Overview of private rented housing reforms in Scotland

This briefing paper provides an overview of recent reforms to the private rented sector (PRS) in Scotland within the wider context of UK reforms.

Executive Summary

This briefing is the result of a project with the Urban Big Data Centre (UBDC) at the University of Glasgow and the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE) as part of SPICe’s academic engagement programme. It complements another briefing prepared as a part of the same project, Private renting reforms: how to evidence the impact of legislation.

This briefing paper provides an overview of recent reforms to the private rented sector (PRS) in Scotland.

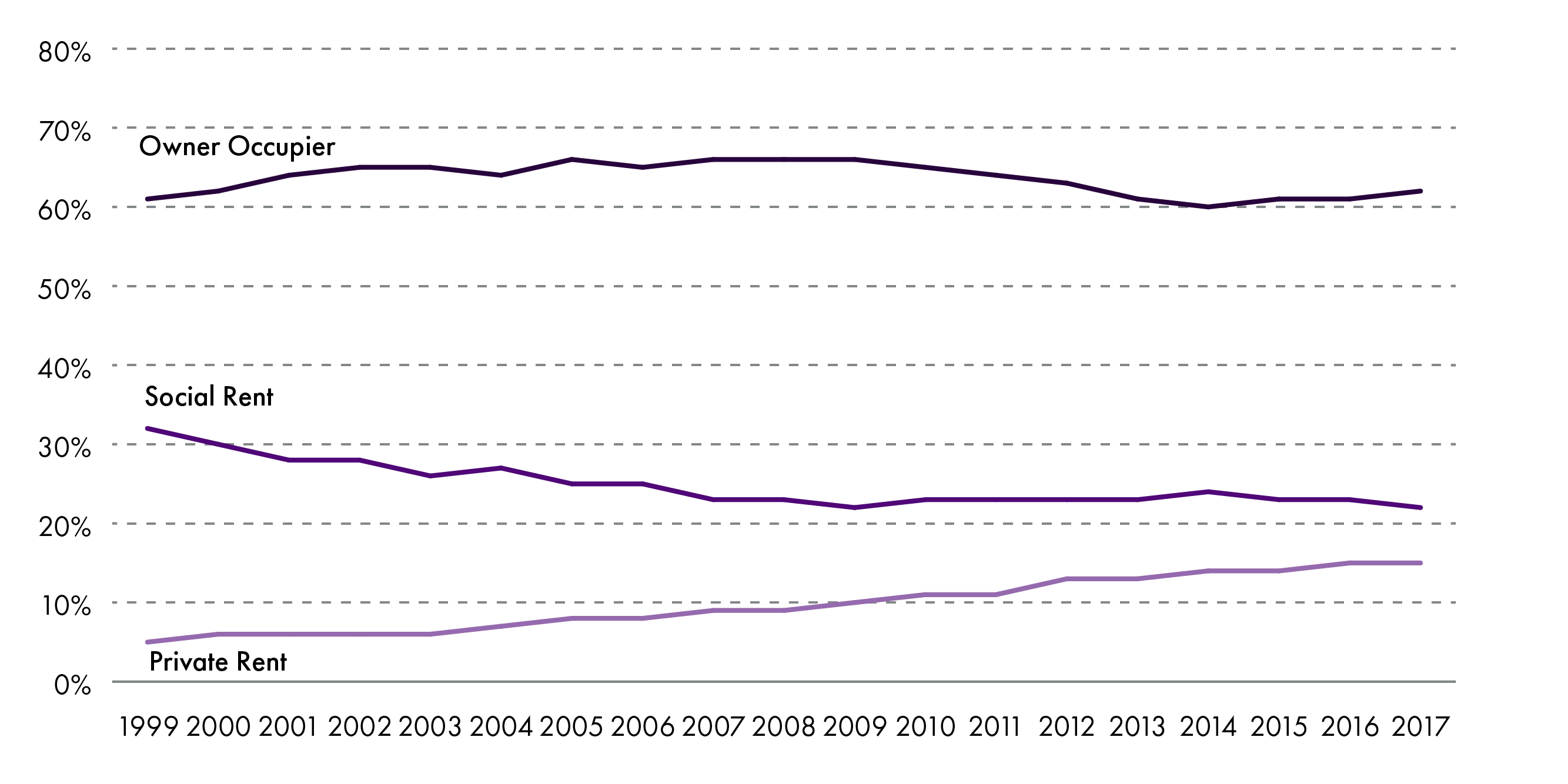

The PRS has grown

The recent growth in the PRS against a backdrop of long term decline is a critical characteristic of contemporary British housing. In 1999, 5% of Scottish households lived in the PRS. By 2017, this proportion had grown to 15%. Around 360,000 households in Scotland now live in the PRS, treble the number in 1999.

Why has the PRS grown?

