Scotland Act 2016: industrial injuries benefits and severe disablement allowance

Responsibility for the current reserved industrial injuries benefits and severe disablement allowance is devolved by the Scotland Act 2016. This briefing explains the entitlement conditions for these benefits and their history. It examines the current Scottish caseload of both, and how this has changed. It looks at the Scottish Government's proposals for the future of these benefits.

Executive Summary

Industrial injuries benefits and severe disablement allowance (SDA) are amongst the social security benefits devolved by the Scotland Act 2016.

There was little debate about these benefits during the passage of the Scotland Act 2016. The Social Security (Scotland) Bill makes provision to replace industrial injuries benefits with employment-injury assistance, and severe disablement allowance will be a type of disability assistance.

The detailed rules for both benefits will be set out in regulations, although the Scottish Government may leave the existing SDA regulations in force. Until a provision of an act of the Scottish Parliament relating to these types of assistance comes into force, the Scottish Ministers cannot amend the rules governing the current benefits.

Industrial injuries benefits act as a form of no-fault compensation for employees who have had an industrial accident, or contracted one of a list of industrial diseases due to working in a listed occupation. The list of industrial diseases is monitored by the statutory Industrial Injuries Advisory Council.

The main current industrial injuries benefit is industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB), to which extra amounts can be added for people assessed as 100% disabled, who also need help from another person due to their disablement. New claims can still be made for reduced earnings allowance, but only for accidents before 1 October 1990 or diseases contracted by that date. An existing reduced earnings allowance award can convert into an award of retirement allowance. Other historical industrial injuries benefits are still paid to some people, even though new claims can no longer be made for these benefits.

The industrial injuries benefits caseload is falling over time, as is the real-terms expenditure on it, which the Scottish Government estimates will be £86 million in 2017-18. By the time industrial injuries benefits are devolved, it estimates that there will be around 29,000 people receiving them.

SDA is a benefit for people who are unable to work, and who do not have a complete National Insurance contribution record. It was closed for new claims in 2001. Most claimants will be transferred to employment and support allowance before it is devolved. Those who will remain on the benefit are mostly people over 65 with long term disabilities, who are not entitled to a full state pension. In November 2016, 2,430 people in Scotland over the age of 65 still got SDA.

The Scottish Government does not plan to make any changes to SDA, except to increase the amounts paid annually. It has not yet made any firm decisions about the future of industrial injuries benefits, and is focusing on the transfer of existing claimants. One thing being considered is how to replace the functions of the Industrial Injuries Advisory Council in the devolved social security system.

Abbreviations used in this briefing

CAA - constant attendance allowance

DWP - Department for Work and Pensions

ESA - employment and support allowance

IIAC - Industrial Injuries Advisory Council

IIDB - industrial injuries disablement benefit

NI - National Insurance

REA - reduced earnings allowance

SDA - severe disablement allowance

The Scotland Act 2016 and the timing of devolution

Severe disablement allowance (SDA) and industrial injuries benefits were amongst a number of benefits recommended for devolution by the Smith Commission.1 With the exception of the addition of a definition of "relevant employment" for industrial injuries benefits, the UK Government's draft clauses devolving these benefits2 were identical to those eventually enacted as s.22 of the Scotland Act 2016.3 There was no significant debate about the provisions which will devolve these benefits during the passage of the Bill. Annexe A of this briefing sets out part of Schedule 5 of the Scotland Act 1998, showing the amendments made by s.22 of the Scotland Act 2016 relating to industrial injuries benefits and SDA.

SDA and industrial injuries benefits are amongst those benefits which are being devolved using a novel "split competence" approach. This is explained further below.

Split competence

The concept of split competence separates "legislative competence" (needed for the Scottish Parliament to legislate in a particular area of law) and "executive competence" (powers devolved to Scottish Ministers to deliver a particular social security benefit or make changes to its entitlement conditions, for example). This approach to some of the social security benefits recommended for devolution by the Smith Commission was agreed by the UK and Scottish Governments.

Further details of the concept of split competence are set out in the Annex to a letter from the Cabinet Secretary for Communities Social Security and Equalities to the Convener of the Social Security Committee, dated 22 November 2016. The Cabinet Secretary explained the need for split competence as follows.

The implementation process for our devolved Scottish social security system will require the Scottish Parliament to hold legislative competence for a while before we have responsibility for delivery, as we will need time to have the mechanisms, the delivery process and our agency up and running.

Scottish Government. (22, November 2016). Letter from Angela Constance MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Communities, Local Government and Equalities to Sandra White MSP, Convenor of the Social Security Committee. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/S5_Social_Security/General%20Documents/social_security_committee_221116.pdf [accessed 29 June 2017]

In terms of legislative competence, s.22 of the Scotland Act 2016 was brought into force on 17 May 2017, by The Scotland Act 2016 (Commencement No. 5) Regulations 2017.2 However, these regulations are subject to The Scotland Act 2016 (Transitional) Regulations 2017 (“the Transitional Regulations”).3 Essentially, the Transitional Regulations provide that the Scottish Government cannot make changes to a benefit listed in s.22 until the day on which an Act of the Scottish Parliament making provision for that kind of benefit comes into force. If no such provision has come into force by 1 April 2020, executive competence will transfer to the Scottish Ministers on that date.

The Social Security (Scotland) Bill4 ("the bill") was introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 20 June 2017 by the Cabinet Secretary for Communities, Social Security and Equalities, Angela Constance MSP. The bill sets out a framework for a new Scottish social security system will operate, including for different types of "assistance". Different sections of the bill make provision for "employment-injury assistance" and "disability assistance". The commencement of these sections will give Scottish Ministers executive competence for industrial injuries benefits and SDA.

For more details on the provisions in the bill see the forthcoming SPICe briefing The Social Security (Scotland) Bill.

Severe disablement allowance

The fact that severe disablement allowance (SDA) is closed to new claims led Gullard (2015) to question whether the Smith Commission had really intended to devolve SDA at all. She suggested that may have intended to recommend that exceptionally severe disablement allowance (an addition to industrial injuries disablement benefit - see above) be devolved.1

The UK Government white paper Scotland in the United Kingdom: an enduring settlement confirmed the devolution of SDA for existing claimants at the point of transfer. It described the devolved power as follows:

4.3.4 ... The Scottish Parliament will have the power to create new benefits or other payments to replace SDA for those claimants should they wish and the autonomy to determine the structure and value of this provision, as per paragraph 54 of the Smith Commission Agreement.

Scotland Office. (2015). Scotland in the United Kingdom: An enduring settlement. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/397079/Scotland_EnduringSettlement_acc.pdf [accessed 25 April 2017]

The draft clauses which accompanied this white paper defined "severe disablement benefit" paid to a "relevant person" as a proposed new exception to the general reservation of social security powers. With the exception of a change in the numbering of the sections, identical definitions were eventually enacted. During debates on the bill which became the Scotland Act 2016, no amendments to this definition were selected for debate.

