Energy Policy

This briefing provides an introduction to key energy policies and targets within a world, European, UK, and Scottish context.

Executive Summary

A global approach to reducing greenhouse gas emissions was agreed in Paris in 2015. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change undertook to limit global mean surface temperature rise to less than 2oC, and installing renewable energy technologies and reducing energy usage are seen as playing a key role in achieving this. Alongside addressing climate change, security of supply and affordability are key considerations - this is known as the energy trilemma.

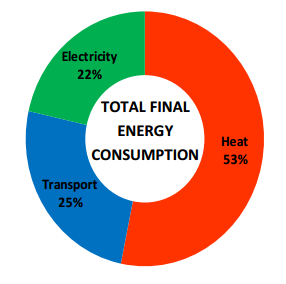

Electricity represents only 22% of Scotland's total energy consumption, with higher requirements for both heat (53%) and transport (25%). European, UK and Scottish policy is aligned with global agreements - to date, policies have mostly targeted the decarbonisation of electricity, however focus is now shifting to the heat sector and to a lesser extent, transport. UK energy policy is complex, and Scottish policy overlaps significantly with this in the context of a developing international framework.

The EU has energy targets for 2020, 2030 and 2050, and Member States have agreed the current Energy Strategy which, by 2020, seeks to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 20% from 1990 levels; raise the share of energy consumption produced from renewables to 20%; and improve energy efficiency by 20%. More stringent targets are also in place for 2030, including a 40% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, and at least a 27% share of energy consumption from renewables. A number of directives enforce these targets, as well as an Emissions Trading Scheme. The impact of Brexit on UK and Scottish energy policy is unclear; however there may be impacts on funding for R&D, the construction of electricity interconnectors, the design of renewable energy support schemes, and the future functioning of and participation in the Internal Energy Market.

Following Brexit, it is not yet clear how or if UK Government energy policy will significantly change direction . Following the vote to leave the EU, the previous Secretary of State confirmed the Government's commitment to delivering policies to tackle the energy trilemma, with security of supply considered to be the "first priority".

Key pieces of primary legislation underpinning UK energy policy include the Climate Change Act 2008, and the Energy Act 2013. The former sets a target of at least an 80% cut in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, as well as a reduction in emissions of at least 34% by 2020; the latter reforms the electricity market by creating a capacity market to ensure security of supply, and replaces the previous support mechanism (renewables obligation) to implement contracts for difference which fix the price per unit received by low carbon generation, and reduce the commercial risks faced, whilst supporting investment.

Energy efficiency, and high energy prices, link directly with health and well-being. In Scotland, a household is defined as in fuel poverty if it needs to spend more than 10% of its income on fuel to maintain a satisfactory heating regime. It is caused by poor energy efficiency, low incomes, and high domestic fuel prices. Sustainable solutions to fuel poverty include improving the quality of housing stock and community heating schemes. UK wide measures designed to help consumers with their energy bills include obligations on energy suppliers to help vulnerable customers and those on low incomes with energy efficiency measures and energy saving advice services.

The promotion of renewable energy, the consenting of electricity generation and transmission development, and energy efficiency are currently devolved, with further powers to follow e.g. for the management of licences to exploit onshore oil and gas resources, and powers over supplier obligations regarding energy efficiency. This allows the Scottish Government to focus attention on advancing research, development and deployment in key areas, and gives Ministers some powers in governing the overall energy mix, including nuclear and other thermal generation via consenting powers.

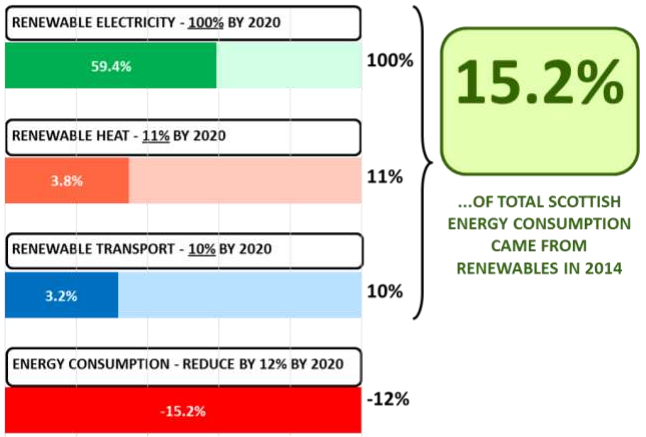

Overall Scottish policy is supported by key documents, as well as renewable energy generation and greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets. These targets include a 42% reduction in emissions by 2020 and an 80% reduction by 2050; as well as generating 100% total Scottish electricity consumption, and 11% of heat from renewables by 2020.

The Scottish Government's Draft Energy Strategy sets out its vision for the energy system in Scotland to 2050. It articulates priorities for an integrated system-wide approach that considers both the use and supply of energy for heat, power and transport. This strategy, alongside the most recent Scottish Climate Change Plan assume that by 2026/27 there will be net negative emissions from electricity generation through the deployment of bionenergy with carbon capture and storage. The strategy has three core themes:

A whole system view; examining where energy comes from and how it is used – for power (electricity), heat and transport

A stable, managed energy transition; determined by the need to further decarbonise the whole energy system, in line with Scottish emissions reduction targets

A smarter model of local energy provision; with local solutions to meet local needs.

Key proposals include a new all energy (heat, transport and electricity) renewables target of 50% by 2030 (up from 30% by 2020), and Scotland's Energy Efficiency Programme which undertakes to transform the energy efficiency and heating of all Scotland’s buildings by 2035. This energy efficiency programme is considered to be the cornerstone of the Government’s whole-system approach; pilot projects are currently underway, and it is expected to be formally launched in 2018.

Background

The recently published SPICe Briefing on Energy provides an introduction to key themes and global trends in the energy sector. It addresses reducing demand, renewable technologies, energy for electricity, transport and heat. The Executive Summary to this briefing provides a helpful context, as follows:

Energy can be thought of as a system, e.g. fuel burned in a car drives the engine and transports goods or people. Electricity is one of a number of different forms of energy; it is not a primary source. The rate of global energy consumption continues to rise, albeit at a reduced rate, and the wellbeing of most societies still relies predominantly on the availability of cheap fossil fuels. These however produce greenhouse gases (GHG), which play a significant role in changing the climate.

In recent years, common approaches to energy management have centred on developing a framework which ensures energy security, affordability, and tackles the environmental impacts of burning fossil fuels, known as the energy trilemma.

A key way to ensure energy security and maintain high standards of living is to reduce energy usage, as well as decarbonising the energy that is used. This is known as decoupling, and there are signs that this has started to happen through increasing output from renewable energy, as well as improvements to energy efficiency.

Many commentators and analysts believe that with consistent policy support, renewable energy sources can contribute substantially to human well-being by sustainably supplying energy and playing a part in stabilising the climate. However, to make this happen, the UK and the rest of the world must address key technical, social, environmental, economic and political issues. The Scottish Government considers the development of renewables to be particularly important; and their promotion, in particular to generate electricity, has increased markedly in the past decade. However, it remains a small part of the overall energy mix, amounting to only approximately 3% of total Scottish energy use in 2013.

Electricity is estimated to account for 22% of overall energy use in Scotland. Within this, in 2015, nuclear accounted for around 35%, coal for 17%, and gas for 4%. At present, the main form of renewable generation in Scotland is electricity from onshore wind, and hydro; however, there is expected to be further deployment of offshore wind and tidal generation in the next few years. The most recent figures show that renewables accounted for 59.4% of the gross annual consumption of electricity in 2015. There are nevertheless limits to the capacity of renewables; including visual intrusion; access to and expense of using electricity networks; expense of development to commercial deployment; and planning constraints.

