Brexit and veterinary workforce pressures - A perfect storm?

This briefing examines Scotland's veterinary workforce in the agricultural sector and government services. It highlights their important role in animal health and welfare, trade, food standards and public health. The briefing identifies existing workforce pressures and the potential for Brexit in creating uncertainty for migrant vets and increased workloads.

Executive Summary

The latest statistics show that there are 2,551 vets practising in Scotland. Fifteen-percent of these vets are non-UK EU nationals.

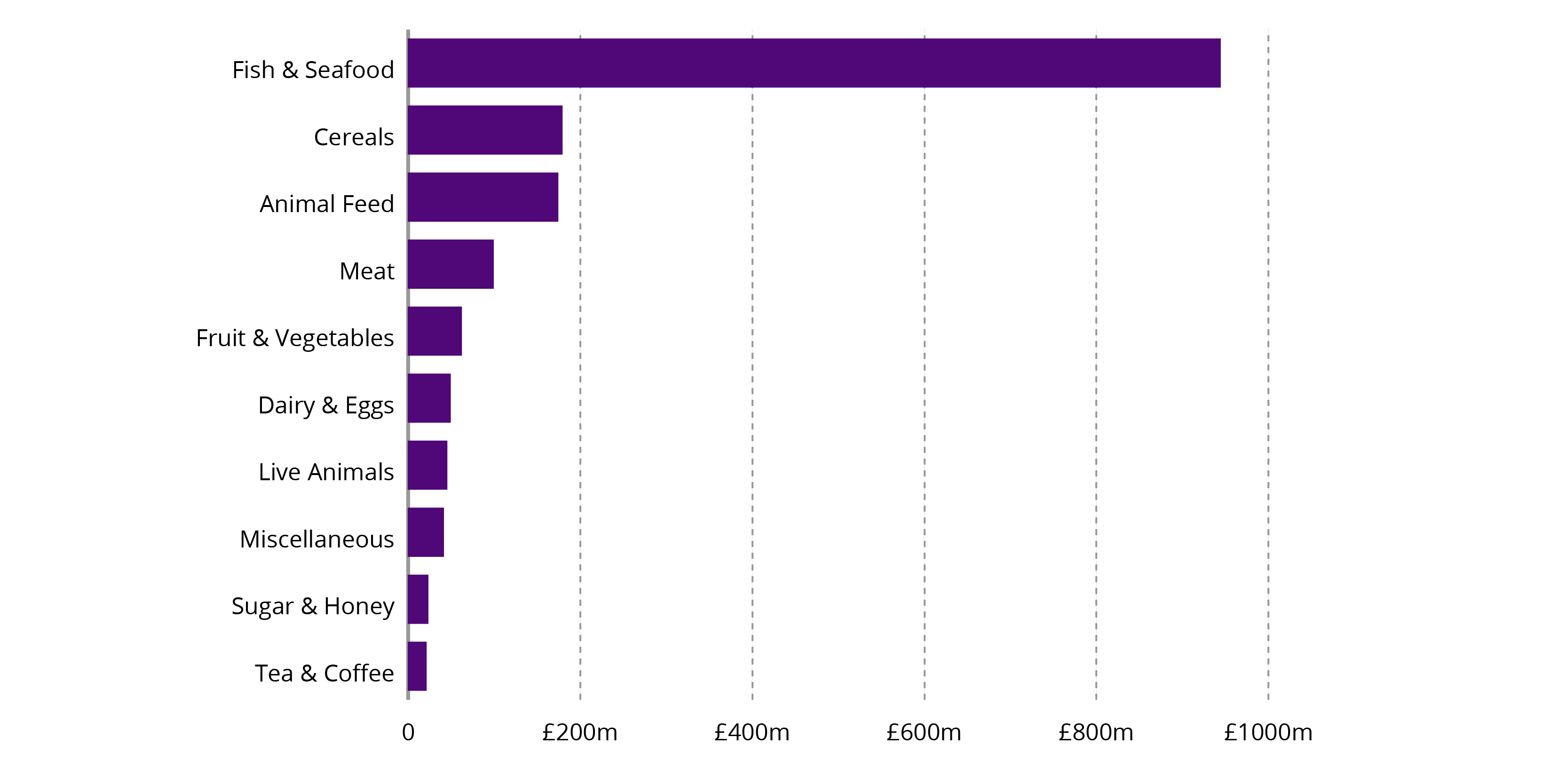

Food and drink is Scotland's largest export industry worth £6 billion in 2017. Trade in live animals and animal products accounts for just under 20% of these exports. Veterinary surgeons (vets) play a vital role in ensuring the quality and safety of such exports.