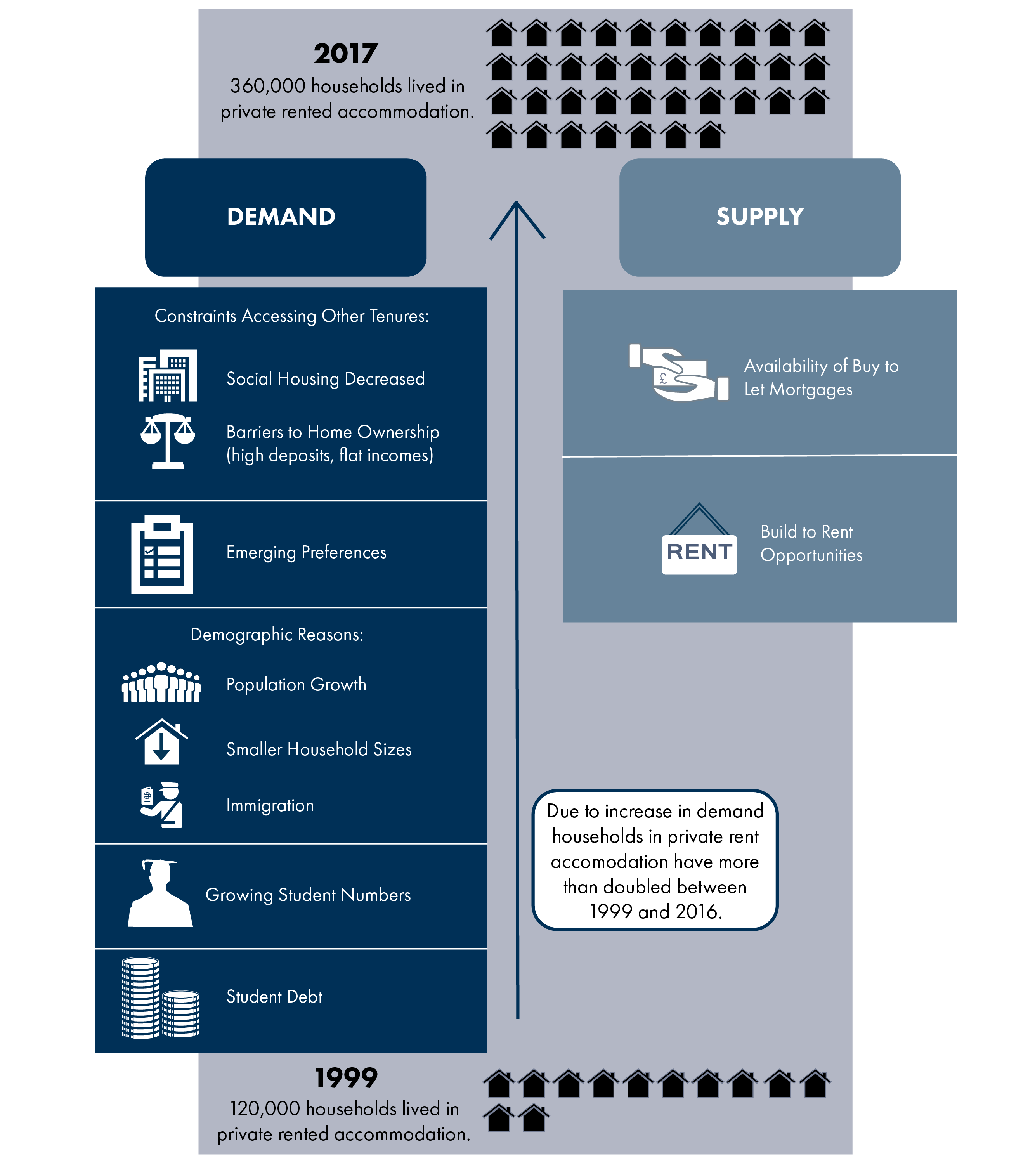

Research evidence points to a variety of reasons for this growth. There has been increased demand from people to live in the PRS, reflecting a mixture of constraints and preferences. Constraints include the difficulties that people can face in accessing other tenures. Other factors, including demographic changes like increasing population, reducing household size and in-migration, have also contributed to the growth of the PRS.

In terms of the supply of private rented housing, the growth of buy-to-let mortgages has been a particularly important driver of growth.

The private rented sector is complex and interdependent

The 'PRS' is an umbrella term. In reality, the PRS is composed of a number of different sub-markets. Demand to live in the PRS comes from different groups of people. For example, young professionals, students, and those seeking short-term lets.

On the supply side, there are different types of suppliers of private rented accommodation. These include general buy-to-let investors, institutional investors, and social housing subsidiaries providing 'mid-market' rented housing.

The PRS is highly connected to other housing tenures and is particularly exposed to changes in supply and demand that impact directly on the rental market (e.g. investments in the local economy) or indirectly, for instance, through competition from new forms of affordable housing provided by housing associations.

Policy Reform

The PRS has been the locus of considerable policy change, both direct and indirect, since the turn of the Millennium. These reforms need to be seen in a wider context stretching back to the deregulation of tenancies in Housing (Scotland) Act 1988 (the Act allowed landlords to charge market rents ending a system of regulated rents). Also, the failure to attract institutional investment into the PRS and the unanticipated market-led explosion of buy-to-let.

Direct policy reform

In Scotland, various regulatory controls have been introduced on an incremental basis.

Most recently, the Private Housing (Tenancies)(Scotland) Act 2016 introduced a new open-ended private residential tenancy to supersede existing tenancy arrangements. The new tenancy includes measures to control excessive rent increases. Furthermore, it allows local authorities (with Scottish Government approval) to set up rent pressure zones in their areas where rents rises for existing tenants would be restricted.

The new tenancy has attracted considerable interest and comment. For example, questions have been raised about how easy it will be to implement a rent pressure zone. However, as yet it is too early to assess the impact of the changes.

Indirect policy reform

Developments in the Scottish PRS have also been influenced by indirect policy reforms mainly in reserved areas, such as welfare reform and tax changes affecting private landlords.

The unexpected growth in buy-to-let lending and the incremental use of regulation suggests that policy is following rather than leading the market. However, many economists and public policy analysts are sceptical about the capacity of government to lead or shape the housing market.

There is lack of consensus about what the appropriate role and scale of the PRS should be. This degree of contention sits behind many of the outstanding debates about the future of private rented housing policy.

Regulatory reforms have not been evaluated. It is essential that the new policies are measured, weighed and properly assessed. This is a difficult task considering the system-wide reasons outlined above and data limitations outlined in another briefing prepared as a part of the same project, Private renting reforms: how to evidence the impact of legislation.

The PRS in Scotland is a good example of devolved policy divergence, as the rights, rules and roles of the rental market are now substantially different across UK jurisdictions.

Introduction

The briefing is in three sections.

The first section considers the context of the PRS, describing the recent growth of the sector and changes which have occured since the mid-to-late 1990s. The section also discusses the factors that may help explain this growth. Lastly, this section highlights the complexity of the PRS and considers the PRS in relation to the wider housing system.

