Finance and Public Administration Committee

Report on Public Administration - effective Scottish Government decision-making

Executive Summary

In undertaking this first Committee inquiry into Public Administration, the Committee’s report has been greatly informed by the wide range of evidence gathered from those with experience of working in the Scottish Government, those from outwith Government and the research and expertise of our Adviser, Professor Paul Cairney.

Our starting point was to consider how effective government could be defined. However, we learned that what defines an effective government is ambiguous. Government seeks to describe what it thinks effective means so that it can then articulate what its success would look like and to ensure it is seen as a ‘competent’ government. This is all within a policy making environment where decision-making has become quicker and politics more polarised.

It can make sense for Government to describe their aspirations for systematic government, or to use simple descriptions of policymaking when trying to explain their aims to the public. However, they should also describe more practical aspects of their work, so that stakeholders and citizens can understand policymaking enough to engage or make judgements on effectiveness. The reality of the policy making process is that it is complex.

The evidence we heard is that these systematic policy making aspirations are unhelpful if they encourage unrealistic expectations and therefore undermine the routine process of governments learning lessons from errors (in other words, no-one can live up to the ideals of simple models). As we heard, it is difficult to encourage reflection and learning when the primary focus is on accountability for real and potential failure. Whilst we welcome a Scottish Government commitment to ‘learn lessons’ from key choices and events, our impression is that such learning is more likely to be triggered by issues with policy delivery. Learning lessons should be part of a well-designed process in which monitoring and evaluation are routine parts of government work. Approaches elsewhere, such as the New Zealand Policy Project, provide ideas on how to pursue this type of learning agenda through systematic evaluation of the quality of advice.

Transparency was a key theme arising in evidence. We found it difficult to identify from information in the public domain how key aspects of the decision-making process and civil service governance work in practice, post devolution. For example, there remains uncertainty about how the civil service working for the Scottish Government relates to that working for the UK Government, particularly in relation to senior levels of policymaking and accountability.

As we heard, if these internal processes only make sense to a small number of policymakers, most others are then excluded from evaluating or indeed contributing towards these decision-making processes. We recommend therefore that the Civil Service and the Scottish Government clarify what its processes are, to encourage meaningful internal evaluation and engagement, and to allow Parliamentary committees to scrutinise what they actually do.

There is general agreement that transparency is essential for political accountability. However, we received different accounts of how best to deliver that broad aim, to balance the need for openness with the need to have frank discussions in private as part of effective deliberation. We heard there may also be unintended consequences to any solutions, such as the use of alternative means of communication (e.g. Whatsapp groups; in-person unrecorded meetings). Based on our learning from approaches elsewhere, we invite the Scottish Government to consider publishing much more information about Cabinet decisions as part of a journey towards greater levels of transparency.

Allied to learning lessons, standards in policy-making are needed which enable the quality of decision-making and advice to be assessed by Ministers, civil servants or those outwith Government. This is an area to which we recommend the Permanent Secretary gives significantly greater focus. Ministerial accountability is well understood; less so is how many civil service leaders are also responsible for the quality of policy and delivery. We highlight approaches in the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 and New Zealand Policy Project as mechanisms to independently assess the quality of decision-making and advice. This is an area we also plan to give further consideration to as part of our future work programme.

Whilst some aspects of policy making may stray outwith Scottish Government control, our report makes recommendations in a number of areas where we consider a more strategic approach will better support the gathering of robust evidence from a diverse range of perspectives and create more safe spaces for challenge.

We heard that policymakers should seek essential policy-relevant knowledge (including from lived experience) from as many diverse sources as possible. Whilst the Scottish Government says its approach reflects this position, we also detect a tendency for policymakers to describe almost any situation as based on the best available evidence at the time, without clarifying the processes used to gather and analyse information. The absence of a systematic process raises questions as to what types of evidence are valued which, we heard, can have a negative impact on the groups called upon for information and advice. Many describe high levels of uncertainty about how policymakers use their information rather than with the final decision made.

We recommend that the Scottish Government learns from the Wales Centre for Public Policy’s more systematic and transparent approach to gathering evidence. Its model of providing clear ground rules for engagement also supports safe spaces for challenge.

It can be challenging for government to address long-term issues given the immediacy of short-term pressures. We note that the Scottish Government is considering legislating to require longer-term thinking across public bodies. We highlight the legislative approaches used to deliver a longer-term focus in Wales and New Zealand. We also ask the Government to reflect on whether there is a role for civil servants to support long-term policy making by sharing their learning on the challenges faced, given they endure across successive governments.

Clearly, there are benefits to civil servants moving jobs within Government, including the ability to gain a wide range of relevant experiences in different policy sectors (including the wider public and private sectors). However, there are also major unintended consequences for institutional memory, skills development and stakeholder relations, and overall we heard there is too much ‘churn’ across the civil service. We also consider a greater shift is needed from generalist staff to specialists anchored to a policy area within which they can flourish should they wish to. We heard from many that policy design and delivery requires teams of people with different – general and specialist – skills, so promotion and reward criteria should reflect this mix.

The findings in our report are intended to support the Scottish Government to provide greater understanding, structure and transparency to how it takes decisions. This is important if we are to create a better informed, more nuanced and less adversarial learning environment within which we can all discuss what works well, and less well, in how the Scottish Government makes decisions.

Membership changes

During this inquiry there have been membership changes on the Committee—

Michael Marra replaced Daniel Johnson on 25 April 2023;

Keith Brown replaced Kenneth Gibson (between the following dates - 17 May 2023 and 14 June 2023).

The Committee thanks all former Members for their contribution.

Introduction

In 2021, for the first time, public administration became an explicit part of a Scottish Parliament Committee's remit when it was included as part of the new Finance and Public Administration Committee's remit. According to the handbook of teaching public administration1 it is about processes, people and performance and "has the lofty goal of implementing and managing programmes and outcomes that are equitable, well-managed, efficient and effective.”

On 6 December 2022 we launched our inquiry into effective Scottish Government decision-making, our first inquiry focussed on public administration, with the ambition to better understand the current policy decision-making process used by the Scottish Government. The inquiry also aimed to provide greater transparency to that process through our evidence gathering and reporting and to seek to identify the skills and key principles necessary to support an effective government decision-making process. Our focus was on the ‘core’ Scottish Government; that is Scottish Ministers and those that work directly for them.

To inform our inquiry we issued a call for views and received 28 submissionsand SPICe produced a summary of that evidence. We also took evidence from witnesses at Committee meetings on 28 March, 18 and 25 April, 2 and 9 May concluding, on 16 May, with evidence from the Deputy First Minister and Cabinet Secretary for Finance (the DFM) and Scottish Government officials, including the Permanent Secretary.

In addition we sought evidence from former Ministers, former special advisers, former civil servants and current civil servants through engagement events, and published summary notes of the discussions held on 28 February, 14 March, 16 March and 21 March. Overall, we received much less evidence about the roles of special advisers in Government decision-making, although there was a general view that good special advisers were considered a benefit to decision-making.2

We thank all those who have provided their views, knowledge and experiences to the Committee, all of which have informed the findings in this report. We also thank our Adviser, Professor Paul Cairney for his expertise and helpful advice throughout our inquiry and for his insightful research paper.

What is effective decision-making?

