Scottish Government infrastructure investment

Since 2007, Scottish Government-led infrastructure projects worth £11.1 billion have been completed. A further £3.7 billion of capital projects are currently under construction. This briefing looks at the profile of investment to date and what is currently in the pipeline. It also looks at how infrastructure is funded and how decisions are made relating to infrastructure plans.

Executive Summary

Since 2007, £11.1 billion worth of Scottish Government-led infrastructure projects have been completed. These are mostly projects in transport, health and education. A further £3.7 billion of capital projects are currently under construction.

In addition to the infrastructure investment that is led by the Scottish Government, there is also:

local authority-led investment, in areas such as housing

private sector-led investment, in areas such as digital infrastructure

investment by Scottish Water, the cost of which is met by user charges

This briefing focuses on the Scottish Government-led infrastructure investment.

The Scottish Government sets out its priorities for infrastructure and plans for specific infrastructure projects in its Infrastructure Investment Plans (IIPs). The first IIP was published in 2008 and updates have been published in 2011 and 2015. Updates on individual projects are provided in six-monthly project pipeline updates, published as part of the Major Capital Projects progress updates, the latest of which was published in September 2018.

The latest project pipeline includes 69 projects with a combined capital value of £5.0 billion. Around half (34) of the pipeline projects are schools. In value terms, 50% of the total is accounted for by road and rail projects. A total of 10 projects are planned or underway in these sectors, with the Edinburgh Glasgow Rail Improvement Programme (£858 million) and the Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route (£745 million) the largest projects.

The 2018-19 Programme for Government included significant commitments on future infrastructure investment, with the Scottish Government committing to increase annual infrastructure investment so it is £1.5 billion per year higher at the end of the next Parliament [2025-26] than in 2019-20. This is referred to as the "National Infrastructure Mission". A new Infrastructure Commission is being set up to support delivery of the National Infrastructure Mission and development of the next Infrastructure Investment Plan.

The primary sources of funding for public sector infrastructure investment in Scotland are:

capital budget

borrowing powers

financial transactions

revenue-financed investment

innovative financing schemes.

The Scottish Government has used revenue-financed investment to boost the overall level of infrastructure investment in Scotland, including through use of its 'non-profit distributing' (NPD) model of investment (an adapted version of the UK Government's private finance initiative - PFI). Revenue financing allows governments to increase investment without any upfront impact on their budget.

However, changes to European accounting rules have affected the viability of the NPD model and reliance on revenue financing looks set to reduce. The Scottish Government's project pipeline shows that 43% of the value of the pipeline is being revenue financed. However, when excluding projects that have already entered the construction phase, only 24% of the pipeline value is planned to be revenue financed. No new projects in the project pipeline are to be financed by NPD and rail infrastructure investment is no longer using revenue financing.

No details have yet been given on how the Scottish Government's plans to increase infrastructure investment will be financed. Greater use is likely to be made of borrowing powers and modified revenue finance schemes may also be explored. The Scottish Government is committed to spending no more than 5% of its resource budget (excluding social security) on repayments arising from revenue financing and borrowing. There is currently scope to accommodate further borrowing and revenue finance project repayments without breaching this commitment.

The Scottish Government's various priorities – economic, social, environmental – must all be balanced when deciding on how best to spend limited capital budgets. There is also a balance to be struck between investment in large-scale national infrastructure projects and smaller scale local interventions that can be important in tackling inequalities. In addition, the need to spend money on maintaining existing assets needs to be considered alongside the demands for new assets within the context of constrained budgets.

Decision-making on infrastructure investment is led by the Scottish Government's Infrastructure Investment Board and will be informed by the newly created Infrastructure Commission. The Scottish Futures Trust (SFT) has a role in promoting value for money in infrastructure investment. Scrutiny of investment plans and completed investment projects is undertaken by the Scottish Government as well as independently by the Scottish Parliament (including the Public Audit and Post-legislative Scrutiny Committee) and Audit Scotland.

| Cover image: Queensferry Crossing, Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) |

Introduction

Infrastructure can be defined as the basic physical and organisational structures and facilities (for example buildings, roads or power supplies) needed for the operation of a society or enterprise. 1 A broader definition, often used by governments, also tends to encompass social infrastructure such as schools, hospitals and housing.

The Scottish Government's Infrastructure Investment Board adopts the following definition:

Infrastructure includes economic and social aspects, defined as: The physical and technical facilities, and fundamental systems necessary for the economy to function and to enable, sustain or enhance societal living conditions. These include the networks, connections and storage relating to enabling infrastructure of transport, energy, water, telecoms, digital and internet, to permit the ready movement of people, goods and services. They include the built environment of housing; public infrastructure such as education, health, justice and cultural facilities; safety enhancement such as waste management or flood prevention; and public services such as emergency services and resilience.

Scottish Government. (2018, May 18). Infrastructure Investment Board: terms of reference. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/infrastructure-investment-board-terms-of-reference/ [accessed 14 January 2019]

There is a considerable volume of economic research to support the view that investment in the right infrastructure can help grow the economy. The London School of Economics' first Growth Commission report commented that:

Investments in infrastructure, such as transport, energy, telecoms and housing, are essential inputs into economic growth. They are complementary to many other forms of investment. They also tend to be large-scale and long-term, requiring high levels of coordination to maximise the wider benefits that they offer. This makes it inevitable that governments will play a vital role in planning, delivering and (to some extent) financing such projects.

LSE Growth Commission. (2013). Investing for Prosperity: Skills, Infrastructure and Innovation. Retrieved from http://www.lse.ac.uk/researchAndExpertise/units/growthCommission/documents/pdf/LSEGC-Report.pdf [accessed 3 December 2018]

The Scottish Government plays a varied role in infrastructure. These roles include:

identifying infrastructure needs

planning a pipeline of large-scale construction projects and smaller projects

maintaining existing assets

creating and maintaining a regulatory environment

funding and procuring infrastructure projects.

This briefing focuses on public investment in infrastructure. Its sections describe:

Past choices: what has been invested?

Since 2007, £11.1 billion worth of Scottish Government-led infrastructure projects have been completed. This figure, and the analysis which follows, relate only to those projects where the Scottish Government has a lead role in procurement or funding, so will not capture all public infrastructure investment. For example, the data presented below does not include local authority-led projects or other significant investment areas where the Scottish Government is not the lead partner (such as housing, energy efficiency, expansion of early learning & childcare and City Region Deals). The figures also exclude maintenance expenditure and small projects below the £20m threshold for the project pipeline.

There is also additional private sector led investment (such as in digital infrastructure) and investment by Scottish Water, the cost of which is met by user charges.

Investment by sector

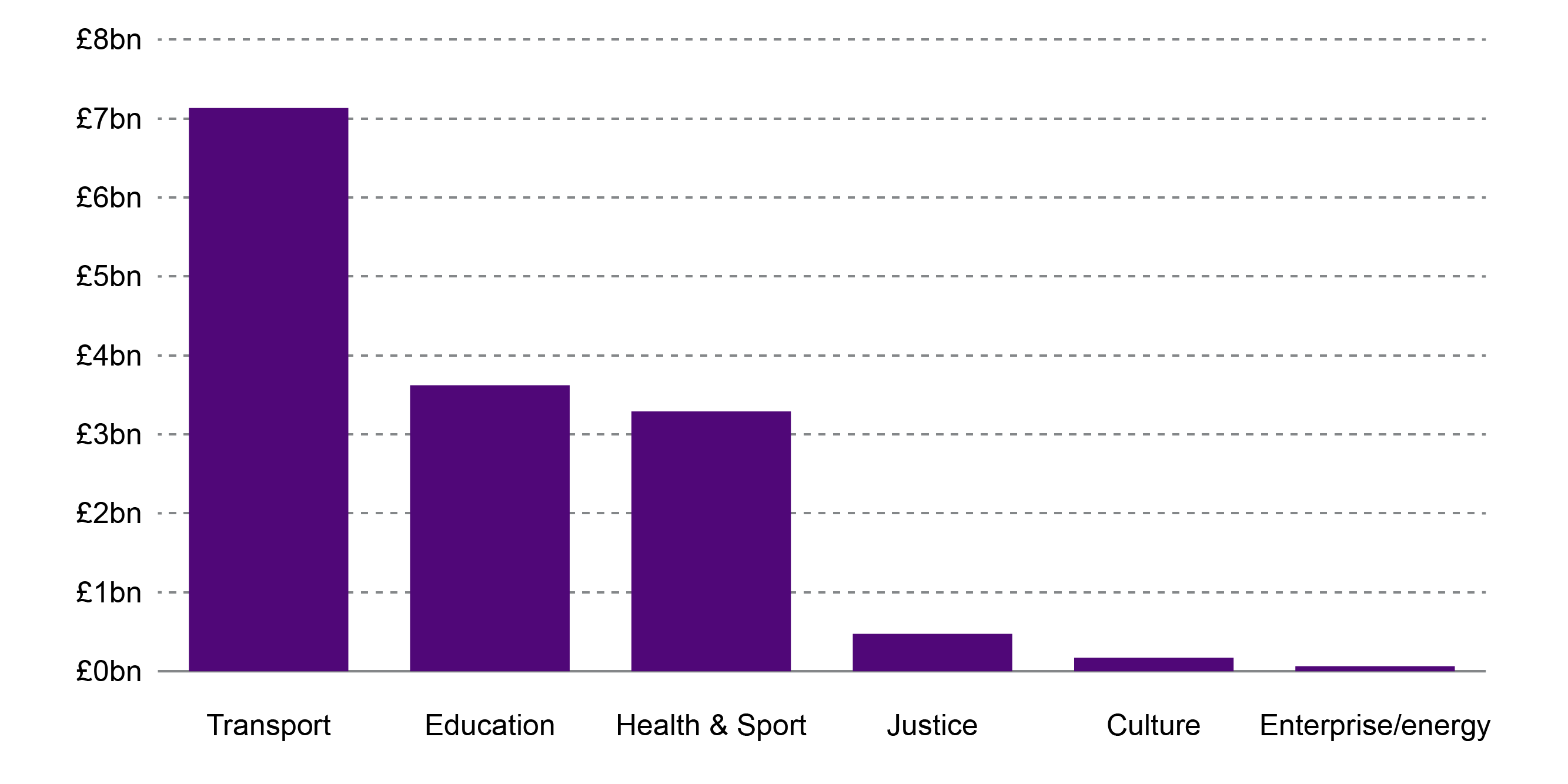

The £11.1 billion of investment since 2007 is predominantly accounted for by projects in transport, health and education. This includes school investment programmes led by the Scottish Government, but not local authority led schools investment. A further £3.7 billion of capital projects are currently under construction.

Further discussion of investment in four key areas (transport, health, schools and housing) can be found in the Annex.

