Draft Budget 2018-19

This briefing summarises the spending and tax plans contained within the Scottish Government's Draft Budget 2018-19. Two other briefings have been published by SPICe - one on the tax proposals of the Scottish Government and one on the local government settlement. More detailed presentation of the budget figures can be found in our Draft Budget spreadsheets. Infographics created by Andrew Aiton, Kayleigh Finnigan, Laura Gilman.

Executive Summary

Draft Budget 2018-19 will be remembered for the restructuring by the Scottish Government of Scottish Income tax rates and bands. Instead of the current three bands, the Scottish Government propose having five bands in 2018-19, set at rates of 19%, 20%, 21%, 41% and 46%. A briefing on the Tax proposals of the Draft Budget is published alongside this briefing.

It was also the first budget where the Scottish Fiscal Commission produced forecasts for the devolved taxes and Scottish economy. The SFC was markedly more cautious with its economic growth forecasts than any other Scottish forecaster and anticipates rates of Scottish growth significantly lower than the Office for Budget Responsibility's UK forecasts.

The proposed income tax policy changes are forecast to generate an additional £164m in 2018-19 relative to existing Scottish Government income tax rates and bands.

For the Scottish budget to be better off than it would otherwise have been without fiscal devolution, the SFC forecasts need to exceed the size of the block grant adjustment now made to the budget to account for taxes being devolved to the Scottish Parliament. The SFC forecast that total devolved tax receipts will exceed the block grant adjustment by £366m in 2018-19, which will more than compensate for the Resource budget reductions predicted after the UK Budget 2017 on 22 November. Forecast tax receipts will ultimately be reconciled with outturn when final tax receipts are known.

Draft Budget 2018-19 allocates budgets for a single year, despite the overall spending envelope being known through to 2019-20. This will be the fourth consecutive Draft Budget that has allocated monies for a single year.

In terms of the amounts being allocated by Draft Budget 2018-19, Total Managed Expenditure in 2018-19 will exceed £40bn for the first time. Of this, the discretionary element of the Budget is the Resource and Capital allocations, which total just under £32bn. Resource expenditure will increase after inflation by 0.9% in 2018-19 and Capital (including Financial Transaction and Borrowing) by 10.3%.

Health and Sport remains the largest spending area by some distance, comprising 41.4% of the total discretionary spending power. The next largest is Communities, Social Security and Equalities, which includes Local Government and comprises 27.8% of Resource plus Capital.

As in previous years, a number of different interpretations can be put on the allocation to local government. A dedicated detailed briefing on local government is published alongside this briefing. The core local government revenue settlement (General Revenue Grant plus Non Domestic Rates Income) is shown as falling by 2% (-£184m) in real terms between 2017-18 and 2018-19. When Specific Revenue Grants are taken into account, there is a small cash increase in Total Revenue funding for 2018-19 (+£3m). In real terms, this results in a reduction of 1.4% (-£135m).

These are draft proposals and commence a period of parliamentary scrutiny and political negotiation as the Scottish Government seeks a majority support from MSPs for 2018-19 Scottish tax and spend.

Context

Draft Budget 2018-191 was published on 14 December 2017 and presents the Scottish Government's draft spending and tax plans for 2018-19. This commences a period of parliamentary scrutiny and political negotiation as the Government seeks parliamentary support for its tax resolutions and budget bill in advance of the new financial year.

The 2018-19 draft budget contains the first devolved tax forecasts undertaken by the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC), which was established on a statutory basis on 1 April 2017. As well as producing point estimates for each of the devolved taxes (including non-domestic rates income) for the next 5 years, the SFC is also tasked with producing forecasts for Scottish economic growth and spending forecasts for the newly devolved social security areas.

The economic outlook for Scotland continues to be uncertain. There is still a lack of clarity about what a final Brexit deal might look like, as well as ongoing challenges in the north sea oil and gas sector and a projected decline in the working age population. However, the Scottish labour market has held up well, with employment currently standing at 74.9% and unemployment at 4.1%,2 albeit earnings growth has not kept pace with inflation.

Economic growth has been quite weak in recent times, which combined with more people in work, implies that Scottish productivity (the average contribution of each worker to national output) has been disappointing.

In its Economic Commentary published two days before the draft budget, the Fraser of Allander Institute stated:

on balance, the combination of over two years of weak growth, a projected decline in Scotland's working age population, and ongoing challenges in the oil and gas sector, mean that Scotland will do well to match UK Growth over the next two years3

The SFC has forecast economic growth of 0.7% in 2018, and generally has significantly more cautious Scottish forecasts for growth than other economic forecasters (see table 1 below).

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fraser of Allander4 | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.4% | 1.4% |

| Ernst & Young5 | 0.8% | 1.4% | 1.6% | 1.7% |

| PWC6 | 1.3% | 1.2% | ||

| Scottish Fiscal Commission7 | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 0.6% |

The SFC also includes forecasts for 2021 (+0.9%) and 2022 (+1.1%).

Like the SFC for Scotland, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) is mandated to produce economic growth forecasts for the UK. The OBR growth forecasts for the UK are presented in table 2 and are significantly higher than the SFC's Scottish forecasts.