As Professor Cairney sets out in his research paper,1 key to understanding effective Scottish Government decision-making is understanding what effective government is. There is no universal definition of ‘effective Government’, so Governments provide principles to describe their ambitions to be effective such as “preventative, co-produced, coherent, evidence informed and equitable policymaking” however those principles are sometimes contradictory in practice. For example, principles of prevention and anticipatory thinking are undermined by electoral cycles which encourage short-term thinking or if national elections are highly partisan then accountability becomes focused on debating policy success or failure rather than encouraging learning. Given these contradictions, Professor Cairney considered that the principle of policy coherence in particular is not “a realistic ambition” for Governments given the way they are set up.2

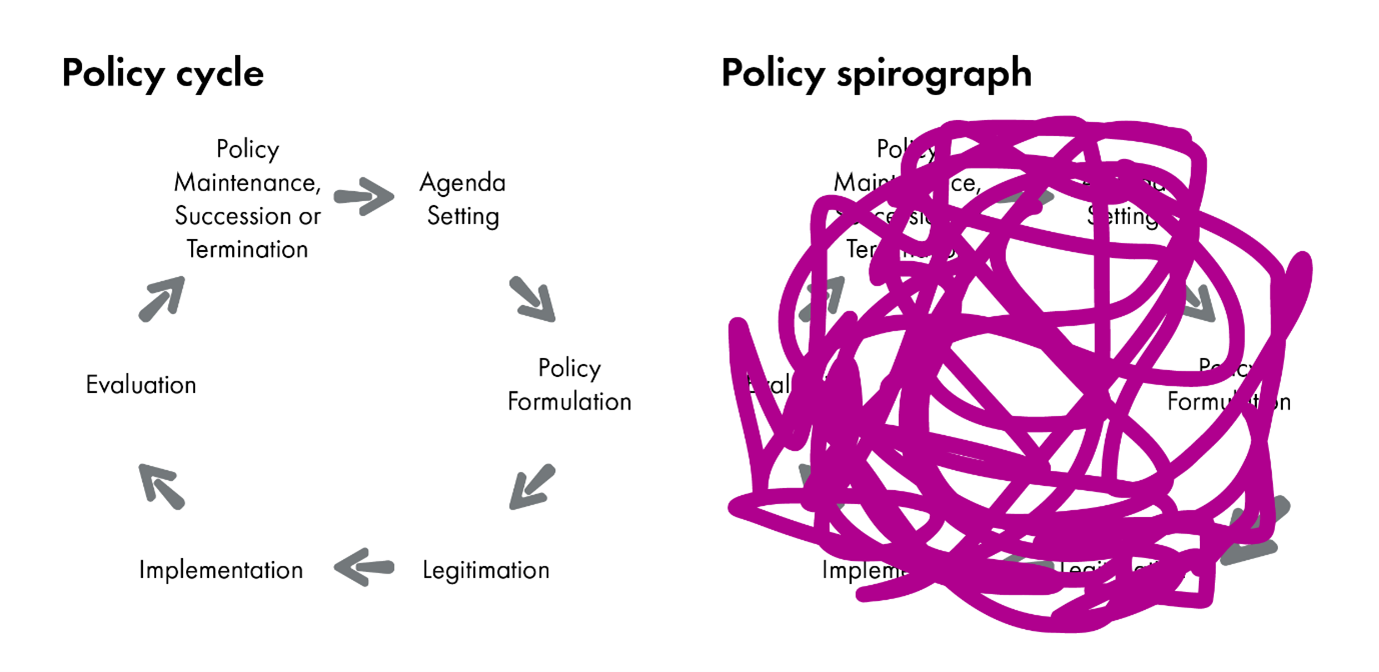

These contradictions between what governments say they do and what they actually do are common across governments and, as we heard, should be borne in mind when considering reform, as well as when seeking to learn from different approaches adopted by Governments elsewhere. They are also reflected in the inbuilt gap between the models of Government policy making (such as the ROAMEFi model) which portray the policy cycle as a linear process that can be broken down into an orderly series of steps, whilst the reality is far messier. This is shown below in Chart 1.

That reality is that “Government is about lots of organisations doing lots of things at the same time” and so the decision-making process is far messier. As Professor Cairney explained, this messiness arises “because policy makers never fully understand the problems they face or never really control the policy process in which they engage.”2

This ‘messy’ approach is however counter to Governments presenting publicly as governing competently and “telling a story that they are in charge” whilst at the same time being pragmatic in acknowledging their limits. It also impacts upon Governments’ willingness to reflect, learn from mistakes and share best practice across policy areas. As Professor Cairney explained, there is little incentive for Governments to evaluate how successful policies are because the process is “never technical and is highly partisan.”2

This ‘in built gap’ was reflected in the evidence we received. The views of former civil servants, former Ministers and a former special adviser and some stakeholders on how decision-making worked in their experience was sometimes contradicted by the views of those currently working within the Scottish Government.5

Whatever the reality, this highlights the importance of greater transparency over how decisions are taken in practice – a theme that runs throughout this report. As explained by Carnegie UK—

If we are not transparent about how our decisions are made, how budgets are set and how they are evaluated, we are neglecting the wealth of knowledge that exists in Scotland that could support the Government to do its job.6

Learning lessons from what works well and not so well is important, and as Professor Cairney sets out, “interrogating the theory and practice of effective government is essential, to identify if the Scottish government has the skills and capacity to deliver an ambitious and coherent strategy.” As such, learning lessons from other Governments may be easier as “people can say what they like” and it reduces the incentives for being partisan.2

As the Committee heard, thousands of decisions of different magnitudes are taken by the Scottish Government, with most working perfectly well and “we generally only hear about the ones where there are difficulties.”5 As such, this report focusses on the key themes arising in evidence to us rather than on every specific issue raised.

Indeed, in evidence to the Committee the DFM highlighted the range of decisions Government makes and recognised that, given the varied nature and complexity of decision-making, the Scottish Government does not claim “to always get everything right” but its decisions are supported by professional advice and formal processes. She is proud of many decisions made over the years that “have led to improved outcomes for people living here". The DFM added the Scottish Government was always willing to learn lessons and to improve which is why she considered the Committee’s inquiry to be important.9

The Permanent Secretary added that “one of the critical things that we want to continue to do is to publish the changes where we deliver improvements, for the sake of transparency”, citing the publication of the new private investment framework as a recent example of learning lessons and a standard to be followed in future.9

The findings in our report are intended to support the Scottish Government to provide greater understanding and transparency over how it takes decisions. This is important if we are to create a better informed, more nuanced and less adversarial learning environment within which we can all discuss what works well and less well in how the Scottish Government makes decisions.

To support that learning, we highlight in our report a number of examples of different practices from Governments outwith Scotland which seek to improve the quality of decision-making and which we recommend that Scottish Government Ministers and the Permanent Secretary explore.

We note the evidence from the Scottish Government about how it learns lessons, however the views we received suggest that it arises more in response to issues with the operation of specific policies than as part of a systematic approach. Our findings as they relate to accountability for standards should encourage a shift towards more systematic monitoring and evaluation.

We also recognise that all Members and the Scottish Parliament have a part to play in the manner in which they conduct scrutiny, be it encouraging reflection and learning in the Scottish Government or focussing solely on failure and blame. Accordingly, we invite Conveners Group and all Members to consider the findings in our report.