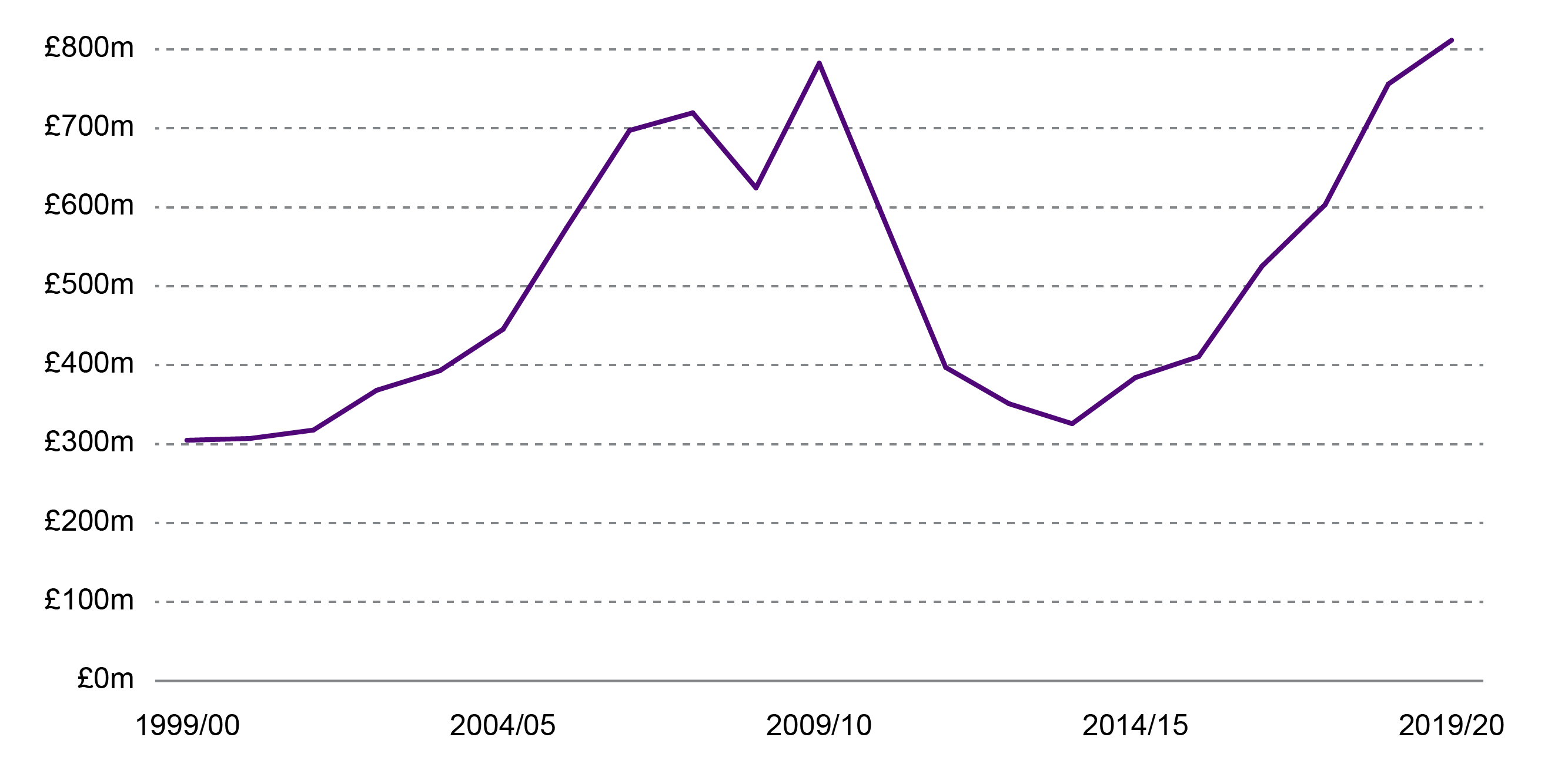

Investment by year

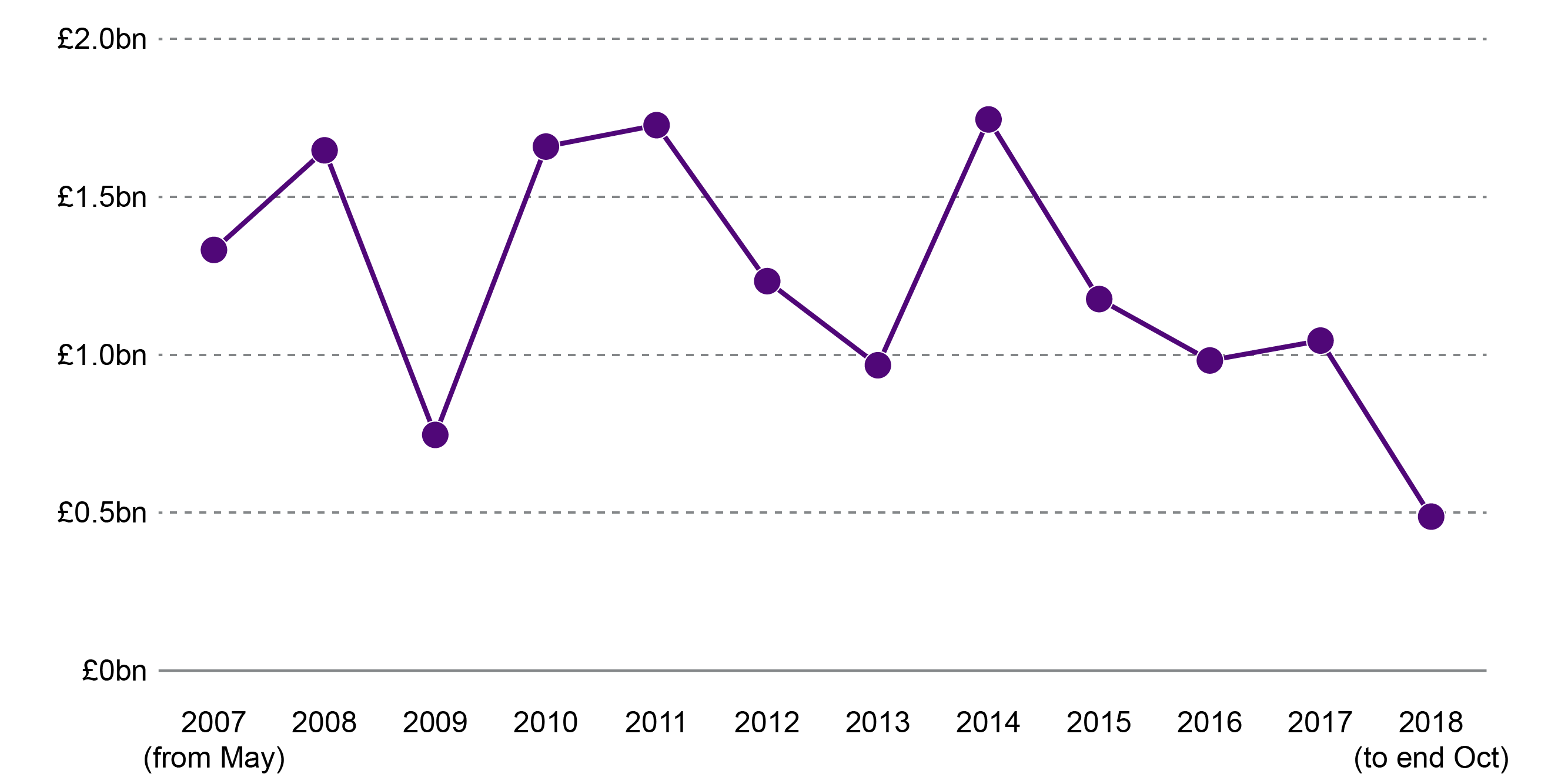

The value of investment fluctuates considerably from year to year (Figure 2), but this partly reflects the way in which the data are reported. The full value of a project is included in the year in which construction commenced, so does not reflect the profiling of spending across the duration of the construction phase. As such, the figures are influenced by the commencement of particularly large projects in the following years:

2008 - M74 completion (£692 million)

2010 - Queen Elizabeth University Hospital and Royal Hospital for Children (£842 million)

2011 - Forth Replacement Crossing (£1.4 billion)

2014 - Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route (£745 million).

Since 2014, there have been no other projects started on this scale. There have been only three capital projects started with a value in excess of £200 million:

Aberdeen to Inverness Rail Improvement Project (£330 million)

NHS Dumfries and Galloway - Acute Services Redevelopment Project (£275 million)

NHS Lothian - Royal Hospital for Sick Children / Department of Clinical Neurosciences (£230 million).

Investment by location

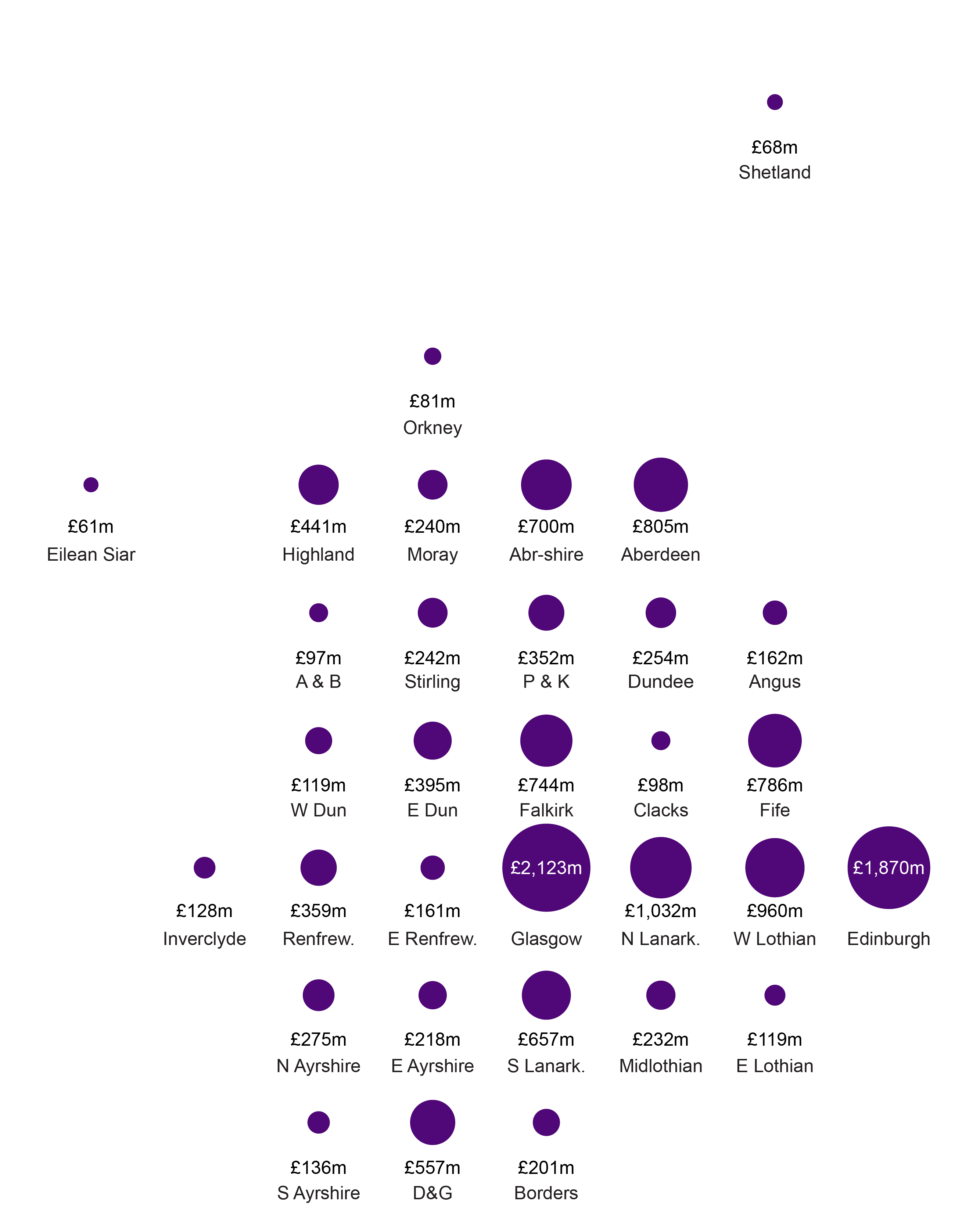

Of the total £14.8 billion investment either completed since 2007 or under construction, more than a quarter (27%) has involved projects in either Edinburgh or Glasgow. North Lanarkshire and West Lothian are the next biggest locations for capital investment, with each getting 7% of the total value of investment, largely as a result of rail and road transport investments. Aberdeen City saw 5% of the total value of investment.

Future choices: identifying infrastructure needs

What are the Scottish Government's investment plans and priorities for the future ? The publications described below provide some information:

Information on the 'pipeline' of planned infrastructure projects is provided by the Infrastructure Investment Plan and its regular updates.

The Programme for Government and national economic strategies and plans highlight the role of infrastructure investment as a key contributor to the wider economy.

The National Planning Framework is a spatial strategy which sets out where infrastructure is needed.

Infrastructure Investment Plan

The Scottish Government sets out plans for specific infrastructure projects in its Infrastructure Investment Plans (IIP). The first IIP was published in 2008 and updates have been published in 2011 and 2015.

The Infrastructure Investment Plan 2015 identified the following principles to guide investment:

Infrastructure Investment Plan 20151

"We will seek to prioritise infrastructure investment based on our guiding principles of:

delivering sustainable economic growth through increasing competitiveness and tackling inequality;

managing the transition to a more resource efficient, lower carbon economy;

supporting delivery of efficient and high quality public services; and

supporting employment and opportunity across Scotland."

Regular information is published to provide up-to-date information on the 'pipeline' of infrastructure projects.

The project pipeline describes projects with detailed plans often at procurement or construction phase. It includes schools, health projects and projects in other portfolios valued over £20 million.2

The major capital projects update provides a narrative on the progress of projects in the project pipeline.3

The programme pipeline describes large programmes of planned investment, often with less precise costings and longer timescales. It includes programmes valued at over £50 million.4

The governance of the infrastructure pipeline is discussed in the governance section.

Project Pipeline - September 2018

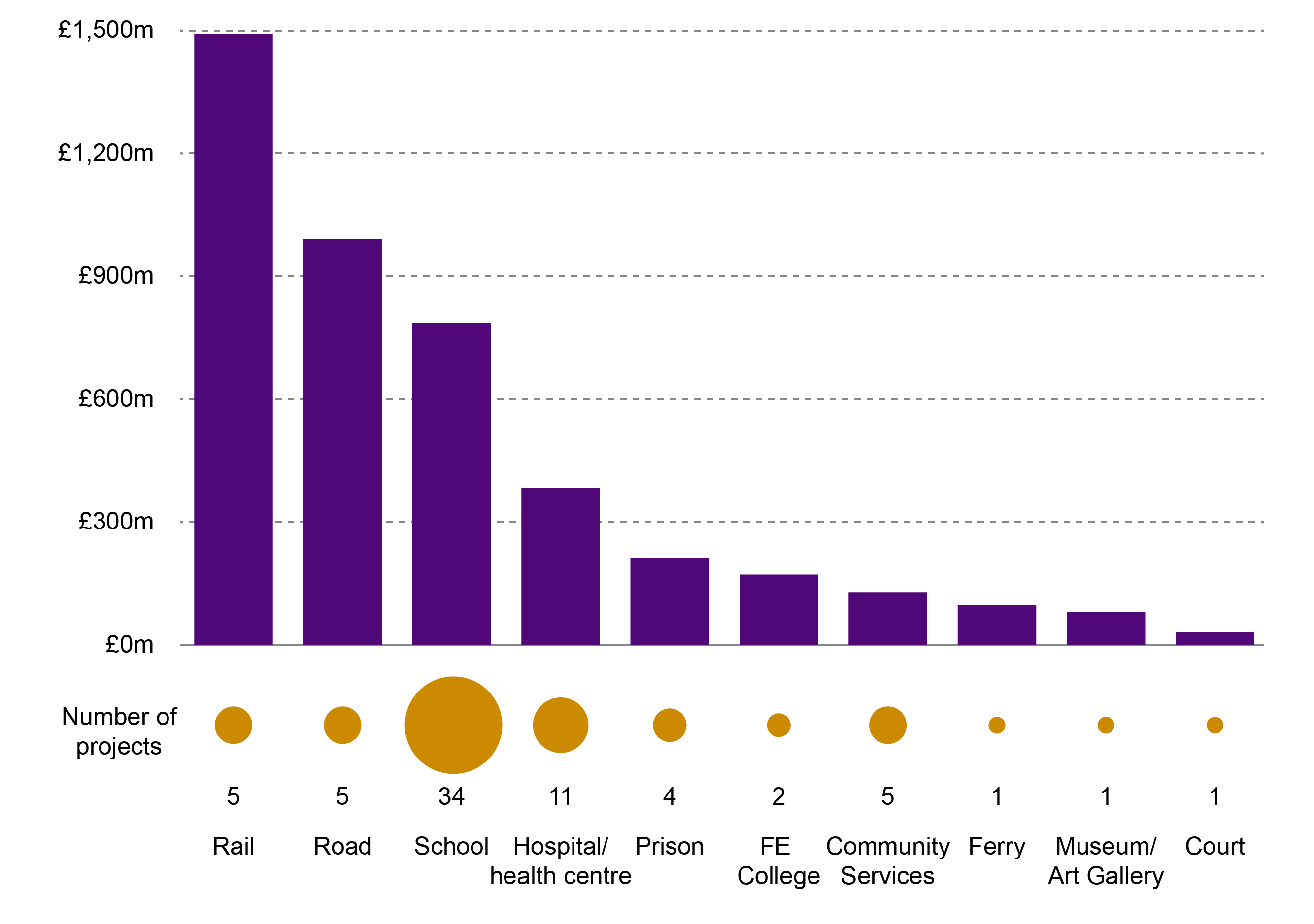

The latest project pipeline includes 69 projects with a combined capital value of £5.0 billion.1

