Alternative Housing Tenures

This briefingconsiders the alternatives to the established tenures of Owner Occupation, Private Rent and Social Rent in Scotland.

Executive Summary

This briefing has been prepared by SPICe, in conjunction with with Dr Gareth James from the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE), Shelter Scotland, Scottish Federation of Housing Associations (SFHA), Association of Local Authority Chief Housing Officers (ALACHO), Scottish Futures Trust and Rettie & Co.. There are a series of blog posts, available on the CaCHE website, written by those who participated in the discussion.

The briefing covers alternative housing tenures, which are additional to the three established tenures: owner occupation, private rent and social rent.

The emergence of alternative tenures is set within the context of changing housing markets and new categories of housing need in Scotland. The effects of the Global Financial Crisis are still being felt and will continue to influence Scotland's housing market for years to come.

Home ownership has become increasingly unaffordable for many, especially the young. The available stock of social rented housing has declined in absolute terms since 2000 leaving many with no option but to rent privately. And private rents are increasingly unaffordable for those on modest incomes who are not eligible for social housing and cannot afford to buy.

The Scottish Government has attempted to address these issues in several ways, including through the Affordable Housing Supply Programme (AHSP). However, it has already stated that it will be a challenge to extend the same level of spending on affordable housing into the next parliamentary session (from 2021). The briefing therefore looks at progress with alternative tenures to date and the potential for further development.

The emerging evidence, gathered from a round table discussion, where representatives of the above organisations and others met to debate the subject of Affordable Housing Tenures, as well as other published sources, suggests that alternative housing tenures, like Build to Rent (BTR) and Mid-Market Rent (MMR), can offer tenants a good standard of accommodation and professional management services, whilst allowing housing providers to be flexible in managing their stock. Alternative housing tenures can also help to meet demand and have the potential to meet a wider range of housing need in Scotland.

The briefing also considers the use of Local Housing Allowance (LHA) rates in setting MMR rents and highlights the longer-term subsidy consideration and evidencing needs for demonstrating the impact of existing schemes.

Figure 1 (below) outlines the types of alternative tenures that will be discussed in this paper.

| Type of Tenure | Target Tenant/ Owners group | Number of Scottish Government Supported Completions 2011/12-2017/18 | Scottish Government expenditure 2011/12-2017/18 | Completions with no Scottish Government subsidy |

| Build to Rent (BTR)(owned by the investor and specifically designed for private occupation). | Those who can afford to pay market rents - perhaps with experience of living in high quality, purpose built student housing - who are not ready to buy a home or are still saving for a deposit. | No figures available. | No figures available. | 564 |

| Mid Market rent(Private tenancy mainly provided by RSLs and their subsidiaries). | Typically, those who would not qualify for social housing but cannot afford to pay a market rent or buy property. Eligibility determined by income levels; maximum joint income of around £45K. Rent levels around 30% lower than market rents. | 5,496i | £174.1m grant£102.5m loans | No figures available |

| Affordable home ownership(mainly shared equity within the AHSP) | Those who want to buy property and cannot afford a large deposit or full mortgage. Includes open Open Market Shared Equity Scheme. | 11,495(2011/12-2017/18). | Figures available from 2012/2013ii£422,699iii | |

Introduction and Context

The Scottish Government (2011) outlined the need to increase supply across the housing system in each of the three established tenures: owner occupation, private rent and social rent.1 At the same time, however, it recognised the growing numbers of people whose needs were not being met by any of these tenures.

This briefing has been informed by a roundtable event co-organised by the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE), Shelter Scotland, Scottish Federation of Housing Associations (SFHA), Association of Local Authority Chief Housing Officers (ALACHO), Scottish Futures Trust and Rettie & Co., to discuss the role of alternative tenures and delivery/funding models, and how best to provide choice of tenure, within the wider context of delivering more affordable housing in Scotland.

Alternative housing tenures are, at least in part, a response to the emergence of new categories of housing need in Scotland, following the Global Financial Crisis.

The Round Table Event and Related Blog Posts

The roundtable event was held on 3 April 2019 and was attended by around 25 participants from across the Scottish housing sector. Following the event, four blogs, from which this briefing draws, were produced for the CaCHE website. These were:

Professor Moira Munro, CaCHE Knowledge Exchange Lead for Scotland: Approaches to delivering alternative tenures1

Karen Campbell, Scottish Futures Trust: Options for Affordable Home Ownership2.

Dr John Boyle, Director of Research for Rettie & Co.: Build to rent is here to stay3.

Dr Richard Jennings, Director Castle Rock Edinvar Housing Association: Flexibility and Adaptability, Mid-Market Rent and the Supply of Affordable Housing.4

The Legacy of the Global Financial Crisis

The effects of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), which began in 2007, are still being felt over a decade later, and will continue to influence Scotland's housing market in the years to come. Among the many outcomes of the GFC is the emergence of new categories of housing need in Scotland, not to mention the rest of the UK.

Because of the GFC, new housing supply across all sectors in Scotland was reduced. New starts, the number of properties starting to be built, fell by almost 50% from a high of 26,584 in 2007 to a low of 13,385 in 2011, and completions, the number of new properties completed, fell by almost 42% over the same period. Sales volumes fell by 55% between 2007 and 2009.1

The introduction of Help to Buy (HTB) in 2012, improved economic growth from 2013, and the Affordable Housing Supply Programme (AHSP) helped to reverse these downward trends. However, as of 2017, new starts were still down 26% on 2007, new completions were down 31% and sales volumes were down by one-third.

House prices doubled in Scotland between 2001 and 2007 but remained relatively stable between 2007 and 2012. Average house prices have since increased almost every year since 2013 and are projected to continue rising.2 Wages, however, have not kept pace with house prices. Flat earnings, rising house prices and high deposits have combined to put home ownership out of reach for many potential buyers, especially young people.

The available stock of social rented housing has declined in absolute terms since 2000, reducing rental opportunities other than in the private rented sector (PRS). These challenges in other parts of the housing system have increased demand for private renting in Scotland.

Between 1999 and 2017, the percentage of Scottish households living in the PRS has increased threefold, from 5% to 15%. The drift of young people to the PRS is a key trend in the growth of the sector over the past 10 years, and this could continue, given affordability issues.

There is however a lack of information on accurate and verifiable rents in the PRS in Scotland.3 Analysis shows significant rent increases, especially for Glasgow and Edinburgh.4 Rents increased by 1.2% annually in Glasgow between 2008 and 2013, jumping to 4.3% per year for the period 2013-18. In Edinburgh, the figures are 1.8% and 5.9%, respectively.

