflected an 11% increase from their baseline in 2015/16 (Figure 13).

4. Number of delayed discharge bed days

Delayed discharge bed days reflect how long people are kept in hospital once they are ready to leave (for example, because a social care package has not been agreed). Reducing delayed discharge bed days is a key aim for integration authorities. Length of delay is calculated from the date that the patient was deemed “ready for discharge” until their discharge date or the end of the calendar month for patients still in delay.

In Scotland, the number of delayed discharge bed days for adults has been increasing across time, from 493,614 in 2017/18 to 521,215 in 2018/19. Across Scotland, there was wide variability in changes between these years. Eleven integration authorities successfully reduced the number of delayed discharge bed days, by up to 68%. On the other hand, 20 integration authorities had an increase of between 2-52%. This variability highlights the need to share good practice and identify why some areas seem to be having great difficulty in reducing delayed discharges, whilst others are achieving more success. Orkney had the greatest reported decrease (of 68%), reflecting a change from 1,411 delayed discharge bed days in 2017/18, versus 452 in 2018/19 (Figure 14).

Geographical, demographic, and other contextual factors are important to consider for this indicator and others, as integration authority performance will be closely related to the number of elderly people in the area and the availability of care home or similar community placements1.

5. Percentage of last six months of life spent in the community

In 2017/18, 88% of people’s last six months were spent in the community rather than in hospital. This is almost 2% higher than in 2014/15. All but two integration authorities (Dumfries and Galloway, and North Ayrshire) had increases in the percentage of last six months of life spent in the community across this time, though these were fairly small (at most a 3% absolute change). Overall, integration authorities performed well against this indicator, with the percentage ranging from 85-95% in 2017/18. The top performers were Orkney (91%) and Shetland (95%).

These figures exclude accidental deaths and are calculated by subtracting days spent in hospital from the total number of days in last six months of life. Community includes care home residents as well as those living in their own home. Figures for 2017/18 are provisional.

6. Percentage of population residing in non-hospital setting for all people aged 65+

The percentage of people aged 65 years or over residing in hospital decreased by 0.1% from 2014/15 to 2017/18. Over this time, there was an increase of 0.7% in the proportion of people aged 65 or over living at home unsupported (not receiving home care), a 0.4% decrease in people living at home supported (receiving home care), and a 0.2% decrease in people living in care homes. Some of the changes may reflect changes in eligibility for support.

Small changes in where people aged 65 or over were living were seen in the integration authorities across time. In 2017/18, between 88-94% of people in each integration authority were living at home unsupported. People living in a supported home setting accounted for approximately 5%, ranging from 3% in the Highlands to 8% in West Dunbartonshire. The population living in care homes or hospitals was small, accounting for 3% and 1%, respectively, of those aged 65 years or over in 2017/18.

This indicator is still being developed and is based on estimates, for example the proportion of care home residents cannot be calculated directly so is estimated from the annual care home census for the number of long-stay care home residents. The hospital data are based on the average population in hospital during the year. Figures for 2017/18 are provisional.

Summary of progress

Nationally, there is a mixed picture of success of integration for the six Ministerial Strategic Group indicators (Table 1). There have been positive signs, including a decrease in the number of unscheduled hospital bed days and increases in the percentage of people's last six months spent in the community as well as percentage of population residing in non-hospital settings for people aged 65 years or over. On the other hand, emergency admissions, A&E attendances, and delayed discharge bed days have all increased.

At local level, the data highlight considerable variability in performance, suggesting scope for improvement. This requires careful consideration of the budgetary and performance issues outlined in this briefing, including the need to share good practice across integration authorities.

| Scotland totals | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | Positive or negative change? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of emergency admissions | n/a | 581,195 | 583,277 | 588,250 | n/a | Negative |

| Number of unscheduled hospital bed days | n/a | 4,061,338 | 4,055,254 | 4,009,233 | n/a | Positive |

| Number of A&E attendances | n/a | 1,447,636 | 1,468,893 | 1,496,553 | 1,540,654 | Negative |

| Number of delayed discharge bed days | n/a | n/a | n/a | 493,614 | 521,215 | Negative |

| Percentage of last six months of life spent in the community | 86.2 | 86.7 | 87.0 | 87.9 | n/a | Positive |

| Percentage of population residing in non-hospital settings for all people aged 65+ | 98.8 | 98.8 | 98.9 | 98.9 | n/a | Positive |

Ongoing activity and next steps

This briefing provides an update on the spending and performance of health and social care integration in Scotland since The Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014. This highlights that there are areas of strength and weakness, both within and across Scotland. A consistent problem in respect of scrutiny of health and social care integration lies in finding publicly available data, reported in a comparable way across integration authorities, on performance and finance. There has also been little independent research into integration by academics.

