Climate Change and Agriculture: How can Scottish Agriculture Contribute to Climate Change Targets?

This briefing considers Scottish agriculture and climate change by summarising current emissions from the sector, exploring existing emissions reduction policies and programmes, and investigating new techniques that may allow the sector to reduce emissions further.

Executive Summary

The Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill proposes a statutory target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 90% by 2050 (from a 1990 baseline) across the whole Scottish economy. It also allows for a target of 100% reduction in emissions (known as a net zero target) to be created at a future date, from the same baseline. The UK and Scottish Government's statutory advisers, the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), consider the 90% target to be at the limit of feasibility. The Scottish Government is however under pressure from stakeholders to set a specific net zero target in the Bill.

The main greenhouse gases are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O). CH4 and N2O have a significantly higher global warming potential than CO2; in other words, their total warming impact is greater relative to CO2 over a set period. Emissions are reported and predominantly discussed in a common unit of CO2 equivalent (CO2e).

Agriculture (including associated land use) is the second largest contributor to Scottish emissions (after transport at 37%), accounting for just over a quarter of Scotland’s total in 2016. Methane and nitrous oxide are emitted in significant quantities by agriculture. These are inherent in food production due to biological processes and chemical interactions in both livestock and plant growth. Therefore, the approach to mitigating emissions from agriculture differs to most other sectors where CO2 is the overwhelmingly dominant greenhouse gas. As more progress is made in reducing emissions in for example electricity or waste, the relative importance of agriculture in the total Scottish emissions budget grows.

The CCC’s latest report for Scotland considers that “the ambition in the agricultural sector and the focus on voluntary measures remains concerning. Agriculture will need to make a greater contribution to meeting emissions targets, especially if Scotland is to meet a net-zero target as proposed in the Climate Change Bill”. Emissions from agriculture and related land use have been largely static for 10 years.

Livestock emissions account for around 48% of the agricultural total (by CO2e), most of which can be attributed to methane emissions from cattle and sheep. Agricultural soils and land-use change emissions account for a further 43%.

The use of the phrase “net-zero greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture” appears to have been fairly widely misunderstood; this is perhaps not helped by the way that emissions are accounted for and set out in the emissions inventory. The reality on the ground is that the activities of farmers and land managers both contribute to and sequester greenhouse gases. If farmers are to maintain a headage of livestock, even at a reduced rate, then there will be methane emissions, however this can be balanced by actions elsewhere.

Understanding these interactions can lead to a degree of confusion, and some stakeholders have called for a better explanation of and accounting for different land use sectors.

Recent research on Soil Carbon and Land Use suggests that an improved understanding of CH4 and N2O emissions is likely to lead to greater opportunities for emissions reductions than that provided by solely increasing carbon sequestration through e.g. peatland restoration or tree planting.

Multiple opportunities exist to reduce emissions arising on-farm. Many of these will require shifts from business as usual behaviour, and include agroforestry, restoring peatlands, soil testing and management to increase carbon capture, changes to cattle feed to reduce enteric emissions, farming breeds and crop varieties that produce less methane, precision agriculture to reduce fertilizer and pesticide use, and dietary change.

Introduction

The Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009, sets a target to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by at least 42% by 2020, as a step towards an 80% reduction by 2050i. To maintain flexibility to achieve least cost decarbonisation, targets are for emissions across the whole Scottish economy; there are no statutory sectoral targets.

The Scottish Government's Climate Change Plan1 (CCP) sets out “the strategic framework for our transition to a low carbon Scotland”, and proposes “envelopes” for GHG emissions reductions across seven key sectorsii, based on “least-cost pathways” generated by the Scottish TIMES Model2, a high-level whole energy system model.

The Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill (the Bill) responds to Scotland’s commitment to the Paris Agreement to limit global temperature rises to well below 2ºC and to pursue efforts to limit global temperature increases to 1.5ºC, to reduce the risks and impact of climate change.

The Bill was introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 23 May 2018, and proposes a statutory target to reduce GHG emissions by 90% by 2050 across the whole Scottish economy. It also allows for a target of 100% reduction in GHG emissions (known as a net zero target) from the baseline to be created at a future date.

The UK Committee on Climate Change (CCC), in their Advice On The Bill3 describe 90% by 2050 as a “stretch target” that “is at the limit of the pathways currently identified to reduce Scottish emissions”.

In a debate on 12 June 2018 the Cabinet Secretary for Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform stated that “this Government wants to achieve net zero emissions as soon as possible”, and as “soon as the evidence indicates that there is a credible pathway to net zero emissions, we will use the mechanisms in the bill to set the earliest achievable date in law”4.

However, the Scottish Government is under pressure to set a specific net zero target in the Bill. Written evidence to the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee's call for views, including e.g. from WWF Scotland5, Friends of the Earth Scotland6, Stop Climate Chaos7, and Professor David Reay8 supports this approach, and it is becoming one of the key subjects of debate throughout the passage of the Bill.

Understanding the Impact of Greenhouse Gases

The main GHGs are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O). CH4 and N2O have a significantly higher global warming potential (GWP) than CO2; in other words, their total warming impact is greater relative to CO2 over a set period. Methane has 25 times the GWP of carbon dioxide, and nitrous oxide has 298 times the impact over a 100 year time horizon.

To take these different potencies into account, emissions are reported and predominantly discussed in a common unit of CO2 equivalent (CO2e, or simply “carbon”). This means that climate change mitigation efforts can be expressed in one single target across the whole economy.

Agriculture (including associated land use) is the second largest contributor to Scottish GHG emissions (after transport at 37%), accounting for just over a quarter of Scotland’s GHG Inventory in 20161.

Methane and nitrous oxide are emitted in significant quantities by agriculture. These are inherent in food production due to biological processes and chemical interactions in both livestock and plant growth. Therefore, the approach to mitigating emissions from agriculture differs to most other sectors where CO2 is the overwhelmingly dominant GHG. As more progress is made in reducing emissions in e.g. electricity or waste, the relative importance of agriculture in the total Scottish emissions budget grows. The CCP states2:

In the future, uncertainties around Brexit, growing populations and increasing pressures throughout the economy and the rising cost of living may increase the tension between climate change mitigation and providing food security. A fine balance must therefore be found to ensure GHG reduction can take place while Scotland continues to produce secure and sustainable food.

The CCP proposes a 9% reduction in emissions from agriculture between 2018 and 2032, and David Reay, Professor of Carbon Management and Education at the University of Edinburgh states in written evidence3:

Since 1990 emissions from [the agricultural] sector have fallen […], but since 2008 there has been little change. Future emissions targets for this sector are unambitious. More progress is now urgently required.

As previously noted, the Bill provides for a statutory target to reduce total emissions by 90% by 2050, and the Cabinet Secretary stated in June that a “90 per cent reduction target for all greenhouse gases means net zero emissions of carbon dioxide in Scotland by 2050”. Furthermore4:

According to the Committee on Climate Change, achieving a 90 per cent reduction in all greenhouse gases will require the [near] total decarbonisation by 2050 of energy supply, ground transport and buildings. That is what we anticipate. It means transformational change and challenging actions.

However, by far the largest source of emissions in the CCC’s scenario for 2050 will be agriculture, which, as I said, is not the same as other sectors. That needs to be recognised. We cannot produce food without emitting greenhouse gases such as methane, so setting a net zero target for all greenhouse gases before the evidence exists to support it could mean reducing the amount of food produced in Scotland without reducing greenhouse gases at the global level.

