Economic, social and cultural rights - some frequently asked questions

This briefing provides responses to some frequently asked questions on economic, social and cultural rights. Thanks should be given to other SPICe researchers and Dr Kirsteen Shields (academic fellow at SPICe in 2016) for their input on this issue.

What are economic, social and cultural rights?

Economic, social and cultural rights (ESC rights) are human rights 1 which have a focus on the economic, social and cultural needs of individuals. They are part of the political debate about the appropriate role of the state in addressing issues such as poverty, homelessness, unemployment, poor working conditions, inequality etc.

The UN's chief human rights body, the "Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights", identifies ESC rights as:

those human rights relating to the workplace, social security, family life, participation in cultural life, and access to housing, food, water, health care and education

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2008, December). Frequently Asked Questions on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Fact Sheet No. 33. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FactSheet33en.pdf

The Council of Europe,i an intergovernmental organisation established after World War II, explains that ESC rights are concerned with:

how people live and work together and the basic necessities of life. They are based on the ideas of equality and guaranteed access to essential social and economic goods, services, and opportunities.

Council of Europe. (n.d.) The Evolution of Human Rights. Retrieved from https://www.coe.int/en/web/compass/the-evolution-of-human-rights [accessed 19 October 2017]

Although it notes that ESC rights, "may be expressed differently from country to country or from one instrument to another", the UN's Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights states that the core rights, based on the rights in the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), include:

Workers’ rights, including freedom from forced labour, the rights to decide freely to accept or choose work, to fair wages and equal pay for equal work, to reasonable limitation of working hours, to safe and healthy working conditions, to join and form trade unions, and to strike

The right to social security and social protection, including the right not to be denied social security coverage arbitrarily or unreasonably, and the right to adequate protection in the event of unemployment, sickness, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond one's control

Protection of and assistance to the family, including the rights to marriage by free consent, to maternity and paternity protection, and to protection of children from economic and social exploitation

The right to an adequate standard of living, including the rights to food and freedom from hunger, to adequate housing, to water and to clothing

The right to health, including the right to access health facilities, to healthy occupational and environmental conditions, and protection against epidemic diseases, and rights relevant to sexual and reproductive health

The right to education, including the right to free and compulsory primary education and to available and accessible secondary and higher education, progressively made free of charge; and the liberty of parents to choose schools for their children

Cultural rights, including the right to participate in cultural life and to share in and benefit from scientific advancement4

ESC rights are often contrasted with civil and political rights such as the right to life, freedom of expression etc. on the basis that:

Many civil and political rights represent freedoms from something negative (e.g. torture, censorship, abuse of state power) whereas ESC rights tend to be freedoms to enjoy something positive (e.g. adequate housing, fair work etc.)

The implementation of ESC rights can involve larger resource implications for states than the implementation of civil and political rights

In many countries (including the UK), it is more difficult for individuals to bring court actions based on ESC rights than where civil and political rights are involved

However, others, including the major international human rights bodies, take the view that ESC rights and civil and political rights are not fundamentally different and are part of a larger, interconnected package. For example, the UN's Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights states that:

All human rights are indivisible, whether they are civil and political rights, such as the right to life, equality before the law and freedom of expression; economic, social and cultural rights, such as the rights to work, social security and education , or collective rights, such as the rights to development and self-determination, are indivisible, interrelated and interdependent. The improvement of one right facilitates advancement of the others. Likewise, the deprivation of one right adversely affects the others

United Nations - Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2018). What are human rights?. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Pages/WhatareHumanRights.aspx [accessed 4 May 2018]

How do ESC rights differ from civil and political rights?

ESC rights are often contrasted with civil and political rights such as the right to life, the right to a fair trial, freedom of expression, protection against torture etc.

This is partly a result of history. Civil and political rights have their origins in western liberal democratic traditions and have been included in constitutions from the late eighteenth century (e.g. the US Constitution of 1791).

In contrast, the main impetus for ESC rights arguably emerged later, from the industrial revolution onwards when states increasingly took on a role in the organisation of economic and social matters.i2 As a result, civil and political rights are sometimes referred to as "first generation rights" and ESC rights as "second generation rights."3

To a degree, these historical differences are reflected in the scope of the rights. ESC rights often have a stronger focus on equality and the economic and social needs of individuals, whereas civil and political rights stress more the "freedom" of individuals and the protection of democratic processes. In addition, a number of civil and political rights require the state/others to refrain from acting in a certain way, whereas many ESC rights require states to determine how financial resources should be used.

There are also differences in states' legal obligations at an international level, in particular the reference to "progressive realisation" clauses in international treaties protecting ESC rights, which is not mirrored in civil and political rights treaties.

For example, Article 2(1) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights - the key UN treaty protecting ESC rights - states that:

Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to take steps, individually and through international assistance and cooperation, especially economic and technical, to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the present Covenant by all appropriate means, including particularly the adoption of legislative measures.

The obligation to achieve a certain goal is therefore an incremental one, which can be achieved over a period of time, taking into account the availability of resources. Consequently, countries with greater economic resources (for example developed countries) may have greater duties to realise ESC rights than less well-off countries.4

Differences also exist at the level of national law, as in many countries it is more difficult for individuals to bring court actions based on ESC rights than where civil and political rights are involved.

For example, in the UK, the Human Rights Act 1998 does not incorporate the UN's human rights treaties into national law, which means that UN-based ESC and civil and political rights are not enforceable in court. Consequently, individuals bringing actions based on ESC rights in UK courts can only rely on:

the limited ESC rights provisions in the European Convention on Human Rights (brought into UK law by the Human Rights Act): or

ESC rights in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (but only when EU law is involved)

As a result of these differences, some argue that ESC rights have a weaker, more aspirational status than civil and political rights.5

However, others, including the major international human rights bodies, stress that ESC rights and civil and political rights are both based on binding international obligations and are not fundamentally different in scope.

For example, the UN's Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, adopted by consensus by all UN states at the World Conference on Human Rights on 25 June 1993, indicates that, "all human rights are universal, indivisible and interdependent and interrelated" and that, "the international community must treat human rights globally in a fair and equal manner, on the same footing, and with the same emphasis."

Similarly, the UN's Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights argues that creating separate categories for ESC rights and civil and political rights is, "artificial and even self defeating" and that, "in reality, the enjoyment of all human rights is interlinked."6

For example, it explains that it is often harder for individuals who cannot read and write (i.e. who have not been given a right to education) to find work, to take part in political activity or to exercise their civil and political rights such as the right to freedom of expression or the right to vote. Similarly, arguments can also be made that civil and political rights such as the right to life cannot be fully enjoyed unless there is also adequate protection of the right to health, or the right to adequate and safe housing.

The UN's Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights also emphasises that many ESC rights are not subject to "progressive realisation" because their obligations kick in immediately (e.g. the elimination of discrimination), or because they do not require significant state resources (e.g. the right to form trade unions). Similar points are also included in General Comment No. 3 of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rightsii which emphasises that, while the full realisation of the relevant rights may be achieved progressively:

there are minimum core standards for each ESC right

steps to achieve compliance have to be taken within a reasonably short time after the obligations have come into force

states should move as expeditiously and effectively as possible towards full realisation of the rights and should avoid retrogressive measures7

The UN's Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights also stresses that the distinction between ESC rights and civil political rights was largely a result of cold war politics, noting that:

The market economies of the West tended to put greater emphasis on civil and political rights, while the centrally planned economies of the Eastern bloc highlighted the importance of economic, social and cultural rights. This led to the negotiation and adoption of two separate Covenants—one on civil and political rights, and another on economic, social and cultural rights. ... However, this strict separation has since been abandoned and there has been a return to the original architecture of the Universal Declaration.