Prior to the 2016 referendum on exiting the EU, the veterinary profession was already facing challenges in recruiting and retaining staff. Brexit has the potential to add further uncertainty for EU nationals, with associated workforce pressures.

Government service related roles associated with meat hygiene and trade are particularly vulnerable due to a higher proportion of EU migrant vets working in this area.

Thirty four percent of vets working in government services in Scotland are non-UK EU nationals. Within this sector, non-UK EU nationals account for 75% of vets working in Scottish abattoirs.

A reduction in vets working government services could increase the risk of food fraud, animal welfare breaches and threaten public health.

Brexit also has the potential to increase the requirement for veterinary export health checks by up to 325%.

In 2011, veterinary surgeons were removed from the Home Office Shortage Occupation List which requires that jobs are advertised to European Economic Area (EEA) residents before countries outside of the EEA.

Most vets working in government service roles earn below the current Tier 2 visa category salary threshold of £30,000.

UK veterinary schools do not currently have the capacity to provide the number of graduates required to ensure an adequate post-Brexit workforce.

Introduction

The veterinary profession in Scotland is relatively small but plays a key role in Scotland's rural economy and international trade. This briefing focusses on vets working in the government services sector. Government vets (known as 'Official Veterinarians') provide an important service to the public, from disease control to safeguarding animal health and welfare. They work in a number of UK Government departments, agencies, the Scottish Government and Northern Ireland Executive. They are integral to the production and trade of animal products by ensuring animal welfare standards are upheld and that food is safe for public consumption.

Food and drink is Scotland's largest international export industry. In 2017, it accounted for £5.9 billion of Scotland's international exports. Of these exports, just under 20% (£1.1 billion) were exports of live animals and animal products. The success of these exports is built on Scotland's reputation for producing quality products through ensuring a high standard of food hygiene, animal health and welfare.

The table below provides a summary of how agriculture and the veterinary profession varies across the UK.

| Agriculture GVA (% of total)1 | Livestock (number per ha. agricultural holdings)1 | Number of vets2 | Vet Schools | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheep | Pigs | Cattle | ||||

| Scotland | 0.7 | 1.21 | 0.06 | 0.32 | 2,277 | 2 |

| England | 0.5 | 1.68 | 0.43 | 0.60 | 18,021 | 5* |

| N. Ireland | 1.1 | 2.00 | 0.59 | 1.64 | 808 | 0 |

| Wales | 0.9 | 5.85 | 0.01 | 0.68 | 1,180 | 0 |

The regulation of the veterinary profession in Scotland is a reserved matter. However, access to veterinary services is an important part of animal health and welfare. In order to ensure the continued provision of an adequate supply of suitably trained vets, covering all areas of the country, the Scottish Government takes part in the Great Britain-wide Vets and Veterinary Services Working Group, maintained by Defra. The group consists of representatives of the veterinary profession, animal welfare organisations, the farming industry, and Government officials.1

The role of vets

The veterinary profession is diverse and veterinary surgeons (VSs) carry out a wide range of functions in both the public and private sector. According to the British Veterinary Association, these include:

Production animal clinical practice: providing preventive healthcare and treatment for livestock, carrying out surveillance, promoting good biosecurity, boosting productivity.

Abattoirs and the food supply chain: securing public health, food safety, animal welfare, public health and enabling trade in animals and animal products.

Aquaculture: ensuring fish health and welfare and biosecurity. Diagnosis, treatment and prescription of medicines.

Companion animal and equine practice: looking after pets, leisure and sport animals.

Universities and research: teaching the next generation of veterinary surgeons and producing research. Contributing to industry and technology ensuring the UK remains competitive.1

As mentioned previously, this briefing focusses on the role of veterinarians working in government service roles related to trade in animal products and meat hygiene. It does not cover the impact on small animal (pets) practice, private clinical practice and equine practice. However, workforce statistics provided by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) in the section below include all vets including those working in private clinical practice.