Projects in construction represent 72% of this capital value, while projects in development represent 20%. The project pipeline also includes 14 recently completed projects representing 8% of the pipeline's combined capital value.

Around half (34) of the pipeline projects are schools. However, although they account for more than half of the projects, schools account for less than a fifth of the total capital value of projects. In value terms, 50% of the total is accounted for by road and rail projects. A total of 10 projects are planned or underway in these sectors, with the Edinburgh Glasgow Rail Improvement Programme (£858 million) and the Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route (£745 million) the largest projects.

Economic Strategy

Scotland's Economic Strategy themes its approach on increasing competitiveness and tackling inequality. Infrastructure investment is identified as part of its four priorities.1

Programme for Government

The 2018-19 Programme for Government included significant commitments on future infrastructure investment.1 Announcing the Programme for Government, the First Minister said:

We will make it our mission to steadily increase annual infrastructure investment so it is £1.5 billion per year higher at the end of the next Parliament [2025-26] than in 2019-20. This bold mission will increase Scottish Government capital investment by an additional 1% of current Scottish GDP and to achieve it we will need to continue to innovate in our models for investment and work across the public sector. On current estimates that would mean around £7 billion of extra infrastructure investment by the end of the next Parliament.

Scottish Parliament. (2018, September 4). Official Report. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11639&mode=pdf [accessed 27 November 2018]

According to the Programme for Government document, this increased investment will help support faster broadband, improved transport and more low-carbon energy.1

The 2019-20 Budget defines the baseline at £5,195.8 million and sets out the ambition to increase annual infrastructure investment to £6,750.8 million by 2025-26. The Budget document states that future budgets will provide details of progress against the target.4

The means for funding this increased investment is discussed further in the Infrastructure "Mission" section.

Economic Action Plan 2018-20

The Scottish Government's Economic Action Plan 2018-201 announced plans for a new Infrastructure Commission2 to identify infrastructure needs. This is part of a wider set of actions to increase investment and collaborate with the construction sector, branded a "National Infrastructure Mission".

Infrastructure Commission

"[The] independent Commission will support the Scottish Government’s delivery of its National Infrastructure Mission and development of the next Infrastructure Investment Plan until 2023.

It will advise on the key strategic and early foundation investments to significantly boost economic growth and support delivery of Scotland’s low carbon objectives and achievement of our climate change targets.

Following the completion of a report, the Commission will provide advice to ministers on the delivery of infrastructure in Scotland, including the possible creation of a Scottish National Infrastructure Company.

The Advisory Commission will report on infrastructure ambitions and priorities by the end of 2019, and may make interim recommendations e.g. around guiding principles supporting the evolution of a coherent Infrastructure Investment Plan across sectors."1

The creation of an Infrastructure Commission has been welcomed by, among others, the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE). In its State of the Nation Scotland 2018: Infrastructure Investment report, ICE said:

The new Scottish Infrastructure Commission should have a central role in developing and articulating a long-term vision for Scottish infrastructure considering the whole-life needs of existing infrastructure as well as future capital investment. It should look to make independent, evidence-based recommendations which support the transparency and prioritisation of infrastructure decision making.

Institution of Civil Engineers. (2018, November 8). State of the Nation Scotland 2018: Infrastructure Investment. Retrieved from https://www.ice.org.uk/ICEDevelopmentWebPortal/media/Documents/News/ICE%20News/State-of-the-Nation-Scotland-2018.pdf

ICE recommended that the Commission should be "independent and build cross-party consensus to support a consistent, long-term approach to infrastructure planning and investment".4

A Just Transition Commission has also been announced by the Scottish Government to advise on achieving a carbon-neutral economy. The Just Transition Commission's remit is not yet formalised but the Scottish Government has recognised that the "design and deliver[y of] low carbon infrastructure with the aim of creating decent, high value work" is one of the principles of just transition.6

National Planning Framework

The Scottish Government describes the National Planning Framework as:

the spatial expression of the Government Economic Strategy, and of our plans for infrastructure investment.

Scottish Government. (2014, June 23). National Planning Framework 3. Retrieved from https://beta.gov.scot/publications/national-planning-framework-3/

The NPF is part of the land-use planning system. It is a national strategy designed to cover 20-30 years and must be updated at least once every five years. Strategic and Local Development Plans produced by local authorities must take account of the NPF.2

The NPF also defines a set of National Developments. These are developments that the Scottish Government consider to be key infrastructure needs. The National Development status accords a special status in the planning system designed to facilitate their delivery.

Finance: how is infrastructure funded?

The primary sources of funding for public sector infrastructure investment in Scotland are:

capital budget

borrowing powers

financial transactions

revenue-financed investment

innovative financing schemes.

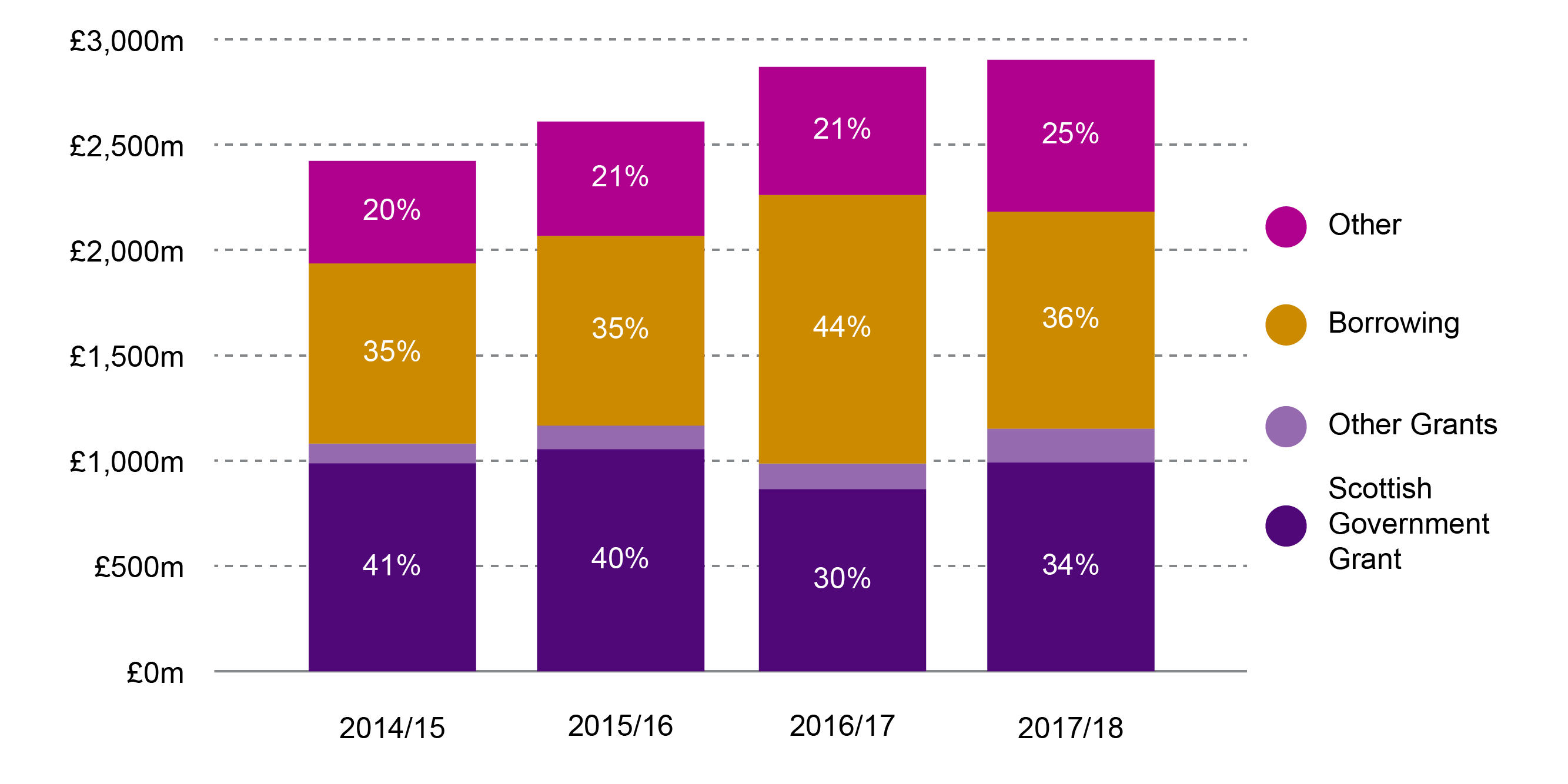

Details on planned investment through each of these routes are set out in the Scottish Government's 2019-20 budget. For 2019-20, the amounts allocated are shown in Table 1.

| Source | Value (£m) |

|---|---|

| UK Treasury - capital budget (includes carry forward from 2018-19) | 4,020 |

| UK Treasury - financial transactions | 636 |

| Scottish Government - capital borrowing | 450 |

| Revenue-financed investment (NPD/hub) | 60 |

| Innovative finance | 30 |

| Total | 5,196 |

Further details on each of these funding sources is provided below.

Capital budget

The capital budget is the "traditional" method of funding infrastructure projects by way of a grant to cover the capital cost of the project.

The Scottish Government receives a capital budget allocation as part of its block grant from the UK Government. In addition, the Scottish Government can borrow up to £450m a year for capital investment, up to a maximum limit of £3 billion.

Under UK fiscal rules, capital budgets may only be used to support long-term investment or maintenance that will extend the life of existing assets (such as bridges or hospitals) and cannot be used to fund additional “day-to-day” revenue spend. The Scottish Government can supplement its capital budget by diverting funds from its revenue budget, but cannot transfer funds from its capital budget to the revenue budget.