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2008, December). Frequently Asked Questions on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Fact Sheet No. 33. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FactSheet33en.pdf

The argument that ESC rights and civil and political rights are interlinked was also stressed by the House of Lords and House of Commons Joint Committee on Human Rights in a report published in 2004. It noted that:

No clear line of demarcation can be drawn between the substance of rights classified as civil and political, and those classified as economic, social and cultural ... For example, the right to an adequate standard of living (Article 11 ICESCR) is a more robust expression of the minimum protection available under the freedom from inhuman and degrading treatment (Article 3 European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)), which will guard against the worst forms of destitution.

House of Lords and House of Commons - Joint Committee On Human Rights. (2004, October 20). Joint Committee On Human Rights - Twenty-First Report (para 21). Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/jt200304/jtselect/jtrights/183/18302.htm [accessed 15 March 2018]

What are the main sources of ESC rights at an international level?

The development of human rights at an international level is largely a political process in which countries reach a consensus on the rights they consider worthy of protection, before translating these into legal obligations.

The UN, which was established immediately after World War II, has a key role in this process, and is one of the main sources of ESC rights.

One of its first pieces of work was the drawing up of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

The UDHR is widely regarded as the cornerstone of the modern human rights movement. Although not a legally binding instrument, it provides the overarching framework and political commitment for the development of more detailed, and legally-binding, human rights treaties. Instruments such as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights give international legal effect to the principles and objectives adopted by the UN via the UDHR.

The UDHR was also one of the first documents to recognise that a state's treatment of its own citizens is a legitimate concern for the international community as a whole (rather than being merely a domestic issue).1

The UDHR provides the framework for the development of two key legally binding UN treaties:

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); and

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

Both of these treaties were adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 16 December 1966 and came into force on 3 January 1976.

ICESCR contains an extensive range of ESC rights, including rights to:

work, fair wages and safe and healthy working conditions;

form trade unions;

social security;

an adequate standard of living; and

education.

ICESCR is complemented by other UN treaties which address specific concerns and protect the rights of particular groups within wider society. These include:

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination – this entered into force on 4 January 1969 and requires states to guarantee ESC rights without distinction as to race, colour, or national or ethnic origin

The Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) - this entered into force on 3 September 1981 and, amongst other things, covers economic social and cultural discrimination against women

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) – this entered into force on 2 September 1990 and sets out the civil, political and ESC rights that children should be entitled to

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) - this entered into force on 3 May 2008 and sets out the human rights of persons with disabilities

The UK is bound in international law to perform its treaty obligations under these treaties in good faith.i

There are also a number of optional protocols to the treaties above which enable complaints (known as “communications procedures”) to be taken to the relevant UN committee.

The UK has not signed up to the optional protocols for ICESCR (OP-ICESCR) or for UNCRC ( OP-UNCRC), but has done so for the CEDAW and CRPD.

There are also a number of non-binding UN instruments which provide further guidance on ESC rights. Examples include:

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) (2011)– these stipulate that businesses should respect ESC rights in the ICESCR, and that states should take appropriate measures to ensure such protection.

The Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Forests and Fisheries in the context of National Food Security (2012)– these affirm the importance that secure land tenure plays in enabling the realisation of other human rights, particularly ESC rights.

Various regional treaties also exist which are aimed at protecting ESC rights, for example, within Africa, the Americas and Europe.2

How are ESC rights protected and enforced by the UN?

There are two types of UN bodies which have a role in enforcing ESC rights:

Treaty-based bodies - these have a relatively narrow mandate derived from specific UN treaties and take decisions based on consensus .1

Charter-based bodies - these derive their authority from the provisions contained in the Charter of the United Nations, have a broader mandate and take decisions based on majority voting.2

Treaty-based bodies

The UN treaties which protect ESC rights, such as the ICESCR, are binding at the level of international law (i.e between states).

The treaties do not provide a court-based system of enforcement if states breach their obligations. Instead, they set up a range of less formal mechanisms designed to improve human rights protection.

Expert committees - concluding observations

Arguably, the most important mechanism is the system of independent expert committees which monitor the implementation of human rights treaty obligations at a national level.

Various committees deal with ESC rights, including the Committee on the Rights of the Child, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination and the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women.

However, the key committee is the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights which has the mandate to monitor states' fulfilment of their obligations under the ICESCR. It was set up in 1985, taking over the role of the UN's Economic and Social Council. It is made up of 18 independent human rights experts who are elected for a four year period.

Approximately every five years, states have to submit reports to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights outlining their progress in implementing the rights in the ICESCR.3

The UK report is submitted by the UK Government as it is responsible for implementation of ICESCR. The report does, however, take into account the situation in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland following input from the devolved nations.

The Committee examines each national report and considers it in conjunction with other evidence submitted by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and national human rights institutions (known as "parallel reports" or more often "shadow reports").4

The Committee then draws up lists of issues (LOIs) which it considers need addressing at national level.

States are given the opportunity to respond in writing to these LOIs and an interactive dialogue takes place between the state party and the Committee, with national human rights institutions and NGOs able to submit further evidence to the Committee in the margins or through meetings at around the same time.

The Committee then addresses its formal recommendations to the state in what are known as “concluding observations”. States are able to respond in writing and are required to take measures to implement the recommendations before the cycle begins again.

It is important to note that concluding observations are not legally binding - there is no legal sanction for non-compliance.5 Instead they are designed to encourage change by highlighting problems and putting political pressure on the state in question - both at an international level and domestically. In this regard, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights states in a factsheet that:

While the Committee's concluding observations, in particular suggestions and recommendations, may not carry legally binding status, they are indicative of the opinion of the only expert body entrusted with and capable of making such pronouncements. Consequently, for States parties to ignore or not act on such views would be to show bad faith in implementing their Covenant-based obligations. In a number of instances, changes in policy, practice and law have been registered at least partly in response to the Committee's concluding observations.

United Nations - Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. (1996, May). http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FactSheet16rev.1en.pdf. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FactSheet16rev.1en.pdf [accessed 4 January 2018]

The Committee's most recent concluding observations in relation to the UK were published in July 2016.7 This followed the submission of the UK Government's report to the Committee in June 2014.8 The Scottish Government also published its own position statements around the time of the submission of the UK report. SPICe understands that due to pressure of circumstances at the time, the Scottish Government's response to the ICESCR concluding observations was included in its response to the UN Universal Periodic Review recommendations in December 2017. 9

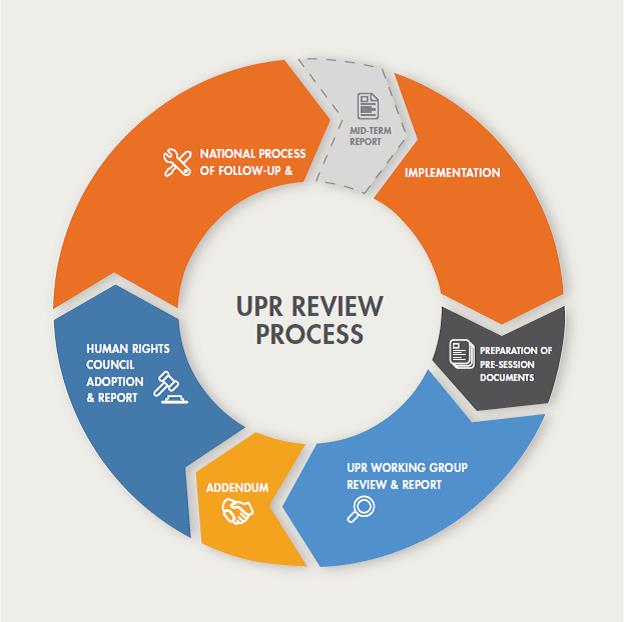

The diagram below outlines how the UN's treaty reporting cycle works.

