Fuel Poverty (Target, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Bill

The Scottish Government introduced the Fuel Poverty (Target, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Bill on 26 June 2018. It sets a new target relating to the eradication of fuel poverty, as well as setting out a revised definition of fuel poverty. Other provisions relate to the production of a fuel poverty strategy and reporting requirements.

Executive Summary

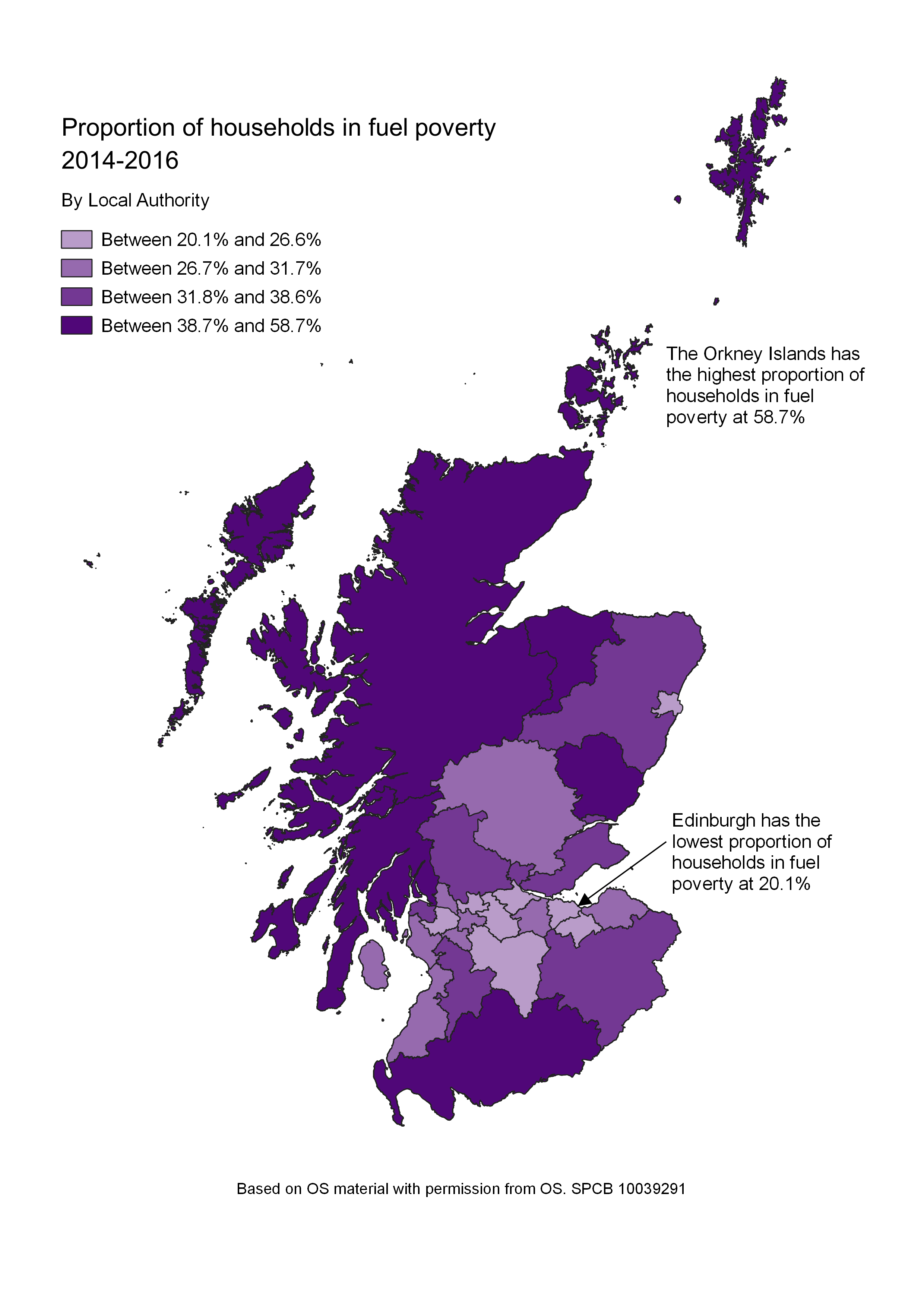

Scotland is an energy-rich country, yet over a quarter of households live in fuel poverty (using the current definition). This rises to over 50% of households in some local authority areas, such as Orkney Islands and Na h-Eileanan Siar.

In 2002, the then Scottish Executive set a target to eradicate fuel poverty by 2016. This target was not met.

The policy focus of successive devolved governments has been on improving the energy efficiency of homes. However, rising energy costs have meant that fuel poverty levels are significantly higher now than when the previous target was set in 2002.

The Scottish Government commissioned an expert panel to examine the current definition of fuel poverty and make recommendations on how it could be improved.

The panel made a number of suggestions, most of which were accepted by the Government.

After some consultation, the Scottish Government introduced the Fuel Poverty (Target, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Bill in June 2017. As is clear from its title, the Bill will:

1. Set a new target for the reduction of fuel poverty:

The Bill sets out the target of reducing the proportion of Scottish households in fuel poverty to no more than 5% by 2040. Applying the new definition to 2016 data, the rate currently stands at 24%1.

2. Provide a new definition of fuel poverty:

The new definition calculates the proportion of household income required to maintain a satisfactory level of heating and meet the household's other reasonable fuel needs within the home and assesses the extent to which households can then maintain an “acceptable standard of living” once housing and fuel costs are deducted1.

3. Require the Scottish Government to publish a fuel poverty strategy, and report on its progress every five years.

Within a year of Section 3's enactment, the Scottish Government must publish its long-term fuel poverty strategy setting out an approach to tackling fuel poverty, as well as documenting how it will report on progress towards the 2040 target1.

The long title of the Bill is: "A Bill for an Act of the Scottish Parliament to set a target relating to the eradication of fuel poverty; to define fuel poverty; to require the production of a fuel poverty strategy; and to make provision about reporting on fuel poverty".

It is worth noting that 5% of all households in 2040 could be equal to around 140,000 homes. The Scottish Government believes a 0% target may be unrealistic and unachievable.

The Scottish Government acknowledges that two of the main drivers of fuel poverty - energy prices and household incomes - are largely outwith their control.

There is no mention in the Bill of there being any consequences should the target be missed.

The new definition is certainly more complicated than its predecessor; however, it is is also a genuine attempt to help policy-makers better identify and support households in financial hardship.

The use of the Minimum Income Standard and before housing cost calculations in the proposed definition represents a radical departure from what has gone before.

The Scottish Government does not need legislation in order to introduce a new target, definition or fuel poverty strategy.

The accompanying Financial Memorandum does not include estimates of how much eradication/reduction of fuel poverty is likely to cost.

