Housing and Social Security

This briefing considers the impact of housing related welfare reforms on landlords and tenants in Scotland. It sets these in the context of wider welfare reforms taking place across the UK.

Executive Summary

The UK Government's welfare reform programme introduced reforms with the aims of simplifying the benefits system, removing work disincentives and controlling public expenditure.

These reforms include changes to Local Housing Allowance (which determines how housing benefit in the private rented sector is calculated), the introduction of the 'bedroom tax', the benefit cap and Universal Credit (UC).

These changes, along with other wider welfare reforms, have impacted on landlords and tenants in both the private and social rented sectors. For example, in the private rented sector, welfare reform has, in some areas, limited the range of accommodation that people on benefits can afford.

The transition to Universal Credit has also resulted in some administrative problems for landlords, although the DWP is working with landlords to improve the administration of UC. Some landlords have claimed that the move to Universal Credit has resulted in an increase in tenant arrears.

Although some social security powers have been devolved, the Scottish Government has limited control over housing related benefits. It has powers to make Discretionary Housing Payments and powers to vary the housing costs element of Universal Credit. The Scottish Government's priority has been to use these powers to mitigate the impact of the bedroom tax in Scotland.

Housing is a devolved policy area. Some commentators suggest that UK Government welfare reform policies are negatively impacting on Scottish Government policy, for example in relation to the prevention of homelessness.

Glossary of terms

| APA | Alternative Payment Arrangement |

| BRMA | Broad Market Rental Area |

| DHP | Discretionary Housing Payments |

| DWP | Department of Work and Pensions |

| HB | Housing Benefit |

| HRSAG | Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Action Group |

| LHA | Local Housing Allowance |

| RSL | Registered Social Landlord |

| SMI | Support for Mortgage Interest |

| UC | Universal Credit |

Introduction

Since 2010, the UK Government has implemented a programme of welfare reform. The stated aims of the reform programme have been to make public expenditure more sustainable and targeted more effectively, to ensure that the system is fair to the British taxpayer and to those people who are in genuine need of support.

Within this reform programme changes have been made to Housing Benefit (HB) to, in the UK Government's view, create a fairer system by ensuring that people on benefit do not live in accommodation that would be out of reach of most people in work. These reforms have been controversial, although many commentators have acknowledged that HB was in need of reform. Many of the HB reforms have been incorporated within the housing element of Universal Credit (UC).

Although the impact of housing related welfare reforms are the focus of this briefing, it is difficult to separate these reforms from the wider welfare reforms, such as the benefits freeze, which all have a cumulative impact on tenants and landlords. As the Scottish Government's report on Housing and Social Security notes:

...the whole social security landscape will have an impact on the ability of households to meet their rent. Households do not necessarily observe strict demarcations between housing and non-housing related benefits, and reductions in other benefits, and especially the impact of sanctions, may lead to households failing to pay rent, even where the support for housing costs is apparently adequate. Conversely some households will respond to housing losses by reducing their spending on other items, and the impact of this will not be immediately felt by their landlord, nor be visible in any statistical collection.

Source: Scottish Government. (2018, May 14). Housing and Social Security: follow-up paper on Welfare Reform. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/annual-report-welfare-reform-follow-up-paper-housing-social-security/ [accessed 04 January 2019]

The design and operation of the social security system also has implications for landlords in both the private and social rented sectors in terms of how they manage their business and collect rent. As rental income is the largest source of income for social landlords, any reduction in this may ultimately affect their financial viability.

The following sections provide a broad overview of recent reforms that are particularly relevant to housing and those that affect tenants and landlords.

The briefing is not intended to provide a detailed explanation of the benefits referred to, other sources of reading are indicated where appropriate.

Reserved and devolved powers

Among other powers, the Scotland Act 2016 devolved some social security benefits to Scotland, mainly those which support ill-health and disability, and other powers to Scotland. In relation to housing, the key points of the 2016 Act are:

Scottish Ministers have powers to vary the housing cost element of UC for rented accommodation and change payment arrangements for UC

Discretionary Housing Payments (DHPs) are devolved to Scotland

Scottish Ministers also have powers to create new benefits and to top-up existing reserved benefits. They also have the power to create new social security benefits (other than pensions) in areas not otherwise connected with reserved matters.

However, Scottish Ministers cannot change the structure of UC as a whole, and have no powers over HB.

Key Statistics

There are around 455,000 claimants of HB/UC housing costs element in Scotland. Figure 1 provides some further statistics.

Housing in the private rented sector – Local Housing Allowance

Much of the change to HB has affected tenants living in private rented housing. The rules for calculating how much HB/UC housing costs element a tenant is entitled to is different for tenants living in private and social rented housing.

The calculation involves using a figure known as the "eligible rent." In general, in social rented housing the eligible rent is the actual rent that the tenant pays. In contrast, the 'eligible rent' for private rented sector tenant is set at a capped level under the Local Housing Allowance (LHA) rules which were first introduced in 2008.1

Generally, the maximum HB/UC housing costs that will be paid is the LHA rate for the appropriate sized property in one of 18 Broad Market Rental Areas (BMRA) in Scotland. Rent Officers, working at Rent Service Scotland, collect the data which are used to set the LHA rates.

If a tenant wants to live in a property where the rent is more than the maximum LHA they are entitled to, then they will have to pay the additional rent themselves, negotiate with the landlord to reduce the rent, or move to a cheaper property.

Reform to LHA rates

UK Government welfare reforms have changed how LHA rates are calculated (see Annex 1). These reforms were instigated as part of the Government’s policy of reducing expenditure on HB and the desire to exert downward pressure on private sector rent levels.

Key reforms include:

From 2011, LHA rates were set at the 30th percentile of local rents rents rather than the 50th percentile i.e. the LHA would allow access to rents at the bottom 30% of the market.

From April 2013, the direct link between local rents and LHA rates was broken when LHA rates were uprated by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). For the next two years LHA was capped at the previous year's figure plus 1% (or 30th percentile if lower).

From April 2016, LHA rates were frozen for 4 years, although extra 'targeted affordably funding' is available in areas where rents have risen excessively. Therefore, LHA rates are currently set at the 2015-16 LHA rate, or at the 30th percentile of local market rents, whichever is lower.

