Finance and Public Administration Committee

Report on the National Performance Framework: Ambitions into Action

Introduction

In 2007 the Scottish Government introduced the National Performance Framework (NPF) - a new outcomes-based Framework to underpin the delivery of its policies.

The Scottish Government explains that the NPF sets out “our ambitions, providing a vision for national wellbeing across a range of economic, social and environmental factors.” It also sets out the “strategic outcomes which collectively describe the kind of Scotland in which people would like to live and guides the decisions and actions of national and local government”.1 To achieve those outcomes, the NPF aims to get everyone in Scotland to work together, including national and local government, businesses, voluntary organisations, and people living in Scotland. There are 11 National Outcomes, which are measured for progress against 81 National Indicators.

In 2015 the concept of the National Outcomes was enshrined in law as part of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 ("the Act") which requires the Scottish Government to review its National Outcomes every five years and to regularly report progress towards them. It also sets out consultation requirements, including with the Scottish Parliament. The Act requires that public bodies, or those that carry out public functions must "have regard to" the National Outcomes in carrying out their devolved functions.2 The next review of the National Outcomes is anticipated to begin later this year and conclude in 2023.

The Finance and Public Administration Committee (FPAC) was established in Session 6 with an explicit remit to scrutinise the NPF and we therefore expect to be the lead Committee for that review work. Other Parliamentary committees will also have an interest in the National Outcomes and National Indicators relevant to their remit.

In advance of the statutory review of the National Outcomes, the Committee launched an inquiry on 1 March 2022 to establish how the NPF and its National Outcomes shape Scottish Government policy aims and spending decisions, and in turn, how this drives delivery at national and local level. The inquiry also builds on our previous findings such as in our Pre-Budget Report, published on 5 November 2021. In that report we pointed to the upcoming review of the National Outcomes as an opportunity to “reposition the NPF at the heart of government planning, from which all priorities and plans should flow”. We went on to ask the Scottish Government to consider how the NPF could be more closely linked to budget planning.

To inform this inquiry, we sought evidence using a range of approaches. We received 38 submissions to our call for views and, as well as taking oral evidence, we also held informal engagement events with senior Scottish Government officials, and with stakeholders in Dundee and in Glasgow. A summary of this informal evidence, along with the written and oral evidence, is available on the Committee's inquiry webpage. We thank all those who have taken the time to speak with, and provide evidence to us, which has been invaluable in informing our views as set out in this report.

The history of the NPF

As we heard the NPF has evolved since 2007. A refresh by the Scottish Government in 2011 mainly saw changes to expand the National Indicator set and the addition of a new National Outcome on older people. The Strategic Objectives, Purpose, Purpose Targets and the remaining outcomes were retained.1

In its first statutory review in 2018 the Scottish Government changed the structure of NPF (summarised in Figure 1) including:

the removal of all time-limited Purpose Targets because the NPF “is about continuous improvement”;

a more simplified structure with the removal of Strategic Objectives and a revised Purpose, 11 National Outcomes and 81 National Indicators which feed into the Outcomes;

a simplified NPF website including some narrative about the NPF and the technical notes supporting indicators;

making links between the new National Outcomes and the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).1

The United Nations SDGs (see Figure 2) are ‘global goals’ and targets that are part of an internationally agreed performance framework. All countries are aiming to achieve these goals by 2030. The Scottish Government considers the NPF is Scotland’s way to localise the SDGs given they share the same aims.3

Figure 1 - The purpose, values and national outcomes of the National Performance Framework.  The Scottish Government

The Scottish GovernmentFigure 2 - The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals  The United Nations

The United Nations

Currently the NPF aims to—

create a more successful country

give opportunities to all people living in Scotland

increase the wellbeing of people living in Scotland

create sustainable and inclusive growth

reduce inequalities and give equal importance to economic, environmental and social progress.4

Many we heard from considered it helpful to have a statement setting out the shared national priorities and, as Public Health Scotland described, "a clear expression of what wellbeing means for the people of Scotland." 5 It was described as "a common language" which Scottish Government officials explained "unites the civil service".6 A few considered that their organisation would deliver in the areas covered by the National Outcomes whether there was a NPF or not. Some, however, considered that this missed the purpose of the NPF in supporting people to work together across different organisations and sectors (as compared within individual organisations) to deliver a common ambition. 78

It is clear to us that the NPF remains an important agreed vision of the type of place Scotland should aspire to be. As we show in this report, the NPF now needs to make more sustained progress towards achieving that vision and to ensure its ambitions are translated into action.

Our report sets out the challenges that we consider need to be addressed, including through the forthcoming review of the National Outcomes, if greater progress is to be made towards realising that vision. We welcome the Deputy First Minister's confirmation that the public engagement on the forthcoming review will go further than just considering the National Outcomes, by considering how the NPF can achieve greater impact.9

The NPF in practice

In order to understand the key issues to making the NPF work our inquiry sought to understand how the NPF is currently used and the extent to which it is embedded into policy making, decision taking and delivery across Scotland. The evidence we received overall is that it is a mixed picture, for a number of reasons. The NPF is fully embedded in some organisations, sectors and Scottish Government Directorates, with organisations such as COSLA, Nature Scot and Scottish Enterprise all noting that the National Outcomes have a significant influence on the way in which they work. As Carnegie UK explained, however, there are—

many places where other statutory duties or non-legislative frameworks are seen to take precedence. It is simply not clear to many within and outside Scottish Government that the National Outcomes sit atop, or guide, the myriad of policy frameworks currently in use.1

Dr French and others including Carnegie UK agreed with the Auditor General for Scotland's comments that "there is a major implementation gap between policy ambitions and delivery on the ground." This is echoed in work by the Scottish Leaders Forum (SLF)i which reported that "typically, the NPF is not actively used to shape scrutiny, provide sponsorship, undertake commissioning of work or shape the allocation of funding."2

There were several reasons given for this implementation gap. Dr Elliott explained to us that in 2007 the NPF was used as a tool for the Scottish Government to focus on outcomes. It had been accompanied by significant investment in leadership development which had helped to instil a commitment to a more strategic approach to government across Directorates. Dr Elliott suggested that, based on his research so far, the 2018 change to a "whole of society" approach of the NPF had meant that some of the Scottish Government strategic 'mindset' had been lost and that—

a focus on things such as how many police officers are on the ground is slowly creeping back as opposed to thinking more strategically about the outcomes that we are trying to deliver.