Industrial injuries benefits

The Smith Commission's report listed "Industrial Injuries Disablement Allowance"1amongst the social security benefits to be devolved. This is not the name of any of the existing industrial injuries benefits.2 Paragraph 179 of the Explanatory Notes to the Scotland Act 2016 make clear that the Act is intended to devolve:

Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit; Constant Attendance Allowance; Exceptionally Severe Disablement Allowance; Reduced Earnings Allowance; Retirement Allowance; Unemployability Supplement; Industrial Death Benefit; Industrial Injuries Disablement Gratuity and Hospital Treatment Allowance

Explanatory Notes to the Scotland Act 2016 c. 11. (2016). Retrieved from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2016/11/notes/division/1/index.htm [accessed 29 April 2017]

When the bill, eventually enacted as the Scotland Act 2016, was introduced in the UK Parliament, the draft clauses previously published in the white paper Scotland in the United Kingdom: an enduring settlement2 had been amended to insert a definition of "relevant employment". In addition to excluding self-employed people, this definition ensures that people whose employment is illegal could be entitled to industrial injuries benefits after devolution. Illegally employed people can currently qualify for reserved industrial injuries benefits, at the DWP's discretion.5

The clauses relating to industrial injuries benefits were not amended during the passage of the bill.

Industrial injuries benefits before devolution

Industrial injuries benefits in broadly their current form were introduced in 1948, replacing the previous workmen's compensation schemes. They are reserved benefits, paid by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), if an employee becomes disabled as a result of:

an accident at work, or

a disease linked to a specific occupation.

Industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB) is the main current industrial injuries benefit. There are a variety of additions to IIDB, explained below. There are other historic industrial injuries benefits that some claimants may still be receiving. It is no longer possible to make a new claim for some of these.

People who have an accident at work or get a disease due to their job may also be able to claim compensation from their employer. This is separate from the social security system, so can be claimed in addition to industrial injuries benefits. There is more information about compensation for personal injuries on the Citizens Advice Scotland website.1 The DWP can recover the value of industrial injuries benefits from some kinds of compensation payments.2

The primary legislation governing the industrial injuries benefit scheme was consolidated in the Social Security Contributions and Benefits Act 1992.3 Further detail is set out in secondary legislation, including detailed provisions in The Social Security (General Benefit) Regulations 19824 and The Social Security (Industrial Injuries) (Prescribed Diseases) Regulations 1985.5

The following sections explain the current industrial injuries benefits system and the Scottish caseload.

Industrial injuries disablement benefit - entitlement conditions

Industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB) is the main current industrial injuries benefit. It is paid to people who are employees, certain types of volunteers and (since 2013) some trainees.i Self-employed people cannot get IIDB. Some groups, including taxi drivers and agency workers, are treated as employees.2 Disputes about employment status are decided by Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs, and the DWP has the discretion to treat someone who is illegally employed as an employee.

Industrial injuries benefits are not taxable or means-tested, and the claimant does not need to have paid National Insurance contributions to qualify.3 People who qualify for IIDB are able to work without their benefit being affected. There is normally a 15 week waiting period (90 days, not including Sundays) after an accident or the onset of a disease before a claimant can qualify for IIDB. Claims for IIDB can be backdated by up to three months.

There are no residence or presence tests for IIDB, although entitlement for people who have moved within the European Economic Area may be affected by European Union rules on co-ordination of social security schemes.ii However, the additions to IIDB set out below and other industrial injuries benefits are subject to residence conditions.2

To qualify for IIDB, the claimant must:

have suffered an injury to body or mind resulting from an "industrial accident" or a "prescribed industrial disease";

have a "loss of faculty" resulting from that accident or disease; and

be assessed as having a "disablement" above the threshold level, resulting from that loss of faculty.

These terms are explained further below. The amount of IIDB depends on the level of disablement, which is expressed as a percentage.

Additions to IIDB

Several additions to IIDB can be paid to qualifying claimants. For recent injuries and accidents these are the following (both of which require a disablement assessment of 100%, and extra conditions to be satisfied):

constant attendance allowance (CAA) – paid at four rates, depending on the amount of help the claimant needs from someone else as a consequence of their disablement

exceptionally severe disablement allowance – paid if a person gets one of the higher two rates of CAA and is likely to need the help permanently.

These additional payments mean that the weekly amount of IIDB can vary from £33.94 to £373.40 (April 2017 rates). For details of the rates of IIDB, see below.

Industrial injuries disablement benefit - key concepts

This section gives a brief explanation of some of the concepts that are relevant to qualifying for industrial injuries disablement benefit. These are complex legal concepts, and have generated a significant amount of caselaw over the years. More detailed information can be found in CPAG (2017) Welfare Benefits and Tax Credits Handbook 2017/18,1 Greaves (2017) Disability Rights Handbook (Edition 42)2 and DWP (2017) Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefits :Technical Guidance.3

Industrial accidents

Whether someone has had an industrial accident may be clear-cut, for example if an employee is obviously injured in an accident at work. However, the concept of an accident at work has been interpreted by various court and tribunal decisions to include things that are not obviously accidents. For example, stress as a result of verbal harassment at work could potentially count as an industrial accident.1 An accident can be distinguished from a "process" - which does not give rise to entitlement to industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB). An example of a process might be working for many years as a manual labourer and developing back problems as a result.2 Some conditions which are strongly linked to a particular type of work can count as an industrial disease instead.

For an accident to count as an industrial accident, the person's employment must have contributed in some way to the accident, and also it must happen as a result of someone doing some aspect of their job. An accident (such as a heart attack) may not count if there is no connection to someone's employment, and it was equally likely to happen whether they were at work or not. However, this is not always clear, if someone is injured by the employer's property during a heart attack, for example.1

Complex rules have evolved covering the following situations, amongst others:

Someone who is predisposed to an accident due an existing condition (eg an asthma attack provoked by an escape of chemicals).

An accident which happens whilst travelling to, from or for work.

An accident which is caused by someone else's misconduct.

Accidents which happen whilst the claimant was responding to an emergency situation at work.1

Prescribed industrial diseases

Industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB) can be paid to people who have one of over 70 different "prescribed industrial diseases" due to working in a particular type of job. These are conditions that the Industrial Injuries Advisory Council (see below) has identified as significantly more likely to occur if someone has a particular type of job. The DWP produces a list of conditions and types of occupation that the claimant must have been employed in to be entitled to claim industrial injuries benefits.1 This is also set out in the regulations.2 Unlisted diseases or those caused by work in an occupation not prescribed for the disease cannot help someone to qualify for IIDB. But catching an unlisted disease may count as an industrial accident, depending on the circumstances.3