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 1.3% |

The overall budgetary outlook

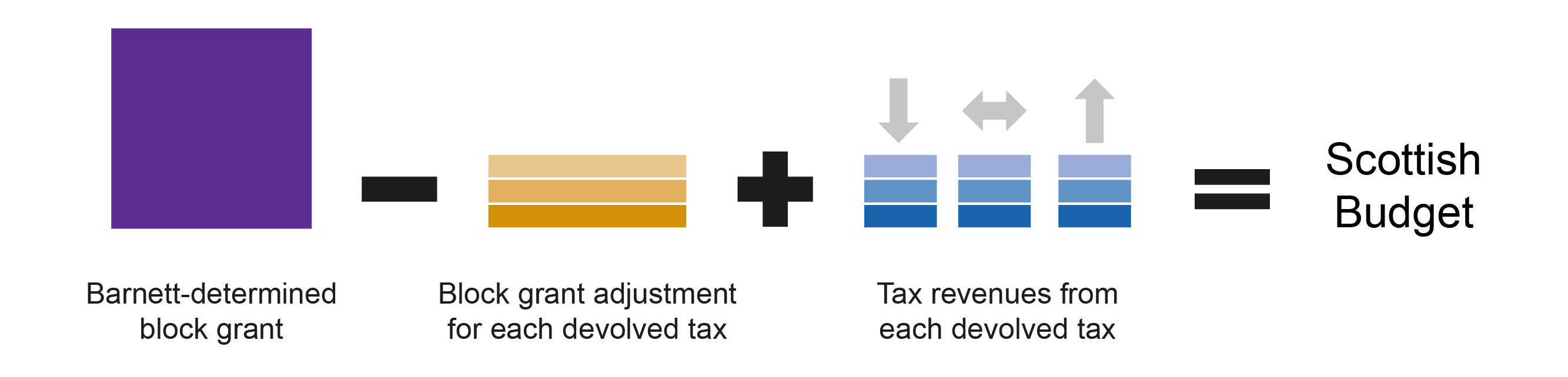

Under the terms of the Fiscal Framework 1agreed between the UK and Scottish Government to implement the Scotland Act 2016 powers, the size of the Scottish Budget is now determined by three elements (see figure 1).

The block grant allocation from the UK Budget - changes in this block are determined by increases or decreases in English spending on functions that are ‘comparable’ to those devolved to the Scottish Parliament.

A block grant adjustment (BGA), which is essentially a forecast of the revenue the UK Government has foregone by devolving taxes to the Scottish Parliament.

A Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) produced forecast for the revenue raised from taxes devolved or transferred to the Scottish Government.

These three elements plus the capital borrowing powers devolved by Scotland Act 2016, comprise the spending power of the Scottish budget.

Table 1.02 of the Draft Budget document presents the Scottish budget through to financial year 2019-20 in cash terms. This shows the budget will grow in cash terms by 2.5% in 2018-19 (1.0% in real terms) and 1.8% in 2019-20 (0.4% in real terms). Within this, Fiscal Resource spending, for day-to-day expenditure, will grow by 0.7% in 2018-19 and by 0.2% in 2019-20. In real terms (2017-18 prices), Fiscal Resource spending will fall by 0.8% in 2018-19 and fall by 1.2% in 2019-20.

On the Capital side, growth in 2018-19 including financial transactions and the Capital borrowing powers devolved by Scotland Act 2016, which the Scottish Government state that they intend to use in full, will be 7.1% in 2018-19 and 7.9% in 2019-20. Adjusted for inflation, Capital spending will increase by 5.6% in 2018-19 and 6.4% in 2019-20.

As is discussed in Box 1 below, for a number of reasons the figures in table 1.02 of the Draft Budget differ to the totals actually allocated amongst portfolios in the document -- annex A of the Draft Budget provides a reconciliation. The next section of the briefing looks at the total allocations for Resource, Capital and annually managed expenditure (AME) and how these are distributed amongst portfolios.

Although the Scottish budget is known through to 2019-20 for Resource and 2020-21 for Capital, this document only allocates these monies for one financial year, 2018-19. This will be the fourth Draft budget in a row that has allocated monies for a single year.

As mentioned, the Scottish Government intend to "make use of the full £450m available in 2018-19" for capital borrowing. This will need to be repaid in subsequent years, and the Draft Budget states on p35 that the borrowing will be drawn from the National Loans Fund with an assumption of repayment over 10 years, an interest rate of 2 per cent, repaid from 2019-20.

Many of the numbers in this briefing are adjusted for inflation (presented in 'real terms'/ 2017-18 prices) and the deflator used is the Treasury deflator2, as used in the Draft Budget, which is 1.48% in 2018-19.

Box 1: The reconciliation of available funding with spending plans

The numbers presented in table 1.02 differ to the total amounts allocated by the Scottish Government in the Draft Budget document. Annex A (pp183-185) provides a helpful reconciliation of the available funding (table 1.02) to the proposed spending plans. There are a number of reasons for the differences which are summarised below:

The 2017-18 baseline numbers in the spending plans reflect the plans as at Budget Bill 2017-18 for that year to show a like-for-like comparison against 2018-19 plans.

As such, the budget figures in table 1.02 include additional Barnett consequentials for 2016-17 and 2017-18 from UK fiscal events since the relevant Budget Bill, whereas the spending plans do not.

2017-18 and 2018-19 spending plans are underpinned by anticipated underspends carried from the previous year.

Machinary of Government changes, which relate to the transfer of responsibility from the UK to Scottish Government are not reflected in table 1.02, but are included in the portfolio spending plans.

There are some anticipated budget transfers for Scotland Act 2016 implementation and administration, that are not reflected in table 1.02 but are included in the spending plans in anticipation of being formally confirmed at a future UK fiscal event.

Non-Cash allocations are often more than required, and therefore not allocated to portfolios in spending plans and subsequently returned to HM Treasury.

Additional dwelling supplement (ADS) revenues are not included in 2016-17 spending plans because the legislation was not enacted at the time of the Budget Bill 2016-17 passage.

£29m was raised from freezing the Higher Rate tax threshold in 2017-18 at stage 2 of the Budget Bill. This is included in 2017-18 spending plans, but not in table 1.02.

