What's so important about health policy implementation?

This briefing has been written by Alex Wright (University of Edinburgh & What Works Scotland) during an Academic Fellowship with SPICe. The briefing reviews evidence about how health policy is implemented. Whilst the briefing focuses on alcohol policy, it may be useful for a wider range of health and public policy areas. The evidence in this briefing has drawn together key lessons about policy implementation to support scrutiny.

Executive Summary

Effective implementation is critical to the success of health policies and legislation. Even when a policy or piece of legislation is of a high-quality, incomplete implementation may lead to policy failure, resulting in unintended population health consequences and ineffective uses of public resources.

Planning for effective implementation is therefore an important consideration during the development, review, and scrutiny of policy and legislation. Based on the evidence in this briefing, a number of questions could be raised during scrutiny. These questions are broadly aligned with the themes discussed in this review.

PLANNING FOR EFFECTIVE IMPLEMENTATION: KEY QUESTIONS TO ASK DURING POLICY SCRUTINY

What ongoing administrative and leadership support will be committed for the implementation of this policy?

Is it clear from the policy (and/or associated guidance) which individuals or organisations are accountable for its activities, interventions, and intended policy outcomes? (i.e. who are the policy implementers?)

Do the individuals, organisations, or partnerships identified have the authority, legitimacy, and resources to carry out this work?

Are there clear and transparent funding mechanisms in place? Is the funding provided sufficient/sustainable for the period of time required?

What other resources beyond funding will be provided to support implementation? (e.g. training, recruitment and retention of qualified personnel)

To what extent have all or some stakeholders been meaningfully involved in formulating the policy and policy implementation plan?

Is there buy-in from these stakeholders?

Is there a plan to continuously engage with stakeholders during all aspects of policy implementation, review, and reform?

Is there a plan in place to evaluate the process and outcomes of this policy? If so, are there sufficient resources allocated to this? (Including systems to collect, collate, and use good quality monitoring data)

Is there a plan (and resources) for resulting data to be used to inform improvements?

Have (a) potential threats to sustainable implementation, and (b) potential unintended consequences of the policy been identified, and have plans been developed to mitigate these before they occur?

I. Introduction

The implementation of a policy is an integral part of the policy process.12 Once a policy has been developed, or a policy decision has been made, it must be enacted if it is to have any impact on the intended population. Even good, evidence-informed policies cannot have their intended effect if not implemented properly.

It is well known that there are a number of challenges when implementing national health policies. Evidence demonstrates that these challenges often lead policies to be enacted in such a way that they are are only implemented partially or diverge from the original aims of the policy. This can result in an ‘implementation gap’ between the policy goals and outcomes or even lead to policy failure.

In an effort to understand how policy implementation occurs and how it can be improved, a great deal of research has studied this topic. This evidence provides suggestions for policy decision-makers at national and local levels to close the implementation gap. This briefing will discuss key concepts for effective health policy implementation, with alcohol policy in Scotland presented as a key case study. Although health and alcohol policy are the focus, lessons from this review will be applicable to a wider range of health and public policy areas.

Why is health policy implementation important?

If policy implementation is ignored during policy formulation and scrutiny, stated goals and intentions of a policy, including positive population health changes, will not be achieved

Incomplete policy implementation, or policy failure, may result in unintended population health consequences and ineffective use of public resources

About this evidence review

This review has been developed in a specific effort to be useful and applicable to the work of MSPs and other stakeholders who are engaged in the task of analysing and scrutinising government policy during policy development, review, and reformulation.

This briefing is a review of evidence regarding health policy implementation. It draws on peer-reviewed journal articles and grey literature on a variety of health policy topics, including health and social care, health inequalities, disability rights, indigenous health, mental health, physical activity, obesity, and tobacco control. There is a specific focus on alcohol policy in Scotland.

What is policy implementation?

Policy implementation is what develops between the establishment of an apparent intention on the part of government to do something, or to stop something, and the ultimate impact in the world of action. 1

The above is a useful definition of policy implementation. However, as a complex concept, policy implementation has been defined differently by different researchers. When defining policy implementation, researchers often focus on particular aspects of the concept, for example:23

whether implementation occurred and if it is considered to be complete;

what was the process of implementation, and how could it be improved; and/or

whether the policy outcomes match expectations.

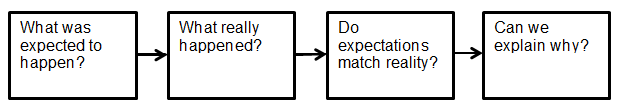

Some basic questions to ask when reviewing and scrutinising the implementation of a particular health policy may include:

II. Evidence on Health Policy Implementation

The sections below discuss key topics from existing health policy research that can act as barriers or facilitators to policy implementation.

1. Planning for Policy Implementation

Existing research confirms that planning for policy implementation is best conducted during the stage of policy formulation and scrutiny – to a certain extent, the success of implementation is a function of how the original policy or legislation is developed.12

For example, an Audit Scotland report on the integration of Health and Social Care found that although integration was expected to be operational by 1 April 2016, implementation challenges in the planning stages put this deadline at risk. Challenges such as disagreements over budgets and uncertainty over funding delayed the development of local strategic plans.3

Poor planning may lead to issues such as insufficient numbers of trained staff or resources to handle the burden of managing a new policy.4 A lack of planning may also increase the risks of unintended consequences.5 For example, a study of disability rights legislation in Sweden found that the legislation was interpreted narrowly at local level during implementation, leading to the exclusion of people with mental health problems, and government clarification about this issue was never provided.6

In terms of planning for implementation, many health policy topic areas are complex and require a multi-sectoral approach. In Scotland, the response to this has been a commitment to partnership working.7 During planning for how policy implementation will occur in partnership settings, it is advisable to consider utilising pre-existing organisational expertise. Research indicates that organisations which already conduct work on a given health topic (e.g. ‘health equity’) may be better positioned to more easily implement new initiatives on that same topic.8

In addition, the context of a local area will specifically shape how a given policy is implemented in that area – this interaction will influence policy outcomes.9 It is self-evident that one-size will not fit all. Existing evidence suggests that certain contexts can be more receptive to certain policies and approaches to implementation than others.10

Opportunities for further planning also exist during impact assessments, when the impact of policy or legislation on issues such as finances or equality are assessed.