Rising rents have made the PRS increasingly unaffordable for households on modest incomes who are unlikely to be a high priority for social housing and who are not able to afford owner occupation. This group has been referred to by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as "the squeezed middle" and may constitute a new category of (unmet) housing need in Scotland.5

The Affordable Housing Supply Programme and Housing to 2040

Through the More Homes Scotland approach, the Government has introduced measures to support its aim of increasing the supply of good quality, affordable housing across all tenures in Scotland, including homes for intermediate rent. These measures include the Affordable Housing Supply Programme (AHSP) which, the Scottish Government state, is backed by £3.3 billion. This is made up from grants from the Scottish Government, loans and the Transfer of Management of Development Funding (TMDF) provided to the Local Authorities in Glasgow and Edinburgh. By the end of the current parliamentary session (2016-2021), the AHSP aims to deliver 50,000 affordable homes, including 35,000 for social rent and an unspecified number for intermediate rent and affordable home ownership.

A recent analysis of all 32 council Strategic Housing Investment Plans (SHIPs) suggests that these targets are capable of being reached, but more research will be needed to understand the distribution of new homes and the extent to which they meet current and future need.1

Whatever Scotland's post-2021 housing need may be, the Scottish Government has already said that it will be a challenge to maintain the current level of spending on affordable housing supply in the next parliamentary session (2021-2026).2 It estimates the cost of delivering a further 50,000 homes over the lifetime of the next parliament will be £4 billion and this will likely not be enough to address fully Scotland's housing need.

Despite the challenge, the Scottish Government states that housing

has a vital role to play in meeting many of our aspirations, including eradicating child poverty and homelessness, ending fuel poverty, tackling the effects of climate change and promoting inclusive growth.

Scottish Government. (2019). Housing to 20140: stakeholder engagement report 2018. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/housing-2040-report-stakeholder-engagement-2018/pages/2/ [accessed 09 July 2019]

It is possible, therefore, that as it develops its vision for housing to 2040, the Scottish Government may focus on developing new housing supply initiatives that can be delivered with little or no subsidy.

Build to Rent.

This section looks at the option of Build to Rent (BTR). It deals with:

What is Build to Rent

BTR is a subset of the private rented sector (PRS). It is the provision of purpose-built private rented accommodation by investors and developers. Planning guidance describes it as follows:

Build to Rent housing offers purpose-built accommodation for rent within high-quality, professionally managed developments.

It can take on a variety of forms, from high to low density developments, and range from homes that appear indistinguishable from those on the market for purchase, to schemes which have greater similarities to purpose-built student accommodation.

Typically, residents will have access to wider on-site amenities that extend beyond the traditional boundaries of an individual housing unit. BTR developments may include the conversion of existing buildings as well as new build.

Scottish Government. (2016). Affordable Housing Supply Outturn Report 2014-2015. Retrieved from https://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20170401150942/http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Built-Environment/Housing/investment/ahip/ahsp-outturn-report-2013-2014 [accessed 29 May 2019]

BTR homes can therefore take the form of large, high density city centre developments, as well as low density family homes for rent in suburban areas. Developers build for renting rather than for sale and often offer professional on-site management and access to shared, communal facilities and on-site amenities.

Monthly rents also vary. Many BTR schemes cater for more affluent households and young professionals and, in these cases, monthly rents can be above the market rate. BTR developments can include family properties as this is a scheme designed to be open to all household types and budgets. BTR developments may therefore include a mixture of houses and apartments for rent, hotel rooms, student accommodation, office space, and, occasionally, some homes for sale. Again, this varies from one development to another.

Many housing industry professionals now see [BTR] as a key part of the solution to the UK's housing crisis. Such accommodation is highly popular in parts of Europe and the US and its influence is now growing in the UK too.

Boyle, J. (2019). Build to Rent is here to stay. Retrieved from https://housingevidence.ac.uk/options-for-affordable-home-ownership/ [accessed 09 July 2019]

BTR homes have been developed in England and in Scotland, specifically in Aberdeen, Glasgow and Edinburgh. According to research, over 140,000 BTR homes were completed, under construction or in planning across the UK at the end of Q1 2019, an increase of 13% on the same time the previous year.19

Supply of BTR

BTR is still an emerging tenure in Scotland compared to the rest of the UK.

There has been significant growth of the Scottish Build to Rent (BTR) sector in Scotland over the last year, as well as the increasing appetite of investors to put their money into Scottish housing: the current pipeline represents less than 2% of all PRS households in Scotland, [whereas] the UK as a whole is now at more than 3 times this level and London is nearly 5 times

Boyle, J. (2019). Build to Rent is here to stay. Retrieved from https://housingevidence.ac.uk/options-for-affordable-home-ownership/ [accessed 09 July 2019]

