Forestry and Land Management (Scotland) Bill

This Bill transfers the powers and duties of the Forestry Commissioners in Scotland to Scottish Ministers. It provides Scottish Ministers with a duty to promote sustainable forest management and publish a forestry strategy. It also provides wider powers than are currently available for the management of forestry land. The regulatory regime for felling trees is updated and becomes the responsibility of Scottish Ministers.The Forestry Act 1967 is repealed for Scotland.

Executive Summary

The Forestry and Land Management (Scotland) Bill was introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 10 May 2017. The Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee has been assigned the lead for scrutiny.

The Bill transfers the powers and duties of the Forestry Commissioners in Scotland to Scottish Ministers. It provides Scottish Ministers with a duty to promote sustainable forest management and publish a forestry strategy.

It transfers responsibility for plant health to Scottish Ministers so that responsibility for all plant health in Scotland will reside in one place.

The Bill widens the provisions currently available for management of forestry land. It includes provisions on the management of land for sustainable development. The bill also sets out provisions for compulsory purchase and the delegation of management functions to community bodies.

The regulatory regime for felling trees is updated and becomes the responsibility of Scottish Ministers.

The Forestry Act 1967 is repealed for Scotland.

Background

This section is taken from a SPICe briefing on Scottish Forestry 1.

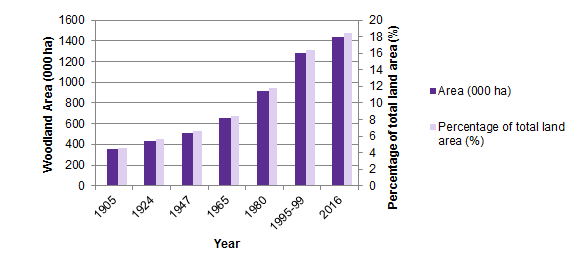

Scotland has a total of 1.44 million hectares of woodland, 33% of which is managed by the Forestry Commission. 74% of this woodland is made up of conifers, the remainder with broadleaves. This compares with 6.2 million hectares of agricultural holdings and common grazing2.

The forestry sector (including associated wood processing, supply chains and forest related tourism) has recently been estimated to support around 26,000 jobs, and £954m of gross value added. The sector is particularly important to the rural economy. Woodland creation and management can contribute to climate change mitigation, biodiversity, flood management, and health and well-being. Forestry can also have negative environmental impacts under some circumstances.

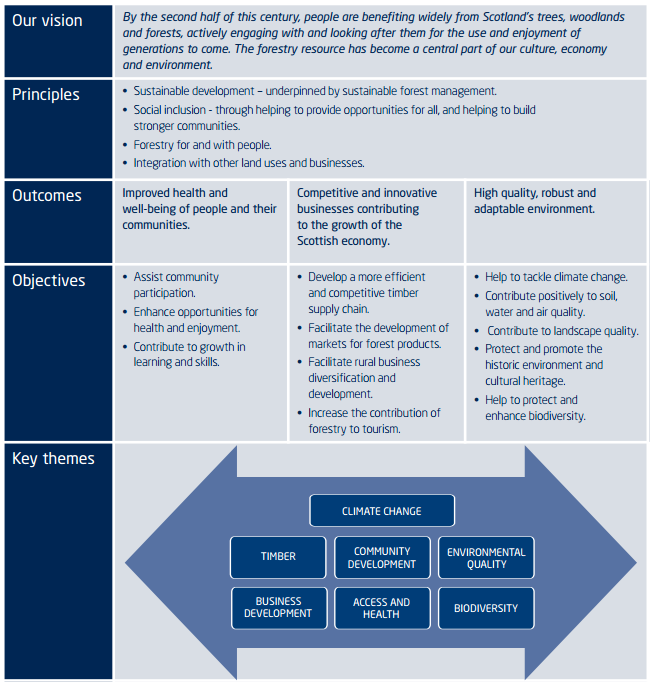

The forestry sector is affected directly and indirectly by a number of domestic policy frameworks, such as the Scottish Forestry Strategy (which is due for review), the Land Use Strategy and the Biodiversity Strategy.

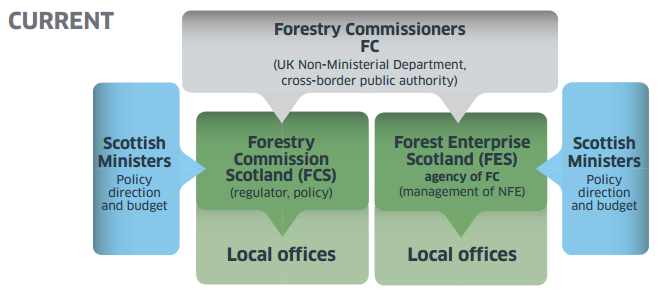

Delivery of Scottish forestry policy is currently the responsibility of Forestry Commission Scotland, part of the Forestry Commission, which is itself a non-ministerial department of the UK government. However, the power to direct the activities of the Forestry Commissioners as they relate to Scotland is devolved to the Scottish Ministers. Forestry Commission Scotland effectively acts as part of the Scottish Government's Environment and Forestry Directorate.

