Referendums (Scotland) Bill

The Referendums (Scotland) Bill provides the legislative framework for holding referendums which fall within the competence of the Scottish Parliament.

Introduction

The Scottish Government introduced the Referendums (Scotland) Bill in the Scottish Parliament on 28 May 2019.

At present, there is no legislation which provides specifically for referendums held under Acts of the Scottish Parliament. There is existing UK legislation which covers elections and referendums, principally the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. Part 7 of that Act provides a framework for referendums held under Acts of the UK Parliament.

The Referendums (Scotland) Bill provides for Ministers, by regulations (subordinate legislation), to hold a referendum with the date, wording of the question(s), form of ballot paper, and the referendum period to be set out in regulations.

The Bill also sets out a legislative framework for the holding of referendums in Scotland, by providing for:

the franchise and arrangements for voting;

the conduct of the poll and counts;

campaign rules.

This briefing describes the key provisions of the Bill and, where possible, compares these with existing legislation. An overview of current thinking on best practice for referendums is also given.

This briefing is not intended to provide an exhaustive description of every proposal contained in the Bill. This can be found in the explanatory notes that accompany the Bill. The Scottish Government sets out its thinking behind the proposals, along with information on any alternatives considered when drafting the Bill, in the policy memorandum.

The Finance and Constitution Committee has been designated as lead committee for the Bill.

Can the Parliament legislate for referendums?

Under Schedule 5 of the Scotland Act 1998, referendums are not a reserved matter.

The Referendums (Scotland) Bill provides for referendums generally; it does not legislate for a referendum on a specific matter.

The Presiding Officer and the Scottish Government agree that the Bill is within the Parliament's competence1.

A referendum on independence?

Whilst the Bill does not relate to a specific issue, the context in which it has been introduced includes that the Scottish Government has indicated its intention "to offer the people of Scotland a choice on independence later in the term of this Parliament1".

Schedule 5 of the Scotland Act 1998 reserves the Union of the Kingdoms of Scotland and England. This has been widely interpreted to mean that the Scottish Parliament does not have competence to hold a referendum on independence2.

Schedule 5 can be amended or modified to give the Scottish Parliament the power to hold an independence referendum. To do this, an order under Section 30 of the Scotland Act is required. Section 30(2) of the Scotland Act 1998 provides that:

“Her Majesty may by Order in Council make any modifications of Schedule 4 or 5 which She considers necessary or expedient.”

legislation.gov.uk. (1998, November 19). The Scotland Act 1998, Section 30 (2). Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/46/section/30

A Section 30 Order temporarily empowered the Scottish Parliament to hold the 2014 independence referendum.

The First Minister has indicated that the Scottish Government would seek to secure a Section 30 Order for a future referendum on Scottish independence "to put beyond doubt or challenge our ability to apply the bill to an independence referendum.4"

Background to UK legislation on referendums

The first UK -wide referendum was held in 1975 and concerned the UK's membership of the European Community. A "border poll" had been held in Northern Ireland in 1973.

In 1996 a Commission on the Conduct of Referendums, established jointly by the Constitution Unit at University College London and the Electoral Reform Society and chaired by Sir Patrick Nairne, proposed the enactment of a ‘generic Referendums Act as a statutory basis for the conduct of a series of referendums1'. The Commission's first guideline set out its view of the parameters of such a legislative framework.

Guidance should be drawn up dealing with organisational, administrative and procedural matters associated with holding a referendum. Established guidelines should include fixed rules for some matters (for example, the organisation of the poll, the election machinery and the count). For other matters, on which it is impossible to determine rules in advance (for example, wording the question), the guidance should state how a decision should be reached.

Commission on the Conduct of Referendums. (1996, November 21). Report of the Commission on the Conduct of Referendums , page 26. Retrieved from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/political-science/publications/unit-publications/7.pdf [accessed 04 June 2019]

In October 1998, the Committee on Standards in Public Life , Chaired by Lord Neill of Bladen QC, published its Fifth Report of the Committee on Standards in Public Life (the 'Neill report'). The report considered the funding of political parties in the UK. The report's recommendations were numerous and dealt with issues from the reporting of donations to the Honours system.

Chapter 12 of the Neill report considered referendums specifically. The key areas in relation to referendums which Neill considered were 'the need to provide both sides of an argument with a proper voice during the course of a referendum [and] greater transparency on expenditure on political advertising and a watching brief for the Election Commission in relation to party broadcasts'3.

The UK Government’s response to the report was set out in a White Paper (Cm 4413) published on 27 July 1999. The White Paper included draft legislation to create standing statutory arrangements for the conduct of referendums: the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (PPERA).

More detail on the PPERA can be found in this briefing under the section 'How does the Bill compare to existing legislation?'

A summary of UK referendums to date is provided below.

| Referendum | Question | Answer Format | Result | Legislative basis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Border Poll" Northern Ireland, March 1973 | Do you want Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom?orDo you want Northern Ireland to be joined with the Republic of Ireland outside the United Kingdom | Tick box | Northern Ireland remained part of the UK | Northern Ireland (Border Poll) Act 1972 |

| Membership of the European Community, June 1975 | Do you think that the United Kingdom should stay in the European Community (the Common Market)? | Tick YES box or NO box | The UK remained in the European Community | Referendum Act 1975 |

| Devolution to Scotland, March 1979 | Do you want the provisions of the Scotland Act 1978 to be put into effect? | Tick YES box or NO box | Devolution did not proceed as the requirement that 40 per cent of the electorate had to vote "yes" was not met | Scotland Act 1978 |

| Devolution to Wales, March 1979 | Do you want the provisions of the Wales Act 1978 to be put into effect? | Tick YES box or NO box | Devolution did not proceed | Wales Act 1978 |

| Devolution to Scotland, September 1997 | I agree that there should be a Scottish ParliamentorI do not agree that there should be a Scottish Parliament | Tick box | The Scottish Parliament was established | Referendums (Scotland and Wales) Act 1997 |

| I agree that a Scottish Parliament should have tax-varying powersorI do not agree that a Scottish Parliament should have tax-varying powers | Tick box | The Scottish Parliament was given tax-varying powers | ||

| Devolution Wales, September 1997 | I agree that there should be a Welsh AssemblyorI do not agree that there should be a welsh assembly | Tick box | The Welsh Assembly was established | Referendums (Scotland and Wales) Act 1997 |

| Greater London Authority, May 1998 | Are you in favour of the Government's proposals for a Greater London Authority, made up of an elected mayor and a separately elected assembly? | Tick YES box or NO box | The Greater London Authority was established | Greater London Authority (Referendum) Act 1998 |