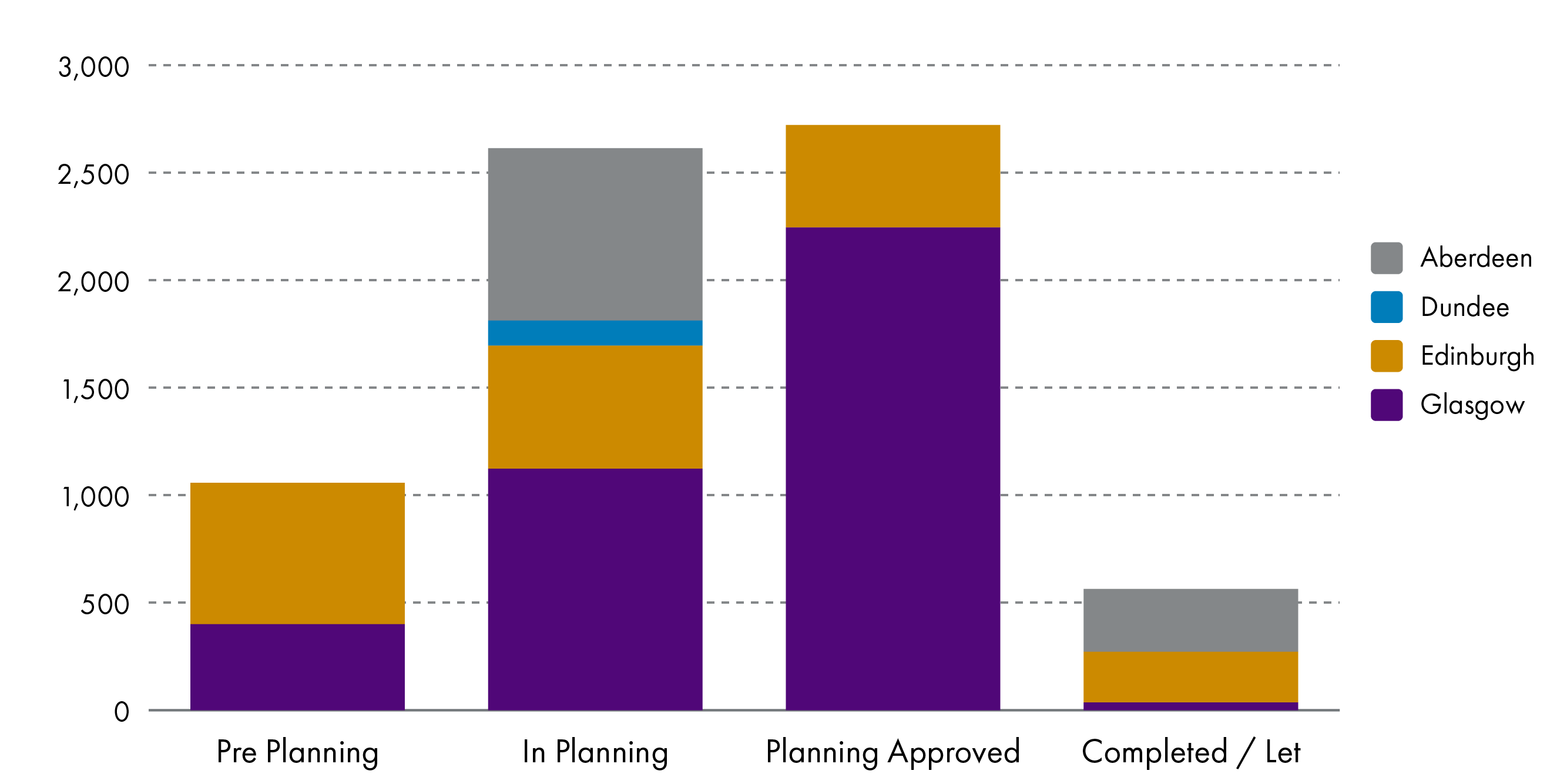

Figure 2 shows that there are currently 564 BTR homes completed and let in Scotland. The bulk of these are in Aberdeen and Edinburgh. There are a small number of BTR homes in Glasgow, and none yet in Dundee.

Aberdeen was the first Scottish city to see the arrival of BTR. The Forbes Place development was launched in September 2016. This development, which is owned by Lasalle and managed by Dandara Living, is a mixed community of 292 apartments and town houses. These homes are fully-furnished, with high-speed internet connections, and are serviced by an on-site management team.

There are 236 BTR homes in Edinburgh, spread across three developments: 48 apartments at Springside, 113 at Lochrin Quay, and 75 at McDonald Road.

The Springside development is in the Fountainbridge Masterplan area. It received planning permission in 2016 and was purchased by Moda Living/Apache Capital in early 2017. There are plans to deliver over 500 BTR homes on the site.

Lochrin Quay is also located in the Fountainbridge Masterplan area. Completed in 2017, the site was developed by GSA, a property development company in the private rental and student accommodation sector and purchased by Aberdeen Standard Investments (ASI) for £27.5m. The development is now managed by JLL and includes studio, 1, 2, and 4-bedroom apartments.

McDonald Road by Kingsford Residence is a conversion of the former Broughton High School building. It offers 1 and 2 bedroom apartments.

There are 36 BTR homes at Candleriggs Court in Glasgow. The development offers 1, 2 and 3 bedroom apartments, underground parking, high-speed internet, and a private internal atrium for use by tenants. All properties are currently rented.

| City | Development | Unit type | Monthly rent (£/pcm) |

| Aberdeen | Forbes Place[1] | Studio | 599 |

| 1-bed apartment | 705 | ||

| 2-bed apartment | 799 | ||

| 3-bed townhouse | 1,450 | ||

| Edinburgh | Lochrin Quay[2] | 1-bed apartment | 1,313 |

| McDonald Road | 1-bed apartment | 1,045-1,295 | |

| Glasgow | Candleriggs Court | 1-bed apartment | 920 |

| 2- 3 bed apartment | 1325 |

[1] https://www.forbesplace.com/faq/#FAQ1

[2] https://www.rightmove.co.uk/property-to-rent/find/JLL/Lochrin-Quay.html?locationIdentifier=BRANCH%5E192098&propertyStatus=all&includeLetAgreed=true&_includeLetAgreed=on

In the Pipeline

Glasgow City Council have approved the largest number of BTR homes compared to other local authorities in Scotland. An additional 2,246 BTR homes have received planning approval in Glasgow, while a further 1,124 and 400 units are in the planning process and pre-planning stage, respectively. These developments include Holland Park where Moda/Apache plan to develop over 400 BTR homes; Candleriggs where Inhabit intend to build more than 300 homes; and the Merchant City where Get Living have plans to construct 600 homes.1

In Dundee, Our Enterprise plans to deliver 117 flats (39 studios, 37 1-beds and 41 2-beds) as part of the Dundee Waterfront redevelopment. Until recently, Whiteburn Projects Ltd. also planned to convert the former Dundee College building into BTR apartments, but this is no longer going ahead.

In Edinburgh, there are 1,230 BTR homes in planning/pre-planning. A further 477 homes have received planning approval.

Scottish Government Support and Funding for BTR Housing

The Scottish Government has supported the delivery of BTR homes in Scotland in the following ways:

Planning Delivery Advice (PDA)

The Scottish Government has issued Planning Delivery Advice (PDA) which builds on Scottish Planning Policy and outlines a definition of BTR, listing its characteristics and the opportunities and challenges facing this subsector.1

The PDA also provides advice to local authorities on how to facilitate BTR developments in their areas. Local Authorities are encouraged to take a flexible approach and to consider the opportunities to provide affordable housing under the management of a single landlord.

Rental Income Guarantee Scheme (RIGS)

RIGS is a pilot scheme run by the Scottish Futures Trust (on behalf of the Scottish Government) which seeks to provide investors with greater confidence during the early stages of a development, when letting risk is likely to be highest. Should a participating investor not achieve their anticipated level of rental income, post-habitation, a Scottish Government guarantee would compensate them for part of this loss. However, to date there have been no applications to this scheme.2

Tax advantages

The Scottish Government has made available multiple-dwellings relief where six or more residential properties are purchased in a single transaction. While this is comparable to the multiple-dwellings relief available under the Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDTL) in the rest of the UK, such transactions in Scotland are also exempt from the 3% Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (LBTT) Additional Dwellings Supplement.

Loan funding

In April 2019, the Scottish Government also announced a £30m investment in BTR. This investment, which will be delivered through Sigma Capital Group plc., is in the form of loan funding which comes from the Building Scotland Fund and will allow for the construction of an additional 1,800 family BTR homes in Scotland.