A Draft Fuel Poverty Strategy was published at the same time as the Bill was introduced.

Introduction

The Scottish Government's overarching ambition for its Fuel Poverty (Target, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Bill1 is "to see more households in Scotland living in well-insulated warm homes, accessing affordable, low carbon energy; and having an increased understanding of how best to use energy efficiency in their homes"2. Setting a new target and definition is part of the Scottish Government's approach to addressing fuel poverty, which will include a new fuel poverty strategy and, possibly, a related Energy Efficient Scotland Bill later in the Parliamentary session.

The primary aim of this briefing is to assist Members of the Scottish Parliament, in particular members of the Local Government and Communities Committee, to scrutinise the Bill and understand what it is trying to achieve. The paper summarises the context in which the Bill has been introduced, explains its provisions in some detail and sets out why the Scottish Government believes introducing legislation is the best way to progress.

Background - statistics and policy

Fuel poverty, a persistent problem for hundreds of thousands of Scottish households, is driven by three main factors: energy costs, energy efficiency and household incomes. Over recent years, a fourth driver has been identified, closely related to energy efficiency: how households use the energy they buy1.

Eradicating fuel poverty has been a policy aim of all devolved Scottish administrations. In a country as energy-rich as Scotland - abundant in renewable energy sources, as well as oil, gas and coal - it is striking that around a quarter of all households struggle to heat their homes to a satisfactory level2.

Previous target

The 2002 Fuel Poverty Statement1, published under section 88 of the Housing (Scotland) Act 20012, committed Scottish ministers to ensuring, "so far as reasonably practicable, that people are not living in fuel poverty in Scotland by November 2016”. We now know that this target has not been met, as acknowledged by Minister for Local Government and Housing, Kevin Stewart, during a Committee session in June 2016:

“…despite the Scottish Government’s significant investment of over £0.5 billion since 2009 in our fuel poverty and energy efficiency programme, the ambitious target to eradicate fuel poverty by November will not be met”.

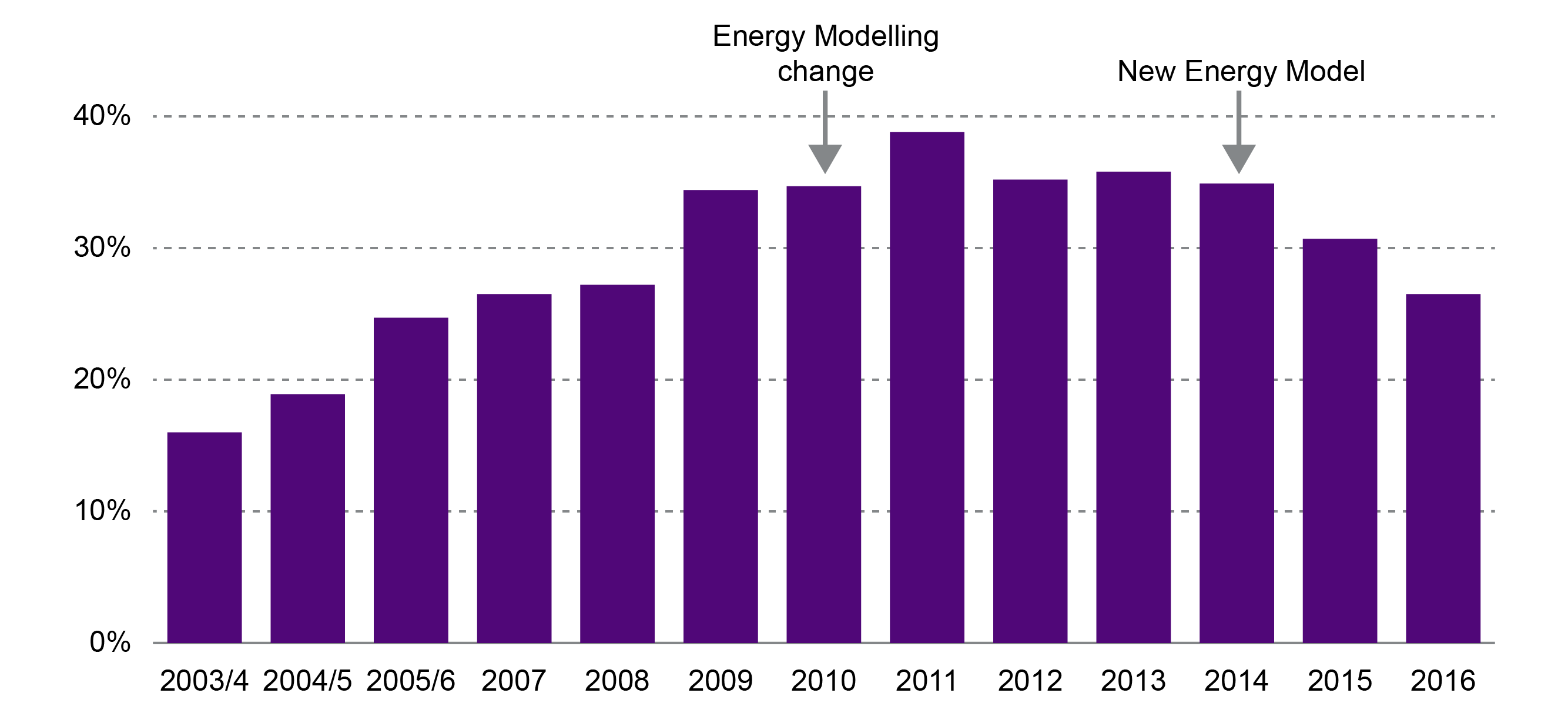

Indeed, Scottish House Condition Survey (SHCS) figures show that 649,000 households, 26.5% of all Scottish households, were in fuel poverty in 2016 – the lowest rate since 2007 but still a very long way from eradication.

Fuel poverty rates across Scotland

Fuel poverty rates under the current definition vary across the country, ranging from 20% of households in Edinburgh to 59% in the Orkney Islands1. The following map shows that predominantly rural and island local authority areas such as the Western Isles and the Highlands have far higher rates than most urban or suburban areas.

Scottish House Condition Survey

The Scottish House Condition Survey (SHCS) has been used to measure fuel poverty levels since the 1990s. It is based on a survey of approximately 3,000 households and is conducted annually, with reports published each December containing national results and results by different households and dwelling characteristics. Publication of Local Authority results usually follow in the spring. The SHCS is a National Statistics publication for Scotland, complying with the Official Statistics code of practice, i.e. it is produced, managed and disseminated to high standards.

Gathering data

Since 2012, the survey has been incorporated as a module of the Scottish Household Survey (SHS), with approximately one third of sampled households invited to participate in a follow-up inspection by SHCS building surveyors. For the past few years, the Scottish Government has contracted research specialists, Ipsos-Mori, to conduct the Survey.