Current Devolution of Scottish Forestry

There is some confusion around the extent to which forestry is currently devolved. Although the subject of forestry is devolved, the functions have remained with the Forestry Commission which is a UK cross border authority. The Land Reform Review Group 1 describes the situation as follows -

The perception might be that FCS [is] part of the Scottish Government, but this is not the case. While responsibility for forestry was devolved in 1999, the responsibilities of the Forestry Commissioners in Scotland were not...

Although Forestry Commission Scotland (FCS) is a part of the Forestry Commission, it effectively operates as part of the Environment and Forestry Directorate, and is funded by the Scottish Government2.

Forest Enterprise Scotland (FES) is an Executive Agency of the Forestry Commission, and also operates as part of Environment and Forestry Directorate. It is tasked with managing the Scottish National Forest Estate in accordance with the priorities and objectives of the Scottish Ministers3. FES was established in 2004 and is classed for accounting purposes as a Public Corporation, i.e. a government-controlled body which covers at least half of its production costs through sales of goods and services. FES is accountable to the National Committee for Scotland, a subsidiary body of the FC to whom FC has delegated its powers and duties in relation to the National Forest Estate4.

FES employed 822 FTE members of staff during the year 2015-165. FES’s income from timber sales in 2015/16 was £62.4m6.

Forest Research is an Executive Agency of the Forestry Commission and was set up in 19977. It operates across Scotland, England and Wales and is responsible for carrying out research on behalf of the Forestry Commission. Forest Research's priorities are shaped by the Scottish Forestry Strategy, the Welsh Government's Woodland Strategy and the UK Government's Forestry and Woodlands Policy Statement8. It is advised by the Forestry Commission on its strategic direction and performance management. Forest Research is funded partly by the DEFRA, as well as by Forestry Commission England, Forestry Commission Scotland and Natural Resources Wales, receiving a total of £9.6m from these sources in 2015-16. Increasingly, it also attracts funding from other government departments, the European Commission, UK research councils, commercial organisations, private individuals and charities, and received £5.0m of funding from such sources in 2015-169.

Forest Research has two main research stations, one in Hampshire, England, and the other in Roslin, Midlothian. Forest Research employed 178 FTE members of staff during the year 2015- 16. As of 2015-16, its research activities covered:

tree health

pests and diseases

ecosystem services

the use of woodland to reduce flooding, and

GHG emissions associated with forestry.

Full Devolution of Scottish Forestry

The Forestry and Land Management (Scotland) Bill is part of a larger programme of work to complete devolution of forestry. The Bill deals with the main legislative changes required in Scotland. However, in order to complete the work, once the Bill is passed, further legislative and administrative measures will be required, including:

the passage of orders under sections 90 and 104 of the Scotland Act 1998 to-

wind up the Forestry Commissioners as a cross-border public authority

transfer relevant property and liabilities to the Scottish Ministers and in relation to the transfer of staff

underpin the new cross-border arrangements.

establishing new cross-border arrangements with the UK and Welsh Governments, the Forestry Commissioners and Natural Resources Wales.

creation of new organisational structures for forestry and land management in Scotland.

Development of the Bill

In June 2015, then Minister for Environment, Land Reform and Climate Change, Dr Aileen McLeod announced that discussions were underway between the Scottish and UK governments to discuss the transfer of the Forestry Commissioners’ powers and duties as they relate to Scotland.

In 2016 the Scottish National Party manifesto1 included a commitment to complete the devolution of forestry. The Forestry Bill provides the legislation to deliver these commitments. It also includes a number of additional elements.

The Future of Forestry in Scotland - A Consultation 2was published in August 2016. It consulted on proposals to -

introduce new organisational arrangements so that the management of forestry in Scotland is fully accountable to the Scottish Ministers and to the Scottish Parliament

ensure that effective cross-border arrangements are in place to suit Scottish needs

replace the Forestry Act 1967 with a modern approach to the development, support and regulation of forestry.

Consultation responses are available on the Scottish Government website.

An analysis of the consultation responses3 was published in February 2017.

Objectives and Content of the Bill

The Forestry and Land Management Bill was introduced by the Cabinet Secretary for the Rural Economy and Connectivity, Fergus Ewing MSP, on 10 May 2017. The Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee is lead committee on this Bill.