Mid-Market Rented Housing (MMR)

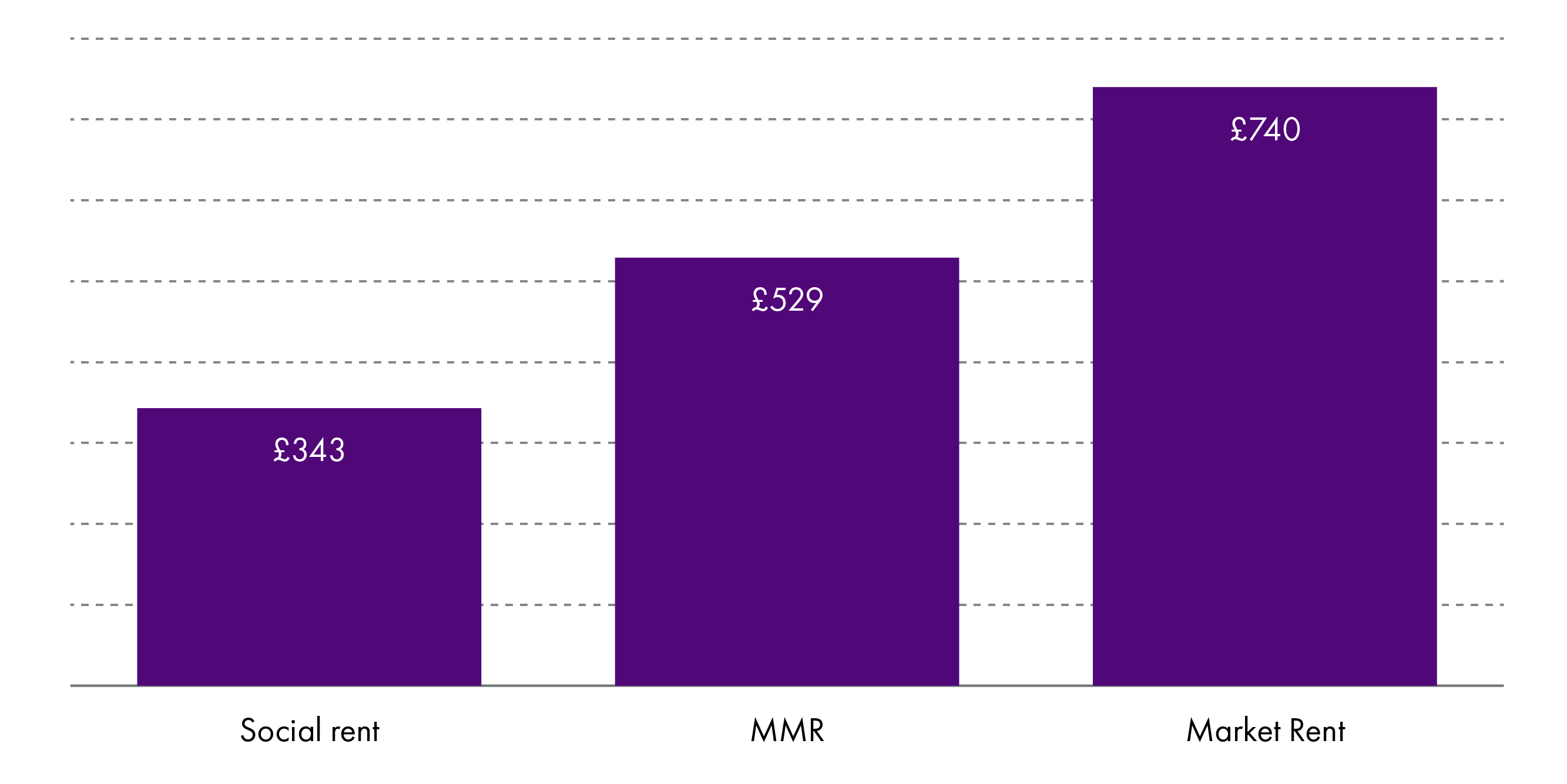

Mid-market rent (MMR) housing is aimed at assisting people on low and modest incomes to access affordable rented accommodation. Rents are lower than private rents but higher than rents in social housing (provided by councils and Registered Social Landlords (RSLs).

Tenants living in MMR property have a private rented sector tenancy i.e. a short assured tenancy, or, for units let after 1 December 2017, a private residential tenancy.

In Scotland, the main providers of MMR housing are RSLs or their subsidiaries. Most of these RSLs will have received Scottish Government subsidy to provide MMR housing, although some RSLs have developed MMR housing without Scottish Government subsidy.

Since 2012, a significant tranche of MMR housing has been delivered through the National Housing Trust initiative. Under this initiative, developers are appointed to build houses on land that they already own. Upon their completion, the developer, Scottish Futures Trust and the relevant local authority jointly purchase the homes through a special purpose vehicle. This takes the form of a Limited Liability Partnership. There was no requirement for Scottish Government subsidy, however repayment of the local authority borrowing was guaranteed by Scottish Ministers.

This section looks at:

How do RSLs let MMR Housing?

Unlike social housing for rent, there is no legislative framework governing the allocation of MMR housing.

Each RSL will set their own eligibility criteria for MMR housing which is mainly based on income levels and an affordability assessment. Income levels and affordability assessments vary between local authorities. Scottish Government guidance states:

Mid-market rent is aimed at assisting people on low and modest incomes to access affordable rented accommodation. It is important however that prospective tenants are not discriminated against as a result of the source of that income, for example, through a work or state pension or social security contributions. Income criteria will be based upon figures in the local authority's Local Housing Strategy, Affordable Housing Policy, or as otherwise agreed between individual local authorities and the relevant grant provider. Projects aimed at higher income groups are ineligible for funding.

Scottish Government. (2019). Affordable Housing Supply Programme: Process and procedures MHDGN 2019/01. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/correspondence/2019/02/affordable-housing-supply-programme-process-and-procedures-mhdgn-201901/documents/guidance-and-procedures-mhdgn-2019-01-affordable-housing-supply-programme/guidance-and-procedures-mhdgn-2019-01-affordable-housing-supply-programme/govscot%3Adocument/Guidance%2Band%2BProcedures%2B-%2BMHDGN%2B2019%2B01%2BAffordable%2BHousing%2BSupply%2BProgra....pdf [accessed 13 May 2019]

Research, commissioned by the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH) Scotland and the Wheatley Group in 2017, found that:

Supply of MMR has been driven by eligibility rules - usually working households, and minimum and maximum household income thresholds which vary by local authority and supplier, but are typically between £15,000 and £36,000. In practice, the product has been focused towards single people and couples with no children, with household incomes of between £20,000 and £30,000.

Evans, A., Littlewood, M., R, S., & D, O. (2017). Housing Need and aspiration: the role of mid market rent.. Retrieved from http://www.cih.org/resources/PDF/Scotland%20Policy%20Pdfs/Mid%20market%20rent/Housing%20need%20and%20aspiration-%20the%20role%20of%20MMR%2010%2003%202017%20FINAL.pdf [accessed 13 May 2019]

Current MMR housing advertised for let by RSLs appears to have a maximum household income criteria of around £45k per annum. A couple of examples are provided below.