In 2018-19, £50m in accumulated revenues for the Queen's and Lord Treasurer's Remembrancer is shown in the spending plans but not table 1.02.

| SG Spending Limits — Cash Terms | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scottish Government Funding (from Table 1.02) | 30,661 | 31,869 | 32,679 |

| Barnett Consequentials | 12 | -412 | |

| Budget Exchange/Reserve | -11 | 203 | 158 |

| Machinery of Government Changes | 31 | -1 | |

| Anticipated budget transfers | 15 | 156 | 159 |

| Unallocated Non-cash budget | -209 | -229 | -196 |

| Changes to LBTT | -24 | ||

| Changes to Income Tax | 29 | ||

| Queen’s and Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer | 50 | ||

| Total Reconciling Items | -217 | -222 | 172 |

| Scottish Government Spending Plans (from Table 1.05) | 30,444 | 31,647 | 32,849 |

Budget allocations

Total allocations

Total Managed Expenditure (TME) comprises Fiscal Resource, non-cash Resource, Capital and Annually Managed Expenditure (AME). TME in 2018-19 is £40,639m. Figure 2 shows how this is allocated. Fiscal Resource (which covers day-to-day expenditure) and Capital (covering infrastructure spending) are the the elements of the budget over which the Scottish Government has discretion. AME is expenditure which is difficult to predict precisely, but where there is a commitment to spend or pay a charge, for example, pensions. Pensions in AME are fully funded by HM Treasury, so do not impact on the Scottish Government's spending power. Non-domestic rates are also classed as an AME item in the budget and form part of Local Government spending.

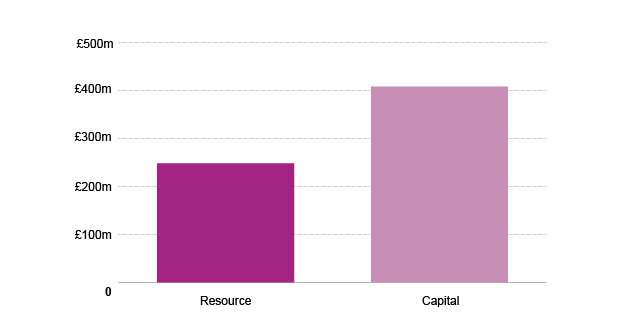

Figure 3 shows the real terms changes in Resource and Capital between 2017-18 and 2018-19. The Capital numbers include Financial Transactions and the £450m in proposed borrowing in 2018-19.

Portfolio allocations

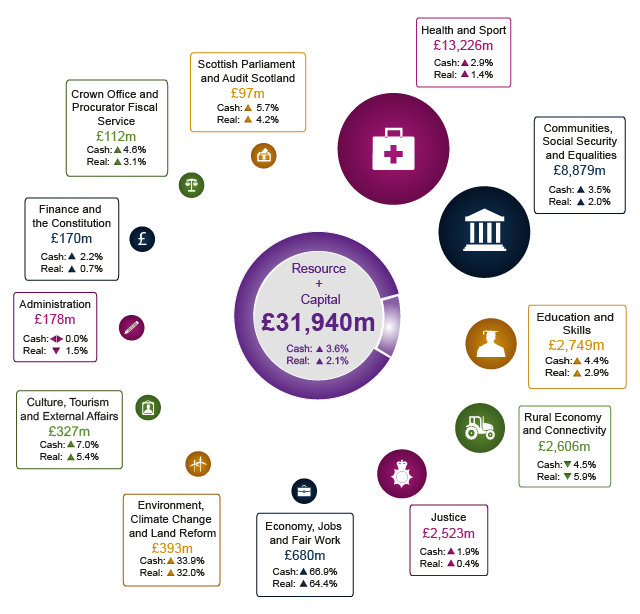

Resource and Capital allocations to portfolios for 2018-19, and how they have changed on the previous year, are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4 shows the Resource and Capital spending by portfolio and their cash and real terms changes in 2018-19. Key points to note are as follows:

Health and Sport is the largest portfolio, comprising 41.4% of the discretionary spending power (Resource + Capital) of the Scottish budget in 2018-19. This is a decrease on Health and Sport's share of the 2017-18 budget, which is 41.7%.

The next largest portfolio is Communities, Social Security and Equalities, which comprises 27.8% of the Resource and Capital spend combined. This portfolio includes Local Government, which is the subject of another SPICe briefing.

The Economy, Jobs and Fair Work portfolio has the largest percentage increase of any portfolio, and will grow by over 64% in real terms in 2018-19. This is largely driven by a steep rise in in Financial transactions being allocated to the portfolio in 2018-19.

The only portfolios that are decreasing in real terms are Rural Economy and Connectivity, which falls by 5.9% and Administration which falls by 1.5%.

Resource and Capital expenditure

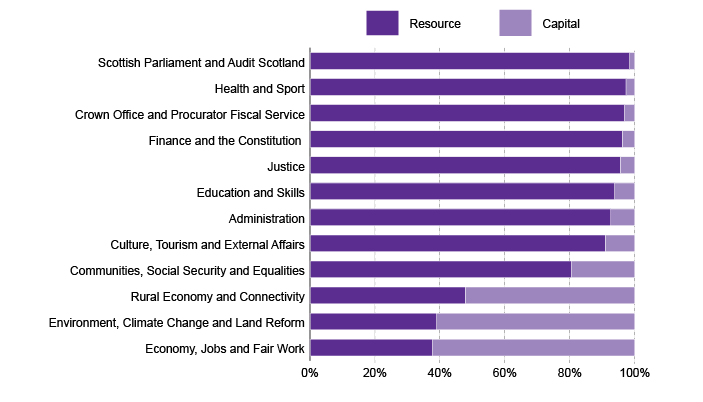

Figure 5 below shows the split between Resource and Capital by portfolios. This shows that most portfolios are heavily weighted towards funding day-to-day spending commitments.

The Economy, Jobs and Fair Work portfolio has the highest proportion of its budget comprising Capital expenditure (over 60%). This is a reversal of its position in Draft Budget 2017-18, where just 36% of its spend was on Capital. This change and the large real terms increase in its overall portfolio spending power is driven by city deal capital funding and financial transaction spend. The two other portfolios with over half of their spend coming from Capital investment are Rural Economy and Connectivity and Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform.