A randomly selected sample of households from across Scotland is drawn by the Scottish Government. These households are then contacted in advance and visited by trained interviewers who complete a questionnaire with the householder covering a whole range of topics . Areas of the questionnaire most relevant to the fuel poverty measurement are those on household incomes and housing costs.

Afterwards, those households participating in the physical inspection are visited by a professional surveyor, who then evaluates the condition of the property. Surveyors record a range of information about each home, for example the type of house/flat, the number of rooms, date and type of construction, energy efficiency, type of boiler, etc. New surveyors attend five days of training, incorporating field work practice, to help ensure survey quality and consistency across the country. This is supported by a reference manual.

Interpreting data

House condition data is then processed by the private-sector consultants, the Building Research Establishment (BRE), using their Domestic Energy Model (BREDEM). This estimates the required energy consumption of each home, and associated costs, based on the information collected by the surveyors and information about the climate (including temperature and wind speed) in the region the dwelling is based. North or South Scotland gas or electricity prices (where applicable and where these types of fuel are being used) are applied to the modelled energy consumption in order to provide estimates of required fuel bills which are more specific to location.

Both the social survey data and the energy consumption / costs data are returned to Scottish Government statisticians who undertake further quality assurance and analysis. By combining information from the social survey about income and housing costs with the information on required energy costs, an estimate of fuel poverty can be calculated. From the sample of 3,000 households, statisticians then apply weights to ensure survey findings are representative of the household population of Scotland as a whole, correcting for areas or types of households which have been over or under sampled in the survey.

Policy background

Most Scottish Executive / Scottish Government fuel poverty and energy efficiency programmes since 2002 have focused on improving the energy efficiency of Scotland's housing stock. Hundreds of millions of pounds have been spent on retro-fitting existing homes to make them warmer, cheaper to heat and more energy efficient, for example by installing new central heating or insulating lofts, walls, doors and windows.

Previous policies

Over the past 15 years, Scotland has seen the Energy Assistance Package, the Warm Deal, the Central Heating Programme and, more recently, the Home Energy Efficiency Programmes (HEEPS). The Scottish Government also continues to fund advice services such as Home Energy Scotland (see SPICe briefing for more info on these programmes).

The Government believes these policies have made “significant progress in delivering warmer homes”1 For example, the most recent SHCS figures show that 43% of Scotland’s housing stock now conforms to the top three Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) ratings for energy efficiency, up 19 points from 2010. Over the same period the number of homes with the lowest EPC ratings has almost halved2.

Nevertheless, the Scottish Government is aware that improved energy efficiency alone is not sufficient to protect households from the effects of rising fuel costs. The previous target was set at a time when fuel prices were at a historic low; however, the years of cheap domestic energy were not to last. As the following graph shows, fuel costs rose higher and faster than the general rate of inflation between 2003 and 2016, increasing by around 150%. Over the same period, the energy efficiency of Scotland's homes improved by 38% (measured by the percentage of homes in EPC bands A to D), as did household median income.

Fuel poverty is affected by household income, the energy efficiency of homes, the price of domestic energy and the way energy is used in the home. However, the above graph shows that fuel costs have been by far the most important determinant in influencing rates of fuel poverty over recent years. Indeed, Scottish Government modelling of the reduction in fuel poverty rates between 2015 and 2016 shows that almost two thirds can be attributed to the lower price of domestic fuels, whilst around one third can be attributed to the improved energy efficiency performance of the housing stock2. According to the Scottish Government, the fuel poverty rate for 2016 would have been around 9% (instead of 26%) if fuel prices had only risen in line with inflation between 2002 and 2016.5

Energy Efficient Scotland

Improving the energy efficiency of homes and other buildings was made a National Infrastructure Priority in June 2015, with reasons set-out in the Scottish Government's 2015 Infrastructure Investment Plan:

"Investment in domestic energy efficiency helps tackle fuel poverty, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and therefore helps to meet climate change targets, and supports the economy through providing opportunities for regional SMEs to be involved in the delivery of Scottish Government programmes."

This is clearly an area where Scottish Government policies can have a major impact, and in its Energy Efficient Scotland Route Map, published in May, the Government repeated its commitment to "removing poor energy efficiency as a driver of fuel poverty". To meet this objective, the Route Map proposes a set of longer term energy performance standards for all buildings in Scotland, including specific targets for properties with fuel poor households. These include:

By 2040 all Scottish homes achieve an EPC C (where technically feasible and cost effective).

Maximise the number of social rented homes achieving EPC B by 2032, building on the existing standard, equivalent to EPC Band C or D, which social landlords must meet by 2020.

Private rented homes to EPC E by 2022, to EPC D by 2025, and to EPC C by 2030 (where technically feasible and cost effective).

All owner occupied homes to reach EPC C by 2040 (where technically feasible and cost effective).

All homes with households in fuel poverty to reach EPC C by 2030 and EPC B by 2040 (where technically feasible, cost effective and affordable).

Furthermore, in its recently published Draft Fuel Poverty Strategy, the Scottish Government committed to develop:

"...if appropriate, a wider Energy Efficient Scotland Bill for later in this Parliament, and this would be the vehicle for any further legislative changes needed to support Energy Efficient Scotland, beyond the fuel poverty provisions contained in the Fuel Poverty (Target, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Bill".1