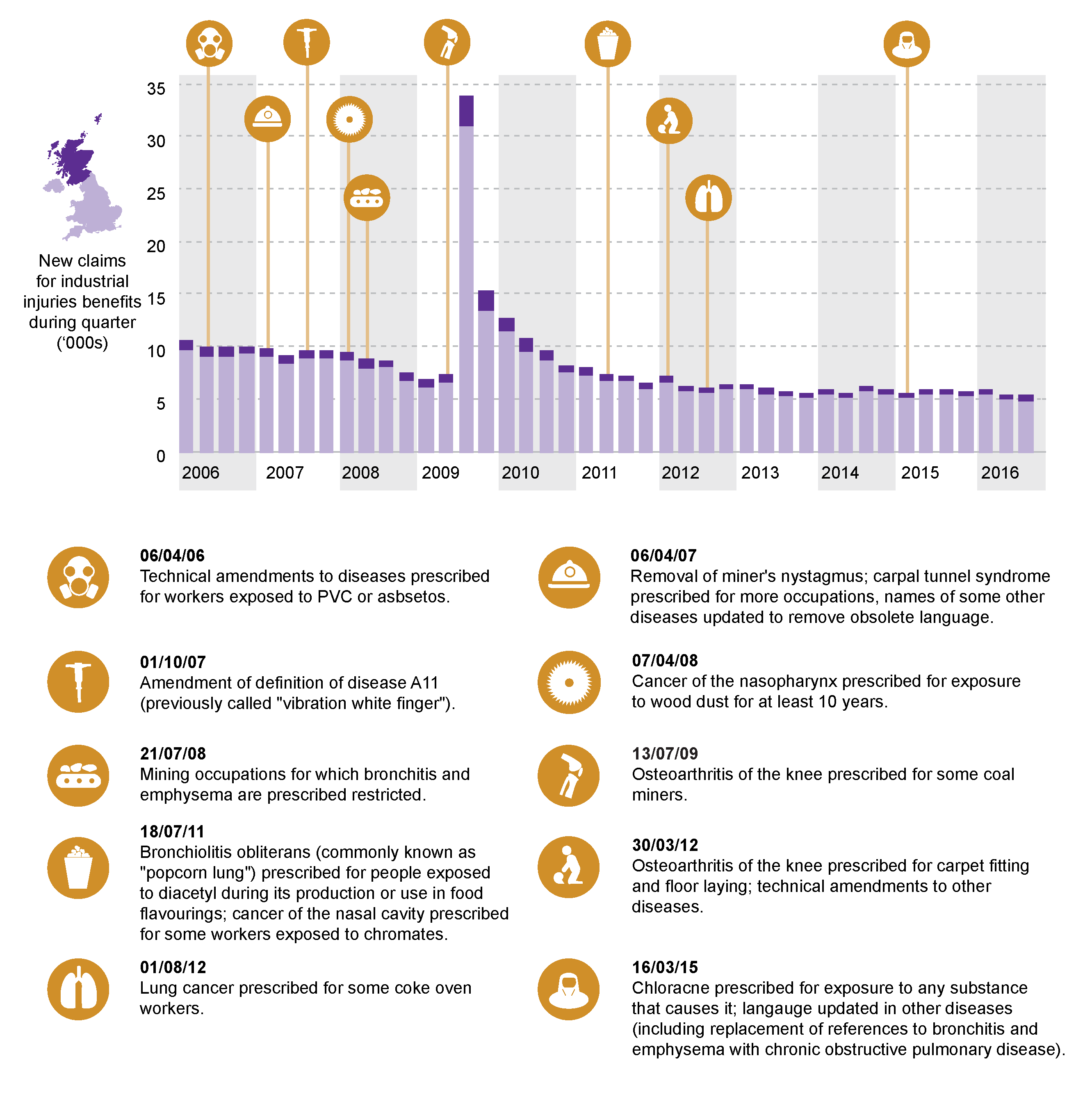

Figure 1 below shows the changes to the list of prescribed diseases between the start of 2006 and September 2016, and the number of new claims made in Scotland and the UK per quarter.

The only change during this time period that had a significant impact on the number of new IIDB claims was the prescription of osteoarthritis of the knee for miners in 2009.

A further change introduced a new prescribed disease, extrinsic allergic alveolitis, from 30 March 2017.6

For some conditions there are additional rules about the length of time that the employee must have been employed in the occupation, or a time limit for making a claim after stopping work in that job. For example:

occupational deafness requires at least ten years of employment in one or more of the listed occupations, and IIDB must be claimed within 5 years of last working in one of the occupations

cataract requires at least five years in one or more of the listed occupations

claims for occupational asthma must normally be made within 10 years of the claimant last working in one of the listed occupations.

Some diseases must appear within a certain time of stopping work in an occupation to be assumed to be caused by the work. Others are assumed to be caused by the work, no matter when they develop. For other diseases, decisions are made on the balance of probabilities. 7

Loss of faculty, disability and disablement

"Loss of faculty", in terms of industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB), is essentially the damage or impairment to body or mind caused by a disease or accident. It can also include disfigurement, even if that does not cause any functional impairment. "Disability" is the inability to manage something that someone of the same age and sex whose physical and mental condition is normal could do, due to a loss of faculty. The level of "disablement" (upon which the amount of an IIDB award depends) is the total of the disabilities caused by the claimant's industrial accidents or diseases, expressed as a percentage. The assessment process is explained below.

Assessment of disablement for industrial injuries disablement benefit

In the context of industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB), "disablement" is the combined effect of all of the claimant's disabilities resulting from industrial accidents or prescribed diseases. It is expressed as a single percentage, which determines the amount of benefit paid.

For some conditions, particularly amputations or sensory loss, the law sets a "prescribed degree of disablement" (although this can be adjusted in a particular case if appropriate). The DWP produces a list of the prescribed degrees of disablement.1 Percentages on this list can be used as a reference point when assessing the degree of disablement caused by unlisted disabilities.2

An assessment of disablement compares the claimant's loss of function with the physical and mental condition of a person of a similar age and sex without any loss of faculty or disability. It also takes account of how the condition affects a particular person. For example, a condition might have a different disabling effect on someone who is already blind, and whether the claimant is right- or left-handed could also be important.

Offsets and the effect of multiple disabilities

The percentage assessment can be reduced (called an "offset") if there is another cause of the disablement unrelated to an industrial injury. For example, someone who lost a hand in an industrial accident might have their assessment reduced if they had previously lost two fingers of the same hand in another accident unconnected to their work.

The interaction between two or more different disabilities resulting from different accidents or diseases can also result in an assessment that is not the same as simply adding together the percentages for each disability. The effect of a condition that develops later can also sometimes be added, if it increases the disablement caused by an accident or injury.

Length of assessments

Assessments can be made either for a fixed period, or for life. The length of an assessment period depends on the likelihood of change to the disablement over time. An assessment of a fixed period could be provisional, if it is not clear how long the disablement will last, or final, if it is expected that by the end of the fixed period there will no longer be any affect of the industrial accident or disease. A decision on the length of this period can be challenged.2

Assessments are carried out by one or two healthcare professionals approved by the DWP. They can also ask for additional information from a hospital that treated the claimant or their GP. The report of the assessment is sent to a DWP decision maker, who is responsible for deciding whether to award IIDB, and if so how long for.1 A claimant can challenge the decision about the amount of IIDB, or the length of an award.

Rates of industrial injuries disablement benefit

To qualify for industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB), a claimant must normally be assessed as at least 14% disabled. This percentage can be reached by adding together the disabling effects of different accidents or diseases. An assessment of 14% or more is rounded up to 20%. All assessments are rounded to the nearest 10%. IIDB is then paid at one of the weekly rates shown in Table 1 below.

| Level of disablement | Amount paid (weekly) |

|---|---|

| 100% | £169.70 |

| 90% | £152.73 |

| 80% | £135.76 |

| 70% | £118.19 |

| 60% | £101.82 |

| 50% | £84.85 |

| 40% | £67.88 |

| 30% | £50.91 |

| 20% | £33.94 |

Claimants who are assessed as 100% disabled may also qualify for constant attendance allowance and exceptionally severe disablement allowance. The rates of these are shown in Table 2 below, and more details of the entitlement conditions are set out above.

| Addition | Weekly amount |

|---|---|

| Constant attendance allowance part time rate | £33.95 |

| Constant attendance allowance standard rate | £67.90 |

| Constant attendance allowance intermediate rate | £101.85 |

| Constant attendance allowance higher rate | £135.80 |

| Exceptionally severe disablement allowance | £67.90 |

Industrial injuries disablement benefit and other benefits

Industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB) can be paid in addition to other social security benefits, and is taken into account when calculating a claimant's entitlement to means-tested benefits. However, the additional amounts of IIDB called constant attendance allowance (CAA) and exceptionally severe disablement allowance are ignored when calculating entitlement to means-tested benefits.