Overview of the current workforce

According to statistics provided to SPICe by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS), there are currently a total of 2,551 practising veterinary surgeons whose registered address is in Scotland. Of these, a significant proportion are non-UK EU citizens (15%) and/or qualified in a non-UK EU country (14%).

In written evidence provided to the Scottish Affairs Committee inquiry on immigration and Scotland, the British Veterinary Association (BVA) stated:

The veterinary profession is relatively small, but its reach and impact are significant; the ramifications of a loss of even a small percentage of the workforce would be great.

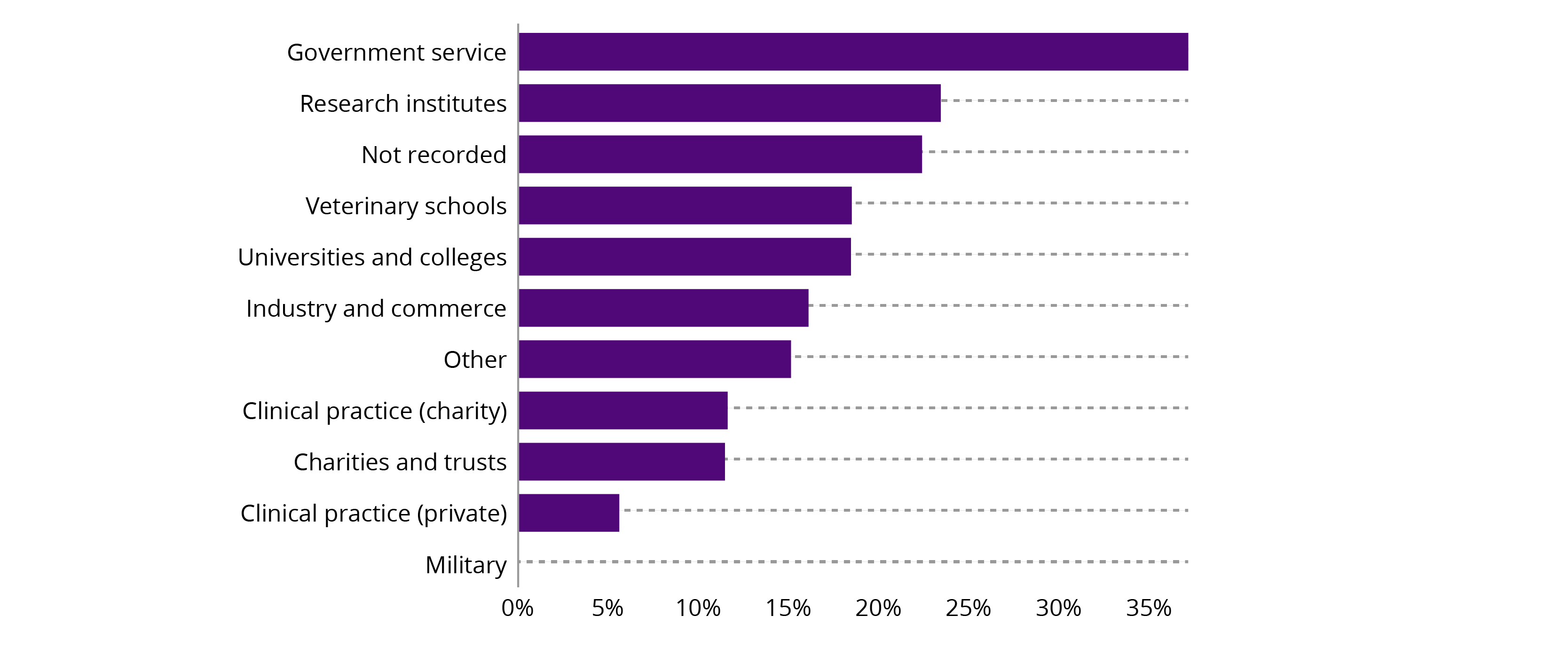

Any workforce loss as a result of Brexit is likely to have greater impacts on those areas of the veterinary profession with a high proportion of vets who are non-UK EU citizens. The chart below provides a breakdown of the proportion of non-UK EU vets registered in Scotland working in different sectors of veterinary practice.