The transport sector is thought to account for approximately 25% of total energy used. The distances travelled by all modes of motorised transport have risen in the last 40 years, and the vast majority of this growth is based on the use of fossil fuels. For GHG emissions and economic growth to be effectively decoupled, almost complete decarbonisation of road transport by 2050 will be required. Technological improvements alone are not thought to be sufficient to reduce emissions on the necessary scale, therefore behavioural change is vital.

Energy for heat accounts for approximately 53% of Scotland’s total usage, and that is further split between industrial and commercial (57%), and domestic (42%). Gas is the main fuel for heating, used by 79% of Scottish households. In the (mainly rural) areas off the gas grid, the heat market is fragmented with a large number of oil and LPG users. For GHG emissions and economic growth to be effectively decoupled in the UK, a largely de-carbonised heat sector is required by 2050 through a combination of reduced demand and energy efficiency, together with a massive increase in the use of renewable or low-carbon heating.

One of the challenges of delivering renewable heat energy is the difficulty in transporting it. Typically in the UK, heat is generated on individual premises, though in other European countries local and district heat networks are common, and it will be necessary to replace the gas in the grid with low carbon alternatives.

The Scottish Government 1provides the following figures.

This briefing builds on the subjects presented in the SPICe Briefing on Energy and provides an introduction to key energy policies and targets within a world, European, UK, and Scottish context.

Policy Context

World

Energy is tradable on world markets; indeed it drives global markets. Sources of energy for direct and indirect uses are positioned in chance geographical locations which bring considerable wealth to some areas, and make energy a politically and strategically sensitive and lucrative commodity. Scotland is very much involved in the world market. For instance:

North Sea oil and gas is traded globally, though imports are becoming more important

Scottish energy companies are part of larger energy groups, for example ScottishPower, one of the two big electricity generators and suppliers in Scotland, is owned by Spanish company Iberdrola

The European Marine Energy Centre in Orkney has tested technologies from companies based in Holland, Norway and many other countries

Mitsubishi Electric’s research and development headquarters are based in Livingston.

Addressing the environmental impacts of GHG emissions from fossil fuels (as well as other sources) is now an urgent concern, and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has been instrumental in seeking global agreements to do this.

A number of global initiatives and commitments on climate change have been achieved to date. In 1997 the Kyoto Protocol was agreed setting out a legally binding commitment for developed countries to reduce emissions by 2012. In 2010 the Cancún agreements noted that future global warming should be limited to less than 2oC above pre industrial levels. At Durban in 2011 over 120 countries proposed that a legal framework for reducing emissions be completed by 2015 and come into effect no later than 2020. In 2013 countries agreed to submit national plans for emission reductions by the first quarter of 2015 and for developed countries to make funding available to support developing countries reduce their emissions and adapt to climate change.

The latest meeting took place in place in Paris in December 2015. This sought to secure an agreement that binds nations to a global approach that reduces emissions in line with keeping global mean surface temperature rise to less than 2oC. As part of this initiative countries were asked to prepare and submit their emission reduction plans and proposals in advance. The meeting resulted in the adoption of the 1Paris Agreement. The Agreement is legally binding and includes a mix of legally binding commitments (e.g. ‘countries shall’) and non-legally binding commitments (e.g. ‘countries should’)23. No enforcement mechanism exists to penalise any party that does not comply, however the agreement establishes a committee that shall be ‘transparent, non-adversarial and non-punitive’ and ‘facilitate implementation and promote compliance’ with the agreement.

In light of these commitments, installing renewable energy technologies and reducing primary energy usage are seen as playing a key role in addressing climate change, and a number of studies into global energy supplies have been carried out.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported in 2011 that close to 80% of the world’s energy supply could be met by renewables by mid-century if backed by the right enabling public policies. It states that with “consistent climate and energy policy support, renewable energy sources can contribute substantially to human well-being by sustainably supplying energy and stabilizing the climate. However, the substantial increase in renewables is technically and politically very challenging”4. The Executive Director of the United Nations Environment Programme notes5:

Access to clean, modern energy is of enormous value for all societies, but especially so in regions where reliable energy can offer profound improvements in quality of life, economic development and environmental sustainability. Continued and increased investment in renewables is not only good for people and planet, but will be a key element in achieving international targets on climate change and sustainable development.

The SPICe Subject Profile on Climate Change provides further details.

Europe

Energy has been part of European integration from the very beginning (European Coal and Steel Community 1952, European Atomic Energy Community 1958), however energy policy was only made an explicit competence by the Lisbon Treaty in 2009.

EU policy is based on three pillars: the establishment of a single competitive energy market; emissions reduction; and security of supply. The European Commission (EC) states1:

These goals will help the EU to tackle its most significant energy challenges. Among these, our dependence on energy imports is a particularly pressing issue with the EU currently importing over half its energy at a cost of €350 billion per year. Other important challenges include rising global demand and the scarcity of fuels like crude oil, which contribute to higher prices. In addition, the continued use of fossil fuels in Europe contributes to global warming and pollution.

Key policy areas include1:

An Energy Union that seeks to ensure secure, affordable and climate-friendly energy for EU citizens and businesses by allowing a free flow of energy across national borders within the EU, and bringing new technologies and renewed infrastructure to cut household bills, create jobs and boost growth

An Energy Security Strategy which presents short and long-term measures to shore up the EU's security of supply

A resilient and integrated energy market for which new pipelines and power lines are being built to develop EU-wide networks for gas and electricity, and common rules are being designed to increase competition between suppliers and to promote consumer choice

Boosting the EU's domestic production of energy, including the development of renewable energy sources

Promoting energy efficiency

Safety across the energy sectors with strict rules on issues such as the disposal of nuclear waste and the operation of offshore oil and gas platforms.

To pursue these goals, the EU has formulated targets for 2020, 2030, and 2050.

The current Energy Strategy3 defines the EU's energy priorities between 2010 and 2020. Known as the 20-20-20 targets; by 2020, Member States have agreed to achieve:

A 20% reduction in EU greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels

Raising the share of EU energy consumption produced from renewable resources to 20%i

A 20% improvement in the EU's energy efficiency.

These targets were updated in January 2014, with EU countries agreeing a 2030 Framework for Climate and Energy4 which agrees to:

A 40% reduction in EU greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels

At least a 27% share of EU energy consumption produced from renewable resources

At least a 27% improvement in the EU's energy efficiency, to be reviewed by 2020 potentially raising the target to 30% by 2030

The completion of the internal energy market by reaching an electricity interconnection target of 15% between EU countries by 2030, and pushing forward important infrastructure projects.

The EC1 considers that together, “these goals provide the EU with a stable policy framework on greenhouse gas emissions, renewables and energy efficiency giving investors more certainty and confirming the EU's lead in these fields on a global scale”. Implementation of the 2030 Framework is part of the EU's contribution to the Paris Agreement on climate change.

The EU aims to achieve an 80% to 95% reduction in greenhouse gasses compared to 1990 levels by 2050; the Energy Roadmap 2050 analyses a series of scenarios on how to meet this target6.

Progress to date includes1:

Between 1990 and 2012, the EU cut greenhouse gas emissions by 18% and considers itself “well on track” to meet the 2020 target

The projected share of renewable energy in gross final energy consumption was 15.3% in 2014, up from 8.5% in 2005

25 countries are expected to meet their 2013/14 interim renewable energy targets

Energy efficiency is predicted to improve by 18% to 19% by 2020 – just short of the target. However, “if countries implement all the necessary EU legislation, the target should be reached”.

In order that renewables targets are achieved, the EU requires national action plans that set out sectoral targets, the projected technology mix, the route they will follow and the measures and reforms they will undertake.

A number of Directives enforce the above targets, including:

The Industrial Emissions Directive (2010/75/EU): seeks to reduce emissions of damaging pollutants, particles, and gases. Under a National Emissions Reduction Plan (NERP), industrial installations have been set finite annual emission allowances, or ‘bubbles’ for sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxide and dust (or particulate matter). Emission allowances can be traded with other NERP participating sites, however, the national ‘bubble’ is set to ensure an overall reduction in emissions.