KEY POINT: Insufficient planning for health policy implementation may lead to otherwise avoidable challenges to a policy being operationalised.

Brief example: Planning

In a study which reviewed a number of health policy initiatives in the city of Chicago in the United States, researchers found approximately 70% of initiatives had limited or no progress towards implementation. These researchers found that certain aspects of policy design acted as barriers to implementation, including: the provision of limited information on the policy problem; providing broad recommendations for implementation without specific direction; and variations in public consultation or involvement.11

2. Resources

A clear message from existing evidence is that policy implementation requires a variety of resources to support the process.1234 These include, but are not limited to financial resources, human resources, leadership, and infrastructure. A lack of necessary resources may result in incomplete policy implementation or policy failure.1

2.1 Financial Resources

The issue of financial resources is directly linked to the other themes in this briefing. For example, human resources, conducting consultations, maintaining infrastructure, and sustaining performance measurement and evaluation require financial support.

Evidence shows that a lack of, or uncertainty about, financial resources is a critical barrier to policy implementation and, vice versa, successful policy implementation relies on appropriate monetary support.1234 For example, policy implementation can be put at risk if no extra resources are made available when a new, additional policy is required to be implemented.5 Further challenges arise when policy implementers are unable to reallocate existing funding or to source new funding.6 For example, researchers investigating the implementation of a care programme for people with a dual diagnosis in England found that implementing organisations were significantly constrained in undertaking this work because of financial pressures and budget cuts.7

In light of this, there is consensus within existing literature that sufficient, dedicated, sustainable funding greatly facilitates policy implementation. 89 10 11

KEY POINT: Health policy implementation must be adequately and sustainably financed.

2.2 Human Resources and Training

The availability of skilled, knowledgeable staff is important for policy implementation.123 Ensuring sufficient numbers of staff and the right skills require additional recruitment and training for policy implementation and managing staff turnover.

A key human resource challenge is staff turnover and position instability, which can result in the loss of institutional memory and valuable experience. 35 Ways to retain staff may therefore need to be prioritised, for example by supporting policy implementers (including managers and service providers) by providing resources to advise and assist them with specific policy, legal, and regulatory processes.6

The lack of time that existing staff have to allocate to implementing a new or refreshed policy is frequently cited as a problem.7 Given that staff are often trying to cope with competing priorities at local level8, it is likely that direction and support must be given about how they should prioritise any new initiative.

There is a consensus about the need for training to equip policy implementers, particularly at early stages of policy implementation and then in an ongoing capacity. 9101112 1336 Investments in training may be required for newly created roles, for example a new category of public health professional3 or new interventions, such as the use of new naloxone kits to be used in the event of drug overdose.10

A lack of adequate training and staff capacity building is a barrier to policy implementation.71220 For example, researchers examining the implementation of a care programme in the UK found that certain social service staff were unable to access training, and that this was a challenge to the implementation process.5 In another example, local implementers of a health service in Australia felt that Indigenous health workers were not provided with adequate training (or authority) to influence decision-making in the policy implementation process.20 Taken together, this suggests that different types of training may be required in policy implementation, including a) technical content to deliver policy activities, and b) training in engaging with the policy process for broader stakeholders.

KEY POINT: The availability of skilled, knowledgeable staff who are offered ongoing training is important for health policy implementation.

Staff turnover (with associated loss of institutional memory) and position instability can be key challenges to this.

Brief Example: Training

In an analysis of the implementation of the Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005,23 researchers noted the consensus among interviewees that training had increased the knowledge and standards of practice among multiple stakeholders in the Scottish alcohol licensing system. These authors also note, however, that where training is required to facilitate policy implementation, it is helpful for it to be both mandatory and monitored to ensure it is complied with.

2.3 Leadership, Commitment, and Ideology

In addition to having sufficient human resources, it is important to consider aspects of leadership, levels of commitment, and ideologies that may influence how stakeholders undertake policy implementation.

Effective policy implementation requires ongoing support from national and regional governments and organisations, as well as relevant individuals.12 Since a lack of leadership can be a barrier to implementation, existing evidence suggests identifying and supporting local and regional leaders (or “champions”) to drive implementation processes.34 56 These leaders can provide guidance on what policy activities are valued and can influence the general culture towards a policy topic (e.g. beliefs surrounding domestic violence).7

Buy-in from local or 'front-line' policy implementers, target populations (and their representatives), and commitments from third sector organisations are also important.7 9 For example, if local staff believe a given policy initiative is too broad, their implementation efforts to enact it may be lessened.2 In a study of community nursing policy in Scotland, researchers found nurses did not feel ownership over the policy or the changes that were being implemented – this manifested as resistance to the policy.9

Getting sufficient levels of commitment and buy-in for policy implementation may require incentives to get staff to engage in the process.5 It can also be enhanced by engaging with staff and stakeholders from the beginning of policy development, as discussed below.

