Housing conditions and standards

This briefing provides information on current housing conditions in Scotland, including a brief overview of results from the Scottish Housing Condition Survey. It also provides information on the different house condition standards that exist across the three main tenures in Scotland: owner-occupied, private rented and social rented.

Executive Summary

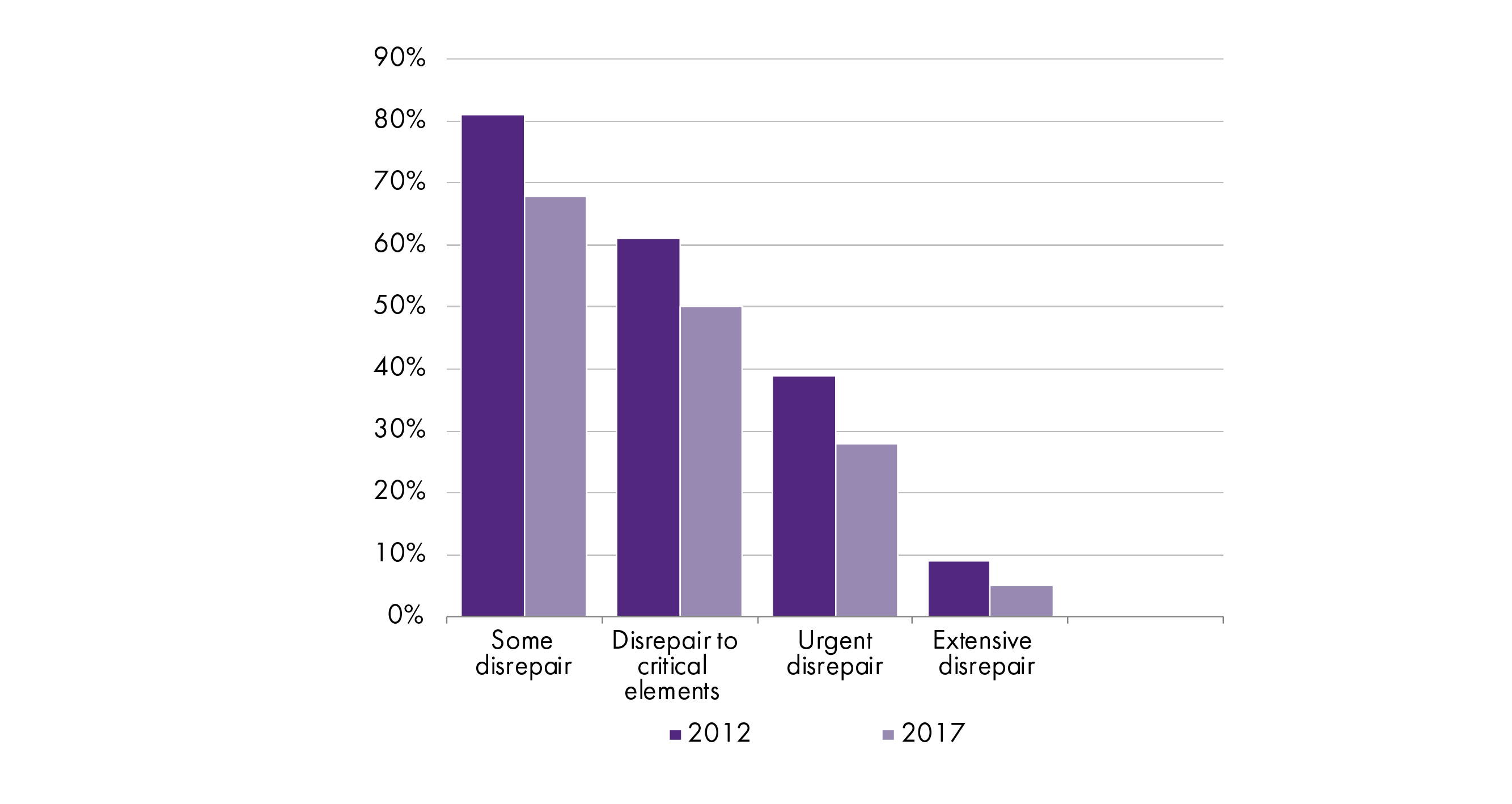

The Scottish House Condition Survey shows that the condition of housing in Scotland has improved since 2012. Despite these improvements, the survey reveals that 68% of dwellings in Scotland still have some level of disrepair. Around half of dwellings have some disrepair to critical elements, such as the roof. Just over a quarter of dwellings have a level of disrepair that requires urgent attention. Older properties tend to be in poorer condition.

Housing Standards

All new buildings, and substantially refurbished ones, must meet the relevant building standards regulations in force at the time the building warrant was approved.

