Agriculture and Land Use - Public money for public goods?

This briefing provides an overview of public goods in the context of Scottish agriculture and land use. It outlines the benefits, challenges and considerations of basing any land use policy or agricultural support scheme implemented to replace the EU's Common Agricultural Policy, on a model of 'public money for public goods'.

Executive Summary

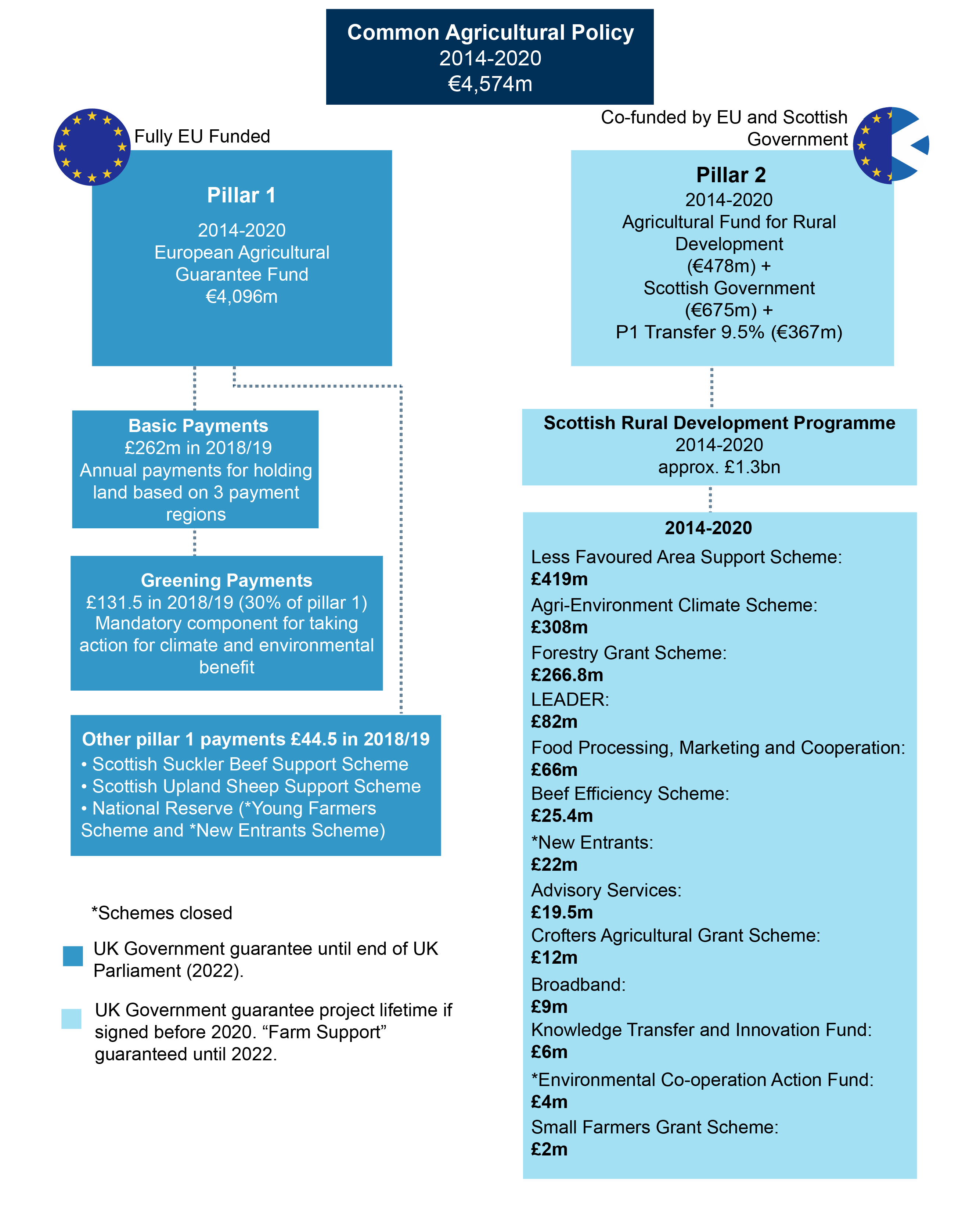

One of the impacts of leaving the European Union is that the UK will no longer be part of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Agricultural policy is devolved, so the Scottish Government is responsible for deciding how the CAP would be replaced after EU Exit. The National Farmers Union Scotland and environmental organisations have suggested that Brexit presents an opportunity to design a new support system to suit Scottish priorities.

CAP support is highly significant in terms of total farm incomes and protecting against volatility in the agriculture sector. However, the CAP has been criticised for not reaching its potential to deliver positive environment outcomes.

In England, the new agricultural support system will be based on a model of 'public money for public goods'. In a land-use context, public goods could include:

flood protection and water purification;

carbon sequestration (where carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere and the carbon is stored, including by new tree growth);

biodiversity enhancement;

landscape value;

recreation opportunities.

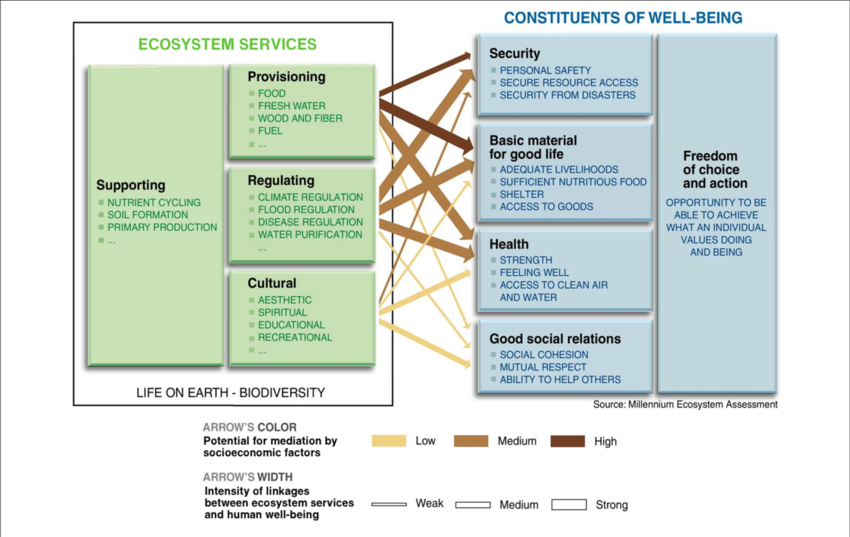

Public goods that can be provided by agriculture and land management are mostly benefits provided to society by ecosystems - known as ecosystem services.