It will also be important to consider the ideologies of those who will need to implement the policy. Maycraft Kall (2014)13 discusses the role of government and key organisations in shaping the ideology surrounding policy and legislation – that it is not just the ‘letter of the law’ that matters, but also the ‘spirit’ of it, something that is signalled by the national government.

For example, ideologies of practitioners who ultimately deliver a policy will influence how that policy is represented to the public who access the policy's associated services. An example of this is highlighted by O’Sullivan (2015),14 who discusses the work of practitioners who deliver health services to Indigenous Australians. The authors observe that practitioners exercise discretion in service delivery, and make choices about the care that is made available to particular client groups. These choices are influenced by personal political values, such as perceptions of their client groups, and can have a significant impact on how that service is experienced by service users.

KEY POINT: Health policy implementation requires commitment from people in leadership positions, buy-in from all relevant stakeholders, and consideration of the values and ideologies of those who will implement the policy.

Brief Example: Leadership

Researchers examined Primary Stroke Care policy implementation in four US States (Florida, Massachusetts, New Mexico, and New York).6 Over 100 interviews were conducted with policy stakeholders, and in all States interviewees talked about the importance of ‘champions’ for successful policy implementation.

The researchers state: “These champions often have varying backgrounds with experience in areas, including politics, public administration, and clinical expertise; the champions all possess knowledge of policy processes and knowledge regarding ways to influence widespread support for improved stroke care.” (p. 564)

In this case study, it was argued that policy implementation was facilitated by the ability of these champions to motivate and focus stakeholders on key issues, coordinate several public health agencies, and take into account health care regulation issues.

2.4 Infrastructure

Infrastructure for policy implementation can include specific equipment such as IT systems or organisational structures such as partnerships.

In terms of the role of IT infrastructure, the ability to collect and share data is an important facilitator to policy implementation and ongoing learning. Vice versa, a lack of fit-for-purpose IT systems can hamper implementation efforts.1 It is therefore important to establish systems that support the collection, synthesis, and utilisation of data. For example, in a study on primary stroke care, researchers found that policies may be more readily implemented if data can be accessed and shared among all appropriate organisations and service providers, and that the ability to share patient data when required enhanced staff collaboration across the continuum of care.2 The importance of the use of data, monitoring, and evaluation in policy implementation is discussed in more detail below in the section on evaluation.

Appropriate IT systems can also support communication and coordination across the wide range of organisations and stakeholders involved in a given policy’s implementation.2 This may include communicating within and across systems of multi-sectoral partnerships which are a key delivery structure for delivering health policy.4

If partnership working is an important aspect of a policy's delivery infrastructure, developing positive personal relationships within and across partnerships can enhance policy implementation. However, in addition to personal relationships, formal partnership agreements are also useful tools to support effective partnership working.5 In relation to variables mentioned above, strong leadership, sufficient resources, and highly committed and competent staff also facilitate health policy implementation through partnerships.5 4

As a final note in this section, a potential benefit of partnerships developed between health/non-health organisations and other policy stakeholders is that they have the potential to assist local policy implementers to be responsive to local contexts and needs.8

KEY POINT: It is critical that the implementation process of a health policy has the infrastructure to support:

(a) the collection, synthesis, and utilisation of data; and

(b) communication and coordination within and between organisations.

3. Stakeholder Engagement

Evidence suggests that relevant populations should be included in policymaking processes at legislative and regional levels to help reduce policy implementation gaps.123

However, it appears that brief, one-off consultation of target populations does not guarantee more effective policy implementation. It is suggested that interactions with the target population and other key stakeholders should cover the entire policy process, from the time a policy problem is identified to policy implementation.4 Stakeholder engagement can help develop a shared understanding of policy goals and the kinds of solutions that can progress towards achieving them.5

In terms of best practice, the literature suggests that policymakers engage in meaningful involvement and discussions with other policy stakeholders.4 During this, specific policy measures should be elaborated in detail so that the target population has an opportunity to consider them, and co-produced agreements about specific recommendations can be developed.4

As examples from existing evidence, a study of Indigenous health policy in Australia highlighted the need for the target population to be involved at the policy formulation stage at all levels of government.8 The authors advocated for increased participation of health organisations controlled by Indigenous communities in the policymaking process.8

Similarly, another study examined a large federal nutrition programme in the United States, highlighting the importance of public health practitioners and policymakers engaging with the target client group, in order to learn from one another during the policy process.10

As a final example, researchers studying the implementation of a new policy to provide take-home naloxone kits in the United States found there was limited implementation of the initiative. They found that a key barrier to implementing the new policy was the lack of input from frontline health-care staff to the policy development process - it was perceived that the people who developed the policy did not understand the unique challenges faced by those who would be implementing it.11

KEY POINT: Meaningful involvement of relevant stakeholders and target populations in the entire policy process can help reduce policy implementation challenges.

4. Implementation Guidance and Ongoing Communication

Identification of, and communication with, responsible parties are important tasks in policy implementation. A lack of clear guidance about implementation expectations and responsibilities for policy actions can present a significant challenge from the start of implementation.1 23

In acknowledgement of the complexity of the policy implementation process, there is a need to balance the decisiveness of implementation guidance with flexibility given to local implementers. For example, certain specific public health interventions must be delivered by trained professionals. However, allowing local policy implementers the flexibility to decide how to make this happen and to render services appropriate for local needs, may be a facilitator to implementation.4

Poor communication can hamper policy implementation. There is a risk of poor communication when, for example, policy implementation requires transmission and interpretation of nuanced ideas across different levels of governance or during integrated working among numerous organisations.5 For example, a study on community nursing services in Scotland found that a barrier to shifting care out of hospitals into the community was poor communication between the hospital and community settings.6 Supporting local implementers to communicate and share practices is also noted as a facilitator of implementation.7 As discussed previously, infrastructure such as IT services may facilitate communication.