Link Housing says that to qualify for MMR, an applicant's (gross) annual income should not exceed £27,953 per household for single applications or £45,836 for joint applications.3 For properties in Edinburgh, household income should not exceed £39,067 per annum. An affordability assessment is carried out comparing the monthly rent for the property to your monthly income. The monthly rent must not exceed 45% of the households' (net) monthly income.

Sanctuary Scotland has the following eligibility criteria for MMR housing in Glasgow and North Lanarkshire council areas: 4

Applicants must be employed or have a formal offer of employment in the area where the mid-market rent scheme is located. This is defined as 'commutable from home to work'.

Applicants must have a gross annual income within the minimum and maximum threshold: £17,000 - £40,000.

Applicants must be aged 16 years and above.

Tenants taking up an offer of MMR housing are normally expected to pay a deposit of one month's rent.

Scottish Government Support for MMR Housing

The Scottish Government supports the development of 'affordable' housing through its Affordable Housing Supply Programme (AHSP).

Affordable housing units completed with funding from the AHSP count towards the Scottish Government's target to deliver 50,000 affordable homes over five years from April 2016 to 31 March 2021. While the target includes a commitment to deliver 35,000 social rented homes, there is no specific target for MMR housing.

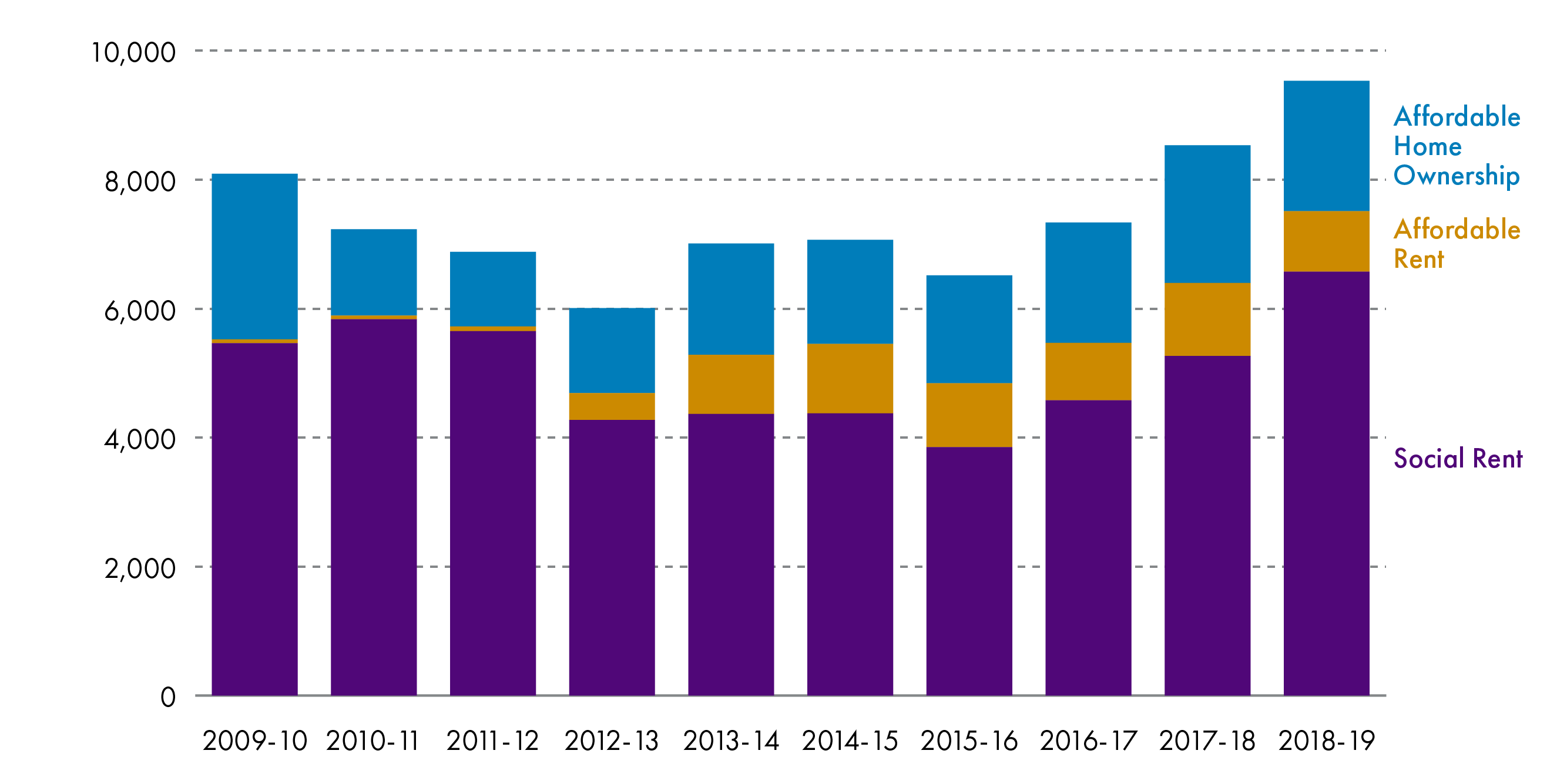

As Figure 4 below shows, MMR housing has accounted for a growing proportion of the Affordable Housing Supply Programme since around 2012/13. The Scottish Government show that 'Affordable rent' completions (most of which is MMR) accounted for 13% of the total completions in 2018/2019.1