The second section focuses on the major policy reforms in the PRS, both direct and indirect. This section also covers some of the debate about regulatory reform and considers Scottish developments in the UK context.

The third section draws out key points and conclusions.

Context - growth and change in private renting

As we described in the companion briefing paper, the PRS has grown strongly in Scotland since 2000. The key points to take from that briefing paper include:

The Scottish PRS has grown, from 5% of households in 1999, to 15% in 2017 (see Fig 1). Growth is even higher in urban local authority areas than in more rural areas. For example, in Edinburgh around 26% of households lived in the PRS in 2017, an increase of 16percentage points since 1999.1 2

The PRS has in the past largely been dominated by young adults. This is still the case. The sector typically has very high turnover. About 35% of private rented households have lived at their current address for less than a year (although in rural areas people tend to live in private rented housing for longer).2

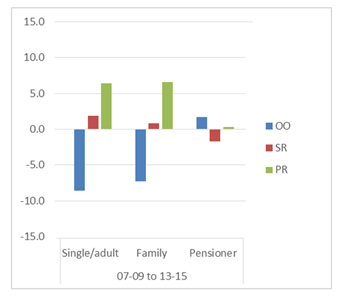

Recent changes to the tenure mix have led to more families living in the PRS, though the number of families may still be small compared to single adults living in the PRS. Young adults are known to be the most mobile and have the highest migration levels.5 Other the other hand, families generally seek more secure tenures, which are more in line with the needs of children. Stability of schools and home are seen as important for children. The rise of families in the PRS raises important questions about the capacity of the sector to meet their housing needs.

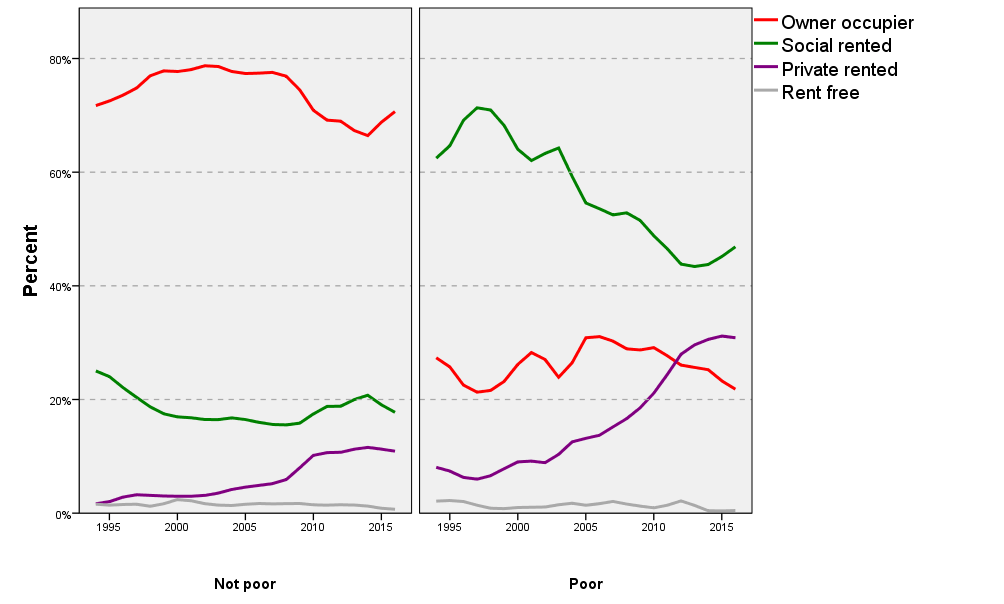

Evidence from the Family Resources Survey suggests that there has been a greater growth in the number of children in 'poor' households living in the PRS, compared to the growth of children living in 'non-poor' households. More than 30% of children living in poor households now live in the PRS (Figure 3).

The rapid changes in the PRS, the growth of families in what has traditionally been seen as an unstable form of tenure, and in particular, the increase in use of the sector by poorer families raises questions about the impact of recent change in the PRS.

Why has private renting grown?

While 15% of households in Scotland live in the PRS, in England this figure is above 20% and higher still in London (where affordability constraints are most keenly felt). The reversal of the trend of more than 75 years of absolute and relative decline as a tenure, is a defining characteristic of contemporary British housing.

The growth of the PRS over the last 20 years or so can be explained by a number of factors (summarised in Figure 4) operating together.

Demand for private renting has increased

One of the reasons for increased growth in the PRS is weakness or challenges in other parts of the housing system. For example, the available stock of social rented housing has declined in absolute terms, reducing rental opportunities other than in the PRS. Furthermore, flat earnings, housing affordability and deposit constraints have made home ownership less accessible to young would-be buyers.

A review of evidence on the PRS commissioned by the Scottish Government emphasised the importance of such demand factors. Other demand side causes which the review referred to included immigration into Scotland, the rate of new household formation and growing student numbers.1

In a study, Demand Patterns in the Private Rented Sector in Scotland, the authors argue that the growth of the PRS is in part, about demographic changes, in particular, population growth and shrinking average household size. They also note that it is a consequence of lifestyle changes and affordability issues compared to buying a home. They argue that part of the rise in demand for the PRS is undoubtedly due to student debt. They also point out that length of leases may be increasing (prior to the introduction of the new tenancy in Scotland). 2

Others argue that the growth of the sector cannot be wholly attributed to life-style choices and are more reflective of constraints, raising the need for constructive policies to drive up quality and consumer satisfaction.3

There may be an emerging preference for private renting.

Demand for living in the PRS may also reflect an emerging preference for renting as the PRS normalises and renters choose, for instance, urban amenities over suburban-commuting owning opportunities (as the growth in the PRS has been particularly concentrated in urban areas). However, this aspect is most difficult to assess in terms of its contribution to demand-side growth.