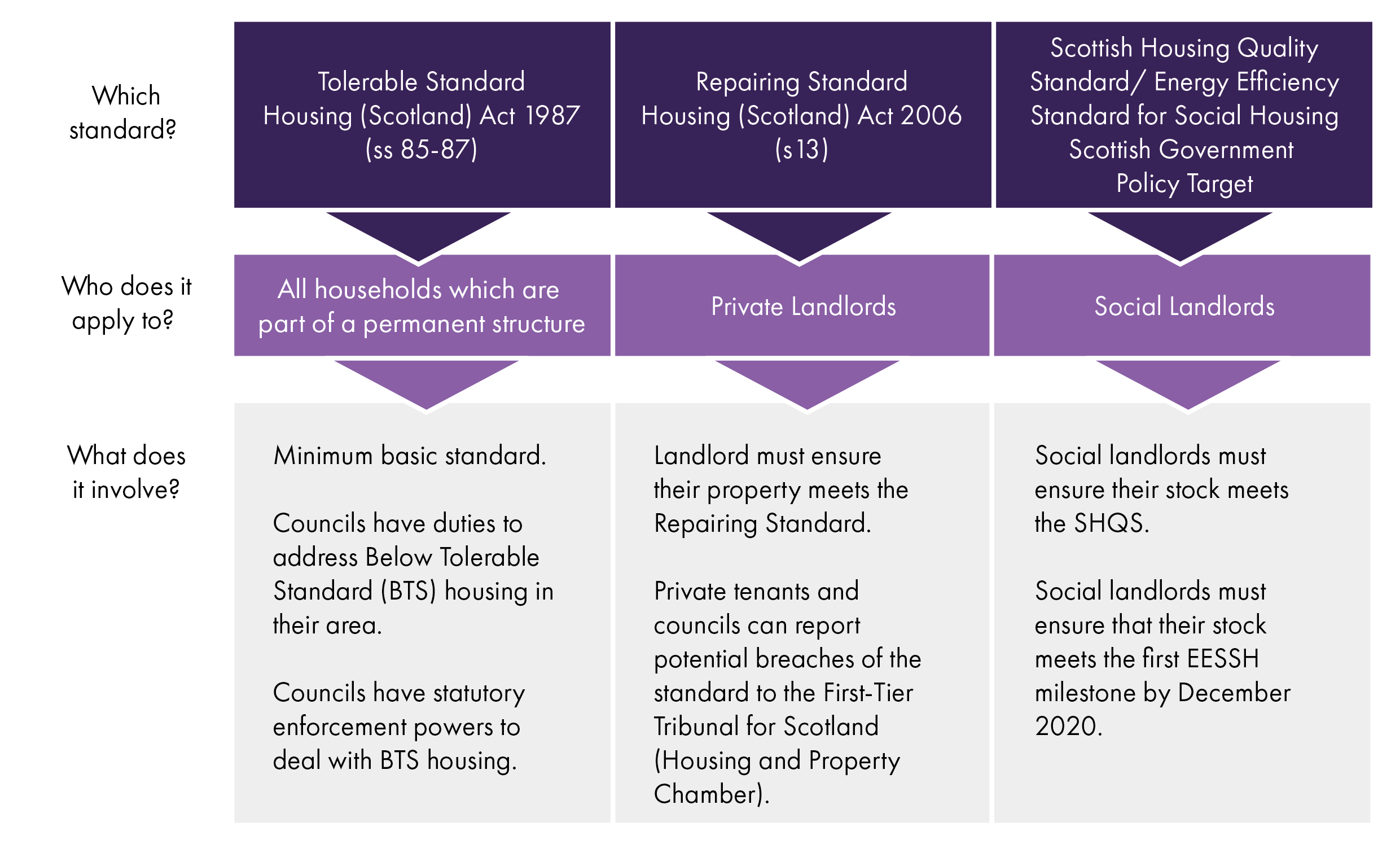

The Tolerable Standard is a basic house condition standard that applies to all tenures. In addition, there are other standards that apply to social rented and private rented housing. These differing standards may influence the condition of housing in different tenures.

The social rented sector is the most regulated tenure and has the highest condition standards. In contrast, owner-occupiers are not subject to any house condition requirements, unless they are directed to improve the condition of their homes by a local authority or under a common obligation in a tenement.

Recent legislative changes seek to bring the standards for social and private rented housing closer together, and introduce a common fire and carbon monoxide safety standard across all tenures.

Energy Efficiency

Improving the energy efficiency of homes is a current priority of the Scottish Government. This has been backed up with substantial investment in energy efficiency programmes. A long term target is that all homes should be Energy Performance Certificate -Efficiency Rating Band C by 2040. How this will be implemented will vary between tenures.

The condition of flats

Keeping flats, and their common parts, in good condition can be problematic, particularly where the blocks are in mixed tenure ownership.

A parliamentary Working Group on Maintenance of Tenement Scheme Property has recently published a report containing interim recommendations with the purpose of establishing solutions to aid, assist and compel owners of tenement properties to maintain their buildings. The Scottish Government will consider the final recommendations of the Working Group.

Local authorities have various discretionary powers to help improve house conditions in their areas. The Housing (Scotland) Act 2006 reformed the system for dealing with disrepair in private housing. One of the main policy aims behind the reforms was to inspire a cultural change and encourage homeowners to take greater responsibility for the upkeep of their properties. In this respect, there was a move away from the local authority grant approach. However, the extent to which this cultural change has taken root is not clear.

Some organisations have suggested that the Scottish Government needs to give greater priority to the issue of private sector property disrepair, particularly in tenement flats.

Introduction

There are a number reasons why good house condition is important. These include, for example:1

the costs of repair can increase if problems are left untreated;

some kinds of disrepair can make it harder to meet targets for fuel poverty and climate change because they prevent or reduce the value of energy efficiency improvements;

some kinds of disrepair may affect the health and safety of occupiers

Furthermore, in more extreme cases, properties in poor condition can pose a risk to anyone in the vicinity of the property, for example, from falling masonry.

Scottish Government policies aimed at improving housing quality have largely focused on individual tenures i.e. social rented housing (registered social landlords and council housing, private rented housing and owner occupied housing). Recent Scottish Government policy has focused on improving the energy efficiency of homes. This was made a National Infrastructure Priority in June 2015. The Energy Efficiency Scotland programme sets a long term target that:

By 2040, all Scottish homes achieve an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) C where technically feasible and cost-effective.

This standard will be implemented differently in different tenures (this is explained later in this briefing).

Flats

Around 37% of occupied dwellings in Scotland are flats.2 Owners of flats need to co-operate to keep their blocks, and their common parts, in a good state of repair. A programme of property law reform, including the Tenement (Scotland) Act 2004, aimed to facilitate the upkeep of such properties.

Despite legislative reforms, the repair and maintenance of flats remains challenging. There are particular challenges in mixed tenure blocks whose numbers have increased with the right to buy and the growth of the private rented sector. Some of the challenges include:3 456

A reluctance by owners, including private landlords, to take a long term view and invest in their properties;

Affordability issues – some owners are unable to pay for repairs;

Outdated title deeds which create barriers to repair;

Lack of long term maintenance plans or adequate building insurance in place;

Reduction in local authority staff resources.