Expert committees - general comments, complaints and inquiries

In line with other UN Committees, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights also publishes its interpretation of the provisions in the Covenant in what are known as "general comments" or "general recommendations." General comments are not legally binding, but instead clarify and expand on treaty provisions, often dealing with thematic issues and states' reporting duties.1011

The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights also uses a number of other methods to tackle violations of ESC rights. For example, where a state has signed up to the Optional Protocol to the ICESCR, it can under certain circumstances:

Investigate complaints about alleged violations of ESC rights from individuals

Investigate complaints about alleged violations of ESC rights from other State parties

Initiate inquiries about alleged violations of ESC rights on its own initiative12

The UK has not ratified the Optional Protocol and the Committee cannot use these rules to investigate alleged violations of ESC rights in the UK. 13

As explained above, the UK has, however, signed up to the optional protocols for the CEDAW and CRPD.

In the case of the CRPD, this allowed the UN committee to carry out an inquiry in 2016 into the impact of UK welfare reforms on the rights of disabled people. In October 2016, the UN committee reported that the reforms had led to ‘grave and systematic’ violations of the rights of disabled people, emphasising changes to Housing Benefit entitlement, eligibility criteria for Personal Independence Payment (PIP) and social care, and the ending of the Independent Living Fund.

The UK Government published a response at the time the publication of the Committee's report, stating that it “strongly disagrees” with the report's findings. As the CRPD does not contain formal mechanisms that allow the Committee to enforce its recommendations, the UK Government's response brought this process to an end.14

Charter-based bodies - the Universal Periodic Review

The UN's charter-based human rights body is the Human Rights Council.

It was established in March 2006 and is made up of 47 Member States, which are elected by the majority of members of the General Assembly of the United Nations.

The role of the Human Rights Council is to strengthen the promotion and protection of human rights around the globe (including ESC rights) and to address human rights violations.

Much of its work is carried out through various subsidiary bodies, including the Advisory Committee (a research body made up of 18 experts which reports to the Council) and the Universal Periodic Review Working Group which is responsible for the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) - one of the Council's main roles.

The UPR is a peer review process in which the human rights records of all 193 UN Member States are reviewed on a periodic basis by the other Member States. It can be contrasted with the examinations conducted by treaty bodies, which are composed of expert members.

The United Nations notes that:

the UPR is designed to prompt, support, and expand the promotion and protection of human rights on the ground. To achieve this, the UPR involves assessing States’ human rights records and addressing human rights violations wherever they occur. The UPR also aims to provide technical assistance to States and enhance their capacity to deal effectively with human rights challenges and to share best practices in the field of human rights among States and other stakeholders.

United Nations - Human Rights - Office of the High Commissioner. (2018). Basic facts about the UPR. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/UPR/Pages/BasicFacts.aspx [accessed 19 January 2018]

The reviews take place in a series of fixed cycles, stretching across a number of years. The first cycle was from 2008-2012 and the second cycle from 2012-2016. The third cycle is from 2017-2021.16

Documents on which the reviews are based are:

Information provided by the State under review, normally in the form of a “national report”

Information in the reports of independent human rights experts and groups, known as the Special Procedures, human rights treaty bodies, and other UN entities

Information from other stakeholders including national human rights institutions and non-governmental organizations.

Reviews involve a so-called "interactive dialogue" between the state under review and other UN Member States during a meeting of the UPR Working Group. This is facilitated by groups of three states, or "troikas" drawn by lots who act as rapporteurs. During this process any UN Member State can pose questions, comments and/or make recommendations to the states under review.

Following the review by the Working Group, a report known as the “outcome report" is prepared by the troika. This contains recommendations to the state under review as well as the responses by the reviewed state. The report is then adopted at a plenary session of the Human Rights Council, with time being allotted to states, NGOs and other stakeholders to make general comments. In broad terms. states under review are able to indicate which recommendations enjoy the state's support and which ones are merely "noted" (i.e. the state has either taken some steps, but is not fully implementing the recommendation or does not intend to take any further action).

The diagram below explains in simple terms how the UPR process works.

The UPR is designed as a transparent process, involving civil society, which allows good practice to be shared and issues of concern to be highlighted.

Working group recommendations are, however, not binding in a legal sense. Instead, the process envisages that states implement recommendations in the period between reviews (known as the "follow up") with states involved in the following review cycle having responsibility for monitoring implementation.i

The Human Rights Council can take measures to address "persistent non-cooperation" with the UPR. However, this is a little used option which is designed to deal with the most serious forms of non-compliance (e.g. complete failure to participate in the UPR process).

The follow-up is arguably the most important phase of the UPR as, without proper implementation and monitoring, there is a risk that the process remains limited to dialogue.

The United Nations recently examined the issue of follow-up in research from 2014 entitled, "Beyond Promises: The impact of the UPR on the ground". This indicated that the data on state implementation of UPR recommendations were encouraging, but also concluded that:

At the same time, while the UPR has thus far proven to be a cooperative mechanism, its Achilles heel lies in the will of the states to participate in the mechanism and to implement the recommendations ... When states under review do not implement recommendations, Recommending states can reiterate those recommendations in the following reviews, but how many cycles must pass before real action is taken to ensure that the state is promoting and protecting the human rights of its own citizens?

United Nations. (2014). Beyond promises: The impact of the UPR on the ground. Retrieved from https://www.upr-info.org/sites/default/files/general-document/pdf/2014_beyond_promises.pdf [accessed 23 February 2018]

Universal Periodic Review - UK and Scotland

The UK Government submitted its most recent national report to the UN in February 2017 ahead of meetings of the UPR Working Group in May 2017. The UPR Working Group published its report on 14 July 2017. It included certain references to ESC rights and recommended that the UK ratify the Optional Protocol to the ICESCR mentioned above. The UK responded to the working group's recommendations in a separate report published on 21 September 2017.18

As the UK is the signatory state, its reports also cover devolved matters.ii The devolved administrations are closely involved with that process and the Scottish Government contributes to the overall UK report. The reporting process is coordinated by the Ministry of Justice. In order to ensure devolved Scottish interests are presented as a matter of public record, the Scottish Government will normally also publish its own position statements which describe in more detail Scotland's performance against international human rights obligations.19 These devolved reports do not, however, form part of formal UN procedures and are not published on the UN website.

On 8 December 2017, the Scottish Government also published a separate response to the UN's UPR recommendations. This includes detailed commentary on the status of ESC rights in Scotland (for example in areas such as housing and social security).

More details on Scotland's role in the UPR process can be found in the Official Report of the Scottish Parliament's Equalities and Human Rights Committee's evidence session on UPR which was held on 18 January 2018.

What are the main sources of ESC rights at a European level?

ESC rights are also protected at a European level, in particular through the work of the Council of Europe – a non-EU organisation established after World War II focused on human rights, democracy and the rule of law.