According to a Scottish Government summary, the Bill has three aims -

Improved accountability, transparency and policy alignment

Forestry fully accountable to Scottish Ministers and Scottish Parliament

Simpler and more transparent governance arrangements

Parity between state and non-state sector in terms of regulation

Alignment of forestry policy with other relevant areas, aiding delivery of wider economic, social and environmental outcomes

All plant health responsibilities to sit with Scottish Ministers

Modernisation

New legislative framework to support, regulate and develop forestry

Forestry Act 1967 repealed

Duty to promote sustainable forest management

Flexible, enabling and reflects 21st century delivery landscape; simplification of offences regime and more transparent appeals process

Regulatory system supported by secondary legislation

More effective use of Scotland’s publicly-owned land

Management of National Forest Estate by Scottish Ministers, for multiple purposes (not just forestry)

Commitment to sustainable forest management where land is used for forestry

Ability to delegate land management functions to community bodies

Ability for Scottish Ministers to enter into arrangements to manage other people's land (including public bodies), fulfilling commitment to establish a Land Agency for Scotland.

Part 1 of the Bill provides an overview of its contents -

Part 2 is about Scottish Ministers’ forestry functions

Part 3 is about management of land by Scottish Ministers

Part 4 is about felling

Part 5 is about Scottish Ministers’ general powers under the Act

Part 6 contains general and final provisions.

Part 2 - Forestry Functions

The Forestry Act 1967 requires the Forestry Commissioners to promote the interests of forestry, the development of afforestation and the production and supply of timber and other forest products. The Bill seeks to repeal the Forestry Act 1967 in Scotland.

Part 2 of the Bill seeks to transfer and update the powers and duties of the Forestry Commissioners, in so far as they relate to Scotland, to Scottish Ministers, as set out below.

Duty to Promote Sustainable Forest Management

Currently, all publicly funded forestry in the UK is required to meet the UK Forestry Standard. This includes woodland for which grants have been provided. This is a reference standard for sustainable forestry, and “provides a framework for the delivery of international agreements on sustainable forest management”1.

Section 2 states that Scottish Ministers must promote sustainable forest management.

The Bill does not define sustainable forest management. However, the Policy Memorandum uses the widely accepted definition from the 1993 pan-European Ministerial Conference on the Protection of Forests in Europe. Sustainable forest management is -

the stewardship and use of forest lands in a way and at a rate that maintains their biodiversity, productivity, regeneration capacity, vitality and their potential to fulfil now and in the future relevant ecological, economic and social functions at local, national and global levels and that does not cause damage to other ecosystems.

The analysis of responses to the consultation shows that the majority of respondents (54%) said that Scottish Ministers should be placed under a duty to promote forestry. 8% said they should not. 37% did not answer that question.

Forestry Strategy

There is currently no statutory duty for Scottish Ministers to publish a forestry strategy. Although there is one, published in 20061. A summary is set out below.

Section 3 of the Bill states that Scottish Ministers must prepare a forestry strategy which sets out objectives, priorities and policies. Sections 4 and 5 are about the preparation (including the need to consult) and publication of the strategy. Section 6 says that Scottish Ministers must have regard to the forestry strategy in certain circumstances.

The Policy Memorandum states that - The Scottish Ministers may, on enactment of the Bill, adopt a previously published strategy provided that it has been prepared in accordance with the requirements set out in the Bill.

There is no mention of a duty on Scottish Ministers to prepare and publish a forestry strategy in the consultation.

Tree Health and Silvicultural Material Testing Functions

The primary legislation governing plant health in Great Britain is the Plant Health Act 1967. The Act currently empowers the Forestry Commissioners to:

make orders to prevent the introduction and spread of forestry pests and diseases

require local authorities to undertake certain work to prevent the spread of specified pests or diseases.

The Plant Variety and Seeds Act 1964 was passed to allow regulation on the sale of plants and seeds. It provides "for the granting of proprietary rights to persons who breed or discover plant varieties […] to confer power to regulate, and to amend in other respects the law relating to, transactions in seeds and seed potatoes, including provision for the testing of seeds and seed potatoes […]”. This will become the responsibility of Scottish Ministers.

Sections 7 and 8 of the Bill have the effect of transferring responsibility for the testing of silvicultural propagating and planting material and tree health in Scotland, from Forestry Commissioners to Scottish Ministers.

Section 29 (subsection 2 and 4) of The Plant Variety and Seeds Act 1964 are repealed.

Section 29 (2 and 4) allows the Forestry Commission to establish and maintain an official seed testing station for silvicultural propagating and planting material. Its repeal means that Forestry Commissioners will no longer be able to do this in Scotland.

Neither the Plant Health Act 1967 nor the The Plant Variety and Seeds Act 1964 were specifically mentioned in the consultation. However, views on tree health were sought and found to be an area of particular concern to stakeholders.

The Policy Memorandum states that these sections mean that responsibility for all plant health in Scotland will now reside in one place.

Part 3 - Management of Land by Scottish Ministers

Part 3 makes provision for the Scottish Ministers to manage land for the purpose of promoting sustainable forest management or furthering the achievement of sustainable development in relation to non-forestry land. It provides a framework of powers for managing land for those purposes.

