Justice Committee

Presumption Against Short Periods of Imprisonment (Scotland) Order 2019

Introduction

There has, since February 2011, been a presumption against the courts imposing prison sentences of three months or less. This was created by section 17 of the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010, amending section 204 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995.

Specifically, the amendments added the following text to the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995:

“(3A) A court must not pass a sentence of imprisonment for a term of 3 months or less on a person unless the court considers that no other method of dealing with the person is appropriate.

(3B) Where a court passes such a sentence, the court must –

(a) state its reasons for the opinion that no other method of dealing with the person is appropriate, and

(b) have those reasons entered in the record of the proceedings.”

This placed a restriction on the courts in Scotland not to sentence anyone to prison for a period of up to 3 months unless the court felt that there were no other means of dealing with the person, such as a community-based alternative.

The law also allowed the Scottish Ministers - by affirmative statutory instrument (SSI) - to substitute for the number of months specified in subsection (3A) another number of months. The Presumption Against Short Periods of Imprisonment (Scotland) Order 2019 seeks to do this – substituting 12 months for the current three months.

This report by the Justice Committee sets out our deliberations on the proposal by the Scottish Government to do so via the means of an SSI.

Scrutiny by the Justice Committee

The Committee received over 40 submissions of written evidence on the SSI. This is a fairly unprecedented response for a statutory instrument and reflects the importance of the change. The Committee is grateful to all those organisations and individuals who took the time to send us their views. The majority of submissions were favourable to the proposed change, although a number raised issues around resources. Only a small number disagreed outright with the proposed change.

The Committee also took oral evidence over two sessions, 4 and 11 June, from the following witnesses:

4 June 2019

Laura Hoskins, Head of Policy, Community Justice Scotland;

Colin McConnell, Chief Executive, Scottish Prison Service;

James Maybee, The Highland Council, representing Social Work Scotland;

Kate Wallace, Chief Executive, Victim Support Scotland;

Dr Katrina Morrison, Board Member, Howard League Scotland;

Dr Sarah Armstrong, Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research, University of Glasgow;

Professor Cyrus Tata, Director of the Centre for Law, Crime and Justice, University of Strathclyde; and

Rt Hon Lord Turnbull, Senator of the College of Justice, and Graham Ackerman, Secretary, Scottish Sentencing Council.

11 June 2019

Humza Yousaf MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Justice, Scottish Government and his officials.

Views of the Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee

The SSI was also scrutinised by the Parliament's Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee. This Committee agreed at its meeting of 28 May 2019 that no points arose in relation to the SSI.

Short sentences - facts and figures

As stated above, the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 created a presumption against the courts imposing prison sentences of three months or less. This is not a prohibition on such sentences, but the court must not use the option unless it “considers that no other method of dealing with the person is appropriate”.

This is not the only presumption affecting the use of custodial sentences. Similar provisions, based on the circumstances of the offender rather than the length of proposed sentence, apply to those who have not previously received a custodial sentence and young offenders (under 21). See sections 204(2) and 207(3) of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995.

The general limits on the sentencing powers of Scotland's criminal courts allow them to impose custodial sentences up to the following limits:i

High Court of Justiciary (solemn procedure only) – life

Sheriff courts under solemn procedure – five yearsii

Sheriff courts under summary procedure – 12 months

Justice of the peace courts (summary procedure only) – 60 days

If the changes set out in the SSI become law, the extension in the scope of the presumption to 12 months would mean that it covered the general sentencing powers of the courts under summary procedure.

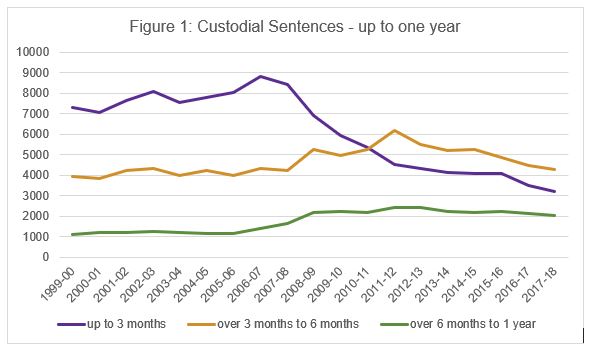

Since 2006-07, there has been a substantial decrease in the use of custodial sentences up to three months. Figures have fallen from 8,825 sentences in 2006-07 to 3,182 in 2017-18. Given that the current presumption against such sentences came into force in February 2011, it may be noted that the fall in their use started before the presumption came into effect.

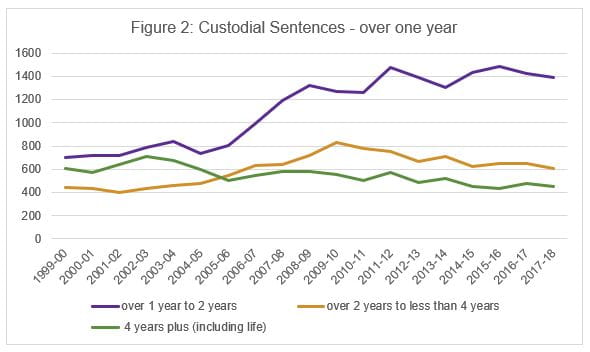

Figures 1 and 2 below show the use of custodial sentences broken down by length of sentence.iii The two charts show that the use of custodial sentences of other durations has varied during the period. Figure 2 shows an upward trend in sentences of over 1 year to 2 years over this time period.

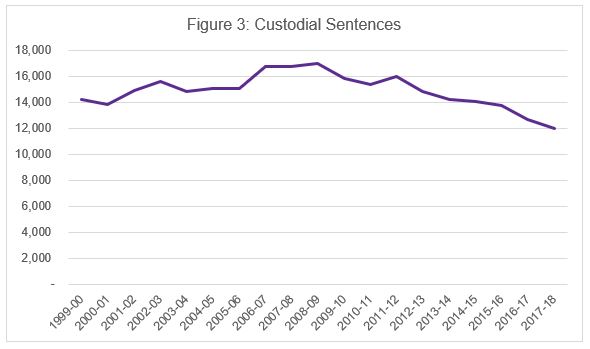

Figure 3 shows that the overall use of custodial sentences rose then fell during the period – peaking at 16,946 in 2008-09 but falling to 11,973 in 2017-18.

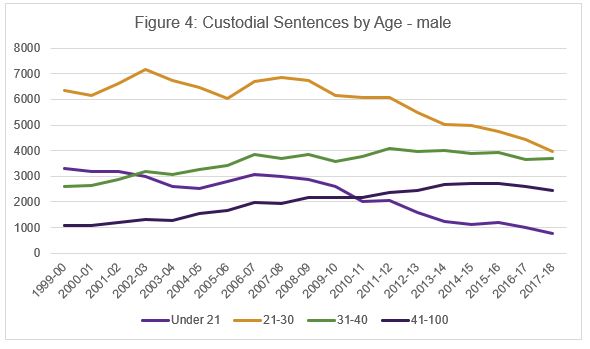

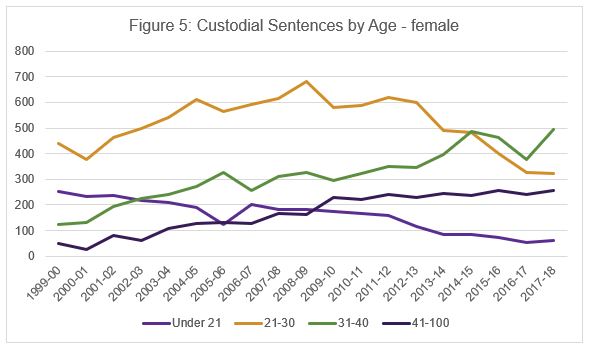

Changes in the use of custodial sentences during the period also differ depending on the age of the offender. In general, there was a fall in custodial sentences being imposed on those in younger age categories (under 21 and 21-30) but a rise in those for older age categories (31-40 and 41-100). This is shown in Figures 4 (male) and 5 (female).

