How can we reduce obesity in Scotland?

This briefing was prepared by Kate Grant (University of Edinburgh) during an RCUK Policy Placement. The briefing looks at reducing obesity in Scotland, compares the policy recommendations made by several organisations and explores 25 policy areas in more detail.

Executive Summary

Most people in Scotland are overweight: 2 out of every 3 adults and 1 out of every 4 children. People with a healthy weight are now in the minority. Obesity trends are affected by age, gender and socio-economic status.

Obesity can have serious health consequences, such as cancer, type 2 diabetes, strokes and many other debilitating conditions. Overall, obesity can reduce average lifespan by up to 10 years.

In Scotland, obesity costs the NHS an estimated £600 million per year. It significantly reduces Scottish productivity and the size of the Scottish economy.

At a simple level, obesity may be seen as the result of an ‘energy imbalance’ where energy consumed (diet) exceeds energy expended (physical activity).

Diet in Scotland

Overall, the Scottish diet is less healthy than would be ideal. Compared to the Scottish Dietary Goals, people in Scotland eat and drink too many calories, too much sugar and fat. Conversely, Scots do not eat enough fruit, vegetables, fibre and oily fish.

Scottish consumption of “discretionary” food and drink — biscuits, cakes, pastries, confectionery and sugar sweetened drinks — is concerning. Food Standards Scotland recommends reducing the population-level consumption of these products by 50%.

Figures show that Scotland likes fast food, quick service bakeries and takeaways. The five most visited brands are McDonalds, Greggs, Tesco, Asda and Morrisons. Amongst the most popular purchases are chips, fries, cakes, biscuits, pastries and regular cola.

Physical activity in Scotland

In 2015, one third of adults did not meet the recommended levels of physical activity. People spend a good proportion of their free time being sedentary. On average, adults spend 5 – 6 hours being sedentary, depending on whether it is a weekday or a weekend. This excludes time spent at work. Similarly, children spend 3 – 4.5 hours being sedentary. This excludes time at school or nursery.

What causes obesity: more than just diet versus exercise?

Obesity does appear, however, to be more complex than a simple energy imbalance between diet and exercise. Research has shown that over 100 different variables affect obesity levels, including: biology, individual psychology, economics, jobs, urban planning, land use, education, culture, social customs, food production, trade, access to food, marketing and advertising.

To illustrate this, the most deprived spend twice as much of their income on food compared to the most affluent: 17% versus 8% of total income. Healthier food products are more expensive, according to some studies. In the UK (in 2012), 1,000 calories from unhealthy food products was estimated to cost £2.50, compared to £7.49 for healthy food products. Fruit and vegetables had the highest cost per 1,000 calories. Therefore, various economic factors might influence whether people buy healthier items.

A number of high profile publications — from academic experts to doctors — have argued that there is an "obesogenic environment" in many developed countries, including the UK. In other words, many aspects of modern living encourage obesity-promoting behaviours.

Obesity policy in Scotland

Policy to tackle obesity is a mixture of EU, UK and Scottish measures. At a Scottish level, the Obesity Route Map (2010) is the central policy statement. The Scottish Public Health Network reviewed the Route Map in 2015, suggesting it represented a reasonable response to the challenge but also identifying areas where further action is needed. A new strategy is currently being developed.

What policy interventions have been recommended?

What policy interventions should be used and how they should be applied, has been vigorously debated. Recurring themes emerge from this debate:

To what degree is obesity a personal responsibility or a societal responsibility?

What combination of treatment interventions and preventative interventions would be most effective?

In what cases should voluntary agreements with industry be used and when is government regulation more effective?

How can effective policy be developed with sometimes ‘imperfect’ knowledge?

Different policy options may be preferred, depending on the point of view taken in these four areas.

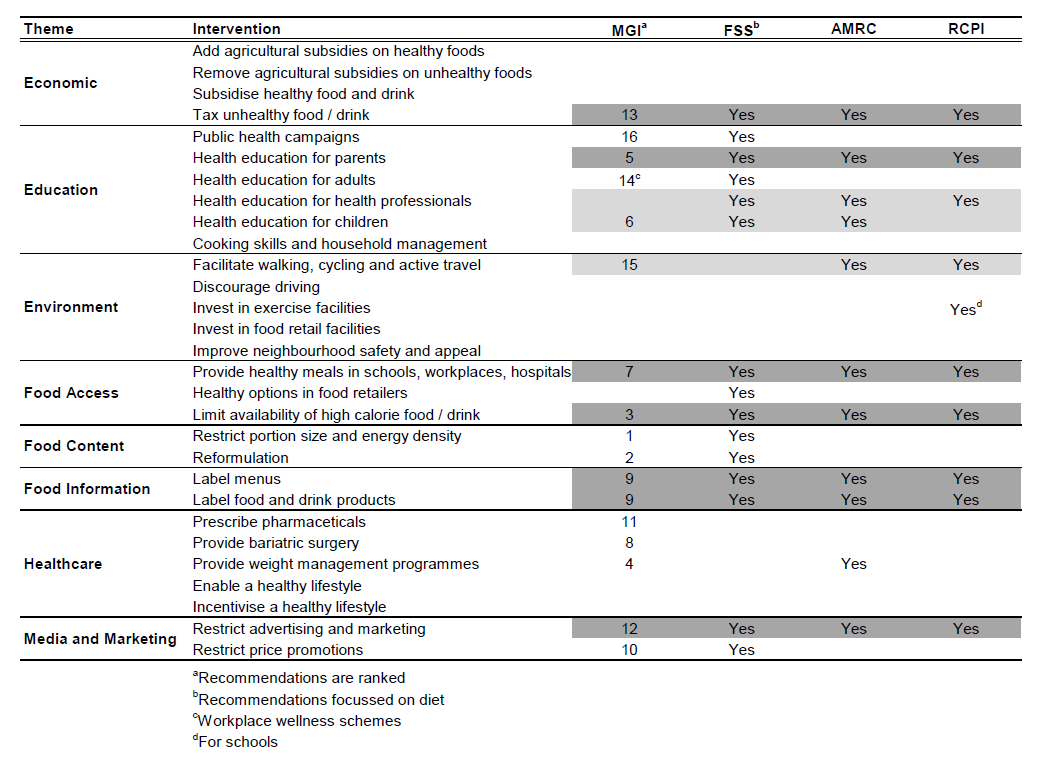

Several organisations have recommended policy interventions for reducing obesity in Scotland or the British Isles. This briefing reviews recommendations from four: McKinsey Global Institute (2014); Food Standards Scotland (2016); Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (2013); Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (2014).

Potential interventions areas, highlighted by three or more of these organisations, include:

Taxing unhealthy food and drink products

Restricting advertising and marketing of unhealthy food or drink

Change the built environment to facilitate active travel

Providing health education for parents and children

Providing healthy meals in schools, workplaces and hospitals

Limiting the availability of unhealthy food and drink

Better labelling of food, drink and meals

However, all organisations emphasise that there is no single ‘magic cure’ for obesity. They all advocate a broad, multi-component approach.