From Jan 2012, the age to which the 'shared accommodation rate' (SAR) was increased to the under 35s from the under-25s. This means that the maximum HB/UC housing element that single people under-35 can get is limited to the LHA rate for a room in a shared property.

Impact of changes to LHA rates

A key criticism of the changes to LHA rates is that, given increasing rents in some areas, there is a growing gap between the LHA rates and actual rents. Therefore, the range of accommodation where the rent can be fully covered by benefit has reduced. 1

To illustrate this, Table 2 shows how the LHA rates in Greater Glasgow for a 2-bed property compares with the rents at the 30th percentile. In 2018/19, a tenant eligible for full HB would have to pay nearly £22 more a week from other resources if they wanted to rent properties in the lowest third of the market.

| 2016/17 | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LHA rate (weekly) | £116.53 | £116.53 | £116.53 |

| 30th percentile local rents | £126.57 | £132.33 | £138.08 |

| Difference between 30th percentile and LHA rate | -£10.04 | -£15.80 | -£21.55 |

A number of organisations, including the Chartered Institute of Housing, Shelter, Citizens Advice Scotland, and the House of Commons Communities and Local Government Committee, have called for LHA rates to be reviewed. 5671

In its report, Housing and Social Security: follow up paper on welfare reform , the Scottish Government looked at the 2018/19 LHA rates in Scotland and considered the portion of the actual rental market in the area that the LHA rate would cover. Their analysis showed that:

…in only 10 out of 90 rates does the LHA policy meet its original intention of allowing a household to access a property in the 30% [30th percentile] of the local market, in half of the LHA rates less than 20% of the local market can be accessed at the level payable, and in nine rates only the bottom 10% of the market is accessible. …. The most limited market is the Lothian 1 bedroom rate. Fewer than 5% of newly advertised tenancies are accessible at the LHA rate.

Source: Scottish Government. (2018, May 14). Housing and Social Security: follow-up paper on Welfare Reform. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/annual-report-welfare-reform-follow-up-paper-housing-social-security/ [accessed 04 January 2019]

The report also considered the actual cash shortfalls that tenants might be likely to experience. In some areas it was quite small, while in others it was more substantial:

Overall in 26 out of the 90 rates the cash shortfall is more than £10 a week. A small number of rates show substantial shortfalls with the most extreme example being the Greater Glasgow 4 bedroom rate of £206.03 a week which falls more than £80 short of that required to access a tenancy advertised at the true thirtieth percentile. It is worth considering that even apparently small shortfalls may have a substantial impact on the outgoings of a household.

Source: Scottish Government. (2018, May 14). Housing and Social Security: follow-up paper on Welfare Reform. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/annual-report-welfare-reform-follow-up-paper-housing-social-security/ [accessed 04 January 2019]

Research by the Chartered Institute of Housing has also highlighted the growing gap between LHA rates and rents in some parts of the country. Their research argues that the 'targeted affordability funding' could be made more effective.1

Single young tenants - Shared Accommodation Rate (SAR)

The SAR was first introduced in 1996 with the aim of ensuring that HB did not encourage young people to leave the parental home unnecessarily, or to take on higher priced accommodation at the taxpayers‘ expense than they could afford from their own earnings. The SAR has been controversial since its introduction. Several organisations have lobbied for its abolition on the grounds that it makes it very difficult for young adults to find affordable accommodation.1

When the UK Government announced an increase in the age to which the SAR applied (from age under 25 to age under 35) the then Chancellor George Osborne said, “This will ensure that housing benefit rules reflect the housing expectations of people of a similar age not on benefits.” 2However, the move was criticised by many organisations. In its report on Young People Living Independently, the Social Security Advisory Committee critiqued the UK Governments' rationale:

This rationale has some rigour – it is the case that two-thirds of 16-24 year olds live with parents, grandparents, step parents or foster parents. But, the remaining third live independently, including seven per cent of 16-17 year olds. As set out earlier, many have no choice but to live independently. For this group, the assumption that they have other forms of support and few financial responsibilities is false.

Social Security Advisory Committe. (2018, May). Young People Living Independently. A study by the Social Security Advisory Committee Occasional Paper No. 20. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/709732/ssac-occasional-paper-20-young-people-living-independently.pdf [accessed 22 January 2019]

The Committee also pointed out that many young people who live independently on benefits have complex needs or vulnerabilities and may have experience of living in supported accommodation.

Research by the CIH has highlighted that, as younger people are entitled to lower benefit rates, the SRA could increase the risk of homelessness:

Single people aged under 25 only get the shared accommodation rate and a lower rate of JSA (£57.90). On average they are expected to contribute 10 per cent of their JSA on the gap (equivalent to a 17 per cent contribution in real terms).

Young jobseekers’ resilience is severely limited because the basic benefit allowance for this group is so low that any contribution they make to close the gap significantly increases their risk of homelessness.

Source: Chartered Institute of Housing. (2018, August 29). Missing the target: Is targeted affordability funding doing its job?. Retrieved from http://www.cih.org/publication-free/display/vpathDCR/templatedata/cih/publication-free/data/Missing_the_target_Is_targeted_affordability_funding_doing_its_job [accessed 4 January 2019]

The Social Security Advisory Committee's research found that there are almost no rooms available to young claimants on the SAR. The Committee conducted a snap-shot analysis of advertised properties on spareroom.co.uk in eight urban areas. In Edinburgh, it found only 4 out of 587 properties were available at the SAR. Many of the shared rooms tend to be let to students or young workers who are reluctant to let to unemployed people. As the Committee's report argued:

What this means is that some young people on the SAR end up having to pay for one-bed properties with a benefit designed to cover only the cost of a room in shared housing.

Of those who do share, we heard stories about difficulties faced by vulnerable young people sharing with much older adults who exhibited dangerous or bullying behaviour towards the young people. We also heard about young people with mental health issues who struggle with shared living. One young man spoke about moving back into a hostel to avoid having to share a flat with strangers.

Difficulty finding affordable housing also means that independent young people spend a lot of time looking for somewhere to live – distracting them from job search if they are out of work. In some instances, young people may end up living far from the city centre in areas that are farther from friends or family and may have worse employment opportunities or transport links, creating an additional barrier to employment. Additionally, we heard that conditions can be poor...