Finance and Public Administration Committee 17 May 2022 [Draft], Dr Ian Elliott (Northumbria University and Honorary Chair, UK Joint University Council), contrib. 2, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=13754&c=2402628

Whilst the move to a whole of society approach had "galvanised some external interest", Dr French considered the lack of a proper implementation strategy in Scotland as a key reason for the implementation gap - with the emphasis more on measurement than on how the outcomes of that measurement then informs delivery. He contrasted the Scottish Government's approach of appointing senior officials as "champions" with the approaches in Northern Ireland and Wales that he considered had been more effective in implementing their wellbeing frameworks. In Northern Ireland, civil servants were appointed as accountable owners for achieving outcomes albeit this 'hard' approach focussed on compliance rather than behavioural change. In Wales, the Office of the Future Generations Commissioner had mutually reinforcing 'hard' statutory duties (such as statutory review powers) alongside 'softer' supportive approaches including encouragement and alliance building.4

The complexity of the Scottish public landscape for such a small country was highlighted as an issue and that this "cluttered landscape" may be hampering delivery of the NPF. It was questioned whether the NPF needs to be more dynamic and responsive to the multiplicity of plans, strategies and policies. 5 Fife Council also highlighted that the Scottish Government may not be as joined up as it might be when comes to looking at issues and highlighted the overly complex local and national landscape.6

The Scottish Government's recent National Strategy for Economic Transformation (NSET) was highlighted a number of times as one example of the lack of connection between the NPF and other strategies. As SCVO (and others) explained, NSET "had no mention of national outcomes and maybe a throwaway line on the NPF."7 As a consequence Scotland CAN B observe that, in relation to their work supporting businesses to evidence their contribution to the NPF—

when we have a system that does not reflect the importance of the NPF, that does not make it visible, ....it is hard to reinforce that we want everyone to get behind it.6

Responding to these concerns the Deputy First Minister and Cabinet Secretary for Covid Recovery (hereafter referred to as the DFM) explained that NSET sets out an approach to economic development that is "inextricably linked to Covid recovery, the eradication of child poverty and the achievement of net zero, all of which are embedded in the national performance framework." He argued that the thinking in the NSET is non-compartmentalised, collaborative and about engaging sectors of society rather than the degree to which the structure of a strategy document is aligned with the NPF. 9

That said the DFM acknowledged the wider concerns about decluttering the public sector landscape—

As time goes on, new policy initiatives are introduced and there are moments when we have to take stock and simplify some of those exercises. We will look to do that as part of the work on the national performance framework so that it becomes ever more meaningful to people and organisations. 9

We also found a diversity of approaches in how the NPF is used by participants at our engagement events - some saw the NPF as an 'umbrella' for strategic plans and performance management. For others, however, it tended to be used implicitly to inform their work with one participant noting that "its not an obvious, immediate thing we think about when we make decisions."5 Scottish Government officials also saw it as better used to shape and frame longer-term strategies and specific processes rather than in their day to day work.12 For the Open University it was the SDGs that were used in mapping its activities for recent election manifesto work.6

Dr Elliott highlighted that in Scotland alignment with the National Outcomes is done after the fact - that is once policy outcomes have already been decided. 12 This was borne out by other evidence. For example, Fife Council explained its Local Outcome Improvement Plan (LOIP) was based on evidence in Fife rather than the NPF but was then "mapped against it" to check if anything was missed. SCVO echoed this for its sector, suggesting that—

Success for the national performance framework would be for it to be a framework that drives the work that is done in Scotland, whether in the voluntary sector, the public sector or the private sector.6

Dr Elliott cautioned against focussing on changing the outcomes or indicators of the NPF without addressing the implementation gap and giving more consideration to how to make the NPF work—

It was intended not as a performance measurement framework for counting specific indicators but more as a decision-making tool to get people thinking more strategically and collaboratively, across different directorates within the Government, and beyond it.16

In order for the NPF and outcomes to become more relevant locally, Dr French considered that a process of localisation was needed—

Of taking stock of indicators and outcomes and coming up with a valid and stretching interpretation of what that means in a local context.16

A number supported the provision of guidance, support and shortcuts from a position of expertise to enable organisations to adopt and implement the NPF much better than they currently do.16 As Carnegie UK highlighted, in other countries "scaffolding" has been put in place to support an approach to outcomes, collaboration and joined up working - an approach which is missing in Scotland—

There is no shared understanding or agreement on the process underneath that [the outcomes] for translating that set of ambitions into something that an organisation can do nor are the types of things that would enable people to assess whether it is important for their organisation.16

Without this, those at our Glasgow event noted that it's difficult for people to "see what role they can play" and how it relates to local matters. It was felt that the outcomes are only more meaningful if people understand them. It was suggested that the NPF should set out what people should expect to see in their day to day lives if the NPF outcomes are to be delivered, "people should be able to see themselves in the NPF".7

There was support from Revenue Scotland and others for building into organisational reporting "a statement about what we are committing to and how that ties in with the national performance framework."6

As we heard from Children in Scotland, this approach needs to extend across all guidance and strategies though. They noted that even though statutory Children's services plans from local authorities make an explicit connection with the NPF, the guidance for those plans "then talks about the getting it right for every child". As such whilst there are mechanisms for making the link, "it is just about tightening up and making things more explicit in reporting."6

One of the most frequently cited examples of a good practice approach to translating the National Outcomes into delivery was the concept of the 'golden thread'. As North Ayrshire Council explained—

The National Outcomes influence the development of our Council Plan which outlines our priorities agreed with our communities and is North Ayrshire Council’s central plan. It forms part of the ‘Golden Thread’ linking national outcomes through to each employee’s daily activities.23

Aberdeenshire and East Renfrewshire Councils each also highlighted how the NPF forms part of a 'golden thread' linking national outcomes through to each employee's daily activities. At Highland Council however, the NPF shapes "the organisation where there is alignment with the role of local government or community planning" whilst at Stirling Council the National Outcomes were in its LOIP although "we do not currently refer to the NPF in reference to decision making".24

COSLA are co-signatories to the NPF and considered that whilst the LOIP has to be driven by local need it should not be wildly unrelated to the NPF.6 They explained that depending upon local need, Local Authorities might make much greater progress in delivering on some outcomes than others which are not a priority locally.

In order to achieve the 'golden thread' from national level to local level given the high level and general nature of the national outcomes, Children in Scotland suggested that "the development of a set of sub outcomes beneath the national outcomes might help translate them into action that is more usable at a local level."6

The DFM considered that, although the NPF is highly regarded, "we must grapple with the complex question of how to translate the ambition that it sets out into concrete actions for improvement." He regarded it as clear that the NPF is owned by the whole of society but driven by the Government using encouragement and engagement with organisations to get them to acknowledge the significance of the NPF.9

The DFM was confident that solutions to the implementation gap could be found by drawing upon the experience of those who use the national outcomes to shape policy making and service delivery. He supported the approach of the golden thread as capturing the sense of importance of the NPF but also how budgeting should be aligned - from the contribution of the individual right through the outcomes in the NPF. In that regard he explained that the NPF ethos "should be known about not just by those that deliver public services but those who are engaged in trying to achieve any of the outcomes".9 He recognised that "There might be an argument for some of the description and presentation of that to be more explicit."9

The DFM welcomed the Committee's inquiry as providing evidence in "highlighting areas we can improve". He confirmed that the public engagement as part of the next review of the NPF outcomes will start later in the year and will go further by considering how the NPF can achieve greater impact.3

One of the fundamental issues raised in evidence was whether the NPF solely provides an overarching vision everyone can support or if it should also be used to deliver that vision. Based on the evidence we received, we consider that the NPF should both provide the vision and be used to shape delivery decisions. We also consider there is still some way to go before the NPF is embedded in the work of all relevant Scottish organisations.

We agree with the DFM that there will be no single solution to addressing the implementation gap. This report therefore sets out a range of approaches we consider will support greater progress in addressing it.

We agree with the evidence we received that there should be a 'golden thread' from the NPF through all other frameworks, strategies, and plans to delivery on the ground. We consider that the current approach whereby the NPF is sometimes seen as "implicit" in policy development and delivery does not reflect the status or importance the Scottish Government, COSLA and others consider it should have.

We therefore recommend that, as part of the next iteration of the NPF, the Scottish Government, as the "driver" of the NPF, should set out clearly and explicitly how the NPF will be used by it in national policy making. The Scottish Government and COSLA should also collaborate with others across Scottish society to propose how it can be used by others to drive their policy development and delivery.

We also recommend that all government (national and local) policies, strategies and legislation explicitly set out how each will deliver on specific NPF outcomes, their expected/intended impact on NPF outcomes and approaches to monitoring and evaluation.

