EU Emissions Trading System

This briefing provides an overview of the EU Emissions Trading System, a carbon pricing policy central to the EU's action climate change. It covers the history, present functioning and planned reform of the policy and explores the options available to the UK after Brexit. This briefing also provides an account of UK and Scottish government policy to date, and the perspectives of key stakeholders. This briefing has been written for SPICe by John Ferrier, on secondment from the Natural Environment Research Council. SPICe thanks all contributors and reviewers. For further information on this subject, please contact Alasdair Reid on 85375.

Executive Summary

The overwhelming scientific consensus is that climate change is occurring due to greenhouse gas emissions from human activity. Since the establishment of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992, an international framework of targets and action on climate change has evolved. This includes the Kyoto Protocol (1997), which set out a target for 37 industrialised countries to reduce their emissions by 5% below 1990 levels; and the Paris Agreement (2015) which set a target of keeping average temperature increase to below 2°C compared with pre-industrial levels.

Emissions reduction targets relevant to Scotland have been set out on an EU, UK and Scottish level. The EU has set key targets for 2020, 2030 and 2050. The EU's 2020 targets are: a 20% reduction in emissions compared to 1990 levels; that 20% of total energy consumed must come from renewable resources; and a 20% improvement in energy efficiency. The EU's targets for 2030 are: a 40% reduction in emissions compared to 1990 levels; that 32% of total energy consumption must be generated from renewable resources; and at least a 32.5% improvement in energy efficiency. By 2050, the EU aims to reduce emissions by 80-95% compared to 1990 levels. At a UK level, a target has been set for an 80% reduction in carbon emissions by 2050 under the Climate Change Act (2008). While Scotland is included in the Climate Change Act (2008), the Climate Change (Scotland) Act (2009) sets an additional target of 42% reduction in emissions by 2020. Furthermore, the proposed Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill, introduced to the Scottish parliament in May 2018, sets a more ambitious target of 90% reduction by 2050, with the option for creating a 100% ('net-zero') target in the future.

Carbon pricing refers to a means of discouraging activities that release carbon dioxide by applying a cost on carbon emissions. This can take the form of a carbon tax, in which a uniform price is applied on each tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e); or this can take the form of a 'cap and trade' scheme, in which an emissions target is set and split into individual units (equal to one tCO2e), which businesses must purchase and surrender each year to match their annual emissions. The cap can then be lowered so that total emissions fall over time. In practice, a hybrid of both systems is often employed.

The EU ETS is considered the cornerstone of the EU's efforts to mitigate climate change and is fundamental to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions from power, industrial and aviation sectors. Introduced in 2005, the EU ETS is a mandatory 'cap and trade' scheme, covering around 45% of the EU's greenhouse gas emissions and accounts for over 75% of international carbon trading. Over 11,000 installations across 31 countries in the European Economic Area (EEA, EU28 + Liechtenstein, Iceland and Norway) are covered, including around 1000 installations in the UK. Under the scheme a cap is placed on overall emissions, which is then reduced over time so that total emissions fall. Within the cap, participants can receive or buy emission allowances, which they are able to trade with other participants as needed, with the overall limit on allowances ensuring that they have value. Each allowance grants the participant the right to emit one tCO2e and at the end of each year that participant must surrender sufficient allowances to cover their annual emissions. However, if a participant does not surrender sufficient allowances cover their emissions, heavy fines are imposed. The EU ETS creates an incentive for installations to invest in emissions reduction and, in theory, allows this reduction to take place by the most cost-effective means available. The scheme is central to the EU's emissions reduction targets.

The 2008 financial crisis created a very large surplus of allowances, with a consequential collapse of the allowance price. By 2013, the allowance price was insufficient for driving investment in low-carbon technology in the power sector. In order to supplement the allowance price set out by the cost of allowances, the UK government introduced the Carbon Price Floor (CPF), which came into effect on 1st April 2013. The CPF is a tax on fossil fuels used to generate electricity, and describes a combined price made up of the EU ETS allowance price and ‘Carbon Price Support’ (CPS), set at £18/ tCO2e.

Although it is not confirmed what route the UK will take regarding carbon pricing post-Brexit, a number of options are available. These options include: Remaining in the EU ETS, Establishing a domestic ETS linked to the EU ETS, Establishing an unlinked domestic ETS or applying a broad-scope, UK-wide carbon tax.

The withdrawal forms the basis for the UK Government's position on post-Brexit carbon price, and commits to 'implement a system of carbon pricing of at least the same effectiveness and scope' as the EU ETS. Furthermore, the political declaration suggests that the EU and UK should seek to cooperate on carbon pricing by linking a domestic ETS to the EU ETS. In a 'no-deal' scenario, the UK will cease to be a part of the EU ETS and the UK Government will institute a 'Carbon Emissions Tax', intended to help meet the UK's emissions reduction targets and provide continuity to businesses.

Introduction

Climate change is a large-scale, long-term shift in the planet's weather patterns and average temperatures. It is driven by emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other potent greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Climate change has occurred throughout the Earth's history due to natural causes. However, there is overwhelming scientific evidence that the warming currently being observed is a direct result of increased greenhouse gas emissions from human activity.

In their Fifth Assessment Report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2014) concluded that they are ‘now 95% certain that humans are the main cause of current global warming’ and that climate change is a consequence of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from human activity. However, they also highlight that we have the solutions available to limit the impact of climate change, including many that ‘allow for continued economic and human development’1.

In January 2018, CBI Scotland said:

However, in order to meet the targets through to 2050, much more must be done – and in what is now a more challenging political context. Following the triggering of Article 50, Brexit requires Scotland and the UK to redefine its relationship with the EU. It is therefore more important than ever that a clear, long-term plan is established in order to give business the confidence to innovate and invest in our low-carbon future in Scotland and across the UK2.

Since the adoption of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992, an international framework of measures to mitigate and combat climate change has evolved. The EU emissions trading system (EU ETS) is an integral part of the EU's contribution to this framework. The EU ETS is a complex, multi-layered scheme which facilitates and regulates the sale and purchase of carbon emissions in Europe. This briefing gives an overview of the EU ETS and, following the decision of the UK to leave the European Union, provides an account of UK and Scottish Government policy on this issue, and the options available post-Brexit.

Greenhouse Gases and Climate Change

Of the greenhouse gases, carbon dioxide (CO2) has received the most significant attention from scientists and policymakers. This is because CO2 emissions are the primary contributing factor to climate change. There are however other potent greenhouse gases, including methane, nitrous oxide and chlorofluorocarbons.

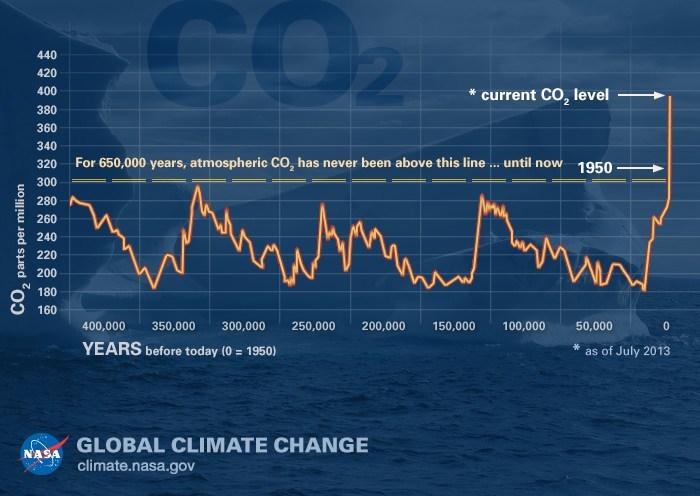

Quantities of greenhouse gases are therefore commonly expressed as tonnes of CO2 equivalent (tCO2e) - a measure of the potency of their contribution to the greenhouse effect1. The atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide reached 410ppm (parts per million) as of November 20182. This is significant as, in records spanning 800,000 years, a CO2 concentration above 300ppm was not observed until 200 years ago 3. In 2014 the IPCC outlined that ‘Emissions of CO2 from fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes contributed about 78% of the total GHG emissions increase from 1970 to 2010’4.

Taken together, the atmospheric concentration of all greenhouse gases reached a concentration of 445ppm in 2015, an increase of 35ppm from 2005. At the time, this placed the likelihood of average global temperature exceeding 1.5°C by 2100 at around 50% 5. More recently, in their October 2018 report the IPCC warned that current efforts to tackle climate change ‘cumulatively track toward a warming of 3°-4°C above pre-industrial temperatures by 2100, with the potential for further warming thereafter’ 6.

In Scotland, greenhouse gas emissions are reported by sector (in million tonnes of CO2 equivalent).

The Paris agreement (December 2015) set out an aim of limiting global temperature rise by 2100 to ‘well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees'7. In October 2018 the IPCC expanded upon the impacts of 1.5° and 2°C of warming in their Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C. They outlined the need for countries to accelerate current mitigation strategies, to reduce the likelihood of extreme weather events associated with 2°C of warming or higher, and keep as close as possible to the 1.5°C target6.

Of the UK's commitment to fighting climate change, Foreign Office minister Mark Field said in September 20189:

The UK is looking beyond our strong record on climate action at home. We are working across the world to help reduce emissions and create a safer, more prosperous future for all people. We also want to help UK businesses capitalise on the growing investment opportunities as countries transition to clean, low carbon economies.