The total capital budget allocated by HM Treasury is 10.4% higher in 2019-20 compared with the previous year (in real terms). However, the increases in the capital budget in recent years follow significant contractions in the capital budgets in previous years. Between 2010-11 and 2015-16, the capital budget reduced by 24% in real terms.1

Financial transactions

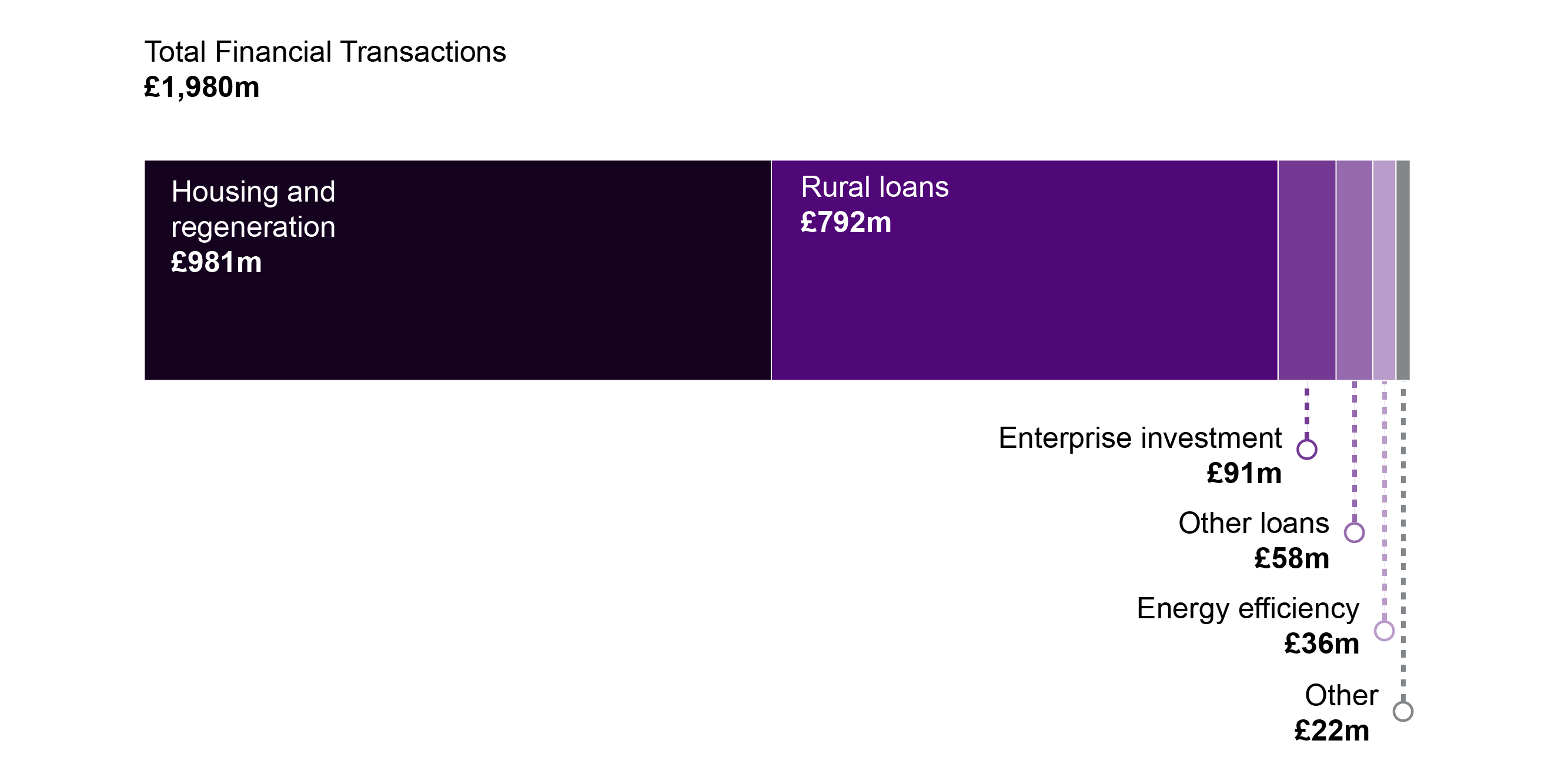

Financial transactions (FTs) are a type of financial allocation from the UK Government. They come with restrictions on how they can be used and must ultimately be repaid to HM Treasury. Over the period 2012-13 to 2018-19, the Scottish Government has received just over £2 billion in FT monies.

The Scottish Government can only use FTs to support equity or loan schemes beyond the public sector. This means that FTs cannot directly support public infrastructure projects, such as transport projects. However, they can be used where investment is led by private or third sector bodies. They have been used extensively to support house building, and the Scottish Government intend to use FTs to provide initial funding for the proposed Scottish National Investment Bank. 1 They have also been used to provide the sub-debt for hub projects which are privately classified and thereby support the funding of schools and hospitals.2

Borrowing powers

The Scotland Act 2016 increased the borrowing powers available to the Scottish Government. The capital borrowing limit was increased from £2.2 billion to £3 billion. The annual limit was also increased from 10% to 15% of the overall borrowing cap, in other words £450 million per year. The Scottish Government may borrow through the UK Government from the National Loans Fund, by way of a commercial loan or through the issue of bonds. The new limits came into effect from 1 April 2017.1

In 2015-16 and 2016-17, borrowing powers were used to provide budget cover for the NPD projects transferred to the public sector, including the Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route (see the end of revenue financing section for further discussion). This "budget cover" (also called notional borrowing) counts towards the overall capital borrowing cap, but does not have a cash impact on the Scottish Budget.2

In 2017-18, the Scottish Government used its capital borrowing powers in full (£450 million). The 2018-19 Draft Budget also set out the Scottish Government's intention to use the full £450 million capital borrowing powers in 2018-19. According to analysis set out in the Fiscal Framework: outturn report, the Scottish Government will have accumulated £1,459 million of capital debt by the end of 2018-19, representing 49% of the £3 billion limit.3 SPICe analysis suggests that the Scottish Government could continue to borrow the maximum amount of £450 million per year until 2022-23 before it would hit the £3 billion cap, assuming the repayment terms for future borrowing are similar to those for existing borrowing.

Revenue financing

The Scottish Government has supplemented the "traditional" capital budget through revenue-financed investment, primarily via the non profit distributing (NPD) and regulated asset base (RAB) models.

Type of revenue finance: public-private partnerships

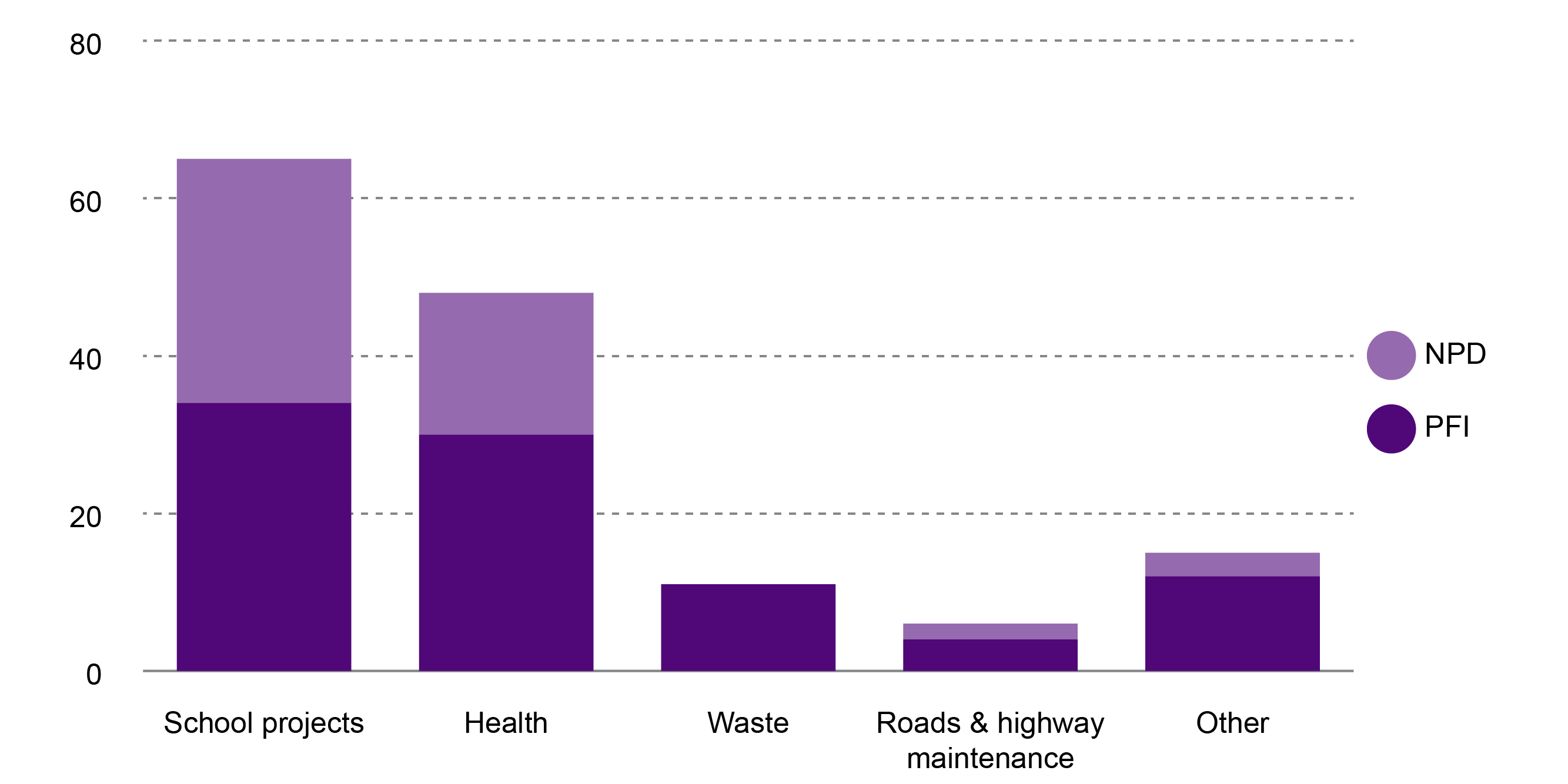

NPD is a form of 'public-private partnership' scheme designed to address some of the criticisms of excessive profits that had been levelled at the UK Government's Private Finance Initiative (PFI) scheme.

In a 'public-private partnership' the private sector pays the upfront capital costs of an infrastructure project, such as a school or hospital. Once the project is completed and in use, the public sector makes annual payments to the private sector contractor to cover construction costs, interest costs and maintenance/service charges, usually for 25-30 years. The payments come out of public sector revenue budgets, as opposed to capital budgets, thereby leaving the capital budget available for other projects and allowing for a higher overall level of investment than would be possible through traditional capital investment alone.

Between them, PFI and NPD have funded 145 projects in Scotland, with a combined capital value of over £9 billion. This includes 65 school projects and 48 hospitals and other health facilities. Note that an individual school PPP project can involve multiple school buildings within a single contract, so this figure does not reflect the total number of schools built with revenue financing, which will be considerably higher (and will include local authority led school projects, whereas these figures relate only to Scottish Government-led schools investment).

Future repayments for PFI and NPD projects are expected to represent around 2.6% of the annual total Scottish budget over the next four years.1

Due to changes to European accounting rules no new NPD projects are currently being considered (see the end of revenue financing section), but the Scottish Government has indicated that it intends to explore options for new "profit-sharing finance schemes" as a means to boost future infrastructure investment.2

Hub programme

Revenue financing for certain types of projects is continuing on a smaller scale via the 'hub programme'. The hub programme is a vehicle for the funding and delivery of community assets such as schools and health centres. Facilities are delivered by selected private sector partners working in partnership with public sector bodies through joint venture companies across five "hub territories". Projects delivered through the hub programme can be either capital or revenue funded.

The delivery structure of hub projects has been altered to include a charitable element, so that these projects comply with the new European accounting rules. This has allowed revenue financing to continue to an extent, although the type of project that can be funded via the hub programme is restricted. The hub programme is restricted to the participants named when the programme was first introduced (32 local authorities, 14 NHS Boards and smaller local bodies) and is intended for community infrastructure and primary healthcare. So, for example, major transport projects cannot be funded via the hub initiative.

In 2018-19, the value of revenue-funded hub programme investment was expected to total £150 million.1

Type of revenue finance: Network Rail borrowing

Regulatory Asset Base (RAB) is a form of revenue funding, whereby Network Rail pays for the upfront infrastructure costs by borrowing against its current assets and then repays the loans using payments from the Scottish Government over the lifetime of the asset (usually 30 years). This borrowing is regulated by the Office of Rail and Road (ORR).

RAB has been used to finance £687 million of investment in capital rail projects completed since 2007. The latest project pipeline suggests RAB will finance £1.5 billion worth of capital rail projects currently in construction. These projects are:

Edinburgh Glasgow Improvement Programme (EGIP)

Aberdeen to Inverness enhancements

Highland Mainline enhancements

Shotts electrification

Stirling, Dunblane, Alloa electrification.

The Scottish Government's five-year financial strategy estimated that future repayments to Network Rail are expected to represent about 1.3% of the annual total Scottish budget over the next four years.1 However, as a result of changes to European accounting rules, these payments will no longer take place. Network Rail has been reclassified from a private to public sector organisation and the debt will be held by the UK Government's Department for Transport and covered by HM Treasury. There will be no liability on the Scottish budget for the financing of this debt. This can be expected to significantly lower pressure on the Scottish Government's 5% repayment cap. Rail projects from 2019-20 will be entirely grant-funded.

Key features of Scottish Government finance options

The key features of the Scottish Government's funding options for capital projects is summarised below.

| Funding Type | Value of investment funded by this method in 2019-20 (£ million) | Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Capital DEL: grants | 4,020 | Capital budget determined by HM Treasury, but Scottish Government can supplement from revenue budget (including tax revenues) |

| Capital DEL: borrowing | 450 | Maximum of £450m per year and a cumulative cap of £3bn; any borrowing results in future repayment costs |

| Capital DEL: financial transactions | 636 | Value determined by HM Treasury and can only be used for equity and loan schemes beyond the public sector; must ultimately be repaid |

| Revenue finance: NPD | - | NPD project design not compatible with European accounting rules, so any projects would have to be included upfront in capital budget |

| Revenue finance: hub | 60 | Limitations exist on the types of projects that can be funded via the hub programme; projects will incur future repayment costs |

| Revenue finance: RAB | - | Network Rail's reclassification from a private to public sector organisation means no new RAB projects are being considered. Future rail projects will be grant-funded. |

| Revenue finance: other | - | The Scottish Government might explore new models of revenue financed investment and has referred to the Welsh Government's Mutual Investment Model. |

| Innovative finance e.g. Growth Accelerator/Tax Incremental Financing | 30 | Largely local authority led, but with some financial support from Scottish Government |

| Total | 5,196 |

Local Government grants and borrowing

Local Authorities also make major capital investments. Audit Scotland reported that council spending accounted for over half (53%) of total public sector capital spending in the three years between April 2012 and March 2015. Councils spent £7 billion in this period on schools, roads and transport, housing, sports, flood protection and other projects.1

The two largest sources of funding for council's capital budgets are:

capital grants from the Scottish Government

council's own borrowing.