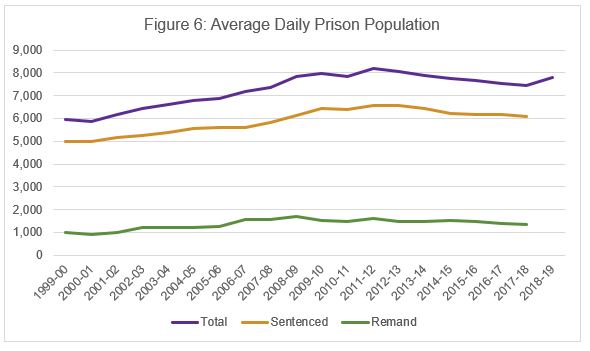

It is worth considering these trends in relation to the overall situation in terms of the prison population in Scotland. Figure 6 uses Scottish Prison Service (SPS) figures, mainly available on its website under the heading of SPS Prison Population. It shows the total average daily prison population in Scotland during the period 1999-2000 to 2018-19. It also provides a breakdown into sentenced and remand prisoners up to 2017-18.iv

Before last year, the total average population might be described as generally increasing until 2011-12 (when it peaked at 8,179) followed by a period of levelling off and a gradual decrease. However, the most recent annual figures show an increase, from 7,464 in 2017-18 to 7,789 in 2018-19.

Weekly population figures published by the SPS for the start of 2019-20 (up to 7 June 2019) have been consistently over 8,000 – ranging between 8,099 on 19 April to 8,221 on 17 May.

In international terms, Scotland has one of the highest prison population rates in Europe; approximately 140 per 100,000.1 The rate is 79 in the Republic of Ireland, 65 in Norway and the European average is 124 (with a median of 103).

What is being proposed and why?

The Scottish Government has indicated that the presumption against short sentences is designed to encourage a reduction in the use of short-term custodial sentences and a related increase in the use of community sentences. The purpose of the instrument is to extend the presumption against short sentences from sentences of 3 months or less to sentences of 12 months or less.1

The Scottish Government believes that whilst prison remains the right place for those who pose a significant risk to public safety, there is compelling evidence, in their view, that short sentences do little to rehabilitate or to reduce the likelihood of reoffending; further, they can disrupt housing, employment and family stability, thereby adding to the risks of re-offending in the future. Extending the presumption against short sentences is intended, according to Ministers, to improve the chances of individuals paying back for offending, being effectively rehabilitated and preventing reoffending.

The presumption is not mandatory and the court, when sentencing, still retains the discretion to pass the most appropriate sentence based on the facts and circumstances of the case.

Whilst accepting that some caution should be applied about making direct comparisons, the Scottish Government believes that the current rate of imprisonment in Scotland is too high, in particular when viewed against the rates in other comparable European countries . According to the Council of Europe, the median for European countries is 102.5 prisoners per 100,000 population and the average is 123.7. Scotland has a prison population rate of 136.5i. Extending the presumption is intended to reduce churnii in the prison system, which, the Scottish Government believes, will help to improve the quality of interventions with individuals who need to be in prison. Longer term, extending the presumption is expected to have some impact on prison population though this is primarily related to an indirect contribution to reducing reoffending.

In evidence to the Committee, Humza Yousaf, Cabinet Secretary for Justice said—

Extending the presumption is not a silver bullet but must be seen as part of a broader evidence-led, preventative approach.2

The Cabinet Secretary was also of the view that the presumption against short sentences had to been seen in the context of a move to use community-based alternatives which, in his view, were more likely to succeed and result in fewer reconvictions and therefore help with rehabilitation. He did not place a limit on the scope for rehabilitation, telling the Committee that—

I have to believe—and I do believe—that people have the ability to rehabilitate. If I believe that—as I do—I have to ask myself what the evidence demonstrates is the most effective way of rehabilitating somebody. 2

The Scottish Government has noted that extending the presumption is being carried out alongside additional protections for victims, including the implementation of the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018iii. The Scottish Government has said that it is committed to extending the presumption once these additional safeguards for victims of domestic abuse are in force, as concerns were raised about the potential impact on victims if offenders are not in custody. The policy objective is to support measures which reduce reoffending, which is, in its view, beneficial to victims and society.

The Scottish Government consulted on its proposals between 25 September 2015 and 16 December 2015 to ascertain views on proposals to strengthen the presumption against short sentences. An analysis of the consultation responses revealed that 85% of respondents (53 of 62) were in favour of an extension to the minimum period and, of those who expressed a view, 84% (37 of 44) indicated that the new minimum period should be set at 12 months.1

According to analysis conducted by the Scottish Government, a 20% reduction in the use of custodial sentences of 12 months or less would be likely to result in the imposition of an additional 1,300 community sentences a year. The Government estimates that the additional resource requirement created by this increase will be in the region of £2.5 million per year. The Government has stated that "savings to Scottish Prison Service are not expected to be releasable but are expected to enhance support in prisons as officers spend less time dealing with receptions".1

The Scottish Ministers have said that they have provided an additional £4 million in each of the past two years to support community sentences and this was increased to £5.5 million in the 2018-19 budget specifically to support preparations for extending the presumption against short sentences. The Government stated that this additional support is being continued in 2019-20 and that the uptake of community sentences will continue to be monitored closely, alongside the number and length of custodial sentences imposed.1

There are still a number of questions as to whether the sums outlined above by the Scottish Government will provide sufficient additional funding to support community sentences and the preparations for extending the presumption against short sentences, or whether this will merely meet existing demand. The Committee covers this point in more detail later in the report.

Key issues

Current impact of short sentences

A significant proportion of those currently in prison are serving sentences of up to 12 months. Many of those providing evidence to the Committee made comments on the impact that shorter sentences can have on a person, their family and friends, and their longer-term prospects after serving their sentence. The views of the Chief Inspector of Prisons in Scotland, Wendy Sinclair-Gieben, were typical of these. She said that—

Whilst prison remains the right place for those who pose a significant risk to public safety, there is compelling evidence that short sentences do little to rehabilitate or to reduce the likelihood of reoffending. It can also disrupt housing, access to benefits, employment and family stability.1

She also said that “individuals released from short sentences of 12 months or less are reconvicted nearly twice as often as those sentenced to a community payback order.”. In her view, effective and credible community-based alternatives to custody have helped to achieve a 19- year low in reconviction rates. She argued that extending the presumption will hopefully encourage a further shift towards community disposals and the associated positive outcomes.1

Dr Sarah Anderson, Dr Johanne Miller and Dr Kirstin Anderson from the University of the West of Scotland made particular reference in their submission to the disruption that can be caused to a person's existing drug treatment programme by a short stay in prison. They also noted that those on short sentences suffer in particular as prisons have a shortage of treatment programmes if sentences are of four years or less.3

Dr Jamie Buchan and Dr Christine Haddow of Edinburgh Napier University commented on the issue of mental health and well-being. They noted the prevalence of mental disorder among imprisoned individuals nationally and internationally. In this context, they argue that imprisonment is harmful to those with mental disorders as it can further exacerbate such conditions. In their view, a "reduction of longer custodial sentences for those with such diagnoses is undoubtedly desirable". However, in their opinion, regardless of length, custodial sentences for this population often break any existing ties with formal and informal mental health care being provided in the community and place further strain on an already overstretched prison service to manage the complexities of mental health with inadequate resources.4

In their evidence to the Committee, Dr Hannah Graham (University of Glasgow) and Professor Fergus McNeill (University of Stirling) also expressed reservations about short sentences, arguing that using these for sentences that were not serious was "short-sighted and costly". 5

Their evidence cited the relative costs of prison versus alternatives in cases of shop-lifting, noting that, in the past five years, 9,020 custodial sentences under 12 months were imposed for shoplifting. In their view, this falls short of two oft-cited thresholds for custody: shoplifting is not in itself a serious crime, nor does it constitute a risk of significant harm requiring incarceration on grounds of public protection.5

Dr Graham and Professor McNeill noted that each shoplifting crime incident has an estimated average cost of £141. While precise calculations for short prison sentences for shoplifters are not available, they estimated the average annual cost per prisoner place as £35,325. In contrast, the average unit cost of a Community Payback Order is £1,771, and electronic monitoring tagging is £965. In their view therefore, "it is hard to see how the public interest is served by people convicted of shoplifting serving months in prison only to be released to the same circumstances and with their risk of reoffending likely exacerbated by the collateral consequences of imprisonment."5

Effectiveness of the Scottish Government's proposal

The question of how effective the Scottish Government's proposal may turn out to be must cover two interlinked issues. Firstly, there is the question of whether it is desirable to reduce the use of short(er) custodial sentences. Secondly, there is the issue of whether an extended presumption is likely to be an effective way of achieving a reduction (alone or as part of a package of other measures).

