The Human Tissue (Authorisation)(Scotland) Bill

The Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill sets out proposals to change the system for authorising organ and tissue donation in Scotland. Most notably, it proposes to introduce a system of 'deemed authorisation' (often known as presumed consent).This briefing outlines the proposals in the Bill and the views expressed in the Health and Sport Committee's written evidence and survey. The briefing also looks at the evidence around the effect of presumed consent on organ donation.

Executive Summary

The Bill contains proposals to introduce a system of 'deemed authorisation' for organ and tissue donation for transplantation (often known as 'presumed consent'). What this means is that when someone dies but they have not made their wishes on donation known, their consent to donation would be presumed unless their next of kin provided information that this was against their wishes.

The main aim of the Bill is to increase the organ donation rates and, as a consequence, the number of transplants carried out.

The organ donation rate has generally been increasing over the last decade, as has the transplant rate. Consequently, the transplant waiting list has been decreasing. However, at any one time there are still over 500 people waiting for a transplant in Scotland and between 40-60 people will die each year while waiting.

The Bill is mainly concerned with increasing deceased donation rates. However, only a small number of people die in circumstances which allow them to be donors. In Scotland, there are about 400 potential donors each year but only around 100 of these people will actually become donors.

There are many reasons why someone may not become a donor but one reason is family refusal. The family refusal rate in Scotland is around 40% each year and results in the loss of around 100 potential donors.

Part of the logic of the Bill is that by presuming consent, there will be fewer occasions when family authorisation is required and this may reduce the family refusal rate and thereby increase donations.

The current legislation operates on an opt-in basis. Relatives can authorise donation when someone has not recorded a decision, but it does not contain any provisions which allow someone's relatives to overrule a recorded decision. However, in practice, organ retrieval would not proceed if the family objected. Each year, around 10% of potential donors who have recorded a decision to donate will have this overruled by their relatives. Last year 69% of potential donors were not on the organ donor register.

The Bill would establish three options for expressing a wish on donation; opt-in, opt-out or do nothing. It is the last option where significant change is being proposed by the Bill as in these circumstances your authorisation will be deemed and donation could go ahead. There would be no override for the family but they would be involved in ensuring the deceased person's wishes were known.

The Bill would provide a legal basis for opting-out although people can do this already.

Deemed authorisation would not apply to people under 16 years of age, those without capacity to understand deemed authorisation and those who have been resident in Scotland for less than 12 months.

Deemed authorisation would not apply to all organs and tissues but it is expected to apply to commonly donated organs and tissues. Exceptions would be set out in regulations.

The Bill would amend the existing legislation to allow greater flexibility in when donation could be authorised. This would allow authorisation to occur before death and enable preparations for non-heart beating donations.

The Bill would also clarify when certain medical procedures can be carried out before a person dies in order to help prepare someone for donation. The Bill calls this pre-death procedures. It proposes that some procedures may go ahead where authorisation for donation would be deemed.

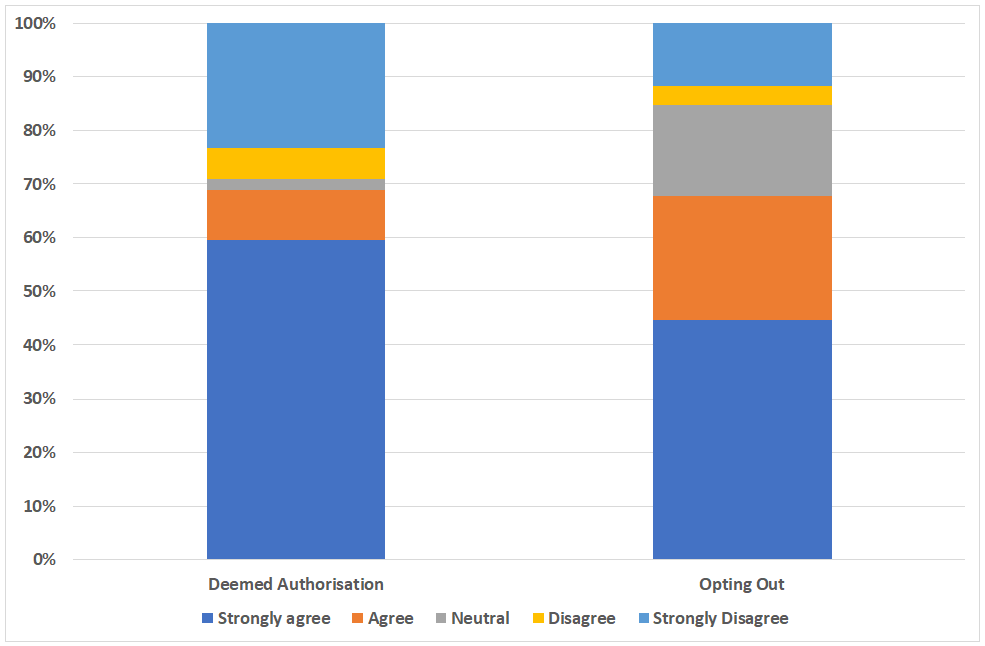

Opinion polls tend to show the majority of people are in favour of presumed consent and opting-out. The survey of the Health and Sport Committee found 68.8% in favour of a move to deemed authorisation.

Respondents to the Committee's survey contained differing opinions about the evidence around the effectiveness of presumed consent. The body of robust evidence in this area is relatively small, but country comparisons generally show an association between presumed consent and higher donation rates. Before and after studies have also shown an increase in donation rates but these studies suffer from a number of methodological limitations.

Spain is used an example of a country where opting-out has resulted in high donation rates. However, in practice, Spain effectively operates an opt-in system and its architects credit other factors for being instrumental in the higher than average rates.

The main objection of survey respondents opposed to the Bill related to the role of the state in assuming ownership of people's bodies and the idea that donation should be a gift. 22.5% of survey respondents said they would opt-out if the Bill became law.

Other key issues raised by respondents to the Committee's consultation included;

whether the family's wishes should also be taken into account when deemed authorisation applies,

whether deemed authorisation may increase family uncertainty about a person's wishes and lead to more refusals

whether there will be adequate opportunities for people to opt-out

confusion over the different options created by the Bill

when pre-death procedures could take place.

Introduction

The Human Tissue (Authorisation)(Scotland) Bill is a Scottish Government Bill which was introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 8th June 2018 by the then Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, Shona Robison MSP.

The Bill contains proposals to introduce a system of 'deemed authorisation' for organ and tissue donation for transplantation (often known as 'presumed consent'). What this means is that when someone dies but they have not made their wishes on donation known, their consent to donation would be presumed unless their family provided information that this was against their wishes.

The main aim of the Bill is to increase the organ and tissue donation rate and as a consequence, the number of transplants carried out.

Background to the Bill

The idea of introducing presumed consent in Scotland has been discussed a number of times in the past. Most notably this included the consideration of a Member's Bill in the last session of Parliament. This was The Transplantation (Authorisation of Removal of Organs etc.)(Scotland) Bill introduced by Anne MacTaggart. .

Prior to this, the Organ Donation Taskforce undertook a thorough review of the proposal in 2008. The taskforce considered the evidence on donation rates, alongside the practical, legal, ethical, clinical, cultural and financial implications. It concluded:

On balance, the taskforce feels that moving to an opt out system at this time may deliver real benefits but carries a significant risk of making the current situation worse.1

The taskforce explained that although they had heard evidence of an association between opt-out systems and higher donation rates, they had also heard about the potentially negative consequences for clinical practice and the need for recipients to know that their organs had been freely given.

Further to this, the Scottish Government published its long-term strategy for organ donation in 2013.2 In this, the Scottish Government explained that there was no consensus within its advisory group (the Scottish Transplant Group) on whether presumed consent would increase donation rates. As a result the Scottish Government committed to wait for the evaluation of the Welsh opt-out legislation before making a decision about the introduction of the policy in Scotland.