We recognise that such statements in of themselves won't deliver progress towards delivering the National Outcomes. It will, however, provide greater visibility of the NPF as the golden thread connecting national policy making through to delivery. It will also support greater transparency and scrutiny of how the work of organisations actively contributes towards the National Outcomes. It should help to make use of the NPF a normal part of the policy process.

We also recommend that the approach of a golden thread is shared widely across the public sector by the Scottish Government and COSLA as an example of best practice of incorporating the NPF from national level to local level. That said, we heard concerns about how best practice is shared and we comment on this later in this report.

We welcome the DFM's commitment to take stock and simplify policy initiatives as part of the review and request confirmation of when this exercise will be concluded. We also look forward to considering the outcome of this exercise from the DFM in due course.

Throughout this report we highlight a number of areas where progress has been 'mixed' or 'patchy.' A more systematic approach to implementation of the next iteration of the NPF is needed and we therefore recommend that the Scottish Government as part of the forthcoming review should also consult on an implementation plan, to sit alongside the final NPF, which sets out how organisations will be supported to embed the revised NPF and adopt its approach.

Wellbeing and Sustainable Development

A number of those we heard from highlighted the opportunity to make greater progress with delivering on the National Outcomes through the Scottish Government's proposals for a Wellbeing and Sustainable Development Bill. Oxfam Scotland highlighted the SNP's manifesto commitment that the Bill will make it a statutory requirement for all public bodies and local authorities in Scotland to consider the long term consequences of their policy decisions on the wellbeing of the people they serve and take full account of the short and long term sustainable development impact of their decisions.1

Oxfam Scotland considered that such an approach could narrow the distance between the ambitions of the National Outcomes and their delivery 1 whilst SCVO support the calls for a Bill and a future generations Commissioner who could look at best practice from elsewhere. They consider the NPF needs more resources and bite.3

Dr Elliott cautioned against using legislation to force public bodies to plan for, promote, set or account for objectives given they can choose to do so in "a passive and superficial way, if so inclined." Instead, they could be encouraged through supportive challenge from a Commissioner, auditor or inspection body and to see value in fulfilling a duty as a means of promoting their own objectives. 4 Dr French concluded from his comparative analysis of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland that a combination of soft and hard power approaches (as set out earlier) maximises implementation outcomes.5

Oxfam Scotland hopes that the Committee's work, the NPF review, the Wellbeing and Sustainable Development Bill and the commitment to a future generations Commissioner can be viewed as a continuum, rather than as four separate pieces of work.3

In its Programme for Government for 2021/22 the Scottish Government confirmed that it would further develop the use of the NPF through the upcoming review of National Outcomes and through consultation on a Wellbeing and Sustainable Development Bill. 7 More recently the Scottish Government confirmed (in its Programme for Government for 2022/23) that it—

will explore how to ensure the interests of future generations are taken into account in decisions made today. This may include placing duties on public bodies and local government to take account of the impact of their decisions on wellbeing and sustainable development, and the creation of a Future Generations’ Commissioner.8

We seek clarification from the Scottish Government as to how its review of the NPF will take account of and impact on its proposals for a Wellbeing and Sustainable Development Bill and for a Future Generations' Commissioner. We also seek confirmation of the extent to which the consultation which will form part of the NPF review, will include consideration of potential 'hard' statutory approaches alongside 'softer' powers as described to us.

Sharing best practice

A clear message from across our engagement events and evidence was that there needs to be greater learning from, and sharing of, best practice in delivering on the NPF. As one private sector participant at our Dundee event explained "Success is like trade secrets - it isn't shared, so we don't know if we are doing well or otherwise."1 We heard of many good practice examples of work being undertaken but which are not recorded, reported on or shared more widely.

COSLA agreed that "the space for sharing and learning from best practice and evaluating interventions is perhaps missing and could be improved on." It noted that, while identification of best practice does happen in local authorities, it is shared more informally through officer networks, for example.2

At our Glasgow event there was support for the Scottish Government to have a greater role in providing more data and relevant research, case-studies or examples of best practice including publishing these on the NPF website (formerly known as Scotland Performs). This was considered particularly valuable for those organisations that do not have the resources to commission research or explore different approaches.3 Dr French suggested that creating "cross boundary learning forums and national events to bring together good practice and share learning" was a 'soft power' strategy that could be adopted to influence and persuade others to act.4

The SLF also considered that attempts should be made to capture the contributions that are already being made by organisations which probably don't know about the National Outcomes and "do not understand that the thing they are doing is making that contribution."5

Building on their work into accountability and leadership of the NPF, the SLF plan to continue its work by identifying and documenting specific good practice examples which it hopes will further inspire leaders to take action.5

The DFM explained that "every effort is made to ensure that best practice is shared across the community of governance in Scotland". He highlighted the work of the Improvement Service and the Government's activities through Social Investment Partnerships. The challenge is "to ensure that there is an appropriate platform to enable that to be undertaken" and he expressed frustration that good and innovative elements of practice taken forward in some parts of the country take longer to reach the rest of Scotland.7

We heard of many good examples of organisations, projects and services that are making an effective contribution towards delivering the NPF. Although some good practice has been published by the Scottish Government, it is disappointing to hear that learning from, and sharing of, these examples can be reliant upon word of mouth and informal networks.

We recommend that the forthcoming review considers how good practice examples and learning can be shared more consistently and publicly across national and local government, voluntary sector, public and private organisations. This should include the potential to develop the current NPF website. This approach is particularly important for those organisations who do not have the resources to undertake their own research into what works well.

Collaboration

The NPF sets out that, in order to achieve the national outcomes, it aims to get everyone in Scotland to work together.1 As the DFM explained the NPF is all about "encouraging partnership, collaboration and recognising the part that we all play in improving the wellbeing of people in Scotland." 2 This was echoed by Revenue Scotland who explained that the NPF could not be delivered without collaboration and that “ultimately to deliver priorities you need commitment and people to work together to deliver them.”3

In 2011 the Christie Commission reported its views on the future delivery of public services in Scotland. This Commission was established by the then First Minister and it reported that a key objective of reform should be to ensure that public service organisations work together effectively to achieve outcomes. As the report warns, unless Scotland embraces a radical, new, collaborative culture throughout its public services, both budgets and provision will buckle under the strain. More recently it has been reported that the COVID pandemic supported 'honest collaboration' arising from fewer priorities which had enabled greater alignment between partners.4

We received a number of examples of good collaboration in evidence. Bòrd na Gàidhlig highlighted its work with the Faster Rate of Progress initiative which brought together a range of public authorities to support the Gaelic language.5 Volunteer Scotland highlighted its Communities National Outcome. A Connected Scotland, the 2018 strategy for tackling social isolation and loneliness, which was co-produced by a wide-ranging group of partners.6

COSLA cited a number of examples including its work on Adult Social Care and Mental Health, explaining that it works collaboratively with the panoply of public sector organisations in Scotland, the UK and internationally in pursuit of the development of public policy which will secure progress toward the National Outcomes.7

Participants at our Dundee and Glasgow events, however, had mixed views as to whether the NPF encouraged collaboration. Some considered that the NPF “gives us a reason to be in the same room and can foster an understanding of what other organisations are collectively trying to achieve.” Others felt that the NPF does nothing to support different organisations to work together, which may not be helped by some of the national indicators in the NPF 'working against each other'.8 We heard that collaboration can work better when all the bodies concentrate on what they have in common and when there is a short-term goal, albeit there remain barriers to sharing data to support collaboration because of GDPR compliance.98 The SLF explained that current approaches to accountability place more emphasis on the accountability of lead individuals for the performance of their organisation rather than their contribution to cross-organisational working.11

