Attracting and retaining migrants in post-Brexit Scotland: is a social integration strategy the answer?

This report explores whether introducing a social integration strategy for all migrants in Scotland could support the goal of attracting and retaining people here. It presents the results of a qualitative research project proposed and carried out by Dr Paulina Trevena (University of Glasgow) as part of the SPICe Academic Fellowship programme, based on individual and group interviews scoping a broad variety of views on the issue.

Executive Summary

This report explores whether introducing a social integration strategy for all migrants in Scotland could support the goal of attracting and retaining people here. It presents the results of a qualitative research project proposed and carried out by Dr Paulina Trevena (University of Glasgow) as part of the SPICe Academic Fellowship programme, based on individual and group interviews scoping a broad variety of views on the issue.

Since immigration policy is a reserved matter, Scotland is in competition for people with the rest of the UK. Meanwhile, even though Scotland needs to grow its population predominantly through immigration, it has no general strategy for attracting, welcoming or retaining migrants. Therefore, ‘soft levers’, such as migrant integration policies or international outreach activities, which can be implemented within current policy and legislative frameworks, should be considered.

The research shows that Scottish society, though seen as welcoming and friendly towards incomers, is not free from prejudice and is not generally supportive of maintaining or increasing current levels of immigration to Scotland. There is little awareness of the need for sustained immigration to Scotland. Attitudes towards migrants vary considerably depending on location and section of society, and are most negative among people living in areas of multiple deprivation where the competition for resources is strongest (and where many migrants live at the same time). Moreover, there are many concerns around immigration, including the isolation and ‘non-integration’ of migrant communities, especially in rural areas. The research results thus point to a need for a social integration strategy in the interests of strengthening community cohesion, preventing prospective tensions in future, and preparing Scottish society for further immigration. Political leadership is seen as paramount in shaping positive attitudes towards migrants.

In order to support community cohesion, equality and inclusiveness, the integration strategy should ideally be mainstreamed with scope for addressing particular migrant needs (such as language support) within it. Moreover, while the standardisation of certain policies at national level would be beneficial (particularly with regards to policy and local media discourse around migration; policies around EAL (English as an Additional Language) and ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) in the Scottish education system; recognition of foreign qualifications; diversity training for public service providers; and a reception strategy for new arrivals), it needs to allow for flexibility in applying integration strategies at local level. There are a number of current and past policies and practices, in Scotland, the UK and around the world that can be drawn on in designing the strategy.

Finally, providing migrants’ basic needs are met (secure legal status, employment, housing, access to education for children), the research shows that a social integration strategy which creates a welcoming atmosphere and fosters good community relations could add to Scotland's competitive edge within the UK and support the aim of growing its population through migration.

The report concludes that Scotland would benefit from introducing a social integration strategy for all migrants, providing it is mainstreamed and aimed at supporting the inclusion of everyone into local communities and within the wider society, regardless of their ethnic background. Such a strategy would furthermore support the goal of attracting and retaining migrants in Scotland.

Background to the research: migration and integration in Scotland

This report explores whether introducing a social integration strategy for all migrants arriving and living in Scotland could potentially act as an attracting and retaining factor. Before we proceed with the rationale behind this idea, we need to define the basic concept informing the study, namely integration.

The concept of integration is commonly used in academic and public debate but often understood in different ways.1 The variation in understandings and expectations of integration is also reflected in the different policy approaches adopted by nation-states (or sub-regions) across the world, the two major approaches being the traditional assimilationist model (which requires migrants to fully adapt to the culture and values of the receiving society) and the multicultural model (which recognises and supports the maintenance of the distinct cultural heritage of newcomers).2 Regardless of which model a given country or region follows, the basic premise of an integration policy is to support the inclusion of immigrants into (given domains of the life of) the receiving society. Some policies may focus on newly arrived immigrants in particular (‘reception policies’), others may be focused on the long-term inclusion of immigrants.3

For the purposes of our study and this report, integration is defined as a two-way process of:

interaction between migrants and the individuals and institutions of the receiving society that facilitate economic, social, cultural and civic participation and an inclusive sense of belonging at the national and local level.4

Integration thus involves a range of actors: the immigrants themselves but also the governments, institutions and local communities of the receiving country.5 Moreover, integration is a very broad notion encompassing a number of domains such as economic, political, institutional, cultural, and social integration.i However, while we acknowledge the importance of all these domains, the focus of this report is on social integration in particular, here understood as having connections with others in the local community, not only other migrants but also with members of the established community, and feeling accepted within and part of the community. Considering our interpretation of integration as a two-way process involving both the migrants and the local communities they live in, we see the local communities’ attitudes towards migrant populations and their expectations around integration as of equal importance for the process of social integration.

In this section we will discuss what processes and policy developments have informed this study and inspired us to look into the idea of introducing an integration strategy for all migrants in Scotland. We shall also shortly describe the research and set out the questions which will be addressed in the report.