Land Reform and Community Empowerment

The focus of Part 3 of the Bill is about the management of land. Many of the issues included such as sustainable development, community body, purchase of land where there is an unwilling seller, have been debated in the Scottish Parliament recently as part of the scrutiny of both the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 and the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015. The policy memorandum states that -

The Bill enables the Scottish Ministers to delegate their land management functions to community bodies. The Forestry Act 1967 enables delegation of forestry functions to community bodies but the Bill widens the scope of the delegation to include all land management functions, contributing to the community empowerment policy agenda.

Some of these issues from the land reform and community empowerment debates are therefore highlighted here.

Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016

Part 5 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 gives a community body the right to buy land to further sustainable development, without a willing seller. There was much discussion about this in the scrutiny of the Bill. The Act provides extensive provision relating to -

the meaning of land

the meaning of excluded land. i.e what land cannot be bought under Part 5

the meaning of eligible land

what a part 5 community body is

the application procedure

information about Ministers decision

details on the transfer of the land

compensation, and

appeals.

A community body wishing to buy land must set out

"the reasons the Part 5 community body considers that its proposals for the land satisfy the sustainable development conditions set out in section 56(2) (or, where the application is to buy a tenant's interest, those conditions as modified by section 56(6)(a))" and

"the proposed use, development and management of the land (including, as the case may be, the land to which any tenant's interest relates)."

Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015

Part 4 of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 inserts a new Part 3A into the Land Reform (Scotland) 2003 Act. It introduces a new provision for community bodies to purchase land which is abandoned, neglected or causing harm to the environmental well being of the community, where the owner is not willing to sell that land. This is if the purchase is in the public interest and compatible with the achievement of sustainable development. This was also subject to much discussion as the Bill passed through Parliament.

It is unclear from the Bill and associated documents, whether this Bill links with provisions in these Acts, and whether the Bill is intended to be part of the Scottish Government's land reform agenda.

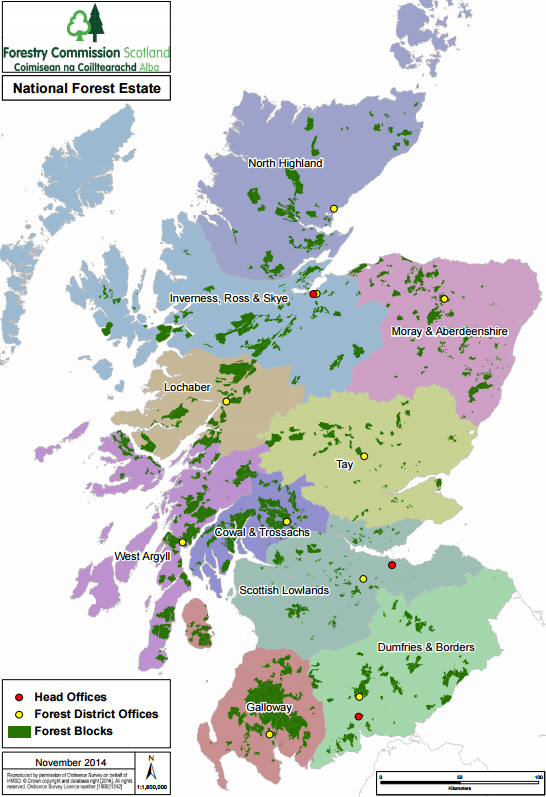

The National Forest Estate

Scotland's National Forest Estate is managed by Forest Enterprise Scotland (FES), the management agency of Forestry Commission Scotland (FCS), on behalf of Scottish Ministers. It covers approximately 630,000 hectares, is distributed widely across Scotland and supports a range of activities in addition to forestry, including renewable energy, agriculture and tourism. The woodland area within the National Forest Estate is 477,0001 ha, 31.5% of the 1,419,000 ha of woodland in Scotland1.

The extent of the National Forest Estate fluctuates as a result of disposals and acquisitions of land undertaken as part of Forest Enterprise Scotland's new woodland investment programme. This programme seeks to enable Forest Enterprise Scotland to ensure that the land forming the National Forest Estate is suited to achieving the objectives of the Scottish Forestry Strategy. Between 1999 and 2016, the repositioning programme yielded a net profit of £59.3m.

The National Forest Estate is divided into forest districts. Each district decides how the national strategic plan will be implemented at the local level.

Around one third of the National Forest Estate is not forested. The 1967 Forestry Act currently requires management of the National Forest Estate to be tree-related. The provisions in the Bill set out below, seek greater flexibility to manage both forested and non-forested land within the National Forest Estate.

Management of Forestry Land

Currently, under the Forestry Act 1967, Forestry Commissioners are required to promote the interests of forestry, the development of afforestation and the production and supply of timber and other forest products.

Section 9 of the Bill states that Scottish Ministers must manage forestry land in a way that promotes sustainable forest management and may also be managed for the purpose of furthering sustainable development. Section 13 states that Scottish Ministers must manage other land to further sustainable development.