A changed context for decision-making

The context in which Government decisions are now taken has changed considerably over the past two decades, with former civil servants and former Ministers highlighting in particular more frequent policy announcements and with policy development taking place in a matter of weeks rather than months. The evolution of the 24-hour news cycle was identified as encouraging decision-making which potentially chased (or conversely sought to avoid) headlines. This had, some former Ministers felt, led to a culture of firefighting rather than of strategic thinking.1

The move to more frequent policy announcements had created a capacity challenge, with some organisations such as the Scottish Council for Voluntary Organisations (SCVO), noting “We feel that we always have to catch up with new policies when we are not sure what is happening with the old, good ones that were there before.”1 Engenderi added that holding the government to account on previous commitments means it did not have the space to create proactive ideas—

because we are in a reactive space in which we consistently have to remind civil service teams and ministers about what they have already committed to.3

Civil servants also highlighted the issue of accumulation of policy but noted that with every new Government there is a degree of detachment from decisions taken by previous Ministers which provides an opportunity to focus and simplify policy. 4The Institute for Government observed that, based on their UK Government work, some of the workload issues may reflect the ability of Ministers to delegate and set clear priorities but also to clarify with civil servants where they are delegated to take decisions.5

A number of those who had previously worked within the Scottish Government spoke of how much more polarised the political environment had become in recent years. Whilst one former Minister considered that oppositional and adversarial politics from the early days of the Parliament had persisted,6 others suggested that Scottish politics had recently become more binary or ‘yes/no’. We heard that Scotland had perhaps forgotten “how to disagree” and that civil servants and Ministers had also maybe lost the value of this when giving and receiving advice. 1

When challenged on whether the Scottish Government was overcommitted, given the current fiscal challenges Scotland faces, the DFM explained that the three missions set out recently by the First Minister were because—

we need to look at everything that we do and spend money on through that lens and ask ourselves some perhaps quite difficult questions around whether each thing delivers those key missions.8

The DFM however noted that “Rapid decision making is required in out-of-the-ordinary situations, but that does not mean that it should not still be good decision making; … and that the best evidence and advice that has been brought to you has to be relied on.” As such, confidence and experience as a Minister enables a decision to be taken more quickly, and to be able to challenge some of the advice more readily, than a Minister with less experience.8

Freedom of Information Act 2000

Former civil servants we heard from contrasted the “jaw-dropping frankness” of advice to Ministers in the period before the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOI) with the potentially narrower focus to advice once FOI came into force. They considered it could create a twin track approach to decision-making (with narrowly focussed written advice accompanied by more expansive verbal advice).1 Some former Ministers told us that frank advice and the exchange of views on risks and options was necessary to fully inform their decisions. They considered it mitigated against group think and so it is important to protect that private space.2

Scottish Financial Enterprise considered that transparency goes hand in hand with making good decisions, suggesting that “if you have made the right decision…for the right reasons” then FOI of that decision should not in of itself be a concern.3

Audit Scotland and others highlighted the differences between discourse and outcome, recognising that it is important to write down the decision, why it has been made, the options considered and those discounted. There was recognition that, in general, not every discussion, consideration or investigation of particular areas needs to be recorded.4

One approach we heard about was the New Zealand Public Service proactive publication of Cabinet Papers. Under this policy “all Cabinet and Cabinet committee papers and minutes must be proactively released and published online within 30 business days of final decisions being taken by Cabinet, unless there is good reason not to publish all or part of the material, or to delay the release beyond 30 business days.” This was, as Diane Owenga from the New Zealand Government explained, the last step in a journey to greater transparency that had originated a long time ago with a strong Official Secrets Act.5

Some of those who provided evidencei supported greater transparency in relation to the advice provided to Ministers. This would provide some level of accountability for the quality of advice but also greater transparency of why decisions are made. Whilst in the short term such an approach might attract attention and some controversy, over time Professor Flinders hoped it would be seen as part of the due process. Others disagreed, with Sophie Howe (the former Future Generations Commissioner for Wales) suggesting that, whilst it may be an ideal way to work, political reality meant that it might limit the advice provided by civil servants and instead advocated for safe space within Government for internal challenge.6

The DFM explained that the “presumption is for transparency”, citing the example of Scotland’s Third Open Government National Action Plan. She added that civil servants bring all the inherent risks alive “by telling me what lies behind the submission” and hoped it would not be the case that civil servants would feel unable to provide full, free and frank advice because it may be scrutinised by Parliament later on, as Ministers rely on an honest picture to inform their decisions.7

The Permanent Secretary set out the balance of providing Ministers with advice “as robust, objective and impartial as possible” whilst also building a culture in which people feel supported to have those honest conversations and do their jobs in a safe and secure way. This includes responding to changes in the policy landscape such as the use of Section 35 ordersii and the United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020. He advised that—

We are trying to encourage transparency within the organisation, including the early escalation of risk and that objective advice for ministers, so that they can make optimal choices.7

We recognise that developments such as social media and a more polarised political environment have all shaped and changed the way Governments make decisions in more recent times. What this report examines is the consequences of these and other challenges on decision-making and the extent to which the practices of Scottish Ministers and the civil servants who support them have kept pace.

We note the concerns from former civil servants about the potential impact of FOI on narrowing the advice civil servants provide Scottish Ministers in writing. As the New Zealand experience demonstrates, however, FOI should be seen as the start of a journey to greater transparency which we consider brings with it benefits such as greater understanding of and accountability for Scottish Government decision-making.

We welcome the DFM’s presumption for transparency and invite the Scottish Cabinet to consider the approach of routinely publishing timely information on the decisions it takes including the options considered, those discounted and why the decision has been made.

The Scottish Government's approach and structures

In his research paper, Professor Cairney describes the evolving approach to decision-making by successive Scottish Governments since devolution, beginning with a focus on accountability. It then developed to emphasise policy coherence and policymaking integration to foster long-term thinking and equity (the ‘Scottish model’), and evidence-informed, preventive, and co-produced policy (the ‘Scottish approach to policymaking’).

Structural changes from around the mid-2000s included moving from the traditional departmental boundaries and Ministerial portfolios (seen more in the UK Government), assigning more ‘organisation-wide responsibilities’ and fostering initiatives such as the Scottish Leaders Forum. In 2007, the move to an outcomes-based approach to framing Scottish Government objectives culminated in the creation of the National Performance Framework.1

The DFM highlighted the distinctive Scottish approach to delivering policy and public services, which is —

based on four priorities—first, a shift towards prevention; secondly, improving performance; thirdly, working in partnership; and, fourthly, engaging and developing our people.2

In terms of governance within the Scottish Government, the DFM explained that the Scottish Cabinet sits at the top level of decision-making supported by Cabinet Sub-Committees and a range of official governance under the corporate board and executive team.2

The Civil Service Code of Conduct for those working for the Scottish Government sets out the Civil Service values of honesty, integrity (personal, professional and organisational), objectivity and impartiality. The Permanent Secretary explained that he is accountable to Scottish Ministers and Scottish Parliament and not to the UK Government or Parliament. He described his role as three-fold, to:

serve the First Minister and his Cabinet well with regard to delivering strategic policy advice and building the team with the capability to do it

discharge the duties of being a principal accountable officer, and

lead the civil service in Scotland in a way that is right for the country.2

Lord Sedwell had however explained to the House of Lords Constitution Committee that, as head of the Civil Service between 2018 and 2020, he not only had line management of Permanent Secretaries to the devolved governments, but also had a “good, transparent relationship with the First Ministers and they recognised that… I was head of their Civil Service….as well as the UK one answerable to Westminster”. He added, in relation to Permanent Secretaries to the devolved Governments,—

I did not find it more difficult to make an assessment of the performance, capability, et cetera.5

The Permanent Secretary explained that, in relation to governance, he is a member of the Civil Service Board and also a member of the weekly leadership team led by the Head of the Civil Service, which regularly considers efficiency, governance and transparency. It also provides a vehicle for the Permanent Secretary to feed in views from the perspective of those working for the Scottish Government to reviews of the civil service, such as that announced by the UK Government in July 2022 into the functioning of the Civil Service.6

Civil servants highlighted that whilst there may be political differences between Ministers, “we are all the UK civil service” and many have worked in the Scottish Government and the UK Government.7 The Permanent Secretary also set out the benefits of collaboration arising from a single civil service (that supports three different Governments), such as supporting the effective transfer of powers in relation to social security, and the ability through the Civil Service Board to draw upon a network of colleagues and capabilities.2

The Permanent Secretary noted that workforce control has been established following the Scottish Government’s plan to return the total size of the devolved public sector workforce to around pre-COVID19 levels by 2026-27—

We have also started to try to set out multiyear plans by DG portfolio area and directorate, so that we can understand what the trajectory looks like and the choices that can be made.2

He added that workforce numbers to 2025-26 have yet to be agreed with the FM. More recently the Scottish Government’s Medium Term Financial Strategy indicates this approach to reducing workforce numbers has changed, with individual public bodies being asked to work within their budgets for 2024-25. In addition, the Scottish Government also plans to develop a pay and workforce strategy for 2024-25.2

As referred to earlier in this report, a key purpose of this inquiry is to create greater transparency around the Scottish Government’s decision-making process. For example, one of the measures identified by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) to define and measure effective government includes “Effective communication. Government websites should be authoritative, comprehensive, fit-for-purpose, and easy to navigate.”