Scotland's demographic situation and migration

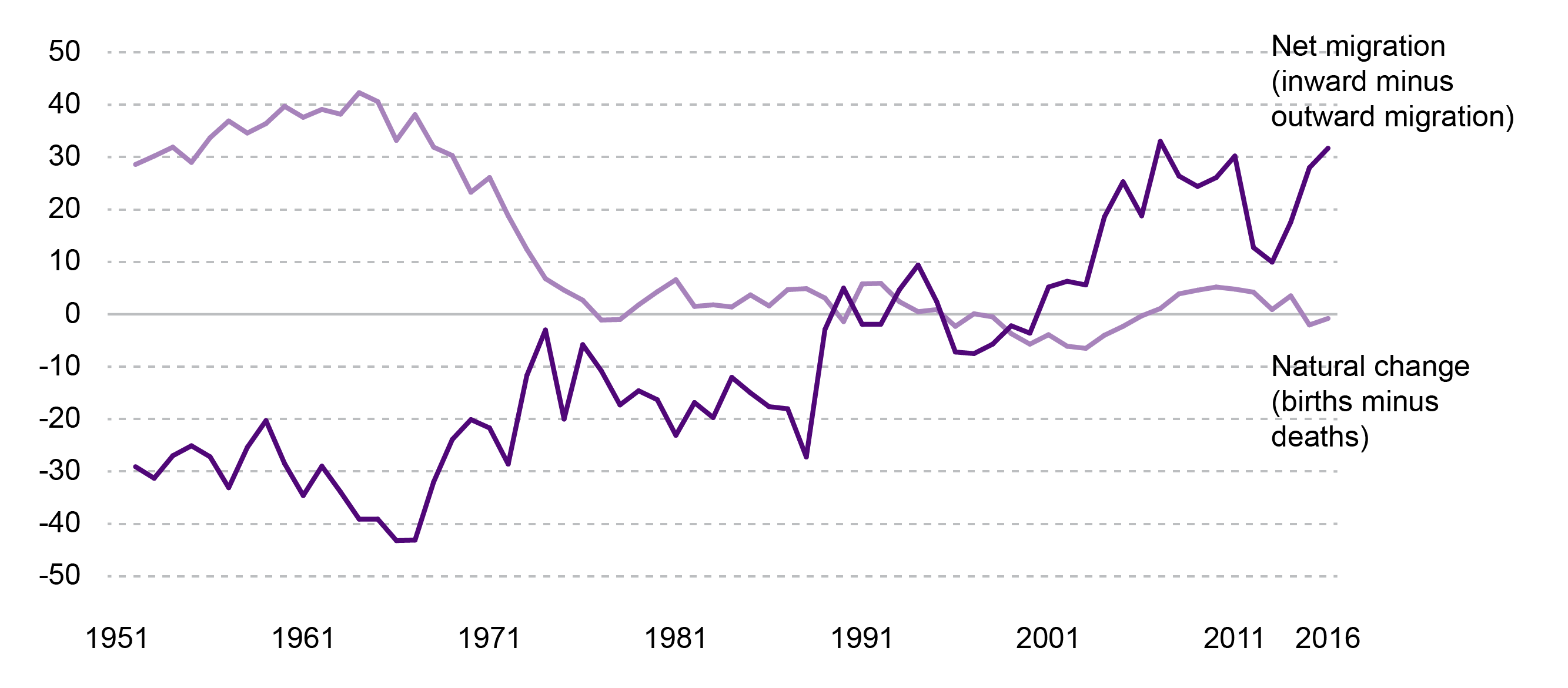

Scotland's demographic situation is distinctive within the UK. Similarly to the whole of the UK, Scotland has an ageing population. However, while fertility rates in all countries of the UK have fallen over the last decade, they are falling at a faster rate in Scotland. Moreover, fertility rates in Scotland have been lower than in other parts of the UK since the 1980s. The current fertility rate in Scotland is 1.52 as compared to 1.97 in Northern Ireland, 1.82 in England and 1.77 in Wales.1 Therefore, in order to sustain its population (and economy) in the future, Scotland needs to grow its population through migration, be it from other parts of the UK or from overseas.23

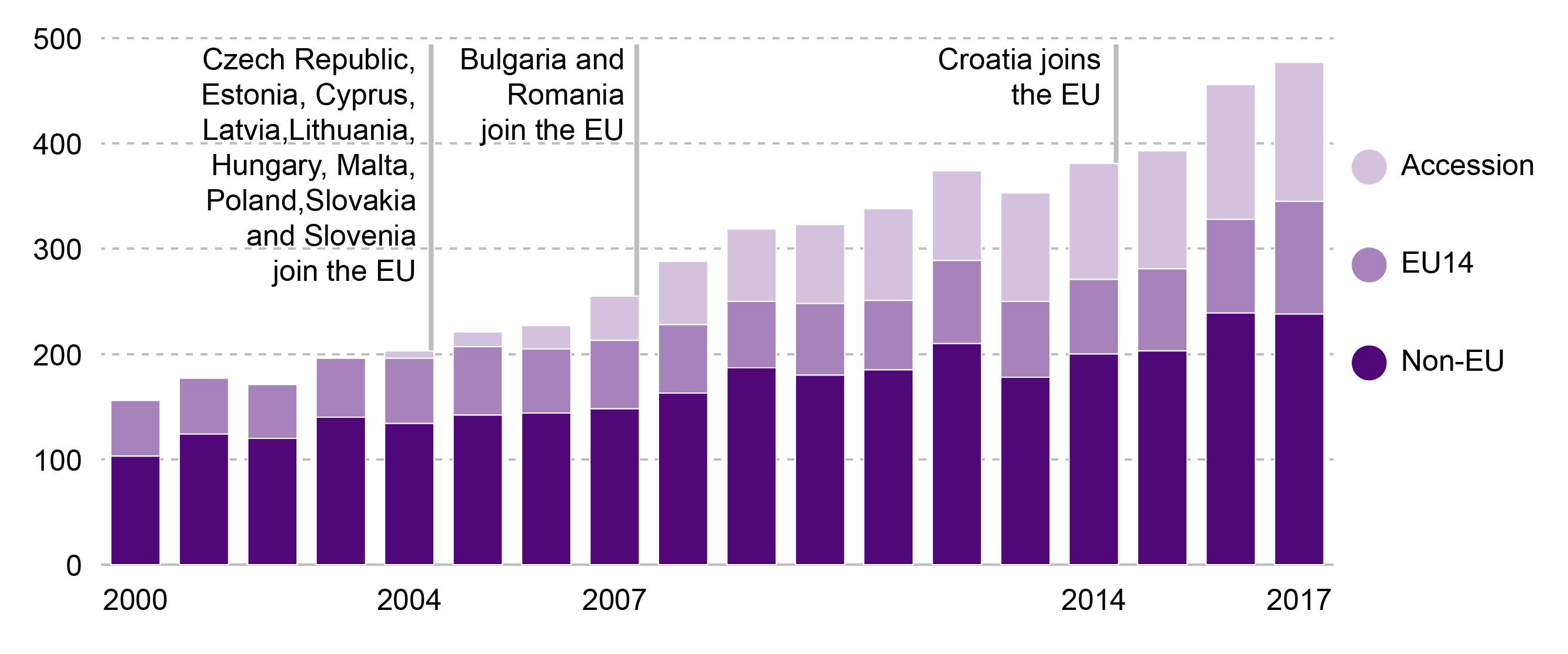

Historically, Scotland has been a country of net out-migration, with higher numbers of people leaving the country than coming to live here. It is only since the early 2000s that this trend has been reversed and Scotland has entered a period of sustained population growth (Chart 1). As can be seen from Chart 2 below, international migration from both EU and non-EU countries has played a key role in the process, with a particularly dynamic increase in migration flows from the countries of Central and Eastern Europe since the 2004 EU Enlargement.

EU migration currently plays a significant role in Scotland's population and economic growth, especially in rural areas. However, migration flows from the EU are projected to decline as a result of Brexit.3 The UK's decision to leave the EU and curb free movement is therefore a source of great concern for Scottish policymakers. It is clear that Scotland needs to continue growing its population through migration yet, considering that immigration policy is a reserved matter, the question is – how?

The policy context: attracting and retaining migrants in (post-Brexit) Scotland

Even though immigration is a reserved matter and Scotland is restricted by UK immigration policy, there is still scope for applying measures aimed at attracting and retaining migrants, both from abroad and from other parts of the UK, within current policy frameworks. However, since Scotland is in competition for people with the rest of the UK, it needs to consider how it may differentiate itself as a more attractive destination for settlement and to increase migrant retention rates.

Within available policy frameworks, the most obvious answer is by applying ‘soft levers’ aimed at attracting and retaining people.i For example, Scotland could design a programme of international and national outreach in order to attract people, and develop reception and integration strategies to support their retention. In order to be effective, these strategies need to be combined as high attraction rates do not necessarily equal high retention rates. Analyses of programmes aimed at attracting migrants into certain areas of Australia and Canada underline that if the local area is not seen as welcoming by the newcomers, or they are not supported through integration and inclusion programmes after arrival, they are less likely to stay in their original location.1 Therefore, while work, housing and educational opportunities all play a crucial role in attracting migrants to certain areas, it is their everyday experiences within their local communities that may be key to their decision to stay or leave.23 This is an important finding in terms of addressing population decline through migration, especially in rural areas of Scotland which often have little experience of immigration, limited support for newcomers, and less positive attitudes to migration than in larger urban centres.4

Immigrant integration in Scotland - policies

In terms of immigrant integration, Scotland has started doing some ground-breaking work (within the UK) through introducing the New Scots Integration Strategy in 2014. This is a holistic initiative aimed at refugees and asylum seekers which covers such areas as housing, language, education, health and well-being, employability and welfare rights, and social connections. The strategy is essentially based on the principle of partnership working, at both local and national level, and pulling resources together to support refugees and asylum seekers in integrating into communities in Scotland.1 The New Scots strategy is flexible; it provides a framework and guidelines, yet local councils and their partners implement it in various ways depending on available resources and local needs. While the ‘New Scots’ strategy is dedicated specifically to supporting a relatively small number of particularly vulnerable migrants, it provides a good basis for evaluating the strategies developed and implemented so far, and to review what has worked well - or not - and why. Recent evaluations of the strategy point to the need for stronger support of social integration in particular: while social connections are very important for ‘New Scots’ they often feel they have not been able to develop these effectively within their local communities.1 Notably, this is not an issue particular to refugees and asylum seekers: many migrants arriving in Scotland face barriers to establishing links with the wider society, regardless of their immigration status.3 Therefore, the idea of introducing a national-level social integration strategy covering all categories of migrants has considerable merit and should be considered.

