Finance and Public Administration Committee

Budget Scrutiny 2024-25

Introduction

The Scottish Budget 2024-251 was published on 19 December 2023 and sets out the Scottish Government’s proposed tax and spending plans for the next financial year. It is accompanied by the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s (SFC’s) latest set of forecasts2 for the economy, tax revenues, and social security spending which, alongside forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR)3, informs the overall size of the Budget for 2024-25.

For 2024-25, the SFC forecasts slow and fragile growth in both GDPi and real disposable income, with interest rate rises expected to continue to affect households and the economy, and inflation likely to stay higher than previously expected. Indeed, latest data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS)4 shows unexpected inflationii rises of 4% in the 12 months to December 2023, the first time the rate has increased since February 2023.

This report sets out the Finance and Public Administration Committee’s findings from our scrutiny of the Scottish Budget 2024-25. Our starting point is our Pre-Budget 2024-25 Report on the Sustainability of Scotland’s Public Finances5, which outlined the Committee’s concerns regarding the Scottish Government’s lack of long-term financial planning, affordability of spending decisions, and the absence of an overall strategic purpose and objectives for its public service reform programme. The evidence we have gathered during our budget scrutiny this year shows little sign of progress in these areas. The Committee also remains to be convinced that the Scottish Government has taken a strategic approach to targeting spend towards its three key Missions of Equality, Opportunity and Community as intended. This report provides further details of our thinking on these issues.

The report also reflects our consideration of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body’s (SPCB’s) Proposal for 2024-25, as required under the Session 6 Agreement between the Committee and the SPCB6.

The Committee was supported in our scrutiny of the Scottish Budget 2024-25 by our adviser, Professor Mairi Spowage, and by the Financial Scrutiny Unit in the Scottish Parliament’s Information Centre (SPICe). We thank them for their support. We also appreciate our witnesses taking the time to provide valuable evidence, which has helped shape our findings and recommendations.

Economic conditions

The economic context for this Scottish Budget is a story of essentially no growth over the course of 2023. The latest data for Scotland published in October 20231 shows zero growth from January to October 2023 compared to 2022 levels, and the expectation was that this would persist for the remaining months of that year. On a more positive note, many analysts this time last year were expecting that Scotland would experience a technical recession during 2023, which has not materialised.

Inflation has remained higher for longer than was expected at the start of the year, although the UK Government’s target to halve inflation by the end of 2023 was met. However, as noted above, the latest data confounded expectations to show a slight inflationary rise, from 3.9% to 4.0%. This uptick has been driven by increases in alcohol and tobacco prices, transport (particularly car repairs) and concert and event prices. This is offset by decreases in food price inflation, although this is still running at 8%.

Importantly, from the perspective of the impact on interest rates, services inflation remains higher than the headline rate, linked to historically high earnings growth. Both of these factors, along with disruption to international trade flows over the past couple of months, may, our Budget Adviser suggests, lead the Bank of England to be more cautious than many analysts are hoping on interest rate cuts. However, there is still an expectation that rates have peaked and that they will start to come down over the course of 2024.

Consumer sentiment, as measured by the Scottish Consumer Sentiment Indicator2, while weak compared to pre-pandemic levels, has improved for the third quarter in a row. Our Budget Adviser notes that, despite the severe cost-of-living crisis still impacting most households, this slow but persistent movement towards positive territory for household finance and spending measures is an encouraging sign for the year ahead. Business sentiment is, she further notes, also improving, with most businesses expecting that there will be an increase in activity over the first half of 2024.

UK context

Office for Budget Responsibility’s Economic and Fiscal Outlook: November 2023

The OBR published its Economic and fiscal outlook: November 20231 alongside the UK Autumn Statement2. These five-year forecasts highlight that—

The economy recovered more fully from the pandemic and weathered the energy price shock better than anticipated.

Inflation is expected to remain higher for longer, taking until the second quarter of 2025 to return to the 2% Bank of England target, more than a year later than forecast in March.

This domestically driven inflation increases nominal tax revenues compared to the OBR’s March 2023 forecasts, however “it also raises the cost of welfare benefits, and higher interest rates raise the cost of servicing the Government’s debts”.

The Chancellor meets his target to deliver debt falling as a share of GDP in five years’ time “by an enhanced margin of £13 billion, but mainly thanks to the rolling nature of the rule giving him an extra year to get there”.

The tax burden rises in each of the next five years to a post-war high of 38% of GDP.

The OBR has revised down its estimate of the medium-term potential growth rate of the economy to 1.6% from 1.8% in March, “largely driven by a weaker forecast for average hours per worker, which we now expect to fall in the medium term, rather than holding flat”.

Unemployment is forecast to rise to 1.6 million people (4.6% of the labour force) in the second quarter of 2025, around 85,000 people higher, and a year later, than expected in March.

Living standardsi are forecast to be 3% lower in 2024-25 than their pre-pandemic level.

UK Government’s Autumn Statement

The Chancellor of the Exchequer, The Rt Hon Jeremy Hunt MP, labelled his Autumn Statement on 22 November 20231 as an “autumn statement for growth”, suggesting that the package includes “110 growth measures”. The Chancellor explained his announcements are focused on five areas: “reducing debt; cutting tax and rewarding hard work; backing British business; building domestic and sustainable energy; and delivering world-class education”. He indicated that, due to “difficult decisions we have taken in the last year”, the fiscal situation now allowed him to deliver a package of tax cuts to support growth.

Key tax measures announced include reduced national insurance contributions, permanent full expensing of plant and machinery investment costsi, extending business rates relief for retail, hospitality and leisure sectors in England, an alcohol duty freeze until 1 August 2024, and tobacco duty increases. The Chancellor’s spending announcements include increases to universal credit in line with inflation (September 2023 figures) and the state pension in April 2024 by 8.5% in line with annual earnings growth for May to July 2023. He is also increasing the national living wage from 1 April 2024 by 9.8% to £11.44 an hour for eligible workers across the UK aged 21 and over and announced £80 million for the expansion of the Levelling Up Partnership programme to Scotlandii.

The Chancellor reaffirmed the UK Government’s commitment set out in the Spring Budget 2023 that, from 2025-26, planned departmental resource spending will continue to grow at 1% a year on average and that public sector capital spending will be frozen in cash terms. The House of Lords Library states in its briefing on the Autumn Statement2 that these spending targets “imply real terms spending reductions for ‘unprotected’ departments” from 2025-26 onwards. It highlights OBR estimates that the spending of unprotected departments would need to fall by 2.3% a year in real terms from 2025-26, increasing to 4.1% a year, should the UK Government continue with its ambition to increase defence spending to 2.5% of GDP and return overseas development assistance to its 0.7% of gross national income target.

According to the Chancellor, the Scottish Government is receiving £545 million in additional funding “as a result of decisions at the Autumn Statement”.

During evidence on 12 December 20233, the OBR noted that the “real spending power of Government departments in England goes down by about £19 billion over the forecast period” due to the Chancellor leaving public service spending plans unchanged in cash terms, despite a higher forecast for inflation”. The implication for Scotland, he suggested, is that “if those spending plans are sustained, there will be fewer real increases in Barnett consequentials for Scottish departments because in practice less is being spent in real terms on health, education, transport and other areas where spending is devolved here in Scotland”.

On the UK Government’s decision to freeze total capital spending, the OBR stated that “the Government has not set any detailed spending plans beyond next year [and so] it is not really possible for us to say what the implications are for public investment in the UK”. He went on to say that “capital spending has increased as a share of GDP over the past few years, but it is expected to fall back down again over the forecast period if it is frozen in cash terms”, adding “if such freezes were to be maintained over a long period, we would expect that to have a negative impact on economic growth over the longer term”.

The Chancellor has recently announced that the UK Spring Budget will take place on Wednesday 6 March 20244.