A number of submissions commented in particular on the Scottish Government's policy aims behind its proposal and whether these will be achieved. For example, the Scottish Prison Service (SPS) stated that while prison remains the right place for those who pose a significant risk to public safety, "there is compelling evidence that short custodial sentences do little to reduce the likelihood of reoffending". In its view, "extending the presumption against short custodial sentences to 12 months is intended to improve the chances of effective rehabilitation."1

According to Dr Sarah Armstrong of the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research (University of Glasgow), short prison sentences have been a problem since the 19th Century and a target for reform. In her view, it is difficult to assess the impact or efficacy of a single or small number of short sentences as most research is based on prisoners who have served multiple short sentences. 2

She also noted the Scottish Government's plans for imprisonment within the presumption ‘where no other method of dealing with the person is appropriate’. In her view, this is a common, if not the primary, rationale offered by judges for using such sentences precisely in the case of people who have already served short sentences. Hence, in her opinion, the people who judges believe are not ‘learning’ from these sentences – who also make up the group we know are damaged significantly by them – are also the ones most likely to continue receiving custodial sentences. 2

Dr Armstrong observed that people on short sentences were both harmed and helped during them. On the positive side, many accumulated educational qualificationsi, undertook courses, kept in touch with family and a small number came off drugs in prison. On the other hand, people also lost contact with families and children, lost hope, lost housing, and acquired drugs habits, or were encouraged onto opioid replacement in prison. In other words, in her view, ‘effectiveness’ is a complicated issue and the evidence shows both that it is possible that prison can be helpful and harmful within short periods of time. Moreover, she observed that these harms of confinement apply to longer serving prisoners, and simply removing short sentenced prisoners from the population does not affect this.2

Professor Cyrus Tata of the University of Strathclyde was sceptical that the Scottish Government's plans would be effective. He noted that in the same way that the current three-month presumption had made little net difference in part due to 'sentence inflation', so the longer period "is unlikely to make much difference". He did not think that the tests (section 17) were restrictive, requiring the sentencer only to satisfy an appropriateness test and to state a reason. He believed that—

... the extension to 12 months is unlikely to have much effect on sentencing practice: at best it is a reminder to sentencers of the existing injunction that imprisonment should be ‘a last resort’. Yet ironically, entrenching prison as ‘the last resort’ is the problem. 5

In their evidence to the Committee, the Edinburgh Bar Association queried whether the proposal for a presumption against short sentences is necessary. The Association stated that the current presumption against short sentences of up to 3 months "has not made a significant difference to sentencing practice." In relation to the current proposal, the Association said that it is already the case that Sheriffs are required to consider alternatives to custody. For example, the court cannot send an offender to prison if he/she has not previously served a custodial sentence without obtaining a Criminal Justice Social Work Report. That report will include comments and recommendations on the range of sentencing options available to the court. In their opinion, it is also fair to say that a Sheriff who has not considered an appropriate alternative to custody is likely to be subject to an appeal against sentence. The Association does not think it is necessary to place further obligation on the Judiciary to consider alternatives to custody.6

Furthermore, the Association said that the range of offences that are prosecuted on Summary Complaint is "incredibly wide". Examples at the less serious end include theft by shoplifting. At the other end of the scale, we regularly see cases of assault to injury, assault on children, sexual offences and concern in the supply of Class A drugs. Whilst the Bar Association recognised and agreed that prison should be a "last resort", some of the offences prosecuted at summary level were, in their view, very serious. A presumption against short sentences of less than 12 months would, in effect, mean a presumption against imprisonment in summary cases. The Edinburgh Bar Association has concerns about how this might impact on the prosecution of more serious offences mentioned above. In their view, one outcome might be that the Crown choose to proceed at solemn level. The Association believes that this entails a much longer procedural process ending with a trial by sheriff and jury and with associated increases in cost and time.6

The Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice (CYCJ) was more supportive in its submission. It noted that young people were more likely than the older generation to receive short sentences and that the presumption against a short sentence of less than 12 months would be of benefit to this cohort. The benefits of not being imprisoned would mean less disruption to a young person's employment history, access to a GP and medical care, and also to specialised services delivered in the community such as speech and language therapy.8

Prison population

In its Policy Note on the proposal, the Scottish Government argues that—

... the current rate of imprisonment in Scotland is too high, in particular when viewed against the rates in other comparable European countries. Extending the presumption is intended to reduce churn in the prison system, which will help to improve the quality of interventions with individuals who need to be in prison. Longer term, extending the presumption is expected to have some impact on prison population though this is primarily related to an indirect contribution to reducing reoffending. 1

The Scottish Government has estimated that a 20% reduction in the use of custodial sentences of 12 months or less would be likely to result in the imposition of an additional 1,300 community sentences a year.

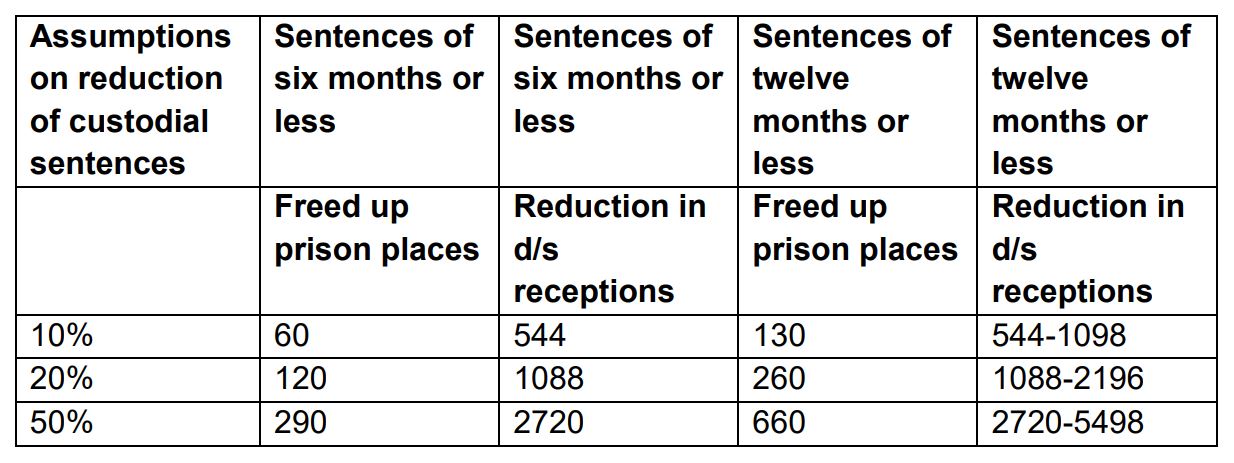

A number of submissions of evidence commented on this point. The SPS submission states that "it is not possible to predict with any certainty the extent to which the extension to the presumption will impact on the number of sentences under 12 months." SPS provided a table outlining a range of scenarios, as follows:

The key points made by the SPS are that impact will depend on the extent to which the judiciary follows the presumption with the most significant effect expected to be on receptions (‘churn’). However, reducing the number of short custodial sentences will, in its view, not necessarily translate into usable prison places as sentences which start and stop at different times over a year will not be coterminous. SPS also stated that any reduction in short term custodial sentences is likely to be offset by the ending of automatic releasei. The result, in its view, is likely to be a reconfigured population, rather than an overall reduction in numbers.