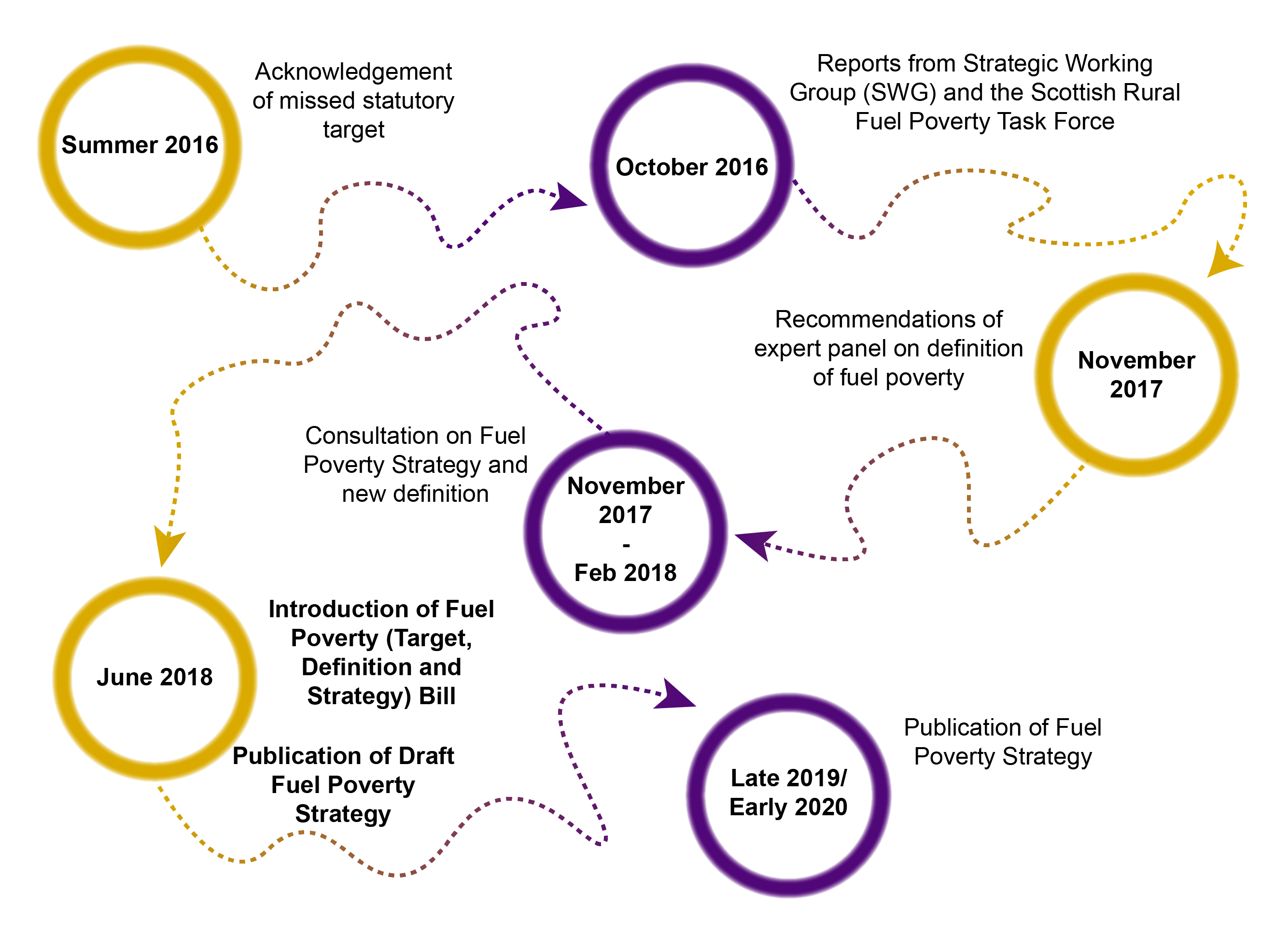

Journey to legislation

The Bill is seen as a cornerstone of the Scottish Government's new approach to tackling fuel poverty; it will be followed by the publication of a Fuel Poverty Strategy within one year of the enactment of the Bill and possibly further Energy Efficient Scotland legislation if required. It has been a long process of policy development and review leading up to the current Bill. Figure 4 shows part of this journey:

In 2015, once it was clear that the fuel poverty target was not going to be met, the Scottish Government established two short-life working groups: the Scottish Fuel Poverty Strategic Working Group (SWG) and the Scottish Rural Fuel Poverty Task Force (RFPTF). Both reported in October 2016, with over 100 recommendations between them. The SWG report included the following recommendations (most relevant to the Bill):

A review of the current fuel poverty definition is required and warranted due to concerns that the current definition is too broad and impedes targeting on those most in need.

A new definition should focus on the desired outcome - affordable and attainable warmth and energy use that supports health and wellbeing; acknowledge fuel poverty as a manifestation of poverty and inequalities in society; and be easy to understand and measure.

The Scottish Government should commission a review of the definition by a panel of independent, academic experts.

The review process should result in a new definition and target with a statutory basis.

The new fuel poverty strategy should be given a statutory basis and set out clear targets and milestones with regular requirements to measure progress towards fuel poverty eradication.

Expert panel's review of fuel poverty definition

The Scottish Government responded to the two groups’ recommendations in March 2017, immediately accepting the recommendation to establish an academic panel to examine the current definition of fuel poverty and make recommendations on how it could be improved. The independent expert Definition Review Panel published its findings and recommendations in November 20171.

The Panel made it clear that continuing with the current definition would be unsatisfactory. They felt that many of the adverse outcomes associated with fuel poverty - for example impacts on health and well-being, material hardship, debt, etc - were “at risk of being de-emphasised in the increasing policy focus on energy efficiency and building fabric”. We have seen that the current definition means fuel poverty ultimately tracks the price of domestic fuel without taking much account of efforts to help reduce the adverse effects of living in cold and damp homes. The Panel therefore concludes that “this limits the usefulness of the definition in designing effective policies to tackle the problem of fuel poverty, and in monitoring their impact”.1

Furthermore there has been some criticism that a high number of households currently considered fuel poor are not actually struggling financially. This was a concern raised by the Scottish Government's Independent Advisor on Poverty and Inequality, Naomi Eisenstadt in her Shifting the Curve report: “I have seen analysis that indicates that over half of all “fuel poor” households probably wouldn't be classified as “income poor‟ in terms of relative poverty measures”3.

Recommended definition

The Panel believes “households should be able to afford the heating and electricity needed for a decent quality of life”. Not to be able to do so implies the household is in fuel poverty. As such, their recommended definition of fuel poverty is:

when households need to spend more than 10% of their after housing cost income on heating and electricity in order to attain a healthy indoor environment that is commensurate with their vulnerability status; and

once these housing and fuel costs are deducted, households have less than 90% of Scotland’s Minimum Income Standard (MIS) from which to pay for all the other core necessities commensurate with a decent standard of living.

By using after housing costs (AHC) income in their proposed definition, instead of the before housing costs (BHC) used currently, the Panel acknowledge that housing costs are a fixed commitment with limited alternatives available. The affordability of fuel should therefore be assessed against income after housing costs - rent, mortgage, council tax and water/sewerage rates - are deducted.

It is argued that the addition of the MIS component (discussed in more detail below) helps place the proposed definition within its wider poverty and inequality context, which Naomi Eisenstadt called for back in January 2016. Also, with a greater alignment to low income, there should be more impetus for future governments to focus interventions on those households which are genuinely struggling to pay their bills.

To acknowledge the higher costs of living faced by certain households, the Panel also recommended the MIS calculation be marked-up for those experiencing disability or long term illness, and for those living in remote rural areas.

The Minimum Income Standard (MIS)

The Minimum Income Standard (MIS), calculated by Loughborough University’s Centre for Research in Social Policy (CRSP) and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF), aims to define what UK households need for a “minimum socially acceptable standard of living”. It reports annually and is based on detailed research with members of the public who discuss the goods, services and utilities needed to reach this standard. It has been used as the basis for the Living Wage calculations since 2011 (as explained in a 2015 SPICe briefing), with the first MIS report published in 2008 and the most recent published in July 2018.