Social Security Advisory Committe. (2018, May). Young People Living Independently. A study by the Social Security Advisory Committee Occasional Paper No. 20. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/709732/ssac-occasional-paper-20-young-people-living-independently.pdf [accessed 22 January 2019]

The Committee's report made a number of recommendations to the DWP to improve the experience, and outcomes, for young independent people including that the UK Government should, "Publish evidence, in time for the 2019 Spending Review, on the affordability and availability of housing for young people at the Shared Accommodation Rate in every Broad Market Rental Area, and take action where affordability is too low." 6

In its response to the Committee's report, the UK Government accepted the above recommendation, however it believed that it was already doing this with its targeted affordability funding. Therefore, it rejected the need to do anything more at this stage.7

Impact of LHA changes on tenant and landlord behaviour

Impact on landlords and tenant behaviour

Changes to the LHA rates may result in tenants and landlords changing their behaviour. For example, a tenant could try to negotiate a lower rent level with their landlord or move to cheaper accommodation.

Research for the DWP, published in 2014, found that tenants had generally not sought to move to cheaper accommodation. For example, some people wished to avoid disruption to their family by moving. Instead, the research found evidence that tenants have reduced spending in other areas in order to pay their rent, have gone into debt or resorted to foodbanks.1

The same research found that some landlords were more reluctant to let to tenants after the LHA changes and some had made moves to end tenancies of LHA claimants. 1

Specifically, in relation to the SAR changes, another research study, based on interviews with landlords and tenants, found that landlords were unwilling to reduce rents to make them more affordable to younger tenants, especially in high demand areas. Many landlords said that they were reluctant to reduce rents because they were not able to make a return from renting out one-bed accommodation at the SAR rate. There was also a reluctance to let shared tenancies, primarily because of concerns over the additional regulation, management burden and cost of this let.3

There is little Scottish specific research on the behavioural impacts of the changes to LHA rates, particularly since the freeze was implemented.

Scottish Government powers over LHA

The Scottish Government’s powers to vary the housing element of UC would appear to allow it to alter how the LHA is calculated within UC for private sector tenants in Scotland.

The Scottish Parliament's Welfare Reform Committee held an inquiry into The Future Delivery of Social Security in Scotland in autumn 2015. It recommended that the Scottish Government should be, “investigating ways in which it can help support private renters on benefits who may need to pay for larger accommodation than their LHA covers.”1

In general, the Scottish Government's position has been that it cannot mitigate every aspect of the UK Government welfare reforms in Scotland. In its response to the Welfare Reform Committee's inquiry report, the Scottish Government said:

We are listening to stakeholder feedback about Local Housing Allowance rates and will take a range of views into consideration before looking at options to vary the existing system. Private Rented Sector households experiencing financial hardship may apply for the Scottish Welfare Fund or for a Discretionary Housing Payment.

Source: Scottish Government. (n.d.) No title

While the Scottish Government referred to DHPs it is not clear the extent to which households affected by changes to the LHA are applying for, and receiving, DHPs to help meet their rental costs.

Although, the Scottish Government has been considering options, no concrete proposals have yet been put forward. The Scottish Government now appears to be considering the impact of LHA rates in the context of its Ending Homelessness Together: High Level Action Plan, published in November 2018.3

There would be a wide range of issues the Scottish Government would have to consider before using its powers to change the LHA rates for UC tenants in Scotland. Importantly, any cost implication would have to be met by the Scottish Government. Furthermore, it is not yet clear how the UK Government plans to uprate LHA rates once the freeze ends in 2020. As the Scottish Government does not have any powers over HB, any changes to LHA rates under UC would result in two systems operating in Scotland until the full rollout of UC was complete.

Bedroom Tax - social sector tenants

In April 2013, the UK Government introduced the ‘removal of the spare room subsidy’, more commonly known as the ‘bedroom tax.’ The bedroom tax reduces the HB/UC housing cost element of working age social sector tenants (with some exceptions) if they are deemed to be under-occupying their property.i

Since 2014, the Scottish Government has provided local authorities with additional funding for DHPs funding to fully mitigate the impact of the bedroom tax in Scotland.

The Scottish Government's expectation is that anyone affected by the bedroom tax should be able to get DHP from their local authority to cover the reduction in benefit (see more in the section on DHPs).

An estimated 75,000 households in Scotlandii are affected by the bedroom tax with ongoing mitigation of around £50m a year.

The Scottish Government has committed to abolish the bedroom tax for those on UC using its powers in the Scotland Act 2016. However, this has been delayed because of the complicated relationship between the housing element of UC and other reserved policy areas. The Cabinet Secretary for Social Security and Older People, Shirley-Anne Somerville MSP, has expressed her disappointment that the UK Government had confirmed that they will not to be able to implement a solution through the UC system before May 2020. 1

As UC is rolled out it appears that the administration of DHPs to mitigate the bedroom tax has the potential to become more complicated. This is because local authorities used housing benefit administration data to identify those affected by the bedroom tax. However, as UC is administered by the DWP, it is more difficult for local authorities to identify tenants on UC who are affected by the bedroom tax.

Discretionary Housing Payments (DHPs)

DHPs are administered by local authorities. They provide financial assistance to those receiving HB/UC housing costs but are still having difficulty meeting their housing costs. They could be paid, for example, where a claimant's HB does not cover all their rent because of welfare reforms such as the benefit cap, where they need help with removal costs or help with a rent deposit.

As noted earlier, DHPs have been used by the Scottish Government to mitigate the impact of the bedroom tax.

From 1 April 2017, DHPs were devolved to the Scottish Government. They continue to be administered by local authorities and operate in the same way as they did previously. No specific Scottish guidance on DHPs has been published yet, so local authorities are still referring to DWP guidance.

Since 2017/18, the Scottish Government has provided DHP funding for bedroom tax mitigation and DHPs for other purposes. Prior to this, DHP funding was provided in part by the DWP, and topped up by the Scottish Government in order to achieve full mitigation of the bedroom tax.