This is a view shared by the Chief Inspector of Prisons who argued that the proposed change will not have a substantial direct impact on prison numbers. However, in her view, "it will make some contribution to assisting with the rising prison population, and importantly will reduce the churn in the prison system."2

The Howard League Scotland (HLS) also argue that the current presumption against a sentence of less than 3 months has had no significant impact on the prison population and little or no impact on the sentencing practice of Sheriffs. HLS believes that the extension to 12 months will probably not by itself be enough to reduce the prison population, due to resistance against change in judicial sentencing practices. HLS cites research conducted by the Scottish Government which—

...showed that the PASS set at 3 months did not have a marked impact on sentencing decisions: many Sheriffs saw it as at best a ‘background factor’ in their decisions, and at worst irrelevant, or a demonstration of lack of trust in them. If such attitudes continue, and if the law requires only that Sheriffs not “pass a sentence of imprisonment for a term of [twelve] months or less on a person unless the court considers that no other method of dealing with the person is appropriate”, an extension of the PASS to twelve months might have little impact on sentencing practice.3

If the policy goal was to reduce the prison population, then a number of submissions made alternative suggestions on how this could be achieved. For example, some, such as that of Positive Prison? Positive Futures highlighted the increases caused by the change in the regime for Home Detention Curfews and the rise in convictions for historic sex offences4. Others, such as HLS, cited actions to reduce the number of women in prison, such as ensuring that specialist services for women are properly resourced in order to tackle the underlying causes of their offending behaviour.3

Finally, a number of submissions, such as that of Dr Sarah Armstrong, stressed that the issue of reforming remand was the key to reducing prison population, noting that around 20% of prisoners on any given day is in prison on remand, which is high relative to other countries in Europe, and a marked shift in practice in Scotland compared to 20 years ago.6 Dr Buchan and Dr Haddow noted in their submission that only around half of prisoners on remand will ultimately end up with a custodial sentence.7 This would suggest that approximately 10% of the prison population on any given day will not ultimately end up staying in prison.

Similarly, Dr Marguerite Schinkel's submission made an interesting observation that prisoners she had surveyed as part of her research "rarely made a distinction between remand and sentences". In their view, periods in prison on remand were experienced in much the same way, except with fewer privileges. Several of her contacts described how they were on remand repeatedly and often; being known as a ‘persistent offender’ to the police in their communities meant that they were often charged with crimes they had not committed.8

Reconviction rates

According to Dr Jamie Buchan and Dr Christine Haddow, prisoners released after a short sentence have higher reconviction rates than an alternative such as a Community Payback Order (CPO). They stated that CPOs have a reconviction rate 10% lower than imprisonment, and about 20-30% lower than the shortest prison sentences. In part they argue this is because community penalties focus on rehabilitation and desistance, and punish offenders without disrupting their housing, employment and family life. They also argue that CPOs are usually imposed for less serious crimes and on people who have fewer previous convictions. 1

The Scottish Government itself uses the issue of relative re-conviction rates as an argument for the current proposal. Its Policy Note for the SSI states that it wishes to extend the presumption against short periods of imprisonment "in light of the evidence that short-term prison sentences are not effective at rehabilitating individuals or reducing reoffending, especially when compared to community alternatives to custody (predominantly Community Payback Orders)."

The Scottish Sentencing Council also cited evidence from the Scottish Governmenti from 2018 that prison sentences of up to one year have higher one-year reconviction rates than community payback orders do. The Council warned, however, that care should be taken when comparing these figures, as those offenders assessed as suitable for community payback orders may be less likely to reoffend as a result of factors other than their index disposal. In its view, the extension of the presumption may lead to an increase in the use of community-based alternatives to custody, and possibly support an increase in rehabilitation and a reduction in reoffending. However, in their opinion, it cannot be assumed that offenders who would previously have been sentenced to imprisonment but are, after the extension of the presumption, sentenced to a community-based disposal will show similar reconviction rates to those currently disposed of with community sentences.2

Professor Cyrus Tata also commented on this issue. He said—

The use of three-month sentences was already going down—the Government has clearly noted that—well before the presumption was implemented. I am sceptical whether it will make much difference—the presumption against three-month sentences does not seem to have made much difference. I know that the Government has said that it has made a difference and that, in one of its news releases, it credited the presumption with a reduction in reconviction rates, but I think that that is a rather dodgy claim, for all sorts of reasons, not least because the term “conviction”, refers to criminal convictions and there has been an enormous growth in direct measures, such as out-of-court offers of settlement, fiscal fines and so on. I suggest that the committee should look at that quite carefully.

Justice Committee 04 June 2019 [Draft], Professor Tata, contrib. 86, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12165&c=2182621

Similarly, Dr Armstrong warned that comparisons of data between people serving different sentences often have not been matched to compare those with similar criminal justice histories. She argues that data on outcomes for those on community sentences comprises a substantial portion who have had little prison experience and/or are early in their criminal justice careers, whereas data on outcomes of those receiving short prison sentences over represents those with long criminal justice histories. As a result, in her opinion, it is difficult to compare a CPO with a prison sentence. It is therefore also difficult, she argues, to measure the ‘success’ of the proposed legal change, if enacted. She concludes that it will be important to assess the impact of the proposed legislation on community sentence practice – one might expect community sentences will become longer and with more conditions (thus increasing opportunities of breach and future custody).4

The Cabinet Secretary for Justice was firmly of the view, however, that short sentences do not work and that reconviction rates are higher than community-based alternatives. He said—

The evidence is clear that short periods of imprisonment do not work. They disrupt the things that are most likely to help to reduce offending, such as family relationships, housing, employment and access to healthcare and support. People who are released from short custodial sentences of 12 months or less are reconvicted nearly twice as often as those who received a community payback order.5

In his view, "the evidence for the progressive reform is absolutely overwhelming."5 He accepted, however, that "there are some issues relating to control factors because, depending on the seriousness of the offence, people might be more likely to get a custodial sentence than a community payback order."5

Up-tariffing

A suggested downside of a presumption against short sentences (both the current presumption and any extended one) was the possibility of ‘up-tariffing'. In their submission, Drs Buchan and Haddow noted that, in relation to the current presumption against short sentences of up to 3 months, there is some evidence of an unintended ‘up-tariffing’ – the phenomenon wherein system features, such as a presumption against short sentences, lead sentencers to decide to impose longer sentences than they otherwise would. Their submission states that the statistics clearly show that the fall in prison sentences of 3 months or less from about 2010 onwards was immediately followed by a rise in sentences of 6 months to 2 years.1

Similarly, Families Outside said that it has not noticed any substantial change in the prison population since the introduction of the current presumption against short sentences of up to three months. Rather, in their view, sentences appear to have been ‘up-tariffed’ to just over three months while use of custodial remand appears to have increased.

The Scottish Government accepts that there was some limited evidence of up-tariffing following the 3-month presumption being introduced. However, it argues that a 12-month presumption rather than a 6 month presumption "mitigates risk of up-tariffing as 12 months is the limit of summary powers". They state that "a 12-month presumption makes clear that all summary courts will give reasons if custody is the appropriate disposal." 2

In her evidence to the Committee, Dr Sarah Armstrong said she had changed her view on presumption because of this issue. She said—

... my thinking on the issue has evolved and I no longer support a presumption against short sentences. One of the reasons why I am sceptical of its effect is that the unilateral, blunt tool of a single sentencing change such as the presumption against three-month sentences initially bumped up the number of sentences of four months or longer. In other words, there was an initial up-tariffing effect, and it has not yet fully stabilised. We cannot tell you today the exact number of people in prison who are serving four months, three months or nine months, because the Prison Service has not published any validated prison statistics since 2013-14.

Justice Committee 04 June 2019 [Draft], Dr Armstrong, contrib. 84, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12165&c=2182619

'Alternatives' to custody

Many of those that gave evidence to the Committee were supportive of the use of ‘alternatives to custody’, with some submissions linking the potential effectiveness of the Scottish Government's proposed changes to the presumption against short sentences to the availability and resourcing of 'alternative' disposals, such as community-based orders. For example, Colin McConnell, of the Scottish Prison Service, said “it can be argued persuasively that prison is the right place for some people. However, the broader discussion that we are having is the right one: there are far more positives to keeping people out of custody and in well-resourced and well-structured community settings.”