This essentially means that if Scotland is to reach net zero emissions at a future date, and mitigate the CO2e of agricultural emissions, then it will be necessary to lock away (sequester) considerably more CO2e in other sectors through e.g. peatland restoration, tree planting or emerging “negative emissions technologies” like biomass energy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) as well as significantly reducing methane and nitrous oxide emissions in the agricultural sector.

The CCC’s latest report for Scotland5 considers that “the ambition in the agricultural sector and the focus on voluntary measures remains concerning. Agriculture will need to make a greater contribution to meeting emissions targets, especially if Scotland is to meet a net-zero target as proposed in the Climate Change Bill”.

This briefing considers Scottish agriculture and climate change by summarising current emissions from the sector, exploring existing emissions reduction policies and programmes, and investigating new techniques that may allow the sector to reduce emissions further.

Emissions from Agriculture

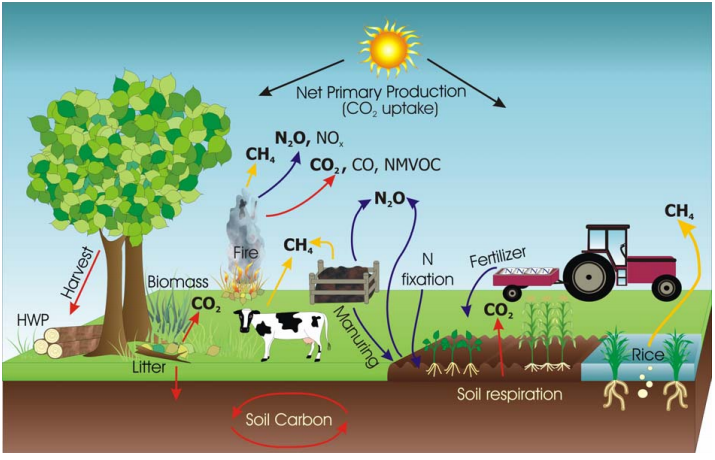

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) provides the following figure, showing the main on-farm agricultural emission sources, removals and processes.

As previously noted, agriculture (including associated land use) is an important contributor to Scottish GHG emissions, accounting for 26.1% of all GHGs. The following table shows a breakdown of agricultural emissions, their main source, global warming potential and atmospheric lifetime.

| Greenhouse Gas | Proportion (%) | Main Source | Global Warming Potential Over 100 Years | Atmospheric Lifetime |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methane (CH4) | 44% | Cattle and Sheep | 25 | 12 |

| Carbon Dioxide (CO2) | 29% | Land Use and Land Use Change, and Mobile Machinery | 1 | No defined atmospheric lifetime; however can last for many thousands of years. |

| Nitrous Oxide (N2O) | 27% | Nitrogen Fertiliser | 298 | 114 |

Livestock emissions account for around 48% of total emissions (by CO2e), most of which can be attributed to methane emissions from cattle and sheep. Agricultural soils and land-use change emissions account for a further 43% of emissions. Farm machinery only makes a small contribution to emissions, mostly in the form of CO2 (8.4%). Within the livestock emissions envelope, the following breakdown is relevant:

| Animal | Emissions (%) | Animal | Emissions (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-dairy cattle | 30.1 | Horses | 0.5 |

| Sheep | 9.1 | Poultry | 0.3 |

| Dairy Cattle | 7.6 | Deer, Goats and Other Livestock | 0.0 |

| Swine | 0.8 |

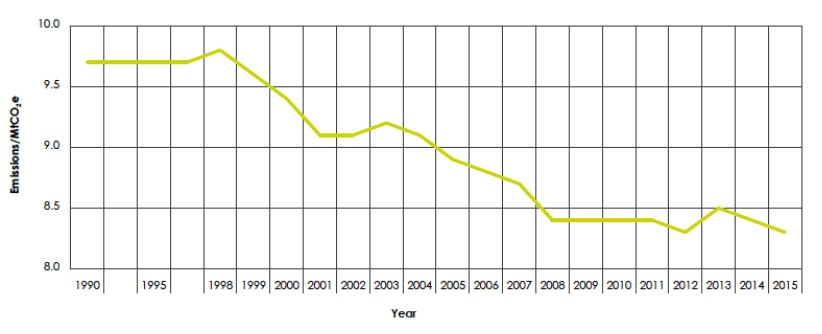

The agriculture and related land use sector has seen a 27.8% fall in emissions between 1990 and 2016. The following graph shows historical agricultural emissions in Scotland:

This fall is mostly attributable to four factors:

Efficiency improvements in farming, such as higher milk yields per cow and better fertility.

Fewer cattle and sheep.

A reduction in the amount of nitrogen fertiliser being applied.

A reduction in grassland being ploughed for arable production.

Scottish Government Climate Change Plan

The Climate Change Plan1 sets out a “roadmap for a low carbon economy while helping to deliver sustainable economic growth between 2018 to 2032”, for which a whole system energy model, known as the Times Model, forms the analytical basis.

The model helps to develop an optimal pathway for meeting Scotland’s statutory climate change targets by assessing how effort is best shared across the economy. The pathway contains a carbon envelope for each sector within the CCP, along with suggested measures needed to remain within the envelopes. Policies and proposals are then to be developed to realise these measures.

As formerly noted, agriculture (and related land use) accounts for 26.1% of Scottish emissions and the CCP proposes a 9% reduction by 2032 to agricultural emissions. Other sectors will therefore have to contribute a significantly higher proportion for Scotland’s emissions reduction goals to be achieved.

The agricultural chapter of the Plan sets out five policy outcomes to be achieved by 2032:

More farmers, crofters, land managers and other primary food producers are aware of the benefits and practicalities of cost-effective climate mitigation measures and uptake will have increased.

Emissions from nitrogen fertiliser will have fallen through a combination of improved understanding, efficient application and improved soil condition.

Reduced emissions from red meat and dairy through improved emissions intensity.

Reduced emissions from the use and storage of manure and slurry.

Carbon sequestration on agricultural land has helped to increase our national carbon sink.

The CCP does not set out any mandatory measures for farmers to reduce emissions, focussing instead on the use of voluntary incentives or financing schemes.

Agricultural emissions were the focus of many detailed responses to the Committee's call for views on the Bill. In particular, Nourish Scotland2 and Scottish Environment Link3 called for a number of statutory caps, targets and duties. NFU Scotland4, Quality Meat Scotland5 and the National Sheep Association6 held largely opposing views.

One of the key areas of agreement however was that Scotland is at a pivotal point for agricultural policy in light of Brexit; Professor Reay states7:

The UK’s exit from the EU and replacement of the CAP represents an opportunity to improve support for farmers in Scotland which simultaneously raises profitability, longterm sustainability of Scottish farming, and helps Scotland achieve its climate change targets. Central to this will be support and incentives that derive from a robust evidence base, avoid unintended consequences, and that are applicable to local contexts. Current support mechanisms focussed on climate-smart farming practice in Scotland include the Farming For a Better Climate (FFBC) programme designed to encourage voluntary uptake of good practice through support and demonstration. Since its inception this programme has directly involved around a dozen farms, but this is nothing like the scale required for sector-wide progress.

A key question therefore remains – what additional capacity and initiatives are available should more be required of the agricultural sector?