The City of Edinburgh Council has reported that over half of its own housing stock is in mixed tenure blocks in which the council is not the majority owner, and that:

Without investment in repairs to mixed tenure blocks, there is a risk that buildings will fall further into disrepair and there is also the risk of creating a two-tiered Housing and Council housing service with high quality new build homes let alongside mixed tenure blocks in need of investment

Source:The City of Edinburgh Council. (2019, January 24). Mixed Tenure Improvement Strategy. Retrieved from http://www.edinburgh.gov.uk/download/meetings/id/59692/item_72_-_mixed_tenure_improvement_strategy [accessed 21 May 2019]

The council is pursuing options to improve the situation. This includes a strategy to purchase homes in blocks where it owns the majority and sell off properties in blocks where they would find it difficult to secure a majority ownership.

Glasgow City Council is also seeking to address the state of the tenements in its area. The council has focused its strategy on pre-1919 tenements which are of greatest concern. For example, it has an acquisition strategy, part funded by the Scottish Government, that assists Registered Social Landlords to acquire flats in targeted closes so that effective property management can be put in place. Following a pilot survey of the condition of tenements in some of its areas, the council is also undertaking further research to determine and quantify the extent of the disrepair within pre-1919 tenement stock.5

A parliamentary Working Group on Maintenance of Tenement Scheme Property, was established by a group of MSPs in March 2018. Its purpose was to establish solutions to aid, assist and compel owners of tenement properties to maintain their buildings. The Group published interim recommendations for consultation and will make final recommendations to the Scottish Parliament.9 The interim recommendations include:

the establishment of compulsory owners associations;

the establishment of sinking funds i.e. making regular affordable payments to a growing fund to help deal with future major expenditure on repairs;

five yearly inspections of tenement common parts;

amendments to relevant legislation.

The Scottish Government is expected to respond to the group's final recommendations. 10

David Bookbinder of the Glasgow and West of Scotland Forum of Housing Associations has argued that,

...there needs to be a much greater sense of urgency from Ministers on this. Currently there’s little or no public signalling from anyone in government that the deteriorating state of our tenements is a problem which can’t be tolerated.

Source: Scottish Housing News. (2019, February 06). David Bookbinder: Flat broke? How private landlords are destroying our tenements. Retrieved from https://www.scottishhousingnews.com/article/david-bookbinder-flat-broke-how-private-landlords-are-destroying-our-tenements [accessed 06 February 2019]

Scottish House Condition Survey

The key source of information on the physical condition of housing in Scotland is the Scottish House Condition Survey (SHCS), part of the Scottish Government's Scottish Household Survey. 1

The SHCS is a sample survey consisting of a physical inspection of dwellings by surveyors and an interview with householders. The interview covers a range of topics, including household characteristics, tenure, dwelling satisfaction, health status and income.

The Scottish Government also provides local authority tables each containing 3 years of data. All the data from the survey is available on the Scottish Government website.

Key SHCS Findings from 2017

The following section highlights a few key findings from the SHCS.

To provide some context to these statistics, there are an estimated 2.5 million households in Scotland, of which 62% live in owner occupied housing, 22% live in social rented housing and 15% live in private rented housing.1

Figure 1 below shows that around one fifth (19%) of Scotland's dwellings are relatively old, being constructed before 1919. A quarter of dwellings were built after 1982. Around a quarter of dwellings are tenements.

| Age of dwelling | Type of Dwelling | |||||

| Detached | Semi-detached | Terraced | Tenement | Other flats | Total | |

| pre-1919 | 4% | 3% | 3% | 7% | 2% | 19% |

| 1919-1944 | 2% | 3% | 1% | 2% | 4% | 12% |

| 1945-1964 | 2% | 6% | 8% | 4% | 3% | 22% |

| 1965-1982 | 5% | 4% | 7% | 3% | 2% | 21% |

| post-1982 | 10% | 3% | 3% | 8% | 2% | 26% |

| Total | 22% | 20% | 22% | 24% | 13% | 100% |

Levels of disrepair

The SHCS measures disrepair for a wide range of building elements which are reported in four broad categories (as described below). It is common for dwellings to display elements of disrepair in more than one category.

The 2017 results do not show any statistically significant differences from 2016, although there is a longer-term trend of improvement (see Fig 2 for comparisons with 2012). In 2017:

68% of all dwellings had some degree of disrepair

50% of dwellings had some disrepair to critical elements. The critical elements are those which are central to a dwelling being wind and weather proof, structurally stable and safeguarded against further rapid deterioration. They include, for example, roof covering and structure, and external doors and windows. Not all disrepair to critical elements is necessarily considered urgent. Although some disrepair to critical elements is fairly common, it tends to be at a relatively low level in each property, affecting, on average, no more than 2.5% of the relevant area.

5% of dwellings have some extensive disrepair. Extensive disrepair is recorded where the damage covers at least a fifth or more of the building element area.

28% of dwellings have some urgent disrepair. Urgent disrepair relates to cases requiring immediate repair to prevent further damage or which pose a health and safety risk to occupants. Urgency of disrepair is only assessed for external and common elements.

Other key findings

Around 1% of stock failed to comply with the Tolerable Standard.

Around 91% of all dwellings were free from any form of condensation or damp. This represents an overall improvement from 86% in 2012.

Across the stock as a whole, Scottish Housing Quality Standard (SHQS) compliance improved on 2016 levels. In 2017, 40% of Scottish homes failed to meet the SHQS, down from 45% in 2016. Only social landlords are actually required to meet the SHQS. However, the SHCS collects the same data for all dwellings to allow comparison across all housing stock. See further details in the section Social Housing Standards - Scottish Housing Quality Standard.

Energy efficiency

42% of Scottish homes were rated as EPC band C or better and half had an energy efficiency rating of 67 or higher (SAP 2012). This is a significant increase from 39% in 2016 and continues the improving trend from 35% in 2014, the first year in which data based on SAP 2012 is available.