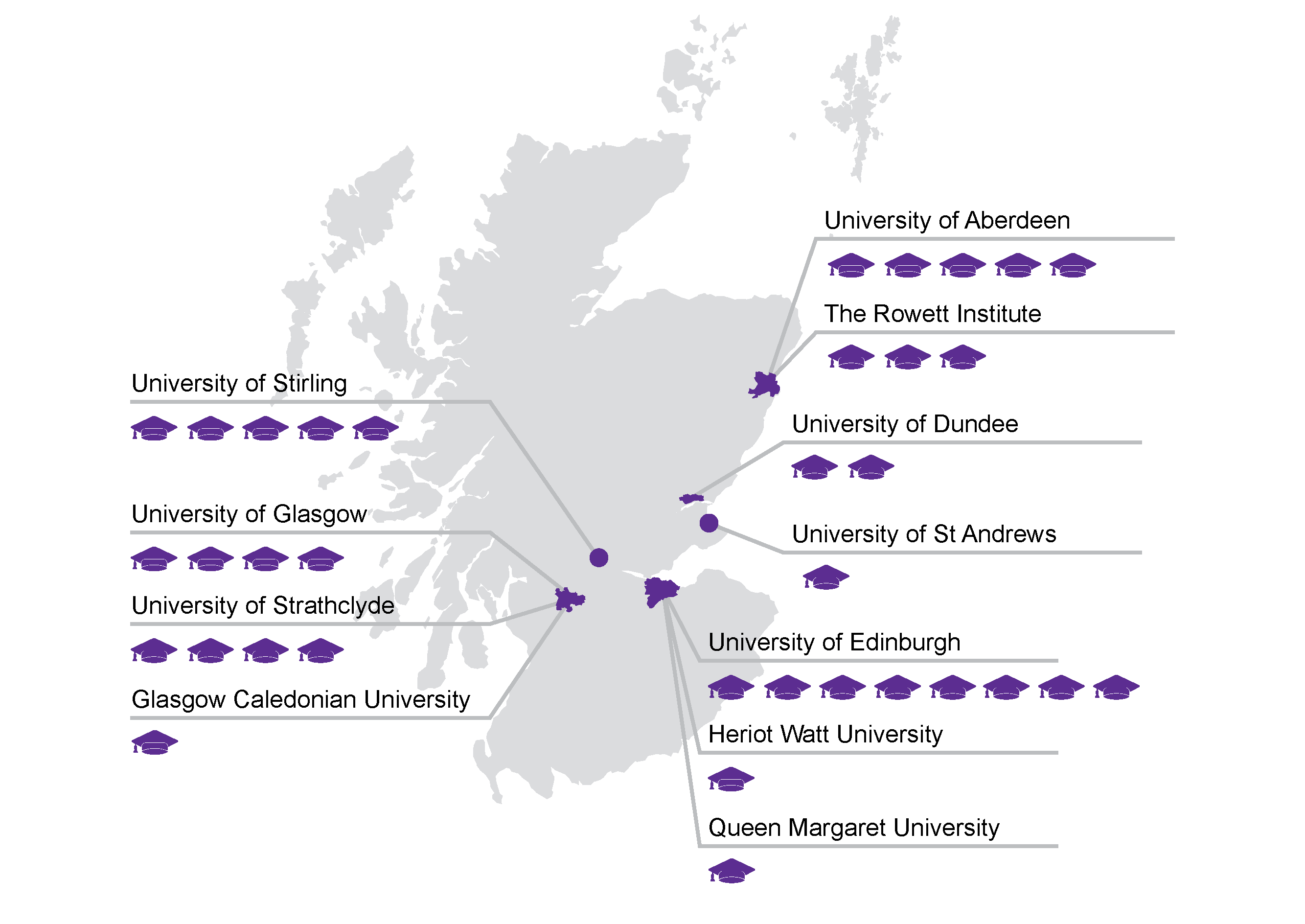

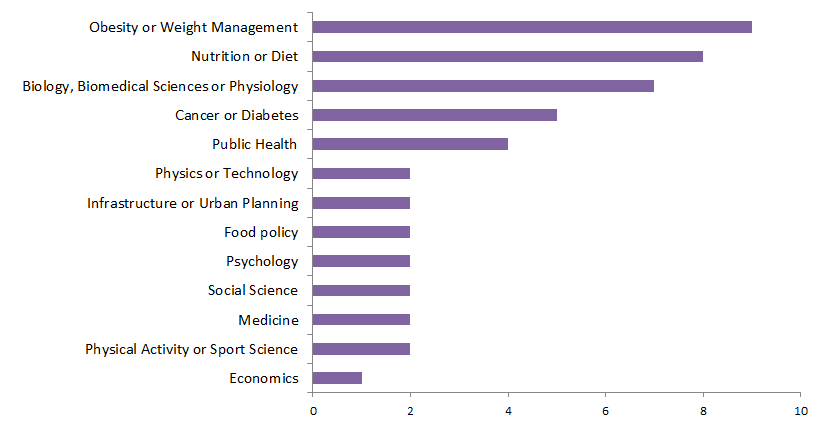

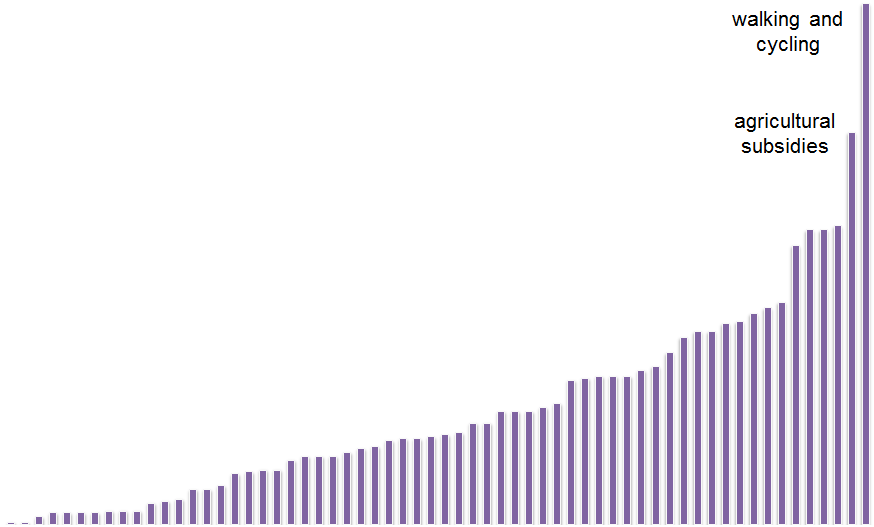

To support this briefing, SPICe conducted a survey of Scottish academics to ask them, in their opinion, what policy interventions would most reduce obesity in Scotland? The survey was carried in May and June 2017. The results should be interpreted with caution: they give a flavour of the respondents’ views and are not an assessment of the weight of evidence.

Amongst the most popular initiatives identified by academics were:

Encouraging walking, cycling and active travel

Reducing the relative price of healthy food through agricultural subsidies

Free or subsidised healthy school meals

Reformulation of food and drink products through government regulations

Providing health, diet and exercise education for children

However, the central finding is the wide spread of support for interventions. This reinforces the fact that there is no single ‘cure’ for obesity. Scottish academics support a broad range of policy interventions.

What are the potential policy interventions?

This briefing has distilled possible policy interventions into 25 areas (groups of related policy interventions). Possible policy interventions were derived from the comprehensive list of interventions presented in the McKinsey Global Institute (2014). A short summary is provided for each policy area.

The 25 policy areas are show in the table below.

| Theme | Intervention Areas |

|---|---|

| Economic | Taxing unhealthy food and drink |

| Subsidising healthy food and drink | |

| Removing agricultural subsidies from unhealthy food | |

| Adding agricultural subsidies to healthy food | |

| Education | Public health campaigns |

| Providing health education | |

| Providing household management education | |

| Environment | Facilitate walking and cycling |

| Discourage car usage | |

| Neighbourhood safety and appeal | |

| Exercise facilities | |

| Food facilities | |

| Food access and availability | Access to healthy meals |

| Layout and contents of retailers | |

| Food content | Reformulation |

| Energy and portion size | |

| Food information | Labelling food and drink products |

| Labelling menus | |

| Healthcare | Surgery and pharmaceuticals |

| Weight management programmes | |

| Enabling a healthy lifestyle | |

| Incentivising a healthy lifestyle | |

| Media and marketing | Advertising |

| Price promotions | |

| Other promotional activity |

Obesity in Scotland

What is obesity?

Obesity is a medical condition. It occurs when someone accumulates excess body fat to the point where their health may be negatively affected.1

In adults, obesity is diagnosed using two measurements: the Body Mass Index (BMI) and waist circumference. BMI is an approximate measure of total body fat. It is calculated from a person's weight and height. Waist circumference is used to assess distribution of body fat.1

Diagnosing obesity in children is more difficult because they are still growing. Age and gender-specific BMI ranges are used to identify children at risk of being overweight or obese.1

The table below shows how BMI measurements translate into different categories.

For the rest of this briefing, the term 'overweight' means having a BMI over 25. 'Obese' means having a BMI over 30.

| BMI (kg per m2) | Definition |

|---|---|

| Less than 18.5 | Underweight |

| 18.5 - 24.9 | Normal weight |

| 25 - 29.9 | Overweight |

| 30 - 34.9 | Obese (class I) |

| 35 - 39.9 | Obese (class II) |

| More than 40 | Obese (class III) |

Obesity statistics

Obesity in Scotland

Most people in Scotland are overweight: 2 out of every 3 adults and 1 out of every 4 children. People with a healthy weight are now in the minority.1

The statistics behind Scotland's obesity crisis are covered in more detail in a recent (2015) SPICe briefing.2

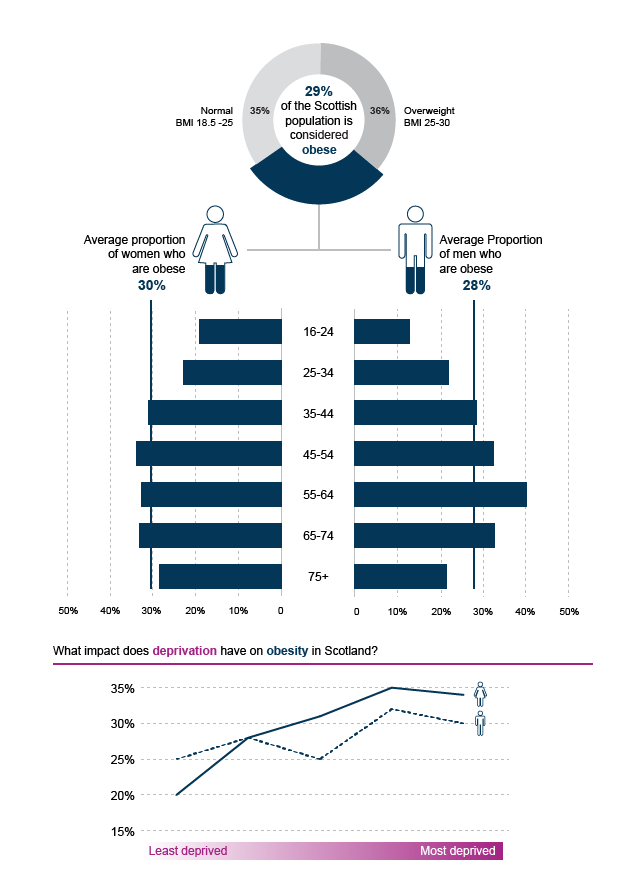

Briefly, the number of obese or overweight adults increased steadily between 1995 and 2008. Since then, the rate of increase has levelled off. In 2015, 65% of all adults were overweight or obese and 29% of all adults were obese.2

The number of children at risk of being overweight or obese has fluctuated since 1995. In 2015, 28% of children were at risk of being overweight and 15% were at risk of being obese.2

Effect of age, gender, region and socio-economic status

Being overweight is influenced by several factors: gender, age, region, income and education.2

Overall, men are more likely to be overweight, but women are more likely to be obese.

Young people are less likely to be overweight or obese. As people get older, overweight and obesity levels rise, with 55-74 years being the highest risk age group.1

In most developed countries, including Scotland, lower socio-economic status groups have a higher risk of obesity. There are several ways to measure socio-economic status: household income, area deprivation, occupation or educational achievement. But this 'inverse' relationship can usually be seen, regardless of the measurement used.1 8 9

Women from low socio-economic groups are often affected by obesity more acutely. In Scotland, 32% of women are obese in the most deprived areas, compared to 20% of women in the least deprived areas. For men, 30% obese in the most deprived areas, compared to 25% in the least deprived areas. 2 1 9

Finally, health board statistics show regional variations in obesity risk. Between 2008 and 2015, adult obesity was higher than the Scottish national average (29%) in:13

Fife (31%)

Lanarkshire (33%)

Shetland (33.2%)

Ayrshire & Arran (34%)

Orkney (36%)

Western Isles (36%)

Many of these regions have an older than average population.

How does Scotland compare with other countries?

England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales collect obesity statistics in different ways. This can make it difficult to compare between the countries. Nevertheless, the data suggests that Scotland has a slightly higher proportion of overweight and obese adults than the other UK countries.14 2 16

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) collects obesity statistics on its member countries. These are generally more developed countries. On average, 19.5% of adults in the OECD area are obese, compared with 26.9% of adults in the UK. This makes the UK the sixth most obese country out of the 35 OECD countries.16 If counted separately, Scotland would be the fifth most obese country in OECD area.

Finally, at a global scale, there are far more overweight people than malnourished people: 2,100 million people versus 840 million people respectively.8

Future trends

By 2030, the Scottish Government predicts that 40% of adults will be obese and many more overweight, even with current health improvement efforts. They also estimated (in 2010) that the direct cost to NHS Scotland would almost double.19

A Foresight project looked at possible obesity trends in the UK by 2050. Their model predicted that 90% of men and 85% of women could be overweight, whilst 60% of men and 50% of women could be obese.20

Reversing obesity levels looks difficult. No single country managed to reduce obesity prevalence between 2000 and 2013.8 Obesity prevalence has stabilised in a few countries. However in 2017, the OECD said there was no clear sign, in any country, of a reversal in obesity levels.16

What is the impact of obesity?