| Belfast Agreement Northern Ireland, May 1998 | Do you support the Agreement reached at the Multi-Party Talks in Northern Ireland and set out in Command Paper 3883? | Tick YES box or NO box | Community consent for continuation of the Northern Ireland peach process on the basis of the Belfast Agreement was given | Northern Ireland (Entry to Negotiations etc) Act 1996 |

| Elected Regional Assembly North East of England, November 2004 | Should there be an elected assembly for the North East region? | Tick YES box or NO box | The Elected Regional Assembly for the North East was not established. | Regional Assemblies (Preparations) Act 2003 |

| Legislative powers of the Welsh Assembly, March 2011 | Do you want the Assembly now to be able to make laws on matters in the 20 subject areas it has powers for? | Tick YES box or NO box | The Assembly now has these powers | Government of Wales Act 2006 |

| Electoral Reform, May 2012 | At present, the UK uses the "first past the post" system to elect MPs to the House of Commons. Should the "alternative vote" system be used instead? | Tick YES box or NO box | The voting system was not changed | Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act 2011 |

| Scottish Independence, September 2014 | Should Scotland be an independent country? | Tick YES box or NO box | Scotland remained part of the UK | Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 and Scottish Independence Referendum (Franchise) Act 2013 Acts of the Scottish Parliament |

| United Kingdom European Union Membership, June 2016 | Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union? | Remain a member of the European Union tick box Leave the European Union tick box | UK to leave European Union | European Union Referendum Act 2015 |

Background to the introduction of the Bill

The Referendums (Scotland) Bill provides for referendums generally; it does not legislate for a referendum on a specific matter.

The most recent referendum held only in Scotland, the referendum on Scottish independence, which took place on 18 September 2014, was provided for by the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 and the Scottish Independence Referendum (Franchise) Scotland Act 2013. These Acts covered all aspects of the campaign, franchise, poll and count. The Scottish Parliament was able to legislate for the referendum after a Section 30 Order was granted in January 2013. The Section 30 Order meant that the Parliament had temporary competence to legislate for the referendum, which dealt with the Union, a reserved matter.

The Edinburgh Agreement, concluded by the UK and Scottish Governments on 15 October 2012, committed the Scottish Government to take account of the rules set out in the Political Parties Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (PPERA) when conducting the referendum.

The Scottish Independence Referendum (Franchise) Bill was introduced on 11 March 2013. The Bill set the franchise for the referendum in line with the franchise for Scottish Parliament and Scottish local government elections, but also extended the franchise to allow 16 and 17 year-olds to vote.

The Scottish Independence Referendum Bill was introduced on 21 March 2013. The Bill set out the date of the referendum; the question; the ballot paper to be used; the conduct of the referendum and the rules on campaigning for the referendum.

The poll was held on 18 September 2014; Scotland remained a part of the United Kingdom.

The SNP manifesto for the 2016 Scottish Parliament elections, held on 5 May 2016, stated that:

We believe that the Scottish Parliament should have the right to hold another referendum if there is...a significant and material change in the circumstances that prevailed in 2014, such as Scotland being taken out of the EU against our will.

The Scottish National Party. (2016, April 20). Manifesto for the 2016 Scottish Parliament elections. Retrieved from https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/thesnp/pages/5540/attachments/original/1461753756/SNP_Manifesto2016-accesible.pdf?1461753756 [accessed 04 June 2019]

On 23 June 2016, the UK voted to leave the European Union (EU) with a majority of 51.9%. In Scotland, 62% of those who voted opted to remain in the EU, with 38% voting to leave.

The Scottish Government published a draft independence referendum Bill in October 2016. The Bill was subject to a public consultation which closed in January 2017.

On 28 March 2017, the Scottish Parliament passed a motion on division (for 69; against 59) mandating the Scottish Government:

to take forward discussions with the UK Government on the details of an order under Section 30 of the Scotland Act 1998 to ensure that the Scottish Parliament can legislate for a referendum to be held that will give the people of Scotland a choice over the future direction and governance of their country at a time, and with a question and franchise, determined by the Scottish Parliament, which would must appropriately be between the autumn of 2018, when there is clarity over the outcome of Brexit negotiations, and around the point at which the UK leaves the EU in spring 2019

The Scottish Parliament. (2017, March 28). The Official Report. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10869 [accessed 04 June 2019]

On 31 March 2017, the First Minister wrote to the Prime Minister, Theresa May, to request a Section 30 order under the Scotland Act 1998. The request was refused by the Prime Minister on the basis that "now is not the time" for a second referendum on Scottish Independence.

After several months of uncertainty over the UK's exit from the EU, on 24 April 2019, the First Minister made a statement to Parliament on 'Brexit and Scotland's Future'. There were three key announcements in the statement:

an invitation for parties represented at Holyrood to attend cross party talks to find areas of agreement on constitutional and procedural change;

a citizens' assembly to consider the issues around the future of Scotland, and

legislation "to set the rules for any referendum that is, now or in the future, within the competence of the Scottish Parliament".

The First Minister also set out the Scottish Government's thinking on the timing of a second independence referendum, she said:

That is why I consider that a choice between Brexit and a future for Scotland as an independent European nation should be offered later in the lifetime of this Parliament. If Scotland is taken out of the EU, the option of a referendum on independence within that timescale must be open to us.

The Scottish Parliament. (2019, April 24). The Official Report. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12053&i=109040 [accessed 04 June 2019]

The Referendums (Scotland) Bill follows the First Minister's commitment to introduce legislation to set the framework for any referendums held in Scotland which are within the competence of the Scottish Parliament.

On 24 April the First Minister gave a statement to the Scottish Parliament, setting out next steps on Brexit and Scotland's Future. She said that the Scottish Government would take steps so the option of giving people a choice on independence later in the current term of Parliament remained available. The Referendums (Scotland) Bill would help to facilitate that by ensuring that the rules for any referendum that is now, or in future, within the competence of the Scottish Parliament are clear.

The Scottish Parliament. (2019, April 24). The Official Report, Brexit and Scotland's Future. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12053&i=109040 [accessed 05 June 2019]

The Cabinet Secretary for Government Business and Constitutional Relations, Michael Russell MSP, made a statement Next Steps on Scotland's Future on 29 May 2019.

The Bill provides a legal framework for holding referendums on matters which are now or in future within the competence of the Scottish Parliament.

The rules it sets out are of the highest standards and will ensure that the results are widely and internationally accepted. It brings Scotland into line with the UK where there is already standing legislation for referenda through the Political Parties Elections and Referendums Act which Westminster passed in 2000.

As the First Minister indicated in her statement, we intend at a future date to negotiate with the UK Government for a section 30 order to put beyond doubt our competence to hold a referendum on independence.