In addition, councils fund capital projects through revenue financing, asset sales and other financing schemes. Councils use the hub programme to deliver community facilities though private finance. Some have agreed or are considering City Region Deals or "innovative" financing schemes like Tax Incremental Financing (see the innovative financing section). As a result, council capital investment is considerably higher than the Scottish Government capital grant. In 2018-19, Local Authority capital expenditure estimates totalled £3,475 million.2

City Region Deals

City Region Deals are agreements between the Scottish Government, the UK Government and councils to improve regional economies. For example, in August 2014, the two governments agreed to provide £500 million funding each, over 20 years, to the Glasgow and Clyde Valley City Deal, the first deal of its kind in Scotland.

Typically, the UK and Scottish Governments provide specific capital grants to city regions over ten to 20 years for infrastructure and economic development projects and the councils leverage further funds to supplement government grants.1 The Scottish Government's website provides details on the status of City Region Deals across Scotland.

In England, the package of city deals have included "devolution deals" where some powers (for example, aspects of further education, transport and EU structural funding) have been devolved to local governments.2 This has not happened in Scotland where deals have focused on growth funding.

Following the Enterprise and Skills Review3, the Scottish Government's policy emphasis is now on enabling a network of local authority led Regional Economic Partnerships (which is an umbrella term for a variety of deal formations – city deals, growth deals, Islands Deal, etc.):

In the Phase 2 report of our Enterprise and Skills Review published last year, we made it clear that the economic power and potential of Scotland's distinct regions must be harnessed. To ensure this potential is fully realised, we are working to enable formation of a network of Regional Economic Partnerships (REPs) covering Scotland. All growth deal activity sits within this evolving policy and operational context.

Scottish Government. (2018, March 13). Response to the Local Government and Communities Committee Report on City Regions: Deal or No Deal?. Retrieved from http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/CurrentCommittees/104236.aspx

SPICe has produced a briefing on City Deals5 while the Local Government and Communities Committee undertook an inquiry on City Deals and published a report in January 2018.6

Tax Incremental Financing and Growth Accelerator Model

The Scottish Futures Trust has worked with local authorities and private sector partners to develop some "innovative" financing schemes, known as Tax Incremental Financing and the Growth Accelerator Model:

Tax Incremental Financing (TIF) - Councils use borrowing to fund investments in public infrastructure with the aim of attracting further private sector investment. As a result of this, councils are expected to receive higher local tax income which they use to repay their borrowing.

Growth Accelerator (GA) - Similar to TIF, the GA model involves public sector investment that promotes further private sector investment. GA is based on a set of pre-agreed targets, such as generating a set number of additional jobs from low income areas or increasing revenue from Non-Domestic Rates and if met the Scottish Government pays a grant to the local authority over a set time period (typically 25 years). Where targets are not met, the local authority is paid a percentage of the grant depending on how close they were to achieving the target

Six pilot TIF schemes were developed through secondary legislation under existing provisions of the Local Government Finance Act (1992). Four of these are currently progressing:

Glasgow City Council - Buchanan Quarter

Fife Council - Energy Park, Fife and Fife Interchange

Argyll & Bute Council - Lorn Arc project

Falkirk Council - project to support commercial activity, manufacturing and distribution and support sectors in Grangemouth

One TIF project is under development in North Ayrshire.

The first GA project has been agreed with City of Edinburgh Council, for the St James Quarter, with up to £60 million of public sector investment accompanied by £850 million of new retail, leisure, hotel and residential development in the city centre. The success of the project is to be measured by growth in the immediate and wider property market, alongside inclusive growth priorities, through a number of targeted employment measures. Achieving these measures will unlock the availability of an annual grant from the Scottish Government.

A second GA project is underway with Dundee City Council for the Waterfront area of the city. Scottish Government investment of £60 million will support a project valued at £1 billion in total.

Future financing

How will projects in the pipeline be financed?

As described in pipeline section, the Scottish Government provides regular updates on infrastructure projects and programmes of infrastructure investment.

The Scottish Government's project pipeline shows that 57% of the value of projects in construction or in development is to be financed through capital grants, with 43% to be revenue financed. However, this split is very different when looking only at projects that are not yet in construction. Of projects in development, 76% of the value of projects are to be capital financed with only 24% revenue financed.1

| Projects in construction and development | Value (£ million) | Financing split |

|---|---|---|

| capital element | 2,573 | 57% |

| revenue element | 1,975 | 43% |

| total value | 4,547 |

| Projects in development only | Value (£ million) | Financing split |

|---|---|---|

| capital element | 743 | 76% |

| revenue element | 233 | 24% |

| total value | 977 |

No new (i.e. pre-construction) projects in the project pipeline are to be financed by NPD or RAB revenue financing. The longer-term programme pipeline is less definitive on the planned source of finance, but there is a heavy emphasis on capital grants for future projects.3

The UK Treasury has allocated £4.0 billion in capital funds to the Scottish budget in 2019-20. This represent a real terms increase of 10.4% compared with 2018-19 and will be supplemented with capital borrowing of £450 million. There is also scope to fund certain types of projects using FT financing, as discussed in the Financial Transactions section.

As such, there is an upper limit on the projects that can be financed through direct capital grants. There are also constraints on revenue financing, which are discussed in the five per cent cap on repayments section.

The end of revenue financing?

Revenue financing was developed as a way to increase infrastructure investment without increasing the type of borrowing that scored as public sector debt. PFI and NPD projects were classified as private sector projects and Network Rail was classed as a private sector body. This allowed governments to use revenue financing to increase investment without any upfront impact on their budget.

However, as a result of changes to European accounting rules, most revenue financed projects can no longer be treated as private sector projects. Their capital value now needs to be accounted for upfront out of the main capital budget. This means that the value of the investment needs to be included in the Scottish Government's capital budget in the year that it takes place (rather than being accounted for from future revenue budgets).

These changes have meant that the Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route (AWPR), the Dumfries & Galloway Royal Infirmary, the Royal Hospital for Sick Children/Department for Clinical Neurosciences and the Balfour Hospital in Orkney are now deemed to be public sector projects and their capital value has to be recorded against the capital budget, thereby limiting the capital funds available for other projects. The Scottish Government agreed with HM Treasury that it would use its borrowing powers to comply with the budgeting implications of the change. As a result, £283 million counted against the borrowing limit in 2015-16 and £333 million in 2016-17.

Revenue financing is still taking place as part of the hub programme for schools, health facilities and other community facilities This has been achieved by amending the delivery structure of these projects to include a charitable element. However, the type of projects that can be funded via hub companies is restricted. So, while revenue financing can continue to a certain extent, it cannot be used for all types of project. For example, major transport projects cannot be funded via the hub initiative.

This suggests less reliance on revenue financing for infrastructure investment in the future, although the Scottish Government has indicated that the potential for new profit-sharing finance schemes will be explored and has made reference to the Welsh Government’s mutual investment model (MIM) as a possible option.

The MIM is essentially a modified version of NPD, adjusted to ensure that projects funded through this route can be classified as private sector projects and so have no upfront impact on the capital budget. The main differences are:1

Public interest directors – NPD projects have a Public Interest Director (PID) nominated by the Scottish Futures Trust. Depending on the project, either the PID or the procuring authority has powers of veto as a result of holding a golden share in the project company. In MIM, the PID does not have power of veto over operational decisions.

Profit sharing – under NPD, there is no dividend-bearing equity and any surplus profits (above a fixed threshold) are returned to the public sector. Under MIM, dividends can be paid and the public sector can hold up to a 20% share in the equity (and therefore benefit from any dividend payments that are made)

Elsewhere in the UK, the Chancellor of the Exchequer announced at the November 2018 Budget that PF2 (the latest variant of PFI) would no longer be used to finance infrastructure projects in England. PF2 was described as "inflexible and overly complex" and the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has previously described PF2 as a source of significant fiscal risk to the UK government.2

Five per cent cap on repayment commitments

The Scottish Government is committed to spending no more than 5% of its total Departmental Expenditure Limit (DEL) budget on repayments arising from revenue financing and borrowing. This is a self-imposed fiscal rule. The 2019-20 budget announced that this rule would be tightened so that repayments cannot exceed 5% of the resource budget (excluding social security) from 2019-20.1

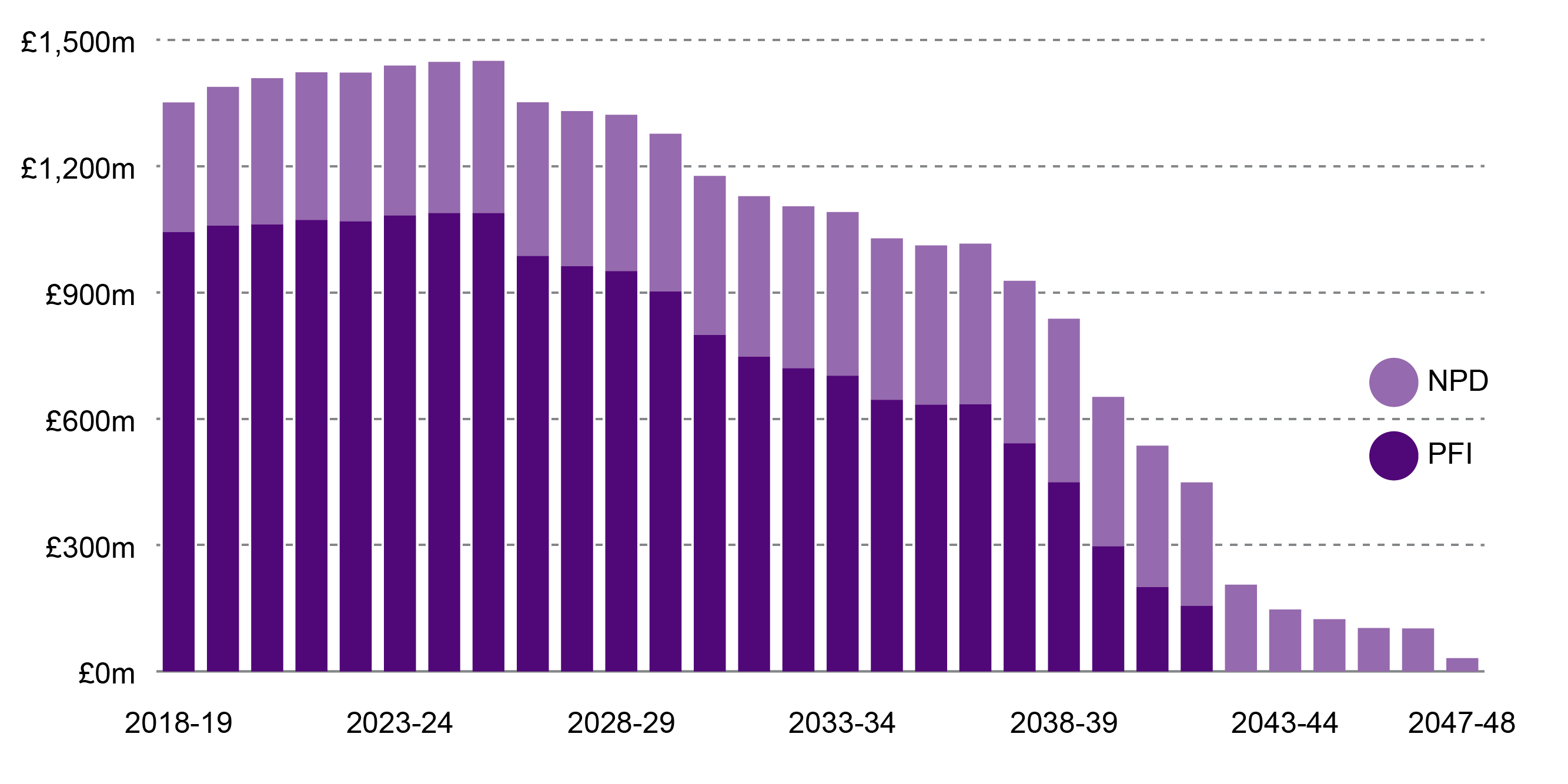

The Scottish Government's five year financial strategy estimated future repayments in light of this fiscal rule. PFI and RAB charges make up the bulk of repayments.2

| 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPP/ PFI | 1.94% | 1.93% | 1.85% | 1.81% | 1.72% |

| NPD/Hub | 0.63% | 0.67% | 0.80% | 0.81% | 0.80% |

| Network Rail Borrowing – RAB | 1.06% | 1.30% | 1.30% | 1.28% | 1.25% |

| Capital Borrowing | 0.11% | 0.21% | 0.28% | 0.27% | 0.27% |

| Total | 3.74% | 4.11% | 4.23% | 4.17% | 4.04% |

However, as discussed in the Network Rail borrowing section, as of 1 April 2019 Network Rail debt will be held by the UK Government's Department for Transport and covered by Treasury. Scottish Government RAB repayments will no longer be required. In addition, these figures do not reflect the changed baseline for the calculations. According to the 2019-20 Budget, under the new definitions and based on current commitments and plans, repayments will fall to just over 3% of the budget in 2019-20 and remain at or around that level until 2024-25.1

The repayment profile for all PFI, NPD and hub financed projects is shown in Figure X. These repayments amount to £1.4 billion in 2018-19 and outstanding repayments total £28.3 billion over the period to 2047-48, when current commitments will end.

Infrastructure "Mission"

As noted in the future choices section, the 2018-19 Programme for Government included significant commitments on future infrastructure investment, with a commitment to steadily increase annual infrastructure investment so it is £1.5 billion per year higher at the end of the next Parliament [2025-26] than in 2019-20.