Health impact

Just being overweight reduces the average lifespan by 2 - 4 years. Being obese can reduce it by up to 10 years.1

Obesity has multiple health consequences: type II diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, strokes, musclo-skeletal problems, mental well-being. According to Cancer Research UK, just being overweight causes 13 types of cancer, including two of the most common cancers: breast and bowel cancer. In the UK, being overweight is the biggest single preventable cause of cancer after smoking.1 3 4

Many obesity-related health issues are costly to treat. Most are also chronic conditions, so they require lifelong medical support.1

On the other hand, moderate weight loss — which is defined as losing 5 to 10% of body weight over one year — reduces risk of death from most causes, including cancer and type II diabetes.6

Economic impact

Treating obesity costs NHS Scotland a substantial £0.6 billion, according to one estimate. In addition, there are considerable indirect costs to the Scottish economy, because obesity reduces average working life, productivity and well-being. In total, obesity is estimated to cost Scotland between £0.9 billion and £4.6 billion per year.1

Data from McKinsey Global Institute suggests that the global economic impact of obesity is roughly £1500 billion ($2000 billion), or about 3% of global GDP. The McKinsey Global Institute calculated that obesity is the "second-largest human-generated burden", just behind smoking, but greater than war, violence, terrorism, alcohol, drug use, climate change or road traffic accidents.8 To give an illustration of scale, Scottish onshore GDP was around £150 billion in 2016,9 so 3% of this would translate into approximately £5 billion.

What causes obesity?

Obesity is influenced by highly complex factors: genetics, evolution, biology, psychology, society and economics.

But central to obesity is a simple energy balance: the balance between energy intake and energy expenditure. Or, the amount of calories eaten versus the amount of calories burned by activity.

People are naturally inclined towards a 'positive' energy balance i.e. to consume more energy than they require.

For most of human history, humans have had to cope with hunger, rather than abundance. Like any other animal, humans have evolved to find and use energy as efficiently as possible. Most animals have an instinct to seek out energy rich food. If food is abundant, most will over-consume. Excess energy is stored as fat. This fat is burned up during lean periods, when food is scarce.

Modern life is very different. Not only is food readily available, calorie-dense food is often cheap and low effort to prepare. Technology is taking over many tasks that would once have required physical labour: from housework, to transport, to jobs. Taking exercise is now a choice that requires time, effort and, to a certain extent, access to facilities.

Unfortunately, the human instinct to over-consume is not suppressed when food is abundant. Neither is there an instinct to burn off extra calories. So this inclination towards a positive energy balance is exacerbated by the modern environment. Extra energy gradually adds up over time, resulting in weight gain.

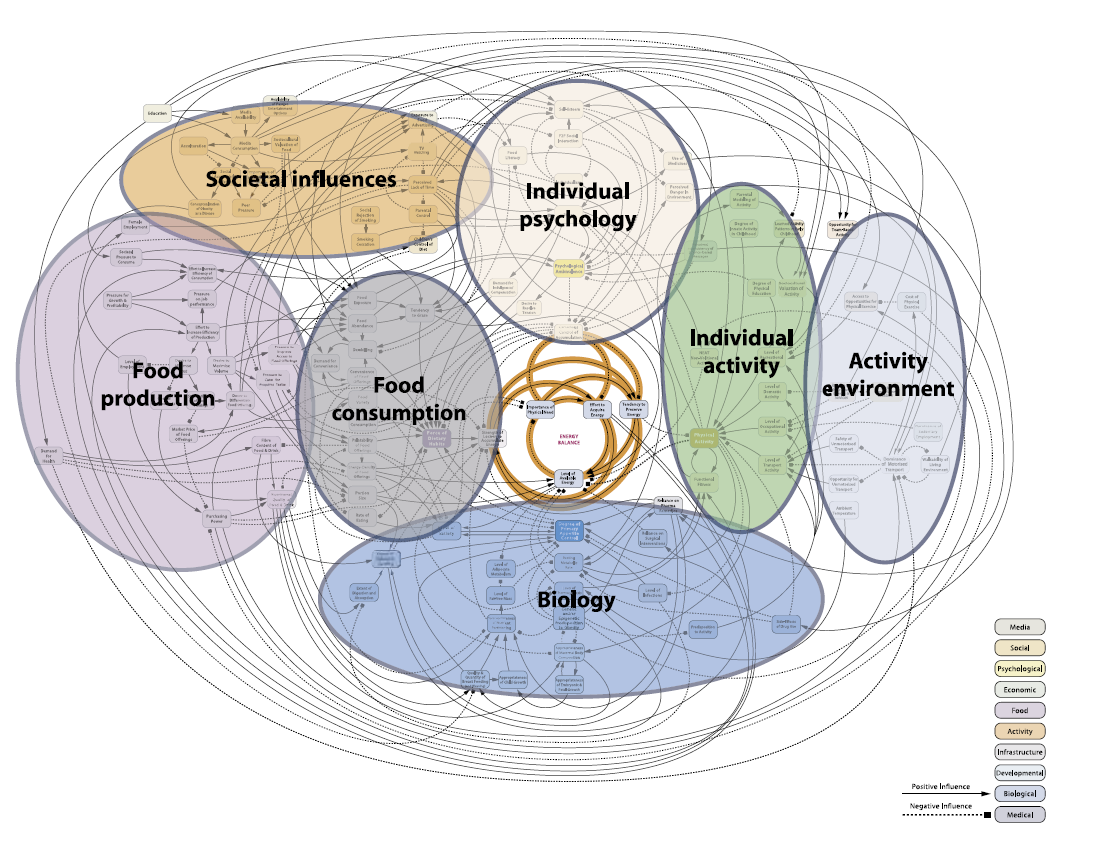

Some experts call this an "obesogenic environment". The UK government's Foresight project analysed the factors which feed into this obesogenic environment. They identified more than 100 variables that directly or indirectly affect obesity. The complexity of this system is shown in the Figure below.1

This complex diagram can be viewed in more detail online here. A breakdown and explanation of this diagram can be viewed here. 3 4

The Foresight report suggests that, whilst obesity can be seen as an 'energy balance' between diet and physical activity, complex factors influence what people choose to eat and how active they can be.

Diet and obesity

Food and drink play a key role in understanding obesity. Diet determines total energy intake i.e. the number of calories consumed.

Definition of healthy food and drink

This briefing will refer to 'unhealthy food or drink products’ and ‘unhealthy diets’. For food or drink products, we defined unhealthy as being high in fat, sugar, salt or energy density.

For fat, sugar and salt, we defined high as exceeding the thresholds set by the Food Standards Scotland and the Food Standards Agency. Both organisations use these thresholds to determine whether food or drink product is high in fat, sugar or salt. They are shown in the Table below.

| Nutrient | Low | Medium | High | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat | Total | Less than 3g | 3g to 17.5g | More than 17.5g |

| Saturated | Less than 1.5g | 1.5g to 5g | More than 5g | |

| Sugar | In food | Less than 5g | 5g to 22.5g | More than 22.5g |

| In drink | Less than 2.5g | 2.5g to 11.5g | More than 11.25g | |

| Salt | Salt | Less than 0.3g | 0.3g to 1.5g | More than 1.5g |

For energy density, we defined high as exceeding the recommended upper limit of the Scottish Dietary Goal for energy density. This is shown in the Table below.

| Scottish Dietary Goal | |

|---|---|

| Average Energy Density of Overall Diet: | 125 kcal per 100 g |

However, there is a difference between unhealthy food or drink products and an unhealthy diet. Overall diet is the sum of all the food and drink that someone consumes. It is possible to have an overall healthy diet, despite having the occasional unhealthy treat. It is possible to have an overall unhealthy diet by over-consuming food or drink products. Food Standards Scotland publishes advice on what a healthy diet looks like in their ‘Eatwell Guide’.2 In this briefing, an unhealthy diet is defined as not meeting these guidelines.

How healthy is the average Scottish diet?

Overall, Scotland has an unhealthy diet. The healthiness of the Scottish diet is monitored nationally, using the Scottish Dietary Goals. These were first established in 1996 and recently revised in March 2016.3 Recommendations cover:

Total energy intake

Average energy density

Fruit and vegetables

Oily fish

Red meat

Fats

Free sugars

Salt

Fibre

Total carbohydrate

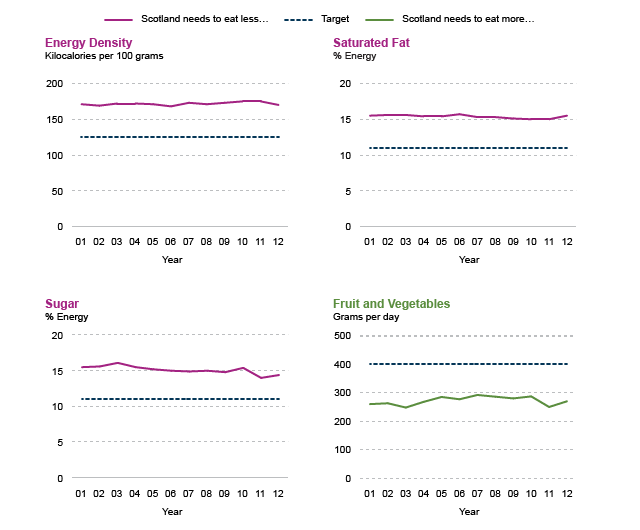

Unfortunately, Scotland has made no progress towards the Scottish Dietary Goals since 2001.

People eat (or drink) too many calories, too much sugar, too much fat and too much salt. Simultaneously, people do not eat enough fruit, vegetables, fibre or oily fish.1

What are people eating at home?

Food Standards Scotland (FSS) monitors the Scottish diet. Their analysis shows that Scotland eats too much discretionary food and drink. Biscuits, cakes, pastries and confectionery are all found in the top 10 of items bought. These are often high in sugar, fat and energy. Scotland also gets too much sugar from sugar-sweetened soft drinks.6

FSS recommends that Scotland needs to significantly reduce its intake of discretionary food by an estimated 50%.6

Socio-economic status affects what people eat at home. Households in the most deprived areas get a higher proportion of their total calories from confectionery, soft drinks and bread. Households from the least deprived areas get a higher proportion of their total calories from starchy carbohydrates, oil-rich fish, fruit and vegetables. (But also cakes and pastries!).6

There are also strong seasonal patterns, particularly at Christmas and Easter. In the 12 weeks before Christmas, there is a 10% increase in food and drink purchases. That includes a 20% increase in snack purchases, 32% increase in cake & pastry purchases and 54% increase in confectionery purchases. If eaten, that is equivalent to an extra 9000 calories, or a 1 kg gain in weight for every person in Scotland.6

Price promotions may influence type of food that people buy. In Scotland, around 40% of all take home food and drink is bought on price promotion. Discretionary food and drink are more frequently bought on promotion. In Scotland, around 50% of discretionary products were bought on promotion, compared to around 30% of staple or healthy products. FSS points to evidence that suggests other marketing strategies —advertising and product placement — may also encourage this.6

What are people eating away from home?