Government services is one area of the veterinary profession that relies heavily on EU nationals. The chart above shows that 34% of practising vets registered in Scotland are non-UK EU citizens. Official Veterinarians (OVs), perform work on behalf of the government. The work performed by OVs is normally of a statutory nature (i.e. is required by law) and is often undertaken at public expense.1

Workforce pressures

A British Veterinary Association Voice of the Veterinary Profession (Voice) UK-wide survey conducted in early 2015 revealed that two-thirds of practices looking to recruit in the previous year took more than three months to fill their vacancies for veterinary surgeons. Of these, 10% took more than six months and 7% were forced to withdraw the role because of a lack of suitable candidates.1

In December 2017, The British Veterinary Association (BVA) stated the following in a written submission to the Scottish Affairs Committee's Immigration and Scotland inquiry.

Before the EU referendum, veterinary practices were reporting difficulties in recruiting. This problem has been compounded following the Brexit vote, as non-UK EU vets are faced with considerable uncertainty about their futures.

Whilst retention has been recognised as a pre-Brexit problem it has been exacerbated since the referendum due to uncertainty about ongoing rights to employment. Considering the projected demand for vets, it is impossible for this to be met in the short term domestically. There will be an ongoing need to meet the demand for veterinary professionals from outside the UK.2

Existing pressures are highlighted in a summary, published in July 2018, of a BVA workforce roundtable which includes the following:

Expectation/reality mismatch - vet schools have a role in better preparing students for the realities of veterinary practice but there was a feeling that universities are not always adequately equipping students for the world of work.

Gender – there was disagreement over whether and how the ‘gendered nature’ (i.e. the changing gender balance) of the profession was having an impact. Some employers expressed concern that women are less interested in farm and equine positions, but this was challenged by others.

Geography – Employers generally find it harder to recruit in more rural areas.

Work/life balance – stress and long hours are still widespread. The profession is not currently in a position to offer work/life balance because of the shortage of vets – described as a “chicken and egg situation”

Locuming – people are cherry picking their hours (i.e. choosing not to work evenings and weekends) and increasingly able to name their price. 3

Implications of a post-Brexit vet shortage

The previous section underlined concerns that the uncertainty of Brexit may add to existing workforce pressures. Broadly speaking, there are two key factors at play:

The reliance on EU migrant workers, particularly in government services.

The potential increase in workloads required of vets in relation to animal health and welfare and the export of live animals and animal products. This is especially the case under a no deal Brexit.

These issues are discussed further below.

Attracting and retaining migrant vets after Brexit

After the EU Referendum in June 2016, organisations representing the veterinary profession were quick to acknowledge the potential impact of Brexit on an already strained workforce. Not only is it important to maintain current staffing levels, it is anticipated that Brexit will require an increase in workforce capacity.

Shortly after the referendum, the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) commissioned the Institute for Employment Studies to conduct research to gain a better understanding of the intentions of non-UK EU vets working in the UK.

Three online surveys were conducted over a two-year period to gather the views and intentions of veterinary surgeons (VSs) and veterinary nurses (VNs). Of those VSs responding to the survey:

18 per cent are actively looking for work outside the UK;

32 per cent are considering a move back home;

40 per cent think they are now more likely to leave the UK.

In 2011, the Migration and Advisory Committee made an assessment that there were sufficient VSs to meet demand. This resulted in the veterinary profession being removed from the Home Office Shortage Occupation List. The BVA have commented that "this move did not anticipate the possible loss of non-UK EU graduates from the veterinary workforce."1

There are concerns that the veterinary profession will not be recognised as an area of priority in post-Brexit immigration policy. In written evidence provided to the Migration Advisory Committee, the BVA stated the following:

...as a first step, we ask that the veterinary profession is restored to the Shortage Occupation List. A future immigration system must prioritise the veterinary profession. The Government should consider the economic and social impact the profession has, beyond its relatively small size.2

The House of Lords European Union Committee noted in the report Brexit: farm animal welfare:

We note the overwhelming reliance on non-UK EU citizens to fill crucial official veterinary positions in the UK, and call on the Government to ensure that the industry is able to retain or recruit qualified staff to fill these roles post-Brexit.