Others strongly indicated that these disposals should not be seen as alternatives to custody and that that link in and of itself was part of the problem.

An example of the latter was the submission from Dr Sarah Armstrong. She argued that community sentences are themselves drivers of prison population expansion. This is because once a person has failed a community sentence, they are substantially more likely to receive a custodial sentence, regardless of crime or period of non-offending, if they ever come before a court again. Hence, in her view, community sentences are a significant and independent ‘cause’ of prison sentences.

Similarly, Professor Cyrus Tata suggested that community-based disposals should not be seen as direct 'alternatives' to custodial sentences and that the prevailing approach that ‘custody is a last resort’ ends up meaning that imprisonment becomes the default. He argues that—

When ‘alternatives to prison’ don’t seem to work or seem convincing, there is always prison. All other options have to prove themselves to be ‘appropriate’ and if they fail to do so, there is always prison. Prison never has to prove itself. While non-custodial sentences and social services seem so stretched, imprisonment, on the other hand, appears as the credible fail-safe.1

When appearing at the Committee, he added to these views—

We talk about the proposal as something bold and radical, but if you look at the formulation of section 17 of the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010, you will see that the proposal is a rehash of what we have been trying to do for the past 30 to 40 years.

The draft order does not use the language in the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 but, as ministers have said again, it basically says that prison is a last resort and that a custodial sentence should not be passed unless appropriate. Who passes a sentence that they think would be inappropriate? Who takes any serious decision in their life that they think is inappropriate?

Justice Committee 04 June 2019 [Draft], Professor Cyrus Tata (University of Strathclyde), contrib. 77, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12165&c=2182612

Professor Tata concluded that, "essentially, we are using the resource of prison in the same way that the Victorians did: as a poorhouse." In his view, "we use prison as the last line in the welfare state."3

Dr Buchan and Dr Haddow's submission called for "more radical leadership" and suggested going further than a presumption against short sentencing, suggesting a "presumption against imprisonment" except in the most serious and high-risk cases.4 Similarly, the Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice said that "ambitious change" is needed and that prison should only be used for those individuals who commit "serious offences or who are assessed as posing significant harm to others."5

East Ayrshire Health & Social Care Partnership was typical of those submissions making the case for community-based disposals as alternatives to imprisonment. The Partnership argued that—

Evidence from both research and practice indicates that community-based disposals are more effective than custody in reducing reoffending. A community disposal means that individuals can make retribution through unpaid work within their own local communities while working alongside a social worker to address some of the underlying issues which have led to involvement in offending behaviour. It also supports attendance at group work activities designed to challenge the attitudes and values which support ongoing involvement in offending behaviour. Individuals involved do not lose their homes, are not separated from their support networks within the community and are offered flexibility with appointments to accommodate their employment and family commitments. As a consequence, there is less disruption to the lives of the individuals’ employment, family and supports. All the above reduce the risk of an individual re-offending.

This is a view also shared by Sacro who point to the disadvantages of a short sentence in prison for the prisoner and their family. Sacro also make the point though that, from the victim's perspective, while some victims may not necessarily wish to see an offender receive a custodial sentence, "they will want reassurance that they will not be targeted in the future and that the offender is showing genuine remorse for their actions." In Sacro's view, "the provision of robust credible alternatives to custody are critical to maintaining the confidence of victims."6

Similarly, Victim Support Scotland (VSS) stated that the safety, protection and well-being of victims of crime is of paramount importance when considering presumption against short sentencing. It its view, sentencing should appropriately reflect the severity of the crime and that the impact of the crime on the victim should be heard and understood throughout the justice process. VSS concludes that custodial sentences should be imposed when there is a need to protect the public, including the victim, from harm.7

A number of submissions highlight the fact that 'alternatives' such as community-based disposals may also fail to work. Dr Armstrong's written evidence, for example, states that, each year, 3000-4000 people have a Community Payback Order (CPO) revoked. It should be noted that the successful completion rate for Community Payback Orders was 70% in 2017-18 according to data provided by Community Justice Scotland.8

Dr Schinkel's research into the criminal behaviour of young people commented on the views on community disposals of those she had surveyed. She stated that this cohort of people often had negative experiences of them, seeing them as a ‘tick-box exercise’, with little real support on offer. Importantly, for this group, ‘chances’ and community sentences had come when they had first started offending, which was too early for them. Her research showed that, at this point, this group "didn’t find imprisonment especially aversive, often finding a kind of community there with other young offenders and enjoyed offending with their peers."9

How punitive are the 'alternatives'?

A number of the submissions received and the witnesses who appeared before the Committee commented on the perception or otherwise of how punitive a community-based disposal is considered to be.

Community Justice Scotland said that "CPOs aren’t easy to complete". In its view, "people find them personally and practically challenging, but many report that engaging with elements including supervision and unpaid work is key in helping them move on from offending".1

Dr Graham and Professor McNeill said that—

In a modern, progressive society, prison must not be seen as the only or even the main form of punishment or censure, nor should community sentences be disregarded as ‘letting offenders off’ or a ‘soft justice’ response.2

In supplementary written evidence to the Committee, Dr Katrina Morrison of the Howard League Scotland provided some figures on the "payback" element within CPOs in Scotland. This showed that, in 2017/18, 17,834 CPOs were issued, and out of these, 13,299 had a requirement for unpaid work (75%). The average lengths for unpaid work was 125 hours per order and the average lengths for orders with supervision requirements was 15.4 months.3

Dr Morrison noted that the intention of CPOs, as first articulated by the Prisons Commission, is not that CPOs must always have an unpaid work requirement. The Prison Commission has argued that we need to take a holistic view of ‘paying back’. In its view, working towards rehabilitation (through supervision and programmes) still ‘pays back’ to communities and victims. In her view, therefore, the claim that CPOs which do not have an unpaid work requirement involve no ‘paying back’ are incorrect.3

She also stated that "the argument that CPOs are not ‘punishment’, or equate to being ‘let off’ completely misses their penal nature". In her view, community penalties (with or without unpaid work) are experienced as a punishment by those subject to them. Crucially, in her opinion, this extends beyond periods of unpaid work or supervisory meetings to affect all of life, an experience recently conceptualised as a ‘pervasive punishment'.3

Island and remote, rural issues

Alternatives to custody should, in principle, be available as a disposal to a sentencer no matter where they are in the country. In evidence to the Committee, we heard examples of variations in practice. In part, these variations may be due to the profile of those appearing in court, making such disposals more or less likely to be used. However, we also heard that the variations may be caused by the sentencing practice of the sentencer which in part was due to the availability of suitable community-based sentences, particularly in island and remote, rural locations.

Positive Prisons? Positive Futures, for example, cited research by Javier Velasques Valenzuela at the University of Glasgow that showed that "judges in some parts of the country send people to prison because they do not have the right provision available in the community."1

In response to a comment that some alternatives to custody programmes required a certain number of people before they can be provided, and that this might be more difficult to achieve in island or remote or rural locations, the Cabinet Secretary for Justice accepted that there were "nuances" in these communities. He also said there were issues around community alternatives, such as the stigma that is associated with them. However, he thought the government would be able to meet the challenges of those nuances. He said he did "not want those in island communities to be disproportionately negatively affected" and that he wanted them to "have the full range of opportunities for community sentences that anybody else would have".2

Resourcing

Many of those giving evidence to the Committee commented on the need to resource 'alternatives to custody' if the changes to the presumption against short sentences leads sentencers to look to use community-based disposals instead.

The Scottish Government's Final Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment states that—

Scottish Ministers allocate around £100 million in funding to local authorities to deliver community sentences, support rehabilitation and reduce re-offending. This funding includes an additional £4 million investment in community sentences which was introduced in 2016/17 and continued in 2017/18, helping to support local authorities to deliver robust community sentences. This was increased to £5.5 million in the 2018/19 budget in anticipation of the extension to the presumption and additional funding may be necessary for 2019/20.