The Renewable Energy Directive (2009/28/EC): sets an EU target of a 20% share of renewable energies in final energy consumption by 2020, as well as national targets for all Member States.

The Energy Efficiency Directive (2012/27/EU): establishes a framework of measures for the promotion of energy efficiency in the EU and sets a non-binding target of 20% energy efficiency improvements by 2020.

Launched in 2005, the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) is considered to be the “cornerstone” of the EU’s drive to reduce its emissions of GHG. The system works by putting a limit on overall emissions from high-emitting industry sectors which is reduced each year so that total emissions fall. Companies receive or buy emission allowances which they can trade with one another as needed, and they are fined if they do not buy adequate allowances to cover their emissions. This ‘cap-and-trade’ approach is considered to give companies the flexibility to cut their emissions in the most cost-effective way. More than 11,000 power stations and manufacturing plants in 28 EU member states, as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway are covered. Aviation operators flying within and between most of these countries are also covered. In total, around 45% of total EU emissions are limited by the scheme8.

A relatively high carbon price within the system is an important driver for investment in climate change mitigation technologies. The ETS is currently in its third phase, which is running from 2013 to 2020. Negotiations are also underway for Phase IV, which will run from 2021 to 2030, with plans for better targeted and more dynamic allocation of free allowances, and two new Funding Programmes. However, the ETS has been subject to criticism. It is not thought to be on course to deliver the EU’s long term targets, and not seen to be providing a carbon price that can drive the changes required to move to a low carbon economy9. The ETS is considered further in the following section on Brexit.

Under the Lisbon Treaty, Member States remain free to choose their energy sources, the structure of their energy supply, and how they support renewable energies within energy market rules. The EC considers that it is for each member state to decide on nuclear power10.

Funding

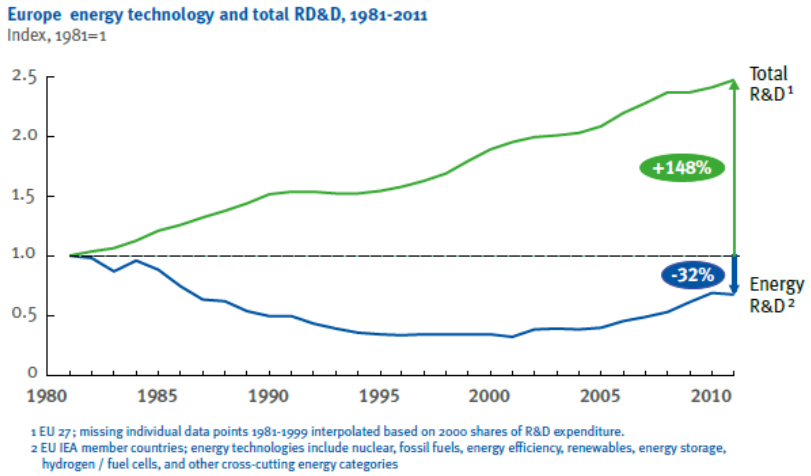

The development of pan-European renewables targets has had a positive effect on research and development activities, and the period from 2007-13 provided EU funding for some innovative programmes. Relevant funding streams include the Interreg, ERDF, FP7, and NER 300.

Energy supply and energy security issues are connected to a number of other policy areas. Many programmes and funds include objectives related to energy, energy efficiency, a low-carbon economy or climate action. It is difficult to clearly indicate all related EU funding because it is spread across many different budgetary headings.

Impact of BREXIT on UK/Scottish Energy Policy

Background

At present, membership of the EU requires the United Kingdom to comply with European legislation in the energy policy field, however as previously noted, the Lisbon Treaty reserves decisions about the energy mix to national governments. Although responsibility for energy policy in Scotland is shared between the UK and Scottish Governments (explored in detail in the next section), the UK Government is responsible for framing the UK position in European Union negotiations; the Scottish Government's Draft Energy Strategy1 states:

The European internal energy market is vital to delivering affordable energy and to driving decarbonisation and investment in renewables. EU legally-binding renewable energy and energy efficiency targets have played a defining role in stimulating the huge growth in renewable energy in Scotland, which has seen significant inward investment flows into Scotland. Internal market rules also ensure fair access for suppliers, set a framework for interconnection and provide protection for consumers. This contributes to lower energy costs, greater security of supply and the competitiveness of our businesses and the Scottish economy.

Climatexchange, Scotland's independent centre of expertise on climate change describes2 the UK’s energy system as “embedded in international networks of trade and infrastructure which have evolved over decades”. And states:

Brexit will not bring about energy independence – like the EU as a whole, the UK is a net energy importer and will still need to trade internationally, including with its nearest neighbours. Energy trade is reliant on capital intensive and ‘lumpy’ infrastructure which, once built, creates a collective incentive to utilise shared assets as efficiently as possible. For example, the UK is a key international trading hub for gas – and plays an important part in maintaining a ‘liquid’ European market for gas.

Professor Dieter Helm of Oxford University summarises the current situation by stating3 that the “uncertainties created by BREXIT […] unsurprisingly leave the future as clear as mud, and the mud is likely to persist for months or even years”.

Funding and Inward Investment

In a recent inquiry into Leaving the EU: negotiation priorities for energy and climate change policy, the House of Commons BEIS Committee (2017) found that there were no widespread concerns that “EU membership is damaging UK energy competitiveness or adversely affecting consumers”.

Evidence from Chatham House1 to the House of Commons Energy and Climate Change Committee's (ECCC) Inquiry on Leaving the EU: implications for UK energy and climate change policy 2 highlighted that the UK has received “very substantial funding for energy infrastructure projects from EU institutions in recent years”. For example, the European Investment Bank (EIB) has provided over €9 billion in long-term loans over the past five years. The UK is the biggest recipient of the EIB’s Climate Awareness Bonds for renewable energy and energy efficiency, securing 24% of total available funds. Similarly, structural and regional funds have provided €1.6 billion to support the transition to a low-carbon economy over the period 2014–20.

Whilst an EU exit is likely to impact on the availability of some funding for research and development in the energy sector, it is not clear whether it would be a definitive barrier, as some non-EU countries are actively involved in EU funded and co-ordinated projects e.g. Norway. The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies3 considers that (to date) there has been more funding for energy technology research and development within the EU than for countries within the EEA, as set out in the following table:

The ECCC2 pointed to previous inquiries showing that investor confidence in the UK energy sector had been affected due to policy changes following the 2015 general election, and that these “concerns not only persist, but are exacerbated by the additional policy uncertainty created by the EU referendum result” e.g. changes to passporting arrangements and financial regulation. Therefore, the vote to leave has “reduced already-weak investor confidence in the energy sector; the Government should therefore promote investment by providing clear signals on the direction of domestic energy policy to be followed throughout, and after, the exit negotiations, […]”.

Climatexchange5 has similar concerns, and notes that Brexit “may undermine the case for building the electricity interconnectors needed to enable market integration”. Furthermore, new investment is required over the coming decades to replace the UK’s ageing electricity generation fleet. To ensure projects go ahead and to avoid a costly risk premium, the UK government “needs to reassure investors that it will stand behind its contractual obligations and the integrity of the levy control framework which pays for low carbon investment”.

Internal Energy Market (IEM)

The IEM is a long-term project to liberalise and harmonise the energy markets of individual EU Member States. The key elements are liberalisation (the right to choose suppliers), third party network access (the right to access markets, supplies and customers) and unbundling (reducing the scope for the abuse of vertical integration).

These have enabled new gas and electricity suppliers to enter Member States’ markets, and have ensured that both domestic and industrial consumers are free to select their own suppliers. Related EU policies focus on the security of energy supplies and the construction of trans-European networks to transport gas and electricity. Ambitions to realise a “fully-integrated internal energy market” are laid out in the Energy Union Strategy1. The fully-integrated IEM intends to maximise competition by using interconnectors to allow unconstrained trade of energy. Helm2 considers that the IEM “is very much a British inspired creation”, however that, in spite of some recent EC progress it “has yet to be fully implemented after 25 years of trying […]”.