International and National Action on Climate Change

As climate change is a global concern, a number of international initiatives and commitments have been adopted to date1. In 1992, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was established as the main international forum for coordinating international action on climate change2. The stated objective of the UNFCCC is 3:

Achieve […] stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. Such a level should be achieved within a time frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.

To date, 197 countries have joined the convention.

The early UNFCCC negotiations led to the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, which set a target for the 37 industrialised countries and the European Community to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by 5% below 1990 levels for the period 2008-2012 156. This was known as the first Kyoto commitment period. These targets were met; however they were offset by emissions from industrialising countries, leading to an overall increase in emissions. A second commitment period is ongoing (2013-2020), to which the UK and EU are signatories1.

Continuing UNFCCC negotiations led to the Paris Agreement in December 2015, to which 160 countries made voluntary commitments to reduce emissions by 2030. One of the central aims of the Paris Agreement was 8:

Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change.

The Paris Agreement entered force on 4th November 2016 - thirty days after pre established conditions where met. These conditions were that the agreement had been ratified by 55 countries representing at least 55% of total global greenhouse has emissions.

European Union

The EU has established key emissions reduction targets for 2020, 2030 and 2050. The 2020 targets9:

A 20% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions compared with 1990 levels,

That 20% of total energy consumption must be generated from renewable resources,

A 20% improvement in energy efficiency.

For 2030, the EU targets are:

A reduction in greenhouse gas emissions of at least 40% compared to 1990 levels,

That at least 32% of total energy consumption must be generated from renewable resources,

Improvements in energy efficiency of at least 32.5%.

By 2050, the EU aims to reduce emissions by 80-95% compared to 1990 levels. Furthermore, the European Commission has set out a strategic long-term vision for achieving a carbon-neutral European economy by 205010.

United Kingdom

The UK's approach to tackling climate change is set out under the Climate Change Act (2008), which sets the target of an 80% reduction in carbon emissions by 205011. Under the Climate Change Act, the UK Government is required to set legally binding carbon budgets to act as intermediate targets toward the 2050 target. These are set for 5-year periods up to 2050, and act as a cap on emissions over that period. As part of the carbon budgets, future targets are12:

A 37% reduction in emissions by 2020 (compared with 1990 levels),

A 51% reduction by 2025,

A 57% reduction by 2030.

The UK is on track to overachieve on the 2020 target, as UK emissions were 43% below 1990 levels in 2017.

Scotland

Although Scotland is covered by the Climate Change Act (2008), in 2009 the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 was passed by the Scottish Parliament, setting an additional target of a 42% reduction in emissions by 2020. This was in addition to the 80% target set out under the Climate Change Act (2008)13.

However, the proposed Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill, introduced to Parliament in May 2018, sets out a more ambitious target of a 90% reduction in emissions by 2050. Furthermore, it provides for the possibility of creating a 100% target (known as ‘net-zero) by 205014.

Carbon Pricing

Carbon pricing refers to a means of discouraging activities that release greenhouse gases by putting a cost on emissions. If left unregulated, companies and industries that release carbon dioxide have a reduced incentive to cut emissions, therefore carbon pricing has become fundamental to policies for climate change mitigation. The overall objective of carbon pricing is to reflect the cost of the long-term consequences of climate change by increasing the cost of activities responsible for generating emissions1. This is referred to as the ‘polluter pays’ principle2.

There are two main forms of carbon pricing: a carbon tax, and emissions trading or ‘cap and trade’. Both mechanisms are designed to drive efficiencies, and to trigger investment in low-carbon technologies 1.

The choice of carbon pricing strategy is dependent on individual national circumstances and policy objectives. In practice, a hybrid of both systems is often employed, with domestic carbon taxes applied to supplement and stabilise the price of carbon under emissions trading. This is the case in France and the UK, among others 4.

Regardless of method, a carbon price should be high enough to encourage investment in low-carbon alternatives, where the cost of investment is lower than the carbon price. In May 2017, a report of the High-Level Commission on Carbon Pricing put forward their recommendations for an effective carbon price, stating 5:

Based on industry and policy experience, and the literature reviewed, duly considering the respective strengths and limitations of these information sources, this Commission concludes that the explicit carbon-price level consistent with achieving the Paris temperature target is at least US$40–80/tCO2 by 2020 and US$50–100/tCO2 by 2030, provided a supportive policy environment is in place.

Carbon Taxes

A carbon tax defines a set price for the distribution, sale or use of fossil fuels, and is usually calculated as a price per tonne of carbon dioxide (/tCO2). A carbon tax does not set an overall emissions limit, only a price on emissions. Companies or industries subject to a carbon tax can therefore choose to pay the additional tax or invest in reducing fossil fuel consumption. This means that while the carbon price may be stable, the overall quantity of emissions can be uncertain1.

Emissions Trading ('Cap and Trade') Schemes

In theory, emissions trading schemes, also referred to as ‘cap and trade’ schemes, provide a cost-effective means of reducing emissions, in a way that allows for more flexibility in how participants reduce their emissions compared to a carbon tax. Under cap and trade schemes, a government sets an overall limit on the level of emissions of a gas or pollutant. Within the limit, allowances are created, corresponding to one unit of emissions. Participants in the scheme must obtain allowances either directly from the government or from other participants, and surrender sufficient allowances to cover their emissions over a given period. Cap and trade schemes allow participants to decide whether to invest in emissions reduction, or to purchase additional allowances to cover their needs. Conversely, if a participant has a surplus of allowances, they are able to sell them on to others1.

Cap and trade schemes have their origins in efforts to phase out leaded fuel in the USA in the early 1980s. A tradable lead credit program was created to help small refineries meet their lead reduction targets at a time when larger operations were able to implement lead reduction technology at a lower cost. This programme allowed for ‘inter-refinery averaging’, whereby one refinery could produce higher concentrations than others, so long as the average across all refineries was in line with the set limit. Over the phase-down period between 1979 and 1988, the lead credit program was responsible for around 36% of overall lead reduction, accounting for over a reduction of half-million tonnes of lead 23. In a discussion paper covering the leaded fuel phase-down, the authors Newell and Rogers concluded3:

The phase-down program, along with the turnover effects, achieved in 1981 what the fleet turnover alone would not have achieved until around 1987.

The first large scale application of a cap and trade scheme was in the USA, known as the Acid Rain Program (ARP) 5. Introduced in the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments, the ARP sought to reduce emissions of sulphur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) in the US power generation sector, as these are the primary contributors to acid rain6. Within the first year of the programme, emissions had been reduced by 25% compared to 1990 levels and more than 35% below 1980 levels. After 2000, the scheme reduced emissions by a further 14% compared to 1980 levels2.

In 2002, prior to the establishment of the EU ETS, the UK introduced the world's first greenhouse gas emissions trading scheme (UK ETS) which regulated all six greenhouse gases covered by the Kyoto protocol. The voluntary UK ETS was introduced in coordination with the Climate Change Levy (an energy tax) and sectoral Climate Change Agreements, in order to implement the UK's then policy of reducing CO2 emissions to 20% below 1990 levels by 2010. Under the scheme 'direct participants' could trade allowances, as could over 40 industry associations, representing around 6000 companies (known as 'agreement participants'), who were given access to the scheme through Climate Change Agreements negotiated with the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) in return for an 80% discount on the Climate Change Levy. However, in practice only around one quarter of participants in the UK ETS actually engaged in emissions trading8. The UK's experience with it's domestic ETS played a central role in informing the development of the EU ETS9. Sir John Bourn, former head of the National Audit Office said in April 200410:

The Department's voluntary Emissions Trading Scheme was a pioneering initiative which has brought about significant achievements. There are lessons to be learned on Scheme design and implementation should further similar trading schemes be set up, but UK companies should benefit from their early experience when a European Union Scheme is introduced in 2005.

What is the EU Emissions Trading System?

The EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) is the cornerstone of the EU's efforts to mitigate climate change and the fundamental mechanism for reducing it's greenhouse gas emissions across power, industrial and aviation sectors1. It is the world's first and largest emissions trading system, covering around 45% of the EU's greenhouse gas emissions, and accounts for over 75% of international carbon trading. Others exist in New Zealand2, South Korea3, California4 and Quebec5, with a scheme in China6 due to come into operation soon.

Introduced in 20051, the EU ETS is a mandatory ‘cap and trade scheme’ which regulates greenhouse gas emissions from over 11,000 installations across 31 countries in the European Economic Area (EEA, EU28 + Liechtenstein, Iceland and Norway), with around 1,000 installations located in the UK8. From 20129, participation in the EU ETS became mandatory for commercial aviation operating within or between EU ETS countries, with around 500 aircraft operators now covered by the scheme.

Under the scheme1 a cap is placed on overall emissions, which is then reduced over time so that total emissions fall. Within the cap, participants can receive or buy emission allowances, which they are able to trade with other participants as needed, with the overall limit on allowances ensuring that they have value. Each allowance grants the participant the right to emit one tCO2e8. At the end of each year that participant must surrender sufficient allowances to cover their annual emissions, as confirmed by an independent verifier9. If a participating installation has a surplus of allowances, they can choose to sell their surplus to another installation that may be short, or keep the spare allowances for future use. However, if a participant does not surrender sufficient allowances cover their emissions, heavy fines are imposed. For example, Shell's Fife natural gas liquids plant was fined £40,056 by the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), for failing to surrender sufficient allowances in 2013, 2014 and 201513. Currently fines are imposed at a rate of €100 /tCO2e, which greatly exceeds the current allowance price of ~€20/ tCO2e.