Food service (eating out of the home) is an important industry in Scotland. Restaurants, cafés, fast food outlets and retailers selling ‘meal-deals’ are all classified as food service establishments.11

In 2015, 948 million visits were made to food service establishments. Recent figures suggest that the Scottish food service industry is growing, and growing faster than the rest of the UK. People in the UK, including Scotland, visit food service outlets more frequently than other European countries (except Italy which has a very strong coffee sector).11

The food service industry therefore forms an important part of the Scottish diet. In 2015, the UK population got 11% of its total energy intake from eating out.13 Evidence from FSS shows that food and drink consumed away from the home is skewed towards less healthy options.14

In Scotland, quick service restaurants receive the largest proportion of visits. These are establishments that serve food quickly, often have minimal table service and include the typical fast food outlets. Compared to the UK, Scotland has a higher proportion of visits to quick service fish and chips, quick service bakery and quick service ethnic foods. The top five brands in 2015 were McDonald’s, Greggs, Tesco, Asda and Morrisons.11

In Scotland, many of the top food and beverage items consumed out of the home are less healthy. The most commonly bought items are chips or fries, cakes, biscuits, pastries and regular cola. Children (0-12 years) have unhealthy food and drink more frequently than adults.11

In 2015, only 4% of Scottish people said they ate out because they wanted a "healthy meal". This has declined since 2012.11

What is the cost of a healthy diet?

The ‘affordability’ of a healthy diet has been subject to some debate. Several studies have attempted to estimate this, but findings depend on precisely what factors are being compared.

Some studies have compared the cost of a healthy diet with an unhealthy diet. One UK modelling study found little difference between cost of the recommended ‘Eatwell Guide’ diet and the average UK diet: £5.99 versus £6.02 per adult per day. Although the study predicted that more money would be spent on fruit and vegetables, it found this cost should be balanced out by less money being spent on meat and other proteins. This suggests that, in theory, a healthy diet should be no more expensive than the average UK diet.18 In contrast, an international review found that an unhealthy diet could be up to $1.54 (£1.15) cheaper per 2000 calories than a healthy diet. Over a year that could save $560 (£420).19

Meanwhile, other studies have compared the costs of food and drink products. For example, a UK study found 1000 calories from unhealthy food products cost £2.50 in 2012. In contrast, 1,000 calories from healthy food products cost £7.49. Fruit and vegetables had the highest cost per 1,000 calories. Crucially, they found a growing price gap between healthy and unhealthy products.20

‘Affordability’ may differ depending on what units are used for making comparisons. Some have compared the price per 1000 calories whilst others compare the price per kilogram. It is also worth noting that many studies do not incorporate cooking costs when comparing diets.

Regardless, in the UK, deprived households use a greater proportion of their income to buy food. In 2016, the most deprived spent twice as much of their income on food compared to the most affluent: 17% versus 8% of income.21 This suggests the most deprived may be more sensitive to any differences in affordability.

Physical activity and obesity

Physical activity also plays a role in understanding obesity, as it determines total energy expenditure.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that people aim to:

Do at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic physical activity in a week

Or, do at least 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic physical activity in a week

Or, do an equivalent combination of the two.1

In 2015, 63% of adults in Scotland met these guidelines. There has been no significant change in activity levels since 2012.

Effect of age, gender and deprivation

Men are more likely than women to meet the guidelines: 67% compared to 59% of women in 2015.

Younger adults are more likely to meet the guidelines and activity steadily declines with age. People aged 16 - 24 years are the most active, with 75% meeting the guidelines in 2015. Adults over 75 years are the least active, with 31% meeting recommendations.

There appears to be an interaction between age and gender. As they get older, women are increasingly less likely to meet the guidelines compared to men in the same age category.

Deprivation reduces adult activity levels. In 2015, adults in the least deprived areas of Scotland were relatively active, with 71% meeting guidelines. But activity declines steadily with increasing deprivation. In the most deprived areas of Scotland, 50% of adults meet the guidelines. This pattern can be observed in both men and women.2

Sedentary activity

Sedentary activity is the opposite of physical activity. It is the amount of leisure time spent sitting, perhaps whilst eating, reading, watching TV or studying. Generally, people use less energy when sedentary.

On average in 2015, adults spent 5 hours on weekdays and 6 hours on weekend days being sedentary. This excludes time at work. Children were sedentary for just over 3 hours on weekdays and 4.5 hours on weekend days. This excludes time at school or nursery.3

Current obesity policy

Who is responsible for obesity policy in Scotland?

Policy to tackle obesity is spread across a variety of policy areas. This covers a mixture of devolved and reserved legislative competencies. This is likely to become more complicated and changeable as a result of the Brexit process.

Examples of largely devolved areas include: health, education, sport, agriculture, transport, planning and local government. Examples largely reserved areas include: consumer law, trade, social security and benefits.

Many policy interventions have been proposed in order to tackle obesity. This briefing will discuss the rationale and evidence behind 25 of these proposals. In each case, further work may be needed to identify the exact split between devolved and reserved responsibilities.

Overview of current obesity policy in Scotland

In 2008 Scotland's obesity strategy was launched. Called 'Healthy Eating, Active Living' (HEAL) it was in effect for 3 years.1

In 2010, the Scottish Government launched the Obesity Route Map (ORM), which was intended to strengthen the focus on obesity prevention.2 3 An accompanying Action Plan was released a year later, translating the ORM into 62 actions.2 5 Actions fell into four themes:

Energy consumption: actions to reduce exposure to high calorie food and reduce the number of calories eaten.

Energy expenditure: actions to increase opportunities for 'active travel', exercise and minimise sedentary behaviour.

Early years: actions to teach or encourage healthy habits from a young age.

Working lives: actions to encourage organisations to be responsible for the health of their employees.

The Joint Obesity Ministerial Group was set up in 2010 to monitor the Obesity Route Map.

In addition to the Action Plan, an analytic framework was developed.6 Sixteen key indicators have been used to monitor the impact of the ORM. Scotland's performance against these indicators is described in the most recent statistical bulletin.7 This is also described in the recent SPICe briefing on obesity.3

The Scottish Public Health Network (ScotPHN) recently reviewed the ORM and its progress (2015).9 With regards to the ORM actions, they found that:

Actions focussed on prevention rather than treatment.

A few actions successfully reached their milestones. Most actions showed progress towards their milestones.

Slightly more actions focussed on physical activity, compared to diet.

Many actions depended on individual behaviour and people choosing to opt into health initiatives.

The distribution of interventions was skewed towards "socio-cultural" measures (which they defined as attitudes, beliefs and values) and "physical environment" measures (which they defined as buildings, amenities and facilities).

There was less emphasis on "legislative" or "economic" measures. 10 9

ScotPHN identified issues with leadership. They said the ORM lacked central drive from the Joint Obesity Ministerial Group. Stakeholders were not systematically assigned actions to carry out. Rather, they were responsible for identifying actions to progress themselves.9

ScotPHN also identified issues with monitoring. This was often carried out by the lead agencies, which sometimes lacked the mechanisms necessary for effective monitoring. Some actions were monitored for a short time only. ScotPHN found limited information and evaluation, meaning it is hard to identify actions worth scaling up.9

Where next for obesity policy?

Scottish Government is planning to release a new obesity strategy in Winter 2017.

Tackling obesity in Scotland

The remainder of the briefing looks at how policy interventions could be used to reduce obesity levels in Scotland.

The first section explores four common themes in the debate surrounding obesity and how it ‘should’ be tackled.

Several organisations have recommended policy interventions for reducing obesity in Scotland or the British Isles. The second section reviews these publications and their recommendations.

In addition to producing this briefing, SPICe has conducted a survey of Scottish academics to ask them, in their opinion, what policy interventions would most reduce obesity in Scotland? The key results from this survey are also summarised in the second section.

Finally, the briefing takes a closer look at 25 policy areas which could be used to reduce obesity in Scotland.

What are the common areas of debate?

Four common themes emerge from the debate surrounding obesity and how best to tackle it. These are:

To what degree is obesity a personal responsibility or a societal responsibility?

What combination of treatment interventions and preventative interventions would be most effective?

In what cases should voluntary agreements with industry be used and when is government regulation more effective?

How can effective policy be developed with sometimes ‘imperfect’ knowledge?

The following four sections will explore the debate around each of these questions.

Personal or societal responsibility?

What causes obesity: personal choice or the environment?

A number of high profile publications — from academic experts to doctors — agree that there is an "obesogenic environment" in many developed countries, including the UK.1 2 3 4 5

Obesogenic is a term used to describe environments — places — which encourage obesity-promoting behaviours. For example, in many towns and cities, food and drink is easy to find, particularly calorie-dense, but nutrition-poor items. These products are often quick to eat, as they require minimal preparation or cooking. They may also be cheaper than healthier options. Meanwhile, jobs are increasingly sedentary. Transport in the UK is heavily reliant on car use. Technology has taken over many tasks that would once have required physical labour. Taking exercise is now a choice that requires time, effort and, to a certain extent, access to facilities.

This leads to an interesting question: to what extent are obesity rates influenced by factors outside of personal control? For example, the economy, structure of the job market, layout of streets and residential areas, urban planning, land use, education, societal customs, trade, marketing and advertising. Consequently, to what extent is obesity a personal responsibility or a societal responsibility?

Different policy options may be preferred, depending on the point-of-view taken in this debate.

Examples of interventions that treat obesity more as personal responsibility include: labelling food, weight management programmes and education. In general terms, they rely more on people consciously making — or learning to make — healthier choices.

Examples of interventions that treat obesity more as societal responsibility include: reformulation, restricting car use or making unhealthy food less accessible. In general terms, they aim to make healthier choices require less 'effort' (or make less healthy choices require greater 'effort').

Prevention or treatment?

Treatment interventions aim to help people reduce their weight. Examples of treatment-focussed interventions include, weight loss surgery, pharmaceuticals, diet and exercise programmes.