The research

The research for this project was carried out between January and March 2018. This qualitative study was based on individual and group interviews with people from a range of backgrounds: third sector, academia, local council officers, employers (in agriculture, hospitality and tourism), different categories of migrants (asylum seekers, refugees, economic migrants, highly skilled migrants, students and those arriving as family members), and members of established populations. Altogether, 13 focus group discussions and 13 individual interviews (with those who could not participate in the focus groups) were conducted and altogether 116 people participated in the study. The research included people living in cities and in rural areas of Scotland.i

The overarching aim of the study was to scope opinion on the idea of introducing a social integration strategy for all migrants arriving in and already living in Scotland, and its potential as an attracting/retaining factor. Therefore, we focused on discussing issues around:

integration in Scotland and whether Scotland needs an integration strategy

what approach such a strategy should take, what could it consist of and who should be delivering it

what role could various organisations and institutions play in it

what existing policies, strategies and experiences could be built on in devising such a strategy

whether it could act as a factor in attracting people to Scotland and retaining them here.

Nevertheless, the discussions were much broader and also included the following themes:

opinions on migration to Scotland and attitudes towards migrants

concerns around migration

local impacts of migration

experiences of living in Scotland (in the case of migrants) and in particular localities

support for migrants available locally

local challenges (other than those related to migration)

local communities and relations with others within the community.

Therefore, the research also provided an in-depth picture of community relations in a few localities, the challenges newcomers, as well as established members of local populations, face in relation to migration and everyday life, and local needs.

This report discusses the following themes arising from the study:

whether Scotland is socially ‘prepared’ to become a country of immigration, taking account of current attitudes towards migration

evaluation of the need for a social integration strategy in Scotland

defining the main aims of the strategy, what approach it should take and what it should consist of

a brief overview of present and past policies and experiences that could be built on in devising an integration strategy

a consideration of who should or could be involved in its delivery

an evaluation of whether it could act as an attracting and retaining factor.

Is Scotland ready to become a country of immigration?

In this section we shall consider whether Scotland is socially prepared to become a country of immigration. First, we shall look at societal attitudes towards migration and whether Scotland is welcoming to newcomers. Next, we will explore what concerns Scots have with regards to immigration into their country. Finally, we shall consider the political climate around migration in Scotland.

Attitudes towards migrants - is Scotland welcoming and inclusive?

Research on public attitudes towards migration in Scotland shows that these are generally more favourable than in other parts of the UK, though not significantly so.1 Moreover, it has been argued that these results should be treated with caution; the slightly less negative attitudes than in other parts of the UK do not mean that Scottish society strongly supports immigration to Scotland. Indeed, research shows that, while more people in Scotland think immigration is good than bad for their country (41% to 31%, respectively), nonetheless 58% support reducing levels of immigration (as compared to 75% in England and Wales).2 Scholars also draw attention to the fact that Scotland has a much lower foreign-born population and lower levels of ethnic diversity than other parts of the UK, and it is this lower exposure to immigration that may have resulted in less hostility to it.345 This might also be the reason why immigration is seen as less of a priority issue in Scotland than south of the border (it is fourth on the priority issues list in Scotland as compared to second in England and Wales).2

Still, survey results show a change in attitudes among Scots during the 2000s with increasing support for the view that immigrants take away jobs from Scottish people and that ethnic minorities pose a threat to Scottish identity.7 They also point to far more negative attitudes displayed by certain sections of Scottish society, namely those with lower income and education levels, and those who feel most Scottish.7 Furthermore, recent analysis of the links between local levels of migration and Brexit-voting in England, Wales and Scotland suggests that the more intense the recent migration waves into certain localities, the higher the proportion of Leave-vote in these areas, and this link is particularly strong in Scotland.9i

All things considered, while attitudes towards migrants are currently less hostile in Scotland than elsewhere in the UK, this does not mean that there is broad support for Scotland to become a country of immigration.10 In view of the projections of population growth predominantly through migration over the next 25 years,11 immigration appears to be important to Scotland's future.

Coming back to our research findings, these supported the argument that attitudes towards migrants in Scotland are generally positive, and this view was shared by native Scots/British people and migrants alike. Scots were very proud of their welcoming culture and would often contrast this with England which they saw as much less welcoming. Some even felt compelled to be more welcoming than people in England:

I think there are people who don't like immigrants of any kind, but when you compare Scotland to England, and in England you've got the EDL going out and having marches, gaining sort of popularity, in Scotland, any time any divisive group like that tries to do anything, the Scottish people will just not have it and put an end to it, (…) because we're protecting our good name and our nature and our reputation for being welcoming.

Local resident, rural area

I agree, sometimes I feel like people in Scotland are like, you have to be more accepting than the English, kind of thing, we're like, no, we're welcoming.

Local resident, rural area

The point that Scots are welcoming was reiterated by many of the migrants, and, interestingly, from those who had experience of living both in England and Scotland in particular. Migrants underlined the friendly nature of Scots and their general willingness to help:

I noticed a massive difference between England and Scotland in terms of people being friendly. I mean honestly, these are absolutely different cultures, completely different nations. In England I suffered prejudice and discrimination and I heard lots of things from locals there. And I lived, what, almost two years in England. And I'm now four, five-ish years in Scotland. I only had positive experiences here in terms of socialising and people being nice, people being friendly, helpful. And even like…I was always surprised, like god, this person is basically stopped working to provide me information and guide me through and show me stuff, da-da-da. On the streets or where[ever] I go… Absolutely everywhere and anywhere I go. And it's really, really impressive, honestly.

International student, city

Moreover, the fact that Scotland had voted to remain in the EU was also seen as a reflection of a more positive attitude to migration:

[C]ompared to England Scotland is… it's still international, but it's also welcoming to foreigners. But also from Brexit results, from the referendum results we can see that it is not the same. And you also feel safer here. I don't know, that's what I feel. After seeing almost 60 per cent of Scottish people voted to stay in the European Union, I felt like wow, I'm safer here.

International student, city

This does not mean that racism and xenophobia are absent from Scottish society. While Scots were generally seen as friendly and welcoming, study participants also mentioned negative experiences, such as work discrimination or instances of verbal and in some cases physical abuse:

I met people that, when they knew I'm a foreigner, they slam the door at me [when I deliver their pizza]. Do all sort of things that don't show respect. There a lot of people who don't like foreigners. Some of them think that foreigners, that they are just here to take their work. (…) So depends on the people, sometimes they don't mind having friends with us. And probably like 60% of common people are alright with foreigners, they speak with them, keep this friendly, engage but not much more.

Migrant, rural area

Notably, however, the one nationality that mentioned frequent instances of hostility towards them were the English, and this was borne out by others’ opinions as well.ii[1] As a half-English study participant from a small town in western Scotland observed:

[W]hen the African boys came to our school, just by chance I was the one that had to show them about, and that was fine, all the boys, everything was going fine, lots of stuff, and they integrated quite well, but then my dad being English, like when he goes into a pub sometimes in [small town in the Highlands] and they don't know that he's got kids here or whatever, he will get a hard time.

Local resident, rural area

The same phenomenon was noted by a local council officer:

[W]hen you look at the sort of hate crime and hate incidents in [our rural council], most of it is anti-English, so very few of our incidents are involving other communities.

Council officer, rural area

Therefore, this study indicates that, while Scots are welcoming in general, anti-English sentiment is still prevalent, particularly in rural areas.