Professor Nick Butler3 states:

The proposed energy union is much more focused on developing common infrastructure and in ensuring that there is an open market across Europe. Presumably we will not now be part of that, although participation remains an option, for instance, in developing an advanced power grid across the North Sea if relations remain amicable. The member states of the Union manage to trade easily and successfully with Norway, which remains a non-member. There is no reason to think that the interconnection and trading links which already exist on straightforward commercial terms will not continue regardless of a UK exit from the European institutions.

Evidence to the ECCC4 has shown that the IEM has provided policy stability, increasing the UK’s ability to attract new energy infrastructure investment, and that continued participation in the IEM would reduce any investment hiatus arising from exiting the EU. In particular, the continued use and future construction of interconnectors may help to reduce the loss of access to EU funds, as well as helping the UK to capitalise “on the economies of scale that a pan-European energy market affords, with noted financial benefits relating to energy storage, cross-border balancing, reduced system redundancy, market coupling and capacity market integration”.

Participation in the IEM is however subject to the acceptance of a wide range of EU legislation and regulations, and evidence to the ECCC4 suggested that the existing Energy Community Treaty may provide a model for continued IEM participation. The Treaty allows some southern and eastern non-EU Member States to participate in the market, and counts Norway and Turkey amongst its observers. It requires non-EU countries to adopt the EU’s acquis communautaire related to energy, and in return provides technical and investment support with regards to energy security. The National Grid4 considered that any future relationship with the IEM should include:

Free trade of energy

ongoing implementation of existing EU energy packages and network codes (rules)

an agreement for the UK to help develop and to implement future EU policy, codes and market design.

National Grid further emphasised that if such a relationship seems unlikely to be secured, the Government will need to conduct a detailed analysis to ensure that risks to the current energy policy framework are understood and minimised. The ECCC broadly agreed4, recommending that:

In deciding the nature of the UK’s future relationship with the market, the Government will need to weigh the costs of associated legislation and regulation against the economic, security of supply and carbon reduction benefits afforded by IEM membership. We recognise that negotiations around this will be affected by broader issues, including freedom of movement.

Furthermore:

In the event that the UK loses its membership of but retains access to the IEM, the Government will need to identify new routes to shape the development of IEM policy. Without this the UK risks losing its role as an IEM ‘rule-maker’, instead becoming a ‘rule-taker’.

The global law firm Norton Rose Fulbright (NRF)8 considers that whilst the UK will theoretically be released from many obligations, increasing “interconnectivity with continental Europe will necessarily require co-operation with the EU internal energy market in any Brexit scenario. Because the UK Government has been at the forefront of efforts to liberalise and develop cross-border energy markets, we envisage that this cross-border policy direction is likely to endure”. NRF believes that climate change goals are unlikely to change, and that coal-fired plants will still close. Depending on what model for UK trade is negotiated, there may however be “more freedom both in the design and phasing out of renewable energy support regimes”.

EU ETS

As previously noted, the ETS is central to the EU’s approach to GHG emissions reduction. The House of Commons BEIS Committee1 heard evidence about difficulties with the current system relating to “the over supply of allowances and the financial crash of 2008, which drove down the carbon price due to reduced activity and emissions in the energy and industrial sector”, and stated that:

Emissions Trading Systems are in theory the most effective means of reducing emissions at lowest cost. The UK and EU benefit by being part of a wider system able to import and export carbon allowances to reduce emissions in a way that is most cost efficient. The EU ETS is also a good example of international collaboration and ambition to tackle climate change. In practice, the EU ETS is performing poorly, due to a low target and domestic policies causing oversupply of EU ETS permits.

The BEIS Committee1 therefore recommended that the Government “seeks to retain membership of the EU ETS until at least 2020”, and recommends that “longer term membership of the EU ETS should be conditional on progress of its future reform”.

Possible Options

Climatexchange1 considers that the “implications of the EU referendum will be felt for many years to come but whatever the form of engagement between a post-Brexit UK and the EU, it is clear that many ties will remain”.

Helm2 believes that for the rest of the EU, the UK’s departure is “bad news for energy and climate policies” because they are more efficient to implement at a Europe wide scale. He states:

A fully interconnected Europe, with integrated infrastructure networks for both electricity and gas, requires a lot less capacity to ensure security of supply. There is a big portfolio benefit. Then there are the advantages of matching intermittent and varied technologies through the grids. A proper European approach reduces costs, and increases security, and makes decarbonisation both cheaper and faster.

Helm2 sets out some possible options for future UK/EU energy relations:

Stay in the IEM, but likely to have to also be in broader single market, abide by its rules and accept some free movement of people

Leave IEM, but agree to abide by its rules

Leave IEM, then negotiate on energy trade, interconnectors and energy, and carbon taxes and permits. This could be one of the proposed sector-by-sector agreements, bilateral agreements on specific interconnectors, or it could be as a result of eventually getting direct membership of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and applying the Energy Charter rules (WTO 2002)

Another possible way, which may take some time to achieve, is to allow the Energy Union to “develop a life separate from, but related to, the EU, following the examples of other inter-governmental institutions in Europe”, as not everything “agreed between European countries needs to be via the EU and its formal membership structures”; examples include atomic power, defence and security arrangements, and human rights.

The House of Commons BEIS Committee4 heard from the the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, who acknowledged that co-operation with EU partners was generally mutually beneficial, and recommended that the UK Government, as part of its negotiations:

Seeks to avoid disruption to the energy sector and the domestic climate change agenda

Implements, as far as possible, arrangements mirroring the status quo

Seeks to provide as much clarity and stability as possible on domestic policy to support investment

Seeks to maintain ongoing access to the IEM

Resolves the particular difficulties faced by Northern Ireland, as it shares a single electricity market with the Republic of Ireland

Seeks to retain membership of the ETS until at least 2020. Longer term membership should be conditional on progress of its future reform.

Furthermore, the Committee is:

[…] concerned that the UK will become a “rule taker” outside the EU, complying with, but unable to influence, rules and standards. If our formal standards diverge too far from those applying in European countries, there is a risk that the UK could become a dumping ground for energy inefficient products.

UK Policy Framework

Reserved and Devolved Aspects of Energy Policy

Energy matters are largely reserved under Schedule 5 Head D of the Scotland Act 1998, and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy is responsible for UK Energy Policy. However, the Scottish Government has responsibility for the promotion of renewable energy generation, energy efficiency, and the consenting of electricity generation and transmission development. It also has responsibility for the environmental impacts of energy infrastructure through planning controls. In addition, Scotland has a part to play in helping the UK meet global and European climate change targets.

Whilst thermal generation is reserved, planning consent is devolved; therefore applications to build and operate power stations and to install overhead power lines are made to Scottish Ministers. Applications are considered where they are:

For electricity generating stations in excess of 50 MW

For overhead power lines and associated infrastructure, as well as large gas and oil pipelines.

Applications cover new developments as well as modifications to existing developments. For developments below these thresholds, applications are made to the relevant local planning authority. For marine energy (e.g. wave, tidal and offshore wind), applications are made to Marine Scotland.

The Scotland Act 2016 devolves further powers in relation to energy; including the management of licences to exploit onshore oil and gas resources in Scotland, and powers over supplier obligations regarding energy efficiency to the Scottish Government. There is also a consultative role for the Scottish Government and Parliament regarding renewables incentives. These powers have not yet been commenced, and will be by order of the Secretary of State for Scotland in due course – it is probable that secondary legislation for these powers would come before the Scottish Parliament's Economy, Jobs and Fair Work Committee.

UK energy policy is complex, and Scottish policy overlaps significantly with this in the context of a developing international framework. Policy areas and issues specifically relevant to Scotland are considered in the relevant section of this briefing, whilst those that are UK wide are considered below.