Taxation policies and revenue

Income tax

Draft Budget 2018-19 sets out the Scottish Government's proposed rates and bands for income tax. They propose five bands in total, including two new bands: the creation of a new "starter" band set at 19% and an intermediate band of 21%. The full rates and bands are presented in the table below. The SFC forecast that these policy proposals will raise an additional £164m in 2018-19 relative to the 2017-18 policy.

| Proposed band | Band name | Proposed rate |

|---|---|---|

| Over £11,850 - £13,850 | Starter | 19% |

| Over £13,850 - £24,000 | Basic | 20% |

| Over £24,000 - £44,273 | Intermediate | 21% |

| Over £44,273 - £150,000 | Higher | 41% |

| Above £150,000 | Top | 46% |

Overall, the SFC is forecasting revenues from non-savings non-dividend income tax of £12,115m in 2018-19.

Further information on the income tax proposals of the Scottish Government can be found in the SPICe briefing Draft Budget 2018-19: Taxes.

Devolved taxes

Land and Buildings Transaction tax and and Scottish Landfill tax have been devolved to the Scottish Parliament since April 2015. The Draft Budget proposes no changes to the existing rates and bands of LBTT in 2018-19.

| Residential transactions | Non-residential transactions | Non-residential leases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band | Rate | Band | Rate | Band | Rate |

| Up to £145,000 | Nil | Up to £150,000 | 0 | Up to £150,000 | 0 |

| £145,001 to £250,000 | 2% | £150,001 to £350,000 | 3% | Over £150,000 | 1% |

| £250,001 to £325,000 | 5% | Over £350,000 | 4.50% | ||

| £325,001 to £750,000 | 10% | ||||

| Over £750,000 | 12% | ||||

The Scottish Government also proposes retaining the Additional Dwelling Supplement (ADS) in 2018-19 which is set at 3 per cent of the total price of the property for all relevant transactions above £40,000.

In addition, subject to a consultation, the Scottish Government proposes introducing a new LBTT relief for first-time buyers of properties up to a value of £175,000.

The SFC forecast that in total LBTT will generate revenues of £588m in 2018-19.

Table 5 sets out the Scottish Government's proposed rates and bands for Scotish Landfill tax which will apply from April 2018 and compares them with the previous year.

| 2017-18 | 2018-19 | % increase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard rate | £86.10 | £88.95 | 3.3% |

| Lower rate | £2.70 | £2.80 | 3.7% |

These rates are the same as the planned UK Landfill tax rates for 2018-19. The Draft Budget states that Scottish rates are set with issues around 'waste tourism' in mind -- namely the potential for waste moving across the Scotland/England border should one country have a lower tax charge than the other.

The SFC forecast that Scottish Landfill tax will generate £106m in revenues in 2018-19.

Further information on the devolved tax proposals of the Scottish Government (including coverage of non-domestic rates) can be found in the SPICe briefing Draft Budget 2018-19: Taxes.

Block grant adjustment (BGA)

Changes to the Scottish Government's block grant will still be determined by the Barnett formula, which reflects changes to UK spending areas that are devolved to the Scottish Parliament.

The block grant is then adjusted to reflect the retention of some tax revenues in Scotland, and in future will be adjusted to account for the devolution of new social security powers.

The initial BGA is equal to the UK Governments tax receipts generated in Scotland in the year immediately prior to devolution. Baseline adjustments for LBTT and SLfT are already based on outturn figures. However, outturn data for NSND income tax in 2016-17 (the year prior to devolution) is still not available. As such, the initial BGA will be based on forecasts until outturn data is available.

The OBR is responsible for producing forecasts which inform HM Treasury's calculation of the BGA. However, for the 2018-19 Scottish Government budget, the Scottish Government and HM Treasury have agreed to use the SFC's 2016-17 forecast (rather than the OBR) for the baseline adjustment that informs the 2018-19 BGA. Draft Budget 2018-19 states:

This is a consequence of different methodological approaches taken by the SFC and the OBR which, without this change in approach, would have meant that the 2016-17 baseline adjustment was not fiscally neutral as anticipated in the Fiscal Framework.

An indexation mechanism is then applied to each initial adjustment. The planned adjustments are shown in table 6.

| BGA (Indexed per capita) | SFC forecast | Difference between SFC forecast and BGA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income tax (NSND) | 11,749 | 12,115 | 366 |

| LBTT | 600 | 588 | -12 |

| SLfT | 94 | 106 | 12 |

| Total | 12,443 | 12,809 | 366 |

The differences between the BGA and the SFC's forecasts will reflect

different tax policies set by the Scottish and UK Governments

different economic conditions

different forecast methodologies used by the SFC and the OBR.

Under the terms of the Fiscal Framework agreement, the block grant adjustment will be indexed using the Comparable Model (CM) and the results will then be adjusted to “achieve the outcome delivered by Indexed Per Capita (IPC)”. Each year, block grant adjustments will be produced based on both these mechanisms. Table 7 sets out the block grant adjustments that would be implied by the two methodologies. As shown in the table, use of the IPC methodology results in a smaller block grant adjustment than would be the case under the CM methodology. The gap increases over time so that, by 2021-22, the block grant adjustment is expected to be £165m lower than would be the case if the CM methodology had been adopted.

| 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPC | 12,443 | 12,764 | 13,206 | 13,693 |

| CM | 12,509 | 12,862 | 13,336 | 13,858 |

| Difference | -66 | -98 | -130 | -165 |

The forecasts for both Scottish tax revenues and the BGA are produced based on the latest available information at the time of the Draft Budget. Once outturn data is available for the Scottish tax revenues, a reconciliation will be carried out as per the timetable set out in the Fiscal Framework. For Scottish income tax, outturn data is likely to be available 15 months after the end of the financial year and for LBTT and SLfT this is likely to be available six months after the end of the financial year.

Capital and infrastructure

The 2018-19 capital allocations total £4,446.1m. This includes an assumed full utilisation of £450m borrowing powers and £489m financial transactions money. This is a 10.3% real terms increase on the equivalent capital budget for 2017-18.

