The Scottish Government's Five Year Financial Strategy

On 31 May 2018, the Scottish Government published Scotland's Fiscal Outlook: The Scottish Government's Five Year Financial Strategy. On the same day, the Scottish Fiscal Commission published its latest set of economic and fiscal forecasts. This briefing provides a summary and analysis of key elements of these reports.

Executive Summary

The Scottish Government published its first Five Year Financial Strategy on 31 May 2018. On the same day, the Scottish Fiscal Commission published its latest set of economic and fiscal forecasts for Scotland.

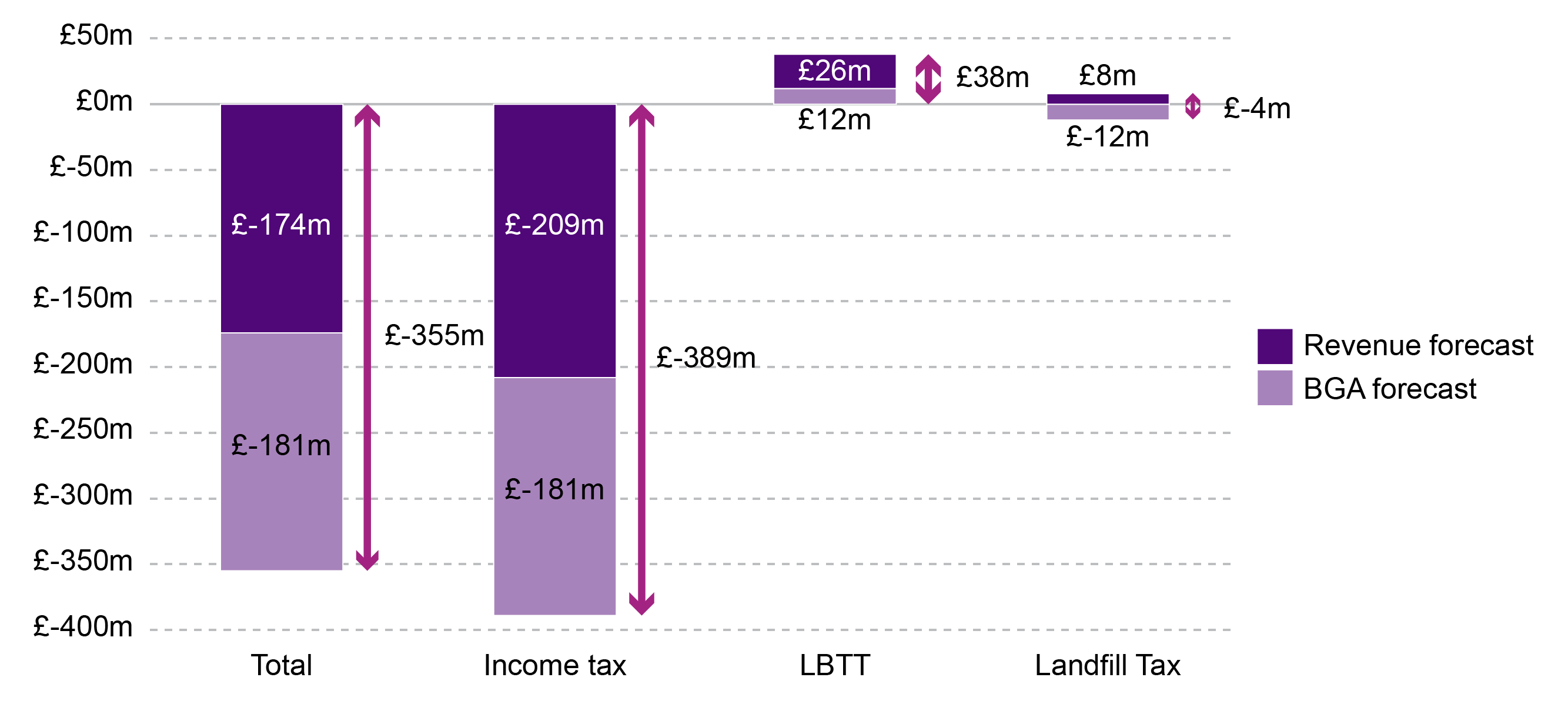

The SFC forecast that Scottish GDP growth will remain below 1% per annum through to 2023. On tax revenues they have made some revisions to the forecasts produced to inform the setting of the 2018-19 budget, most significantly to income tax revenues. Whilst not significant in percentage terms (-1.7%) the latest income tax forecasts represents a £209m downgrade on the numbers underpinning current year spend.

Coupled with the OBR's updated UK forecasts from March 2018, which had the effect of increasing the block grant adjustment by £181m, this points to the outlook for the Scottish budget worsening in two ways compared with the previous set of forecasts. Combined with changes to forecasts for other taxes, these new forecasts imply a net reduction of £355m compared with the Budget for 2018-19 set just a few months ago. Latest forecasts also point to a potential shortfall on the 2017-18 budget, with net revenue forecasts for that year down by £256m on the previous forecast.

Although this won't immediately impact on spending in 2018-19, which was locked in with the passage of the Budget Bill, it does point to a potential budget shortfall should these latest forecasts prove to be accurate.

The Fiscal Outlook document does not contain detailed budget allocations "at this stage" or detailed scenarios by portfolio. The document lists a series of already announced policy Budget priorities around Health, the Police, Early Learning and Childcare, Attainment and Higher Education.