Supply of properties has been particularly facilitated by buy-to-let

Factors which have contributed to the increased supply of private rented accommodation include very low interest rates and the appetite of the financial sector to provide mortgage finance.

The buy-to-let sector has increased at the same time as commercial funding has shifted to the buy to let sector, where investors have been able to access the properties that had previously been picked up by first time buyers. Later on in the briefing we consider the factors that helped the buy-to-let sector expand so much.

Trevillion and Cookson4 make the important point that longer term institutional investment will require people to actively choose to live in the PRS (i.e.'pull' demand factors) rather than living there because they are 'pushed' from other tenures.

Will the growth in the PRS continue?

Whether recent growth in the PRS will continue is unclear. Growth may flatten and slow in the face of wider challenges to the sector. For example, it could be possible that future UK Government policies to stimulate home ownership may be successful and spill over into Scotland. UK Government policies may also go further in targeting buy-to-let landlords. The PRS is historically volatile, as well as interdependent with other housing markets, and there is no reason to think that this volatility will not continue.

Pattinson, et al believe that the PRS will continue to grow and that the precise shape and composition of this growth will depend on social, economic and political factors and the net effects of demographic change across tenures. 1

The paper by Pattison et al. also indicated that future growth is likely and that this will require reforms on the demand-side (longer tenancies to support more durable renting for families) and on the supply-side, delivering improved supply through institutional and corporate investments.1

It is in this context that the recent paper by Udagawa et al. for LSE London,3 which simulates different future growth/decline scenarios for the sector and its component parts for London and England, is of interest. Their research concluded that future growth in the PRS will be most pronounced where future economic and housing performance is weakest. However, their results indicated that PRS share is expected to fall back more generally if UK Government policies to curb immigration, build much more housing and support economic growth in London, create a more balanced and affordable market context. As we suggested earlier, this is an example of the dynamic and unpredictable nature of the sector, in part shaped how other tenures might fare in the future.

Analysing private rented housing - complexity, interdependency and housing systems

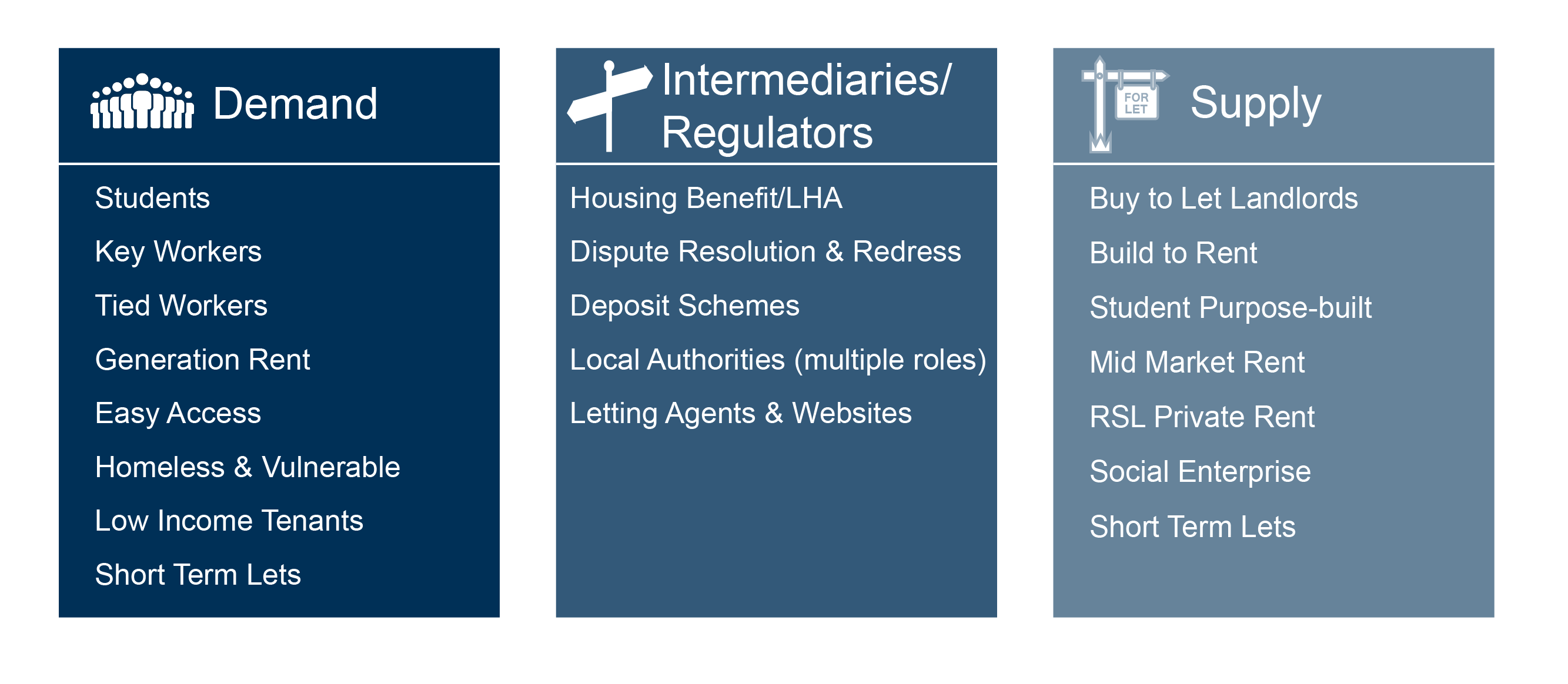

A key point to bear in mind when analysing the PRS, and the impact of government policy, is that the PRS is really an umbrella term for a series of distinct and segmented sub-markets (Figure 5).

Demand to live in the PRS comes from a number of different groups of people. For example, from young professionals, students, and those seeking short-term lets.

On the supply-side, different providers of PRS accommodation can be distinguished. These include; general buy-to-let investors, institutional investors, social housing subsidiaries providing mid-market rented housing, and purpose-built student housing providers.