The Member's Bill in the last session of Parliament is the most recent time the policy has been considered, but the Bill did not proceed past stage 1. The conclusion of the Health and Sport Committee was:

A majority of the Committee is not persuaded that this Bill is an effective means to increase organ donation rates in Scotland due to serious concerns over the practical implications of aspects of this Bill. A majority of members consider that there is not enough clear evidence to demonstrate that specifically changing to the opt-out system of organ donation as proposed in this Bill would, in of itself, result in an increase in donations. As a result a majority of the Committee cannot recommend the general principles of the Bill.

However, the Committee did call upon the Scottish Government to consult on a 'workable' soft opt-out system for Scotland, alongside other measures to increase donation and transplantation. The Scottish Government duly consulted in December 2016.3

Donation and Transplantation in Scotland

Types of Donation

Currently organs and tissue for transplantation can be made available in the following ways

Through deceased donation (donation after death), specifically:

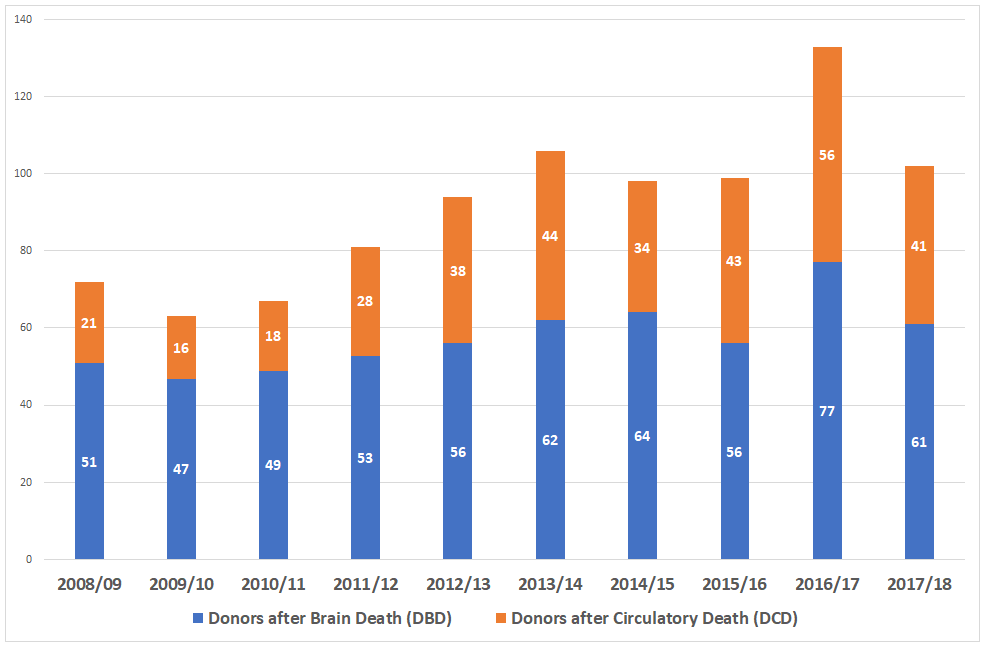

Donation after brain stem death (DBD) - from individuals who generally have been pronounced dead in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) using the neurological criteria known as ‘brain stem death testing’. The technical term is now 'donation after diagnosis of death by neurological criteria' or DNC for short.

Donation after circulatory death (DCD) - from individuals who also generally die in ICU as a result of heart or circulatory failure and who are pronounced dead following observation of cessation of heart and respiratory activity.

Through living donation, for example in the case of kidneys or parts of a liver.

Number of donors and transplants

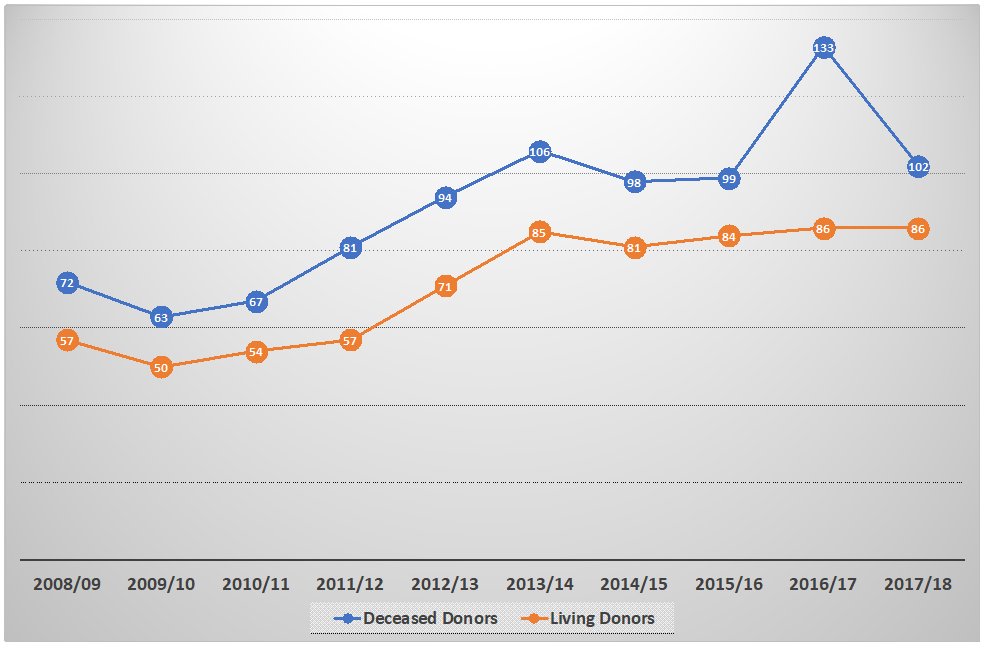

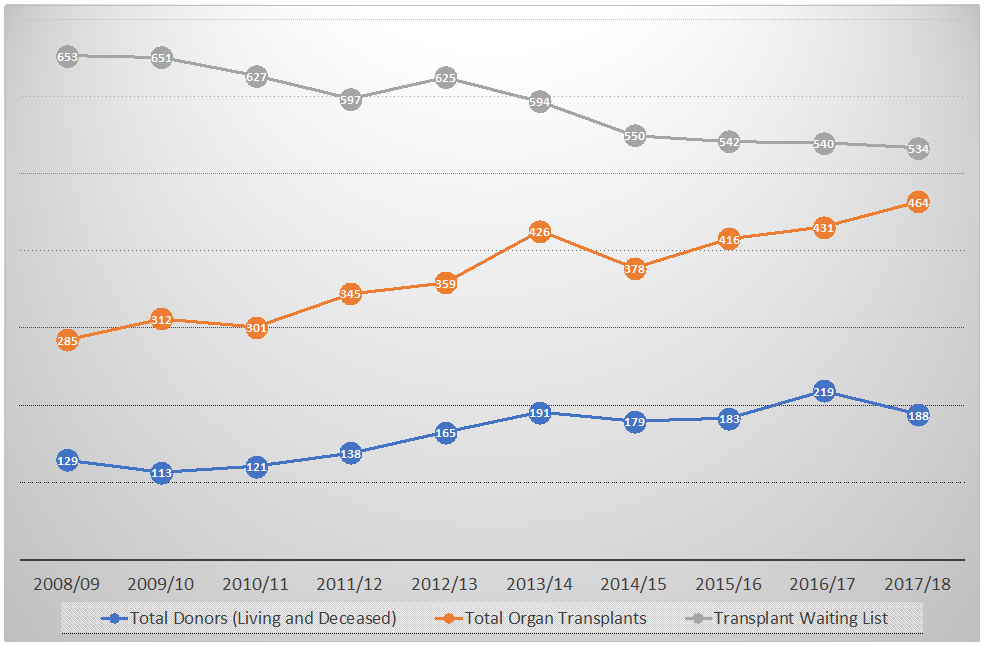

In 2017/18, 464 donor transplants were carried out in Scotland and the number of deceased and living donors has generally shown an increase since 2008.