The Scottish Government's Budget priority choices inevitably mean that other non-protected areas of spend must take up more of the slack from any future spending reductions. Under the range of scenarios provided by the Scottish Government, "other expenditure" will fall by between 1-16% in real terms over the period to 2022-23, with the bulk of reductions occurring in 2019-20 and 2020-21. Under the central scenario, "other expenditure" will fall as a share of the Budget from 44% in 2018-19 to 37% in 2022-23. The largest element by far of "other expenditure" is the non-early learning and childcare part of Local Government.

Other pending challenges around fulfilling other budget obligations and pressures, mean that ongoing budget management will be important in the coming years.

The Financial Strategy document follows a recommendation by the Budget Process Review Group that the Scottish Government takes a more medium to longer-term approach to financial planning. The Scottish Government acknowledges that the document will evolve over time. The briefing concludes with a summary of what the document contains, measured against the recommendations made by the Budget Process Review Group.

Whether the document sufficiently meets the expectations of the Budget Process Review Group recommendations for a medium term financial strategy has been and will be debated by Parliament in the coming months.

Context: The Medium Term Financial Strategy

On 31 May 2018, the Scottish Government published Scotland's Fiscal Outlook: The Scottish Government's Five Year Financial Strategy1.

Publication of this document follows a recommendation of the Budget Process Review Group (BPRG)2 that the Scottish Government takes a more medium to longer-term approach to financial planning.

The document was also envisaged by the BPRG as giving a focal point for parliamentary scrutiny of some of the medium term opportunities and challenges for the Scottish public finances.

The document is informed by the latest Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) forecasts3 for tax revenues, Social Security spending and economic growth, which are produced twice per year. These forecasts, along with other assumptions, underpin the Scottish Government’s projections for available resources in the coming years.

So what do these economic and fiscal forecasts say and what does this mean for the Scottish budgetary outlook? That is the subject of this briefing.

The Scottish Economic and Fiscal Forecast

Economic growth

The SFC forecast for Scottish GDP growth is broadly the same as it was in their last set of forecasts produced in December 2017.

The SFC envisage that Scottish growth will remain below 1% per annum for the forecast period through to 2023. This is below the overall GDP growth forecast for the UK produced by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). Scottish and UK official forecasts through to 2022 are presented in table 1.

| % growth | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scotland (SFC) | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| UK (OBR) | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