The UK Government is proposing a single, unified immigration system to apply to everyone who wants to come to the UK after Brexit. The system will be based on the current immigration rules for non-EU nationals, with many changes. Proposals include expanding the current Tier 2 (General) visa category which applies to non-EU citizens to EU citizens. The salary threshold for eligibility for this visa is currently set at £30,000.3

Starting salaries for Official Veterinarians monitoring standards, food safety and animal health and welfare in abattoirs are in the mid-£20,000s. The BVA has warned that imposing a £30,000 threshold could jeopardise the capacity of this sector of the workforce.4

The BVA state the following in its evidence to the Migration Advisory Committee:

We further recommend that there is no minimum earning cap for veterinary surgeons applying for working visas. Veterinary surgeons are skilled professionals who may choose to work in the UK for reasons other than remuneration. Further, veterinary surgeons make a significant contribution to society through their work in public health, securing animal health and welfare, and facilitating trade through the role in certification; these are national goods that cannot be assessed in terms of individual contributions to the exchequer.5

The UK Government has stated it will undertake "an extensive programme of engagement with a wide range of stakeholders across the UK...before taking a final decision on the level of salary thresholds."6

An end to preferential access for EU vets

Under the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 both UK and Scottish Government Ministers have special powers to make regulations to correct deficiencies in converted EU law to ensure the statute book is ready for Brexit. This involves the laying of Statutory Instruments (SIs), also sometimes known as secondary legislation, delegated legislation or subordinate legislation (a SPICe Blog on this process is available here).

One of these SIs is the Veterinary Surgeons and Animal Welfare (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019. The draft regulations were laid on 13 December 2018 and were made on 5 March 2019. The regulations end the preferential access that veterinary surgeons with qualifications from a European Economic Area (EEA) country currently have when registering to practise in the UK.

Under the current system, EEA and Swiss nationals who hold degrees from veterinary schools recognised by the EU are entitled to have those degrees automatically recognised in any member state.

The regulations remove this mutual recognition meaning that when the UK leaves the EU, EEA and Swiss qualified persons who wish to register to practise in the UK will be treated the same as vets from outside the EU. That process is currently set out in Section 6 of the Veterinary Surgeons Act 1966, and requires that an applicant satisfy the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons that they have, “the requisite knowledge and skill” to practise in the United Kingdom.

Under the SI, the RCVS will acknowledge EEA and Swiss vets graduating from schools accredited by the European Association of Establishments for Veterinary Education (EAVE). However, graduates of non-EAVE accredited vet schools will be required to sit an RCVS statutory exam to ensure they are qualified to meet UK standards.

Although these regulations will ensure that vets coming to work in the UK are sufficiently qualified, concerns were raised about the implications for recruitment in the final debate on the motion to approve the regulations in the House of Lords on 6 February 2019.

Members highlighted that around 13% of EU vets admitted to the RCVS register were from non-accredited schools. Furthermore the high cost (£2,500) of RCVS statutory exams could potentially be a barrier to vets coming to work in the UK after Brexit.

Brexit and trade

Currently, exporters who wish to export live animals and animal products outside the EU have to apply for, and be issued with, an Export Health Certificate (EHC). EHCs are official documents that have to be signed by a veterinarian or authorised signatory. They are specific to the commodity being exported and the destination country. The EHC proves the consignment complies with the quality and health standards of the destination country.1

Regulations in relation to animal health and food safety are an EU competence. Therefore, standards within EU Member States are aligned under EU regulations and Export Health Certificates are not required when exporting within the EU.i

In the event of a no deal Brexit, EHCs would be required for exports of all animal products and live animals from the UK to the EU. This requires an Official Veterinarian or authorised signatory to inspect each consignment before an EHC can be issued.1EHCs would need to be signed by an Official Veterinarian or authorised signatory following inspection of the consignment.

Animal products that require an EHC include the following:

Meat

Dairy (milk, whey, yoghurt, cheese, butter & ice cream)

Hides, skins, wool, feathers & lanolin

Collagen, gelatine & casings

Egg

Fish and fishery products

Laboratory

Pet food and animal feeds3

Before he retired in March 2019, Nigel Gibbens, then UK Chief Veterinary Officer, suggested that in a "worst case scenario" the volume of products requiring veterinary export health certification could increase by as much as 325%.4

A significant increase in certification will require an increase in OVs to maintain current food standards and ensure public health. The UK Government has stated its commitment to maintaining food standards. In answer to a written question in July 2017, George Eustice MP, then Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs stated:

Our high environmental and food standards will not be diminished or diluted as a result of leaving the EU or establishing free trade deals with other countries.