Scottish Fiscal Commission’s Economic and Fiscal Forecasts – December 2023

The SFC’s Economic and Fiscal Forecasts – December 20231 were published alongside the Scottish Government’s Budget 2024-25 on 19 December 2023. The outlook for the Scottish economy is largely unchanged since its December 2022 and May 2023 Forecasts, “with a slightly less negative picture for 2023-24 compared to a year ago”. It has revised up its forecast of real disposable income per person, however, the drop in living standards of 2.7% between 2021-22 and 2023-24 is “the largest reduction in living standards since Scottish records began in 1998”. The SFC forecasts “slow and fragile growth in GDP and real disposable income per person, as the recent rises in interest rates continue to weigh on household incomes and the economy, with inflation also likely to stay higher for longer than we assumed previously”.

The SFC notes that UK Government funding through the Block Grant has increased by £318m. Total funding in the 2024-25 Scottish Budget is £1.3bn higher than in 2023-24, a rise of 0.9% in real terms. While resource funding is expected to increase by £1.5bn, capital funding is set to fall by £173m in 2024-25, largely due to the reduced capital budgets applied by the UK Government.

The SFC explains that “most of the increase in resource spending is due to the improved income tax net position”. This increase of £1.2bn since the SFC’s May 2023 Forecasts is explained as being due to inflation and higher earnings growth resulting in increased income tax revenues. The SFC said it has “no strong reasons” to believe that the data it is using is either significantly under or overestimating Scottish tax revenues. However, there are risks and uncertainties, including Real Time Information (RTI) being an “imperfect predictor” of outturn data and a lack of information on self-assessment tax revenues. There are, it notes, similar uncertainties in the OBR’s forecasts of UK income tax revenues.

The SFC highlights a reduced income tax reconciliation for 2021-22 (to be applied to the 2024-25 Budget). This now stands at -£390m, a reduction from the figure forecast in May 2023 of -£712m. This, the SFC explains, is partly offset by positive reconciliations for the Block Grant Adjustments (BGAs) of other devolved taxes and social security, with the full reconciliation figure at -£338m. In relation to the Scotland Reserve, the SFC notes that the Scottish Government has set the 2024-25 Budget “with no assumed funding from the Scotland Reserve, as it plans to use all the available balance in the current year (2023-24)”. Any underspends arising could, it notes, be added to the Reserve and used in future years.

The SFC projects large positive reconciliations for years 2022-23 and 2023-24 as a result of revising up its estimates of the income tax net position for those years following higher than expected outturn in 2021-22 and higher than expected relative earnings growth in Scotland in 2022-23, alongside policies to raise additional revenues. As set out in the table below, a positive reconciliation for 2022-23 (to be applied to the 2025-26 budget) of £732m is forecast.

Figure 1: Outturn and indicative estimates of income tax reconciliations Collection Year 2021-22 2022-23 2023-24 Applies to Budget for 2024-25 2025-26 2026-27 Reconciliation (£m) -390* 732 502 Source: SFC

* cell refers to outturn available at time of publication.

On public sector pay, the SFC notes that increases “have a significant effect on Scottish Government spending”, with 2023-24 pay estimatedi to account for over £25bn of resource expenditure across the devolved public sector, including local government (over half of the resource budget). In the absence of the Scottish Government’s pay policy for 2024-25, the SFC has assumed average devolved public sector pay growth of 4.5% which, alongside other assumptions it has made, implies a fall in Scotland’s public sector employment from 2023-24 onwards.

In the medium-term, the SFC expects total funding (resource and capital) to increase by 4% in real terms between 2023-24 and 2028-29, however capital funding is expected to fall by 20% in real terms over the same period. It however highlights that—

Policymakers need to plan for the potential for funding from 2025-26 onwards to look quite different from the picture presented here. Due to the various funding sources and forecasts used, the outlook for the Scottish Budget is always somewhat uncertain but the high inflation environment is increasing the risk of large changes in funding. We note the current funding outlook from 2025-26 onwards has two particular elements of uncertainty: there is the risk the income tax net position provides a less positive contribution to funding than is currently projected, and at the same time UK Government spending could be higher than currently planned, increasing funding available to the Scottish Government.

Scottish Budget 2024-25

Scottish Government's approach

In her foreword to the Scottish Budget 2024-25, the Deputy First Minister explained that “in setting this budget the Scottish Government has adopted a values-based approach focused on our three Missions” for 20261. These are:

Equality: Tackling poverty and protecting people from harm,

Opportunity:A fair, green and growing economy, and

Community: Prioritising our public services.

The Deputy First Minister goes on to say that “we have been compelled to take painful and difficult decisions in order to prioritise funding in the areas which have the greatest impact on the quality of life for the people of Scotland”, adding “we make no apology for deploying the levers available to us to deliver on our values – protecting people and optimising services”.

In evidence to the Committee on 16 January 20242, the Deputy First Minister elaborated on the Scottish Government’s approach to budget-setting for 2024-25—

Our missions and values of equality, opportunity and community were the guiding principles of the budget, which is a budget to protect people as best we can, to sustain public services, to support a growing and sustainable economy, and to address the climate and nature emergencies. At the heart of the budget is our social contract with the people of Scotland, whereby those who earn more are asked to contribute a bit more, everyone can access universal services and entitlements, and those who need an extra helping hand will receive targeted additional support.

The Committee has sought during its scrutiny of the Scottish Budget 2024-25 to establish how the Scottish Government has ensured that its tax and spending plans align with its three Missions.

Taxation plans

Income tax proposals

As set out in the Scottish Budget 2024-25, the Scottish Government’s policy on income tax for 2024-25 is to—

increase the Starter and Basic rate income tax bands by inflation to £14,876 and £26,561 respectively. These rates, along with intermediate and higher and top rates, will remain unchanged,

introduce a new 45p Advanced rate band for those earning over £75,000, and

increase the Top rate of tax from 47p to 48p, paid by those earning more than £125,140.

The table below, from the SPICe briefing on the Scottish Budget 2024-251 published on 4 January 2024 sets out the proposed Scottish tax bands and thresholds, 2024-25:

Figure 2: Proposed Scottish tax bands and thresholds, 2024-25 Bands Band name Rate (%) Over £12,570* - £14,876 Starter 19 Over £14,877 - £26,561 Basic 20 Over £26,562 - £43,662 Intermediate 21 Over £43,663 - £75,000 Higher 42 Over £75,001 - £125, 140** Advanced 45 Above £125,140 Top 48 * Assumes individuals are in receipt of the standard UK personal allowance (£12,570 in 2024-25)

** Those earning more than £100,000 will see their personal allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000

The SFC forecasts that the income tax proposalsi set out in the Scottish Government’s Budget will generate revenues of £18,844m in 2024-25. As noted earlier in this report, its estimates for 2024-25 are £1.2bn higher since its May 2023 Forecasts, due to inflation and higher earnings growth resulting in increased income tax revenues. SPICe notes in its Briefing on the Scottish Budget 2024-25 that the income tax net positionii in 2024-25 is expected to be £1.4bn, and this figure is forecast to rise to £2.3bn in 2028-29, although, according to the SFC, the net position is highly sensitive to changes in its own forecasts and those of the OBR.

The Budget sets out that “Scottish income tax policy for 2024-25 will continue to build on our progressive approach to taxation, while raising additional revenue to invest in our vital public services”. The Scottish Government explains that “we have not taken our decisions on tax lightly and we recognise the challenging economic conditions that many people and businesses are facing”, adding “that is why we are asking those who are best able to contribute to pay more for a purpose”. The Scottish Government further notes SFC estimates that the decisions it has taken on income tax since 2017-18, including those in the 2024-25 Budget, will add around £1.5 billion of revenue in 2024-25 compared to the rates and bands applicable elsewhere in the UK.

Income tax: behavioural responses

The SFC forecasts that introducing the new Advanced rate and increasing the Top rate of income tax by 1p would raise £82m in 2024-25, after taking account of assumed behavioural changes. Revenues, it notes, would be £118m higher without this behavioural response. The SFC explains that “increased income tax rates may lead to some taxpayers changing their behaviour, for example, increasing contributions into a pension scheme, reducing their working hours, leaving Scotland or more aggressively pursuing tax avoidance or evasion”.

The SFC suggests that the behavioural modelling it uses, drawing from UK and international literature, is “reasonable and central”, though it cautions there will always be some uncertainty. However, the relatively small sums involved means that, even if it had under- or over-estimated the behavioural response by as much as 50%, this would not pose a significant risk to the Budget.