Tax revenue forecasts

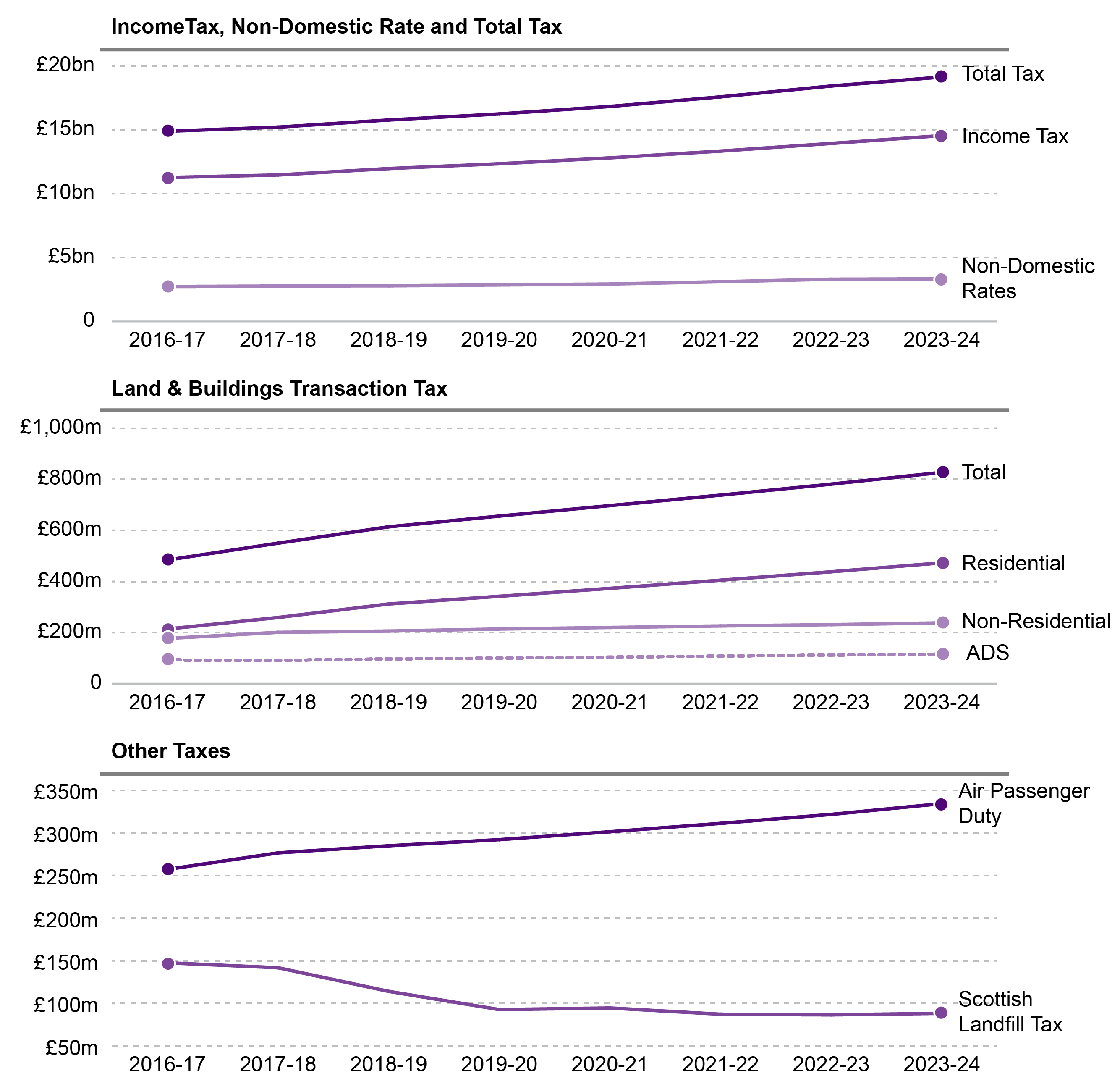

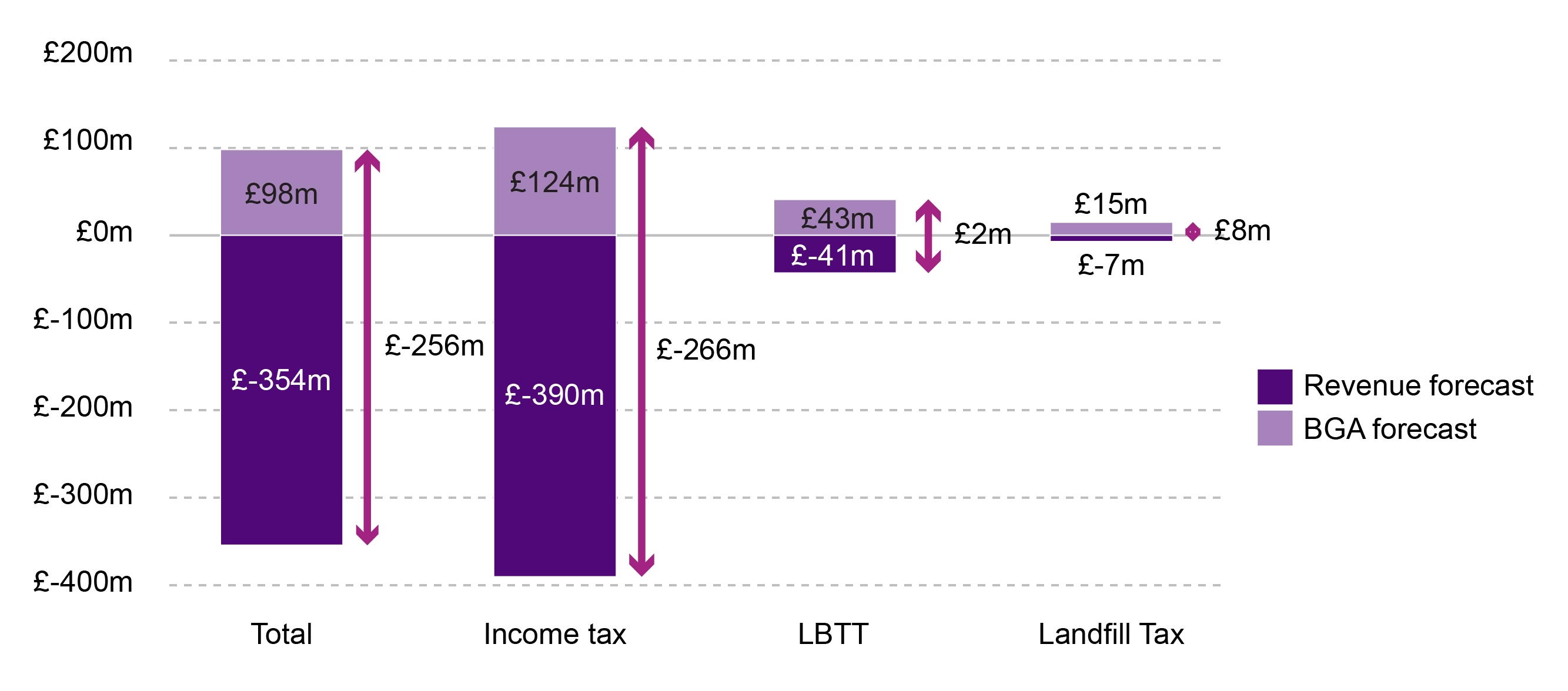

The SFC is responsible for producing five year forecasts for devolved, shared and assigned tax revenues. The latest forecasts are presented in the following figure.