For the 2018 MIS research, 22 focus groups were held across the UK (the Scottish sessions were in Dunfermline and Dundee). These discussed and decided on the contents of baskets of goods and services households require "in order to meet material needs such as food, clothing and shelter, as well as to have the opportunities and choices required to participate in society." Details of what is included in these baskets are set out on the CRSP website. Researchers then estimate the income households need in order to meet these costs. There are over 100 household types. The minimum incomes for some of these are:

| Weekly minimum income standards 2018 (excluding rent and childcare) | |

|---|---|

| Single person | £213.59 |

| Couple, 2 children aged 3 and 7 | £479.56 |

| Lone parent, 2 children aged 3 and 7 | £389.98 |

| Couple | £301.92 |

1

For the new fuel poverty definition, rent, childcare, fuel, water and council tax is deducted from MIS. The calculation then works out 90% of that value.

Recommended temperatures and vulnerable households

There are two different heating regimes recognised within the current fuel poverty definition: standard and enhanced.

Standard - an adequate standard of warmth for most households is 21°C in the living room and 18°C in other rooms for a period of 9 hours in every 24 (or 16 in 24 over the weekend).

Enhanced - households where someone is aged 60 or older or suffers from a long-term illness or disability are considered vulnerable and are assumed to require an "enhanced" heating regime. A higher temperature of 23° C in the living room and 18° C in other rooms is required for 16 hours in every 24.

The Panel was asked to examine the suitability of these temperature requirements. After some consideration, they recommended raising the threshold for bedrooms in vulnerable households to 20 ºC, otherwise all other temperature requirements should be retained.

The Panel also questioned the current use of the 60 year old-plus threshold as a way of determining vulnerability. In the absence of long-term ill health or disability, the Panel took the view "... that age should not become a proxy for vulnerability, until a much older age than is presently used as a threshold in Scotland (which is 60 years). A threshold nearer 75 to 80 years might be more appropriate."

Scottish Government's response

The Scottish Government accepted most of the Expert Panel's recommendations. For example, it decided to adopt their proposed definition, incorporating after housing cost income and the Minimum Income Standard (MIS) calculation. It also accepted that the age vulnerability threshold should rise from 60 to 75. According to Government analysis of 2015 statistics, 60% of households with any adults aged between 60 and 74 will remain classed as vulnerable to cold related health outcomes because of health issues or because they also contain another adult aged 75 or over. Overall, around 80% of households classified as vulnerable under the existing definition will remain so under the new definition.

The Scottish Government did not accept the expert panel's proposal to make MIS adjustments for remote rural households or for those experiencing disability or long term illness, the reasons are explored in the next section.

Scottish Government consultation

The Scottish Government launched a consultation on its draft Fuel Poverty Strategy including the proposed statutory target and new fuel poverty definition, running from November 2017 to February 2018. It received 91 responses, with 80 groups or organisations and 11 individual members of the public responding.

The analysis of responses1 concludes that the new definition of fuel poverty was "broadly welcomed" by most respondents, although 3 in 10 respondents noted that it is more complicated than the current definition. The fear that this could make it difficult to identify or assess fuel poor households was mentioned by around 1 in 6 responses. For example, the housing development organisation Tighean Innse Gall felt the definition may be "unwieldy and difficult to explain in everyday use" in the Western Isles2. Despite these reservations, a high number of respondents were positive about the proposed change and expected the new definition to improve targeting towards those most in need.

There were a number of concerns about the Scottish Government's rejection of the Expert Panel's recommendation that the MIS threshold be adjusted upward for households living in remote rural areas. According to the consultation summary, respondents were afraid that the proposed definition "will seriously under-represent the extent of fuel poverty in remote rural or island areas and lead to resources or investment being diverted away from the areas where fuel poverty is highest". Some high-profile stakeholders - Energy Action Scotland, WWF, COSLA and Citizens Advice Scotland3 to name but a few - felt that the high energy costs faced by off-grid households and the nature of the rural housing stock merit an upward adjustment of the MIS for rural and island households.

Responding to these concerns in the Bill's policy memorandum, the Government insists the additional living costs faced by remote and rural households are already accounted for within the modelling used to estimate fuel poverty. Thus, there is no need to adjust the MIS for the new definition. The Draft Fuel Poverty Strategy gives a further explanation of the Government's position:

"For remote rural households, the way fuel poverty is calculated already takes account of regional variations in external temperatures, solar irradiance and exposure to the wind as well as types of stock and information about occupants. These can lead to greater energy usage estimates to maintain either standard or vulnerable heating regimes in rural and remote rural areas. In addition, regionalised (North and South Scotland) energy prices are used in the fuel poverty calculation (for mains gas and electricity)."4

Likewise, for households where someone has a long-term sickness or disability, the enhanced heating regime (see above) should, the Government argue, result in higher required fuel costs, so any additional MIS adjustment is not necessary.

With regards the change in the "vulnerability" age threshold, from 60 to 75, a number of respondents, such as Glasgow City Council, NHS Scotland and Citizens Advice Scotland, highlighted the lower life expectancies of people living in certain areas of the country. The latter commented:

"We agree that those over the age of 60 should not be assumed to be vulnerable. However, we must be extremely cautious in this area. For those between the ages of 60 and 75, there is an increased likelihood of developing health problems, with Scottish Government statistics from 2009 indicating that two-thirds of individuals over 65 will have a long-term health condition."3

The Scottish Government was also interested in receiving views on its new eradication target. Within the consultation document it had originally suggested reducing fuel poverty to below 10% by 2040. However, many respondents felt this was not ambitious enough, arguing that still having 10% of households in fuel poverty is hardly consistent with the term "eradication".

Around 1 in 8 respondents, including Glasgow City and Dundee City councils, felt that the Scottish Government has little or no control over fuel costs, so any target could be unachievable, the latter stating:

"Enshrining the eradication of Fuel Poverty in law would demonstrate the Government's commitment but Dundee City Council feels that there are too many unknowns such as fuel prices rises, the effect of Brexit etc. that are out-with the Government's control; this means that the government could be setting itself up to fail."

Nevertheless, most respondents were generally positive about the new target. They believe that it makes progress measurable, gives policy-makers a clearer focus and ensures future governments are held accountable to Parliament.

Bill content

In its 2017/18 Programme for Government the Scottish Government committed to introducing a Warm Homes Bill during the 2017/18 parliamentary year. Renamed the Fuel Poverty (Target, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Bill, it was introduced on 26 June 2018. The Bill consists of 14 sections, although the first six are the most substantive. It is accompanied by explanatory notes, a policy memorandum, a statement on legislative competence, a delegated powers memorandum and a financial memorandum. The Scottish Government has also published a Children's Rights and Wellbeing Impact Assessment, an Equality Impact Assessment, a Fairer Scotland Duty Assessment and a Health Impact Assessment.