At the same time, there has also been an increase in the number of transplants carried out, as well as a decline in the number of people on the waiting list.

However, there are still over 500 people waiting for an organ at any one time.

Deaths on the transplant waiting list

Each year between 40-60 people on the waiting list will die while waiting for an organ to become available.

| Year | Number of Deaths |

|---|---|

| 2008/09 | 47 |

| 2009/10 | 58 |

| 2010/11 | 44 |

| 2011/12 | 60 |

| 2012/13 | 45 |

| 2013/14 | 40 |

| 2014/15 | 40 |

| 2015/16 | 44 |

| 2016/17 | 55 |

| 2017/18 | 43 |

Potential donors

The Bill is predominantly concerned with increasing the number of deceased donations. While over half of the Scottish population is on the organ donor register (2,768,838 as at 30 September 2018), the number of potential deceased donors each year is small and only around 1% of people die in circumstances which allow them to become an organ donor.1

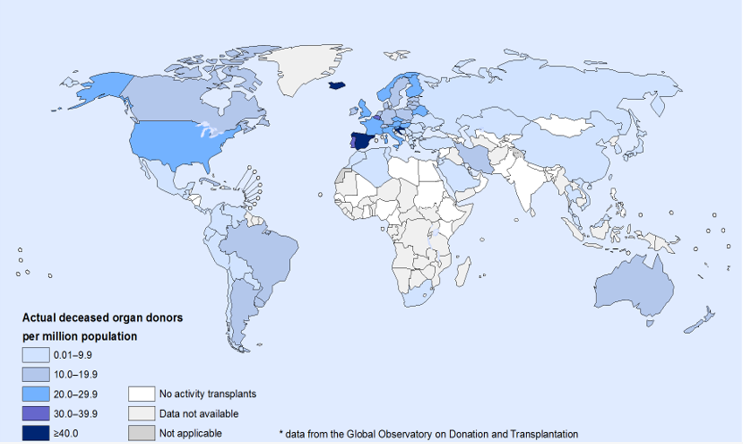

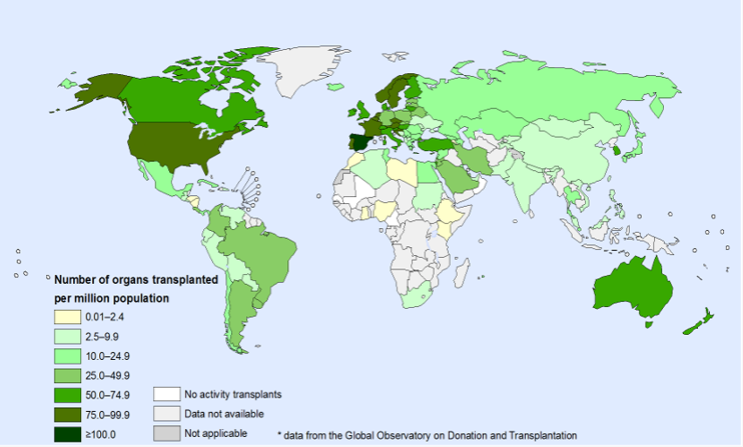

For comparative purposes, donations and transplants are often expressed as a rate 'per million population' (pmp). For example, the deceased donor rate in Scotland last year was 19.3 pmp and the transplant rate was 69.4 pmp.2

The Potential Donor Audit calculated that there were 391 eligible donors in Scotland in 2016/17. There are many factors which can affect whether donation can proceed but if all of these people had donated, then the donation rate in Scotland would have reached 72.8 pmp.3

Within the UK, Scotland has the lowest deceased organ donor rate but has the highest transplant rate. This may be due in part to the fact that Scotland has a greater proportion of people on the transplant list than the rest of the UK and organs are distributed between the UK countries.

| England | Wales | Scotland | Northern Ireland | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | PMP | Number | PMP | Number | PMP | Number | PMP | |

| Deceased Donors | 1349 | 24.4 | 79 | 25.4 | 104 | 19.3 | 39 | 21 |

| Transplants | 3353 | 60.7 | 139 | 44.7 | 375 | 69.4 | 115 | 61.8 |

| Transplant List | 5101 | 92.3 | 233 | 74.9 | 534 | 98.9 | 137 | 73.7 |

The complementary strategies published by the Scottish Government and NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) aim to increase deceased donation rates to 26.0 pmp and deceased donor transplantation rates to 74.0 pmp by 2019/20.51

The Financial Memorandum to the Bill contains a range of estimates as to how deemed authorisation might increase donation and transplantation rates.7 It sets out the following:

Lower estimate - no effect.

Mid range estimate - authorisation rate increases to an average of 65% resulting in an additional 12 deceased donors and 28 organ transplants per year.

Upper estimate - authorisation rate increases to an average of 65% but using the upper range of eligible donors, the number of donors increase by 24 and result in an additional 59 transplants per year.

The document also highlights that the current UK wide system of organ allocation needs to be factored in to estimates of the effect on transplant numbers:

...any increase in Scottish deceased donor numbers would not lead to a proportionate increase in Scottish transplant numbers as Scottish transplant numbers depend on deceased donor numbers across the UK as a whole.

Family refusals

Part of the logic underpinning deemed authorisation is that - by presuming consent - in many cases authorisation by the family may no longer be required and this should hopefully reduce the number of families that refuse to donate their loved one's organs.

The refusal rate in Scotland has consistently been around 40% over the last decade and this results in a loss of around 100 potential donors per year.

| Year | Eligible donors and family approached | Authorisation given by family | Family refusals | Family refusal rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010/11 | 140 | 80 | 60 | 42.9% |

| 2011/12 | 162 | 101 | 61 | 37.7% |

| 2012/13 | 213 | 128 | 85 | 39.9% |

| 2013/14 | 216 | 133 | 83 | 38.4% |

| 2014/15 | 245 | 132 | 113 | 46.1% |

| 2015/16 | 251 | 144 | 107 | 42.6% |

| 2016/17 | 270 | 171 | 99 | 36.7% |

| 2017/18 | 251 | 142 | 109 | 43.4% |

Current law in Scotland

The current system for authorising the donation of human organs and tissues is set out in the Human Tissue (Scotland) Act 2006 ('the 2006 Act').1 This Act established that donation after death can proceed when the individual has authorised this, either in writing or verbally.

When there is no recorded wish, the 2006 Act allows the nearest relative to authorise donation. In Scotland the current legislation enables children to authorise donation from the age of 12.

The current system is often referred to as a 'soft opt-in' in that it seeks express authorisation for donation and involves the family. Consent systems are often divided into 'hard' and 'soft' opt-out/opt-in. There does not appear to be any consensus on definitions but the terms are often used to refer to the extent to which the family are involved in the final decision.

The law does not require the permission of the deceased person’s relatives where someone has authorised donation, nor does it allow them to override any recorded wish. However, the general convention is that health professionals will not to proceed with organ or tissue removal if the relatives object. This is generally respected even if the person expressly authorised donation, for example by being on the organ donor register or carrying a donor card.

The following table shows the instances in which it was known that the person was on the organ donor register but the family overrode their wishes.

| Year | Families approached and it was known that patient had expressed wish to donate on ODR | Family refusal when it was known that the patient had expressed a wish to donate on ODR |

|---|---|---|

| 2010/11 | 32 | 1 |

| 2011/12 | 46 | 6 |

| 2012/13 | 50 | 8 |

| 2013/14 | 68 | 5 |

| 2014/15 | 76 | 18 |

| 2015/16 | 87 | 16 |

| 2016/17 | 98 | 10 |

| 2017/18 | 79 | 8 |

Comparing the data in the table above with the data in table 2 shows that families are less likely to agree to donation where an individual has not expressed a wish to donate.