Whilst IIDB can be paid at the same time as any other non-means-tested benefit, CAA cannot normally be paid at the same time as any of the following other benefits (which are also being devolved):

attendance allowance

disability living allowance care component

personal independence payment daily living component.

CAA cannot be paid at the same time as some war pensions and armed forces compensation payments, which will remain reserved. These are known as "overlapping benefit" rules.

IIDB can also act as a passport to some lump sums payable to people who have certain conditions (see Annexe A) as a result of exposure to asbestos.1 These lump sum payments will remain reserved.2

Other industrial injuries benefits

In addition to industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB), it is also still possible to make a new claim for another industrial injuries benefit called reduced earnings allowance (REA). To qualify the claimant must have had an accident or suffered from a disease before 1 October 1990. Also, to claim REA on the basis of an industrial disease, that disease must have been listed in the regulations before 10 October 1994.

Claimants who meet these conditions can still make a new claim and qualify for REA if they are unable to follow their regular occupation (or one "of an equivalent standard") and are at least 1% disabled. Disablement is assessed in the same way as for IIDB (see above). Payment depends on the amount by which the claimant's earnings have reduced, up to a maximum of £67.88 a week (2017-18). There is also a maximum total award for claimants getting both REA and IIDB.1

Retirement allowance is a reduced rate of REA for those claimants over pension age who have given up regular employment. It is only possible to qualify for it if the claimant previously got REA. The amount is the lower of £16.97 a week or 25% of the previous REA award.1

Some people may still be getting other historical industrial injuries benefits, even though they have since been abolished for new claims. These include:

unemployability supplement

industrial death benefit

industrial injuries disablement gratuity

hospital treatment allowance.3

Who gets industrial injuries benefits

The number of industrial injuries benefit claimants is decreasing, as is the real terms expenditure on them in Scotland. Most claimants are men, and most new claims are made by people of working age.

Table 3 below shows the number of new Scottish claims for industrial injuries benefits in the quarter to September 2016, broken down by the gender and age of the claimant.

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| Working age | 270 | 60 |

| Pension age | 180 | 10 |

| Total | 450 | 70 |

The gender imbalance may be linked to the types of occupations in which most claimants work. The Scottish Government:

intends to undertake work to understand why only 16% of people claiming IIDB are women. Some stakeholders observe that this may be due to the nature of the list of prescribed diseases and that it is a historical consequence of men traditionally being more likely to occupy roles in heavy industry and/or manual labour

Scottish Government. (2017). Social Security (Scotland) Bill - Equality Impact Assessment. Retrieved from http://www.gov.scot/Resource/0052/00521332.pdf [accessed 28 June 2017]

Recent DWP statistics show that (at a UK level) over two thirds of new industrial disease assessments (undertaken whether benefit is eventually paid or not) were undertaken for people working in one of the following three standard occupational categories:

process, plant and machine operatives

skilled construction and building trades

skilled metal and electrical trades.3

Table 4 below uses data from the 2011 Scottish census, and shows the number of men and women aged 16-74 working in these occupations.

| All | Women | Men | Women as a percentage of those working in the occupation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 81. Process, plant and machine operatives | 86,701 | 17,422 | 69,279 | 20.1% |

| 53. Skilled construction and building trades | 103,464 | 1,672 | 101,792 | 1.6% |

| 52. Skilled metal, electrical and electronic trades | 111,935 | 2,454 | 109,481 | 2.2% |

It is important to remember that IIDB can be awarded as a result of industrial accidents as well as industrial diseases.

Changes to the industrial injuries benefit caseload

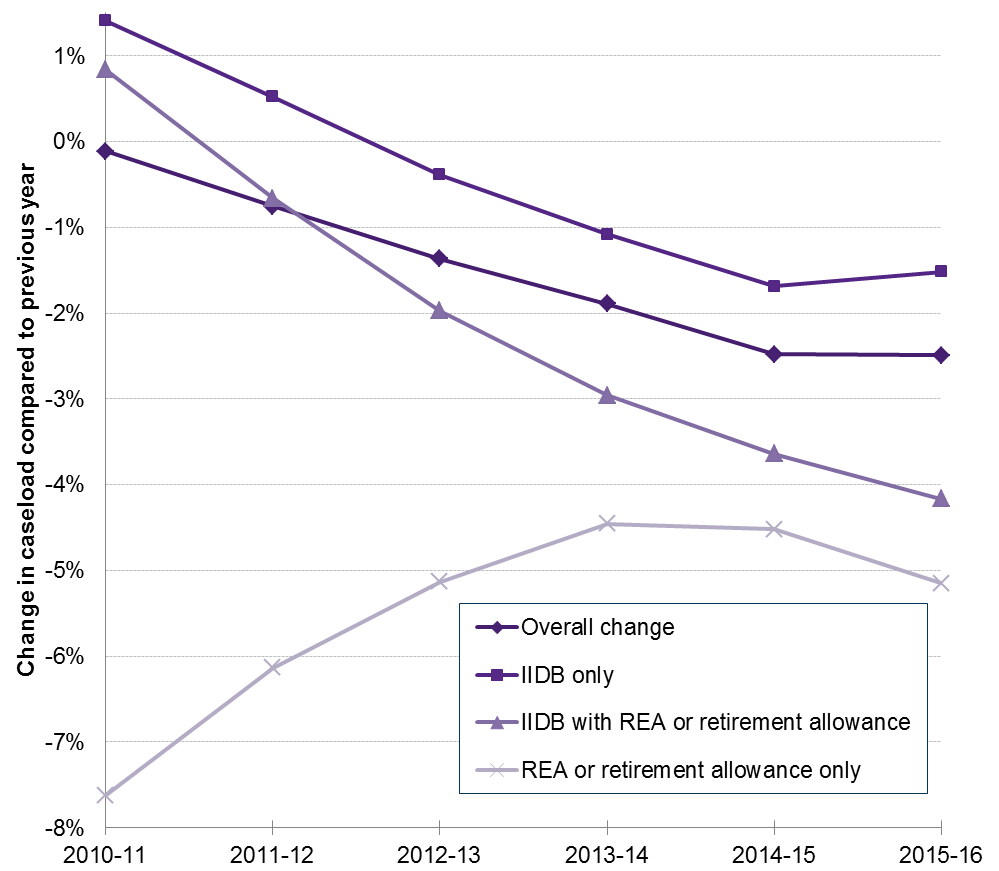

In common with the picture across the rest of Great Britain, the number of industrial injuries benefits claimants in Scotland is decreasing over time. The DWP only publish Scottish caseload statistics for industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB), reduced earnings allowance (REA)/retirement allowance or both of these benefits. Table 5 below shows the change in the Scottish caseload for these combinations of benefits between 2009-10 and 2015-16.

| Total | IIDB only | IIDB with REA or retirement allowance | REA or retirement allowance only | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009-10 | 34,270 | 22,780 | 5,990 | 5,510 |

| 2015-16 | 30,510 | 21,590 | 4,870 | 4,050 |

| Change | -3,760 | -1,190 | -1,120 | -1,460 |

Whilst the decline in numbers is similar for the different combinations, this represents a much more rapid percentage decrease in the number of people with an award of REA or retirement allowance. Figure 2 below shows the year-on-year percentage change in the Scottish caseload for the same benefit combinations above.

Given the restriction to new REA claims (see above), it is likely that this trend will continue.