However, a National Audit Office Report on Defra's progress in implementing EU exit states:

...without a significant increase in the UK’s veterinary capacity, the Department will be unable to process the expected increased volume of EHCs, and consignments of food could be delayed at the border or prevented from leaving the UK.5

According to a House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts report published in November 2018, Defra is in discussion with the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons on the use of non-qualified staff to carry out parts of the export health certification process, where veterinary expertise is not required.6

It is important to note that extra administrative checks will also be required for imported animal products after Brexit. According to the BVA, avoiding a no deal Brexit would also not necessarily maintain the status quo in terms of administrative requirements for exports:

Should the UK neither become a non-EU EEA country nor enter a customs union with the EU administrative checks would apply to UK imports from and exports to the EU as currently apply to trade with non-EU countries. This is likely to be the case whether UK trade with the EU is conducted under a Free Trade Agreement or under WTO rules.7

Increasing veterinary capacity is a challenge not limited to the UK. Other EU countries are also working to ensure a sufficient workforce is available after Brexit. A recent article in Dutch News explains how the Dutch customs office is writing to 72,277 Dutch firms which do business with the UK warning them to make sure they are properly prepared for Brexit.

According to the article, the Dutch food and product safety board NVWA is training dozens of foreign vets to operate as inspectors because of the shortage of officials to inspect meat, fish and poultry imports from the UK after Brexit. In total, the service plans to take on 143 new members of staff, including 100 vets. It is now recruiting in Belgium and southern and eastern Europe because of the shortage of vets in the Netherlands.8After Brexit, the UK may therefore have to compete with other EU countries experiencing a workforce shortage.

Education and Research

Non-UK EU nationals make a significant contribution to education and research in UK veterinary schools. According to the BVA, 22% of veterinary surgeons working in academia in the UK are non-UK EU nationals. These vets work in roles directly linked to providing education and training within the undergraduate veterinary degree.1A reduction in migrant vets working in academia could therefore affect the ability to educate and train domestic vets and the quality of academic research.

The BVA also raise concern over the ability to fund the relatively high-cost of veterinary education compared to other subjects. The current cost of delivering a veterinary course is around £20,000 per student per year. Courses in Scotland are currently part-subsidised by the Scottish Funding Council. However, high fees paid by overseas students are an important source of income to support the cost of delivering veterinary courses.2

Replacing vets from elsewhere in the EU with domestic graduates is not a straightforward fix. This would require a significant increase in graduates which would take much longer than the timescale required to respond to a no deal scenario. In evidence provided to the Scottish Affairs Committee, the BVA give the example of the University of Surrey School of Veterinary Medicine which was announced in October 2012 but will only deliver its first graduates this year.

Another issue with increasing workforce capacity is the career preferences of domestic graduates. The BVA further note that UK graduates rarely choose to pursue government service work alone as a career and veterinary schools in other EU countries place a greater emphasis on public health critical work through the veterinary degree. 34 A Vet Futures survey of vet students published in July 2015 found that only 6% of students wanted to pursue a career in government related work.5 Continued access to EU migrant vets is therefore critical in ensuring food safety and public health after Brexit.

Limits on Scottish veterinary student numbers

Places to study veterinary medicine are limited in Scotland as this is one of the small number of subjects taught at university that numbers of entrants are strictly controlled by the Scottish Government. Places are controlled for two reasons. The first is that the programme involves extra-mural studies (EMS) - a form of placement involving extensive practical elements, so there need to be opportunities to access practical training with Scotland based employers who can support the practical component of the programme. The BVA has said "a large and rapid expansion in student numbers may see EMS placements become a pinch point, as capacity within veterinary practice is limited."1

The second is that there needs to be sufficient potential employment in the chosen profession at the time of graduation, in line with the number of graduates at any given time. The Scottish Government pursues workforce planning measures to calculate the number of entrants to controlled subjects each year. The number set includes all entrants, including those from Scotland, the rest of the UK, Europe and the rest of the world.