Non-profit distributing (NPD) and hub programme

In recent years, the Scottish Government has used revenue financing to increase the level of infrastructure investment that could be achieved through the capital budget alone. Revenue financing means that the Scottish Government does not pay the upfront construction costs, but is committed to making annual repayments to the contractor, typically over the course of 25-30 years. The main forms of revenue financing are NPD, revenue-hub and Regulatory Asset Base (RAB) funding which is used for rail infrastructure.

In 2018-19, the Scottish Government plans to progress a number of existing projects using NPD financing. Current NPD projects are the Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route, the Edinburgh Royal Hospital for Sick Children and the Balfour Hospital, Orkney. The budget does not state the value of investment in these projects in 2018-19. No new NPD projects are currently being considered. The hub programme is being used to progress a range of schools and community health projects using revenue financing.

As a result of new European accounting guidance (European System of Accounts 2010 – ESA10), the budgeting treatment of NPD projects has changed. NPD projects are now deemed to be public sector projects and require upfront budget cover to be provided from the capital budget over the construction period of the asset. This compares with the budget treatment for private sector projects, where the costs are treated as revenue costs and are spread over the period (usually 25-30 years) over which the asset is used and maintained. The change in treatment means that NPD projects impact on the capital budget, thereby limiting the capital funds available for other projects. It is unclear how much of the capital budget is accounted for by NPD projects.

The Scottish Government has been able to adjust the design of smaller revenue-hub projects so that they can continue to be treated as private sector assets and financed through the revenue budget as before.

Revenue financing and the 5% cap

Annual repayments resulting from revenue financed projects, such as NPD and hub (revenue) projects, come from the Scottish Government’s revenue budget. The Scottish Government has committed to spending no more than 5% of its total budget on repayments resulting from revenue financing (which includes NPD/hub, previous PPP contracts, RAB rail investment) and any repayments resulting from borrowing. Based on current plans, the Scottish Government estimates that it will spend around 3.9% of its total budget on such payments in 2018-19, rising to a peak of just under 4.3% in 2020-21. The Draft Budget does not contain details of the anticipated revenue financing costs of infrastructure projects in 2018-19.

Borrowing powers

The Scottish Government is able to borrow up to £450m in 2018-19 for capital investment. The Draft Budget states that:

In order to maximise our commitment to investing in infrastructure, we will make use of the full £450 million available in 2018-19.

The Draft Budget also notes that:

Final decisions on borrowing arrangements will be taken over the course of the year reflecting an ongoing assessment of programme requirements.

As at December 2017, borrowing powers had not been used to increase capital investment, although in earlier years they have been used to provide budget cover for the NPD projects transferred to the public sector.

Financial Transactions

The Draft Budget includes £489m in 2018-19 for “financial transactions”. This relates to Barnett consequentials resulting from a range of UK Government equity/loan finance schemes (primarily the UK housing scheme, Help to Buy). Over the period 2012-13 to 2020-21, on the basis of current plans, financial transactions allocations will total £2.5bn. The Scottish Government has to use these funds to support equity/loan schemes beyond the public sector, but has some discretion in the exact parameters of those schemes and the areas in which they will be offered. This means that the Scottish Government is not obliged to restrict these schemes to housing-related measures and is able to provide a different mix of equity/loan finance.

In 2018-19, a total of £221.3m has been allocated to housing-related schemes, including Help to Buy (Scotland) and the Open Market Shared Equity (OMSE) Scheme. The Scottish Government is also providing equity/loan finance support in areas other than housing. For example, £80m of FT funding is being provided to support the Building Scotland Fund aimed at boosting housebuilding, commercial property and research and development

The budget document shows a profile for FTs by portfolio area, as set out in Table 8. The £528m total in this table exceeds the £489m total given in Table 1.02 of the Draft Budget document because £39m of FT allocations have been carried forward from the previous year.

| £m | |

|---|---|

| Health and Sport | 10.0 |

| Education and skills | 40.0 |

| Economy, Jobs and Fair Work | 180.0 |

| Communities, Social Security and Equalities | 256.3 |

| Rural Economy and Connectivity | 37.0 |

| Culture, Tourism and External Affairs | 4.8 |

| Total | 528.1 |

The Scottish Government will be required to make repayments to HM Treasury in respect of these financial transactions. Repayments will be spread over 30 years, reflecting the fact that the majority of FT allocations relate to long term lending to support house purchases and the construction sector. The repayment schedule is agreed with HM Treasury and is based on the anticipated profile of Scottish Government receipts. The first repayment to HM Treasury is scheduled for 2019-20.

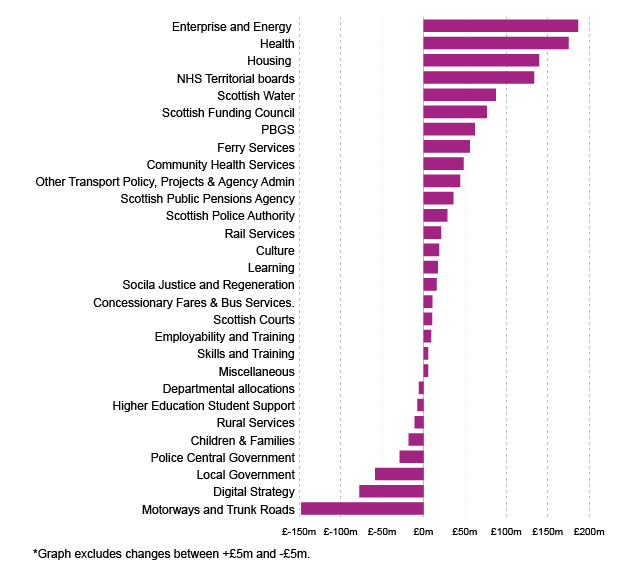

Real terms increases and decreases

Figure 6 presents the largest real terms level 2 budget line increases and decreases in 2018-19 on the previous year.