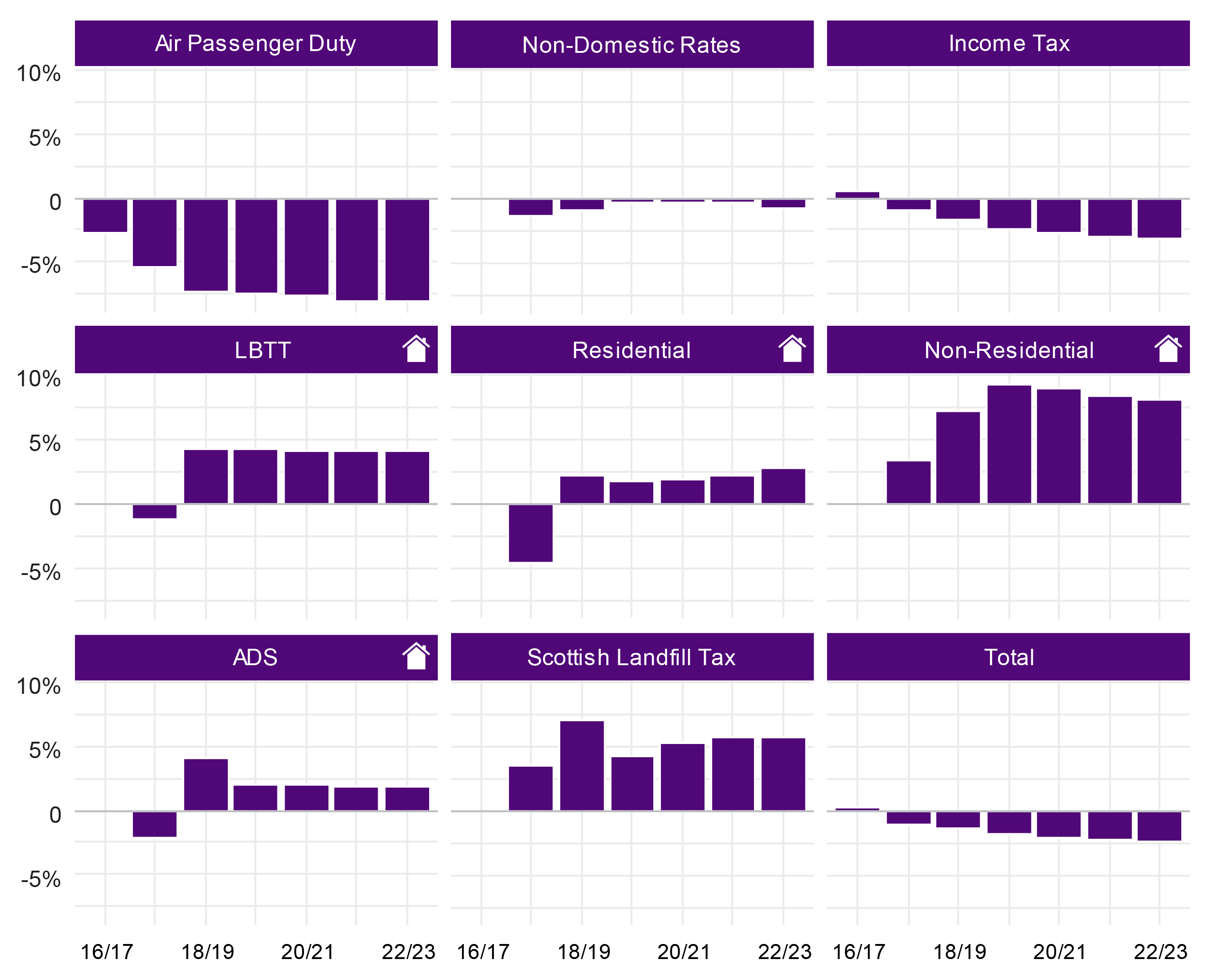

As will happen with economic and fiscal forecasts there have been a number of revisions to the previous SFC forecasts. Although, not significant in percentage terms, the largest in absolute revenue terms is the change in the income tax forecast, which is down by £117m in 2017-18, just over £200m in 2018-19 and just over £300m in 2019-20.

Forecasts for Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (LBTT) and Landfill Tax in 2018-19 are slightly higher than they were in December. The forecast for LBTT in the current year is up £26m (4.4%) and Landfill Tax is up £8m (7.5%). Non-Domestic rate forecasts are down in the current year by £24m (-0.8%) and in all other years of the forecasts.

Figure 2 presents the revisions in the latest SFC forecasts compared with their previous forecast by tax.

In its report on Draft Budget 2018-19, the Finance and Constitution Committee noted the following with regard to the impact of the SFC’s weak GDP growth outlook for tax revenues and the Scottish budget:

While it is not clear what the impact will be on income tax revenues there is nevertheless some risk to the public finances which will require close monitoring by both the Scottish Government and the SFC.1

The latest SFC forecasts highlight this risk as they adjust down the forecast for income tax relative to their most recent forecasts of February 2018 (which took account of tax changes agreed as part of the Budget negotiations).

For the current financial year, the SFC is forecasting £209m less in revenues from income tax compared to its previous forecast. The SFC say that this relates to lower than expected real wage growth. However, as the adviser to the Finance and Constitution said in a recent blog, there has also been a change in judgement about the impact of wage growth in the most recent forecast:

It is partly because of the emergence of some new data on wage growth in 2017 since the SFC’s last forecasts. However, only limited new data on earnings has emerged since December, and on the whole this new data is not the sort that you would expect the SFC to place a significant amount of weight on (Labour Force Survey data on wages is drawn from a fairly small sample of self-reported earnings, while Compensation of Employees measures are derived from regional accounts data).

But the downward revisions to wages are also due to an ‘evolution of judgement’ on the part of the SFC about the likely future path of earnings growth. This evolution of judgement by a detailed analysis, summarised in the SFC’s report, of recent trends in Scottish wage growth , and the relationship between productivity and wage growth on the one hand, and labour market slack (i.e. unemployment, inactivity), and wage growth on the other.2

Implications of changes to tax forecasts for the short term

Forecast are inevitably subject to change as new information comes to light. There was always a likelihood that the Scottish Government might end up having somewhat more, or somewhat less resource available to it than it thought when the budget was set.

It is important to note, however, that the latest SFC forecasts will not directly impact the Scottish budget for the current financial year. Scottish spending for 2018-19 was “locked in” when the Budget Bill was passed in February this year. Any actual impact will only be felt in future years, when actual revenues are known. The extent to which these differ from what was forecast will determine the extent of any future reconciliation and adjustment to budgets in future years. That is, if forecasts turn out to be unduly pessimistic or optimistic, future budgets will be adjusted upwards or downwards to reflect this.

The importance of the Block Grant Adjustment

Under the Fiscal Framework, equally important to the Scottish budget as the SFC revenue forecasts, is the block grant adjustment (BGA) made to the Scottish budget to reflect the revenues foregone by the UK government from the devolution of each tax (see also this blog from the Fraser of Allander Institute).

The BGA is linked to the growth rate of revenues in the “equivalent” taxes in the rest of the UK. If the BGA is also falling, then this has the potential to offset the falling revenues being forecast by the SFC.