Asked about the approach taken by the SFC to modelling behavioural change, the Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI)1 suggested that “where things will end up is very uncertain, but the forecast is based on what is essentially the best available evidence [and] the SFC has set that out transparently”. Professor David Bell from the University of Stirling1 suggested that if income tax rates were reduced in England in the Spring Budget in March 2024, then the gap in Scotland will widen, risking an increased behavioural response. However, this move would slow the growth in income tax revenues in England, leading to a positive effect for Scotland under the Fiscal Framework.

The Scottish Government’s response to the Committee’s Pre-Budget 2024-25 Report3 highlighted a policy evaluation of its 2018-19 increases in income tax rates4 which “showed limited evidence of Scottish taxpayers lowering their taxable income in response to increasing tax rates”. The Committee notes, however, that the gap between Scottish and rest of the UK income tax liabilities has widened since 2018-19.

The Deputy First Minister later told the Committee5 that the Scottish Government has “of course, looked very carefully at the assessment from the SFC on any behavioural change, and that is factored into the net gain or benefit from the tax changes”, adding that the £82m to be raised from the Advanced rate “is not an insignificant amount”. She went on to say that HMRC is producing two separate pieces of analysis which would be available to inform SFC modelling for the 2025-26 Budget—

The first is a dataset that covers the incomes and locations of UK taxpayers over a 12-year period up to 2021-22. That looks at historic trends of intra-UK migration of taxpayers at different income levels and whether any obvious factors have impacted trends. The second expands on its 2021 empirical study on taxable income elasticities by considering responses in labour market participation and intra-UK migration to the 2018-19 income tax reform. Both pieces of work will make an important contribution to the debate.

Some witnesses also raised concerns regarding the potential for higher income tax rates to affect Scotland’s ability to attract and retain talent. The Scottish Retail Consortium (SRC), for example, suggested in written evidence6 that “the additional Advanced band and elevated rates for higher earners adds further complexity to existing income tax rules and makes it potentially more expensive and challenging for employers in Scotland to attract and retain the specialist and senior talent they need”. There is a risk, it argued, that businesses could seek to locate their highest paid roles and commercial operations outside Scotland, reducing the ability of the private sector to deliver highly paid jobs and the investment needed to grow the economy.

The Deputy First Minister was asked whether the Scottish Government was more focused on raising tax from high earners rather than broadening the tax base and, if so, what message that sends to people outside Scotland about it being an attractive place to live, work and invest. In response5, she highlighted net migration of on average 7,000 working-age people from the rest of the UK to Scotland, which she suggests adds significantly to Scotland’s workforce and is important in growing the economy. She went on to say, however, “we should not be complacent about these matters, and we keep them very much under review”.

The Committee recognises the uncertainty around potential behavioural changes arising from increased income tax levels. We therefore welcome the analysis being undertaken by HMRC to identify any behavioural trends in labour market participation and intra-UK migration arising from income tax reforms. We look forward to examining how this analysis informs future forecasts and taxation policy.

We also seek further information on how the Scottish Government is keeping under review the potential impact on business and the economy of the differential income tax policies in Scotland and the rest of the UK.

Interaction of UK and Scottish tax policies

The Committee, in its Pre-Budget 2024-25 Report1, recommended that “every effort should be made to resolve current anomalies with the UK and Scottish tax systems relating to national insurance and personal allowance” and asked that both governments “seek to mitigate future anomalies through engagement on future tax policy where appropriate”. In response2, the Scottish Government said it carefully considers the impact of such tax anomalies when determining future tax policy and suggests that the UK Government has, so far, been unwilling to engage in considering the different tax policies when setting national insurance policy.

Professor Bell told the Committee3 that the interaction between income tax and national insurance is a “massive issue” and suggested that “the UK as a whole should have addressed the bizarre ways in which the rules relating to the different elements of the overall tax structure do not integrate well together”. He suggested that the marginal rate for people earning £110,000 to £125,000 of 69.5% “is possibly the highest … in any OECD country” due to removal of personal allowance, while the FAI has previously highlighted concerns around the £43,000 to £50,000 rate where taxpayers are paying the higher rate of national insurance rather than 2%.

While complicated by the devolved systems, Professor Bell suggested there is a case to be made for income tax and national insurance rates to be reviewed together. He further noted decisions in the UK Spring Budget could add to these difficulties.

Asked how the Scottish Government takes account of the UK tax system when setting its own income tax rates, the Deputy First Minister acknowledged4 that “part of the challenge of having a hybrid system and incomplete devolution of tax powers is that anomalies exist”. She added “there are areas that rub up against the UK system in a way that is not ideal” and noted that “this will be brought into sharp focus if further tax changes are made in the Spring Budget”.

The Committee sees little evidence of either government seeking to avoid or resolve the anomalies arising from the way their tax and national insurance policies align, despite this having a significant impact on taxpayers in certain tax brackets in Scotland. We therefore repeat our calls to both governments to work together to mitigate these anomalies.

Labour market and earnings

The SFC forecasts an increase in Scotland’s unemployment rate from 3.2% in 2022-23 to 3.7% in 2023-24, compared to the OBR’s forecast for the UK of 4.3%. This divergence is due to a tighter labour market in Scotland and is reflected in higher nominal average earnings in Scotland in 2023-24.

According to the SFC, strong earnings growth, high inflation and its effects on fiscal drag, and policy changes have all supported a rising income tax net position, as shown in 2021-22 outturn data and this is set to continue into 2024-25. The SFC noted in evidence to the Committee1 that Scotland’s earnings growth is the highest of any region or nation in the UK. Possible reasons include relatively cheaper labour encouraging businesses to expand employment in Scotland, more activity than expected in the oil and gas sector, protracted slower growth in financial services in London, asymmetric effects of higher interest rates across the UK, or ongoing tightness in the labour market driven in part by Scotland’s demographics.

The SFC highlights that, from 2025-26 onwards, the net position continues to rise, driven partly by Scottish and UK policy divergence, and partly by differing forecasts of earnings growth by the SFC and OBR. There is therefore a risk to the projected income tax net position from 2025-26 if higher earnings growth in Scotland do not materialise. The table below from the SFC Forecasts show the change in income tax net position from 2021-22.

Figure 3: Income tax net position from 2021-22 Year December 2022: Income tax net position (£m) December 2023 pre-measures: Income tax net position (£m) December 2023: change (£m) December 2023 post-measures: Income tax net position (£m) December 2023 post-measures change (£m) 2021-22 -256 85* 342* 85* 342* 2022-23 -106 542 648 542 648 2023-24 325 827 502 827 502 2024-25 700 1,330 630 1,412 712 2025-26 915 1.661 746 1,749 834 2026-27 1,068 1,800 732 1,896 828 2027-28 1,332 2,075 743 2,178 846 2028-29 2,174 2,288 Source: Scottish Fiscal Commission

Figures may not sum because of rounding.

* refers to outturn available at time of publication.

The Committee explored projected earnings growth in greater detail during evidence. The FAI indicated2 that 2021-22 and 2022-23 data gives some indication that earnings in Scotland were growing more quickly but questioned whether that growth would be sustained and highlighted “a real risk” for the 2026-27 budget if the Scottish Government was to face a worse reconciliation than expected. Professor Bell too said2, “given we do not know until maybe two years later what the exact figure is, reconciliations have to be made, which can come as very unwelcome surprises”. He further noted that some of the earnings growth was due to public sector pay settlements that had been made in Scotland in advance of England and so the next accurate figures due in April 2024 will “be very interesting to see”.

During evidence to the Committee1, the SFC suggested that “because Scotland’s tax system is now really quite progressive, for every 1% by which earnings grow faster in Scotland than they do in the rest of the UK, net tax revenue will go up by £250m” and £25m more than in the rest of the UK. This, it explained, “means that we get all the strong effects of both any earnings growth and any differential earnings growth in Scotland compared with the rest of the UK”. It went on to say that “promoting earnings growth is therefore a very powerful way of driving up tax revenue in Scotland”, and so “the more we can get earnings to grow faster in Scotland, the more we can get tax revenues to grow”.