As Table 3 shows, the budget for 2019/20 is a static budget for ‘other DHPs’ with a slightly higher budget for bedroom tax DHPs (which is largely reflecting an increase in rent). Local authorities can also use their own resources to fund DHPs if they wish to do so.

| 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DHP Bedroom tax | £47m | £50.1m | £52.3 |

| DHP 'Other' | £10.9m | £10.9m | £10.9m |

| Total | £57.9m | £61.0m | £63.2m |

The Scottish Government statistical monitoring of DHPs does not currently provide a breakdown of the reasons for the other DHPs being made, although this management information is being collected and will be published at some point.4

The Benefit Cap

The benefit cap, introduced by the UK Government in April 2013, limits the amount of benefit that people age 16-64 can get. The aims of the measure were to improve work incentives for benefit claimants, deliver savings on welfare support and make the system fair.1

There are some exemptions from the cap. For example, those in receipt of Working Tax Credit (or the in-work exemption for those on UC), Disability Living Allowance, Personal Independence Payment and Carer's Allowance are exempt from the cap.

Most benefits are included in the cap. However, HB costs for 'specified accommodation', i.e. supported accommodation that meets a particular definition in HB/UC regulations, is not included in the calculation of total benefit income. The cap works by cutting HB award or UC award until the overall benefit entitlement is within the cap.

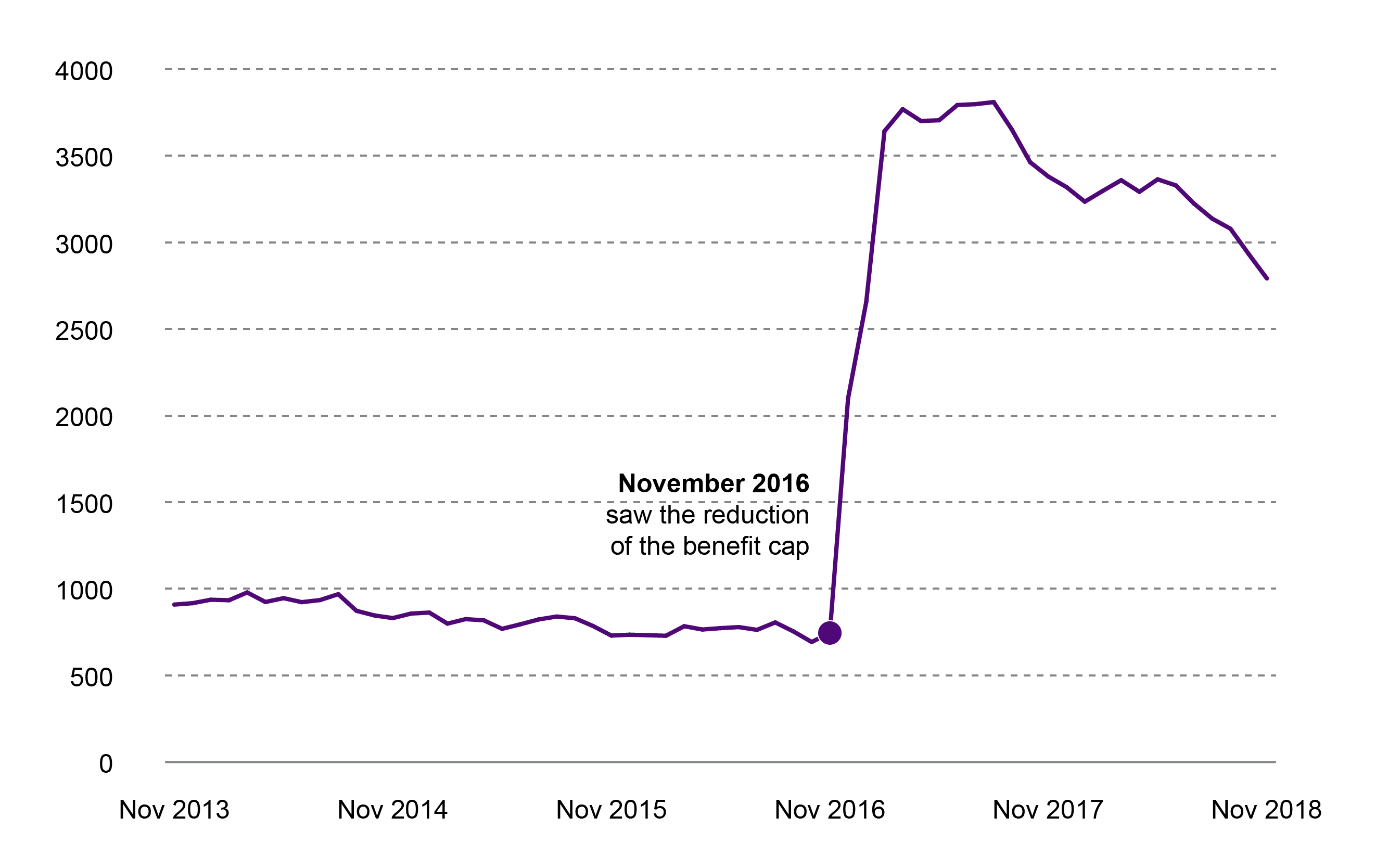

In November 2016, the level of the benefit cap in Scotland was reduced :

from £26,000 to £20,000 per year for families (£385 per week) and

from £18,000 to £13,400 for single people (£258.69 per week).

Benefit Cap statistics

Following the lowering of the benefit cap in November 2016, the number of households in Scotland affected by it immediately increased. In November, 2018, there were 2,792 HB claimants subject to the benefit cap, compared to 693 in October 2016 (see Fig 1).

Absolute numbers are relatively small compared to the total caseload (about 0.6% of total caseload), although there is a disproportionate impact on certain groups of people. Larger families and lone parents looking after children are most likely to be affected by the benefit cap. 2

The average amount of benefit capped has remained around the same as before the cap was lowered: £61.52 in Oct 2016 compared to £56.76 in Nov 2018.

Of the 2,792 HB claimants affected by the cap in Scotland (Nov 18), 68% lived in the social rented sector and 32% lived in the private rented sector. 68% were lone parents.