What is an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating?

EPCs are part of a rating scheme which includes using a SAP (Standard Assessment Procedure) to measure the energy efficiency of a building. This is calculated using information such as the size, layout, insulation and ventilation of a dwelling and will equate to an energy rating from A to G (A is very efficient and G is very inefficient).

Variations in housing conditions

The condition of housing can vary depending on the particular characteristics of the stock, such as age, tenure, location and type of property. Some of the key variations identified by the SHCS include:

Older dwellings, particularly pre-1919 dwellings, are more likely to have some disrepair based on various measures. For example, just over two thirds (68%) of pre-1919 dwellings have some disrepair to critical elements, compared to an average of 50% of dwellings. Dwellings built after 1964 are less likely to have some disrepair.

Private rented dwellings are more likely to have disrepair to critical elements, 59% compared to a Scotland average of 50%. They are also more likely to have disrepair to critical elements and urgent disrepair, 33% compared to a Scotland average of 24%. This may partly be related to the fact that private rented dwellings are more concentrated in older flats.

Housing association stock is in better condition than dwellings in other tenures, based on various measures of disrepair, and the failure rate for the Scottish Housing Quality Standard (SHQS).

Housing standards overview

All new buildings, and substantially refurbished ones, must meet the relevant building standards regulations at the time the relevant building warrant was approved.

There are several other standards which apply to properties in different tenures.

Figure 2 provides information on the main standards in place which are discussed in more detail in the remainder of the briefing.

In general, while there are some similarities between the standards, the highest requirements are placed on social landlords. Social landlords are also subject to the greatest degree of regulation compared to owners or private landlords.

Common housing standards

The Scottish Government's 2013 Sustainable Housing Strategy included a commitment to, 'develop proposals in 2013 for a working group/forum to consider developing a single condition standard for all tenures.' A Common Housing Quality Standard Forum was set up in 2015 producing a series of topic papers around housing standards which are available online.

The Forum suggested that some elements of a common standard should apply to rented homes, but not necessarily to owner occupiers. This was because, the Forum argued, owners would have more choice in matters affecting the condition of their home than those living in other tenures.

While some changes have been made such as aligning the Repairing Standard for private landlords more closely with social rented accommodation standards, and introducing a common fire and carbon monoxide safety standards in the future, there has been no proposal for an overall common housing standard. Therefore, the Tolerable Standard remains the basic minimum standard and it will be reviewed by the Scottish Government.

The Tolerable Standard

The Tolerable Standard was first introduced in 1969 and is now set out in s86(1) of the Housing (Scotland) Act 1987 (as amended). It provides a basic 'condemnatory' standard. That is, if a dwelling is below the Tolerable Standard (BTS) it is considered to be unfit for human habitation.

The Tolerable Standard applies to housing in all tenures. The 1987 Act does not place any duties on homeowners or landlords to ensure that their property meets the Tolerable Standard. However, there are duties in other legislation for social and private landlords to meet the Tolerable Standard (explained in the remainder of this briefing).

The 1987 Act (s85) places a duty on every local authority to close, demolish or bring up to standard all houses in their area which do not meet the tolerable standard. Effectively, this means that the only requirement for owner occupiers to meet the Tolerable Standard is when they are directed to do by the local authority or where they are required to carry out work by a majority decision required by title deeds or under the Tenement Management Scheme.

Relatively few dwellings in Scotland are below the Tolerable Standard. In 2017, around 1% of dwellings (24,000) were BTS. 1

The Tolerable Standard

A house meets the tolerable standard if it:

is structurally stable;

is substantially free from rising or penetrating damp;

has satisfactory provision for natural and artificial lighting, for ventilation and for heating;

has satisfactory thermal insulation;

has an adequate piped supply of wholesome water available within the house;

has a sink provided with a satisfactory supply of both hot and cold water within the house; has a water closet or waterless closet available for the exclusive use of the occupants of the house and suitably located within the house;

has a fixed bath or shower and a wash-hand basin, each provided with a satisfactory supply of both hot and cold water and suitably located within the house

has an effective system for the drainage and disposal of foul and surface water;

in the case of a house having a supply of electricity, complies with the relevant requirements in relation to the electrical installations for the purposes of that supply;

"the electrical installation" is the electrical wiring and associated components and fittings, but excludes equipment and appliances;

"the relevant requirements" are that the electrical installation is adequate and safe to use

has satisfactory facilities for the cooking of food within the house; and

has satisfactory access to all external doors and outbuildings.

The Scottish Government plans to review the Tolerable Standard.

Future Changes to the Tolerable Standard

From 1 February 2021, the Housing (Scotland) Act 1987 (Tolerable Standard) (Extension of Criteria) Order 2019) amends the Tolerable Standard to require the installation of: t

satisfactory equipment for detecting, and for giving warning of, fire or suspected fire;

satisfactory equipment for detecting, and for giving warning of, carbon monoxide present in a concentration that is hazardous to health.

Scottish Government guidance defines what 'satisfactory' equipment means by setting out the requirement for:1

one smoke alarm installed in the room most frequently used for general daytime living purposes (normally the living room/lounge);

one smoke alarm in every circulation space on each storey, such as hallways and landings;

one heat alarm installed in every kitchen;

all smoke and heat alarms to be ceiling mounted;

all smoke and heat alarms to be interlinked;

CO detectors to be fitted in all rooms where there is a fixed combustion appliance (excluding an appliance used solely for cooking) or a flue.

These changes stem from a Scottish Government consultation on Fire and smoke alarms in Scottish homes following the Grenfell tragedy.2The Scottish Government's policy intention behind the introduction of this change is to:

...have a common new minimum standard for fire and smoke detectors across all housing, regardless of whether the house is owner-occupied or rented in the social or private sector.