The Bill includes a new power (section 9(3)) to enable management of forestry land for the purpose of furthering sustainable development, if Scottish Ministers have regard to the forestry strategy. This gives greater flexibility in the use of the National Forest Estate compared to what was permitted under the Forestry Act 1967, which required all activity to be tree-related. The Policy Memorandum states that -

...around one third of the NFE is not afforested and recent developments on that open land – such as starter farms – have required tree-related activity to meet the Forestry Act 1967 requirements.

The meaning of forestry land under this section is:

the national forest estate

land in Scotland that is at the disposal of the Forestry Commissioners under the Forestry Act 1967 immediately before the date on which this section comes into force, and

land that the Scottish Ministers acquire under section 15(1)(a) [power to acquire land] or 16(1)(a) [power to purchase land compulsorily].

"Other land that the Scottish Ministers manage for the purpose of exercising their functions under section 9". The explanatory notes state that this is "intended to capture land owned by the Scottish Ministers that is not part of the national forest estate that they determine would be suitable for forestry; or land managed by them which would be suitable for forestry, for example, land which is managed by the Scottish Ministers for the purpose of section 9, in accordance with arrangements under section 14(1)"

Management of Land to Further Sustainable Development

Section 13 states Scottish Ministers must manage land mentioned in subsection (2) for the purpose of furthering the achievement of sustainable development.

No definition of sustainable development is provided in the Bill or the accompanying documents. This is consistent with the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 and the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015. Discussion on definitions of sustainable development in relation to land reform can be found on page 23 of the SPICe briefing: International Perspectives on Land Reform1.

The land referred to in subsection (2) is:

land that the Scottish Ministers acquire under section 15(1)(b) [power to acquire land] or 16(1)(b) [power to purchase land compulsorily].

where the Scottish Ministers have entered into an arrangement under section 14(1) to manage land for the purpose of this section, that land.

This seems to apply to newly acquired or purchased land, and land where Scottish Ministers enter into arrangements to manage land, but not to existing land owned by Ministers or that land is currently part of the National Forest Estate. It is unclear what this section adds to the powers that are set out in sections 9, 10 and 11.

The Policy Memorandum states -

This means that Scottish Ministers have an integrated set of land management powers to manage different types of land.

Acquisition, Compulsory Purchase and Disposal of Land

Sections 15, 16 and 17 in the Bill deal with acquisition, compulsory purchase and disposal of land.

The Forestry Act 1967 also contained provisions on acquisition and disposal of land, and compulsory purchase.

The Acquisition of Land (Authorisation Procedure) (Scotland) Act 1947 governs compulsory purchase orders in Scotland. Paragraph 1 of schedule 1 of this Bill seeks to add the compulsory powers in the Bill into section 1 of the 1947 Act. This is intended to ensure that the provisions here will be subject to the provisions of the 1947 Act.

The Scottish Government has, separate to this Bill, published guidance which sets out its policy on the use of compulsory purchase orders in Scotland1. The guidance states that a compulsory purchase order can allow organisations (including Scottish Ministers) to acquire land without the owner's permission, where there is a strong enough case for this in the public interest. It also sets out the issues to be considered and compensation required where compulsory purchase is being considered. Sustainable development is not mentioned in this guidance.

The Bill therefore appears to seek to widen the principles under which Scottish Ministers may use compulsory purchase powers to include sustainable development. These powers may be used to acquire land required to exercise functions under -

section 9 (to manage forestry land to promote sustainable forest management) and

section 13 (to manage newly acquired or purchased land to further sustainable development).

Delegation of Functions to Community Bodies

Section 18 allows the delegation of the management of forestry or other land to community bodies. Section 19 sets out the meaning of a community body. Section 20 sets out what community bodies must have regard to in carrying out a delegated function.

This provision is similar to one in the Forestry Act 1967, but widens the scope. It enables Scottish Ministers to delegate forestry and land management functions to community bodies. Therefore, according to the policy memorandum, it contributes to the community empowerment agenda. However, as discussed above, the policy memorandum does not say anything further about how the Bill and the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 relate to each other.

Section 19 of the Bill sets out the meaning of Community Body. The definition of community body in the section 37 of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 is not the same as the definition of community body in the Bill. In addition, section 19(3) allows Scottish Ministers to "disapply any or all of the requirements specified in paragraphs (b) to (f) of subsection (2) in relation to any particular body."

This seems to mean that the conditions that a body needs to satisfy in order to qualify under this section are that the body has a written constitution including:

a definition of the community to which the body relates

provision ensuring proper arrangements for the financial management of the body

provision that any surplus funds or assets of the body are to be applied for the benefit of the community,

and that Scottish Ministers are satisfied that the main purpose of the body is consistent with furthering the achievement of sustainable development.

As mentioned above, there is no definition of sustainable development in the Bill or the accompanying documents.