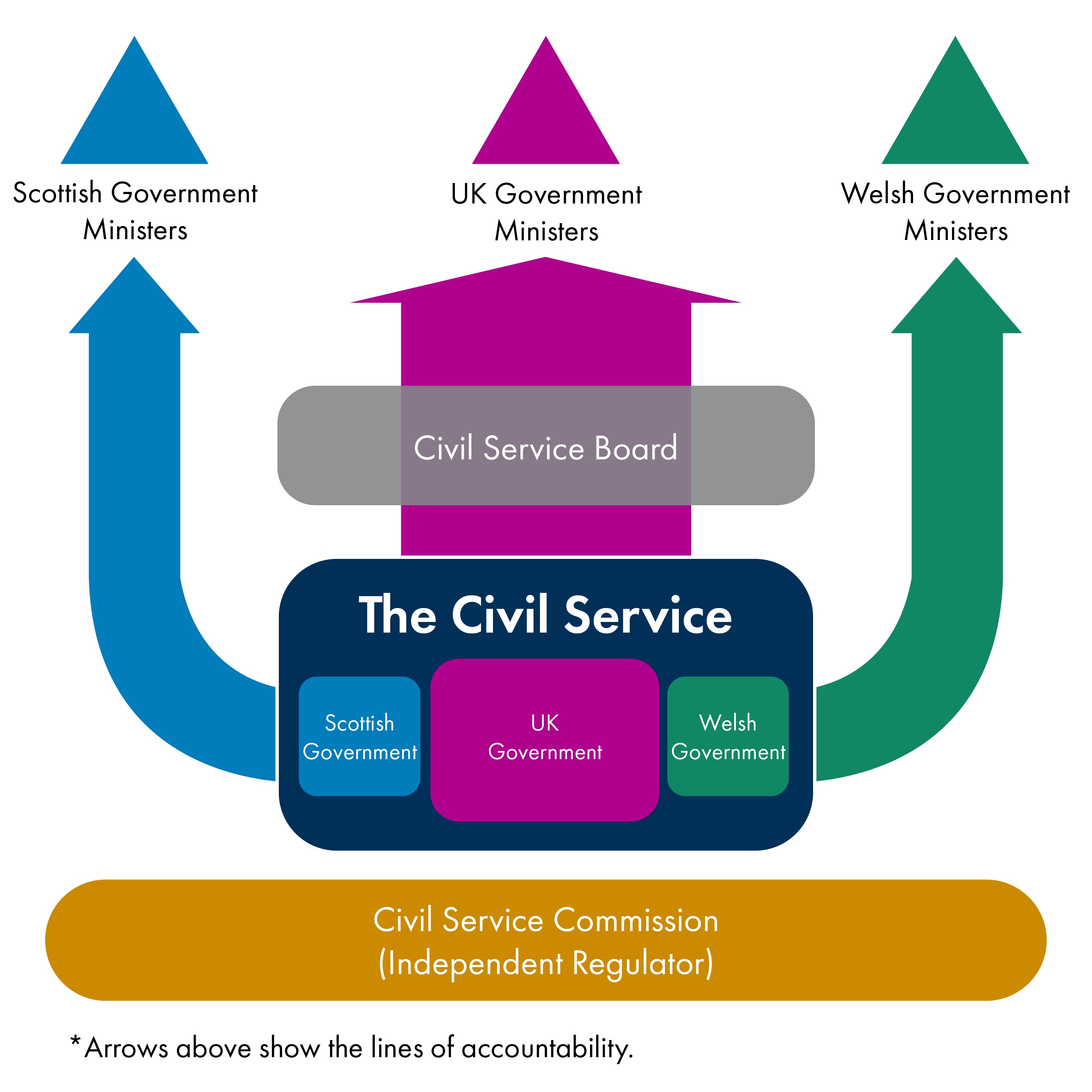

One of the first challenges we faced was to understand how the Scottish approach to policy making and the accountability of the Permanent Secretary to Scottish Government Ministers sits alongside the governance structures for a single civil service which supports three Governments. This involved us piecing together information from a number of websites and from our private discussions with current and former civil servants.

In Annexe A we summarise some of the key structures of the civil service and how they relate to the UK Government, Scottish Government and Welsh Government as we understand them. This culminates in an infographic which, for the first time, seeks to show the accountability relationships for civil servants working for each of the three Governments.

Added to the challenge of understanding these lines of accountability is the issue of terminology. For example, the terms ‘civil service’ or ‘civil servants’ are used to refer to the civil servants who, as a single service, support three Governments (UK, Scottish and Welsh) or to mean civil servants working for the Scottish Government. There are also civil servants working in Scotland which includes those who are based in Scotland but who work for the UK Government. In this report, to the extent possible, we have used the language referred to by those who provided evidence.

Reflecting on our experiences of seeking to understand how civil service governance works in practice, we consider there is a significant mismatch between the information publicly available about the civil service (for example on its webpage) and how it works in practice. We recommend that the civil service makes public how it supports Governments of different political parties at the same time, whilst remaining one civil service. As more recent debates have shown, this is particularly important in relation to how the civil service values work in practice post-devolution.11

We will therefore draw the Committee’s findings in this report to the attention of the Head of the Civil Service and the House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee to inform its inquiry into the status and constitutional position of the civil service.12

Allied to improvements in how the civil service explains what it does, we also recommend that there should be a much stronger presence and identity, than there is currently, for the civil service that supports the Scottish Government. This begins with setting out clearly and transparently (such as on the Scottish Government website) more detail on the grounds on which the Permanent Secretary is accountable to Scottish Ministers, for example, for what aspects of his performance is he accountable to Ministers and how is this assessed? It also means providing significantly more detail on his relationship to (and role in) wider civil service governance structures such as the Head of the civil service, the Civil Service Boardi and Leadership Group.

Other areas for greater transparency are identified throughout this report.

Process

A framework for decision-making

The former civil servants we spoke to considered that decision-making processes across the Scottish Government were generally unclear, unstructured and inconsistent. They highlighted that the challenge was often finding the most appropriate decision-making tool for the type of decision faced. It was, however, easier for some types of policy development and delivery such as delivering technical infrastructure projects compared with more abstract policy development.1 Fraser of Allander Institute observed that, based on their work with the Government on climate change, “It appeared to us that at times no one was responsible for some aspects” and that “there seems to be no centralised view of which areas processes are performing better than others.”2

A number of the submissions we received also identified the need for some kind of overarching decision-making tool that could be flexible or ‘moulded’ for particular circumstances, suggesting key features of a decision-making process. They also recognised that Government decision-making is, as we have already noted, messy and not a ‘neat’ linear process. As such, the Institute for Government considered that certain functions at the centre of government should be applied consistently across government (for example financial standards) but other aspects such as policy development and implementation could have greater flexibility within each department with the Minister accountable to government.3

In contrast, civil servants explained that decision-making is an iterative process with structures and systems for decision-making but also spoke of the importance of policy context in shaping what is the most appropriate approach to decision-making. They cited the recent experience of decision-making within a pandemic which enabled a shift from less ‘vertical’ (silo) working to greater fluidity of boundaries and sharing of expertise with policy and delivery working together.4