However, when the OBR updated its UK forecasts in March this year for the Spring Budget, it raised its income tax forecast for the rest of the UK in 2018-19 compared to its previous forecast. This caused the BGA for income tax to increase by £181m.

Net potential impact of SFC and OBR forecasts

This means that the latest set of forecasts for Scottish revenues point to the outlook for the Scottish budget worsening in two ways compared with the previous set of forecasts. The SFC has revised down its income tax forecasts by £209m and the BGA has been revised up by £181m. This means that according to the latest set of income tax forecasts, the Budget could be £390m worse off than it was just a few months ago. This will be offset, however, by the LBTT and Landfill tax net revenue and BGA forecast position which is positive (see figure 3). Figure 3 shows that the net downward revisions to the revenue and BGA forecast position for 2018-19 is -£355m.

As mentioned above, this latest set of forecasts will not impact immediately on the Scottish budget. The forecasts that matter for 2018-19 spending are the ones made at the end of 2017 in the UK and Scottish Budgets. We will need to wait until fully audited outturn data is available for tax revenues raised in the current financial year (final audited income tax receipts will not be available until 2020, with reconciliation applied to the Budget for 2021-22) before we know the extent of any adjustments that will need to be made to budgets in future years.

Provisional outturn information for 2017-18 income tax revenues will be available later this year (final income tax outturn will not be available for 2017-18 until 2019, with reconciliation applied to the budget for 2020-21). We will then have an indication of the adjustment that might need to be made for forecast error from the 2017-18 Budget. As in 2018-19, the latest set of numbers point to a potential budget shortfall from forecast error at the setting of the 2017-18 Budget of £256m.

The latest set of forecasts are useful in indicating a 'direction of travel', and provide an early sense of the extent to which the forecast on which the 2017-18 and 2018-19 budgets were based might be revised, and in which direction. If accurate, the latest SFC forecasts suggest that the Scottish Government may need to plug a revenue shortfall in future years by reducing some areas of spend, increasing taxation, borrowing or accessing the Scotland Reserve (or some combination of these).

Implications of forecasts for the medium term

Chapter 6 of the Financial Strategy sets out a central, upper and lower scenario for the potential overall Scottish Budget. These scenarios, which include estimates for additional money being added to the budget for new social security powers, will see the Resource budget under the central scenario increase in real terms by 10% over the period to 2022-23. This real growth largely reflects the devolution of the new Social Security powers. The proportion of the Budget allocated under the central scenario to Social Security increases from 1% in 2018-19 to 11% in 2022-23, reflecting the devolution of new powers and Scottish Government priorities for using them. With Social Security excluded from the central scenario, the budget outlook through to 2022-23 falls slightly in real terms (-1% between 2018-19 and 2022-23).

The Scottish Government forecast that by 2022-23 the overall Budget will reach £36.7bn under its central scenario, within a likely range of between £35.5bn and £39.7bn. The report notes that "while this represents the most likely upper and lower range, there is a chance that the final budget will lie outside this range."

But how will the Government and Parliament choose to allocate this resource? One of the intentions of the Budget Process Review Group recommending the publication of a Medium Term Financial Strategy was to provide a focal point for subject committee scrutiny. The extent to which the document delivers on this intention has been the subject of some discussion in Parliament. In responding to the publication of the document on 31 May, Patrick Harvie stated:

Nobody would expect this five-year strategy document to lay out specific, precise commitments, budget line by budget line, for each of those years. A range of scenarios is set out in broad brush strokes for many subject areas—health, social security, the police, higher education, attainment and so on—but no such scenarios are given for local government.....

It does not set out the scenarios for what will happen to local government spending. Is that because local government is in line for deeper cuts over those five years?1

In Finance and Constitution questioning of the Cabinet Secretary on 6 June, Adam Tomkins asked:

one of the themes that runs through the budget process review group’s recommendations is that the Parliament’s subject committees need to play a greater role than they were previously able to play because of the very constrained timetable that was available for parliamentary scrutiny of the Scottish budget, for the reasons that you just outlined. What is there in the strategy document that is new, and which we did not previously know about, that will help the Parliament’s subject committees to scrutinise the Scottish Government’s budget?

.........how will the document help the Health and Sport Committee to scrutinise the medium-term financial stability of the NHS in Scotland? If you do not like that example, I could ask the same question about the committees that deal with education or policing and justice. How will the content of the medium-term financial strategy help to enhance effective parliamentary scrutiny of your Government’s budget proposals over the remainder of the parliamentary session? That is the bit of the puzzle that I think is missing.2

Whilst not attempting to answer these questions, the next section of this briefing provides some analysis that may assist subject committees in their thinking.

Budgetary commitments

The document does not contain detailed budget allocations “at this stage” or detailed scenarios by portfolio. The Cabinet Secretary in his statement to Parliament highlighted the challenge in doing so, but hinted that this may be possible following the UK Spending Review next year:

we do not currently have any resource budget allocation from the UK Government beyond 2019-20. It is hoped that the UK spending review next year will offer sufficient future year budget information to allow the Scottish Government to develop multiyear budget allocations.

The document lists a series of already announced policy Budget priorities around Health, the Police, Early Learning and Childcare, Attainment and Higher Education.

Health - where there is a commitment to increase resource spending on the NHS by £2bn over the course of this Parliament.

Police - where there is a commitment to protect the Resource Budget of the Scottish Police Authority (SPA) in real terms for the duration of the Parliamentary term.

Early Learning and Childcare - where there is a commitment to deliver 1,140 hours per year of early learning and childcare (ELC) provision.