Next steps on Scotland's Future: Ministerial statement, 29 May 2019

The Referendums (Scotland) Bill

The Bill's stated policy objective is "to put in place a generic framework for referendums that provides technical arrangements which can be applied for specific referendums"1.

The Scottish Government's position is that having a legal framework in place will "enable legislation for any future referendum to be taken forward in a timely manner and allow parliamentary scrutiny to focus on the merits of that particular proposal, the questions to be asked and the timing of the referendum.2" The Electoral Commission has recommended that 'referendum legislation should be clear at least six months before it is required to be implemented or complied with'3.

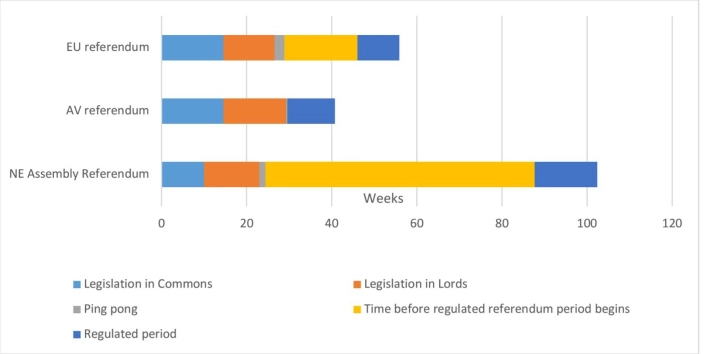

UK referendums held under the PPERA have all had relatively long time-frames. The AV referendum in 2011 had the shortest with 9 months from the introduction of the legislation to polling day. The Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 was introduced on 21 March 2013; was passed by the Parliament on 14 November 2013 and received Royal Assent on 17 December 2013. The referendum was held on 18 September 2014.

The PPERA provides a framework for referendums held under Acts of the UK Parliament. There is no equivalent legislation to set out the framework of referendums held under Acts of the Scottish Parliament.

Ad hoc primary legislation made by the Scottish Parliament can deal with referendums within its competence. Each Act would need to set the rules for the referendum for which it is providing.

The Scottish Government is of the view that the continuation of an ad hoc approach would "be a less effective option as it requires Parliament to consider similar procedural provisions for each separate referendum, and is out of step with recent developments in electoral administration and good practice elsewhere in the UK5".

The framework proposals in the Bill build on the arrangements which were put in place for the 2014 referendum. The Electoral Commission has assessed that:

the experience of legislating for the Scottish Independence Referendum provides, in the main, a model for the future development of referendum and electoral legislation. Sufficient time was allowed by the Scottish Government to consult on the proposed legislation, followed by the Scottish Parliament having sufficient time to properly scrutinise proposals and legislate, with Royal Assent for the primary pieces of legislation being in place nine months before 18 September.

The Electoral Commission. (2007). Scottish elections 2007 The independent review of the Scottish Parliamentary and local government elections 3 May 2007. Retrieved from http://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/__data/assets/electoral_commission_pdf_file/0011/13223/Scottish-Election-Report-A-Final-For-Web.pdf [accessed 10 May 2017]

The Bill is made up of 42 Sections with much of the detail being provided for in its 7 Schedules.

Section 1: Power to provide for referendums

Section 1 gives Ministers a power to provide for referendums to be held throughout Scotland on one or more questions by regulations (secondary legislation) subject to the affirmative procedure.

Under Section 1, Ministers must consult the Electoral Commission before laying draft regulations before the Scottish Parliament. Such regulations must include the date on which the referendum is to be held, the referendum period and the form of the ballot paper including the wording of the question(s) to be asked and the possible answer(s).

The power to make regulations to hold a referendum negates the need for referendum specific primary legislation (like the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013). As such, the Bill could facilitate an expedited referendum process by reducing the time required for parliamentary scrutiny. This is because, when a referendum is called, it will be the regulations which require to be scrutinised, rather than a Bill.

The PPERA does not provide Ministers with delegated powers in relation to holding referendums. Part VII "provides a framework which regulates national and regional referendums that take place pursuant to an Act of Parliament. However, in relation to a particular referendum, specific legislation is still required to set the date, the question and entitlement to vote at the referendum"1.

Section 2: Application of the Act

This section allows the referendum rules set out in the Bill to be applied at a specific referendum with modifications made by regulations. Such modifying regulations are subject to the affirmative procedure and Ministers must consult the Electoral Commission before laying any such regulations.

The section applies only where powers under Section 1 have been used to call a referendum. Should a referendum be held under an Act of the Scottish Parliament then that Act, or secondary legislation powers provided to Ministers under that Act, could make any modifications required for the specific poll.

The Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 contained such a provision with Section 1 subsections (5) to (7) giving Scottish Ministers power, by order approved by the Scottish Parliament, to modify the date of the referendum to a later date. This power could only be used where it would be impossible or impractical to hold the referendum on the original date.

There is no equivalent provision to Section 2 in the PPERA as that Act does not provide for Ministers to call a referendum by bringing forward regulations.

Section 37 of the Bill provides that Ministers are able to modify the provisions of the Act as they 'consider necessary or expedient' when in connection with legislative changes being made or proposed to other electoral or referendum legislation. Such electoral or referendum legislation would need to be concerned with the conduct of, campaigning in, or entitlement to vote at referendums or elections, or be legislation to give effect to recommendations made by the Electoral Commission.

Regulations used to modify the Act would be subject to the affirmative procedure.

Further information on electoral legislation changes which may affect this Bill can be found in the 'Franchise' section of this briefing.

Section 3: Referendum questions

Section 3 relates to the Electoral Commission's consideration of referendum questions. Sections 3(2) and 3(3) set out the steps which Scottish Ministers must take to consult the Electoral Commission and identify the timing of that consultation where secondary legislation sets the referendum question.

Section 3(2) applies to any Act of the Scottish Parliament which provides for the holding of a referendum and the wording of the question(s) is to be specified in subordinate legislation (see Section 3(1)) subject to the affirmative procedure. Under the provisions of this Bill, Ministers may provide for a referendum by regulations (Section 1) subject to the affirmative procedure.

Section 3(3) applies in the same circumstances at 3(2) but where the subordinate legislation on the wording of the question is subject to the negative procedure. Referendums called under Section 1 of this Bill would be provided for by regulations subject to the affirmative procedure. Section 3(3) would therefore be used in circumstances where a Bill was introduced to provide for a referendum on a specific issue.

Section 3(4) identifies the time that the Electoral Commission has to engage when a Bill is introduced to the Scottish Parliament which provides for the holding of a referendum and specifies the wording of the question.

In the case of a question being specified in secondary legislation, (Sections 3(2) and 3(3)), Scottish Ministers must consult the Electoral Commission on the wording of the question before laying, or as the case may be making, regulations. If the question is specified in primary legislation, the Electoral Commission must consider the wording of the question as soon as is reasonably practicable after the Bill is introduced.