The notion of being ‘welcoming’ also needs to be unpicked here. The Scottish/British people taking part in the research saw both themselves personally and Scotland as welcoming. However, this was understood as lack of (explicitly expressed) racism or anti-immigrant sentiment and/or lack of aggression towards migrants and generally being amicable rather than taking some particular action to welcome newcomers. While reaching out to others in this way may not be part of the Scottish culture, it is nevertheless seen as ‘commendable’. Some migrants mentioned having received support from complete strangers whom they had asked for help at the beginning of their stay (rather than trying to seek support from state institutions or organisations).

None of the Scottish/British study participants mentioned reaching out to people who were new to their community. Migrants mentioned this as an issue as well. Rather, there was an expectation that the onus was on newcomers to make an effort to somehow become part of the community. Indeed, some migrants remarked how much local people valued any efforts on their part to join into community activities, such as joining local clubs:

Local people much appreciate when foreigners try to get into community. I’m now in [small town in North East Scotland] community group on Facebook and two days ago there was litter picking. There was a poster, meeting there and there, and one, I think Polish girl asked where the place was where we meet and there was a lot of comments that local people, you know, somebody just liked, somebody said, welcome new member to that group… yeah, I think they really appreciate this. When foreigners try to join them.

Migrant, rural area

There was little mention of any encouragement for migrants to join local clubs and little awareness of the different barriers to participation they might face. Migrants often mentioned a number of issues which stopped them from participating in community activities:

poor knowledge of English

shyness and not knowing how to take the first step

different cultural norms and lack of understanding of the local culture

lack of knowledge of what was happening locally and where they could find information about activities and events, and

a number of barriers connected to work e.g. unsociable hours, childcare and finances.

Therefore, while the established populations might see their clubs and activities as ‘open to anyone who would like to join’, the lack of outreach activities means that only the most confident and outgoing migrants (who also speak some English/can afford paid activities) have access to these:

When I came to [small town on the East coast], ESOLiii class – nobody said welcome, I've put my name for this group. And the church also. I can't say people were very friendly for me for the first time. And when I keep going to the same place, people will know where I'm from, and how I lived before I came to Scotland, they get to know me and now very friendly.

Migrant, rural area

While Scotland is generally seen as welcoming, the lack of reaching out to newcomers and creating opportunities for them to mix with the native population have consequences for community relations: what was clearly visible, especially in rural areas, was that the established populations lived quite separate lives from the migrant populations and often had very little knowledge of or links with other populations living in their area (see, for example, de Lima et al 12). Where links between migrants and members of the established populations were forged, this was typically through work or education, yet difficulties with establishing deeper and more meaningful relationships were frequently mentioned by migrants. Rural areas seemed particularly ‘cliquey’ in these terms. While local people would speak about their communities and communal relationships with affinity, they would also admit that ‘breaking into’ their community is not simple, even for people of their own nationality. This was confirmed by those who had moved to the area:

It's just the small town mentality, I think some people like to keep to their own, and it's the same in [small town in Highlands]. I've been there since I was two, I have two sisters there, loads of family, mum and dad, aunties and uncles, and even then some people say I'm not from [this small town].

Local resident, rural area

An added difficulty in many rural areas is the lack of migrant community organisations and/or groups there. While in larger cities there are a number of community groups newcomers can join, including ethnic community groups, this is rarely the case in smaller localities, especially where migration is a fairly recent phenomenon. Ethnic community groups are seen as both a valuable resource for newcomers, a point especially underlined by third sector organisations: they can be a source of advice and support, and become a starting point for wider integration at the same time.iv On the other hand, some study participants raised the point that, if such organisations are ‘too effective’ in supporting migrants, this may lead to an over-reliance on the organisation and in effect impede rather than support the beneficiaries’ wider integration. Therefore, there is a fine line between sufficient support and too much support. However, the general agreement was that migrant organisations can play a crucial role in supporting people in the process of settling in, learning about the country and establishing relationships. In this sense, their absence in many rural areas is seen as problematic.

Even migrants living in cities, where there are many more options for tapping into various resources and mixing with the native population, often still live very separate lives from the Scottish population. This may be due to work or housing segregation, compounded by a language barrier and lack of opportunities to mix with the wider community. However, it need not be - even international students who did not face such barriers mentioned it was difficult for them to establish friendships with their Scottish peers. This was put down to cultural differences above all:

I only had positive experiences here in terms of socialising and people being nice, people being friendly, helpful (…). But I mean this is just like let's say general conversation stuff. When it goes into making friends, so I think things change a bit. But I think that's a cultural thing, cultural characteristics. That for you to get into a social circle [in Scotland] it gets time whilst, for example, if you go to Spain or Italy, people just invite you to go to their houses in the same day. So yeah, I think that's a cultural thing.

International student, city

Therefore, while Scottish people were generally seen as ‘welcoming’ understood as friendly in everyday encounters, migrants felt that establishing deeper and more meaningful relationships with Scots was difficult. As mentioned earlier, not all Scots have a positive outlook on migration. A particular issue raised in discussions was the prevalence of negative attitudes among certain groups and/or in certain locations, such as areas of multiple deprivation. In such environments there is a perception of high competition for (scarce) resources, and the native population often sees migrants as the ‘less deserving’ recipients of state support. This is an extremely inflammatory context for communal relations considering that many migrants are housed in these areas. Third sector organisations in particular saw this as a very problematic issue.

Research participants also suggested that older people have particularly negative attitudes towards immigrants. While the issue of racism among older people was raised by representatives of the younger generation of Scots specifically, it was not mentioned by the migrants themselves. This would suggest that, while negative attitudes towards migration may be more prevalent among the older generation, these may be expressed in family and friendship circles rather than publicly and hence not felt so much by migrants. It is probable that many migrants have little contact with the older generation (apart from those working in e.g. the care sector). Meanwhile, the age group that migrants pinpoint as particularly difficult for them are teenagers, again especially in deprived areas.v

Summing up, Scotland was seen as a welcoming country in general but not free from negative attitudes towards migrants. These are particularly strong among established populations living in areas of multiple deprivation, and especially among teenagers. The older generation of Scots/Brits is also reported to have more negative attitudes towards migrants than younger people, though the impact of this was not felt by the migrant participants of the study. Moreover, urban communities tend to be more open to newcomers than rural communities.

Concerns around migration

Members of established populations, council officers, academics, third sector organisations and employers raised a number of concerns around immigration, each from their particular point of view.

The concerns mentioned by members of the native population were mainly focused on three areas: competition for various types of resources and the financial costs of migration; fears around security and personal safety; and fears around the social effects of migration. The specific concerns in relation to immigration were:

housing – availability of housing and competition for social housing; ghettoization of certain areas inhabited predominantly by migrants; dealing with transient populations (in cities - especially in areas where short-term tenancies are standard and/or where asylum seekers are housed; in rural areas – especially in relation to seasonal migration)

competition for other resources and forms of state support such as school places (in Catholic schools in particular), access to the NHS, benefits

competition for jobs

fears around personal security and migration-related crime, in particular related to free movement where migrants do not need to undergo checks in order to enter the country

migrants’ lack of knowledge of English and the cost of providing language support (interpretation services, language courses)

perceived non-integration of certain migrant populations

fear of losing the traditional Scottish/local identity and culture, of migrants ‘taking over’ culturally.

Local councils, on the other hand, mainly expressed concerns related to falling numbers of migrants in their area and migration-related challenges they face. Specific issues mentioned by local councils were:

the need to sustain current levels of immigration into the area or increase it in order to sustain the population and local economy

falling numbers of migrant workers in key sectors, such as care work or farming (specifically following the Brexit vote)

lack of knowledge about local migrant communities and difficulties with engaging (with) migrant communities

isolation of migrant communities from the wider community (especially in rural areas) and lack of opportunities for mixing

following Health and Safety requirements in certain workplaces which employ a predominantly migrant workforce (e.g. farms, factories)

negative attitudes among some sections of the local communities towards migrants.