Recent Departmental Changes

Following Brexit, and the subsequent change in Government, it is not yet clear how or if UK Government energy policy will significantly change direction under the new Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (Greg Clark MP) (DBEIS). Following the vote to leave the EU, the previous Secretary of State (Amber Rudd MP) confirmed the Government's commitment to delivering policies to tackle the energy trilemma1:

As a Government, we are fully committed to delivering the best outcome for the British people – and that includes delivering the secure, affordable, clean energy our families and business need.

That commitment has not changed.

She went on to reiterate the UK Government’s support for dealing with climate change, and investing in the low carbon economy, in particular in renewable energy, however security of supply is considered to be their “first priority”. Other headline commitments also continue to stand, including:

Supporting up to 4GW of offshore wind, “providing the costs come down”

Reducing support for renewable energy, “technologies should be able to stand on their own two feet”

Remaining “committed to new nuclear power in the UK”, and the development of new gas plants

Closing all unabated coal-fired power stations by 2025.

The newly founded DBEIS is the result of a merger of the Department for Energy and Climate Change, and the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. On 18 July, the Prime Minister Theresa May stated2:

The Government is bringing together the departmental responsibility for business, industrial strategy and the science base with the departmental responsibility for energy and climate change policy. This change will mean that Government will be best placed to deliver the significant new investment and innovation needed to support the UK’s future energy policy. Furthermore, it will create a single department committed to ensuring that this investment and innovation fully utilises the UK science base and translates into supply chain benefits and opportunities in the UK.

One of the main challenges in tackling climate change is to try to reduce carbon emissions without jeopardising economic growth. This merger will enable a whole economy approach to delivering our climate change ambitions, effectively balancing the priorities of growth and carbon reduction.

Bringing together energy policy with industrial strategy will be beneficial to shaping a competitive business environment for energy intensive industries, including the UK steel sector. The new department will have a strong focus on the needs of customers, both business and domestic. It will help create the right economic conditions for growth and innovation.

This new department will focus on2:

Ensuring security of energy supply that families and businesses can rely on; including working across the oil, gas and electricity sectors to make sure the UK has a well-functioning, competitive and resilient energy system, and sufficient capacity to meet the future needs of energy users.

Keeping energy bills as low as possible for families and businesses.

Taking action on climate change alongside international partners to safeguard long-term economic and national security; as well as meeting national carbon target of at least an 80% emissions reduction by 2050, through efficient procurement of low carbon generation and otherwise in ways that keeps the cost of action as low as possible, to ensure value for money.

Managing the legacy of energy industries sustainably and responsibly; i.e. discharging legal liabilities effectively and managing the security risks from the legacies of nuclear and coal industries, and other energy liabilities.

Subsequently, Jesse Norman MP, the new Minister for Industry and Energy indicated4 that by creating DBEIS, the new Government was seeking to integrate climate change “across our whole industrial strategy”. Reaction to this has been broadly positive, with Business Green5 stating that a growing number of experts “have argued that the creation of DBEIS represents an opportunity to deliver a genuinely green industrial strategy”. This has been echoed by Lord Deben, chair of the CCC6. Dr Jim Watson. Director of UK Energy Research Centre7, said:

The new BEIS department faces huge challenges of course, especially given the government’s intention to negotiate withdrawal from the EU and the social divisions that were revealed by the referendum.

Two priorities are particularly important. First, there is a lot of work to do to close the gap between the high ambition set out in legislated carbon budgets and the policies in place to reduce emissions in a secure, affordable way. Second, there is an opportunity to integrate industrial strategy and energy policy more clearly – so that the UK can realise more of the economic and industrial benefits of the low carbon transition as well as meeting more traditional energy policy goals. Such benefits have started to emerge in technological areas such as offshore wind and smarter grid demonstrations – but there is a long way to go.

In early August 2016, a new cabinet committee on industrial strategy met8. Subsequently, in January 2017 a consultation called Building our Industrial Strategy was published; this closed in April 2017, and responses are currently being analysed9. This “modern industrial strategy” identified 10 pillars believed to be important to drive industrial policy across the “entire economy”, as follows:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Legislative Framework

Key pieces of primary legislation underpinning the UK's current energy policy include:

The Climate Change Act 2008: sets a legally binding target of at least an 80% cut in GHG emissions by 2050, as well as a reduction in emissions of at least 34% by 2020, against a 1990 baseline; implements a carbon budgeting system which caps emissions over five-year periods; creates the Committee on Climate Change; implements various reporting and monitoring programmes relevant to climate change and GHG emissions.

The Energy Act 2013: puts in place electricity market reform (EMR). This was designed to decarbonise electricity generation, keep the lights on, and minimise the cost of electricity to consumers. The most significant changes have been the creation of the capacity market and the implementation of contracts for difference (CfD) for renewables, to replace the renewables obligation. These are discussed in more detail below.

The UK also has a legally binding renewable energy target of 15% by 2020, as part of the EU’s overall target of 20% renewables by that date. The UK Government’s key strategy in this area is the National Renewable Energy Action Plan (the publication of which fulfils EU requirements under the Renewables Directive)1; a Renewable Energy Roadmap sets out how this target can be achieved2.

Electricity and Gas Regulation

Ofgem (the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets) has, as its primary role to protect the interests of existing and future electricity and gas consumers; it also has a wider duty to contribute to sustainable development. This is done in a number of ways, including:

Promoting value for money

Promoting security of supply and sustainability, for present and future generations of consumers, domestic and industrial users

The supervision and development of markets and competition

Regulation and the delivery of government schemes.

Ofgem is funded by the energy companies, and has principal offices in Glasgow and London.

The Energy Ombudsman helps to resolve consumer complaints about gas and electricity companies. The Consumer Futures Unit at Citizens Advice Scotland is the independent gas and electricity watchdog.

Transmission Charging

Given the challenging location of many sources of renewable energy (offshore and remote rural), significant changes are being made to the electricity network. Current infrastructure is widely considered not to be fit for the purpose of accepting new, dispersed small scale renewables projects, and up to April 2016, charges for access to and use of the transmission network were significantly higher for generators furthest from the main centres of demand. This was known as locational charging, and the Scottish Government1 believed that it worked “against the interests of growing Scotland's renewable energy industry”.

National Grid sets Transmission Network Use of System (TNUoS) tariffs for generators and suppliers. These tariffs serve two purposes: to reflect the transmission cost of connecting in different parts of the country and to recover the total allowed revenues of onshore and offshore transmission owners.

In July 2014, Ofgem concluded Project TransmiT, its review of electricity transmission charging and associated connection arrangements, and implemented a new charging methodology (called WACM2) in April 2016; their decision states2:

WACM 2 would split the TNUoS tariff for generators into two parts: the Peak Security tariff and the Year Round tariff. Only conventional generators would be charged the former but all generators, including intermittent ones, would be subject to the latter. This […] reflects the fact that intermittent generators are not assumed to contribute to meeting peak security.

Electricity Market Reform

EMR aims to improve the relative attractiveness of the UK for investors in the electricity market by creating a long-term, stable and predictable electricity market, providing greater revenue certainty. EMR was implemented in the Energy Act 2013. The most significant changes to how the electricity market works as a result of EMR were the creation of the capacity market and the implementation of contracts for difference (CfD) for renewables, to replace the renewables obligation.