Measures of Accounting for Greenhouse Gas Emissions

As part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), all signatories are required to use a comparable methodology to report their national emission inventory. The UK submits annual reports of GHG emissions, which allow key sources of pollution to be identified and highlighted.

In The true extent of agriculture's contribution to national greenhouse gas emissions, Bell et al1 note that “quantification of the impacts that agriculture is having on the environment is […] of major importance”. However, it is “also important that the methodologies used to report data are robust and provide an accurate estimate of emissions in order to allow policy makers to make informed decisions”. They go on to note that:

Flaws in the assessment of agriculture's contribution will lead to dispute, failure to trust the science, and consequently, failure to act. Global recognition of the extent of agriculture's contribution to GHG emissions is required, as is quantification of how its contribution compares to that of other emission sources. Although many nations have attempted to quantify and pin-point their GHG emission sources, uncertainties remain, and improvements in the methodologies used are regularly reported. The extent to which IPCC reporting guidelines identify, describe and quantify agricultural emissions is critical for effective mitigation.

Scotland’s GHG emissions are compiled and reported on in line with IPCC guidance, and this data are used to report against statutory targets. For the purposes of reporting, GHG emissions are allocated into nine sectors, however the CCP, which is developed using the TIMES model, sets out policies and proposals for seven sectors. The interaction between these is set out below:

| Climate Change Plan Sectors | Greenhouse Gas Inventory Category |

|---|---|

| Electricity | Power Stations |

| Buildings | Residential and Public Sector Buildings and Services from Business and Industrial Processes |

| Transport | Transport, including all domestic and international Aviation and Shipping |

| Industry | Industry and Refineries emissions from Energy Supply |

| Waste | Waste Management |

| Land Use, Land Use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF) | Land Use and Forestry and Development |

| Agriculture | Agriculture and Liming |

A letter to the ECCLR Committee in June 2018 providing additional information on the GHG inventory, states3:

The most challenging estimates in the inventory relate to emissions involving complex biological processes and can be found in four main sectors: Forestry, land-use, agriculture and waste management. Emissions estimation in these areas generally involves complex models built upon the results of a considerable programme of academic research in each field.

Because agriculture is a form of land use, and agricultural operations rarely happen in isolation from other land uses, there are obvious and significant interactions between the agriculture and LULUCF sectors; in practical terms, in terms of how emissions are reported, and in terms of how they are tackled. Understanding these interactions can lead to a degree of confusion, and some stakeholders have called for a better explanation of and accounting for the land use sectors, as set out in the section on stakeholder positions below.

The letter goes on to set out where emissions are derived from in each of the relevant sectors:

Agriculture and Related Land Use emissions are derived from cropland, grassland along with emissions from land converted to cropland and grassland. It also covers emissions from livestock, agricultural soils, stationary combustion sources and off-road machinery.

Development emissions are derived from settlements and from land converted to settlements.

Forestry emissions and sequestration activities are derived from changes in net emissions relating mainly to stock changes, resulting from afforestation, deforestation and harvested wood products.

The difference between the Inventory and TIMES/CCP is down to the Related Land Use component of Agriculture which is captured in the Agriculture and Related Land Use category in the Inventory and in the LULUCF sector envelope in TIMES/CCP.

The TIMES/CCP sectors differ from the Inventory sectors because the Scottish TIMES model used the UK Times model as a starting point, the Scottish approach reflects the structure of the UK model for consistency. Whilst, as previously noted this can lead to confusion, what matters is that emissions are accurately calculated and accounted for, not where they are set out on an inventory.

Recent improvements to accounting for agricultural emissions in the UK have come through a new SMART Inventory4 which was implemented in 2018 following the completion of an extensive seven year work programme to improve the method for estimating non-CO2 emissions in UK agriculture. The inventory makes a number of improvements, including:

Considering fertiliser application rates, soil texture and rainfall, to better explain how N2O emissions can vary spatially.

Providing greater detail on the main sources of CH4 emissions. The inventory has different emission factors for cattle by age, breed, feed type and production system (e.g. upland and lowland).

Estimates of CH4 from manure management are broken down by storage type (slurry tank, lagoon etc.).

Therefore, the main changes this year (2018) are:

Agriculture emissions are now estimated to be around 15% lower than in the 2015 inventory, with the trend from 1990 broadly unchanged.

Soil emissions are now estimated to be 42% lower, largely due to revised fertiliser emissions. The trend since 1990 is broadly unchanged, although there is greater variability in the series reflecting better spatial disaggregation and taking account of rainfall and soil type.

Methane emissions are estimated to be 5% lower, largely driven by a 9% reduction in enteric fermentation emissions, partially offset by a rise in emissions from manure management.

The Smart Inventory is therefore better able to explain the variation in emissions intensity that occurs through various production systems and regions.

Emissions Abatement Potential and Costs

Emissions abatement means using technology or measures to reduce emissions and/or their impacts on the environment.

Recent research on Soil Carbon and Land Use1 suggests that an improved understanding of CH4 and N2O emissions is likely to lead to greater opportunities for mitigation than that provided by solely increasing carbon sequestration through e.g. peatland restoration or tree planting.

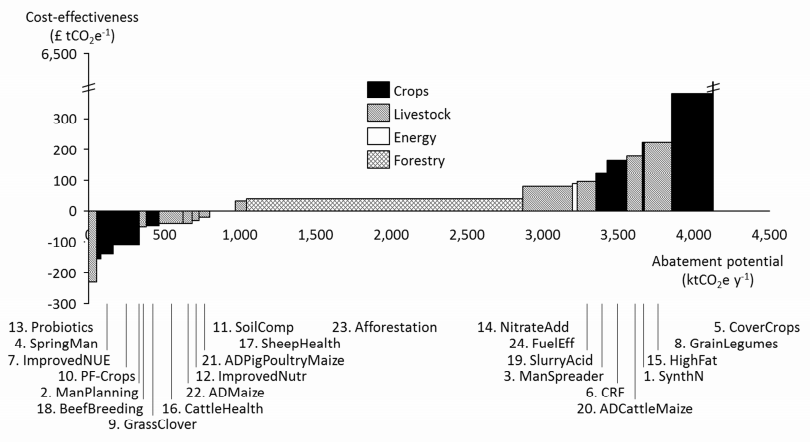

The potential for emissions abatement of 24 different measures was explored in 2015 by the CCC2. This used Marginal Abatement Cost Curves (MACC) to explore the most cost effective approaches.

Marginal Abatement Cost Curves

MACCs are a commonly used policy tool indicating emission abatement potential and associated costs. They have been extensively used for a range of environmental issues in different countries and are increasingly applied to climate change policy. They are not intended to be used for setting emission reduction envelopes or for direct extrapolation into a policy setting.

MACCs seek to evaluate the cost of individual mitigation measures and their potential to reduce emissions or sequester atmospheric GHGs, relative to a baseline (typically a business as usual pathway). A MACC curve permits an easy to read visualisation of various mitigation options or measures organised by a single, understandable metric i.e. the economic cost of emissions abatement.