The DFM was clear that the principal areas of the Government’s policy agenda – economic recovery from Covid, the eradication of child poverty and addressing commitments on net zero - won't be achieved without collaboration, given they cut across the National Outcomes. He also recognised, however, the ongoing challenge for Government in working beyond compartments—

we must encourage a collaborative, non-compartmentalised approach to policy making to ensure that we achieve the Government's policy objectives in a fashion that achieves the aspirations of the national performance framework.12

He added that it is also an ongoing challenge in Government to move from transactional interactions with third sector organisations to a more holistic approach. He highlighted that the Cabinet and Ministers are also looking very extensively at the delivery of priorities but that Government probably needs to look at whether the NPF is as influential in decision making as it could and should be. The formulation of the child poverty delivery plan was cited by both Scottish Government officials and the DFM as a good example of cross-governmental collaboration which has resulted in a much broader and more relevant intervention.12

One of the key aims of the NPF is to encourage everyone in Scotland to work together to deliver its vision and as we heard this shared vision provides, for some, the impetus for collaboration to happen. However, as with other aspects of the NPF, the evidence we received is that progress is 'patchy'.

We heard many good examples of collaboration, and capturing these as good practice examples as we recommend above, should support greater progress. We note the evidence that the COVID pandemic has led to better collaborative working in some areas and seek confirmation from the Scottish Government and COSLA that they will seek to capture and share those lessons.

Accountability

The SLF in its Report into Leadership, Collective Responsibility and Delivering the National Outcomes found that "the current status of accountability against the NPF is ‘patchy’.... Put simply, if organisations are not being asked to consistently account for their role in achieving the national outcomes, it is unsurprising that the NPF is not a significant feature in how most organisations plan and deliver their work."1

As Public Health Scotland explained, if the NPF is to be taken to the next level, it needs to have "more teeth" with regard to accountability and suggested a multifaceted approach of "leadership, scrutiny and accountability" to support progress.2

The evidence we heard is that there are a variety of experiences in relation to accountability for performance against the National Outcomes. At our event in Dundee some considered that where the NPF is built into organisational strategic planning, accountability for its delivery is implicit, but otherwise it was less clear whether accountability was directly focussed on the NPF.3 For Public Health Scotland accountability was strongest at Board level given its focus on the strategic plan which has the strongest explicit link to the NPF.4 Scottish Government officials considered there was less clarity as to how the NPF is used by the Parliament and the outside world for scrutiny.5

The SLF explain that, alongside meeting the needs of its service user, good accountability systems should also—

Have an improvement focus; support learning and continuous improvement....that future delivery can be enhanced. This improvement focus is the key incentive for organisations to engagement willingly in the accountability process...1

Oxfam Scotland considered that with the removal in 2018 of all of the time-limited purpose targets in the NPF it is quite challenging to build accountability for what progress is to be achieved and by when. They suggested some time limits would help with scrutiny of the policies and spending choices and testing the assumptions of the Scottish Government and local authorities.2

Carnegie UK highlighted how the Welsh model had delivered greater accountability where the Wellbeing Commissioner and Audit Wales agreed to collaborate to make best use of each set of statutory powers. This is not only in relation to reporting and research but also in the ability to request information to publicly hold to account Welsh public services and bodies for delivering their national outcomes. This also extends to having processes in place to show how public bodies are trying to have regard to the national outcomes and goals in the work that they do. Carnegie UK contend that this is the key accountability route Scotland is missing.8

We heard suggestions that the current "all of society" approach to the NPF limits accountability as it is impossible to hold everyone to account for everything. Some suggested a more prescriptive approach to assigning outcomes to organisations would be preferable, for example by requiring specific agencies to have regard to specific outcomes and then nominate to whom they are accountable (such as the Parliament, specific Committees, a commissioner or Audit Scotland). Carnegie UK explained that, in the absence of this, the current requirement in the Act that organisations must "have regard to" the National Outcomes gives the perception that this is "voluntary" even though it isn't.8

Others however, such as COSLA, argued that "having regard to" has a legal standing that is not insignificant. They suggest that there is a risk that if the term was strengthened, everything then becomes a priority, whereas the "have regard to" duty provides necessary flexibility to consider prioritisation within the NPF and the outcomes that need to be focused on locally. It also provides an opportunity to focus delivery on really urgent aspects when that is necessary.2

Carnegie UK also considered the approach of prescribing accountability for certain outcomes to certain organisations problematic as it isn't always possible for changes in performance to be solely and directly attributed to a specific action that was carried out. They explained that, instead, what "we can say is that we are making a contribution to that outcome."8 In that regard incentivising good behaviours would be more productive than mandating behaviours.12 As the SLF set out—

Reinforcing and rewarding those organisations who have set out how they deliver against the NPF, making it easier to be held to account for that delivery, will play significantly into incentivising and motivating leaders involved in delivery to engage willing in the accountability process.1

The DFM is not persuaded by a more prescriptive approach from Government and is, instead, interested in making sure people are empowered at a local level to define the solutions that work for them, provided they contribute towards the National Outcomes. The Scottish Government approach has been one of "encouragement and engagement with organisations" to ensure they acknowledge the significance of the NPF.14

Given the removal of timebound targets from the NPF in 2011, the DFM was asked whether introducing milestones might be a more effective way of assessing progress toward the National Outcomes. He responded that it is a mixed picture with some statutory targets in some areas such as child poverty and net zero inevitably requiring a "degree of intensity that is commensurate with those targets". As such, the NPF should enable the Government to compare progress from one year to the next and judge whether it is satisfactory.15

As the Scottish Government acknowledges, its approach has been "more carrot than stick" when it comes to the use of the NPF to influence policy making and delivery. Based on the evidence we received, we consider that there needs to be a better balance between these two with more consistent use of accountability mechanisms. We explore what this means in terms of scrutiny and leadership later in this section.

We are persuaded by the evidence we received that, at this time, the need for local flexibility to respond to local needs outweighs the arguments for strengthening the current requirement that public bodies must "have regard to" the NPF. The counter balance to that is, however, that there needs to be a considerable strengthening of scrutiny over how organisations have had regard to the NPF.

The Welsh approach of using both 'hard' statutory powers alongside 'softer' encouragement, relationship building and sharing good practice has much to commend it. We therefore seek confirmation of the extent to which this approach will be considered as part of the review of National Outcomes and the proposed Wellbeing and Sustainable Development Bill.

We acknowledge that some National Outcomes might be subject to greater focus for action than others as a result of explicit Government priorities such as the economic recovery from COVID. In those circumstances, however, it is unclear how the other National Outcomes can secure greater focus when it is not possible to compare, over time, how any progress made compares with what was expected. We therefore seek confirmation that the consultation which forms part of the next review will explore providing time-bound milestones/objectives to provide a greater focus and assessment of the rate of progress towards achieving National Outcomes.

We note that the SLF is currently working on how and what incentives might encourage people to engage with the NPF and we look forward to the outcome of that work.