KEY POINT: Health policy implementation can be facilitated by the development of clear guidance about expectations and the distribution of responsibilities for policy actions.

This guidance will be enhanced by also building in certain flexibilities for local policy implementers to adapt to local needs.

Brief Example: Guidance and Communication

Forbes et al. (2010) conducted a comparative study of health and social care policy implementation in England and Scotland. The researchers observed that in England, guidance published late led to challenges in governance and accountability, while in Scotland, existing guidance was criticised for its lack of a clearly articulated role for Councils within Health and Social Care Partnerships.8

5. Organisational Culture

Organisational culture is important for policy implementation because implementing agencies have significant amounts of autonomy, and are not entirely under administrative control.1 In addition, organisations are increasingly expected to work effectively in partnerships with other organisations that may have different values, priorities, and perspectives from their own.1 These factors influence how organisations will interpret and undertake policy implementation. For example, organisational resistance to change, lengthy decision-making processes, risk avoidance, and lack of coordination among service providers can be barriers to implementation.3

When an organisation has been identified as the one responsible for implementing a health policy, it may be beneficial to develop or adjust organisational structures (e.g. working groups or steering committees), so that the health policy will be prioritised and given legitimacy within that organisation.4

To support policy implementation, international literature suggests that breaking down organisational silos can facilitate cross-organisational networking, and that planning for this should occur during policy development.4 This may be a key lesson for the Scottish context in which partnership working is prevalent. In this context, it is also worthwhile to consider how best to facilitate the building of strong organisational relationships and trust between partners.6

KEY POINT: Planning for health policy implementation can be improved by considering the organisational culture(s) of the organisation(s) who will be involved in the implementation process.

Brief Example: Organisational Culture

A study examined a Canadian public health initiative which created new nursing roles. These new roles were focused on ‘health equity’ and were located in regional Public Health Units across a Canadian province.

Within each Unit, senior leadership made decisions about the early development of this new nursing role, including the scope of these nurses’ new remit and where the role would be placed in the organisational structure of the Unit. As a result, a key issue arose: a lack of consistency in how the new nursing role was positioned across Public Health Units. This in turn affected key elements of the overall initiative’s implementation, including the decision-making power of these new nurses, their level of independence, and how accepted they were by public health colleagues.

However, the same study found that a benefit of this flexible and adaptive approach was that the Units could learn and adapt to changing needs.4

6. Accountability

Accountability for enacting policy was found to be an important aspect of policy implementation quality and effectiveness.12

A key barrier to policy implementation is a lack of clear understanding among both policy-makers and policy implementers about the distribution of responsibilities. This issue is made more complex when policies are intended to be implemented through local partnership arrangements. In an Audit Scotland report on health and social care integration, a key recommendation of the authors was to:

set out clearly how governance arrangements will work in practice, particularly when disagreements arise. This is because there are potentially confusing lines of accountability and potential conflicts of interests for board members and staff.3

A remedy for this issue, as suggested in this quote and the above section on guidance, is the development of clear, complete regulations that are disseminated and explained in advance of policy implementation. If clear guidance exists, accountability measures and enforcement mechanisms that are well-defined and formally agreed can help ensure further clarity on roles and responsibilities4, and therefore may enhance progress towards implementation goals. In addition, similarly to the section on guidance, building a certain amount of flexibility into these agreements may help policy implementers take account of learning and, as a result, adapt implementation to changing local needs.4

Accountability agreements are likely to be more effective if, within them, explicit links are drawn between government goals/mandates and actions planned for local implementation.4 Meanwhile, a lack of incentives encouraging compliance or a lack of sanctions for non-compliance, and voluntary uptake of a policy, may be barriers to implementation.78Enforcement of accountability may overlap with the monitoring and evaluation of policy implementation, discussed below (e.g. Allison et al. 20169).

Another barrier to policy implementation can emerge when a new policy conflicts with other existing regulations and responsibilities.10 For example, a study of health and social care policies in England and Scotland found that implementation was hampered by implementers’ difficulties in combining local and national performance measurement targets.11

Finally, those tasked with policy implementation and held accountable for it must be provided with adequate political support and authority to undertake this work.12

KEY POINT: Accountability mechanisms surrounding a policy's implementation can be improved by:

(a) co-producing (with relevant policy stakeholders) clear agreements about responsibilities for implementation activities; and

(b) aligning responsibilities for the new policy with existing responsibilities.

7. Monitoring and Evaluation

It is important to measure and analyse the progress of policy implementation in order to know to what extent it has occurred, what successes or challenges have been experienced, and to learn from these experiences. The implementation factors discussed above can be considered and incorporated into policy planning and formulation, however it will be impossible to anticipate or completely control all aspects of implementation.1

Therefore, a process of learning, and the capacity to continuously monitor and evaluate policy implementation, is necessary. Monitoring and evaluation is linked with the factors discussed above. For example, resources, staff capacity, and IT infrastructure must exist in order to reliably collect, synthesise, learn from, and use monitoring data and knowledge. In addition, it is recommended that planning for evaluation of implementation should be built into a policy during its development, and any core data set(s) for monitoring are agreed upon prior to policy implementation.