Scottish Government. (2018, November). POLICY NOTE THE HOUSING (SCOTLAND) ACT 1987 (TOLERABLE STANDARD) (EXTENSION OF CRITERIA) ORDER 2019 SSI 2019/8. Retrieved from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ssi/2019/8/pdfs/ssipn_20190008_en.pdf

The new standard is based on the standard currently applying to private rented property, as set out in the Repairing Standard, so private landlords should already be meeting this standard. All new build housing, where a building warrant has been issued since October 2010, is also required to meet the above fire safety standards.

The cost of meeting the new standard, estimated to be around £200 for an average home, will be met by home owners and landlords as appropriate.4

While it will be in a home owner's own interests to ensure that their home has good fire safety measures, as explained earlier, the 1987 Act does not place any duty on owners to meet the tolerable standard. The Scottish Government has provided this explanation of how compliance with the new requirements will be monitored:

How will you check that home owners comply?

Most home owners want to make their homes as safe as possible and compliance will also form part of any Home Report when you come to sell your home. Because this will be a minimum standard for safe houses, local authorities will be able to use their statutory powers to require owners to carry out work on substandard housing, although we would expect any intervention to be proportionate.

Scottish Government. (2019). Fire and smoke alarms: changes to the law. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/fire-and-smoke-alarms-in-scottish-homes/ [accessed 04 February 2019]

Private rented housing - the Repairing Standard

Most private landlords in Scotland have to ensure that the property they let meets the Repairing Standard. This is set out in section 13 of the Housing (Scotland) Act 2006.

There is some cross over with the Tolerable Standard and recent legislation has clarified that private landlords must ensure that the properties they let meet the Tolerable Standard.i

The Repairing Standard

A house meets the Repairing Standard if:

it meets the Tolerable Standard;

it is wind and watertight and reasonably fit for human habitation;

the structure and exterior of the house (including drains, gutters and external pipes) are in a reasonable state of repair;

gas and electricity supply equipment works properly;

fixtures, fittings and appliances provided by the landlord (like carpets, light fittings and household equipment) work properly;

furnishings supplied by the landlord are safe;

there are satisfactory fire and smoke detectors;

there are satisfactory carbon monoxide alarms.

(adapted from s13 of the Housing (Scotland) Act 2006)

Private landlords must also carry out electrical safety inspections at least once every five years. The electrical safety inspection has two separate elements:

an Electrical Installation Condition Report (EICR) on the safety of the electrical installations. This must be conducted by a “suitably competent” person.

a Portable Appliance Test (PAT) on portable appliances.

The Scottish Government has issued statutory guidance on electrical safety which explains these requirements. There is also guidance on satisfactory provision for detecting and warning of fires. Guidance on the provision of carbon monoxide alarms in the private rented sector is also available.

From 1 March 2019, landlords can be exempt from the duty to meet the Repairing Standard where the landlord cannot get the majority consent required to carry out work to common parts, whether under title deeds or under the Tenement Management Scheme.ii The Tenement Management Scheme, contained in the Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004, is a fallback scheme for managing and maintaining blocks of flats. It can be used when the flat owners' title deeds have gaps or defects.

Enforcing the Repairing Standard

If a tenant thinks that their property does not meet the Repairing Standard they should report the problem to their landlord and give them a 'reasonable time' to fix the problem.

If the landlord does not fix the problem the tenant can make an application to the First-tier Tribunal for Scotland (Housing and Property Chamber) (the 'Tribunal'). Since June 2016, all local authorities have also been able to make applications to the Tribunal, in the same way as the tenant.

The Tribunal has powers to enforce the Repairing Standard by issuing a Repairing Standard Enforcement Order. The Tribunal must also inform the relevant local authority of decisions relating to the issue of, and compliance with, a Repairing Standard Enforcement Order. This information can be used by the local authority when it assesses whether a landlord is a 'fit and proper' person to be on the landlord register. (Further details on the Tribunal's enforcement powers are available on the Tribunal's website. There is also a model letter that tenants can use to write to landlords.)

The Tribunal's Annual Report notes that, between 1 December 2016 and 31 March 2018, the chamber received 308 Repairing Standard applications.1 However, from the information provided in the report it is not clear what the outcome of these applications were.

A Scottish Government consultation in 2018 proposed that private landlords registering with their local authority will have to confirm that they comply with various legal duties, including that their properties meet the Repairing Standard. 2 Part of the reason for this proposed change is to raise awareness about landlord responsibilities and to identify where further support and advice may be required. The Scottish Government plans to introduce regulations in the Parliament in 2019 to implement these requirements.

Future changes to the Repairing Standard

The Scottish Government's Energy Efficiency and Condition Standards in Private Rented Housing consultation proposed further changes to the Repairing Standard to bring the it closer to the standards required for social rented housing.1

Following that consultation, the Housing (Scotland) Act 2006 (Modification of the Repairing Standard) Regulations 2019, will make a number of changes to the Repairing Standard.

These changes will only apply from 1 March 2024 to allow private landlords time to prepare their properties to meet the standard.

From March 2024, the Repairing Standard will include:

safely accessible food storage and food preparation space;

space heating must be by means of a fixed heating system;

where the house is a flat in a tenement, the tenant is able to safely access and use any common parts of the tenement, such as common closes;

common doors must be secure and fitted with a satisfactory emergency exit lock;

electrical installations must include a residual current device (a device to reduce the risk of electrocution and fire by breaking the circuit in the event of a fault).

The existing elements of the Repairing Standard relating to fire and smoke alarms and carbon monoxide alarms will also be removed from 1 Feb 2021. This is because these provisions will be, from that date, part of the Tolerable Standard, which all private landlords have to meet.

The modification regulations also consolidated and expanded the power of Scottish Ministers to issue guidance on elements of the Repairing Standard, to which landlords must have regard. This will allow guidance to be provided on the new elements of the Repairing Standard. The Scottish Government intends to consult with private landlords on the content of this guidance.