In 2017/18, some 69% of potential donors approached were not on the organ donor register.

The following sections detail the main proposals in the current Bill which seeks to amend the 2006 Act.

The Bill's provisions in detail

Deemed authorisation

The Bill would establish three options for people in relation to authorising donation of parts of their body after death:

Opt-in - individuals will be able to record their decision to donate.

Opt-out - individuals will be able to record their decision not to donate.

Do nothing - individuals will have the option to neither opt-in, nor opt-out.

It is the last bullet point where significant change is being proposed by the Bill. This is because in the circumstances where a deceased person has no recorded decision, their authorisation may be 'deemed' and organ and tissue retrieval may proceed. The Bill calls this 'deemed authorisation' but it is often known as 'presumed consent'.

In effect, the first two options will be an active choice, and the last will also be viewed as a choice, albeit one that has been made more passively.

The Bill does not allow the families to override the wishes of the deceased, including deemed authorisation. However, should families be in possession of information that the deceased's wishes were in opposition to the planned course of action, then the Bill would allow this to be taken into account. The Bill also places a duty on health workers to make inquiries of the family about the potential donor's wishes.

The Bill would provide that if a 'reasonable person' would be convinced by the information that the potential donor's latest view was that they were unwilling to donate, then donation cannot go ahead.

Due to this involvement of the family in giving information about the potential donor's views, the policy memorandum to the Bill sets out that the proposals constitute a 'soft opt-out'.

Deemed authorisation would only be used for transplantation and would not apply to any of the other purposes set out in the 2006 Act. These other purposes are research, audit and education or training. The Bill also proposes adding 'quality assurance' to these purposes.

Opting out

Alongside the provisions on deemed authorisation, the Bill would allow people to make a declaration that they do not wish to be an organ donor. This is often known as 'opting out'.

People can already opt-out of donating so this part of the Bill is only new in the sense that it provides a statutory basis for a practice which is not currently contained in the 2006 Act.

The Bill will retain the option for people to make an express authorisation to donate i.e. opt in.

The Bill would also require Scottish Ministers to establish and maintain an organ donor register which should include information on people who wish to donate and those who do not. In practice this will not be a new register but it will provide statutory foundation for the current arrangements for the maintenance of the Organ Donor Register.

The following table shows the number and rate of people across the UK who have already opted out on the Organ Donor Register. Wales' higher figure is likely to be attributable to the introduction of its deemed consent legislation in 2015.

| Country | Number of Opt-outs | Opt-outs as a rate PMP |

|---|---|---|

| England | 330,797 | 5,985 |

| Scotland | 4,774 | 884 |

| Wales | 180,924 | 58,175 |

| N Ireland | 460 | 247 |

| UK Total | 517,124 | 7,850 |

Exceptions to deemed authorisation

Deemed authorisation would not apply to the following people:

Those under 16.

Those without the capacity to understand deemed authorisation.

Those who have been resident in Scotland for less than 12 months.

For these people, they could still be considered as potential donors as they would still be able to opt-in, or donation could be authorised by their nearest relative or someone with parental rights and responsibilities for a child.

Children

Deemed authorisation would not apply to children under the age of 16. Instead authorisation would be sought from those with parental rights and responsibilities (including, in cases of looked after children, from local authorities).

However, children over the age of 12 would still, as now, be able to opt-in and opt-out and this would hold the same authority as the wishes of adults i.e. it could not be over turned by the person with parental rights and responsibilities.

Adults with incapacity

Deemed authorisation would not apply to people who have not had the capacity to understand deemed authorisation for some time. For example, this might include someone with dementia.

However, people without capacity could also be considered as potential donors if the necessary authorisation was in place. Either through a wish they had recorded when they did have capacity, or with the approval of their nearest relative. The nearest relative would be required to consider the past wishes and feelings of the person, as far as they were known.

Adults not resident in Scotland

Deemed authorisation would not apply to adults who have been resident in Scotland for less than 12 months.

As with the other excepted categories of people, authorisation for donation could still be given by their nearest relative and they would also be able to opt-in or opt-out.

Excepted body parts

Deemed authorisation for donation would not apply to all body parts and a number of body parts would be 'excepted'. These exceptions would be detailed in regulations to be made by Scottish Ministers but the policy memorandum explains that deemed authorisation would only apply to:

...commonly donated types of organ and tissue e.g. heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, eyes, pancreas, small bowel, heart valves, tendons. Authorisation for donation of excepted body parts (less commonly donated types of organ and tissue) e.g. face and limbs (for transplantation or any other purpose) would be able to be given by a nearest relative, as long as it would not have been against the person‘s wishes to donate.

Scottish Parliament. (2018). Human Tissue (Authorisation)(Scotland) Bill - Policy Memorandum. Retrieved from http://parliament.scot/Human%20Tissue%20(Authorisation)%20(Scotland)%20Bill/SPBill32PMS052018.pdf

Donation of excepted body parts could still go ahead if the deceased adult had opted in or if the nearest relative gives permission, although this type of transplantation is rare in the UK.

The regulations detailing what would be an excepted body part would need to be approved by Parliament under the affirmative procedure.

Timing of authorisation

Under the Bill, some donation would still require the authorisation of a nearest relative or a person with parental rights and responsibilities for a child. The Bill would allow there to be more flexibility around when these authorisations could take place.

At the moment the 2006 Act requires that this happens once the person has died but the Bill would allow authorisation to happen before a potential donor dies in some cases. The rationale given for this in the policy memorandum is:

Flexibility around the timing of authorisation is, firstly, to support the successful transplantation of organs from donors who suffer cardiac death, known as donors after circulatory death or DCD donors (from whom organs must be removed as quickly as possible after death, to avoid deterioration).1

Authorisation ahead of death would only happen where the potential donor is incapable of authorising the decision and where they are receiving life sustaining treatment, the decision has been taken to remove that treatment and death is expected imminently.

Pre-death procedures

The Bill also contains provisions about when certain medical procedures can be carried out before a person dies in order to help facilitate successful transplantation. The Bill calls this 'pre-death procedures' (PDPs).

These procedures are important when a potential donor is expected to die after circulatory death (i.e. after their heart has stopped beating rather than from brain death). This is because in non-heart beating donations, the organs must be removed as soon as possible after death, to avoid them deteriorating. If the necessary procedures have not been carried out then this is likely to prevent successful donation from proceeding.

An increasing proportion of deceased donations in Scotland come from people who have died after circulatory death. This is shown in figure 4.

Currently, some PDPs are carried out, but this is only where the person has previously made clear a wish to donate, or where their family has authorised donation. However, the Bill proposes to clarify the circumstances in which PDPs may go ahead, and this includes where authorisation for donation is deemed (i.e. the person has not made an express wish re donation).

The Bill creates two types of procedure (type A and B) which Ministers would specify in regulations. It is likely that type A procedures would be more routine (e.g. blood/urine tests) and the Bill would allow these procedures to go ahead under deemed authorisation or when the person had opted in.

Type B procedures are likely to be less routine and include the administration of medication or more invasive tests. The Bill would give Ministers regulation making powers to specify what requirements would apply to type B procedures and how they could be authorised. Deemed authorisation would not automatically apply to type B procedures under the Bill.

The Bill provides that PDPs may only be carried out if necessary and are not likely to cause any harm or more than minimal discomfort to the patient. They would also not be carried out if it is known that they would have been contrary to the person's wishes and feelings.

The Bill would require Scottish Ministers to promote information and awareness about PDPs associated with transplantation and how they are authorised.