Attainment - where there is a commitment to allocate £750m through the Attainment Scotland Fund over the course of the Parliamentary session, to tackle the attainment gap

Higher Education - where there are policy priorities to protect free tuition, provide an annual minimum income for the least well-off full-time Higher education students.

Outlook for non-protected parts of the Budget

The Scottish Government's choices around Budget priorities inevitably mean that other "non-protected" areas of expenditure must take up more of the slack from any spending reductions.

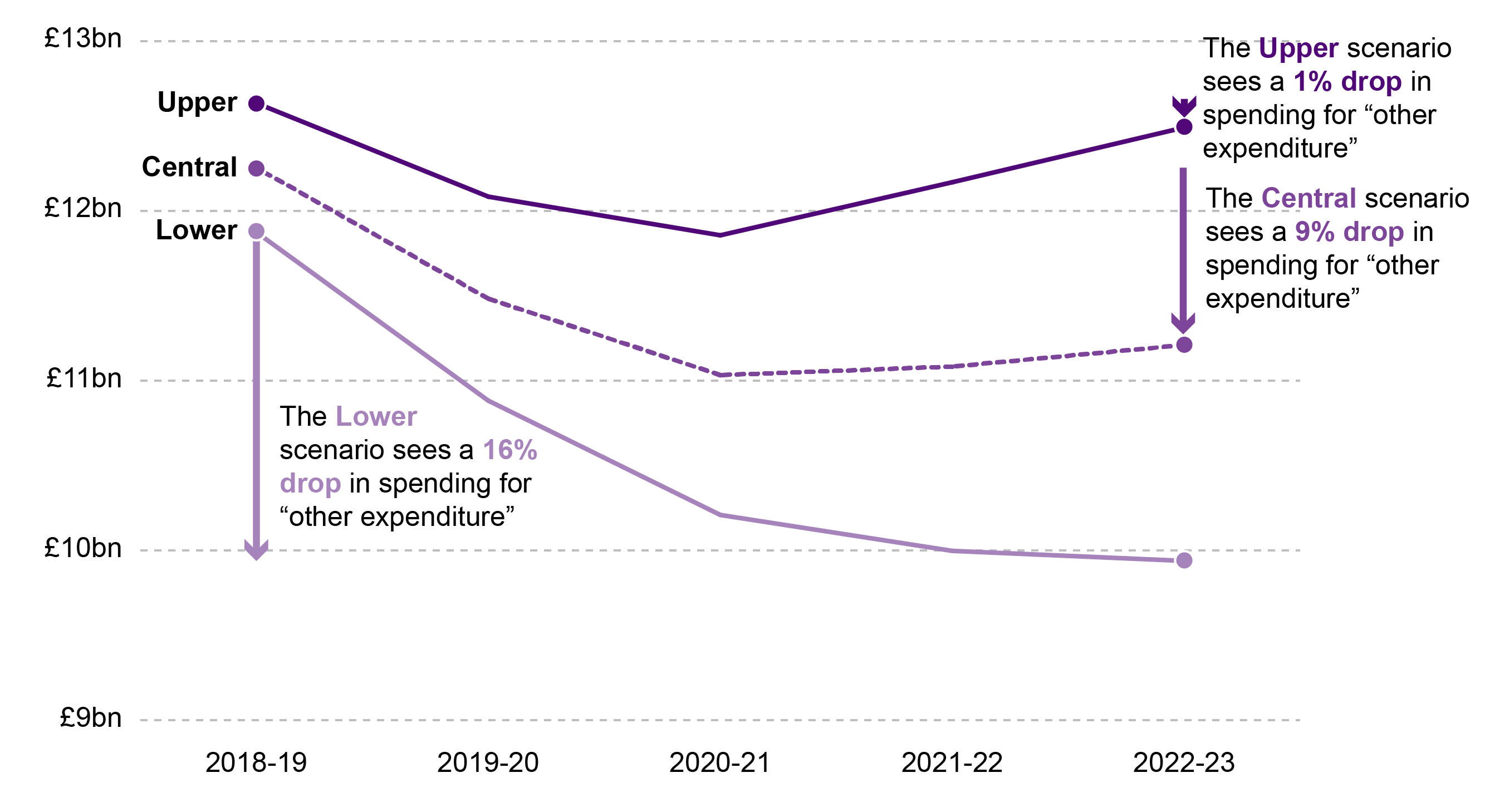

Using the upper, central and lower case scenarios as presented in chapter 7 of the Financial Strategy show that over the period to 2023, "other expenditure" will fall in real terms even in the best case scenario. Under the Central scenario, other expenditure will fall in real terms by £1bn (9%); in the upper scenario it will fall by £0.1bn or 1% and in the lower scenario it will fall in real terms by £1.9bn or 16%.

Figure 5 shows that the largest decline in real terms cuts in other expenditure occurs in 2019-20 and 2020-21.