Prevention interventions aim to stop people from gaining weight. Examples of prevention-focussed interventions include: reducing calories in food, providing healthy school meals, encouraging walking or cycling.

The Scottish Government's obesity policy, the Obesity Route Map, was designed to have a greater focus on preventing obesity:

We need to redress the balance and ... spend more on prevention, leading to the need for less to be spent on treatment of the effects of obesity in years to come.

The Scottish Government. (2010). Overweight and Obesity in Scotland: A Route Map Towards Healthy Weight. The Scottish Government.

Others have argued that treatment and prevention should not be divorced from each other.

Treatment should not be divorced from prevention. The maintenance of weight loss and the prevention of weight regain is a critical yet under-researched component of treatment.

Butland, B., Jebb, S., Kopelman, P., McPherson, K., Mardell, J., & Parry, V. (2007). Tackling Obesities: Future Choices. Foresight Reviews.

Working with industry: voluntary approaches or government regulation?

Actions taken by the food and drink industry may have an effect on obesity trends for example relating to: the composition of food, drink and meals, portion sizing, package labelling, menu labelling, marketing, advertising, promotional activities and the location of facilities.

Examples of voluntary approaches

Businesses have been encouraged to undertake voluntary actions in order to support healthy choices. The UK Government has encouraged this through their 'Responsibility Deal' and the Scottish Government has encouraged this through their 'Supporting Healthy Choices Framework'. Examples of pledges include reducing salt content, removing artificial trans fats from products and providing calorie information. 1 2 3

More recently, greater focus has been directed specifically at reformulation. Reformulation involves altering food or drink products to limit the amount of sugar, fat, salt or calories.

Public Health England published sugar reduction guidelines in March 2017, to encourage manufacturers to reduce sugar by 20% by 2020 in 9 product groups:4

Breakfast cereals

Yogurts

Biscuits

Cakes

Morning goods

Puddings

Ice creams, lollies and sorbets

Confectionery

Sweet spreads

PHE set an interim target for industry: a 5% reduction in sugar content by August 2017. A report on progress towards these targets is due in March 2018. This will be followed by calorie and fat reduction guidelines in late 2017 and early 2018.4 6

Successes of a voluntary approach

Scottish food businesses have become involved with voluntary actions. For example, Food and Drink Federation Scotland is a trade association, representing food and drink manufacturers in Scotland. FDF Scotland participates in the Supporting Healthy Choices Framework. It has produced guidance for Scottish small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) on reformulation, encouraged front-of-pack nutrition labelling and has set up a reformulation common interest group.7

Voluntary reformulation programmes seem to have reduced salt consumption. In 2006, the Food Standards Agency launched a voluntary, but structured reformulation programme. This set industry targets and target deadlines, starting from 2006. The UK government ran a concurrent public awareness campaign starting from 2003. Between 2005 and 2011, there was a 5% reduction in the salt content of British households’ groceries. The Institute for Fiscal Studies found that this reduction was "entirely attributable" to product reformulation. The awareness campaign had little impact and, in general, consumers actually switched to higher salt products. This suggests that reformulation can successfully alter diets without relying on consumer behaviour.8

There is also evidence that some manufacturers are responding to sugar content guidelines. In March 2017, Nestle UK announced plans to reduce the sugar content in its products by 10%. This includes famous brands such as Kit Kat, Yorkie and Aero.9

Drawbacks of a voluntary approach

Reducing calorie, sugar and fat content has shown more mixed progress in Scotland. A Food Standards Scotland report looked at the nutritional content of products which were purchased by consumers to eat at home. Between 2010 and 2015, there was little change in total calories, sugars, fats and saturated fats, whether measured in total volume or on a per capita basis. 10

Durand et al. (2015) interviewed 50 industry partners of the UK Government Responsibility Deal. Many felt that the voluntary approach created an ‘uneven playing field’ between partners and non-partners.11 Firstly, not all businesses signed up to the deal. Secondly, of the businesses that did sign up, not all followed through on their promised actions. Some businesses felt that they had invested in changing, but received no substantial benefits, whilst there were no consequences for not taking part. By participating, some felt that they ended up at a competitive disadvantage. 11 13 14

For this reason, Food Standards Scotland has proposed that consideration should be given to government regulations that may create a more "level playing field".14

Examples of government regulation

The UK government is expecting to introduce a levy on the soft drinks industry from April 2018. The levy was announced in the 2016 Budget and legislation will be introduced in the Finance Bill 2017. The levy will be applied to producers and importers of sugar-added soft drinks. The rate will vary according to sugar content: a lower rate will be applied to drinks with more than 5g in 100ml and a higher rate applied to drinks with more than 8g per 100ml.16

Manufacturers and retailers — such as Lucozade, Ribena and Tesco — have announced plans to reduce the total sugar content of their products. The Chancellor of the Exchequer has reduced the forecast revenue from the levy, because of reformulation action taken by industry.17

However, some groups have called for government regulation to be considered in other areas, beyond reformulation.

"The evidence on voluntary approaches overall is not good, as is demonstrated by the poor response from industry to Supporting Healthy Choices.

On the basis of a lack of progress based on voluntary measures, it would appear that regulation may be warranted. Areas identified for exploration on this basis are as follows:

Price and promotions

Advertising and marketing

Portion size and reduction of calorie dense foods

Reformulation

Taxation of high sugar products including sugar sweetened beverages

Control of the built environment at a local level through licensing and/or planning conditions"

Food Standards Scotland (2016)14

What do the general public think?

Food Standards Scotland has been asking Scottish consumers what they think about introducing government regulations in two areas: reformulation and taxes.19

Reformulation: Three-quarters (75%) support government regulated reformulation.

Taxes: Around half (53%) are in favour of taxes on sugary drinks. Slightly less people are in favour of taxing other unhealthy food and drink categories. However, support for taxes increased to 59% if taxes meant that the price of healthy food would decrease.

More generally, public acceptance of government interventions can depend on several factors. One review article in BMC Public Health (2013) examined public attitudes towards tobacco, alcohol, diet and physical activity interventions. It drew on studies undertaken in Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand. Public acceptance was often related to:20

Target behaviour: Tackling smoking was often more popular than alcohol or diet. However, public attitudes did change over time and were influenced by new legislation or campaigns.

Type of intervention: Less intrusive interventions were preferred. Once interventions had been implemented, they often became more accepted. Interventions targeting children and young people attracted the most support.

Personal characteristics: Support for government interventions was often higher in groups who did not engage in the target behaviour. Overall, women and older people were more likely to support restrictive interventions.20

How to deal with imperfect evidence?

Ideally, obesity interventions would be chosen based on a background of strong evidence.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to gather a 'perfect' evidence base for many of the proposed interventions. For example, no experiment can really test how changing a country's agricultural policy would affect diet.

There are problems even where there is a lot of evidence. 'Randomised Control Trials' (RCTs)i are considered to be a 'gold-standard' method of testing interventions. For example, RCTs have been used to test pharmaceuticals2.

However, many RCTs take place in relatively simple and controlled experimental settings. They do not guarantee significant results in the complex mess of the real world.

Finally, there are interventions supported by a strong body of evidence. However, no single intervention appears sufficient to reverse the obesity epidemic. Many experts have warned that there is no 'silver bullet' for curing obesity. Many different interventions have been proposed across a range of areas. Each intervention has a different potential and has been tested to different degrees. This makes prioritising interventions difficult. 3 4 5 6

The McKinsey Global Institute argues that waiting for perfect evidence is not pragmatic:

"More investment is required, especially in understanding the effectiveness of intervention measures when they are applied as part of a comprehensive program. But society should also be prepared to experiment with possible interventions. In many intervention areas, impact data from high-quality, randomized control trials are not possible to gather. So, rather than waiting for such data, the relevant sectors of society should be pragmatic with a bias toward action, especially where the risks of intervening are low, using trial and error to flesh out their understanding of potential solutions."

McKinsey Global Institute Report (2014)4

This leaves several important questions for policy makers. How much evidence is necessary to choose an intervention? At what point is it appropriate to act on the evidence for an intervention? What combination of interventions has the best chance of working?

What policy interventions have been recommended?

Several organisations have published recommendations for tackling obesity in the UK or Ireland.