However, long-term sickness, the SFC highlights in its Forecasts, continues to be “a large and persistent reason for inactivity” and remains “a downside risk to our projection of the labour force participation rate”. It forecasts trend productivity growth of 0.6% in 2023-24 and 0.8% in 2024-25, rising to 1.1% in 2028-29, which it notes is similar to OBR Forecasts for the UK.

The Committee has a continuing interest in ways of increasing productivity, earnings and labour market participation to support economic growth and grow the tax base. In our Pre-Budget Report, we sought details of progress in delivering actions in the 10-year National Strategy for Economic Transformation, which the Scottish Government has cited as being key to achieving improvements in these areas. The Scottish Government’s response identifies the roll-out of certain programmes and refers to its first NSET Annual Progress Report5, published in June 2023. That Report sets out future priorities including publishing a labour market participation plan, “with action to improve the wider support system for people looking to enter the labour market and stemming the flow of individuals leaving work prematurely”.

In evidence to the Committee on 12 December 20236, the IFS argued that to address the UK’s labour market challenges “first, we need a strategy for getting people who are out of work and are economically inactive into work [and] secondly, we need to know how to help those who are in work to progress, and how we can get the productivity gains that can ultimately deliver wage gains”. It commented that “we have done the latter particularly badly during the past 15 years”.

The IFS went on to highlight that the data on labour market trends “is being exposed as being quite poor”, with a substantially lower response rate to the ONS Labour Force Survey (LFS)i leading to inconsistencies between that data and HMRC’s Real Time Information (RTI). For example, “based on the LFS, Scotland seems to have had an improvement in its labour force participation and employment relative to the rest of the UK, since before the pandemic …, however, HMRC data shows that Scotland has the lowest increase in employment of any region of the UK—2.7% compared with about 4% in both England and Wales and 6% in Northern Ireland”.

This issue was also raised by Professor Bell who suggested2 “there is a question about how representative [the LFS] is and therefore how you have to weight it”. The FAI further highlighted2 that “we have no sub-UK data at the moment being published by the ONS and that is because the survey has such a low response rate as a whole that they can’t really rely on it for UK-wide numbers let alone sub-UK results”. The FAI suggested therefore that “we don’t really know the level of inactivity in Scotland”, while Professor Bell advised that “if you want to take effective policy action [on economic inactivity], you must base it on accurate data”.

The SFC Forecasts note that the “transformed LFS, which is currently being trialled with increased sample size, will be the long-term solution for providing high-quality labour market data for the UK and devolved nations from March 2024”.

In response to the evidence heard, the Deputy First Minister told the Committee9 that “average earnings in Scotland are growing faster than in the UK …, we have seen record income tax receipts, with Scottish income tax alone forecast to raise about £18.8bn in 2024-25 to help fund services [and] there are a number of indicators that show, on productivity as well, that the Scottish economy is improving its performance”.

The Committee welcomes the improved earnings growth that Scotland is currently experiencing, which is bolstering income tax revenues to support spending in these challenging financial circumstances. We, however, note the risks highlighted by the SFC and other witnesses regarding the implications for the Scottish Budget should higher earnings growth not materialise from 2025-26 onwards. We therefore seek details of how the Scottish Government is planning to mitigate the risks of significant reconciliations in future years as a result.

The Committee seeks further details of the Scottish Government’s plans to produce a labour market participation plan. This should include proposals to reduce economic inactivity and set out how the Scottish Government is engaging with business and the further and higher education sectors to ensure the plan addresses current and future skills challenges. We consider this work to be overdue and therefore ask that development of both the plan and its delivery progress at pace.

The Committee is concerned at the evidence we heard regarding the unreliability of the ONS Labour Force Survey and a lack of data at devolved nation level, due to reduced sample size. Without accurate data, governments are limited in their ability to put in place effective policy interventions to address labour market participation and economic inactivity. We therefore ask the Scottish Government what steps it is taking to encourage improvements in this area and how it will assure itself that the new survey being trialled is reliable.

Non-domestic rates

In line with a recommendation from the New Deal for Business1, the Scottish Government’s Tax Advisory Group (TAG) has been asked to “consider the role of Non-Domestic Rates (NDR) and other taxes in achieving the right balance between sustainable levels of taxation and creating a competitive environment to do business while also supporting communities”.

In relation to NDR for 2024-25, the Scottish Government has frozen the Basic Property Rate (BPR) charged to properties with a rateable value of up to and including £51,000, at 49.8p, and increased other rates by inflation. NDR reliefs are also maintained, and 100% relief will be offered to island hospitality businesses, capped at £110,000. The SFC forecasts that the cost of freezing the BPR is around £200m per year and that the increases to the intermediate and higher property rates will increase revenues by around £170m a year.

The freezing of the BPR was welcomed by the SRC, though it expressed disappointment that the rates freeze was not extended to premises liable for the intermediate and higher property rates.

In his Autumn Statement2, the Chancellor announced a one-year extension of the UK Government’s Retail, Hospitality and Leisure (RHL) relief which provides a 75% discount to businesses occupying eligible retail, hospitality and leisure properties in England, with a cap of £110,000 per business. The OBR estimated3 that this announcement generated £230m of Barnett consequentials for the Scottish Budget, however, the FAI has suggested4 that replicating this relief in Scotland would cost up to £360m “due to there being less concentration in the RHL industries in Scotland, which means relatively fewer businesses affected by the cap”.

The SRC argued5 that this decision is a “regrettable omission, more so as … Barnett consequentials were forthcoming” and noted that Scottish businesses had already missed out on 18 months of this relief. The FSB told the Committee on 9 January 2024 6that passing on the 75% relief was one of its “big asks”. However, given other business reliefs in Scotland not available in England, it recognised that a lower rate might be applied, such as the 40% relief being passed on in Wales.

The Deputy First Minister explained to the Committee that freezing the poundage for the sixth year “is not an unsubstantial measure and our small business bonus goes further than anywhere else in these islands”. The Scottish Government’s targeted relief to islands hospitality businesses “is partly in recognition of the particular challenges that the hospitality sector in those communities has suffered [and] the measure will give us good evidence of the difference that supports make to the hospitality sector”. She added that discussions with the hospitality sector are continuing and that she is sympathetic to providing more support should more resources become available.

The Deputy First Minister7 informed the Committee that “had money been available in a way that did not lead to our having to make hard choices in relation to providing NDR relief and funding the health service, I would have wanted to do more for hospitality, given … challenges for the sector in the post-Covid environment”. The Committee notes concerns raised in evidence that the Barnett consequentials relating to retail, hospitality and leisure businesses in England were not passed on to Scottish businesses in full.

We welcome the Scottish Government’s plans to gather evidence on how the relief it has introduced for islands hospitality businesses is making a difference. We seek further details of how it will use this evidence to inform future decisions relating to support for the sector.

Council tax

The First Minister announced1 on 17 October 2023 that council tax bills would not increase in 2024-25, bringing “much needed financial relief to those households who are struggling in the face of rising prices”. The Scottish Government confirmed in the Scottish Budget 2024-25 that it is providing an additional £144m of funding to enable councils to freeze council tax rates. This, it explained2, is based on an above-inflation 5% rise in council tax nationally and that talks with COSLA are ongoing over how this is allocated.

Witnesses discussed the extent to which the council tax freeze is a progressive policy, the impact on local authority spend, and whether that revenue could have been better spent on other priorities, such as further increases to the Scottish Child Payment to help meet child poverty targets. On 9 January 2024, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) highlighted3 analysis from the IPPR Scotland4 that the freeze is “ineffectual” and “will do little to help the poorest households”. Professor Bell told the Committee3 “I find it difficult to justify the freezing of council tax, because, in general, it benefits better-off households”.

More broadly, the FAI suggested3 that "a question could reasonably and fairly be asked about whether some of the tax measures, as a whole, have been focused solely on equality”, noting that while higher earners are being asked to pay more income tax, people in valuable households are seeing their council tax bills frozen.