The EU ETS creates an incentive for installations to invest in emissions reduction and, in theory, allows this reduction to take place by the most cost-effective means available. The scheme is central to the EU's policy of reducing emissions by 40% compared to 1990 levels by 2030.

Article 1 of the EU ETS directive (Directive 2003/87/EC) states that the scheme14:

[…] established a system for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Union, in order to promote reductions of greenhouse gas emissions in a cost-effective and economically efficient manner.

The EU ETS currently covers carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrous oxide (N2O) and perfluorocarbon (PFC) emissions from different sources1, as these can be confirmed with a high degree of accuracy.

The future of the UK's participation in the EU ETS is uncertain. Under the terms of the yet to be ratified Withdrawal Agreement16 the UK would meet its obligations to the EU ETS only until the end of the proposed transition period (31st December 2020). Some stakeholders17 have recommended that the UK continue to participate in the EU ETS, while the withdrawal agreement sets out a commitment to 'implement a system of at least the same effectiveness and scope'. In October 2018, Energy and Clean Growth Minister Claire Perry stated18:

The Government is considering all factors in relation to the UK's future participation, or otherwise, in the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), in consultation with stakeholders. A range of long-term alternatives are currently under consideration including continued participation in the EU ETS after 2020, a UK ETS (linked or standalone) or a carbon tax. We welcome input from stakeholders and we intend to share more details on policy design in due course.

History of the EU ETS

The origins of the EU ETS date back to the EU's adoption of the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in late 19971. Under the Kyoto protocol, two principles were introduced that were fundamental to the establishment of the EU ETS2:

An absolute emission targets for industrialised countries.

A series of ‘flexible mechanisms’ designed for the exchange of emissions units between countries as an international emissions trading scheme (This is discussed in greater detail in Box 1).

For more detailed information on the Kyoto mechanisms, see Box 1.

In March 2000, the European Commission then presented a Green Paper ‘on greenhouse gas emissions trading within the European Union’, which set out the initial designs for the EU ETS and formed the basis for stakeholder discussions which then shaped the scheme. The Green Paper outlined the possibility of an EU-wide cap on emissions, designed to work in coordination with measures taken to reduce emissions on a member-state level. The plans outlined an initial pilot phase from 2005-2007 and full implementation in time for the first Kyoto commitment period from 2008-2012. These periods ultimately formed phase 1 and phase 2 of the EU ETS3.

The EU ETS is currently in its third phase, and preparations are underway for phase 4 (2021-2030).

Box 1 – Kyoto Protocol Mechanisms

With the adoption of the Kyoto protocol in 1997, three ‘flexible mechanisms’ were introduced. These mechanisms were designed to supplement domestic actions taken by signatories to meet their emissions targets. According to the UNFCCC, the Kyoto mechanisms were intended to4:

Stimulate sustainable development through technology transfer and investment.

Help countries with Kyoto commitments to meet their targets by reducing emissions or removing carbon from the atmosphere in other countries in a cost-effective way.

Encourage the private sector and developing countries to contribute to emission reduction efforts.

Clean Development Mechanism (CDM)

The clean development mechanism allows developed countries with targets under the Kyoto protocol to implement an emissions reduction project in a developing country. Such projects earn Certified Emission Reduction (CER) credits which are equivalent to one tCO2e, can count towards meeting Kyoto targets, and can be sold5.

Joint Implementation (JI)

Joint implementation allows a developed country to invest in emissions reduction projects in a second developed country. JI projects earn Emission Reduction Units (ERUs), equivalent to one tCO2e, which can be counted towards their emissions reduction targets and can be sold. JI allows a flexible means for a country to meet their targets under the Kyoto protocol while the host country benefits from foreign investment and the sharing of expertise6.

Emissions Trading

The emissions trading mechanism created a new tradable commodity in the form of emissions reduction units. Under this mechanism specifically, national emissions targets were divided up into assigned amount units (AAUs), each equal to one tCO2e, which allowed a country to sell any excess emissions capacity to another that may have failed to meet its targets. This formed the conceptual basis for future carbon markets including the EU ETS, the largest emissions trading system. Furthermore, it should be noted that the EU ETS does not accept AAUs for compliance.

Emissions credits (CER, ERU, AAU) from all flexible mechanisms are equal to one tCO2e and were designed to be compatible with other credit-based schemes. This allows for maximum flexibility and coordination across different emissions reduction schemes7.

In order to participate in the Kyoto mechanisms, countries were required to meet a series of requirements4:

They must have ratified the Kyoto Protocol.

They must have calculated their ‘assigned amount’ (emissions target) in terms of tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions.

They must have a national system for measuring and verifying emissions reductions.

They must have a national registry to record and report the creation and movement of emissions units.

They must annually report emissions.

Phase 1 – Pilot Phase (2005-2007)

Phase 1 of the EU ETS has been described as a ‘learning by doing’ phase1. It was primarily designed to test how allowance prices would behave within the market, and to allow participants to familiarise themselves with the monitoring, reporting and verification systems2. Launched in January 2005, phase 1 established the EU ETS as the world's largest carbon market and included all of the then 25 member states3. During phase 145:

Only CO2 emissions from installations in power and heat generation, and industrial sectors including iron, steel, cement and oil refining were covered.

Member states had the freedom to determine their own emissions cap and decide how allowances would be allocated to installations under their own National Allocation Plans (NAP).

The overall EU cap was calculated as the total of all NAPs.

Almost all allocations were free, and the overall number was determined based on historic emissions – in an approach known as ‘grandfathering’.

The penalty for non-compliance was €40/tCO2, and the excess emissions were deducted from the subsequent year's annual total.

The linking directive introduced in November 2004, allowed for the use of clean development mechanism credits (CERs) earned from large hydro-electric projects to be used for compliance purposes.

In the second year of phase 1 it was discovered that allowance allocation had been significantly higher than required and the resulting surplus of allowances caused the market price to drop from around €30/tCO2 to near zero by the end of phase 11. By the end of phase 1 the EU ETS had been responsible for a 3% reduction in EU emissions4.

Phase 2 – First Kyoto Commitment Period (2008-2012)

Phase 2 of the EU ETS was planned to coincide with the first Kyoto Protocol commitment period1. At the start of phase 2 (1st January 2008) the EEA countries Liechtenstein, Iceland and Norway were incorporated into the scheme2. Taking on board lessons from phase 1, the EU ETS was revised for phase 2, changes to the scheme included3456:

The scope of the scheme was extended to include an opt-in for nitrous oxide (NO2) from nitric acid production.

Up to 10% of allowances were distributed by auction instead of free allocation.

The penalty for non-compliance rose to €100/tCO2e.

The scheme began to accept credits earned from both CDM and JI projects to be used for EU ETS compliance purposes (Box 1). This was intended to provide more flexibility for businesses, and led to the equivalent of 1.3B tCO2e on the market. This made the EU ETS the largest source of demand for CDM and JI credits.

Towards the end of phase 2 (from 1st January 2012) aviation was brought under the system.

In an effort to stabilise the allowance price, a ‘banking’ system was introduced, allowing participants to carry over unused allowances from phase 2 to phase 3.

To address the oversupply of allowances from phase 1, the overall total was reduced by 6.5% compared to 2005.

Despite the measures taken to reduce oversupply, the financial crash of 2008 led to a significant reduction in industrial output, and consequently a sharp drop in demand for EU ETS allowances. This led to a massive surplus and the allowance price falling from €30 to €7/tCO2e4. By the start of phase 3, there were around 2 billion surplus allowances on the market, more than an entire year's budget8.

Phase 3 – A Developed Emissions Trading System (2013–2020)

Major reforms were outlined by the European Commission in 2009, which came into force for the start of phase 3 (the current phase) in 20131. Phase 3 coincides with the second Kyoto commitment period2. Phase 3 marked the transition from a learning phase to a fully formed, centralised, EU-wide policy tool. Major changes included34567:

The incorporation of Croatia into the EU ETS from 1st January 2013.

The inclusion of perfluorocarbon gases from aluminium production under the scheme.

The introduction of a single EU-wide emissions cap, to be reduced by 1.74% per year up to 2020 (referred to as a linear reduction factor, LRF).

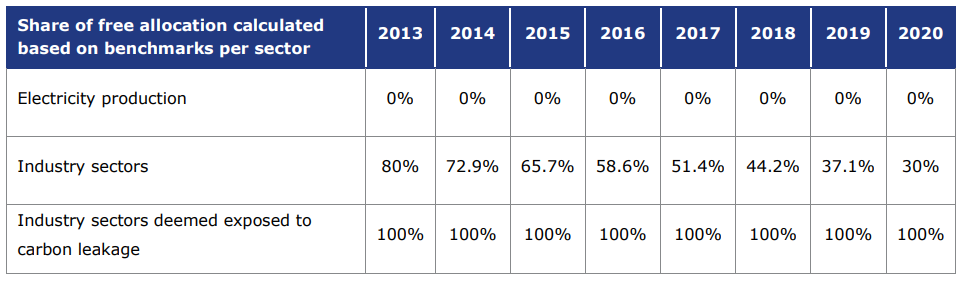

Free allocation to industrial installations (other than power generation) was determined using a system of ‘benchmarks’, which are calculated based on the installation's output/input. These installations received 80% of their benchmark-determined allocations, to be reduced to 30% in 2020. Any further allowances needed are to be obtained by trading.