Part of the Council of Europe's work involves the formation of international treaties which are then signed and ratified by its member states.1 The main ones which deal with ESC rights are:

The European Social Charter – this is the main treaty on social rights in Europe. It includes a range of ESC rights related to employment, housing, health, education, social protection and welfare. The European Social Charter was revised in 1996 to extend and add to some of these rights. The UK has signed the Revised Social Charter, but has yet to ratify it.2 As a result, only the original Social Charter applies in the UK.

All 47 Council of Europe states have signed up to the Convention. Its principal focus is on core civil and political rights, such as freedom of speech, the right to a fair trial and freedom from torture. It nonetheless has relevance for ESC rights. In particular:

Some civil and political rights are closely linked to the practical enjoyment of ESC rights. For example, the right to respect for private and family life includes protections for an individual's home and the right to freedom of assembly and association includes trade union rights

Subsequent protocols to the Convention have added certain ESC rights, in particular the right to the peaceful enjoyment of property and the right not to be denied an education (the latter is, however, not expressed as a positive right to access education and is not directly comparable with educational rights in treaties such as ICESCR).

Various civil and political rights, such as the prohibition of discrimination (Article 14) or the right to a fair trial (Article 6), can play a role in ESC cases. For details of the scope of Article 6 in civil cases see the Guidance from the European Court of Human Rights

It is worth noting that the distinction between civil and political rights and ESC rights in the Convention is not always clear cut.

For example, Article 1 of the First Protocol (the right to the peaceful enjoyment of property) prohibits states from arbitrarily taking away private property, thus acting like many civil and political rights which stop states from acting in a certain way.3 However, the definition of "property" can extend to entitlements such as social security payments, thereby providing some safeguards in relation to ESC rights.4 5

The right to the peaceful enjoyment of property can also play a key role in housing policy such as the legality of rent controls.i Similarly, although it does not provide a general duty to house the homeless, the prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment (Article 3), can be can be used to challenge decisions of local authorities/the UK Government in homelessness cases where destitution and specific personal factors are involved. 67

ESC rights are also protected at EU level, for example through discrete pieces of legislation such as rules on workers' rights.

However, the main source of protection is the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (2000) (the EU Charter) which applies to all acts of the EU institutions, and to Member States when they implement, derogate from or act within the scope of EU law (see Dr Kirsteen Shields' SPICe Briefing on Human Rights in Scotland).

The EU Charter entered into force with the Treaty of Lisbon in December 2009, which amended the Treaty on the European Union (TEU)ii to give the rights in the Charter the same legal status as the EU Treaties.

The rights set out in the Charter stem from existing general principles of EU law but also common constitutional traditions, the Convention and UN treaties. A broad range of civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights are included. Rights are grouped under six titles: Dignity, Freedoms, Equality, Solidarity, Citizens' Rights, and Justice.

The inclusion of social rights in the EU Charter was a controversial issue from the outset among certain Member States (particularly the UK, Denmark and the Netherlands). The political compromise which was reached was to split the provisions in the Charter into:

legally enforceable rights; and

non-binding principles which may only be invoked for the interpretation of areas in which the EU or the Member State has legislated.

The Charter itself does not clearly distinguish between rights and principles. However, most non-binding principles are contained in the Solidarity chapter which is focused on ESC rights.8

The Council of Europe and EU are separate bodies and have separate human rights systems. There are, however, elements of overlap. For example, Article 6(3) TEU provides that fundamental rights under the Convention are considered to be part of the general principles of EU law. In addition, in practice both courts largely pay attention to each other's jurisprudence with the aim of avoiding conflict.9 Also, although this has yet to occur due to the Court of Justice blocking the process,10 Article 6(3) of the TEU provides that the EU shall accede to the Convention.

How are ESC rights protected and enforced by the Council of Europe?

Parliamentary Assembly

The Council of Europe has its own parliamentary arm, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), which consists of 324 members of parliament from the 47 member states of the Council of Europe. It meets four times a year for week-long plenary sessions in Strasbourg.

Though it has no power to pass binding legislation, PACE has a role in relation to the protection of human rights by the Council. It elects the Secretary General of the Council of Europe, the Human Rights Commissioner and the judges to the European Court of Human Rights, provides a democratic forum for debate and monitors elections. Its committees examine current issues and produce reports which are then debated in plenary session allowing the Parliamentary Assembly to make recommendations.

The key committees in the field of human rights are the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights and the Committee on Equality and Non-discrimination.

Commissioner for Human Rights

The Council of Europe's Commissioner for Human Rights, currently Dunja Mijatović who took up the post on 3 April 2018, has a mandate to promote the observance of human rights (including ESC rights) in Council of Europe States.

This role includes the monitoring and raising awareness of human rights at a national level and identifying possible shortcomings in law and practice. When requested, states are also required to report on their compliance with the Convention to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe (Article 52 of the Convention).

European Court of Human Rights

Unlike most international human rights bodies, the Council of Europe also has a dedicated court, the European Court of Human Rights (Court of Human Rights) based in Strasbourg, which hears cases brought by both states and individuals (articles 33 and 34 of the Convention).

The rights of individuals to bring cases to the Court of Human Rights is not designed to replace national procedures, but instead acts as a safety net for situations where problems cannot be solved at a national level. Individuals, therefore, have to exhaust their domestic remedies (e.g. proceedings in national courts) before they can bring a case to the Court of Human Rights (Article 35 of the Convention).

Although the majority of UK complaints submitted to the Court of Human Rights are deemed inadmissible (over 99% of complaints in 2017),1 over the years the court has nonetheless taken numerous decisions of significance to UK law and policy.

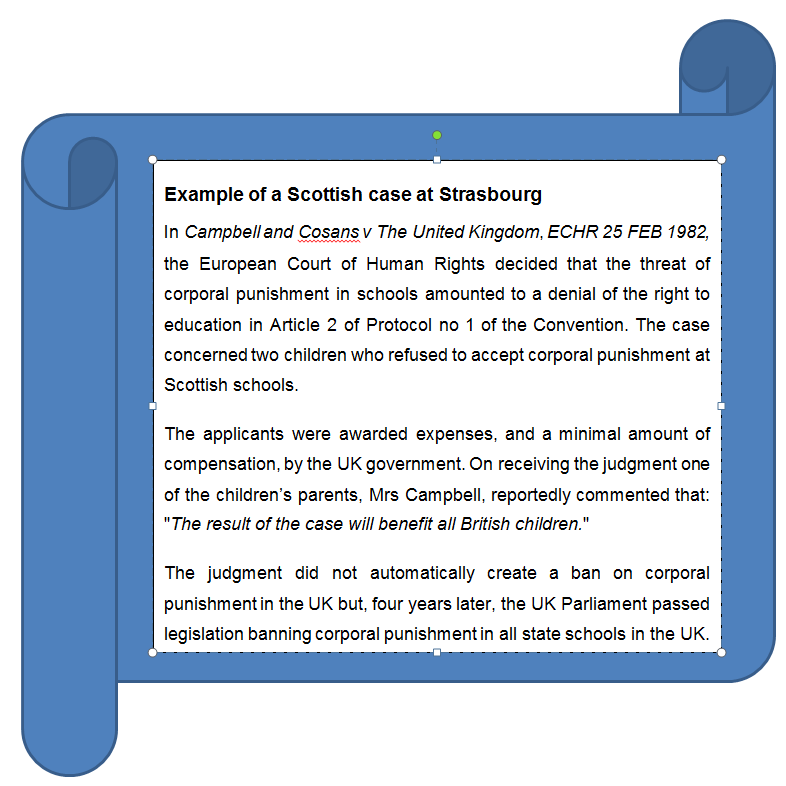

While the Convention's main focus is on civil and political rights, some of the court's judgments are linked to ESC rights.2 For a Scottish example from the 1980s which led to the abolition of corporal punishment in UK schools see below.