However, no information was given on how this additional infrastructure investment will be funded, with the First Minister stating:

The Cabinet Secretary for Transport, Infrastructure and Connectivity will set out in the coming months the detail of how we will deliver on that pledge and the priorities for investment.

Scottish Parliament. (2018, September 4). Official Report. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11639&mode=pdf [accessed 27 November 2018]

The 2019-20 budget reiterated the commitment, setting out the ambition to increase infrastructure investment to £6,750.8 million by 2025-26. No details are provided on how the investment will be financed, other than saying that it will be a mix of capital grant, financial transactions, borrowing and innovative finance instruments. The Budget document also makes reference to asking the Scottish Futures Trust to examine the use of profit sharing revenue finance schemes, such as the Welsh Government’s Mutual Investment Model (which is a modified version of the Scottish Government’s non-profit distributing (NPD) model, adjusted so that projects can continue to be classified as private sector assets).2

On the basis of the central projections set out in the Scottish Government's Five Year Financial Strategy, the capital budget, financial transactions and borrowing will together provide for £5.2bn of capital investment in 2022-23, which is around £0.3 billion higher than in 2019-20 (assuming full use of borrowing powers).3 In order to reach the aspiration of increasing infrastructure investment to a level £1.5 billion higher than in 2019-20 by 2025-26 will therefore require additional investment of over £1 billion per year over and above the existing plans set out in the Five Year Financial Strategy.

Any further borrowing or revenue investment will result in repayment costs and/or unitary charges in future years. These additional costs will need to be taken into account in the Scottish Government’s commitment to keep these costs within 5% of the total budget. On current projections, long-term investment costs are anticipated to peak at 4.2% of the DEL budget in 2020-21, even before adjusting for the RAB projects that no longer need to be financed by the Scottish Government.

This leaves some headroom to accommodate additional repayment costs, equivalent to 0.8% of the budget. On the basis of current projections, this would mean that additional repayment/unitary charge costs of around £270m per year could be accommodated without breaching the commitment.

To put this in context, unitary charge payments on the Scottish Government’s current NPD projects are expected to total £270m in 2019-20 and this relates to projects with a combined capital value of £2.7bn. So, on the basis of the information available, there would appear to be scope for the Scottish Government to meet its infrastructure investment commitments through greater use of revenue-financed investment, making use of a modified version of NPD.

Plans for a Scottish National Investment Bank

The 2017 Programme for Government included a commitment to establish a Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB). An implementation plan was published in February 2018 and its recommendations accepted by the Scottish Government in March 2018.1

The SNIB will provide debt and equity finance to the private sector, rather than directly fund public infrastructure investment. Accepting the implementation plan, the then Cabinet Secretary for Economy, Jobs and Fair Work, Keith Brown said:

The new bank should be a public body, and it should operate independently within a strategic framework that has been set by the Government. It should be mission driven, it should focus on investment that is not currently provided by the market, and in a way that seeks to shape and to create markets, and it should address Scotland's economic priorities in an inclusive and ethical way.

The institution will operate on a commercial basis. It will offer debt and equity that should be repaid over 10 to 15 years. It will be independent from ministers, with the board deciding where to invest and on what terms... Ministers will set the bank's priorities, although the types of investment will be determined by the board. That should include strategic patient capital over all stages of firms and businesses’ investment life cycles, so that they are able to accelerate innovation and make a stronger contribution to the economy. It should include substantial financing for major projects that support regeneration and communities, and it should include investment in new ideas to help us to meet key economic, environmental and social challenges.

A bill to establish and capitalise the bank will be introduced in 2019. We aim to have the bank operating in shadow form in 2019, pending the passage of the bill.

Official Report. (2018, May 8). Meeting of the Parliament. Retrieved from http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11514&i=104477

The Implementation Plan recommends that the structure of the institution will more closely represent an asset management organisation, rather than a bank.1

Much of the Bank’s investment and lending activities with companies, will be through others. This requires fund management capability or the development of its own asset management structures. In order to reach growing firms, the Bank’s partnership working with the enterprise agencies in particular and other market participants will be essential.

A clear understanding of the remit of the Bank will be critical to its success, as will a focus on specific areas where it will operate. Several activities are excluded due to an inappropriate fit with the Bank’s remit and/or for operational reasons. These include:

· The Bank will not offer traditional banking services such as taking deposits or offering mortgages, and as such it will not require a network of branches

· It will not undertake funding activities, such as the awarding of capital and revenue grants which will remain with the Scottish Government and its agencies.

As the Bank will not be a deposit taking institution it will not require a banking licence.

Scottish Government. (2018, February 28). Scottish National Investment Bank: implementation plan. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-national-investment-bank-implementation-plan/

The Scottish Government has committed to providing £2 billion over 10 years to capitalise the SNIB. The 2018-19 budget committed to "guaranteeing an initial capitalisation of £340 million between 2019-21 for the Scottish National Investment Bank" through the planned allocation of financial transactions. The 2019-20 budget allocated £120 million for the SNIB. Additionally the Building Scotland Fund, described a precursor to the SNIB, has £50 million allocated to it in 2019-20.

A consultation on the Bank’s objectives, purpose and governance, as well as its relationship with Ministers and stakeholders was held and closed on 31 October 2018.5 Legislation is expected in 2019.

Balancing priorities and decision-making

Balancing competing priorities

Not all infrastructure investment will yield the same economic benefits either in the short-term or the long-term. Both the OECD1 and European Commission2 have published reports highlighting the differential impact of investment across different sectors. The OECD research found particularly strong effects for health investment, while the EC research emphasised the impact of electricity and transport investment on GDP.

Furthermore, certain types of investment might support different Scottish Government priorities – for example, an investment in road infrastructure might have positive employment impacts, but would score less well in relation to the Scottish Government's stated priority of fostering a lower carbon economy. Likewise, an investment that maximises economic growth will not necessarily deliver inclusive economic growth.

The Scottish Government's various priorities – which can be competing – must all be balanced when deciding on how best to spend limited capital budgets. There is also a balance to be struck between investment in large-scale national infrastructure projects and smaller scale local interventions that can be important in tackling inequalities. In addition, the need to spend money on maintaining existing assets needs to be considered alongside the demands for new assets within the context of constrained budgets. As noted by ICE:

Asset maintenance is a fundamental part of a resilient and productive Scottish infrastructure system.

Institution of Civil Engineers. (2018, November 8). State of the Nation Scotland 2018: Infrastructure Investment. Retrieved from https://www.ice.org.uk/ICEDevelopmentWebPortal/media/Documents/News/ICE%20News/State-of-the-Nation-Scotland-2018.pdf

Informed decision-making

Decisions on how to allocated a limited budget for infrastructure investment are not easy. As highlighted by the Institute for Government:

Making informed decisions about infrastructure investment is difficult. It requires robust analysis of the long-term effects of alternative infrastructure systems across a wide range of uncertain future scenarios. It involves understanding the drivers of demand for infrastructure services in the future, and how different infrastructure configurations might be able to meet that demand.

Institute for Government. (2014, December 12). The Political Economy of Infrastructure in the UK. Retrieved from https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/Political%20economy%20of%20infrastructure%20in%20the%20UK%20final%20v1.pdf [accessed 6 December 2018]

They also highlighted that the evidence base to inform decision-making is weak and that “conflicting interests, opinions and values make the politics of infrastructure investment especially difficult.”

The Institute of Economic Affairs noted concerns about the UK Government’s decision-making process in relation to infrastructure projects, commenting that:

Good infrastructure can enhance the productive potential of the economy, but the political decision-making process often leads to bad decisions on spending, whether that is for electoral reasons or inefficiencies driven by a lack of market discipline. For example, the 2010 Comprehensive Spending Review cancelled many strategic road schemes with benefit-cost ratios above 3, but pressed ahead with the planned HS2 with a benefit-cost ratio slightly above 1.

Specifically in relation to the Scottish Government's Infrastructure Investment Plan (IIP), CoST – the Infrastructure Transparency Initiative has said:

The IIP does not attempt to quantify an infrastructure gap and what would be needed in terms of investments to close it. Nor does it strategically assess the complex inter-relationship between needs, affordability, political priorities and implementation capacity.

CoST – the Infrastructure Transparency Initiative. (2018, July). Infrastructure Governance in Scotland. Retrieved from http://infrastructuretransparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/CoST-high-income-case-study-Scotland-1.pdf [accessed 4 December 2018]

Audit Scotland has also pushed for a more strategic approach for the IIP, saying:

The Scottish Government could extend the IIP to become an overarching investment strategy that would help:

Audit Scotland. (2011, January). Management of the Scottish Government’s capital investment programme. Retrieved from http://www.audit-scotland.gov.uk/docs/central/2010/nr_110127_capital_investment.pdf [accessed 4 December 2018]

set out the long-term investment needs and constraints for capital investment in Scotland

provide key information to help Scottish ministers decide on priorities within the capital programme

identify, coordinate and inform investment plans across the main capital spending areas

provide clear links between projects, programmes and strategic objectives

provide a strategic assessment of the revenue financing options available to it, in the light of the coming reductions in the capital budget

provide high-level analysis of the overall condition of the public sector estate. Without such information, it will be difficult to establish the correct balance between building new infrastructure and maintaining current assets

strengthen debate within the public sector on the direction of the capital programme.

In their 2015 review of Scotland’s infrastructure, ICE acknowledged that:

…improvements have been made in some sectors since our last report in 2011, and…strategic infrastructure planning and investment are beginning to deliver tangible results.

However, in their assessment of current infrastructure, no sector was considered to have infrastructure provision that was “fit for the future”. The best performing sectors were strategic transport and water, which were assessed as “adequate for now”. ICE also commented that:

…the question of who will design and deliver Scotland’s future infrastructure is vital. Scotland will require a skilled and sufficiently plentiful workforce to continue to deliver high quality and reliable infrastructure into the future. Upskilling our existing workforce, attracting a new generation to the engineering profession and diversifying the workforce will all contribute to creating a dynamic, flexible workforce.

Economic impact

Short-term impacts

Infrastructure investment will have both short-term and longer-term impacts on the economy. The short-term impacts are relatively easy to measure and result from the construction phase of the project, generating jobs both directly through the construction activity and indirectly through purchasing and supply chains. The Major Capital Projects updates provide some information on anticipated local economic benefits for each project.

The Scottish Government estimates that each additional £100m of public sector capital spending in 2017‑18 supports approximately 800 full time equivalent jobs in Scotland, around half of which are in construction. This is one reason why capital projects are often seen as a means to generate economic activity in times of weak economic growth. For example, the Scottish Government introduced a capital acceleration programme in 2008-09 following the global financial crisis and again following the Brexit vote.

The 2015 IIP acknowledges the positive role to be played by infrastructure investment, stating that:

…it is well known that well planned investment in new or existing infrastructure can play a central role in improving competitiveness and driving inclusive economic growth. Over the period of the global recession, the Scottish Government has sought to deliver additionality in its infrastructure investment programme, maintaining overall levels of investment and supporting thousands of jobs. In doing so, the Scottish Government has sought to maximise impact and value for money for tax payers and society as a whole.

Scottish Government. (2015, December 16). Infrastructure Investment Plan 2015. Retrieved from https://beta.gov.scot/publications/infrastructure-investment-plan-2015/

Long-term impacts

In addition to the short-term impact of infrastructure investment, there are potential long-term economic gains that can result from effective infrastructure investment. These longer-term effects result from an increase to the productive potential of the economy. The World Economic Forum reported that:

…public infrastructure investment can have powerful effects on the macroeconomy. It raises output in the short term by boosting demand and in the long term by raising the economy’s productive capacity. In a sample of advanced economies, a 1 percentage point of GDP increase in investment spending raises the level of output by about 0.4 percent in the same year and by 1.5 percent four years after the increase. In addition, the boost to GDP a country gets from increasing public infrastructure investment tends to offset the rise in debt, so that the public-debt-to-GDP ratio does not rise. In other words, public infrastructure investment could pay for itself, if done correctly.

Other studies have found similar positive long-term impacts from increased infrastructure investment. A recent report by the Scottish Government on the economic rationale for infrastructure investment provides a summary of a range of empirical studies.1

While acknowledging the positive role to be played by infrastructure investment, there are also widespread views that governments in general are under-investing. The LSE’s Growth Commission report, referring to the UK as a whole, commented that:

…the provision of infrastructure now constitutes a persistent and major policy failure, one that generations of governments from all parties have failed to address.

…In spite of the evidence that low investment in skills, infrastructure and innovation imposes major constraints on growth, poor policies persist along with institutions that fail to provide long-term frameworks for investment and action. The result is that although there were improvements before the crisis, UK productivity levels still lag behind other major countries. In 2011, UK GDP per hour was 27 per cent below the level in the US, 25 per cent behind France and 22 per cent behind Germany.