Fuel poverty target (section 1)

What the Bill says

The first section of the Bill sets out the Government's target to reduce fuel poverty to no more than 5% of Scottish households by 2040. This will be measured using Scottish House Condition Survey data (see above). The reason the target is set at 5% rather than 10%, as proposed in the consultation document, is that many stakeholders felt the 10% aspiration was not ambitious enough. The Government appears to have taken this feedback onboard.

It is worth remembering that the Government's stated ambition is to "eradicate" fuel poverty not just reduce it. The Oxford English Dictionary's definition of eradicate is to "destroy completely; put an end to". However, if 5% of households were still in fuel poverty by 2040 that would equal 138,000 households (based on National Records of Scotland projections). The Government's explanation is that a 5% target "recognises that households move in and out of fuel poverty due to changes in income and energy costs". In other words, a 0% target would be unrealistic and unachievable given the changing, temporary and often cyclical nature of household circumstances.

Although not in the Bill, the Draft Fuel Poverty Strategy released at the same time as the Bill commits to put in place "non-statutory interim targets and milestones at 2030 and 2040 to measure progress". For example, the 2030 interim targets may include the following:

The overall fuel poverty rate will be less than 15%.

Ensure the median fuel poverty gap is no more than £350.

Make progress towards removing poor energy efficiency as a driver for fuel poverty.1

There is some explanation in the Policy Memorandum as to why 2040 was chosen as the target date rather than an earlier year. After all, the original eradication target was based on a 14 year period (between 2002 and 2016) not a 20 or 21 year as is currently proposed. In explanation, the Government expects that meeting the target will require the use of "cost-effective low carbon heating" which most homes do not currently have. It would therefore be unrealistic to expect households to upgrade within a shorter time frame. According to the Scottish Government, "these targets are aligned with the delivery timeframe of Energy Efficient Scotland".2

Why is this important

The Scottish Government is proud of its ambition to eradicate/reduce fuel poverty, stating in its Policy Memorandum: "Scotland is one of only a handful of European countries to define fuel poverty, let alone set such a challenging goal to reduce it". As highlighted by the Fuel Poverty Strategic Working Group, targets provide a clear focus for policy-makers and also show stakeholders how progress is being measured.

Why is legislation required?

The Scottish Government could set a fuel poverty target without enshrining it in legislation. There are a whole range of other targets, for example an exports target in the 2011 Economic Strategy or any number of Purpose Targets from the original National Performance Framework, which did not require legislative backing.

It is clear that the extent of the problem in Scotland, and the multi-faceted nature of fuel poverty, means it could take decades to fully address the problem. As such, a statutory target will bind future governments to the eradication/reduction objective (unless, of course, they choose to repeal). Other statutory targets take a similar approach, for example the 2009 Climate Change (Scotland) Act set a target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050, and the 2017 Child Poverty (Scotland) Act set a range of targets relating to the reduction/eradication of child poverty by 2030.

There is no mention in the Bill of consequences should the target be missed. If the 2016 target is anything to go by, there will be no penalties imposed on whichever Government is in office in 2040. It is also note-worthy that the previous target, set in 2002, included the phrase "so far as reasonably practicable"; however, the proposed target does not contain any such ambiguities.

Fuel poverty definition (section 2)

What the Bill says

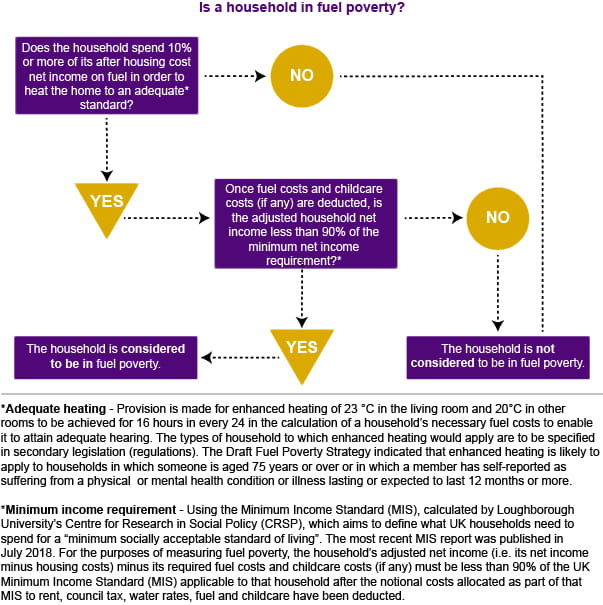

As discussed above, the Bill sets out the new definition of fuel poverty as follows:

A household is in fuel poverty if -

(a) the fuel costs necessary for the home in which members of the household live to meet the conditions set out in subsection (2) are more than 10% of the household's adjusted net income, and

(b) after deducting such fuel costs and the household's childcare costs (if any), the household's remaining adjusted net income is insufficient to maintain an acceptable standard of living for members of the household.

The following flow-chart sets out how the Government will determine whether or not a household is in fuel poverty:

Definitions of "acceptable standard of living", "childcare costs, "adjusted net income", "household" and "housing costs" are set out in Section 2 (5) and (6).

The explanatory notes provide a worked example of how calculations are made, illustrating whether or not a household is in fuel poverty (see pages 5 to 7). Two more examples are on page 41 of the Draft Fuel Poverty Strategy. These help us picture what a fuel poor household might look like under the new definition. All examples are based on the following calculations:

1. Calculate total household income including earnings of all adults (after tax and National Insurance deductions) and all benefits.

2. Subtract rent or mortgage payments, council tax and water and sewerage charges to give "adjusted net income".

3. Calculate costs associated with adequate heating requirements (see above for an explanation of "standard" and "enhanced" heating regimes).

4. Are these fuel costs more than 10% of adjusted net income? If "no", then the household is not in fuel poverty. If yes:

5. Subtract fuel costs and childcare costs (if any) from the adjusted net income.

6. Is remaining income below 90% of the minimum income standard applicable to that household type (after the notional costs allocated as part of that MIS to rent, council tax, water rates, fuel and childcare have been deducted). If "yes" then the household is in fuel poverty.

This is clearly more complex than the calculation used for the current fuel poverty definition (10% of household net income before housing costs), however most of the data required to calculate the new rate is already collected by the Scottish Government in its SHCS and larger Scottish Household Survey (and childcare data and income of other adults data will be collected from the 2018 survey onwards).

Section 2(6)(e)(i) of the Bill provides that "minimum income standard" means the MIS which is determined by the Centre for Research in Social Policy (CRSP) at Loughborough University in conjunction with the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. However, section 2(6)(e)(ii) provides that another source may determine this "as the Scottish Ministers may from time to time determine". This could become important if the CRSP were to discontinue determining MIS for whatever reason in the future, or indeed if a Scotland -specific standard was developed.