The modification regulations make provision about who the Repairing Standard applies to. The regulations:

clarify that holiday lets are not subject to the Repairing Standard

provide that tenancies on agricultural land will be required to meet the Repairing Standard, from March 2027.

Future private rented housing energy efficiency standards

The introduction of energy efficiency standards in private rented housing has been under consideration by the Scottish Government for a number of years.1

In 2017, the Scottish Government consulted on changes to private rented housing standards in Energy Efficiency and Condition Standards in Private Rented Housing.2 Following that consultation, the Energy Efficient Scotland Route Map confirmed that new energy efficiency standards will apply to privately rented homes:3

Proposed energy efficiency standards:

From 1 April 2020, any new tenancy in the private rented sector will require the property to have an EPC of at least band E. By 31 March 2022, all properties will need to have at least EPC band E.

From 1 April 2022, any new tenancy in the private rented sector will require the property to have an EPC of at least band D.

By 31 March 2025, all tenancies in the private rented sector will need to have at least EPC band D.

The Scottish Government plans to introduce regulations in the Parliament in 2019 to implement these requirements.4

Private landlords might have to undertake various improvements to their properties to meet the standard, for example, loft insulation, the installation of efficient heating systems or solid wall insulation.

The Scottish Government has also consulted on proposals for all privately rented homes to reach EPC band C by 2030, where this is technically feasible and cost effective.5 A further consultation proposes a minimum standard of band C where there is a change in tenancy from 1 April 2025. 6

Social Housing Standards - Scottish Housing Quality Standard

All social landlords have to ensure that the properties they let are wind and watertight and in all other respects reasonably fit for human habitation (Housing (Scotland) Act 2001 Sch 4 para 1).

In addition to this basic legislative requirement, social landlords have to ensure that the properties they let meet the Scottish Housing Quality Standard and the Energy Efficiency Standard for Social Housing.

Social Housing - Scottish Housing Quality Standard

The Scottish Housing Quality Standard (SHQS) was introduced by the Scottish Government in February 2004.

The SHQS is a set of broad criteria, covering specific elements, which must all be met if the property is to pass SHQS . The broad criteria specify that social housing must be:

above the statutory Tolerable Standard;

free from serious disrepair;

energy efficient;

equipped with modern facilities and services;

healthy, safe and secure.

The Scottish Government's target was for all social landlords to ensure that all their dwellings pass the SHQS by April 2015. Since then, the expectation is that all dwellings will meet the standard and this is set out in the Scottish Social Housing Charter.

The Scottish Housing Regulator monitors performance against the charter and it has powers to intervene if landlords are failing to meet the standards and outcomes in the charter.

In exceptional circumstances, exemptions or abeyances from the SHQS may be allowed.Exemptions can be made when the landlord believes it is not possible to meet an element of the standard for technical, disproportionate cost or legal reasons. An 'abeyance' can arise when work cannot be done for ‘social’ reasons relating to tenants’ or owner-occupiers’ behaviour, for example, where owner occupiers in a mixed tenure block do not wish to pay for their share of works to common parts.1

Social landlords have made substantial investment in their stock to meet the SHQS, with the Scottish Government reporting expenditure of around £4bn for this purpose. 2

Compliance with the SHQS

The Scottish Housing Regulator reports that in 2017/18, 94% of social housing met the SHQS. This is based on socials landlord's self assessment against the outcomes and objectives set out in the Scottish Social Housing Charter. 3

On the hand, the SHCS reports a lower rate of compliance with the standard, at 62% in 2017 (not allowing for abeyances and exemptions). SHCS surveyors may not always be able to identify the presence of cavity wall insulation. If it is assumed that all social dwellings have insulated cavity walls, where this is technically feasible, the overall SHQS pass rate in the social rented sector would be 75%.4

The Scottish Government suggests there are various reasons for different compliance figure, including the different methodologies for collecting information used in the two sources.5

Energy Efficiency Standard for Social Housing

The EESSH was introduced in 2014 to encourage social landlords to improve the energy efficiency of their stock (replacing the energy efficiency elements of the SHQS). It sets a minimum energy efficiency rating of SAP 2009 60-69 (this equates to EPC D or C) for landlords to achieve by 2020, depending on fuel and dwelling type.

The EESSH does not prescribe specific energy efficiency measures so social landlords are free to meet the EESSH minimum ratings as they see fit, using any available measures. Social landlords can take various measures to ensure that the properties they own meet the EESSH. For example, measures could include the installation of condensing boilers, double/secondary glazing or loft insulation top-up.

Compliance

The progress of social landlords in meeting the EESSH is monitored by the Scottish Housing Regulator. The Regulator reports that 80% of social rented homes complied with the EESH in 2017/18.1

Review of EESS and future changes

A review of the EESSH considered progress against the 2020 target and the setting of future milestones. In the consultation, Energy Efficiency Standard for Social Housing post-2020 (EESSH2), the Scottish Government set out its proposals to:2

maximise the number of social rented homes achieving EPC band B by 2032, with a review in 2025 to assess progress and consider the introduction of air quality and environmental impact elements to the 2032 milestone

a minimum standard that no social housing should fall below EPC band D from 2025.

Respondents to the consultation generally supported the principle of maximising the proportion of social housing meeting EPC band B by 2032. However, these were qualified by some concerns, particularly from social landlords. The challenges identified included:3

the difficulty and cost associated with making improvements to some houses;

value for money of investment and cost effectiveness of some improvements;

cost implications and a landlord’s ability to access funding streams;

gaining tenant support for improvements and potential impact on rent levels;

concerns around the recognition of new technologies within the new milestone.

The EESSH Review Group has reconvened to consider the consultation analysis and the development of EESSH2, with confirmation of a new standard expected in 2019.

Owner occupied housing

In the private sector, policies on house conditions have been informed by the work of the Housing Improvement Task Force (HITF), established by the then Scottish Executive in December 2000. The Task Force's final report, published in 2003, emphasised the responsibility of owners to maintain their own properties:

Our starting point has been the belief that the responsibility for the upkeep of houses in the private sector lies first and foremost with their owners and that there is a need for greater awareness and acceptance by owners of this responsibility.