The demand for, and supply of, PRS accommodation is influenced by the range of intermediaries/regulators operating in the sector. For example, local authorities have responsibility for registering private landlords. If they refuse to register a landlord, because they are not 'fit and proper' to act as a landlord, then the landlord is not legally allowed to let their property.

The PRS is interdependent with the wider housing system

The different sub-markets of the PRS described above are connected to each other. Yet the PRS as a whole is also highly interdependent with the wider housing system and its component parts.1 For example, as we covered earlier, and as evidenced by developments in the last 10-15 years, changes to the cost and availability of owning, and social renting, directly impact on the demand for private renting.

This means that policy change and economic shocks in one part of the housing system can reverberate around the housing system with 'second round' or unanticipated effects following on. Not only is a housing system interdependent but it also has 'feedback loops' e.g. rent regulations introduced to cap rents can lead landlords to increase previously lower rents towards the maximum permitted which can amplify or moderate these repercussions.

It is useful to consider PRS policy reforms within this housing systems context.

Policy Reforms

This section briefly covers policy reforms relating to the PRS.

It first provides some context to the development of recent reforms. It then considers direct policy reforms and policy instruments in Scotland, followed by a description of some of the indirect policy reforms which impact on the Scottish PRS.

Direct policy reforms - context

It is useful for any analysis of recent policy reforms in Scotland to consider the longer term context within which these reforms have taken place.

In 1989, the assured and short assured tenancy framework was introduced by the Housing (Scotland) Act 1988 ('1988 Act'), replacing the previous regulated tenancy framework. Regulated tenancies were subject to a form of rent control through a 'fair rent' system that had been in place in different forms since the mid-1960s.

With the removal of the fair rent system, the new tenancy arrangements allowed tenants and landlords to agree 'market rents.' In practice, most new tenancies following the implementation of the 1988 Act were short assured tenancies, based on a default model of fixed term tenancies of 6 months and providing less security of tenure.

Behind these reforms was the desire of the Thatcher Government to provide the conditions for landlords to have confidence to invest in the PRS. The ability to charge a market rent was envisaged to be attractive to potential investors. Furthermore, as the new tenancies were based on a default fixed-term, and could be ended relatively easily, landlords would also have certainty that they could get their property back easily if they needed to sell and access their capital.

However, tenancy reform and rent deregulation were not the only necessary condition for new investment in the sector. The UK Government recognised that it also needed to stimulate investment to foster what was effectively a new market. 123

Various measures were introduced to facilitate institutional investment. These included the business expansion scheme and real estate investment trusts. However, successive attempts failed to have the desired long-term impact.

Commentators suggested that a combination of: high management costs; lack of specific expertise and market knowledge; worries about re-regulation, and that the forms and extent of the tax breaks offered were insufficient to attract corporate investors, compared to their more familiar investment classes.45

Instead, and as described earlier, the forces that enabled the sector to grow so dramatically from the late 1990s onwards were, on the one hand, demand-side factors but primarily the advent, on the supply-side, of buy-to-let mortgages.

Buy-to-let mortgages

Buy-to-let mortgages emerged from a partnership between letting agents and mortgage lenders who saw an opportunity in a mature residential mortgage market to grow the rental market supply-side. These commercial mortgages, unlike home owner loans, still attracted loan interest tax relief.

Thus, a financial market product, rather than direct government policy, stimulated a huge number of investors to invest in the PRS. Buy-to-let mortgages were attractive to investors who were often concerned about conventional pension returns. They saw the long term potential of the income and capital growth within a package that offered liquidity and stronger protections, post-deregulation, for investors.

As is true in many other countries, UK and Scottish residential investment remains a small-scale business with the great majority of landlords operating portfolios of one to three properties (and most just one unit).

Partly because of its unplanned nature, and also because the UK Government was persuaded of the argument, in recent years there has been a willingness to slow down the growth of the buy-to-let sector through fiscal instruments. At the same time, government has continued efforts to encourage corporate scale landlordism into the sector e.g. through build to rent policies.

