Transitions of young people with service and care needs between child and adult services in Scotland

This briefing reviews evidence, policy and legislation relating to the transitions of young people with service and care needs from child to adult services in Scotland. It covers the areas of education, health and social care and explores how the transitions of young people are supported within these systems.

Executive Summary

Adolescence and young adulthood is a time of vast physiological, psychological, social and contextual changes. Young people with service and care needs during this period need to move from child to adult systems and those with complex needs may have to repeat this move across multiple services. This process is often referred to as "transitions."

Transitions are not synonymous with the transfer between child and adult services, but is a multi-dimensional concept. Transitions have been defined as an ongoing process of psychological, social and educational adaptation, which occurs over time, due to changes in context, interpersonal relationships and identity. This process can be both exciting and worrying and requires ongoing support. 1

Evidence suggests that this can be a difficult process for young people and their families. Barriers to successful transitions, reported in evidence, include lack of support from adult services, poor co-ordination between services, inadequate planning and confusion around who is responsible for planning, lack of information on available options, and young people's voices not being heard. Furthermore, support for transitions seems to vary considerably between local areas.

Policy reviews and research studies offer various recommendations to improve the transition process for young people. Recurring themes include the following:

Co-ordination and collaboration between services;

Person-centred focus, involving the young person and their parents in decision making;

Starting the transitions planning process early;

Young people and their parents having a single point of contact;

Increased information about available options;

More support for families;

Dedicated transitions staff; and

Appropriate training for staff.

Policies and legislation in the areas of education, health and social care reflect the above recommendations to some extent. However, recent evidence suggests that there still remain gaps between policy and practice in transitions between child and adult services.

Much of the available evidence, as well as policies, emphasise the value of the Scottish Government Getting It Right For Every Child (GIRFEC) approach and the Principles of Good Transitions, produced by ARC Scotland, in supporting young people's transitions to adulthood. Both encourage a person-centred approach to planning, co-ordination between those involved in supporting young people, listening to the voices of the young people, and proactive strategies to support planning.

Introduction

The period of adolescence and young adulthood is a time of considerable physiological, psychological, social and contextual changes for young people. These years are significant in laying the groundwork for future health and wellbeing, moving beyond compulsory schooling and into further education and employment, and the formation of significant relationships. During this period, young people are vulnerable to the risks of adverse outcomes in adult years such as physical and mental illness, substance abuse and risk taking behaviour. 1

Young people with service and care needs during adolescence and young adulthood need to move from child to adult systems, and those with complex needs may have to repeat this transition across multiple services. This period is often referred to as "transitions."

Transitions are not synonymous with the transfer to adult services, but is a multi-dimensional concept. Transitions have been defined as an ongoing process of psychological, social and educational adaptation, which occurs over time, due to changes in context, interpersonal relationships and identity. This process can be both exciting and worrying and requires ongoing support. 2 Evidence suggests that it is vital that young people's voices are heard when planning for transitions, to ensure that appropriate support is provided.

In this briefing, evidence, policy and legislation relating to the transitions of young people with service and care needs to adult services are explored. Services covered in this briefing include education, health and social services.

Transitions of young people with service and care needs is a complex issue. Needs of young people are wide ranging and require varying levels of support. Some young people may receive support from multiple services over the course of childhood. For these people, transitions to adult services need to be addressed by each service and appropriate support for the individuals within adult systems identified. An understanding of the different needs of young people is required to ensure successful transitions into adult services and adult life.

Evidence suggests that the absence of adequate transitional planning and collaboration between services can result in discontinuity of care, which in turn can lead to increased difficulties and strains on services, as well as risking the young person becoming "lost" or unable to navigate the system.

Service and care needs

For the purposes of this briefing, service and care needs are defined as needs for additional support for learning, needs arising because of a disability or health condition, due to a young person being or having been looked after or any other needs a young person may have to successfully transition into adult life.

The briefing does not cover transitions within the justice system as this is outwith the scope of this paper.

A pupil with additional support needs is defined in Section 1 of the Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004: 1

[...] where, for whatever reason, the child or young person is, or is likely to be, unable without the provision of additional support to benefit from school education provided or to be provided for the child or young person.

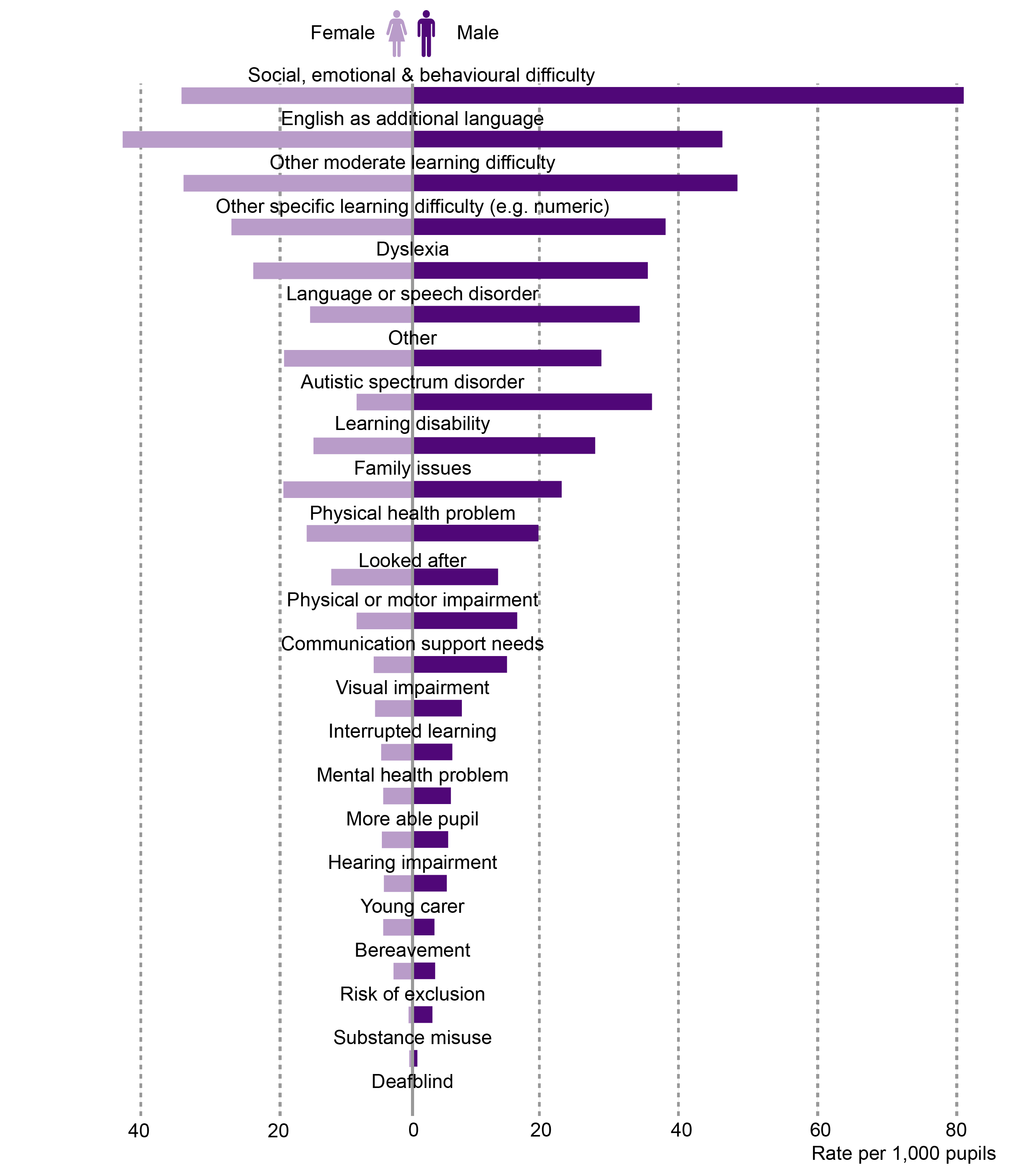

In 2018, 199,065 pupils in Scottish schools were identified by education authorities as having additional support needs. This number has increased markedly in the past decade, which is thought to be due to the definition of additional support needs becoming broader and to changes in recording processes. 2 Figure 1 shows the reasons for support for pupils defined as having additional support needs for the year 2017, by gender.