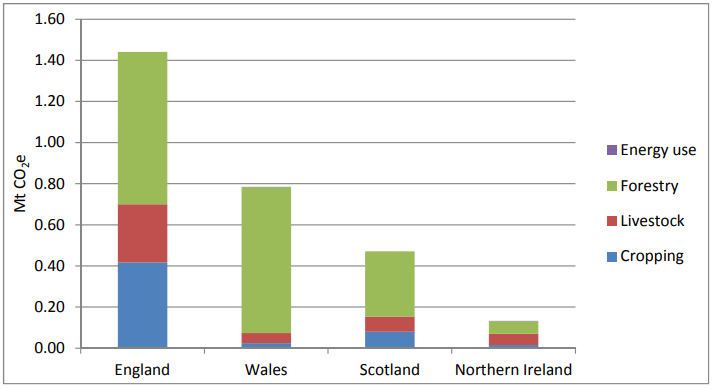

The CCC’s 2015 report set out four scenarios representing different options for reducing emissions. The central, most feasible scenario considered the use of financial incentives to encourage farmers to act. The following graph shows the potential contribution of cropping, livestock, forestry and energy use related mitigation measures; across the devolved administrations, forestry is shown to be the most cost effective abatement measure2.

Some other mitigation measures were also considered to be cost effective:

Improving cattle health.

Precision farming for crops.

Loosening compacted soils and preventing soil compaction.

Improving sheep health.

Anaerobic digestion.

It is important to emphasise that the environmental, economic and social circumstances of farms vary; Appendix 1 shows a MACC for UK agriculture out to 2030.

Current Activities to Reduce Emissions

Examples of current support schemes to improve agricultural efficiency and reduce GHG emissions include:

The Beef Efficiency Scheme assists farmers to improve the efficiency of their beef suckler herd. The five year scheme contributes to a range of improvements focusing primarily on cattle genetics and management practices on-farm. Increasing efficiency aims to reduce the emissions from beef production and improve overall herd profitability.

The Farm Advisory Service (FAS) is an initiative funded by the EU and Scottish Government to help farmers and crofters increase the profitability and sustainability of their business. The FAS offer grant support, a full programme of events, a subscription service for crofts and small farms, and a range of articles and publications, designed to provide integrated advice for farmers and crofters across Scotland. This includes fully funded carbon audits of farms or crofts.

Farming for a Better Climate is managed by Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC) and aims to highlight measures that will help farmers make more efficient use of their resources and have a positive impact on farm business profitability. The initiative works with farmers and land managers to encourage and advise on the uptake of practices that will help the sector to become more profitable whilst moving towards a low carbon sustainable future in addition to promoting climate change adaptation.

The Soil Nutrient Network, managed by SRUC, is taking a ‘before and after’ look at how to protect and improve farm soils and make best use of both organic and inorganic fertilisers. Benefits include saving money, improving yields and greater farm efficiency and resilience. There are currently 12 farms in the network.

The UK Woodland Carbon Code is a voluntary standard for UK woodland creation projects. Through the Code, some farms participate in ‘carbon offset’ schemes through planting woodland whilst also bringing an additional income stream into the business.

Feed-In Tarrifs (FiT) and the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) pay for the generation of renewable electricity and heat. The FiT provides a payment for all electricity produced and an additional bonus payment for electricity exported to the grid. FiTs have helped farmers to generate low-carbon electricity (e.g. wind or solar) to power farm business units and export any surplus back to the grid. The RHI provides financial incentives to increase the uptake of renewable heat by businesses, the public sector and non-profit organisations.

The Monitor Farm Programme is run jointly by Quality Meat Scotland and the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board and aims to establish a group of farms to serve as monitor farms to help improve the profitability, productivity and sustainability of producers. There are nine monitor farms in Scotland.

These initiatives focus on a combination of behavioural change and encouraging the application of precision agriculture techniques to make farms more efficient. The schemes aim to foster a more profitable agricultural sector in Scotland that is less carbon intensive. The focus to date has been limited to supply side measures and the exploration of demand side initiatives e.g. dietary change is conspicuous by its absence.

In 2011, an article in the Journal of Food Policy, entitled Where are the best opportunities for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the food system (including the food chain)?1 concluded that “a priority for decision makers is to develop policies that explicitly seek to integrate agricultural, environmental and nutritional objectives” for the reduction of food related GHGs. This was reiterated in 2012 by a study for the EU2 that recognised that “shifting to a more healthy and balanced diet, eating less meat and dairy products” can lead to big reductions in GHG emissions.

Further Emissions Reductions?

There has been wide-spread policy interest in measures to reduce GHG emissions arising from Scottish agriculture.

The recent Scottish Government Stability and Simplicity Consultation on proposals for rural funding post Brexit states1:

Our priority for agriculture and rural development is to provide stability and security for producers, land managers and businesses while at the same time maintaining environmental standards and making changes that will help set the sector on the right path towards decarbonisation.

And recognises that “Many of the measures described in this consultation will have co-benefits for both agricultural productivity and for reducing Scotland's Greenhouse Gas Emissions”.

The UK Government has also recently introduced a new Agriculture Bill 2017 to 2019 to the House of Commons for farming in England. Under this Bill, farmers would be rewarded for signing up to “environmental land management contracts”, which would commit them to measures protecting wildlife, soil, water and air quality. The new system would be phased in from 2021 to 2027, with the government providing subsidies along the same lines as the EU CAP up to 2021. The recently published SPICe Briefing on Post – Brexit Plans for Agriculture2 is relevant.

As previously noted, agriculture contributes around a quarter of Scotland’s GHG emissions, however the CCP sets out a 9% reduction in emissions for this sector between 2018 and 2032, proportionately less than in other areas (e.g. electricity, industry, waste). In late March 2018, a joint open letter3 from fifty organisations and academics (including those with farming and land management interests) called on the Scottish Government to:

[…] support farming practices that are less damaging to our climate and put us on a path to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture by 2050

The letter proposes four measures for carbon neutral farming:

Nitrogen balance sheets: National Nitrogen balance sheets would help government develop evidence based policies and targets to improve efficacy of nitrogen use.

Investing in soils: Continue to restore carbon rich peatlands, safeguard semi-natural grasslands and protect and improve valuable agricultural soils. Farmers should be incentivised to test soils to increase soil organic matter which can lock in carbon.

Promote carbon-neutral farming: Promoting and supporting organic farming and efficient mainstream production. Must produce more food from farms and help drive transformation to carbon-neutral food production.

Promoting agroforestry: Integrating trees into farming businesses could be of value to them and the environment. Agroforestry can sequester carbon and protect soils as well as diversify farm income, shelter livestock and provide fuelwood.

What Does Net-Zero Mean, and What Feasibility is There of Meeting It?

The use of the phrase “net-zero greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture” appears to have been fairly widely misunderstood; this is perhaps not helped by the differentiation between LULUCF and Agriculture in the CCP and emissions inventory, when the reality on the ground is that the activities of farmers and land managers both contribute to and sequester GHGs.

If farmers are to maintain a headage of livestock, even at a reduced rate, then there will be methane emissions, however this can be balanced by actions elsewhere. In written evidence to the Committee, Professor Reay states1:

Mapping the policies and proposals that can achieve a net zero emission Scotland is already possible. Yes, it is difficult – some sectors, such as agriculture […], will remain net GHG sources post 2050 – but these unavoidable emissions can and should be balanced by net sequestration.

