Finance and Public Administration Committee

Budget Scrutiny 2023-24

Introduction

The Scottish Budget 2023-24 was published on 15 December 2022 and presents the Scottish Government’s proposed tax and spending plans for the next financial year. This report sets out the Finance and Public Administration Committee’s conclusions in relation to the Scottish Budget 2023-24, informed by our Pre-Budget Report 2023-24 (on Scotland’s Public Finances in 2023-24 and the impact of the Cost of Living and Public Service Reform), published on 3 November 2022, as well as the Scottish Government’s response to it. In our report we also consider the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body’s (SPCB’s) budget submission for 2023-24, as required by the Session 6 Written Agreement between the Committee and the SPCB.

Accompanying the Scottish Budget 2023-24 is the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s (SFC’s) latest set of forecasts for the economy, tax revenues and social security spending - Scotland’s Economic and Fiscal Outlook, December 2022. These Forecasts, alongside those of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), inform the overall size of the Budget for 2023-24. The SFC’s view is that Scotland has already entered a recession and it expects Scottish households to see the biggest real terms fall in their disposable income since Scottish records began in 1998. The SFC has advised that resource funding in the Scottish Budget 2023-24 is set to increase by £1.7 billion in nominal terms, but by just £279 million in real terms compared to the latest funding position for 2022-23. It also stated that the capital budget is flat in nominal terms between the latest position for 2022-23 and 2023-24, reflecting a cut in real terms of £185 million.4

Scotland’s public finances are under considerable strain this year, with high inflation, a cost-of-living crisis and demands for improved public sector pay deals. The Deputy First Minister has also pointed to volatility from global factors and the consequences of the UK Government’s September 2022 Fiscal Statement as unprecedented challenges that the Scottish Government is facing. The budget for 2022-23 is yet to be finalised despite difficult decisions to reduce spending by £1.2 billion in year. The Deputy First Minister has suggested that the pressures on the 2023-24 budget “cannot be overstated”5, with inflation continuing to erode the spending power of government, households and businesses. The Scottish Government’s focus on addressing the cost-of-living impacts in both years is understandable given the scale and immediacy of the challenge, however, there is evidence that longer term planning is not being given the priority it needs to ensure fiscal sustainability. This is a key theme of the Committee’s report, where we call for greater progress and clarity in a number of areas, including on the Scottish Government’s public service reform programme and its public pay policy.

The Committee was supported in our scrutiny of the Scottish Budget 2023-24 by our adviser, Professor Mairi Spowage, and the Financial Scrutiny Unit in the Scottish Parliament’s Information Centre (SPICe). We also thank our witnesses from the SFC, the Expert Panel advising the Scottish Government on the implications for the Scottish Budget of UK Government fiscal statements, the SPCB, and the Deputy First Minister, for their valuable evidence. We further welcome the evidence we received prior to the Scottish Budget 2023-24 being published, from the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), on which the Committee has also been able to draw, for the wider UK context.

Economic and Fiscal Context

UK Economy

After a tumultuous time economically in the Autumn, the latest set of official forecasts for the UK were finally published by the OBR alongside the Autumn Statement on 17 November 2022. These were the first forecasts published by the OBR since March 2022 and, given all the events since then, the outlook for the next couple of years has worsened significantly, as shown in table 1 below.

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 2022 forecast | 3.8 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.7 | |

| November 2022 forecast | 4.2 | -1.4 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.2 |

However, the OBR forecasts are more optimistic than those published by the Bank of England (BoE) in early November. Two things are notable – (i) the OBR expects that the recession will last for five quarters, rather than the two full years forecasted by the BoE and (ii) the OBR is much more optimistic about the “catch-up” in the economy in the years following the recession, whereas the BoE is expecting very low and sluggish growth to continue into 2025.

The OBR expect the overall fall in output in the economy (the “peak to trough” fall) to be 2.1%, which would make this recession more shallow than the global financial crash in 2007/08, and more like the depth of the recession that was experienced in the early nineties. The OBR forecast a cumulative fall of 7.1% in household disposable income in the UK from 2021-22 to 2023-24.6

Inflation, of course, looms large over all the forecasts produced in Autumn. The OBR expected in November that inflation would have peaked in the fourth quarter of 2022 at 11.1%, revised up significantly from the peak of 8.7% it was expecting in March. The peak would have been significantly higher without the UK Government’s Energy Price Guarantee (EPG). The OBR estimate that inflation would be peaking at 13.6% in Q1 2023 without that intervention.6 ONS statistics published on 18 January 2023 show that Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation fell to 10.5% in the year to December 2022, compared with 10.7% in November.

The EPG will continue to put downward pressure on inflation through the early part of the forecast horizon, although the OBR estimates that the increase in the cap on unit prices coming in April 2023 will add 1 percentage point to CPI inflation. The OBR then expects inflation to fall to 3.8% by the end of 2023, before falling in the first half of 2024 below the target the UK Government sets for the BoE to keep inflation below 2%.6

The UK’s fiscal position has weakened significantly since the OBR forecasts in March 2022, due to a weaker economy, higher interest rates and higher inflation. The OBR now expects the fiscal deficit to be 7.1% of GDP in 2022-23, up from its5.7% forecast in March.6 As our adviser notes, there have been many changes to the UK Government’s spending plans since March, but the main drivers of the increased fiscal deficit are the costs of the EPG and higher payments to service the UK Government’s borrowing.

Tax measures announced by the UK Government in Autumn included a continuation to 2027 of threshold freezes in various taxes, rather than to 2025 as previously announced.7 Our adviser explained that the most notable threshold freezes are in income tax, where fiscal drag is ensuring that more people are brought into higher rates of tax over the forecast horizon. The tax burden (i.e. the ratio of taxes to GDP) peaks at 37.5 % in 2024-25, which would be its highest level since the Second World War.

As noted by our adviser, the Chancellor saved most of the fiscal pain for towards the end of the forecast horizon, pushing the main spending cuts (compared to what had been set out previously) to past the expected time of the next UK general election. Even so, he only just met his new fiscal targets, to have the fiscal deficit under 3% and debt falling as a % of GDP by the end of the forecast period to 2027. It is unclear whether these will be fixed or moving fiscal targets for the Chancellor.

The OBR flagged up a number of risks to the fiscal forecasts. For example, itscurrent forecasts assume that the UK Government will allow the fuel price escalatorv to increase fuel duty by 23% in April, which the OBR point out is extremely unlikely to happen.6 If, as is more likely, the UK Government freezes fuel duty, there is a shortfall of almost £6 billion in forecast revenue. On the spending side, the Chancellor did not include any provision in the UK Autumn Statement for newly announced energy support for businesses. It has since confirmed that the new, scaled-back support, is likely to cost around £5 billion.

Scottish Economic and Fiscal Outlook

The Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) set out its new forecasts for the Scottish Economy4 alongside the Scottish Budget1 on 15 December 2022.

Like the OBR, the SFC presented a significant deterioration in their forecasts compared to their last forecasts in May, as set out in table 2 below.

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scotland: SFC May 2022 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Scotland: SFC December 2022 | 5.0 | -1.2 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.6 |

| UK: OBR November 2022 | 4.2 | -1.4 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.2 |

The SFC’s view is that the recession in Scotland will have a peak-to-trough fall of 1.8%, slightly shallower than that for the UK, but similarly that the recession will last for five quarters. As has generally been the case since the SFC started forecasting the outlooks for the Scottish economy, Scotland is forecast to grow more slowly than the UK economy as a whole. This is mainly due to demographic differences (i.e. projected slower population growth in Scotland), but also due to slower productivity growth and a poorer outlook for participation.4

The outlook for nominal earnings in Scotland has been revised up significantly, but, due to much higher inflation, the outlook for real earnings is much poorer over the next two years. The increase in nominal earnings however means the outlook for income tax has been revised up by the SFC and, despite the poorer economic conditions, this adds almost £1 billion to the income tax forecast for 2023-24.4

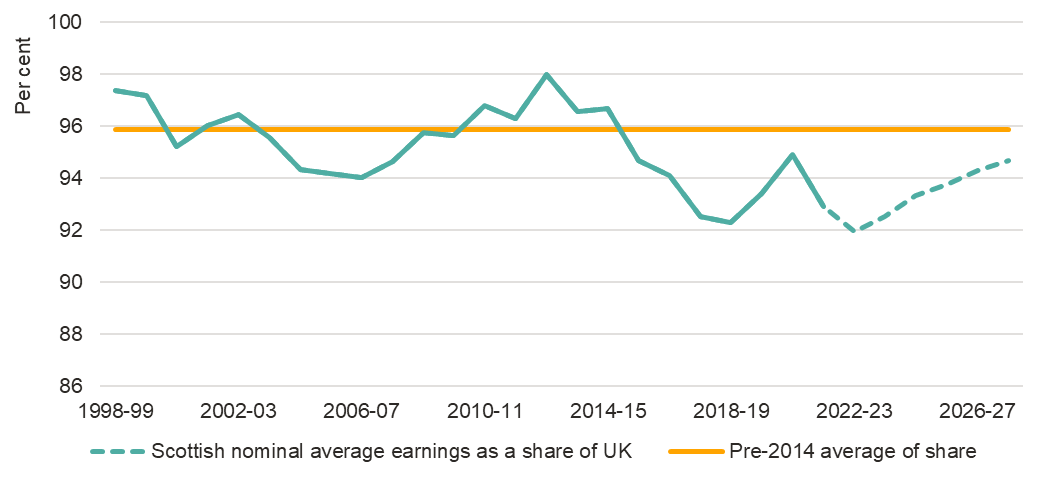

The SFC expects a slight recovery in Scottish nominal earnings relative to UK nominal earnings, although they still sit below the historic level4, as shown in figure 1 below.

The reasons for this slight recovery are set out in the SFC report:

Higher energy prices and an increased emphasis on energy security leading to a relatively more positive outlook for earnings and employment in the oil and gas sector.

Greater alignment in the outlook for earnings growth in Scottish and UK financial services.

Scottish households tend to have smaller mortgage debt than households in other parts of the UK, meaning they will be less affected by rising interest rates, supporting economic activity in Scotland.4

Continuing Pressure on 2022-23 Budget

The Scottish Government published its Emergency Budget Review on 7 November 2022, which identified £615 million in savings for this financial year, on top of an initial package of £560 million announced by the Deputy First Minister on 7 September. These savings were made to allow funds to be diverted to tackling the cost-of-living crisis, including improved pay offers for public sector workers.

The Deputy First Minister explained to the Committee on 10 January 2023 that “across Government, through the Emergency Budget Review, we have taken difficult decisions that have resulted in a total of £1.2 billion of reductions in public expenditure, which has allowed us to meet the costs of increased public sector pay [offers] and to provide further help to people who have been most impacted by the cost-of-living crisis”. He said he was “still working to ensure that we forge a path towards balancing this year’s budget”, adding “we have a long way to go on that, and there are a lot of variables, not least of which is the supplementary estimates from the UK Government”.5

Asked when the Committee can expect the Spring Budget Revision (SBR), the final opportunity to make in-year changes to the 2022-23 Budget, the Deputy First Minister advised in writing that the SBR is currently scheduled to be laid in Parliament on 2 February. He explained that “there is very limited scope to delay the revisions given the time required to incorporate the committee evidence session as well as the normal parliamentary procedures required to approve the SSI”, given it needs to be agreed by the end of the financial year on 31 March 2023.

The Deputy First Minister was also asked to confirm what sum of money remains unresolved in this year’s budget. He advised in evidence that “it is fair to say that the sum varies, depending on the assumptions, from about £200 million to £500 million”.5

Unresolved public sector pay deals are placing further pressure on the Scottish Government’s ability to ‘balance the books’ at the end of the year. The Deputy First Minister said the Scottish Government was “working hard” to resolve outstanding pay deals. However, he explained “there is real cash pressure, [as] if, for example, I were to offer more money for a particular pay deal in this financial year, I would have to find that money, and that would simply add to the total that I am still trying to resolve in this financial year”. He went on to say that the offers made available “are essentially the best I can make available in this financial year”, however, “we will continue our dialogue with the relevant trade unions”.15 The Committee explores the approach to public sector pay in the Scottish Budget 2023-24 later in this report.

The Deputy First Minister has confirmed that he does not expect to be able to carry over any resources from this year into the 2023-24 Budget “for the first time since this government took power”, which he notes “increases the scale of the financial challenge that we face in the next financial year”.15

The Committee is concerned that there is still uncertainty so late in the financial year around how the 2022-23 Scottish Budget will be balanced. While we recognise the challenges that the Deputy First Minister faces, we believe that this issue should be resolved as early as possible to enable sufficient time for transparency and scrutiny of final decisions. We ask the Deputy First Minister to continue to keep the Committee informed of decisions taken as he seeks to finalise the budget, and we look forward to scrutinising the Spring Budget Revision once it is laid before Parliament in the coming weeks.

We note that it is unlikely the Scottish Government will be in a position to carry over any resources, placing additional pressures on the 2023-24 Budget.

Scottish Budget 2023-24 and Scottish Fiscal Commission Forecasts

Overview

The Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) notes in its latest Forecasts the backdrop to the Scottish Budget 2023-24—

Following the Covid-19 pandemic, global events have continued to move quickly with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and rising energy prices. Closer to home there has been higher inflation, interest rates, and the cost-of-living crisis. As a result, the near-term outlook for the Scottish and UK economies has weakened significantly over the course of the past year. We now expect Scottish households to see the biggest real-terms fall in their disposable income since Scottish records began in 1998.4

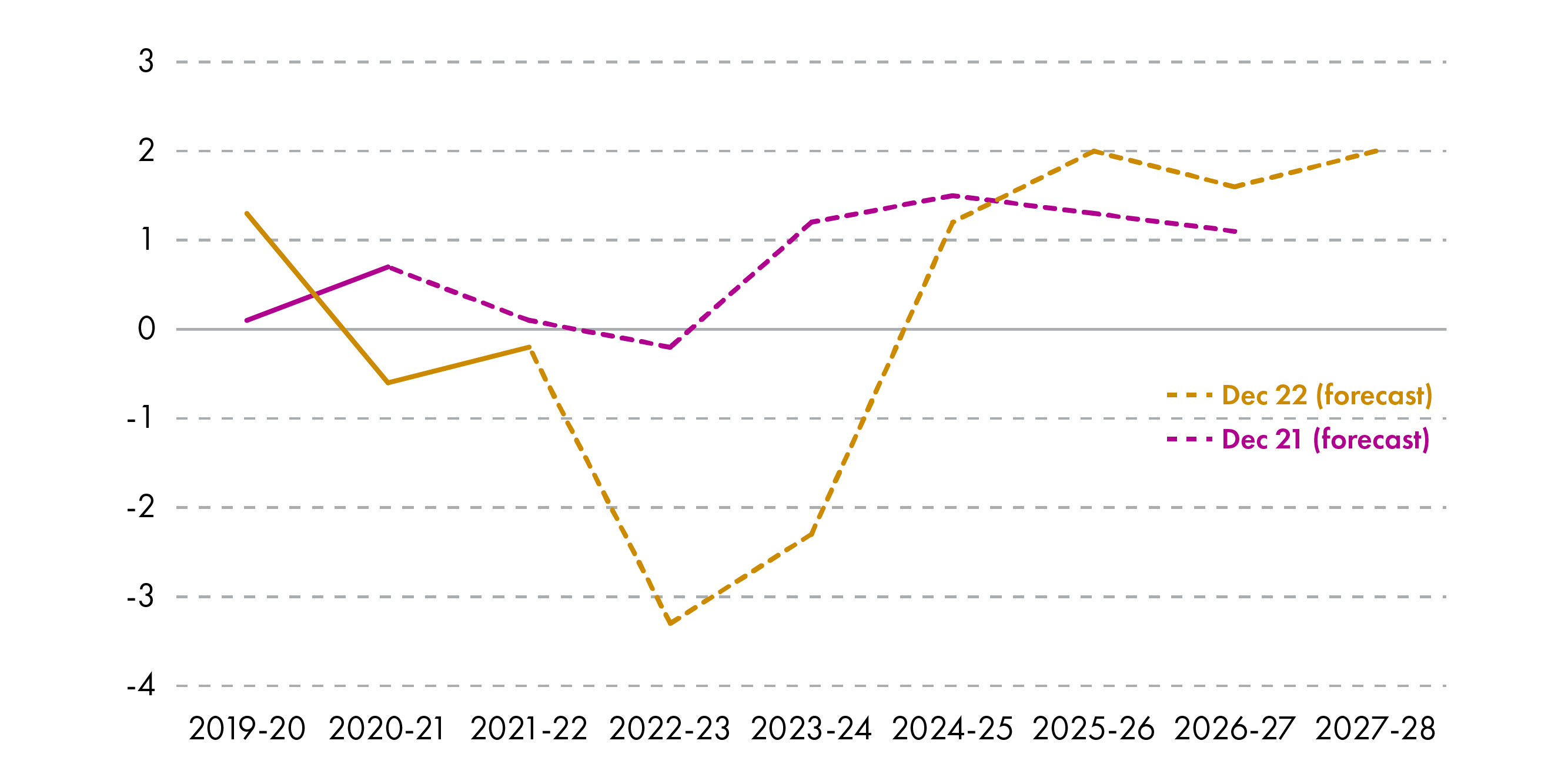

Figure 2 below sets out real disposable income per person growth forecast in Scotland for the next five years compared to the SFC forecasts in December 2021.

Figure 2: Real disposable income per person growth forecast, % change on the previous year  Scottish Fiscal Commission

Scottish Fiscal Commission

During evidence, the SFC explained that there is confidence that inflation will come down however, when it does, “our living standards will not suddenly go back to where they were, because our cost of living has gone up to 10% or even 15% for people on lower incomes, but earning and social security payments will have gone up by much less”. It advised that “even though inflation will be low, it will still feel much more challenging because the actual cost of living will now be higher”.

Inflationary pressures will continue to have a significant impact on the Scottish Budget in 2023-24. As a result, the SFC expects resource funding for 2023-24 to increase by £1.7 billion in nominal terms but only £279 million in real terms compared to the latest funding position for 2022-23.4 Resource funding makes up the majority of the Scottish Budget and is used to fund public services, goods and services, and social security payments. The SFC notes that “the difference of £1.4 billion in the value of the nominal and real 2023-24 Budget compared to the latest 2022-23 position shows the effect higher inflation is having, eroding the spending power of the Scottish Government”. Nominal resource funding for 2023-24, it confirmed, “has increased due to greater UK Government funding via the Block Grant”.4

According to the SFC, capital funding accounts for 12% of the Scottish Budget in 2023-24.4 This is used to fund longer-term investments, such as infrastructure and research and development. The SFC notes that the capital budget is flat in nominal terms between the latest position for 2022-23 (at December 2022) and the 2023-24 Budget, reflecting a real terms cut of £185 million. This pressure, it stated, is due to reduced UK Government funding for 2023-23 and the impact of inflation.15 The Deputy First Minister has explained that the Scottish Government will not be able to fund all the measures it had set out in its Capital Spending Review.

The SFC’s comparison is between the latest position for 2022-23 (at December 2022) and that of 2023-24. The Scottish Government presents its 2023-24 Budget against the baseline figures contained in the 2022-23 Budget and passed in February 2022. Using the Scottish Government’s measurements, resource is due to increase by 3.7% in real terms in 2023-24 and capital is set to fall by 2.9% in real terms. 1

The Foreword to the Scottish Budget 2023-24 document states that the Scottish Government wants “to create a Scotland that can eradicate child poverty, enable our economy to transition to Net Zero and create sustainable public services that support the needs of people”.1 The Social Justice, Housing and Local Government increases, by 8.2% (4.8% in real terms) in 2023-24, with social security payments a significant part of this, increasing in line with inflation (as at September 2022) by 10.1%. The Net Zero Energy and Transport portfolio also increases, by 5.6% in nominal terms and 2.2% in real terms. The Deputy First Minister in his Budget Statement to Parliament on 15 December 2022 noted that “the most precious of our public services, the one on which all of us depend, is our National Health Service”.16 The Health and Social Care portfolio grows by 6.2% portfolio (2.8% in real terms) in 2023-24.1

The Budget document also shows the total local government allocation for 2023-24 increasing by £637 million in cash terms, or £223 million in real terms, when compared to Budget 2022-23.1 COSLA argues that the actual cash increase announced by the Deputy First Minister will be much smaller once existing policy commitments are taken into account.

Budget lines for the Constitution, External Affairs; Rural Affairs and Islands; and Finance and Economy portfolios each fall in both cash and real terms in 2023-24.1

During evidence to the Committee on 10 January 2023, the Deputy First Minister explained his approach to developing the 2023-24 Scottish Budget—

I have taken the necessary steps to continue to maximise the Scottish Government’s support for people in Scotland during the cost-of-living crisis. The pressures on this budget cannot be overstated. … We are confronting the challenges that we face by increasing taxation for those who are most able to pay, to enable additional investment to be made in the national health service at this critical time. With this budget, we are choosing to invest in Scotland and focus on eliminating child poverty, prioritising a just transition to net zero and investing in our public services.5

The overall approach taken by the Scottish Government was discussed with Expert Panel Members during evidence. Professor Anton Muscatelli noted that “this year has been a kind of protection operation, if you like, to protect certain public services and welfare payments, so serious thought needs to be given to ensuring that growth can continue in the future, which will allow the tax take to increase”.15 The Expert Panel’s interim report states that the Scottish Government should achieve a balance between providing short-term support to vulnerable households and businesses; …[and] investing to grow and improve the productivity and resilience of the economy in the medium to longer term”. The Panel was asked during evidence whether this had been achieved in the Scottish Budget 2023-24. Professor Muscatelli responded that the Scottish Government “has done the best it can, given the rather difficult situation that we are in with regard to public finances of the UK and, therefore the devolved administrations”.15

Dr Mike Brewer described the budget as being “predominantly focused on dealing with the short-term challenges that are posed by the rising cost of energy and food”. He notes, “therefore, understandably, it does not give as much attention as the Deputy First Minister might have wanted to give to all the long-term challenges” and “that is, in part, because the fiscal situation does not allow the Scottish Government to make as much investment and do as much forward planning as it wants, and because there are real challenges this year”.15

GDP Deflator

Both the OBR and SFC use the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) deflator to adjust for the effect of inflation on public spending over time. The SPICe briefing on the Scottish Budget 2023-24 explains that the measurement of CPI inflation is not used as governments do not tend to purchase the same goods and services as consumers. SPICe explains that “in normal circumstances the GDP deflator is the best measurement of inflation for government spending …, however, the current high inflation is being driven by high energy prices which is an import cost, not covered by the GDP deflator”. It goes on to say that “this means that rather than running in line with CPI inflation of approaching 10-11%, the GDP deflator is considerably lower – for 2023-24 it is currently 3.2%”. SPICe adds that “all of this means that the ‘real’ cost of delivering public services at the moment, as measured by the GDP deflator, is likely to be artificially low with energy price inflation running so high”.

The SFC, in its Forecasts, similarly highlights this issue, stating that “the Scottish Government consumes imported commodities not captured by the GDP deflator, such as energy [and] public sector workers’ expectations of pay increases are likely to be linked more to CPI than to the GDP deflator”. The SFC goes on to state therefore that the real terms figures in its chapter on resource funding “potentially underestimate the true scale of inflationary pressure on some areas of Scottish Government resource funding”.4

The Committee therefore explored the appropriateness of using the GDP deflator as a measure of inflation for government spending. The OBR told the Committee that “the best way to adjust the cost of provision of such services for inflation [for public spending]—probably lies somewhere between the lower number of the GDP deflator and the higher number of CPI inflation”. However, it goes on to highlight that “in our central forecast, for what it is worth, that situation actually flits around—for example, in 2025-26, the rate of change in the GDP deflator is something like 1 or 1.5% higher than CPI inflation”.

The Deputy First Minister indicated that using the GDP deflator was important for consistency in the way in which documentation is presented. He went on to say that “although the numbers that I present are underpinned by the GDP deflator, I cannot ignore the fact that, in reality, the ability or capacity to spend is eroded by the effect of inflation”.5

The Committee recognises that the use of the GDP deflator to measure inflation for government spending in the current circumstances does not accurately reflect the real pressures on the Scottish Government’s spending envelope this year.

Transparency

The Committee in our Pre-Budget report endorsed an earlier recommendation by the SFC that it would “like the Scottish Government to publish its Budget later this year with information on how spending is split by Classification of Functions of Government (COFOG)”, a classification developed by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to present spending in a consistent way.2 The SFC said at the time of the recommendation that “currently the Scottish Government’s Budget documents focus on spending by portfolio area …, however portfolios change over time to reflect different ministerial responsibilities”, making it difficult to track spending over time. Using COFOG, it suggested “would provide a baseline level of spending for us to use in our Fiscal Sustainability Report and provide a benchmark for comparisons of the Scottish Budget in future years”.20

During evidence on 20 December 2022, the SFC reiterated that “COFOG is really helpful and important for our long-term fiscal sustainability work”.15 The Deputy First Minister confirmed in a letter to the Committee on 19 January 2023 that his intention is “to publish a COFOG analysis for 2021-22, 2022-23 and 2023-24, that will reconcile with the budget aggregates as included in the Scottish Budget 2023-24 [and] that this will be published before February recess”.

The Committee believes that publishing COFOG information will enhance transparency by enabling comparisons between years regardless of whether Ministerial portfolios change. We therefore welcome the Deputy First Minister’s commitment to publish COFOG analysis for the years 2021-22, 2022-23, and 2023-24, in the coming weeks.

Taxation

Overview

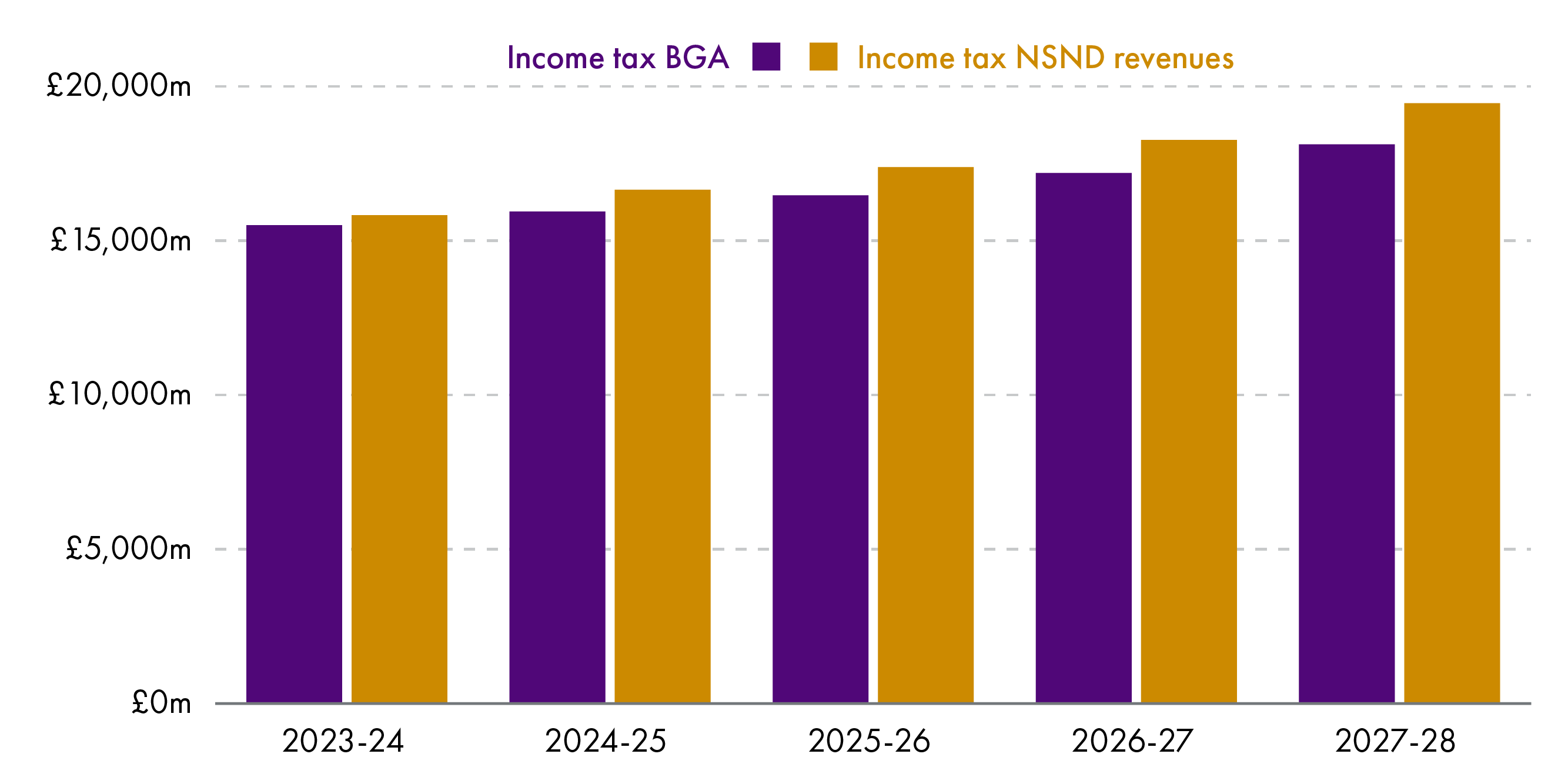

During evidence, the SFC told the Committee that despite a challenging backdrop, the net contribution of income tax to the Scottish Government’s 2023-24 budget has improved by £582 million since its December 2022 projections. This, it explained, was “due in part to last week’s Scottish Government policy changes [included in the Scottish Budget 2023-24], but also to other reasons including the revised data in the most recent figures from His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, which pointed to a relatively better tax position for Scotland and projected rising earnings”. It went on to suggest that “the positive income tax net position over the next five years marks a change in the funding position of the Government relative to what we previously forecast”. The SFC, however, pointed to “the caveats inherent in its assessment and the potential for change” which could affect these projections, such as behavioural change and lower earnings than forecast.15

The Scottish Government’s policy changes referred to by the SFC include plans to freeze all income tax thresholds, with the exception of the top rate, which is reduced to £125,140 in line with the UK Government’s plans. The higher and top rates are increased by 1p each, to 42p and 47p respectively from 6 April 2023. Proposed tax bands and thresholds for 2023-24 are set out in table 3 below.

| Bands | Band Name | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Over £12,570* - £14,732 | Starter | 19 |

| Over £14,732 - £25,668 | Basic | 20 |

| Over £25,668 - £43,662 | Intermediate | 21 |

| Over £43,662 - £125,140** | Higher | 42 |

| Above £125,140** | Top | 47 |

* Assumes individuals are in receipt of the standard UK personal allowance (£12,570 in 2023-24)

** Those earning more than £100,000 will see their personal allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000

The SFC explained that “the combination of inflation with fixed tax thresholds leads to more people moving into higher tax bands, known as ‘fiscal drag’ and tax revenues rise faster than nominal earnings”.15 It forecasts these income tax policy changes to raise an additional £129 million of income tax revenue in 2023-24, after taking account of any behavioural changes that might result.4 The Deputy First Minister indicated that the extra revenues from the 1p increases to the higher and top rates would “go towards the NHS getting an extra £1 billion in funding”.16

In relation to other devolved taxes, the Scottish Government has announced as part of the Scottish Budget 2023-24 that:

Land and Building Transactions Tax rates and bands will remain unchanged and the Additional Dwelling Supplement will increase from 4% to 6% from 16 December, raising £34 million additional revenue in 2023-24. The Committee has considered the secondary legislation to implement this change and reported its findings, separate to this report, on 20 January.

Changes to the Scottish Landfill Tax will see increases to the standard rate to £102.10 per tonne and to the lower rate to £3.25 per tonne in 2023-24, in line with UK Government policy.

Work will progress on a devolved replacement for the UK Aggregates Levy Tax, with legislation being introduced this parliamentary session. A consultation to inform development of the proposals closed on 5 December 2022.

It will freeze non-domestic rates poundage and continue to support the Small Business Bonus Scheme to remove 100,000 properties from rates and use the Non-Domestic Rates regime to further incentivise investment in renewables through new exemptions for on-site renewable energy generation and storage from 1 April 2023 until 31 March 2035. Local authorities will have “full discretion” over Empty Property Relief for Non-Domestic Rates, with “£105 million added to the settlement to support local priorities including the option to develop local relief schemes”.1

A Public Attitudes to Tax and Stakeholder Roundtable Summary is also included with the Scottish Budget 2023-24 this year and sets out views gathered by the Scottish Government during its pre-Budget engagement programme. It also draws on answers to a recent Scottish Social Attitudes Survey, which suggested, amongst other things, that 68% of people think that government should redistribute income from the better off to those less well off, and that 64% favoured increasing taxation to fund more public spending on health, education and social benefits.

In his statement to Parliament on 15 December 2022, the Deputy First Minister indicated that “where we have the power, we are choosing a different, more progressive path for Scotland”.16 During evidence to the Committee on 20 December, Professor Anton Muscatelli suggested that “Scotland is actually more progressive [in relation to taxation] than it is elsewhere in the UK, because it puts greater burden on those with higher incomes”. However, he suggested that “the one area that is probably less progressive is property tax [and it] is probably the one area where we would have most freedom to act”, as it is already devolved.15

The Deputy First Minister on 4 October 2022 told Parliament that “it is … essential that we engage more broadly on the tax and spending choices that are before us, including our commitments, priorities and values as a Government”. He said he would therefore publish a discussion paper alongside the Emergency Budget Review (which was itself published on 2 November), “to encourage public engagement on those important and difficult choices on tax and public expenditure”.

The Committee, in its Pre-budget Report, called for “an open and honest debate with the public about how services and priorities are funded, including the role of taxation in funding wider policy benefits to society” and suggested that “a wider public discussion on these issues would be helpful”.2 A discussion paper has not been published by the Scottish Government.

As highlighted in our Pre-Budget Report, the Committee believes that a public discussion around tax and spending choices would be helpful, and we are therefore disappointed that the Scottish Government has not provided, alongside the Scottish Budget 2023-24 as planned, its discussion paper on these issues. We seek an update on when this discussion paper will be published.

We also seek an update on the Scottish Government’s plans to reform council tax, given the evidence we heard that property tax is less progressive than other devolved taxes. In the meantime, we invite the Scottish Government to provide details of how it has assessed its approach to council tax and non-domestic rates policy against the strategic objectives in its Framework for Tax, as well as the outcomes of this assessment.

Behavioural Change

The SFC told the Committee that the Scottish Government “has to be careful when it thinks about how much additional revenue might come in [through tax rises], just because of people’s potential behavioural responses”. It went on to explain that “the evidence is that such tax elasticities tend to be quite high—or, at least high at the top end in relation to other parts of the income distribution—that is why our estimates with regard to the changes to the additional rate [of income tax] suggest that we do not expect them to raise that much revenue compared with the freezing of the intermediate and basic rates”.15

By way of example, the SFC highlighted that the 1p increase to the higher and top rates should raise £30 million in revenues in 2023-24, however, “when you add in the behavioural change, we think that the totality of that is only £3 million”.15 The Deputy First Minister acknowledged during evidence that “people may take steps to change their tax affairs to avoid those consequences” however, he said he believes that this “is morally wrong because people who live in Scotland have access to a set of provisions and services that are different from those that are available in the rest of the UK”. He highlighted what he described as a ‘social contract’, where people in Scotland can benefit from free prescriptions, no university tuition fees, greater access to early learning and childcare, and comparatively lower council tax than in the rest of the UK.5

When asked about the potential behavioural impact if the Scottish Government had raised the higher and top rates by 2p rather than 1p, the SFC said normally that effect would be linear. It explained that “the behavioural effect gets stronger, but the revenue you raise also increases”.15

During evidence, the Deputy First Minister accepted that the Scottish Government had to be mindful of potential behavioural changes when making tax policy changes. However, his view was that the changes made were “based on the principles that the Government adheres to, which are that we believe in progressive taxation and that higher earners should contribute more in taxation than has previously been the case”. The changes, he argued, “enables us to better and more substantively invest in public services and public priorities”. When asked why he settled on a 1p rather than 2p rise, he responded: “to go further might take us into territory that would create some wider difficulties for the Scottish tax base, and I need to be mindful of the importance of sustaining the Scottish tax base at all times”.5

Asked whether he was concerned that some “middle to upper earners” could feel that Scotland may not be the most attractive place in which to live, work and invest, the Deputy First Minister advised that top rather than middle earners were affected by the changes. He reiterated his view that “Scotland is a very attractive place for people to live and work in and that will be reflected in the judgments that individuals make”, highlighting the social contract, quality of life and access to facilities and services.5

The Committee notes that the 1p increase in income tax for higher earners is forecast to lead to revenues of £30 million, but with anticipated behavioural change reflected this figure reduces to £3 million. We believe that more needs to be done to understand the drivers for behavioural change and that, as a starting point, the Scottish Government should work with relevant bodies, such as HMRC and Revenue Scotland, to ensure that more data can be captured on the behavioural impacts resulting from these particular income tax changes. We further note that behavioural impacts will also arise in relation to the revenue collected through other devolved taxes.

The Scottish Government’s planned discussion paper on tax and spend presents a welcome opportunity to explore issues around behavioural impacts on tax revenues, and its plans “to strengthen the social contract between the Scottish Government and citizens of Scotland for the wider benefit of society”.

Earnings Growth and Labour Market Participation

The SPICe Briefing on the Scottish Budget 2023-24 notes that while Scottish taxpayers are paying around £1 billion more in income tax in 2023-24 than they would be under the income tax policy of the rest of the UK, the Scottish Budget 2023-24 is only benefitting by £325 million due to how the funding settlement under the Fiscal Framework works. It explains that “the gap arises because Scotland’s economic performance (in terms of earnings growth and employment) has been weaker and because Scotland has a different taxpayer mix (both in terms of numbers paying tax and also in the mix of higher and lower rate taxpayers)”.20

As highlighted earlier in the report, the SFC expects an improvement in the net income tax position in Scotland over the next five years due to a more positive outlook for the oil and gas sector, greater alignment of financial services in the UK and Scotland, and an expectation that Scotland will be less affected by rising interest rates on mortgage debt.4 Figure 3 below shows the forecast net income tax position over the next five years.

There are also emerging signs of positivity in the latest labour market data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) published on 17 January 2023. For the three months ending November 2022, Scotland saw record high employment at 76.1%, up 0.3 percentage points from the period June to August. The UK figure was static at 75.6%. The unemployment rate in Scotland remained at 3.3%, compared to 3.7% in the UK, while the inactivity rate for Scotland was 21.3% (-0.3). The UK inactivity figure was 21.5% (-0.1%).

The Committee explored in evidence the decline in participation rates following the Covid pandemic. The number of economically inactive people across the UK in August to October 2022 was 489,000 above pre-pandemic levels (January to March 2020). The latest ONS statistics state that economic inactivity was driven by those inactive because they are students, long-term sick, or retired.

Dr Mike Brewer suggested that “although the evidence is not clear, there is an emerging story that rising levels of ill health are beginning to hold back the economy [and] the fact that the health of the UK population is declining means that the nation is less productive than it would otherwise be”.15 The SFC noted that the growing numbers leaving the workforce “is a relatively new phenomenon, so we are all trying to understand just what that participation effect really means”. Dr Brewer suggested that “the data in Scotland slightly limits the extent to which we can identify where all that comes from, but obviously there is, in the background, a mixture of ill health and changing attitudes to work and participation”, adding “we will have to wait to see whether that is a permanent or, indeed, a growing feature of labour market participation”.15

As part of the Emergency Budget Review the Scottish Government removed around £54 million from the budget for employability in 2022-23. The Deputy First Minister explained that this was on the basis that “those employability resources were not committed” and that “we still had capacity in the existing programmes for individuals to enter employability activity”.5 This was a cause of concern for the Committee at the time and it therefore questioned this measure as part of its pre-budget scrutiny.

The Deputy First Minister reassured the Committee that the projected expenditure on employability is set to increase in 2023-24 and suggested that if demand for these programmes exceeds capacity in year “that is obviously an issue for substantial consideration”.5

The emerging picture of people leaving the workforce due to ill health or changing attitudes to work following the Covid-19 pandemic is concerning and compounds existing labour market participation challenges in Scotland. The Committee asks the Scottish Government what steps it is taking to understand the specific reasons for economic inactivity in Scotland and how it will encourage greater take-up of employability programmes in 2023-24, including from those currently inactive.

Growing the Tax Base and Productivity

The Committee has a continuing interest in exploring how to grow the tax base in Scotland, in light of the demographic and productivity challenges, and the significant proportion of higher earners working in the oil and gas sector (a sector likely to be impacted by the focus on more carbon-efficient energy options). The SFC told the Committee that “if you want more income tax, it is not just about growing the total number of people—it is also about growing the number of high-earning jobs, because that is where you take higher taxes”, adding “that comes down to having a highly productive economy that is creating lots of those jobs”. It went on to say that, in its Fiscal Sustainability Report to be published in March, it would “speak more … about the challenges that Scotland faces with its ageing population”, adding that “productivity is key [and] is the one thing that drives growth in the economy”.15

More broadly, a key theme of the Expert Panel’s final report and evidence was the need to grow the Scottish economy. It argued that it is “important to prioritise improving wellbeing and productivity across all areas of government spend” as “public services and government spending provide an important stabiliser during economic downturns and can help maintain the productive capacity of the economy and the wellbeing of citizens”. Professor Muscatelli suggested in evidence that the Scottish Government’s National Strategy for Economic Transformation (NSET) “must be pursued with vigour because it is aimed at genuinely lifting business investment and productivity”. He added that “if I were in Parliament, I would be asking for evidence of how that is driven and what co-investment is being done between the private and public sector in those areas of activity in the budget that the Deputy First Minister announced”. Professor Muscatelli went on to say that “we also need to consider what we can do at a UK level to bring in the skills that we need but which we cannot generate ourselves in short order, so that we are not held back over the next few years”.15

Some further details of the priorities and budgets attached to delivery plans under the (NSET) are set out in the Scottish Government’s response to the Committee’s Pre-Budget Report recommendations. This includes investment of £500,000 to run the Digital Productivity Lab Project and expanding the Scottish Council for Development and Industry-led network of Productivity Clubs for businesses.3

The Deputy First Minister was asked why there is no mention in the Scottish Budget 2023-24 document of the Scottish Government’s commitment to sustainable economic growth. He responded that “the way in which I have presented the economic argument in the Budget document is essentially to say that our economic ambitions must be realised through the delivery of a just transition to net zero [and] that will involve the channelling of our economic activity to ensure that, out of the transition to net zero, Scotland realises the economic opportunities that will be available to us principally through the delivery of the NSET”.5

He went on to reiterate that boosting productivity and earnings within the Scottish economy is the focus of the NSET and also provided more examples of the Scottish Government’s actions under the strategy. This included putting in place regional economic strategy mechanisms, such as providing funding in the North-East of Scotland to support transition away from the oil and gas sector, investment in tech development in Scotland, and building on progress over the past five to ten years. He also indicated that “we have to engage substantially and enhance the already developing collaborations between University research sector and business community”.5

The Deputy First Minister further added that “the data speaks for itself in the sense that, outwith the south-east of England and London, Scotland remains the most attractive and successful destination for inward investment of any other part of the UK”. He pointed to improved earnings growth forecasts by the SFC “as an indication of the progress that we can expect to make on productivity”.5

The Committee has repeatedly highlighted the long-standing challenges of demography, low productivity and the need to grow the tax base especially in high-wage industries, which each need to be addressed. We consider the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s first Fiscal Sustainability Report to be a valuable contribution to the debate around meeting these challenges, and we look forward to scrutinising the report once published in March.

We heard from experts that the National Strategy for Economic Transformation must be “pursued with vigour”, given the importance of growing the economy. The Committee therefore invites the Scottish Government to provide evidence of how it is driving forward the actions in the Strategy, including progress with encouraging co-investment between public and private sectors. We also seek confirmation of whether current financial constraints will impact on delivery of the Strategy and, if so, in what areas.

Spending Priorities

Resource Spending Review

The Scottish Government’s Resource Spending Review (RSR) published in May 2022 sets out the high-level parameters for resource spend within future Scottish Budgets up to 2026-27 and provides a long-term plan focused on delivering its outcomes. Priorities in the RSR were to improve outcomes for children living in poverty, progress in achieving the just transition to net zero, reforming public services, and transforming the economy “to enable growth, opportunity and a sustainable outlook for our future”.31

In her Foreword to the RSR, the then Cabinet Secretary for Finance and Economy stated that her aim “is to provide as much clarity and certainty as I can to public bodies, other delivery partners, businesses, communities and households about the Government’s forward spending plans, so the fiscal context and the drivers for reform are clear”. She went on to say that, while the figures in the spending review are not fixed annual budgets and there are uncertainties and issues outwith the Scottish Government’s control, “the spending review provides a clear planning scenario for annual budgets over the remainder of the Parliament”.31

The Deputy First Minister was asked during evidence about the current status of the RSR. He responded that the RSR “remains a very relevant consideration for all stakeholders who are concerned with the public finances, not necessarily because of the precise details in it, but because it shows the shape of how public finances are developing”. He explained that “when the RSR was set out, we envisaged that there would be two early tough years and then two better years …, however, given the UK Government’s statement in November, we will have two relatively less painful years to begin with and then two much more painful years”. He added that “I think the direction of travel that is set out in the RSR remains absolutely valid, although some of the numbers might be different as a consequence of what has happened”.5

When asked on what basis bodies such as local government or the university sector should use the RSR for forward planning, the Deputy First Minister indicated that “organisations and sectors should draw from my original remarks the conclusion that, to be frank, 2023-24 and 2024-25 will be the buoyant years and the two after that will be much more difficult as a consequence, and that that will have to play through into all sectors of the public finances”.5

The Committee agrees with the Cabinet Secretary for Finance and Economy that the aim of the Resource Spending Review should be to provide as much clarity and certainty as possible and a clear planning scenario for annual budgets over the remainder of the Parliament.

We are therefore concerned that the RSR no longer provides the level of certainty or a clear planning scenario that was intended when it was published in May 2022. This effectively leaves public bodies in the dark when trying to manage their finances and plan for future delivery and reform of services in the years ahead. While we appreciate the challenges arising from the current levels of volatility in public finances, the Scottish Government must provide more clarity and certainty about the resource spending position to ensure confidence around the sustainability of Scotland’s finances. We therefore urge the Scottish Government to update the RSR as early as possible.

Social Security Expenditure

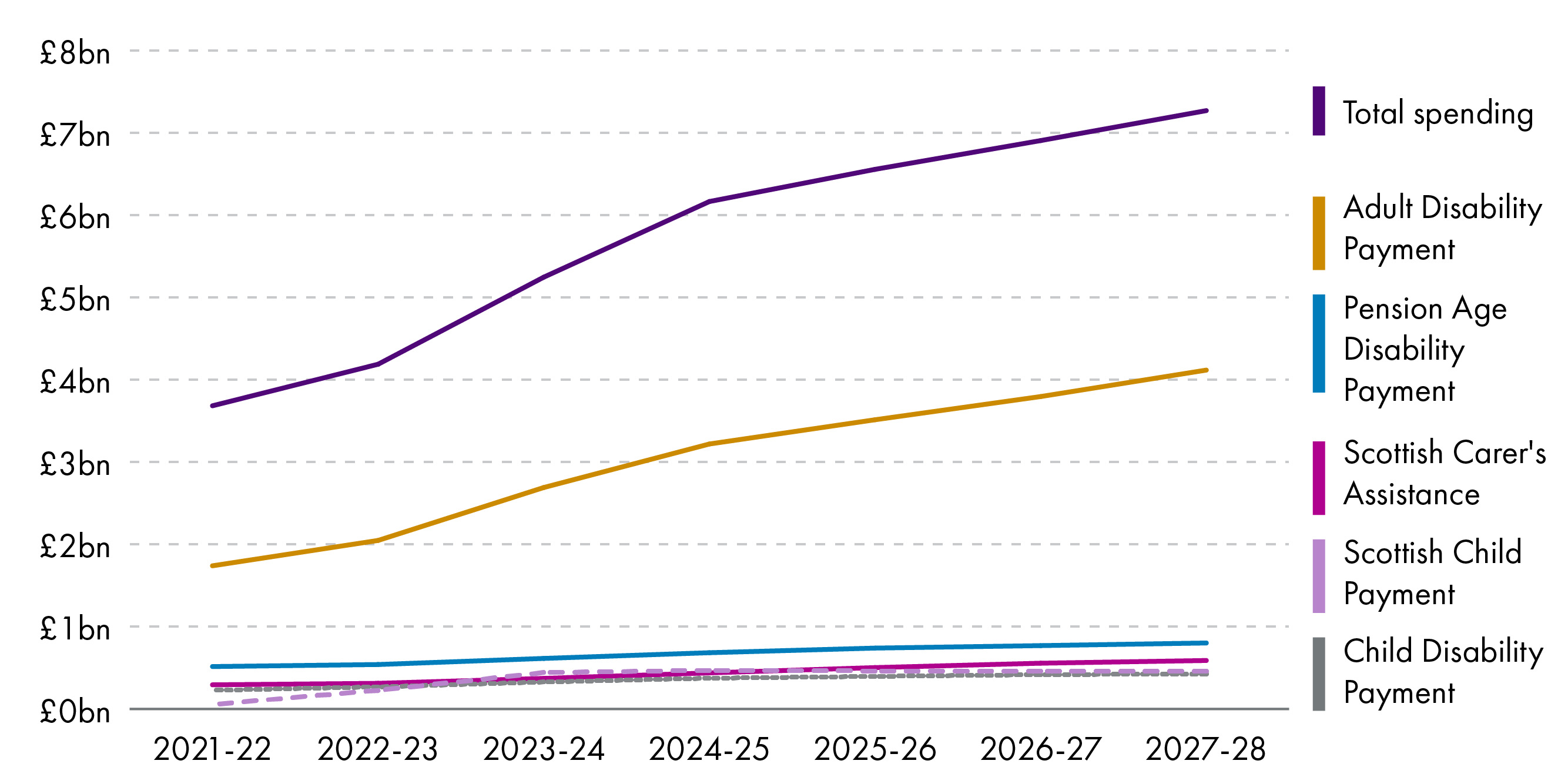

The SFC forecasts that social security payments could cost £5,244 million in 2023-24 growing to £7,267 million in 2027-28. It explains that “the increase in expenditure over the forecast is a result of more people receiving the payments and on average people receiving higher payments over time, with inflation being a major factor in this.”4 The SFC told the Committee in evidence that “the gap between our forecast social security spending and the funding received from the UK Government (the Block Grant Adjustment (BGA)) is projected to widen”. This it argues reflects “the extra costs of delivering some payments such as adult disability payment, which we forecast to run ahead of the BGA, and distinct payments such as the child payment, which have to be funded from within Scottish Government budget resources”.15 The SFC estimates this gap to be £776 million in 2023-24 growing to £1.4 billion by 2027-28.4 Taking the same approach as the UK Government, all devolved benefits will be uprated in April 2023 in line with inflation (at September CPI of 10.1%) at a cost of £428 million. The Scottish Child Payment continues to be uprated to £25 per week, as announced in November 2022.1

The SFC expects the adult disability payment to increase from 47% of total social security spending in 2021-22 to 57% by 2027-28. The next most significant policies are the Pension Age Disability payment (11% in 2027-28), the Scottish Carer’s Assistance (8% in 2027-28), the Scottish Child Payment (6%) and the Child Disability Payment (6%).4 Figure 4 sets out SFC forecasts for social security payments over the forecast period.

The Scottish Budget 2023-24 document states that “a key priority is the design, development and implementation of our social security powers and delivery of twelve benefits through Social Security Scotland, including the Scottish Child Payment, at £25 per week, that is now available to all eligible under-16s, and complex disability benefits”. It notes that “we have built a social security system that treats people with dignity fairness and respect, helps people in need, and supports independent living”.1

During evidence, the Deputy First Minister reiterated that the Scottish Government’s approach to welfare payments “is a matter of political choice”. He went on to say that “we have decided to take measures to support individuals who face significant challenges”, adding “a particular illustration of that is the Scottish Child Payment, which accounts for a substantial part of the divergence in expenditure to which you have referred—that is an active political choice”.5

When asked when he expected the child payment policy to result in moving more people out of poverty, and thereby reductions to the social security bill, the Deputy First Minister responded that the statutory targets in place “are essentially the milestones that we have to achieve, but the Government is working to make progress within an earlier timescale”.i He added that “I am optimistic that the measures that we are taking are working effectively in that direction”.5

Responding to a question on whether more funds could be spent on employability programmes to reduce the welfare bill, the Deputy First Minister told the Committee “it is undeniable that that could be done, but I have to make a judgment about what resources are available”. He also pointed to learning arising from the Dundee Pathfinder Programme “on what works in supporting people out of economic inactivity and into productive economic activity, which would influence the deployment of future programmes”.5

In response to the concerns set out in our Pre-Budget Report regarding the potential impact of cuts in year to the employability budget in 2022-232, the Scottish Government said that it will “reinstate funding to support the employability response to child poverty, with £69.7m committed in the Budget in recognition of the important role that employability support has to play in tackling child poverty”.3

The Committee is interested in the Scottish Government’s work on employability programmes as part of a balanced approach to making progress in meeting its child poverty targets. We would therefore welcome an update on the outcomes, costs and long-term savings arising from the Dundee Pathfinder project which the Deputy First Minister highlighted as providing some good learning that would influence future such programmes.

Health and Social Care

According to the Scottish Government, the allocation for the Health and Social Care portfolio budget for 2023-24 “represents an increase of over £1 billion”.1 The Deputy First Minister explained that his “recollection is that the Barnett consequential that arose was of the order of £300 million” and that the “Scottish Government is passing [this] on in full, but we are going much further in the allocation of resources that we are making”.5 The pay settlement currently being offered for 2022-23 amounts to an additional £515 million. This would set baseline costs for the 2023-24 Budget and therefore a significant amount of the increase in the Health and Social Care Budget could be absorbed by additional pay costs.

The Scottish Government has also committed to increase pay for adult social care workers to £10.90 per hour, which comes at an estimated cost of £100 million for 2022-23.20 As requested, the Deputy First Minister provided follow-up information in writing confirming that “the cost of each £1 uplift to the minimum hourly rate for adult social care workers in the third and independent sectors costs approximately £250 million”. He explained “this is what it would cost to fund a minimum hourly rate of £11.90, in addition to the £100 million already in the 2023-24 Budget for the £10.90 minimum rate [and] does not include social care workers employed by local authorities who are covered by local government pay negotiations”.14

Asked to specify the sum that has been allocated in the Scottish Budget for setting up a National Care Service, and whether it reflects the figures in the original Financial Memorandum of between £60 and £90 million, the Deputy First Minister said that “the national care service expenditure will sit within an overall budget in excess of £1 billion—£1.1 billion” a substantial part of that being to increase pay for social care staff. He also advised that the Committee will receive an updated Financial Memorandum to reflect the Scottish Government’s up-to-date assessment of how the national care service will be taken forward, as requested during our scrutiny of the National Care Service (Scotland) Bill.5

The Scottish Budget 2023-24 document does not specify what level of spend has been incorporated into the relevant budget line in relation to the establishment of the National Care Service. It is therefore difficult to determine whether the amount allocated in the budget reflects the figures in the original Financial Memorandum (FM) for the Bill of between £60 million and £90 million. The Committee welcomes the Deputy First Minister’s commitment to provide an updated FM for the National Care Service (Scotland) Bill and looks forward to examining it in detail ahead of the Stage 1 debate on the Bill.

Given this is a flagship policy with considerable costs attached, the Committee invites the Scottish Government to consider extrapolating the budget lines for establishing the National Care Service from other health spending in the Scottish Budget, to allow this spend to be identified and tracked.

Capital Spending

In total the amount of capital spending available to the Scottish Government in 2023-24 is £6,363 million. SPICe explains in its Briefing on the 2023-24 Budget that, “when all sources of capital funding are taken into account, the total capital budget is flat in cash terms”.20

The SFC noted that “the Scottish Government’s capital budgets can be offset to some extent through its capital borrowing powers [under the Fiscal Framework] and that in 2023-24 it plans to use £250 million of capital borrowing and top that up with £200 million of other sources of funding for capital”. If that £200 million is not available, the Scottish Government plans to draw down the full £450 million permitted by the Fiscal Framework for capital borrowing each year. It noted that “of course, the more that is borrowed on capital, the more quickly the Fiscal Framework limit is reached, and the more borrowing costs are embedded into the future”.15 The SFC has assessed this borrowing plan to be reasonable though it questions whether the full £200 million will materialise “given UK Government tightening on capital spending and Scottish Government plans to draw down all reserve funds in 2022-23”.4

Professor Muscatelli commented in evidence “I have no doubt that the lack of borrowing powers, particularly around capital, must limit the scope of action of any Government”, adding “I think that this is one of those areas where the current devolved settlement is what it is; but if you look around at other federal tax systems, you see that a number of other jurisdictions have the ability to borrow more for capital spending”.15

Dr Brewer told the Committee that “we have been urging the UK Government not to make cuts to its capital spending plans and, in our [Expert Panel] report, we encourage the Scottish Government to do what it can to offset those cuts, … however, the Scottish Government is limited in how much it can offset”. The Expert Panel noted in its report that “Scotland is constrained by reliance on the UK Government for capital grant allocations as well as limited capital borrowing powers.” As such, the UK Government’s decision not to enhance capital funding given the high levels of inflation “will lead to a steep decline in the purchasing power of Scottish Government investments and will lead to a reprioritisation of projects.”30 Dr Brewer suggested in evidence that this may hamper the Scottish Government’s ability to meet its net zero targets and damage the economic recovery.15

When asked to respond to this assertion by Dr Brewer, the Deputy First Minister spoke about the Scottish Government’s borrowing intentions in 2023-24 as a way of boosting purchasing power. He went on to say that “judgments will be made during the financial year—particularly more towards the end of it—about the volume of actual borrowing that is required”, adding “we do not want to borrow if we have no need to borrow to support the projects that we have underway”.5

He explained that the Scottish Government “fully intend to deploy £6.3 billion of capital expenditure, … and so business organisations can look at that …[and] take some confidence that the Government will invest heavily in the country’s capital estate, but certain projects might not proceed as originally timetabled, although they will be at the margins of the programme”. He said, however, “there is a set of sensitive judgments to be made about whether we should take forward all the capital projects that we would have ordinarily been committed to taking forward, given the effect of price inflation on those projects at this moment in time”. He explained that construction projects “are a significant concern at the moment because of price inflation on raw materials”, whereas other projects such as higher education research expenditure, which falls within capital budgets, is not affected to the same extent.5

In our Pre-budget Report, the Committee noted that the Scottish Government’s Targeted Review of Capital Spending (2023-24 to 2025-26) showed an increase in capital funding for net zero programmes over the next three years and sought clarification on whether these funding allocations might be affected given the increasing pressures on the Scottish Budget 2023-24.2 The Scottish Government responded that “net zero is one of three priorities in the Scottish Budget and progress is being made towards targets”. Further emissions cuts, it suggests, “will involve some genuinely difficult decisions for Scotland requiring significant long-term private investment and behaviour change, and discussions are ongoing on how best to secure the financing that will be required".3

The Climate Change Assessment of the Budget is a new section in the Budget document providing an overarching narrative detailing policy and spending across portfolios which are aimed at delivering the Scottish Government’s ambition of a just transition to net zero. The Scottish Government notes that total emissions are down by 51% since the base year of 1990. However, the Government also notes that the scale of change required to reach remaining targets is “significant” and will need to be achieved through “targeted, impactful and long-term investment”.1

The Budget 2023-24 document states that the Net Zero Energy and Transport portfolio increases by 5.6% in nominal terms and 2.2% in real terms.1 In his Budget Statement to Parliament, the Deputy First Minister set out a series of initiatives to support the economy to transition to net zero, including £366 million planned investment in the heat in buildings programme to decarbonise heating, £244 million in the Scottish National Investment Bank, and £50 million to deliver the next phase of the just transition fund for the north-east and Moray. Its plans to decarbonise transport include investing £60 million in electric vehicle charging infrastructure, £1.4 billion to maintain, operate and decarbonise rail infrastructure, and £200 million in active and sustainable travel.16

Professor Muscatelli emphasised that “the drive to net zero can happen in two ways, the first of which is to simply import technologies and deploy them in Scotland, [but] although that will create jobs, it will not create well-paid jobs across the whole value chain”. The second way was to make sure that highly skilled innovation jobs are created, in addition to some manufacturing opportunities. He argued that innovation and co-investment in the research sector needed to be funded to encourage companies to locate in Scotland.15

The Deputy First Minister explained in evidence to the Committee that “our economic ambitions must be realised through the delivery of a just transition to net zero, [which] will involve the channelling of our economic activity to ensure that, out of the transition to net zero, Scotland realises the economic opportunities that will be available to us principally through the delivery of NSET”.5

The Committee notes from the Scottish Government’s Response to our Pre-Budget Report that work is underway between officials to develop a Terms of Reference for the Fiscal Framework Review, “which will be agreed by Ministers in the coming months”. In our view the Review is long overdue, and we are therefore disappointed with the lack of progress and continued delays. We urge both Governments to agree to the Terms of Reference and to publish the Independent Report that precedes the Review without further delay.

The Committee notes that the Scottish Government intends to borrow £250 million to boost its capital funding, rising to £450 million in the event that the sum of £200 million does not materialise from other sources.

Nevertheless, the Scottish Government will not now be able to deliver all the capital projects that it had planned, given the real terms cut to its capital budget by the UK Government. We would welcome details of those projects that will be deprioritised along with confirmation of the Scottish Government’s approach to securing the “significant long-term private investment” that it indicates will be required to achieve further emissions reductions.

We also request confirmation of how the cuts to the capital budget for 2023 will impact on the Scottish Government’s ability to achieve its net zero targets and ambitions under its targeted review of capital spending as well as its impact on delivery of the National Outcomes.

National Performance Framework

The Scottish Government introduced the National Performance Framework (NPF) in 2007 to provide an outcomes-based framework to underpin the delivery of its policies. In our report on the National Performance Framework: Ambitions into Action and in our previous pre budget and budget reports we have consistently made recommendations aimed at closer alignment between the National Performance Framework and those who advise and take funding decisions in the Scottish Government in order to better support the delivery of the National Outcomes.

Responding to the Committee’s NPF Report, the Scottish Government explains that the Scottish Budget funds the delivery of Scottish Ministers’ priorities to achieve the National Outcomes identified in the NPF and that—

As a government, it is critical that we have a good understanding of how the money we spend contributes to our short-, medium- and longer-term outcomes – including the extent to which it helps us make progress towards our National Outcomes in a meaningful way.

Building on the enhanced prominence of the National Outcomes in the Budget, Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement and the Consolidated Accounts will, it explained, also continue to strengthen its approach to better link spending with outcomes.35

In his response to the Committee’s Pre Budget 2023-24 Report, the Deputy First Minister explained that “it is challenging to identify in a meaningful way the individual annual impact of multiple budget lines on the delivery of longer term, complex National Outcomes”. Instead, “the Scottish Government will develop an approach centred around multi-year programmes, the associated outcomes and the annual spend profiles attached”.3

The Scottish Budget for 2023-24 was, the Deputy First Minister explained, “a particularly challenging one to construct” because of a range of “unprecedented circumstances” including to volatility from factors such as the cost-of-living crisis and the impact of inflation. He added that with this budget, “we are choosing to invest in Scotland and focus on eliminating child poverty, prioritising a just transition to next zero and investing in our public services.” He went to quote Professor Muscatelli of the Expert Panel that “there is no doubt that, given a fixed budget and rising salary costs, you will have to make difficult choices about what services you can and cannot provide”.5

The Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement published alongside the Scottish Budget 2023-24 identifies which are the primary National Outcomes relevant to each portfolio and a summary of the NPF is also included in the Strategic Overview part of the Scottish Budget 2023-24.

The Committee notes that the Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement accompanying the Scottish Budget 2023-24 does not explain the impact on the delivery of National Outcomes of the Scottish Government’s decision to focus its Budget for 2023-24 on three priorities. We also note that the Scottish Government provides commentary on how the budget impacts, by portfolio, on equality and fairness, and we recommend that in future years a similar approach is taken with regard to the impact of the Scottish Budget on National Outcomes.

We also request further information from the Scottish Government on its proposed approach to better linking the impact of budget lines to National Outcomes being “centred on multi-year programmes, the associated outcomes and the annual spend profiles attached”. We further seek timescales for completion of this work.

The Scottish Government has confirmed that it proposes to bring forward a Wellbeing and Sustainable Development (WSD) Bill aimed at strengthening Scotland’s National Outcomes and embedding wellbeing and sustainable development principles in decision-making. This Bill will also ensure “that the transition to a wellbeing economy has the interests of future generations built into the decisions made today”. To achieve this, “the proposed Bill may require duties to be placed on Scottish Ministers, public bodies and local authorities, which clarify the extent to which they can be systematically and consistently held to account for their contribution towards National Outcomes.”

The Committee notes that the Scottish Government has confirmed that the detailed proposals for the Wellbeing and Sustainable Development Bill will not be forthcoming until after the next statutory Review of the National Outcomes, which itself must start no later than June 2023 and is planned to conclude later in 2023. The Committee therefore requests confirmation of when this Review will begin. We also ask the Scottish Government to consider any changes as part of the Review of National Outcomes that would better link the impact of budget decisions to the delivery of National Outcomes.

Equalities

The Equality and Fairer Scotland Statement accompanying the Budget sets out where the Scottish Government is proposing to spend money and how it aims to reduce inequality. In it, the Scottish Government explains how embedding human rights principles of transparency, participation and accountability has informed the budget.36

The Committee, in our Pre-Budget Report, noted that this Statement is designed to assess where the Scottish Government is proposing to spend public money and how it aims to reduce inequality. We asked the Scottish Government to put in place robust and transparent processes to evaluate all policies and outcomes for gender impact.2 The Scottish Government, in its response, stated that “we accept the principle of integrating intersectional gender analysisi into our policy making and are taking this forward as part of our wider work on equality and human rights budgeting”.3

The Committee asks for details of how the Scottish Government is taking forward "integrating intersectional gender analysis to its policy making as part of its wider work on equality and human rights budgeting", and to what timescale. We again seek evidence to support how this approach will lead to robust and transparent processes to evaluate all policies and outcomes for gender impact.

Following on from the SFC’s evidence to the Committee in June 2022 on its fourth Statement of Data Needs, the Committee in September 2022 wrote to Social Security Scotland (SSS) setting out our concerns that the SFC is no longer receiving the same level of detail in the data provided by SSS as it previously received from the Department for Work and Pensions. SSS responded in October stating that it “recognised the importance our data plays in the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s forecasts” as was developing a new Data Strategy with stakeholders. It added that as a new organisation “while we continue to work to improve the content of our statistical publications, this will need to be balanced with a continuing programme of benefits delivery.” In that regard Scottish Fiscal Commission requests will be considered as part of this work.39

During evidence on the Scottish Budget 2023, the SFC explained that “we do not have the information on sex and gender for child disability payments yet, which is a challenge for our forecasting”. They went on to say that “it is crucial to understand the data about sex, which has a potential impact on our take-up forecasts”, adding “we lack any clarity from SSS about when it will give us the data obtained from equality monitoring forms”.15

The Committee plans to pursue with Social Security Scotland when it will provide to the Scottish Fiscal Commission the data obtained from equality monitoring forms for child disability payments, including on sex and gender, given the SFC has confirmed that this has a potential impact on the robustness of take-up forecasts.

Public Sector Pay

In a departure from previous years the Scottish Government did not publish its Public Sector Pay Policy for 2023-24 alongside its Budget. The Scottish Government’s Public Sector Pay Policy, in previous years, covers the Scottish Government’s own staff and around 50 public bodies. The pay policy does not apply directly to all public sector staff, with large parts of the public sector having their pay determined by separate pay determining bodies. With that said, decisions made by these bodies are often in line with the Scottish Government’s pay policy – as last year’s 2022-23 policy noted—

This policy also acts as a reference point for all major public sector workforce groups across Scotland including NHS Scotland, fire-fighters and police officers, teachers and further education workers. For local government employees, pay and other employment matters are delegated to local authorities.

However, on 15 December 2022, the Deputy First Minister explained that—

Given the uncertain inflation outlook and the need to still conclude some pay deals for the current year, I am not publishing a Public Sector Pay Policy for 2023-24 at this stage. We will of course continue to collaborate with trade unions and public sector employers on fair and sustainable pay and will look to say more on our approach for 2023-24 in the new year.16

When questioned by the Committee about the implications of not having a public sector pay policy for 2023-24, the Deputy First Minister pointed to the shift in pay parameters that have occurred in 2022-23 as a result of rising inflation—

...having set a pay policy at 2 per cent when inflation was benign, we then found ourselves in a completely different situation. I question the value of having a pay policy, because I do not think that it actually provides much guidance. The 2 per cent policy provided zero guidance to people as to how they were to navigate this. During the financial year, we put a lot of arrangements in place within Government. I chaired a regular discussion between ministers across the Government to consider the current negotiations and give guidance as to what we considered acceptable in relation to resolving these questions. Given the volatility that we have, I do not think that a pay policy would help to shape the context.5

The impact of inflation has had a material impact on the overall size of the public sector pay bill in 2022-23 compared with what was budgeted for. Table 4 (below) sets out the pay bill parameters assumed in the current year’s budget. This has been supplemented by revisions to the NHS staff deal adding £515 million, and a revised settlement for local government workers adding £260 million to the pay bill. Based on current figures, revised pay deals could take this year’s (2022-23) pay bill to around £23 billion.

| Baseline Pay bill 2022-23, £ millionPay policy as announced on 9 Dec 2021 | Full-Time Equivalent StaffPay policy as announced on 9 Dec 2021 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sector | ||

| NHS Agenda for Change (AfC) Staff (nurses, allied health professionals, clerical and administrative staff) | 6,937 | 137,000 |

| NHS Medical & Dental Staff (Employed Hospital Doctors and Dentists) | 1,873 | 14,000 |

| NHS - Senior Managers | 52 | 500 |

| NHS Sub Total | 8,863 | 152,000 |

| Police (Officers only) | 1,060 | 17,000 |

| Fire | 247 | 8,000 |

| Core SG, NDPBs, Public Corporations, Departments and Agencies. (all bodies subject to the public sector pay policy) | 2,279 | 44,000 |

| Further Education | 530 | 11,000 |

| Judiciary | 50 | - |

| Other Sub Total | 4,165 | 81,000 |

| Teachers (and associated teaching professionals) | 3,497 | 58,000 |

| Local Government (non-teaching) | 5,607 | 156,000 |

| Local Government Sub Total | 9,104 | 214,000 |

| Total | 22,132 | 447,000 |

Source: Scottish Government

Table 4 also shows that the public sector pay bill this year supports the employment of 447,000 full-time equivalents (FTEs) across the devolved public sector. The Resource Spending Review (RSR) stated that—

we propose an approach which aims to hold the total public sector pay bill (as opposed to pay levels) at around 2022-23 levels whilst returning the overall size of the public sector broadly to pre-COVID-19 levels. This will enable space and flexibility for fair and affordable pay increases that support the lowest paid in these challenging times.

Returning the public sector to pre-Covid levels implies a reduction in the headcount of the public sector of around 30,000. Given high levels of inflation this year, it may be that the size of the public sector requires reductions over and above that figure in order to meet the Deputy First Minister’s proposal to hold the public sector pay bill to around 2022-23 levels.

The Deputy First Minister confirmed in evidence that it remains the Scottish Government’s intention to return the public sector headcount to pre-pandemic levels, noting that “in the budget arrangements, there will be consequences that will have an impact on the size and scale of the workforce”.5

The Committee acknowledges the difficulties arising from soaring inflation this year and the knock-on implications for public sector pay and public spending overall. Nevertheless, the Committee was disappointed there was no detail in the budget on whether or not the Resource Spending Review targets around public sector pay and headcount remain, and, if so, how these might be achieved.