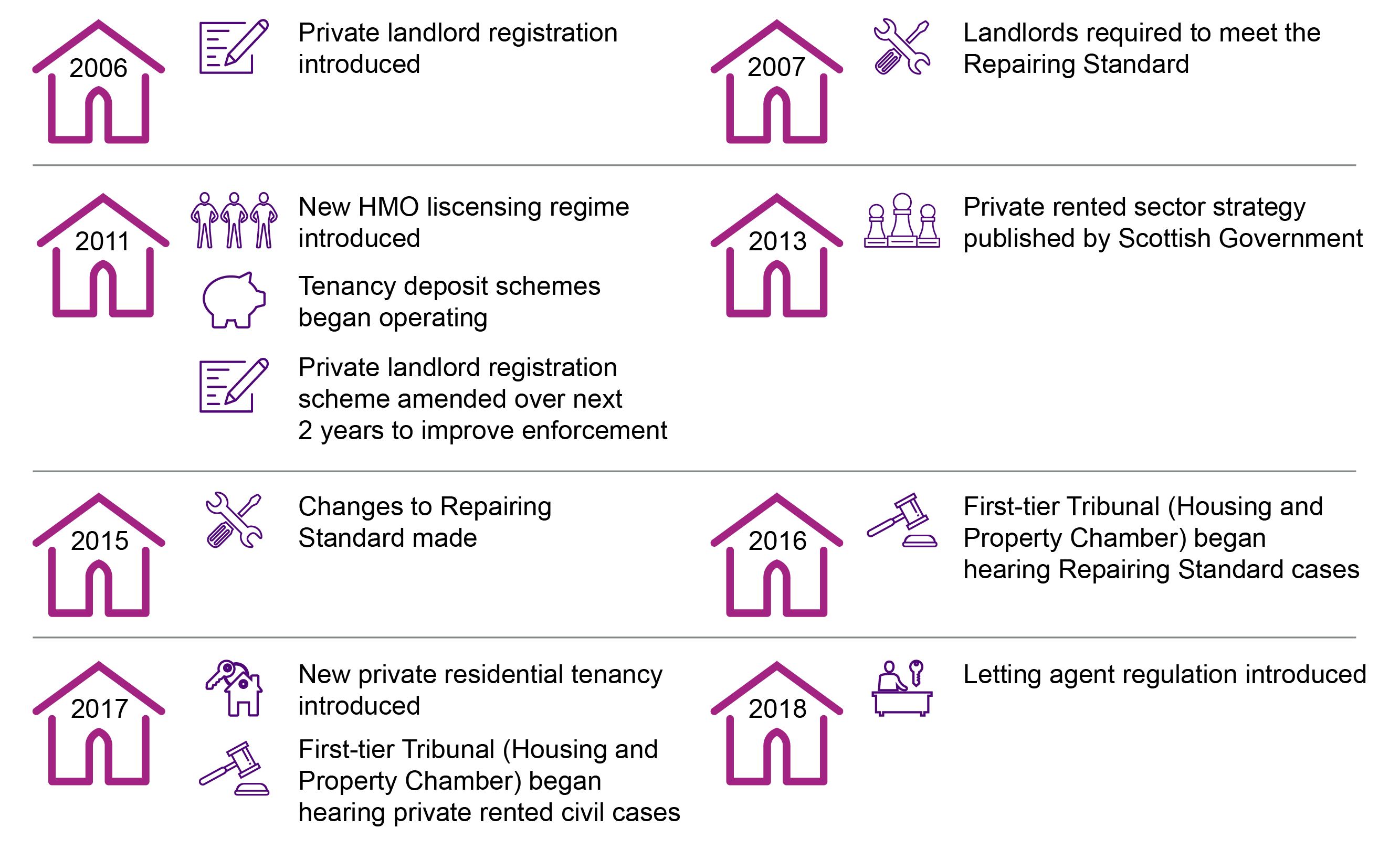

Scottish Policy Reform

A feature of the PRS post-millennium, associated with the rise in significance and visibility of the sector, has been incremental regulation (and re-regulation) of important aspects of the PRS. Scottish Government led reforms have included:

The licensing of homes in multiple occupation (HMO) largely for health and safety reasons.

The reform of dispute resolution. For instance, tenancy deposit schemes have been introduced. These provide a dispute resolution service where the return of a deposit is disputed. The First-Tier Tribunal (Housing and Property Chamber) now hears PRS civil cases, instead of the sheriff courts.

The mandatory registration of landlords, along with the regulation of letting agents and their fees.

The introduction of a new private residential tenancy.

Figure 6 provides an overview of the main policy developments. Table 1 in the Annex provides a summary of the relevant legislation.

Policy instruments - build to rent opportunities

In addition to the main policy reforms, instigated through legislative change, policy instruments have also been used to influence the direction of private renting.

The present suite of policy instruments operating in Scotland includes, but is not limited to, the buy-to-let model and measures aimed at corporate landlords operating in the purpose-built student homes market.

There are also 'build to rent' opportunities that seek to encourage builder-investor-landlords into new locations at scale. 1

Rental Income Guarantees

One variant on this model is to offer rental income guarantees (RIGS). The Scottish Futures Trust is running a pilot scheme (on behalf of the Scottish Government) offering the underwriting of up to 50% of the rental income stream for three years in qualifying build to rent developments. A similar model, promoting guarantees associated with a mid-market or affordable rental model, had also previously been supported by the Scottish Futures Trust.

RIGS seeks to provide investors with greater confidence during the early stages of a development, when letting risk is likely to be highest. Should a participating investor not achieve their anticipated level of rental income post-habitation, a Scottish Government guarantee would compensate them for part of this. The Scottish Government would share equally with the investor the shortfall within the defined tranche.

Housing association mid-market rent

At the same time, housing associations, through subsidiaries, have entered the PRS playing a straightforward commercial letting role. Housing associations have been using Scottish Government grant subsidies to fund the development of 'mid-market' rented housing.

What is mid-market rented housing?

This housing is a type of affordable housing where rents are lower than private rent market rents, but higher than social housing rents. Initial rents are generally set at around the prevailing local housing allowance (LHA) rate (the LHA rate is used to determine the maximum housing benefit payable to tenants living in the PRS). Tenants will have a PRS tenancy. From 1 Dec 2017, this has been a private residential tenancy.

The type of people to whom these properties are let are generally working tenants who have no priority for social housing, but cannot afford to buy their own home or pay full-market rents. There is also a regionally varied household income eligibility ceiling at the point of application.

The Scottish Government grant subsidy, provided through the Affordable Housing Supply Programme, is around £44k per unit.2 In recent years, mid-market rent has accounted for a growing part of the Affordable Housing Supply programme. In 2017/18 just over 1,100 mid-market rent houses were completed, accounting for around 13% of programme completions.3

Mid-market invitation scheme

More recently, the Scottish Government announced that the Placemaking and Regeneration Group 'Places for People' was successful in securing Scottish Government loan funding of £47.5m for their proposal, which will deliver 1,000 mid-market rent homes.4 This was in response to the Scottish Government's invitation for prospective providers to submit proposals for mid-market rented housing at scale under the MMR Invitation scheme. “At scale” is expected to mean that a proposal will cover more than one local authority area and involve several sites, delivering between 500-1,000 units in total).

Indirect Policy Reforms

A number of indirect policy reforms, mainly by UK Government on reserved matters, have also impacted on developments within the PRS.

Welfare reform

The UK Government's welfare reform programme has included a range of measures, particularly changes to housing benefit, that affect low income tenants living in the PRS.12

Since 2010, UK Government welfare reforms have impacted the amount of Housing Benefit that can be paid to tenants living in private rented housing. Reforms include:

The introduction of caps to the Local Housing Allowance (LHA). LHA is the maximum amount of housing benefit that can be paid to tenants living in the PRS;

LHA caps based on the 30th percentile of rents instead of the 50th percentile of rents;

The introduction of Universal Credit;

The introduction of the Benefit Cap; and

Benefit freezes - e.g. LHA rates have been frozen for 4 years from 2016 (although extra funding is available in areas where rents have risen excessively)

Such reforms affect demand for PRS generally and also impact on where low income tenants can live.