Carnegie UK explained that, without clarity over the decision-making tool being used to ensure a strategic and collaborative approach across Government, inconsistencies will arise in the way people work towards outcomes and the culture that develops in different departments.2 They and othersi suggested that the National Performance Framework provides that tool, with the addition of guidance “telling people how to make the shift towards an outcomes-based approach to decision-making.” Fraser of Allander Institute however considered that whilst the NPF is useful, “it does not address how policy is made in the first place.”2

Audit Scotland explained that for more significant decisions there is a framework for business cases to support these decisions and also highlighted the Scottish Public Finance Manual and other relevant guidance, including from HM Treasury.7 They considered that the Framework is sometimes applied well but “where things fall down is in the way the rules and guidance have been applied in practice throughout the process.” As such, they also suggested there has to be flexibility in decision-making processes, but equally—

a clearer expectation, incentive and signal in Government that it really matters that you do those things well more consistently across Government.2

Former civil servants also highlighted that, when the policy process is speedy, then without a policy framework in place, there is a negative impact on recording information.1 Audit Scotland explained that when decision-making processes work well, the records are generated by the process providing valuable clarity to Government in project management and for scrutiny purposes. They and others,1 such as the Institute for Government, questioned if the previous approach to recording information had kept pace with this changed context, including the increasing use of different ways of electronic working.2 The Institute for Government warned that, in future, records could—

get much patchier and much less coherent and comprehensive, because of technology.3

Responding, the DFM highlighted that Ministers had been supportive of the improvements the civil service had made to recoding information, including its information governance programme which seeks to ensure that there are clear records of decisions that can be retrieved quickly.13

Others highlighted how the increased speed of decision-making can limit the opportunities for undertaking post-implementation evaluation or reviews because, as the Institute for Government highlighted, “the caravan has moved on, there is no resource and everybody is now focused on the next shiny thing.”3 Fraser of Allander Institute highlighted that the focus on policy development means that it sees fairly consistently that when Scottish Government policy gets to the evaluation stage, the data does not exist.2

The Permanent Secretary explained that there is a significant programme of structured evaluation of policy, stating that—

We will keep trying to ensure that we are transparent about what we are doing and how we are trying to improve it, whether that be record keeping, private investments or our approach on freedom of information with the Information Commissioner.13

Sophie Howe explained how the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 (WFG Act) provides a framework for decision-making. It requires the Welsh Government and other bodies across the Welsh public sector to demonstrate how they have applied five particular ways of working: considering the long-term impact of the things that they do; preventing problems from occurring or getting worse; integrating their actions across Government and across other sectors; collaborating with each other; and involving citizens. When in post as the Future Generations Commissioner, she had undertaken a review in collaboration with the Welsh Government of how the WFG Act was applying these ways of working, which had resulted in a jointly constructed improvement plan for areas of Government.17

Diane Owenga from the New Zealand (NZ) Government explained its approach to improving its policy system which then led to the ‘The Policy Project’. The Project aims to “provide stronger leadership to those parts of the public service responsible for providing policy advice” by improving the capabilities, systems, processes and standards across all relevant organisations thereby improving the outcomes they contribute to. Three policy frameworks on Quality, Skills and Capability are used to foster improvement and standards of written advice are assessed, by Ministers and independent internal or external panels, against those frameworks. The most important part of the process is the support it provides to agencies for continuous improvement and to plan for future improvements in delivery of policy advice. Interim evaluation had found some evidence that mandating the policy quality framework is leading to some small improvements in policy quality.18

As the DFM explained, whilst there is no one-size fits all approach, there are principles and governance that support effective decision-making. In relation to principles, “the policy prospectus that was published at the end of April sets out the Government’s three defining missions—equality, opportunity and community— and the outcomes that we want to deliver over the next three years.” She also recognised that sometimes events outside a government’s influence and powers require Government to respond, often in an evolving situation. The Permanent Secretary explained that the Government’s prospectus also sets out the concrete deliverables for each Cabinet Secretary to make progress on according to the NPF.13

Given the complexity of policy making, the Committee shares the view that any framework for decision-making absolutely needs to be based in reality. As such, the evidence we have received suggests that of crucial importance are key characteristics or standards, essential to support effective decision-making, and against which performance can be assessed (and compared) across the Scottish Government.

Whilst the Scottish approach to policy making, as described by the DFM, has similarities to the ways of working in the WFG Act, there are important differences. In particular, the WFG Act ways of working (and the NZ policy project approach) provide a mechanism to independently assess how well the ‘framework’ for decision-making has been used in practice. This then supports further learning and improvement in Government.

This assessment is important since, as we heard, when the decision-making process is under strain (such as due to time pressures) essential components of a good decision-making process can be compromised. We therefore seek clarification from the DFM on the extent to which Scottish Ministers (and Cabinet collectively) assess whether advice provided has been arrived at by adopting the Scottish approach to policy making, alongside other priorities, such as those set by the First Minister and in the NPF.

We also seek further information from the Permanent Secretary on how he fulfils his role of ensuring strategic policy advice to Ministers, and in particular, how he evaluates advice from across the Scottish Government to determine consistency with the Scottish approach to policy making and to identify any areas for improvement.

We have also identified throughout the remainder of our report key characteristics or standards we heard support effective Government decision-making.

The use of evidence in decision-making

A common theme throughout our evidence is that Government decision-making is more effective through the early inclusion of good quality evidence from research, professional knowledge and lived experience from a diverse range of perspectives. That said, “Evidence-based policy making” is a phrase that is often used, but as Fraser of Allander Institute explained, there is a big question over what is meant by “evidence.” In their view evidence does not just mean quantitative studies of impacts; it also means the more qualitative side.1 Professor Flinders echoed this—

We now have a much broader understanding of the need to combine different sorts of useful knowledge, including academic and professional knowledge and lived experience.2

As Paul Gray (a former civil servant) explained, when it comes to ensuring advice from the civil service is—

well researched, soundly based and impartial… the more people and organisations’ with relevant experience and views that you ask, the more likely it is that your advice will be sound. You reduce the risk of the loudest voices and the best organised advocates being the only ones that are heard.3

Many we heard from had experience of participating in different forms of Scottish Government engagement and had valued the opportunity to contribute towards policymaking. However, we also often heard that lack of feedback over how organisations views have influenced subsequent policies can, as Fraser of Allander Institute described, “sometimes feel as though we are being consulted to tick a box rather than as a serious form of consultation.”1 Engender echoed these views and that “there is not necessarily trust to share power and say what we can realistically influence.”5Carnegie UK and othersi raised similar concerns and advocated for better communication of how views are to be used and what decisions are then taken (and why), explaining that “The way in which that is done can either build or undermine trust in decision making”.1 Others, such as Royal Town and Country Planning Institute Scotland (RTPI Scotland), highlighted the flexible and collaborative approach taken by the Scottish Government albeit RTPI Scotland questioned whether there is always a focus on delivering outcomes during policy delivery.5

Diane Owenga from the NZ Government noted that—

citizens expect action from Government, therefore Governments expect quick turnaround of advice from officials so that they can deliver for citizens. That is why we are trying [through the NZ Policy Project] to engender a culture in which a paper without evidence is not a good paper at all.8

Scottish Engineering highlighted the private sector approach of using strategy set at the top to determine the long-term approach to decision-making whilst everyone else in the company decides how to get there. In that regard, diversity of thought and listening to everyone are what made for an effective policy.9

Professor Martin from the Wales Centre for Public Policyii (WCPP) highlighted the importance of evidence to decision-making. He said that “evidence can feed into questions such as whether something is a problem and for whom and where it is a problem, but it can feed equally well into asking what other people have done about the issue.” He explained the WCPP approach of gathering, synthesising and sharing policy-relevant information as part of a coherent process to support the Welsh Government. WCPP will assess if it can contribute evidence to Government based on existing evidence or, in the absence of evidence, if it can provide insights from experts.2