Public goods exhibit two defining characteristics; they are non-excludable i.e. their benefits cannot be confined just to those who have paid for them, and they are non-rivalrous i.e. consumption by one person does not restrict consumption by others. Due to these characteristics, public goods are subject to the the 'free-rider' problem where people can consume them without paying, and this market failure leads to under-supply.

A range of policies and mechanisms exist to try and rectify the market failure of the free-rider problem - including through regulation, tax incentives, and voluntary schemes. Paying land managers for the provision of public goods is one form that payment for ecosystem service schemes can take. Public money may be the most likely source of funding for true public goods. For example in relation to the maintenance or enhancement of carbon sinks (e.g. through woodland creation and peatland restoration) and biodiversity, it can be difficult to find beneficiaries (or enough beneficiaries) who are willing to pay for their provision privately - although there are many examples of privately funded or co-funded 'payments for ecosystem services' schemes internationally.

This briefing examines how a public money for public goods model could work in practice in the agricultural sector, and what international and national policy commitments such a system could be aligned with - including on climate change, biodiversity, natural capital, pollution and water. Some stakeholders have suggested that agricultural support should fit into a wider land-use policy and be integrated with further policy areas, including food.

Background

As a member of the European Union (EU), UK environmental and agricultural policy are based on EU directives and common frameworks. In particular, UK and Scottish agricultural policy sit within the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), the EU's common framework for the regulation and financial support of agriculture. When the UK leaves the EU, it will leave the CAP, and agricultural and environmental policy will be set domestically. As agriculture is a devolved area Scotland will be able to adopt its own farm support policy, although funding will be provided by the UK treasury, and it is currently unclear how funding might be distributed across UK countries. There is a section on agriculture in the SPICe briefing on the Withdrawal Agreement.

What form these policies take in Scotland will have a strong influence on rural development and the environment. 17% of the Scottish population live in rural areas1 and in 2016 agriculture (including crops, fallow, grass as well as rough and common grazing) comprised around 80% of Scotland's total land area2. Other SPICe briefings cover post-Brexit plans for agriculture3 and the wider implications Brexit has for the environment4.

This briefing covers public money for public goods (PMfPG), a model which could form the basis of a new system of agricultural support and land use policies. Public goods are services which have benefits for society that cannot be restricted to particular groups of people. In a land use context, public goods include carbon sequestration, biodiversity maintenance or enhancement, flood control and public access.

There are indications that the Scottish public supports reorienting agricultural support towards providing public goods as well as food. In a poll commissioned by Scottish Environment LINK, 77% of respondents said that they would like to see farm support be conditional to land managers showing that they are supporting wildlife and reducing climate impacts5.

The Scottish Government's Agriculture Champions stated in their final report:

Stewardship of the countryside should be a key part of future policy. The policy priorities to be supported must cover purely public goods such as wildlife and carbon sequestration for which there is no market mechanism, at least at present, but can also include joint public-private benefits – such as reducing waste and improving soils which are good for the individual business as well as the environment and society6.

The opportunity to set new policies in this area has been hailed as a 'once in a generation opportunity to secure public goods for society' by some campaign groups7. In written evidence to the UK Parliament regarding the UK Agriculture Bill, the National Farmers Union Scotland (NFUS) stated:

A future agricultural policy that fits the needs and profile of Scottish agriculture, and all that it underpins, is the real prize that can be secured from the UK's withdrawal from the European Union. 8

What are public goods?

Public goods exhibit two defining characteristics. They are:

Non-excludable: Their benefits cannot be confined to those who have paid for them.

Non-rival: Consumption by one person does not restrict consumption by others .

A useful example is flood defences. This infrastructure is generally publicly funded, benefits everyone who lives close to it (or potentially at some distance away), and benefits for one person do not prevent others from also benefiting. It has been argued that a shortfall in the provision of public goods in rural areas, such as flood prevention, biodiversity maintenance and climate mitigation, compared to the scale of public demand, justifies public intervention1.

Whilst lots of things can be considered to provide a 'public benefit', such as healthy food and healthcare, there is a difference between these and 'public goods'. For example, healthy food provides a public benefit, but as it is sold into a market and its value can be captured by the supplier, it is not a public good.

Public goods provided by land managers are also often referred to as 'ecosystem services' i.e. the benefits that society obtains from ecosystems2. These can be split into four groups, provisioning, regulating, cultural and supporting (Figure 1).

Public goods and ecosystem services can also both be discussed in the context of economic 'externalities'. An externality is a cost or benefit of an economic transaction that affects a party not involved in the transaction. Both positive and negative externalities can result from food production (see table below).

| Type of externality | Negative | Positive |

|---|---|---|

| Description | Costs to society that are not reflected in the cost of food because they are not confined to the supplier | Provision of ecosystem services |

| Examples |

|

|

Addressing under-supply of public goods using payments for ecosystem services

Public goods are not usually provided by the private sector because people who have not paid for them cannot be excluded from consuming them. This is called the free-rider problem and means that it is difficult or impossible to supply public goods for a profit, resulting in their under-supply. In the context of land use, as land is largely privately owned and is used to provide profits for the owner or tenant, farmers and land managers may have no or little incentive to provide public goods. A WWF report encapsulates this issue:

Consider a land owner in Brazil, for example, who chooses to clear forest for cattle-grazing. He is unlikely, in the absence of incentives or requirements, to take into account the potential climate change impacts on a farmer in Africa or community in Bangladesh. [Payment for Ecosystem Services] schemes attempt to address this problem by compensating landowners and land managers for the ecosystem services they provide, or incentivising them to provide extra ecosystem services, thus 'internalising' the externality. The need for schemes that compensate providers of ecosystem services also stems from the fact that the beneficiaries of ecosystem services are often located some distance away from the locus of the generation of the service. They do not have control over or responsibility for the delivery of the service, yet freely 'consume' or benefit from the service1.