Impact of the benefit cap

UK Government comment on the impact of the benefit cap has tended to focus on the impact in terms of employment, with claims that capped households were more likely to move into employment than similar uncapped households. 1

However, there may be also be potential impacts on claimants' ability to pay for their housing costs. A number of sources, including evidence to the current House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee inquiry into the Benefit Cap, suggest that some households affected by the benefit cap are falling into arrears.2

Households affected by the benefit cap may also find it difficult to move to cheaper accommodation to reduce their HB support. Around two thirds of households in Scotland affected by the benefit cap are already living in social rented housing, which is generally the cheapest form of accommodation. Shelter's evidence to the Work and Pensions Committee referred to the additional costs of finding a new home, such as moving costs.3

The Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) also argued that social sector tenants with rent arrears could face difficulty in trying to move into cheaper accommodation, as their application for a housing transfer might be adversely affected due to their debt. 4

A Citizens Advice Scotland report on the Impact of reducing the benefit cap, recommended that the UK Government reconsider lowering the benefit cap, with particular regard to the impact on lone parents. They also recommended that:

The UK and Scottish Governments examine the effects of the Benefit Cap on people in temporary homeless accommodation; people who have been subject to domestic abuse; and the willingness of landlords to accommodate people affected by the Benefit Cap, and put steps in place to ensure that it does not act as a deterrent to people finding suitable, settled, affordable and appropriate homes.

Source: Citizens Advice Scotland. (2017, May). The impact of reducing benefit cap. Retrieved from https://www.cas.org.uk/system/files/publications/impact_of_reducing_the_benefit_cap.pdf [accessed 08 January 2019]

A CIH report, based on interviews with people affected by the benefit cap, found that the benefit cap was having an impact on household finances and on the health of the children of the households affected. Other points emerging from the interviews included the quality of communication with those affected by the cap, the complexity of the welfare system and barriers to people finding work or increasing their hours if they were already working.6

An evaluation of the impact of the lowered benefit cap has been commissioned by the DWP, the results of which are due to be published in spring 2019. 7

DHPs and the benefit cap

Households affected by the benefit cap may be able to claim a DHP to help pay their rent. A report by One Parent Families Scotland and CPAG Scotland found different approaches from local authorities in the use of DHPs to support those affected by the benefit cap.

The majority of local authorities said that they would determine DHP awards to mitigate the benefit cap on a case by case basis. However, the response amongst the other authorities varied. For example, two local authorities said they would make a maximum award of six months and two local authorities said they would make awards for 13 weeks before reviewing the award.8

The report made a number of recommendations including that the Scottish Government should consider mitigating the impact of the benefit cap in full through DHPs, and improve the consistency of local authorities' DHP response through guidance. 8

Universal Credit

UC is replacing a number of working age benefits, including HB. A UC award will include an amount for housing costs (if the claimant is eligible). The calculation of the UC housing costs element for rented accommodation has many similarities to housing benefit rules, although there are some differences. The House of Commons Library Briefing Housing Costs in Universal Credit provides a detailed overview of the matter.1

UC is being implemented on a phased basis. It was introduced first in Scotland in 2013 in the Inverness area. Roll out of 'Full service UC' (the final digital version of UC) for new claimants was completed in Scotland at the end of 2018. This means that the legacy benefits are generally not available for new claimants (some people can still claim legacy benefits, including people with 3 or more children, or qualify for the severe disability premium). Instead, a claim for UC must be made. Existing claimants of legacy benefits may also move onto UC if there is a change in their circumstances, which requires a new claim.

The UK Government plans to start transferring people on existing legacy benefits or tax credits onto UC on a pilot basis from July 2019. This 'managed migration' process is expected to be complete by December 2023.

At the same time as the full implementation of UC, the UK Government will transfer the rent support from HB to Pension Credit.2

The transition from HB to UC

The transition from HB to UC involves considerable changes to benefit and rent collection processes and systems which has created some administrative problems for tenants and landlords.

For example, UC is calculated on a monthly assessment period, which is not always a calendar month, and is paid on a monthly basis in arrears. However, the assessment and payment of UC does not always align with how landlords collect their rent.

Local authorities have to rely on the DWP for information that they previously had access to via their role in administering HB. This includes arrears information, eligibility for passported benefits and council tax reduction. Registered social landlords, who may have had good working relationships with local authority housing benefit staff, are having to establish working relationships with the DWP.

The DWP has been working with landlords on a number of administrative improvements. These include allowing social landlords to manage their Universal Credit caseload via an online portal and the implementation of Trusted Partner status, which allows landlords to apply for Alternative Payment Arrangements (APAs) for their tenants without having to provide supporting evidence for each individual case.

In general, managing the impact of welfare reforms, and UC specifically, has been a resource intensive process for landlords. For example, some housing associations have appointed additional staff to manage the impact. The remit of these staff has varied with appointments being made, for example, in the areas of benefit and money advice; income collection; IT and data monitoring. Other costs may be incurred including updating IT systems and communications with tenants. 1

Support for making UC claims

The DWP's Universal Support programme allows claimants to get support to make an online claim (called Assisted Digital Support) or help to manage monthly payments through Personal Budgeting Support. This is currently delivered in Scotland through local authorities either directly or through external services contracted by the authority. From April 2019, this will be provided by Citizens Advice Scotland.

Support for UC claimants - consent process

In some cases, landlords, or other third parties, may wish to provide a claimant with support with their claim. At the moment, someone can give another person or organisation their explicit consent to help with their UC claim. With explicit consent having been given, a landlord can contact the DWP and once their identity has been confirmed the case manager will be able to talk to the landlord directly.

However, the Scottish Federation of Housing Associations (SFHA), has said that housing association staff have go through a separate consent process every time they try and sort out a problem with the DWP on behalf of vulnerable tenants, and that, “This makes it significantly harder for housing associations to sort out issues, causing unnecessary delays and stress and hardship for people.”1

A system of implicit consent for landlords existed under the UC live service but this has not been carried over to the UC full service.2 The DWP's reason for this is that the online digital account contains access to all the claimant's personal, medical, financial and other data. Therefore, a system of implied consent would mean that the risk of disclosure of this material to third parties would be heightened beyond an acceptable level under data protection rules. 3 A system of implied consent is in place for MPs assisting constituents because of the pre-existing relationships between MPs offices and DWP District Managers and their teams.4

SFHA has argued that the DWP should have a system of implied consent and that:

This would allow third parties such as housing association benefit advisors and citizens advice bureau workers to intercede on behalf of claimants to help ensure they are getting their correct entitlement, and that they are not unintentionally falling foul of the conditionality expectations. The Universal Credit full service survey found that a significant minority were having difficulty registering or managing their claim. Sanctions on Universal Credit claimants are currently running at around 10%.