Capacity Market: As part of the EMR, the aim of the Capacity Market is to ensure there is backup available to the grid to meet any expected shortfall in electricity supply when demand is high1. The focus is on ensuring security of supply in the medium term. It provides a regular payment to reliable forms of electricity generation, in return for the capacity being available when the system is tight. An auction to award capacity agreements is held four years ahead of the year in which it may be required. A second auction is held one year ahead of delivery if added capacity is thought to be needed. It was envisaged that the policy would encourage new cleaner forms of supply and innovative forms of electricity demand management, but this has not necessarily been the case. Diesel generators and older coal generators were unexpectedly successful in auctions in December 2014 and 2015, leading to criticism of how the policy has been implemented23. As a result, the Government consulted on changes to the Capacity Market4, and held a further auction in January 2017 where gas and coal/biomass fired plants secured the majority of contracts5. SSE’s Peterhead power station did not secure an agreement, with the company stating6:

The station’s location means it is required to pay significantly higher Transmission Entry Capacity (TEC) costs than other power stations on the electricity system. This puts it at a disadvantage in the Capacity Market auction. In light of these provisional auction results, the fact that Peterhead has failed to secure a contract in any of the three previous Capacity Market auctions, and other economic considerations, SSE will be reviewing future options for the station over the coming months and will engage with all stakeholders during this review. The review will not impact current operations at the station.

Contracts for Difference: CfD were introduced by the 2010 Coalition Government to replace the Renewables Obligation (RO) as part of EMR. These contracts work by fixing the prices received by low carbon generation, reducing the risks they face, and ensuring that eligible technology receives a price for generated power that supports investment. CfDs also reduce costs by fixing the price consumers pay for low carbon electricity (known as the strike price). This requires generators to pay money back when electricity prices are higher than the strike price, and provides financial support when the prices are lower. More detail on CfDs can be found in the section on Encouraging Renewables.

Levy Control Framework: The Government has placed the obligation of financing a number of its energy and climate change policies onto energy companies, rather than funding the schemes directly through general taxation. Energy companies then recover the cost of these levy-funded schemes from consumers through bills. The LCF was therefore established by DECC and HM Treasury in 2011 to cap the cost of levy-funded schemes and ensure that DECC "achieves its fuel poverty, energy and climate change goals in a way that is consistent with economic recovery and minimising the impact on consumer bills". It sets annual limits on the overall costs of all DECC’s low carbon electricity levy-funded policies until 2020/217.

The Government announced in July 2015 that the latest forecasts under the LCF had shown that spend on renewable energy subsidy schemes would be higher than expected, stating8 that they had:

[…] set a limit of £7.6bn in 2020-2021 (in 2011/12 prices), so the current forecast is £1.5bn above that limit. This is due to accelerated developments in technological efficiency, higher than expected uptake of demand-led schemes and changes in wholesale prices. This means that the forecast of future spend under the LCF is now estimated at around £11.4bn (in nominal prices) or £9.1bn (in 2011/12 prices) in 2020/21. The Government is determined to bring these costs under control to protect consumers and provide a basis for investment in clean electricity in future.

Therefore, a number of measures were put in place, including the closure of the previous scheme (known as the Renewables Obligation) to new onshore wind.

The Nuclear Option

Nuclear power has been part of the UK’s energy mix for over 50 years. In the 1990s, 30% of electricity output was from nuclear power. However, as stations have grown older and some have closed, the contribution of nuclear power has declined. There are currently eight nuclear stations across England, Scotland and Wales providing around 21% of electricity consumed. In October 2015, the then Energy Secretary Amber Rudd MP stated1:

We are tackling a legacy of under-investment and building energy infrastructure fit for the 21st century as part of our plan to provide the clean, affordable and secure energy that hardworking families and businesses across the country can rely on now and in the future.

[…]

The Government will support new nuclear power stations as we move to a low-carbon future. Hinkley Point C will kick start this and is expected to be followed by more nuclear power stations, including Sizewell in Suffolk and Bradwell in Essex. This will provide essential financial and energy security for generations to come.

Following a review of the Hinkley Point C project, and a revised agreement with EDF (the controlling stakeholder), the Government decided to proceed with the project in September 20162.

The subject of radioactive waste remains politically sensitive. The Committee on Radioactive Waste Management (CoRWM) is key to developments in this area, and is currently scrutinising and advising on policies for the long term management of higher activity radioactive wastes3.

Research is ongoing in the area of nuclear fusion, that is fusing nuclei together, a process which produces a lot of energy, but is decades from commercial deployment. In August 2016 a new Chief Executive, Professor Ian Chapman, was appointed to lead the UK Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA), which carries out fusion energy research on behalf of the Government4.

As set out on in the section on UK Policy Framework, Scottish Ministers have powers to consent all power stations over 50MW. The Scottish Government’s position on nuclear power is that the currently operating plants at Hunterston and Torness “should not be replaced with new nuclear generation, under current technologies”5.

Encouraging Renewables

A number of schemes are currently in place to encourage the use of renewable technologies, as follows:

The Renewables Obligation (RO) is currently the main support scheme for existing renewable electricity projects in the UK. It places an obligation on UK suppliers of electricity to source an increasing proportion of their electricity from renewable sources. A Renewables Obligation Certificate (ROC) is issued to an accredited generator for renewable electricity generated and supplied to customers. Different technologies attract differing numbers of ROCs per megawatt hour of renewable output, depending on commercial viability e.g. onshore wind receives 0.9 ROCs, whilst tidal stream and wave technology receives 5. Suppliers meet their obligations by presenting sufficient ROCs. Where suppliers do not have sufficient ROCs to meet their obligations, they must pay an equivalent amount into a fund, the proceeds of which are paid back to those suppliers that have presented ROCs. The Government intends that suppliers will be subject to a renewables obligation until 2037. Under EMR, the RO closed to new entrants from all technologies on 31 March 2017; it closed for onshore wind on 31 March 2016, and has been replaced by Contracts for Difference.

As previously noted, Contracts for Difference fix the price per MWh received by low carbon generation, and reduce the commercial risks faced, ensuring that eligible technology receives a price for generated power that supports investment. CfDs are now the only option of support for all low-carbon electricity generating technologies above 5MW. CfDs offer support for 15 years and, unlike the RO which provides a fixed payment per MWh, CfD generators essentially receive a top-up payment between the market price and a competitively set ‘strike price’. If the market price rises above the agreed ‘strike price’ the contracted generator will be required to pay back the difference. The first CfD auction took place in October 2014 with the results announced in early 2015, a total of 27 projects were selected to share £315m worth of contracts. Following a delay, the second auction took place in March 2017, and made £290m available for technologies such as offshore wind, anaerobic digestion, wave and tidal stream1.

One of the key issues for Scotland in relation to subsidies for onshore wind and the availability of CfD in particular, relates to the provision of support for wind energy on the Western Isles, Orkney, and Shetland. The UK Government2 consulted on this in late 2016, and feedback is currently being analysed. This is supported by the Scottish Government who note some of the challenges posed by transmission charging and grid access on these islands, and state3:

Wind projects on Scotland's remote islands would capture some of Scotland's best wind resource. These projects can generate high efficiency low carbon electricity and deliver significant local economic benefit to some of the most economically fragile areas in Scotland.

Island wind projects are defined by a series of unique characteristics that set them apart from onshore projects on the mainland […]. They have significantly higher load factors than average GB mainland projects - on average 27-57% higher - and are cost competitive when compared with offshore wind and several other forms of low carbon generation.

The Feed in Tariff Scheme (FiTS) encourages investment in small-scale low carbon electricity generation, and requires Licensed Electricity Suppliers (FIT Licensees) to pay a generation tariff to householders or other small-scale generators (whether or not such electricity is exported to the grid) and an export tariff to them where it is also exported to the grid. The latest report4 shows that just over 756,379 installations were registered in Great Britain at the end of 2015 with solar PV making up 99%. The installed capacity of small scale generators amounted to just over 4.4GW. In Scotland, there were 53,804 installations, with a capacity of 464MW; the majority of these were solar PV (46%), with wind (39%) and hydro (14%) making up much of the rest.

The Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) provides long term support for domestic and non-domestic renewable heat technologies, (e.g. household solar thermal panels or industrial wood pellet boilers). The scheme makes payments to those installing eligible technologies that qualify for support, year on year, for a fixed period of time. It is designed to cover the difference in cost between conventional fossil fuel heating and renewable heating systems (which are currently more expensive), plus an additional rate of return on top. Scotland has a higher than population share in the RHI, with 20% of all GB accredited installations – the majority of these are air source heat pumps (46%), followed by biomass boilers (35%)5.