In theory, in the event of a no deal Brexit, there could be a reduction in the number of EU nationals applying to study veterinary medicine at a UK/Scottish university either as a result of reducing numbers of applicants or if universities were to start charging EU nationals the same fee that is applied to students from the rest of the world (outside the UK / EU). Places currently taken by EU nationals may well be filled by people from other geographical areas (including Scotland and the rest of the UK), although it has been noted that there has been a reduction in the number of UK nationals applying to study veterinary science.2 There is also awareness of the wider implications for continuing the positive diversity of the student and graduate body at Scottish universities if fewer people from other countries were to come to the UK / Scotland to pursue their studies.

Animal health and welfare

The work of vets is integral to ensuring animals are cared for and slaughtered humanely according to animal welfare legislation. The work of OVs in public health roles is also crucial in protecting the public from the transmission of animal disease through meat consumption.

Abattoirs

An area of considerable concern within the veterinary profession is the reliance on EU nationals working as OVs in abattoirs. Food Standards Scotland have informed SPICe that there are 32 vets currently employed in abattoirs in Scotland, plus a management team of 10 qualified vets and seven locums working in the north of Scotland. Of these, around three-quarters (36) are non-UK EU nationals. Other sources suggest that at UK-level, as much as 95% of vets working in the meat hygiene sector graduated overseas with a clear majority coming from EU countries.1

The role of Official Veterinarians in abattoirs

Regulation (EC) 854/2004 sets out a requirement for all abattoirs to have an Official Veterinarian (OV). In the UK, OVs are appointed to conduct work on behalf of the Food Standards Agency (FSA), Food Standards Scotland (FSS) and the Animal & Plant Health Agency (APHA). Responsibilities include:

Ante- and post-mortem inspections of animals and carcasses.

Animal welfare – conducting clinical examinations and ensuring that animals are slaughtered humanely.

Animal and public health – undertaking surveillance to detect signs of disease that may affect human and/or animal health.

Auditing good hygiene practices

The BVA outlines the following risks:

Losing OVs from slaughterhouses would increase the risk of food fraud, provide the potential for animal welfare breaches, and remove a level of public health reassurance to consumers at home and overseas that could jeopardise trade.2

If abattoirs are unable to operate at current volumes, there are fears that this could have a knock-on effect on farms. If livestock is unable to move to an abattoir, this can lead to overstocking occurring on farms, resulting in detrimental effects on animal welfare and health. 1