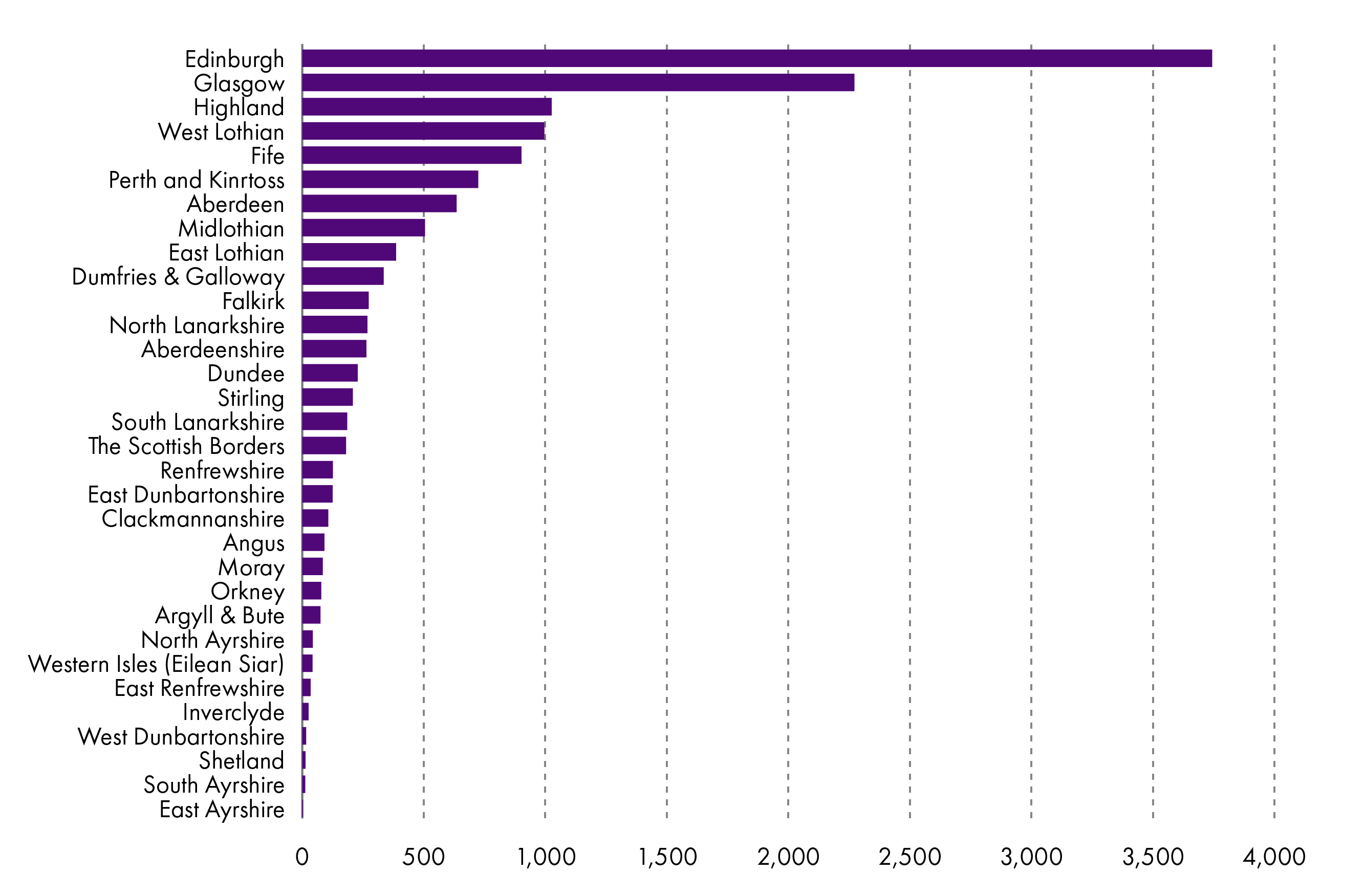

Figure 5 below shows that MMR housing has been developed particularly in the City of Edinburgh Council area where there is a highly pressured housing market. Glasgow, Highland and Fife are other areas where significant numbers of mid-market rented units have been developed.

In some areas of Scotland, there has been little, or no, MMR housing developed. One of the main reasons for this is that, in certain locations, there is relatively little difference between private market rents and MMR rents. Therefore, some RSLs may not be able to make the development of housing in these areas financially viable because the rents they would have to charge would make them unaffordable for their tenants. An example of this would be Dundee, where the LHA and Broad Rental Market Areas, set by the DWP, are set using rental data for the whole of Dundee and Angus. This assumes that development costs and affordability are the same across the whole area, which is unlikely to be the case.6

Scottish Government Funding for MMR

A range of funding mechanisms for MMR housing have been developed by the Scottish Government including grants, loans and guarantees.

Grant funding for RSLs and their subsidiaries

The Scottish Government provides grant subsidy to RSLs and their subsidiaries to develop MMR housing. Local authorities, in conjunction with their partners, decide whether to include plans for MMR housing in their Strategic Housing Investment Plans (SHIPs).1

The Scottish Government subsidy benchmark for MMR housing is £44k or £46k for homes that meet a 'greener' building standard. The remaining development costs are largely funded through private finance borrowed by RSLs (borrowing is repaid with tenants' rents). The subsidy benchmark level is lower than for the development of social housing, which is around £70k to £84k.2

Since 2011/12 just under 50 RSLs and their subsidiaries have received grant funding to develop MMR housing.

Loan funding

The Scottish Government has provided a 25 year loan of £55m to the Local Affordable Rented Housing Trust to provide 1,000 MMR houses across Scotland.3 LAR is a Scottish charity set up in 2015. It has also secured £65 million of private finance.

In June 2018, the Scottish Government also announced loan funding of £47.5m to Places for People to deliver 1,000 affordable MMR homes.3 This was in response to the MMR invitation to provide mid-market rented homes at scale and provide better value for money than conventional grant subsidies.

Guaranteed funding through the National Housing Trust

As mentioned above, Nation Housing Trust homes are jointly funded by participating local authorities and their chosen development partners, with the Scottish Government underwriting any shortfall in the repayment of local authority loans through the provision of a guarantee. As a condition of the guarantee, properties were to be available to rent for a period of between five and 10 years, after which time they could be sold to tenants, failing which they could be sold on the open market.

The NHT (National Housing Trust) programme, having generated 28 joint ventures delivering over 1,600 high quality homes to date, has now completed. There is no further round of procurement being considered as the focus of this initiative was to stimulate housing development post-recession and to develop the MMR tenure. This was much in its infancy, without established market demand, when the scheme was conceived.5

The NHT programme has been succeeded by the Housing Delivery Partnerships (HDP) model developed by Scottish Futures Trust and supported by the Scottish Government. Housing Delivery Partnerships draw on many of the funding, governance and delivery arrangements developed through the NHT programme but, significantly, the housing output will be available for MMR in perpetuity and the delivery partnership is made up of public sector partners only.

As MMR has become proven as a viable tenure there is no requirement for a guarantee from Scottish Ministers. Depending on the prevailing economic circumstances, other forms of finance may be required alongside local authority on-lending to make the HDP viable. These can include equity finance (the sale of shares), or the use of AHSP monies to subsidise acquisition. The first HDP (Edinburgh Living, a partnership between The City of Edinburgh Council and Scottish Futures Trust) made use of AHSP monies of around £22k per unit to improve the viability of acquiring 750 properties in the Edinburgh market.

MMR Rent Levels

The Scottish Government guidance for AHSP sets out that rents for Scottish Government subsidised MMR units should start at no more than the relevant Local Housing Allowance (LHA) rate for the property size in question, although there is some flexibility in exceptional circumstances.1

LHA rates are used to determine the maximum amount of housing benefit payable to tenants living in private rented housing. They are set by Rent Officers (working for the Scottish Government) for each size of property (up to a 4 bed) within one of 18 Broad Market Rental Areas in Scotland.