The FAI also highlighted the impact of the council tax freeze on local authority financing and spending. It explained3 “the point that we have been making ever since the freeze was announced is that in order to be able to say whether councils have been fully compensated or not, based on their behaviour in previous years, consideration needs to be given to what councils would have done otherwise”. Some councils, such as Orkney which raised council tax by 10% the previous year would only be compensated for 5% next year, while some others, which may have increased council tax by a lower amount, would gain from the approach.

As in previous years, council tax reform was highlighted as a priority by some witnesses. In response to the Committee’s conclusion in our Pre-Budget 2024-25 Report8 that “like many others, we believe that a more fundamental reform of council tax is now overdue”, the Scottish Government said9 that “the announcement of a freeze recognises the regressive impact of council tax and underlines the importance of reform”.

The Deputy First Minister explained in evidence to the Committee10 that the council tax freeze is intended to be “a one-year intervention [and] is designed as a lever to try to help relieve the pressure that household budgets continue to be under”, adding that the measure “probably has a larger impact on those on lower-to-medium incomes”.

Asked about basing the funding of the policy on a 5% increase in council tax, she restated that this is an average of the projected increases in council tax by local authorities and said it would not have been viable to base the funding on the actual amount each local authority had planned to increase council tax. She did, however, recognise that separate structural and distributional issues exist for some local authorities, such as Orkney, and said that the Scottish Government “will need to look at how it can support the council to address these”.

The Committee notes that the Scottish Government’s decision to freeze council tax for 2024-25 does not expressly target those in poverty. We therefore question how the policy aligns with the Scottish Government’s plans to prioritise spending on areas that deliver its three Missions.

The Committee seeks an update on progress with undertaking a fundamental reform of council tax to ensure fairness and develop a sustainable funding model for local authorities.

Other taxes

The Scottish Government announced that residential Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (LBTT) rates and bands would be maintained at their current levels, and that first-time buyer relief and the 6% additional dwelling supplement rate would continue. The SFC is forecasting1 £730m in LBTT revenue in 2024-25, a reduction from £813m in 2023-24, due to a fall in house prices and transactions. It does not anticipate housing prices or transactions returning to their 2022-23 levels until 2026-27. Projected LBTT revenue increases to £1,072m in 2028-29.

As noted in the Scottish Budget, the Scottish Government recently introduced legislation2 to make various amendments to LBTT, including extending timelines related to the additional dwelling supplement, and clarifying measures relating to joint buyers, inherited property and interests. We look forward to considering this statutory instrument in the coming weeks.

From 1 April 2024, the standard rate of Scottish Landfill Tax (SLfT) increases to £103.70 per tonne and the lower rate to £3.30 per tonne, in line with planned UK Landfill Tax increases. The SFC forecasts SLfT to raise £58m in 2024-25. As the policy objective of SLfT is to effect behavioural change, revenues are expected to fall over time. The SFC explains that it has seen much lower than expected revenue in the first half of 2023-24 and so it has revised down every year of its forecasts.

The Budget refers to the Aggregates Tax and Devolved Taxes Administration (Scotland) Bill3, which was introduced in the Parliament in November 2023 and, if enacted, is expected to be introduced as a new Scottish tax on 1 April 2026. Our scrutiny of the Bill starts in February this year.

Tax Advisory Group

In its Pre-Budget 2024-25 Report, the Committee welcomed establishment of the Tax Advisory Group (TAG)i as announced by the Scottish Government in its May 2023 Medium-Term Financial Strategy (MTFS)1. The Group is intended to “build on the Government’s inclusive approach to tax policymaking and will consider how best to engage with the public and other stakeholders on the future direction of tax policy, including whether a ‘national conversation’ on tax is required”. The Scottish Government’s response to the Committee’s Pre-Budget 2024-25 Report2 notes that its Strategy for Tax in Scotland which will be published alongside the 2024 MTFS “will build on the core tax principles published in the Framework for Tax in 20213, as well as setting out how we will further develop our evidence and evaluation of the tax system to support sound tax policy-making”.

Both the MTFS and the June 2023 announcement4 on the role and membership of the TAG stated that “the outcomes of this engagement will feed into the Budget 2024-25 and the development of the Government’s longer-term tax strategy”. However, the budget document does not mention any input from the TAG to the tax policy decisions made by the Scottish Government for 2024-25. The Committee therefore sought clarification from the Deputy First Minister on this issue. She explained to the Committee5 that the Group was “never intended to provide an input to each budget” and was instead looking beyond year-to-year budget horizons and at the long-term strategy for taxation.

The Committee seeks clarity regarding the Deputy First Minister’s comments that the Tax Advisory Group was never intended to provide input to each budget, when previous Scottish Government announcements were clear that the outcomes from this work would feed into the Scottish Budget 2024-25.

We also request an update on the TAG’s work and confirmation that the new Strategy for Taxation is on course to be published in May 2024 as planned, particularly given our previous recommendation that “it is imperative that this work progresses at pace”.

Spending plans

Spending plans: overview

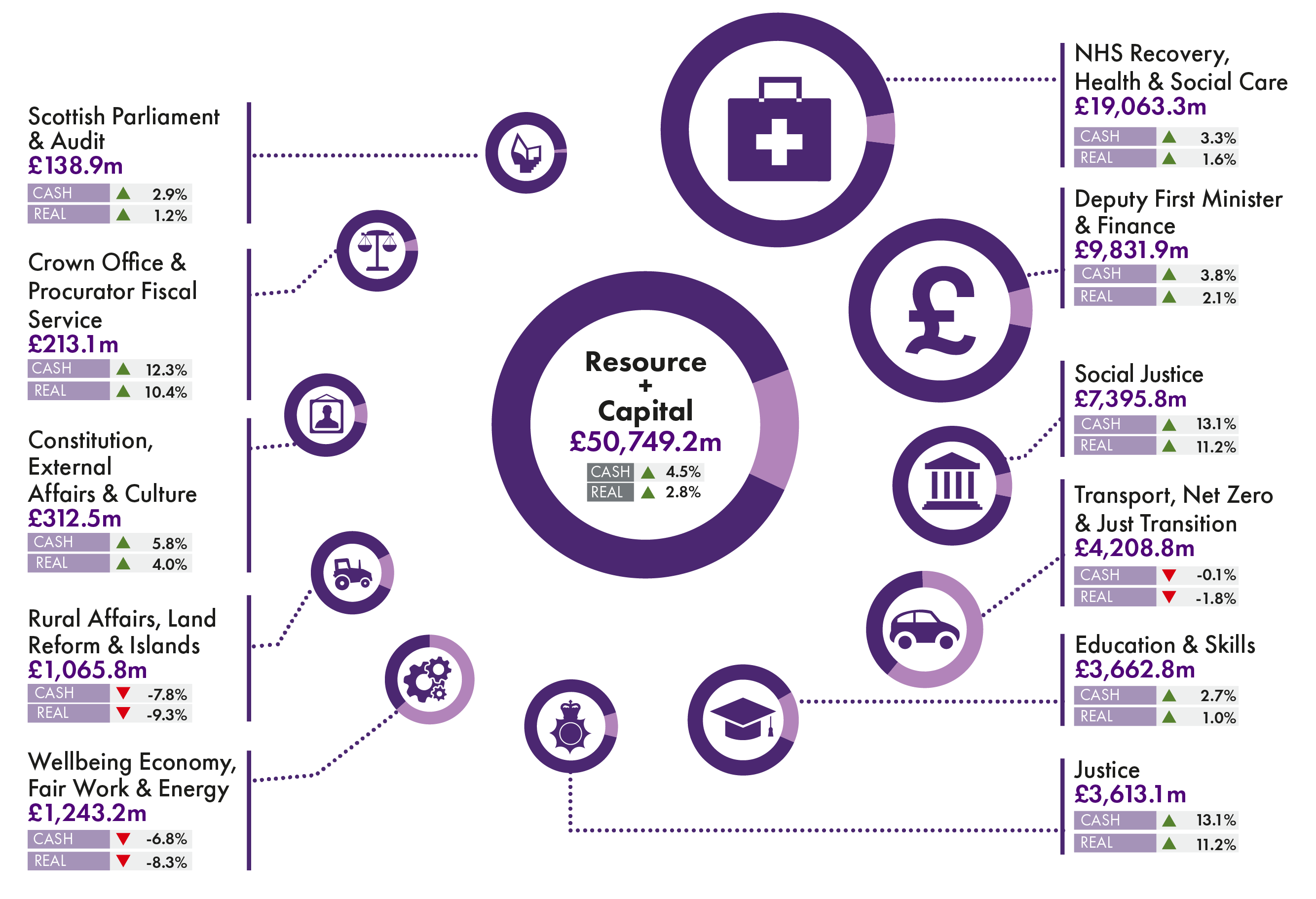

As noted in the SPICe briefing on the Scottish Budget 2024-251, eight portfolios increase in both cash and real terms, with the largest real terms percentage increases in Social Justice (which includes social security spending) and Justice – both see increases of 11.2% in real terms. The NHS, Health and Social Care portfolio benefit from an increase of 1.6% in real terms on 2023-24 figures.