In Scotland, the commissioning of the Monitoring and Evaluating Scotland’s Alcohol Strategy (MESAS) programme (discussed further below) is an example of a large portfolio of work dedicated to this task.

There is a consensus in the literature about the need for monitoring and evaluation. As an example, in a US-based study on school wellness policies, researchers found that a barrier to implementation was inadequate capacity and tools to conduct monitoring of the policy.2 Further, a study of children’s continuing-care in England demonstrated the usefulness of local practitioners being able to learn from the monitoring of their programme, and then deploy their capacity to adapt it.3 Similarly, a key conclusion from a Canadian study regarding palliative care was that policy implementation needed to be monitored and continuously fine-tuned.4

KEY POINT: Monitoring and evaluating a health policy's implementation is a critical, ongoing process which is necessary to measure progress and provide important learning for improvement.

Key Points on Health Policy Implementation

Planning for policy implementation should occur during policy development and scrutiny, and can support progress towards policy goals.

Planning should include consideration of: resources, training, stakeholder engagement, organisational culture, and accountability.

Policy implementation cannot be entirely controlled, so it is important to engage in continuous monitoring and evaluation throughout the policy implementation lifespan.

III. Case Study: Alcohol Policy Implementation

The process of health policy implementation is often studied using a case study of a specific health policy or programme. Alcohol policy was selected as the focus of this briefing, given the impact of alcohol-related harm in Scotland and its importance in Scottish health policy. This section first provides a review of international research surrounding alcohol policy implementation. A discussion of alcohol policy implementation in Scotland is then presented. Many of the themes from Section II of this review can be seen to emerge in this section.

What is known about alcohol policy implementation from international research?

"Successful implementation of national action requires sustained political commitment, effective coordination, sustainable funding and appropriate engagement of subnational governments as well as of civil society and economic operators. Many relevant decision-making authorities should be involved in the formulation and implementation of alcohol policies, such as the Ministry of Health and other relevant ministries, transportation authorities or taxation agencies." (WHO, Global status report on alcohol and health 2014, p. 24)1

As the examples below demonstrate, the international literature discusses a range of alcohol policies and programmes in terms of their implementation.

In a study of Irish alcohol policy, Butler (2009)2 highlights a number of challenges to policy implementation. The author argues that the political culture of Ireland prevented imposing strict alcohol control policies in the country. Further, it is argued that when the Irish government did create an alcohol policy based on a public health perspective, the policy’s action plan lacked the joined-up infrastructure necessary to implement this type of policy. It was also observed that there may have been a lack of political will to strongly advocate for the enactment of this policy.

In a systematic review, Johnson and colleagues (2011)3 synthesised international qualitative evidence on implementing alcohol brief interventions (ABI). Most articles included in this study examined ABI implementation in primary care settings. The findings from this study reflect the key themes discussed in the earlier section of this review: implementation challenges included a lack of resources, support from management, and the high workload of ABI implementers, while facilitators to implementation included access to staff training, staff involvement from policy planning stages.

D’Abbs (2004)4 describes the implementation of an alcohol programme in the Northern Territory of Australia. In the author's view, early implementation of the programme was successful because of factors similar to those discussed earlier in this review: the parliamentary authority given to the programme; the political commitments made to the programme by Chief Minister; the establishment of a Trust Fund to provide sustainable funding; establishment of intersectoral administrative capacity; and alignment of programme goals with particular interests of local alcohol industry. However, it was observed that when environments and alignments changed a few years later, support for the policy diminished and the programme dissipated.

In research from Sweden, Geidne and colleagues (2013)5 examined an alcohol policy project in football clubs. The authors found that a mix of community level factors, football club characteristics, organisational capacity, and training and technical assistance factors influenced whether clubs implemented this initiative. For example, clubs’ concern with social responsibility and engagement enhanced their participation, and meetings organised where clubs could share experiences were perceived as valuable.

In the United States, Jones-Webb and colleagues (2014)6 undertook a case study of US cities that adopted policies to restrict high-alcohol malt liquor sales. The authors observed that at every stage of the alcohol policy process, the external social, political, and economic context can influence policy actors and actions. In addition, it was observed that the following activities are important for alcohol policy implementation: building public awareness and educating stakeholders; monitoring and enforcing compliance; evaluating process and outcomes; and institutionalising the policy.

Also in the United States, Nelson and colleagues (2015)7 conducted a longitudinal analysis of alcohol policy implementation in all 50 states (and the District of Columbia) between 1999-2011. They sought to explore whether the feasibility and acceptability of different alcohol policies to the public and policymakers would be a barrier to the implementation of these policies. The authors found that, indeed, alcohol policies which were more “politically palatable” (e.g. policies targeting youth or drink driving) increased during this time period. In contrast, policies which were deemed to be the most effective for reducing adult alcohol consumption based on existing evidence (e.g. alcohol taxes, price restrictions, or outlet density restrictions), were less likely to be implemented during this time period.