Measuring Contribution and Indicators

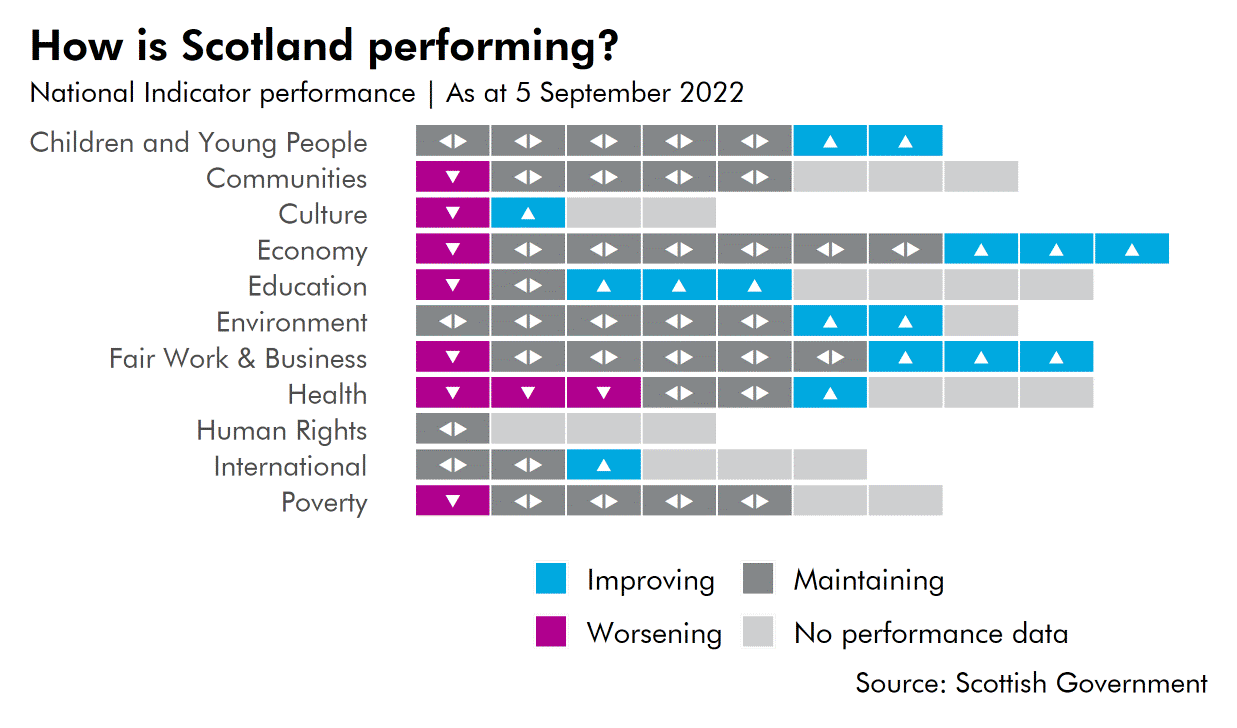

Currently the NPF uses National Indicators to measure progress towards achieving the National Outcomes. There are 81 National Indicators and, as at 11 July 2022, in most cases (36) performance is maintaining, whilst improvement is seen for 14 Indicators, and for 10 Indicators the position is worsening. However there is no data for 21 indicators. The Scottish Household Survey is the source for nine of the “missing” indicators, whilst the Scottish Health Survey is the source for a further four. In six cases no data is available as the indicator is still in development (see Figure 3).1 In our engagement event with Scottish Government officials it was acknowledged that the higher level purpose and outcomes were used more extensively that the specific indicators measures in the NPF (albeit they were considered to have a role in improving transparency).2

Figure 3 - Progress made against the National Performance Framework National Indicators for each of the National Outcomes as at 5 September 2022  SPICe infographic of Scottish Government data

SPICe infographic of Scottish Government data

Measuring progress against the National Outcomes can be challenging especially when it relies on multiple organisations for delivery and across a number of policy areas. As we heard it can be achieved through collaboration - for example SCVO explained it had worked with the Scottish National Investment Bank to agree proxy measures which enable it to demonstrate how investments would impact on National Outcomes.3

There were questions about whether the current approach of National Indicators provided the best measure by which an organisation's progress against the NPF should be assessed. Some suggested that rather than scrutinising the delivery of the National Indicators, organisations should instead be held to account for their contribution to the National Outcomes. Oxfam Scotland explained that there will always be some reticence about accountability for specific outcomes given they require multiple actors to drive progress but that —

there is a difference between that and holding people to account for transparently showing where they are contributing.3

Dr Elliott explained that a similar philosophy exists behind the UNSDGs which are meant to be stretching ambitions with the expectation that people will make progress towards those goals. As such the question is how to measure progress and "thinking about the processes instead of focussing on the granular details that arises from the specific measurement of things."5 There is also a role for parliamentary Committees in considering how they scrutinise the NPF outcomes rather than taking a granular approach to specific indicators. This includes considering whether the indicator acts as an outcome indicator, whether it is a proxy indicator and whether it is a relevant indicator for the current times.5

This approach also reflects emerging academic consensus according to Dr French, whereby attributional accountability is reframed to being about contribution. For example, where Government is held to account for its contribution to a broad range of national outcomes or indicators in a contextually specific way.

He added that in the Welsh example the accountability process begins with the creation of a stretching contribution plan about areas beyond the boundary of each organisation in order to make a broader impact. The Commissioner's oversight function provides the necessary information to enable a valid assessment of who has stretched themselves and who has not.5

This approach of holding organisations to account for their contribution towards National Outcomes rather than solely on their delivery of National Indicators was supported in other evidence we heard. Carnegie UK described it as—

We are trying to find a way to hold people accountable for the bit that they can be responsible for, which is how they explain how they are changing their behaviours in light of the information that comes through the national outcomes and national indicators, so that we can see the golden thread.5

COSLA highlighted the difficulties for local authorities in demonstrating their contribution to National Outcomes. This was in part because the underlying indicators sit at national level or break down in ways that are challenging for local authorities to reflect their exact contribution to. They explained that, as a result, local authorities link to the NPF through their LOIP although the timing of refreshing the LOIP and the NPF didn't necessarily coincide —

Although there is frequently a clear link between those things, the submissions show that that link is not always explicit.3

The challenge of measuring progress is recognised by the Scottish Government - in a December 2021 blog on "improving how we predict and measure our impact", Scottish Government officials noted that in relation to some sectors—

All public authorities in Scotland need to demonstrate their alignment to, and impact on, the NPF. And we would like the third and private sectors to do that too. Yet we currently have no way to collect, measure, analyse, report and communicate the impact of multi-sector activities on the National Outcomes. We also have no way to enable different sectors (charities or businesses, for example) to evidence their contribution to achieving the National Outcomes.10

As such it was proposed that streamlining and standardising a way to collect, measure, analyse, report and communicate the impact of multi-sector activities will be game-changing and suggested that technology would assist.

We also heard requests for simplification of reporting with some highlighting the challenges of multiple reporting deadlines for projects or the resources used to provide reports that are then never asked about.3The Open University and others recognised and supported the importance of being accountable through reporting, but suggested that a more proportionate way may be for a single approach (with all the required information). Children in Scotland supported this suggesting that "if we focus outcomes around a national set of outcomes that might help streamline reporting approaches so we do not have to report in different ways to different funders."3

The DFM highlighted the role of the Accounts Commission in scrutinising individual local authorities. He also explained that the Scottish Government's performance approach puts challenging demands on organisations in relation to what is expected of them—

We have to satisfy ourselves that organisations are operating with good will in a direction that will help us to achieve the national outcomes.13

We acknowledge the difference between tracking progress towards delivery of the National Outcomes (through indicators) and organisations being held to account for their contribution towards making such progress. As we heard many feel they are scrutinised on their performance against the former, when it should be the latter, particularly given the collaborative approaches needed for some National Outcomes to be realised.