The Wellbeing Economy, Fair Work and Energy (WEFWE), the Rural Affairs, Land Reform and Islands (RALRI), and Transport, Net Zero and Just Transition (TNZJT) portfolios see real terms spending reductions, with RALRI facing the largest percentage fall of 9.3% in real terms.

The SPICe briefing includes the Figure below showing fiscal resource and capital, including financial transactions, by portfolio for 2024-25 compared with the Budget agreed in the Budget Bill for 2023-24.

Social Security spending

The Scottish Government announced that it is providing £6.3bn for social security payments, an increase of almost £1bn on 2023-24 figures. This includes increasing the Scottish Child Payment in line with inflation. The Scottish Budget 2024-251 states that the Scottish Government is—

… committed to delivering new Scottish Government social security benefits, including Pension Age Disability Payment and Pension Age Winter Heating Payment, in addition to the 14 new benefits already being delivered by Social Security Scotland, while progressing the national roll-out of Carer Support Payment, and ensuring people receiving benefits are treated with dignity, fairness and respect.

The SFC told the Committee2 that it is expecting spending on social security to rise from £6.3 billion in 2024-25 to £8 billion at the end of the forecast period (2028-29). It expects social security spend to be £1.1 billion above the Block Grant Adjustment (BGA)i next year and to rise to £1.5 billion more than the BGA by the end of the forecast period. The SFC explains that around half of the difference by 2028-29 is from new payments and the other half is from “what we think are changes in behaviours and the different type of system that is running ahead of the equivalent system that exists in England and Wales”. The SFC, in its Fiscal Sustainability Report3 published in March 2023, projects that social security spending will reach £13bn in 2072-73, when there is a projected budget gap of £1.5bn.

The impact of this significant planned uplift in social security spend on other areas of the resource budget was explored by witnesses. The JRF4 favours the Scottish Government’s approach to welfare over that of the UK Government and welcomed the protection of schemes such as the Scottish Child Payment, while the SFC2 noted that the Scottish Government has limited ability to make changes to the level of social security spend each year until and unless it reforms its policy.

The Committee explored the sustainability of the Scottish Government’s social security polices with witnesses. We heard from Professor Bell4 that “social security is a valid priority [however], it comes with financial consequences” and the Scottish Government “will have to be upfront about what it is that it will cut in order to fund the additional social security payments”. The SFC2 suggested that “there is little space for new spending once we take account of pressures such as the ongoing consequences of changes to devolved social security payments and the linking of payment rates to inflation”, while the FAI4 further highlighted that prioritisation of social security (as well as health spending) “has come at a cost [and] it is for the Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament to assess whether that is a worthwhile cost”.

The Deputy First Minister told the Committee9 that social security “has now become a key pillar of spend by the Scottish Government and, it will undoubtedly help to support the most vulnerable”, adding that she views the increase in Scottish Child Payment “as an investment in people that has arisen from a conscious and political choice”. She further recognised “it is the right investment for the right reasons, but we are very aware of the need to ensure … that the investment in social security is sustainable”.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government how it will continue to assess the long-term affordability and sustainability of its social security policies and their impact on other areas of spend, particularly in light of the demographic challenges highlighted by the Scottish Fiscal Commission in its 2023 Fiscal Sustainability Report.

Developing and retaining the workforce

The need to retain, and attract skills to, Scotland as a key element of growing the economy was raised during both Pre-Budget and Budget scrutiny. We previously sought information from the Scottish Government on the steps it is taking to ensure that Scotland can retain the graduates it educates. In response, the Scottish Government referred to talent attraction and retention as forming a key strand of its ambitions to establish Scotland as a rapidly growing start-up economy and provided examples of showcasing Scottish companies around the world, which it states has been successful in increasing interest in Scotland from investors and entrepreneurs1. It further noted that the 2024-25 Budget provides scope to expand the Techscaler network, “delivering world class incubation and commercial education to Scottish start-ups”. The Scottish Government later announced £9m to expand its Techscaler programme as part of the Scottish Budget 2024-25.

However, Professor David Bell2 argued that this is “not a great budget in terms of [the Scottish Government’s ‘Opportunity’ Mission and “ostensibly it doesn’t look like the budget particularly favours economic growth”, a view shared by the FAI. They both suggested that reduced budgets for the Scottish Funding Council, Employability, the Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB) and enterprise agencies, as well as the reduced capital budget, could impact on inward investment, business growth, and the ability to develop skills in ‘green’ and high-wage jobs and to retrain people to return to the workplace. Potential impacts on delivery of the NSET are also unclear.

Cuts to the Scottish Funding Council budget were noted as an area of particular concern by witnesses. The FAI2 said it was surprised by this decision given “training people for highly-skilled occupations and green jobs in the future growing economy should be a priority”, while Professor Bell2 suggested that “we are not good at retraining people who have become inactive, for whatever reason, to re-join the labour market [and] colleges can play a hugely positive role in that respect”. According to Colleges Scotland2, the college sector has seen the equivalent of a 5% cut in its budget, yet the sector delivers on all three of the Scottish Government’s priority Missions. It went on say that “colleges provide the fabric to support the economy, our communities and the people in them [and … give] people opportunities, as well as hope, skills and work”.

In its written submission6, Universities Scotland (US) highlighted cuts of £28.5m (resource) to the university sector and called for additional funding to be found “to protect the university teaching grant as far as possible in the interests of Scottish students”. It goes on to highlight that the Scottish Government is expecting additional savings to be made in the higher education sector including from reducing first-year university places. Universities Scotland suggest that savings of around £4-5m from removing the temporary additional funded places created to address the consequence of teacher-assessed Highers during the Covid pandemic should be “reinvested in the unit of teaching resource for other home students”. It also highlighted a “misconception” that universities can “make up for chronic underinvestment in the level of resource per Scottish student because of an ability to cross-subsidise from international student fees”. US went on to say that not all universities have a high proportion of international students, although those that do may be affected by “major headwinds affecting international recruitment”.

Professor Bell suggested2 that the Scottish Government needs to “concentrate more on arguing the case on how the budget supports growth”, for example, increases in the health budget and disability payments may help people return to work or contribute to the community in other ways.

The Deputy First Minister told the Committee8 that “growth is a priority” and reiterated “we have had to make some very difficult decisions on where we make the investments”, adding for example, “we need our enterprise agencies to focus on the key priorities, so there will be things that they are not able to do”. On employability, she argued that “where employability funding has been reduced, whether it is through the in-year savings this year or last year, that has been an unfortunate consequence of the pressure on Scottish Government budgets”. She explained in relation to university places that discussions are ongoing around what the university sector will deliver and are not yet concluded and confirmed that the Scottish Government is unable to sustain the funding of the 1,200 additional places that arose during the Covid pandemic. It is understood that this accounts for approximately £5m of the £28.5m reduction to the universities budget.

The Committee is unclear, in light of spending cuts to further and higher education, enterprise agencies and employability, how the Scottish Government has, as intended, prioritised its spending towards supporting the delivery of a fair green and growing economy .

The Committee also notes from the Deputy First Minister’s evidence that bodies, such as enterprise agencies, will be expected to focus their efforts on key priorities. We therefore seek further details of how the Scottish Government is assessing the impact on economic growth of the withdrawal of some of their services and support.