Recommendations from the McKinsey Global Institute

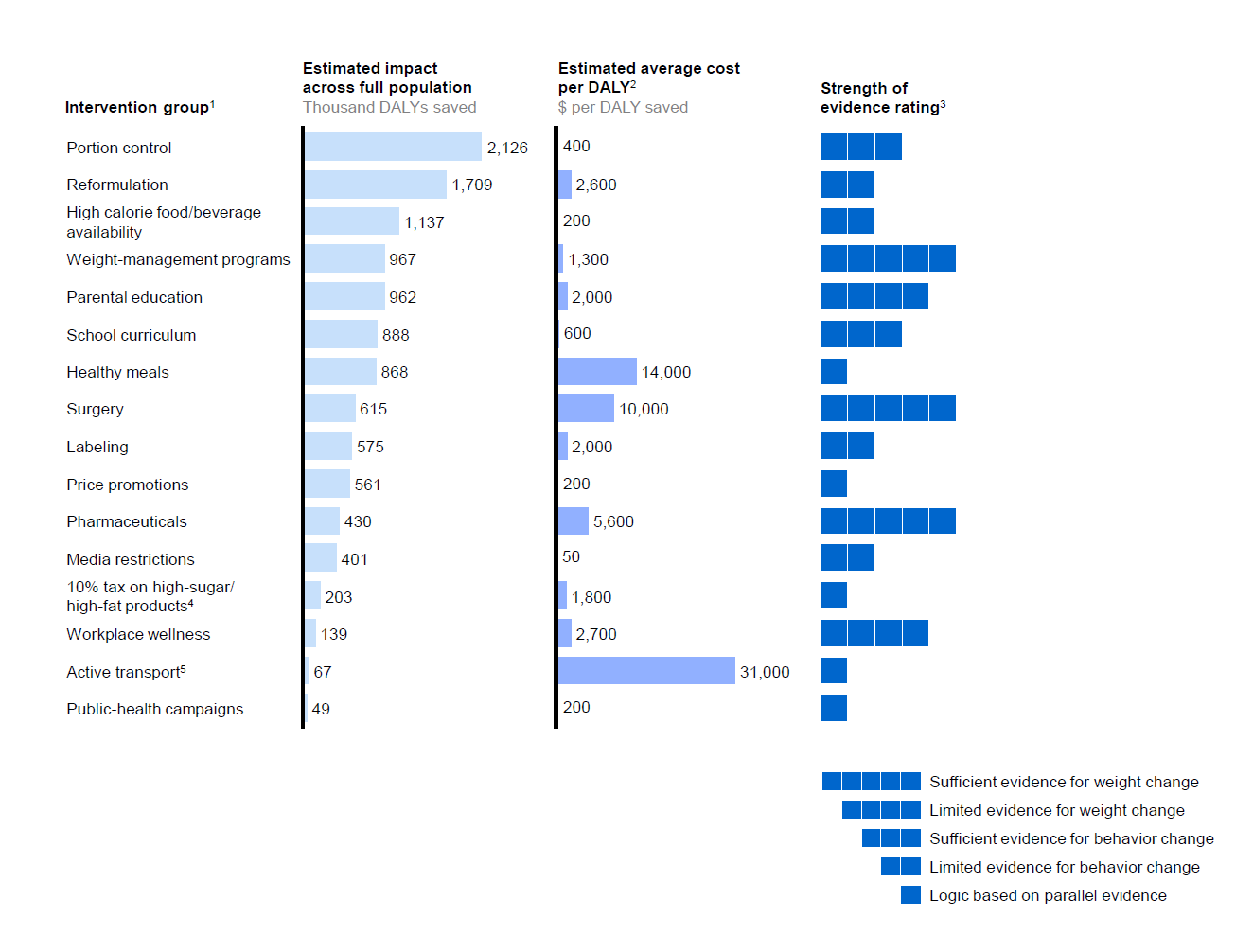

A recent high-profile report by the McKinsey Global Institute1 identified potential policy interventions. It also estimated their impact and cost-effectiveness. The authors identified 74 possible interventions. These interventions were being either used or piloted somewhere in the world, for example by central governments, local governments, employers, schools, health-care systems or the food industry.

The McKinsey Global Institute assessed interventions in three ways: they estimated the number of 'Disability Adjusted Life Years'i (DALYs) saved, cost-effectiveness and the strength of the evidence.

When ranked by DALYs saved, their top 10 interventions were:

Reducing portion sizes

Reformulation

Reducing the availability of high calorie food and drink.

Weight management programmes

Parental education

School curriculum

Providing healthy meals

Surgery

Labelling

Restricting price promotions

This report assessed cost-effectiveness using the following definition from the World Health Organisation (WHO):

Highly cost-effective: Interventions which cost less than 1 x per capita GDP per DALY saved. In the UK, that is roughly equivalent to less than £22,500 ($30,000) per DALY saved.

Cost-effective: Interventions cost 1 - 3 x per capita GDP per DALY saved. In the UK, that is roughly equivalent to £22,500 to £67,500 ($30,000 to $90,000) per DALY saved.

Not cost-effective: Any intervention which costs more than 3 x per capita GDP. In the UK, that is roughly equivalent to more than £67,500 ($90,000) per DALY saved.

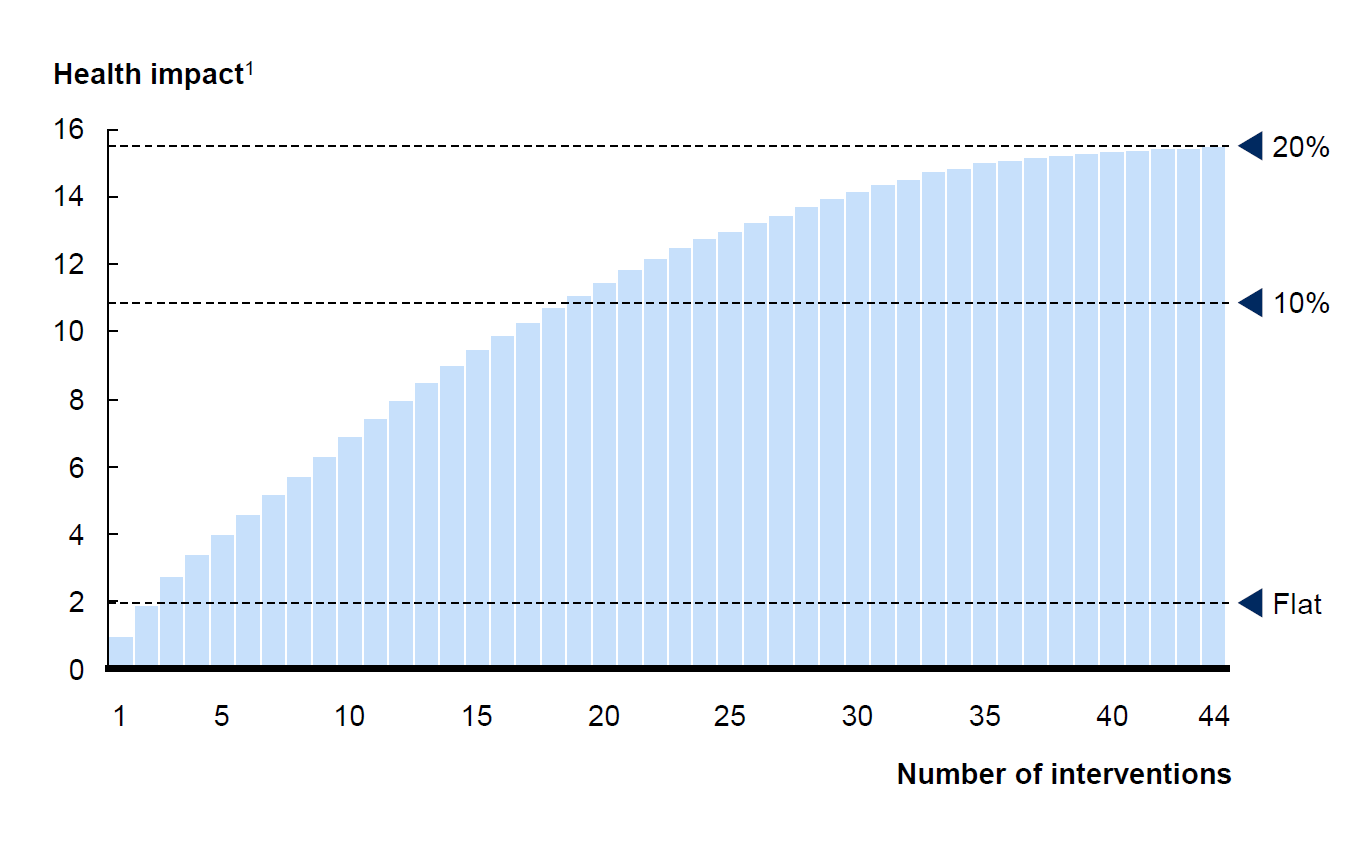

They found that most of the interventions they assessed were either 'highly cost-effective' or 'cost-effective'. This is shown in the figure above.

They also found that no single intervention could reverse obesity levels. Around 18 interventions were necessary to reduce the number of overweight or obese people by 10%. Around 40 interventions were necessary to reduce the number of overweight or obese people by 20%. They therefore recommend taking a broad approach to tackling obesity and implementing as many as interventions as possible:

No single solution creates sufficient impact to reverse obesity: only a comprehensive, systemic program of multiple interventions is likely to be effective. Our analysis suggests that any single intervention is likely to have only a small impact at the aggregate level.

If the United Kingdom were to deploy all the interventions that we have been able to size at reasonable scale, the research finds that it could reverse rising obesity and bring about 20 percent of overweight and obese individuals—or roughly the population of Austria—back into the normal weight category within five to ten years (Exhibit E2). This would have an estimated economic benefit of around $25 billion a year, including a saving of about $1.2 billion a year for the UK NHS.

Dobbs, R., Sawers, C., Thompson, F., Manyika, J., Woetzal, J., Child, P., … Spatharou, A. (2014). Overcoming obesity: An initial economic analysis. McKinsey Global Institute.

Recommendations from Food Standards Scotland

Food Standards Scotland (FSS) was established by the Food (Scotland) Act 2015. It is a 'non-ministerial department' of the Scottish Government. It is responsible for food safety, standards, labelling and inspection in Scotland. It also provides evidence-based diet and nutrition advice for Ministers, Scottish government and consumers.1

In 2016, FSS set out a number of proposals designed to specifically improve the Scottish diet (see Annex A on page 19 of their report). These proposals cover the following areas:

Price and promotions

Portion size reductions

Advertising and marketing

Reformulation

Taxation

Empowering consumers

Public information campaigns

Education on diabetes

Affordability and acceptability of a healthy diet

Provision of consistent dietary messaging

Recommendations from the healthcare profession

The medical profession have also published recommendations on tackling obesity in the UK and Ireland.

The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (AMRC) published recommendations for tackling obesity in 2013.1

The first four recommendations are targeted specifically at the healthcare profession:

Education for healthcare professionals

Provide weight management services

Introduce nutritional standards in hospitals

Increase support for new parents

However, the remaining recommendations are directed at the government or its partner agencies. The recommendations explicitly aim to tackle the obesogenic environment and make the healthy options the easy option.

Introduce nutritional standards in schools

Restrict fast-food outlets near schools

Restrict advertising of food high in saturated fats, sugar and salt

Introduce a sugary drink tax

Introduce a traffic light labelling system

Change the built environment to facilitate active travel

Similarly, in 2014 the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (RCPI) published recommendations on tackling obesity in Ireland.2 They recommended the following public policy measures:

Monitor the location of fast-food outlets

Restrict advertising of food high in saturated fats, sugar and salt

Monitor marketing activity on food and drink products targeting children

Introduce a sugary drink tax

Introduce a front-of-packet traffic light labelling system

Change the built environment to facilitate active travel

Results from a survey of Scottish academia

To support this briefing, SPICe conducted a survey of Scottish academics. More detailed information on this survey in included in Appendix A.

What was the aim of the survey?

In the opinion of Scotland's academics, what interventions would most reduce obesity levels in Scotland?

Background to the survey

The survey was based on the interventions listed in the McKinsey Global Institute report. Their catalogue of 74 possible interventions was shortened to 62 interventions, by condensing similar interventions together or removing interventions that were not relevant to a Scottish or UK context.

How was it carried out?

The survey was carried in May and June 2017. Academics working on obesity or related areas in Scotland were contacted. In total, 37 academics responded.

Academics were asked, in their opinion, which interventions they thought would most reduce obesity in Scotland.

They had 100 points to split between interventions in any way they liked. For example:

They could give 1 intervention all 100 points, if they thought that investing in a single intervention would be the best way of reducing obesity in Scotland.

They could select 50 interventions and give each one 2 points, if they thought that a broad approach would most reduce obesity in Scotland.