We recommend that the next NPF review should consider the extent to which the Scottish Government, local government and others should be more systematically and consistently held to account for their contribution towards the National Outcomes. As we have recommended earlier in this report, consideration should be given about whether organisations should have to be more explicit as to how their activities contribute to the NPF so as to support scrutiny.

We also seek an update from the Scottish Government on what progress it has made in "streamlining and standardising a way to collect, measure, analyse, report and communicate the impact of multi-sector activities" since this issue was highlighted in 2021.

We are very concerned that a number of National Indicators still have no data, almost five years after the last review. This hampers the ability to fully track and scrutinise progress in those areas. We therefore recommend that the next iteration of the NPF includes a set of indicators which have been agreed, between Scottish Government, local government and relevant sector representatives, to best track progress in delivering the outcomes. We consider that these should not be left for development.

As part of that work, we recommend that the Scottish Government should work with Local Government and others, as appropriate, to better harmonise the National Indicators with various existing measurement frameworks in the public sector to simplify the reporting requirement for organisations.

Scrutiny Bodies

The SLF described the potential for a "virtuous circle" of scrutiny to be created, whereby boards, internal audit, external audit, funders, council Committees and Parliamentary Committees are scrutinising organisations which are then making changes as they go. All of which then leads to greater progress in implementing the NPF. As the SLF contends—

It should not be the case that the corporate plan and Parliament are the two ends of the chain with nothing in between.1

As we heard, the introduction of the NPF has heightened the importance of external scrutiny taking a longer term outcomes based approach to work, considering how different bodies and agencies work together to address complex cross-cutting issues such as the drive towards prevention, addressing inequalities, supporting sustainable and inclusive growth and improving wellbeing.2

Carnegie UK suggested that Audit and scrutiny bodies have been slow to incorporate the National Outcomes into their work, though Audit Scotland has been making progress in this field more recently.3 The SLF explained that creating an alignment between audit and inspection approaches and the NPF has proved challenging—

as scrutiny bodies have sought to implement these new models of scrutiny alongside their existing statutory commitments and because the NPF is not used to drive or frame the introduction of new scrutiny regimes.2

This was borne out in the evidence we received. Whilst Councils may be audited indirectly against the NPF, COSLA agreed with Fife Council that there are inspection and regulatory regimes that are not aligned to the NPF but which "might look at other explicit performance measures. As we all know, that drives behaviour."5

COSLA considered that "there is a good opportunity over the longer term if we can better align all regulatory inspection and audit regimes to focus thinking on an outcomes approach."5 Fife Council added that it has as much to do with the capabilities of the people who work in organisations (such as skills to analyse data and the evidence of what is making a difference) as with how the performance regimes are set up.5

There were also mixed views as to the extent to which national and local government and the Scottish Parliament had risen to the challenge of effectively scrutinising progress towards the NPF outcomes. The SLF reported that whilst there had been some notable successes in scrutiny of the NPF at parliamentary level, the NPF is not routinely embedded in political scrutiny such as the work of parliamentary Committees, or councils' equivalents. As a result the NPF gets—

less focus in the short-term than monitoring and reporting on service-specific factors.

This was echoed by others who observed that they are not subject to specific questioning about how they contribute to the National Outcomes when appearing before Parliamentary Committees although, as Registers of Scotland explained, they may get questions related to aspects of the National Outcomes.8 Fife Council highlighted that the emphasis seems to be on reassuring rather than challenging, such that when reports are taken to Committees—

we are throwing lots of numbers at you and showing how we are measuring things and if the numbers are going down, there may be a good reason for that. However, who is asking difficult questions about whether we are making a difference and making things better.5

In contrast, Dr French highlighted that the Scottish approach to the NPF (compared with Welsh and Northern Ireland wellbeing frameworks) shows that Scotland has the most significant usage of National Indicators in parliamentary scrutiny. He added that the NPF has benefited from a degree of "solidity" and recognition compared with the national outcomes and indicators in Northern Ireland and in Wales where it is the Act that is more often referred to.10

The SLF also saw a role for organisations such as the Public Bodies Unit at the Scottish Government, given their role in providing support with inducting board members, in ensuring that the NPF and the National Outcomes are used by boards.1

The Welsh approach of collaboration between the Welsh Futures Generation Commissioner with Audit Wales was once again highlighted as a good example of where making the best use of statutory powers has been influential in shifting practice. Carnegie UK considered a Scottish Wellbeing and Future Generations Commissioner as one mechanism to better incorporate the National Outcomes into the work of Audit and scrutiny bodies.3

The DFM highlighted the roles of Audit Scotland and parliamentary Committees in scrutinising Ministers as well as Ministers themselves examining whether proposed policies are consistent with the NPF.13 Whilst the Scottish Government has no scrutiny role in relation to the performance of local government, the DFM recognised that the Accounts Commission does. As such when it looks at individual councils—

I would be surprised if I did not see some commentary on the degree to which the local authority's planning and thinking were aligned to the National Performance Framework.14

We recognise that boards, internal audit, external audit, funders, council Committees and Parliamentary Committees all have a role to play in effectively scrutinising the progress being made towards achieving the National Outcomes, as well as the contribution of organisations to that progress, if the "virtuous circle of scrutiny" is to be achieved.

Our view is that there needs to be a refocussing of scrutiny onto the NPF and as we have stated in previous reports "a repositioning of the NPF at the heart of Government." To better deliver on the virtuous circle of scrutiny we recognise the Finance and Public Administration Committee has a lead role in enhancing NPF scrutiny work across Parliamentary Committees. We also recommend that:

Supported and facilitated by the Finance and Public Administration Committee, the Conveners Group at the Scottish Parliament also considers how Committees can further embed scrutiny of the NPF in Committee work. More generally we consider that Parliamentary Committees should be more explicit about how their work impacts on specific National Outcomes;

The Scottish Government, along with local government and scrutiny bodies, consider the extent to which scrutiny, audit and regulatory regimes are aligned with the NPF;

The Scottish Government's Public Bodies Unit reviews the extent to which its work with new and existing board members supports Board members to deliver effective scrutiny of the NPF.

Our other recommendations in this report, such as more explicit statements of the contributions organisations make towards progressing the National Outcomes, should also support Parliamentary Committees and others to provide greater scrutiny.

Leadership

In order to make greater progress towards achieving the National Outcomes we heard that, alongside scrutiny and accountability, leadership has a key role. As the SLF set out in their report—

Crucially if enough leaders make some small changes then this change in collective approach can start to change the accountability system they all work within. We therefore conclude that starting with asking individual leaders to consider what action they can take, within the role they hold, will be the most expedient way of making rapid improvement. 1

However what they found was that "leaders across the public services have told us that they feel held to account for many different, potentially competing demands."1 Scottish Government officials also considered that leaders across the public sector are not really held accountable for delivery of the NPF.3

The SLF also reported that, despite no consistent approach to holding organisations to account for their delivery of National Outcomes, many organisational leaders do seek to show how they are contributing as "its the right thing to do" even if they are not asked about it.4

The Auditor General for Scotland highlighted that without encouragement and measurement of shared accountability alongside leaders being held to account for their organisational objectives—

there remains a risk that leaders will prioritise their individual organisation’s performance within their organisational boundaries over any shared objectives.5

Responding to the question on whether leaders feel accountable for delivering change, the DFM recognised the work of the SLF which is made up of public sector and other leaders. Given this, he did not consider that "there is an absence of engagement and accountability on such questions."6

In relation to how to increase the pace and intensity of progress towards the National Outcomes, the DFM acknowledged that it—

is about the political leadership that we put in place to move the organisations. We might need to think of the different policy solutions that will enable that to be the case and give particular areas of policy greater priority than others.6

We agree that effective leadership, allied with a focus on challenging leaders on how they are contributing to the National Outcomes, are key mechanisms to drive progress in delivering the National Outcomes. For us this starts at the top with Scottish Government Ministers, Council Leaders and COSLA leading by example in holding their colleagues, senior officials and other leaders to account for their contribution to the NPF. As the driver of the NPF, we therefore seek confirmation of how Scottish Ministers ensure that their officials and public bodies are held accountable for the NPF outcomes along with examples of where this has been done successfully.