Local Government

This section of the briefing sets out a high level summary and analysis of the local government budget for 2018-19. A dedicated detailed briefing on the local government budget, and the settlement for local authorities, is also available on the SPICE Briefings hub.

The last two fiscal years (2016-17 and 2017-18) have been characterised by reductions in the core grant to local authorities, together with a number of changes to the way in which the total amount of resources available to local authorities has been presented.

In response to the issues raised in during the 2017-18 budget process, and by the Budget Process Review Group, the Scottish Government has made a number of changes to the way in which the local government information is presented in the budget documents and the local government finance circular. This means that the different figures are now much easier to follow.

The total allocation to local government in the 2018-19 Draft Budget is £10,384.1m. This is mostly made up of General Revenue Grant (GRG) and Non-Domestic Rates Income (NDRI), with smaller amounts for General Capital Grant and Specific (or ring-fenced) Revenue and Capital grants.

Once Revenue funding in other portfolios is included (as set out in the local government finance circular), the "Total Core Local Government Settlement" is £10,507.1m. And, if all funding outwith the local government finance settlement (but still from the Scottish Government to local authorities) is included, the total is £10,868.1m. Finally, if "other sources of support" are included the total rises to £11,334.1. In the remainder of this briefing, which focuses on the year on year change figures, we concentrate on the numbers within the central local government budget - that is, the breakdown of the £10,384.1m figure in Table 10.13 of the Draft Budget. The dedicated local government briefing contains further analysis of the local government finance circular. Table 9 below sets out the local government budget breakdown in the Draft Budget.

Table 9: Local Government budget - compared to 2017-18 Draft Budget, as amended

| Local Government | 2017-18 | 2018-19 (cash) | Cash change | Cash change % | 2018-19 (real) | Real change | Real change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Revenue Grant | 6,627.8 | 6,608.5 | -19.3 | -0.3% | 6,512.3 | -115.5 | -1.7% |

| Non-Domestic Rates | 2,665.8 | 2,636.0 | -29.8 | -1.1% | 2,597.6 | -68.2 | -2.6% |

| Support for Capital | 653.1 | 598.4 | -54.7 | -8.4% | 589.7 | -63.4 | -9.7% |

| Specific Resource Grants | 210.9 | 263.2 | 52.3 | 24.8% | 259.4 | 48.5 | 23.0% |

| Specific Capital Grants | 133.4 | 278.0 | 144.6 | 108.4% | 274.0 | 140.6 | 105.4% |

| Total Level 2 | 10,291.0 | 10,384.1 | 93.1 | 0.9% | 10,232.9 | -58.1 | -0.6% |

| GRG+NDRI | 9,293.6 | 9,244.5 | -49.1 | -0.5% | 9,109.9 | -183.7 | -2.0% |

| GRG, NDRI and SRG | 9,504.5 | 9,507.7 | 3.2 | 0.0% | 9,369.3 | -135.2 | -1.4% |

| Total Capital | 786.5 | 876.4 | 89.9 | 11.4% | 863.6 | 77.1 | 9.8% |

The Scottish Government guarantees the combined GRG and distributable NDRI figure, approved by Parliament, to each local authority. If NDRI is lower than forecast, this is compensated for by an increase in GRG and vice versa. Therefore, to calculate Local Government's Revenue settlement, the combined GRG + NDRI figure is used. As in previous years, a number of different interpretations can be put on the figures.

The Draft Budget numbers show General Revenue Grant plus Non Domestic Rates Income falling by 0.5% (-£49.1m) in cash terms, or 2% (-£183.7m) in real terms between 2017-18 and 2018-19.

When Specific Revenue Grants are taken into account, there is a small cash increase in Total Revenue funding for 2018-19 (+£3.2m). In real terms, this results in a reduction of 1.4% (-£135.2m).

Total Capital funding, by comparison, increases by 11.4% (£89.9m) in cash terms, or 9.8% (£77.1m) in real terms, although this increase is due to an increase in specific grants - general support for capital is decreasing in cash and real terms.

Local authorities must agree to a number of commitments to access the full funding package, including maintaining teacher numbers, securing places for all probationers under the teacher induction scheme and expansion of childcare.

Pay policy is discussed elsewhere in this briefing. SPICe notes that pay is delegated to local authorities and so the Government's pay policy does not apply to council employees. However, SPICe has estimated that, if local authorities were to match the Scottish Government's pay policy, this would cost around £150m in 2018-19.

These are total costs and do not reflect the costs that would have been incurred in awarding a 1% increase. When compared with the costs of implementing a 1% pay award, the additional costs are around £90m i.e. the new pay policy would cost £90m over and above the costs of a 1% pay settlement. These estimates relate only to the costs of the pay policy and take no account of any additional costs relating to pay progression (whereby staff progress through set pay bands on an annual basis, regardless of the basic pay settlement). They also assume no change in the mix of staff and take no account of adjustments that employers might make in order to maintain pay differentials between staff.

As noted above, the funding available to local authorities for core services (GRG + NDRI) is due to fall by £49.1m in cash terms, and "total Revenue" funding is increasing by £3.2m. Therefore, councils may face challenges in matching this pay policy commitment.

This issue, and other detail around the local government settlement, is discussed in detail in the dedicated local government briefing.

Transparency of the budget

In June 2017, the Budget Review Group (BRG) published its final report1 containing a range of recommendations for how the budget process might be improved. Most of these recommendations are for a revised process which will be agreed by Parliament in the new year - and will be the subject of a future SPICe briefing. As such, they will not be in place for the 2018-19 budget process.

However, recommendation 44 of the BRG report, contained a range of recommendations that the Scottish Government should consider prior to Scottish Budget 2018-19, "in order to improve the accessibility and transparency of the Budget". The Scottish Government agreed to all recommendations in the report.

Recommendation 44 states that:

The factual content of budget proposals is separated from any political narrative.

There should be a consistent approach to the presentation of financial data within the budget document. This financial information should be available to Level 3.