Professor Bell2 highlighted that the fall in agricultural support (of £33.2m) poses particular challenges for crofters who receive a higher proportion of their income from the state. The Deputy First Minister was asked8 about the impact on rural areas of this reduction in funding, along with cuts of £3.5m to the land reform budget, £33.6m to forestry budget and £6.9m to the overall marine budget. She responded that “it is a tough budget but we have tried to prioritise the sector’s priorities within that” and “we will continue to support people who are farming and crofting in our most remote and fragile areas through £65m for the less favoured areas scheme in 2024-25—we are the only country in the UK to provide that vital support”.

Capital budget

The SFC forecasts that capital spending is set to fall by 4% in real terms between 2023-24 and 2024-25, and by 20% in real terms between 2023-24 and 2028-29. The Scottish Government plans to make full use of its increased capital borrowing powers (of £458m) under the updated Fiscal Framework to support capital investment in 2024-25i and will consider accessing alternative sources of capital borrowing in future. The SFC explained to the Committee on 20 December1 that “the key factor that drives the fall in capital is the block grant”, and while the Scottish Government “might do some borrowing around the edges, … the big money comes mostly from the block grant”.

In its 2023 MTFS2, the Scottish Government stated that as part of a prioritisation exercise in advance of the 2024-25 Budget, “we will prioritise capital spending which supports employment and the economy through the Scottish Government’s infrastructure plans, and which has greatest impact on realising our three Missions”.

The Scottish Government’s Budget 2024-253 highlights that, while its £6.25bn capital budget will “continue to be invested across a range of high priority areas to help maintain high-quality public services and achieve a just transition to a net zero economy …, delivering on our medium-term capital ambitions will not be easy”. This is a larger cut than it had modelled for and “means that it will take longer to deliver all our planned capital projects and programmes – unless the UK Government changes course and increases its investment in capital programmes”.

Professor Bell agreed4 that the extent of the reductions to the capital budget announced in the UK Government’s Autumn Statement “came as a surprise” and argued that both governments “should be increasing capital spending on public infrastructure” to support business and incomes. The SFC1 made a similar point—

Speaking as economists, we feel that, if capital investment is spent wisely, it can have a huge impact on the economy. It connects communities and means that businesses can become more productive and that connectivity both within the UK and outside it can be better. Therefore, all the evidence points to capital investment being a really important part of economic growth in the long run.

The FAI4 also expressed concerns regarding the impact of low investment on growth, suggesting that “investment and capital per worker is one of the big drivers of economic growth in the long run”. It, however, acknowledged that the Scottish Government is limited within its current framework, other than to decide how to allocate the capital budget it has been given.

The Deputy First Minister responded7 to the evidence heard by saying “our capital investment is geared to try to use public capital in a strategic way that levers in private investment” critical to economic performance.

The Committee is disappointed that reductions in capital funding available to the Scottish Government continue. We urge a change in policy in the UK Spring Budget to enable more investment in infrastructure to stimulate economic growth.

We also seek further information from the Scottish Government on the steps it is taking to use the limited capital spend it has in a strategic way that levers in private investment, as highlighted by the Deputy First Minister in evidence, and how it will measure success in this area.

The SPICe briefing on the Scottish Budget 2024-258 states that—

The wider reductions to the capital budget are … seen in the Affordable Housing Supply Programme (AHSP) budget. This is being reduced by 27% in real terms in 2024-25. It is unclear how this will affect the Scottish Government's commitment to complete 110,000 affordable homes by 2032 and to invest £3.5 billion in the AHSP this parliamentary term.

A number of witnesses highlighted specific concerns regarding the impact of these cuts, including the JRF4, which suggested the reduction “is brutal in the context of the housing situation in this country”. It went on to say that there is a significant risk that the Budget could lead to a rise in poverty, particularly due to the cuts in the affordable housing budget and highlighted “no joined-up thinking” overall—"it feels as though the affordable housing budget was cut because something had to be cut”.

The FAI4 further argued it is “hard to see how the cuts to the house-building budget and affordable housing supply budget square with the Scottish Government’s stated priority to increase the housing supply”. It acknowledged other types of housing and investment but argued that affordable housing “will have more impact, as it will allow affordability to perpetuate through the system”.

Asked why the Scottish Government had prioritised capital spend in the Police Scotland and digital connectivity budgets over affordable housing, the Deputy First Minister explained7 that required projects are being funded. She went on to explain that the housing budget has traditionally been the recipient of financial transactions, which have dramatically reduced, and “we have had to deploy the £176m of financial transactions that we do have to the Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB), in order to maintain its capability”.

The Deputy First Minister indicated that this was one of the most difficult decisions taken in this Budget and that, if the availability of capital funding changes, the housing budget would be her number one priority. Asked about the impact on the Scottish Government’s target of having in place 110,000 affordable homes by 2032, the Deputy First Minister said that 14% of the target had been delivered so far, the profiling of the target would need to change, and private investment will be required to deliver the target. She also confirmed that there is “a clear appetite to invest”, particularly in mid-market rental properties.

The Committee draws the Scottish Government’s attention to the significant concerns expressed by witnesses regarding its decision to cut the affordable housing budget in view of reductions to available capital. We seek further information on the impact of this decision on its target to build 110,000 homes by 2032.

We also ask the Scottish Government to demonstrate how this decision aligns with its own spending prioritisation criteria and whether it has fully assessed the potential impact on tackling poverty and growth.

The SPICe briefing8 notes that the SNIB’s financial transactions budget reduces from £238m to £174m (net of repayments), which “is the lowest budget settlement since 2019-20 when the SNIB was launched”. Concerns were raised by witnesses regarding the impact of these cuts on various investments, including net zero. Professor Bell suggested4 that “in of itself, the bank cannot push us directly towards net zero—we need private sector investment—and with the directive that it has to support investments in that policy area, the bank can support that kind of investment”. He went on to suggest that “the cut might slow down more speculative investments in new technologies that could accelerate the move towards net zero”, adding “perhaps there are alternative funding mechanisms, but thus far the SNIB seems to be the one institution that is very clearly aimed at that particular issue”. The FSB4 had called for an increase in the investment that the SNIB makes in small businesses to encourage growth, and indicated “obviously, a cut in the budget for the Bank this year gives us a concern about whether it will be able to do that”.

NatureScot, however, said4 it could see “some positives in the budget settlement in the pivot towards supporting the nature and climate crisis”, including future statutory targets in relation to nature degradation linked to climate change.

On net zero, the Deputy First Minister was asked7 about the £69m funding for the offshore wind supply chain, including £32.9m of capital funding, which forms part of the Scottish Government’s recent commitment to spend £500m in this area. She explained that the investment was recommended by the Scottish Government’s Investor Panel, “which said that sector is the one key investment that [it] can make that will have a substantial return for the Scottish economy”. The Deputy First Minister went on to quote figures from the FAI’s The Economic Impact of Scotland’s Renewable Sector – 2023 Update17 published on 18 December 2023 showing that “Scotland is seen as a good place to invest because of that certainty of objective”. This Update also found that Scotland’s renewable energy industry and its supply chain supported more than 42,000 jobs and generated over £10.1bn of output in 2021.

The Committee recognises that overall reductions to the Scottish Government’s capital budget impacts on its ability to target funds towards achieving net zero. We seek further details of how it is mitigating these challenges, including attracting private investment, to make greater progress towards delivering a fair, green and growing economy.

The Scottish Government, in its 2023 MTFS2, stated that “to help to address the difference between the capital funding and spending outlook, we plan to publish a reset of the project pipeline … alongside the 2024-25 Budget – providing transparency over which projects may now be delivered over a longer timescale”. Its Infrastructure Investment Plan (IIP) and Capital Spending Review were both also extended by one year to 2026-27. The Committee previously committed to consider this information as part of budget scrutiny.

The updated pipeline was not published alongside the Scottish Budget 2024-25. Audit Scotland told the Committee4 that the Scottish Government is planning to undertake work on “understanding better or mapping out, how it intends to prioritise its infrastructure spending”, adding “we can say that it cannot afford to do what it originally planned to do”.