Scottish Government. (2013, March 13). STEWARDSHIP AND RESPONSIBILITY: A Policy Framework for Private Housing in Scotland The Final Report and Recommendations of the Housing Improvement Task Force. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.scot/Publications/2003/03/16686/19494 [accessed 04 February 2019]

Recommendations in the Task Force's reports led to legislative change, including changes to local authority powers to deal with disrepair in private housing, and the requirement for sellers to prepare a Home Report (including a condition survey) when they market their property for sale.

A report prepared by Professor Douglas Robertson for the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors and the Built Environment Forum Scotland, provides further background on the Task Force reports and details of the changes that stemmed from their work. The author also argues that despite the activity in this area:

...there still remains no strategic engagement with the challenge of safeguarding the condition of privately-owned property.

Robertson, D. (2019, January). COMMON REPAIR PROVISIONS FOR MULTI-OWNED PROPERTY: A CAUSE FOR CONCERN. THE PROVISIONAL REPORT TO THE ROYAL INSTITUTION OF CHARTERED SURVEYORS AND BUILT ENVIRONMENT FORUM SCOTLAND. Retrieved from https://www.befs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Common-Repair-Provisions-for-Multi-Owned-Property-in-Scotland-2019.pdf [accessed 31 January 2019]

Despite the Task Force's emphasis on owners taking responsibility for the upkeep of their properties, it is unclear the extent to which this culture change has taken place. In a 2012 consultation paper, the Scottish Government identified the need to encourage owners to give greater priority for structural work over refurbishments and to promote routine maintenance as the most effective way to reduce disrepair. 3

As stated earlier, the Tolerable Standard is currently the only condition standard that applies to owner occupied housing, although, in future, owner-occupiers will have to reach minimum energy efficiency standards. A key question is the extent to which the government should direct owners regarding the condition of their homes, rather than encourage and incentivise owners to maintain their homes.

Energy efficiency standards for owner occupiers

The Scottish Government's intention is that all homes will have to reach EPC band C by 2040 (where technically feasible and cost effective). Only around one-third of owner occupied dwellings are already EPC band C or above.

To make sure owners reach this standard, the Scottish Government plans initially to encourage them to improve their properties and to make use of grants and loans under the energy efficiency schemes. In the longer term, from 2030, the Government will consider introducing requirements on owners to meet the standard.4

Some organisations, such as the Existing Homes Alliance, have called for an accelerated target.5 On 26 March 2019, the Scottish Government issued a consultation paper, "to gather evidence which could support a change to the proposed time frame to deliver standards for all properties across Scotland in an achievable and realistic way." 6

Local authority powers to address poor house conditions

Local authorities have a number of powers to address poor house conditions in their area, although most of these powers are discretionary. In practice, local authorities try to influence owners to improve the condition of their property before using their statutory powers as a last resort.

In some cases, the powers allow local authorities to carry out the necessary work and recharge this to the owner. However, this entails upfront costs and resources for the local authority.

Statistics suggest that the use of discretionary powers in housing legislation, for example, maintenance orders, are rarely used.1 It appears that in most areas these powers are only being used reactively or to target only the most serious cases.2

Table 1 below summarises the main powers available to local authorities to deal with poor condition in their areas.

| Name of power(associated statutory provision) | Description |

| Housing Renewal Area (HRA)(Part 1, Chp 1 Housing (Scotland) Act 2006 | Powers to deal with poor quality housing issues on an area basis. If it decides that it wants to designate an HRA, the council must draw up a plan to improve the condition and quality of housing in the area. |

| Demolition Notice (Part 1, Chp 1 Housing (Scotland) Act 2006 | Demolition notices can be used to implement an HRA action plan where a house in serious disrepair ought to be demolished. |

| Work notice(Housing (Scotland) Act 2006, sections 30 and 68) | Requires an owner to bring house which is sub-standard into a reasonable state of repair. A house is substandard if it is below the Tolerable Standard; in a state of serious disrepair; or in need of repair and likely to deteriorate rapidly or damage other premises if nothing is done to repair it. A work notice can also be served where work is needed to improve the safety and security of any house. |

| Demolition order and closing orders (for below Tolerable Standard housing)(Housing (Scotland) Act 1987 ) | Councils can serve a demolition order or closing order (meaning occupation is not allowed) if a home not meeting the standard is not brought up to this standard within a reasonable time frame. See also under ‘Work notice.' |

| Repairing Standard Enforcement Order (RSEO)(Housing (Scotland) Act 2006, Part 1, chapter 4) | A tenant, or a council, can apply to the First-tier Tribunal for a decision on whether or not the property fails the Repairing Standard. The Tribunal can issue a RSEO if the landlord has failed to meet the required standard. Under Section 36 of the 2006 Act a local authority can carry out the work required by a RSEO. |

| Missing ShareTenements (Scotland) Act 2004 (section 4A).(Housing (Scotland) Act 2006, section 50)(Registered Social Landlords (Repayment Charges) (Scotland) Regulations 2018; made under the Housing (Scotland) Act 2006, Section 174A ) | Councils can pay an owner's share of scheme costs where the owner is unable or unwilling to do so, or cannot be identified or found. Broadly speaking, the section 4A power can be used where there has been an owner decision under the Tenement Management Scheme or title deeds but does not require a maintenance account to have been set up by the owners. On the other hand, the 2006 powers does require a maintenance account to have been set up. The regulations made under s174 of the 2006 Act allows registered social landlords to recover a missing share by means of a repayment charge. |

| Maintenance order(Housing (Scotland) Act 2006, section 42) | A council may issue a maintenance order to require the owner of a house to prepare a maintenance plan. The purpose of the order is to get the house to a reasonable standard of maintenance over a period of not more than five years. As the order can apply to commonly owned facilities or areas, this type of order was particularly aimed at buildings containing flats. |