Employers in turn mainly raised concerns around:

falling numbers of migrant workers and/or difficulties with recruitment following the Brexit vote (partly as a result of the falling value of the pound) and concerns about sourcing labour in the future

the rise of negative attitudes towards migrant workers, especially following the Brexit vote

the language barrier and issues with communication in the workplace in the case of workers with little English

lack of housing in their local area as a barrier to permanent employment.

Third sector organisations and academics raised the following issues in relation to migration:

non-mixing of migrant and local populations exacerbated by the nature of funding which typically supports projects focused on particular groups (e.g. refugees, asylum seekers, Poles etc.) which may work against their wider integration

lack of a community-building strategy, lack of spaces and opportunities for different populations to meet and mix

strained community relations and negative attitudes towards immigrants, especially in areas of high social deprivation and following the Brexit vote

patchy and highly localised support for migrants both in terms of accessing services and integration projects

poverty among certain groups of migrants.

Looking at the concerns raised across the different parties, the most common ones related to:

the high degree of isolation among migrant communities

lack of social integration between migrants and the wider community, and

negative attitudes towards immigrants, especially among the more deprived sections of society.

Political climate and its role in shaping attitudes towards migrants

The significance of the positive political climate around migration was repeatedly mentioned throughout the research, both by ‘ordinary’ members of society (migrants and non-migrants) and by members of various organisations and institutions. Its impact was felt in two main areas: support structures for migrants and shaping positive attitudes.

Third sector organisations and academics underlined that, although it still may not be sufficient, there is much more institutional and organisational support available for international migrants in Scotland than in other parts of the UK. This was seen as highly positive not only for the recipients themselves but also for raising awareness of other populations living in Scotland and creating a positive climate around immigration. The availability of support was seen as a powerful political statement of Scotland's willingness to embrace migration.

In general it was underlined that the political rhetoric around immigration plays a crucial role in shaping attitudes towards migration. Its impact was seen as straightforward; a positive rhetoric helps shape positive attitudes towards migrants, while a negative rhetoric leads to more negative attitudes. Many study participants mentioned the powerful role of the media in creating a certain picture of immigration which then impacts directly on societal attitudes. Migrants repeatedly mentioned how they struggled with the negative rhetoric of the UK Government and the British media around immigration. These views were then taken on by the general public and had a huge impact on the migrants. The same view was reiterated by members of the native population:

But the mainstream media as well, they [the older generation] don't have Twitter to back up independent sources and stuff like that, there's a lot of bias in the mainstream media, and if you just watch say the BBC News and read the Daily Mail all the time, then you're only going to have one perspective, you know.

Local resident, rural area

Sometimes the people with those [racist and anti-immigration] views are the ones that buy into the mainstream media, the Daily Mail, oh look, immigrants are going to come over and murder you in your bed. Maybe if the media was less biased and put forward a more open viewpoint, then it would be more accepted.

Local resident, rural area

On the other hand, the positive rhetoric of the Scottish Government was very much appreciated. Migrants and non-migrants alike remarked that a positive political message cascades downwards and is absolutely key for creating a positive climate around migration. This was of special importance following the Brexit vote which had a huge impact on EU (and other) migrants living in the UK in particular. After the vote, many EU migrants who had built their lives in Britain felt they had suddenly lost ground; not only had their legal premise for living in the UK suddenly become uncertain and questioned, but they also felt unwelcome and not wanted in the country any more. Under these circumstances, the fact that the majority of the Scottish population had voted to remain in the EU, and the reassuring messages issued by the Scottish Government were of great importance to EU residents:

I know the Scottish Government very strongly has reassured us [EU citizens about being welcome here following the Brexit vote] and that's the only small reason I'm happy to be in Scotland right now. If my business would be in England and Wales and I wouldn't have had that support from the local government which I have here I would already quit running the business.

Business owner (tourism) and migrant, rural area

Therefore, the work that the Scottish Government puts into getting across the message that migrants are welcome in Scotland is very much appreciated by all migrants, not only EU citizens, and this was mentioned many times in the discussions. It was also underlined, however, that although crucial for creating a positive climate for migration, political messages per se are not sufficient and need to be followed by other actions on the ground:

What has been happening in England after the EU referendum has been appalling and this is Scotland's chance to promote itself as a more welcoming country. Providing that this is really the case. Reality has to follow. Govanhill, Maryhill [which are areas of high ethnic diversity in Glasgow] may be similar to down south. Let's not kid ourselves that Scotland is that different.

Expert (third sector), city

Finally, it is important to mention that while the Scottish Government's positive standpoint on migration is clear, the policy rationale behind supporting migration is not getting through to the public. Leaving experts and stakeholders (academics, third sector, council officers) aside, the general public is simply not aware of why Scotland needs migration. This is true for the Scottish population and migrants alike. The ‘ordinary’ participants of the study had not heard about the need for Scotland to grow its population through migration. Though the Scottish/British participants of the study were generally accepting of the higher levels of migration to Scotland in recent years, they did not necessarily support maintaining or increasing these – with the exclusion of employers. Employers were generally supportive of the idea because from a business point of view there is a need to fill vacancies in their (unpopular with the native population) sectors. The general population was far less positive about continued or increased migration. For example, when asked whether Scotland needs more immigration the local residents – who, overall, were supportive of migration in the discussion up to that point – said:

The way things are right now, I'll always see myself being accepting of that…not having a problem with it [immigration] at all. I think it's a good thing, I'm pro for that, but I don't think (…) it absolutely needs to be pushed even further. (…) I would like to see us take like a step back, like I don't want us to keep continuing to be as diverse as what we are.

Local resident, rural area

Don't want like Brexit to like bring us backwards, like it will, but like too much [immigration], don't want it to happen.

Local resident, rural area

The general public does not seem to realise that in-migration is necessary to maintain Scotland's demographic and economic growth; instead, what is noticed is the lack of jobs for highly skilled people across Scotland; the lack of educational and job opportunities for young people in rural areas; the lack of workers in certain sectors. Therefore, in order to build on the generally positive public attitudes towards migration, a campaign to raise awareness of why Scotland needs immigration should follow.i

Summary

Scotland is seen to have a generally welcoming attitude towards migrants yet this is not always the case, with racism and xenophobia being a particular issue in areas of high social deprivation. Moreover, while Scotland needs migration to grow its population and be able to sustain its economy, the general public is not aware of this argument. Furthermore, the established population has many concerns around immigration which are not being addressed and it does not necessarily support sustaining high levels of migration into Scotland. A positive political climate around immigration is seen as crucial for shaping positive attitudes towards migrants within the society and the efforts of the Scottish Government in this respect are widely acknowledged. On the ground, actions need to follow the political rhetoric. One of the key concerns voiced was that established and migrant populations in Scotland often live very separate lives from the general population, and there are few opportunities to mix and get to know one another.

Does Scotland need a social integration strategy?

As mentioned in the previous section, isolation of some migrant communities and lack of integration with the wider society were raised as specific areas of concern by third sector organisations, academics and local councils, but also by established members of local communities and in some cases, employers. So, what are the key factors which contribute to isolation and inhibit integration? In our discussions, all the different participants were asked what factors might impede (and facilitate) integration.