A range of policies exist around the world to try and rectify the under-supply of public goods from agricultural land2. Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) schemes are where land managers are compensated for activities that support the provision of ecosystem services. The model of 'public money for public goods' essentially refers to a PES model where the funding comes from the public sector.

Key principles of a PES scheme: 3

Participation is voluntary

The beneficiary pays: payments are made by one or more beneficiaries of an ecosystem service, or governments acting on their behalf

The provider is paid: payments are made to one or more service providers

Additionality: payments are made for actions above the minimum standards required by regulation i.e. not a substitute for a baseline level of regulation

Conditionality: payments are only made if the service provider delivers

Ensuring permanence: management interventions designed to provide services should not be easily reversible

Avoiding leakage e.g. payments to maintain tree cover within one area do not lead to deforestation in another location

PES schemes can operate on a range of scales from local to global and there are examples from all over the world. Central and South American have been leading the way in developing PES for watershed services4 (see case study on Costa Rica below) but there are also examples in Europe. For example, since 1993, mineral water brand Vittel has paid farmers in the catchment at the foot of the Vosges Mountains to adopt best dairy farming practices to maintain water quality5.

There have been few examples of PES schemes in Scotland. One example is Scottish Water's Sustainable Land Management Incentive Scheme (SLMIS), a pilot project which started in 2012, aiming to develop more sustainable approaches to the treatment of drinking water in six catchment areas. Under the scheme, farmers were paid for a range of actions aimed at reducing diffuse pollution and run off of chemicals and nutrients into water bodies6. This scheme is currently under review by Scottish Water.

Case study - PES in Costa Rica

Costa Rica's government-led programme is probably the most iconic example of a large-scale publicly coordinated PES scheme7. It was created by law in 1996, which provided the statutory basis for payments and established the National Fund for Forest Financing. The scheme is a combination of regulations, which prohibit certain actions including cutting primary forest, and incentives (via 5-year contracts) for additional actions including reforestation and agroforestry.

This scheme focuses on the provision of four ecosystem services: carbon sequestration, biodiversity protection, water regulation and landscape beauty. A 'conservation gap' analysis was used to focus funds on unprotected, vulnerable forest or priority areas for new forest.

The scheme has been financed mainly by allocating revenue from a fossil fuel tax. Money has also been raised from international organisations including the World Bank and Global Environment Facility, and agreements with private companies in Costa Rica, including agribusiness, hydropower producers and water suppliers.

The programme has been popular with landowners, with large areas enrolled, but is oversubscribed and underfunded. There is some evidence that it has prevented deforestation, but one of the weaknesses of the scheme is the lack of evidence as to the extent it has successfully delivered specific ecosystem services.There is an assumption that increases in forest cover increase biodiversity and water quality, but the exact relationship is not always clear7.

The CAP and public goods

The CAP was created in post-war Europe with a focus on stimulating food production. This has had benefits for food security and maintaining populations in remote rural areas1.