Article 46 of the Convention requires states to abide by final judgments of the Court of Human Rights in cases to which they are a party. Although judgments are only formally binding on the states involved in a particular case, there are increasing arguments that states should be required to take account of Court of Human Rights judgments involving other states.3 45Whether states do this is, however, currently largely a matter of national law.

The enforcement of Court of Human Rights judgements is largely a political process involving dialogue between the state in question and the Council of Europe. This process falls under the ambit of the Council of Europe's Committee of Ministers, i.e. states' Ministers for Foreign Affairs or their representatives. Therefore, political factors can, and do, play a role in the Committee of Ministers' decisions and there can be long delays in enforcement if a Member State refuses to follow a judgment of the court. A recent example is the UK prisoner voting cases which were not resolved in the Committee of Ministers until December 2017, some 12 years after the first judgment of the Court of Human Rights.6

How are ESC rights protected and enforced by the EU?

EU Charter

As the EU Charter has the same legal status as the EU treaties, the EU institutions are required to take it into account when designing and implementing policy and legislation.1

Similarly, Member States are required to comply with the EU Charter, but only when they implement, derogate from or act within the scope of EU law (this is not always straightforward to establish).

If individuals or businesses consider that an act of the EU institutions directly affecting them violates their fundamental rights, they can bring a case to the Court of Justice in Luxembourg, which (subject to certain conditions) has the power to annul such acts.

Increasingly, the Court of Justice also interprets EU legislation in line with EU Charter rights even when annulment is not sought. A good example is the Google Spain case,.i where the Court of Justice interpreted the EU Data Processing Directive in the light of Articles 7 and 8 of the Charter (right to respect for private life and right to protection of personal data) to create a "right to be forgotten" from internet search engines.2

Individuals who take the view that a national authority has violated the EU Charter, can complain to the European Commission. The European Commission has the power to start infringement proceedings against the Member State.3 However, based on a recent study by Professor Olivier De Schutter, it appears that such proceedings are little used in practice where fundamental rights are breached.

Individuals can also bring actions in their national courts against Member States (and in limited cases individuals4) who breach the EU Charter.5 These courts are able to refer cases to the Court of Justice for a preliminary ruling where there is an issue on the interpretation or applicability of an EU Charter right.

Unlike the enforcement system in the Council of Europe, which has a significant political component, the enforcement of fundamental rights in the EU is largely a legal affair, reflecting the Court of Justice's role in interpreting and enforcing EU law within Member States and the EU institutions. In that regard, the Court of Justice has powers, under Article 260 of the TFEU, to require Member States to comply with its judgments, including the imposition of a lump sum and/or a penalty payment for non-compliance.6

Other ESC rights

ESC rights are also protected at EU level, for example through discrete pieces of legislation such as EU rules on workers' rights. Much of this has been brought into effect via UK legislation and can be enforced in UK courts and employment tribunals.7 The European Commission, can however, bring infringement proceedings and cases can be brought to the Court of Justice.

How are ESC rights currently protected and enforced in Scotland?

UN treaties

Treaties are entered into by the UK Government. The Scottish Government does not have this power as international relations are reserved. It does, however, have the power within the limits of legislative competence to observe and implement the UK's international obligations. Within these limits it can therefore, legislate in the field of ESC rights.

The UK takes a “dualist” approach to international law (i.e. international law and national law are viewed as two separate systems). Consequently, international treaties signed by the UK Government do not normally give individuals legal rights in UK courts unless they are first brought into UK or Scottish legislation in some way (i.e. incorporated into national law) following parliamentary scrutiny.

As a result, although the devolution settlement requires the Scottish Government to respect ‘international obligations’,i the ESC rights in UN treaties (for example in ICESCR) only give rise individuals rights in Scottish courts where these rights have been transformed into domestic legislation by either the UK or Scottish Parliaments.

As the UN treaties have not been incorporated en masse into UK/Scots law, this means that, at the moment, enforcement of the UN's ESC obligations normally takes place at the level of international law/politics, or through national policy development, rather than in the Scottish courts.

European Convention on Human Rights and EU law

The position of the UN treaties can be contrasted with:

ESC rights in the EU Charter - these can currently be enforced in the Scottish courts due to:

The European Communities Act 1972, which gives EU law (including the EU Charter) priority over conflicting national law; and

The Scotland Act 1998 which allows Scottish legislation or executive action to be struck down if they are incompatible with the EU Charter

ESC rights in the Convention - these can be enforced in the Scottish courts due to:

The Human Rights Act 1998 which incorporates the Convention into UK law and:

requires legislation to be read so far as possible in a way which is compatible which Convention rights;

makes it unlawful for public authorities to breach the Convention

enables a court to issue a “declaration of incompatibility” if UK legislation is not compatible with Convention rights (this does not automatically invalidate the legislation; the UK Parliament may decide to leave it in place); and

The Scotland Act 1998 which allows Scottish legislation or executive action to be struck down if they are incompatible with the Convention