Relevant delegated powers

Defining "enhanced" and "standard" households

Section 2 (3) of the Bill specifies the temperature requirements for both the standard and enhanced regimes. What actually constitutes a household requiring "enhanced heating" is not defined in the Bill. Rather, section 2 (4) allows the Government to specify the types of household requiring enhanced heating within future regulations. Section 11(2) requires Scottish Ministers to consult "such persons as they consider appropriate" before making these regulations.

The Government feels it is appropriate to have a degree of flexibility here, for the following reasons:

The households for whom this should be the measurement will be identified in discussion with experts. This is therefore a fairly technical matter which it is considered appropriate to leave to regulations. The level of detail which may be required may mean that it would be disproportionate to include this in the Bill.

Scientific changes over time may also alter the types of households for which enhanced heating is appropriate. This may occur, for example, as part of the developing understanding of some medical conditions and research into the effect of old age. Having the ability to specify types of households by regulations provides the necessary flexibility in this regard.

Regulations will have to be introduced at the same time as Section 2 comes into force in order to define "enhanced heating" and “standard” households, since, otherwise, it will not be possible to measure fuel poverty.

Changing the meaning of "requisite temperatures", "requisite hours" and other definitions

Section 10 (a) allows Ministers to propose modifications to the meaning of "requisite temperatures" and "requisite number of hours" in future regulations should they so wish. Again, the Government seeks flexibility to "take into account any scientific findings which emerge over the long lifespan of this legislation". Section 10 (b) allows Ministers to introduce regulations to change the definition of the terms which are listed in section 2(6) (and which are used in the measurement of fuel poverty), these being “adjusted" (in respect of net income); "household"; "housing costs", "household"; "minimum income standard" and "net income". The Government provides the following reason for this:

"It is important that the meaning of these terms are enshrined in legislation so that they are interpreted consistently when assessing fuel poverty. However, it is important to have the flexibility to amend the meaning of these terms to take account of changing economic circumstances without requiring new primary legislation over the lengthy lifespan of the legislation."

And:

"...housing costs may change over the next twenty years with the introduction of different or new local and national taxes. Net income may change if a new UK-wide tax on income is introduced to fund social care. In addition, “childcare costs” is defined in order to tie in with what is assessed as a childcare cost under the UK’s minimum income standard. In order to compare like with like, it is important that these definitions are consistent, so if childcare costs under the minimum income standard began to be assessed differently, then an adjustment to section 11(6)(b) may be required. In addition, Ministers may decide to use a different source for a minimum income standard if the currently produced standard (which is not on a statutory footing to guarantee its continued production) were to suddenly be discontinued or change radically."1

Changing the definition of sufficient household income

Section 10 (c) enables the Scottish Government to change what is considered "sufficient" or "insufficient" remaining net income for a household, in other words altering what is set-out in section 2(5). The reason given for this is:

"It may become necessary to make different provision if the minimum income standard ceases to allocate, or changes the way it allocates, notional costs to the items of expenditure currently listed in section 2(5). It is also possible that different definitions may be considered appropriate in the future for different purposes (for example, the UK minimum income standard differs based on the characteristics of a household, but there may be rare cases where there is no UK minimum income standard applicable to a particular household)."1

Why is it important to have a new definition?

As stated above, many stakeholders find the current definition of fuel poverty too broad and therefore not that helpful in terms of targeting support at the poorest households. The Fuel Poverty Strategic Working Group therefore recommended a review of the definition, which a further expert panel carried out. Their proposed definition was accepted by the Scottish Government and consulted on last year.

In the Equality Impact Assessment accompanying its Bill1, the Scottish Government presents 2016 SHCS data using both the current definition and its initial analysis of the proposed definition. Comparing the results allows us to see how the overall levels and rates of fuel poverty change and the impact this is likely to have on various categories of fuel poor household.

The total number of households defined as fuel poor falls from 649,000 to 584,000, or from 26.5% of all households to 23.8%1.

The following table shows how initial analysis of the proposed definition changes the profile of those households considered fuel poor. The most striking change is the drop in the number of "older households" (one- or two-member households which include at least one resident aged 65 or older) considered fuel poor. There is also a noticeable drop in the number of fuel poor households in owner-occupied homes.

There are significant increases in the number of under 35 households and family households (containing at least one child under 16). People in social housing and the private rented sectors are also more likely to be considered fuel poor under the new definition than had previously been the case.

There is also a striking reduction in the number of rural households in fuel poverty, falling from 154,000 under the current definition to 99,000 under the new one.

| Current definition | New definition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of fuel poor households (thousands) | % of households who are fuel poor | Number of fuel poor households (thousands) | % of households who are fuel poor | |

| Total | 649 | 26.5% | 584 | 23.8% |

| Household Type | ||||

| Older households | 311 | 40.6% | 174 | 22.8% |

| Families | 66 | 12.2% | 118 | 21.6% |

| Other households | 272 | 23.8% | 292 | 25.6% |

| Age of Highest Income Householder | ||||

| Under 35 | 60 | 15.2% | 112 | 28.4% |

| 35-64 | 277 | 21.4% | 299 | 23.0% |

| 35-74 | 423 | 24.8% | 382 | 22.3% |

| Over 65 | 311 | 40.8% | 173 | 22.8% |

| Over 75 | 165 | 47.5% | 90 | 26.0% |

| Tenure | ||||

| Owned | 296 | 37.1% | 140 | 17.6% |

| Mortgaged | 78 | 11.1% | 81 | 11.4% |

| LA/public | 127 | 35.9% | 139 | 39.1% |

| HA/coop | 73 | 27.1% | 108 | 40.2% |

| Private Rented | 74 | 23.1% | 116 | 35.9% |

| Total private | 449 | 24.5% | 337 | 18.4% |

| Total social | 200 | 32.1% | 246 | 39.6% |

| Long-term sickness or disability | ||||

| Yes | 365 | 33.8% | 301 | 27.9% |

| No | 284 | 20.7% | 283 | 20.6% |

| Location | ||||

| Urban | 495 | 24.3% | 484 | 23.8% |

| Rural | 154 | 37.3% | 99 | 24.0% |

One of the main reasons given for changing the definition is to focus in on low income households. Therefore, it is worth looking at the Scottish Government's analysis in detail. The following table shows the number of households in fuel poverty by weekly household income band, plus the percentage of households in fuel poverty within each band. The Government's analysis compares the number and rates under the current definition and those under the proposed definition:

| Current definition | New definition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household Income (weekly) | Number of fuel poor households (thousands) | % of households who are fuel poor | Number of fuel poor households (thousands) | % of households who are fuel poor |

| <£200 | 263 | 86.9% | 277 | 89.6% |

| £200-£300 | 229 | 49.3% | 204 | 44.2% |

| £300-£400 | 94 | 24.0% | 76 | 19.5% |

| £400-£500 | 27 | 10.1% | 12 | 4.6% |

| £500-£700 | 28 | 6.4% | 10 | 2.3% |

| £700+ | 7 | 1.3% | 4 | 0.7% |

1

There is an increase of 14,000 in the number of households from the lowest income band moving into the definition of fuel poor, which certainly aligns with the aspirations of the Bill. However, there are also 25,000 fewer households in the £200-£300 income band being categorised as fuel poor. A similar trend is identifiable in the Scottish Government analysis of 2015 SHCS data. The Fairer Scotland Duty assessment which accompanies the Bill states that the new definition "ensures that households only marginally above the income poverty line that are struggling with their fuel bills, will be captured in the new definition". Given this aspiration, it is perhaps surprising that fewer households in the £200-£300 weekly income band will be considered fuel poor under the new definition than under the current one.