Role of the nearest relative

The nearest relative will not be able to override the decision of the deceased, but they would have a number of roles under the Bill. These are:

to present information and evidence of the deceased's wishes if they are not recorded or if they had changed since they were recorded

to authorise donation for those to whom deemed authorisation would not apply to i.e. those without capacity and people resident in Scotland for less than 12 months (for children this would be the person(s) with parental rights and responsibilities

to authorise the donation of organs and tissues for purposes other than transplantation i.e. education, training, research and audit, or quality assurance

to authorise the donation of excepted body parts.

The 2006 Act established a list of 'nearest relatives' in order of precedence and the provisions within the Bill that refer to the nearest relative would operate under this hierarchy. This is shown in the box below.

SECTION 50 OF THE HUMAN TISSUE (SCOTLAND) ACT 2006 - NEAREST RELATIVE

1. For the purposes of sections 7 and 30, the nearest relative is the person who immediately before the adult’s death was—

(a) the adult’s spouse or civil partner;

(b) living with the adult as husband or wife or in a relationship which had the characteristics of the relationship between civil partners and had been so living for a period of not less than 6 months (or if the adult was in hospital immediately before death had been so living for such period when the adult was admitted to hospital);

(c) the adult’s child;

(d) the adult’s parent;

(e) the adult’s brother or sister;

(f) the adult’s grandparent;

(g) the adult’s grandchild;

(h) the adult’s uncle or aunt;

(i) the adult’s cousin;

(j) the adult’s niece or nephew;

(k) a friend of longstanding of the adult.

Financial Memorandum

The estimated costs in the Bill are set out over five years:

| £ | |

|---|---|

| Public Information | £3.09m |

| Evaluation | £0.0915m |

| NHS Blood and Transplant | £2.465m |

| Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service | £0.875m |

| Total | £6.52m |

Public information

The Financial Memorandum (FM) details that the £3.09m will be in addition to the existing £250,000 allocated each year for public information. This money is intended for:

the public information campaign in the 12 months prior to the policy coming into effect

the development of campaign materials to meet the needs of different groups

direct mailing to all households

communication with those about to reach aged 16

ongoign public information campaign.

These costs will fall to the Scottish Government.

Evaluation

The FM states that the evaluation will use existing monitoring data to identify trends in authorisations. Surveys will also be used to track public attitudes and understanding towards donation. These costs will fall to the Scottish Government.

NHS Blood and Transplant

The FM calculates additional costs of £2.465m over 5 years for NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT). NHSBT manages the Organ Donor Register, organ donation and the allocation of organs to transplant recipients across the UK. The FM calculates that NHSBT will face additional non-recurring costs from:

the development and delivery of training for clinical staff and call centre staff

engagement with wider NHS staff to raise awareness and understanding of the system

The FM also details a number of recurring costs, namely:

the recruitment of 4 'specialist requestor' staff

additional costs to the Organ Donor Register team from processing registrations and enquiries

additional retrieval team costs from transport and consumables

additional Specialist Nurse Organ Donation (SNOD) costs from extra on call and transport

additional costs from donors that did not proceed.

However, the FM states that it should be possible for NHSBT to absorb some or all of these recurring costs from existing resources. This is because current funding is based on target levels of activity which are greater than actual levels of activity.

Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service

The Scottish National Blood Transfusion Services (SNBTS) is responsible for the retrieval, processing and storage of tissue in Scotland (with the exception of eyes).

The FM calculates that SNBTS will face additional costs of £875,000 over 5 years due to the potential increase in the retrieval of heart valves. These costs will come from additional staff, training and consumables.

Costs and benefits

The FM does not contain any additional costs for increased transplant activity. It explains that this is because transplant units are currently funded for 2020 target levels which are higher than current activity levels. However, it does state that additional funding may be required from year 4 onwards and this will be discussed further with transplant units.

The Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment1 provides the following summary of the potential costs and benefits of the policy based on the 3 estimates of effect:

| Total benefit years 1-5: economic, environmental, social | Total cost years 1-5: economic, environmental, social, policy and administrative | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 - Baseline estimate | £0.00m | £5.27m |

| 2 - Best estimate | £48.62m | £13.74m |

| 3 - High estimate | £102.46m | £22.54m |

Public opinion

The Scottish Government's consultation on the Bill found that 82% of respondents were in favour of deemed authorisation.1

The Health and Sport Committee of the Scottish Parliament also issued a call for written evidence as well as a survey on the Bill's proposals. The Committee received 34 written submissions and 747 survey responses.

The Committee's survey found that 68.8% of respondents agreed with a move to deemed authorisation, 29.2% disagreed and 2% were neutral.

Similarly, 67.8% of respondents were in agreement with the provisions for opt-out declarations and 15.1% disagreed. A larger proportion of respondents (17.4%) were neutral on the opt-out provisions. This may be explained by some of the comments which questioned why it was needed if people can already opt-out.

There have also been a number of opinion polls across the UK in recent years, and these tend to show the majority of people support presumed consent, albeit by differing margins. The most recent poll that could be found specifically for Scotland showed that 54% of Scottish adults would choose an opt-out system and 37% would choose an opt-in system.2

Key issues raised in Committee consultation

The following sections explore in more detail some of the key issues raised by the respondents in the Health and Sport Committee's call for written evidence and survey.

Effect on donation rates

The main objective of the Bill is to increase organ and tissue donation rates in Scotland but the responses to the Committee's consultation were divided on the likely success of the Bill in achieving this.

The following sections detail the international evidence on the effect of presumed consent, including the experiences of Spain and Wales which were mentioned by a number of responses to the Committee's survey.

International evidence base

The effect of presumed consent and opting out has been studied widely, with research taking advantage of the natural experiment created by the existence of different systems in different countries, as well as the opportunity to compare and contrast donation rates before and after the adoption of presumed consent in individual countries.

The Scottish Government produced a rapid evidence review in advance of the Bill. This concluded that:

International evidence highlights that opt out systems can be effective as part of a wider package of measures[]. However, overall the body of evidence that examines that opt out legislation in isolation causes increases in donation and transplant lacks robustness and is sparse. 1

However, the policy memorandum goes on to state that broader evidence suggests a move to an opt out system and the associated changes is likely to impact positively on factors that promote organ donation, for example, public awareness and numbers on the Organ Donor Register.

The evidence base is outlined in more detail below.