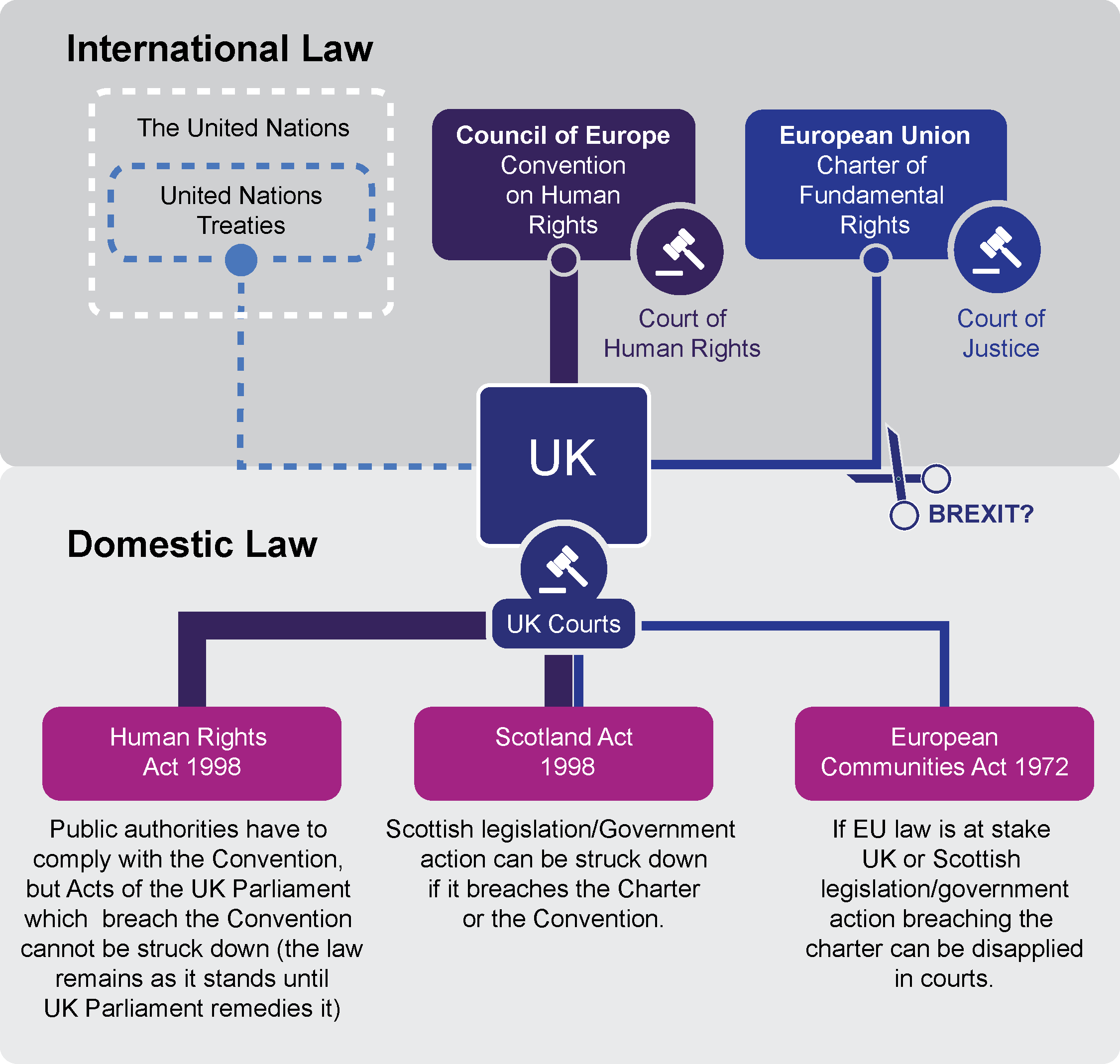

The diagram below explains how human rights enforcement works in the UK.

As can be seen in the diagram, the UN treaties have an influence on UK law but cannot be relied on in court (denoted by the perforated line). In contrast, the European instruments – the Convention and the EU Charter - are treated as sources of UK law by UK courts, and also have independent courts at a European level (denoted by the gavel symbol).

As indicated in the diagram, Brexit will break the link between the UK and the EU's Charter of Fundamental Rights.

On that point, it should be noted that the UK Government's European Union (Withdrawal) Act does not incorporate the Charter into domestic law as part of the retained EU law which will apply in the UK after Brexit (Charter rights, will therefore cease to exist after Brexit). The UK Government position it that the rights in the Charter are protected in a number of other ways including through legislation, the Convention and retained EU law.1 On 15 May 2018 the Scottish Parliament approved Motion S5M-12223, which stated that it did not consent to the the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill on the basis that it would, "constrain the legislative and executive competence of the Scottish Parliament and Scottish Government".

This position can be contrasted with the Scottish Government's European Union (Legal Continuity) (Scotland) Bill which was passed by the Scottish Parliament on 22 March 2018 and which retains the Charter as regards devolved matters.2 The Continuity Bill is the subject of a legal challenge in the Supreme Court by the UK Government. The case will be heard on 24-25 July 2018.

More details on how human rights, including ESC rights, are protected and enforced in Scotland can be found in Dr Kirsteen Shields' SPICe briefing "Human Rights in Scotland" (pages 10-20).

What relevance do ESC rights have for politics and policy in Scotland?

Although not always expressed in human rights terms, ESC rights have played a key part in politics and policy-making in Scotland in recent years, in particular in relation to arguments around land reform, children's rights, social justice, inequalities, and Scotland's relationship with the EU.

For example, the land reform debate in Scotland, which in the past was often associated with historical events, is increasingly characterised by an approach which takes account of sustainable development, the public interest and the balancing of ESC rights with property rights. Legislation in this field since devolution includes:

the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, which introduced a rural community right to buy land

the Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 2003 which gave certain tenant farmers a right of first refusal on buying their farm when the landlord wants to sell

the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 which provides for a right to buy land to further sustainable development.1

the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2016 which extends the right to buy rules to non-rural areas in Scotland2

In the field of children's rights, section 1 of the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 directly referred to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, putting Scottish Ministers under a duty to:

keep under consideration whether there are any steps which they could take which would or might secure better or further effect in Scotland of the UNCRC requirements

ESC rights have also been part of the debate surrounding austerity, welfare rights and the appropriate response to the financial crisis.

A good example is the UK Government's Welfare Reform Act 2012 which restricted housing benefit entitlement for claimants deemed to have a spare room (also known as the bedroom tax). 3 The Scottish Government responded to this legislation by extending the Discretionary Housing Payments scheme to cover the shortfall in tenants' weekly rent due to the bedroom tax. The Scottish Parliament's Welfare Reform Committee also examined various aspects of the proposals in 2013 and concluded in an interim report that they "may well breach tenants' human rights".4

Similar issues exist in the private sector, where there are also limits to the maximum housing benefit payable against rent (set in relation to both household size and local market rents).5 It is worth noting that the Scottish Government has not chosen to fully mitigate shortfalls in private tenants' rents in a similar way to its response to the bedroom tax.

More recently, the issue of ESC rights arose in the context of the Scottish Government's Social Security (Scotland) Bill. The Bill included a reference to the right to social security as one of the fundamental principles of the proposed new devolved social security system and indicated that it is "essential to the realisation of other human rights".

There was a degree of debate in relation to ESC rights during the course of the Bill's parliamentary consideration. Attempts were made to amend the Bill at stage 2 so that the Scottish Ministers, other public authorities and the courts would be required to have due regard to the right to social security, as defined in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), when exercising their functions under the proposed legislation. However, a number of MSPs from different parties questioned the appropriateness of using ICESCR to create rights in this way and the amendments were not agreed to.6 In a statement responding to the rejection of this amendment, Judith Robertson, Chair of the Scottish Human Rights Commission indicated that

It is disappointing that parliamentarians and the Scottish Government have not taken the opportunity to strengthen accountability in relation to the human right to social security in this important piece of legislation ... we look forward to serious consideration being given to the incorporation of international human rights in Scots law going forward.

Scottish Human Rights Commission. (2018, February 8). Commission responds to Scottish Parliament decision to reject 'due regard duty' in Social Security (Scotland) Bill. Retrieved from http://www.scottishhumanrights.com/news/commission-responds-to-scottish-parliament-decision-to-reject-due-regard-duty-in-social-security-scotland-bill/ [accessed 18 May 2018]

It is worth noting that a government amendment to the Bill places a similar duty on the independent Scottish Commission on Social Security. Once established, the Commission must, “have regard to any relevant international human rights instruments” when preparing reports on draft regulations (s.55A)(4) of the Bill as passed). These instruments include, in particular, the ICESCR (s.6B(5)(b)).

ESC rights are also part of the debate around the implementation of the "socio-economic duty" on public authorities. This duty is set out under Part 1 of the Equality Act 2010, but was never brought into force. It requires listed public authorities to give due regard to the desirability of exercising strategic decisions in a a way, "designed to reduce the inequalities of outcome which result from socio-economic disadvantage".

The First Minister indicated in 2016 that the Scottish Government would take action to commence the socio-economic duty in Scotland (Scottish Parliament Official Report, 26 May 2016). This pledge was then confirmed in the Fairer Scotland Action Plan (2016).

The duty came into force on 1 April 2018, under The Equality Act 2010 (Commencement No. 13) (Scotland) Order 2017i (21 November 2017). On 23 November 2017, a Scottish Government news release announced the duty as the ‘Fairer Scotland Duty’. For further details see the SPICe blog on the Fairer Scotland Duty.