Or, they could do anything in between these extremes.

Results

The results should be interpreted with caution: they give a flavour of the respondents’ views and are not an assessment of the weight of evidence.

The 10 most popular interventions are shown in the table below.

| Interventions Receiving the Most Points | Total Points | % All Points |

|---|---|---|

| Facilitate walking and cycling | 267 | 7% |

| Reduce relative price of healthy food or drink by adding agricultural subsidies | 201 | 5% |

| Provide free or subsidised healthy school meals | 153 | 4% |

| Reformulation of food or drink products through government regulations | 151 | 4% |

| Provide health, diet and exercise education for children | 151 | 4% |

| Introduce levies on manufacturers or retailers of unhealthy food or drink | 143 | 4% |

| Restrict promotions on unhealthy food or drink through government regulation | 114 | 3% |

| Restrict advertising of unhealthy food or drink across all media through government regulation | 111 | 3% |

| Prescribe coupons for healthy food | 108 | 3% |

| Increase relative price of unhealthy food or drink through tax | 104 | 3% |

However, the central finding is the wide spread of support for interventions. This reinforces the fact that there is no single ‘cure’ for obesity. Scottish academics support a broad range of policy interventions.

Comparing recommendations

When making policy recommendations, each organisation has had a slightly different focus, used slightly different approaches or phrased policy interventions in slightly different ways.

Despite this, some policy interventions seem to be recommended by multiple organisations, although in some case, they may be phrased in different ways or specify slightly different details. For example, the AMRC recommends introducing a traffic light labelling system, whilst the RCPI recommends introducing a front-of-pack traffic light labelling system.

The table below gives a broad comparison of policy intervention areas recommended by different organisations. Potential areas highlighted by three or more sources include:

Taxing unhealthy food or drink products

Restricting advertising and marketing of unhealthy food or drink

Changing the built environment to facilitate active travel

Providing health education for parents, children and healthcare professionals

Providing healthy meals in schools, workplaces and hospitals

Limiting the availability of unhealthy food and drink

Better labelling of food, drink and meals

Exploring potential policy interventions

The remainder of the briefing explores potential policy interventions in more detail. Interventions are drawn from the McKinsey Global Institute report, which catalogued 74 possible interventions. They chose interventions that were being used or piloted somewhere in the world, for example by central governments, local governments, employers, schools, health-care systems or the food industry. The full list is available in Table E1 of the McKinsey report.1

This list of interventions was distilled down into 25 intervention groups: collections of similar interventions. These might tackle a similar aspect of obesity, be implemented in a similar way or have a similar aim. The 25 intervention groups are shown in the table below.

These 25 intervention groups can also be organised into 8 'themes': environmental, economic, media and marketing, food information, food content, healthcare and education. This is shown in the table below.

| Theme | Intervention Areas |

|---|---|

| Economic | Taxing unhealthy food and drink |

| Subsidising healthy food and drink | |

| Removing agricultural subsidies from unhealthy food | |

| Adding agricultural subsidies to healthy food | |

| Education | Public health campaigns |

| Providing health education | |

| Providing household management education | |

| Environment | Facilitate walking and cycling |

| Discourage car usage | |

| Neighbourhood safety and appeal | |

| Exercise facilities | |

| Food facilities | |

| Food access and availability | Access to healthy meals |

| Layout and contents of retailers | |

| Food content | Reformulation |

| Energy and portion size | |

| Food information | Labelling food and drink products |

| Labelling menus | |

| Healthcare | Surgery and pharmaceuticals |

| Weight management programmes | |

| Enabling a healthy lifestyle | |

| Incentivising a healthy lifestyle | |

| Media and marketing | Advertising |

| Price promotions | |

| Other promotional activity |

The following sections explore available background and evidence for each potential intervention group. The information for each intervention group is arranged in a table, formatted as follows:

| Aim | What is the aim of this group of interventions? |

| Current situation in Scotland | Summary and statistics about the current situation in Scotland. |

| Example interventions | List of example interventions. These are not recommendations, but examples of interventions that have been proposed. This is also not an exhaustive list. |

| Evidence that it will improve health? | Effect on healthy choices:Has SPICe identified evidence that these interventions would encourage healthy choices, such as reducing energy intake, choosing to eat more fruit and vegetables, or doing more exercise? Is this likely to have a small or large effect?Where is this evidence from: reviews or primary studies? Effect on obesity: Has SPICe identified evidence that these interventions reduce weight or BMI, either at the individual or population level? Is this likely to have a small or large effect?Where is this evidence from: reviews or primary studies? |

| Intervention currently in use? | Is this intervention currently being used in Scotland, the UK or elsewhere? |

Assessing the evidence

In the ideal world, there would be good experimental evidence that reduces obesity. Unfortunately, it may not always be feasible to measure change in population obesity. It may be easier to obtain data on energy intake, vegetable consumption, or exercise duration. Hence, two questions were used to assess the evidence behind interventions:

Is there evidence that the intervention encourages healthy choices?

Is there evidence that the intervention reduces obesity levels?

Evidence may come from:

Reviews: Reviews analyse the outcomes of multiple trials or experiments. Reviews can indicate if there is general consensus that an intervention works, or does not work.

Primary studies: A primary study reports the outcome of a single trial or experiment.

This system is based on the method used by the McKinsey Global Institute report.1

Generally, evidence from a review is considered more convincing than evidence from a primary study. However, a review based on multiple, poor-quality trials should be used with appropriate caution. Similarly, a high-quality randomised controlled trial (RCT) may be considered good evidence.

The evidence included in the following sections was identified between May and July 2017, whilst this briefing was being produced, and given the amount of research in this area may well not be comprehensive.

Economic interventions

Taxing unhealthy food and drink

| Aim | To discourage overconsumption of food and drink. |

| Current situation in Scotland | Scotland needs to reduce its intake of discretionary food and drink by 50%. That includes soft drinks, confectionery, biscuits, cakes, pastries and savoury snacks.1Increasing the price of unhealthy food and drink may discourage people from buying these items. The UK government will be introducing a levy on the soft drinks industry in 2018. It will be applied to producers and importers. There will be a lower rate for drinks with a total sugar content over 5 g per 100 ml and a higher rate for drinks over 8 g per 100 ml.2 |

| Example interventions | Tax products according to less healthy ingredients, such as: fat, saturated fat, added sugar, salt or energy density.Industry levy on products according to less healthy ingredients, such as: fat, saturated fat, added sugar, salt or energy density. |

| Evidence that it will improve health? | Healthy Choices: Evidence from ReviewsGeneral consensus that price disincentives would have a small, but significant, effect on sales. One review found that a 10% increase in price would decrease consumption of unhealthy food and drink by 6%.3Obesity: Evidence from ReviewsSo far, there is slight evidence to suggest that taxes or levies may change population weight, but the extent of weight loss is less clear. There is some suggestion that children, adolescents and people from low socio-economic groups are more sensitive to price changes.4 3 6 |

| Interventions currently being used? | Yes: Used already by several countries: USA, Mexico, Hungary, Finland, Norway and France.7 UK will be introducing a sugar levy in 2018. |

Subsidising healthy food and drink

| Aim | To encourage consumption of healthy food and drink products by lowering their price. |

| Current situation in Scotland | Scotland does not eat enough fruit, vegetables, fibre or fish. Deprived households use a greater proportion of their income to buy food: 17% spent by the most deprived versus 8% spent by the most affluent in the UK in 2015.1Some evidence that less healthy products and less healthy diets are cheaper.2 There also seems to be a growing price gap between less healthy and more healthy products.3 |

| Example interventions | Subsidise healthy food and drink for all.Or, subsidise healthy food and drink for target sub-groups. |

| Evidence that it will improve health? | Healthy Choices: Evidence from ReviewsEvidence of a small, but significant, effect on sales. One review found that a 10% decrease in price increased consumption of healthy food and drink by 12%. They estimated that subsidies had a slightly larger effect on dietary patterns than taxing unhealthy food.4Obesity: Evidence from ReviewsOne review found that a reduction in fruit or vegetable price reduced BMI. 4 |

Removing agricultural subsidies from unhealthy food

| Aim | To make unhealthy food more expensive by removing agricultural support. |

| Current situation in Scotland | Currently, farmers and producers receive subsidies from the European Union, via the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). The CAP has two pillars of funding. Under Pillar 1, called the Direct Payments Scheme, farmers receive a basic income. Under Pillar 2, the Rural Development Programme, achieving environmental and rural development objectives is rewarded.1 2No information identified on how this funding is distributed according to different types of agricultural produce. |

| Example interventions | Reduce, phase out or remove subsidies for production of the following:3

|

| Evidence that it will improve health? | Healthy ChoicesNo studies identified. ObesityNo studies identified. |

Adding agricultural subsidies to healthy food

| Aim | To make healthy food cheaper by giving agricultural support to farmers. |

| Current situation in Scotland | Currently, farmers and producers receive subsidies from the European Union, via the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). The CAP has two pillars of funding. Under Pillar 1, called the Direct Payments Scheme, farmers receive a basic income. Under Pillar 2, the Rural Development Programme, achieving environmental and rural development objectives is rewarded.1 2No information identified on how this funding is distributed according to different types of agricultural produce. |

| Example interventions | Introduce or increase subsidies for:3

|

| Evidence that it will improve health? | Healthy ChoicesNo studies identified. ObesityNo studies identified. |

Education interventions

Public health campaigns

| Aim | To help people understand how to maintain a healthy weight. |

| Current situation in Scotland | Most people in Scotland (84%) feel that they have clear advice on what makes a healthy diet. Most agree (85%) that an unhealthy diet can lead to health problems.On average, people in Scotland recognise 8 out of 11 healthy eating messages, based on the Eatwell Guide. However, people admit to following only 2 of these consistently:

|

| Example interventions | Run national public health campaignsRun local public health campaignsEffective public health media campaigns:3

|

| Evidence that it will improve health? | Healthy Choices: Evidence from ReviewsCampaigns can affect population behaviour in the short term. In general, large-scale campaigns can cause 9% more people to adopt the promoted behaviour. Greater behavioural change is seen when the action is required by law. Although this seems modest, campaigns can result in significant population health gain, because of the scale of these projects.4 Shifting public attitudes can be an important outcome. Behaviours may be perceived as less acceptable; this has been happening with smoking and drink-driving.5Campaigns can also have unintended consequences. Concerns have been raised about potential negative effects around body image.6Obesity: Evidence from Reviews Campaigns so far have not generally been effective at causing weight loss or weight loss maintenance, particularly in the long-term. Community campaigns are not necessarily more effective than national campaigns. The more successful campaigns have generally been targeted children, whose behaviour can be more easily modified.6 |

| Intervention currently being used? | Yes. Campaigns used to promote healthy diets, exercise and weight loss. Also used in wider health or societal issues: smoking, cancer screening, alcohol and drug use, drink driving. |