Around 40% of EUAs were distributed by auction, covered by the EU ETS Auctioning Regulation.

The Union Registry was established as a central record of all allowance holdings and transactions.

The NER300 innovation fund (Box 3) was established, using revenue from auctions to fund investment into low-carbon technologies.

The primary challenge during phase 3 has been the low allowance price, arising from the surplus carried over from phase 2. To address this, the decision was taken to postpone the auctioning of 900 million EUAs until the end of phase 3, in a process known as ‘back-loading’. Furthermore, the European Commission proposed a market stability reserve (MSR) designed to balance supply and demand by adjusting auctioning volumes8. The MSR is part of the proposed framework for phase 4. A more detailed account of the domestic functioning of phase 3, and the proposed framework for phase 4 is discussed later, in 'Phase 4 - Meeting 2030 Targets'.

Phase 3 and Domestic Implementation

Currently underway and running from 2013-2020, phase 3 of the EU ETS represents a notable development from phase 1 and 2. The most significant changes include1:

The introduction of centralised, EU-wide rules of allocation

An emissions cap that decreases by 1.74% per year (linear reduction factor)

The steady phase out of free allocation over phase 3, to be replaced with auctioning as the primary method of allowance allocation

A new method of free allocation based on ‘benchmarks’.

In the UK, phase 3 of the EU ETS has been augmented with a complex series of overlapping levies and taxes, designed to manage the domestic carbon price in addition to the EU ETS2.

Free Allocations and Benchmarks

Unlike phases 1 and 2 during which most allowances were distributed for free, around half of allowances will be auctioned over phase 3. Furthermore, free allocation still takes place for sectors deemed at risk of 'carbon leakage', defined as ‘an increase of emissions outside the EU because of EU climate policies’ (Box 2)12.

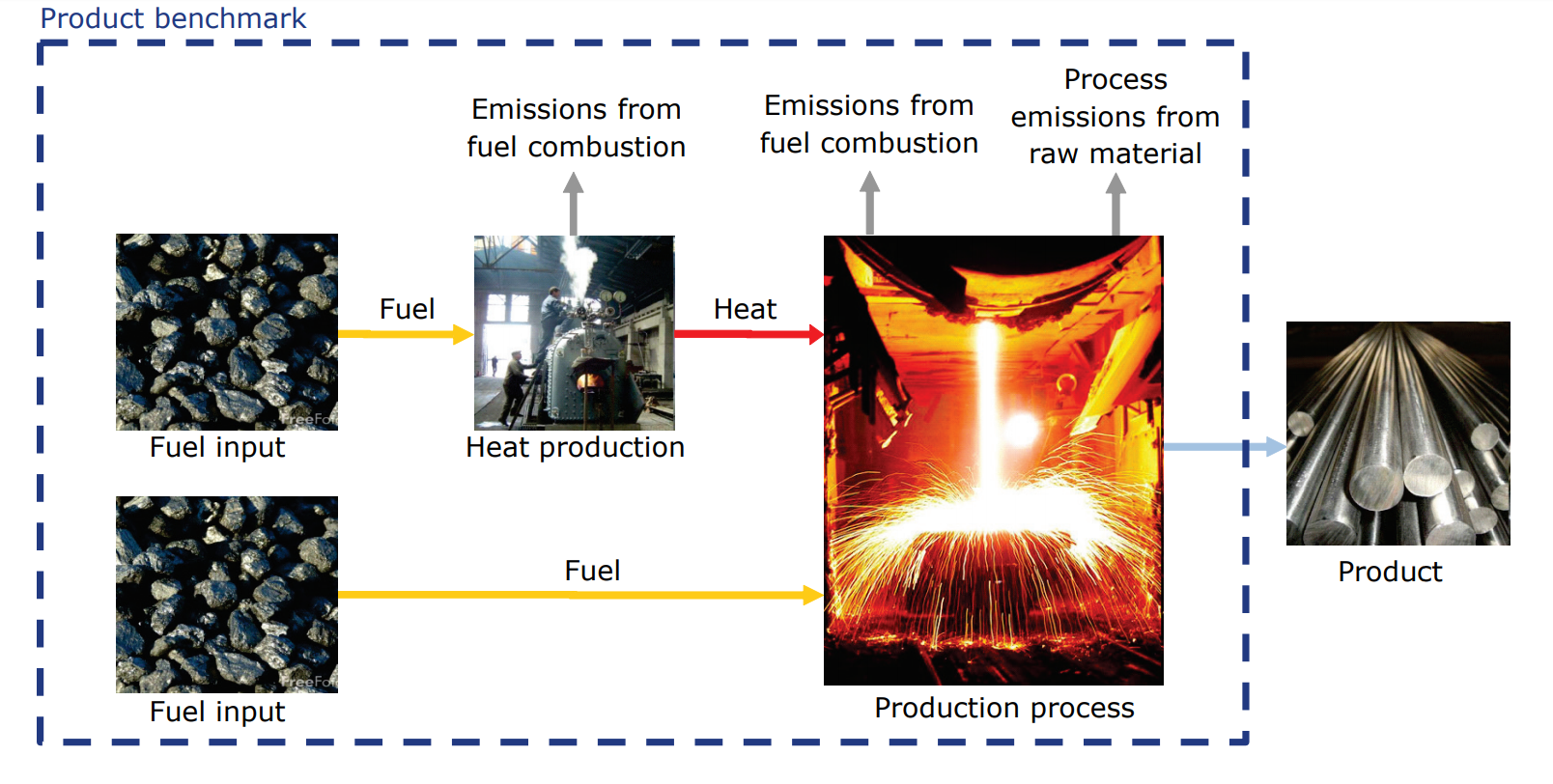

The level of free allocation a sector receives is determined using 'product benchmarks'. A benchmark is the average level of greenhouse gas emissions (in tonnes of CO2) from the top 10% most efficient installations for a certain product. This benchmark will take into account all of the processes and emissions associated with the manufacture of a given product. This provides a reference point against which a sector's level of free allocation can be calculated3. Benchmarks have been established for 52 products and cover 75% of industrial greenhouse gas emissions within the EU ETS.

Before phase 3 began, member states were required to submit allowance allocation plans, known as National Implementation Measures (NIMs), which required approval by the European Commission. At the start of phase 3 in 2013, installations not deemed at risk of carbon-leakage received free allocations equal to 80% of their benchmark-determined allocation. This proportion is then reduced each year and will reach 30% by 2020, with the expectation that this will continue to 0% by 2027. As of 2019, benchmark-defined free allocation is at 37.1%. This reduction is designed to phase out free allocation as a means of allowance distribution, to be replaced with member state auctions. Participants are expected to obtain their remaining allowances through auction or trading, or decrease their emissions. The power generation sector receives no free allocation whatsoever, and can only receive allowances via auctions, although this does not apply to the modernisation of the power sector in certain member states3.

Certain sectors are deemed at risk of ‘carbon leakage’ (Box 2). These sectors face exposure to competition outside the EU due to the additional costs of emissions and therefore receive 100% of their benchmark-defined allowances by free allocation.

The number of free allowances a participant is entitled to is determined by a calculation that takes into account the relevant benchmark, and the risk of carbon leakage faced by the business. Once this has been determined for every participant, the total is adjusted through the application of the 'cross-sectoral correction factor' (CSCF). The CSCF removes a uniform number of allowances from all allocations to ensure the total does not exceed the maximum number of allowances available for allocation. Finally, the yearly 1.74% reduction in allowance cap is applied5.

Box 2 - Carbon leakage

Carbon leakage refers to a situation in which increased production costs due to national climate policies lead companies to outsource production to a different country with more relaxed climate polices (‘relocation’)3. This results in an overall global increase in emissions. In addition to relocation, carbon leakage can also occur through competitive disadvantage7. In this case, due to increased costs, a company under strict climate policy has a reduced market share relative to international competitors operating under comparatively relaxed emissions standards. This leads to the lightly-regulated competitors increasing their share of global production, and results in increased overall emissions.

Carbon leakage has been a major concern for the EU ETS in phase 3, and the European commission has compiled a list of sectors deemed at risk of carbon leakage (e.g. cement production)8. The assessment criteria for carbon leakage take into account the projected additional costs for sectors due to the EU ETS, and the amount of international trade in which a sector engages9. Sectors on the carbon leakage list receive 100% of their allowances allocated for free, based on benchmarks. However, if they are less efficient than the benchmark value (i.e. if they emit more CO2 per unit of product), then they are required to purchase additional allowances to cover this shortfall. This is intended to alleviate the impact of additional costs and prevent carbon leakage. As of 2014, the carbon leakage list covered 164 sectors, representing more than 95% of European manufacturing emissions10.

This approach has been criticised, with some commentators questioning the methodology used to determine at-risk sectors. In 2014, Carbon Market Watch highlighted that when calculating additional costs for sectors as part of carbon leakage assessments, the allowance price was assumed to be €30/tCO2, despite it being around €5/tCO2 at the time11. While in a 2017 study, the German Institute for Economic Research found no evidence of carbon leakage occurring in European manufacturing. They therefore concluded that current the EU ETS policy of free allocation overcompensates many sectors.