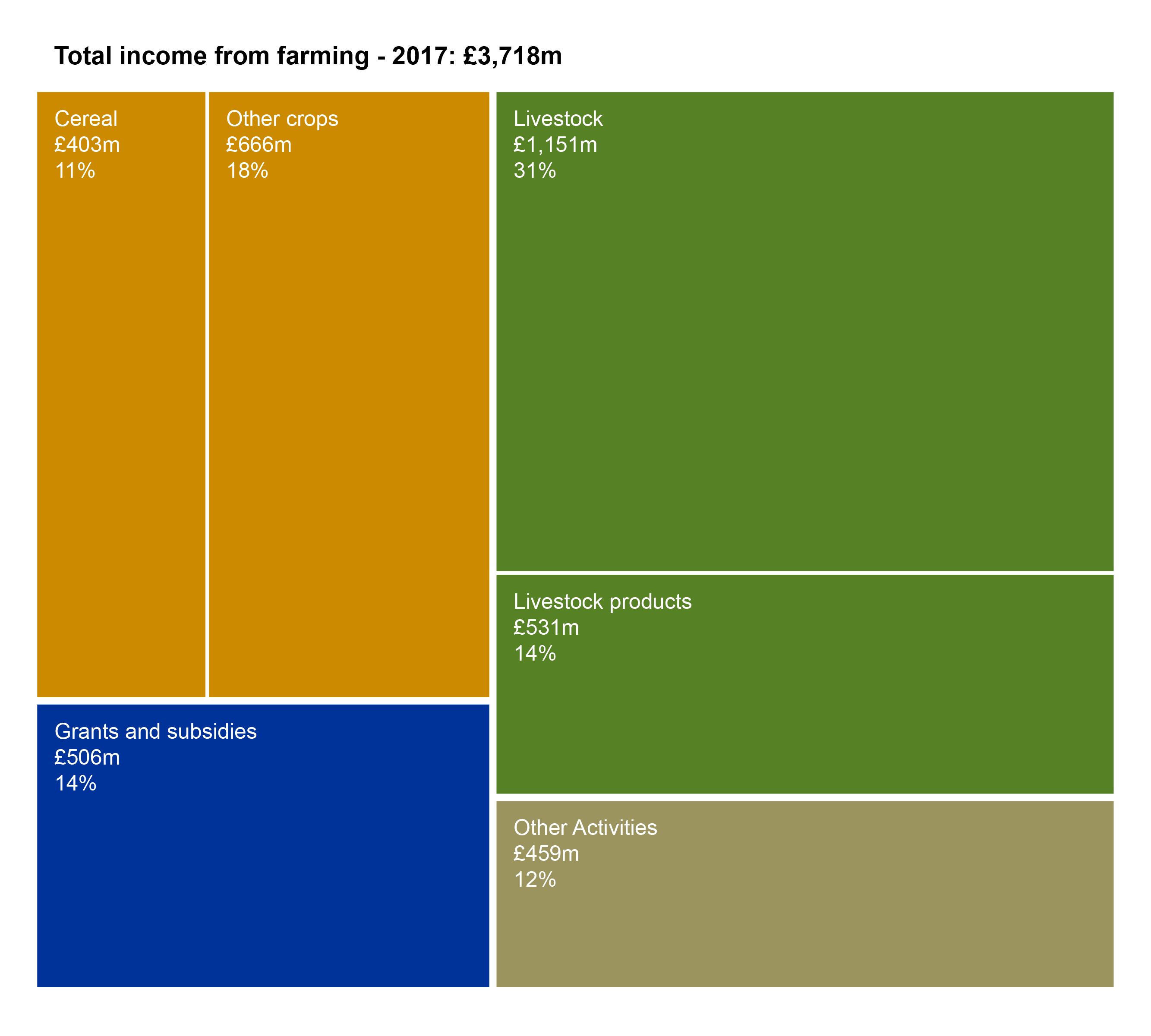

Public funding makes up a large part (14% in 2017) of farm income in Scotland (see Figure 3). In 2016-17 the average Farm Business Income was £26,400, but when support payments are excluded this changes to a loss of £14,900. If CAP payments are stripped out, around 75% of farms would fail to make profits2.

Reliance on CAP support varies by sector - for example the dairy, poultry, pig farming and horticulture sectors rely less heavily on public funding3. Farm incomes can also be highly variable depending on climatic and other factors. CAP support is therefore significant in terms of total income and protecting against volatility.

Despite the importance of CAP payments to farmers, the way they are structured (see Figure 4), particularly in terms of reaching their potential to deliver positive outcomes including public goods, has been criticised. Key criticisms are outlined in the following sub-sections.

Environmental impacts

One of the main criticisms of the CAP is that it has allowed or caused environmental damage1. Despite progress over the past thirty years through the implementation of agri-environment schemes, agricultural management as a whole is contributing to declines in farmland biodiversity, pollution of surface and groundwater, soil erosion, greenhouse gas and other emissions2.

One study of environmental impacts of UK agriculture estimated a net cost of £1.6-£2.1 billion to the UK3. The public benefit of agriculture was estimated at around £0.2-0.6 billion. However, the negative externalities identified (impacts on the environment and human health) were estimated at £2.3 billion.

Successive CAP reforms have had some success in mitigating negative impacts. Large-scale implementation of agri-environment schemes - payments for activities designed to provide environmental benefits - began in 1992. There is some evidence that these schemes have had positive impacts on conserving farmland wildlife4, for example they have supported recovery of species such as corncrakes5. However, even the most recent reforms have been criticised6 and measures likely to be most effective for biodiversity have had low uptake78.

Pace of agricultural innovation

Some believe that the CAP has slowed innovation in farming1. The NFUS recently stated that area-based support i.e. payments based on the amount of land under production, has incentivised farmers to maintain current practices rather than to change, restructure and become more productive2. Scotland's Rural College (SRUC) noted:

We believe that in order to unlock the true potential of Scotland's agricultural sector in the long run the ‘path dependent’ nature of agricultural support (where minimum disruption has been the preferred option over devising support schemes that deliver defined outcomes) has to be broken. In order to deliver a more resilient and prosperous agricultural sector that protects and enhances the environment, new and innovative approaches to agricultural support... need [to be] devised.

Bell, J. (2018, August 15). Response to consultation - Support for Agriculture and the Rural Economy - Post Brexit Transition. Retrieved from https://consult.gov.scot/agriculture-and-rural-communities/economy-post-brexit-transition/consultation/view_respondent?_b_index=60&uuId=1023087979 [accessed 22 October 2018]

Disproportionately rewarding larger holdings

As direct payments are area-based, those with larger holdings receive larger payments, and about 80% of CAP payments go to a quarter of EU farmers1. The think tank Green Alliance criticises the CAP for 'effectively redistributing money from low-income urban households to more affluent large landowners'2. The Scottish Government's Agriculture Champions recommend that payments should be capped per farm3. Scottish Land and Estates however opposes any form of cap in a new system4. In the Agriculture Bill, the UK Government proposes to delink payments from land area in England.

Current plans for post-EU agricultural support

Scotland and the other UK nations have started to set out policy plans for what will replace the CAP after EU exit.

Scotland

The Scottish Government published its Stability and Simplicity proposals for a rural funding transition period in June 2018. This document sets out proposals for an agricultural transition period to 2024, working on the assumption that an EU Withdrawal Agreement is implemented. There are no proposals for policy after 2024.

Unlike the Welsh Government and the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs in Northern Ireland, the Scottish Government has not requested Scottish clauses to be included in the UK Agriculture Bill, introduced to the UK Parliament in September 2018. This Bill and the controversy around whether it deals with matters with the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament are covered in a separate SPICe briefing.

The Scottish Programme for Government 2018-19 does not include plans for an Agriculture Bill, but plans for a Bill were announced in January 2019 in a debate on future rural policy. The Cabinet Secretary for the Rural Economy said that:

The purpose of the bill is primarily to provide the fundamental framework for the continuance of payments being made as well as to allow changes in future policy post-Brexit, should that occur1.

The Cabinet Secretary has indicated that post- 2024 Direct Payments, that currently fall under Pillar 1 of the CAP, are likely to continue in some sense:

The UK Government proposes to scrap direct payments to farmers for support for food production. I profoundly believe that that is wrong. I very much hope that Parliament will agree with me that such support, as well as support for the environmental role, is absolutely essential for the sustainability of our farming1.

This view regarding direct payments was re-stated in the debate in January but the Cabinet Secretary also recognised the debate around public goods:

I have been clear that this Government sees a continuing role for direct support, particularly for farming and food production. Our definition of public goods must encompass the multiple roles performed by farmers and crofters in food production and in stewardship of the countryside and our natural assets.3

Stakeholders are encouraging the Scottish Government to develop plans now for what will replace the CAP, in order to provide certainty for the sector. SRUC stated in August 2018:

It is critical for the Scottish Government to start thinking about the longer term future of farm, food and rural policy in Scotland to provide the sector with some clarity to help with business decision-making, whilst also ensuring Scotland is not left behind thinking and policy developments in England, Wales and Northern Ireland4.