Between country studies

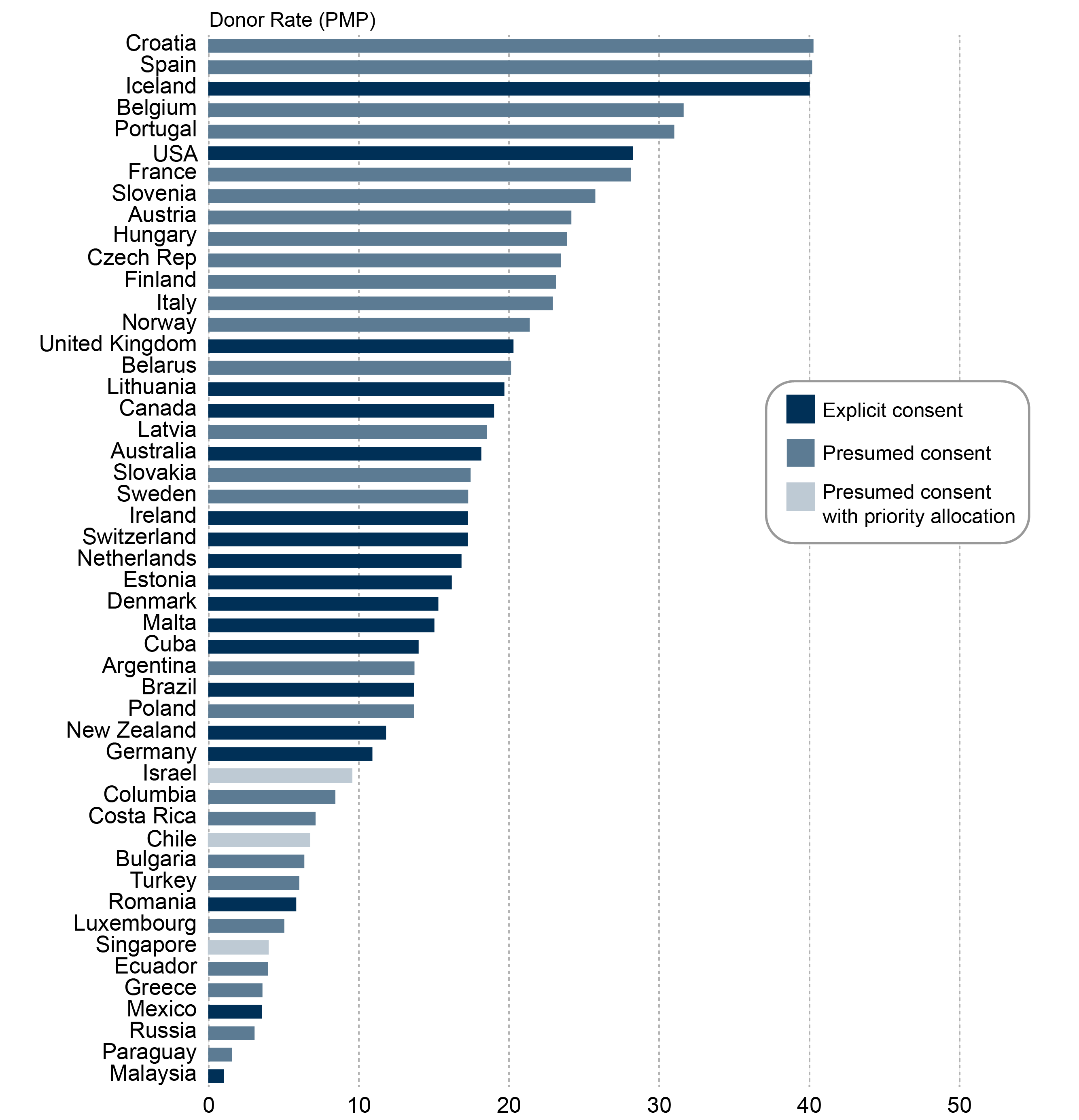

A visual inspection of how donor rates compare internationally would perhaps support the claim that presumed consent leads to higher deceased donor rates.

A number of systematic reviews have examined this association in greater detail and in 2012 the Welsh Government published an international evidence review2 which updated a previous review undertaken for the Organ Donation Taskforce.3

The Scottish Government's rapid review also looked at published research since 2012.1 The following table summarises the findings of the most relevant and robust research found in each review. This is limited to studies which examined actual donation rates as opposed to proxy indicators such as willingness to donate.

| Paper | Year | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Shepherd; O'Carroll and Ferguson5 | 2014 | The research found that deceased donor rates were higher in opt out than opt in consent countries. However, living donation - which represents a smaller source of transplants - was lower in opt out countries. The authors concluded that opt-out consent leads to a relative increase in the total number of livers and kidneys transplanted. |

| Bendorf et al6 | 2013 | Found that the number of kidneys and livers transplanted from deceased donors was higher in opt out systems, despite lower living donation. |

| Bilgel7 | 2012 | Included data from 24 countries over the period 1993-2006 and estimated that countries with presumed consent legislation have on average 13-18% higher organ donation rates than countries with informed consent legislation. |

| Neto et al8 | 2007 | Analysed data from 34 countries over a five year period and found that presumed consent countries produced 21-26% higher organ donation rates compared to countries with informed consent legislation. |

| Abadie & Gay9 | 2006 | When other variables are included in the model and held constant, presumed consent countries have an approximately 25-30% higher donation rate pmp per year than informed consent countries. |

| Healy10 | 2005 | The authors found that a presumed consent regime is worth an additional 2.7 donors pmp each year. |

| Gimbel et al11 | 2003 | Found that countries with presumed consent had on average an extra 6.14 donors PMP each year compared to countries with informed consent. |

All of these studies found that presumed consent was associated with a higher donation rate, although some found an association with lower living donor rates.

Before and after studies

It is difficult to draw conclusions from country comparisons because they can only show an association between systems of consent and organ donation rates. They cannot show a causal link. However, studies which examine donation rates before and after the introduction of presumed consent in individual countries can give additional valuable insights into the potential effect of the policy. This is because differences cannot be attributed to differences in other influential factors such as health expenditure and culture.

The systematic review for the Organ Donation Taskforce found five ‘before and after’ studies based on three countries. These countries were Austria, Belgium and Singapore. All five studies demonstrated an increase in organ donation rates after the implementation of an opt-out system for organ donation. The following table summarises the findings of these studies.

| Authors | Year | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | ||

| Gnant et al | 1991 | Compared organ donation rates in one transplant centre before and after the introduction of hard opt-out legislation in 1982. In the 4 years following the introduction of the legislation, the donor rate pmp rose from 4.6 to 10.1. |

| Belgium | ||

| Roels et al | 1991 | Compared organ retrieval and the number of transplants in 4 years before the legislation and the 3 years following its introduction in 1986. Kidney donation rates rose from 18.9 pmp to 41.3 pmp three years after the legislation came into effect. Similar increases were seen for other organs. |

| Vanrenterghem et al | 1988 | Procurement of kidneys increased from 75 in the year before the legislation to 150 in the year after. Other influencing factors were not investigated however. |

| Singapore | ||

| Soh & Lim | 1992 | Examined the average number of kidneys procured in the 17 years before the presumed consent legislation and in the 3 years following introduction in 1987. Found the average number increased from 4.7 per year to 31.1. |

| Low et al | 2006 | Compared liver donations in the 2 years before the legislation to the year after. Found the number fo referred deaths and potential donors were similar before and after. The number of liver retrievals increased from 5 to 13 per year. |

Despite the papers showing an increase in donation rates after the introduction of the presumed consent, each study had a number of methodological limitations and Rithalia et al found:

All of the studies reported an increase in organ donation rates following the introduction of a presumed consent system. However, there was limited exploration in the studies of other changes that may have taken place within the specific countries around the same time as the implementation of presumed consent legislation. As a result it is uncertain whether any changes in donation rates were directly attributable to the change in the legislation alone.3

Spain

Spain has widely been acknowledged as the country with the highest deceased donor and transplantation rates in the world. This is illustrated in the following maps.

Spain's success is often attributed to presumed consent. However, the architects of the country's transplantation service do not agree.

Spain is classified as operating a soft opt-out system and this is true in terms of the legislation. However, the year after presumed consent legislation was introduced in 1979, a royal decree clarified that opposition to organ donation could be declared by any method and so there are no formalised procedures for opting out and there is no organ donor register.

As a consequence, the Spanish legal system interpreted the decree to mean that the best way to establish the potential donor's wishes was to ask the family. In effect, this renders the Spanish consent system an 'opt-in'.1

In addition, Dr Rafael Matesanz, the former Director of the Organizacion Nacional de Trasplantes (ONT) attributes the success of the Spanish model to other influences, such as the donor detection programme and adequate economic reimbursement for hospitals.

Spain set up a nationwide transplantation co-ordination system in 1989, some 10 years after the introduction of the presumed consent legislation. The system includes co-ordinators in each of the 17 regions and a local co-ordinator in every hospital. These professionals identify potential organ donors by closely monitoring emergency departments and tactfully discussing the donation process with families of the deceased.