Source: Inside Housing. (2018, July 12). Universal Credit needs a rethink if we are to build a country that works for everyone. Retrieved from https://www.insidehousing.co.uk/home/home/universal-credit-needs-a-rethink-if-we-are-to-build-a-country-that-works-for-everyone-57172 [accessed 08 January 2019]

Where a managed payment arrangement is in place both social and private landlords are able to access certain information, i.e. when to expect the next payment and the payment amount, without the need for consent from the claimant.2

UC and rent arrears

Since the introduction of UC concerns have been raised, in particular by local authorities, about the relationship between UC and increasing rent arrears.

In 2016, three local authorities (Highland, Inverclyde and East Lothian) gave evidence to the Social Security Committee on the roll-out of UC. In addition to reporting an increase in the level of rent arrears, the authorities spoke about increased pressures on support services, rent management staff and the Scottish Welfare Fund.

Increases in rent arrears due to UC are attributed primarily to the fact that:

UC is paid in arrears, so claimants wait for five weeks for their first payment.

UC is paid monthly, but rent in the social sector is normally due weekly.

Payment is made to the claimant, not direct to the landlord as it was under HB for social housing tenants. Some tenants, particularly if they have fluctating earnings, may find monthly budgeting difficult.

In November 2017, the UK Government announced several changes that would come into effect in 2018 to help prevent rent arrears by offering more support at the start of a UC claim:

From January, interest-free advances of up to 100% of one month's UC entitlement were made available, with the recovery time for advance payments extended from six to twelve months.

In February, the seven-day waiting period was abolished. This reduced the overall waiting time from six to five weeks and means that UC entitlement begins on the first day of the application.

As of April 2018, those already on HB will continue to receive their award for the first two weeks of their UC claim (this is known as ‘HB run-on’). This aims to help people with their housing costs while they wait for their first UC payment, and does not need to be repaid.

A range of further changes were announced in the 2018 Autumn Budget.1These include increasing the work allowance, and from July 2020, providing two weeks of support during the transition to UC to include the income related elements of Jobseeker's Allowance, Employment and Support Allowance and Income Support.

Most publications assessing the impact of UC on rent arrears use data that pre-dates the changes which were implemented between January and April 2018. As such, this evidence does not fully take into account the DWP changes outlined above.

The evidence on increasing rent arrears includes:

A DWP analysis of one (unnamed) housing association showed that those claiming UC had some rent arrears before their UC claim. This amount increased sharply over the 4-6 weeks during which people awaited their first payment. Although the overall amount of arrears did reduce over time, it never returned to pre-UC levels. The DWP has indicated that it plans to extend this research as this limited analysis cannot be considered representative. 2

A paper for the February 2018 meeting of East Lothian Council’s Policy and Performance Review Committee showed that, between April and December 2017, rent arrears had increased by over £45,000.3 The paper noted that over the period, while debt owed by tenants not claiming UC had reduced by around £122k, debt owed by tenants claiming UC had increased by around £167k. In addition, the paper stated that the work generated by the UC full service had been ‘unprecedented’ and that an additional £100k from the Council’s Housing Revenue Account had been made available in 2017/18 to support the rent collection service in mitigating the impact of UC on rent arrears. 2

A SHFA survey found that 24 housing associations in Scotland had over £1.2million of arrears debt from tenants on UC. In addition, 65% of Universal Credit tenants were in arrears, compared to 32% for all other tenants.5

A more recent report by Citizens Advice argues that:

while changes introduced by the Government since 2017 have started to help people they have only made a dent in the problem rather than fixed it. People face particular problems during the five week wait for a first payment but financial problems can last beyond this.

Citizens Advice. (2019, February 6). Managing money on Universal Credit. Retrieved from https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/Global/CitizensAdvice/welfare%20publications/Managing%20Money%20on%20Universal%20Credit%20(FINAL).pdf [accessed 19 February 2019]

Although there has been much discussion of a relationship between UC and rent arrears there is relatively little up-to-date robust Scottish evidence about the impact of UC on rent arrears.

As noted in the Scottish Government’s recent paper on Housing and Social Security, any potential relationship between UC and rent arrears is dependent on the behavioural responses of the individual e.g. how they choose to manage their budget, prioritise spending etc. In addition, the ability of someone to pay rent is not solely contingent on housing-related benefits. It can be affected by different aspects of the welfare system or other, perhaps unforeseen, events.7

Private rented housing and UC arrears

There is less evidence available about the impact of UC and rent arrears in the private rented sector.

A Residential Landlords Association report, Investigating the effect of Welfare Reform on Private Renting, reported findings from survey of (mainly English) private landlords. The survey found that around a fifth of landlords let to tenants on UC. Of those, 61% had experienced their UC tenants going into rent arrears in the past 12 months. This has more than doubled in the past two years. Twenty eight per cent of landlords reported that they had to evict a tenant on UC in the past 12 months, with the primary reason being rent arrears. 8

The report also argued that the significant increase in rent arrears for both UC tenants and ‘legacy’ HB tenants points to wider issues than just the implementation of UC and referred to changes to the LHA rates. Uncertainty over rent payments and the prospect of tenants falling into arrears have been cited as reasons why private landlords are reluctant to let their properties to those on UC. 8

UC and direct payments to landlords

The default position is that UC is paid to the tenant. However, the housing element of UC can be paid direct to landlords either through DWP Alternative Payment Arrangements or Scottish choices (see Table 1 for a summary of the differences):

DWP Alternative Payment Arrangements (APAs): A tenant's need for, or a request for, an APA may be identified at the outset by the Jobcentre Plus work coach during a Work Search Interview, alongside Personal Budgeting Support, or during the claim e.g. because the claimant is struggling with the single monthly payment. In Scotland, 20,469 (27%) households claiming the UC housing element have a managed payment to their landlord (19,536 social rented; 884 private rented).