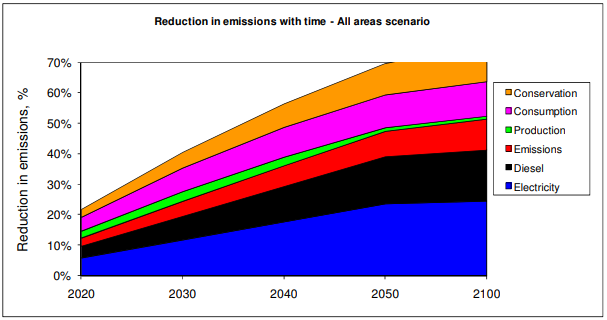

How Low Can We Go? An assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from the UK food system and the scope for reduction by 20502 by the Food Climate Research Network (FCRN) and WWF UK has explored the feasibility of a 70% cut to emissions from the UK food chain, where cuts could be made, and by how much. The study investigated a range of approaches to making the cuts in emissions through three broad thematic scenarios:

Energy based scenario with a focus on decarbonisation across the food sector. The result: 57% emission reduction by 2050.

Emission led scenario focusing on (i) reducing direct emissions (e.g. CH4) arising from cows and sheep and N2O arising from fertilisers plus (ii) improved production efficiency for crops and livestock. The result: 55% emission reduction by 2050.

Conservation through (i) waste avoidance and using food waste to generate energy and (ii) changes to consumption patterns in the UK. The result: 60% emissions reduction by 2050.

A combination of approaches (i.e. decarbonisation of the economy, better production efficiencies, reduction in waste, emissions abatement and changes in the type of foods consumed) is recommended and under such a combination the 70% target could be reached. The report concludes that emissions reductions on the supply side alone are unlikely to be adequate without corresponding demand side mediation. The following figure from the FCRN and WWF Report shows emission reductions over time as affected by the rate of implementation of all categories of measures.

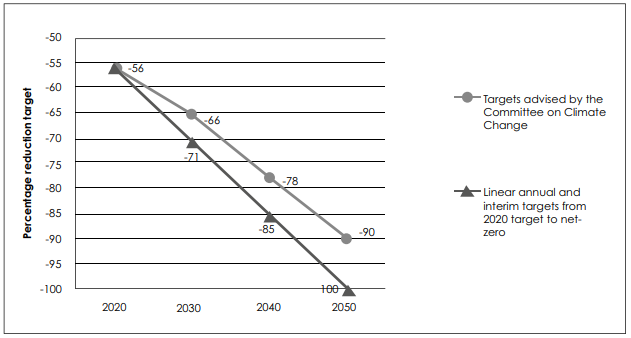

Going beyond the CCC’s advised target of 90% by 2050 would imply also going beyond the advised target levels for 2030, 2040, and all the annual targets from 2021 onwards. The following figure shows the targets advised by the CCC and net-zero by 2050.

The Scottish Government published Net-zero greenhouse gas emissions target year: information and analysis3 alongside the Bill, which suggests that committing to targets that are beyond technical feasibility would mean:

Paying other countries to reduce emissions on our behalf (instead of focussing purely on domestic effort).

Removing some sectors from the target.

Making legally binding commitments that are dependent on as yet undeveloped technological advancement and cannot be properly scrutinised.

Taking steps that would have a substantial detrimental impact on people’s wellbeing and the economic growth of Scotland.

The CCC’s advice on a 90% target suggests that the sectors of the Scottish economy where any substantial emissions are likely to remain in 2050 (after achieving a 90% reduction in emissions) would be agriculture, aviation and maritime transport, and industry. Of these, emissions from agriculture are considered to be the largest.

Future Policy Instruments to Further Reduce Emissions

As previously noted, multiple opportunities exist to further reduce emissions arising on-farm, albeit with upfront additional cost and technological investments. Many of these will require shifts from business as usual behaviour in the agri-sector and Appendix 2 details a broad review of technological and strategic options that could form part of a governmental response to reduce emissions.

In 2012, the International Institute for Environment and Development published Climate change and agriculture: can market governance mechanisms reduce emissions from the food system fairly and effectively?1 This suggests that actions are required on multiple fronts including regulatory, economic and voluntary, as well as labelling, information and awareness raising to reduce GHG emissions. Avoiding ‘leakage’ (i.e. offshoring domestic food demand through greater reliance on food imports) is particularly important. Some possible policy responses include:

Paying farmers to sequester carbon on their lands. There is a strong potential to use market instruments to pay farmers for sequestering carbon on their lands. However, such schemes are limited in their influencing potential. Ensuring lasting positive change in practices beyond the financing period will only occur where these practices give rise to benefits valued by the farming community, e.g. productivity gains.

Carbon financing. Carbon finance generally refers to resources provided by governments to reduce GHG emissions. These have been used widely both in the UK and elsewhere. Well-designed financing schemes have the potential to achieve triple wins of GHG mitigation, enhanced food productivity, and income generation.

Emissions trading schemes. Emissions trading schemes may be able to achieve emission reductions at a lower cost to farmers than taxation, which can be ineffective and sometimes unfair. However, since agricultural production gives rise to CO2, CH4 and N2O the design of such schemes is inherently more complex than those based on CO2 alone.

Taxation. Taxes covering both organic and mineral nitrogen sources may be more effective than a tax on only one. Taxing outputs of pollutants rather than inputs may be more effective and cost efficient for farmers and is also perceived to be fairer. Taxes could be made more acceptable if revenues were ring-fenced and used to fund research and development in the agricultural sector.

Regulation. Regulation can operate effectively in conjunction with fiscal mechanisms, such as emission trading schemes. To be effective, regulations need to be flexible and backed up by ongoing investment in research and by robust measurement and monitoring measures. Farmers need to be informed and supported if schemes are to succeed.

Position of Stakeholders

Interviews were conducted by the authors with multiple agricultural, land use and environmental stakeholders in August and September 2018 to identify areas of consensus and concerns relating to further reducing emissions.

There was widespread agreement that efficiency improvement measures (e.g. nitrogen balance sheets; feed additives; better application of fertilisers; on-farm soil testing and on-farm carbon auditing) were win-win opportunities to both reduce GHG emissions and improve farm environmental and monetary performance. Additionally, most were in agreement that there is a need for a combination of regulatory and incentive support frameworks needed to further reduce emissions and increase uptake of emission reduction schemes.

Strengthening farm advisory services and better engagement with farmers through demonstration farms was seen as critical across all stakeholder groups. Most parties were generally supportive of using incentive schemes that could pay farmers for sequestering carbon on their lands and providing additional environmental services that may compliment emissions reductions. While agroforestry measures were generally widely supported by stakeholders, there were some concerns that they may in-fact reduce the productivity of Scottish agriculture.

Many discussions with stakeholders related to behaviour change, and are supported by Defra’s Agricultural Statistics and Climate Change1 research which imply a lack of improvement in the UK agricultural sector, both in terms of farmer attitudes and the take-up of mitigation practices. Almost half of farmers place little or no importance on GHG mitigation and/or believe their farm produces no emissions:

49% of farmers reported that it was 'very' or 'fairly' important to consider GHGs when making decisions relating to their land, crops and livestock. Just over half of respondents placed little or no importance on considering emissions when making decisions and/or thought their farm did not produce GHG emissions.

Overall, 56% of farmers were taking actions to reduce emissions - little change on 2016. Of these, larger farms were more likely to be taking action than smaller farms.

For those farmers not undertaking any actions to reduce GHG emissions, informational barriers were important, with both the lack of information (34%) and lack of clarity about what to do (33%) cited as barriers by this group. Some 47% did not believe any action was necessary (unchanged from 2016).