Alcohol Policy Implementation in Scotland

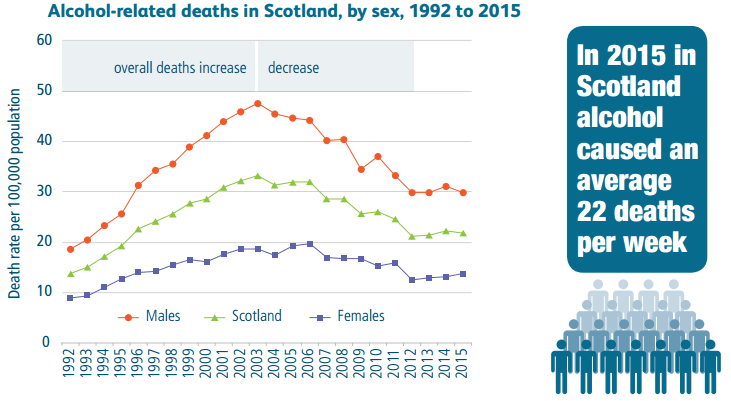

The issue of alcohol misuse in Scotland has been recognised across political parties. In June 2015 a Parliamentary debate heard a motion to both recognise the progress made thus far on tackling alcohol misuse and to push for further preventative action and additional measures to reduce the harmful use of alcohol.1 In this debate, Members of the Scottish Parliament consistently noted the continued individual and societal costs of alcohol-related harms in Scotland and the health inequalities that result.1

| Key Facts About Alcohol-Related Harm in Scotland |

|---|

|

Relevant Scottish Policy and Legislation

In 2009 the Scottish Government published Changing Scotland’s Relationship with Alcohol: A Framework for Action.1 This policy provides the core of the overall Alcohol Strategy, and has therefore been a key source of guidance for alcohol policy implementation. A refresh of the Framework for Action is expected to be published by the Scottish Government in late 2017.

During policy planning of the Framework for Action, the Scottish Government published a discussion paper on their intended strategic approach, and their subsequent consultation received 472 responses.2 This discussion paper, and the resulting policy, contained some guidance for how the policy would be implemented. For example, certain aspects of Scotland’s Alcohol Strategy are intended to be implemented locally, including those related to service provision, education, and health promotion.1 Examples include alcohol brief interventions and services for children and families. Other components of the strategy (e.g. reduction in the drink driving limit) have been implemented at national level.4

In addition to the Framework for Action, three pieces of enacted legislation contribute to the overarching Strategy: the Licensing (Scotland) Act (2005), the Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Act (2010), and the Air Weapons and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2015 (Box 1). A fourth component, the Alcohol Minimum Pricing Act (2012) is being challenged in the courts and has not yet been implemented.

Implemented Components of Scotland's Alcohol Strategy

Contains five licensing objectives, including ‘protecting and improving public health’ (this public health objective distinguishes Scotland from the UK and other countries globally1)

Changing Scotland’s Relationship with Alcohol: A Framework for Action (2009)

Takes a ‘whole-population’ with targeting approach

Four action areas:

Reduced consumption

Supporting families and communities

Positive attitudes and positive choices

Improved support and treatment

Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Act 2010

Makes provision for regulating sale of alcohol and licensing of premises.

Air Weapons and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2015

Amends legislation regarding alcohol licensing.

Stakeholders and Infrastructure

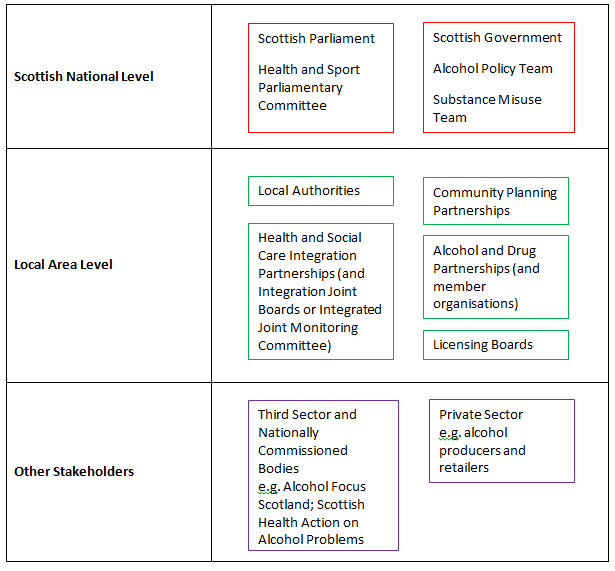

Human resources and commitment for alcohol policy implementation in Scotland comes from a range of national and local individuals, organisations, and institutions.

National stakeholders in alcohol policy and legislation include the Scottish Government, responsible for developing and delivering alcohol policy, and the Scottish Parliament, responsible for scrutinising policy.

At local level, bodies such as Local Authorities, Community Planning Partnerships (CPPs), and Health and Social Care Partnerships are relevant to the Strategy’s implementation, and each have their own organisational cultures. Local Authorities are responsible for providing services such as education, social care, and cultural services to their constituency.1 They are governed by a local Council which runs autonomously from central government.1 Local Authorities are represented nationally by the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA) and the Scottish Local Government Partnership (SLGP), which lobby the Scottish Government on their behalf.

The Local Government in Scotland Act 2003 established the statutory framework for Community Planning. The Act established 32 Community Planning Partnerships (CPPs), which service the same area as their respective Local Authorities, and are intended to ensure that local services are delivered in partnership between service providers. In addition to CPPs, the Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014 established a mandate for local authorities and Health Boards to integrate their health and social care services (also see SPICe briefing on this topic). This included a requirement to pursue either an Integrated Joint Board (IJB) (Body Corporate) Model or a Lead Agency Model of integration. Only Highland Partnership has used the lead agency model, which requires the NHS board and local authority to establish a 'joint monitoring committee'. 3IJBs have been delegated a variety of local functions, including health and social care service delivery – a function relevant to alcohol-related services.