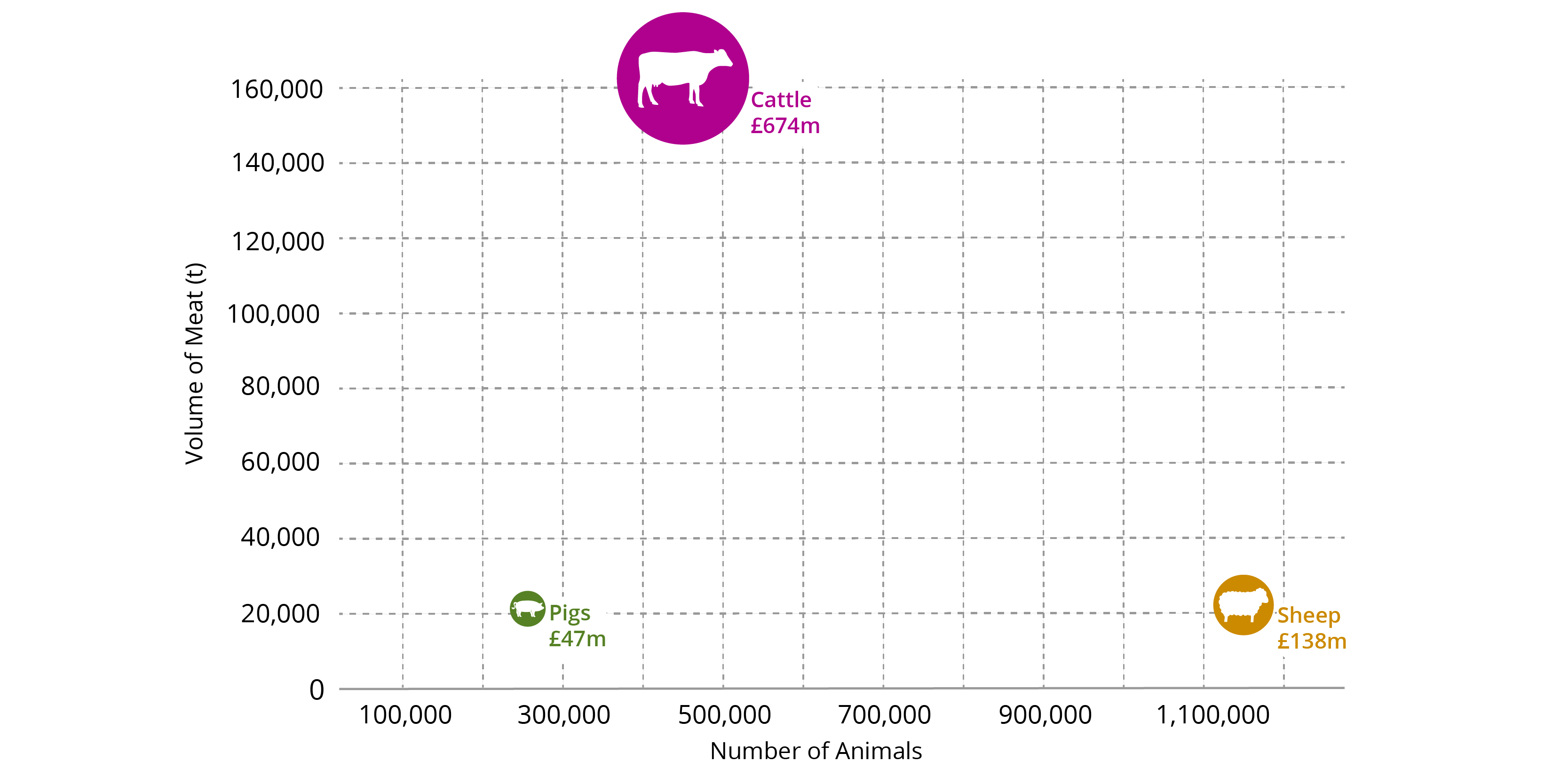

According to the latest available statistics published by Quality Meat Scotland, there were 24 licensed red meat abattoirs operating in Scotland in 2017. The chart below shows Scottish abattoir output in 2017. A total of 1.86 million animals were processed by Scottish abattoirs in 2017. This produced 212,100 tonnes of red meat worth £892 million. Employment in Scottish abattoirs was 2,900 with an estimated 51% of employees being non-UK EU nationals. This is closer to two-thirds in some of the largest processors.4

Aquaculture

Farmed salmon is one of Scotland's most valuable exports. In 2017 £318 million of Scottish farmed salmon was exported to non EU countries and £283 million exported to EU countries - a total of £601 million.1However, as with terrestrial farmed animals, fish may be susceptible to disease and infestations. Disease control is crucial to the profitable production of any farmed species.2Ellis et al (2016) state:

Effective disease management – via reduced stress in stocks, vaccination, fallowing, area management agreements, biosecurity etc. – is recognised to have been vital to the success of Scottish salmon farming.3

Fish vets play an important role in the licensing and administration of medicines, consultation and implementation of biosecurity measures and conducting inspections to ensure animal health and welfare.

Sea lice remains one of the most important health issues for the Scottish salmon industry. Marine Scotland Science The Fish Health Inspectorate (MSS-FHI) in Scotland aims to prevent the introduction and spread of fish diseases in Scotland. They carry out inspections of fish farms and provide advice and ensure compliance with regulations.

Fish health inspectors are appointed by the Scottish Ministers to act as inspectors and veterinary inspectors under the fish health legislation. This legislation includes:

Public Health

Another key role of vets is ensuring the implementation of biosecurity measures to protect the public from animal borne diseases. Vets work closely with farmers to maintain high standards.1

The World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) has emphasised the importance of the role of veterinary surgeons in abattoirs:

[The] OIE has identified animal production food safety as one of its high priority initiatives. The Veterinary Services of our Member Countries are central to this mission. They have an essential role to play in the prevention and control of food-borne zoonosis (diseases transmitted from animals to humans).2

The loss of vets, particularly in abattoirs, could have potentially severe consequences if it compromises the effective implementation of biosecurity measures. The most damaging example of this was the economic and social impact of the Foot and Mouth disease outbreak in 2001. The first case of this outbreak was detected in an abattoir. The outbreak is estimated to have cost £5 billion to the private sector and £3billion to the public sector and damaged the lives of farmers and rural communities.1