If subordinate legislation provides for the question, Ministers must lay before Parliament a report containing any views as to the intelligibility of the question expressed by the Commission. If the referendum question is provided for in primary legislation, the Electoral Commission must publish a statement of views on the intelligibility of the question. The Electoral Commission usually takes around 12 weeks to consider the intelligibility of a question1.

Any statement which precedes the question on the ballot paper is taken as being part of the question and is therefore considered by the Electoral Commission. The Commission has previously interpreted its remit to extend to 'alternative drafting or to offer suggestions on how a particular question and its preamble might be framed2'.

These provisions are similar in effect to those set out in section 104 of PPERA.

Subsection (7) provides that Section 3 'does not apply in relation to a question or statement if the Electoral Commission have (a) previously published a report setting out their views as to the intelligibility of the question or statement, or (b) recommended the wording of the question or statement'.

The result is that where a question has previously been considered by the Electoral Commission, the Commission's view has neither to be sought again, nor re-communicated to Parliament at the time of laying regulations or, as the case may be, after the introduction of a Bill. There is no similar provision to Subsection 7 in PPERA, meaning that on each occasion the Electoral Commission is required to report on the referendum question.

Franchise

Section 4 of the Bill sets out those who are allowed to vote in a referendum. Known as the "franchise", this is the same as for local government elections and Scottish Parliament elections.

The franchise for local government elections is set out in Section 2 of the Representation of the People Act 1983. Section 11 of the Scotland Act 1998 provides that the franchise for local government elections in Scotland also applies at Scottish Parliament elections.

An individual is able to vote at the referendum held under the Bill's framework if, at the date of the poll they are:

aged 16 or over (as provided for under the Scottish Elections (Reduction of Voting Age) Act 2015);

a Commonwealth citizen, a citizen of the Republic of Ireland or a relevant citizen of the European Union (defined in Schedule 7 as a citizen of the EU who is not also a Commonwealth citizen or a citizen of the Republic of Ireland);

registered in the register of local government electors maintained under Section 9(1)(b) of the Representation of the People Act 1983 for any area in Scotland;

not subject to any legal incapacity to vote (age apart).

The Scotland Act 2016 transferred powers to the Scottish Parliament over the franchise for local government elections. The Scottish Government's 2018/19 Programme for Government included a commitment to introduce an Electoral Franchise Bill to “include provisions to extend the franchise for Scottish Parliament and Local Government elections to protect the franchise for EU citizens.”

It is anticipated that an Electoral Franchise Bill will also address the issue of prisoner voting, and will seek to enfranchise those on short sentences1. Under UK law, individuals serving a custodial sentence after conviction cannot vote. The ban does not extend to prisoners on remand. The provisions are set out in Section 3 of the Representation of the People Act 1983.

The European Court of Human Rights ruled in 2005 that the UK's position on prisoner voting was in breach of Article 3 of Protocol No 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights. In December 2018, the Scottish Government launched a consultation on prisoner voting. This followed an inquiry on prisoner voting by the Equalities and Human Rights Committee of the Scottish Parliament.

Section 3 of the Scottish Independence Referendum (Franchise) Act 2013 placed a specific bar on prisoner voting. The Referendums (Scotland) Bill does not make specific provisions for the disenfranchisement of prisoners.

"The intention is that the referendum franchise should continue to mirror the Local Government and Scottish Parliament franchise in future, taking into account the changes to be proposed in the forthcoming Electoral Franchise Bill to correct the ECHR incompatibility on prisoner voting." Referendums (Scotland) Bill Policy Memorandum, paragraph 36

Voting

Section 6 introduces Schedule 1 which makes provision relating to:

the manner of voting;

absent voters;

proxies and voting as a proxy;

registration;

postal voting;

the supply of register of local government electors.

Those entitled to vote in a referendum may do so in various ways as set out in paragraph 1 of Schedule 1. Voters are entitled to vote in person at a polling station; by postal vote; or by appointing a proxy.

Voters who have opted to vote by postal ballot or by proxy for local government or Scottish Parliament elections are deemed to be 'absent voters' under the Bill and this grants them an absent vote in a referendum.

The Bill includes a number of provisions absent from the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013. These include:

a requirement that any person appointed as a proxy is themselves registered to vote;

a restriction of the access to emergency proxy votes to electors who require it on grounds of disability, occupation, service or employment, where the grounds have arisen after the cut-off date for a normal proxy application;

checking of 100% of postal vote verification statements; and

that the deadline for non emergency proxy applications is 6 days before the date of the poll (this was 5 days in the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013).

Conduct rules

Sections 7 to 12 and Schedule 2 set out the rules for the conduct of a referendum. The provisions relate to the:

appointment of a Chief Counting Officer and other counting officers (Sections 7 and 8);

the functions of the Chief Counting Officer and other counting officers (Section 9);

the correction of procedural errors (Section 10);

expenses of counting officers (Section 11); and

Schedule 2.

For referendums conducted in the UK, under the provisions of the PPERA, the Chair of the Electoral Commission acts as the Chief Counting Officer. Section 5 of the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 provided for the Scottish Government to appoint the convener of the Electoral Management Board for Scotland as the Chief Counting Officer for the referendum. Section 7 of the Referendums Bill mirrors the 2013 Act.

Section 8 of the Bill requires for the appointment of a counting officer for each local government area. Again, Section 5 of the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 made similar provision. This is in line with PPERA which states that the Chief Counting Officer will appoint a counting officer for each relevant area in Great Britain. The Counting officers are usually the returning officers for the local authorities.

The Chief Counting Officer and other counting officers have the same responsibilities under Section 9 as under the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013.

Section 10 mirrors the provisions of the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013. The PPERA does not provide for the administration of the poll. The provisions in the European Referendum Act 2015, set out at Schedule 3, paragraph 9 are similar.

Section 11 deals with the expenses incurred by the Chief Counting Officer and other counting officers and their recovery of those expenses from Scottish Ministers. The provisions are broadly the same as those in the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2011. Ministers do have new powers to make regulations (subsection (3)) setting out the maximum amounts that the Chief Counting Officer and counting officers can claim. The similar provision in the 2013 Act was to be specified under an Order. Subsection (4) is a new provision which allows Ministers to pay more than the maximum amount in certain instances. Likewise subsection (5) is new and allows Ministers to, by regulations, provide for counting officers to submit accounts of expenses, specify the deadline for submitting accounts, and prescribe the form and manner in which accounts are to be submitted.

Schedule 2 deals with the good administration of the referendum for both the poll and the count. The PPERA does not provide for the administration of the poll and count and therefore contains no similar provisions.