Key recommendations from the Scottish Government's Agriculture Champions include:

There should continue to be an element of basic income support, but at lower levels;

Future funding must include a menu of schemes to boost efficiency, improve skills, and enhance natural capital and biodiversity, tailored to regional or sectoral needs;

Stewardship of the countryside should be a key part of future policy. Priorities must cover public goods such as wildlife and carbon sequestration, but could also include public-private benefits such as reducing waste and improving soils.

Other UK nations

SPICe has published briefings on post-Brexit plans for agriculture in the other UK nations and the UK Agriculture Bill. In summary:

In England, basic payments and greening support will continue during a transition phase from 2020, but the UK Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) may seek to make changes such as a maximum cap. After the transition period, basic payments will end and a new Environmental Management Scheme will be implemented based on PMfPG

In Wales, proposals for a 2020-2023 transition period have been set out with a phased withdrawal of basic payments. A new Land Management Programme is proposed from 2024 including an economic resilience scheme and a public goods scheme

In Northern Ireland it is proposed that a regime similar to the CAP will continue until 2022. From 2022, funding may be progressively reduced from area-based payments to other options, such as farm income insurance measures and environmental payments. It is proposed that some level of basic payment will continue.

UK Funding guarantees and policy principles

There is currently little clarity regarding funding levels for agricultural support and environmental programmes after Brexit. There seems to be a guarantee to provide the same total funds for 'farm support' until 20221. Questions remain over the meaning of 'farm support' and what this means for rural development and agri-environment schemes. There is little clarity on what funding will be available after 2022 and how it will be allocated across the UK. A review of funding has been promised, and Michael Gove stated during the second reading of the Agriculture Bill that:

the generous—rightly generous—settlement that gives Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales more than England will be defended.

The UK Government has initiated an independent review into the factors that should be considered to make sure that funding for farm support is fairly allocated. Defra states that “Funding allocations have already been made up to 2020, so the review will make recommendations from 2020 to the end of this Parliament.”2

Policies that PMfPG could support

There are a range of policy objectives, domestic targets and international obligations that the Scottish Government is committed to, that a PMfPG scheme could potentially be designed to support. The Scottish Government has committed to at least maintaining environmental standards after EU exit 1, as has the UK government even in the event of no deal 2.

After EU exit, the UK will still be a party to multilateral environmental agreements such as the UN Convention on Biological Diversity and the Paris Agreement on climate change. It is widely assumed that, although several are 'mixed agreements' ratified by both the UK and the EU, they will continue to apply to the UK3. During any transition period, it is likely that the UK will have to abide by EU environmental regulations.

Sustainable Development Goals

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were published in 2015 and aim to address challenges relating to poverty, inequality, climate and environmental degradation. Scotland was one of the first countries to adopt these goals1 and they are embedded in the 2018 National Performance Framework (NPF). A set of 81 National Indicators are used to track progress under the NPF, several of which a PMfPG scheme could be designed to contribute to. They include 'access to green and blue space', 'carbon footprint', 'condition of protected nature sites', 'biodiversity', 'greenhouse gas emissions' and 'Natural Capital'.

Natural capital

The Scottish Government has committed to increase natural capital12. Ecosystem services originate in 'natural capital':

Ecosystem services are the flows of benefits which people gain from natural ecosystems, and natural capital is the stock of natural ecosystems from which these benefits flow. So, a forest is a component of natural capital, while climate regulation or timber might be the ecosystem service it provides3

This concept allows for the valuation of these assets so that they can be more effectively considered in decision-making. Scotland has a Natural Capital Asset Index, launched in 2011 by SNH. A natural capital indicator was developed from this in 2016 and now features in the National Performance Framework. A PMfPG approach in an agricultural support system could align itself with these indicators.

Climate change

The Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 set a target of reducing net Scottish Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions to 80% of 1990 levels by 2050. A new Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill was introduced on in May 2018 which sets a new 2050 target of 90% emissions reductions as well as providing Scottish Ministers with a duty to set a target of net-zero as soon as 'the evidence becomes available' that it is feasible.

The contribution of Scottish agriculture to GHG emissions and the opportunities to reduce on-farm emissions are set out in a recent SPICe briefing. Agriculture currently comprises around 26% of Scottish GHG emissions1. Since 1990, emissions from the sector have fallen by 14%, but the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) consider that 'there has been little recent progress in reducing agricultural emissions in Scotland'2 and agriculture is likely to overtake transport to become the largest source of GHG emissions3.

Agriculture is likely to be one of the sectors that always remains a net GHG source1, but this can be offset by sequestration. A PMfPG scheme could encourage activities that increase natural carbon sinks via tree planting and peatland restoration56. The RSPB and CCC have both recently produced reports with recommendations for how emissions from agriculture can be reduced53.

The CCC has also called for more adaptation measures to improve agricultural resilience to climate change5 i.e. measures that reduce vulnerability to risks such as extreme weather or new pests and diseases.

Biodiversity

The Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004 commits Scottish Ministers to designating a Scottish Biodiversity Strategy. The current strategy is the 2020 Challenge for Scotland's Biodiversity1 and sets out Scotland's response to the European Biodiversity Strategy for 2020 and the Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) Aichi Targets.

An SNH report in 2017 found that, in Scotland, of the 20 Aichi targets, 7 are on track to be met by 2020, 12 are showing progress but will be missed and 1 (funding for biodiversity) is moving away from target. These targets will have expired by the time any new support system is in place but they are due to be updated in 20202.

Agri-environment schemes under Pillar 2 of the CAP can be effective at maintaining biodiversity, however many species in Scotland are still in decline, including upland bird species which underwent strong declines between 1994-20153.

Biodiversity in a PMfPG scheme could be promoted via a range of approaches including agri-environment schemes and organic farming or set-aside (leaving areas of land uncultivated). Scottish Environment LINK have suggested this could be developed through commitments to introduce a National Ecological Network 4, as set out in Scotland's Biodiversity Route Map5 and the National Planning Framework6.