Budget aggregates should be comparable year on year including reflecting the impact of changes to Ministerial portfolios.

The budget document should include historical analysis of financial information by portfolio as well as against key budget aggregates (including capital and revenue allocations).

In addition, there needs to be clarity regarding the relationship between budget allocations and available funding in different parts of the budget document. Spending allocations across all portfolios within the budget document must be reconciled with available funding.

All aspects of Scottish Government expenditure should be separately identified within the document on a consistent basis. Where allocations to individual organisations are derived from different budget portfolios this needs to be set out consistently and transparently.

There should be consistency in the period covered by the Budget which should also be retrospective covering at least two prior years as well as forward looking.

Clear financial information on the operation of Scotland Act 2012 and 2016 powers.

The provision of Level 4 financial information to be published alongside the publication of formal budgetary information in the same manner as is currently the case.

The Financial Scrutiny Unit considers that the Scottish Government has been effective at delivering on this recommendation in the budget documentation. However, in terms of forward looking presentation, it would be beneficial to have more than single year allocations.

How might the budget change?

As mentioned above, publication of the Draft Budget commences a parliamentary scrutiny process and political negotiation, as the Scottish Government seeks a parliamentary majority for 2018-19 tax and spending. So how might the budget change prior to final parliamentary votes on tax and spending proposals?

Last year's initial Draft Budget 2017-181 was amended during the Budget Bill's passage through Parliament when an additional £220m funding was allocated. This was funded by:

£125m in underspends from 2016-17 carried into 2017-18.

£60m from the non-domestic rates pool.

£29m from revenue raised by lowering the higher rate income tax threshold relative to the initial draft budget proposal.

£6m from lower than expected borrowing costs.

It is possible that some combination of additional resource may be necessary to achieve the support of a majority of MSPs for the 2018-19 Budget Bill's passage.

On tax, the Scottish Government has proposed increasing income tax revenues relative to current Scottish Government policies by £164m. However, they may need to go further or reverse these to gain the support of another political party. Labour, the Green and Liberal Democrats wish to see additional revenues generated from income tax, and the Scottish Conservatives wish to see income tax rates and bands aligned with the rest of the UK.

On underspends, the Scottish Government usually has between £100m-£200m of underspends in any given year. Alongside new tax powers, the Scottish Government now has the option to place any underspends or tax surpluses in a Scotland Reserve. The Cabinet Secretary now has a choice of whether to allocate these in the 2018-19 budget (as he did previously prior to the creation of the Reserve) or place them in reserve to smooth any subsequent shortfalls in tax receipts relative to forecast. Table 1 in the Annex implies that £185m in underspends have already been built into Draft Budget 2018-19 spending plans, so scope for amending Budget Bill 2018-19 from 2017-18 underspends would appear limited.

Use of the NDR pool to add to next year's spending power may be challenging. A recent Audit Scotland report2 showed that at the end of financial year 2016-17, the NDR account showed a deficit balance of £297m. This means that the Scottish Government has redistributed more to councils in recent years than councils have collected in receipts. The Scottish Government has signalled an intention to bring the NDR account back into balance over a number of years, although the Audit Scotland report stated that 'there is no formal plan in place' to do so. Audit Scotland stated that:

The Scottish Government needs to develop and maintain a strategic plan of future non-domestic rates distribution levels as part of its commitment to longer-term financial planning. This should include the impact of addressing the deficit balance on its overall financial position.

Table 10.17 of the Draft Budget lays out how the Scottish Government plan to bring the NDR account back into balance by the end of 2018-19.

The SFC forecast £2,810m will be collected by Local Authorities in 2017-18, while the Scottish Government set the distributable amount at £2,666m for this year. This implies that there is potential for the NDR account deficit to be reduced in the current financial year from the £297m at the end of 2016-17 to £153m at the end of 2017-18 (SFC, pp114-115).

Using the NDR pool to amend the Budget Bill may well still be an option for the Cabinet Secretary. However, given the Scottish Government's intention of bringing the NDR account back into balance, and the likelihood of the NDR account remaining in deficit at the close of this financial year, room for manoeuvre in this area may be limited.

Other issues

The Scottish Government published a range of documents alongside Draft Budget 2018-19 and some of the key points from these are summarised below.

Public sector pay

The Scottish Government published its Public Sector Pay Policy for 2018-19 alongside the Draft Budget.1 The Scottish Government 2018-19 pay policy lifts the 1% pay cap that has been in place since 2013-14 (which itself followed a pay freeze in 2011-12 and 2012-13).

The main features of the 2018-19 pay policy are:

a minimum 3 per cent increase for public sector workers who earn £30,000 or less

a limit of 2 per cent on the increase in baseline paybill for those earning above £30,000 and below £80,000

a limit of £1,600 on the pay increase for those earning £80,000 or more

a continuation of the requirement for employers to pay staff the real Living Wage (currently £8.75 per hour)

flexibility for employers to use up to 1 per cent of paybill savings on baseline salaries for limited non-consolidated payments to certain employees or to address equality issues.

The pay policy retains the features of previous pay policies in relation to:

discretion for employers in relation to pay progression

the suspension of non-consolidated performance related pay (bonuses)

the commitment to no compulsory redundancies

the expectation that there will be a 10% reduction in remuneration packages for new Chief Executive appointments.

The pay policy does not apply directly to all public sector staff. It only directly affects the pay of Scottish Government staff, and the staff of 44 public bodies, which together account for around 9% of the Scottish public sector (around 37,000 staff). Large parts of the public sector, such as local government and the NHS are not directly covered by the Scottish Government’s pay policy and pay is determined separately for these groups, although often in line with the Scottish Government's pay policy and - in some cases - with some Ministerial control. The pay policy notes that:

This policy also acts as a benchmark for all major public sector workforce groups across Scotland including NHS Scotland, fire-fighters and police officers, teachers and further education workers. For local government employees, pay and other employment matters are delegated to local authorities.