LHA rates had been set at the 30th percentile (i.e. the lowest third) of local market rents. However, a series of UK Government welfare reforms, including a four year freeze on LHA rates from 2016, has broken the direct link between local market rents and LHA rates. In many areas, LHA rates now cover less than the lowest third of the market.2 For this reason, the Scottish Government is beginning to advocate the use of the 30th percentile of the Broad Rental Market Area rent for starting MMR rents, and has permitted this definition to be used by LAR Housing Trust and the Places for People MMR fund.

Figure 6 below gives an example of how one bedroom rents in the Glasgow area might compare.

Note: social rent based on Glasgow Housing Association average for 2017/18; MMR as advertised on Link Group website (as at 30 May 2019); private rent is average for Greater Glasgow (year to end September 2018).

Scottish Government guidance advises that rents for MMR housing can increase annually provided they do not at any time exceed:1

• the mid-point of market rent levels for the property sizes in question in the relevant Broad Rental Market Area (as assessed by the Scottish Government); or,

• where agreed in writing with the Scottish Government and the local authority or – in the case of Glasgow and Edinburgh – the relevant City Council, the mid-point of market rent levels in a particular local market area. This demonstrated and accepted as being materially different from the relevant Broad Rental Market Area.

Affordable Home Ownership

Government support to help people buy a home has been a long-standing feature of housing policy in Scotland.

There are several options for affordable home ownerships including:

Shared Equity

The main way that the Scottish Government currently supports people to buy a home is through shared equity schemes. Under these schemes, the government provides purchasers with an equity stake, which reduces the deposit they need to find. Purchasers pay the government back its equity contribution at some point in the future.

The Scottish Government supports two main schemes.1

• Low Cost Initiative for First Time Buyers (LIFT) of which the main scheme is the Open Market Shared Equity Scheme. This provides a shared equity contribution to help buyers purchase a house, up to certain price thresholds, on the open market.

• The Help to Buy (Scotland) Affordable New Build Scheme and Small Developers Scheme provides a shared equity contribution for households to purchase a new build property from a participating developer. The maximum value of property that can be purchased is £200k. Since Help to Buy was introduced in September 2013, around 12,800 Help to Buy sales have taken place with equity loan funding from the government worth around £436m.

It is not clear how these initiatives might continue post-2021 or how builders might react to any potential winding down of the Help to Buy scheme. Some builders were already providing shared equity before Help to Buy was introduced. However:

...changes to European Mortgage Directives on second charge lending make this extremely difficult going forward. So, without buyers benefiting from shared equity will builders have the confidence to build starter homes or open up marginal sites? The absence of Help to Buy could create a very crowded market for the less risky supply of large family homes in strong market areas, restricting choice to the squeezed middle.

Campbel, K. (2019). Options for Affordable HOme Ownership. Retrieved from https://housingevidence.ac.uk/options-for-affordable-home-ownership/ [accessed 09 July 2019]

Shared Ownership

Shared ownership schemes are where someone owns part of a home and pays rent to a RSL that owns the other part of the home. While such schemes have been available in Scotland in the past, the Scottish Government does not promote shared ownership, since an evaluation of LIFT schemes in 2011 indicated that other tenures were better value for owners.1

Shared ownership is becoming increasingly popular in England, particularly in pressurised housing markets, with institutions keen to invest in the unsold shares. A common lease developed in England has buy-in from housing providers and mortgage lenders alike, making it an attractive proposition for the sector. If we can learn from schemes of the past and modernise shared ownership in Scotland, there is an opportunity to provide a new choice for home buyers.

Campbel, K. (2019). Options for Affordable HOme Ownership. Retrieved from https://housingevidence.ac.uk/options-for-affordable-home-ownership/ [accessed 09 July 2019]

Home Ownership Made Easy (HOME)

HOME has been developed by the Scottish Futures Trust (SFT) to enable housing providers to utilise long-term finance to deliver homes for owner occupation. It is a way to deliver affordable housing for local authorities, housing associations and developers that does not require any subsidy. North Ayrshire Council is piloting the HOME initiative with 33 homes on a former primary school site in Largs.1

The initiative has been targeted at first-time buyers with £5k savings, and older people with £40k equity to invest. Having secured their home with their £5,000 or £40,000 stake, homeowners will then pay a monthly payment (an occupancy fee) to North Ayrshire Council that covers the provision of a management and maintenance package. This contrasts to the traditional shared ownership model as it spreads the burden of maintaining the property.

Self/Custom Build and Co-operatives

Self-build by individuals or groups could play an increasingly significant role as an alternative tenure in Scotland. Over the years the Scottish Government has been involved in promoting schemes with revolving loan facilities, funding the development of individual homes to the point where a mortgage becomes affordable. Currently the Self Build Loan Fund offers loans of up to £175,000 to help with construction fees for self-build projects. This type of development finance could prove an effective use of public funds with loans repayable once the homes are complete and mortgage finance has been secured.i

Deposit help for First Time Buyers

The Scottish Government recently announced a new form of deposit support for first time buyers that will be available to support the purchase of new or previously owned homes.1 £150m is to be made available to support the scheme. Whilst details are yet to emerge, the initiative will involve the Scottish Government offering loans of up to £25,000 to top up a first-time buyer’s deposit.

Benefits of Alternative Tenures

Based on the roundtable discussion, and other evidence, the following perceived benefits of alternative tenures were identified (although this is by no means an exhaustive list).

BTR and MMR can offer tenants a good standard of accommodation and professional management services.

The positive impact of Alternative Housing Tenures within the wider community.

Alternative Tenures can provide Flexibility for RSL's to manage their stock.

Alternative Tenures can meet demand and have potential to meet a wider range of housing needs.

BTR and MMR housing can offer tenants a good standard of accommodation and professional management services.

Comparing RSL and MMR housing with housing provided by traditional private rented sector landlords, Richard Jennings said:

As an institutional landlord we – Castle Rock Edinvar – are committed to long term investment in our assets; we have an in-house maintenance service that can respond quickly to emergencies; we are focused on tenant safety and our compliance requirements; rental increases are at – or – below inflation; and we offer long term security of tenure.

Jennings, R. (2019). Flexibility and Adaptability, Mid Market Rent and the Supply of Affordable Accommodation. Retrieved from Flexibility and Adaptability, Mid-Market Rent and the Supply of Affordable Housing [accessed 09 July 2019]

Research that involved interviews with tenants living in MMR housing reported that tenants considered MMR housing to be good value for money.