The SFHA has raised a concern that social landlords receive these payments, "in arrears on varied and unpredictable dates which causes confusion." It argues that landlords should be paid rent at the same time it is deducted from the tenant's benefit.1

The DWP pays social landlords in a single bulk payment, with a schedule attached. Landlords then have to manually sort thorough the data to identify each tenant and their payment amount. Landlords report that this is a labour-intensive process for them and it can cause distress to their tenants. In addition, even though rent has been deducted from claimants' UC awards, for several reasons, including admin errors and non-payment by the DWP, this is not always clear to landlords and can result in a claimant building arrears.

Citizens Advice Scotland provided an example of the above in their October 2018 Rent Arrears report.

A West of Scotland CAB reports of a client who has received a call from his local authority landlord stating that he has rent arrears of £641. The client was aware of some arrears, but it seems that his direct housing payment from Universal Credit was not made to the council despite being deducted from his UC award, so his arrears have increased by £309. When the CAB adviser contacted the local authority housing team they advised that this is “a common problem” and there are lengthy delays with the local authority receiving the payments from DWP.2

Private landlords have also reported difficulties, including long waiting times when applying for APAs. The Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, Amber Rudd, has acknowledged the concerns of private landlords and the, "need to make it easier for tenants in the private sector to find and keep a good home, by giving landlords greater certainty that their rent will be paid." In January 2019, she announced that the DWP will build an online system for private landlords, so they can request (where necessary) for their tenants' rent to be paid directly to them.3

Direct payments through Scottish choices. The Scottish Government has used its powers to vary the housing element of UC to give UC claimants the choice of direct payment to the landlord. Through Scottish choices claimants can also request a more frequent payment of UC i.e. twice monthly instead of monthly.

These choices have been offered to people making new claims for UC in full service areas since 4 October 2017, during their second assessment period, and for existing claimants since 31 January 2018.

Again, social landlords have reported administrative difficulties with the Scottish choices direct payment to landlords as it can take up to 17 weeks for payment to arrive. Some social landlords are reporting that they would currently not advise tenants to take up a Scottish choices payment for direct payment given the delay in payments from DWP.4

Statistics on Scottish Choices

Of the 75,138 households in Scotland receiving the housing element of UC (at Aug 2018):

11,403 (15%) households have chosen, through Scottish choices, to have their payment made direct to their landlord (10,076 social rented; 1,319 private rented).

15,159 (20%) households have chosen to have their UC award paid more frequently through Scottish choices (12,238 social rented; 2844 private rented).

5,071 (6.7%) households have chosen both direct payment and more frequent payment (4.488 social sector; 581 private sector).

Source: DWP Stat-xplore, Nov 2018

| APAs | Scottish Choices |

|---|---|

| Can be requested by either the tenant or their landlord. | Only tenants are offered Scottish choices. |

| An APA can be requested by the tenant at any time during their UC claim. This can enable a tenant's rent to be paid directly to their landlord from their first UC payment if necessary arrangements are in place. | Tenants are offered Scottish choices in their second assessment period. Therefore, the first UC payment will include their housing costs which will need to be paid to their landlord. They can also be requested by the tenant at any time. |

| Tenants that request an APA have their need for direct payment to their landlord assessed against various criteria, i.e. does the tenant have severe/multiple debt problems; do they have learning difficulties? APAs are not made automatically and are regularly reviewed. | Anyone can exercise their choice to pay their landlord directly. No other qualifying criteria are applied. |

| Landlords requesting an APA must demonstrate that their tenant is in arrears and having difficulty paying their rent. Their application will then be considered. APAs are not made automatically and are regularly reviewed. | Direct payment to the landlord continues under Scottish choices unless the tenant chooses to revert to paying their rent themselves. |

Supported and Temporary Accommodation

Supported housing

Supported housing covers a range of different housing types, including group homes, hostels, refuges, supported living complexes and sheltered housing. Residents of supported housing generally require a level of personal care, support or supervision. The cost of meeting this non-housing-related support is met separately from HB.

If supported accommodation is defined as 'supported exempt accommodation'i the benefit cap and bedroom tax will not apply. If accommodation is defined as 'specified accommodation' (a wider definition than supported exempt accommodation) it will be exempt from the benefit cap, but not the bedroom tax.

The UK Government had planned to replace HB for supported housing with other types of funding for local authorities.ii However, these plans will not go ahead and supported housing will be paid for through HB. So, for some forms of accommodation, people will still receive HB even if they are also getting UC for their non-housing costs. People may move between tenancies paid for via HB and those paid for via UC.

Temporary Accommodation

Under homelessness legislation local authorities have a duty to provide temporary accommodation to homeless households in certain circumstances e.g. where they are awaiting an offer of permanent accommodation.

Many people living in temporary accommodation will be claiming benefits. The relatively high cost of temporary accommodation can mean that benefit may not cover all the rent. This can lead to rent arrears accruing and can also act as a disincentive for people living in temporary accommodation to take up employment.1 Many local authorities have been reviewing their temporary accommodation strategies with a view to reducing the charges.

A Citizens Advice Scotland report on rent arrears provides examples of how the benefits systems has impacted on clients' rent arrears. For example, this quote illustrates the difficulties of one of their clients living in temporary accommodation:

A West of Scotland CAB reports of a client who is living in temporary homeless accommodation. Her Housing Benefit does not cover the full costs of her rent and arrears are accruing on a weekly basis. The client works part time and pays a lump sum towards the debt when she can. She has applied for Discretionary Housing Payment twice but has been declined on both occasions.

Citizens Advice Scotland. (n.d.) Rent Arrears: Causes and Consequences for CAB Clients. Retrieved from https://www.cas.org.uk/system/files/publications/rent_arrears_oct_2018.pdf [accessed 22 January 2019]

The cost of temporary accommodation was supposed to be met through UC. However, concerns from local authorities about this led the UK Government to announce that, from 11 April 2018, full service UC claimants entering temporary accommodation will be required to make a claim for HB. Claimants already living in temporary accommodation, and on UC, will remain on UC until their circumstances change.

Preventing homelessness has been a policy theme of the Scottish Government for a number of years. Preventing homelessness and rough sleeping has been given a renewed policy focus by the Scottish Government with the setting up of the Homelessness and Rough Sleepers Action Group (HARSAG) in 2017.