Dr Matesanz and colleagues previously wrote:

...the presumed consent legislation in Spain was in place for 10 years, from 1979, with little effect on organ donation rates. It was the introduction of the comprehensive transplant coordination system in 1989 that was coincident with the progressive rise in organ donation in Spain to its current enviable levels.2

He also went on to say that the appeal of presumed consent is that it will reduce the family refusal rate. However, he argues that legislation is not the key determinant of this but rather it is public confidence in the medical profession, public understanding of the organ donation process and the professionalism of the approach to the donor's family. 12

Dr Matesanz and colleagues also point to differences between the UK and Spain in terms of intensive care provision. They highlight that even if the UK family refusal rate was reduced to similar levels with Spain (from ~40% to ~15%), then the donation rate would still only be about half that of Spain's. They suggest that this may be down to relatively fewer intensive care beds which may result in this lower capacity being reserved for those with a better prognosis. As a result, those with a poorer prognosis - but greater potential to be a donor - may not be admitted to intensive care and have less of a chance of being identified as a donor.

Wales

The Welsh Assembly introduced deemed authorisation on 1 December 2015. The legislation was intended to boost the number of donors in Wales by 25% and reduce the number of deaths of those on the transplant waiting list.

In the 21 month period before the legislation came into force, there were 101 deceased donors and this rose to 104 in the 21 month period after introduction. However, the rise was not statistically significant and the evaluation report of the Welsh legislation wrote:

Analysis of the routine NHS donor data between 2010 and 2017 revealed little evidence of a consistent increase in either the number of deceased donors in Wales, or Welsh resident donors, since the Act came into force. There is no evident positive trend in recent quarterly donation figures or in the moving annual totals either side of the change in the law.1

In 2017/18, over 180,000 Welsh people had opted out on the Organ Donor Register. This equates to 5.8% of the population.

However, the family consent rates did rise significantly in Wales after the Act came into force (from 44.4% to 64.5%). This led the evaluation to surmise that the lack of a parallel effect on the overall donation number may be down to fewer eligible donors or fewer families being approached. The report recommended longer term monitoring of the routine data.

The role of the state, donation as a gift and the nature of consent

In the Health and Sport Committee's survey, the most commonly expressed opinions related to the principle of deemed authorisation. These comments tended to focus on the role of the state and donation as a gift. They were generally made by those opposed to the Bill.

By far the most commonly expressed opinion was that deemed authorisation would be tantamount to being owned by the state. Some stated it was a breach of their human rights.

I am a donor, my family are donors. I registered my son as a child (with his consent). My issue is with presumed consent, turning my choice and therefore my body into yet another chattel of the state. I know that sounds and looks obscure and obtuse, but I feel that very strongly. It would be nice to be asked.

Alongside the comments about the role of the state were a similar number of comments expressing the view that donation should be a gift and something that is given freely for altruistic reasons. Some expressed concern that a change from express authorisation to deemed authorisation could remove a vital source of comfort from grieving families.

Many also commented that to presume consent is not consent at all. These respondents contended that the lack of a recorded wish could not be taken as a choice being made and therefore to presume consent would be wrong.

Authorisation is about giving permission - it does not mean the same as presumed, deemed or implied consent.1

Some respondents felt the Bill is in contrast to the general shift in how we now view consent in medicine and in other areas of life. For example, the Montgomery ruling[1] was mentioned, as well as the move within data protection legislation to require express consent to be obtained.

Others were concerned that without express authorisation there is a danger that organs could be taken from some who would not have wished to donate.

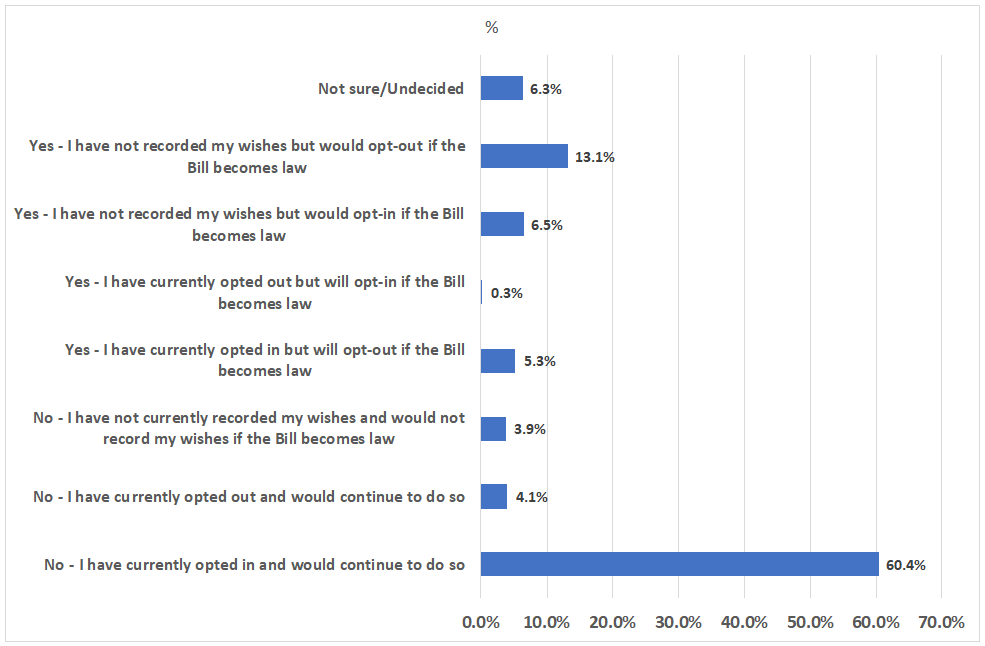

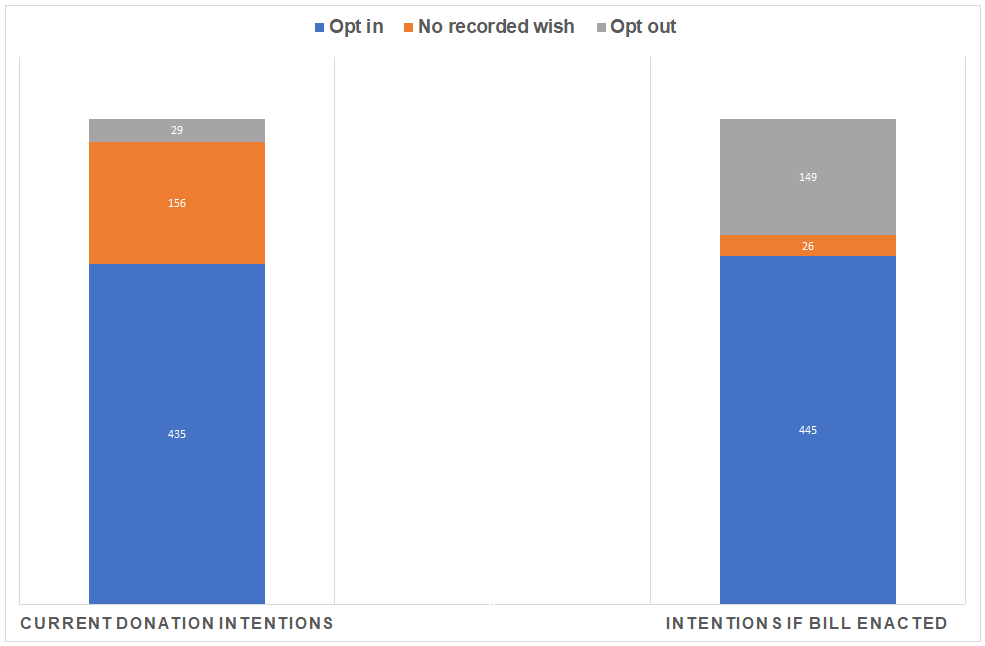

Some respondents went so far as to say that they would change their donation intentions should the Bill be passed. The following chart shows the reported intentions of respondents should deemed authorisation be introduced:

This shows that a combined 22.5% of respondents said that they would opt out if deemed authorisation is introduced. This figure is made up of:

4.1% who have currently opted out and would continue to do so

5.3% who currently opt-in but would opt out

13.1% who have not recorded their wishes but would opt-out.

The following graph illustrates the overall change in respondents' current register status, to what they say they will do should deemed authorisation become law.