Ammonia, diffuse pollution and water quality

In 2015, agriculture was responsible for 87% of Scottish ammonia emissions, due to manure and slurries and to a lesser extent fertiliser use1. A SPICe briefing on air quality in Scotland details the sources and effects of ammonia emissions on air quality. Optimising fertiliser use and improving slurry management above regulatory requirements could form part of a PMfPG scheme and help to meet commitments in the Cleaner Air for Scotland: Road to a Healthier Future strategy2.

Rural diffuse pollution, largely caused by run-off from farms and other land uses, is one of the key pressures on water quality in Scotland. Whilst water quality in Scotland is relatively good compared to other nations, 34% of water bodies and 17% of protected areas are not in good condition. A PMfPG system could incentivise measures that reduce pressures on water bodies above regulatory requirements, such as tree planting to buffer water bodies3.

Access to countryside and maintenance of landscape

Enjoyment of the countryside and landscape are public goods, especially in Scotland due to the 'right of responsible access' introduced by the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. Scotland's Land Use Strategy states that one of the principles for sustainable land use is that outdoor recreation opportunities and public access to land should be encouraged, given their importance for health and wellbeing.

Paying land managers to facilitate access to the countryside and enhance the landscape could form part of a PMfPG scheme. Conserving 'rural landscape of historical interest' is explicitly built into Italian rural development policy to encourage agro-tourism, which is widespread in the country and provides income to land managers1.

Forestry

Alongside agriculture, forestry is the other major land use in Scotland in terms of area. Forests and woodlands cover around 18% of land in Scotland1. The sector is worth almost £1 billion per year and employs over 25,000 people2. As well as its economic contribution, forestry is important in the fulfilment of Scottish commitments on climate change and biodiversity. As such, the Scottish Government 'is committed to promoting and developing modern sustainable forestry' 1 and has set ambitious targets for woodland creation (to plant 15,000 ha per year by 2024), with an aim of increasing the nation's woodland cover to 21% by 2032. There is currently a concern about low levels of new forestry planting4, with only 4,800 ha planted in 2016/175.

However, more recently Forestry Commission Scotland has stated "In the current year, we have approved applications for more than 10,000 hectares, and we have the budget cover to fund those."6

Funding is provided for the creation and management of woodland through the SRDP, and the Government held a consultation on a Forestry Strategy for Scotland in November 2018. Alongside agriculture, forestry will be an important consideration in any land-use policy framework post EU exit.

Designing a PMfPG scheme

As demonstrated by the CAP, there are significant challenges with designing any agricultural or land-use support system, potentially with a view to delivering multiple policy objectives, and a need to consider the potential for perverse and unwanted outcomes. A PMfPG scheme could take many different forms or potentially be integrated into a broader framework.

There are many examples of how PES schemes work around the world, using either private or public money or both. Whilst lessons can be learned from their successes and failures1, any scheme in Scotland would have to take account of the unique environmental, social and economic context. The following sections briefly discuss some key areas of consideration.

The Scottish Government have stated that the transition period between CAP and any new policy is anticipated to last until 2024 and is explicit that new initiatives will be avoided during this period. However, the Agriculture Champions state that:

We recommend that government, in consultation with industry, must use the transition period to experiment and to pilot the new approaches that will be needed. In the absence of new money, this should be funded by capping payments at a much lower level than at present2.

Integrating land-use policy?

Public goods are not only the possible priority for land-use policy, and there may be competition for resources with other priorities such as supporting food production and maintaining rural populations1. Also, whilst agriculture uses the majority of land in Scotland, it is not the only land use relevant to a PMfPG approach, as farmers are not the only land managers who can provide public goods.

Stakeholders have called for a integrated approach to land use policy after EU exit. Scottish Land and Estates have said:

Scottish Land & Estates would like to see an integrated approach to land use that aims to get the most out of the land to the benefit of all. For too long land management has been undertaken through a sectoral approach that sees farmers, foresters, gamekeepers and conservationists operating separately. Our policy frameworks should help break down the silos rather than reinforce them.

Scottish Land and Estates. (n.d.) A new direction for Scottish land management. https://www.scottishlandandestates.co.uk/sites/default/files/library/A%20New%20Direction%20for%20Scottish%20Land%20Management.PDF.

The Land Use Strategy 2016-2021 emphasises the need for integrated land-use policy. In 2015, regional land use projects were piloted in Aberdeenshire and the Scottish Borders on land uses such as agriculture and forestry which fall outside the planning system. These projects showed that it is possible to plan for multiple benefits and economic activities including agriculture, conservation, forestry, agriculture and rural development.

The following sub-sections outline some policy objectives that could form part of a broader, integrated land-use policy framework in combination with PMfPG.

Improving productivity and managing risk

Whilst the production of affordable and healthy food provides a public benefit, food does not come under the definition of a public good, therefore any continued support for food production post EU exit would be in addition to a PMfPG scheme.

In Scotland there are two CAP payment schemes coupled to production, the Scottish Suckler Beef Support Scheme and Scottish Upland Sheep Support Scheme as well as other payments that could be thought of as supporting production, such as the Knowledge Transfer and Innovation Fund. The Agriculture Champions suggest that there should be a major focus on polices and schemes to support production efficiency, including advice and training, knowledge transfer and technology such as electronic identification1.

Productivity measures are a key component of NFUS' proposals for agricultural policy after EU exit:

Productivity measures are required to increase the viability and competitiveness of all sectors through

investment in innovative agricultural practices and technology

increased knowledge exchange

improved technical and managerial skills

greater uptake of risk management strategies

better animal health and welfare

more effective resource use

positive environmental stewardship2

Agriculture is also particularly prone to business risks, which a future support framework may seek to ameliorate. SPICe has produced a briefing that discusses risk management in agriculture and what policies are in place in other countries.

Maintaining rural populations

The Scottish Government set out an aim to encourage population growth to support the sustainability of rural communities in its Purpose Targets.