The Scottish Government also argues that it continues to invest in third sector services that support criminal justice social work and community justice partners working together, to reduce reoffending. In 2018-19, this investment totalled over £11.6 million including support for mentoring, Apex, SACRO, the 218 Centre for women, Venture Trust, Turning Point Scotland, Families Outside and Prison Visitor Centres. 1

XXX Insert Level 4 Table

The Government's scenario-based financial impact assessment indicates that, for example, assuming that 20% of custodial sentences between 3 months and 12 months would be converted to community sentences, and excluding those sentences covered by the existing presumption, then around 1,300 additional community sentences would be anticipated. The unit cost of a Community Payback Order is an average of £1,771 which equates to around £2.5 million. The approximate costs of keeping a prisoner in the SPS estate is around £35,000 per year.i The Government's Impact Assessment states that "the budget for 2019/20 with an additional £1.5 million provided specifically to assist with the implementation of the presumption against short sentences."1

Local authority representative body COSLA submission states that—

It will be important that the extension of PASS is adequately funded to enable local authority criminal justice social work services to effectively meet the needs of individual offenders to reduce the risk of re-offending. If CPOs are not sufficiently funded the resulting ineffectiveness could undermine the confidence of courts and communities in the efficacy of community-based sentencing. In addition, it could undermine the confidence of victims and their families that justice is being delivered and that offenders are being properly managed and held fully to account for their actions.3

Its submission was typical of those received from individual local authorities who all expressed views on the need for adequate resourcing of bodies involved in delivering community-based sentences. For example, the City of Edinburgh Council said that whilst it was difficult to gauge exact numbers, the proposals "would almost certainly result in an increase in community disposals such as Community Payback Orders (with or without unpaid work) and in Drug Treatment and Testing Orders."4

Falkirk Council Criminal Justice's submission disputed the Scottish Government's estimates of the impact on increased use of CPOs. The Scottish Government's anticipated increase in CPOs of 7.5% if PASS is extended to 12 months would result in approximately 48 new orders per annum in the Falkirk area. However, figures held by Falkirk Criminal Justice indicated that since 2011, on average, 126 custodial sentences of 12 months or less are imposed each year. The Council concluded that it was "a fair assumption to therefore make that if the majority of these [126 custodial] cases were to become community sentences, the increase would be higher than the 7.5% figure being anticipated by Scottish Government."5

The Council said that, based on both the CPO figures and the short term sentence figures, to properly resource such an increase in numbers, would require between 2 to 4 additional case managers at costs of approximately £50,000 per worker per annum for salaries alone.5

In his evidence to the Committee, James Maybee representing Social Work Scotland highlighted what, in his view, was a disparity in funding of criminal justice social work compared to prisons since CPOs were brought in in 2011. He said—

Community payback orders were introduced in 2011 and, since then, Scottish Prison Service funding has increased by about 8.9 per cent, whereas the core grant for criminal justice social work has remained static at £86.5 million per annum—if we were to get an extra 8.9 per cent, it would raise the grant by about £7.6 million or £7.7 million. That is indicative of the fact that resources have been put into one part of the system but have not been injected into the other part.

As we said in the Social Work Scotland submission, the Scottish Government has made some resources available to assist criminal justice social work to prepare for the presumption against short-term sentences, but we are playing catch-up, and many of those resources are going into trying to maintain the status quo, rather than building new capacity.

Justice Committee 04 June 2019 [Draft], James Maybee (Highland Council and Social Work Scotland), contrib. 5, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12165&c=2182540

SPS dispute these figures, with its chief executive telling the Committee that, over the past 5 years, SPS has been subjected to " either flat-cash settlements or, in fact, cash cuts."8

Mr Maybee also warned that there could be issues, in particular in relation to women prisoners. He noted that, in 2017-18, 90 per cent of the custodial sentences received by women were for less than 12 months. His view was that if some of those individuals find their way on to community payback—which he very much hoped that they will—they will bring very complex issues with them. Therefore, in his view, there was a need to ensure that there were the resources to deliver the presumption against short sentences, if it is extended.9

Other groups also commented on the issue of resources. The Law Society of Scotland stated that the proposal simply will “not work unless there is significant investment in community-based disposals and an opportunity for rehabilitation in the community."10 Similarly, the Howard League Scotland said—

We must avoid a situation in which courts are discouraged from imposing custodial sentences, but effective community-based alternatives are unavailable. A significant increase in resources for community justice must go hand-in-hand with an extension of the PASS. 11

Two areas potentially most affected financial by an increase in community sentences are those of criminal justice social work and also the third/voluntary sector who work with prisoners, their families or victims and their families.

Social Work Scotland (SWS) estimated that, for a local authority with around 800 new CPOs each year, the Scottish Government's estimated of a 7.5% increase in the use of CPOs after the presumption is applied would equate to an additional 60 orders. SWS estimated meeting this demand would require at least 2 new case managers costing approximately £100,000 p.a. for salaries alone (including on-costs). SWS also said there would be a “ripple effect with cost implications for other statutory sector service providers, for example, drug and alcohol interventions; and, importantly, for Third Sector agencies that currently provide a range of interventions, including drug and alcohol, employability and other interventions."12

The Criminal Justice Voluntary Sector Forum (CJVSF) said that any increase in the number of people serving community sentences could therefore have a considerable impact on the voluntary sector. CJVSF members would welcome an ongoing review of the impact any extension has on voluntary sector provision in future. The Forum noted that voluntary sector organisations are increasingly vulnerable in the current funding climate and a number of organisations have already seen considerable cuts or decommissioning of services as local authority budgets get tighter and services are taken “in house”.13

Families Outside warned that for a presumption against short sentences (PASS) to be effective, community-based measures must be available to reduce current and future risk. In its view, this will include measures, such as community payback orders or electronic tagging, to recognise that an offence was committed. However, they must also, in its opinion, include measures to address the practical issues that contribute to offending such as mental ill health, substance misuse, unstable housing, poverty and lack of income, and breakdown in relationships. Families Outside stated that "this is where the financial impact of the extension of PASS lies: such measures must be readily available throughout Scotland and focus on support as well as on monitoring and surveillance".14

In his evidence to the Committee, Colin McConnell, chief executive of the SPS, warned that alternatives to imprisonment should not be seen as a "cheaper option". He said—

If, as I hope it does, such provision [presumption against short sentences] is to become part of our justice infrastructure, we have seen that the way forward will require substantial financial and other resources, and it will require skills and competences right across the system—in the statutory services and, for that matter, in the third and voluntary sectors. Over time, that will probably cause us to spend a lot more on the justice system, not a lot less, so it is important that we do not see it as a way of reducing the cost of the system. It will clearly require significant investment over a sustained period.

Justice Committee 04 June 2019 [Draft], Colin McConnell, contrib. 29, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12165&c=2182564

Outwith the third/voluntary sector, a number of other bodies comment on the financial/resource impact on their services. For example, Police Scotland said, in its view, “The use of CPOs and fines as an alternative to custodial sentence will have an impact upon local policing provision especially in relation to RSOs subject to SONR. Non-compliance with CPOs may result in arrest warrants which will require to be executed by police. The number of Means Enquiry Warrants generated as a result of non-payment of fines will inevitably increase if this is adopted as an alternative sentence placing a further burden upon local policing and impact upon the ability to deliver frontline services.”

The Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service told the Committee that the proposed change to the presumption is likely to lead to an increase in the number of requests for Criminal Justice Social Work Reports. This in turn may mean that the court would have to adjourn court hearings for such reports and this will impact on court time and associated staff and accommodation resources.16

The Scottish Legal Aid Board also reported an expected increase in costs. The Board explained that criminal legal assistance in the form of Assistance by Way of Representation (ABWOR) is available for proceedings in relation to breaching, varying or revoking court-imposed community sentences such as Community Payback orders. Therefore, an increase in the number of community-based sentences imposed might also see a similar increase in the number of proceedings held in relation to breaches, variations and revocation of these orders. In 2017/18, SLAB received 9,689 ABWOR applications for these proceedings, with an average cost of £283 inc VAT. Therefore, an increase of 7.5% of these cases (the Scottish Government's own estimate) would mean an extra 727 applications at an additional cost of £205,741.17

The Cabinet Secretary accepted in his evidence to the Committee that there is strong support for extending the presumption "provided that there are community-based interventions that are appropriate, resourced and effective."18

He also accepted that there were issues around the funding of the voluntary/third sector and committed to exploring the use of multi-annual budgets for such bodies operating in the criminal justice system.18

Local government funding formula

As outlined above, a number of individual local authorities and also COSLA expressed general views on the need for their services to be resourced if this proposal is to be successful. A number also called for their to be changes to the current funding model used in this area.

For example, East Dunbartonshire Criminal Justice argued that the proposed changes “would require additional funding through section 27i grant allocation”. The Council was of the view that—1

As the grant allocation through section 27 is primarily calculated using workload, inequity may result through the proposed extension. Community sentences numbers in larger local authorities may increase disproportionately to those in smaller local authorities, thus resulting in a lower percentage of the overall funding pot being allocated to smaller authorities.

The Council said that the settlement and distribution group would be required to address the allocation of the Justice Budget to increase the quantum of the fund for section 27 to reflect the increase in workload. They also said that consideration should also be given to the transfer of resources from the SPS to fund the additional workload.

Similarly, the Clackmannanshire Community Justice Partnership recommended that the modelling of Section 27 funding for justice social work is revised in order to account for a vulnerability index based on the profile of clients. 2

The Cabinet Secretary told the Committee that the Scottish Government had increased section 27 ring-fenced funding for criminal justice social work by 7.3% at a time when the numbers of CPOs had fallen by 8.3%. He therefore had "great confidence that the system can cope with the presumption."3

Scope for reallocation of resources

In her evidence to the Committee, Dr Sarah Armstrong questioned whether, even if some savings were made by placing people on a community-based sentence rather than going to prison, actual savings in the prison budget would be made and be available for transfer to other services. She said——

... it would be overly simplistic to consider the issue in terms of the comparative costs of community service versus prison—there are a lot more costs to think about. I do not want to repeat anything that she said, but I point to my speculation, which is untested, that there would be increased associated costs.

Colin McConnell suggested that there would be 500 fewer people in prison. I am not sure about that number, but even if that were the case, I have not heard him say that he would close a prison of 500 beds; without the closure of a prison of that size, the significant costs that are associated with a prison would still be incurred.

The costs that are associated with community sentences include not just running them but managing their breach. In my written submission, I made the point that community sentences are themselves a driver of prison population growth, so that probably needs to be modelled and analysed by an economist.

Justice Committee 04 June 2019 [Draft], Dr Sarah Armstrong (University of Glasgow), contrib. 76, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12165&c=2182611

The Scottish Government also acknowledges this point. Its Policy Note states that the effects of increasing the length of the presumption will be in part dependent on the impact on sentencing behaviour. Analysis conducted by the Scottish Government's Analytical Services Division suggests that a 20% reduction in the use of custodial sentences of 12 months or less would be likely to result in the imposition of an additional 1,300 community sentences a year. The government estimates suggest that the additional resource requirement created by this increase will be in the region of £2.5 million p.a. The government states that "savings to Scottish Prison Service are not expected to be releasable but are expected to enhance support in prisons as officers spend less time dealing with receptions."

Other types of alternative to prison sentences

Most of the evidence in the previous section on alternatives to custody relates to community-based disposals such as Community Payback Orders, Restriction of Liberty Orders etc. However, a small number of submissions suggested other alternatives to the proposal to change the presumption against short sentences.

Dr Graham and Professor McNeill highlighted the role that problem-solving courts can play, as well as mentoring, employability and training initiatives, restorative justice, and compensation to victims.

They cite the example of the Aberdeen problem-solving approach (PSA) which works with people with complex needs and prolific offence histories, assessed as high risk of reoffending. It uses structured deferred sentences (up to 6 months) with intensive social work supervision and support from community justice partners. Dr Graham and Professor McNeil noted that a research review of the PSA found positive emerging outcomes: reduced reoffending, reduced alcohol and drug use, improved housing situations, improved mental health and well-being, and improved social skills and relationships.1

In her evidence to the Committee, Laura Hoskins of Community Justice Scotland said that evidence from Lanarkshire courts were that structured deferred sentencesi were "working well." Lord Turnbull of the Scottish Sentencing Council also referred to the use of such sentences in Hamilton sheriff court which he said was "proceeding well", with fewer breaches of CPOs2.

Professor Tata offered a longer-term proposal in his evidence to the Committee. He said—

... we should have a principle stating who should not normally be imprisoned, or what cases should not normally lead to a prison sentence, and that we have a date by which we ensure that there is a transfer of resources. Unless there is such a transfer, I do not think that the proposed presumption, whether it be against sentences of 12 months or whatever, will make much difference because—quite rightly—the sheriffs will, by and large, say that imprisonment is still appropriate because there is nothing else.

Justice Committee 04 June 2019 [Draft], Professor Cyrus Tata (University of Strathclyde), contrib. 77, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12165&c=2182612

Assessing risk and sentencing guidelines

The assessment of risk during the consideration by a sentencer on whether to send someone to prison on a short sentence or to use an alternative community-based disposal or some other form of conviction was raised in a number of submissions.

Victim Support Scotland (VSS) said that it would want to see risk assessment and information provided to the court on risk posed by perpetrators to the victim. VSS was keen that the courts should take into account the severity and type of crime alongside the harm caused when deciding on the appropriateness of passing a community sentence or otherwise. VSS also said that guidance should be provided to the courts with clear direction on what factors should be taken into account in sentencing.1 This was a view shared by the Victims’ Organisation Collaboration Forum Scotland.2

The Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice (CYCJ) stated that there may be a need to go beyond ensuring that the court is satisfied no other option would be appropriate and recording the reasons for this. The CYCJ suggested that the culpability of the person, harm caused, and assessed risk which that individual poses and whether such risk can be managed in the community should be included as circumstances to which a sentencing judge should have regard.3

Scottish Women's Aid said that further work needed to be carried out in addition to the recently re-published revised practice guidance on CPOs. It said that firm commitments were needed on risk assessment and information provided to the court on the risk posed by perpetrators including information from the victim. Scottish Women's Aid said that coercive and controlling behaviours are an important indicator for lethality in domestic abuse cases, and therefore that this risk assessment must be sensitive to coercive control, which most risk assessment tools in use are not.4

In her evidence to the Committee, Kate Wallace of Victim Support Scotland stressed the importance of maintaining public confidence in alternatives to custody. She told the Committee that—

... victims will receive certain support in the event of a custodial sentence being given, but that support will not be provided if a community payback order is given. If we had information about whether people are engaging with the orders as well as about breaches and successful completions, that would help address certain public safety concerns and some of the concerns that victims have expressed.

Justice Committee 04 June 2019 [Draft], Kate Wallace, contrib. 68, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12165&c=2182603

Judicial and other training

Some of the submissions received linked issues of sentencing guidance and risk assessment by sentencers to aspects of judicial training and training for others. For example, the Law Society of Scotland said that the changes, if agreed to, would require all judges, JPs and sheriffs to receive training because they are the decision-makers following any conviction for imposing sentence. The Society also said that solicitors undertaking defence work may also need training.1

The Howard League Scotland said that it must be made clear to sentencers where properly resourced community-based disposals are available, and the presumption should be emphasised in mandatory training. The Howard League said that written explanation of reasons behind sentences of less than 12 months should be more than cursory. They also said that the extended PASS should be monitored both to ensure there is no up-tariffing, and for its effect on the overall prison population.2

The Cabinet Secretary accepted that there can be variation in the use of community-based alternatives, which can be due, in part, to awareness and in part trust. He said—

We must ensure that the judiciary has confidence in the community justice landscape. There is clearly some evidence that sheriffs in some localities need that confidence and need to be persuaded about the merits of community-based alternatives and their robustness.3

Views on alternative sentencing periods, an outright ban on short sentences, the exclusion of offences and discounting

Should a different time period than the 12-months proposed be used?

One of the questions posed by the Committee in its call for evidence was whether a figure other than 12 months would be more appropriate. A number of members of the academic community who gave evidence to the Committee said that the figure of 12-months was "arbitrary" and there was no real evidence for having a threshold of 3, 6, 9 or 12 months.i

A number of submissions, such as those from Clackmannanshire Community Justice Partnership, East Dunbartonshire Criminal Justice, the Prison Reform Trust and others expressed support for the proposal to extend the presumption to sentences of 12 months or less. Many of these respondents called for this to be kept under review and for the impact to be monitored.

The Law Society of Scotland did not take this view. It said that it tended "to consider that any increase in the presumption against short sentences should be restricted to 6 months and then considered further."1

The Cabinet Secretary was not in favour of such a move. He said that "the 12-month period was chosen for good and legitimate reasons, to avoid the issues around up-tariffing because of summary sentencing limits."2

Outright ban rather than a presumption against?

The Committee also asked for views on whether an outright ban was preferable rather than a presumption against short sentences.

The Scottish Sentencing Council was not in favour of an outright ban. It said that "a ban would be unhelpful". First, it would limit judicial discretion and there may be circumstances where, in the opinion of the court (which is in by far the best position to consider the unique facts of each case), a short custodial sentence is the most appropriate disposal. This may apply where, for example, an offender is found to have failed to comply with a community payback order, and the court is satisfied that the order should be revoked and a sentence of imprisonment imposed. Second, the Council warned that a ban might have the unintended consequence of leading to longer sentences being imposed (“up-tariffing”), where a court is of the view that a custodial sentence is the only effective and appropriate sentence which can be imposed.1

Similarly, the Law Society of Scotland said that there should not be any outright ban on any sentence that removes the judge's discretion on sentencing to what they feel is appropriate in the circumstances. The Society is of the view that "if any ban on sentencing to a particular length was envisaged, this should be undertaken by primary legislation as it represents substantial legislative change."2

Others, including SPS, shared the view that decisions of this type should be left to the judiciary. Colin McConnell said that—3

The evidence on having a presumption against three-month sentences is compelling, but there is an argument for leaving the judiciary unshackled on that basis. Judges should be trusted and must be free to make decisions based on the individual who is before them. Even with a presumption against short sentences in place, I expect that in the future we will still have people with us who are serving sentences of less than 12 months.

Justice Committee 04 June 2019 [Draft], Colin McConnell, contrib. 40, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12165&c=2182575

In his evidence, the Cabinet Secretary said that he did not consider a ban and does not think that a ban is the "right way to go". He said that "a ban very much restricts the judiciary, and the judiciary is best placed to decide who should be given a short custodial sentence and who should be diverted away from custody".5

Should certain offences be excluded from the provision?

In its evidence, the Scottish Sentencing Council noted that the 12-month presumption will apply to almost any custodial sentence imposed at summary level as well as those at the lower end of the solemn level, which will encompass a much wider spectrum of offending behaviour, including some offences which, in its view, "may be considered as notably more serious”.

Lord Turnbull gave examples of the kind of offences that will be covered by a move to increase the presumption to 12-months. He noted that offences of assaulting or impeding police officers or providers of emergency services will be caught by the presumption, because offences under the Emergency Workers (Scotland) Act 2005 and the Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Act 2012 carry maximum sentences of 12 months’ imprisonment.1

In their evidence, Scottish Women's Aid said that there needed to be a comprehensive plan, or even a significant interest in defining the problem, on the implementation and monitoring of community disposals in domestic abuse cases. Until such a plan has been developed, Scottish Women's Aid said that could not see how more community disposals for domestic abuse cases can be judged safe for women and children.

Scottish Women's Aid also noted that the newly commenced “course of conduct” offence, under section 1 of the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018, allows for, on summary conviction, imposition of imprisonment for a term not exceeding 12 months. Scottish Women's Aid were concerned that the extension of the presumption would deter use of this important sentencing option, despite the Scottish Government's reassurance that this is a presumption and not an outright ban.

Scottish Women's Aid noted that cases involving domestic abuse account for at least 20% of both police and court business. Scottish Women's Aid is not persuaded that current practice around the imposition, implementation, and monitoring of community disposals is safe in relation to cases of domestic abuse, and it considers that "there is significant risk that some women and children will be endangered by extension of presumption in domestic abuse cases." Therefore, Scottish Women's Aid concluded that "cases involving domestic abuse should be exempt from the extension of the presumption until implementation of community disposals in domestic abuse cases is demonstrated to be safe."2

Speaking at the Committee, the Cabinet Secretary said that he did not agree to an exemption for domestic abuse cases. He said decisions should be left to the discretion of sheriffs.3

In its evidence, Scotland's Campaign against Irresponsible Drivers (SCID) said that the presumption against short sentences of less that 12 months "must focus on low level offenders" and those "crimes where no physical or mental harm has been caused to victims."4

Police Scotland noted that in respect of Registered Sex Offenders (RSOs), very few RSOs get sentences of less than 3 months so "there has been no great impact experienced thus far, with 6 months being the lowest imprisonment period for RSOs and is regularly applied."

The police highlighted that the Sexual Offences Act 2003 states that those offenders sentenced to imprisonment of 6 months or less will be the subject of sex offender notification requirements (SONR) for 7 years and those sentenced to imprisonment for more than 6 months but less than 30 months would be subject for 10 years. In Police Scotland's view, the change to a presumption against sentences of less than 12 months would probably impact on the number of RSOs being the subject of an SONR for 7 or 10 years.

Police Scotland said this would have a knock-on effect for overall RSO numbers as there would be a reduction in the number being managed for longer periods of time. Police Scotland explained that although Sheriffs would still have the ability to impose a short sentence if deemed necessary, in effect there would be very few RSOs subject to SONR for a 7-year period and a reduction in those subject to a 10-year period. The police's view was that, while this may be seen as a positive it could also be considered negatively as RSOs would be managed as convicted offenders for shorter periods of time.

Discounting

The preceding section of this report sets out views expressed to the Committee on the types of offences that would now be covered by an extension of the presumption to sentences of up to 12 months. In theory, through the application of a discount on a sentence, longer time periods of up to 18 months could fall into the scope of this presumption.

The Scottish Sentencing Council commented on the issue of discounting of sentences. It said that there may also be occasions where the extended presumption will apply to solemn cases which attract a sentence longer than 12 months’ imprisonment. For example, a court could regard a headline sentence of 18 months’ imprisonment as appropriate for a particular case, but then apply a discount of up to one third because of an early guilty plea, potentially bringing it down to 12 months, and thus within the scope of the presumption. The Council said it had undertaken some initial investigations into this, which indicate that "for solemn charges in the sheriff court in which a custodial sentence was imposed in 2017-18, around 1 in 10 received a headline sentence of over 12 months which was subsequently discounted to 12 months or less."1

Lord Turnbull explained that some offences that might carry a sentence of 10 to 12 months as a consequence of a discount being applied could include causing death by careless driving; causing death while driving while disqualified; possession of indecent photographs of children and, possibly, the distribution of lower category images; possession of offensive knives and weapons; assaults; and, perhaps, some drug supply charges, sexual offence charges and charges of multiple housebreaking.2

Lord Turnbull explained, however, that the actual impact of discounting will depend on the decisions of sentencers in those cases. He explained, using a hypothetical example—

... if the sentencer concludes that the sentence ought to be around 15 months’ imprisonment and then, in the light of the early plea, discounts that sentence by one third to bring it down to 10 months, they will have to apply their mind to the question of whether, despite the presumption, imprisonment remains the only appropriate sentence. We will have to wait and see what individual sentencers decide in that situation. I would have thought that, if a sentencer had concluded that a sentence in the region of 15 months was the only appropriate sentence, they would be unlikely to change their mind once they applied the discount and realised that they had to take account of the presumption. Yes, they would think again, but I am not sure that they would come to a different conclusion.

Justice Committee 04 June 2019 [Draft], Lord Turnbull, contrib. 139, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12165&c=2182674

Conclusions and recommendation