As Figure 1 shows, the reasons for support for additional support needs vary considerably. A young person being identified as having additional support needs in education does not necessarily mean they are in need of support from other authorities or services.

Evidence discussed in this briefing describes the experiences of young people with a wide spectrum of conditions, who face a range of different barriers and challenges during their transitions to adulthood. The evidence illuminates two groups of young people who have different needs and face different barriers to successful transitions. One group comprises young people with profound support needs, such as those with severe disabilities or life limiting conditions. Evidence suggests that the challenges these young people face during transitions include a lack of experience in adult services in how to deal with their conditions, differences between child and adult services in structure and approaches to care, poor collaboration between specialists in adult services and loss of support for parents and carers.

The other group is made up of young people with less severe or less "obvious" conditions. This group may have significant service and care needs that are not being recognised and, as a consequence, they do not receive the support they need. Evidence suggests that these young people are at risk of falling through the cracks during the transition to adulthood, because their needs are not considered severe enough to require support from adult services. They may be reluctant to seek out support themselves and miss out when available support is not signposted appropriately.

What does the evidence on transitions tell us?

Transitions can be a challenging time for young people. Research on transitions from paediatric to adult health care shows that feelings of not belonging, of being redundant and of needs not being appreciated by health care professionals are common during this period. 1 A study using English hospital data showed that young people with longstanding illnesses experienced increased rates of emergency admission and longer periods of stay in hospital during the period of transition between paediatric and adult care. The findings also showed that young people from more deprived areas were more likely than others to have an emergency admission to hospital. 2

While transitions can be a difficult time for young people, this can also be the case for the people around them. Studies show that during transitions of young people with various health conditions into adulthood, the health and wellbeing of all family members, 3 and even professionals involved in the young people's care, 4 may be at risk.

A recently published study explored the transitions of young adults with life-limiting conditions, and their nominated significant others (family members and involved professionals), over time in Scotland. 4 The study found that the young adults experienced multiple health, educational, social and developmental transitions, which interacted with each other and with those of the young people's significant others. Specific to the move from child to adult services, the study participants were faced with significant barriers to receiving adequate support (pseudonyms were used in the paper):

… Children's Services were great… anything Susan needed as a child, there wasn't a huge fight behind it… the minute she becomes an adult it's a problem…I think in Children's Services they understand that, that you know your child better than anyone…especially when there's communication problems

Susan's parent (p. 7)

Professionals also described difficulties in adaptation relating to the young people's move from child to adult services:

… we have to treat him as an adult…that's quite difficult I think for him, because we'll say no… I don't see that as reasonable, that's going to impact on your clinical care… we maybe need tae consider if he's refusing medication and it's causing him clinical issues, we need to take these things on-board ‘cause it's quite a complex package …

Health Care lead (p. 7)

The authors argued that transitions from child to adult services should be based on young people's developmental stage, rather than their biological age. They further argued that services should focus on the young people as a whole, providing medical, psychosocial and educational support both for them and their families. Lastly, it was emphasised that family members and professionals needed appropriate training and support in order to help young people during transitions, as well as manage their own related transitions. 4

Subsequent sections of this briefing provide an overview of the evidence and recommendations from a number of studies relevant to transitions of young people with service and care needs in Scotland. Related policies and legislation are also considered. Similar recommendations have been consistently highlighted in evidence for the past several years. While many of these recommendations have, to some extent, been reflected in policy and legislation, the recurrence of the same themes suggests that these recommendations may not always result in better practice. Among the recurring recommendations were the need for:

Co-ordination and collaboration between services;

A person-centred focus, involving the young person and their parents in decision making;

Starting the transitions planning process early;

Young people and their parents having a single point of contact;

Increased information about available options;

More support for families;

Dedicated transitions staff; and

Appropriate training for staff.

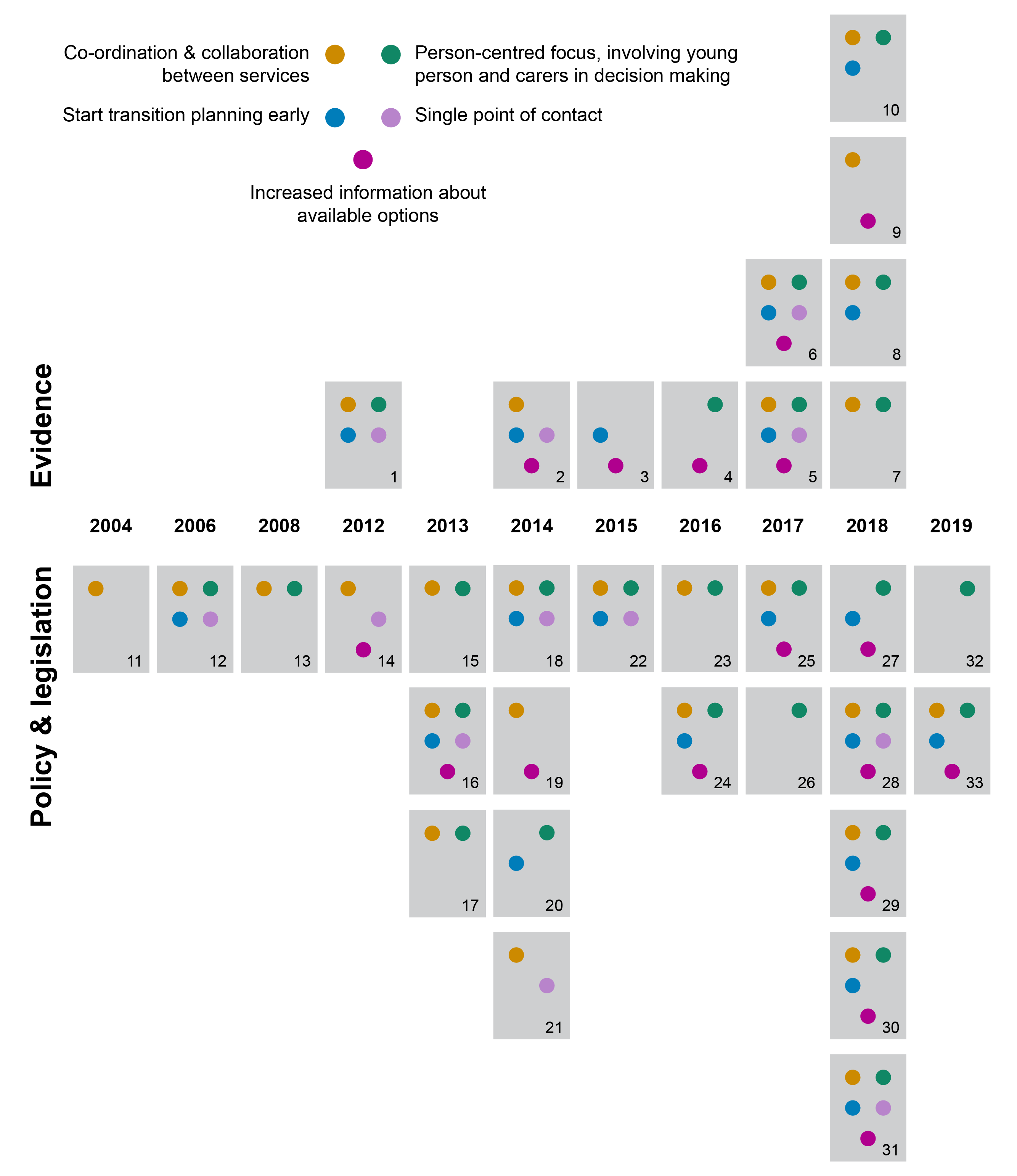

Figure 2 helps to illustrate how five of these themes have consistently emerged in a range of studies, policy papers and in legislation over the last 15 years.