According to research by the James Hutton Institute, the Sparsely Populated Areas of Scotland will lose more than a quarter of its population by 20461.

Under the current SRDP, there are two schemes that are aimed at maintaining populations in remote rural areas, the Less Favoured Areas Support Scheme (LFASS) and the New Entrants Scheme. The SRUC states, in relation to the LFASS, that:

It is certainly the case that support for activity in Scotland's disadvantaged areas is absolutely vital if the Scottish Government wish to maintain agricultural activity in these areas and the associated social, economic and environmental outcomes that the support delivers2.

This priority may be especially important for crofting counties, and the Scottish Crofting Federation has called for the reinstatement of a Crofting New Entrants Scheme to encourage younger people to take up crofting 3.

Some research has suggested that the greatest supply of ecosystem services could be secured by land sparing, where very high intensity farming with high inputs and high yields takes place in small areas and the rest of the land is used for ecological restoration, rather than land sharing, where low-input low-output farming takes place over a larger land area4. This research only takes environmental costs and benefits into account and not social factors - highlighting the potential for tensions between social and environmental objectives if they are not considered together.

Connecting consumers and producers

Nourish Scotland have drawn attention to the importance of any support system to fulfilling the aims of the Scottish Government's Good Food Nation policy1, highlighting the reliance of a healthy and sustainable food system on well-organised land use and vice-versa2. They urge that any policy should take the entire food system into consideration. Part of the Scottish Government's Good Food Nation Policy, is to try and connect people with their food and how it is produced1.

This has been a focus of Italian agricultural policy through agro-tourism and social farm schemes which aim to get people who would not normally experience agricultural activities onto farms4.

Voluntary measures, regulation and cross-compliance

A PMfPG scheme would need to determine which activities were voluntary and whether and how they relate to compliance with any regulations. One of the key characteristics of a PES scheme is ususally that it provides incentives for actions over and above any regulatory baseline and for providing additional public goods.

The NFU, in setting out their framework for agricultural policy after Brexit, says that 'Future environment schemes should be voluntary, catering for all levels of ability, knowledge and skills of land managers' 1.

Currently, Pillar 1 payments under the CAP are conditional on a basic level of cross-compliance, i.e. farmers have to adhere to some regulations in order to receive them.

The Scottish Government has made policy commitments to maintain environmental standards after EU exit2, suggesting current standards set in legislation will be maintained. Areas where it has been suggested that current standards could be augmented include mandatory measures to address pest management, soil restoration and carbon sequestration3.

Governance structures required

There are already governance structures in Scotland that implement and support the CAP, as Member States individually design and implement it with oversight from the EC. The Scottish Government's Rural and Environment Science and Analytical Services Division conducts and funds research on the design and evaluation of agricultural policy, partly through SEFARI and the Centres of Expertise. The Rural Payments and Inspections Division makes CAP payments and conducts inspections to ensure compliance.

As a largely devolved area, it is considered likely that responsibility for creating any PMfPG scheme will lie in Holyrood, but exactly which parliament has which competencies will depend on agreement about joint frameworks1.

A successful system is likely to require well-resourced institutional capacity in order to ensure that the desired public goods are being delivered. Weak institutional capacity has been identified as a risk to any post-Brexit agricultural policy as it could result in 'simpler less effective schemes with reduced oversight'2.

Engagement, advice and training

A scheme that shifted land-management priorities significantly would require buy-in from land-managers to be effective. The farming community has sometimes been broadly characterised as being resistant to changes that give higher priority to other benefits over food production1. There are examples however of farmers voluntarily engaging in sustainable and nature-friendly farming activities, sometimes as part initiatives such as the Nature Friendly Farming Network, Farming for a Better Climate and Linking Environment and Farming.

A successful PMfPG scheme may also require more investment in training and specialist advice services as well as knowledge transfer and exchange, to enable information and experiences to flow easily to land managers23456. Research has demonstrated that training and encourages agri-environmental management7. There are existing training and advisory schemes that could be scaled-up to deliver this, including the SRDP's Farm Advisory Service (FAS) , SEFARI Gateway and Farming for a Better climate.

SRUC states:

There remains ... a need for face-to-face advice due to the greater effectiveness in spurring participants in to action and not least the wider social benefits for often isolated farmers and crofters. It is essential that... advice... respects the views of farmers and crofters but is willing to challenge them to think differently about their business...2

Other aspects that could be considered in designing or enhancing advice services include:

Supporting innovation in food production. Currently, only around 27% of Scottish farmers have formal agricultural training9. Encouraging professional development in the agricultural sector is a priority for the Scottish Government9.

Whole farm plans. In Costa Rica, landowners must have a management plan to receive payments11. Work commissioned by Crown Estate Scotland has shown that it is possible and beneficial to apply the Natural Capital Protocol to draw up whole farm plans, which would be useful for future payment schemes12.

Cooperation between land managers. Many public goods are supplied on scales above that of single farms, so their successful provision may depend on coordination between land managers (with potential for other benefits).

Peer-to-peer knowledge exchange13 including demonstration farms, local 'champions' or meetings. This could build upon the services provided by the Scottish Rural Network, Rural Innovation Support Scheme, the Knowledge, Transfer and Innovation Fund and SEFARI Gateway.

New entrants. The farming community has an ageing demographic and new entrants face a challenging environment to get started9.

Integration of advice for land managers to reduce complexity of engaging with multiple sources, or to help identify complementary actions.

Evidence and indicators of success

One of the primary conditions for a successful PES scheme is conditionality, i.e. payments are only made upon the provision of the service in question. Measuring outcomes and ensuring that the intended public goods are actually delivered can be difficult. Challenges arise in the definition, valuation and measurement of stocks and flows of ecosystem services1 - for example it may not be straightforward for a farmer to demonstrate or measure the specific impacts of their activities on emissions, or flood mitigation, or biodiversity.

Transaction costs of PES schemes (i.e. the costs of administering a PES scheme) can be significant2 and mechanisms of measuring and monitoring delivery of ecosystem services are a large part of this. In some cases, such as carbon sequestration, it can be relatively easy to measure performance by looking at tree cover and tree size as a proxy, but the complexity of hydrology makes it very difficult to establish cause and effect in a natural flood risk management project for example3. However, there is expertise in Scotland in the measurement of ecosystem services, in relation to hydrology for example in the Centre of Expertise for Waters.