Retail Markets and Affordability

The current Government's position (and that of the previous Coalition Government and Labour Government) is to promote competition in the wholesale and retail markets.

A number of interventions have been made in the last decade, including Ofgem’s Energy Supply Probe1, Retail Market Review2, and Assessment of Competition in the Energy Market3. Most recently, Ofgem asked the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) to conduct an Energy Market Investigation in June 2014. In referring the matter to the CMA it was intended to be a once and for all investigation as to whether or not there are further barriers to effective competition, because the CMA has more extensive powers that can address any long-term structural barriers to competition. This concluded in June 2016 and reported4:

[…] that 70% of domestic customers of the 6 largest energy firms are still on an expensive ‘default’ standard variable tariff. As these customers could potentially save over £300 by switching to a cheaper deal, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) will be enabling more of them to take advantage. The CMA has found that customers have been paying £1.4 billion a year more than they would in a fully competitive market.

Over 30 measures were proposed, including ordering suppliers to give Ofgem details of all customers who have been on their default tariff for more than 3 years, which will be put on a secure database to allow rival suppliers to contact customers by letter and offer cheaper and easy-to-access deals based on their actual energy usage. This database is expected to “go live” in spring 20185.

More information can be found the House of Commons Library Briefing on Current Energy Market Reforms in Great Britain.

Demand Reduction

Energy efficiency, and high energy prices, link directly with health and well-being. A household is defined as in fuel poverty if it needs to spend more than 10% of its income (including benefits) on fuel to maintain a satisfactory heating regime. This is considered to be 21oC for the main living area and 18oC for other occupied rooms during daytime hours. It is caused by poor energy efficiency, low incomes, and high domestic fuel prices. Reductions in fuel poverty which are attributable to lower energy prices, and not improvement of housing stock, leave people vulnerable to increasing energy prices, which can lead back to fuel poverty. Sustainable solutions to fuel poverty include improving the quality of housing stock and community heating schemes.

UK wide measures designed to help consumers with their energy bills include:

Taxpayer-funded payments principally the Winter Fuel Payment and the Cold Weather Payment

Obligations on energy suppliers that are funded by all energy bill payers, principally to help vulnerable customers and those on low incomes with energy efficiency measures (Energy Company Obligation) and discounts on electricity bills (Warm Home Discount).

Energy saving and other energy advice services.

The previous Government’s flagship policy, called the Green Deal, a UK wide finance system that prevented consumers paying upfront costs to carry out energy efficiency improvements to houses and non-domestic properties was closed in July 20151.

More information can be found in the SPICe Briefing on Fuel Poverty in Scotland.

There are three key sectors where demand reduction is imperative and the following table sets out the main actions in these areas at a UK level; some of these require partnership working with the Scottish Government.

| Sector | Key Actions |

| Business | Market mechanisms to reduce GHG emissions – including the ETS for larger organisations, and other emissions trading agreements for smaller private companies and public bodies. The UK has around 1,000 ETS participants (with around 100 of these in Scotland). The ‘traded sector’, i.e. sectors covered by the ETS, will account for over 50% of the emissions reductions needed to meet UK targets to 2020, when emissions are expected to be 21% lower than in 2005.Green Investment Bank established in 2012, and located in Edinburgh. It seeks to bridge the gap between venture capital and the green economy by providing finance for low carbon infrastructure and supporting long-term, balanced growth. It has recently been sold to Australian bank Macquarie for £2.3bn2. |

| Households | The Energy Company Obligation (ECO), introduced in 2012, places an obligation on the larger energy suppliers to support energy efficiency and heating measures that will reduce domestic carbon dioxide emissions and fuel bills. It is funded via obligated energy suppliers, with costs recouped through electricity bills, and it is split into three parts: Carbon Emissions Reduction Obligation – promotes roof insulation, cavity wall insulation, and connections to district heating systems; Carbon Saving Community Obligation – supports insulation measures and connections to domestic district heating systems in areas of low income; Home Heating Cost Reduction Obligation - provides measures which improve the ability of low income and vulnerable households to heat their homes.The Scotland Act 2016 devolves the powers to design how such ‘supplier obligation’ schemes are implemented; further information on Scotland’s new approach can be found below. |

| Transport | Inclusion of aviation in the ETS, and support for the early market for electric vehicles. |

Key organisations working on energy efficiency issues are:

Energy Saving Trust - non-profit organisation, funded both by Government and the private sector, with the aim to cut GHG emissions by promoting the sustainable and efficient use of energy.

Carbon Trust - independent company funded by Government to help the UK move to a low carbon economy by helping business and the public sector reduce carbon emissions now and capture the commercial opportunities of low carbon technologies.

Transport

In 2016, estimated GHG emissions from transport (excluding international aviation and shipping) amounted to approximately 32% of total UK emissions1. Addressing emissions from transport by shifting to low carbon modes is therefore considered to be of paramount importance. The Department for Transport Business Plan 2015 – 2020 undertakes to2:

Ensure transport plays its part in delivering the government's climate change obligations

Contribute to delivery of the national air quality plan

Double the number of journeys made by bicycle

Deliver the ‘Road investment strategy’ ring-fenced funds for air quality, environment, growth and housing, innovation, cycling, safety and integration

Invest £300 million to mitigate the worst impacts of noise on those living close to the strategic road network, support the transition to low-carbon road transport, improve local water quality and resilience to flooding, maintain an attractive landscape, work to halt the loss of biodiversity and reduce light pollution from roads

Replace biodiversity lost in the construction of HS2 by providing replacement habitats and enhancing existing habitats

Work to secure agreement on a new global market-based measure to tackle carbon emissions from international aviation.

Scotland

As previously noted, UK energy policy is complex, and Scottish policy overlaps significantly with this in the context of a European framework. The promotion of renewable energy, the consenting of electricity generation and transmission development, and energy efficiency are currently devolved, with further powers to be devolved e.g. for the management of licences to exploit onshore oil and gas resources, and powers over supplier obligations regarding energy efficiency allowing considerable attention to be focussed on advancing research, development and deployment in these key areas, and giving Scottish Ministers some powers in governing the overall energy mix, including nuclear and other thermal generation via consenting powers. The Scottish Government1 recognises:

[…] that much of Scotland’s energy policy currently remains reserved, the Scottish Government will continue to work with the UK Government and the GB energy regulator (Ofgem) and System Operator (National Grid) to create an environment that encourages efficient investment in new, clean generation and sets an appropriate regulatory framework to maintain secure supplies and enhance system flexibility. The Scottish Government’s priority is to ensure the market works for all consumers, and particularly those vulnerable to fuel poverty.

Encouraging Renewables

Overall policy is supported by key documents, as well as renewable energy generation and GHG emissions reduction targets, as follows:

2020 Routemap for Renewable Energy: This, and subsequent updates, sets out a framework for action on renewable energy. It identifies what needs to happen and by when to achieve national targets and objectives. It proposes tougher 2020 targets than both the UK and EU ones, these are set out below12.

Heat Policy Statement: sets out the framework for achieving a resilient and affordable low carbon heat system for households, organisations and industry. It details Scotland’s heat hierarchy; firstly reducing the need for heat; secondly by ensuring an efficient heat supply; and lastly through the effective use of renewable or low carbon heat sources. It also undertakes to largely decarbonise the heat sector by 2050 with significant progress by 20301.

Low Carbon Economic Strategy: sets out the aspiration for a shift to a low carbon economy, and was incorporated into the Government’s 2015 Economic Strategy refresh as a new Strategic Priority. The Low Carbon Economic Strategy set out a number of indicators to demonstrate the impact of the move to a low carbon economy45. The SPICe Briefing on Scotland’s Economic Strategy provides further details.