The financial memorandum to the Social Security (Scotland) Bill 2017 cites a DWP forecast that the Scottish industrial injuries benefits caseload will fall to 29,000 (nearest 1,000) in 2020-21. This forecast assumes no changes to the current eligibility criteria.3

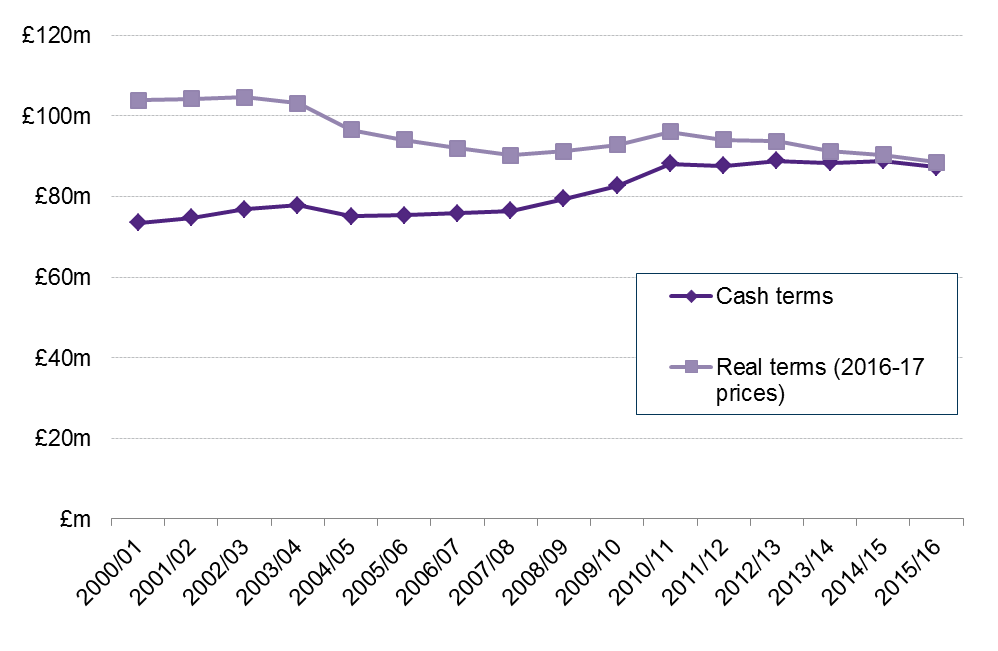

Industrial injuries benefit expenditure

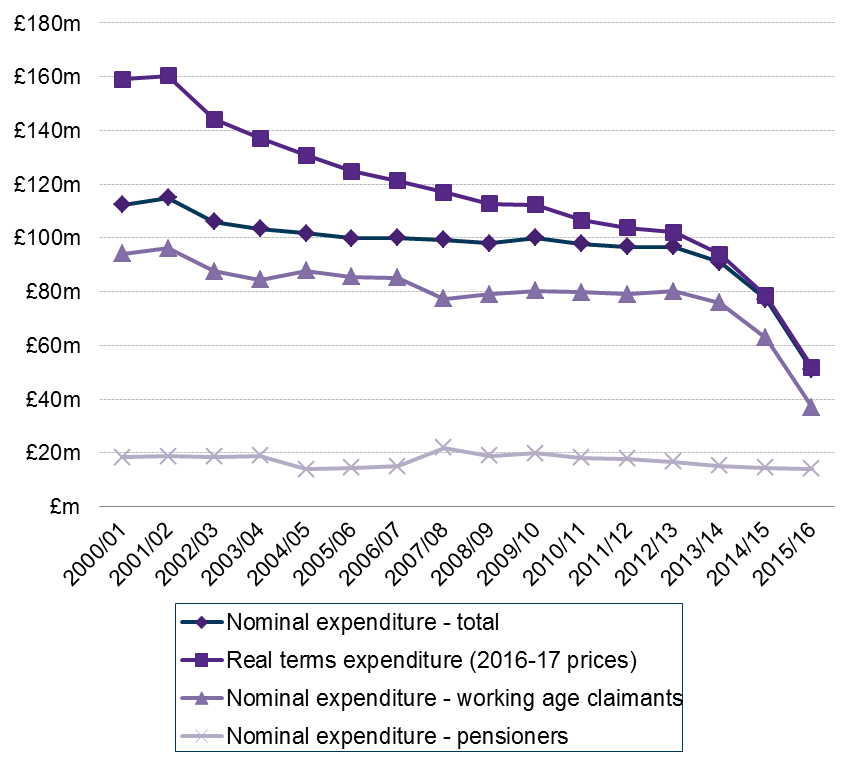

As the industrial injuries benefit caseload has reduced, spending on it has declined in real terms. Figure 2 shows the change in expenditure on industrial injuries benefits in Scotland between 2001-02 and 2015-16, in cash terms and 2016-17 prices.

In the financial memorandum to the Social Security (Scotland) Bill, the Scottish Government estimates that the 2017-18 expenditure on industrial injuries benefits will be £86 million.2 The Scottish Government's working assumption is that when the budget for industrial injuries benefits is transferred it will be around £85 million.2

Severe disablement allowance before devolution

Severe disablement allowance (SDA) was introduced in 1984. It was replaced in 2001 for new claimants. All remaining claimants either first claimed in 2001 or earlier, or were transferred from its predecessor benefit (non-contributory invalidity pension). The majority of SDA claimants will have been transferred to employment and support allowance (ESA) before devolution.

The following sections look at the qualifying conditions for SDA, and who still gets it.

Severe disablement allowance entitlement conditions

This section explains the basic conditions that claimants had to satisfy to qualify for severe disablement allowance (SDA). In addition to residence and presence criteria, claimants had to be unable to work and have a long-term condition to qualify. Claimants who are not entitled to a state pension paid at a higher rate than their SDA can continue getting it after reaching pension age.

SDA was a benefit designed for people who did not have sufficient recent National Insurance (NI) contributions to qualify for a contributory benefit if they were unable to work - those with sufficient NI contributions qualified for other more generous benefits instead. The rates of SDA vary depending on the age at which the claimant first qualified, and are explained below.

There were also residence and presence tests to qualify for SDA for the first time. Continuing entitlement to SDA after moving abroad depends on both the length of absence and whether the claimant moves to another EU country or elsewhere.

Whilst SDA is a working age benefit, those entitled before reaching pension age can continue to qualify after that point. However, people whose state pension is higher than their SDA entitlement are no longer paid SDA (see below).

SDA was targeted at claimants with long-term health problems or disabilities. To qualify a claimant must have been both incapable of work for over 28 weeks, and also either:

have been incapable of work since before their 20th birthday, or

be 80% disabled, based on the percentage scale used to assess entitlement to Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit.

In addition to these groups, those already entitled to a non-contributory invalidity pension when SDA replaced it automatically qualified for SDA.

There is more information about the SDA tests for capacity for work and disablement below.

Severe disablement allowance assessment of capability for work and disability

The entitlement conditions to qualify for severe disablement allowance (SDA) included that the claimant must have been incapable of work for over six months, and either have been incapable of work before turning 20 or have a severe disability. "Severe disability" normally means at least 80% disabled. This section explains these tests further.

Incapable of work

To qualify for SDA, claimants must have been "incapable of work" for at least six months. When SDA was introduced, this was based on a health professional's opinion of whether the claimant was fit to work. People who first claimed from 1995 onwards instead had to pass the test of being "incapable of work" which applied to incapacity benefit.1 This is a points-based test, similar to the "work capability assessment" which is used to decide entitlement to employment and support allowance.