This was mirrored by the climate think-tank Sandbag, who stated in May 2017:

Sandbag considers the on-going free allocation approach for avoiding displacement of industrial activities to be flawed. It leaves some highly emitting sectors with little or no carbon price incentive to decarbonise. Indeed, in most Member States the cement sector ends up with a carbon asset even without emissions intensity reductions.

Reform of carbon leakage rules has been central to the proposed framework for EU ETS phase 412. While free allocation will continue for the most at-risk sectors, the rules will be revised to phase out free allocation for less-exposed sectors. More detail on phase 4 of the EU ETS is outlined in 'Phase 4 - Meeting Paris Targets (2021-2030)'.

Allowance Auctioning

Auctions have become the default method of allowance distribution since the start of phase 3. Each year the auctioned portion of allowances will increase as the benchmark-determined free allocation decreases. The European Commission estimates that 57% of allowances will be distributed by auction over the 2013-2020 period1.

Member states are responsible for auctioning their share of allowances. However, not all auctionable allowances are distributed to member states automatically, as certain portions of the total are initially set aside. The sequence of events is as follows2:

Firstly, 5% of the total allowances are set aside for the New Entrant Reserve (NER), to be kept for any new participants to the EU ETS who join during phase 3 (for more information on the NER, see Box 3).

Of the allowances to be auctioned, 10% is shared amongst low-income member states to assist in emissions reduction. This is also intended to increase investment of auction revenues in emissions-reducing technologies.

A further 2%, referred to as a ‘Kyoto bonus’, is granted to 9 EU member states that had already reduced their greenhouse emissions by 20% by 2005 (relative to the reference year set out by the Kyoto Protocol).

The remaining 88% of allowances to be auctioned are then distributed to member states based on their share of greenhouse gas emissions during phase 1.

While member states are entitled to auction revenues, at least 50% must be used for climate change mitigation. The amended EU ETS directive states that3:

Given the considerable efforts necessary to combat climate change and to adapt to its inevitable effects, it is appropriate that at least 50 % of the proceeds from the auctioning of allowances should be used to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, […] to fund research and development for reducing emissions and adaptation […]

Over the period 2013-2015, around €11.8 billion in auction revenue was generated by member states. Of these revenues approximately 82% was used for climate and energy purposes4.

Auctions primarily take place on a common auction platform, while some member states have chosen to use a separate ‘opt-out’ auction platform, as Poland, the UK and Germany have chosen to do. ICE Futures Europe (ICE) acts as the UK’s auctioning platform. The UK has chosen an opt-out platform as it wishes to continue the allowance auctioning platform it set up prior to the EU ETS (ICE). The European Energy Exchange EG (EEX) acts as the auctioning platform for 25 EU member states and the thee EEA countries: Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland. Additionally, the EEX also serves as the opt-out platform for Germany2.

Box 3 - New Entrant Reserve and NER300

New Entrant Reserve

The new entrant reserve (NER) is an EU-wide pool of emissions allowances held in reserve to allocate for free to eligible new installations joining the EU ETS, and those already participating that are increasing their industrial capacity6. The NER is created from 5% of the overall total of EU ETS allowances.

A new entrant is considered to be2:

A new installation joining the EU ETS.

An installation re-entering the EU ETS.

An existing installation undergoing a capacity increase.

As of 2017, 23.8% of allowances from the NER had been distributed or reserved for allocation, leaving 76.2% in the reserve. It was decided that unused allowances from the NER would form part of the market stability reserve (MSR) for phase 46.

NER 300

The NER300 is a funding programme for the demonstration of commercially viable carbon capture and storage (CCS) and renewable energy technologies (RES). It has been funded through the sale of 300 million allowances from the NER up to December 2015. CCS projects refer to efforts to capture CO2 resulting from industrial activity, and store these emissions so they do not enter the atmosphere9. RES refers to methods of energy generation that do not use fossil fuels. Examples renewable energy technologies include: Bioenergy, solar, geothermal, wind, tidal and hydroelectric.

Over the course of phase 3, the NER300 has raised over €2.1 billion from the sale of allowances, with an additional €2.7 billion in private investment10. These were used to fund 39 projects across the EU. NER300 funding for renewable energy generation is paid out to installations as they produce energy, and is intended to supplement support that they may receive from other schemes, such as green certificates 119. In the UK these green certificates are Renewables Obligation (RO)13 for large renewable electricity projects, and Feed in Tariffs (FITs) for smaller projects, among others14.

Carbon Price Floor

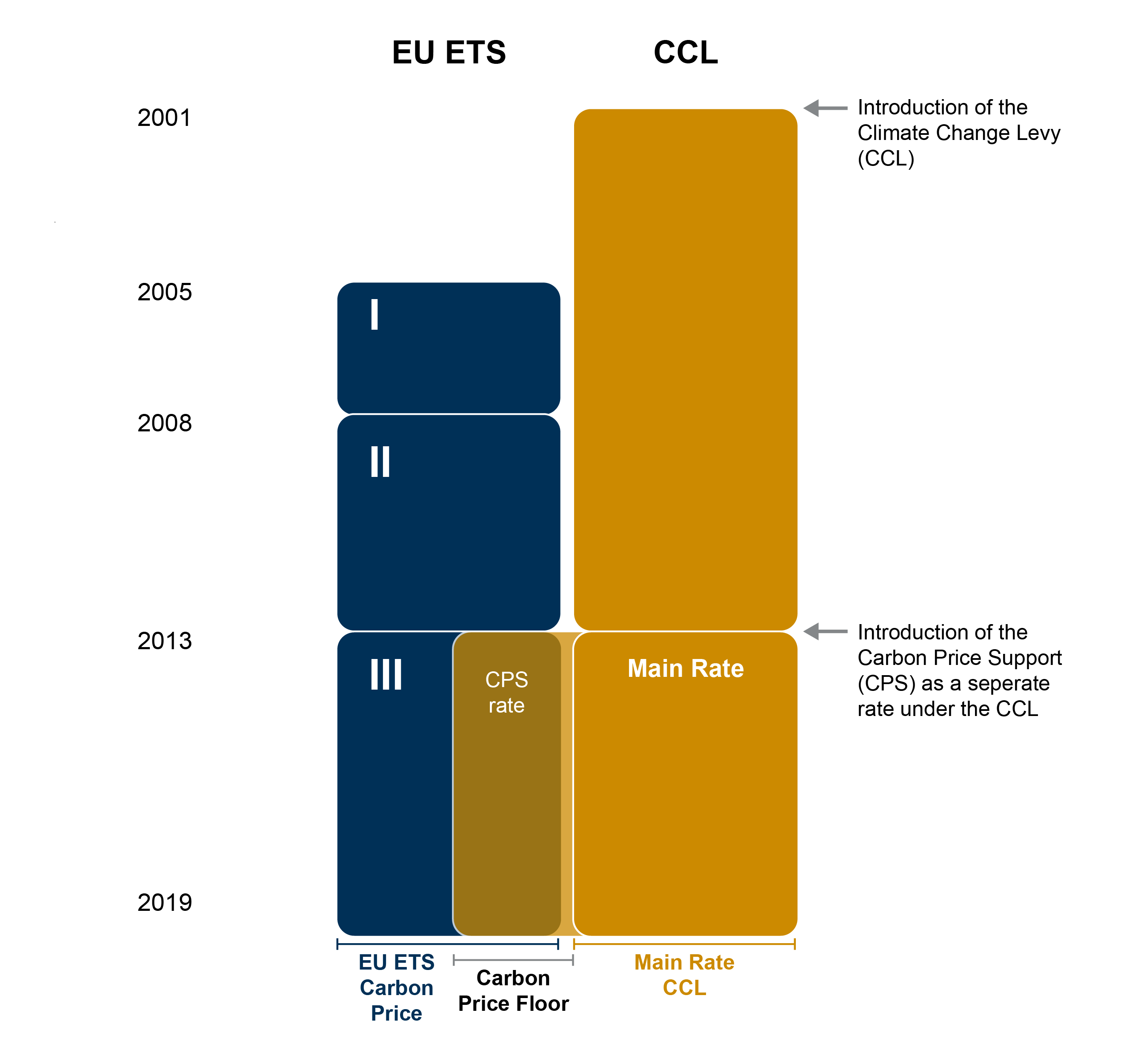

Following the oversupply of allowances in phase 2 resulting from the 2008 financial crash, the price of EU ETS allowances had dropped significantly - to less than €7/tCO2 at the start of phase 31. At this price, the EU ETS was insufficient for driving investment in low-carbon technology for electricity generation in the power sector. In order to supplement the carbon price set out by the cost of EUAs, the UK government introduced the Carbon Price Floor (CPF), which came into effect on 1st April 2013. The CPF is a tax on fossil fuels used to generate electricity, and describes a combined price made up of the EU ETS allowance price and ‘Carbon Price Support’ (CPS) rates2.

The CPS rates are set out under the Climate Change Levy, a pre-existing energy tax (as opposed to an emissions tax) which was implemented in 2001 to tax supplies of electricity and fuel used by industry, public services, commercial and agricultural sectors 3. The ‘main rates’ of the Climate Change Levy were determined by the quantity of emissions released by the types of energy and fuel (e.g. electricity, gas, solid fuels) used by these sectors, but did not apply to the power generation sector. The CPS rate added to the Climate Change Levy in 2013 is a separate rate targeting the power generation sector, and was primarily intended to encourage movement away from coal-powered electricity generation4.