Despite this, it should be noted that section 98 of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 amended the meaning of community body in section 7C of the Forestry Act 1967. The meaning of community body in the Bill is the same as in the Forestry Act 1967. The difference between the meaning in the 2015 Act and the Bill may be relevant now because the Bill relates not solely to management of forestry land and includes provisions on sustainable development, which the 1967 Act did not.

Part 4 - Felling

The Forestry Act 1967 provided Forestry Commissioners with powers related to the felling of trees. Since this Bill seeks to repeal the 1967 Act in Scotland, part 4 provides Scottish Ministers with similar powers.

The Policy Memorandum1 states that -

While the Forestry Act 1967 focused on timber production, the new regime allows for a broader view to be taken.

In the Forestry Act 1967 full details of the regime on felling is included in the primary legislation. In this Bill specific details will be set out in secondary legislation. The Policy Memorandum states that there are a number of advantages to this approach:

Enabling powers allow for a more modern, flexible regime

The form that applications and permissions can take is not prescribed, allowing for processes that are proportionate to the activities that they seek to regulate

It allows for greater opportunities to engage with the sector and the public and to adapt them [regulations] over time if policies or practices change.

The secondary legislation will be laid before the Scottish Parliament in the course of 2018, with final commencement of the new framework planned for 20191.

The analysis of consultation responses 3 states that a small number of respondents commented on felling. These were generally supportive.

Offence of Unauthorised Felling

Section 23 of the Bill creates an offence of unauthorised felling. Section 24 provides exemptions that will be set out in (affirmative) regulations.

Section 23 maintains the general principle from the Forestry Act 1967, that a felling licence or permission is required for felling growing trees except in certain circumstances.

Felling is not an offence if it is carried out under:

exemptions (section 24)

a felling permission (sections 25 - 30)

a felling direction (sections 31 and 32)

a restocking direction (section 33 and 34)

a registered notice to comply (section 35 - 41) or

a remedial notice (section 48 and 49).

The Bill does not specify exemptions to the need for permission to fell a tree. But section 24 states that (affirmative) regulations on exemptions will be made by Scottish Ministers when the Bill is passed.

Over the last 5 years, Forestry Commission Scotland has investigated between 20-70 cases of suspected illegal felling per year. This has resulted in on average one conviction per year1.

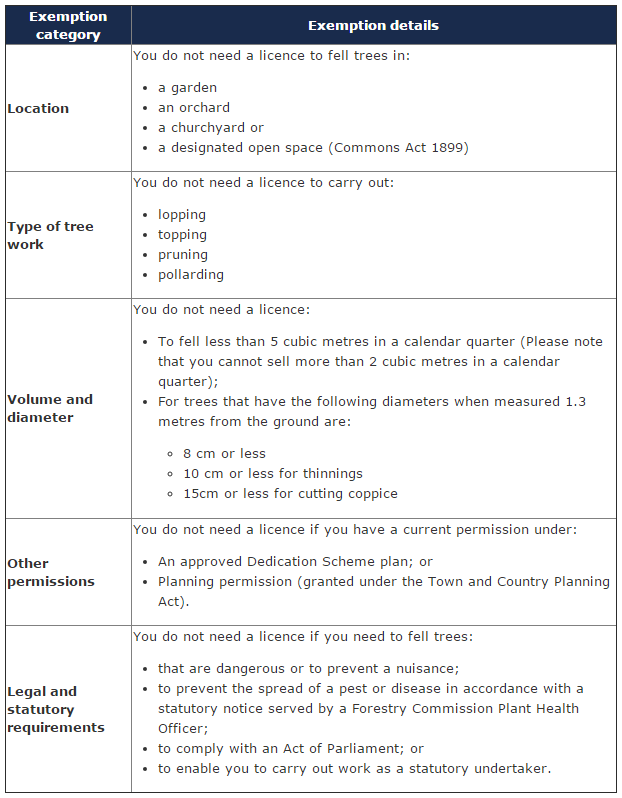

Felling Permission Exemptions

Section 9 (1) of the Forestry Act 1967 states that a felling licence is required to fell growing trees except in certain circumstances. The Forestry Commission Scotland website sets out when a licence to fell a tree is currently NOT required.

Section 24 of the Forestry and Land Management (Scotland) Bill provides that a Scottish Ministers may make regulations (via the affirmative procedure) to set out when permission to fell a tree is not required.

Felling Permission and Continuing Conditions

Section 25 allows land owners or occupiers (with owners permission) to apply to Scottish Ministers to fell a tree. Section 27 is about decisions related to permission to fell, and what conditions (such as restocking) may be required. Section 30 sets out how felling permission and Tree Preservation Orders work together.

Much of the detail on both of these sections will be set out in regulation subject to the negative procedure in parliament. Section 27(4) states that felling may be subject to conditions such as:

how felling is to be carried out (this may mean clear felling or selective felling)

when felling is to be carried out

steps that must be taken after felling (known as a continuing condition).