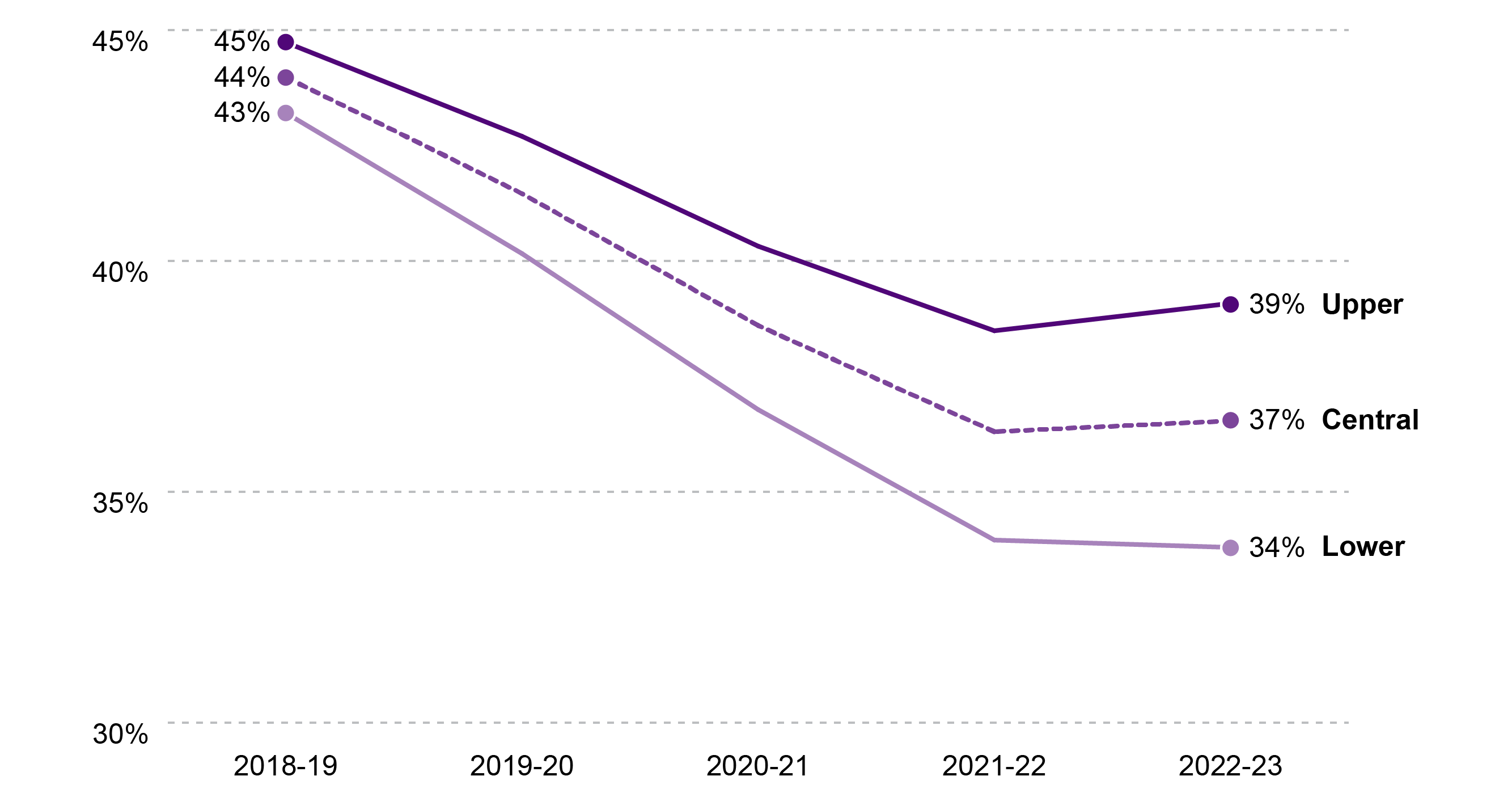

The priorities identified by the Financial Strategy mean that, under the central scenario, the "other expenditure" elements of the budget will fall from 44% in 2018-19 to 37% in 2022-23 (figure 6).

Other expenditure comprises all other parts of the budget outside the protected areas identified. These reductions will not be distributed evenly across non-protected areas, but the average reductions are significant. Many of the areas impacted are ones which have been dealing with falling real terms budgets over a number of years.

The largest element by far of ‘other’ spend is the non-early learning and childcare part of Local Government, but as the Financial Strategy document states, it includes other areas of spending right across government.

What this means for spending elsewhere.

In addition to these key areas of investment, there are of course a range of wider commitments across all Scottish Government portfolios that will need to be managed from within our available budget. This will include commitments on homelessness, child poverty, concessionary travel, free personal care, supporting the Scottish economy, establishment of the Scottish National Investment Bank, delivering on our climate change ambitions and continuing to deliver the range of public services that we have responsibility for. All of these will require a share of the overall resource budget funding that is available.

Budget Challenges

It is important to remember that there are other financial challenges on the horizon that must be managed within a finite spending envelope. For example, population ageing, whilst identified in the Financial Strategy as a welcome development, brings challenges around the provision of certain age-specific public services. Population ageing, coupled with a reducing pool of working age citizens paying taxes brings potential fiscal strains.

The Government's Financial Strategy identifies just some of the Government's budgetary commitments. Others are not difficult to find. Perhaps the most significant relates to public sector pay.

Pay pressures

Recent years have seen increasing pressures arising from higher inflation. The fall in the pound after Brexit has applied pressure on the costs of many goods and services. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) measure of inflation was 2.2% in April, down from 2.3% in March and down from the recent high of 2.8%.1 However, Brexit uncertainty at least presents the possibility that it may rise again in the future.

The implication of higher inflation is that it reduces the real terms value of a given level of cash spending - costs go up meaning the same level of spending buys less. It also means that the costs of certain Government priorities, for example protecting the SPA budget in real terms, becomes more expensive.

Another implication of rising inflation is that it increases the pressure on public sector pay, which is the largest call on the day-to-day spending of the Scottish budget.2 For 2018-19, the Scottish Government lifted the 1% pay cap on public sector pay, introducing a miminum 3 per cent increase for public sector workers earning £36,500 or less and a 2 per cent limit on the increase in the baseline paybill for those earning above £36,500 and less than £80,000. SPICe estimates that replication of the Scottish Government's pay policy across the whole Scottish public sector would cost approximately £400m.