Within this local governance structure, the delivery of local alcohol-related policy and services is the responsibility of Scotland’s Alcohol and Drug Partnerships (ADPs).4 Partners on ADPs include, but are not limited to, representatives from health and social care, criminal justice, education, and the third sector.

Guidance for how ADPs are intended to support alcohol policy implementation is contained in documents such as The Quality Principles (2014) and Updated Guidance for Alcohol & Drug Partnerships (ADPs) on Planning & Reporting Arrangements (2015).

ADPs and their local partners are expected to commission evidence-based and recovery-oriented treatment and support services for their population. They are accountable for reporting back to their local area’s CPP and Integration Authority, as well as to the Scottish Government on Ministerial priorities and targets. Core outcomes that ADPs are accountable for include those related to improving health, enhancing community safety, and supporting health-promoting local environments. A list of ADP core outcomes and core indicators can be found here.

Financial resources for ADPs are provided by the Scottish Government, via their respective local Health Boards. There was concern in the 2016/17 financial year about the implementation of 22.25% budget cuts to Alcohol and Drug Partnerships, which was expected to be covered by local Health Board budgets.5 The budget for ADPs is unchanged from 2016/17 levels for 2017/2018.67

Licensing Boards are independent regulatory bodies located in each local authority area, and are responsible for local decision-making about alcohol licensing. The relevant legislation for alcohol licensing and the actions of Licensing Boards is the Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005.

There are a range of other stakeholders involved in alcohol policy in Scotland. These include organisations such as the British Medical Association Scotland, Alcohol Focus Scotland, and the Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (SHAAP), as well as the alcohol industry.

Links to Other Policy

Alcohol-related harm is linked with a wide range of societal issues, and is therefore linked to other Scottish policies and legislation. This includes, for example, health policies and reports such as the Scottish Government's national drugs strategy, The Road to Recovery (2008) and Equally Well (2008, 2010), the report of the Ministerial Task Force on Health Inequalities. As broader public policy examples, the National Performance Framework indicates important linkages that can and should be made across Scotland’s public service sector in order to achieve identified goals for Scotland1, including health and economic considerations. Other examples include, but are not limited to, the Commission on the Future Delivery of Public Services (2011) ("Christie Commission"), The Early Years Framework (2009), Justice in Scotland: Vision and Priorities (2017) and The Strategy for Justice in Scotland (2012).

Evaluating Alcohol Policy in Scotland

Monitoring and Evaluating Scotland's Alcohol Strategy (MESAS)

In 2010 the Scottish Government tasked NHS Health Scotland with monitoring and evaluating Scotland’s alcohol strategy in order to attain evidence on the strategy’s outcomes. Along with the NHS National Services Scotland Information Services Division (ISD), NHS Health Scotland established a taskforce called Monitoring and Evaluating Scotland’s Alcohol Strategy (MESAS) to carry out this work. The MESAS work portfolio was composed of eight separate studies, which considered how the strategy might be implemented differently to improve effectiveness, how people and businesses were affected, and to what extent the alcohol strategy contributed to a reduction in alcohol-related harm. MESAS published multiple annual reports describing the progress and results of these studies, and a final report in March 2016. In this report, MESAS recommends that: "Effort is made to improve implementation of existing components of the strategy, particularly those with the potential to reduce the availability of alcohol and to incorporate the learning on implementation facilitators when developing new interventions."(p.7) 1 Certain monitoring work by MESAS is ongoing and their 2017 report can be found here.

Alcohol Policy Implementation Research

Scottish Research

In a study that was part of the MESAS portfolio of work, MacGregor et al. (2013) 1 analysed the implementation of the Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005. Their study reported that overall, the Licensing Act can be seen to have had a positive impact. As a specific example, the creation of Licensing Standards Officers (LSOs) has been perceived as successful in terms of how they have contributed to improved relations between Licensing Boards and licensed premises.

The study does, however, note challenges and facilitators for effectively implementing licensing legislation in Scotland.

Challenges include:

A lack of updated national guidance for implementing legislation;

Reported problems in interpreting the legislation; and

National and local data were not being collected/collated consistently or in a manner which allowed meaningful comparison.

Regarding the public health objective of the Licensing Act specifically, implementation has been hampered by: the lack of an adequate definition; lack of understanding about what data sources should be used or how the objective would be monitored; the ‘population-based approach’ of the objective was difficult to relate to individual alcohol outlets; and concern that legal decisions would be overturned by Sheriffs and thus decisions were made cautiously.

Facilitators of implementing licensing legislation included:

Where training was required, it was helpful for it to be both mandatory and monitored; and

Establishment of LSOs led to the perception that trade were now more likely to comply with the Act, with fewer reviews being sent to Licensing Board level.

The study also makes a number of recommendations for more effective implementation of licensing (an annotated list is provided here, please find the complete list in MacGregor et al. 2013, p xii-xiii)1:

More guidance and support be given nationally in relation to:

the public health objective

capacity and over-provision

the role and function of Licensing Forums

Any new, relevant legislation that his implemented

Consideration given to role of Licensing Standards Officers, with respect to their number, training, legal support, and capacity to collect and collate data;

Require Licensing Boards to give further consideration to the public health objective, carry out assessments of capacity and overprovision, share best practices with other Boards, and improve data collection;

Ensure licensed trade continues to undergo mandatory and ongoing training, maintains good links with LSOs, and consider measures to address public harms that result from alcohol misuse.

Consistent collection and collating by Boards and LSOs of agreed data.