Schedule 2 of the Bill is in line with the provisions in Schedule 3 of the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013. Rule 30 is updated to require the counting officer to supply a copy of the verification statement (which confirms that the number of ballots counted equals the number recorded) to any counting agent on request. The Bill also proposes changes to the checking of postal vote verification statements so that 100% are checked, previously it had been 20%.

Campaign rules

Section 13 of the Bill introduces Schedule 3 which sets out the rules around campaign conduct at a referendum. Detailed campaign rules governing the participation in referendum campaigns are there to ensure that campaigns in support of each referendum outcome are run in a fair and transparent way.

The campaign rules provided for in the Bill are similar to those used at the independence referendum in 2014 and the EU referendum in 2016.

Detail on some of the Bill's key provisions is set out below.

The referendum period

Before a referendum is held there is an official campaigning period known as the referendum period. During this period rules around campaigning and campaign spending apply.

The Bill allows for Scottish Ministers to specify the referendum period in regulations. This is provided for at Section 1(2)(c).

The PPERA does not state a specific length of time for the referendum period, although it has to be more than ten weeks and less than six months. The 1997 Scottish referendum, held prior to the PPERA being enacted, had a regulated period of 17 weeks. The AV referendum, which was legislated for under the PPERA rules, had a referendum period of 11 weeks.

The referendum period for the independence referendum in 2014 was 16 weeks. This was defined in Schedule 8 of the Scottish Independence Referendums Act 2013.

The 16 week period for the 2014 referendum followed Electoral Commission guidance following the UK referendum on AV voting in 2011 which proposed an extension from 10 to 16 weeks.

Permitted participants and designated organisations

Schedule 3, part 2 sets the rules for permitted participants and designated organisations.

Permitted participants

Paragraph 2 of schedule 3 requires any individual or organisation wishing to spend in excess of £10,000 on campaigning to declare to the Electoral Commission the referendum outcome for which they will be campaigning. The £10,000 limit is set by paragraph 19 of Schedule 3. This is the same limit as provided for in the PPERA, the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 20131 and the European Union Referendum Act 20152.

Any individual or organisation which has made a declaration to the Electoral Commission is deemed to be a 'permitted participant'. The list of permissible participants reflects the rules under the Transparency of Lobbying, Non-party Campaigning and Trade Union Administration Act 2014.

Designated organisations

The Electoral Commission is responsible for designating one permitted participant (after an application has been made) for each or any of the possible outcomes in the referendum. It is that permitted participant which will act as the "designated organisation", representing all those campaigning for the outcome in question.

The Bill proposes that the deadline for applications for designation will be 12 noon on the last day for applications, rather than 12 midnight as was provided for in the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013.

Under the terms of the PPERA (Section 108), the Electoral Commission is responsible for registering permitted participants and designating the lead campaign organisations for a UK referendum in a similar way.

One sided-designation

Under the proposals in the Bill, the Commission can designate a permitted participant in relation to one of the possible outcomes whether or not a permitted participant is designated in relation to any of the other possible outcomes.

The Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 permitted the Electoral Commission to designate for one of the sides of the campaign even if the other side does not put forward an organisation for designation.

Under PPERA, the Electoral Commission may designate from the permitted participants a lead organisation for each side, but, if an organisation does not put itself forward to represent one of the sides, there can be no designated organisation for either side. The European Union Referendum Act 2015 did, however, amended PPERA provisions for the EU referendum so that the Electoral Commission was able to appoint lead campaign groups for each side of a referendum campaign or for one side only3.

Designation is important under PPERA as designated organisations are entitled to financial support. Financial support is not available to designated organisations under the proposals set out in the Referendums (Scotland) Bill. This follows the precedent set in the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 which was in line with the Scottish Government's proposals in its 2012 consultation Your Scotland, Your Referendum4 .

It is thought that one-sided designation was used as a tactic in the 2011 Welsh Referendum. The lack of a designated "No" campaign meant that the "Yes" campaign could not be designated and therefore did not receive financial assistance, or other support such as referendum campaign broadcasts, free use of rooms for public meetings and free mailings5.

Common working

Provisions to allow campaigners to work together as part of a common plan (Schedule 3 paragraph 21) and for the expenses incurred to be counted only as spending by the designated organisation also fall away in the event that there is a designated organisation for only one possible outcome of the referendum. These provisions are a mix of those set out in the EU Referendum Act 2015 and the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013.

The Electoral Commission and the House of Commons Public Administration and Constitution Committee have proposed a review of the working together rules provided for in PPERA. This was after some smaller campaigns had effectively frozen campaigning in the EU referendum for fear of breaching the rules. The Electoral Commission's view is that what constitutes common working is not sufficiently clear in PPERA. Section 26(5) of the Bill provides that the Electoral Commission guidance must provide guidance on what constitutes a common plan.

The Bill also includes a requirements that campaigners set out the names of those they worked with, and how much each spent, in a post-referendum spending report .

Campaign finance: spending and expense limits

Schedule 3 paragraph 12 defines the referendum expenses which may be incurred by permitted participants as:

referendum campaign broadcasts;

advertising of any nature;

unsolicited material addressed to voters;

publications (as set out in Schedule 3 paragraph 27);

market research and canvassing;

the provisions of services and or facilities (e.g. press conferences;)

transport; and

rallies and other events like public meetings.

These are in line with those set out in the PPERA (Schedule 13, paragraph 1); those set out in the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 (Schedule 4 part 3), and those imposed at the EU referendum in 2016.

Under the provisions of the Bill, the Electoral Commission is able, from time to time, to issue a revised code of practice giving further guidance on the kinds of expenses which it deems to fall within or outwith the spending limits. The Commission's guidance for the EU referendum indicated that the kind of costs which are not deemed to count towards the spending limit as:

volunteer time;

permanent, fixed term or temporary staff costs where the staff member has a direct contract with the registered campaigner;

people's, food travel and accommodation costs while they campaign unless the registered campaigner reimburses people or pays directly;

costs incurred in providing security at public events;

expenses (except adverts) in respect of publication in a newspaper or periodical; and

designated lead campaigners’ use of public rooms or free mailing1.

Paragraph 20 of Schedule 3 sets the expense limits for permitted participants. Expense limits are those which apply in the referendum period.

The limit for a permitted participant which is also a designated organisation is £1,500,000. This is the same limit as was set in the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 (Schedule 4, paragraph 19).