It may not be necessary in a PMfPG scheme to directly measure or monitor delivery of public goods, if there is sufficient evidence that the actions implemented will deliver results, for example, that allowing native grasses to grow on a patch of land increases biodiversity. Resources, such as the website Conservation Evidence are also emerging and developing to collate this evidence and make it accessible. In Scotland, organisations such as SEFARI, the James Hutton Institute and SRUC conduct research into how to deliver multiple benefits from Scottish landscapes.

Potential payment structures

Currently, CAP payments are to some extent based on the level of support that a recipient has received in the past. Some have suggested moving away from using these historical entitlements to set future payment levels1, which may happen if basic payments are reduced.

Under a PMfPG scheme payment levels would usually seek to reflect the cost of any actions, and potentially also the value of the public goods delivered, although the latter is more complex to define2 3. Prices will have to be sufficient to provide an incentive to farmers but may be constrained by the budget available (Figure 2).

Key considerations and options for payment structures include:

The range of options available to land managers. This could be different in different areas if regionalisation is used.

Whether activities are mandatory or voluntary. The NFU and NFUS4 support all environmental schemes being voluntary, although some environmental groups suggest mandatory baseline actions to be eligible for any support.

Competitive or non-competitive. If there are insufficient resources to meet demand to fund activities, competition for funding may be required for some levels of payment.

Inclusion of capital grants for investments in infrastructure and technology that have large upfront costs. There is currently a Crofting Agricultural Grant Scheme and a Small Farms Grant Scheme in Scotland.

Length of contracts. Lots of public goods are delivered over long timescales. For example, forestry and habitat restoration may not show measurable carbon and biodiversity benefits for years. In light of this, long-term contracts may be required.

Capping. A cap on payments has been proposed by the Agriculture Champions, and the Scottish Government has consulted on this5.

In terms of payment structures, the Scottish Wildlife Trust has proposed a four-tier hierarchy of regulation and associated support payments for natural capital maintenance, enhancement, and restoration in the agricultural sector6.

Tier 1: Regulation

All land managers must comply

No payments made for complying

Tier 2: Natural Capital Maintenance Payments

Area based available to all land managers for meeting mandatory criteria

Must undertake whole-farm reviews

Tier 3: Natural Capital Enhancement Payments

Non-competitive additional area-based payment available to all farms

Applicants can choose from a range of options

Tier 4: Natural Capital Restoration Payments

Competitive additional payment designed to deliver public-good priorities

Priority habitats to be identified at local level by opportunity mapping

Payment for actions vs payments for results

Under the CAP, the reward mechanism for agri-environment measures has been 'action-oriented payments'. This means farmers are paid for carrying out certain practices rather than for outcomes. There are concerns that these schemes do not provide the desired environmental benefits, value for money or long-term cultural change1. There have been a range of trials across Europe of results-oriented schemes including two by Natural England2 and a scheme in Ireland3. The Irish Government have recently implemented a suite of results-based schemes under the EC's EIP-AGRI Programme4.

Advantages and disadvantages of basing payments on results are summarised below.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

|

|

A PMfPG scheme could also be a hybrid of the two approaches with a base payment to compensate for actions, and a bonus payment for outcomes6.

Regional variation

National priorities for land use are set out in the Land Use Strategy and potential national priorities for a PMfPG scheme are discussed in above sections. However, it has been suggested that it is unlikely that a one-size-fits-all national PMfPG scheme will deliver the best outcomes or be palatable to all stakeholders1. NFUS have said that any national delivery framework for environmental measures "needs to be based on local priorities which reflect local agricultural practices"2. SRUC also support regionalisation1.

Furthermore, whilst a range of public goods can be delivered from the same land it may not be possible to maximise provision of all public goods at the same time4. For example, the maximum possible amount of carbon sequestration in an area may be achieved by a monoculture of non-native trees, but research has shown that there is a trade off in ecosystem service provision between Sitka spruce plantations for example and multifunctional landscapes5. An approach is therefore required to help identify what public goods should be targeted in different areas.

There have been two regional land use pilot projects commissioned under the Land Use Strategy, in Aberdeenshire6 and the Scottish Borders7. These pilots mapped land uses, predicted future changes in response to likely drivers including climate change and policy changes, and analysed where change could lead to multiple benefits. Despite difficulties including lack of data, these pilots provided proof-of-concept that planning at this level is possible.

Factors that could be taken into account in regional planning include the desires of the local community, the suitability of the land for certain uses, existing land practices, potential future changes due to climate change and other factors, and local features including protected areas. Scottish Environment LINK8 and SWT9 have suggested that environmental priorities could be mapped and integrated into land-use policy using a National Ecological Network.

Potential for co-financing

Funding for Payments for Ecosystem Services schemes can come from a range of sources:

Public payment schemes i.e. 'public money for public goods'

Self-organised private deals

Open trading of environmental credits

Eco-labelling or certification

Public money may be the only feasible source of funding (or adequate source of funding) for true public goods1. Research has also shown that the significant transaction costs involved in schemes designed to provide multiple public goods means that governments are better suited to coordinating them2.

There may be possibilities however for a hybrid system where some goods are paid for with public money and others with private money. Defra commissioned 16 pilot PES schemes between 2012-2015 and identified a range of potential private buyers and their motivations:

Water companies where activities reduce end-of-pipe treatment costs;

Recreational visitors who benefit directly from the maintenance of a landscape visit;

Local tourism businesses who use the landscape to advertise to potential visitors;

Developers who may have to offset Greenhouse Gas emissions;

Businesses to fulfil corporate social responsibility commitments;

Consumers and local communities3.

The pilots raised around 50% in co-funding from the private sector and NGOs3 (see also the Costa Rica case study above where co-financing was raised from international organisations and private businesses). A PMfPG scheme could be supplemented by income from certification schemes or branding that communicates benefits, including organic or high nature value farming5.