The CPS was originally intended to increase yearly to £30/tCO2 by 2030, but was capped at £18/tCO2 until 2021. The cap was introduced by the UK government in the 2015 spring budget, following concerns from the CBI that additional costs put UK companies at a competitive disadvantage5. Overall, the CPF has reduced the use of coal in electricity generation, from 41% in 2013, to less than 8% in 2017. This has created a shift towards gas-powered electricity generation which, as gas emits less CO2 per unit of electricity than coal, has led to a drop in the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions6.

There are mixed opinions on the CPF; some commentators have welcomed the supplemented carbon price, but suggest it does not go far enough, while others have expressed concern that the costs are passed on to consumers in the form of higher energy bills.

Commenting on the decision of former chancellor George Osborne to cap the CPF at £18/tCO2, Senior Campaigner at Friends of the Earth, Liz Hutchins said7:

This is the minimum the government needed to do to keep to its commitment of phasing out dirty coal power stations. But if it’s to complete the job of ending coal, the CPS [carbon price support] needs to be extended to 2025.

Pete Moorey, Director of Advocacy and Public Affairs at the consumer rights group Which?, expressed concern that electricity bills would increase as a result of the CPF, stating that8:

The government's own figures suggest that the tax, due to start in April 2013, will add around 1-2% to electricity bills in 2013, rising to as much as 6% by 2016.

In June 2018, the Cambridge University Energy Policy Research Group released a paper in which they analysed the impacts of the domestic CPF and similar policies in other EU and non-EU countries. They concluded that a reformed CPF extended to an EU-wide level would improve the EU ETS by stabilising the carbon price6:

We have argued that an EU-wide CPF for the power sector would constitute a significant improvement to the EU ETS. It would help re-affirm the EU's position as a climate leader and contribute to achieving decarbonisation targets. […] Combining it with a carbon price ceiling - to create a price corridor - might also make the policy more attractive to countries concerned about volatile carbon market prices.

Market Stability Reserve

A significant surplus of EU ETS allowances has built up since 2009 due to the economic crisis and high imports of international emissions credits (e.g. Joint Implementation and Clean Development Mechanism credits). This led to a drop in carbon prices and a reduced incentive for emissions reduction. There were initial efforts to reduce the surplus of allowances by postponing (backloading) the auction of over 900 million allowances in 2015, to be returned in 20201.

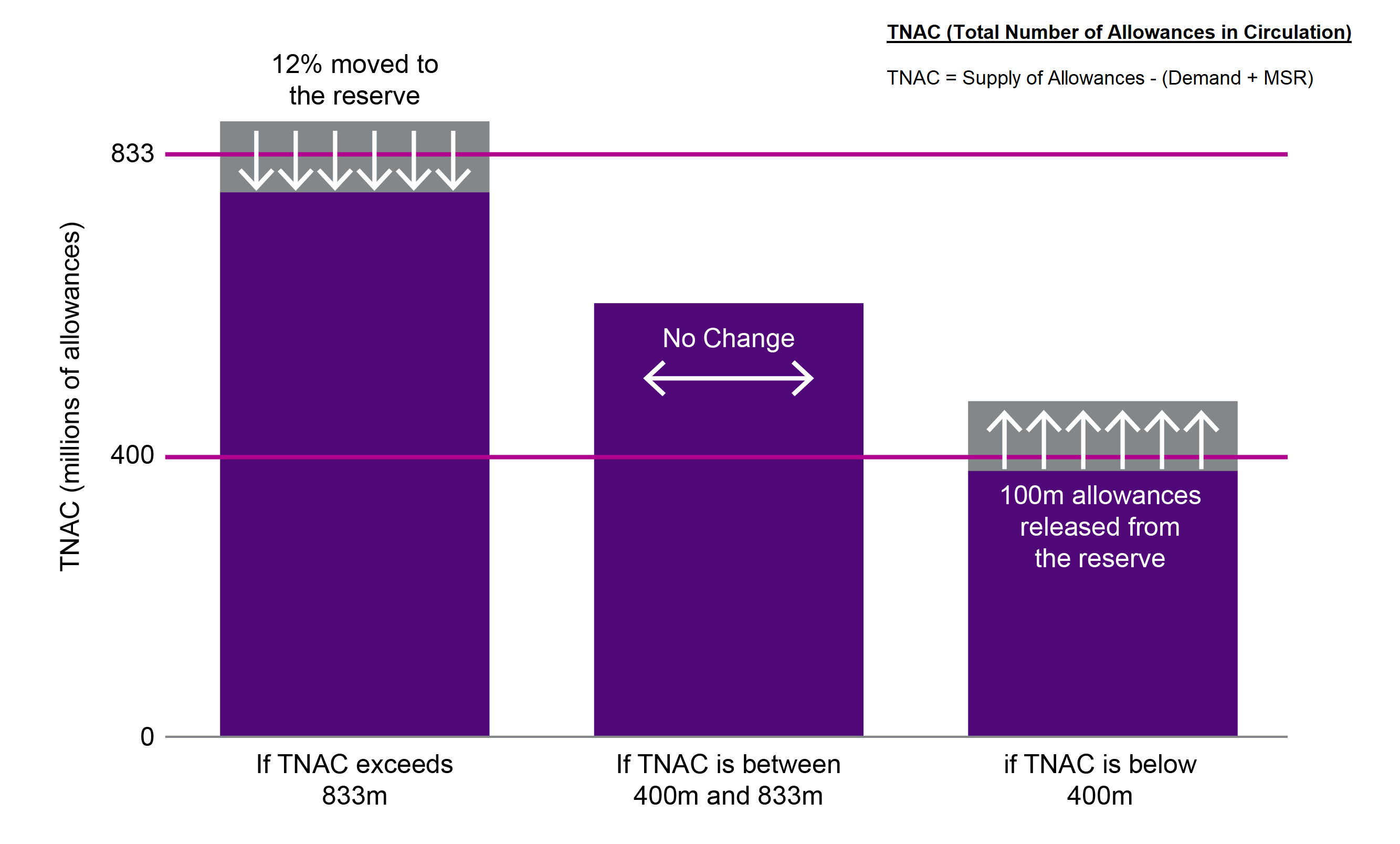

Recently however, the market stability reserve (MSR) was introduced as a more permanent solution to the problem. The MSR is a reserve of allowances designed to adjust the number available for auction by adding or removing allowances depending on the total number in circulation. It is expected that this will protect the EU ETS against instability in the price of allowances by preventing either extreme surplus or depletion. The MSR entered operation in January 2019 and was initially supplied with the 900 million backloaded allowances, which will no longer be returned to auction in 20202.

The MSR functions using defined thresholds at which allowances will be added to, or released from the reserve3:

After 2023, if the total number of allowances in circulation exceeds 833 million, 12% will be taken out of circulation and moved to the reserve. For the initial years of MSR operation (2019-2023) 24% will be moved to the reserve if the threshold is exceeded.

Conversely, if it drops below 400 million, 100 million additional allowances per year will be released from the reserve and added to the pool available for auction.

At the end of phase 3, all unallocated allowances will be transferred to the market stability reserve1. While the exact number cannot be known until the end of the phase in 2020, market analysts estimate that between 550 and 700 million allowances could be added to the reserve. As the total number of allowances in circulation was around 1.65 billion (15th May 2018), well above the 833 million threshold, 265 million allowances will be moved to the MSR over the first 8 months of 20195. This roughly equates to 16% of the total.

However, in 2016 the climate thinktank Sandbag expressed concerns that if the MSR grew too large there would be detrimental impacts on the EU's long-term climate goals. They estimated that the market stability reserve could grow by between 3.5 and 5 billion allowances by the end of phase 4 in 2030 – between 2 to 4 years’ worth of EU ETS emissions. Such a large reserve of allowances would mean that, at a rate of 100 million returning from the reserve per year, the last allowances wouldn't be released until after 20606. If unresolved, this has the potential to undermine the EU's goals of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, which overlaps with its contribution to the Paris Agreement. To address this, Sandbag proposed that the MSR be capped at 1 billion allowances, and that any surplus allowances above the cap be invalidated.

Phase 4 - Meeting 2030 Targets (2021-2030)

In October 2014, initial elements of the the EU's 2030 climate and energy framework were adopted, with the intention of delivering the EU's Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement1. An NDC sets out the actions and targets a signatory to the Paris Climate Agreement will put in place to contribute to keeping global temperature increases below 2°C. The EU's NDC set out three central targets to be met by 2030:

At least 40% cuts in greenhouse gas emissions (compared to 1990 levels),

At least 32% share for renewable energy,

At least 32.5% improvement in energy efficiency.

In order to meet the target of a 40% reduction in greenhouse gases, the EU ETS would have to produce emissions reductions of 43% in sectors covered by the scheme. To achieve this, significant revisions to the EU ETS for phase 4 were proposed, which finally entered force in April 2018, with a commencement date of 1st January 20212.

On the adoption of the phase 4 reforms, Commissioner for Climate Action and Energy Miguel Arias Cañete said3:

Today's landmark deal demonstrates that the European Union is turning its Paris commitment and ambition into concrete action. By putting in place the necessary legislation to strengthen the EU Emissions Trading System and deliver on our climate objectives, Europe is once again leading the way in the fight against climate change. This legislation will make the European carbon-emissions market fit for purpose. I welcome in particular the robust carbon leakage regime that have been agreed and the measures further strengthening the Market Stability Reserve

The primary objective of the phase 4 revisions is to increase the pace of emissions reductions in order to meet the 2030 target. These revisions include4:

An increase to the linear reduction factor, from 1.74% to 2.2%,

Significant changes to the market stability reserve (MSR),

Revised carbon leakage rules,

The expansion of the current low-carbon technology funding programme, NER300, into a new ‘Innovation Fund’,

The development of a power sector ‘Modernization Fund’.