The Bill provides that spending limits for permitted participants which are also qualifying political parties will be calculated using a formula. The formula is based on the party's share of the constituency and regional votes at the most recent Scottish Parliament general election.

| Political party | Spending limit (£) |

|---|---|

| Scottish National Party | 1,332,000 |

| Scottish Conservatives | 672,000 |

| Scottish Labour | 630,000 |

| Scottish Liberal Democrats | 201,000 |

| Scottish Greens | 150,000 |

When compared to the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013, the Bill changes the way that the expenses limits are calculated (Schedule 3, paragraph 20(2)). Rather than rounding the constituency and regional percentages to one decimal place before adding together to calculate the relevant per cent, the constituency and regional percentages should be added together before rounding to two decimal places. This change is in line with recommendations from the Electoral Commission made ahead of the 2014 independence referendum2.

The relevant period: restrictions on public authorities

Section 125 of the PPERA sets out the restrictions which apply to Ministers, and public bodies, during the 28 day period preceding referendums. This 28 day period – known as the "relevant period" or, informally, as the "purdah period" – is treated in a way similar to the 28 day period prior to elections, when Ministers and public bodies refrain from publishing material which could have a bearing on the election. Purdah can be longer: for example, the 2015 General Election campaign had a period of 39 days.

The Bill follows the PPERA with paragraph 27 of Schedule 3 placing certain restrictions on the publication of any material by Scottish Ministers, the Scottish Parliament and certain public authorities in the 28-day period ending with the date of the referendum.

During this time material providing general information about the referendum, dealing with issues raised by the question to be voted on in the referendum, putting any arguments for or against a particular answer to the question to be voted on, or which is designed to encourage voting in the referendum cannot be published by Scottish Ministers or the Scottish Parliament. This rule does not apply to information made available following a specific request; specified material published by or under the auspices of the Scottish Parliament Corporate Body; any information from the Electoral Commission, a designated organisation or the Chief Counting Officer or any other counting officer; or to any published information about how the poll is to be held.

The Electoral Commission has repeatedly called for an extension to the purdah period. After the 2011 AV referendum the Commission recommended that "the prohibition on publication of promotional material about the referendum by publicly-funded bodies or individuals should commence at the same time as the beginning of the referendum period for future referendums1'.

In its report after the 2014 independence referendum the Commission recommended that in future "relevant governments...should publicly commit to and refrain from, in practise, any paid advertising, including the delivery of booklets to households, which promotes a particular referendum outcome for the full duration of the referendum period.2"

Dr Alan Renwick of the Constitution Unit has also argued for reform of the current state of affairs which is "not satisfactory" when, in the case of the EU referendum, "the intensive campaign clearly lasted for more than four weeks, and therefore, the Government was able to be involved in April and May"3.

The House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee considered issues relating to the relevant period in its inquiry 'Lessons learned from the EU referendum'. Further detail on the Committee's findings and recommendations can be found in this briefing under the section 'Lessons from referendums'.

Donations

The Bill requires permitted participants to provide reports to the Electoral Commission ahead of the poll on all donations and loans received. Donations made to permitted participants to support them in campaigning must be declared and a donation is deemed to include money and or other property.

The rules are based on those in the Scottish Independence Act 2013 and the PPERA. The Bill defines what donations are allowed, who is allowed to make a donation and what a permitted participant must do to record donations over the value of £500.

Donations to permitted participants can only be accepted from 'permissible donors. The Bill provides that these include:

individuals registered on the electoral register anywhere in the UK;

companies registered under the Companies Act, incorporated in the EU and that conduct business in the UK;

registered parties;

trade unions;

building societies;

limited liability partnerships;

friendly societies; and

unincorporated associations carrying on business or other activities wholly or mainly in the UK and having their main office in the UK.

The list of permissible donors reflects the rules under the Transparency of Lobbying, Non-party Campaigning and Trade Union Administration Act 2014.

Donations to political parties are covered by the PPERA. The Bill does not add additional rules to regulate donations to registered political parties in the event of a referendum.

How does the Bill compare to existing legislation?

A narrative overview of provisions made by existing referendum legislation in the UK and in Scotland is provided below. The Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 and the Scottish Independence Referendum (Franchise) Act 2013; the PPERA, and the European Union Referendum Act 2015 are discussed.

The Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 and the Scottish Independence Referendum (Franchise) Act 2013 together provided for the 2014 referendum. They are therefore comprehensive in their provisions and the most comparable to the Bill.

The PPERA is discussed as the closest legislative comparison of referendum framework legislation in the UK. However, it provides neither for a referendum, nor for the administration of a referendum.

The European Union Referendum Act 2015 is the most recent primary legislation to provide for a referendum held under the framework set out in the PPERA.

The Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 and the Scottish Independence Referendum (Franchise) Act 2013

The Bill reflects much of the Scottish Independence Referendum Act in relation to the conduct and campaign rules.

The Bill mirrors the franchise for the 2014 referendum, with the notable exception that the bar on prisoners voting set out in the legislation for the 2014 referendum is not included in the Bill.

The central difference in the provisions of the Bill are those contained in Sections 1-3. These give Ministers powers which they did not have, or did not have to the same extent, under the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013.

The Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000

Before the PPERA was enacted there was no standing legislation to govern the rules around referendums. Rather, each referendum was held under an Act of Parliament which set out the specific rules for that campaign and allowed the poll to take place.

Part VII of the PPERA sets out the rules which underpin the process for running a national or regional referendum, but not the electoral administration required for it. The rules set out in the PPERA are supplemented by additional primary and secondary legislation instigating the referendum in question.

Under PPERA there is a certain basic minimum regulatory framework that governs any referendum that is held under an Act, but it leaves space for particular bespoke regulations governing, for example, the question itself, the date and various other ancillary matters.

William Norton, Legal Director, Vote Leave in oral evidence to the House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, 1 November 2016House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee. (2016, November 1). Oral evidence to the inquiry 'Lessons learned from the EU referendum', Q199. Retrieved from http://data.parliament.uk/WrittenEvidence/CommitteeEvidence.svc/EvidenceDocument/Public%20Administration%20and%20Constitutional%20Affairs%20Committee%20/Lessons%20learned%20from%20the%20EU%20Referendum/oral/42639.html [accessed 6 June 2019].

The PPERA sets out information on campaign regulation, such as controls of campaign spending and publications, and the referendum period (for example, when certain restrictions apply). At Section 101, the Act, defines a referendum as a "referendum or other poll held, in pursuance of any provision made by or under an Act of Parliament, on one or more questions specified in or in accordance with any such provision".

Under the PPERA, the Electoral Commission's role in the regulation of referendums is set out. The Commission is given responsibility for:

commenting on the wording of the referendum question;

registering campaigners;

designating lead campaign organisations;

regulating campaign spending and donations;

giving grants to lead campaign organisations;

the conduct of the poll;

announcing the result.2

The Electoral Commission also reports on the administration of the referendum.