Specific comments raised by stakeholders include the following:

National Farmers Union Scotland

The NFUS support a 90% reduction to GHGs in the Bill, however oppose mandatory carbon reduction measures in agriculture.

NFUS originally signed the March 2018 letter calling for a pathway to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture by 2050, however have subsequently withdrawn their support.

In The National Farmers Union Scotland: Steps to Change paper1, carbon auditing and carbon management (including carbon sequestration) are highlighted as annual environmental measures that could be deployed to reduce GHG emissions.

Additional measures outlined that may compliment reductions to GHGs include soil sampling including targeted input use and integrated pest management practices.

There will need to be a significant effort to bring the lowest performing farms (in emissions and profitability terms) up to standard for a broader sectorial response to reduce emissions.

Quality Meat Scotland

QMS recognise that agriculture needs to make a contribution to emissions reductions, however there are real concerns that agriculture cannot get to net-zero emissions because of biology/physiology of livestock production.

Growing the food and drink business to a scale of £30 billion turnover by 2030 is incompatible with the net zero emissions target.

Need clearer direction from Government concerning the livestock sector and future GHG emission reduction approaches. Reducing production means we may simply be exporting our production footprint elsewhere, resulting in leakage.

Creating opportunities for new entrants (with appropriate qualifications) into farming is important for innovations to improve farm efficiency.

Scottish Land and Estates

SLE continues to support the March 2018 letter calling for a pathway to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture by 2050.

GHG inventories don’t adequately reflect the GHG/environment management situation on the ground – by separating LULUCF and Agriculture the sequestration activities of farmers and land managers are not represented accurately.

SLE supports the development and introduction of a nitrogen balance sheet as per March 2018 letter.

Appropriate funding and leadership is need to ensure that the industry changes, this should be accompanied by a regulatory back-stop to ensure behaviour change across the sector.

“There is a pressing need for the agriculture and land use sector to embrace change” – e.g. through GHG sequestration/mitigation/adaptation, and CAP reform post-Brexit.

Behaviour change in the sector is particularly problematic, with many of the older generation of farmers struggling to understand and adapt to new practices.

Soil Association

The Soil Association has called for a commitment to zero carbon farming by 20501. They suggest the capacity of soils to store carbon is increased, agroforestry is promoted, and the use of nitrogen fertiliser is reduced.

The Soil Association no longer support a net-zero GHG emissions target, but they do support the call for a 90% reduction to GHG emissions across Scotland.

Employing a net zero emissions target could have potentially adverse effects for the farming sector. GHG emission reduction policies should be sensitive to local landscapes and cultural traditions.

There is a need to reduce consumption of certain foods – the efficiency route may not result in absolute reductions to GHG emissions necessary to meet a net-zero target.

Scottish Wildlife Trust

The SWT support a net-zero emissions target but further suggest a net-zero target does not mean all agricultural GHG emissions will end by 2050.

The SWT propose1 a four-tier hierarchy of regulation and support payments for natural capital maintenance, enhancement, and restoration for the delivery of ecosystem services (including GHG abatement and sequestration).

They further suggest such Natural Capital Maintenance and Natural Capital Enhancement Payments should be available to all farms set on a per hectare basis for different land types.

Behavioural changes may be one of the biggest obstacles to achieving GHG reductions and many challenges for reducing GHG emissions further are no longer technical.

SWT widely support the use of a nitrogen balance sheet but also other efficiency improvements, such as feed additives.

Nourish Scotland

Nourish Scotland are promoting the establishment of agroecology1 as the underlying principal of farming in Scotland. Additionally, they suggest the need for a whole system approach to reducing the impact of food production on the environment.

Separate chapters in the CCP for agriculture and LULUCF make it difficult to monitor emissions reductions in farming and structure complimentary initiatives that use land based approaches to reduce emissions.

The CCP is unambitious in its strategy to reduce emissions. There are opportunities to reduce GHG emissions by a further 25% to 30% whilst still maintaining food production.

Advocate mandatory soil testing for farmers to ensure optimal pH, reducing artificial nitrogen applications and better timing of applications, the development of a nitrogen budget by 20202 and more growth of clover on grazed grassland.

Scotland should develop an equivalent of DEFRA’s Agricultural Statistics and Climate Change and Agricultural Indicators for GHG Emissions3.

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

Determining the emissions flows from Scottish food production more broadly is important to identify targeted policy interventions to reduce GHGs.

There is a need to focus on LULUCF and agriculture together in the CCP and the GHG emissions Inventory because the land use sector has considerable opportunities for carbon sequestration to balance minimised emissions from agricultural land.

There is a need for regulatory measures to improve efficiency, including soil testing, nutrient planning which may be considered “easy wins”.

There hasn’t been enough support to farmers for voluntary measures to have adequate uptake. If voluntary measures are to be the method of choice, a regulatory backstop will be needed.

Scottish Crofting Federation

Agroforestry measures would be supported by the crofters in addition to deployment of payment for public goods type approaches to sequestering carbon on farmed lands.

Quick wins for GHG mitigation include headage reduction and use of land for carbon sequestration.

Need a mixture of regulatory (backstop) and incentive approaches (to lead with) to encourage uptake of measures to reduce GHGs on farm. Rewarding good management practices is important. If using regulatory measures, they must be adequately policed.

Scottish Natural Heritage

There is need to move towards more closed loop systems and develop circularity within agricultural production, through agro-ecology and agro-forestry. Advisory services would need to be strengthened to support such system changes and bottom up innovation should be encouraged.

More accurate application of fertilisers and precision farming techniques and in general innovations that boost efficiency are valuable tools. While these types of approaches are win-wins they are unlikely to meet the GHG reduction targets alone.

Moving to a largely incentive based system that pays by public funds for public goods to incentivise more systemic change may be necessary as efficiency improvements alone won’t be enough in a trajectory towards zero net carbon.

Impacts and Opportunities Arising from Net-Zero Emissions

Implementation cost – the MACCs associated with different future activities to reduce emissions will likely vary widely. Increasing from a 90% to net-zero reductions in GHGs will affect potential budgets for lowering emissions across all sectors.

Competitiveness and resilience – The implications of the targets on competitiveness with other producing countries should also be considered. For instance, the Deputy President for the NFU has recently stated1 “When it comes to setting a zero carbon goal, regulators need to be mindful that in the case of agriculture, it is all too easy to make our own farmers uncompetitive through over-bearing regulation which will simply suck in higher carbon imports”. Additionally, the former chair of QMS, Jim McClaren has stated2 that a net-zero target could have “devastating consequences” for the Scottish livestock sector. He suggested that setting a legal net-zero target now would require 16,000 hectares of woodland planting per year, the use of GM crop technology and zero livestock production.

Potential for win-win outcomes – Improving the efficiency of farming practices is central to reducing GHG emissions across the different farming sectors. Previously mentioned measures promote innovation and the adoption of modern farming techniques that could integrate quality food production with balanced and more sustainable agro-ecological systems.