Some of these revisions are discussed in greater detail below:

The Market Stability Reserve

The purpose of the MSR is to stabilise the price of allowances by reducing the number in circulation (i.e. the supply of allowances minus demand). Initial designs provided for the movement of 12% of allowances to the MSR if the total number in circulation exceeds 833 million5. As part of the phase 4 revisions, this has been increased to 24% per year for the years 2019-2023. In addition, as of 2023 allowances in the MSR that exceed a certain threshold will be invalidated. This measure is designed to prevent unsustainable growth of the reserve6.

Revised Carbon Leakage Rules

While the sectors most at risk of carbon leakage will continue to receive 100% free allocation over phase 4 (at benchmark levels, which are also being recalculated), those sectors considered to be less exposed will have free allocations phased out after 2026. Additionally, allocations will be reviewed annually so that they better reflect each installation's actual production levels. The list of installations eligible for free allocation will also be updated every 5 years. Lastly, the product benchmarks used to determine the level of free allocation for installations will be updated twice in phase 4, so as to better reflect improvements in production efficiency4.

The Innovation Fund

Intended to build upon the existing NER300 programme, the innovation fund provides financial support for projects demonstrating innovative renewable energy technologies and carbon capture and storage8. Financing for the innovation fund is provided by the sale of 400 million allowances, which the European Commission estimate will raise up to €10 billion. Furthermore, the sale of an additional 50 million allowances taken from the MSR before the end of phase 3 will allow the fund to start operating before 20219.

Modernisation Fund

The modernisation fund will provide support for investments in the modernisation of the power sector and energy systems in the 10 lowest-income EU member states (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Slovakia). The focus of the modernisation fund will be transition away from coal and lignite powered energy generation, and to increase efficiency. Financing will be provided by the sale of 2% of the total quantity of allowances in phase 4, with the possibility of an increase to 2.5%10.

While phase 4 of the EU ETS is intended to deliver the EU’s Paris Agreement commitments, some commentators have argued that the current plans are insufficient to meet this goal. Analysis by Carbon Tracker Initiative concluded that, in order to produce emission reductions in-line with Paris Agreement targets by 2030, the linear reduction factor would have to be increased from 2.2% to 4.0%. They argue that this would raise carbon prices to a level that will successfully end coal and lignite power generation, resulting in a reduction of 1.6 billion tCO211. Carbon Market Watch outlined a similar view, suggesting that a linear reduction factor of 4.2% would be required to decarbonise the EU's energy sector by 204012.

However, it is expected that for a number of reasons the phase 4 framework will be reviewed before 2030. These include6:

Upcoming discussion of the EU’s 2050 energy targets,

An already scheduled review of the MSR in the first years of phase 4,

A second ‘Nationally Determined Contribution’ to the Paris Agreement, which will need to be developed before the end of phase 4 as the current commitments only stretch to 2030,

Arrangements for Brexit.

The Legal Framework

The legal framework for the EU ETS in the UK is comprised of both domestic and EU legislation1. The EU ETS directive (2003/87/EC) was introduced by the European Commission and negotiated with the European Parliament and European Council, in accordance with established processes for the development of EU legislation2. It has since been augmented by further directives which have increased the scope of the scheme, for example the amendments for phase 3 (2009/29/EC)3.

Furthermore, European Commission Regulations cover many aspects of the system, these apply directly to member states without the need to transpose them into law. European Commission Regulations for EU ETS include1:

Monitoring, reporting and verification requirements,

International credit entitlements,

The establishment of the Union Registry,

Rules governing the auction of allowances.

Within the UK, emissions trading is a devolved matter, except where this relates to fiscal policy. The Climate Change Act (2008) identifies Scottish Ministers as the relevant authority with regard to administering emissions trading schemes in Scotland. Furthermore, emissions trading is not specifically reserved through the Scotland Acts5678. To provide consistency across the UK, Scottish Ministers have agreed to implement the EU ETS via UK-wide arrangements. Therefore, the UK regulations that transpose the relevant EU directives into law are made by the UK Government using powers under section 57 of the Scotland Act 1998, with the consent of Scottish Ministers9.

The EU ETS directive (2003/87/EC) was transposed into UK law through The Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading Scheme Regulations 200510. This was then extended to include the aviation directive (2008/101/EC11) through the 2010 Aviation Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading Scheme Regulations12. Finally, the amended EU ETS legislation for phase 3 (2009/29/EC) is transcribed into law through The Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading Scheme Regulations (2012)13. Together, these provide the legislative framework for the domestic implementation of the EU ETS14.

Regulators are government agencies and/or officials tasked with implementing EU ETS policy. Broadly, regulators in the UK are responsible for15:

Granting and maintaining the permits of EU ETS participants,

Managing emissions monitoring,

Assessing emissions reports,

Assessing applications to the new entrant reserve (NER),

Determining allocation reductions for installations as a result of capacity changes.

There are regulators for each of the constituent countries of the UK:

England - Environment Agency,

Northern Ireland - The Chief Inspector,

Scotland - Scottish Environment Protection Agency,

Wales - Natural Resources Wales.

Box 4 - The Climate Change Bill and the Net Scottish Carbon Account

The Climate Change (Emissions Reductions Targets) (Scotland) Bill was introduced in the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Government on 23rd May 2018. The Climate Change (Emissions Reductions Targets) (Scotland) Bill seeks to amend the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 by increasing the 2050 target from 80% to a 90% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, it allows for a "net-zero" target of a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions of 100% from the 1990 baseline16.

In order to meet these targets, the method by which the level of emissions is determined must be precise enough to accurately measure progress. Currently, Scottish emissions are accounted for using the Net Scottish Emissions Account (NSEA). This is calculated by17:

Separating verified emissions into traded emissions (i.e. emissions covered by the EU ETS) and non-traded emissions (i.e. not covered by the EU ETS),

The portion of verified emissions in traded sectors is then removed,

This is then replaced by Scotland's share of the overall EU ETS cap.

By accounting for emissions in this way, the final NSEA value does not reflect actual emissions from the traded sector (i.e. those under the EU ETS) in Scotland. The bill would replace this method of accounting (net emissions) with actual verified emissions from the traded sector (gross emissions). This will not affect EU ETS functioning in Scotland, merely change the way Scotland measures its performance against emissions targets.

The EU ETS and Brexit

This section will examine the impact of Brexit on the UK and Scotland's continued participation in the EU ETS. The range of options available post-Brexit will be discussed first, before outlining the UK and Scottish governments' positions

Post-Brexit Options

Although it is not yet confirmed what route the UK will take regarding carbon pricing after Brexit, there are a range of options available. These broadly fall into four categories, as outlined below. Further variations on these options are also possible, and are discussed in analysis conducted by Sandbag1 and the UK Emissions Trading Group2 (ETG).

1. Remaining in the EU ETS

In principle, the UK could choose to remain in the EU ETS and participate in phase 4 after Brexit, subject to agreement by the EU. This would be the most administratively straightforward option, although the details would depend on the overall Brexit deal. If the UK pursued this option it would have significantly diminished influence over the scheme, as the EU would continue to be responsible for developing legislation. It is also unknown whether the UK would continue to have access to the NER and innovation fund in this scenario31.

This option would be similar to the existing arrangement between the EEA countries (Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland), in which allowances continue to be issued under an agreement. One key distinction however, is that the EEA states are all part of the single market, and the EU may be unwilling to extend this arrangement to an external country31. While there are no examples of external countries adhering to the EU ETS, certain EU programmes are implemented by self-governing territories that are not within the EU, such as the Faeroe Islands and Greenland7.

2. Establishing a domestic ETS linked to the EU ETS

It would be possible for the UK Government and devolved administrations to establish a new domestic scheme and link it to the EU ETS. An example of this kind of linking is the Swiss ETS link to the EU ETS. Under this model, Switzerland will retain a separate system from the EU ETS, while enabling mutual recognition of allowances between the two. This was established to address concerns regarding the competitiveness of Swiss companies, which face higher costs under the Swiss ETS than EU counterparts8. Furthermore, in order to ensure its system is compatible with the EU ETS, the Swiss Government has ceded some regulatory control to Brussels9. The Swiss linkage could enter operation by the 1st January 202010.

In practice, a UK ETS linked to the EU scheme could afford more design flexibility, most notably in terms of allowance allocation, carbon leakage, and sectoral coverage. However, any divergences from the EU ETS may produce additional barriers to linking the schemes3. Furthermore, it should be noted that the Swiss linkage was negotiated from 2010 to 2016, before finally being signed in 2017, so any equivalent arrangement between the UK and EU post-Brexit may take years to negotiate121.

There would be significant costs associated with establishing a UK ETS, and the practicalities of doing so mean it will take time to set up. It is also possible that a hiatus in carbon trading would occur while the new mechanisms are established. Although, the experience of administering the previous UK ETS (2002-2006) may accelerate this process. The difficulties associated with establishing a domestic EU ETS was expanded upon by energy and climate lawyer Silke Goldberg, in evidence given to the House of Lords Energy and Environment Sub-Committee14:

To give you an idea of the length that is required, the EU ETS was first proposed at the end of the 1990s. It then took several years for the EU ETS to be designed at a policy level. The implementation, after the Directive had been adopted in 2003, started in 2005. There was this first trial period of two years, so we are talking about a seven-year period to get an instrument going, at least. I am not saying that it could not be done more quickly, and there might be efficiencies on the basis of experience. However, that ought to be taken into consideration when designing or looking at alternatives.