Scottish Ministers may require land to be restocked with trees after felling, by specifying a "continuing condition" in response to the application for permission to fell the trees. This is distinct from restocking directions (section 33) which relates to restocking after illegal felling.

Felling Directions

Section 31 allows Scottish Ministers to require trees to be felled.

Trees may need to be felled:

to prevent deterioration of timber quality

to improve growth of other trees

to prevent or reduce harm caused by the presence of trees.

Regulations (negative) can be made to set out further detail. Section 32 states that it is an offence not to comply with a felling direction.

Restocking Directions

Section 33 allows Scottish Ministers to require land to be restocked with trees.

This might be used if trees have been felled and:

the felling is not exempt under section 24

there is no felling permission, felling direction, restocking direction, a registered notice to comply or a remedial notice

a continuing condition has not been complied with.

Regulations (negative) can be made to set out further detail. Section 34 states that it is an offence not to comply with a restocking direction.

Registering Notices to Comply

Section 35 states that Scottish Ministers may register a notice to comply with continuing conditions on felling permissions, felling directions and restocking directions.

Notices may be registered with the Land Register for Scotland or the General Register of Sasines. The explanatory notes explain that the effect of registering notices is that the obligations imposed by the notice are easily assessed by any prospective new owner and are automatically passed to any future owners of the land to which they relate.

If a notice has been registered, and then complied with, section 38 requires Scottish Ministers to register a notice of discharge from compliance.

Compliance

Sections 42-47 provide Scottish Ministers with powers to ensure that directions related to felling or restocking are complied with. This includes powers to ask for information, to visit a site, and to enter land.

Where a direction related to felling is not being complied with, sections 48- 58 provide powers to ensure that the action required is undertaken. This is via remedial notices, step-in powers and powers to recover expenses.

A remedial notice (under s48(2)) is a notice requiring the person to undertake an activity or stop an activity within a specified time period.

A step-in power allows Scottish Ministers to enter land and undertake an activity or stop an activity set out in a remedial notice. Any reasonable expenses incurred by Scottish Ministers when using the step-in power may be recovered.

Appeals

Section 60 provides the right to appeal against decisions made by Scottish Ministers related to felling.

Regulations (negative) may be made to set out further details of the appeals process.

Financial Memorandum

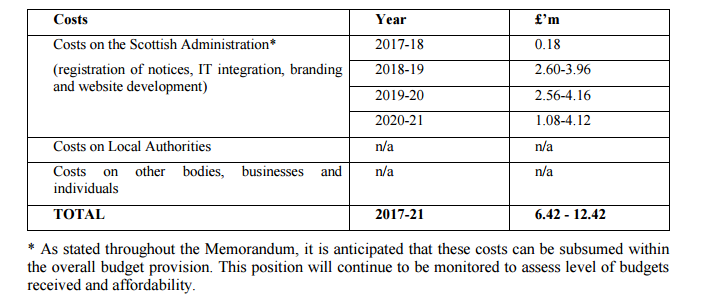

The Financial Memorandum sets out the costs associated with measures in the Bill1. It states that -

The Scottish Government has identified no financial implications for local authorities or other bodies, individuals or businesses as a direct result of the Bill's provisions and only minimal additional cost on the Scottish Administration.

However, the Financial Memorandum also considers the costs associated with future cross-border collaboration with England and Wales and of new organisational structures. These may be more substantial.

The budget for cross border collaboration of around £11 million is currently funded through the DEFRA. FCS and FES provide additional funding, mainly to Forest Research. This funding covers work specific to forestry in Scotland. In 2016-17 Forest Research received £2.48 million from FCS and FES for activities such as research projects, diagnostic services, inventory and forecasting support.

A Forestry Governance Project Board was set up in 2015 to consider financial arrangements amongst other things, following full forestry devolution. The Financial Memorandum states that the working assumption is that the division of existing funding will not lead to increased costs for Scotland.

The main costs associated with establishing new organisational arrangements are -

Moving and integrating FCS and FES IT to the Scottish Government's network, estimated to be between £2.05 - £8.05 million, between 2017/18 - 2020/21.

Branding and website management for the new organisations, estimated to be £4.25 million, between 2017/18 - 2019/20.

The table below summarises the costs arising from the Bill. Most of the costs shown do not relate directly to the Bill, but to establishing new organisational arrangements if the bill is passed.

Future work to complete Forestry Devolution

The consultation document focussed on new organisational arrangements for forestry in Scotland and effective cross-border arrangements. Neither of these issues are addressed in the Bill itself.

The explanatory notes state that -

The Bill is part of a larger programme of work to complete devolution of forestry that includes establishing new cross-border arrangements with the UK and Welsh Governments as well as the Forestry Commissioners and Natural Resources Wales for the exercise of forestry functions currently delivered on a GB basis; and the creation – by administrative means – of new organisational structures for forestry and land management in Scotland.