As Figure 2 shows, the five themes recur in recommendations, policy actions and legislation. The Getting It Right For Every Child (GIRFEC) approach and Principles of Good Transitions were referred to in many publications. GIRFEC is the Scottish Government's overarching approach to improving outcomes for children and young people and ensuring that they receive the right help, at the right time, from the right people. The Principles of Good Transitions is a product of ARC Scotland, aiming to provide a framework to inform, structure and encourage the continual improvement of support for young people with additional support needs who are making the transition to young adult life. Both the GIRFEC approach and the Principles of Good Transitions embrace the above mentioned themes, among others, for the provision of support for young people.

Education and learning

Doran Review

In 2010, the Scottish Government commissioned a strategic review of learning provisions for children and young people with complex additional support needs, referred to as the Doran Review. The final report, The Right Help at the Right Time in the Right Place: Strategic Review of Learning Provision for Children and Young People with Complex Additional Support Needs, 1 was published in November 2012. The report highlighted major challenges young people and their carers faced during the transition into adulthood and found that parents were deeply concerned about their children's transitions and the loss of support from services. Parents expressed a fear of their children "falling into a 'black hole' where there was no direct accountability for continuing services." (p. 29) Some parents were considering giving up paid employment in order to take care of their child. The report offered the following recommendations, aimed at the Scottish Government on the topic of transitions:

Recommendation 11:

The Scottish Government should provide leadership and where appropriate direction to local authorities and health boards and consider the adequacy of existing legislation to ensure that the transition from children's to adult services for young people with complex additional support needs is properly coordinated, managed and delivered.

(p. 30)

Recommendation 15:

The Scottish Government working with local authority services, the health boards and the voluntary sector should provide detailed guidance and support for the application of the GIRFEC approach and specifically the practice model to meeting the changing needs of all children and young people and specifically those with complex additional support needs from the earliest stages to transition to adult life.

(p. 37)

In the same month as the publication of the final report, the Scottish Government published a response to the Doran Review 2, where recommendations 11 and 15 were accepted and plans to deliver them set out.

Response to recommendation 11:

We recognise the need to support improved practice in implementing transition duties. Stakeholders consistently express concern in relation to practice in transitions across children and young people's learning experiences, but particularly in relation to post-school transition. The 2012 Report to Parliament on Additional Support for Learning highlighted the issues in relation to transitional arrangements. Transitions will be the theme of the 2014 report to Parliament. Transitional arrangements were also highlighted by the Advisory Group for Additional Support for Learning as an area where practice could be improved. A subgroup of the Advisory Group will consider this issue in 2013 and make recommendations. This will include consideration of whether the current legislative framework is appropriate and will therefore inform the actions to deliver this recommendation.

(p. 12)

Response to recommendation 15:

There are two principal actions which will deliver this recommendation and these are detailed under the response to recommendation 13. These are the practice guidance that will be associated with the Children and Young People's Bill, and the revision of the code of practice for additional support for learning. In addition the Advisory Group for Additional Support for Learning will continue to consider the need for any additional Guidance as part of their ongoing work programme.

(p. 14)

Impact of the Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2014 on transition practice

A research study from 2017 1 examined post-school transition practice for young people with additional support needs before and after the implementation of the Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004 (2004 Act). The study included interviews with professionals involved in post-school transition planning in the years 2004 (before implementation of the 2004 Act) and 2010 (after implementation) in one local authority in Scotland. Minutes from transition meetings were also analysed.

The findings showed that collaboration between professionals was perceived to have improved since the implementation of the 2004 Act. Furthermore, young people seemed to have participated to a greater extent in transition planning, by attending meetings and getting more opportunities to express their views and wishes. The number of formal meetings was lower in the post-implementation period than before, but more informal interactions between professionals and young people and their parents seemed to have occurred. The authors emphasised that the perspectives of young people and their parents would be needed to gain a greater understanding of the situation.

Facing the Future Together

In July 2017, ARC Scotland published Facing the Future Together, 1 a report describing findings from two national surveys on post-school transitions of young people with additional support needs. One survey focused on the experiences of the young people themselves and the other on the experiences of parents and carers. The surveys covered the periods before, during and after transitions.

Findings from the young people's survey showed that most of them were optimistic about the future and excited about taking control of their own lives. However, many worried about potential lack of support and changes in routine:

I don't want to be sitting at home until adult services decide it's time to help out, my friend was 12 weeks b4 a programme was put in place. My mum has contacted adult services but she was told they were unable to help us out in any way until I had actually left school

(p. 14)

The parents and carers' survey findings showed that 90% of parents and carers of young people still at school said the young person did not have an agreed, written down plan to support their transitions, or were unaware of such a plan being in place. Further, 63% said the young person they cared for were not receiving any support:

Absolutely none from education. He does not meet the critical needs for social work intervention, health no longer have any involvement and careers have never contacted us, despite school being aware that he has a diagnosis. There seems to be a belief that this will be managed by family.

(p. 34)

Nothing so far, I am resourceful and will find my way but accessing services is difficult as there seems to be a lack of knowledge of what is available and who qualifies. There needs to be more advertising on local radio or leaflets at the GP's. I would like to see a HUB of some kind in each town or city that offers advice on all different mental health/disabilities/issues.

(p. 34)

The report noted that 25% of parents and carers of young people who had already left school mentioned that the lack of support and information had been the most difficult thing for their child in the school leaving process:

Transition to college was badly organised and woefully inadequate for an ASD specific course. Lack of information for parents and students- and no meetings prior to enrolment. Interview process for course also badly organised with all applicants being asked to attend at the same time and then having to wait to be seen.

(p. 44)

The report concludes with a summary of elements that parents and carers agreed would improve the process of transitions:

Starting the person-centred planning process early;

Honest communication about the available options;

Opportunities for the young person to try out college or work;

Effective communication and co-ordination of services (especially between child and adult services);

Building young people's confidence and life-skills by listening to them and involving them;

A single consistent point of professional contact; and

Staff training in line with young people's needs.

Young people's experience of education and training from age 15 to 24

In 2016, the Scottish Government commissioned SQW, in partnership with Young Scot, to carry out a research study on young people's experiences of the education and skills system. The report, Young people's experience of education and training from 15-24 years, 1 was published in September 2017.

A review of existing literature showed that young people with additional support needs required extensive and tailored support in order to make successful transitions. Care-experienced young people were more likely than others to have poor outcomes from the education and learning systems and most lacked confidence when making post-school transitions.

Several young people taking part in the study workshops said that they would have liked more time to make subject choices for post-school education, as well as information and guidance in the implications of their choices, for example, on which jobs would be available to them if they chose a certain subject. This was particularly evident among young people suffering from anxiety or other mental health conditions.

In May 2018, the Scottish Government published the 15-24 Learner Journey Review, 2 where they responded to the study findings with plans for improvement. The review lists five key priorities, as follows:

Information, advice & support. Making it easier for young people to understand their learning and career choices at the earliest stage and providing long-term person-centred support for the young people who need this most.

Provision. Broadening our approach to education to reframe our offer, doing more for those who get the least out of the system and ensuring all young people access the high level work-based skills Scotland's economy needs.

Alignment. Making the best use of our four year degree to give greater flexibility for more learners to move from S5 to year one of a degree, more from S6 to year 2 and more from college into years 2 and 3 of a degree where appropriate.

Leadership. Building collective leadership across the education and skills system.

Performance. Knowing how well our education and skills system is performing.

Life on the Edge of the Cliff - Lessons from Europe

In 2016, Tracey Francis, a freelance writer and researcher, published the report, Life on the Edge of the Cliff, Post school experiences of young people with Asperger's Syndrome, ADHD and Tourette's Syndrome. 1 The report describes findings from a study conducted in Norway, Italy and the Czech Republic on the topic of post-school transitions of young people with Asperger's Syndrome, ADHD and Tourette's Syndrome.

These countries were selected because of their shared legislative commitment to social inclusion for people with neurological or psychological disabilities, but different approaches to delivering this [...]

(p. 7)

Young people affected by the conditions and their families were interviewed for the study, as well as practitioners and service providers in health, education and social services.

The findings highlight the challenges these young people faced during post-school transitions. In particular, the report stresses that misunderstanding about the impact of Aperger's Syndrome, ADHD and Tourette's Syndrome can lead to missed opportunities when services and support agencies do not recognise the challenges and barriers these young people face in transitioning into adulthood.