It shows the biggest change is in those with no recorded wish at present, with most of these people seemingly choosing to opt-out if the Bill is passed. However, there was also a small increase in the number saying they will opt in.

[1] Montgomery vs NHS Lanarkshire - The Supreme Court decision of Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board [2015] changed the law on informed consent. It improves the protection of patient rights to information about the risks involved in proposed treatment and alternative treatments. The legal changes have influenced new ethical obligations to deliver patient-centred care and to support decision-making by health professionals

Closing the discrepancy between intent and recorded wishes

Many in support of the Bill felt that it would be of benefit to the majority of people who supported organ donation but had not recorded their wishes. These comments tended to believe that it would be better to shift the burden to act to the minority of people who do not wish to be donors.

Some also argued that, if the Bill was passed, those who do not want to donate would be more likely to record this wish and have their wishes respected, whereas at the moment they may still be considered as a potential donor.

According to NHS Blood and Transplant, around 85% of the UK population support organ donation but just 38% have recorded this wish. The proportion of the Scottish population on the register is higher at 51%.

In the Committee's own survey, 29.3% of the respondents had not recorded their wishes anywhere. Of these people, 65% did not wish to be an organ donor while 35% did. Potentially this means that presuming consent would be against the wishes of the majority of people with no recorded decision. It should however be borne in mind that respondents to the survey were self-selecting and so this may not be representative of the general population.

Soft or hard opt-out?

The Bill would not allow the family of a potential donor to override the wishes of the deceased (whether opt-in or opt-out) or deemed authorisation. There appeared to be two schools of thought within the survey comments in relation to this.

The first group expressed strong support for the lack of override and believed the wishes of the deceased should be paramount and respected, regardless of the wishes of the family.

However, there was another group of respondents who expressed unease with the idea of no family override, this was especially in relation to deemed authorisation. Some of these responses stated that if deemed authorisation was going to be introduced then it should be a 'soft opt-out' described as the family having more say in approving donation.

However, the policy memorandum to the Bill states that what is being proposed does constitute a soft opt-out system. This description seems to be predicated on the basis that the Bill provides safeguards such as involving the family in providing further information about the deceased person's wishes. In contrast, some respondents appeared to be under the impression that a soft opt-out would allow the wishes of the family to be taken into account before deemed authorisation could proceed.

This point of view was supported in the written evidence to the Health and Sport Committee, by the Scottish Council on Human Bioethics which wrote:

This […] is a complete misrepresentation and misunderstanding of both the current system and of what is being proposed with the Bill. Indeed, Scotland already has a form of soft opt out system under the Human Tissue (Scotland) 2006 Act. Moreover, what is being proposed under the Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill is actually a form of hard opt-out system for the most common organs (such as heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, eyes, pancreas) and not a soft opt-out system where relatives have a final say.

There are no agreed definitions of hard and soft opt-outs and various descriptions have been used. For example, the following is taken from the Explanatory Memorandum to the Welsh Bill which introduced deemed consent:

hard opt-out systems, whereby organs would become available for donation after death if the deceased had not opted out, but where families would have little or no involvement in the decision

soft opt-out systems, where organs would become available for donation after death if the deceased had not opted out, but where families would retain full involvement in the process.

While the difference of opinion in terminology may appear to be semantic, the underlying disagreement is about the extent to which the family should have a say when someone's authorisation is deemed.

Effect on families and refusal rates

A significant number of responses commented on the potential effect deemed authorisation could have on families and the resulting refusal rate. These comments came from both those in favour and those opposed to the policy.

On the one hand, those in favour of the Bill argued it would remove the family's burden of having to authorise donation when the person's wishes were unknown. They believed that this would be beneficial for consent rates and for the well-being of the bereaved relatives.

However, those opposed to the Bill felt that to proceed under deemed authorisation would not only add to the grief of the donor's relatives, but deemed authorisation may result in more ambiguity about their wishes. This is because their family would have no way of knowing whether it truly reflected their wishes or whether they had just not got around to registering them.

This theory is borne out to a certain degree by the data which shows that family refusal rates for adults not on the organ donor register are higher than for those who were on the register (59% vs 10%). In addition, the second most common reason for families refusing donation is they were unsure of the person's wishes.

| Reasons | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Patient expressed wish not to donate | 20.9% |

| Family were not sure whether patient would have agreed | 15.1% |

| Family felt donation process was too long | 12.3% |

| Family did not want surgery to the body | 10.1% |

| Family felt the patient had suffered enough | 6.8% |

Similarly, a recent experimental study found that presuming consent in the absence of an actively expressed choice made relatives more uncertain about the deceased's wishes and may make them more likely to refuse donation.2

We found that ambiguous signals of underlying preference that are attached to default opt-out systems contribute to families’ veto decisions as compared with active choice systems (opt-in, mandated-choice), which are substantially better at signaling intent than are passive ones.

The Welsh evidence review detailed a similar experimental study which found that the highest rates of family approval were when the potential donor had explicitly opted in to organ donation. Under a presumed consent system, family approval was lower but it was higher than for instances where an explicit consent system was in place but the potential donor had not registered.3

Opportunities for opting out

Many of the responses raised concerns that some groups may be less aware of any change in the law and may have fewer opportunities to express their wishes. The most common examples cited were elderly people and people whose first language is not English.

Specific questions were raised about the different routes that could be used for opting out and many felt that opportunities should go beyond electronic means as this would automatically exclude certain people.

Others felt that if authorisation can be deemed once someone is resident in Scotland for more than 12 months, then any awareness raising campaigns need to be run at least once a year and be conducted in numerous language.

Confusion over different options

A significant proportion of responses to the Committee's survey expressed confusion about the different options that would be available to people under the Bill. This did not relate to opting-out or deemed authorisation, but rather to the ability to still opt-in.

Many questioned the point of this and were under the impression that the proposed move to deemed authorisation meant that you would not have to opt-in:

…why would you opt-in? You are already opted-in, that's the point of the bill, if you don't want to opt-out I expect to have to do nothing, because I am in automatically.

Completely confused by this as seems to contradict presumed consent. Having to opt in on the opt out register... you've lost me.

Too complex, too many ins and outs. Needs to be simple to understand.

Others were also confused by the Bill’s proposal to provide a ‘legal basis’ to opting out when people can already opt-out. Even some of those in support of the Bill felt that the different options created could be confusing for people and any new system would need to be clearly communicated to the public.

The Policy Memorandum to the Bill states that evidence from other countries shows that more successful soft opt-out systems are associated with retaining the ability to opt in1.

Pre-death procedures

One other aspect of the Bill which concerned respondents was the part which related to pre-death procedures (PDPs).

Many in support of the Bill were content that these provisions were necessary and would provide greater clarity on when and how they could be used. They also felt that they would help improve the success of transplants from non-heart beating donations.

However, some people who commented on this part of the Bill expressed mistrust over the use of PDPs and a fear that they could be used to accelerate death in order to access a person's organs.

A proportion of both those in favour and those opposed to PDPs felt strongly that nothing should be done to a patient without their consent when it is not for their benefit. As a result, these responses called for express consent to be sought before carrying out PDPs.

While I largely agree, I feel the pre-death procedures should be a separate authorisation that should be an opt in. Opting to donate organs one your gone is one thing, preparing before death is another and should be a separate issue for purposes of consent.

Some responses also questioned whether people would understand that opting in to organ donation would also mean opting in to PDPs.

The role of the doctor in PDPs was also questioned and some saw it as creating a conflict of interest:

Doctors should be concerned with prolonging the life of the patient, rather than viewing them as a source of organs.

The Law Society picked up on this point and said that careful consideration needs to be given to process and ethics otherwise it may be perceived as contradictory to the Hippocratic Oath, where the first consideration is for the health and wellbeing of the patient.1

Some also expressed distaste for the term 'pre-death procedures' and suggested another name should be found.