MMR tenants stated that they had made a trade-off between quality and affordability when choosing MMR. They emphasised the value for money arguments, revealing that MMR is not necessarily the cheapest, or most affordable renting option. But they consider it as good value for money when taking into consideration the new build quality and the management services compared to most private renting options. One tenant encapsulated the views of many MMR tenants summarising it as the ‘best of all worlds’ – combining the best of private renting and social renting.

Evans, A., Littlewood, M., R, S., & D, O. (2017). Housing Need and aspiration: the role of mid market rent.. Retrieved from http://www.cih.org/resources/PDF/Scotland%20Policy%20Pdfs/Mid%20market%20rent/Housing%20need%20and%20aspiration-%20the%20role%20of%20MMR%2010%2003%202017%20FINAL.pdf [accessed 13 May 2019]

Wider Community Impacts

At the round table discussion, participants talked of the wider community impacts that alternative tenures might have. For example, a participant suggested that professionally managed BTR/ MMR housing can support inward economic investment by providing suitable housing options for employees. Participants also spoke of the benefits that MMR housing contributes to place-making, the planning, design and management of public spaces involving multiple agencies and local communities.

Rettie and Co.1 noted that the fast delivery and occupation of BTR housing can assist with regeneration and large scale developments by creating a sustainable community quickly.

Alternative Tenures can provide flexibility for RSL's to manage their stock

Castle Rock Edinvar has used MMR to create mixed tenure developments in areas of predominantly social rented stock. They have switched properties from social rent to MMR and vice versa to help meet local needs and to generate additional income to fund the development of new homes.

Shared Ownership could be used in a similar way to add to the tenure mix and offer more options to households.

These homes could also be used flexibly to meet changing needs with the housing providers buying back the purchased share and converting the tenure to rent

Alternative Tenures can meet demand and have potential to meet a wider range of housing needs

There is evidence that newly developed MMR housing has been popular, with some new developments being oversubscribed. For example, a MMR development in Harbour Point, Edinburgh, received over 3,400 tenant applications for the 96 available units. Most of this demand came from single applicants or couples under 35 years-old without children who were currently renting privately.1

As explained earlier, MMR tends to be offered to tenants on a first come, first served basis. There may be more potential to target the housing at specific groups in housing need. For example, at the roundtable a council representative said their council was considering ways of using grant funded MMR housing to more closely meet the needs of homeless households (although it was noted that the requirement for tenants to provide a rent deposit could be a problem).

Future of Alternative Tenures

Participants at the round table appeared positive about the role of alternative tenures to create an effective housing system that provides a wide choice of housing options. There was a discussion about what might inform the development of such tenures. These include:

The use of LHA rates in setting MMR rents needs to be revised

At the round table, some participants described LHA rates as being too 'blunt' a tool for rent setting, suggesting that this needed to be revised. In addition to the freeze on LHA rates, a key issue is that LHA rates cover relatively wide geographical areas which can mask wide variations in local rents, for example between a popular city centre location and less popular suburban areas.

An example of this is Dundee, where the LHA and BRMA are set using rental data for the whole of Dundee and Angus, which assumes that development costs and affordability are the same on Dundee Waterfront as they are in Arbroath. Clydebank sits proudly in West Dunbartonshire, where the LHA for a 2 bed is £103 a week, against £116 for Greater Glasgow; yet the costs of construction are the same, and a significant number of people living in the PRS in Clydebank will be working in the Greater Glasgow area yet cannot access this affordable tenure. Whilst £103 a week may not sound like a barrier to making development happen, when rolled up over the lifetime of the funding model it makes a significant difference in terms of what you can afford to build.

Jennings, R. (2019). Flexibility and Adaptability, Mid Market Rent and the Supply of Affordable Accommodation. Retrieved from Flexibility and Adaptability, Mid-Market Rent and the Supply of Affordable Housing [accessed 09 July 2019]

How rents for MMR housing are set raises questions around how, and at what scale, affordability should be defined.2 As the CIH/Wheatley Group research argued:

The use of LHA as a pricing mechanism is too crude a tool and does not recognise the nuances of smaller local markets. But there are tensions between development viability and the potential for pushing up rent levels at the cost of affordability. While tenants will make their own value for money judgements over price versus quality, government and developers should not lose sight of the affordability imperative where public subsidy is used

Evans, A., Littlewood, M., R, S., & D, O. (2017). Housing Need and aspiration: the role of mid market rent.. Retrieved from http://www.cih.org/resources/PDF/Scotland%20Policy%20Pdfs/Mid%20market%20rent/Housing%20need%20and%20aspiration-%20the%20role%20of%20MMR%2010%2003%202017%20FINAL.pdf [accessed 13 May 2019]

Longer term subsidy considerations

The longer-term implications of government investment in housing needs to be considered:

There were interesting reflections on how value for public money is best achieved and evaluated in the housing sector, through the life of the house and its occupants. Owner-occupation promises reduced costs in old age and, typically, very few housing-cost calls on the public purse. Options which allow households to acquire some equity, through shared ownership or equity sharing for example, also provide an asset that may be used to offset some costs in old age.1

M, M. (2019). Approaches to delivering alternative tenures. Retrieved from https://housingevidence.ac.uk/approaches-to-delivering-alternative-tenures/ [accessed 09 July 2019]

Providing housing above social rent levels potentially creates a need for long-term higher subsidy contributions. At the moment, decisions around funding packages, including from Government resources, are made in the moment, with an eye to how a development or acquisition can be made to work immediately, while these longer-term questions can get lost.

Variety of funding streams

As this briefing has outlined, a wide range of mechanisms are available to fund alternative tenures. Discussion at the round table suggested that this can be a strength as it enables housing provision to be tailored to suit local circumstances.

The prospect of expanding institutional investment into housing provision in Scotland is a further attraction of the alternative tenures. Institutions are attracted to investment in homes for rent but also in funding the rented share in Shared Ownership as demonstrated by the recent activity in England.

The HOME model outlined above for older people is interesting in that it uses a household’s own capital, either through sale of a current home that no longer meets the owner's needs, or from savings, alongside low-cost borrowing to allow housing providers to fund the delivery of new homes for accessible ownership, filling a gap in current provision for older people.

Participants also noted that there are advantages in having some stability in the funding models rather than a constant stream of new initiatives that may have different conditions attached. Long-term, stable solutions were seen as preferable, as opposed to short term fixes.1.

Evidencing the impact of existing schemes

It is vital that the impact of current schemes is properly assessed and evaluated so that future development is informed by evidence. The Scottish Government has recently commissioned an evaluation of its shared equity schemes. Additionally, statistical evidence is gathered on a quarterly basis by the Scottish Government to monitor the progress of the Affordable Housing Supply Programme.

As evidenced in their 2019 report,1 Rettie and Co. are monitoring the development of the Build to Rent programme, affiliating it with supply and demand in the areas in which it is taking place. However, there is little current evidence of the social impact of this scheme on local communities.