Under the PPERA the Electoral Commission must consider the Government’s proposed wording of the referendum question(s) and publish a statement of its views as to the intelligibility of that question or questions. This is not, however, a judgement which is binding on the Government. The House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution raised concerns about this in its 2010 report on referendums and recommended that:

The Electoral Commission should be given a statutory responsibility to formulate referendum questions which should then be presented to Parliament for approval

House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution. (201, April 12). 12 Report of Session 2009-10, Referendums in the United Kingdom, paragraph 154. Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200910/ldselect/ldconst/99/99.pdf [accessed 04 June 2019]

The PPERA does not set the date of the referendum; the question, or the franchise. The individual legislation setting up each referendum specifies these matters and allows for the required elements of electoral law for the poll and count to occur.

Spending limits were breached during the EU referendum campaign. This has led to calls for legislation (principally the PPERA) to be reviewed and updated4.

The Cambridge Analytica scandal has also prompted calls for the reform of PPERA as it regulates political parties' campaigning, and no longer reflects the realities of campaigning in today's digital world5.

The European Union Referendum Act 2015

The Referendum Act 2015 provided for a referendum on the UK's membership of the EU to be held by 31 December 2017. The European Union Referendum (Conduct) Regulations 2016; the European Union Referendum (Date of Referendum) Regulations 2016, and the European Union Referendum (Voter Registration) Regulations 2016 also formed part of the bespoke package of legislation to govern the referendum.

The Electoral Commission's official report of the referendum was that "the legal structure for the referendum was clear" and that "given the high profile nature of the referendum, the Chief Counting Officer, the Electoral Commission and electoral officials across the UK managed the referendum very well.1"

Lessons from referendums

Since the 1975 referendum on the question of the UK's membership of the European Community, there have been two further nationwide referendums to date. One in 2011, used to address the question of whether elections to the House of Commons should change from first past the post to the alternative vote; the other in 2016 to decide on the UK's continued membership of the European Union.

There has been a steady increase of the use of referendums globally. Between 1990 and May 2018 Switzerland held 261 referendums; Italy held 56; Ireland 27; New Zealand 14; Denmark 7 and Poland 101.

Referendums are seen as a means to engage the electorate and a valid mechanism for deciding questions of importance. Although concern has equally been raised around the 'significant drawbacks' of referendums2.

the referendum can be a useful way to engage citizens in processes of constitutional change if referendums are well designed and well regulated.

Professor Stephen Tierney, Professor of Constitutional Theory, University of Edinburgh House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee. (2016, September). Written evidence to the PACAC inquiry 'Lessons learned from the EU Referendum'. Retrieved from http://data.parliament.uk/WrittenEvidence/CommitteeEvidence.svc/EvidenceDocument/Public%20Administration%20and%20Constitutional%20Affairs%20Committee%20/Lessons%20learned%20from%20the%20EU%20Referendum/written/36892.html [accessed 06 June 2019]

In the UK referendums have been used to decide constitutional questions.

Consideration has been given to referendums and the legislative basis for them in the UK Parliament and by a number of expert organisations. An overview of that work is below.

House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution

In November 2009 the House of Lords' Constitution Committee began an inquiry into 'the role of referendums in the UK's constitutional experience'.

In its report the Committee concluded that "there are significant drawbacks to the use of referendums". The Committee was particularly concerned over the tactical use of ad hoc referendums by governments.

It was the Committee's view that referendums 'are most appropriately used in relation to fundamental constitutional issues'1, and that 'crossparty agreement should be sought as to the circumstances in which it is appropriate for referendums to be used'.2

The Committee's position was that referendums had both positive and negative features.

| Positive features of referendums | Negative features of referendums |

|---|---|

| enhance the democratic process | are a tactical device |

| can be a “weapon of entrenchment” | are dominated by elite groups |

| can “settle” an issue | can have a damaging effect on minority groups |

| can be a “protective device” | are a conservative device |

| enhance citizen engagement | do not "settle" an issue |

| promote voter education | fail to deal with complex issues |

| voters are able to make reasoned judgments | tend not to be about the issue in question |

| are popular with voters | voters show little desire to participate in referendums |

| complement representative democracy | are costly |

| undermine representative democracy |

At the time of the Lords' inquiry, only one referendum had been held under the PPERA which was the question on whether to establish an Elected Regional Assembly in the North East of England in November 2004. The Committee concluded that:

Any assessment of the overall regulatory framework relating to referendums and the role of the Electoral Commission are theoretical as neither has been tested in a UK-wide referendum. We therefore recommend that after the next UK-wide referendum:

• The Electoral Commission should analyse its experience (as it did for the 2004 North East referendum) and make recommendations for change to the regulatory framework and its role; and

• There should be thorough post-legislative scrutiny of the PPERA at an early date. We are sympathetic to the changes to the legislative framework suggested by the Electoral Commission following its analysis of the 2004 North East referendum. We recommend that the Government take steps to ensure that they are implemented.

House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution. (2010, April 7). 12 Report of Session 2009-10, Referendums in the United Kingdom, paragraph 154. Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200910/ldselect/ldconst/99/99.pdf [accessed 04 June 2019]

The AV referendum in 2011 and the EU referendum held in June 2016 are the only UK-wide referendums held since the House of Lords report of 2010.

The Law Commissions

In 2014, the Law Commission, Scottish Law Commission and Northern Ireland Law Commission launched a joint consultation on electoral law.

The remit of the consultation was the 'law governing the conduct of elections and referendums in the United Kingdom, including the legislative framework, rules governing electoral registration, polling, the count, campaign regulation, electoral offences and legal challenge'1.

The Law Commissions described the electoral law landscape as 'complex, voluminous and fragmented'. Its position is that that electoral laws should be 'presented within a rational, modern legislative framework, governing all elections and referendums within scope; and secondly, that electoral laws are modern, simple, and fit for purpose'2.

The opinion of the Commissions was that it was "desirable to produce a set of generic referendum conduct rules that could simply be applied with minimal adaptation in the instigating Act to the referendum it calls. This would "reduce the current complexity of the law, speed up the legislative process and make the conduct rules accessible in advance by electoral administrators"3.

Chapter 14 of the Law Commissions' report sets out their joint recommendations on referendums. The Commission made two recommendations in relation to national referendums.

Primary legislation governing electoral registers, entitlement to absent voting, core polling rules and electoral offences should be expressed to extend to national referendums where appropriate.

Secondary legislation should set out the detailed conduct rules governing national referendums, mirroring that governing elections, save for necessary modifications.4

The Law Commissions' recommendations have been supported by the Electoral Commission, most recently in its official report on into the EU Referendum. The first recommendation of that report being that "the UK Government should establish a clear framework for the conduct and regulation of future referendums"5.