Since 2001 (when SDA was abolished for new claims - see below) to continue to qualify, claimants must continue to meet whichever of these tests applied. However, claimants who are over 65 are treated as meeting the test of being incapable of work, if they were entitled to SDA before reaching that age.

80% disabled

For most claimants, the assessment of disablement is based on the same criteria used for industrial injuries benefits (see above). However, some groups are automatically treated as being 80% disabled. These include:

people entitled to the disability living allowance highest rate care component

people registered blind

people who have already been assessed as 80% disabled for entitlement to an industrial injuries benefit or war pension.2

Severe disablement allowance, work and other benefits

Severe disablement allowance (SDA) is not affected by small amounts of work but ends if a claimant earns more than £120 in a week. SDA is not a means-tested benefit, but is not payable at the same time as some other benefits (most importantly a state pension). SDA counts as income when calculating entitlement to means-tested benefits, but not tax credits.

Entitlement to SDA is not affected if a claimant does a small amount of work, within a complex set of rules. However, it ends if the claimant's work is not permitted by the rules. SDA always ends under these rules if the claimant earns over £120 a week (from April 2017).i There are other restrictions to the types of work and volunteering that SDA claimants are able to do without their benefit being affected. Anyone getting SDA and thinking about starting work is likely to need expert advice on the implications for their benefit entitlement.

SDA is classified as an "earnings replacement" benefit. This means that it cannot be paid at the same time as another earnings replacement benefit (unless the other benefit is worth less than SDA, in which case SDA tops up the total entitlement to the appropriate rate of SDA). Earnings replacement benefits which currently "overlap" with SDA include carer's allowance, maternity allowance, some bereavement benefits, and most importantly, a state pension. This means that anyone who qualifies for a state pension at a higher rate than their SDA entitlement is not paid SDA, for example. In this situation, an "underlying entitlement" to SDA continues despite the fact that it is not payable. SDA can be paid again if the other benefit later stops.

Rates of severe disablement allowance

There is a standard rate of SDA, which is increased for those who became incapable of work before turning 60. Some claimants may still get an addition to their SDA for dependent children (although these were abolished for new claims from 2003, when child tax credit was introduced).

Despite the abolition of new SDA claims, an addition to it can still be claimed for an adult dependant with no or very low earnings. Entitlement to an addition for an adult dependant may also be affected by any benefits that the dependant gets in their own right.

The 2017 weekly rates of SDA are shown in the table below.

| Element | Amount (£/week) |

|---|---|

| Basic amount | 75.40 |

| Age addition - under 40 when first claimed | 11.25 |

| Age addition - 40-59 when first claimed | 6.25 |

| Addition for adult dependant | 37.10 |

| Addition for child dependant | 11.35 |

Some claimants will receive less than these amounts due to the interaction between SDA and other benefits (see above).

Who still gets severe disablement allowance

This section looks at the place of severe disablement allowance (SDA) in the history and structure of reserved benefits for people unable to work. It explains how existing claimants have been transferred to employment and support allowance (ESA). It looks at the current SDA caseload in Scotland, and how many of these people are likely to remain entitled to SDA at the point it is devolved.

The history of severe disablement allowance

Severe disablement allowance (SDA) was introduced in 1984. It replaced the non-contributory invalidity pension, which included a controversial test of being "incapable of household duties" - which was only applied to married women claiming the benefit.

The provision of entitlement for those unable to work before turning 20 was an acknowledgement that people unable to work from a young age would not have had the opportunity to build up a National Insurance contribution record. This route to SDA entitlement was replaced by incapacity benefit in youth in 2001, which was in turn replaced by employment and support allowance (ESA) in youth in 2008. ESA in youth was abolished for new claimants in 2012.

In April 2001, when SDA was replaced for new claims by incapacity benefit, those already entitled continued to get it. Transitional rules initially allowed previous SDA claimants to return to their previous rate of benefit after a gap of up to 84 days (which was extended to 2 years in certain circumstances where the claimant's SDA ended when they started work).

The transfer of severe disablement allowance claimants to employment and support allowance

Since October 2010, the DWP has been transferring existing SDA claimants to ESA. Only those who pass the ESA "work capability assessment" are transferred. The transfer was expected to be complete by April 2014. As such, claimants who reached pension age before 6 April 2014 were not transferred to ESA, and can continue to receive SDA.

However, the transfer is yet to be completed. Any claimants not transferred to ESA at the point that SDA is devolved to Scotland will remain on the benefit unless changes are made by the Scottish Government.1 However, this is likely to mostly consist of claimants over the age of 65, who are exempt from the transfer to ESA.

Current severe disablement allowance caseload and expenditure

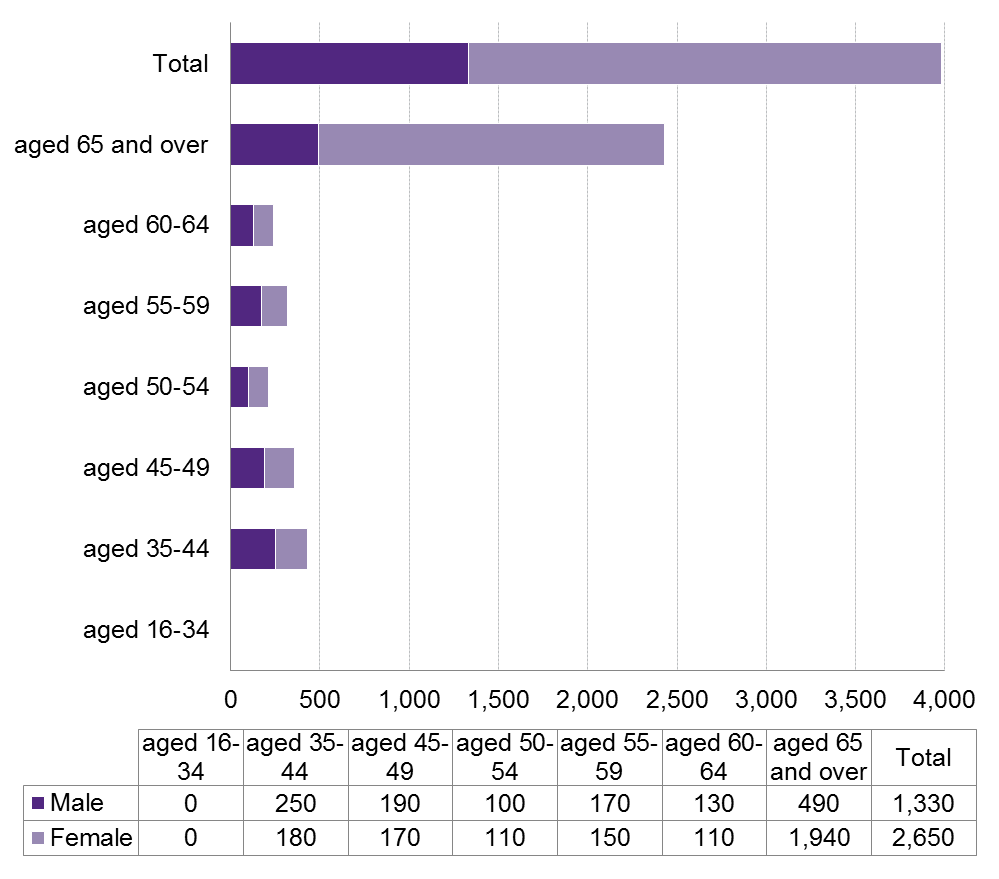

In November 2016, 3,980 people in Scotland received severe disablement allowance (SDA).1 61% of claimants were aged over 65, and so are likely to remain on SDA at the point it is devolved. The policy memorandum to the Social Security (Scotland) Bill 2017 estimates that the caseload when SDA is transferred will be 2,000-2,500.2

Figure 4 below shows the Scottish SDA caseload in November 2016 by age and gender.