The Deputy First Minister confirmed7 that the Scottish Government would provide an update on the capital delivery of existing infrastructure at the end of January and the updated IIP would be published in the Spring following the UK Spring Budget. She added “it will be important to see what [the Spring Budget] looks like before we introduce the IIP revisions as the budget could end up impacting positively or negatively on capital”.

The Committee is not convinced of the need to wait until after the UK Spring Budget before publishing the updated infrastructure project pipeline. Regardless, the Scottish Government should have been upfront about the delay and the reasons behind it.

We seek publication of the updated project pipeline and Infrastructure Investment Plan by Easter 2024.

In 2022-23, the Crown Estate Scotland concluded the first round of the ScotWind offshore wind leasing process which enabled developers to apply for seabed rights to plan and build windfarms in Scottish waters. This round generated over £756m. The SFC highlights21 that the Scottish Government has a remaining £660m of ScotWind proceeds available to spend. The Scottish Government had planned to use £310m in 2023-24 and £350m in 2024-25 but has now decided to use £150m less in the 2024-25 Budget and deployed this funding in 2023-24. The Scottish Government will therefore have used all the income from ScotWind between 2022-23 and 2024-25.

Professor Bell argued4 that the ScotWind funds should be regarded as equivalent to a sovereign wealth fund which should be used to support future generations. He explained that “to be equitable, it should not be spent only on the generation that has been lucky enough to have that revenue gathered” and agreed with the suggestion that fiscal rules should be applied to protect the funds.

The Deputy First Minister, in response to this suggestion, said7 that “in an ideal world, where there would be no need to plug gaps in day-to-day spend, I can see the appeal of building a sovereign wealth fund with money from ScotWind”. She argued, however, that the Scottish Government had “no option but to use all the tools at our disposal”, including Scotwind revenues, in order to sustain public services. She said the Scottish Government would continue to consider the setting of fiscal rules, but “the difficulty is that, if I was sitting here with £350m unallocated in a certain fund, I imagine that there would, understandably, be calls for that money to be deployed in order to avoid some difficult decisions”.

The Committee seeks further information regarding the strategic parameters of the fiscal rules applied to ScotWind. The Committee is attracted by the concept of funding generated from sources such as ScotWind being placed in an investment fund for future generations. While we understand the challenges facing the Scottish Government in meeting day-to-day financial pressures, this is a question of long-term strategic financial planning. We, therefore, ask that the Scottish Government gives consideration to these suggestions for future leasing rounds.

Medium and long-term planning

In its 2023 MTFS1, the Scottish Government committed to publishing refreshed multi-year spending envelopes alongside the 2024-25 Budget. In our Pre-Budget 2024-25 Report2, we recommended that these should include sufficient detail to enable meaningful parliamentary scrutiny and to allow public bodies to plan ahead.

The Scottish Government has only published single-year spending plans for 2024-25. It explains3 that this is because “the nature of the Autumn Statement and the OBR’s forecasts make future prospects more volatile, and it could be misleading to plan too far ahead across the board”. It plans to “revisit the multi-year outlook” in its next MTFS in May 2024. The SFC notes4 “the Scottish Government’s argument would be that, while there is uncertainty about the net tax position and about what the UK Government might do, it can do a budget for only one year”, however, “as the independent fiscal institution, we find that disappointing and think that the Scottish Government should set out multi-year spending plans”. It went on to say that “in our role as the independent fiscal institution for Scotland we encourage the Scottish Government to plan its budgets over both the short, medium and long term”, an approach it suggests is even more important against a backdrop of uncertainty.

Witnesses told the Committee5 about the impact on their organisations of having single-year spending plans. The SCVO argued that this presents significant challenges for planning the delivery of services, staffing levels and, in some cases, can threaten the viability of voluntary organisations. Colleges Scotland said that multi-year budgets provide an ability to plan and to make much better decisions. GCC however argued that having certainty around budgets is more important than having a longer-term view and NatureScot argued that some certainty in the medium-term would help to support relationships with its partners and those bodies it funds.

While acknowledging it is difficult for the Scottish Government to produce multi-year plans in these uncertain times, the FAI suggested5 “it would be helpful to have multi-year plans that show what the [budget] gap is going forward … so that a better conversation can be had across Scottish society about what decisions will have to be made”.

The Committee notes that the Scottish Government only receives funding for one year. Nevertheless, we agree with the Scottish Fiscal Commission that the Scottish Government should set out multi-year spending plans to support planning and scrutiny. Despite the uncertainties ahead, we believe that it was possible for the Scottish Government to provide some indicative figures for future years alongside the Scottish Budget 2024-25 as intended.

We seek assurances and certainty that it will publish multi-year spending plans with the next Medium-Term Financial Strategy in May 2024.

The Committee strongly recommended in our Pre-Budget 2024-25 Report that the Scottish Government produces a full response to the SFC’s Fiscal Sustainability Report setting out the actions it will take to start addressing the longer-term challenges ahead. The Scottish Government’s response is silent on this recommendation. Asked when the Committee can expect to see this response to the report, the Deputy First Minister said7—

I will be happy to furnish the committee with that longer-term plan after the Spring Budget. The MTFS in May will be a key point at which I can set out what the medium term looks like … The point that you are looking at goes a bit beyond that, into the longer term, and … I will try to furnish the committee with as much information as possible on that at the earliest opportunity.

Concerns were raised regarding an overall lack of strategic longer-term planning. Professor Bell for example told the Committee5 that neither the UK Autumn Statement nor the Scottish Budget were “fiscal events for future generations”. He went on to highlight that the view should be long term, in particular to have plans in place to deal with sudden shocks such reconciliations, citing they “could easily cost us £1bn”. He suggested, while the latest MTFS pointed to there being a significant budget gap, decisions to address this appeared to be taken at the last minute, rather than approaching them in a more considered way. The FAI had a similar view5, highlighting that, while the Autumn Statement took place only a few weeks before the Scottish Budget, the projected shortfall was set out in May and so decisions could have been taken earlier.

The Committee remains concerned that the Scottish Government still appears to be primarily occupied with resolving immediate funding issues, with little focus on medium to long-term planning.

We are also disappointed that the Scottish Government did not respond to our strong recommendation that it produces a full response to the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s Fiscal Sustainability Report. This was a missed opportunity to demonstrate a long-term planning approach and to start to address the significant challenges ahead.

We note the assurances from the Deputy First Minister that she will provide a “longer-term plan” after the UK Spring Budget. We restate our expectation that this includes a full response to the significant future challenges set out in the SFC’s report.

We also request an update on when the Scottish Government will seek to schedule a parliamentary debate on this important report, as committed to in its response to our Pre-Budget 2024-25 Report.

Transparency

Budget comparisons

The Committee is focused on enhancing the transparency of budget documentation and welcomes the engagement it has had with the Scottish Government on these issues to date. We note the Scottish Government’s favourable response to the Committee’s recommendation that, to support transparency, it should adopt a similar approach to that of the UK Government and the SFC in comparing its Budget plans for spending with the latest estimates or outturns from the previous year’s spend.

While this information is not provided within the budget document itself, the Scottish Government has advised1 that it “recognises the need to provide this information and will set out the requested detail in an additional on-line publication in January 2024”. The Committee believes this data will provide a more accurate comparison of changes to budget lines year on year, a view supported by some witnesses we heard from during this budget process. At the time of writing, this information has not been published and could therefore not be considered as part of our budget scrutiny.

The Committee welcomes the engagement we have had with the Scottish Government to date on enhancing the transparency of budgetary information and we look forward to continuing our discussions on additional improvements that can be made.

We ask that in future years the comparison of its spending plans with the latest estimates or outturns from the previous year’s spend is published alongside the Scottish Budget, to support transparency and maximise opportunities for scrutiny.

The Scottish Government also accepted our previous recommendation, and that of the SFC, to produce budgetary information by Classification of the Functions of Government (COFOG), such as health, education, and social protection, allowing comparisons over time. This year, COFOG data was published alongside the Scottish Budget on 19 December 20232.