A number of factors which act as barriers to establishing links with the wider society had been identified, namely:

linguistic: poor knowledge of English and barriers to learning the language (such as difficulty with accessing language courses due to work or family commitments or transport issues; lack of suitable provision)

legal: limited rights (e.g. asylum seekers are not permitted to work)

political and economic: e.g. rupture of feeling of belonging among settled EU citizens following the Brexit vote, rise in hostility towards migrants following Brexit or the economic downturn

work-related: for those who are in employment – long work hours, shift work, working overtime, segregated workplaces, employer-tied accommodation (e.g. on farms); for those who cannot access the labour market – lack of opportunities to meet other people and learn English (this relates especially to asylum seekers and refugees but also e.g. to young mothers or single parents)

socio-cultural: closed nature of given local or migrant communities – cliquiness, small town/village mentality; cultural and religious differences, feeling intimidated; different cultural codes that both migrants and members of the receiving society are unaware of

personal: age – older migrants find it more difficult to acquire the language and establish relationships with locals; family circumstances – e.g. young mothers with poor knowledge of English can easily become isolated); personal preferences - lack of willingness and/or need to establish wider contacts

lack of free and accessible public spaces which would provide opportunities for establishing contacts and natural social blending; and a culture of being indoors (as opposed to countries with warm climates where more time is spent communally outdoors)

formal support structures: lack of institutional support for wider integration; on the other hand, in some cases too much targeted support which prevents people from becoming independent, from having to reach beyond their own communities and find their own feet

informal support structures: living and/or working in tight-knit networks of family and friends which leads to the creation of isolated and closed communities.

There are, therefore, a number of barriers to social integration that newcomers need to overcome. Migrants who have entered into intimate relationships with members of the receiving society are best placed in this respect as they enter their Scottish/British partner's social networks and develop social ties with local people naturally. All other migrants, however, find it much more difficult to develop such ties. Significantly, this relates to the migrants across the board rather than the most disadvantaged ones. Even migrants of high human capital (e.g. professionals with an excellent knowledge of English) mentioned difficulties with establishing closer links with natives. On the other hand, the same difficulties were mentioned by members of the established communities, some of whom remarked that they would not really know how to go about reaching out to newcomers:

I found any people from…well, from any other culture, I've always found very, very friendly when you managed to speak, but they don't engage easily, they don't…again I think that might be a cultural thing, they've been brought up not to look people in the eye, not to make contact, not to smile at strangers and this can be a bit off-putting for us, because it's opposite to what we would do, so we assume that we're not welcome, but in fact once you get over the barrier… But then in the supermarket or in the street, you're not going to get over that barrier, you pass them.

Local resident, rural area

Therefore, the lack of ties and opportunities to get to know one another creates a sense of separation between ‘us’ and ‘them’ which is also felt within the local communities. Migrants, even those who have been in Scotland for a number of years, are often perceived as just that: migrants or migrant workers – rather than new members of the Scottish society. This becomes especially visible when discussing entitlements. The migrant population is generally seen as less deserving (or non-deserving) compared to the native population:

I think in terms of [the integration strategy] actually being like an official framework, I think a lot of the reasons people would question that is obviously that would be government money, and we hear nothing else apart from cuts that our government are making to our own people. (…) That is an issue right now, and it's an issue everyone's aware of, and I'd like our own people, like our national people to be looked after as well, and I know that there's gaps there at the moment.

Local resident, rural area

On the one hand, this is a sign of clear ‘othering’ and not seeing settled migrants as full members of Scottish society. It also points to the need for community building, for building bridges between the old and new members of Scottish society and for providing a clear message that whether new or old, all members of society are of equal value. On the other hand, it is also an indication that if Scottish policymakers decided to develop a social integration strategy, careful thought would have to be given as to how such a strategy could be introduced in a way that would be accepted by society at large. Nevertheless, there is a need for creating a future vision for Scotland and for Scottish society:

I think to move forward with it [supporting immigration to Scotland] we need some form of integration just to get everyone to buy into it. We don't want it to be a burden in 5 years, 10 years’ time that there comes friction between the locals and the not so locals. So yeah, if there was an integration policy, it would soon become the norm, you know, the next generation would adopt it quite easily and it would be second nature to them. They'd just think it's all part of Scotland welcoming anyone for the greater good, you know.

Employer (agriculture), rural area

In the above quoted employer's opinion, Scotland needs a clear vision presented at policy level which would set the tone for the whole of Scottish society and community relations within it. This point was also reiterated by other study participants, academics and third sector organisations in particular, and we shall return to it in the later sections of this report.

As pointed out, many communities in Scotland live rather separate lives and the native population generally does not perceive them as part of Scottish society. If community relations continue to develop this way, it may lead to the growing separation of different communities, marginalisation of some and rise in tensions in the future. Therefore, introducing a social integration strategy focused on fostering positive community relationships might be a way of addressing these issues.

Aims of a social integration strategy: creating a vision for Scotland

The starting point of this research was to scope opinion on the idea of introducing a social integration strategy encompassing all migrants in Scotland, both the recently arrived and those who have been living in the country for a longer period of time. Details of the strategy were not set out, but the study participants were asked what it should involve. One of the general points raised by the experts taking part in the study was that before we can discuss the contents of such a strategy, we would need to define its exact aims.

In the discussions, the following overarching aims were suggested:

to create a vision for Scotland and for Scottish society which would be based on the principles of equality and inclusiveness

to normalise (ethnic and racial) difference in Scotland and support the native population in understanding and accepting change

to support community building and to create stronger and more integrated communities.

It was repeatedly underlined that a social integration strategy for migrants, though needed, should not be designed or advertised as a strategy focusing on migrants in particular. Rather, it should be mainstreamed and its activities should cut across all sections of society. There was concern that a strategy defined as an integration strategy for migrants might actually work against their integration for two reasons: firstly, public spending for it would not be supported by the native population, and secondly, it would by definition ‘other’ those who are already seen as different rather than part of Scottish society. Therefore, it was posited that a social integration strategy for migrants should in fact focus on wider community building and inclusion. As a member of the local community in a rural area observed:

It's an opportunity as well, instead of focusing a strategy just purely on immigration, open it up, look at the social issues, include immigration in the social issues, because isolation's a big factor, the way communities are set out is a big factor, and it's not specifically about where people have come from. If we're going to integrate everybody, let's do everybody.

Local resident, rural area

At the same time, it was understood that migrants face particular obstacles to inclusion and need some targeted support, such as language classes or interpretation services. Nevertheless, study participants agreed that this should be part of a wider strategy of inclusion within which the needs of particular groups are addressed. As one of the participants put it:

In every facet of social and public policy life, it's to try to normalise the fact that there will be people from a range of different backgrounds around.

Expert (third sector), city

Summing up, while a social integration strategy covering all migrants in Scotland would be beneficial, it should not be designed or advertised as such. Strengthening communities should be at its heart and hence it needs to be mainstreamed and encompass the whole society instead of particular groups within it. Indeed, this vision ties in with the notion of integration as a two-way process involving migrants and the receiving society alike. It requires a shift in thinking at both policy and community level, yet if Scotland is aiming to become a country of immigration, this needs to be supported through creating and implementing a new vision for the Scottish society:

Start with that, what kind of society are we aiming at for Scotland? Which has to be encouraged in a way that people will see, they want to, need to buy into, and then the next step down from that is what role does integration or migration play in that? (…) And then there's the steps to what we need to do about it.

Expert (academia), city

What approach should a social integration strategy for Scotland take?

As explained in the previous section, the experts taking part in the research underlined that an integration strategy for migrants should be mainstreamed and become part of a broader community building/inclusion strategy which would encompass all sections of society. This view was also shared by the migrant participants who reiterated the point that they would not like to be singled out as a particular target group of a strategy, or of funding, as this does not promote ‘real integration’. There was also general agreement that the aims of the strategy need to be strongly supported and clearly communicated at the highest levels of policy in Scotland. Participants believed that it is the Scottish Government that sets the tone for societal relations and has the most power in shaping attitudes. However, in terms of the details of the policy, there was much more differentiation in views.