The majority of current SDA claimants are women. This disparity is due to the larger numbers of women over the age of 65 receiving SDA. SDA can no longer be claimed, and existing claimants who were under pension age on 6 April 2014 are still being transferred to employment and support allowance. It is likely that when SDA is devolved the proportion of female claimants will be higher than at present, and there will be very few working age claimants (if any) still receiving SDA.

Figure 5 below shows the expenditure on SDA in Scotland, broken down by working age claimants and pensioners, from 2000-01 to 2015-16 (the most recent year available).

The more rapid decline in expenditure since 2013 largely results from the transfer of working-age claimants to employment and support allowance.

Proposals for devolved industrial injuries benefits

Whilst there have been suggestions that there is a need for fundamental changes to the system of industrial injuries benefits, recent changes made by the UK Government have not made major reforms. At the time the Scottish Government published its Consultation on Social Security in Scotland, it stated that:

the UK Government plans to review IIDB as part of their Green Paper on disability and employment.

Scottish Government. (2016, July). A New Future for Social Security: Consultation on Social Security in Scotland. Retrieved from https://consult.scotland.gov.uk/social-security/social-security-in-scotland/ [accessed 18 May 2017]

Perhaps for this reason, the consultation asked if the Scottish Government should work with the UK Government to reform industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB). However, the green paper eventually published by the UK Government in October 2016 made no specific mention of any proposed changes to IIDB.2 It remains unclear whether reforms are intended to the reserved industrial injuries benefits system, and when these might take place.

This section looks briefly at recent UK Government changes, and what the Scottish Government has suggested that it might do to reform IIDB after devolution.

UK Government changes to industrial injuries benefits

The most recent UK Government consideration of fundamental reform to industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB) was a public consultation paper in January 2007. This posed 15 key questions for the future of industrial injuries benefits, arguing that:

The time is right to look at the kind of occupational injury scheme we need for the future.

DWP. (2007). Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit scheme: A consultation paper. Retrieved from http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100824153959/http://dwp.gov.uk/docs/iidb.pdf [accessed 30 May 2017]

In June 2007, the DWP produced a consultation report summarising the points raised by responses, but emphasised that this did not commit it to any particular reform. Whilst most respondents to the DWP consultation supported a continuing industrial injuries benefits scheme, a number of suggestions for improvement were made, including re-introducing reduced earnings allowance, abolishing the 90 day waiting period, and introducing a new allowance linked to rehabilitation. Respondents also suggested ways to link the industrial injuries benefits scheme to incentives to employers to prevent injuries in the workplace.2

Part 2 of the Welfare Reform Act 20123 did make some changes to industrial injuries benefits, but not the fundamental reforms hinted at by the 2007 consultation. Broadly speaking, the changes:

abolished the remaining workmen's compensation schemes that still existed for industrial injuries before 5 July 1948, bringing then within the same statutory framework as industrial injuries benefits

removed different IIDB rules for claimants under 18

allowed trainees on certain types of course to access industrial injuries benefits (as opposed to the previous "analogous industrial injuries scheme")

prevented any further new claims for industrial death benefit from being made (it had already been abolished for deaths happening after 9 April 1988)

abolished the right to request an "accident declaration" (a separate procedure to claiming IIDB, which was duplicated if a claim was later made).

Further details of these changes can be found in a House of Commons Library research briefing on the Welfare Reform Act 2012.4

From time to time, the regulations have been updated, often to modify the list of prescribed industrial diseases. For details of recent changes see above.

The response to the Consultation on Social Security in Scotland from the Public And Commercial Services Union (PCS) suggested that the UK Government may be considering further changes. They stated that:

The UK government is looking at converting IIDB payments for industrial accident into a payment to allow claimants to pursue claims against employers through civil courts.

Public and Commercial Services Union. (2016). Response to Consultation on Social Security in Scotland. Retrieved from https://consult.scotland.gov.uk/social-security/social-security-in-scotland/consultation/view_respondent?_b_index=300&uuId=817356711 [accessed 4 August 2017]

PCS argued that such a move would undermine the "no-fault" nature of the IIDB scheme.

Proposals for the future of industrial injuries benefits

The Scottish Government has yet to commit to any specific reforms to industrial injuries benefits. The consultation on social security in Scotland set out a number of issues that the Scottish Government had identified with the current industrial injuries disablement benefit (IIDB) system, including:

the wide range of diseases and disabilities which are covered by IIDB

the weekly basis of the benefit, disadvantaging some claimants with life-limiting conditions

the fact that links with other disability benefits were not strong (including support to help claimants back to work)

the list of "prescribed diseases" (felt to be restrictive and too focused on male-dominated industries)

the changes in society since industrial injuries benefits were introduced (including advances in workplace health and safety law, and the fact that in 1946 there were no social security benefits for disabled people).1

Possibilities for reform suggested by the specific questions that the Scottish Government posed in the consultation were:

offering some claimants a lump sum as an alternative to a weekly benefit

treating life-limiting conditions differently.

The Scottish Government response to the consultation highlighted suggestions made by respondents for improvement including:

modernisation of the list of prescribed diseases; raising awareness of the scheme; simplifying the complex application process; incorporating the scheme with other disability benefits; and improving alignment with other services.

Scottish Government. (2017). A New Future for Social Security: Scottish Government Response to the Consultation on Social Security in Scotland. Retrieved from http://www.gov.scot/Resource/0051/00514404.pdf [accessed 30 May 2017]

Other suggestions made by respondents to the consultation were that:

IIDB should be disregarded in the calculation of reserved means-tested benefits3

people suffering from a disease that is not listed in relation to their occupation should be able to access IIDB if they can demonstrate that their work in fact caused the disease4

simplifying the process for prescribing new diseases5

introducing an assessment of loss of earnings into IIDB, now that access to reduced earnings allowance is restricted6

including a question on claim forms for other disability benefits about whether a condition was caused by work, and if so treating the claim as also being for industrial injuries benefits.7

S.16 of the Social Security (Scotland) Bill (see above) makes provision to create devolved "employment-injury assistance". This is intended to allow for a devolved replacement for the current industrial injuries benefits. The policy memorandum to the bill describes the Scottish Government's priorities as follows.

The Scottish Government‘s immediate priority is to ensure a safe and secure transition so that those in receipt of [an industrial injuries benefit] at the point of transition continue to receive it at the right time and the right amount. The Scottish Government is not actively considering changes to eligibility, as it currently stands, at the point of transition. The Scottish Government believes there are improvements to be made, such as: providing employment support to those who want it; increasing awareness of occupational health and safety; and the assessments process. The Scottish Government, in partnership with those in receipt of ill-health and disability benefits, and the Industrial Injuries Advisory Group will continue to consider options.

Social Security (Scotland) Bill [as introduced] Policy Memorandum, SP Bill 18-PM. (2017). Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/Social%20Security%20(Scotland)%20Bill/SPBill18PMS052017.pdf [accessed 23 June 2017]

A replacement for the Industrial Injuries Advisory Council?

The current Industrial Injuries Advisory Council (IIAC - see above) will not have a statutory role in Scotland once industrial injuries benefits are devolved.1

The Social Security (Scotland) Bill as introduced does not make provision for any equivalent to IIAC. However, the policy memorandum to the bill highlights that:

The Scottish Government recognises the important role that this Committee has and is currently considering options for how this function could be provided in Scotland.