The report made four recommendations, aimed at improving transitions for young people with these conditions:

There should be greater access to specialist life coaching and planning;

Preventing isolation needs to be an explicit aim for all services and support structures;

Greater focus is needed on addressing the mental health care needs associated with this group; and

There is a need for more effective joint working with parents and families.

Health and Social Care

Will anyone listen to us?

In October 2015, the report, Will anyone listen to us? What matters to young people with complex and exceptional health needs and their families during health transitions, 1 commissioned by the National Managed Clinical Network for Children with Exceptional Healthcare Needs, was published. The report summarises the experiences of a small group of young people with complex health needs and their parents of the transition from paediatric to adult care. It highlights multiple issues and challenges the participants faced during the transition between the two systems.

Some study respondents reported positive experiences where transition nurses were involved at the start of the process, including setting up joint meetings with adult services.

Last time I had a transition care nurse and that was so helpful. She stopped everyone and said ‘speak one at a time, write it down. How do you feel about that K.? Would that work in your home environment?’ It was just awesome - someone outwith the family that knows us both.

(p. 12)

However, the level of support from the adult care side was found to be insufficient in many instances. Representatives from adult services did not always attend the transition meetings and many of the participants reported a lack of understanding of the young people's conditions and the kind of support they required.

Some parents talked about a distinct change from paediatric to adult services. They signalled that staff in paediatric hospitals had sufficient training and experience in working with complex needs, whereas this expertise was entirely lacking within adult services. Parents felt that they were not listened to, and that their knowledge about their children's needs was not taken into account by adult services.

The report includes a case study which highlights serious problems with transition support:

A young woman was unexpectedly admitted to an adult Accident & Emergency ward, the reason being she had recently turned 17 years old. The staff had no information about her condition or how to provide the appropriate care. She was left in the ward for 14 hours without receiving care. Unlike what the young woman was used to in the children's ward, there were no facilities for her mother to stay with her. When the mother returned to the hospital after leaving to get necessary things, she found her daughter in distress as she had been left alone, she had not received any personal care and the doctors seemed completely unfit to treat her. (See full case study on p. 8 of the report)

The report concludes with recommendations for improvement, suggested by the families who took part in the study. The recommendations were that there is a need for:

Courses for parents on transitions;

More specialist nurses, for example, transition nurses and acute liaison learning disability nurses;

Preparations to start early - at least 2 years;

Transition wards for young people;

Training for doctors and nurses about complex needs;

More respite;

Emotional support for parents;

Longer appointment times; and

A hotline to GPs.

Experiences of Transitions to Adult Years and Adult Services

In May 2017, the Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland carried out the Experiences of Transitions to Adult Years and Adult Services 1 study, commissioned by the Scottish Government. The study consists of responses from 29 young individuals with complex disabilities, and their families and carers. The aim of the study was to highlight areas for improvement in transitions from child to adult services. Furthermore, the study sought to explore how the Getting It Right For Every Child (GIRFEC) National Practice Model 2 had value for young people and their families during transitions. The report also took into account the perspectives of professionals in various statutory and third sector services.

The report highlights themes of "cliffs" and "bridges", representing negative and positive factors relating to transitions.

Frequently reported cliffs:

Parents managing transition planning instead of a lead professional;

Parents having to give up work or negotiate flexible working hours with their employers in order to care for their young person;

Fear around loss of paediatric services and practitioners who know the young person and their family well;

Lack of understanding and appropriate expertise in adult services;

Lack of information about available services, funding options and guardianship

Reductions in funding for respite services;

Young person's needs not appropriately taken into account in post-school options offered by local authorities;

Delay of assessments and/or diagnoses and consequently of appropriate support

Lack of communication between different services; and

Transition meetings not resulting in practical planning and actions.

Frequently reported bridges:

Stable, supportive and affectionate family relationships;

Young people's nature and positive outlook;

Support provided by dedicated transitions workers;

Good experiences of support in paediatric services;

Positive experiences of local day services;

Support and information from other parents; and

Support from third sector advocacy services.

The report stresses the need to build on the strengths of a young person and to recognise the risks and challenges they face, as well as considering the ecology of their relationships. This refers to the relationships between an individual, their family, significant others and their wider environment and how these interact, evolve and affect individual resilience, development and transitions. In relation to this, it is argued that families and carers should be supported within the context of contributing to successful transitions.

The report highlighted elements of effective transitional support and based the following recommendations on those:

Wellbeing: Use of the Wellbeing Indicators to support transitional planning.

Principles of Good Transitions: These should be a standard approach across all services.

Information: Improved access to information on local resources available.

Training: Pre-qualifying and cross-service training for professionals involved in transitions of young people.

Outreach: Scottish Government, local authorities and health boards should reach out to young people with additional support needs and who may be at risk, as well as those who are not known to services, but who may become isolated and exhausted without proactive support.

Coordination and Point of Contact: Local authorities and other statutory services should ensure families' access to a lead professional who co-ordinates communication and support across services, statutory and third sector, between ages 14 and 21.

Structures: Relevant service providers should evaluate and learn from structural changes within other services which are planning on continuing support for young people until age 26.

Planning and Partnership: Scottish Government and statutory partners should consider developing a Family Group Decision Making model of transition planning where the young person, their family members and all service providers work together.

Resourcing: Local authorities should consider how respite or short break arrangements are cut when a young person turns 17, where this is not in line with the young person's needs.

Integrating Health and Social Care in Scotland: The Impact on Children's Services

In June 2018, Social Work Scotland published the literature and policy review, Integrating Health and Social Care in Scotland: The Impact on Children's Services, 1 following up on the implementation of the Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014. The report is based on research conducted by Children in Scotland in partnership with the Centre of Excellence for Looked After Children in Scotland (CELCIS).

Findings showed there to be overall agreement, among both service users and professionals, that multi-professional and inter-agency collaboration was positive and helpful. However, the report highlighted some barriers to making this part of day-to-day practice. These included:

Inadequate resourcing;

Poor inter-agency communication;

Lack of understanding between professionals; and

Data sharing issues.

Furthermore, the findings showed that service providers did not take the voices of children and young people as seriously as those of adult patients. Research with care-experienced young people suggested that services were disjointed and not enough attention was paid to transition points. The report emphasised the need for collaboration between professionals in order to increase co-ordination of services.

When the report was published, 19 integration authorities had chosen to integrate some children services. At the time of writing, this is still the case. 2 When examining effects on children's services, the report found no direct links between integration arrangements and strength of local services for children and young people. Rather, it seemed to be the strength of strategic leadership that had the most impact on outcomes.

Care Experienced Young People's Views: Interpreting the Children and Young People Act 2014

In November 2014, Who Cares? Scotland published the report, Care Experienced Young People's Views: Interpreting the Children and Young People Act 2014. 1 This report included a consultation with 87 young people on their experiences of living in care, their hopes for life after care and the types of support needed to achieve this.

When the young people were asked at what age they would like to leave care, many responded that age did not matter, as long as they felt ready. When asked where they would like to live after leaving care, many of the young people responded that they had neither thought about where they would like to live nor in what kind of accommodation. Those who had left care stressed that conversations about future living arrangements should occur early and often.

The authors of the report stressed that good relationships with trusted, adult professionals were vital for a positive transition out of care. When asked whether they felt listened to during discussions about their future, less than half of the young people reported that they had.

The report set out the following recommendations relating to Parts 5 (Child's Plan), 10 (Aftercare) and 11 (Continuing Care) of the Children and Young People Act 2014:

Discussions about the future must happen early and often for ALL young people living in various care placements. This will help them to feel more prepared when moving on from care.

These discussions must be led by adults who have built a positive and trusted relationship with the young person.

All involved with the care of the young person, must take a coordinated and collaborative approach to meaningfully discuss life after care with them.

Young people need to know what their options are for life after care. This will help them plan and work towards future goals with support from those who care for them.

Long term, stable relationships must be around young people both during and after care.

Continuing Care, Continuing Concerns

In December 2018, Who Cares? Scotland published the report Continuing Care, Continuing Concerns, 1 describing the experiences of advocacy workers of the implementation of Continuing Care, introduced in the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014. The advocacy workers reported that young people had experienced lack of clarity, and in some instances inaccurate information, from professionals around eligibility age, the age that continuing care should end and appropriate continuing care placements. They also witnessed professionals practising strict applications of the legislation, without taking account of the Staying Put Scotland guidance.