In this section we discuss participants’ opinions on what an integration strategy for Scotland should look like: what kind of framework it should provide, what it should include and who should be responsible for its delivery.

A framework for integration

Participants had different opinions on the framework for an integration strategy; whether it should be a standardised policy designed at national level or a set of guidelines that can be flexibly adapted at local level, or a mixture of both.

Local councils were least supportive of the idea of a national-level strategy for integration. The reasons for this were:

there already is a number of national strategies councils need to implement while resources are strained

each local area is different and deals with different populations, hence the need for localised strategies rather than a national-level one

councils believed that they are already working towards integration; sharing good practice might be a more effective way of working than trying to implement a national-level policy.

Therefore, council officers were of the view that an integration strategy should provide a framework which would consider local differences, rather than be prescriptive:

It depends what you mean by strategy? (…) I think a strategy that provides a bit of leadership and direction and learning and help, yes. Strategy that imposes forms of provision which may not be right locally and very probably unaffordable unless they're fully and permanently funded is not going to be welcome. (…) So there's the thing about resources and there's a thing about not trying to design solutions from the centre that need to be bottom up solutions, but trying to guide and facilitate them.

Council officer, rural area

Similarly, academics and third sector organisations were sceptical of the idea of a prescriptive national-level policy for two main reasons: firstly, migrant populations differ and have different needs which may also vary locally, and secondly, any national-level strategy would require a stable stream of funding. The latter issue was raised especially by third sector organisations which felt they were carrying out essential work in this respect (that public bodies were failing to do) but were not adequately supported and were constantly struggling with finding funds for delivering projects.

Thus, the idea of a national-level integration strategy which would be overly prescriptive, require (rather than provide) additional resources and limit flexibility to implement solutions adequate to locally specific needs, was not broadly supported. In contrast, the idea of a framework for integration which would provide guidance as well as flexibility, both for the migrants themselves and for those delivering it, was supported:

Because everybody has such a complex and individual and diverse need when they arrive in a place there has to be lots of different tiers to what is on offer. But the framework I think is equally as important in terms of it's an enabler for everybody, and it relates to a human process of being together and living together in a space, rather than something which is just something that migrants have to do.

Expert (academia), city

Significantly, however, there are certain areas where a national-level standard would be seen as beneficial and would be welcome. These were:

in policy and the media: communicating an inclusive vision for Scotland and for Scottish society; creating a positive discourse around migration, normalising diversity, underlining its benefits; also – more inclusion of people of a migrant background in policy and media, more visibility in public life

in education: creating a curriculum for and clear policies with regards to EAL (English as an Additional Language) and ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) at primary and secondary school level; standardising school policies with regards to EAL; including diversity programmes in early years education and the general curriculum; including diversity training in teacher training programmes; introduce a framework for recognition of foreign qualifications; introduce a curriculum for ESOL literacies

in public service delivery: introduce diversity training for frontline staff to enable them to deal with people from various populations

a reception policy for new arrivals.

Participants underlined the crucial role of policymakers, the media, and educational establishments in creating a welcoming attitude towards migrants. A combination of the three would ensure promoting the vision of an inclusive Scotland at two different levels; the national (policymakers and the media), and the local (educational establishments). A reception policy for new arrivals, in turn, would create a welcoming environment from the very beginning of the migration experience.

What should an integration strategy consist of?

There are many elements that may come into an integration strategy at different levels: national and local. The study participants provided a variety of ideas for what should be included in an integration strategy and a synthesis of these is presented in this section.

At national level, an integration policy could include:

an inclusive vision for Scotland communicated through policy discourse and the media and supported by an education campaigni

a reception strategy for new arrivals to Scotland

standardised policies in schools with relation to integrating newcomer children

a national curriculum for teaching EAL and ESOL in schools

diversity teaching as part of the general curriculum

diversity training as part of teacher training

a framework for the recognition of foreign qualificationsii

diversity training for frontline staff in the public sector

creating a national diversity training resource for people who want to find out how to communicate with people who have little English etc.

creating a labour inspectorate with responsibility for enforcing compliance with employment and equality law[1]

a strategy for celebrating other cultures e.g. by introducing a ‘Cultures of Scotland Day’

a ‘pathways into employment’ programme.

At local level, an integration strategy could include:

establishing a chain of one stop shops for newcomers (both from other countries and other parts of the UK) which would provide comprehensive information about the local area, resources, services etc. and hands on advice and support (currently people are referred to many different sources of information and are being sent from one service to another)

creating forums for local partnership working and broad sharing of information between institutions and organisations (e.g. between local councils and local doctors’ surgeries so that English language courses could be advertised through surgeries); supporting collaboration between local councils and third sector organisations so that local resources can be fully used

providing free, accessible and friendly spaces for people (individuals as well as organisations) to meet and mix; this could be in the form of local community hubs which would run various initiatives, e.g. interest groups, befriending programmes, informal language learning, language exchange, volunteering, employment support, community conversations (aimed at learning from the community about their problems and concerns, but also needs)

combining formal language provision with informal opportunities to practice the language; ensuring accessibility and quality of local language provision

promoting inclusion of people of a migrant background into local policymaking.

Some participants also spoke about migrants’ rights and responsibilities, for example, that there should be a requirement to learn English within a certain period of time in order to have access to certain provisions. Nevertheless, this idea was not broadly supported and various issues with introducing such a requirement were raised. For instance, it was argued that this would put some migrants at a disadvantage as people come from various cultural and educational backgrounds and have a different pace of learning. Therefore, it is likely that the most disadvantaged migrants in this respect (e.g. refugees from Arabic countries who are illiterate in their own language) would struggle to fulfil such a requirement. Study participants were rather of the view that integration needs to be promoted as a process of opportunity and empowerment in order to achieve one's full potential rather than in terms of compulsion.

Case Study - forums as a model for partnership working

[T]o really work, this is just an example that was in place 14 years ago, was an Edinburgh Refugee Forum, (…) it was a multi-agency forum, it met every six to eight weeks. It had a councillor. (…). And it was a think tank, it was an action group. It always worked with the current agencies that provided housing, health, the police, immigration, children's organisations, schools. And if there was a particular issue, (…) it could be travel cost to college, it could be issues within schools, it could be hate crime. By having a regular forum meeting and exchanging and sharing ideas, looking at ways to improve things, they would then create working parties. And often that was quite a very effective way of getting things done at a small scale.

Jon Busby (expert, third sector)

For the last few years I've worked closely with the Holistic Integration Service, which was a Scottish Refugee Council led partnership with language providers, from further education, third sector and employment support. So a kind of mixture (…). And they operated as a community of practice. And what I really saw developing through that [were] these relationships that people built up, and people understanding why their language clients were suddenly not turning up. Well, it was because they had an appointment at the housing [office of the Council]. (…) But if they didn't turn up at the language [course] they then got sanctioned by the DWP. So it was creating a space where there could be joined up thinking. And again, I don't see that as refugee specific at all. I think that community of practice would be so valuable for the migration issues generally.

Alison Strang (expert, academia)

Reception strategy

A reception strategy, mentioned as one of the elements to be included in national-level policies for integration, was a separate discussion question. Study participants were asked whether a reception policy would be beneficial and what it should consist of. There was broad agreement that such a strategy would be very useful. In practical terms, it would provide newcomers with essential information; in emotional terms, it would make them feel taken care of and welcome. While the latter might seem insignificant, the importance of initial welcome (or the opposite) for the overall settlement experience cannot be overstated, and this was mentioned by people of a migrant background and third sector organisations alike:

[I]t is that the first impressions, if you actually arrive in a place and you for instance meet people who are supporting [you], who direct you to where you can find some language classes, who want to hang out with you, kind of show you around, then it really creates the impression that yes, this place is welcoming.