In a personal correspondence with the author, Scottish Government statisticians were keen to stress that:

"the household income data presented here is not equivalised and therefore the £200-£300 band can include a range of different household types, from single adult to couple households with children. For example, the 60% median income threshold (before housing costs, for comparison with this net income before housing costs) in 2015/16 was £288 per week for a couple with no children or £193 per week for a single adult with no children. It is therefore clear that, under the current definition, the £200-£300 band can include households which are not considered to be in income poverty. The Government has included, in its draft Fuel Poverty strategy, diagrams demonstrating the stronger alignment with income poverty which the proposed new definition offers".

Why is legislation required?

In the Bill's Policy Memorandum the Scottish Government states that "any alternatives to reviewing the definition and introducing a new target through a Bill would not be acceptable to the wider stakeholder community" (p.9). By legislating on the definition and target, the Government is "making a clear statement about their commitment to eradicating fuel poverty and the direction of travel to be taken" (p.9). Having the definition set out in legislation means that it will be difficult for future governments to change it without introducing their own legislation. This should ensure some consistency of measurement for the lifetime of the target (although, as discussed above, regulation-making powers in the Bill also inject a degree of flexibility).

Fuel poverty strategy (sections 3 to 5)

What the Bill says

The Bill requires the Scottish Government to publish a fuel poverty strategy within a year of Section 3 of the Bill coming into force. The Bill does not say when this will be, however, as it simply enables Ministers to bring Section 3 into force through regulations. It does not mean within a year of the Bill receiving Royal Assent.

Before the strategy is published, the Government must consult "such persons as they consider appropriate", including people who are experiencing, or have experienced, fuel poverty. A similar requirement to consult and publish was included in the 2001 Housing Act (see Section 88).

According to the Explanatory Notes, the strategy must include the following:

the approach that Ministers intend to take to ensure that the 2040 target is met;

the types of organisations with which Ministers intend to work (for example, local authorities or third sector bodies);

characteristics of households for which fuel poverty is a particular problem (for example, there are particular issues which arise for rural Scotland and the islands);

how Ministers intend to assess whether the 2040 target is met and what the rates of fuel poverty are (and, as the policy memorandum notes, the intention is to use the Scottish House Condition Survey in order to measure fuel poverty).

As mentioned above, a Draft Fuel Poverty Strategy was published at the same time as the Bill. Although there has already been a consultation on the draft strategy, the Minister for Local Government and Housing confirmed that the actions outlined in the Draft Strategy will themselves be consulted on. The final strategy document is due for publication from late 2019 onwards, as subject to Section 3 of the Bill coming into force.

In personal correspondence with the author, the Scottish Government felt it necessary to note "that any consultation which was carried out prior to the Bill coming into force is not invalidated simply by reason of when it was carried out. It is expected that this may include any consultation that occurs at the same time as the Bill is going through Parliament or shortly after the Bill is passed, but before it comes into force."1

Why is legislation required?

Again, the Government can introduce a fuel poverty strategy whenever it wants, and without any need to impose one through legislation. This has been the case for the vast majority of Scottish Government strategies, which often follow a review-draft-consult-publish process, but rarely require legislation to specify when they are to be published and what should be included in them. According to the Scottish Government "the Scottish Fuel Poverty Strategic Working Group (SWG) recommended a strategy was introduced and given statutory standing".1

Reporting on fuel poverty (sections 6 to 9)

The Bill requires the Scottish Government to report to Parliament every five years - beginning with the day on which the fuel poverty strategy is published. The report should include the following:

the steps that have been taken towards meeting the 2040 target over the previous five years;

the progress made towards the 2040 target, and;

the steps that Scottish Ministers propose to take over the next five years in order to meet the 2040 target.

Other relevant information may also be included in the strategy, for example, information about how it interacts with other related strategies or statutory requirements, such as climate change targets.

Assuming that the fuel poverty strategy is published in December 2019, the first update report should appear on the same day in December 2024.

Although this is not stipulated in the Bill, the final report will appear no later than 31 March 2042, as the SHCS for 2040 will be published around then (most probably December 2041). The SCHS will continue to be published yearly and will continue to provide annual estimates of fuel poverty levels and rates by demographic group, housing type, local authority area, etc.

Financial memorandum

According to the Financial Memorandum (FM), the Bill "does not, on its own, impose any new or significant additional costs on the Scottish Administration". The Focus of the FM is on the staff costs required to publish the strategy. This is estimated to be £125,000, which will be incurred during financial year 2018-19. In addition, between 2020 and 2040 it is expected four update reports will be published. It is expected each report will incur staff costs of £92,500. These recurring costs are unlikely to be more than what is currently spent on fuel poverty statements as required by the 2001 Act.

The FM does not estimate the cost of eradicating fuel poverty, as "key policies and proposals will need to be set out in each update on the strategy over the period to 2040". According to the Scottish Government, an indicative overall cost for meeting the targets will be similar to the costs of delivering current programmes, i.e. in the region of £110 million per year.

The current Economy, Jobs and Fair Work Committee, and the previous Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee , both asked the Scottish Government to provide estimates of the costs required to eradicate fuel poverty; however, no figure has ever been provided. For example, the Economy Committee included the following recommendation in its report on the Draft Budget 2017-18:

“Energy Action Scotland said the past 15 years show that the levels of spending on ending fuel poverty have not been enough. They reminded the Committee that the scale of the problem has never been fully assessed. A robust and up-to-date cost analysis was recommended by the Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee in 2014 and again in 2015. We repeat that call here.”1

It is interesting to note that the recently introduced Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill is accompanied by a Financial Memorandum (page 6) which provides both a direct administration cost to the Scottish Government (very small) and an estimate of the cost to the economy as a whole (very large). It is unclear why the Government produced an estimate for the Climate Change Bill but were unable to do something similar for the Fuel Poverty (Targets, Definition and Strategy) Bill.