Efforts to address identified problems are ongoing by the integration authorities and partners themselves, as well as the Scottish Government, and other relevant organisations. Planned evaluation of progress includes ongoing work by the Health and Sport Committee in the Scottish Parliament to scrutinise budgets and performance, by Audit Scotland to complete national performance audits, as well as by the Ministerial Strategic Group for Health and Community Care on their 25 proposals for action1.

At the end of May 2019, the Ministerial Strategic Group reviewed progress on their proposals for action2. In relation to finance, the Ministerial Strategic Group is currently contacting integration authorities regarding improvement in clarity and implementation of budget setting processes, particularly for the set aside budget. They expect progress to be aided by several ongoing initiatives to improve leadership and relationships in integration authorities, as well as from results of a self-evaluation exercise developed by the group. The self-evaluation exercise should have been completed by integration authorities by 15th May 2019, with an aim to repeat this closer to February 2020 for comparison. Data from the first exercise are currently being analysed, but it is unclear whether findings will be made publicly available 2.

In relation to performance, improvement in relationships and collaborative working, which would include sharing of good practice, was referred to in the Ministerial Strategic Group report as an area for integration authorities, and their partners, to address with little further information. A workshop for integration authorities took place in April 2018 to discuss annual performance reports and opportunities for benchmarking and sharing good practice. The Ministerial Strategic Group have indicated that this will be repeated in 2019 and that they are aiming to use outcomes to develop a framework for community-based health and social care integrated services2.

Lack of engagement with third and independent sectors, which is key to identify appropriate patient-centred outcomes, is being addressed firstly through the self-evaluation exercise to identify areas for improvement. The Ministerial Strategic Group also expect the self-evaluation exercise to identify issues with strategic planning, accountability, and responsibility. Alongside this, a working group has been established to develop guidance on community engagement and participation2.

Data sharing and availability was highlighted as a key area for improvement in this briefing as well as by the Ministerial Strategic Group1 and others7. In line with this, the Ministerial Strategic Group are reviewing their target indicators for performance. As part of this, ISD Scotland are working to provide more data on patient "journeys" through health and social care via the SOURCE dataset. More information is available in their recent publication “Insights into Social Care in Scotland”. ISD's aim is for SOURCE to provide a wider view of health and social care use than is currently available from the six Ministerial Strategic Group indicators. Currently, integration authorities cannot compare SOURCE data across all integration authorities in Scotland, which limits benchmarking opportunities. SOURCE data are also not yet publicly available, which hinders public efforts to scrutinise performance of integration authorities.

Specific data gaps and plans to address these were identified in a report by ISD as follows8:

Community care: ISD aim to increase coverage of district nursing data and extend data collection for other community activities (such as mental health).

Primary Care: initiatives are underway to make primary care data publicly available and linked to other data, through initiatives such as the SPIRE dataset.

Intermediate care: ISD have designed a prototype dataset for intermediate care data (reflecting services that allow people to avoid hospital admission, reduce long hospital stays, recover from illness faster, and plan for future care), but this is not yet widely available.

Third sector: third sector service data are currently not linked to SOURCE. There are a number of challenges in addressing this, including variation in organisation capacity and progress has been slow.

Care: independent sector care funded by Local Authorities is included in SOURCE, but privately funded care is not. The Scottish Government is in discussion with Scottish Care and ISD to address this.

Scottish Ambulance Service data are currently not linked to the SOURCE file, but there are plans for this to become available soon.

This briefing confirms the need to make data more available for scrutiny in a timeous manner, as well as making data on performance more widely available across the spectrum of health and social care. This includes financial data, with a need to ensure that integration authorities report financial data in a consistent manner for public scrutiny.