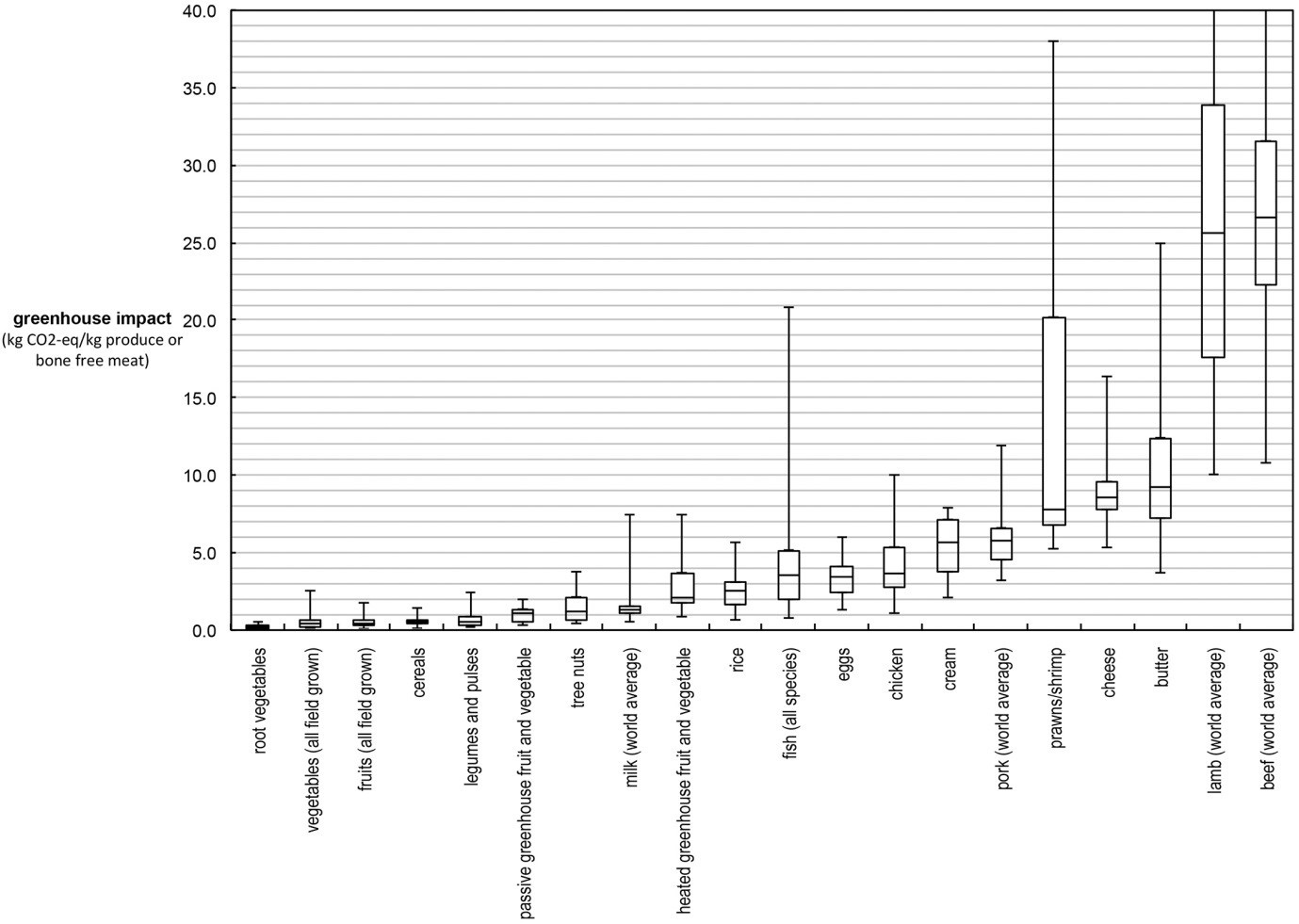

Sector by sector breakdown – The implications of employing a net-zero target is likely to have a disproportionate effect on specific agricultural sectors. The livestock sector (accounting for 48% of all agricultural GHGs in Scotland) is likely to be most affected. In particular, beef and dairy production will be most impacted – generally the farm sectors with the highest GHG footprint3. Other sectors, including grains and fruit and vegetables are said to have the lowest GHG emissions intensity4 – Appendix 3 sets these out in more detail.

Small-scale farmers – Adoption of emissions reduction strategies and technologies may be disproportionally challenging for small-scale farm businesses. These businesses will find it difficult to adopt new approaches without clear tangible benefits and high transaction cost. Additional financial support (through incentives) is often required.

International Case Study – Origin Green

Launched in 2012, Origin Green is the national sustainability programme for the Irish food and drink industry. It is the only sustainability programme in the world which operates on a national scale, uniting government, the private sector and food producers, through the Irish Food Board.

Independently verified, Origin Green enables Ireland’s farmers and food producers to set and achieve measurable sustainability targets, reduce environmental impact and serve local communities more effectively.

Since it started, over 117,000 beef carbon assessments have been completed, as well as over 20,000 dairy carbon assessments on farms. Many Irish food and drink manufacturing companies have now become fully verified members of Origin Green, more than doubling the performance of the scheme in 2016. This comes in addition to the introduction of retail and foodservice companies to the programme, thus ensuring all levels of the supply chain are participating in Origin Green.

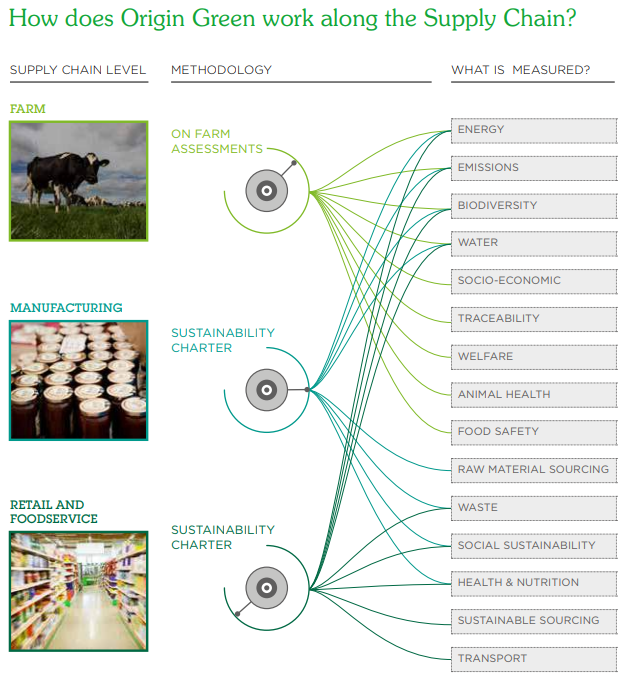

Origin Green claim that bringing beef and dairy farms currently operating below average efficiency in-line with other farms would potentially reduce emissions by over 1.4M tonnes CO2e annually. This equates to 7% of total emissions from Irish agriculture. An infographic demonstrates how Origin Green works along the supply chain to improve efficiency and reduce emissions in Appendix 4.