The report quoted a care experienced young person, responding to a question on what is needed to support care leavers:

Proper funding and investment, into throughcare, post-care placement services. It's like okay you're out your placement now you're not really our problem? We'll find time and money for you, if we can, but you're not a priority anymore when in fact that's the demographic that's at most risk I'd say. They're the ones that are suddenly exposed to so many other dangers cause you're not living in a supervised environment, like there just needs to be an appreciation that these are the people that need those emergency services, need the back-up plans, it needs to be in place and it can't just be done on a when they need it scenario, cause when they need it – it's too late.

(p. 2)

Post-transition period

As the evidence considered in this briefing suggests, lack of transition planning and of co-ordination between child and adult services can lead to insufficient support in adult years. The report discussed in the following section highlights a lack of appropriate support for adults with complex needs at a local level. In the report, it is argued that the planning of support for individuals with complex care needs should start in childhood, in order to ensure appropriate provisions and support through the period of transitions and into adulthood.

Coming Home

In November 2018, the Scottish Government published the report Coming Home: A Report on Out-of-Area Placements and Delayed Discharge for People with Learning Disabilities and Complex Needs. 1 The report highlighted difficulties that adults with learning disabilities and complex needs experienced due to lack of local specialist services, resulting in the adults being placed far away from their homes and families, or hospitalised in order to receive appropriate support and care.

Many of the individuals included in the report were described as having "challenging behaviour", defined as behaviour which challenges services and support providers, rather than implying that the people themselves are challenging.

It is worth emphasising that challenging behaviour is understood as a communication from the individual and as product of the environment they live in and of the support they receive. It is not a diagnosis, and although it is associated with certain conditions and syndromes, it is not innate to the individual, but rather an expression of their unmet need.

(p. 46)

Challenging behaviour was reported as being a frequent reason for service breakdown, hospitalisation and/or out-of-area placements.

In the report, it is emphasised that, in order to meet the needs of these individuals, a long-term, proactive approach should be adopted in planning and commissioning support. The following was among the report's recommendations:

Recommendation 4:

Take a more proactive approach to planning and commissioning services. This should include working with children's services and transitions teams; the use of co-production and person-centred approaches to commissioning; and [Health and Social Care Partnerships] working together to jointly commission services.

(p. 65)

Others have criticized the lack of specialist residential services for people with disabilities in Scotland. Since 2014, a mother of a young adult with high support needs has had an open petition calling for the Scottish Government to provide local authorities with resources to establish residential care options for children, young people and adults with severe disabilities in Scotland. In her latest submission to the Petitions Committee (January 2019) the petitioner quotes the submission of Professor Sally-Ann Cooper to the Committee in 2015. There, it was stressed that local authorities should be able to provide people with learning disabilities a range of support options to choose from. The petitioner argues that this choice does not exist in Scotland.

Recent research from the University of Edinburgh further shows that even when there are different services operating in local areas, some may be full to capacity or allocated funding may only fully cover some of the services. The authors argue that this leaves young people and families looking for suitable support with a lack of real options, as their choices are inherently linked to what is available. 2

Staff shortages in social care are relevant to these issues as these affect availability of options and quality of care. A joint report from the Care Inspectorate and the Scottish Social Services Council shows high vacancy rates in care services in Scotland. 3

Local strategies for transition support

Leading the change: Solving the Transitions Puzzle

In October 2018, ARC Scotland led a seminar "Leading the change: Solving the Transitions Puzzle." The seminar brought together representatives from 19 Scottish local authorities, the Scottish Government, Social Work Scotland, the Association of Directors of Education in Scotland, and the Independent Living Fund, to discuss transition support for young people with additional support needs.

One of the concerns that the seminar report 1 highlighted was that strategic approaches to transition planning varied greatly by local authority.

Seminar participants reported that strategic drivers such as GIRFEC, Developing the Young Workforce, and Curriculum for Excellence had influenced the development of local approaches. However, there were mixed views on how effective the current legislation and policy drivers were in supporting strategic transition planning approaches.

Challenges identified by the seminar participants included:

Approaches not being strategic and/or co-ordinated enough;

Lack of involvement of young people and their carers;

Lack of alignment between child and adult services;

Budget constraints leading the planning process; and

Insufficient methods for measuring the effectiveness of transitions.

In response to the question of how strategic planning approaches could be improved, the participants identified the need for:

A dedicated staff resource to co-ordinate policy and practice in each local authority;

Improved collaboration between child and adult services, including developing a shared eligibility criteria;

Increased involvement of young people, their carers and third sector partners;

The development of clear and co-ordinated transition pathways, emphasising early interventions; and

A nationally agreed framework to measure effectiveness of transitions.

The seminar report concludes with three recommendations for what participants saw as the most important next steps:

Developing a nationally agreed non-mandatory framework for transitions;

Reviewing current approaches to data gathering and evaluation; and

Continuing to work together to develop solutions, share knowledge and resources.

ARC Scotland will lead in taking these recommendations forward. A second seminar is scheduled for June 2019 where delivery of the recommendations will be reviewed.

Case study

Transition support in Edinburgh

In December 2018, Edinburgh Integration Joint Board published the report, Transitions for Young People with a disability from children's services to adult services: Edinburgh Health and Social Care partnership. 1 The report is a response to feedback from young people and their parents, who described their experience of the transition process as "complex and frustrating." The report lays out five actions, based on the Principles of Good Transitions, aimed at improving the transition process:

A single point of contact. A professional worker taking responsibility for all planning.

Starting transitions work earlier. Starting at 14 years and continuing to 25 years.

Information for young people and their families. Easy to read versions of guidance on all aspects of transitions.

Provide accommodation options. Work with housing and care services to avoid out-of-area placements.

Communication approaches. Moving towards a more person-centred approach focused on what young people want and need and away from a service-centred approach with young people as passive recipients.

Further information on transition support within Edinburgh can be found on the City of Edinburgh Council website and on the Scottish Transitions Forum website.

Policy context

Principles of Good Transitions

In January 2017, ARC Scotland, on behalf of the Scottish Transitions Forum, published the Principles of Good Transitions 3. 1 The purpose of the seven principles are to inform, structure and encourage continual improvement of support for transitions of young people with additional support needs into adulthood. They are meant to guide professionals in all sectors involved in providing transition support for young people. The principles have been endorsed by the Scottish Government in various strategies and publications, such as, A Fairer Scotland for Disabled People, 23 Supporting Disabled Children, Young People and their Families, 4 The Keys to Life, 56 and The Scottish Strategy for Autism. 7 The principles have also been endorsed by a number of relevant Scottish organisations.

The Principles of Good Transitions 3 dedicates one chapter to each principle with each containing information on how the principle maps onto legislation, policy and practice. The principles are as follows:

1. Planning and decision making should be carried out in a person-centred way

Young people should be at the centre of their transition planning

A shared understanding and commitment to person-centred approaches across all services

Young people should have a single plan

2. Support should be co-ordinated across all services

There should be a co-ordinated approach to transitions in each local authority

Learning and development opportunities should include an understanding of all aspects of transitions

Transitions should be evaluated

3. Planning should start early and continue up to age 25

Planning should be available from age 14 and be proportionate to need

Children's plans and assessments should be adopted by adult services

Transitions planning and support should continue to age 25

4. All young people should get the support they need

Eligibility criteria should be applied equitably across Scotland

Support should be available for those who do not meet eligibility criteria

An improved understanding of the number of young people who require support and levels of unmet need

Planning and decision-making for services should be done in partnership with young people and their carers

5. Young people, parents and carers must have access to the information they need

Information should:

Clearly state what people are entitled to during transitions

Show what support is available

Be inclusive of different communication needs

Use common and agreed language

6. Families and carers need support

Family wellbeing needs to be supported

Advocacy should be available at the start and throughout transitions

7. A continued focus on transitions across Scotland

The Scottish Transition Forum working collectively to promote the Principles of Good Transitions and improve practice across Scotland

A continued focus on transitions within policy and legislative developments

Learning good practice from project-funded work and embedding this into sustainable longer-term strategies

Getting It Right For Every Child

As research shows, transitions can be a challenging time for many young people and consequently pose a risk to their wellbeing. Getting It Right For Every Child (GIRFEC) is the Scottish Government's overarching approach which aims to support families "by making sure children and young people can receive the right help, at the right time, from the right people." 1 The GIRFEC approach introduces wellbeing indicators, which are intended to help children and young people, their families and anyone working with them, discuss how a child is doing and to determine whether they are in need of support.