He explained that the WCPP had sought to open up the policy-making process, in a systematic and safe way, to a much broader range of different kinds of evidence from Wales, across the UK and internationally. In his experience “there are parts of [the Welsh] Government that are well served by evidence and other parts that are largely evidence-free zones.” Much of WCPP’s work has been about providing evidence to the directorates and departments on those policy issues where there has not been a strong evidence base in the past. It also had to navigate with Ministers how academics could give honest, independent and, at times, challenging evidence whilst creating an environment where Ministers can trust that academics are trying to be constructive. It uses a publications protocol to set expectations, providing time for Ministers to consider the evidence before its publication.2

As we heard, Governments can also seek to “borrow” knowledge and insights from experts (and create spaces within which that can happen). In addition, former Ministers identified the approach of senior civil servants spending time in sectors outwith Government as a valuable way to provide wider insights and exposure to different ways of working.12 Civil servants agreed that secondments were a good way to diversify perspectives within Government although there was less certainty on how often inward or outward secondments are currently taking place.13

Others also supported more job swaps or secondments as a valuable way to better improve policy making providing cross-fertilisation of experience and knowledge, with Sophie Howe highlighting the short-term experience programme at the Welsh Government.2

Understanding the breadth of evidence that is already available is important to ensuring there is clarity of purpose at the start of policymaking. Roger Mullin15 and Professor Johannes Seibert16 also identified the importance of clarity of purpose – in agreeing the context of why a decision is needed (the objectives) and the broad evidential basis that should be used.

As described by Audit Scotland “what is to be achieved and how will we know when we have achieved it” is important not only to assess the policy but to learn from what went well and less well. This, along with the “lack of data collection, the lack of understanding of how things will be measured, and the lack of priority given to that”, all contribute towards an implementation gap.1

This implementation gap issue also arises because, according to Dr Helen Foster, delivery and implementation are treated as separate processes with different people involved. She said that—

You need some people who are there from the beginning and right through the process, but you also need people coming in and out of it. You need to add value as you go through the whole process.9

We also heard frustration that consultations on the same or similar issues are repeated, with the same questions asked of the same people, rather than learning from the data already collected and identifying where value can be added through further consultation.5 Fraser of Allander Institute explained that “there is often a natural bias towards trusting something on which we have data versus something on which we do not have data. Timing is key in determining what data is needed as when data can be introduced will potentially influence some of your policy options or the decision made.”1

The DFM agreed that “Nobody, including civil servants, can be an expert on everything. Inevitably, you have to draw on other stakeholders such as the business community, who have a level of knowledge and experience, and a view. You draw all of that in to try to make the best decision on the information that is in front of you.” Consultation and stakeholder engagement, such as the National Advisory Council on Women and Girls, were highlighted by the DFM as some of the ways the Scottish Government integrates external views into its decision-making.21

As we heard, many valued the consultative approach taken by the Scottish Government to inform its decision-making. We also acknowledge the different engagement approaches the Scottish Government uses to ensure that its policies are informed by knowledge, expertise, experience, and challenge.

What we learned from a range of organisations is that a shift to a more coherent approach is needed across the Scottish Government to ensure that engagement meets the standards now expected in order to better inform decision-making. This includes greater trust and transparency in communicating how evidence from stakeholders will be used (what can be influenced); what decisions are then taken and why some options are favoured over others.

We consider that a more systematic approach will also ensure that stakeholders' experience of engagement is more consistent. The partnership approach embodied by the WCPP model has much to be commended, providing a systematic and transparent way to gather robust evidence from a spectrum of stakeholders (in this case, academics).

We recommend that the Scottish Government takes forward this approach, particularly given we heard that capacity challenges (such as a reducing workforce) increase Government reliance on external organisations to inform its policy making. We would also welcome clarification of how the Scottish Government assesses the quality of its engagement across the different policy areas in Government to identify any areas for improvement.

As Professor Flinders explained, “Worldclass policy-making structures are often defined by the capacity to facilitate the mobility of people, talent and knowledge across traditional institutional and professional boundaries.”2 We therefore seek further information from the Permanent Secretary on how the Scottish Government uses inward secondments to draw in additional resource and to provide staff with broader experience (including of policy implementation) and any plans to build on existing arrangements for both inward and outward secondments.

Challenge and risk

Fraser of Allander Institute explained how challenge could be seen as key to many of the issues highlighted about decision-making, suggesting that there was sometimes a gap between whether processes are followed or followed well. In addition, if challenge takes place too late and the project already has a set direction then, “there is an incentive to not want to overly challenge it” and it is difficult to then realign the project.1

Similarly, Audit Scotland explained that, whilst risk management is built into the decision-making process, where they criticise risk management it is in “the application of it and how it is working.” In managing risk, Audit Scotland notes that nothing that the Scottish Government does is risk free and that decision-making is therefore about balancing those risks and then managing them once a decision has been taken.1

Some former Ministers3 as well as other witnesses45highlighted how some organisations and academics may feel unable to act as a ‘critical friend’ in relation to government policy for fear of losing funding. Therefore, creating safe spaces might support greater candour. SCVO said for example that “we are also calling for the expectations and parameters for the discussions to be defined from the beginning, and for it to be made clear that the issue of funding will not have any impact on what an organisation can say.”4 Professor Jonathan Baron also highlighted the importance in group decision-making of ensuring that “doubters about an apparent group consensus have their say” thus avoiding ‘Groupthink’.7

A number of witnesses highlighted that the risk of making mistakes can lead to delays in making a decision until there is 100% certainty. Scottish Engineering spoke of that sector’s principle that “close enough is good enough” when 80% certainty that the decision is right means the decision can be taken more quickly and be built upon in subsequent iterations.8 Children in Scotland also echoed this view and spoke of “that optimal sweet spot” of having enough information to make a good enough decision.4

This risk of making the wrong decision also manifests itself in the outcomes of Government reviews, with Scottish Financial Enterprise explaining that reviews of policies often identify many recommendations when “you discover that half a dozen will deliver 80 per cent of what you are looking for.”8

Sophie Howe highlighted her experiences of reviewing how the Welsh Government was embedding the requirements of the WFG Act. She said—

I feel that we were able to push it more into the space of critically reflecting on where things were working and where things were not. At the end, we developed a jointly constructed improvement plan for areas in which the Government could improve on implementing that piece of legislation.11

Civil servants recognised the roles of both Audit Scotland and gateway reviews in assessing decision-making for projects and highlighted a range of governance structures that provided important checks and balances. Non-executive staff, as well as other civil servants (such as Accountable Officers), also provide a high level of scrutiny. It was also recognised that the smaller size of the Scottish Government means that there are fewer silos but with more people knowing each other, challenge and avoiding group think can be more difficult. That is why tools such as Impacts Assessments were seen as important in maintaining challenge.12

The DFM recognised the importance of external advice, challenge and scrutiny, highlighting the various ways that the Scottish Government integrates external views, such as through consultation and stakeholder engagement, including through expert advisory groups such as the COVID19 advisory group. She agreed that—

we need to guard against any perception, real or not, of organisations that receive Government funding taking a particular stance on issues, because the evidence shows that organisations are robust in their criticism of the Government, even when they receive Government funding, and that is how it should be.13

The DFM agreed that risk cannot be 100% eliminated and ultimately Ministers have to apply their judgement to the options and risks identified by civil servants. In addition, she considered it critical that Ministers accept that, sometimes, they will get “information about something that they have absolutely wanted to do that shows that it is just not doable, for all the good reasons that are set out in front of them.”13

That said, the DFM observed from her experience that sometimes “it can take a frustratingly long time to make decisions” as it takes time to explore the advice and options even when there is an eagerness to address an issue.13

We agree that creating a culture supportive of challenge throughout the decision-making process is important in supporting effective decision-making, be it to test evidence or received wisdom or to fully explore the risks of a range of options.

As we heard, creating safe spaces to enable more challenging evidence to be provided to civil servants working for the Scottish Government or Scottish Ministers is also important to ensuring that any power imbalances (such as arising from funding relationships) can be mitigated. As we recommend above, the WCPP model of providing clear ground rules for engagement can support those ‘safe spaces’ for challenge and should be taken forward by the Scottish Government.

Short term versus long term

A consistent theme arising in evidence was the need to shift the focus more away from firefighting to address short-term issues to tackling longer term issues, although many recognised the difficulties in doing this.

As Audit Scotland explained, it is about prioritisation between short and long term issues when capacity is finite and “about how the right balance is reached between each aspect”.1 Carnegie UK also highlighted the “perverse incentive” created when there is a focus for scrutiny on narrow performance targets which skews the focus to delivering on “instant results instead of longer-term goals.”1 As Dr Foster explained, the tendency for short-termism in Government policy-making is a long standing issue but “It has to be joined up, so that you can take the short-term decisions that are part of a longer-term strategy.”3 Dr Judith Turbyne from Children in Scotland echoed this, highlighting from her experience in international development and disaster relief, that when responding in a crisis a key question at the start is “What is the most preventative way that we can respond to this crisis?”4

One former Minister suggested that, in their experience, there has been a shift in how Ministers engaged on longer-term issues from listening mode to now being more likely to try and provide answers and defend Government policy approaches. It was argued that this discouraged ‘honesty’ about how to address long-term issues to which there are no easy answers. It also did not challenge the assumption that all problems in society must be addressed by Government or Parliament.5

The Committee heard about the Long-term Insight Briefings statutorily required from the NZ Public Service every 3 years. These briefings aim to make public and for scrutiny by Parliament “information about the medium term and long-term trends, risks and opportunities that affect or may affect New Zealand and New Zealand society, and impartial analysis, including policy options for responding to those matters.”6 This requirement builds on the value of Stewardship, given the civil service not only serve the government of the day but future governments. As Diane Owenga from the NZ Government explained the long-term focus means that the real decisions on how to address issues “might not be made until after an election or even two.” This approach arose out of concern that those in the public service focussed on the short term and whether, without having it as a requirement of legislation, “the chances are that the short-term stuff will always push out the long-term stuff.”7

Some of those who provided evidence were broadly supportive of long-term briefings, including SCVO which observed that “partnership working between institutions needs to be embedded so that, when someone leaves, there is still collaborative working between sectors. A long-term vision would help with that.” Engender also considered that expanding the civil service remit in such a way recognises that—

Parts of Government business will not change as a result of a change in political Administration, but there is often a need for the whole civil society sector to continually say the same things.4

Another approach we heard explored in evidence was the impact of the WFG Act which applies to all Welsh public sector organisations including the Government and sets out “seven long-term wellbeing goals that our Government and all our public institutions are required to set objectives to achieve.” This provides a clarity of purpose for all organisations and, as long-term goals, “their span goes beyond political cycles.”9Under that Act, the Future Generations Commissioner can scrutinise public body plans to tackle those goals.

The Scottish Government confirmed (in its Programme for Government for 2022/23) that it will explore how to ensure the interests of future generations are taken into account in decisions made today. This may include placing duties on public bodies and local government to take account of the impact of their decisions on wellbeing and sustainable development, and the creation of a Future Generations’ Commissioner.10

As noted previously, a key pillar of the Scottish Government approach to policy making is a shift to prevention. In evidence, the DFM explained that, in seeking to manage between policy intent and outcomes, the focus is ensuring the finances are sustainable —

We are really trying to land that in the right place for short-term fiscal balance. On the longer-term position …there are things that maybe do not deliver on the intended outcomes that we need to take a hard look at. That work is under way at the moment.11

As we have heard throughout this and other inquiries we have undertaken, it can be challenging for Government to seek to address long-term issues given the immediacy to respond to short term pressures.

We note that, like the Welsh Government, the Scottish Government is considering legislating to require a long-term focus by public bodies. As identified in the 2022-23 Programme for Government, the Scottish Government Bill could require public bodies to consider longer-term sustainable development and wellbeing. We seek an update on progress with this Bill.

More recently, we also considered the first Fiscal Sustainability Report from the Scottish Fiscal Commission. We welcomed this as a valuable contribution to the debate around the adequacy and sustainability of current policies on tax, spend and public reform to 2072-73.

Given this, and recognising the role of civil servants in providing ‘continuity’ across different governments, we recommend that Scottish Ministers and the Permanent Secretary consider whether civil servants working for the Scottish Government should provide long term insight briefings on the challenges Scotland faces over the next 50 years (as is the case in New Zealand).

People

Churn

One of the benefits of an impartial civil service that stays in office across Administrations is that it develops deep expertise. As the Institute for Government explained to us, “The legitimacy of the civil service relies on its expertise and its ability to serve successive Governments and ministers.”1

As we heard, the culture within the civil service is of ‘generalist’ civil servantsi who are likely to move jobs at least every few years (commonly referred to as ‘churn’) as compared with ‘specialist’ civil servants who may be more likely remain within a policy area.2 A common theme across the evidence we received was that there was too much churn in the civil service (including amongst those who work for the Scottish Government).

Some of the benefits of churn highlighted to us include:

giving staff a range of experiences (and skills) in different jobs3

the development of helpful contacts across Government, supporting cross -organisational knowledge and working4

enabling fresh insights to be brought to teams by those newly moved and avoiding group think4

providing greater opportunity to be promoted because of experience and skills gained.

Others, however, cited that this practice can come at the expense of:

loss of institutional memory and expertise

disruption in continuity of good advice to Ministers (sometimes at short notice)

potentially diminishing the challenge culture with Ministers as those who work on a policy are no longer there to advocate for it or provide frank, evidence informed views, having built a relationship of trust6

undermining relationships, trust and understanding with organisations which can then take time to rebuild7

the loss of expertise available to support the passage of subsequent secondary legislation (and operational delivery) once a Bill team is disbanded.6

Churn can also arise unavoidably, such as in response to crises such as COVID19 or the situation in Ukraine, where civil servants are brought together quickly from other areas to facilitate a response. They then develop their experience rapidly and once operations become embedded, they can pivot to different policy areas.

As we heard, the traditional approach of having largely generalist civil servants has evolved over time with a greater desire to ensure that people with the best skills are retained. As such, concerns were raised with us that specialists, are in particular, more likely to hit a career buffer if they want to stay in that policy area and that, in general, more specialists are needed in the civil service. One possible solution proposed by the Institute for Government and others6 was that there should be more of a ‘career policy anchor’ so that people are much more consciously anchored to a particular policy specialism which supports career progression, whilst also enabling a broader and deeper understanding of how government works from within their sphere.1

The traditional view of the civil service as a ‘career for life’ was also challenged by former civil servants who suggested that people are now frequently moving into and out of the civil service, which potentially impacts on the skills base and on the time available to develop skills and experience. Allied to that, we heard about a mixed picture of the extent to which the skills mix of staff is understood and how different skills were valued (and had developed over time). For example, the focus on professional skills such as leadership over the past decade may have come at the expenses of core civil service skills such as how to frame advice. These core skills are seen as a bulwark against the problems of providing challenging advice, providing confidence in understanding the civil servant role.3

Former Ministers also recognised the impact of Ministerial ‘churn’, where Ministers move portfolios, potentially lose the expertise they had developed and the incoming Minister may have different priorities on future policy direction. Given this, it was not considered realistic for Ministers to act as project managers but rather to take decisions and exercise political judgement.6

There was little appetite amongst the former Ministers we spoke to for specific training, other than ‘on the job’, to be provided to Ministers. That said, it is a key skill of a civil servant to understand the different styles and preferences of Ministers and to provide support in terms of understanding new portfolio areas.4

As we heard, this is where Government having a clear overall long-term focus which sets the direction of travel regardless of the individual specific focus of Ministers is important. As Scottish Financial Enterprise recognised—

That might be easy to say and harder to bring about in practice, but that is the only way that you will get that longer-term focus on delivery, implementation and subsequent impact.1

The DFM acknowledged the impact of churn, but also observed—

based on what I have seen and experienced, the skill of the civil service is that they are very quick to adapt; they are agile and able to get to grips with new policy areas. There is a recognition that we have to keep a close eye on head count. We cannot have exponential growth. That means that it has to be an agile organisation and that civil servants will have to pivot, such as they did on Ukraine, for example.15

Similarly, the Permanent Secretary recognised the risk of too much churn, but he also considered that “we also want to bring in fresh talents, to diversify the capabilities at the top and throughout the organisation, and to ensure that the organisation reflects the country that we serve.”15

We heard of more recent work being undertaken as part of the Government’s people strategy and the development of a workforce plan to introduce a new system to enhance capabilities and assign civil servants working for the Scottish Government into ‘job families’. As Lesley Fraser from the Scottish Government explained, that means “understanding whether someone is a policy expert, a legislative expert or a lawyer…. We have 21 different professional groupings in the civil service in Scotland already. Some of those are quite mature—the data and digital professions and the legal profession, for example—while the change management profession is a growing area for the Scottish Government.”15 This new way of working will also help with sharing expertise for career development and offer attractive career pathways.

We acknowledge that civil servants that work for the Scottish Government, like everyone else, need or wish to change posts to gain new skills, maintain job satisfaction or to secure promotion. Given the numbers of civil servants working for the Scottish Government, the impact of churn arising from this movement of staff could be considerable.

We also recognise the importance for effective decision-making in having a mix of generalist staff that can “synthesize advice, fix things and act as translators of policy”1 and specialists who have deeper, more technical expertise, necessary for sound policy making and to ensure effective governance on matters such as finances.

The impression we have from across the evidence we heard is that a greater shift is needed from the traditional model of the civil service which values ‘agile’ generalist skills to one which also values a more diverse range of specialist skills and which supports staff to flourish within their policy areas should they wish to.

We acknowledge the recent development, within the civil service supporting the Scottish Government, of job families, which aims to enhance capabilities and provide for career development. We request clarification of the extent to which this (and any other mechanisms) will address the negative impacts of churn we identify at paragraph 133 of this report.

Whilst Ministerial churn cannot be avoided, we share the view of witnesses that excessive Ministerial churn can disrupt policy focus and policy development. We seek clarification from the Deputy First Minister of the extent to which incoming Ministers are supported by their Ministerial peers to provide continuity in the Scottish Government’s approach to policy development and policy focus.

Leadership

The Committee heard that the quality of the relationships between Ministers and the civil service is key to effective decision-making. Both former and current civil servants as well as former Ministers considered that effective Ministers set the culture for decision-making by giving clear instruction around policy direction and what they need to do their job. This then empowers the appropriate civil servants to make decisions and steer policy.12

For some former civil servants, the smaller civil service working for the Scottish Government led to greater opportunities to influence decision-making, as a result of a less hierarchical and closer working relationship between Ministers and other civil servants.

Othersi identified leadership by senior civil servants working for the Scottish Government as setting the tone of the civil service in a range of areas such as:

challenge, as the Fraser of Allander Institute identified, “ensuring a culture where things can be said and got wrong and where it is accepted as part of the process that not everything will be correct.”3 Without a tolerance for mistakes, Scottish Financial Enterprise explained that a culture arises in which “accountability is lacking because people do not want to admit mistakes.”4

leading by example in who is empowered to take decisions and the extent to which this may extend beyond senior civil servants. Civil servants working for the Scottish Government told us that culture from the top down was seen as critical to providing greater consistency in the empowerment of civil servants across the grades to take decisions.5

how high-level commitments, for example gender mainstreaming, reach those working on the granular detail of policies. As Engender explained, without high level commitment “civil servants ….might not understand how to do that work, why it is important and why they are being asked to do it with stretched resources and time.”6

The role of the Accountable Officer was highlighted as being important to that culture of challenge. As it was explained to us, such an official designation to challenge or test decisions supports civil servants to push back when there are concerns about Ministers' proposed approaches.2

Responding to questions about how to manage the negative impacts of Ministerial churn, Scottish Financial Enterprise explained that, in the private sector, one of the most valuable traits of leaders is a desire for lifelong learning and that “You do not know what you do not know, but if you are interested enough in it, you can get into it quickly enough that your leadership skills can then allow you to differentiate and lead in that way from those behaviours, culture and analysis.” Adding that

As a person goes further up in an organisation, into broader leadership roles, the balance between breadth and technical expertise changes. Trying to understand that at different levels of the civil service is important.4

The DFM explained that, in relation to Scottish Ministers and civil servants, “It is important that there is absolutely that respect and a culture that respects the fact that the relationship is not always one of equals.”9 The Permanent Secretary explained that there is a lot of focus on partnership and system leadership across the civil service supporting the Scottish Government, adding that—

We are ensuring, too, in relation to training of our senior civil servants and all our staff, that colleagues are absolutely aware of our expectations of them and that they understand what to do and how they should respond if a concern is raised.9

We agree with witnesses that the relationship between Scottish Ministers and the civil service that supports them, and in particular its senior leaders, is key to fostering a culture of full, frank and informed advice, robust challenge and learning from mistakes. As such, we seek information from the Deputy First Minister on how Scottish Ministers foster a culture of learning and constructive dialogue amongst Ministers, and with the civil servants and others from whom they seek advice.

We also seek information from the Permanent Secretary on how he seeks to assure himself that his senior leaders are embodying the culture, skills and attitude needed to lead by example.

The designation of Accountable Officer was cited a number of times as, in of itself, providing those senior civil servants with a greater confidence and assurance to provide challenge. We therefore recommend that the Permanent Secretary considers whether there should be more explicit delegation of specific key policy development functions to senior civil servants, for example, in relation to other key behaviours expected of them.

Performance

Accountability for improving standards

Carnegie UK noted that whilst Government is “good at being accountable to particular targets and outcomes” it is “perhaps less so on the process of getting there.”1 A common question raised with us is how the different parts of Government are held to account (particularly in relation to decisions made in cross-cutting policy areas) for how they are applying the Scottish Government decision-making principles, such as how they collaborate with other departments, integrate policy areas or embed long-termism and prevention into the decisions they make.

The Institute for Government considered that civil servants should be more accountable to Parliament for the consistency of some functions of Government although they recognised that it “butts up against Ministerial accountability.” They suggested greater oversight (potentially with a legislative underpinning) might then help Permanent Secretaries and other senior civil servants to “feel the heat a bit more on those kinds of capacity or capability of the state-type questions.”2

In addition to external accountability for how decisions are made, we heard from Fraser of Allander Institute, based on its work with the Scottish Government on climate change, that

it appeared at times that no-one was responsible for some aspects such as querying value for money in terms of socioeconomic impacts or climate impacts. If no one queried that situation, under time pressure, the matter was often not addressed in the first place.1

Civil servants working for the Scottish Government have a diverse range of learning opportunities through a number of routes. This includes through coaching and mentoring, the Civil Service, the Scottish Government’s central learning and development team and learning teams within specific directorates,4 for example training on finance and risk – which is led by Finance - or the Scottish Digital Academy which sits within the Digital Directorate.

More recently in relation to civil servants working in the Policy Professioni, Policy Professional Standards have been developed for use across the civil service, with a bespoke approach for those working in a Scottish context. This 2021 framework explains that it “defines the skills, knowledge and activities required for each Standard as individuals progress from gaining foundational knowledge, to becoming a skilled practitioner, to being a policy leader."