Tax changes

On the supply-side, landlords have had to confront a 'triple-whammy' of adverse tax changes. Three main tax changes have been introduced by the UK Government:

Most importantly, the amount of Income Tax relief landlords can get on residential property finance costs will be restricted to the basic rate of tax. This measure is being implemented gradually over 4 years from April 2017. This change followed considerable policy comment when it was realised that buy-to-let loan interest tax relief was worth several billions per annum. Commentators have suggested that the fiscal effects associated with change, i.e. moving individuals from one tax bracket to a higher one, may be a major disincentive for investing in the sector. However, there is no necessary reason why the properties released would flow back to the home ownership sector.

Three percent was added to every stamp duty tax band for buy-to-let purchasers (and everyone with multiple properties). A similar change was made to Land and Buildings Transactions Tax (LBBT) in Scotland. The Scottish Budget 2019 to 2020 announced that legislation will be introduced to provide that, from 25 January 2019, the LBBT additional dwelling supplement will be charged at 4% of the total purchase price of the dwelling.

Private landlords were exempted from a reduction in capital gains tax rates introduced by the 2016 UK Government budget.

The rationalisation for these reforms appears to have been driven by Bank of England concerns that buy-to-let landlords were outbidding potential first-time buyers, and so destabilising the market. In addition, there is a UK government desire to re-provision the market in favour of larger scale providers.

However, this is not necessarily consistent with a system-wide perspective on housing reform in the sense that the tax reforms assume departing buy-to-let landlords will sell into the first-time buyer market. However, they may simply sell to other landlords or shift into the unregulated short-term lets market and thereby frustrate the main policy aim.

Tenancy and Wider Policy Reform

The new private residential tenancy was introduced for new tenancies from 1 December 2017 by the Private Housing (Tenancies) (Scotland) Act 2016 ("the 2016 Act"). Behind the reforms was the Scottish Government's desire to support the growth of a professional, high quality PRS that can be considered as a desirable and sustainable housing solution.

A key feature of the new tenancy is that it is open-ended. A landlord can no longer use the 'no-fault' route to evict a tenant. A landlord can only end a tenancy specifying one of 18 eviction grounds set out in the 2016 Act. This contrasts with the short assured tenancy which can be ended at the end of a fixed term without the landlord having to give any reason.

A new feature is the introduction of measures to improve rent predictability. Landlords may only increase their rents once a year and tenants can challenge perceived excessive rent rises. In certain circumstances, including where rents are rising excessively, local authorities may also apply to the Scottish Government to have a rent pressure zone declared in their area. Within a rent pressure zone, rents increases for existing tenants would be restricted.

The new tenancy marks an important departure for Scotland, as similar reforms have not been made elsewhere in the UK, but can also be expected to cumulatively impact significantly on tenants, landlords and the sector.

Debate and comment about the new tenancy

While it is too early to evaluate the impact of the recent tenancy reform, the move has attracted considerable interest, debate and comment.

Initially, the groundswell for tenancy reform was reflected in work undertaken by a Review Group on the Private Rented Sector Tenancy Regime, set up by the Scottish Government. The group's report, published in 2014, made the case for a new regime that would generate longer term tenancies.1

Throughout the process, however, it appeared that the Scottish Government was trying to juggle multiple objectives: lengthening tenancies and ultimately enabling a local rent restriction regime, but seeking to do so with the consent of landlords, and enabling corporate and institutional build to rent.

Although there has been plenty of initial analysis of the new tenancy, and rent pressure zones, it is too early for there to be sufficient evidence, beyond anecdotes, to assess the actual impact of the reforms.

Whitehead argues, from a review of other European rental market regimes, that Scotland is seeking to deliver security of tenure and rent stabilisation via the rent pressure zone methodology so as to reassure the supply-side sufficiently. However, in practice it may be difficult to operationalise the rent pressure zones.23

Robertson and Young note that the demand for longer tenancies, for security reasons, in part also requires rent predictability. This applies both in terms of when, and how often, rents can rise but also the ability for tenants to challenge what are viewed as excessive rent increases.4 While the initial rents are set at market levels, subsequent rent increases can be monitored by local authorities and evidence built such that, if rents are viewed to be excessive within a designated rent pressure zone, then limits can be set on rent increases. It could be argued that this is a "third generation" rent control measure i.e. one where rent increases are controlled within a tenancy but are unrestricted between tenancies.

Rent Regulation Debate

In a development which is almost as significant as the new tenancy, the 2016 Act also introduces limited real rent restrictions in designated local rent pressure zones. Inevitably, this takes us back to broader debates about the efficacy of rent regulation and the importance of the different forms which it can take (and different housing system contexts).

There are fewer longer-standing arguments than those about the efficacy of rent controls.1 23 These debates turn on conceptual and empirical arguments. Key questions include:

Are rental markets competitive?

What are the key parameters relating to supply and demand in a given housing market?

Is the rent control measure a hard control (e.g. absolute rent ceilings with strong tenure security) or a more sophisticated or ‘softer’ control (e.g. rent increases capped at inflation plus X% with incentives and regular reviews.)?

How does rent control impact on landlord behaviour and practice, including with regards to investment and maintenance?

There are also more fundamental questions about whether private landlords, or indeed rental markets per se, are exploitative. In addition, those with more pro-market perspectives often ask whether regulating rents could be softened, or eliminated completely with the better use of other forms of intervention, e.g. personal subsidies to tenants and carrot and stick incentives for good landlords.