LSE Growth Commission. (2013). Investing for Prosperity: Skills, Infrastructure and Innovation. Retrieved from http://www.lse.ac.uk/researchAndExpertise/units/growthCommission/documents/pdf/LSEGC-Report.pdf [accessed 3 December 2018]

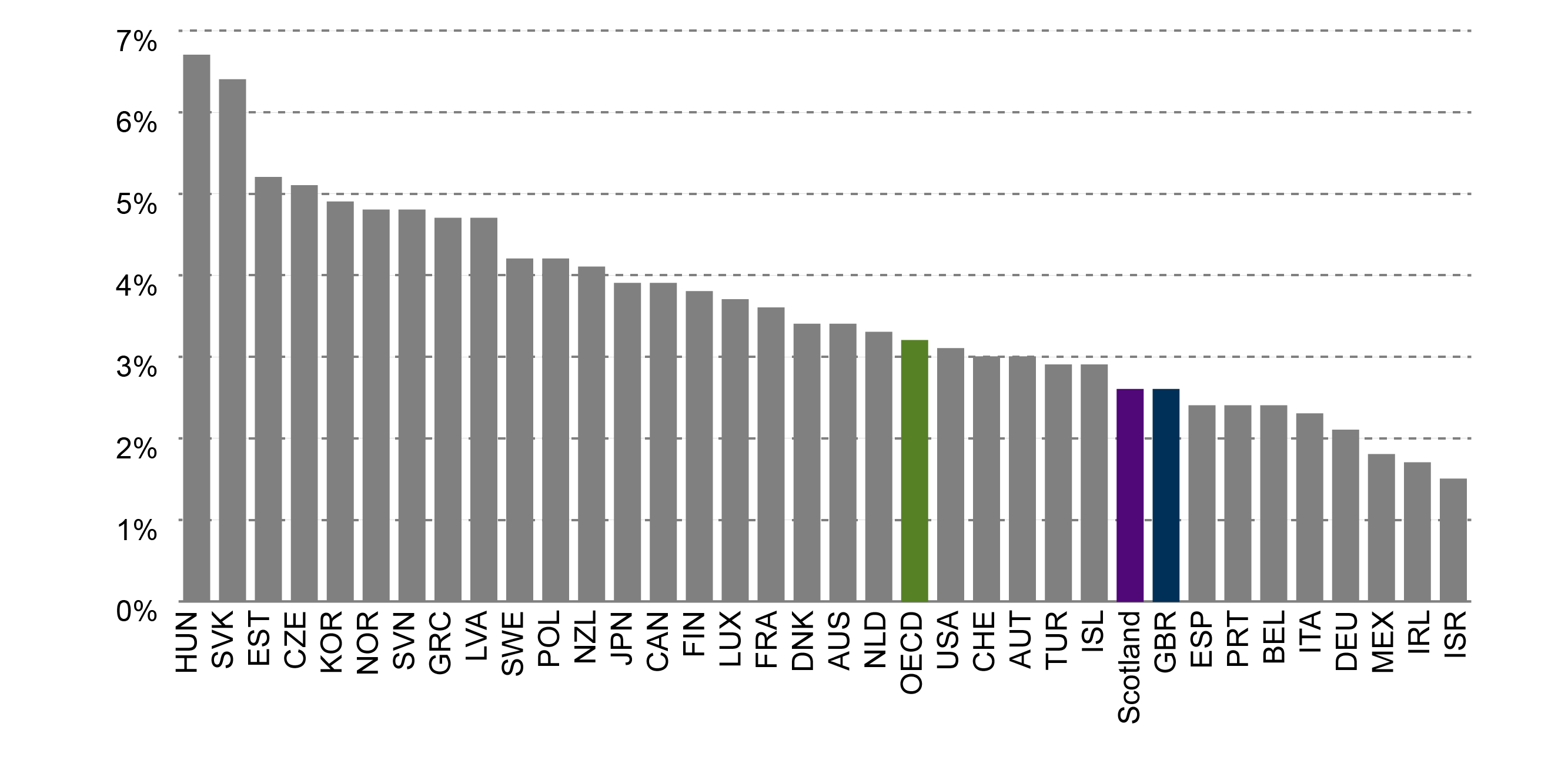

The Fraser of Allander Institute3 and Scottish Government1 note that levels of capital investment in both Scotland and GB as a whole are low by international standards.

However, the Fraser of Allander Institute also note the commitment made as part of the Programme for Government and the effect this, if achieved, would have on international comparisons:

The 2018 Programme for Government set out an aim to raise Scotland’s infrastructure spending to ‘internationally competitive levels’. This aspiration is not explicitly defined.

Indicatively, for net investment to reach the OECD average of 3.1% of GDP would require around an increase of around £800m in today’s prices. The Programme for Government sets out an ambition that investment in infrastructure should be £1.5bn higher in 2025/26 than in 2019/20.

Fraser of Allander Institute. (2018, November). Scotland's Budget Report 2018. Retrieved from https://www.sbs.strath.ac.uk/economics/fraser/20181108/Scotlands-Budget-2018.pdf

The Scottish Government also notes in its research that the gains to be had from increased infrastructure investment are greater where the existing stock and quality of infrastructure is lower.1 Using economic modelling, the Scottish Government estimates that, if delivered, the increase in infrastructure investment promised as part of the 'infrastructure mission' would result in the Scottish economy being between 0.5% and 1% larger than it would otherwise have been by 2025-26, assuming that levels of investment are sustained at the new increased level. Over 15 years, this is equivalent to increasing the economy by between £10 billion and £25 billion (at 2017 prices), according to the Scottish Government.

Social impact

In addition to the economic impact of infrastructure investment, the Scottish Government's 2015 Infrastructure Investment Plan makes reference to the wider ambitions of such spending:

Our investment in infrastructure aims to address inequalities in society and also to promote equality in terms of protected characteristics, including gender, ethnicity, disability and age. While some progress has been made against a range of indicators, we still need to do more to address the structural causes of inequality.

Infrastructure investment in general improves access to labour markets, supports increased participation and reduces inequality by making employment opportunities more accessible. It is also important in terms of which communities benefit from investment and how that benefit is distributed. This plan supports the aim of tackling inequality through an overall approach that balances economic and social investment and reflects our strategic aim to create a fairer Scotland.

Scottish Government. (2015, December 16). Infrastructure Investment Plan 2015. Retrieved from https://beta.gov.scot/publications/infrastructure-investment-plan-2015/

As such, a focus on economic impact in isolation will not necessarily reflect government priorities. The ‘What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth’ considered more than 2,300 transport policy evaluations and evidence reviews from the UK and other OECD countries and concluded that the evidence on economic impact was mixed. However, they concluded that this in itself was not necessarily a reason for not undertaking the investment, saying:

Overall, the impact of transport investment on employment is mixed (for road) or unknown (for rail, bus, tram, and cycling). However, there are good reasons to invest in transport infrastructure beyond the impact on local growth.

Recent research from the Scottish Government also highlighted the potential social impacts of infrastructure investment, through reducing regional disparities:

Infrastructure has a geographic dimension through agglomeration, improving regional connectivity and improving accessibility (for example through providing new economic opportunities to remote and deprived communities). For example, expanding rural broadband offers new opportunities for remote businesses. Likewise, improvements to the public transport network (e.g. Borders Railway) allow residents in more remote locations to commute to economic hubs such as Edinburgh or Glasgow. These links also make rural communities more attractive places for skilled workers to live, who in turn can support the local economies.2

Climate impact

Infrastructure is important in tackling climate change because the types of transport, housing or energy invested in today will last for many years, and thereby lock-in a pattern of future greenhouse gas emissions.

infrastructure that countries and cities construct today will lock in economic and climate benefits – or costs – for decades to come

Coalition for Urban Transitions, PwC, LSE. (2017, October). Financing the Urban Transition: Policymakers’ Summary. Retrieved from https://newclimateeconomy.report/workingpapers/workingpaper/financing-the-urban-transition-policymakers-summary/

Despite its importance, our understanding of the impact of current infrastructure plans on future greenhouse gas emissions is poor.

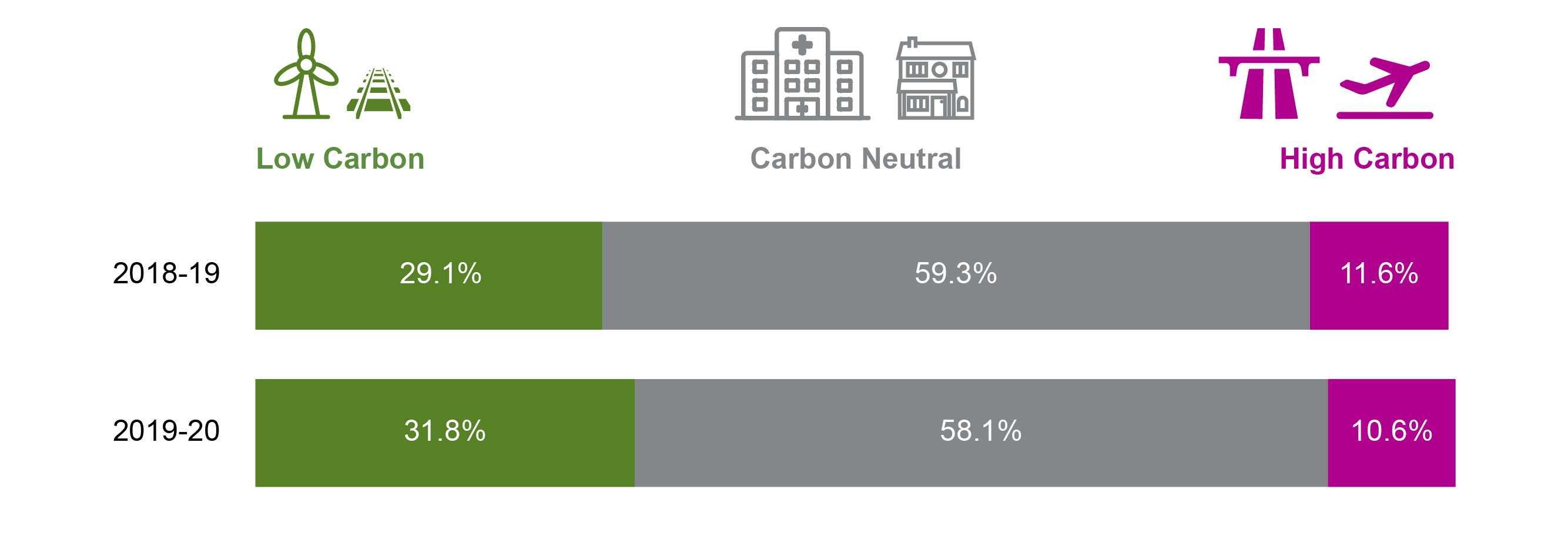

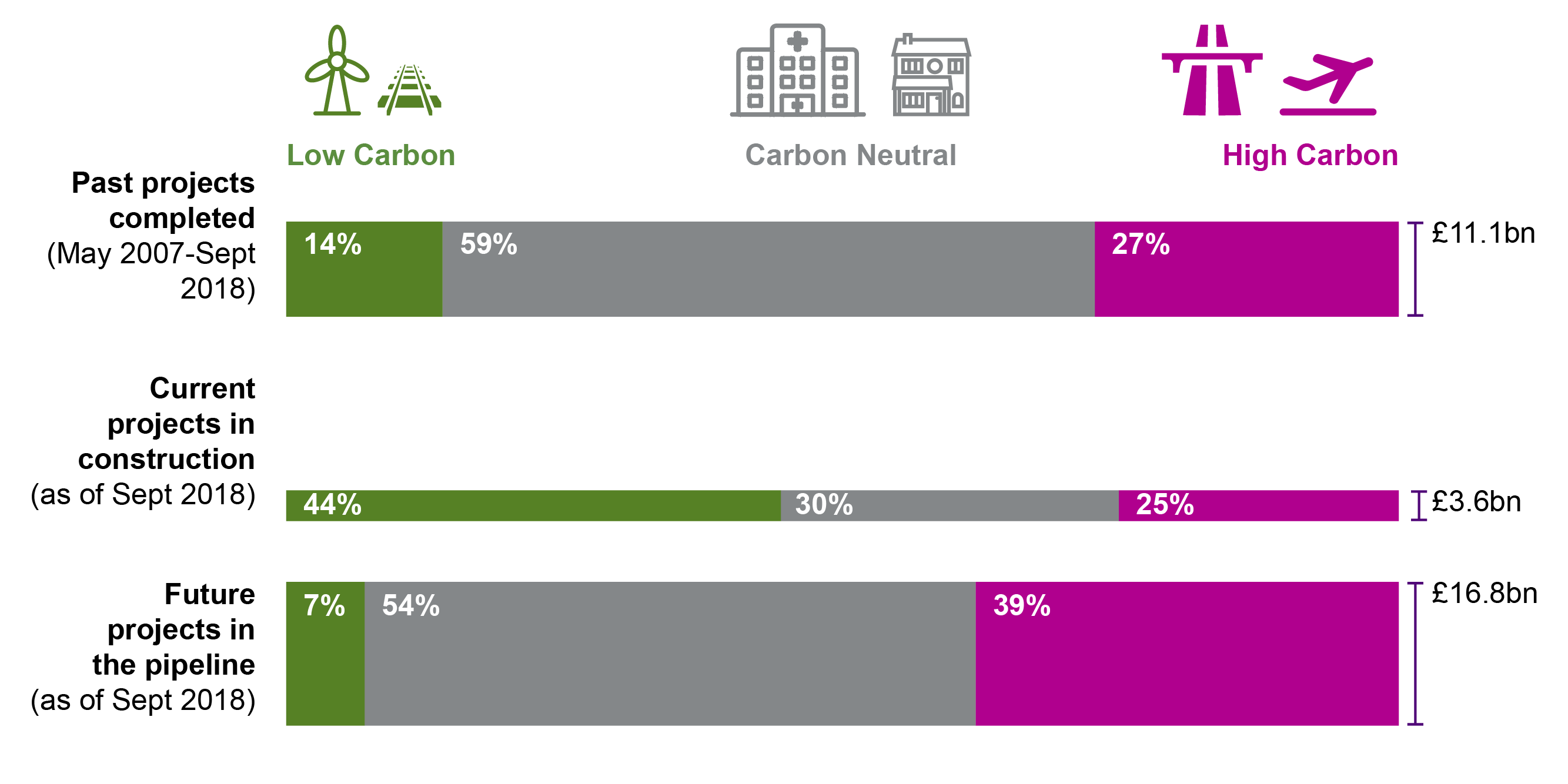

For the last two budgets, the Scottish Government has published high-level analysis on the balance of annual infrastructure spend that can be classed having a broadly positive, negative or neutral effect on future emissions. This analysis does not assess the scale of the impact, it only categorises it - for example, spending on a rail project is classed as low carbon (i.e. it is expected to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the long-term), while spending on a motorway project is classed as high carbon (i.e. it is expected to increase greenhouse gas emissions in the long-term).