It goes on to say that the Bill is the principal vehicle to make the legislative changes associated with the devolution programme; however, once the Bill has completed its passage orders will be required under sections 90 and 104 of the Scotland Act 1998 to:

wind up the Forestry Commissioners as a cross-border public authority

transfer relevant property and liabilities to the Scottish Ministers and in relation to the transfer of staff; and

underpin the new cross-border arrangements.

Powers for the Scottish Ministers to promote, develop, construct and operate renewable energy installations on land that they manage, and to delegate that function to community bodies, will also be sought via an order under section 104 of the Scotland Act 1998 due to the reservation in section D1 of Schedule 5 to that Act.

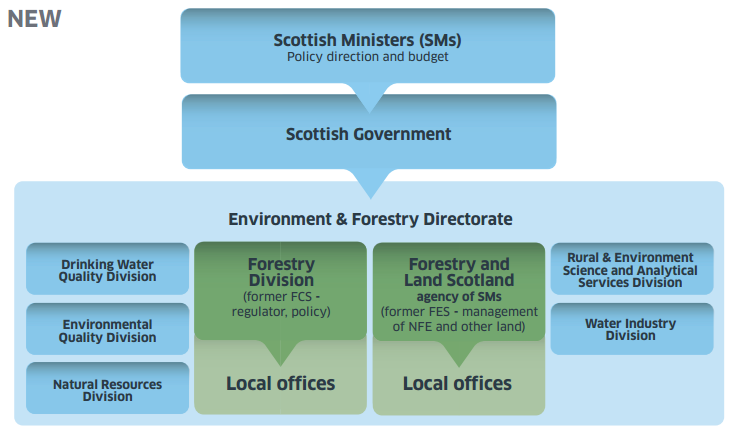

New organisational arrangements for forestry in Scotland

If the Bill is passed, new organisational structures will be put in place.

Forestry Commission Scotland currently promotes forestry, advises on and implements forestry policy, administers grants and regulates the forestry sector.

The Forestry Commission will be replaced by a new dedicated Forestry Division within the Environment and Forestry Directorate in the Scottish Government.

Forest Enterprise Scotland is currently an Executive Agency of the Forestry Commission. It is a land management body with responsibility for managing the National Forest Estate.

Forest Enterprise Scotland will be replaced by a new Executive Agency of Scottish Ministers called Forestry and Land Scotland.

The new structure is shown below.

In terms of staffing these organisations, the consultation documents states -

About one thousand civil servants work for FCS and FES. FCS staff are located in the Edinburgh national office and in five conservancies around the country, which provide guidance and implement policy and regulations locally and also carry out health, education and engagement programmes with local communities. The FES head office is based in Inverness with staff managing the NFE locally in ten forest districts across Scotland. In addition, 200 Forestry Commission staff, who provide some of the current shared services and cross-border functions (including research) as part of UK Government functions, are also located in Scotland.

Many of those responding to the consultation who disagreed with the proposed new arrangements, said that Scotland‘s forests should:

be or remain independent and be the responsibility of a stand-alone organisation which is separate from government

be managed by forestry experts/professionals, rather than by civil servants

sit within a single organisation and not be divided between two different bodies.

Cross Border Arrangements

The Bill transfers the functions of the Forestry Commissioners as they relate to Scotland, to Scottish Ministers. However, some of the Forestry Commissioners' functions operate on a cross-border basis, mainly funded through DEFRA on behalf of England, Scotland and Wales but also with some additional funding from FCS and FES for Scottish-specific activities1.

The policy memorandum states -

The Scottish Government is committed to ensuring that there are ongoing effective cross border arrangements where it makes sense and where these meet Scottish needs.

Despite priorities for cross border arrangements being a focus of the Scottish Government consultation document, they are not part of the Bill. The consultation document lists the current cross border functions to include:

Forestry science and research (one of the two forest research stations is in Scotland)

Tree health

UK Forestry Standard

Woodland Carbon Code

Inventory/Forecasting and operational support

Economic

Statistics

International forestry policy

The consultation document said that the priorities for continuing collaboration and cooperation are forestry science and research, tree health and common codes (such as the UK forestry standard and the woodland carbon code). The vast majority of respondents who replied to this question agreed with these priorities.

The Policy Memorandum states that -

One of the agreed outcomes being sought by the cross-government Forestry Governance Project Board [FGPB] is a legacy of refreshed and strengthened cross-border cooperation and partnership working between England, Scotland and Wales on relevant forestry matters. The FGPB is due to make recommendations to the three Administrations about the equitable division of the existing DEFRA budget for all cross-border functions and about how continuing collaboration and partnership working between the three countries will operate and be reviewed in the future to guarantee an appropriate level of service to all three countries.

An order under section 104 of the Scotland Act 1998 in the UK Parliament will be required to help set up these arrangements following the passage of the Bill. While final decisions have still to be made, it is anticipated that Scotland will take the lead on delivering some of the functions on behalf of England, Scotland and Wales.