House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee

On 14 July 2016 the House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee (PACAC) launched an inquiry into the lessons that can be learned from the European Union referendum, and how they can inform the conduct of future referendums. The Committee's report was published on 7 March 2017.

The inquiry focused on 4 broad areas

the role and purpose of referendums and the relationship between direct and parliamentary democracy;

the effectiveness of the existing legislation regulating the conduct of referendums;

the Electoral Commission and the administration of the referendum; and

the role of the machinery of government during the referendum.

Overall, the evidence submitted to PACAC emphasised the 'design rather than the principle', of referendums1. This reflected the view that rules and regulations have to have the confidence of campaigners and the electorate. This was reflected in the written evidence submitted to the inquiry by Professor Stephen Tierney from the University of Edinburgh:

Given the heat which referendums can generate and the risk of ill-tempered and potentially bitter referendum campaigns, it is of the highest importance for the future of the country afterwards that the process of the referendum itself be fair and be seen to be so by both sides: that the result is agreed to, even if it is not agreed with, by losers as well as winners.

Professor Stephen Tierney, Professor of Constitutional Theory, University of EdinburghProfessor Stephen Tierney. (2016, September). Written evidence to the PACAC inquiry 'Lessons learned from the EU Referendum'. Retrieved from http://data.parliament.uk/WrittenEvidence/CommitteeEvidence.svc/EvidenceDocument/Public%20Administration%20and%20Constitutional%20Affairs%20Committee%20/Lessons%20learned%20from%20the%20EU%20Referendum/written/36892.html [accessed 06 June 2019]

The Committee's report, therefore, emphasised the need for a clear question and a clear outcome.

"If the results of referendums are to command the maximum of public support, acceptance and legitimacy, then they must be held on questions and issues which are as clear as possible. Voters should be presented with a choice, where the consequences of either outcome are clear."3

The Committee heard from the Electoral Commission that it would be useful to update PPERA, so that there is 'one up-to-date set of rules' for referendums, meaning that 'Parliament would be debating the need for a referendum, the content of a referendum question, [and] the date of a referendum'4.

Key recommendations made by the Committee which are relevant to provisions in the Referendums Bill are:

Support for the proposals put forward by the Law Commissions to consolidate the law relating to referendums. The Committee concluded that "the basic regulatory framework provided by the PPERA would be strengthened by the establishment of a generic conduct order that can be applied for future referendums". This would end the process of "reinventing the wheel" at each referendum and "provide greater stability in the constitutional and legal framework for referendums" as well as providing clarity for campaigners and the electorate5;

An extension of the purdah period of 28 days (Section 125 of PPERA) so that the protections to ensure fairness are in place for the full duration of a referendum period (a 10 week minimum in the PPERA). The purdah period was deemed to be "too short a period in the context of the much longer official campaign period"6;

A review of working together rules by the Electoral Commission to prevent smaller campaigns from freezing activity for fear of breaching the rules.

The report also noted that "The Electoral Commission's dual role as a regulator and key delivery agent for referendums could pose potential difficulties.7" In the 2011 AV referendum and the 2016 EU referendum, the Electoral Commission had a dual role as both the regulator of the campaign, and as the body tasked with delivering the referendum administratively. There was some comment as to whether that meant there was a conflict of interest between the two roles.

In the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 these roles were separated, with the Electoral Commission still regulating the designated participants, campaigns and so on, but the chair of the Scottish Electoral Management Board acting as Chief Counting Officer and delivering the poll administratively. The Referendums (Scotland) Bill continues that separation of powers evident in the 2013 Act.

The Independent Commission on Referendums

The Independent Commission on Referendums, established by the Constitution Unit at UCL, reported in 2018 and concluded that:

Referendums now constitute an important part of how democracy functions in numerous countries around the world. They are used with increasing frequency, including to address some of the most fundamental political and constitutional questions. It is essential, therefore, that careful consideration be given to how they operate and how they fit within the rest of the democratic system.

The Independent Commission on Referendums, Constitution Unit UCL. (2018, July). No title Retrieved from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/sites/constitution-unit/files/182_-_independent_commission_on_referendums.pdf [accessed 04 June 2019]

The Commission concluded that referendums should be conducted in line with two overarching objectives: the alternatives should compete on a level playing field; and voters should be able to find the information they want from sources they trust. A range of proposals were put forward as a means to achieving the two overarching objectives. These were:

current restrictions on government involvement in referendum campaigns should be extended to cover the whole campaign period, but narrowed in scope to target the behaviour that is of concern during referendums – that is, campaigning for or against a proposal;

lead campaigners should be designated as early as possible, to give campaigners time to prepare effectively;

measures should be taken to enhance the transparency of campaign spending and the accountability of campaigners for that spending;

the Electoral Commission should review how any space provided to campaigners in the Commission's voter information booklet is best used;

more should be done to enable the work of broadcasters, universities, factcheckers and other independent organisations in facilitating access to balanced information; and

methods for fostering citizen deliberation on referendum issues and disseminating its results should be piloted2.

The Commission also produced a checklist for those considering calling a referendum setting out points which should be considered.

Is the subject matter suitable for a referendum? Can it be considered a major constitutional issue?

Is a referendum the best way of involving citizens in the decision in question, or might some other means of public consultation serve at least as well, or better?

Is interest in the subject adequate to ensure a high level of turnout?

Has the topic concerned previously been subject to considerable public debate and deliberation?

Has it been carefully considered by bodies such as parliamentary committees?

Have there been opportunities for civil society groups to comment and help develop proposals?

Have there been opportunities for citizens to contribute to the development of the proposals through bodies such as citizens’ assemblies?

Are the alternatives clear, or do they need further consideration and elaboration?

If there are more than two options for change, has the possibility of holding a multi-option referendum been seriously considered?

Will it be possible, in advance of a referendum, for detailed proposals for change to be set out in the enabling legislation?

Will it be clear to legislators after the referendum what to enact, or is there any risk of uncertainty, and conflict with the public vote?

The Commission concluded that "if the answer to any of the questions...is no, then the referendum should not be held at that point." In making recommendations, the Commission recognised that to implement them would "demand a cultural change in terms of how referendums are used and the circumstances in which they are proposed.3"

Recommendation 20 from the Commission related to legislation specifically, stating that:

Any legislation enabling a pre-legislative referendum should set out a process to be followed in the event of a vote for change. If a government does not produce a detailed White Paper on the proposals for change, a second referendum would be triggered when the legislation or treaty implementing the result of the first referendum has passed through the relevant parliament or assembly. In cases where a government does produce a White Paper detailing what form of change it expects to secure, the second referendum would be triggered only in the event that there is a ‘material adverse change’ in circumstances.