HARSAG's final report noted the main risk factor for homelessness was wider poverty and inequality (especially poverty in childhood) and that housing and welfare policies can exacerbate or ameliorate the impact of these risk factors and cause or prevent homelessness. Furthermore:

Decisions about social security have a direct impact on homelessness. The poverty resulting from benefit caps and freezes, the impact of sanctions on people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness, the limits on the housing element of benefits, and waiting times for Universal Credit, and other aspects of welfare reform all act to increase the pressure on people living on the edge of homelessness

Source:Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Action Group. (2018). Ending Homelessness: The report on the final recommendations of the Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Action Group. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/factsheet/2018/06/homelessness-and-rough-sleeping-action-group-final-report/documents/c98c5965-cabf-4933-9aae-26d9ff8f0d12/c98c5965-cabf-4933-9aae-26d9ff8f0d12/govscot%3Adocument [accessed 15 January 2019]

HARSAG made a number of recommendations to ensure that the social security system supports households to avoid homelessness and to exit homelessness as quickly as possible when it does occur. These recommendations included reforming the way the LHA is calculated, raising the benefit cap and that Scottish Government and COSLA should present a strong case to the UK Government for temporary accommodation funding support through housing benefit to be devolved to Scotland. 3

In response to HARSAG's final report, the Scottish Government published its Ending Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Action Plan on 27 November 2018. In the plan, the Scottish Government commits to, "push the UK Government to reverse the changes to the welfare system they have introduced that put people at risk of homelessness." Also:

In 2019 we will undertake a full analysis of the HARSAG recommendations on changes to the UK welfare system policy and delivery. Recognising that powers in this area are currently reserved, we will work collaboratively with DWP to maximise operational improvements to make sure that people experiencing homelessness and those at the risk of homelessness are treated with dignity.

Source: Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Action Group. (2018). Ending Homelessness: The report on the final recommendations of the Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Action Group. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/factsheet/2018/06/homelessness-and-rough-sleeping-action-group-final-report/documents/c98c5965-cabf-4933-9aae-26d9ff8f0d12/c98c5965-cabf-4933-9aae-26d9ff8f0d12/govscot%3Adocument [accessed 15 January 2019]

Help for owner occupiers : Support for Mortgage Interest

Owner occupiers can receive some help with their mortgage costs in certain circumstances. If someone owns the property they live in and they have a mortgage or other loan secured on the property they may be eligible for Support for Mortgage Interest (SMI).

SMI is available to people who are out of work, or of State Pension age, and claiming certain benefits. UC claimants will only qualify for SMI if they do not have any earned income.

SMI payments are normally paid direct to the lender and can start either:

after the claimant has had 9 consecutive UC payments

after other qualifying benefits have been claimed for 39 consecutive weeks

The waiting period does not apply to those on Pension Credit.

Changes to SMI

Prior to April 2018, SMI was a benefit that did not have to be repaid (the House of Commons Library briefing paper Support for Mortgage Interest (SMI) scheme provides a detailed background to the scheme).

However, from April 2018, SMI is paid as a loan which the homeowner will need to pay back, with interest, when the property is sold or ownership is transferred (the loan can also be paid back before that).

The UK Government’s rationale for the change, introduced through the Welfare and Work Reform Act 2016, was that since the benefit was introduced, the housing market has changed dramatically. The government argued that many homeowners have significant equity in their property. Therefore, in many cases taxpayers were seen to be effectively funding the accumulation of a potentially valuable capital asset.

The other main reform made to SMI through the Welfare and Work Reform Act 2016, introduced from April 2016, was the increase in the waiting period for SMI from 13 to 39 weeks.

Impact of changes to SMI

In 2018, the Scottish Government estimated that UK Government changes to SMI would affect between 10,000 and 20,000 households in Scotland, reducing social security spending by £20 million a year by 2020-21. 1

Claimants eligible for SMI on or after 6th April 2018, have been contacted by the DWP to ask if they want to take up the offer of a loan. DWP data shows that, at November 2018, of the 102,000 claimants contacted, only around a quarter (22%) had accepted the move to a loan, 71% declined the offer, while 7% were undecided. Separate Scottish statistics are not published.2

The House of Commons Library Briefing Support for Mortgage Interest (SMI) scheme provides more information about the reaction to the changes.

Annex 1: Summary of main welfare reforms affecting housing

| Change | Sector affected | Date |

| Private | 2011 |

| First phase of uprating of non-dependent deductions | Private & Social | 2011 |

| Shared Accommodation Rate (SAR) for single people living in shared accommodation extended from under 25s to under 35s | Private | 2012 |

| LHA rate uprated by CPI (or 30th percentile of rents if lower) | Private | 2013 |

| Bedroom tax (Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy) - Housing Benefit reduced for under-occupying tenants of working age. | Social | 2013 |

| Benefit Cap for working age households - caps the total amount of benefit a household can receive at the national average earnings | Private & Social | 2013 |

| LHA capped at previous years’ figure plus 1% (or 30th percentile if lower).UK Government introduced targeted affordability funding (TAF) is available in areas where rents are rising excessively/ | Private | 2014 (applied in 2015 too) |

| First Universal Credit new claims in Scotland. To be followed by a phased migration of existing claimants. | Private & Social | 2014 |

| Uprating of working-age benefits and tax credits capped at 1% | Private & Social | 2014 |

| Family Premium in Housing Benefit will be removed for new claims and new births from April 2016. | Private & Social | April 2016 |

| Freeze working age benefits and LHA rates for 4 years - applicable amounts for Housing Benefit From 2016/17 to 2019/20 | Private & Social | April 2016 |

| Backdating of Housing Benefit limited to 4 weeks rather than 6 months | Private & Social | April 2016 |

| Housing Benefit payments limited to 4 weeks for claimants who are outside Great Britain | Private & Social | April 2016 |

| Reduced Benefit Cap for working age households - Reduced to £20k (£13,400 for single people) a year outside London | Private & Social | Phased introduction from April 2016 |

| Support for Mortgage Interest changed from a benefit to an interest-bearing loan, secured against the mortgaged property. | Owner-occupier | April 2018 |

| The maximum LHA levels will receive a 3 per cent increase. This means any rates previously at the maximum levels and identified to receive TAF in 2018/19, will be allowed a 3 per cent increase instead of remaining capped. | Private | 2018 |

Source: based on Scottish Government Welfare Reforms Affecting Housing

Please note the above is not an exhaustive list.