3. Establishing a domestic ETS, not linked to the EU ETS

Upon leaving the EU, the UK could establish a stand-alone UK ETS, unlinked to the EU ETS. This could be an opportunity to develop a single domestic carbon pricing policy to replace the various taxes and levies that operate in coordination with the EU ETS. As with the previous option, this would take time to establish, and there is the potential for a resulting hiatus in emissions trading8.

A stand-alone UK ETS would not benefit from the economy of scale associated with participation in the EU ETS or a linked UK ETS8. Due to the differences in size between an unlinked UK ETS and the EU ETS, the carbon price may be higher in the UK, thus increasing the risk of carbon leakage. The cost of meeting the UK's emissions reduction targets would therefore increase3.

There have also been concerns expressed by stakeholders such as the Grantham Institute on Climate Change, that a stand-alone ETS would have insufficient market liquidity18. This topic was recently addressed by Energy and Clean Growth Minister Claire Perry in evidence given to the House of Lords Energy and Environment Sub-Committee19:

It is under consideration, because it is a fallback option if we do not succeed in a negotiated outcome, along with other options which we would be happy to discuss. It is under consideration, and clearly there has been a lot of analysis to understand whether it would be viable, which it would be in terms of volumes and liquidity.

4. A broader UK carbon tax

The UK currently applies a carbon tax to the power sector, in the form of the carbon price floor (CPF), and this could be expanded to cover all industry post-Brexit. Extending a carbon tax over multiple additional sectors would require substantial changes to the regulatory framework. Furthermore, there is a significant risk of carbon leakage due to the differences in operating costs faced by competitors within the EU ETS, and due to the loss of free allocation for UK sectors3.

A carbon tax was recommended in the Cost of Energy Review in 201721. However, some commentators have pointed out that a carbon tax may be vulnerable to differing interpretation. In evidence given to the House of Lords Energy and environment Sub-Committee, Silke Goldberg stated14:

I would concur that taxation is inherently more susceptible to legal and political interpretation and changes. The EU ETS or a UK ETS might be more apt in providing longer trading periods and compliance periods.

UK and Scottish Government Positions

The Withdrawal Agreement forms the basis for the UK Government's post-Brexit carbon pricing policy. It states1:

The United Kingdom shall implement a system of carbon pricing of at least the same effectiveness and scope as that provided by Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 October 2003 establishing a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community.

While the accompanying Political Declaration offers more clarity on the form of carbon pricing being pursued by the UK government, describing a linked UK ETS. It states2:

The Parties should consider cooperation on carbon pricing by linking a United Kingdom national greenhouse gas emissions trading system with the Union's Emissions Trading System.

On 27th February 2019, Claire Perry, Minister of State for Energy and Clean Growth, reaffirmed the UK Government's preference for a UK ETS linked to the EU ETS. In evidence given to the House of Lords Energy and Environment Sub-Committee she said3:

The preferred option, which has been communicated clearly to industry in line with the political declaration, is a linked ETS that delivers, as far as possible, the benefits that have started to emerge. The movements in the carbon price are very striking now. It is quite clear that our preferred option and the fallback options will deliver on our Clean Growth Strategy commitments.

Later, when questioned about the difficulties associated with linking a domestic ETS to the EU ETS, Claire Perry said3

the EU wants us to be involved in this because we are an important part of the Scheme. We are a big provider, if you like, of liquidity to the Scheme, and we have a much larger market. […] There is a really strong political will to link. There is a blueprint, if you like, for one way of linking via the Swiss deal, but my sense is that we will be able to move faster and perhaps in a less constrained way towards a linkage.

In any case, a UK ETS would take time to establish, and Claire Perry indicated to the Energy and Environment Sub-Committee in March 2018 that the UK Government is seeking to continue to participate in the EU ETS until the end of phase 3 in December 20203.

UK Government Policy in a No-Deal Scenario

In the event that the UK has no deal in place by exit day, the UK will cease to be a part of the EU ETS. In this scenario the UK Government would suspend the requirement to surrender EU allowances, although installations would still be obliged to continue with monitoring, reporting and verification requirements6.

In a no-deal event, the UK Government will institute a Carbon Emissions Tax to help meet the UK's emissions reduction targets7. This tax is intended to simulate the EU ETS allowance price, and to provide continuity to businesses3. The Carbon Emissions Tax will be set at a rate of £16/tCO2, and will apply to emissions over and above an installation's emissions allowance – a value based on the level of free allocation it would have otherwise received under the EU ETS. The £16 rate was calculated ‘based on the prior six months and a forecast of the six months ahead’73.

The Carbon Emissions Tax would apply to all stationary installations currently participating in the EU ETS and will come into force on the 15th April (updated from 1st April due to the extension to the exit date granted by the EU). Aviation will not be included however, although the sector will be required to maintain monitoring, reporting and verification requirements.

Scottish Government Position

The Scottish Government has expressed a desire to remain in the EU ETS after Brexit. Giving evidence to the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee on the 24th October 2018, the Minister for Rural Affairs and the Natural Environment, Mairi Gougeon said11:

It would be our preference to remain part of the EU ETS because it is a bigger market for the trading of allowances. […] Failing that, a potential option could be a UK system that eventually links into the EU system, but we have seen some issues with that from other third-country examples. Switzerland took about seven years to negotiate its link into the EU system and make that work.

In the same session, commenting on UK Government plans for the no-deal Carbon Emissions Tax, Mairi Gougeon said11:

One of the issues that we have with the carbon tax is that it would take accountability away from the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament, because it would be entirely a reserved matter and we would not be involved or have a say in it.

On March 1st 2019, the Cabinet Secretary for Environment, Climate Change and Land reform, Roseanna Cunningham, and the Minister for Energy connectivity and the Islands, Paul Wheelhouse, published a summary of meetings between the UK Government and the Devolved Administrations on this subject. During the discussions, the Scottish Government outlined their opposition to a no-deal Carbon Emissions Tax, stating13:

We remain concerned, however that the UK Government has refused to rule out the option of a carbon tax as a long term alternative, in the event that it is not possible to conclude a UK ETS linking agreement with the EU. We remain concerned that the ‘No Deal’ carbon tax already provided for within the Finance Act 2019 (following the Scottish Parliament's scrutiny of the associated SI on emissions monitoring, reporting and verification last autumn), could then, de facto, become a permanent alternative.

[…]

We reiterated our opposition to any proposal to replace the ETS with a long term, reserved carbon tax, and the unacceptable incursion this would make on devolved competence.

In response to recommendations from the Committee on Climate Change in the stage 1 report of the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill, Cabinet Secretary for Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform, Roseanna Cunningham said14:

The Scottish Government continues to impress on the UK Government that it considers that remaining part of the EU ETS provides in the most cost effective route to decarbonisation and whilst supporting industry. However in the event that the UK cannot continue in the EU ETS following the UK's exit from the EU, the Scottish Government continues to engage with the UK Government on developing long term alternatives.

The UK Minister of State Claire Perry announced in her evidence to the House of Lords Select Committee on the EU on 27 February that a consultation on the long term alternatives would be published shortly (around April). She confirmed that the UK Government's preferred option was to create a UK ETS linked to the EU ETS, in line with the Political Declaration with the EU, which will be the focus of the consultation. It will also set out fall-back options in case a link cannot be agreed to link a UK ETS to the EU ETS by the end of the Implementation Period in 2020.

The Scottish Government has indicated that they would be willing to support a UK ETS linked to the EU ETS. This support was offered on the condition that equivalent funding be available to replace the UK's share of the Innovation Fund, so as to finance carbon capture and storage projects15.

Stakeholder Views

As of 20161 there were 72 EU ETS participants in Scotland, covering a range of sectors. The largest participating sectors included petrochemicals, cement, and the spirits sector. Of these, three key stakeholders were identified and consulted on their perspective on the policy, and their positions post-Brexit. In addition, we also approached relevant non-governmental organisations for their perspective. This section provides a summary of their views. These sections were compiled using notes from meetings held with SPICe, which have been verified with the relevant stakeholders, or from written submissions.

INEOS Grangemouth

INEOS and its constituent businesses are cumulatively, by a significant margin, the largest EU ETS participants in Scotland. INEOS’ Grangemouth is the site of Scotland’s only crude oil refinery and produces the majority of fuels used in Scotland. Furthermore, the Grangemouth site manufactures broad a range of petrochemicals. INEOS estimate that the Grangemouth site alone contributes 4% of Scotland’s GDP.

INEOS adhere to and report into to a wide range of overlapping climate and energy taxes and policy instruments, of which the EU ETS is only one. They consider the cumulative impact of these policies to be a significant burden, with over £700,000 spent per year on reporting requirements alone.

Recently, INEOS announced investment in new, more efficient combined heat and power (CHP) plant to provide steam and power to the INEOS petrochemical, Petroineos refining plants and INEOS crude oil terminal. They feel this is now the limit of technical feasibility for emissions reduction and expressed the view that there were no more-efficient alternatives to invest in.