The Scottish Leaders Forum report also makes a number of other recommendations on how leadership can be strengthened "starting with asking individual leaders to consider what action they can take, within the role they hold" which will, they explain, be the most expedient way of making rapid improvement. We commend this report to the Scottish Government and request confirmation of how it will be used to inform the work of the next review of the National Outcomes.

Money matters

A theme running through the Committee's pre-budget and budget scrutiny 2022-23 was the extent to which the National Outcomes in the NPF influence policy-making and spending decisions. Indeed, in both reports, we recommended that "the Scottish Government considers how the National Performance Framework could be more closely linked to budget planning". We reiterated this recommendation again in our Report on Investing in Scotland's Future: Resource Spending Review Framework, and expressed our disappointment that the Scottish Government did not respond to this recommendation in previous reports.

That this response is outstanding is perhaps unsurprising given the evidence we received that the National Outcomes do not play a significant role in decisions on spending priorities or in providing funding. It also appears that funding or grants provided were also not contingent on delivery of the National Outcomes with some at our Glasgow event highlighting that there is "no obvious link" between the NPF and funding allocations made to the third sector and public bodies.1

Local authorities are responsible for a large proportion of the National Outcomes but consider they do not receive proportional funding to support that work. COSLA highlighted the tension between local authorities using their limited funding on local priorities (for example identified through LOIPs) and "funding which is provided only for those centrally favoured solutions and is often short term in nature." They consider that there needs to be an acceptance across the Scottish Government that local outcomes, developed in the context of driving toward National Outcomes, are a proper and valid way to achieve National Outcomes.2

In fact we heard that funding decisions are significantly influenced by other drivers. Fife Council explained it does not assess grant awards against their contribution nor map awards to the National Outcomes directly. Instead the focus is on the contribution that is made to the Plan for Fife ambitions and the service plan priorities of the relevant funding service. Stirling Council explained that public funding is "largely not contingent" on demonstrating delivery of the National Outcomes."3 Fife Council and others highlighted the benefits of retaining flexibility in how funding is spent as being important to ensuring that local priorities and needs of areas are delivered upon.4

The Open University explained that rather than the National Outcomes, its outcome agreement with the Scottish Funding Council was its guiding document. SCVO explained that in terms of scrutiny, "we have never been asked how all the grants that we get from various people contribute to national outcomes."4

As the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Network observed—

it naturally follows that it will remain highly likely that other organisations or public bodies will not link spending priorities to the National Outcomes and the SDGs if the Scottish Government themselves do not lead by example.6

The Auditor General for Scotland explained that, whilst the NPF has laudable long-term aims which are widely supported, for example the National Outcome to support people being well educated, skilled and able to contribute to society —

it’s not clear how this outcome, and others like it, link to spending across Scottish budget portfolios and how the Scottish Government and its partners are measuring the success of that budget spending against the aims of the NPF.7

As highlighted by some who attended our Glasgow workshop, money matters as "those who provide the funding drive measuring and reporting."1 The SLF explained that how budget processes work, nationally and locally, can often run counter to taking a well rounded outcomes-based approach.9

The Scottish Budget and the accompanying Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement identify at a portfolio level which National Outcome each portfolio contributes to. Scottish Government officials acknowledged, however, that the NPF is not really used for allocating spending so it not part of the budget decision-making process within Government albeit it may be helpful in prioritisation.10

There was support from a number of organisations, including Children in Scotland, for better linking of funding decisions more specifically to the National Outcomes.4 Citizens Advice Scotland said it would like to see funding models recognise and prioritise outcomes for individuals and communities. This would, they consider, reflect a shift in the funding paradigm away from output and input measures. They highlighted how progress had been made with the COVID recovery and Child Poverty Strategies, along with —

positive discussions about placing outcomes as central to funding agreements but there is more to do to see this replicated across National and Local Government as a whole.4

Dr Elliott cautioned against seeing the forthcoming review as an opportunity to take a more directive (or ringfencing) approach to service delivery given "it has not proved to be particularly successful in delivering outcomes."10

Others observed that currently decisions may be made on where to spend money before the assessment of how that activity may contribute to National Outcomes. Carnegie UK, for example, highlighted analysis undertaken on budgeting for children's wellbeing where policy assessment against the National Outcomes was ad hoc and, rather than assessing how people in Scotland are doing against the National Outcomes and then considering where to spend the money -"It is the other way round."10 They added that the assumptions used to justify spending were also difficult to access from outside government. It was recognised though that such a wellbeing approach to budgeting would turn the whole process on its head and would take a considerable number of years based on the experience in New Zealand.10

Some raised the issue of multiyear funding and how "insecure funding" leads to poorer outcomes.1 As SLF explained, if multiyear funding was provided then it would mean that less time is spent on monitoring and "thinking about things over and over again and preparing for the next year and the year after that." Instead the focus of scrutiny could be on the longer term and, for organisations, on the collective approach to securing funding.17

This year the Scottish Government published multiyear indicative funding through its Resource Spending Review (RSR) - the first RSR since 2011. During its inquiry into the Framework for the RSR, and in previous budget scrutiny, the Committee heard repeatedly that it is difficult to see how the Scottish Budget and the RSR link with the NPF. As Fraser of Allander explained—

where we often have problems and why we cannot make a link between the budget documents and the NPF is that the finance teams that work on the budget are often not given responsibility for ensuring that a budget document links to the NPF...it is for the policymakers in the individual parts of the Government to ensure this is a link, but when the big decisions are being made in the finance teams, that link does not work.18

Collaboration in budgets was also seen as a challenge if agencies work together to deliver improvements and, once delivered, any savings generated do not benefit all of them. The question was asked how organisations, in those circumstances, are incentivised to act when they may not ultimately benefit financially from their investment. Public Health Scotland considered that is why it is important that there is joint accountability on the NPF rather than the present approach whereby each individual organisation is statutorily accountable for delivering what it is directly responsible for.4

There is also a challenge in moving budgets from day to day reactive spending to more proactive spending in areas such as prevention and early intervention which might better support the delivery of NPF outcomes. As Children in Scotland explained this is because some difficult decisions need to be made about prioritisation and until they are made "we are probably just going to keep on going round and round in circles."4

Financial constraints and a lack of sustainable funding were highlighted by some, such as East Renfrewshire Council and Children in Scotland, as a barrier to new ways of working or innovation when resources are needed to deliver on more immediate challenges.3

When asked whether budgetary constraints impact on the delivery of the NPF, Scottish Government officials, however, considered that whilst there was some impact “sometimes more money is not the best thing.” As such, financial constraints can focus and optimise delivery where you can “get more bang for your buck”.10 Fife Council also considered that funding does not necessarily lead to better practice and better outcomes but they advocated less ring fencing of budgets and using an evidence base to inform new approaches and develop best practice.4