Named person and child's plan

A key part of the GIRFEC approach is the named person service. This provides a point of contact for a child and their parents. The named person is responsible for assisting them in getting the support they need when they need it. The service is available to all children and their parents from birth to the age of 18 years, or beyond if still in school. The named person is someone who already provides advice and support to families and will change in relation to the child's educational stage: 1

Birth to school age: Health visitor

Primary school: Head teacher or deputy

Secondary school: Head teacher, deputy or guidance teacher

In the Principles of Good Transitions, it is argued that the named person could be well placed to begin the process of transition planning, including making sure all appropriate agencies are involved.

Another tool which plays a large role in the GIRFEC approach, is the child's plan, a personalised plan for children who require additional support. It outlines what should improve for the child, the kind of support involved and how it will be delivered. Once a child's plan has been established, a lead professional should manage the plan and make sure it is co-ordinated. The lead professional is someone with the appropriate skills and experience to properly manage the plan and support the young person. Depending on the situation and the child's needs, the lead professional may also be their named person. 1

In the Experiences of Transitions into Adult Years and Adult Services, it is argued that the availability of a lead professional to co-ordinate services for families during the transitional years (at least between 14 and 21) would improve the experiences of transitions considerably.

The named person service and child's plan are defined in Parts 4 and 5 of the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014. As of yet, Parts 4 and 5 have not come into force, due to a judgement by the Supreme Court on changes to information sharing provisions in Part 4 of the Act. 3 Following this, on 19 June 2017, the Children and Young People (Information Sharing) (Scotland) Bill was introduced in the Scottish Parliament. The Bill seeks to change the information sharing provisions between the named person and other organisations, as well as duties to cooperate in relation to the child's plan with regards to information sharing. At the time of writing, the Bill is at Stage 1. For further information about the Bill, see SPICe Briefing. 4

Regardless of this, the named person service and child's plan have been implemented as policy, and local authorities may and do provide these services on a non-statutory basis. However, everyone who processes data must handle personal information in line with existing laws and guidance on data protection, confidentiality and human rights. This has not changed. 5

Post-school transitions

Co-ordinated support plan

The co-ordinated support plan (CSP) is a tool for education authorities to ensure provision of services for children and young people who:

Have significant additional support needs arising from one or more complex factors or multiple factors;

Are likely to require support for more than a year; and

Require support from local services other than education and/or one or more appropriate agency/agencies.

CSPs are mandatory when the criteria are met, and there are legal remedies where authorities do not fulfil this obligation. 1 The CSP is defined in the Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004, and is the only educational plan with legal force.

The proportion of pupils with a CSP is low, with only 1.2% of pupils defined as having additional support needs registered with such a plan in 2017. 2 This number has been consistently decreasing over the past few years, whereas pupils with the non-statutory child's plan have increased in number. 245678

Recommendation 13 laid out in the final report of the Doran Review, 9 published in 2012, emphasised the need for a single plan for each person:

In taking forward the development of the single plan as proposed in the Children and Young People Bill future legislation should specify the responsibility and accountability of all agencies to implement the actions and resources needed to fulfil that plan.

(p. 37)

The Scottish Government accepted this recommendation and responded as follows: 10

The provisions of the Children and Young People Bill and the associated practice guidance will set out roles and responsibilities for partners delivering services to children and young people. As part of the guidance there is a need to ensure that the relationship between the single Child's Plan and the co-ordinated support plan (CSP) is clear and understood by practitioners. In addition, the code of practice for additional support for learning will provide guidance on the relationship between the frameworks and the complementary roles of CSP coordinator and Lead Professional and the relationship between the statutory plans that children and young people with complex or multiple additional support needs may have.

(p. 13)

On 27 February 2019, the Scottish Parliament Education and Skills Committee heard evidence on additional support needs in school education. In the meeting, 11 May Dunsmuir, President of the Health and Education Chamber of the First-tier Tribunal for Scotland, stated that there seemed to be some confusion around CSPs at a local level:

From the tribunal's experience, it would appear that, quite simply, not enough people in education understand what a CSP is. They are unaware that, when the criteria are met, there is an obligation to provide a CSP. I speak to people from a wide range of education authorities, and the majority believe that they have a choice.

(p. 6)

I have looked at two recent cases in which the CSP request was refused—one on the basis that the child's plan was adequate and the another on the basis that a different type of local plan was meeting the child's needs. In both those cases, if the criteria for the CSP were met, the education authorities would have no choice but to provide a CSP. When I convey that point to an audience of educationalists, I see the colour of faces change from a nice rosy pink to a pale white.

(p. 7)

In the Principles of Good Transitions, it is argued that the child's plan and CSP should be combined into a single plan. This would reduce the amount of administration, number of processes for young people and families to understand, and occasions they have to repeat their stories to different professionals. It is argued that this would further contribute to a person-centred approach to transition planning.

Other instruments used by education authorities to plan for additional support provisions include Personal Learning Plans (PLP), Individual Educational Programmes (IEP) and staged interventions. Which plans schools use vary by local authority. 12

Supporting Implementation of Additional Support for Learning

In November 2012, the Scottish Government published Supporting Implementation of Additional Support for Learning in Scotland. 1 This document lays out actions for improved support for post-school transitions of young people with additional support needs. These actions include:

Providing parents with information on roles, responsibilities and examples of good practice in transition planning;

Creating a practice framework for practitioners supporting young people; and

Providing support for employability and career management programmes for young people with additional support needs.

Opportunities For All - Post-16 transitions

In August 2014, the Scottish Government published, Opportunities For All - Post-16 transitions - Policy and Practice Framework: Supporting all young people to participate in post-16 learning, training or work. 1 The Framework is intended for everyone who has a role in supporting young people aged 16-19 years to participate in post-16 learning, training and employment. It incorporates strategies laid out in the Curriculum for Excellence and Opportunities for All. 2

The Framework emphasises that particular attention should be paid to pupils with additional support needs, as they may be presented with barriers to learning and employment. For those with a child's plan, this should be used to ensure a named person or lead professional works appropriately with the young person and other services during the transition planning process.

Commission for Developing Scotland's Young Workforce

In January 2013, the Commission for Developing Scotland's Young Workforce was established. Its final report 1 was published in June 2014.

The report made several recommendations aimed at advancing equalities, with specific focus on gender, race, disability and care leavers. Recommendations relating to young people with disabilities and those leaving care were as follows:

Recommendation 33:

Career advice and work experience for young disabled people who are still at school should be prioritised and tailored to help them realise their potential and focus positively on what they can do to achieve their career aspirations.

(p. 64)

Recommendation 35:

Within Modern Apprenticeships, [Skills Development Scotland] should set a realistic but stretching improvement target to increase the number of young disabled people. Progress against this should be reported on annually.

(p. 65)

Recommendation 36:

Employers who want to employ a young disabled person should be encouraged and supported to do so.

(p. 66)

Recommendation 37:

Educational and employment transition planning for young people in care should start early with sustained support from public and third sector bodies and employers available throughout their journey toward and into employment as is deemed necessary.

(p. 66)

Recommendation 38:

Across vocational education and training, age restrictions should be relaxed for those care leavers whose transition takes longer.

(p. 67)

Recommendation 39:

In partnership with the third sector, the Scottish Government should consider developing a programme which offers supported employment opportunities lasting up to a year for care leavers.

(p. 67)

In December 2014, the Scottish Government responded to the Commission's report in its Strategy paper, Developing the Young Workforce: Scotland's Youth Employment Strategy. 2 This paper set out a number of activities to deliver on the recommendations.