| Power to obtain information(Housing (Scotland) Act 2006, section 186) | The council may use this to get the information they need in order to serve other notices. The type of information likely to be required is information about property ownership and mortgages held by an owner. |

| Defective building notice(Building (Scotland) Act 2003, section 28) | Requires an owner to rectify defects to bring the building into a reasonable state of repair, having regard to its age, type and location. It could be used, for example, in a case where a leaking roof risked damaging the structure of a building, to require the owner to make it resistant to moisture. |

| Dangerous building notice(Building (Scotland) Act 2003, section 29) | If a council considers a building to be dangerous to its occupants or to the public, it must take action to prevent access to the building and to protect the public. Where urgent action is necessary it can carry out the necessary work, including demolition (and recover the costs from the owner). Otherwise it must serve a dangerous building notice ordering the owner to carry out work which the council considers necessary to remove the danger (again, this work can include demolition). |

| Abatement notice(Environmental Protection Act 1990, sections 79 and 80) | Where a council believes a statutory nuisance exists (includes premises in such a state as to be prejudicial to health or nuisance, or is likely to occur or recur, the council shall serve a notice requiring the nuisance to be dealt with or prohibiting or restricting its occurrence or recurrence. This notice can specify work (and other steps) which are necessary to achieve this. |

| Enhanced enforcement area (EEA)Secondary legislation made under the Housing (Scotland) Act 2014 | A council can apply to Scottish Ministers for an area to be classified an EEA. The council then has extra powers to tackle housing problems such as poor quality private rented housing. An EEA is designed for exceptional circumstances. Govanhill in Glasgow has Scotland’s two EEAs desginated to date. |

| Planning authority power(Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997, section 179) | A council in its capacity as planning authority can serve a notice requiring an owner of land to carry out work on it, where the condition of the land is affecting the amenity of the area. In can be used, for example, for badly neglected gardens. |

| Cleaning and prohibition on litter(Civic Government (Scotland) Act 1982, section 92) | An occupier of a tenement has a responsibility to keep the common property of a building containing flats (e.g. the common stair) clean to the satisfaction of the council. The council can serve a notice relating to this duty and also has rights of access (on giving reasonable notice) associated with it.Councils can also make associated bylaws, breach of which is an offence punishable by fine.Littering of the common property is also an offence punishable by fine. |

| City of Edinburgh Council(City of Edinburgh District Council Order Confirmation Act 1991) | The City of Edinburgh Council has local powers to serve notices requiring owners to carry out repairs. If the owner does not carry out the required repairs the council can carry out the repairs and recover the costs of doing so.The council run repairs service associated with this aspect of the legislation was suspended in 2011 when allegations emerged relating to the service. It was replaced with the Edinburgh Shared Repairs Service, which was phased in 2016 and 2017. |

| Landlord Registration(Antisocial Behaviour etc (Scotland) Act 2004, Part 8) | Most private landlords are required to be registered with the local authority where they let their property. Under Part 8 of the 2004 Act, local authorities can refuse/revoke registration if the landlord is in breach of requirements. Any evidence relating to breach of housing law (for example, failure to comply with the Repairing Standard) may be taken into account when deciding if the landlord is fit and proper to let houses. It is a criminal offence to operate as an unregistered landlord. |

| Houses in Multiple Occupation (HMO) (Housing (Scotland) Act 2006, Part 5) | One of the key aims of HMO licensing is to ensure that the accommodation provided is safe, of good quality and is well managed.Under Part 5 of the 2006 Act, local authorities have the powers to refuse/revoke an HMO license and landlord registration, if the landlord is in breach of the requirements. Furthermore, a local authority has the power to impose such license conditions as they think fit, which may, for example, require certain standards to be maintained throughout the period of the license. |

Sources of support for improving housing conditions in private housing

Although owners are responsible for maintaining their own homes, some owners can find it difficult to arrange, or pay for, repairs and improvements.

Local authority Scheme of Assistance

The Housing (Scotland) Act 2006 (part 2) requires local authorities to set out a Scheme of Assistance detailing the support that will be offered in its area. Local authorities can provide assistance to owners for house repairs, improvements, adaptations and construction, as well as the acquisition or sale of a house.

The assistance can take various forms, including loans, practical assistance and grants. Local authorities decide what kinds of assistance to make available on the basis of local priorities and budgets. However, in line with the emphasis on owners taking responsibility for the upkeep of their property, Scottish Government guidance discourages the use of open ended grant programmes.1

If a local authority serves an owner with a work notice (where a property is in disrepair), it must provide assistance. Grant assistance must be provided for most work to adapt homes to meet the needs of disabled people (where this is deemed essential). All other assistance is discretionary.

In 2017-18, councils provided householders with 214,286 instances of help under their schemes of assistance. Most of this help (205,237 cases or 96% of all cases) was in the form of non-financial assistance such as website hits, leaflets or advice.

Total scheme of assistance spending was just under £39m. Most of this, £22.4m, was spent on disabled adaptations, while around £17m was for other work (including around £7m for local authority administrative costs). 2

Other sources of information and support

Under One Roof website

The Under One Roof website (which provides impartial advice on repairs and maintenance for flat owners in Scotland) has advice on paying for repairs at this link.

Care and Repair service, available in most local authority areas, offers advice and assistance to enable people to repair, improve or adapt their homes. The service is available to owner-occupiers, private tenants and crofters who are aged over 60 or who have a disability.

Pilot Equity Loan : The Scottish Government is funding a Home Energy Efficiency Programmes for Scotland (HEEPS) Equity Loan designed to help homeowners and private landlords make energy improvements and repairs to their properties. It is available to homeowners or private landlords, that meet certain criteria, in Perth and Kinorss, Stirling, Dundee, Glasgow City, Inverclyde, Renfrewshire, Argyll and Bute or the Western Isles. Further details are on the Energy Saving Trust website.