Providing health education

| Aim | To help people understand how to maintain a healthy weight. |

| Current situation in Scotland | Health education is currently available to schoolchildren in Scotland, under the national Curriculum for Excellence.1 |

| Example interventions | Provide health, diet and exercise education for adultsProvide health, diet and exercise education for parents Provide health, diet and exercise education for children |

| Evidence that it will improve health? | Obesity: Evidence from ReviewsFor children:

|

Providing household management education

| Aim | To help people understand how to prepare healthy meals and manage a household budget. |

| Current situation in Scotland | Food prepared at home is usually less energy dense, so limited cooking skills may be a barrier to a healthy diet. People who lack cooking skills may rely on more convenience foods. In the UK, 63% of people cook a main meal at least 5 times per week, whilst 84% live in a household with a 'main food provider' who cooks a main meal at least 5 times per week. Cooking skills are affected by gender, age socio-economic status. Men, the young (19 - 34 years) and people from low socio-economic groups are the least confident cooks.1No statistics identified on budgeting and household management skills in Scotland or the UK. |

| Example interventions | Provide cooking classesProvide budgeting and household management classes |

| Evidence that it will improve health? | Healthy Choices: Evidence from ReviewsMixed evidence that providing cooking education for adults improves diet quality. However, one review warned that many studies in this area were low quality, so the results should be interpreted with caution.2Some evidence that children with greater food literacy have healthier diets.3 However, mixed evidence that providing cooking education for children improves diet.4 Similarly, many studies were low quality. Reviews warn that many studies in this area are low quality, so the results should be interpreted with caution.No studies identified showing that providing household management classes improves diet.ObesityNo studies identified. |

Environmental interventions

Facilitate walking and cycling

| Aim | To enable more people to use cycling and walking facilities: for exercise, for leisure and for travelling (known as "active transport"). |

| Current situation in Scotland | Scotland does not meet recommended levels of physical activity.1 Active transport is used for less than a quarter of journeys. In 2015, walking accounted for a fifth of all journeys (22%), whilst cycling accounted for 1% of all journeys. Children and young adults were more likely to use active transport: 49% of children in full-time education walked to school and 1% cycled. Commuters were less likely to use active travel: 14% of adults walked and 2% cycled to work. Most journeys in Scotland tend to be short. In 2015, a quarter (23%) of all journeys were under 1 km long and a further quarter (25%) were 1 - 3 km.23The Scottish Government promotes cycling through its Cycling Action Plan4 and walking through its National Walking Strategy.5 |

| Example interventions | Invest in walking and cycling facilities.Incorporate active travel into all future planning.Plan active travel routes to link up 'destinations': homes, schools, shops, workplaces and leisure facilities.Make active travel routes feel physically safe from traffic.Ensure active travel infrastructure is well-maintained and well lit so it is accessible, regardless of gender, age or ability.Recognise that walkers and cyclists have different needs. |

| Evidence that it will improve health? | Healthy Choices: Evidence from ReviewsLiving in areas with good walking or cycling facilities can result in people doing more physical activity and choosing 'active travel' over cars. 6 7 8 9 10Obesity: Evidence from Review and Primary StudiesFew studies look at the effect of active travel on obesity.11 Active transport does seem to have multiple health benefits12, especially cycling13. |

| Interventions currently being used? | Yes: In the 1970s, cycling levels were low across Europe. The Netherlands, Denmark and Germany invested heavily in active transport facilities in the mid-1970s. Currently, they have high levels of active travel. For example, in the Netherlands, 28% of all journeys are made by bike and 18% by foot. It has an obesity rate of 13%, less than half that of Scotland.14 15 16 |

Discourage car use

| Aim | To encourage people to walk or cycle, rather than use their car. |

| Current situation in Scotland | Most journeys in Scotland tend to be short. In 2015, a quarter (23%) of all journeys were under 1 km long and a further quarter (25%) were 1 - 3 km.Yet active transport is used for less than a quarter of all journeys. In 2015, walking accounted for a fifth of all journeys (22%), whilst cycling accounted for 1% of all journeys. 1 2 |

| Example interventions | Discourage car use. This could include:

|

| Evidence that it will improve health? | Healthy Choices:No studies identified.Obesity: No studies identified. |

| Intervention currently being used? | Yes. By many Dutch, Danish and German cities. Since the 1970s, parking supply was deliberately reduced, speed limited around residential and active travel infrastructure, travel routes limited and car‐free zones introduced. Because good quality active travel facilities are generally available, this can mean that active travel is more convenient. In the Netherlands, 28% of all journeys are made by bike and 18% by foot. It has an obesity rate of 13%, less than half that of Scotland. 3 4One review suggests that British urban areas have more large roads and more car parking than the typical Dutch, Danish or German city. Car‐free zones are less common in the UK. Traffic calming is less widespread and speed limits are generally higher. Cycling facilities are also of an "inferior quality".3 |

Neighbourhood safety and appeal

| Aim | To encourage more people to do exercise, walk and cycle in their own neighbourhood. |

| Current situation in Scotland | It has been suggested that physical activity is affected by people's perception of road safety, neighbourhood safety and appeal. Road safety:

|

| Example interventions | Provide safe routes for walking, cycling, exercise and leisure.Reducing the speed, volume of traffic and air pollution around these routes. Improve the perception of neighbourhood safety:

|

| Evidence that it will improve health? | Healthy Choices: Evidence from ReviewsActive transport increases with better local infrastructure and traffic safety. 7 8Neighbourhood disorder, littering, vandalism and poor appearance appear to reduce physical activity.7 8Neighbourhood maintenance, street lighting and access to green space appears positively associated with physical activity.7 813Obesity: Evidence from Primary StudiesOne study found safety from traffic is correlated with lower population weight.14Two studies found high neighbourhood crime levels or disorder are associated with high BMI levels.14 16Neighbourhood aesthetics do not appear to influence obesity.16 |

Exercise facilities

| Aim | To encourage more people to do exercise, walk and cycle in their own neighbourhood. |

| Current situation in Scotland | The Scottish population does not meet recommended levels of physical activity. 1 No statistics identified on the number or distribution of exercise facilities in Scotland. |

| Example interventions | Increase the number of exercise facilitiesIncrease physical exercise facilities in deprived or high-obesity areasInvest in school facilitiesInvest in community-owned facilities |

| Evidence that it will improve health? | Healthy Choices: Evidence from Primary StudiesSome studies suggest that travel distance to the nearest exercise facilities - such as a gym, sports centre or swimming pool - is related to activity levels.Access to facilities, rather than distance may be more important factor. Poor access is caused by: poor transport options, lack of financial resources, age, medical problems, or sense of not 'belonging' at facilities.Choosing to use exercise facilities may be partly influenced by attitude. 2 3 4Obesity: Evidence from Primary StudiesSome evidence that nearby facilities may reduce the BMI of the local population.26 |

Food facilities

| Aim | To improve diet by increasing the number of facilities where healthy food can be purchased. |

| Current situation in Scotland | The US has 'food deserts': areas with nowhere to buy affordable, healthy food. These occur more frequently in more deprived areas.1No evidence of food deserts in the UK or in Scotland.13456But there may be more fast food retailers in deprived areas. The concentration of fast food outlets in poor areas appears to have increased over time. 4 |

| Example interventions | Increase the number of food shops.Increase availability of food shops in deprived or high-obesity areas.Limit or reduce the number of fast food retailers.Limit or reduce the number of fast food retailers in deprived or high-obesity areas.Limit or reduce the number of fast food retailers near schools. |

| Evidence that it will improve health? | Healthy Choices: Evidence from ReviewsIn the UK, the number of food retailers does not appear to be correlated with deprivation. For example, in Glasgow, the most deprived areas actually had the most food retailers per 1,000 people in 2009. Physical proximity to food retailers does not seem to be correlated with a healthy diet.1 3 4 5 6Healthy food choices do seem to be available from food retailers within deprived urban areas. But there is some evidence that healthier food — particularly fruit and vegetables — may be more expensive, lower quality or less varied in these areas.1 14Obesity: Evidence from Reviews or Primary LiteratureNo evidence of food deserts in Scotland, the UK or most of Europe, therefore little evidence of impact on obesity.13456 Even in the US, few studies have examined how living in a food desert affects health and obesity.20However, in the UK, there is evidence of fast food venues in deprived areas.4 Physical proximity to more fast food retailers, but not full-service restaurants, does seem to predict local obesity trends.2223 |

| Interventions currently being used? | Yes: Several US cities and states have introduced interventions to tackle food deserts.20 |

Food access and availability interventions

Access to Healthy Meals

| Aim | To encourage a healthy diet by improving access to and availability of healthy meals in schools, higher education establishments and workplaces. |

| Current situation in Scotland | School and higher education establishments form a major part of students' food environment. Similarly the workplace is forms the major part of employees' food environment.1 This makes these populations a 'captive audience'.Public schools in Scotland are required to have a "health-promoting" environment under the Schools (Health Promotion and Nutrition) (Scotland) Act 2007.2There are minimum nutritional standards for the food and drink available in Scottish public schools. These are set by the Nutritional Requirements for Food and Drink in Schools (Scotland) Regulations 2008 3 The Scottish Government provides free school meals for all children 4-7 years old. Children up to 18 years are eligible for free school meals if they come from families receiving income support.4 Under EU law, food in workplaces and higher education establishments must be safe to eat, accurately labelled and traceable (The General Food Law Regulation (EC) 178/2002).5 However, the food environment is not currently regulated. |

| Example interventions | Provide free or subsidised healthy school meals Increase choice of healthy options in schoolsReduce access to unhealthy food in schoolsDisplay healthy foods more prominently in school canteensProvide free or subsidised healthy meals in the workplaceIncrease choice of healthy options in the workplaceReduce access to unhealthy food in the workplaceDisplay healthy foods more prominently in work canteens |

| Evidence that it will improve health? | Healthy Choices: Evidence from ReviewsEvidence that interventions in the school and higher education food environment increases healthy choices.6 7 In the workplace, combining food environment and education interventions, seems to improve employee diet.8Obesity: Evidence from ReviewsSmall number of studies suggest that interventions in the school food environment decreases BMI.6 Little evidence that workplace interventions affect BMI, particularly over the long-term.8 |

Layout and contents of food retailers