The Scottish Government has published annual progress reports on the strategy for the years 2014-2015, 3 2015-2016, 4 2016-2017, 5 and 2017-2018. 6 The latest report provides the following data on the strategy's key performance indicators relating to young people with disabilities and care experience:

The proportion of young people undertaking modern apprenticeships that self-identified as having an impairment, health condition or learning difficulty undertaking modern apprenticeships increased from 8.6% in 2014-2015 to 11.3% in 2017-2018.

The employment rate of young people with disabilities has increased from 35.2% in 2014-2015 to 43.2% in 2017-2018. However, there still remains a considerable gap between young people with disabilities (43.2%) and those without disabilities (59.4%).

The proportion of looked after children in positive destinations increased from 69.3% in 2012-2013 to 76.0% in 2016-2017.

Transitions of young people with disabilities

The Keys to Life

In 2013, the Scottish Government published its ten year Strategy, The Keys to Life: Improving quality of life for people with learning disabilities. 1

With regard to transitions of young people with learning disabilities, the Strategy sets out the following recommendations:

Recommendation 39:

That by 2014 local authorities, further and higher education providers, Skills Development Scotland and the Transitions Forum work in partnership within the GIRFEC assessment and planning framework to provide earlier, smoother and clearer transition pathways (to include accessible information on their options, right to benefits and Self Directed support) for all children with learning disabilities to enable them to plan and prepare for the transition from school to leavers destination.

(p. 92)

Recommendation 40:

That by the end of 2014 [Scottish Commission for Learning Disability] in partnership with Colleges Scotland, Skills Development Scotland and [Association of Directors of Social Work] consider how people with learning disabilities access educational activities and training at college and other learning environments.

(p. 93)

Recommendation 41:

That by 2018 the Learning Disability Implementation Group works with local authorities, NHS Boards and Third Sector organisations to develop a range of supported employment opportunities for people with learning disabilities and that those organisations should lead by example by employing more people with learning disabilities.

(p. 97)

Recommendation 42:

That local authorities and SCLD work in partnership with Volunteer Scotland and other relevant organisations to increase the opportunity for people with learning disabilities to volunteer within their community to develop work skills.

(p. 97)

The Strategy acknowledges that the most problematic transitions for people with profound and multiple learning disabilities are from child to adult services and from the family home to supported living. Barriers to successful transitions and examples of good practice are outlined, however, no recommendations are set out specific to these transitions.

In its paper, The Keys to Life - Unlocking Futures for People with Learning Disabilities: Implementation framework and priorities 2019-2021, 2 published in March 2019, the Scottish Government reported on progress of the Strategy and set out various revised actions relating to the transitions of young people with learning disabilities into adulthood:

Work with local government to improve the consistency of additional support for learning across Scotland, through improved guidance, building further capacity to deliver effective additional support and improving career pathways and professional development (including new free training resources for schools on inclusive practices).

Work with students, colleges, Colleges Scotland, College Development Network and the Scottish Funding Council to identify examples of best practice within the further education sector, with a particular focus on activity that supports progression to employment and promote the adoption of these across Scotland.

Help to promote the Independent Living Fund (ILF) Scotland's Transition Fund, to ensure that young people with learning disabilities are aware of and encouraged to access support to enhance their independent living, including access to further education and employment.

Challenge attitudes amongst parents, schools, colleges and employers about supported employment services and the potential of people with learning disabilities to succeed in the workplace with targeted awareness raising activity.

Building on the Seven Principles of Good Transitions, and broader recommendations received from sector experts, disabled young people and their families and carers, work across government to improve transitions into education, learning and work for young people with learning disabilities.

A Fairer Scotland for Disabled People

In 2016, the Scottish Government published its national Disability Delivery Plan to 2021, A Fairer Scotland for Disabled People. 1 The Plan is intended to implement obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. It set out the following five ambitions, structured around 93 actions:

Support services that meet disabled people's needs

Decent incomes and fairer working lives

Places that are accessible to everyone

Protected rights

Active participation

Relevant to the transitions of young people with disabilities to adulthood, the delivery plan sets out the following actions:

Action 20:

We will work with schools, local authorities, health and social care partnerships, further and higher education institutions and employers to improve the lives of young disabled people. This includes points of transition into all levels of education – primary, secondary further and higher – education and employment. We will be mindful of young people who have faced structural inequalities and complex barriers that result in lack of employment. We will ensure that supports are in place so that they can live a life of equal participation, with the support they need. We will embed the Principles of Good Transitions, which have been endorsed by 30 multi-sector organisations in Scotland and prioritise person-centred, coordinated support.

(p. 15)

Action 30:

We will pilot a work experience scheme specifically for young disabled people aimed at improving their transition into permanent employment and removing barriers they can face finding employment.

(p. 19)

Action 35:

Disabled young people will be supported through the Developing the Young Workforce Scotland's Youth Employment Strategy. In partnership with local authorities, colleges, employers and Skills Development Scotland, the focus of the Strategy will be on removing barriers to open up the range of opportunities for young people and prepare them for employment are aligned with labour market opportunities.

(p. 20)

Action 36:

We will remove the barriers that have previously prevented young disabled people entering Modern Apprenticeships (MA), through the implementation of The Equalities Action Plan for Modern Apprenticeships in Scotland. The five-year plan includes specific improvement targets for MA participation by disabled people, including part-time and flexible engagement, to be achieved by 2021 and Skills Development Scotland will report on these annually.

(p. 20)

Action 37:

Effective immediately, we will provide young disabled people with the highest level of Modern Apprenticeship funding for their chosen MA Framework until the age of 30.

(p. 20)

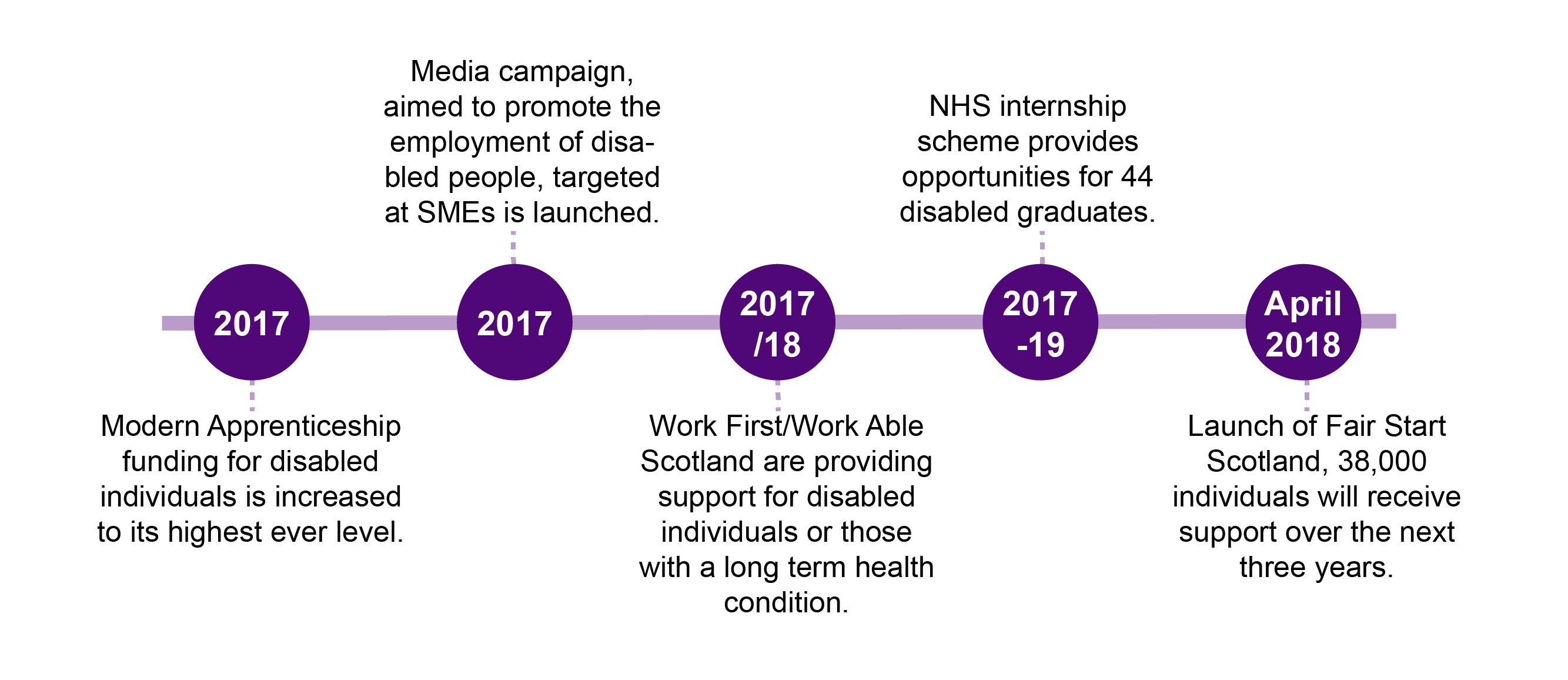

In its progress update, A Fairer Scotland for Disabled People: Progress and Next Steps Towards Fairer Employment Prospects for Disabled People, 2 published in April 2018, the Scottish Government reported the following progress:

In December 2018, the Scottish Government published A Fairer Scotland for Disabled People: Employment Action Plan. 4 In the section, Young People and Transitions, the action plan endorses the Principles of Good Transitions in supporting young people with disabilities to access post-school education, learning and work.

Support for children and young people with disabilities and their families

In June 2018, the Scottish Government published the consultation document, Supporting Disabled Children, Young People and their Families, 1 with the aim of providing information on national policies, entitlements, rights and support options available for children and young people with disabilities. The document is constructed around three pillars:

Rights and Information

Accessibility of Support

Transitions

In the section on transitions, the document lays out and endorses the Principles of Good Transitions. It emphasises that transition planning should be adequately planned and co-ordinated, and that both child and adult services should adopt the GIRFEC approach in planning for transitions.

The document lists various resources which support young people with disabilities who are transitioning into adulthood, further education and work. These include the following:

Scottish Independent Living Fund (ILF) Transition Fund. £5 million per year to support young disabled people aged between 16 and 21 to take part in activities they may not have been able to take part in before and to help them become independent. 23 At the time of writing, 514 young people in Scotland have received support through the fund. 4

Additional Support Needs for Learning Allowance. Support to cover study and travel-related expenses for college students, which arise because of their disability. 5 In academic year 2017-2018, £2,788,696 was allocated to 2,265 students. 6

Disabled Students' Allowance. Support to cover extra costs or expenses students in higher education may have while studying, which arise because of their disability. 7 In academic year 2017-2018, £8.55 million was allocated to 4,655 full-time undergraduate and postgraduate students who also received support from other schemes. In addition, 550 students (£1.17 million) received support through the Disabled Students' Allowance only. 8

Community Jobs Scotland. Support for young people (aged 16 to 29 years) living in Scotland with paid jobs in third sector organisations. According to their website, the programme has supported over 8000 young people. The programme offers part-time jobs for disabled young people, offering a minimum of 16 hours per weeks and lasting for 78 weeks. 9

Workplace Equality Fund. £500,000 delivered by the Voluntary Action Fund to promote equality within the workplace. 10

Fair Start Scotland. An employment support service for those who have struggled to find a job which meets their needs. This may be because, for example, they have a disability, additional support needs or a health condition, or have been in care. 11 For the period of April-December 2018, 7,031 people joined Fair Start Scotland. Of those, 15% were aged 16-24 years and 70% had a long-term health condition. Employment outcomes are due to be published in May 2019. 12

A web based resource for disabled children, young people and their parents is due to be launched by the Scottish Government on 24 April 2019. The website will include: 13

Information Provision and Signposting: Children, young people and their parents will be more aware of services available nationally and locally, and will understand their rights and entitlements and how to realise them.

Accessibility of Services: Access to support and services will be easier and more efficient as families are aware of their rights. Providers will work with children, young people and parents to ensure their needs are identified quickly and they receive support that is right for them.

Transitions: Support and services for children and young people at key points of transition will be better aligned and more responsive to the needs of young people. Services available and transition processes will be more clearly understood by children, young people and their parents.

In January 2019, Contact, which supports families with disabled children, launched the website, Talking about Tomorrow. This provides families with an overview of the transition process, their role within it and advice on what they need to take into account. Additionally, a report from the Talking about Tomorrow project will be published in the next few months. This will share findings from work with around 250 families across Scotland over the last 2 years. 14

Contact argues that some young people with disabilities or additional support needs may not be ready to take up post-school activities in the same way as their peers for many reasons, including illness; developmental delay; anxiety or depression; or poor experience in education. They recommend in these circumstances that the age range to qualify for post-school support programmes be extended, to ensure that all young people have the opportunity to benefit from them. 15

Health and Social Care Transitions

Evidence discussed in this briefing shows that transitions between health and social care services can pose particular difficulties for young people. Differences between child and adult services in the structure of services, eligibility criteria and specialised training of staff are among the factors that evidence suggests can negatively affect young people's experiences of these transitions. 1 Not all areas in Scotland have transition teams or transition facilitators to manage and co-ordinate the transfer to adult services. 2

Health and Social Care Standards

In June 2017, the Scottish Government published, Health and Social Care Standards: My support, my life. 1 The purpose of these human rights based Standards is to drive improvement in health, social care and social work services in Scotland. The Standards were published in exercise of the Scottish Ministers' powers under Section 50 of the Public Services Reform (Scotland) Act 2010 and Section 10H of the National Health Service (Scotland) Act 1978. The headline outcomes of the Standards are:

I experience high quality care and support that is right for me

I am fully involved in all decisions about my care and support

I have confidence in the people who support and care for me

I have confidence in the organisation providing my care and support

I experience a high quality environment if the organisation provides the premises

Think Transition: Developing the essential link between paediatric and adult care

In 2008, the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh Transition Steering group published the guidance document Think Transition: Developing the essential link between paediatric and adult care. 1 The document acknowledges that transitions between paediatric and adult health care services can be challenging for young people with chronic diseases.

The core principles listed in the guidance are as follows:

Each hospital should have a transition policy containing principles of transition from paediatric to adult healthcare.

Transition is not synonymous with transfer to adult services. It is an active process which must be planned, regularly reviewed with the young person and be age and developmentally appropriate.

The transition process should address the young person's health problems and how these affect the young person's wider health, social, psychological, educational and employment needs and opportunities. Illness education and self-management should also be included.

Young people must be included in developing their transition programme and young people should be given the opportunity to be seen without their parents.

Transition services must address the needs of the young people's parent(s)/carer(s).

Transition services must be multidisciplinary and multi-agency, involving speciality teams from child and adult providers, general practice, education, social services and voluntary agencies, as appropriate.

Transitional care should be appropriately co-ordinated. In the case of a young person having complex needs, a co-ordinator should be identified to oversee the transition process.

Young people should have the opportunity and be encouraged to take part in transition/support programmes and youth support groups.

Positive collaboration of adult physicians and paediatricians should occur routinely prior to transfer.

Transition services must undergo continued evaluation.

NICE guideline

In February 2016, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published its guideline, Transition from children's to adults' services for young people using health or social care services. 1 The guideline is linked to English legislation and applies in England, Wales and Northern-Ireland, but has been used to inform development of Scottish Government guidance, such as the mental health Transition Care Plan. 2 The guideline covers the period before, during and after a young person moves from child to adult services within health and social care. It aims to support young people and their carers through the process of transition by improving the way it is planned and carried out. The guideline offers recommendations for professionals involved in the transitions of young people, as well as for further research.

The guideline outlines the following overarching principles:

Young people and their carers should be involved in service design, delivery and evaluation related to transition.

Transition support should be developmentally appropriate, based on the young person's strengths and identify the support already available to the young person.

Person-centred approaches should be used.

Health and social care service managers in children's and adults' services should collaborate to ensure a smooth and gradual transition.

Service managers in adult's and children's services across health, social care and education should proactively identify young people in their locality with transition support needs and start the planning process.

Every service involved with the young person's support should be responsible for sharing and safeguarding information with other organisations, in line with local policies.

A summary of the guideline and a visual representation of what support should be in place during the transition process are presented in a paper published in The BMJ. 3

Anticipatory Care Plans