To put this in a Scottish context, some of the key questions include:

The extent to which rent pressure zones will limit unaffordable rent increases and protect tenants; and

The extent to which landlords will view the reforms as the 'thin end of a wedge,' enabling possible tougher forms of rent regulation in future that may inhibit investment.

The 2016 Act allows initial market rents. Where evidence of excessive rent increases is found local authorities can apply to the Scottish Government for a rent pressure zone to be implemented. Within a rent pressure zone landlords will still be able to charge real terms rent increases (albeit on a capped basis). This is a modest intervention. Some authors are also sceptical of how easy it will be for a rent pressure zone to be declared, for example, because of the level of evidence that local authorities must provide to the Scottish Government in their application. 4 5

Whitehead argues that most European countries have some form of rent and tenancy stabilisation regime. She notes that these regimes are highly context and housing system-specific, although there is plenty of evidence that landlords like long term contracts with index-linked rents, providing they have willing tenants. At the same time though, there is a worry that landlords will be deterred by the fear of increased regulation and restriction.5

This is an area where good evaluation can make a big difference. In this respect, the anticipated research, commissioned by the Nationwide Foundation, on understanding the impact on tenants and landlords of changes to the Scottish private rented sector tenancy is a welcome innovation.

Debates about regulatory reform

The reintroduction of rent regulation measures followed the introduction of a number of other regulatory requirements as described earlier (see Figure 6). There has been a long standing debate over the direction, pace and extent of this regulatory reform.

This debate has reflected a range of perspectives including from those seeking minimalist regulation or proportionate/efficient regulation. Other perspectives have included those defending tenants' rights, arguing for the extension of such rights and better enforcement of legislation. Others have stressed the need for regulation to improve standards. More recently, the debate has centred around different and longer tenancies.

This debate was influenced by the UK Government’s review of social housing in England1 as well as the Law Commission's work on private rental regulation in England and Wales, and the independent Rugg Review of private renting (a new updated Rugg Review was published last year2).

More recently, this work has continued in England with a number of recent reports:

The UK Government Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) published a consultation on longer term tenancies in England. It notes the plans and actions on re-regulation that England is pursuing: dispute redress, letting agent fees, registering letting agents and capping deposits and fees. While they note lengthening average tenancies (3.9 years), they see the need for tenancies to grow alongside this average (81% of tenants have 6 or 12 months tenancies). However, despite the benefits of longer tenancies they provide evidence of seven different forms of barriers e.g. short-term tenant requirements. 3

The House of Commons Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee's report on the private rented sector argues for a range of regulatory measures, including stronger legal redress and a range of ways of enforcing higher standards such as additional local authority powers.4

The consumer representative body Which? has also called for a range of regulatory interventions to protect tenant rights but also to improve the quality of the sector in general.5

At the same time, landlords themselves, through their representative body the Residential Landlords Association (RLA), are now publishing commissioned research in a wide range of rental market areas including research on regulatory change.

The RLA commissioned Professor Michael Ball to look at economic aspects of PRS regulation. He argues firmly against longer tenancies and re-regulation, although voluntarily entering into long term agreements is acceptable. He makes the interesting point that European rental markets often have low levels of investment and are only ‘propped-up’ by extensive subsidy and tax breaks. 6 These wider regulatory issues are highly contingent on the evidence we possess and also the veracity of the behavioural assumptions we make about landlords and how they response to changing incentives.

Concluding remarks

An understanding of housing policy, and the PRS in particular, benefits from a housing systems analysis, taking into account the sub-markets and complexity of the sector.

The unexpected growth in buy-to-let and the incremental use of re-regulation suggests that PRS policy follows rather than leads the market. However, many economists and public policy analysts would in any case be sceptical about the capacity of government to lead or shape the housing market.

There remains a striking lack of consensus about what the appropriate role and scale of the PRS should be. This lack of consensus sits behind many of the outstanding debates and disputes about housing policy futures for the PRS.

The impact of regulatory reforms on the PRS, in terms of enforcement, quality and behaviour change remains largely unevaluated. It is essential that the new policies are measured, weighed and evaluated. This is no easy task for the system-wide reasons and data shortages alluded to in this briefing. To do this we need to make the best use of existing data, access new data and give serious consideration to creating new official data sources. We also need a sensible framework with which to understand change in the PRS upon which that data can be sensibly applied.

Annex 1: Relevant Scottish PRS legislation

Table 1: Recent Relevant Scottish Legislation on the PRS, 1988-2016

| Legislation Name | Relevant Summary Features |

| Housing (Scotland) Act 1988 | Deregulated the private rental market in Scotland, introducing two new forms of tenancy in the private sector from 2 January 1989 – the assured tenancy and the short assured tenancy. |

| Antisocial Behaviour etc (Scotland) Act 2004 | Established the framework for the private landlord registration scheme and the system for serving anti-social behaviour notices on private landlords. |

| Housing (Scotland) Act 2006 | The Act’s main purpose was to address problems of condition and quality in private sector housing. The Act included a Repairing Standard setting out the obligations and duties of private landlords. It reformed local authority powers to deal with disrepair in their areas and re-enacted, with changes, the system of licensing of houses in multiple occupation which was contained in secondary legislation. The Act also created the framework to establish the national in tenancy deposit scheme through he Tenancy Deposit Schemes (Scotland) Regulations 2011. |

| Private Rented (Housing) Scotland Act 2011 | This Act amended the private landlord registration system provisions in the 2004 Act with the aim of improving enforcement of the scheme. It introduced a power for local authorities to serve a statutory overcrowding notice. It also made relatively minor changes to the system of HMO licensing in the 2006 Act and other miscellaneous provisions. |

| Housing (Scotland) Act 2014 | This wide ranging Act included the introduction of a letting agent regulation system and the transfer of private rented housing civil cases from the sheriff court to a new Tribunal. |

| Private Housing (Tenancies) (Scotland) Act 2016 | Introduced the open ended new private rental tenancy, procedures to limit rent increases through local rent pressure zones and standardisation of how often rents can increase. |