Community Energy Policy Statement: sets out the ambition to see community energy mainstreamed within a whole systems approach, with opportunity for community ownership and control in areas such as generating low carbon energy, improving energy efficiency, and generating, distributing and storing energy6.

Electricity Generation Policy Statement: examines the way in which Scotland generates electricity, and considers the changes necessary to meet domestic targets. It considers the sources from which electricity is produced, the amount that is used to meet domestic needs and the technological and infrastructural advances which will be required to 2023 and beyond. It also undertakes to largely decarbonise the electricity sector by 20307.

The Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 binds the Scottish Government to cut GHG emissions significantly by 2050. The following table compares GHG emissions targets with those for renewables:

| % reduction in emissions from 1990 levels | % of electricity generated from renewables | % of heat to be generated from renewables | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| By 2020 | By 2050 | By 2020 | By 2020 | |

| Scotlandi | 42 | 80 | 100 | 11 |

| UK | 34 | 80 | 30 | 12 |

| EUii | 20 | 80-95 | 20 (of all energy) | 20 (of all energy) |

As well as the above emissions reduction targets, the 2009 Act places climate change duties on Scottish public bodies, and recognises the need for encouraging low carbon behaviour. It also requires Scottish Ministers to produce a plan outlining specific proposals and policies for meeting those targets, and describing how these proposals and polices contribute to the 2020 and 2050 targets.

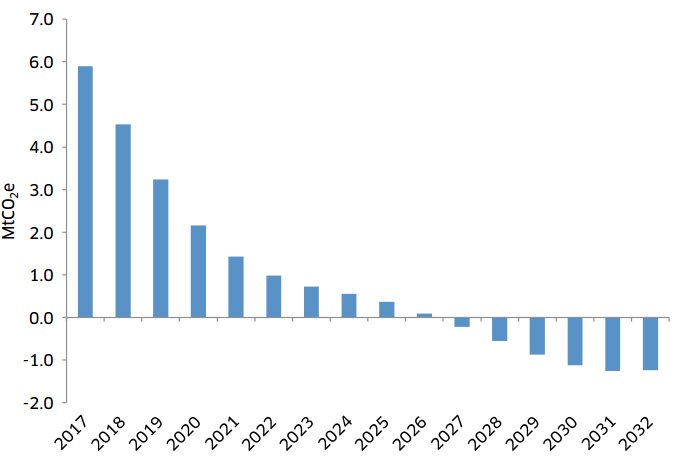

The third of these plans (known as the Climate Change Plan (CCP)) was published in January 2017 and is structured around the key sectors of electricity; transport; residential; services (business and public sector); industry; land use; waste; and agriculture. For each of these sectors, policies to reduce GHG emissions are identified, as are a number of proposals for further consideration8.

The CCP shows the following graph for electricity generation carbon envelopes for the next 16 years which assumes that by 2026/27 there will be net negative emissions from electricity generation, and states:

From the late 2020s, Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), along with gas from plant material and biomass waste, has the potential to remove CO2 from the atmosphere (i.e. negative emissions). CCS will be critical in heat, industry and power sectors.

Emissions pathway for the electricity sector 2017-2032

Further details are available in the SPICe Briefing on the Draft Climate Change Plan and Scotland's Climate Change Targets.

The National Planning Framework 3 (NPF)9 and Scottish Planning Policy (SPP)10 are also relevant to encouraging and siting renewable technologies. These documents are explored in more detail in the SPICe Briefing on Energy Generating Stations: Planning and Approval.

In it's Programme for Government 2016-1711 the Scottish Government announced that it will bring forward a new Climate Change Bill, including a new 2020 target of reducing Scottish emissions by more than 50%. The Scottish Government intends to consult on proposals for the Bill, based on the advice of the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) 12 in 2017.

Scotland's Energy Strategy

The CCC has suggested that scenarios compatible with Scottish climate goals would see1:

An electricity system powered solely by renewables, or generation fitted with carbon capture by 2030.

Two-thirds of new cars and vans sold being electric by 2030.

Nearly a fifth of homes fitted with heat pumps by 2030 (430,000 heat pumps installed).

Such scenarios would require the equivalent of an eight fold increase in the amount of energy generated from wind (compared to 2013), and a 65 fold increase in the proportion of new vehicles that are sold being electric. Whilst ambitious, examples from elsewhere in Europe provide some confidence; in 2015 nearly 30% of all cars sold in Norway were electric, in 2014 Austria generated renewable electricity equivalent to 70% of their gross electricity use and in a number of European countries sales of heat pumps now exceed 100,000 each year.

A Draft Energy Strategy (ES)2 was published for consultation alongside the CCP, this:

[…] sets out the Scottish Government’s vision for the future energy system in Scotland, to 2050. It articulates the priorities for an integrated system-wide approach that considers both the use and the supply of energy for heat, power and transport.

The ES is a detailed document, published with three supporting consultations:

Consultation on Heat & Energy Efficiency Strategies, and Regulation of District Heating

National Infrastructure Priority for Energy Efficiency - Scotland's Energy Efficiency Programme

The Minister for Business, Innovation and Energy when launching the ES stated3:

Our climate change ambitions underpin all the choices that are laid out in the draft strategy and have, in turn, been determined by our commitments under the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009. The strategy has been developed in concert with, and as a companion to, the draft climate change plan […].

This strategy has three core themes:

A whole system view; examining where energy comes from and how it is used – for power (electricity), heat and transport. This approach recognises the interactions and effects that the elements of the energy system have on each other. Scotland’s Energy Efficiency Programme is considered to be the cornerstone of this approach, and is set out in more detail below

A stable, managed energy transition; determined by the need to further decarbonise the whole energy system, in line with emissions reduction targets set out in the current Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009, which requires an 80% reduction in GHG emissions across the entire economy and society between 1990 and 2050

A smarter model of local energy provision; with local solutions to meet local needs. These decentralised energy systems create the potential for local energy economies. Heat, electricity and storage technologies combined with demand management and energy efficiency measures on an area-by-area basis could realise substantial local economic, environmental and social benefits.

Key proposals for consultation include:

A new all energy (heat, transport and electricity) renewables target of 50% by 2030 (up from 30% by 2020), this underpins a whole-system approach to energy policy

By 2035, through SEEP the energy efficiency and heating of all Scotland’s buildings will be transformed so that, wherever technically feasible, and practical, they are near zero carbon. SEEP is considered to be the cornerstone of the Government’s whole-system approach

Increasing the target for community and locally owned energy to 1GW by 2020, and 2GW by 2030 (the target of 500MW by 2020 was reached in 2015)

At least half of newly consented renewable energy projects will have an element of shared ownership by 2020

Creating a government owned energy company (GOEC) to help the growth of local and community projects

Creating a Scottish Renewable Energy Bond in order to allow savers to invest in and support Scotland’s renewable energy sector

The renewables industry to make Scotland the first area in the UK to host commercial onshore wind development without subsidy.

Demand Reduction

In Scotland, the number of households in fuel poverty rose consistently from 2002 - 2014, however the most recent Scottish House Conditions Survey1 shows that it declined by around 4% in 2015 to an estimated 748,000 households. Fuel poverty is particularly high in rural areas due to a combination of demographic factors (older households), infrastructure (properties off the gas grid) and matters relating to the housing stock (more detached and hard to insulate homes). The policy areas of energy efficiency and fuel poverty are very closely linked, although not mutually exclusive. As previously noted, the Scotland Act 2016 devolves how supplier obligations in relation to energy efficiency and fuel poverty are designed and implemented in Scotland.

Energy efficiency is now considered to be a National Infrastructure Priority, NPF32 undertakes to create a step change in the energy efficiency of homes, and states:

Much of our energy infrastructure, and the majority of Scotland’s energy consumers, are located in and around the cities network. The cities network will also be a focus for improving the energy efficiency of the built environment. A key challenge, but also a significant opportunity for reducing emissions, lies in retrofitting efficiency measures for the existing building stock