Brexit has also been connected with ESC rights as arguments have been made that it could lead to a negative impact on social protections in the UK, such as rules on non-discrimination and workers' rights stemming from EU law.8 However, others have argued that changes are unlikely as these rights are covered by primary legislation, sometimes go beyond the EU rules and are engrained in British culture - the implication being that any changes would lead to a significant cross-party political backlash.

Brexit has also led to questions about the importance of ESC rights in the EU's Charter of Fundamental Rights (EU Charter) to the UK, particularly given the UK Government's decision not to include the Charter as retained EU law in the European Union (Withdrawal) Act. The issue is of particular relevance to Scotland as the Scottish Government's Continuity Bill, which was passed by the Scottish Parliament on 22 March 2018, takes a different approach and retains the EU Charter for devolved areas of law - see the SPICe briefing on the Continuity Bill.

It is also worth noting that the Equalities and Human Rights Committee is undertaking an inquiry on Human Rights and the Scottish Parliament.ii The inquiry will consider how the Scottish Parliament can be a human rights guarantor, which promotes and protects human rights in Scotland. The inquiry will look at human rights, including ESC rights, in the context of how the Scottish Parliament legislates, conducts inquiries, and scrutinises the Scottish Government's budget and policy decisions. A call for evidence was held between 21 January and 16 March 2018. The Committee has heard oral evidence and the inquiry is expected to conclude in the coming months.

ESC rights are also likely to be part of future policy-making in Scotland.

In that regard, the 2017-18 Programme for Government, A Nation with Ambition, commits the Scottish Government to action that gives effect to the ESC rights set out in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the European Social Charter and other treaties.

In addition, the scope of human rights in Scotland, including ESC rights, is currently being examined by an expert advisory group set up by the Scottish Government - the First Minister’s Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership. The first meeting of this group took place on January 17 and 18. It is set to make recommendations by the end of 2018.

Since ESC rights are linked to economic policy, arguments for more devolution and social justice, and relations with the EU, it seems likely that they will remain at the forefront of politics in Scotland in the coming years.

Could UN-based ESC rights be incorporated into Scots law?

Although the UN Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) recommends formal incorporation of the main ESC rights treaty (ICESCR) into national law, there is no obligation on states to do so.

Provided that states use “all appropriate means” to give effect to their treaty obligations under ICESCR, these can be protected by other methods, including domestic legislation.1 This position is broadly the same for other UN treaties.

The approach of the Scottish Government, along with the UK, has not been to incorporate the relevant UN treaties into national law in their entirety, but instead to give effect to treaty rights through discrete elements of domestic legislation, e.g. the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 and the Fairer Scotland (Socio-Economic) Duty.

In recent times, however, questions been raised as to whether other approaches to implementing international ESC rights might be more appropriate or desirable in Scotland, for example incorporating UN treaties in some way into Scots law.

For example, in December 2014 the Dean of the Faculty of Advocates, now Lord Advocate, James Wolffe QC, considered the issue of incorporation in a lecture given on International Human Rights Day.

The lecture explained that possible options for implementing UN obligations could include:

Full constitutionalisation - putting UN ESC rights on a par with the way in which the Convention and the EU Charter are dealt with in the Scotland Act 1998, by allowing legislation or executive action to be struck down if they are incompatible with ESC rights

The Human Rights Act model - using a slightly lighter touch than the approach in the Scotland Act 1998 and not permitting courts to strike down legislation, but leaving it to Parliament to decide whether or not it needs amending

The rights of the child model - following Welsh and Scottish legislationi on children's rights which require Welsh and Scottish Minsiter to respectively have due regard or to keep under consideration requirements in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)

In his lecture Mr Wolffe did not take a view on which of these options would be appropriate, or indeed if they are preferable over the status quo. However, he explained that factors which would have to be considered would include:

whether or not it is desirable to take the ultimate responsibility for ESC rights out of the hands of the legislature or executive

the degree to which Scottish courts would be in a position to be able to adjudicate on ESC rights

Mr Wolffe ultimately concluded that further debate on this issue was needed:

If, as a society, we consider the progressive realisation of economic and social rights (or, at least, particular economic and social rights) to be amongst the fundamental commitments to which we collectively adhere, is there not a case for that to be reflected in our law – even in our constitutional or basic law? Should we give our own citizens the power to hold their government to account for the manner in which it addresses those commitments? No doubt there will be disagreement on these questions – but it seems to me that, if we take seriously the indivisibility of fundamental rights, this is a debate which we should have.

The issue of incorporation has since been investigated in more detail at a conference in December 2015 held as part of a programme of events delivered under the banner of Scotland's National Action Plan for Human Rights (SNAP). The Fist Minister delivered the keynote address and the legal status of ESC rights in Scotland, including the possibility of incorporation, was examined in a paper drawn up by Dr Katie Boyle. Dr Katie Boyle also submitted evidence on the incorporation of ESC rights into national law to the Equalities and Human Right Committee as part of its 2018 inquiry into Human Rights and the Scottish Parliament.

The Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC )is currently carrying out a series of workshops on the various aspects of ESC rights and is due to publish a report on options for incorporation in the coming months.

The First Minister’s Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership, which is to report by the end of 2018, is also due to consider the potential effects of the incorporation of human rights treaties into domestic law and the means by which this might be undertaken.

On 21 March 2018, in response to a parliamentary question on incorporation from Andy Wightman MSP, the then Cabinet Secretary for Communities, Social Security and Equalities Angela Constance indicated that the Scottish Government was awaiting the report of the advisory group, but that:

we are clear that any mechanism that is designed to secure the further incorporation of international treaties must be practical and deliverable and must result in genuine improvements in the daily lived experience of individuals across the whole of Scottish society.

Scottish Parliament. (2018, March 21). Official Report - Meeting of the Parliament 21 March 2018 [Draft]. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11434&i=103881#ScotParlOR [accessed 23 March 2018]

What is the general rationale behind the need for ESC rights?

As explained elsewhere in this briefing, many ESC rights are contained in international treaties and are therefore binding on the UK under international law.

Irrespective of the legal position, it is worth outlining some of the more general policy arguments which stress the importance of ESC rights.

One of the most fundamental arguments in favour of ESC rights is that minimum rights are essential to protect basic human needs (such as access to shelter, food etc.).

A key part of this argument is that ESC rights are inextricably linked to the general goal of modern human rights legislation - i.e. the protection of human freedom and dignity. For example, the UN resolution in 1952 which proposed protecting ESC rights notes that:

when deprived of economic, social and cultural rights, man does not represent the human person whom the Universal Declaration regards as the ideal of the free man

United Nations. (1952, February 5). Preparation of articles on economic, social and cultural rights.. Retrieved from http://hr-travaux.law.virginia.edu/international-conventions/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights-icescr [accessed 22 October 2017]

There is also an argument that individuals' basic needs have to be satisfied before more complex political rights can be realised. In that regard, the Center for Economic and Social Rights, a human rights NGO, notes that:

the right to speak freely means little without a basic education, the right to vote means little if you are suffering from starvation.