Expert (third sector) and migrant, city

I totally agree (…), my work would suggest that these little chance encounter type things have a disproportionate influence on people in terms of their perceptions of the level of welcome. And of course then that has a knock-on effect to how you behave and how much risk taking you're willing to do, which they can build on there.

Expert (academia), city

The aim of a reception strategy would be to provide essential information about Scotland and the newcomers’ local area and provide initial advice and support.

Participants had the following suggestions for what a reception strategy should include:

a welcome pack

an advice and support service

peer mentoring/a local buddy scheme.

The welcome pack was envisaged as a source of basic information about Scotland, its institutions (and especially the education system which newcomers to Scotland find very difficult to understand and navigate), available services, as well as local information. The information would need to be provided in English and other languages. In this case, in order to familiarise non-English speakers with the language and terms used, text in English and text in the other language should be provided side by side. The welcome pack should be available both in print and online, as people have different preferences and different access to resources (some newcomers might not have regular access to the internet). The student discussion group came up with a more creative idea for getting basic information across, namely developing a special app for the purpose:

If you have small videos, how to get da-da-da. And then someone just explaining to you, people acting even. That would be so, so smart. And people who are planning to come, they will have access to these materials beforehand. So they will come here expecting what to see and find. That will make many lives easier. And it would be so easy to access. So you're in the city centre, you need to know whatever, you've just arrived, and then you just access the app and then you get information right now. Great idea.

International student, city

Council officers who took part in the study mentioned that, in some local councils’, welcome packs had been produced and distributed a few years ago, following the sudden increase in migration from Eastern Europe, but their uptake and usefulness was not known. Some councils spoke about preparing customised welcome packs more recently for the Syrian families who were moving into their area. These were found to be useful, but the officers had received detailed information about the families in advance and hence were able to prepare information relevant to them specifically, which would not be possible with other migrant groups. Therefore, welcome packs would need to be carefully designed, preferably in collaboration with recent migrants so that information seen as useful would be provided. Moreover, information about the availability of the welcome pack (or the welcome pack itself) would need to be distributed widely. It was emphasized that council offices might not be the best place in this respect as many people never go to them; in contrast, workplaces, doctors’ surgeries, supermarkets and job centres were mentioned. One council officer mentioned that their council currently had a general welcome pack on their website, but this was not widely advertised and people would need to know about it to find it. Also, its use was not being monitored. Therefore, if the welcome pack was to support newcomers, it would need to be both carefully designed and widely advertised.

Another idea that was suggested was appointing advice officers within local council structures and/or in a community hub where information on first steps would be available (e.g. how to set up a bank account, how to find a flat). This ties in with the idea of one stop shops and community hubs mentioned in the previous section:

Mention to everyone who's coming in that there is somebody you can contact, free of charge, for any support, this is the office, this is the number 24/7, seven days a week, it's accessible. Because again, if you're going to make it nine to five, which is standard in Britain, that's when everybody's at work, and if you came here for work you're working, you don't have time to call, and you're stressing about it. So I think that would be a much more useful resource which could be well received. An easy to find contactable person with the relevant information.

Business owner (tourism) and migrant, rural area

Finally, the idea of peer mentoring/local buddies was put forward. These could be local people – either from the native or migrant population – who would be willing to show a newcomer around their area, show them where local services are, help them get to know the local culture etc. There are a number of buddy schemes run across Scotland and these have been found to be highly efficient and well received by both the buddy volunteers and their ‘mentees’. One of the student participants described a similar scheme she had come across abroad, ran through an educational establishment:

I was in Japan, they had an interesting system for foreigners. So for example, they have one day when there were some locals who brought you to, I don't know, to the health place or to the bank, and they did things together with you. They were volunteers, but I think they got some credits from the university because they were students as well. So they had specific days for that, maybe it would be useful here.

International student, city

This last example demonstrates that, while some of the proposed elements of a reception (and integration) strategy are resource heavy, others are based on the principle of volunteering and require setting up and management, but little other resource.

What policies and experiences can we build on in devising a social integration strategy for Scotland?

The experts and stakeholders taking part in the study (academics, third sector, council officers) were asked what existing and past policies, strategies and experiences would be worth considering when devising an integration strategy for Scotland.

In terms of past policies and strategies in Scotland from which there are valuable lessons to be learnt, the following were mentioned:

the One Scotland, Many Cultures campaign (2002-2007);

the Fresh Talent Initiative (FTI) (2004-2008);

the Relocation Advisory Service (RAS) which supported the FTI (2004-2008).

One Scotland, Many Cultures was a media campaign aimed at raising awareness of and tackling racism in Scotland. The FTI introduced a post-study work visa scheme allowing international students to stay in Scotland for up to two years after they had completed their course. It established the Relocation Advisory Service, an advice centre for those interested in moving to or staying on in Scotland; and activities targeted at particular groups, especially international students from non-EU countries. Formal evaluations of the first three initiatives enumerated above have been carried out and may be learnt from.i However, it might be beneficial to carry out further research into these, possibly of a more qualitative nature, in order to be able to fully evaluate their strong and weak points and impact. For example, while formal evaluations of the One Scotland, Many Cultures campaign were rather positive, the study participants who mentioned it did not feel the campaign itself had significant impact on changing attitudes. They felt that in order to ensure longer-lasting effects, the campaign should have been supported by local-level initiatives. There were also mixed opinions on the RAS, despite its rather positive formal evaluation:1

[I]f you look at some of the things before, the Scottish Government did have a hub, (…) people could phone up and ask about information when they were making these decisions to come to the UK and Scotland. Scotland spent about £10,000,000 in asylum and immigration advice, that could be used better, focused on…could be providing things in different ways.

Expert (third sector), city

Therefore, it might be useful to consult further on these past initiatives when drawing lessons from these.

Experts and stakeholders also discussed a number of currently operating policies and strategies, in Scotland, the UK and beyond that could be built on or learnt from when designing a wider integration strategy, namely:

the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 and Public Sector Equality Duty

the New Scots Integration Strategy

EAL (English as an Additional Language) policies in schools in England and Wales

current funding landscape and its impact on integration

policies which normalise ‘difference’ and foster acceptance, e.g. the LGBT policy

language policies with regards to teaching modern languages in Scottish schools and bilingualism

policies in other European countries, e.g. pathways to employment.

The Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 and Public Sector Equality Duty were pointed to as already providing a policy framework which could support wider migrant integration. The Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 places a duty on Community Planning Partnerships (CPPs) to support community bodies in participating in the design and review of local plans. It provides scope for migrant organisations to get involved. Furthermore, ‘tackling inequalities’ should be a specific focus for CPPs, and this provides further scope for taking action in support of wider societal integration. The Public Sector Equality Duty requires public bodies to have due regard to the need to eliminate discrimination, advance equality of opportunity and foster good relations between different people when carrying out their activities. Fostering good relations within communities is thus already part of Scottish public policy and provides a legal framework for integration and community building initiatives at local authority level.

The New Scots Integration Strategy provides a wealth of experience to learn from. As mentioned earlier, this is a holistic integration strategy aimed at refugees and asylum seekers in particular, which was introduced in Scotland in 2014. It is a holistic programme supporting integration in general and includes supporting refugees and asylum seekers in building social connections. Therefore, lessons of a more general nature, as well as specifically focused on the area of social integration, may be drawn from this strategy. Significantly, recent evaluations point to social connections as one area of the strategy which needs further work. A number of experts participating in our study were directly involved in the New Scots Integration Strategy and were keen to share learning from it. The development of close partnerships between different agencies was pinpointed as the main benefit of the strategy (see also case study on forums as a model for partnership working). Lack of standardisation of practices and learning from previous experience of settlement in Glasgow and Edinburgh was seen as its greatest weakness: