Health and Sport Committee

Preventative Action and Public Health

Background

Following our business planning event after the 2016 election we agreed on 13 September our strategic plan for the session. The plan specified:

In all our actions our overriding aim is to improve the health of the people of Scotland

Underpinning that aim our plan states: To meet the above we will test all activity we scrutinise against the following aspects:

The impact it has on health inequality;

The extent to which it has a prevention focus;

Long term cost effectiveness and efficiency; and

The implications of the UK’s EU exit.

Our strategic plan also provided an indication of how we will take our work forward:

We will direct our focus on the outcomes being achieved and those proposed, and examine and consider the identification and measurement of added value.i

It was against this background we determined, in December 2016, to look at holding an inquiry into the preventative work delivered nationally to support good public health outcomes. This was a timely inquiry given the integration of health and social care through the introduction of the Integrated Joint Boards across Scotland. The inquiry also coincides with the development of a new national public health body for Scotland as well as a new National Outcomes Framework.

We agreed to initially hear from experts in the field and then seek a Parliamentary debate to provide all members with an opportunity to contribute. In this way we sought to be inclusive of Parliament, recognising as our then convener said when opening the debate:

the preventative health agenda is a cross-cutting issue that involves education, justice, transport, housing, the environment, social security, culture and many other areas of government

Christie Commission 2011

In undertaking this inquiry we were building on the 2011 Christie Commission report on the future delivery of Public Services in Scotland. The Christie Commission identified prevention as one of its four key “pillars”.

The Commission noted it was imperative public services adopt a much more preventative approach to address persistent problems of multiple negative outcomes and inequalities being faced by far too many.

The Commission did not believe there was a magic solution to the problem of resources being tied up to deal with short-term problems to the exclusion of efforts to improve outcomes in the longer term. They saw no alternative but to switch to preventative action to avoid what they termed “failure demand” swamping the capacity of our public services to achieve outcomes.

it is instructive that one of the hopes of Aneurin Bevan when the NHS was founded was that as people's health improved the cost of the service would fall. In reality, people demanded and continue to demand more and the cost of these services rose and continues to rise.

Finance Committee 2011

Also in 2011, the Finance Committee of this Parliament examined the concept of preventative spending in-depth hearing “remarkably strong evidence about the benefits that such an approach could deliver” They stated “there will have to be a shift from reacting to crisis, to a greater focus on prevention and early intervention.” That Committee welcomed the Government emphasis on preventative action as being “integral to the approach to government in Scotland and delivering the outcomes set out in the National Performance Framework.”

Scottish Government's 2020 vision

In September 2011, in recognition of the challenges facing health and social care, the Scottish Government set out an ambitious vision to enable everyone to live longer, healthier lives at home or in a homely setting by 2020. This vision aims to help shape the future of healthcare in Scotland in the face of changing demographics and increasing demand for health services. Central to the vision is a healthcare system with integrated health and social care, and a focus on prevention, anticipation and supported self-management.

Included among the main principles underpinning the vision, particularly in relation to shifting more care and support into the community, are those:

focusing on prevention, anticipation, supported self-management and person-centred care;

integrating adult health and social care; and

reducing health inequalities by targeting resources in the most deprived areas

Integration of health and social care

Health and social care services in Scotland have been reformed with NHS boards and local authorities required, as a minimum, to combine their budgets for adult social care, adult primary healthcare and aspects of adult secondary healthcare. The new integration authorities coordinate health and care services and commission NHS boards and local authorities to deliver services in line with a local strategic plan. The intention is that this will lead to a change in how services are provided, with a greater emphasis on preventative services and allowing people to receive care and support in their home or local community, rather than being admitted to hospital.

Our Inquiry

We agreed we needed to understand what exactly preventative spend and preventative healthcare are. This became the first part of our inquiry. Both terms are vague and conceptual, making it possible to argue that all public expenditure is preventative. The lack of a clear definition we were told by the University of Stirling, in their submission to us, also allowed all public services to retrospectively fit their services under these headings.

We also noted difficulties attributing outcomes to any one policy. Audit Scotland in their report “Changing Models of Care” urged efforts to address the gap in cost information and to evidence the impact of new models (of care).

Our inquiry commenced by seeking views on four questions, upon which we received 67 responses:

Which areas of preventative spending/ the preventative agenda would it be most useful for the Health and Sport Committee to investigate?

How can health boards and integration authorities overcome the (financial and political) pressures that lead to reactive spending/ a focus on fulfilling only statutory duties and targets, to initiate and maintain preventative spend?

How could spend that is deemed to be preventative be identified and tracked more effectively? What is required in terms of data, evidence and evaluation to test interventions for producing ‘best value for money’?

How can the shift of spending from reactive/acute services to primary/preventative services be speeded up and/or incentivised?

Round Table

In March 2017 we explored the above issues with academics, a group of expert practitioners in the public health field, and the integrated joint boards.

We are grateful to the many people and bodies who have assisted us and participated in this inquiry. Without their input, their knowledge, their views, their calls to arms and their challenges it would have been impossible for us to undertake this, or indeed any other inquiry.

Our Inquiry: Part 1

This chapter summarises the main issues which arose from our call for evidence and the ensuing round table we held. Following the round table evidence, the Parliament held a plenary debate on 18 April 2017 which agreed our motion:

"That the Parliament recognises the importance of the work of the Health and Sport Committee in its inquiry into the preventative health agenda; welcomes its examination of policies and actions, which prioritise and build in actions to reduce demand on health services in the longer term following on the work of the Christie Commission on the Future Delivery of Public Services, and the Finance Committee in 2010; notes that the cross-cutting nature of health inequalities also encompasses housing, education, justice, transport, the environment and other portfolios, and welcomes attempts to meet the growing demand for public services by preventing health problems before they occur by early interventions and by tackling causes as well as their effects".

Health inequalities

We were made aware throughout our inquiry of the impact from health inequalities. Our predecessor Committee notedi;

The divisions in health expectations and outcomes between the most and least wealthy, powerful, educated and housed have existed and been acknowledged for a long time, and are well-documented.

Like our predecessor Committee we are aware that reducing the differences between those with the best outcomes and those with the poorest has been a priority for every Scottish administration since devolution. Like them we observe health inequalities remain persistently wide.

Preventative Agenda defined?

As part of the initial stage of our inquiry we sought to identify whether there existed an agreed definition of “preventative spend”. This proved elusive with numerous suggestions offered, ranging from the World Health Organisation (WHO) to a range of academics and organisations.

More generally the Scottish Government through its National Performance Framework and related National Outcomes reports on a preventative focus, based on outcomes, greater integration of services, investment in workforce development and improving performance through encouraging innovation.

The Finance Committee in their 2011 report had asked the Scottish Government for a “robust and measurable definition of preventative spending that could be used across the public sector”.i We sought clarification from the Cabinet Secretary as to the definition favoured by the Scottish Government.

On 18 April 2017, the Cabinet Secretary said "Our preventative approaches are many and diverse, and any definition must give us flexibility to address different challenges across a range of policy and delivery contexts. We therefore believe that prevention should be defined in broad terms as activity that maintains positive outcomes and breaks cycles of negative outcomes, helping to tackle persistent inequalities for people and communities.”

Traditionally, prevention is defined under the following three levels:

Primary investment to stop a problem arising in the first place and/or modifying the social or physical environment. E.g. mass vaccination, fortifying foods, fluoride in drinking water. The focus is on the whole population. Within this category research work should be a relevant area.

Secondary to identify a problem at a very early stage to minimise harm. E.g. those at risk of obesity. The focus being on at-risk groups.

Tertiary to identify and to stop a problem becoming worse. E.g. those already obese and have Type 2 Diabetes. Ultimately leading to amputation and blindness amongst other impacts.

We learnt about the potential impact of “counterfactuals” (see paragraph 40) which is establishing the assessment of what would have happened had the preventative intervention not occurred. We were introduced to the concept of the "false dichotomy"i when considering the relative merits of addressing social determinants (for example increasing income or improving housing) or more specific interventions (for example on obesity or diabetes).

We have come to the conclusion it is easy to over-complicate the issue in a search for an all-encompassing and inclusive definition. Our specific interest in the preventative agenda was summed up by Professor Gerry McCartney (NHS Health Scotland) who suggested the following working definition:

Spending public money now with the intention of reducing public spending on negative outcomes in the future

It is the above description of preventative spend that we adopt throughout our report.

Actions making a difference

We heard about the need not only to postpone mortality and increase life expectancy but also to compress morbidity. Reducing the time people spend in ill-health will generate savings. Compressing the length of time over which people need health and social care services, keeping them healthier for longer, will inevitably make the system more sustainable.

Witnesses suggested public services require a shift in mindset. We heard that moving from a siloed approach to work is providing opportunities to design new interventions. Seeing the bigger picture, looking more holistically and working better together is allowing root causes to be tackled.

We heard various examples from Midlothian through the integration of health and social care. For example, on falls they work with the Scottish Fire and Rescue service whose staff, when undertaking fire assessments, also do falls checks. We also heard about the work of sports and leisure trusts who deliver a range of programmes designed to benefit health and wellbeing. (see in particular Part 2 of this report)

The Fire Service

The fire service identified the key to reducing the tragedies and hardship caused by fire. Stopping fires from starting required the fire service to work together with communities to deliver safer communities. This was set against the knowledge the two highest-risk groups within the community -the elderly and those living alone- were set to increase in size.

In 2003 the fire service across the UK linked improved pay and conditions for employees to a programme of service reform intended to promote a more targeted and risk-based approach to prevention, protection and emergencies. They were expected to give greater priority to improving the safety of communities by reducing risks from fire and other emergencies. The Fire (Scotland) Act 2005 introduced further changes placing a strong emphasis on prevention rather than simply emergency response.

The outline business case prepared in 2011 to support what eventually became the amalgamation of the then eight regional fire and rescue services in Scotland highlighted how successful this change of approach had been. It showed that in the period from 1999/2000:

Dwelling fires had decreased by 30%

Fire casualties had decreased by about half

Fire fatalities had decreased by 47%.

Barriers to preventative spending

In their 2011 report on preventative spending the Finance Committee set out the following barriers they had encountered impeding successful preventative spending.i

Who benefits;

The political cycle

Cause and effect;

Impact of budget cuts;

Maintaining reactive services;

Evaluation and measurement of spend; and

Shifting resources to localities.

We heard similar issues continue to exist as follows.

Who benefits?

The then Cabinet Secretary for Finance and Sustainable Growth told the Finance Committee that the mere fact the body that makes an investment is not the one to derive the benefits should not act as a barrier to preventative spending. While our inquiry was narrower, focussing solely on the health and care service we have heard examples of clinicians being reluctant to introduce new ways of working or new technology because savings that might accrue do not come back to their own budget. In our neurology inquiry we heard how through efficiency savings bed days reduced by 75% without any return being provided to those making the savings. This lack of any budgetary incentive was suggested as a significant block to services wishing to introduce change.

We have heard of a similar situation arising from Integrated Joint Boards (IJB) with their attempts to make use of set aside budgets. As they introduce new ways of working which reduce demand and cost rather than the benefit accruing to the IJB the value is deducted from the amount of budget set aside by the Health Board which means only the Health Board benefits from the changes made by the IJB.

The political cycle

As the Finance Committee stated the benefits from preventative spending can take a long time to realise and this could reduce the incentive for governments to invest. One of the functions of the National Performance Framework is intended to address this effect although it would be helpful if it were made more explicit. In the work of our committee we are endeavouring to take a longer-term view of when and how benefits can be measured. We have however been provided with little evidence of any such activity or longer term view in our ongoing scrutiny of Health Boards and Integrated Joint Boards.

Cause and effect

Professor David Bell gave us evidence about counterfactuals which are when it is difficult to establish what would have happened without the preventative action being taken... We then heard this has been modelled in a few areas using the triple-I tool (see paragraph 50). We also heard about the need for more marrying of cause and effect by looking at causal linkages using all the data available to us whether it be social, economic or even genetic.

All of that said, the absence of the ability to identify conclusive proof should not be a justification for doing nothing. Professor Susan Deacon, a former Scottish Government health minister, told the Finance Committee:

The fact is that it is difficult - in some cases nigh on impossible - to quantify the impact of preventative spend. It is hard to prove that if we had not acted or intervened there would have been a poorer outcome or to demonstrate short term improvements where change may be generational. But existing evidence, not to mention professional judgement, human intuition and experience – and sheer common sense – can take us a very long way.”ii

We note here the evidence we have considered about the fire service and the 10 year reductions in fires, casualties and fatalities we highlight above (see paragraph 35). While the multi-layered and complex systems of health and social care can't provide a direct comparison, this demonstrates for example the potential outcomes of shifting the system mindset to one of prevention.

Impact of budget cuts

Finance Committee also explored whether public sector budgetary restraints could make a focus on preventative spending less likely.

Over the period since 2011-12, the Scottish Government's overall budget has risen by 2% in real terms (adjusted for inflation). By comparison, the health budget has fared more favourably, rising by 7% in real terms over the same period.

The faster increases for the health budget will be to some extent because of the fact that health inflation tends to be higher than inflation in the economy generally.i

Maintaining reactive services

There was discussion in the Finance report that increasing investment in preventative spending does not mean existing reactive budgets can be cut and there may be a need for dual funding of both reactive and preventative spend.

During the 18 April 2008 debate on this topic the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport stated the Scottish Government was “making a significant investment and engaging in structural reform with the aim of prevention”i. In the health field she added that the reform of health and social care “has brought about a fundamental realignment of resources that will build the capacity and strengthen the preventative action of our community-based services.”

Also in that debate agreement was stated with the Royal College of Nursing that “spending on preventative health may mean redistribution, service redesign and investment in the benefits of primary prevention.

We have consistently heard from Health Boards and practitioners of the need for dual funding while the Scottish Government remains convinced current levels of investment, used wisely, are adequate to allow capacity to be built without dual funding. This is reflective of the assumptions some make about the 2020 vision, that a shift of focus and resource to community and preventative care will reduce the spend on acute care.

Evaluation and measurement of spend

The third question we posed in our general call for views asked "How could spend that is deemed to be preventative be identified and tracked more effectively? What is required in terms of data, evidence and evaluation to test interventions for producing ‘best value for money’?”

Responses to the question were mixed, NHS Health Scotland indicated “More precise measurement of current spend on prevention would be a good thing in principle but challenging in practice”. While Audit Scotland in their health inequalities report found many initiatives to reduce health inequalities have lacked a clear focus from the outset on cost effectiveness. That report indicated Audit Scotland found assessing value for money difficult.

Round table participants urged us to think critically about the evidence presented, in particular what it is that determines the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a measure. We heard about the triple-I tool which is used to inform a few, mainly high-level investments to reduce health inequalities. The impact of interventions, mortality and hospitalisation can, we were told, be modelled including identifying hospital costs.

However overall we learned of a shortage of data and modelling taking place, which is surprising considering how rich Scotland is in health data.

Shifting resources to localities

Locally we heard from Midlothian about their practical experience of looking at local data. They had thought they had all the data but when digging deeper into the raw data, utilising expert assistance, they found they learned more about their area and their people. This has led them to look at “gap indicators” to determine whether they were closing the gap in certain areas and localities. For example the positioning of mental health services was made more attractive and applicable locally using the data they had to both plan and redesign services. East Lothian is another area developing intelligence about its population for use in developing its services.

In all localities Community Planning Partnerships (CPP) are required to produce Locality Plans under the requirements of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015. Each plan should adopt a ground level approach, empowering the residents and those working in the locality to play an active part in identifying the local priorities. The plans are also designed to make sure local needs are being supported.

Joint Boards are required to produce Strategic Plans. The Strategic Plans should set out their objectives for improving health and social care services for the people in their areas. Locality plans should be instrumental in providing a framework for Joint Boards intending to improve health and well-being.

Scottish Borders in their localities plan for Berwickshire indicate it lays the foundations for the key priorities for improvement going forward. Their plan notes their aspiration to bring their locality plan and the separate localities plan produced by Community Planning Partnerships together within one plan.

Audit Scotland in their report Changing Models of Social Care recommended the learning from new models of care across Scotland and elsewhere be shared effectively with local bodies. We heard from a number of witnesses that the NHS is not good at learning lessons of general applicability from different parts of the country. It appears to lack any mechanism to allocate any responsibility to systematically identify and spread best practice. We have come across this deficiency in nearly every inquiry we have undertaken this session.

Audit Scotland were clear of the need to identify what the intention of an initiative is at the start, what it is trying to achieve and the methods of measuring the gap that needs to change. The evaluation of initiatives needs to be designed and built into measures at the outset.

Midlothian Joint Board echoed these thoughts telling us:

There is not always a straight link between what we do in one intervention and an impact. Often, a shift is due to a range of interventions. What is harder to evaluate is a different culture around how we use resources, which is about really understanding what will make a difference to individuals’ lives. It is all those things together that make our work very complex. We need to be constantly alert to what is working, and to be testing things

Next steps

During this phase of our inquiry we were advised there was no need for further analysis of the issue – there was a commonality of views in the submissions received and evidence heard.

We accepted the above assessment and determined as our next step to consider the key question “what actions on the ground are going to make a difference”.

We therefore decided to consider a number of discrete areas within our overall remit and seek to identify whether preventative spend was taking place and whether there were any common traits of such spend we could identify.

Our Inquiry: Part 2

We agreed to continue our inquiry through a number of short inquiries holding one-off evidence sessions focussing on particular areas of mainly public health activity to ascertain how far that activity is addressing the preventative agenda. In addition, we considered several other specific areas of activity brought to our attention.

For each inquiry we agreed to utilise three overarching questions:

To what extent are the services, the relevant strategy and the approach by integration authorities and NHS Boards preventative?

Is the approach adequate or is more action needed?

How are the services and relevant strategy being measured and evaluated in terms of cost and benefit?

In each case we held evidence sessions, we issued a targeted call for views and heard evidence from connected and affected parties. At the conclusion we wrote to the Scottish Government outlining our key findings relevant to the particular subject and seeking further information and on occasion additional clarification.i

Type 2 diabetes

Diabetes is a chronic disease, characterised by high levels of glucose in the blood. It occurs either because the pancreas stops producing the hormone insulin (Type 1 diabetes), or because the cells of the body do not respond properly to the insulin produced (Type 2 diabetes). People with diabetes are more likely to suffer from cardiovascular diseases such as heart attack and stroke, sight loss, foot and leg amputation and renal failure.

People with Type 2 diabetes are likely to have a life expectancy of 10 years less than the average (20 years less for Type 1).

According to the annual survey report ‘Diabetes in Scotland’ for 2016, 257,728 people in Scotland have Type 2 diabetes. 87.2% of these are above their ideal weight according to their Body Mass Index (BMI).

The prevalence of both types of diabetes has steadily increased over the past ten years, but Type 2 accounts for 85 – 90% of those with diabetes.

According to the York Health Economics Consortium Ltd. study, diabetes (all types) accounts for approximately 10% of the total health resource expenditure and is projected to account for around 17% in 2035/6. The direct health costsiii of Type 2 Diabetes in 2010/11 were £8.8 billion in the UK (based on Scotland having 10% of the UK population, this translates into a direct health cost of £880 million to the NHS in Scotland) (total NHS draft budget in Scotland 2017-18 = £13.2 billion).

The researchers also considered indirect costs, estimated from mortality data, sickness, informal care and potential loss of productivity among people employed. The indirect costs were £13 billion for the UK, approximately £1.3 billion in Scotland. They projected these costs in 25 years to 2035/2036:

Direct costs £15.1 billion (UK) £1.5 billion (Scotland)

Indirect costs £20.5 billion (UK) £2 billion (Scotland)

Diabetes Scotland's submission indicated 3 in 5 cases of type 2 diabetes can be prevented or delayed and we heard that for Type 2 diabetes prevention is achieved by means of exercising regularly, eating healthily and avoiding smoking. According to the WHO, prevention requires a “life-course perspective” and a “whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach”.

Prevention is the Scottish Government's top priority along with early detection, and is aim one of the Diabetes Improvement Plan (November 2014). However the evidence we received suggested a clinical focus on preventing complications and early detection, i.e. secondary and tertiary prevention, to the exclusion of primary prevention. In response the Scottish Government referred to a prevention working group who input to the Obesity strategy consultation. Their subsequent Framework A Healthier Future – Framework for the Prevention, Early Detection and Early Intervention of type 2 diabetes - published in July 2018 states “it has been developed to provide guidance to delivery partners as to the implementation of a specific weight management pathway for those ‘at risk’ or those diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.”

It was suggested to us Integrated Joint boards are expected to have a focus on prevention yet in 24 of their strategic plans diabetes does not appear.

The Committee heard that data is routinely collected by clinicians with a wide range of information available locally to NHS Boards. This information is not published and the Scottish Government confirmed no national targets or standards are in place. We were also told different Boards target different areas for improvement reflecting local issues. Given the absence of any published data we are unable to identify what current activity is taking place locally and how effective it is. Nor does it appear there is any central co-ordination of activity enabling learning and best practice to be shared.

The newly published framework includes detail on its evaluation and how success will be measured.

We would welcome detail of how the concerns expressed above will be addressed by the proposed evaluation and measurement processes including in particular proposals around central co-ordination and sharing of best practice.

Sexual health, blood-borne viruses and HIV

The Sexual Health and Blood Borne Virus Framework was published by the Scottish Government in 2011 bringing together policy on sexual health and wellbeing, HIV and viral hepatitis. It set out five high-level outcomes which the Government wished to see delivered, and sought to strengthen and improve the way in which the NHS, the Third Sector and Local Authorities supported and worked with individuals at risk of poor sexual health or blood borne viruses.

An updated framework was published in August 2015 to cover the period 2015-2020. The Framework notes that “prevention remains a fundamental principle for all parts of the framework”.

Health Protection Scotland (HPS), a division of NHS National Services Scotland, is responsible for monitoring HIV, blood-borne viruses and sexually transmitted diseases. HPS published its latest report on 19 December 2017

‘to provide an up to date epidemiological summary of the scale and response to BBVs and STIs in Scotland, highlighting key trends and identifying areas for priority action.’

HPS stated around 34,500 individuals are estimated to be living with chronic Viral Hepatitis with around 19,000 having been diagnosed. At September 2017 there are an estimated 5271 individuals diagnosed and living with HIV in Scotland with a further estimated 800 infected but undiagnosed.

The HPS update report from December 2017 also referenced PrEP - pre-exposure prophylaxis- an oral daily treatment taken every day by people who do not have HIV which prevents them acquiring it.

HPS has also launched a new data portal (December 2017), providing access to a wide range of data that is explicitly linked to the outcomes and indicators contained within the Framework.

On 23 January 2018 we took evidence from a range of witnesses having previously asked them to submit written evidence. Following the evidence we wrote setting out our thoughts to the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport on 21 February and she replied on 21 March 2018.

We were made aware that currently no national health body has strategic responsibility for policy and practice in this area. The Cabinet Secretary indicated there might be a possible role for the new public health body once created. The Integrated Joint Board in Glasgow was praised for its work in pulling together the commissioning of third sector provision and for having a person in charge of addiction, homelessness and mental health.

It was unclear to us whether the approach of the Glasgow Joint Board was being replicated across the country even although we heard evidence about a multitude of bodies, groups and third sector organisations active in this field. The absence of any co-ordination or central network was repeatedly highlighted to us.

In terms of a preventative approach we heard the focus is on identification and early treatment of sufferers, i.e. secondary and tertiary prevention. Screening programmes are only provided following a recommendation by the UK National Screening Committee, they are currently considering a programme for Hepatitis C in pregnancy. Opt out Blood Borne Virus (BBV) testing for new prisoners in Scotland is being discussed with NHS Boards and the Scottish Prison Service.

In relation to Hepatitis C, we heard evidence on 23 January 2018 from George Valiotos, Chief Executive of HIV Scotland, supported by other experts providing evidence to the committee, which suggested that it is possible to eradicate Hepatitis C in Scotland:

"In this environment, it is essential to think about the fact that, in Scotland, we have everything that we need to cure hepatitis C and to eliminate HIV—we have all the tools. Treatment works: we know that if someone who has HIV is on treatment, they will be uninfectious. We know that we can cure hep C through treatment. (column 6)

Despite the work of HPS and their data portal no data has been collected on young peoples’ experience of sexual health education since a MORI survey in 2012.

We asked the Scottish Government whether a cost benefits analysis of the 2011 Framework had been undertaken but unfortunately did not receive any response on that point. We would welcome information on whether a cost benefits analysis of the 2011 Framework was undertaken.

Although we were advised the clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of medicines is monitored and some assessment of effectiveness in relation to hepatitis C infected people is undertaken we were unable to ascertain how the new Framework is going to be assessed.

We note that following the Framework being updated to cover the period 2015-2020 for none of the new outcomes 1, 4 and 5 covering sexual health and wellbeing is data being collected. These cover, for example:

gender-based violence recorded in specialist sexual health services;

acceptability of services to those living with, or vulnerable to, poor sexual health and/or blood borne viruses;

young people's sexual health education; and

understanding of ST infections, their transmission and long-term health effects in the general population.

It is difficult to understand how these aspects of the Framework can be assessed for their effectiveness in the absence of data collection.

We would welcome details from the Scottish Government on each of the above aspects. In addition, we would welcome the Scottish Governments views on the potential to eliminate Hepatitis C in Scotland and would welcome any plans from the Scottish Government to introduce an elimination plan for these infections.

Substance misuse

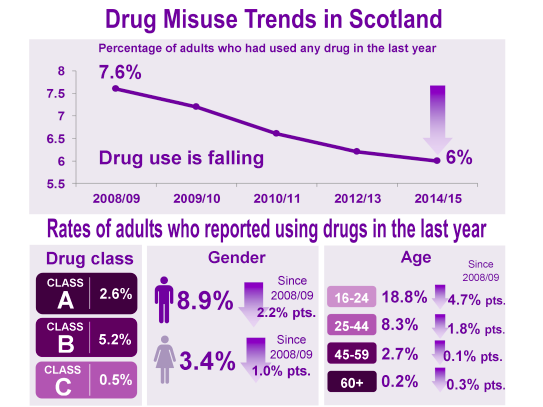

The number of drug-related deaths in Scotland has steadily increased over the past 20 years, rising from 244 in 1996 to 867 in 2016. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction collates death rates per million of population for EU countries, which is presented in the National Records for Scotland annual report. This data shows that Scotland has a rate of 160 drug misuse deaths per million, and the UK has a rate of 60 per million. Most of the data on drug related deaths is not however directly comparable across the UK nations.

In Scotland, problem drug use is disproportionately high compared with England and other European countries. According to this data, Scotland has the highest rate of any country in the EU. It is estimated that in Scotland drug misuse costs society £3.5 billion a year whilst the impact of alcohol misuse is estimated to cost £3.6 billion a year - combined, this is around £1,800 for every adult in Scotland (Scottish Government).

In 2008, the Scottish Government published the national drugs strategy for Scotland, ‘The Road to Recovery’, which set out a strategic direction for tackling problem drug use. The Scottish Government states that the strategy focuses on recovery but also looks at prevention, treatment and rehabilitation, education, enforcement and protection of children. This was followed up with a Framework for Action on Alcohol and drugs in 2009. This led to the inception of Alcohol and Drugs Partnerships in 2010. The Scottish Government publish a partner document, ‘Research for Recovery’, which reviews the evidence to support the strategy in relation to effective interventions in 2010.

The SPICe Briefing on the Strategy (The Road to Recovery) highlights some developments in Scotland and internationally since it was introduced.

Problem drug use associated with the prolonged use of opioids and benzodiazepines, particularly among injecting users, are associated with the most severe health harms. Opioids were implicated in 89% of all drug-related deaths in 2015.

The rate of drug-related general acute stays increased steadily from 41 to 162 stays per 100,000 population between 1996/97 and 2016/17. After a lengthy period of stability, the rate of drug-related psychiatric stays increased from 29 to 36 stays per 100,000 population between 2014/15 and 2015/16.

In the most recent available year's data, 61% of drug-related general acute stays were due to opioids (drugs similar to heroin) while 51% of drug-related psychiatric stays were associated with ‘multiple/other’ drugs. Approximately half of patients with general acute or psychiatric stays in relation to drug misuse lived in the 20% most deprived areas in Scotland.

In 2015/16, 3,860 patients (72 new patients per 100,000 population) were treated in hospital (general acute/psychiatric combined) for drug misuse for the first time. The drug-related new patient rate has increased by almost 50% since 2006/07 (49 new patients per 100,000 population).

Alcohol and Drug Partnerships (ADPs) were created in 2010 to address alcohol and drug prevention, treatment recovery and support services at a local level within each local authority area. ADPs are required to report to the Scottish Government annually, covering: financial framework, ministerial priorities along with additional information – on subjects such as research undertaken, work with partners, workforce development etc.

The direct funding of ADPs has reduced over the past two years, but with an expectation that health boards make up any shortfall required to sustain the work led by the ADPs. A number of witnesses raised the reduction in funding as an issue, as well as the lack of transparency of spending now that IJB's are responsible for services.

Glasgow ADP provide a breakdown in expenditure that shows that less than 4% (£1.9 million) of its expenditure goes to prevention with the remainder ~ £45 million, going to treatment and recovery services. In this context “recovery” implies maintenance on methadone with little other apparent support being provided to methadone users.

On 30 January 2018 we took evidence from a range of witnesses having previously asked them to submit written evidence. Prior to the formal evidence session members held, within their own constituencies, informal meetings with drug users to hear real life experiences. Following the evidence we wrote setting out our views to the Minister for Public Health and Sport on 6 March 2018 and she replied on 25 April 2018.

Our interest in ADPs is long standing and we are concerned by the number of drug-related deaths in Scotland and the rate of deaths in comparison to other countries. We remain concerned at the reported level of spending in this area which we will continue to monitor in our ongoing scrutiny work.

We heard evidence about the lack of any current evaluation framework to assess the current strategy and also deficiencies in data collection, particularly data relating to the experiences of those living in deprived communities. Our concerns to ensure adequate funding by Health Boards and Integrated Joint Boards are also long standing.

In our letter to the Minister we sought assurance a new strategy would be far-reaching and extensive and deliver change leading to a reduction in the human and financial costs of misuse. The Minister acknowledged “current services in Scotland are not fully meeting the wide range of complex health and social needs of those who are most at risk from the harms associated with substance use”.

It remains disappointing that despite this recognition and many months of engagement no government proposals are forthcoming. We remind the government the existing strategy is over 10 years old and does not reflect changes in drug culture over that period.

We also highlighted, for the third time, our concerns around healthcare in prisons and remain disappointed that no updates on progress have been provided. We particularly regret the Scottish Government has not notified us of any resources that have been allocated.

We would welcome the Scottish Government's thoughts on widening and strengthening the focus on prevention in a revised strategy (i.e. not just abstinence). In addition we would welcome the Scottish Government's views on whether they consider funding in this area should be prioritised and if so how this can be achieved given the competing demands for spend on recovery and support services.

We also recommend prominence in the strategy be given to monitoring and evaluating activity by all the Boards and how resources are being allocated.

Given the detailed recommendations made in 2016 by the National Prisoner Healthcare Network we again urge the Government to ensure these are implemented. In our future scrutiny of Health Boards who have prisons within their areas we will continue to take a close interest in this work and expect action to tackle drug misuse in prisons to have been taken.

Detect Cancer Early

Cancer is one of the major causes of death in Scotland and, in 2015, 16,011 people died of the disease with approximately 31,500 people newly diagnosed. An estimated 40% of cancers are attributable to preventable risk factors which could be addressed through behavioural change.

The most common cancers in Scotland are lung, colorectal and breast cancer, which collectively account for over 43% of all cancers diagnosed.

The Detect Cancer Early (DCE) programme was formally launched by the Scottish Government in February 2012. The programmes main purpose was to raise the public's awareness of the national cancer screening programmes and also the early signs and symptoms of cancer to encourage people to seek help earlier.

The DCE programme is fundamentally an early detection rather than prevention programme although we were advised of some work undertaken through DCE in the prevention agenda. We were also advised of a limited impact the programme had had on differential deprivation rates albeit a gap between the most and least deprived communities still exists.

DCE is an example of ‘secondary prevention’ in that it aims to detect and treat an existing disease early on, as opposed to preventing it in the first place.

The DCE programme was initially focused on the three most common cancers. We heard the target to increase by 25% the proportion of people diagnosed and treated in the first stages of these cancers fell disappointingly short.

We heard that Scotland's cancer survival rates remain lower than many other countries and late diagnosis contributes to this. Yet the aim of the DCE was to improve cancer survival by diagnosing and treating the disease at an earlier stage.

We heard that DCE includes elements of primary prevention (e.g. the detection and treatment of pre-cancerous colorectal polyps) but it is not aimed at primary prevention and there is no specific budget for such activities.

We also heard the Scottish Cancer Prevention Network state that “we cannot treat our way out of the rapidly increasing cancer problem and that an integrated approach to prevention, early detection and treatment is required”. They also stated that investment in cancer prevention is ‘negligible’ within the cancer strategy.

In recent years, performance against the 62 day waiting time standard has been falling. The 62 day target covers the period from referral, through diagnostics, to treatment. A separate 31 day target covers the period from diagnosis to treatment.

This is an area where data on activity by the Health Boards is readily available, particularly in relation to the 62 and 31 day targets. What is less clear to the Committee from our scrutiny of individual Health Boards is the extent to which any action is taken by or against Boards who consistently fail to hit the targets. There would appear to be a lack of any urgency or incentive within Health Boards to meet a performance level described to us by the Cabinet Secretary as "not good enough".

We would welcome an update from the the Scottish Government setting out when they expect each Board to meet both the 62 and 31 day targets.

We also heard conflicting messages on the cost benefits of targeted campaigns and screening programmes. It was suggested the focus continues to be on detection campaigns, highlighting possible symptoms rather than focussing on the known risk factors.

We ask the Scottish Government for their proposals to refocus targeted campaigning and screening programmes to address or rebalance this position more towards primary prevention.

Neurological Conditions

It is estimated one million people in Scotland are currently living with a Neurological condition. The World Health Organisation defines neurological conditions as neurological disorders or diseases of the central and peripheral nervous system, including the brain, spinal cord, cranial nerves, nerve roots and peripheral nerves, autonomic nervous system, neuromuscular junction and muscles. Neurological conditions have an impact on people physically, it can prove difficult to undertake routine daily tasks and also emotionally and cognitively affecting relationships and social interaction.

Over recent years there have been significant policy initiatives to improve the way in which health care is provided for patients with neurological conditions. Most notably, NHS Quality Improvement Scotland published evidence based Clinical Standards for Neurological Health Services (2009). The standards aimed to address the variability of services and improve the patient journey from the point of referral into the service. They also aimed to set a level of care for all patients with neurological conditions and give specific indicators for Epilepsy, Headache, Motor Neurone Disease, Multiple Sclerosis and Parkinson's disease.

The health and care standards which set out expected essential and required levels of service and care are out of date and due to be updated next year.

We wrote to the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport on 24 April 2018, and 13 June receiving replies on 22 May and on 26 June.

Throughout the evidence received and the correspondence it was clear this was a reactive service with many people falling through the cracks. Prevention in this context entails:

Preventing unscheduled admissions

Improving rehabilitative care and ongoing support, including psychological support, to assist with self-management and independent living; and

Ensuring appropriate residential care and respite is provided when required for individuals and their carers.

We were unable to identify any specialist neurological services for which responsibility had been delegated to an Integrated Joint Board. In some areas services/elements of services used by people with neurological conditions are delegated, for example homecare or home adaptations. The absence of delegation is perhaps not surprising at this stage as we are not aware of any initiative in place to provide the IJBs with support by providing central strategic commissioning guidance.

We were advised data collection was lacking with issues around prevalence data and service provision data. There was no central database collecting or collating data. ISD are undertaking some work to identify existing data sources but have not been asked to redesign collection systems without which the data will continue to be patchy and incomplete.

As a consequence there was no information available as to the number of persons being treated by the NHS with neurological conditions or of the costs being incurred. Without this basic information it is also impossible to identify the benefits delivered from the various parts of the NHS in relation to these conditions.

The previous health and care standards were not met by 60% of health boards and were not monitored by Health Improvement Scotland. We were advised there are no plans to change this or develop any indicators. The Scottish Government also rejected our suggestion for the appointment of responsible officers who would be locally responsible for monitoring and reporting on compliance with the new standards.

As part of our evidence session we heard about the work undertaken by Leuchie House who provide specialist respite care for persons suffering from such as stroke, Motor Neurone Disease, Parkinson's, cerebral palsy and Huntington’s. The service they provide is estimated to save the NHS some £1.7 million per annum.

Finally we are aware of the report by Sue Ryder setting out "the case for proactive neurological care" which suggests the proactive approach to care they advocate delivers better quality and longevity of life and can deliver savings to the funder.

We would welcome the Scottish Government's response to the Sue Ryder report.

The absence of any coordinated approach across the NHS including the IJB’s is concerning and adversely affecting the standard and quality of care available. We expect this to be remedied quickly with both the new action plan on neurological conditions and new standards currently being consulted upon.

We expect standards to be met and appropriate arrangements put in place to monitor performance across the country allowing those with responsibility to be held accountable for the standard and delivery of services.

Clean air

In 2012 the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that around six million premature deaths were caused by air pollution exposure, identifying it as being amongst the top ten risk factors for mortality in the UK. In the UK alone it is estimated to cause 40,000 deaths each year.

Air pollution is estimated to reduce the average life expectancy of every person in the UK by six months, and costs the UK economy around £54 billion per year, although there are a range of estimates around this number. SEPA claims that air pollution currently represents the greatest environmental threat to human health.

In 2013 the WHO stated that:

Exposure to air pollutants is largely beyond the control of individuals and requires actions by authorities at a national, regional and international levels.

The Scottish Government is required to devise its own air quality strategies and policies under Part IV of The Environment Act 1995. The Scottish Government produced the Cleaner Air for Scotland: The Road to a Healthier Future (CAFS) report in 2015.

The Scottish Government created CAFS with the intention of it being a cross government initiative to reduce air pollution from a range of sources. For the purpose of this inquiry CAFS can be seen as preventative as it seeks to reduce levels of air pollution, in turn positively impacting on public health.

The CAFS sets out how the Scottish Government and its partner organisations propose to reduce air pollution further to protect human health and fulfil Scotland's legal responsibilities. A series of actions across a range of policy areas are outlined including a National Modelling Framework, a National Low Emission Framework, adoption of WHO guideline values for particulate matter in Scottish legislation and proposals for a national air quality awareness campaign.

In June 2017 the Scottish Government published its 2016 progress report on CAFS, leading to the inclusion of a number of actions relating to Air Quality in their 2017-18 Programme for Government. None of the action points are health related.

Health risks which are being widely reported associated with air pollution include:

Asthma

Stroke

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Lung Cancer

Diabetes

Dementia

Obesity

CAFS demands that:

NHS Boards and their local authority partners are to include reference to air quality and health in the next revision of their joint health protection plans (JHPPs), which should identify and address specific local priority issues.

A recent survey by Health Protection Scotland found that a majority of IJBs have included air pollution as a topic in their most recent Joint Health Protection Plans, and that a majority wanted to include it in their next plan. However it was suggested the absence of outcome-based targets in this area dilutes responsibility and accountability. It was suggested the lack of targets and monitoring of performance meant there was no incentive for the IJB’s to act on their plans. It was also suggested to us the absence of guidance in this area hinders delivery and also monitoring of performance.

We issued a call for evidence and received 6 responses prior to an evidence session with various organisations and health charities held on 17 April 2018. Included among the invitees to provide evidence were Edinburgh Health and Social Care Partnership and NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, however, both regrettably were unable to send representatives. Our evidence session was timely as it coincided with a plenary debate on the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committees report on Air Quality in Scotland. We have not written to the Scottish Government following the evidence session.

Much of the evidence we heard and received centred on the pollution created by transport. We heard of a direct correlation between traffic levels and air pollution levels with many of the areas most affected being in areas of high deprivation. It was suggested there were 100,000 hospital admissions as a result of respiratory conditions in 2017, making the condition the second highest reason for emergency admission.

We heard about a potential role for planning policy and also about design of new housing estates. We understand there is a lot of guidance available to local authorities and other bodies on effective interventions to reduce air pollution. We also heard about the introduction of a low-emissions zone in Glasgow.

Overall it was stated there was a lack of data collection and monitoring around the country. A need for long-term monitoring sites was suggested to allow the measurement of trends. An increase in monitoring in areas of high deprivation and areas suffering from higher than average rates of illness was also urged.

Other preventative services

In addition to the discrete inquiries covered above Committee members have received briefings and submissions from a range of organisations. The following section contains information received from two organisations each of whom both work directly and indirectly in the health and social care field providing preventative services.

Optometry services

Members of the committee received submissions from Optometry Scotland covering initiatives being undertaken by the profession in Scotland.

Following a review in 2005 of community eye-care services revised arrangements (GOS) were put in place in 2006 to make better use of community optometry resources in delivering care.

One of the principal drivers behind the redesign of GOS was to introduce measures that would allow Community Optometrists to fully utilise their skill set in the early detection and management of eye disorders. This has produced major benefits for the public allowing easy access to an expert community service, providing early intervention, rapid diagnosis, management and prevention of ongoing ocular morbidity.

Prior to 2006 approximately 25% of acute / emergency eye cases were managed in the community setting. Now over 80% of acute eye conditions are managed by optometrists. This has shifted the balance of care away from hospitals, freeing up resources to deal with more complex care. In 2016/17 over 1 million cases of people living with, or at risk of, eye disease were recorded in data collated by ISD.

This has also freed up GP appointments creating capacity elsewhere in primary care. Optometrists have become the first port of call for eye problems presenting in the community. Like all disease the earlier eye problems are detected the better the likely outcome for the patient. Less morbidity, avoidance of sight loss - better quality of life and independent living are maintained with the risk of injury and falls reduced.

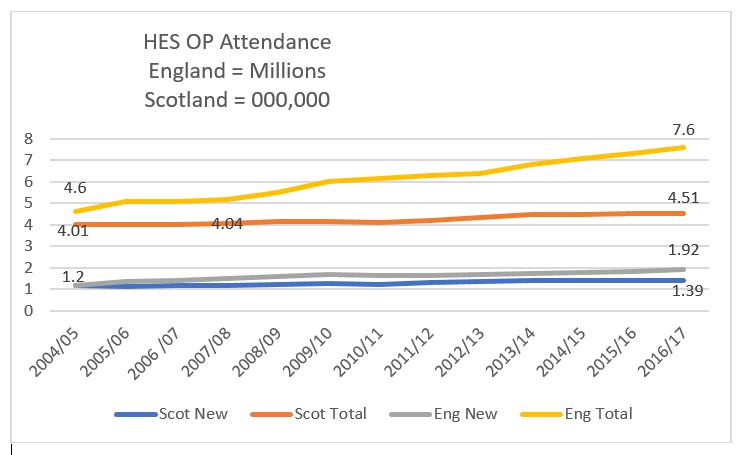

A comparison with England is contained in the following graph which shows that since 2005 new outpatient attendance in England has risen by 38% from 1.34 million to 1.92 million in 2017 while total outpatient attendance has risen by 40% from 4.64 million to 7.6 million. Over the same period total outpatient attendance in Scotland has increased by 8%.

An estimate of the cost savings from this change to delivering eye care in the community suggests the NHS “saved” £43 million in 2016/7 when ISD costs for hospital outpatient care are compared with optometry costs.

In some NHS Boards, most notably Lanarkshire and Grampian the changes have been further developed and integrated into other aspects of NHS Board activity resulting in over 85% retention of acute eye care presentations in the community. In Grampian this development has led to the closure of the walk in eye casualty department, as much of the case load was dealt with by optometrists in the community.

Overall it appears the changes brought about by GOS are allowing more patients to be seen in the community, reductions in morbidity and improved outcomes for patients. Together with "savings" to the NHS and a significant shift in the balance of care.

We would welcome the views of the Scottish Government on how the enhanced service in Lanarkshire and Grampian can be rolled out across the whole country.

Demographic changes and increasing numbers of older people will result in an exponential increase in eye disease. The greatest challenge will be managing those patients that require surgery and hospital care as well as those living with chronic eye disease such as cataract, maculopathy, diabetic eye disease and glaucoma for example.

Sport and leisure trusts

A key purpose of the Arm's Length External Organisations “ALEOS”iis to improve the health and wellbeing in all their populations through tackling health inequalities. During an informal briefing session with Sportaii members of the committee also heard about how their members have become drivers of improved health and social outcomes in large, small, urban and rural communities across Scotland.

Members were advised that 20 trusts had indicated they collectively now employ 1300 staff solely for programmes targeting health conditions such as coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer and mental health. They have a key focus to improve the preventative spend impact of their work in health, wellbeing and employability. The growth in the older population and need for support around mobility, balance and dementia has led trusts to develop a range of new programmes for older people, from falls prevention schemes, walking clubs and football, and Memories/Reminiscence projects.

While not all their work has been evaluated some significant examples were provided.

Examples evaluated covered the delivering of falls prevention programmes, healthy active minds directed at sufferers from depression, anxiety and stress. We noted research carried out for the Scottish Government in 2013 which found participation in culture and sport being independently and significantly associated with good health and high life satisfaction. Those attending a cultural place or event being almost 60% more likely to report good health compared to those who did not attend.

A social impact evaluation carried out across a number of West Lothian Leisure projects concluded that the social benefit delivered equated to £16,923m for 2011 alone. This included a calculated sum of £9.8 million savings to the NHS and the wider economy. Another study conducted by the same researchers across a number of Edinburgh Leisure programmes found health care savings of £25.5m.

Falls prevention

In 2012 NHS Highland reported that around 80 hospital beds a day were used by older NHS Highland residents who had experienced a fall, at a cost of around £400 per day per patient and £11.6M per annum.i

In common with a number of Scotland's trusts, High Life Highland delivers a widespread programme of falls prevention exercise, in partnership with NHS Highland, in care settings, including care homes, town and village halls and leisure and cultural facilities. This has resulted in a significant drop in the number of falls experienced by the older population, improved physical and mental health and savings to NHS Highland.

Over the next 20 years, as the population continues to age, the number of admissions for falls and related injuries are forecast to double. Comparison of the costs of hospital beds due to falls against the costs of an exercise instructor delivering a regular exercise session at £25 per hour reveals a preventative opportunity for multi-million pound NHS savings, on top of the many documented physical and mental health gains.

We ask all Integrated Joint Boards to report in their annual reports on the work they are undertaking on falls prevention.

Conclusions and recommendations

It is now seven years since The Christie Commission on the Future Delivery of Public Services identified the importance of preventative action and a preventative approach to avoid failure demand with resources tied up to address short-term problems. Also in 2011 the Finance Committee reported on the “remarkably strong evidence about the benefits such an approach could deliver.”

Successive Governments have recognised the necessity of preventative actions and this is reflected in policy documents such as the 2020 vision and public health priorities for Scotland (2018). Audit Scotland have continued to urge action to identify and measure preventative activities.

Throughout this inquiry we have encountered many examples of preventative activities, however the overwhelming majority are directed at secondary or tertiary prevention i.e. actions to address existing problems and/or to prevent them worsening.i

We have observed a lack of primary prevention, i.e. public health policies that tackle social determinants. This is compounded by an over-focus on the easier hospital based secondary and tertiary prevention. We observe these are things that can be counted, which should, as Sir Harry Burns says, be only indicators of good outcomes not the numerical outputs, (targets) met or not met. These have unfortunately become the end in themselves.

During our ongoing scrutiny of the Scottish Governments revised National Outcomes we heard further evidence about the importance of cross portfolio work being undertaken. This included consideration of adverse childhood events and the value of early impacts across a range of areas to give people, in particular children, hope. It was suggested a positive and nurturing childhood allows learning, participation and encourages good behaviour all of which improves opportunities with consequential impact on their health and wellbeing both now and in the future.

All of this makes our inquiry timely as the National Performance Framework is refreshed and targets are reviewed offering the opportunity to create new indicators more aligned with prevention.

As the population ages it is imperative greater focus is given to address primary prevention, prevent people becoming ill with known preventable diseases, to lengthen peoples' healthy lifespan and reduce the time they spend in ill health.

We asked for an update from the Scottish Government on their progress towards a new suite of indicators following the work of Sir Harry Burns in our recent report on NHS Governance and request that this is now provided. We are keen to support the creation of indicators that are meaningful to the staff who deliver services and to understand how new ways of measuring inputs and effectiveness can support an increase in preventative activity.

We recommend the Scottish Government adopt a definition of prevention, our working definition is, we consider, a clear and concise description of what Christie was referring to and is “Spending public money now with the intention of reducing public spending on negative outcomes in the future.” Definition is important to enable the effectiveness of actions to be measured both in monetary terms and the delivery of better outcomes for the public who use and receive services.

In our opening chapters we consider locality planning and how some Joint Boards are using and developing local data to assist in the design and redesign of services. These locality plans provide a rich resource upon which all Joint Boards could draw.

We recommend locality plans are collated nationally allowing the Joint Boards and others to identify successful local practices and local interventions from across the country. We ask the Scottish Government for proposals on how this can be achieved.

One of the most important overall preventative strategies is to reduce the inequalities in health.

We heard a lot of talk around the impacts of health inequality throughout our inquiry and we recommend addressing health inequalities should be at the heart of all health policy.

We agree with this conclusion by our predecessor committee in their health inequalities report:

"We recommend all policy contains an assessment of the impact expected on health inequality and this is then tracked and reported by all involved in implementation and delivery throughout the lifespan of the policy".

It is however clear the NHS and Integrated Joint Boards cannot reduce health inequalities entirely on their own, and the efforts to address the issue need to be made on a much wider number of fronts. We therefore recommend the Scottish Government consider assessing and monitoring all policies across all portfolios for their impact on health inequalities.

During our work on Type 2 Diabetes we were surprised to discover 24 Integrated Authorities made no mention in their strategic plans to tackle this area. Given the scale of the problem and the costs to the wider health service.

We recommend the strategic plans of all Integrated Joint boards be required to make reference to the areas for which there are obvious preventative gains to be made including specifically in tackling type 2 diabetes.

We further recommend all Health Boards, including the Special Boards, provide at least annually, a breakdown of their preventative spend showing the split between primary, secondary and tertiary. We would expect this to also include the tracking of outcomes deriving from the spend.

We have noted the differing views on the need for dual funding to allow increased investment in preventative spend without a reduction in reactive budgets. We would welcome an update from the Scottish Government on their current position about how this can be achieved and we recommend targets are set for all Health Boards and IJBs in relation to the minimum percentage of preventative spend to be achieved in each of the next 5 years.

Those successfully introducing new ways of working must be incentivised appropriately. We recommend direction is given by the Scottish Government to address the disincentives we heard about preventing new ways of working, efficiencies and innovation, being introduced.

In our scrutiny to date of the Health Boards and IJBs we have been disappointed at the lack of a longer term focus and strategic direction to increase preventative action. We expect this to be addressed explicitly in all future Board and IJB annual reports with appropriate measures put in place to measure achievements and spend. We ask the Scottish Government to identify appropriate resources to address and monitor this recommendation.

We ask the Scottish Government to report on whether they consider there is a need for legislation to drive the change to preventative spend as was undertaken for the Fire Service.

Annex A - Minutes of meeting

3rd Meeting, 2017 (Session 5) Tuesday 31 January 2017

6. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered and agreed its approach to its inquiry.

8th Meeting, 2017 (Session 5) Tuesday 21 March 2017

2. Preventative Agenda: The Committee took evidence from—

Neil Craig, Principal Public Health Advisor, NHS Health Scotland;

Dr Eleanor Hothersall, Consultant in Public Health and Honorary Senior Clinical Lecturer, NHS Tayside;

Professor David Bell, Professor of Economics, University of Stirling;

Professor Gerry McCartney, Consultant in Public Health, NHS Health Scotland;

Eibhlin McHugh, Chief Officer, and Mairi Simpson, Public Health Practitioner, Midlothian Integration Joint Board;

Fraser McKinlay, Director of Performance Audit, Audit Scotland;

Professor Damien McElvenny, Principal Epidemiologist, Institute of Occupational Medicine.

4. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered the main themes arising from the oral evidence heard earlier in the meeting and in the written evidence received.

9th Meeting, 2017 (Session 5) Tuesday 28 March 2017

6. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered and agreed a draft chamber debate motion.

12th Meeting, 2017 (Session 5) Tuesday 9 May 2017

1. Preventative Agenda: The Committee took evidence from—

Dr Una MacFadyen, Consultant Paediatrician at Forth Valley Royal Hospital, a Fellow of the College and member of College Council, Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh;

Emilia Crighton, Head of Health Services Public Health, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde;

Dr Margaret McCartney, General Practitioner;

Dr Helene Irvine, Consultant in Public Health Medicine.

6. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered the oral evidence heard earlier in the meeting.

23rd Meeting, 2017 (Session 5) Tuesday 24 October 2017

3. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered its approach to the inquiry.

28th Meeting, 2017 (Session 5) Tuesday 28 November 2017

7. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered and agreed its approach to its inquiry.

31st Meeting, 2017 (Session 5) Tuesday 19 December 2017

2. Preventative Agenda: The Committee took evidence on type 2 diabetes from—

Brian Kennon, Chair of Scottish Diabetes Group and of National Managed Clinical Network, and Consultant Diabetologist;

Andrew Job, Secretary, Edinburgh Local Support Group, and Linda McGlynn, Regional Engagement Manager, Diabetes Scotland;

Alison Cockburn, Lead Diabetes Cardiovascular Risk/Lead Antimicrobial Pharmacist, NHS Lothian;

and then from—

Dr Lynne Douglas, Steering Group member, Obesity Action Scotland, and Director of Allied Health Professionals, NHS Lothian;

Pete Ritchie, Co-Convener, Scottish Food Coalition, and Director, Nourish Scotland;

Heather Peace, Head of Public Health Nutrition, Food Standards Scotland;

Professor Falko Sniehotta, Professor Behavioural Medicine and Health Psychology, Newcastle University;

Alison Diamond, Chair of Prevention sub-group, Scottish Diabetes Group, and Lead: Lothian Weight Management Service, Diabetes and Metabolic Dietician, NHS Lothian.

Brian Whittle and Emma Harper declared relevant interests. Full details of which can be found in the Official Report of the meeting.

3. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered the evidence heard earlier in the session.

3rd Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 23 January 2018

2. Preventative Agenda: Alex Cole-Hamilton made a declaration of interest, the full details of which can be viewed in the Official Report of the meeting.

The Committee took evidence on sexual health, blood-borne viruses and HIV from—

George Valiotis, Chief Executive Officer, HIV Scotland;

Petra Wright, Scottish Officer, The Hepatitis C Trust;

Professor David Goldberg, Consultant Epidemiologist, BBV/STI team, Health Protection Scotland;

Dr Emilia Crighton, Consultant in Public Health, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde;

Mildred Zimunya, Senior Manager, Glasgow, Waverley Care;

Professor John Dillon, Consultant Hepatologist, NHS Tayside, Chair of HCV Clinical Leads Network, Professor of Hepatology & Gastroenterology, University of Dundee;

Dr Ken Oates, Consultant in Public Health Medicine and Executive lead for BBVs, NHS Highland;

Dr Duncan McCormick, Consultant in Public Health Medicine, NHS Lothian.

4. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered the evidence heard earlier in the session and agreed to write to the Scottish Government.

4th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 30 January 2018

2. Preventative Agenda: Members provided feedback on recent visits within their constituencies in relation to the session on substance misuse.

3. Preventative Agenda: The Committee took evidence on substance misuse, in a roundtable format, from—

Lorna Holmes, Head of Services, Cyrenians;

John McKenzie, Chief Superintendent, Specialist Crime Division, Head of Safer Communities, Police Scotland;

Dharmacarini Kuladharini, Chief Executive, Scottish Recovery Consortium;

Fiona Moss, Glasgow City Alcohol and Drug Partnership, Head of Health Improvement and Equalities, Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership;

Dr Carole Hunter, Lead Pharmacist, Addiction Services, Alcohol and Drug Recovery Services, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde;

Dr Craig Sayers, representative for Scotland, RCGP Secure Environment Group;

and then from—

Dr Adam Brodie, Faculty of Addictions Psychiatry, Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland;

Teresa Medhurst, Director of Strategy and Innovation, Scottish Prison Service;

Emma Crawshaw, Chief Executive Officer, Crew 2000 Scotland;

Andrew Horne, Director, Addaction Scotland;

David Liddell, Chief Executive Officer, Scottish Drugs Forum.

4. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered the evidence heard earlier in the meeting and agreed to write to the Scottish Government.

5. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered and agreed a draft letter on Type 2 diabetes to the Scottish Government.

5th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 6 February 2018

1. Preventative Agenda: The Committee took evidence on Detect Cancer Early from—

Euan Paterson, Executive Officer (Professional Development), Royal College of General Practitioners (Scotland);

Dr Christine Campbell, Reader in Cancer and Primary Care, Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh;

Professor Annie Anderson, Co-Director of the Scottish Cancer Prevention Network, and Professor of Public Health Nutrition, The University of Dundee;

Professor Bob Steele, Co-Director of the Scottish Cancer Prevention Network, and Senior Research Professor, The University of Dundee;

Dr David Morrison, Director of the Scottish Cancer Registry and Hon. Clinical Associate Professor, Consultant in Public Health Medicine, NHS National Services Scotland;

Gregor McNie, Head of External Affairs, Devolved Nations, Cancer Research UK;

Janice Preston, Head of Services, Macmillan Cancer Support in Scotland.

3. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered the evidence heard earlier in the meeting and agreed to write to the Scottish Government.

6th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 20 February 2018

3. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered and agreed a draft letter on sexual health, blood-borne viruses and HIV.

7th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 27 February 2018

4. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered a draft letter on substance misuse and agreed to consider a further draft at next week's meeting.

8th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 6 March 2018

4. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered and agreed a revised draft letter on substance misuse.

5. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered and agreed a draft letter on detect cancer early.

11th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 27 March 2018

1. Preventative Agenda: The Committee took evidence on neurological conditions from—

Pamela Mackenzie, Director of Neurological Services and Scotland, Sue Ryder;

Tanith Muller, Vice Chair, Neurological Alliance of Scotland;

Professor Malcolm Macleod, Professor of Neurology & Translational Neuroscience, The University of Edinburgh, and Clinical Lead for Neurology, NHS Forth Valley;

Dr John Paul Leach, Consultant Neurologist, representing the Association of British Neurologists (Council Member 2015-19);

Mairi O'Keefe, Chief Executive Officer, Leuchie House.

2. Preventative Agenda (in private): The Committee considered the evidence heard earlier in the session.

12th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 17 April 2018

1. Preventative Agenda: The Committee took evidence, in a round table format, on clean air from—

Claire Shanks, Policy and Public Affairs Officer (Scotland), British Lung Foundation;

Olivia Allen, Policy Officer, Asthma UK;

Jane-Claire Judson, Chief Executive, Chest Heart & Stroke Scotland;

Professor David Newby, British Heart Foundation John Wheatley Chair of Cardiology, The University of Edinburgh;