Appendix 1: Marginal abatement cost curve to 2030

Appendix 2: Description of different technological or strategic measures to reduce GHG emissions in Scottish agriculture.

| Measure | Outline |

|---|---|

| Agroforestry. | Agroforestry is the practice of growing trees and crops in interacting combinations. Agroforestry systems are believed to have a high potential to sequester carbon because of their perceived ability for greater capture and use of growth resources (i.e. light, nutrients, and water) than single-species crop systems. Trading of the sequestered carbon is a potential opportunity for agroforestry practitioners. Additionally, the use of trees in sheep farming has been promoted by the National Sheep Association (NSA) and the Woodland Trust. However, sequestration abatement during forest expansion is a one-off opportunity; once a forest reaches its full size it will no longer sequester significant additional carbon from the atmosphere. Additionally, it may conflict with productive land availability. |

| Restoring peatlands. | Peat soils cover over 20% of Scotland, storing 1600 million tonnes of Carbon. Peatlands in good conditions actively form peat, which can remove CO2 from the atmosphere and store it in soil, whereas degraded peatlands release CO2. The Climate Change Plan aims to restore 50,000 hectares of degraded peatlands by 2020, then 250000 hectares by 2030. Increasing restoration activities could further increase sequestered Carbon. However, the costs associated with peatland restoration are often prohibitive and restoration tends to take place over longer time periods. |

| Incentivising farmers to test soils to increase soil organic matter. | Farmers can manage land in a way which increases soil carbon capture. Providing ways to monitor soil organic matter content can provide information on how their land management is impacting soil organic matter. The James Hutton Institute have developed a soil carbon app which provides a model to predict soil carbon. The Soil Association have produced a position paper to urge Defra to include soil organic matter testing in their new mandatory soil testing. This is additional to current requirements for pH soil testing in Scotland. |

| Novel feed rations for cattle. | Recent experimental work has revealed adding seaweed to cattle feed can dramatically decrease their emissions of methane. While the work has not explored the viability of cultivating and harvesting seaweed for production, it nonetheless suggests a reduction in GHG emissions with no ancillary impacts to milk taste and flavour. Further work is required in this area to assess the viability of using novel feedstocks. |

| Supplementation to reduce methane. | Biological or chemical feed supplements that inhibit methane production are potential opportunities to further reduce emissions, however there may be concerns over animal health and welfare, and all supplements must be EU approved to allow sale of produce. Experimental work has found that a supplement added to the feed of cows reduced methane emissions by 30%. Adding fat to the diet of livestock will reduce the amount of carbohydrate consumed. It is known that fats reduce the number of protozoa (the number of protozoa is linked to methane production in the rumen). There is now evidence that plant oils supplemented to a grass silage-based diet can reduce ruminal methane emissions arising from dairy cows. However, other mechanisms (e.g. potential to increase CH4 emissions from manure storage) might partially offset this mitigation. |

| Reduce crude protein intake in animal diets. | Manipulation of animal diets by reducing crude protein intake is a strategic ammonia abatement option as it reduces the overall nitrogen input at the very beginning of the manure management chain. A recent review has found higher ammonia reductions in cattle highlights the opportunity to extend concepts of feed optimization from pigs and poultry to cattle production systems to further reduce emissions from livestock manure. Work by DairyCo suggests dietary protein levels for lactating dairy cows could be reduced to perhaps as low as 14% crude protein with no or little loss in milk yield and quality. However, the scarcity of data that exists for high-yielding dairy cows in the UK suggests more experimental work may be needed to identify optimal crude protein intake. |

| Farm with breeds and varieties that produce less methane. | Work is on-going to identify cattle breeds that produce less methane. Other work is exploring wheat and maize varieties that inhibit the production of nitrous oxide, through the release of nitrification inhibitors from plant roots. This option generally works either indirectly, through improving the productivity of the animal or variety or indirectly, by selecting for animals/varieties that are associated with reduced emissions intensity. However, breeding and selection tend to be longer-term activities that feature slow national uptake across farms. |

| Deploy farm robotics for precision agriculture. | Advancements in agricultural technologies are gathering pace and it is now one of the fastest growing global markets. Technology has the ability to increase production while improving efficiency and reducing climatic and environmental impacts. CEMA (European Agricultural Machinery) suggest precision farming and smart machine technology rank among the most cost-effective GHG reduction measures for agriculture in the years to come. Precision agriculture aims to increase output while reducing input costs for the application of e.g. seeds, pesticides, fertilizers and fuel. Advanced machine technology (increased machine automation, interconnectivity, robotic solutions and drones) and data-driven innovations (earth observation to inform field-scale management) are said to be particularly promising for both improved efficiency by Gebbers et al (2010). However, initial capital investment costs are likely to be prohibitive for smaller farms. |

| The application of novel, low-emission fertilisers. | Efficient use of fertilisers, especially nitrogen, is essential to reduce nitrous oxide emissions arising from agriculture. Among the technologies that can contribute to efficient use of fertilizers are slow-or controlled-release products to enable slow release of nitrogen into the soil during the crop-growing season. Experimental work has found nitrous oxide emissions in the field arising from novel slow release fertilisers (made from nanocomposites) were reduced substantially. |

| Re-wetting artificially drained organic soils. | Drained organic soils are emission hotspots and their re-wetting is attractive as a climate change mitigation measure. Recent work has shown high potential for re-wetting of organic soils and nutrient rich grasslands to reduce CO2 emissions from agriculture. The cost effectiveness of such an approach is currently unclear. |

| Specialised management of manure from dairy production facilities. | Manure management at dairy production facilities, including anaerobic digestion and solid-liquid separation, has shown strong potential for the abatement of GHG emissions. The amount of GHG reduction varies according to what were the emissions from the original storage, which, in turn, depends e.g. on the type of storage, on the temperature, whether the storage was covered or not. AD is a capital intensive technology, the high upfront costs make it profitable only on bigger farms or if manure is brought in from neighbouring farms. Beyond the capital costs the annual operating costs and maintenance costs can be significant. |

| Optimal pasture management to reduce GHG emissions. | By managing for more optimal forage growth and recovery through adaptive multi-paddock grazing (i.e. non-continuous grazing on the same pastures) can improve animal and forage productivity, potentially sequestering more soil organic carbon (SOC) than continuous grazing. This challenges much existing research that tends to suggest only feedlot-intensification reduces the overall beef GHG footprint through greater productivity. The Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases suggest improvements in pasture quality through pasture renovation, fertilisation, irrigation, adjusting stock density, avoiding overgrazing (including through fencing and controlled grazing), appropriate rotations, and introduction of legumes are well understood and effective practices that could be spread more widely. |

| Changing where we procure food from. | The movement to increase locally-grown food has intensified in an effort to reduce the carbon footprint of the food chain by reducing the need to transport food products over large distances. But the carbon footprint of locally-grown food is not always better than for imported food. One study, for example, found that tomatoes grown in the U.K. emit more than three times as much CO2 per ton as tomatoes imported from Spain. |

| Eating novel foods to reduce GHG emissions. | Recent research suggests eating insects instead of beef could help tackle climate change by reducing emissions linked to livestock production. Replacing half of the meat eaten worldwide with crickets and mealworms would cut farmland use by a third, substantially reducing GHG emissions. This recent work found that insects and imitation meat – such as soybean-based foods like tofu – are the most sustainable forms of meat consumption as they require the least land and energy to produce. Beef was found to be the least sustainable food option. |

| On-farm carbon management and mandatory auditing. | Carbon accounting enables farmers and land managers to estimate the emissions of CO2, CH4 and N2O produced from farm operations and land, as well as estimate the carbon locked up (sequestered) through soil and woodland management. This can lead to efficiency improvements, benchmarking performance and greater transparency. |

| Continuing professional development (CPD). | Making future support payments contingent on compulsory CPD may improve the production efficiency of farms, thereby helping to drive knowledge and uptake of GHG mitigation practices on farms and reducing GHG emissions in agriculture. |

Appendix 3: Summary of global warming potential values across broad food categories

Appendix 4: Supply chain efficiency in Origin Green