Oxfam Scotland noted that there had been some positive developments in that the Scottish Budget now details the “primary” and “secondary” National Outcomes which spending by different government portfolios is designed to support. That said, Oxfam Scotland considered that there could be clearer links established between each National Outcome and the spending decisions put in place to help achieve them whilst recognising that progress will also be driven by a range of non-spending decisions.24

Finally, we heard from Scottish Government officials about the difficulties in framing commercial contracts that reward those who contribute to the NPF. For example, in previous tendering exercises, issues such as health and wellbeing of staff, promotion of tourism had been flagged and addressed by those tendering but had not necessarily been included in the original specification or advert.10

The DFM acknowledged the importance of budgeting aligning with the NPF in seeking to achieve the National Outcomes —

Inevitably, funding and policy decisions at an operational level will have enormous significance for whether those aspirations are achieved.26

He recognised, however, that improvements could be made in areas such as budgeting for outcomes and integrating the NPF into the Government systems and processes. He observed that the challenge arises if there is an emergency or critical intervention required when it is difficult to not fund that whilst at the same time as trying to encourage more preventative spend. Whilst more and more of the Scottish Government's funding decisions are being aligned to preventative interventions, the need to respond to critical interventions remains.26

The DFM was asked if there is a place for the performance of organisations to be assessed on their ability to align funding with delivery on National Outcomes - potentially rewarding those that do or penalising those that don't. He replied that that was not the route the Scottish Government had gone down, instead focussing on encouragement and engagement with organisations. That said, the Scottish Government would give those issues consideration if the Committee "comes to conclusions on some of those questions" as part of its inquiry.26

We acknowledge that linking the Scottish Budget to outcomes is complex and that, given the breadth of the National Outcomes, it could be said that if organisations spend money on improving people's lives then arguably they are implicitly aligning spending with the NPF. The Scottish Government has, however, a budget of over £45 billion and as the "driver" of the NPF should be much more than a facilitator or provider of strategic direction to other public bodies.

It is therefore disappointing to hear that the NPF is not seen as explicitly or transparently driving financial decisions by the Government nor as a mechanism by which organisations are held to account for spending funding effectively.

As we have already recommended the NPF needs to be used more systematically and explicitly to influence decision making if it is to be the golden thread from which all other policies and strategies connect to delivery on the ground. Whilst we do not support greater ringfencing of funding we do consider that there needs to be a closer alignment of those who advise and take funding decisions in the Scottish Government with the NPF. Allied to this is greater scrutiny and accountability over how the decisions they take will contribute towards the National Outcomes.

More specifically we recommend that the Scottish Government and COSLA consider how, as recommended by the SLF:

money can be allocated based on an understanding of the activities, outputs and intended impact of the programmes it will fund, including their contribution to the NPF;

funding can be used to incentivise collaborative working to overcome some of the barriers caused by delays in when and who benefits financially later on from any longer savings;

commissioning procurement and grant giving is focussed on, and aligned with, improving outcomes linked to the NPF.

Other sources of funding

Since creation of the NPF in 2007, Scotland’s fiscal arrangements have changed considerably, with the further devolution of taxation and welfare powers, shared funding arrangements (City and Region Deals), and replacement EU funds (UK Shared Prosperity Fund, Community Renewal Fund and Levelling Up Fund) passed directly to local authorities. While public sector bodies, including local authorities, are required under the 2015 Act to have regard to the National Outcomes in carrying out their functions, the Act does not apply to governance structures for City and Region Deals or replacement EU funds.

During evidence to the Committee on 24 February 2022, the then UK Government's Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities was asked whether Scottish Government priorities, such as the NPF, are considered in decisions on targeting replacement EU funds. He said that “we will take the Scottish Government’s priorities into account, because we want to reach agreement wherever possible”. He added that, where UK and Scottish Government priorities differ, resolution to the satisfaction of both governments, “ideally would be done through open, regular dialogue and honesty on our part about where we might diverge”.1

The DFM explained that the Scottish Government has made clear to the UK Government its frustration and dissatisfaction with the arrangements for the UKSPF which –

Does not provide a satisfactory opportunity for us to ensure that the expenditure- which, before the new arrangements, would have been aligned with the direction of policy travel in Scotland – will be so aligned in future.2

The DFM acknowledged that "have regard to" in the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act could be replaced with "must be aligned with" in future which might place a higher level of obligation on public authorities to ensure such expenditure might be made to align in future.2

Since the NPF was introduced in 2007 public sector spending and tax raising in Scotland has become much more complex. There is also now a potential for a significant level of UK Government funding to be spent in Scotland which does not necessarily reflect the priorities in the NPF. Given this, we consider that the UK Government should take account of the National Outcomes when considering its spending in devolved areas.

We also recommend the Scottish Government and COSLA review the organisations subject to the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 "have regard to" duty to ensure it captures the range of bodies that receive public funding and which are now operating in Scotland.

The review of the NPF

The Scottish Government will shortly begin seeking views as part of the forthcoming review of the National Outcomes. As the DFM explained that review will be informed by public engagement undertaken through a range of approaches which may include community gatherings and surveys.

In February 2022 the Committee wrote to the DFM seeking an extension to the statutory 40 day consultation period the Scottish Parliament has to consider the results of the NPF review, including any proposals for revisions to the National Outcomes. This was in light of concerns from previous Parliamentary Committees regarding the impact of this short timescale on their scrutiny during the review of the NPF in 2018. Responding, the DFM committed to explore this further and asked his officials to liaise with the Committee on how much additional time may be required, and how this fits with the programme for the review overall.

Oxfam Scotland advocated for far greater depth and quality to the public consultation for the next review in order to give it legitimacy and to ensure that—

The national outcomes were right in the first place or then to involve the public in reporting - ensuring that lived experience goes side by side with hard data - and scrutiny.

As we heard there is also more that can be done to encourage greater engagement from Business, the public and media. Carnegie UK and COSLA both highlighted the role of the media in influencing the culture and public perception of public services. They both suggested that proactive work with the media was needed if there was to be a change of focus from inputs and outputs, and towards being held to account for outcomes and system-change through the NPF. The Commissioner's office in Wales was highlighted as having a prominent media role including encouraging thinking about social progress in the round through its public engagement and outreach activities.1

The language of the NPF was also raised with us - with the confusion between "NPF" as the acronym for the National Performance Framework but also for the National Planning Framework one such example. At our Dundee event some participants recognised that the NPF is a "well being strategy" while noting that this was intangible, opaque and is not relatable to the public.2

There was some support for the NPF to be renamed as a "National Wellbeing Framework" which Dr French explained might excite people more and move away from the performance element which is usually something an organisation uses to regulate its processes.3 He considered that the use of Wellbeing in the Welsh Act had led to its greater traction in Wales than if words with a performance focus had been used.3

Carnegie UK agreed that Wellbeing was a concept that people can convene around. They considered that the current language is a significant barrier to wider societal use of the framework as people outwith the Scottish Government do not see themselves as having a role to play in a "performance" framework.3

In June 2008, the Scottish Government launched a website designed to present information on how Scotland is performing against the range of indicators outlined in the National Performance Framework. Public Health Scotland highlighted how the COVID real time data can really engage the public and some of the recent learning from that could be built upon for the NPF.1

The potential for the NPF website to capture public interest in the NPF and communicate its values was raised by Dr French. He contrasted its historically low engagement rates from the public and media in Scotland with the scaffolding of guidance, outcomes indicators, and stories provided by the Commissioner in Wales.3