Social Security (Scotland) Bill [as introduced] Policy Memorandum, SP Bill 18-PM. (2017). Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/Social%20Security%20(Scotland)%20Bill/SPBill18PMS052017.pdf [accessed 23 June 2017]

All UK Non-Departmental Public Bodies (NDPBs) are subject to three-yearly review by their sponsoring department, to check that they are still necessary and effective. The DWP's most recent review of IIAC concluded that:

IIAC provides valuable, high quality, well-respected scientific advice to government about the Industrial Injuries Scheme. The functions IIAC carries out continue to play a vital role in ensuring the Scheme is based on credible, up-to-date scientific evidence. Other delivery options for these functions were considered, but retaining IIAC as a NDPB remained the most appropriate option, offering cost-effective advice of a high calibre, in an independent and transparent way which is generally valued by stakeholders. IIAC meets each of the ‘three tests’ for remaining as a NDPB and we recommend that it should be retained in its current form.

DWP. (2015). Triennial review of the Industrial Injuries Advisory Council. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/411435/iiac-triennial-review-2015.pdf [accessed 28 June 2017]

The delegated powers memorandum to the Social Security (Scotland) Bill invites the views of both the Social Security Committee and the Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee on how the functions of IIAC (and the Social Security Advisory Committee) should be replaced. It suggests that:

“the very different nature of the committee system at Holyrood may make it inappropriate to simply adopt a UK Parliament model.”

Social Security (Scotland) Bill [as introduced] Delegated Powers Memorandum, SP Bill 18-DPM. (2017). Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/Social%20Security%20(Scotland)%20Bill/SPBill18DPM052017.pdf [accessed 28 June 2017]

However, it is clear that a final decision is yet to be made. In answer to a parliamentary question in March 2017, the Minister for Social Security stated that the Scottish Government will:

enlist the support of experts to advise ...on the most effective arrangements, including the Industrial Injuries Advisory Group and the Disability and Carers’ Benefits Expert Advisory Group.

Scottish Parliament. (2017). Written Answers Tuesday 28 March 2017. S5W-08156. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.scot/S5ChamberOffice/WA20170328.pdf [accessed 12 July 2017]

The groups named were both established by the Scottish Government to provide advice on the newly devolved social security powers.6

Employment-injury assistance and personal injury compensation

The Scottish Government response to the consultation left unclear how employment-injury assistance will interact with payments of personal injury compensation. Some responses to the Scottish Government Consultation on a Social Security System for Scotland raised how the UK Government's Compensation Recovery Unit would interact with devolved industrial injuries benefits.1

Schedule 6 of the bill as introduced contains the power to make regulations setting the entitlement conditions for employment-injury assistance. Whilst paragraph 14 of the schedule contains a general regulation-making power, none of the provisions in the bill or accompanying documents make clear the intended relationship between employment-injury assistance and personal injury compensation payments.

Proposals for devolved severe disablement allowance

The Scottish Government has proposed providing the same level of support to remaining severe disablement allowance (SDA) claimants when it is devolved as they currently receive. Most respondents to the Scottish Government consultation agreed with this proposal, although some other suggestions were made.

In its consultation on a social security system for Scotland, the Scottish Government proposed to:

ensure that ... people who are still receiving this benefit when the powers are transferred, continue to receive this level of award through Scotland's social security system.

Scottish Government. (2016, July). A New Future for Social Security: Consultation on Social Security in Scotland. Retrieved from https://consult.scotland.gov.uk/social-security/social-security-in-scotland/ [accessed 18 May 2017]

The reasoning was that by the time powers are transferred there will be very few remaining claimants, and the majority will be over pension age.

Of respondents who answered this question, 83% agreed with this approach. Reasons for agreement included the small number of claimants and diminishing caseload, and the unsettling nature of any reform.2 SDA is not specifically mentioned in the Scottish Government response to the consultation.3

The analysis of responses to the consultation highlights a number of suggestions for alternatives to the Scottish Government's proposed approach to SDA. These include:

providing better support for those not entitled to SDA at the point of transfer

stopping the scheme entirely

merging SDA with other programmes

leaving SDA as the responsibility of the UK Government.2

S.14 of the Social Security (Scotland) Bill (see above) makes provision to create devolved "disability assistance". The policy memorandum to the bill describes SDA as a current type of disability assistance (along with disability living allowance, personal independence payment and attendance allowance).5 However, it goes on to state that the bill does not make explicit provision for SDA, as the Scottish Government's intention is to "use existing powers to run and administer [SDA] once devolved".5 The Scottish Government is yet to decide whether to make regulations replicating the existing SDA rules, or to leave the current regulations in force.7i

Whichever option is chosen, the only suggested future change is to increase the amount of SDA annually (a process known as "uprating"). The Scottish Government's view is that "there is little scope to consider alternative approaches".5

Annexe A: Extract from the Scotland Act 1998

This Annexe reproduces part of Head F in Part 2 of Schedule 5 of the Scotland Act 1998,1 which reserves most social security powers to Westminster. It shows the new exceptions to the reservation of social security which cover severe disablement allowance and industrial injuries benefits (inserted by section 22 of the Scotland Act 2016).2 Note that the use of these powers by Scottish Ministers is currently restricted by provisions in the Scotland Act (Transitional) Regulations 2017.3

Exception 1

Any of the following benefits—

...

(b) severe disablement benefit, so far as payable in respect of a relevant person,

(c) industrial injuries benefits, so far as relating to relevant employment or to participation in training for relevant employment;

but this exception does not except a benefit which is, or which is an element of, an excluded benefit.

...

“Severe disablement benefit” means a benefit which is normally payable in respect of—

(a) a person’s being incapable of work for a period of at least 28 weeks beginning not later than the person’s 20th birthday, or

(b) a person’s being incapable of work and disabled for a period of at least 28 weeks;

and “relevant person”, in relation to severe disablement benefit, means a person who is entitled to severe disablement allowance under section 68 of the Social Security Contributions and Benefits Act 1992 on the date on which section 22 of the Scotland Act 2016 comes into force as respects severe disablement benefit.

“Industrial injuries benefit” means a benefit which is normally payable in respect of—

(a) a person's having suffered personal injury caused by accident arising out of and in the course of his or her employment, or

(b) a person's having developed a disease or personal injury due to the nature of his or her employment;

and for this purpose “employment” includes participation in training for employment.

“Relevant employment”, in relation to industrial injuries benefit, means employment which—

(a) is employed earner's employment for the purposes of section 94 of the Social Security Contributions and Benefits Act 1992 as at 28 May 2015 (the date of introduction into Parliament of the Bill for the Scotland Act 2016), or

(b) would be such employment but for—

(i) the contract purporting to govern the employment being void, or

(ii) the person concerned not being lawfully employed,

as a result of a contravention of, or non-compliance with, provision in or made by virtue of an enactment passed to protect employees.

...

“Excluded benefit” means—

...

(c) a benefit payable by way of lump sum in respect of a person's having, or having had—

(i) pneumoconiosis,

(ii) byssinosis,

(iii) diffuse mesothelioma,

(iv) bilateral diffuse pleural thickening, or

(v) primary carcinoma of the lung where there is accompanying evidence of one or both of asbestosis and bilateral diffuse pleural thickening.

“Employment” includes any trade, business, profession, office or vocation (and “employed” is to be read accordingly).”