The Government's analysis indicates that the proportion of infrastructure spend classed as low carbon in the 2019-20 Budget is 32% while the proportion of infrastructure spend classed as high carbon is 10%. This is a small increase in low carbon and small reduction in high carbon proportions compared with the previous year.

SPICe have mirrored the Scottish Government's methodology but applied it the most recent infrastructure pipeline updates. This provides a longer-term view of the Scottish Government's past, present and future infrastructure projects for several years into the future. The limitations of this analysis are that only large-scale government-led projects (£20m+) are captured and the actual projects financed in each year in the future will depend on decisions made in the annual budget process.

This SPICe analysis suggests the Scottish Government's investment in projects expected to increase emissions will increase, while investment in projects expected to decrease emissions will decrease.

The proportion of project value currently in construction classified as low carbon is 44% (6 projects). The proportion of low carbon project value in the pipeline falls to 7% (6 projects).

The proportion of project value currently in construction classified as high carbon is 25% (3 projects). The proportion of high carbon project value in the pipeline rises to 39% (5 projects).

This SPICe analysis is based on the infrastructure pipeline as updated by the Scottish Government in September 2018. The Government have indicated they intend to publish a new Infrastructure Investment Plan in light of advice from its newly proposed Infrastructure Commission.

Value for money

Measuring the value for money achieved through infrastructure investment is complex. This is partly because, as outlined above, a government might be pursuing a range of different objectives through its capital spending programmes. In this respect, the lowest cost option might not deliver best value for money if it does not meet certain quality standards. Furthermore, the government might be pursuing social or environmental aims which might have higher cost implications.

At the project development stage, value for money considerations should be built in to the project assessment process. The Scottish Futures Trust (SFT) produces guidance on achieving value for money and has a role in promoting value for money.2 The SFT's aim is described as:

to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of infrastructure investment and use in Scotland by working collaboratively with public bodies and industry, leading to better value for money and ultimately improved public services.

Scottish Futures Trust. (n.d.) About Us. Retrieved from https://www.scottishfuturestrust.org.uk/page/the-scottish-futures-trust [accessed 14 January 2019]

Audit Scotland also has a remit for ensuring that value for money is achieved in public spending across Scotland. In pursuit of this objective, Audit Scotland reviews major programmes of public spending and major projects. For example, Audit Scotland is currently undertaking a review of the value for money of NDP projects and is also reviewing City Deals. Both reports are due for publication in 2019.4 In the past, Audit Scotland has reviewed the value for money of major infrastructure projects, including the Forth Replacement Crossing.5

Governance for infrastructure

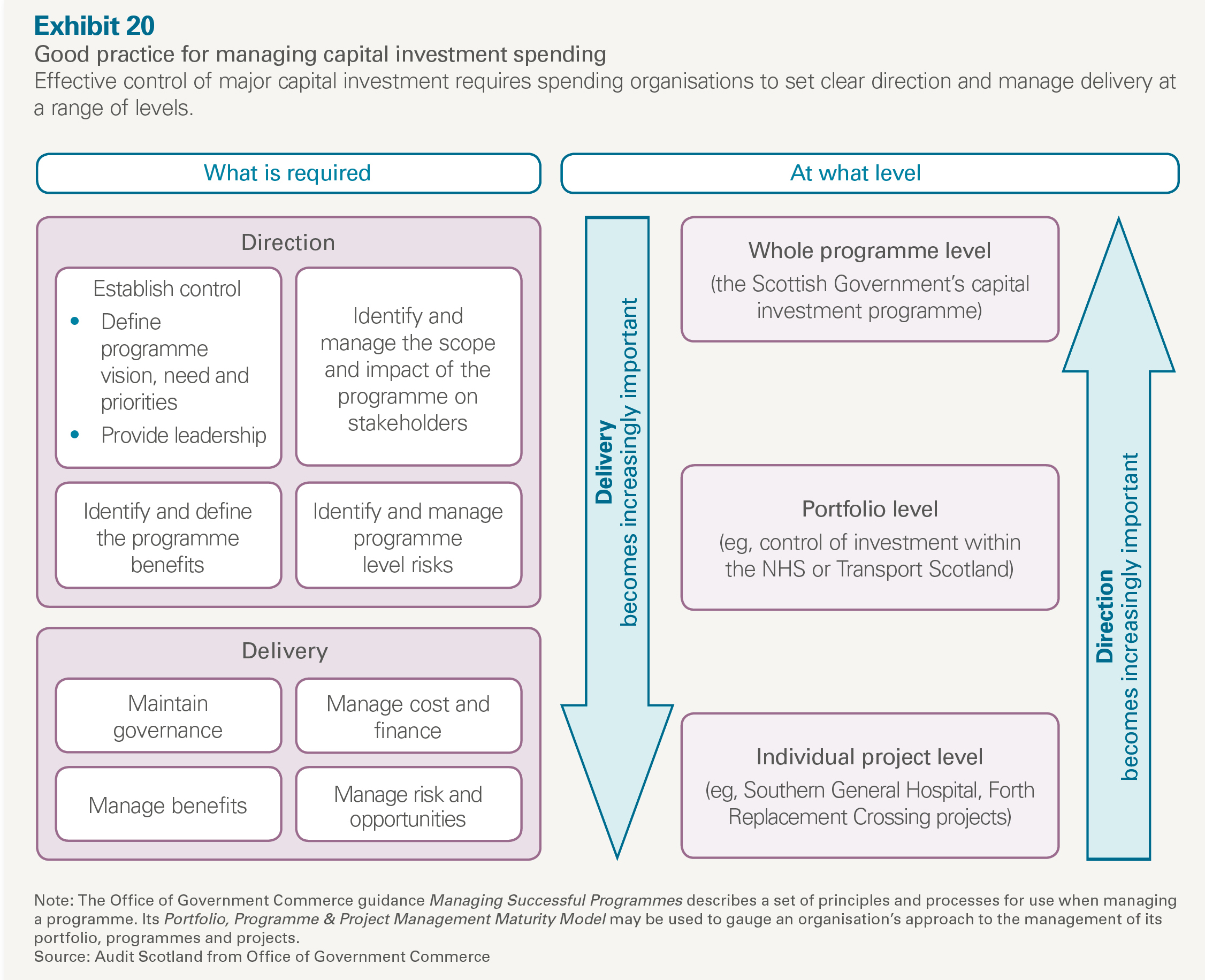

Audit Scotland identifies three “levels” of governance required for the management of capital investment spending:

whole programme level (i.e. the capital investment programme)

portfolio level (e.g. control of investments within the NHS or Transport Scotland)

individual project level

The roles that key government and public sector actors play in infrastructure governance are mapped in Table 5.

| Organisation | Description of role |

|---|---|

| Scottish Government - Ministerial | Within the current Scottish Government Cabinet, responsibility for:

|

| Scottish Government - Infrastructure Investment Board | The Infrastructure Investment Board (IIB) is made up of senior civil servants. The IIB remit is to provide governance for the investment programme. Its membership and May 2018 terms of reference are available on the Scottish Government's website. |

| Scottish Government - Directorates and Public Bodies | Directorates and public bodies who play a key role in public infrastructure investment include:

|

| Local Government | Local Government's role in borrowing and investing in major capital projects is described in the Local Government grants and borrowing section. Councils accounted for over half of total public sector capital spending in the three years between April 2012 and March 2015. |

| Scottish Futures Trust | Scottish Futures Trust (SFT) is an infrastructure delivery company owned by the Scottish Government. Working with Local Authorities and NHS Boards, SFT operate the hub procurement model described in the Hub programme section. |

| Audit Scotland | Audit Scotland support the Auditor General for Scotland and the Accounts Commission to audit all public bodies in Scotland. The audits aim to ensure that public money is spent properly, efficiently and effectively.All relevant Audit Scotland report and future work plans are published on its investment and infrastructure e-hub. |

| Public Audit and Post-legislative Scrutiny Committee | The Scottish Parliament's Public Audit and Post-legislative Scrutiny Committee (PAPLS) receive reports from Audit Scotland and scrutinise public spending.PAPLS and Audit Scotland regularly scrutinise the Scottish Government's infrastructure pipeline updates. |

European Investment Bank

The European Investment Bank (EIB) is an investment bank that is jointly owned by EU Member States. The Bank borrows money on capital markets and lends it on favourable terms to projects that support EU objectives. It is the world's largest multilateral lending institution and plays a role in large-scale infrastructure projects across the UK.

The EIB publishes data on every loan, but not at a Scotland level. SPICe have used the EIB database to identify loans worth €2.0 billion made since the start of 2016 for projects evidently within Scotland, but this may not be a complete list.

Lending to projects in Scotland signed since 2016 includes:

€682 million to Beatrice Offshore for the construction of Scotland's largest offshore windfarm

€611 million to SSE Caithness-Moray for a major reinforcement of the electricity transmission network required for renewable energy schemes.

€210 million to Wheatley Group for the retrofit of existing social housing to meet energy efficiency standards, the construction of new low-carbon social housing and the provision of housing and integration for refugees.

In its evidence to a committee inquiry in Westminster, the Scottish Government said:

EIB has been an important and strategic partner for privately-financed infrastructure projects in Scotland which make a significant contribution to growth, employment, economic and social cohesion. EIB debt finance of £665 million, over one third of total senior debt, has supported City of Glasgow College; M8, M73 and M74 Motorway improvements; Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route; NHS Dumfries and Galloway Acute Services Redevelopment; and the Royal Hospital for Sick Children in NHS Lothian.

Scottish Government. (2018, October 11). Written evidence to the EU Financial Affairs Sub-Committee's inquiry on Brexit: the European Investment Bank. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/lords-select/eu-financial-affairs-subcommittee/inquiries/parliament-2017/brexit-the-european-investment-bank/brexit-the-european-investment-bank-publications/

According to the Institute for Government, Scotland has received more EIB finance per capita than any other region in the UK outside of London over the years 2001-2016.2

What will happen after Brexit?

The draft Withdrawal Agreement's terms state that the UK will not be a member of the EIB after March 2019, and that the UK's paid-in capital will be reimbursed in tranches. This means that the UK will leave the EIB, and UK-based projects will be unable to access EIB finance after March 2019, unless a specific agreement to maintain a relationship is negotiated.

The Political Declaration describing the framework for a future relationship between the UK and the EU, states:

the Parties note the United Kingdom's intention to explore options for a future relationship with the European Investment Bank (EIB) Group.

UK Government. (2018, November 22). Political Declaration setting out the framework for the future relationship between the European Union and the United Kingdom. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/758557/22_November_Draft_Political_Declaration_setting_out_the_framework_for_the_future_relationship_between_the_EU_and_the_UK__agreed_at_negotiators__level_and_agreed_in_principle_at_political_level__subject_to_endorsement_by_Leaders.pdf [accessed 27 November 2018]

The Political Declaration adds no further detail and is silent on the EU's position.

On a future relationship with the EIB, the Scottish Government states:

Alongside considering longer-term access to EIB capital and expertise, and retaining Scotland's EIF shareholding, Scottish Ministers call on the UK to allocate a proportion of repatriated capital to those devolved development institutions seeking to deliver those same infrastructure support and inclusive economic growth objectives as EIB. That way the original purpose of the EIB capitalisation funded by tax-payers might be protected and enhanced on a more evergreen basis, across the UK.

Scottish Government. (2018, October 11). Written evidence to the EU Financial Affairs Sub-Committee's inquiry on Brexit: the European Investment Bank. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/lords-select/eu-financial-affairs-subcommittee/inquiries/parliament-2017/brexit-the-european-investment-bank/brexit-the-european-investment-bank-publications/

The UK Government's independent advisors, the National Infrastructure Commission recommends that:

If access [to the EIB] is lost, a new, operationally independent, UK infrastructure finance institution should be established by 2021.

National Infrastructure Commission. (2018, July). National Infrastructure Assessment 2018. Retrieved from https://www.nic.org.uk/publications/national-infrastructure-assessment-2018/

Annex: Major areas of infrastructure investment

Transport

How much has been invested?

Since 2007, the Scottish Government has invested a total of £7.1 billion in transport projects. The largest of these are:

Forth Replacement Crossing (£1.4 billion)

Edinburgh Glasgow Rail Improvement Programme (£858 million)

Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route (£745 million)

M74 completion (£692 million)

Edinburgh Trams project (£500 million).

What is in the pipeline?

Both the Edinburgh Glasgow Rail Improvement Programme and Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route (£745 million) remain in the Scottish Government's project pipeline as work is ongoing on these projects. In addition, the pipeline includes nine further transport projects, including:

Aberdeen to Inverness Rail Improvement Project (£330 million)

Stirling Dunblane Alloa Rail Electrification (£125 million)

Shotts Electrification (£120 million).

How are decisions made?