Finally, aside from the Ministerial Strategic Group and integration authority efforts to progress integration, organisations such as IFIC Scotland and the Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland are driving efforts to improve integration.

IFIC Scotland aims to increase the research and evaluation of local integration efforts, then address how successful initiatives can be scaled up and adapted to other, national and international, settings. This is tied with efforts to encourage academic research into integration, which should promote objective evaluation of integration initiatives to identify which are successful and why.

Finally, the Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland are focussed on improving third sector and public engagement with integration, a key issue identified in the Ministerial Strategic Group report1.

Overall, this briefing highlights that considerable work is underway to improve reporting on performance and finance, which should support more effective scrutiny of integration authorities in future.

Case study: South Lanarkshire

Numerous examples of integration authority work are described in the 2018 Audit Scotland report "Health and social care integration: Update on progress"1 as well as the King's Fund report "Leading across health and social care in Scotland: Learning from chief officers’ experiences, planning next steps"2. This section follows up the South Lanarkshire case study used in the Audit Scotland report1. It gives an example of the type of change that integration should facilitate.

This case study reported on the closure of a care of the elderly ward at Udston hospital, after it was identified that a number of patients could receive appropriate care in the community. Prior to the ward closure, analysis was undertaken to identify the costs associated with the ward and how the respective finances could be shifted to support additional community based care and other cost pressures from closing the hospital beds. This estimated that over £1 million would be available to be used in alternative ways. Of this, it was agreed that £0.70 million should be redirected to improve or provide community-based services. The remaining £0.37 million was left with the hospital sector, to meet cost pressures on the set aside budget (such as inflation) and for reinvestment in acute hospital services, as demand was expected to change as a result of the ward closure4. The plans for the £0.70 million for community reinvestment (alongside £0.06 million from elsewhere in their budget) are4:

| Service | Spend (£000s) |

|---|---|

| Homecare | 376 |

| Community nursing | 243 |

| Support Workers | 60 |

| Physiotherapy | 40 |

| Pharmacy | 42 |

The aim was to address the need for services that respond to crises, prevent hospital readmission, and reduce the need for hospital stays.

Particular issues identified during the process were:

Consultation and engagement - the integration joint board undertook public engagement to develop their Strategic Commissioning Plan and existing governance arrangements as they related to engagement with NHS staff. This highlighted the potential to create a blueprint or further guidance for similar initiatives in the future. This is in line with the Minister Strategic Group proposals to improve community and third sector engagement in integration authority work7.

Ownership of the money and savings, as well as how these were spent – it was not simple to determine where identified savings belonged in relation to the integration authority, health board, or local council.

Annex A: Data sources

Financial analyses in this briefing use data from:

Scottish Health Service Costs1

Scottish local government finance statistics2

end of year audited accounts for 2016/17 and 2017/183

unaudited accounts from the 1st and 3rd quarter of 2018/194 5

reported 2017/18 set aside amounts6

unaudited end of year 2018/19 accounts (as of June 5th 2019) and 2019/20 opening budgets7

spending by sector (from the Scottish Government, personal communication).

As the 2018/19 spending is unaudited, these data are subject to change, as are the 2019/20 budget figures, which are subject to in-year changes. For this reason, 2019/20 opening budget figures are compared with budget figures from quarter 1 in 2018/19.

Performance analyses in the briefing uses data from the Scottish Government on the six indicators monitored by the Ministerial Strategic Group (data from Scottish Government, personal communication). These are not routinely published for public scrutiny.

The reported performance data includes all non-obstetric and non-psychiatric hospitals in Scotland, covers people of any age except for delayed discharge bed days (where only patients aged 18 years or over are included). Non-Scottish residents and geriatric long stay patients are excluded.

The A&E data only include ‘new’ and ‘unplanned return’ attendances, not those who were ‘recalled’ or marked as ‘planned returns’. Only sites submitting data at episode level (detailed records for each attendance rather than a monthly aggregated summary) are included. This includes emergency departments, minor injury units, and other sites that provide emergency department related activity.

Performance data from hospitals are not complete (i.e. there are missing data on admission or other numbers). More information can be found at: http://www.isdscotland.org/products-and-Services/Data-Support-and-Monitoring/SMR-Completeness/.