Other commitments

The First Minister has also identified Education as the "defining mission" of her Government. With that in mind, it might be that the Scottish Government seeks to provide additional financial support for education outwith the Higher Education and Attainment Fund priorities mentioned above. Pressures on teachers' pay may also be a factor here.

Revenue financed capital investment obligations arise from ongoing public private partnership (PPP) projects in the form of Non-Profit Distributing (NPD) and Private Finance Initiative (PFI) legacy contracts. Revenue charges in respect of NPD and PFI contracts are expected to be £1.3bn in 2018-19.

Ongoing budget management will also be required to smooth any potential shortfalls in tax receipts identified earlier in this briefing. Latest forecasts point to potential tax receipt shortfalls relative to Budget forecasts that may require the Government to build up resources within the Scotland Reserve. This may mean that the Scottish Government has to forego some expenditure in the near term to fund future tax receipt shortfalls if outturn receipts come in under forecast. Of course the Fiscal Framework also provides the option of borrowing £300m per annum to cover forecast error.

Use of either the borrowing powers or the Scotland Reserve will have implications for the government’s non-protected budget. Borrowing in any given year will boost the budget but will incur repayment costs in the future. Building up the Scotland Reserve implies an opportunity cost (in terms of reduced expenditure) today but greater resilience in future years.

Subject Committee pre-Budget reports

The Budget Process Review Group recommended that subject committees should publish pre-budget reports as a way of identifying their budget priorities in advance of the Government bringing forward its budget. The Written Agreement1 states that each Committee should write to their respective portfolio minister at least 6 weeks prior to the publication of the budget, setting out their views on the delivery, impact and funding of existing policy priorities. Committees will also be free to make proposals for changes.

Subject committees with non-protected areas of expenditure within their remit may wish to consider how these budget challenges are tackled, and if they wish to make any recommendations for changes.

Subject committees may also wish to consider whether the information in the Financial Strategy has proved useful in informing their pre-budget scrutiny or whether there is further information or analysis that would be helpful in future documents.

Has the Financial Strategy delivered BPRG recommendations?

The Budget Process Review Group final report recommended that a Medium Term Financial Strategy be published annually. The purpose of the MTFS, according to the Group, would be to ‘provide a means of focussing on the longer term sustainability of Scotland’s public finances’.

The Group recommended that the Scottish Government ‘should work towards the MTFS consisting of the following four elements’:

forecast revenue and demand-led spending estimates from SFC and their effect on Scottish public finances

broad financial plans for next five years

clear policies and principles for using, managing and controlling the new financial powers

scenario plans based on economic forecasts and financial information in order to assess potential impact of various scenarios on the budget.

The Scottish Government indicates that it expects that the document will evolve over time. This section takes each of the four elements in turn and comments on what the document has delivered.

Forecast revenue and demand-led spending estimates from SFC and their effect on Scottish public finances

The SFC forecasts for tax revenues inform the charts on the overall outlook for the Scottish budget presented in chapter 6. The document points out that these “provide an indication of the direction of travel and potential scale of the final reconciliation” but that “significant uncertainties remain, as experience shows that forecasts are subject to considerable change between fiscal events.”

Broad financial plans for next five years

The document provides an upper, lower and central range for the Budget outlook over the forecast period, which might be categorised as broad financial plans.

The document does not contain budget allocations “at this stage” or spending plans by portfolio. The Cabinet Secretary in his statement to Parliament highlighted the challenge in doing so, but hinted that this may be possible following the UK Spending Review next year:

we do not currently have any resource budget allocation from the UK Government beyond 2019-20. It is hoped that the UK spending review next year will offer sufficient future year budget information to allow the Scottish Government to develop multiyear budget allocations.

The document lists a series of already announced policy priorities around Health, the Police, Early Learning and Childcare, Attainment and Higher Education.

Prioritising some areas of expenditure will obviously have implications for “non-protected” parts of the Budget. The largest non-protected part of the Budget is the non-education element of Local Government.

However, subject committees may feel that there is little that was not already known about their areas of the budget.

On tax, the document restates the Scottish Government’s approach to taxation founded on the four “Adam Smith principles of certainty, convenience, efficiency and proportionality to the ability to pay”. It restates the approach taken to the setting of tax rates in 2018-19.

The document is noticeable, however, for not including any new Scottish Government strategies for handling the potential economic and budget challenges highlighted by the SFC’s weak economic growth and reduced tax revenue forecasts. The document’s conclusion includes the following statement:

This forward look does not set out any new decisions or policy commitments, particularly in relation to the public sector, and only seeks to explore and explain the range of factors and variables which require consideration by the Scottish Government when making financial decisions and undertaking longer-term budget planning.

Clear policies and principles for using, managing and controlling the new financial powers

The document does contain some helpful information about how the Scottish Government plans on using its capital borrowing powers (see chapter 3). It contains a table outlining its current levels of capital borrowing and repayment profile, and discusses its self-imposed fiscal rules on revenue funded investment (to not exceed 5 per cent of the total annual budget available). It presents helpful tables outlining its revenue commitments against its revenue funded investment fiscal rule (table 3.2) and a breakdown of this information by project type (table 3.3).

As noted, the document says little about how any potential revenue shortfalls might be accommodated.

Scenario plans based on economic forecasts and financial information in order to assess potential impact of various scenarios on the budget

Chapter 7 outlines the implications of the various scenarios for Resource expenditure (see charts 7.1, 7.2 and 7.3).

These charts factor in the Budget priorities already identified by the Scottish Government around Health, Police, Childcare and Attainment and presents what that means for “other expenditure”.