The estimated costs of implementing the 2018-19 pay policy, compared with the cost of a 1% cap, is £20m for those groups directly affected by the Scottish Government's pay policy. Estimated costs for other groups are shown in Table 10. The Scottish Government has varying degrees of influence on the pay settlement and negotiations of NHS staff, police, firefighters, teachers and further education staff. For these groups, additional costs associated with the new pay policy are estimated to total £120m. The Scottish Government has no involvement in the pay negotiations of non-teacher local authority staff. For this group, the additional costs of implementing the same pay policy are estimated at £60m. If the pay policy was implemented across the whole Scottish public sector, then the additional costs over and above the cost of a 1% pay increase are estimated at £200m.

| Influence of Scottish Government pay policy | Estimated total costs£m | Estimated additional costs compared to 1% increase£m | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Scottish Government, NDPBs, Public Corporations, Departments and Agencies | Pay policy applies directly | 40 | 20 |

| NHS (Agenda for Change, Medical and Dental Staff and Senior Managers) | Pay award is aligned with public sector pay policy | 170 | 80 |

| Police Officers, Firefighters, Teachers and Further Education workers | Different levels of Ministerial control on matters relating to pay | 90 | 40 |

| Local government employees (except teachers) | Pay and other employment matters are delegated to local authorities | 100 | 60 |

| Total for all groups | 400 | 200 |

These estimates relate to the cost of the pay policy alone and do not take account of any additional costs that might result from progression payments (whereby staff progress through set pay bands irrespective of the pay settlement). In addition, the estimates assume no change in the mix of staff and do not reflect any adjustments that employers might make in order to maintain pay differentials between staff.

National Performance Framework

Since 2007, the Scottish Government has been operating an outcomes-based National Performance Framework (NPF)1. The Scotland Performs website reports on progress of government in Scotland, with indicators providing “a broad measure of national and societal wellbeing, incorporating a range of economic, social and environmental indicators and targets which are updated as soon as the data are available”.

To support scrutiny of the Draft Budget, the Government provides its annual Scotland Performs Update2, published alongside the Draft Budget document. This includes a Performance Scorecard section grouping together a selection of national purpose targets and national indicators under relevant Scottish Parliament subject committee headings.

Although this provides an interesting yearly snapshot, the Scorecard does not measure the extent to which spend within portfolio/committee areas has contributed to improved or declining performance. Neither does it give an overall assessment, or score, for each portfolio area compared to previous years. It is therefore impossible to say from the document whether Scottish Government spend has been more or less successful in helping the SG achieve its goals.

The Update does include narratives for each of the 16 National Outcomes3. These describe various case studies illustrating contributions made by various agencies and policies towards outcomes. For example, the Government describes in some detail how its £19 million spend on the recently established Work Able Scotland and Work First Scotland employment services has helped people with disabilities and long-term health problems back into the labour market. This spend has clearly contributed to the “We realise our full economic potential with more and better employment opportunities for our people” national outcome.

Earlier this year, the Budget Process Review Group published its Final Report4, which included a section on the National Performance Framework and its use in the budget process. Although the Group recognised that the Scorecards provided a basis for performance reporting, “they require further development”. Specifically, the group recommended:

…that the Scottish Government ensures that any new policies, strategies or plans clearly set out the outcomes they are aiming to achieve and the intermediate outputs, measures and milestones that will be used to monitor progress towards this. It should be clear how spending on the particular policy or activity will contribute towards improving specific national outcomes in the NPF, including cross-cutting issues such as equalities outcomes.

Equality Budget Statement

The Draft Budget has been accompanied by an Equality Budget Statement1 (EBS) for the last nine years. The aim of the EBS published by the Scottish Government is to assess the impact on equality of the various spending decisions made in the Draft Budget. This year’s document sets out the strategic context for equality from events of the year. It provides an overview of impacts by the equality protected characteristics established in the Equality Act 2010. It has a thematic chapter on inclusive growth. The remainder of the EBS document is taken up with a summary chapter for each Ministerial portfolio, e.g. Health and Sport; Education and Skills, allowing a more detailed exploration of issues.

The inclusive growth chapter emphasises a place based approach. This includes the creation of a Centre for Regional Inclusive Growth. The Centre will build on ongoing inclusive growth diagnostic which is currently being undertaken in a number of economic geographies and will be supported by the development of a monitoring framework. This will complement and sit as an aligned framework to the refreshed National Performance Framework, providing clear metrics for national, regional and local organisations to use to track progress.

The majority of budget measures identified in the EBS are “not anticipated to have negative impacts” on progressing equality. The document notes that a “negative assessment at an early stage in the policy or budget process will mean that particular proposals are not taken any further and do not appear in the Draft Budget. This is one of the, perhaps less recognised, benefits of equality processes within the Scottish Government”. However, there are some areas identified in the EBS where concerns are expressed or need for change is emphasised. Some examples are now highlighted.

A reduction in funding for Self-Directed Support could have a negative impact on the range of individuals using social care services, including disabled adults and children. However, the EBS document notes the revised figure is in line with actual transformation spending in 2017-18 and should not significantly constrain the support available or have negative equality impacts.

It states the impact of income tax policy is limited to those who are in receipt of a taxable income. In Scotland, there are almost two million adults with no income tax liabilities due to low or no income, which is over 40 per cent of the 16+ population.

It emphasises that public sector bodies need to deliver activities which promote equality. For example, any additional activity associated with Scottish Enterprise’s £51 million increase in budget will require equality impact assessment by Scottish Enterprise

It notes City Region Deals have the potential to have a significant impact on equality groups; however impact assessments have only been conducted for Aberdeen and Inverness deals. This is in part due to the fact that data on protected characteristics is limited at regional level. Still the need for improved equality assessments in this area is stressed.

The document also outlines the EBS response to the Scottish Parliament’s Budget Process Review Group, and concludes by stating the recommendations will take time to fully develop and “this is particularly true for the recommendations around equality assessment”.