In another study from the MESAS portfolio, Parkes, Atherton, Evans et al. (2011)3 specifically evaluated the process of implementing ABIs, with a focus on their mainstreaming into primary care. The authors found that the original HEAT target (now called a Local Delivery Plan [LDP] Standard), which sought to embed ABIs into regular NHS practice, was achieved in March 2011, and the authors’ assessment is that the implementation of this component of Scotland’s alcohol strategy was carried out in line with government guidance.

However, one of the authors' most significant findings was that the practical implementation of ABIs was hugely varied across Scotland.3 They particularly highlight the different payment structures for ABIs in primary care, and the ways that Health Boards contextualised the ABI programme to fit their local needs. In addition, geographical gaps in implementation remained at the time of the report’s publication, particularly in rural and remote areas. This study observed that there was buy-in among healthcare staff about the value of ABIs and the use of resources to deliver them. The authors also found that it was very important for universal systems and standards for recording to be developed for the purposes of data collection and monitoring.

It was noted that a one-year extension of specific funding and infrastructure support to continue the ABI programme was a welcome source of support, however the authors suggested that these supports will likely need to be maintained longer if ABIs are to be fully implemented into regular practice.3

In research in the broader academic literature, Fitzgerald and colleagues (2017)6 examined how the public health objective has been enacted within the context of alcohol licensing in Scotland. These researchers specifically explored how public health practitioners (including representatives from the NHS, Alcohol and Drug Partnerships, and national or third sector organisations) navigated this system since the objective was introduced as part of the Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005.

This study found that a challenge public health practitioners faced in attempting to support the enactment of the public health objective was the perception that although they were working from a ‘whole-population approach’, that this approach had not always been adopted by other licensing stakeholders. For example, interviewees in this study perceived widespread disagreement among licensing stakeholders about whether current alcohol consumption and related harms pose significant problems to Scottish society. In addition, interviewees suggested that there was a lack of consensus about whether “addressing public health was a legitimate role of licensing” (p.7). On a related note, it was reported that Licensing Boards tended to prioritise economic considerations over public health ones.6

Interviewees in this study also reported that health evidence they provided to licensing stakeholders was often not persuasive to these audiences. For example, they reported that statistical data was not perceived as trustworthy by certain Licensing Board members. However, it was noted that there may be an important role for the public in providing anecdotal and experiential evidence related to public health to communicate to actors across the licensing system.6

Finally, it was reported that building positive relationships between public health practitioners and licensing stakeholders would help with progress towards enacting the public health objective.6

In another study by Fitzgerald and colleagues (2015)10, the authors examine the implementation of ABIs. This study explored experiences of implementing ABIs in antenatal, accident, and emergency health care settings, and found that five strategies were helpful for implementing ABIs in any setting (quoted from Fitzgerald et al 2015):

Having a high-profile target for the number of ABIs delivered in a specific time period with clarity about whose responsibility it was to implement the target;

Gaining support from senior staff from the start;

Adapting the intervention, using a pragmatic, collaborative approach, to fit with current practice;

Establishing practical and robust recording, monitoring and reporting systems for intervention delivery, prior to widespread implementation; and

Establishing close working relationships with frontline staff including flexible approaches to training and readily available support.

UK Research

Two research papers from elsewhere in the UK discussed the issue of alcohol policy implementation, and their findings are relevant for consideration.

Martineau and colleagues (2013)11, writing about alcohol licensing from a public health perspective, argue that the lack of a ‘public health objective’ in England and Wales constrains local actors’ ability to address alcohol-related health harms. The researchers note that, despite this, public health advocates can still seek to influence licensing decisions, for example by providing evidence that links alcohol outlet density to drinking behaviour (and how this relates to issues like crime and anti-social behaviour). This work can be supported by national level actors through the development of resources such as evidence reviews, evaluation tools, and case studies of best practice.11 Although Scotland does have a public health objective for licensing, evidence suggests it is not currently being implemented sufficiently,6 therefore these types of supports would likely still be useful in the Scottish context.

In another UK-based study, Thom and colleagues (2011)14 provide an overview of partnership working in England with respect to alcohol policy implementation. This study found a clear shift to using partnership approaches to delivering alcohol policy, which was perceived as both positive and necessary by the study participants. The authors also found that ‘buy-in’ and commitment from those in leadership positions, as well as alcohol ‘champions’, were key factors in the success of these partnerships to conduct alcohol policy implementation. A number of challenges were noted however, including (annotated from Thom et al. 2011, p.60-61):

the need to manage cuts in resources, often in the face of increasing demands and existing tensions around prioritising aims and targeting resources;

Difficulties establishing shared priorities and goals among partners, which was influenced by the level of trust between partners, and the quality of communication and information sharing;

The need for commitments from ‘top people’ to ensuring alcohol was part of local planning agendas;

The need to change professional behaviour to move away from ‘siloed’ working;

Managing the size and complexity of the partnerships, and their relationships to the rest of the local system; and

The need to respond to local needs, especially in rural areas.

Summary Points

Effective implementation is critical to the success of health policies. If policies are not implemented, then policy goals and outcomes cannot be achieved

Planning for effective implementation is therefore an important consideration during policy development and scrutiny

A number of facilitators exist which can enhance the policy implementation process, and if absent, policy implementation can face critical challenges. These include, but are not limited to:

Considerable commitment and leadership

Meaningful involvement of local policy stakeholders, members of the target population, and other stakeholders in policy planning and development

Adequate, sustainable resources

Consideration of factors such as competing strategic/governmental priorities (e.g. public health versus economic growth) to mitigate unanticipated consequences

Appropriate accountability mechanisms

Ongoing monitoring and evaluation of policy implementation, and the application of this learning