Center for Economic and Social Rights. (2017). What are Economic, Social and Cultural rights?. Retrieved from http://www.cesr.org/what-are-economic-social-and-cultural-rights [accessed 31 October 2017]

Arguments for ESC rights go beyond the need for minimum standards, however. They are also linked to calls for increased social justice and to protection for the most economically and socially vulnerable (particularly in response to economic crises).3 4 On this point, the Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC) argues that a key advantage of ESC rights is that they create a framework which can be applied to policy decisions. It notes that:

human rights provide both a legal and conceptual foundation to social justice, as well as the means to put it into practice. Human rights are non-political, international legal standards; they are also a set of values and principles that can be applied outside the courtroom, throughout public policy and services

Scottish Human Rights Commission. (2015, December). Creating a Fairer Scotland: A Human Rights Based Approach to Tackling Poverty. Retrieved from http://www.scottishhumanrights.com/economic-social-cultural-rights/ [accessed 23 October 2017]

The SHRC also explains that the use of legal rights rather than political goals is crucial since:

The international human rights system ... provides both a minimum floor and progressive legal standard for social justice. Tackling poverty through human rights de-politicises what it is a matter of law, rather than viewing it as a matter of charity, principle or political aspiration.

Scottish Human Rights Commission. (2015, December). Creating a Fairer Scotland: A Human Rights Based Approach to Tackling Poverty. Retrieved from http://www.scottishhumanrights.com/economic-social-cultural-rights/ [accessed 23 October 2017]

This focus on integrating human rights into policy is a key element of the SHRC's work and is part of what it refers to as a "human rights based approach" - in other words using international standards as a framework for putting people’s human rights at the centre of policy and practice7 Examples of recent work based on this approach include:

Supporting residents in Leith to use ESC rights as a tool for challenging poor housing conditions.

Using ESC rights to improve the quality of health and social care services8

There are also arguments that promoting ESC rights makes for more inclusive societies. For example, in a recent report on the state of democracy in Europe, the Council of Europe argues that:

Political systems seen to protect social rights are likely to command greater levels of public confidence. In addition, the cohesive quality of these rights has taken on a new importance against a backdrop of ongoing austerity, rising populism and in the fight against violent extremism and radicalisation. By promoting equal opportunity, social rights encourage individuals to remain within mainstream society and help lessen the appeal of other, more extreme or divisive paths.

Council of Europe. (2015). Stete of Democracy, Human Rights and the Rule of Law in Europe - a shared responsibility for democratic security in Europe Report by the Secretary General of the Council of Europe. Retrieved from https://wcd.coe.int/com.instranet.InstraServlet?command=com.instranet.CmdBlobGet&InstranetImage=2742889&SecMode=1&DocId=2263108&Usage=2

More generally, there is an argument that ESC rights are central to healthy democracies, on the basis that:

Destitute, hungry people don’t vote, and idle, hungry people have no patience for the slow, often tedious haggling among often sharply differing groups that democracy requires

Grossman, Claudio, et al. "A Festschrift in Honor of Seymour J. Rubin". American University International Law Review 10, no. 4 (1995): 1215-1274.. (1995). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1447&context=auilr [accessed 31 October 2017]

What criticism is there of ESC rights?

Although many ESC rights are contained in international treaties and are therefore binding under international law, criticism of them, and their scope, does exist.

One of the main strands of critique is that creating legally enforceable economic rights damages the democratic process and puts too much power in the hands of the judiciary.

A proponent of this view is the human rights campaigner and co-founder of Human Rights Watch, Aryeh Neier. In an article entitled "Social and Economic Rights: A Critique" he argues that:

the purpose of the democratic process is essentially to deal with two questions: public safety and the development and allocation of a society’s resources ... Economic and security matters ought to be questions of public debate ... Therefore, everybody ought to be able to take part in the discussion. It should not be settled by some person exercising superior wisdom ... These issues ought to be debated by everyone in the democratic process, with the legislature representing the public and with the public influencing the legislature in turn. To suggest otherwise undermines the very concept of democracy by stripping from it an essential part of its role.

Neier, Aryeh. "Social and Economic Rights: A Critique." Human Rights Brief 13, no. 2 (2006): 1-3.. (2006). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1254&context=hrbrief [accessed 1 November 2017]

Broadly speaking, the argument is that, since ESC rights deal with the redistribution of resources, they are inextricably linked with politics and political choices. As a result, they should not be given the same protection as civil and political rights aimed at protecting against abuse of power.2

Linked to this is the view that courts do not have the capacity or tools to adjudicate on ESC rights.3 According to this view, ESC rights are open to a wide variety of different interpretations and involve complex economic choices which courts should not be required to consider. In other words they are "non-justiciable."4

On this point, Neier gives an example linked to the right to health care:

Consider the question of health care. One person needs a kidney transplant to save her life, another needs a heart-bypass operation, and still another needs life-long anti-retroviral therapy. All of these are life-saving measures, but they are expensive. Then there is the concern about primary health care for everyone. If you are allocating the resources of a society, how do you deal with the person who says they need that kidney transplant or that bypass or those anti-retroviral drugs to save their life when the cost of these procedures may be equivalent to providing primary health care for a thousand children? Do you say the greater good for the greater number, a utilitarian principle, and exclude the person whose life is at stake if they do not get the health care that they require? I do not believe that is the kind of thing a court should do.

Neier, Aryeh. "Social and Economic Rights: A Critique." Human Rights Brief 13, no. 2 (2006): 1-3.. (2006). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1254&context=hrbrief [accessed 1 November 2017]

Another related element of critique is aimed at the use of fundamental or constitutional rights (as opposed to policy or legislation) to further economic or social goals.

For example, in an article from 1993 which considered new constitutions for post-communist countries, Professor Cass Sunstein argued that:

there is a big difference between what a decent society should provide and what a good constitution should guarantee. A decent society ensures that its citizens have food and shelter; it tries to guarantee medical care; it is concerned to offer good education, good jobs, and a clean environment ... But a constitution is in large part a legal document, with concrete tasks. If the Constitution tries to specify everything to which a decent society commits itself, it threatens to become a mere piece of paper, worth nothing in the real world.

Sunstein, C. (1993). Cass R. Sunstein, "Against Positive Rights Feature," 2 East European Constitutional Review 35 (1993).. Retrieved from http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=12187&context=journal_articles [accessed 1 November 2017]

There are also arguments which suggest that ESC rights may not actually lead to any improvements in the policy areas protected.

An example is the data analysis carried out by Professor Christian Bjørnskov of Aarhus University and the Danish human rights lawyer, Jacob Mchangama. 7 This found, "no effects of health rights on immunization rates or life expectance, regardless of whether they are justiciable or not." The analysis also explained that ESC rights may have negative effects in certain areas, possibly due to governments reallocating scarce resources towards those more likely to claim ESC rights. 8 It therefore concluded that:

while the constitutionalization of social and economic rights has been a victory for human rights activists, it is not clear that it has done very much for the people who were supposed to benefit

Mchangama, J. (2014, July 29). Legalizing economic and social rights won’t help the poor. Retrieved from https://www.opendemocracy.net/openglobalrights/jacob-mchangama/legalizing-economic-and-social-rights-won%E2%80%99t-help-poor-0 [accessed 11 November 2]

More recently, a movement has emerged which stresses that economic rights, in particular property rights, can potentially conflict with environmental protections.

This argument is particularly relevant to climate change and global warming. Legal scholars and sustainability activists have argued for some time that, instead of focusing purely on current economic needs, there needs to be more thought for the rights of future generations from protection against environmental harm, due for example to global warming.10

There can, therefore, be instances when environmental rights and ESC rights conflict, and where a balance may need to be found between different rights. A good example is the recent Scottish Government proposal to ban plastic straws in Scotland, which has led to questions as to the need for exemptions for those with disabilities who may need to use straws to drink. 11